The Fusion Funding Explosion: Why Now?

Fusion energy has finally stopped being science fiction. If you've been paying attention to the energy sector lately, you've probably noticed the funding announcements coming faster than the reactions themselves. Inertia Enterprises just pulled in $450 million, and that's just one headline in a wave of fusion startups attracting serious capital from top-tier investors.

What's changed? For decades, fusion was the perpetual "30 years away" technology that never quite arrived. But in December 2022, something shifted. The National Ignition Facility achieved something that seemed impossible: a fusion reaction that released more energy than it consumed to start. This wasn't theoretical anymore. It was real. Reproducible. And it proved that fusion breakeven wasn't a pipe dream.

That breakthrough cracked open investor wallets. Suddenly, fusion wasn't speculative research. It was a proven physics problem with engineering challenges investors could wrap their heads around. The result? Fusion startups have pulled in over $10 billion in venture funding in recent years. We're talking serious money from the big names: Bessemer Venture Partners, Google's investment arm GV, Breakthrough Energy Ventures (backed by Bill Gates), and even Nvidia.

Inertia Enterprises is betting big that they can turn this proven physics into commercial reality. But there's a catch. Every fusion startup is approaching the problem differently. Some use magnetic confinement. Others use inertial confinement. Some are experimenting with completely novel approaches. The race is on to figure out which technology actually works at scale.

Here's what makes Inertia different, why this funding matters, and what it tells us about the future of energy.

Who Is Inertia Enterprises and Why Should You Care?

Inertia Enterprises is betting on a specific flavor of fusion technology, and its founding team has some serious credibility. Jeff Lawson co-founded Twilio, the cloud communications platform that IPO'd and now has a multi-billion dollar market cap. Twilio does customer engagement infrastructure, helping companies send SMS, make calls, and build communication into their apps. Lawson was CEO for years and basically grew the company from nothing.

Now he's pivoting to fusion. That might sound random, but think about it: Lawson has track record building companies that solve hard technical problems, scale infrastructure, and operate in competitive markets. That's exactly the skillset you need for fusion.

Then there's Annie Kircher, who led the actual experiments at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory's National Ignition Facility that achieved fusion breakeven. We're not talking about a manager or a theorist here. Kircher actually conducted the experiments that proved inertial confinement fusion could work. She's still at Lawrence Livermore, which is unusual. Most startups would pull their technical lead full-time. Instead, Inertia kept Kircher in her position at the lab, which suggests they're maintaining deep ties with Livermore and probably getting access to research infrastructure most startups could only dream about.

The third co-founder is Mike Dunne, a Stanford professor who helped Lawrence Livermore develop the actual power plant design based on NIF technology. So you've got an entrepreneur, a world-class researcher, and an engineer with a design already on paper. That's a strong foundation.

The $450 million Series A was led by Bessemer Venture Partners, which has backed companies like Shopify, Twitch, and Figma. GV (Google's venture arm) participated, along with Modern Capital, Threshold Ventures, and others. These aren't random venture firms throwing darts. This is coordinated belief from major institutional investors that this company can actually execute.

But what are they actually trying to build?

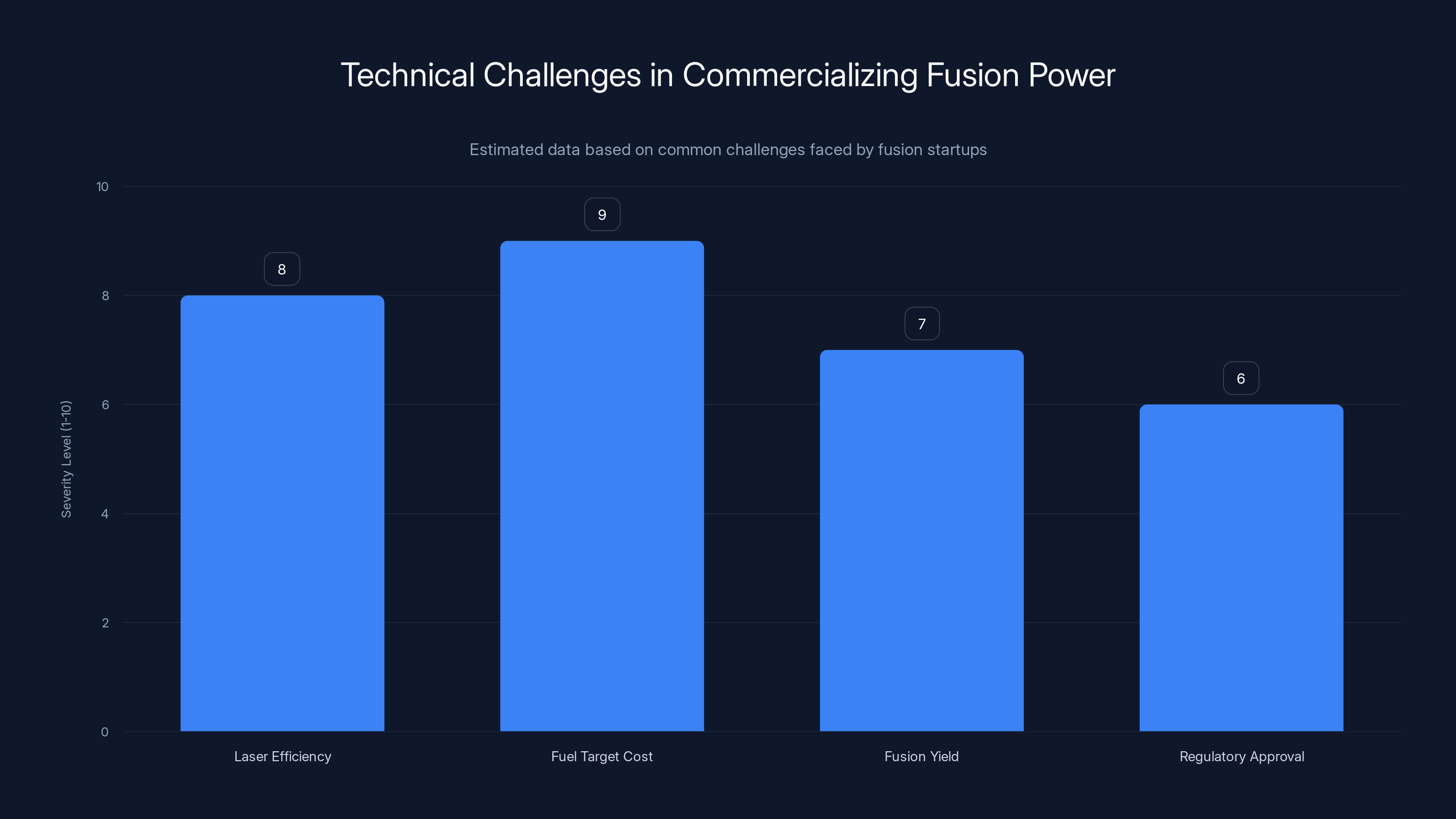

Estimated data shows that reducing fuel target cost and improving laser efficiency are the most severe challenges for fusion commercialization.

The Technology: How Inertia's Laser-Powered Fusion Works

Let's back up and explain inertial confinement fusion, because it's the core of everything Inertia is doing.

Fusion happens when you slam atoms together so hard that they merge, releasing energy in the process. The hard part is the "slamming together" bit. Atoms naturally repel each other (because of electrostatic forces), so you need insane temperatures and pressures to force them to fuse.

There are two main approaches. Magnetic confinement uses massive magnetic fields to trap hot plasma and hold it in place long enough for fusion to happen. That's what ITER (the international fusion project) is building. It's like a torus-shaped bottle that uses magnetic fields as the walls. The problem: it's absurdly complex and expensive.

Inertial confinement is different. Instead of holding plasma steady, you compress it extremely rapidly using lasers or other energy sources. The idea is that the fuel pellet's own inertia keeps it compressed long enough for fusion to occur. Think of it like a controlled nuclear implosion.

Inertia's specific approach works like this: lasers bombard a fuel target (a tiny pellet of deuterium and tritium), which are isotopes of hydrogen. The laser light hits the target and gets converted into X-rays inside a special chamber. Those X-rays then heat and compress the fuel pellet from all directions. The compression is so extreme that the atoms inside fuse, releasing energy.

This is based directly on how the National Ignition Facility works. NIF uses 192 massive lasers all firing at the same tiny target simultaneously. The geometry and timing have to be perfect, or the whole thing fails. But when it works, you get fusion breakeven: more energy out than energy in.

Here's where Inertia thinks they can disrupt the economics: NIF's system is incredibly sophisticated. Each target takes dozens of hours to craft by hand. The lasers are enormous, expensive, and only fire occasionally. It's built for science, not commerce.

Inertia is asking: what if we use the same basic principles but optimize for mass production? They're designing lasers that can fire 10 times per second (compared to NIF's once-per-shot approach). They want to use targets that cost less than $1 each and can be mass-produced. And they're building a power plant design that would use 1,000 of these lasers bombarding 4.5mm targets continuously.

The math is interesting. NIF gets fusion breakeven with 192 lasers hitting one target. Inertia wants 1,000 lasers hitting targets 4.5mm in diameter. That's a different engineering problem entirely. You're scaling up, but also scaling down the laser energy per system. It's a bet that redundancy and frequency matter more than single-shot perfection.

Lawson and his team think this is the path to commercial fusion. Build it for manufacturing, not for research. That's a fundamentally different engineering mindset.

The NIF Breakthrough: What Actually Happened and Why It Matters

To understand why Inertia's timing is perfect, you need to understand what NIF actually achieved. For decades, fusion breakeven was theoretical. Every fusion project claimed they were close. Every year brought new promises. Every decade brought disappointment.

Then in December 2022, NIF fired its lasers at a fuel target and got a reaction that released 3.15 megajoules of energy. That might not sound like much, but here's the key: they put in 2.05 megajoules to start the reaction. For the first time ever, a fusion reaction released more energy than the input.

This was called "scientific breakeven" or "ignition." It proved the physics worked. Fusion energy gain was real and reproducible.

Now, this wasn't electricity you could use. The reaction itself released more energy than was input, but the lasers that created the input were only about 10% efficient. So the overall system was still a massive net loss. You put in 20 megajoules into the laser system to get 3.15 megajoules out. That's terrible economics.

But that's not the point. The point is the physics works. The problem is now engineering and economics, not "can we actually achieve fusion fusion."

For startups like Inertia, this changes everything. Now you're not trying to prove fusion is possible. You're competing on who can make it cost-effective at scale. That's a business problem, not a physics problem. And that's why investors suddenly got interested.

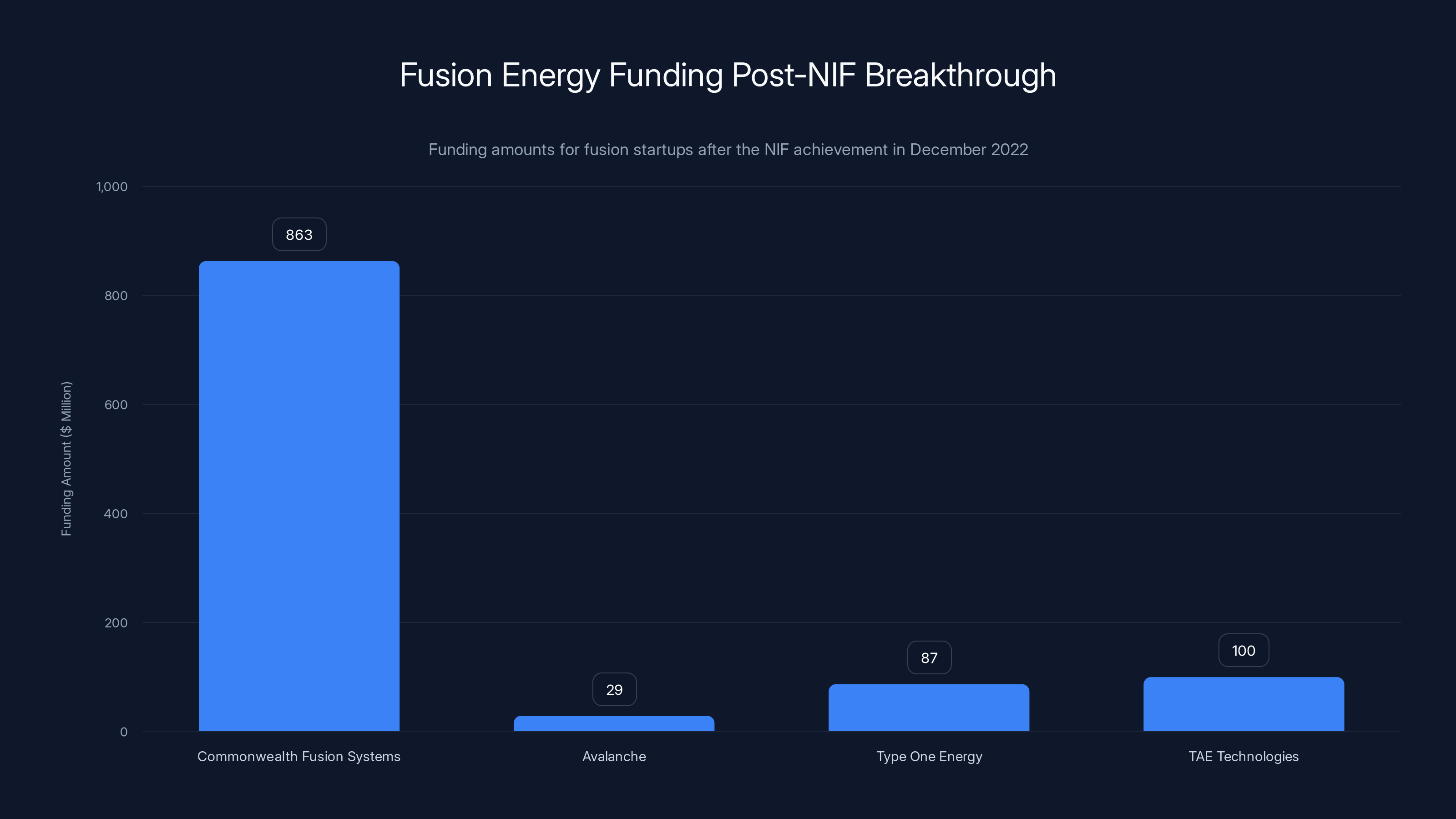

Since that NIF breakthrough, fusion funding has exploded. Commonwealth Fusion Systems (which also uses inertial confinement but with a different approach) raised

The entire landscape shifted from "will this ever work" to "which approach will work first."

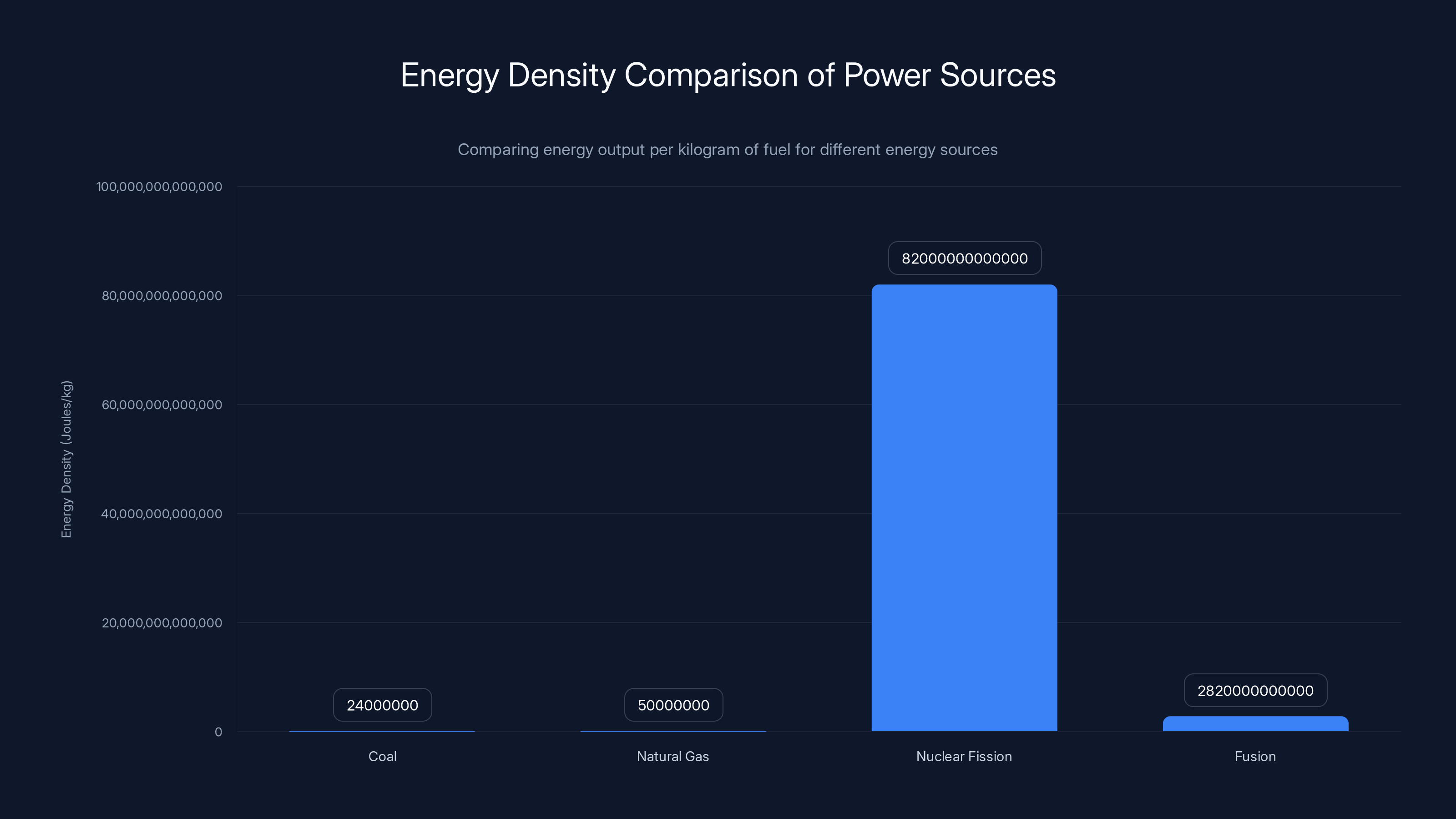

Fusion power offers a significantly higher energy density compared to coal and is comparable to nuclear fission, making it a promising energy source. Estimated data based on typical values.

The Series A Details: Who Invested and Why

Let's look at the funding round itself. Inertia raised

Bessemer Venture Partners led the round. They've built a strong track record in infrastructure and deep tech. They backed Figma (design tools), Twitch (streaming), Shopify (e-commerce), and dozens of others. Bessemer understands scaling engineering organizations and deep technical problems. They're not afraid of long development cycles.

GV (Google Ventures, which is now just called GV) participated. This is Google's venture arm, and they've been actively investing in energy-related startups. Google has made public commitments to sustainable energy, so fusion aligns with their strategy. More importantly, Google has deep relationships with national labs and research institutions. Having GV in the round probably means Inertia gets some institutional legitimacy and connection to resources.

Modern Capital and Threshold Ventures also participated. These are both solid venture firms with experience in technical deep-tech. The investor composition suggests this round was orchestrated by serious, credible firms who've done their diligence.

Here's what the round tells us: these investors believe in the technology, believe in the team, and believe they can scale to commercial deployment. They're betting that Inertia can solve the engineering problems faster than competitors. That's a big vote of confidence.

The Power Plant Timeline: Building for 2030

Inertia has stated they plan to start construction on a grid-scale power plant in 2030. That's four years away (from 2026, when this funding was announced). For a fusion company, that's an incredibly aggressive timeline.

Let's break down what that probably means. First, "start construction" doesn't mean "producing electricity." It means breaking ground, laying foundation, beginning assembly. You're probably looking at another 5–7 years after construction begins before you get electricity to the grid. So we're probably talking 2035–2037 for actual power generation. That's still faster than any other fusion company has publicly committed to.

Why the aggressive timeline? There are a few factors. First, Inertia is building on existing proven designs from NIF. They're not trying to invent new physics. Second, they have access to Lawrence Livermore's infrastructure and expertise through their co-founders. Third, they're betting on scaling existing technology, not developing entirely new approaches. And fourth, the capital they just raised ($450 million) can fund several years of engineering and prototyping at a serious pace.

That said, fusion is littered with missed timelines. Companies promised 2020 deployment dates that slipped to 2025. Those slipped to 2030. It's a pattern. Energy technology is hard, regulatory approval is slow, and engineering surprises are common.

But the fact that Inertia is publicly committing to 2030 construction suggests confidence. It also suggests they're pursuing a path that minimizes technical unknowns. They're using proven technology from NIF, not attempting breakthrough physics. That reduces risk.

The Competitive Landscape: Who Else Is Racing to Fusion?

Inertia isn't alone in this race. There are dozens of fusion startups, each betting on different technologies and approaches.

Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS) is probably the most well-known. They're developing a fusion reactor using high-temperature superconducting magnets for magnetic confinement fusion. They've raised over $863 million from Google, Nvidia, Breakthrough Energy Ventures, and others. They've also announced aggressive deployment timelines. Their approach is completely different from Inertia's (magnetic confinement vs. inertial confinement), so they're not direct competitors, but they're racing to the same finish line.

Avalanche recently announced $29 million in funding for a desktop-sized fusion reactor. Their approach is different again: they're using a stellarator design with superconducting magnets. The advantage of their approach is they're claiming smaller, more deployable reactors. The disadvantage is they're earlier stage technologically.

Type One Energy has raised

TAE Technologies announced a reverse merger with Trump Media that values the combined company at $6 billion. TAE uses aneutronic fusion (colliding boron nuclei instead of hydrogen isotopes), which eliminates neutron radiation but is harder to achieve. The Trump Media deal was... let's say unusual. It suggests TAE was having trouble raising traditional venture funding.

General Fusion announced a merger with Spring Valley Acquisition Corp III that values them at $1 billion. General Fusion had historically struggled to raise private venture funding, which suggests their approach might be less attractive to venture investors.

Each company is betting on different technologies, different timelines, and different deployment models. The industry hasn't converged on a single winning approach yet. That's good news and bad news. Bad news: someone's going to be wrong, and investors will lose money. Good news: there's still room for innovation and multiple approaches to work.

Inertia's bet is that inertial confinement, optimized for mass production, wins. That's a defensible position given NIF's recent success and the existence of proven designs.

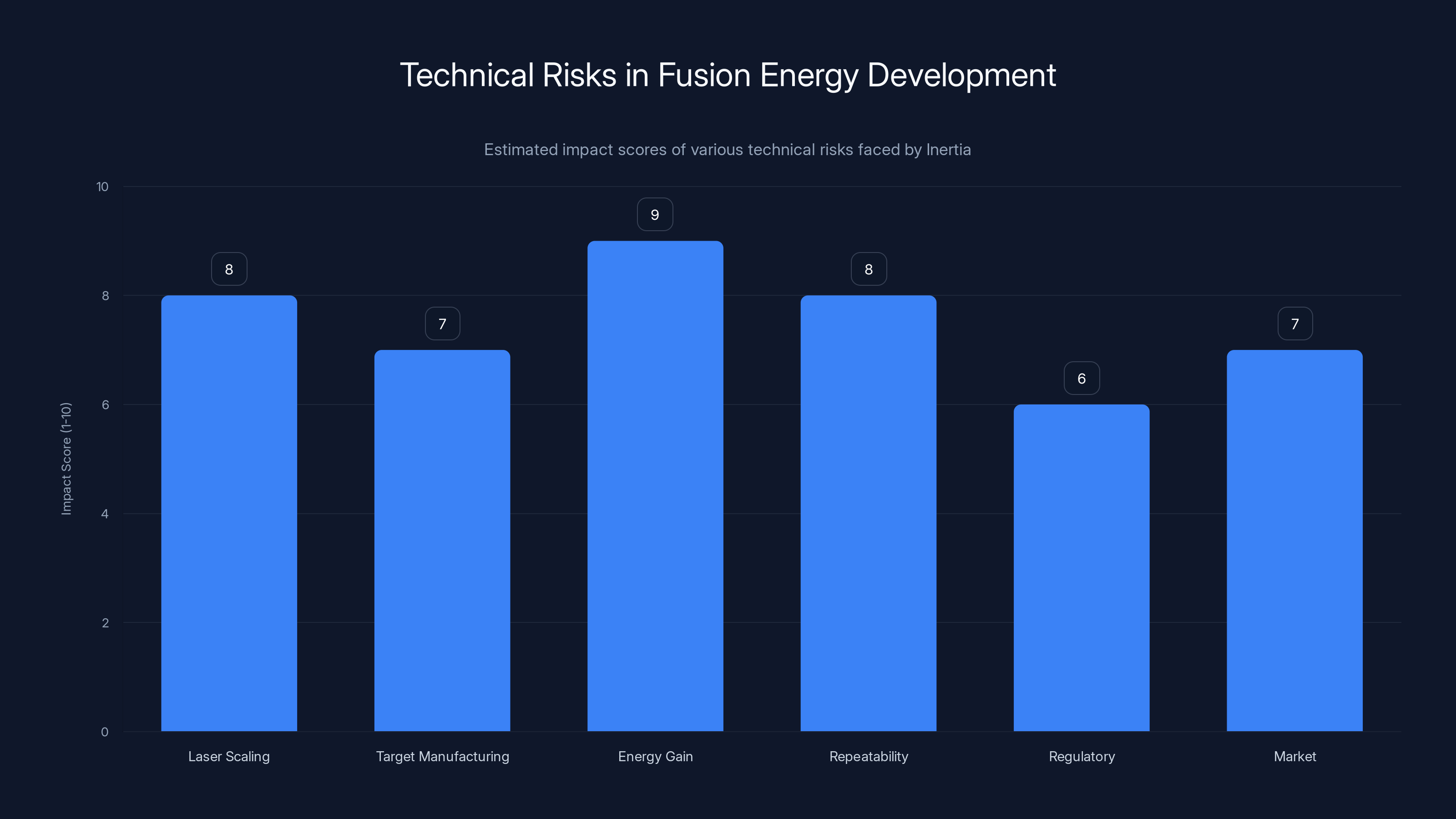

Estimated data: The energy gain and repeatability problems are considered the highest risks, with scores of 9 and 8 respectively, due to their fundamental challenges in physics and engineering.

The Economics: Why Fusion Power Makes Financial Sense

Fusion is interesting because it solves a fundamental problem: energy cost and supply.

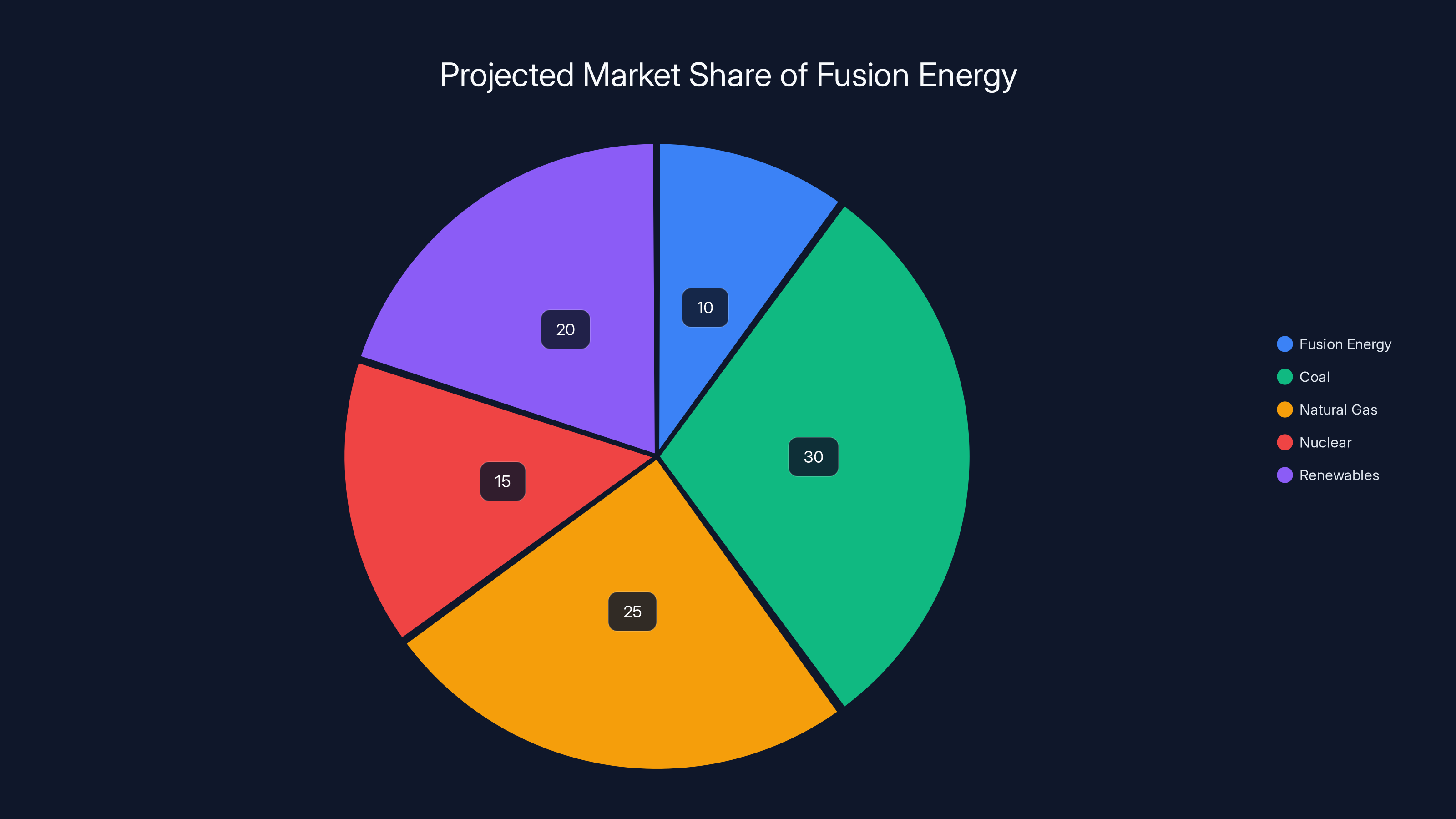

Today, electricity grids rely on a mix of sources: natural gas (cheap but pollutes), coal (cheap but pollutes), nuclear fission (reliable but expensive), renewables (clean but variable). The energy mix differs by region, but the fundamental trade-off is the same: you're trading cost, reliability, and environmental impact against each other.

Fusion could theoretically break this trade-off. It produces massive amounts of energy (the reaction itself is incredibly energetic) with no carbon emissions, minimal waste (compared to fission), and using fuel that's abundant (hydrogen isotopes are everywhere). The problem has always been cost: making fusion commercially viable.

Here's the physics. Deuterium-tritium fusion releases 17.6 megaelectronvolts of energy per reaction. That's approximately 2.82 trillion joules per kilogram of fuel. For comparison, burning coal releases 24 megajoules per kilogram. Uranium fission releases 82 trillion joules per kilogram. So fusion is about 35 times more energy-dense than coal and comparable to fission.

But here's where it gets interesting: the fuel is cheap. Deuterium occurs naturally in seawater (1 part per 5,000). Tritium can be bred from lithium. Lithium is abundant and relatively cheap. You're not buying rare, expensive fuel. You're using something almost free.

The problem is the reactor itself. Building a reactor that can contain and fuel fusion reactions is absurdly expensive. ITER, the international fusion project, has cost over $22 billion and still isn't producing electricity. That's prohibitive for commercial power generation.

Inertia's bet is that by using lasers (which are getting cheaper) and mass-producing components, they can bring the cost down. If they can build a power plant for $5 billion and it runs for 40 years producing gigawatts of power, that's economically viable. The math works if you can solve the engineering.

Why does venture capital care? Because if Inertia can prove the model works, the addressable market is literally the global power grid. Every coal plant, every natural gas plant, every aging nuclear facility could theoretically be replaced with a fusion plant. That's a multi-trillion dollar market.

That's why investors are writing $450 million checks.

The National Ignition Facility Connection: Standing on Giants' Shoulders

One thing that makes Inertia's position special is their connection to the National Ignition Facility. Annie Kircher is still an NIF scientist, and the company's designs are based on NIF technology. This isn't coincidence. This is strategic positioning.

NIF is a Department of Energy facility. It's publicly funded, and the research is published. Inertia is taking decades of government research, NIF's recent breakthrough, and the institutional knowledge of people who actually conducted the experiments. They're not inventing fusion from scratch. They're commercializing proven science.

This has advantages and disadvantages. Advantage: you know the physics works. You're not betting on unproven theory. Disadvantage: the initial designs from NIF are built for science, not economy. Translating that into a commercial product requires substantial engineering effort.

But here's the bigger picture: by maintaining connections to NIF, Inertia probably gets access to research infrastructure, talent, and validation that other startups don't have. When they build something, NIF can probably test it. When they have questions, they have direct access to the world's foremost inertial confinement fusion experts. That's a massive advantage in a competitive landscape.

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (which runs NIF) also has a direct interest in seeing fusion commercialized. The government has been funding fusion research for 60 years. If a company spins out of government labs and actually succeeds, that's a win for the lab's prestige and budget justification. So there's probably alignment between NIF, Lawrence Livermore, and Inertia's success.

For venture investors, this is actually a risk reducer. If the government research institutions are basically cheering for you, that's de facto validation. You're not a random startup claiming to solve fusion. You're a startup commercializing government-proven technology.

The Laser Technology: The Real Engineering Challenge

Here's where the engineering gets real. Inertia says they're building "one of the world's most powerful lasers" with this funding. What does that mean?

NIF's lasers are already incredibly powerful. The National Ignition Facility's laser system stores energy in massive glass amplifiers, then releases it in a single, coordinated pulse. The entire system is the size of a building. The pulse lasts nanoseconds. The energy delivered is enormous.

Inertia's challenge is different. They don't need one massive laser that fires once. They need many smaller lasers that can fire repeatedly (10 times per second, they've claimed). That's a completely different engineering problem.

Think about it this way: NIF optimizes for energy per shot. Inertia optimizes for repetition rate and cost per shot. That requires advances in laser technology, thermal management (you're generating a lot of heat with 10 Hz operation), target manufacturing, and the entire supply chain.

Lasers have been improving steadily for decades. Solid-state lasers, fiber lasers, diode-pumped lasers, all these technologies have gotten cheaper and more efficient. But the challenge of a 10 Hz, high-energy industrial laser system is still substantial. This is probably where a lot of the $450 million will be spent.

The good news: lasers are a solved problem in many other applications. Laser cutting, laser welding, laser marking. These are all industrial applications. There's manufacturing infrastructure and expertise. Inertia probably isn't inventing new laser physics. They're adapting and scaling existing laser technology to their specific needs.

But here's the catch: even with all this funding, building a laser system that can deliver 10 kilojoules 10 times per second reliably is not trivial. Lasers generate heat. Heat management is hard. Efficiency drops with heat. You're fighting thermodynamics. The team will need to solve some genuinely hard engineering problems.

That's probably why they hired a team of experienced engineers and why this funding round is so large.

Estimated data: Fusion energy could capture a 10% market share, significantly impacting the global energy landscape.

The Target Manufacturing Problem: Going from Handcraft to Mass Production

One of Inertia's boldest claims is that they can mass-produce fuel targets for less than $1 each. At NIF, each target takes dozens of hours to craft and costs thousands of dollars. That's fine for a research facility. It's a complete non-starter for commercial power generation.

Inertia's targets are 4.5mm pellets containing deuterium and tritium fuel. Creating a perfect sphere of fuel, with perfect symmetry, with exact density, is not trivial. You need precision manufacturing. But if you can do it at scale, with automation and volume manufacturing techniques, the cost goes down dramatically.

The parallel here is semiconductor manufacturing. In the 1970s, making a semiconductor chip was a handcrafted process. Now it's automated, mass-produced, and incredibly cheap per unit. Inertia is betting they can do the same for fusion fuel targets.

But here's the challenge: semiconductor manufacturing benefits from Moore's Law and massive volume (billions of chips produced annually). Fusion targets have much smaller potential volume. Even if Inertia builds a 1,000-laser power plant, that's still only millions of targets per year, not billions. That's much smaller scale.

Doing precision manufacturing at smaller scale is harder than at massive scale. You need to find manufacturing processes that work for your volume. You need suppliers. You need quality control. This is an unglamorous part of the business, but it's critical.

I'd bet a significant portion of Inertia's $450 million goes to solving this problem. They're probably setting up manufacturing partnerships, developing automation processes, and proving they can hit cost targets. This is where venture capital meets manufacturing reality.

The Grid Connection Problem: Getting Power to People

Okay, so Inertia builds a working fusion reactor. It produces 3 gigawatts of power. Now what? How do you actually deliver that electricity to the grid?

This is a problem that most fusion startups gloss over, and it's a real challenge. Power plants don't exist in isolation. They're connected to grids with specific technical requirements: voltage, frequency, stability, ramp-up and ramp-down curves. Fusion reactors are novel, and grid operators have legitimate questions about how they interact with existing infrastructure.

There's also the regulatory problem. No fusion power plant has ever been built commercially. So what permits do you need? What environmental approvals? What safety standards apply? This is uncharted territory for regulators.

Inertia's 2030 construction timeline probably assumes they've already worked through these questions. If Lawrence Livermore and the Department of Energy are coordinating with grid operators and regulators, that accelerates the timeline. But if Inertia is working from scratch, it could add years.

This is actually one area where Inertia's connection to government labs is a huge advantage. Lawrence Livermore can probably facilitate conversations with regulators and grid operators that a private startup couldn't easily access.

The Venture Capital Trend: Why Fusion Became Hot

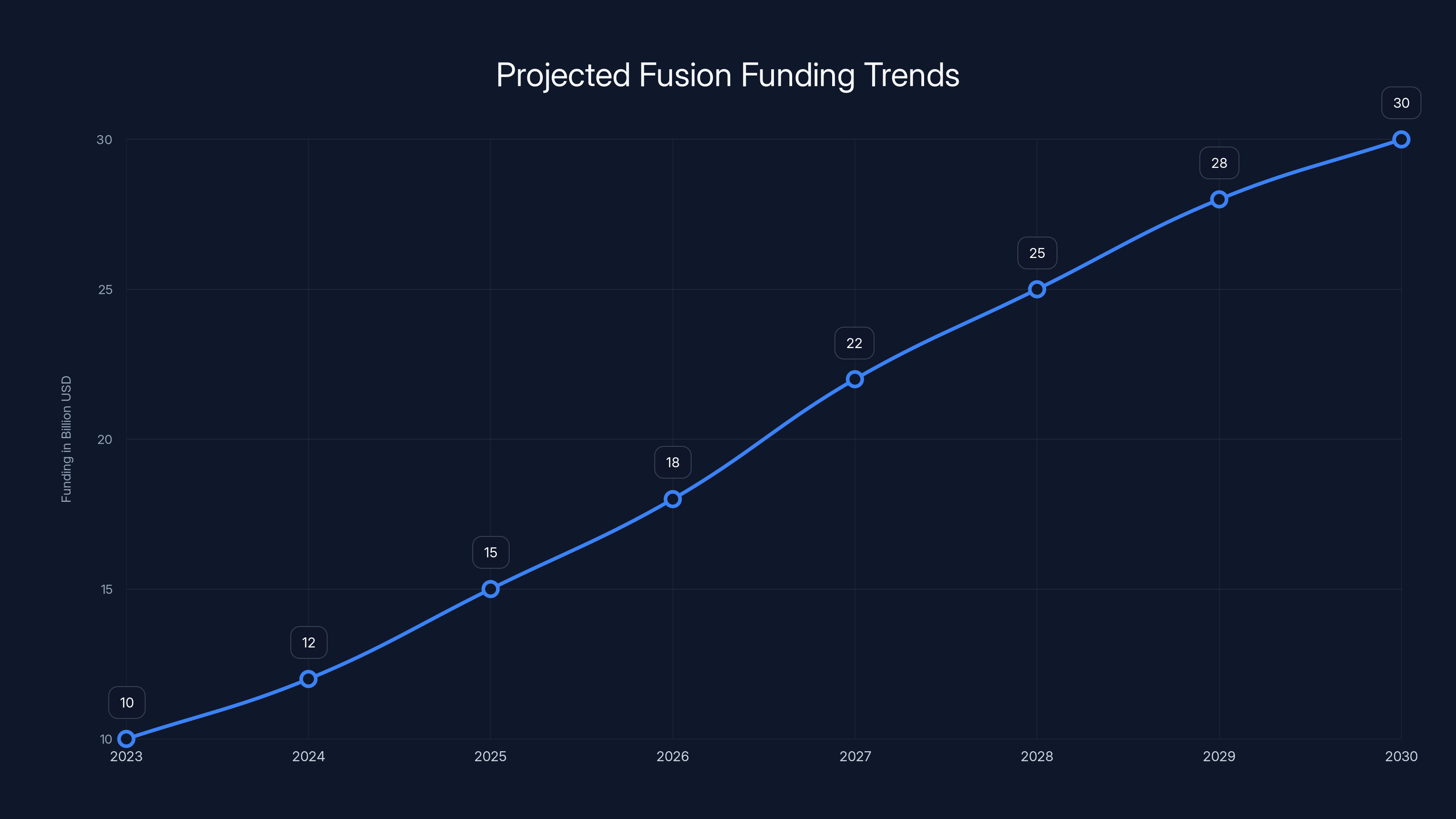

Fusion funding has exploded in recent years. There are a few reasons for this.

First, there's climate change. Energy is a critical bottleneck in decarbonization. You can't electrify transportation, heating, and industry without clean power. Solar and wind are important, but they're variable. Battery storage is improving, but it's still limited. Nuclear fission is reliable but politically difficult to expand. Fusion could theoretically solve this, and that mission-driven narrative appeals to many investors.

Second, there's the NIF breakthrough. That was permission to believe. Suddenly, fusion wasn't theoretical. It was real. That changed how investors evaluated fusion startups. Instead of "will this ever work," it became "who will commercialize this fastest."

Third, there's the technology trend. Lasers are getting better. Materials science is improving. Computing power has increased, making simulation and optimization easier. The underlying technologies that make fusion possible are all improving. That creates a moment where previously impossible engineering becomes possible.

Fourth, there's the geopolitical angle. Climate change is a global problem, but it's also a technological race. Countries want to lead on clean energy. That drives government funding into fusion. When governments care about something, venture capital notices.

Fifth, and most cynically, fusion has become fashionable. If a startup can claim they're building fusion, they attract investor interest. It's a sexy problem. Some of this funding is probably irrational exuberance. Some companies will fail. That's fine. That's how venture capital works.

But overall, the capital flowing into fusion reflects genuine belief that this is a solvable problem and a massive market opportunity.

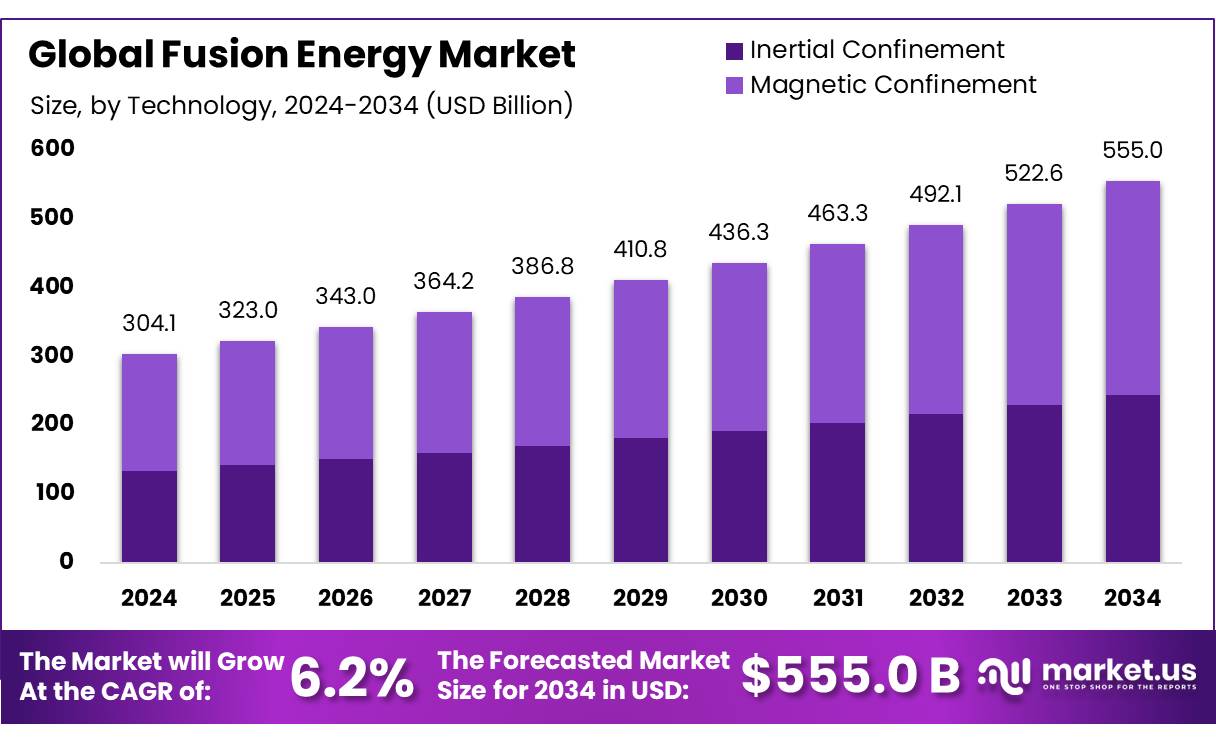

Fusion funding is projected to grow significantly by 2030, driven by climate change needs and tech investments. Estimated data.

The Technical Risks: What Could Go Wrong

Inertia has a proven approach (based on NIF), experienced founders, and massive capital. But there are still substantial technical risks.

First, the laser scaling problem. They need to build a 10 Hz, high-energy laser system. That requires advances in laser technology, thermal management, and reliability. Lasers can fail. Thermal stress can cause degradation. Operating at 10 Hz for extended periods is very different from NIF's single-shot model. They might hit roadblocks.

Second, the target manufacturing problem. Mass-producing fuel pellets to NIF precision at $1 per unit is a huge engineering challenge. They might find that quality and cost are harder to achieve simultaneously than expected.

Third, the gain problem. NIF achieves ignition, but the overall system is still a net energy loser when you account for laser inefficiency. Inertia needs to improve laser efficiency substantially to achieve useful power output. This is fundamental physics, not just engineering. Efficiency improvements might hit natural limits.

Fourth, the repeatability problem. NIF occasionally achieves high fusion yields. Inertia needs to achieve high yields reliably, 10 times per second, indefinitely. That's a big leap. One stray particle in the target, one misaligned laser, one thermal fluctuation could ruin the shot.

Fifth, the regulatory problem. No one has built a commercial fusion reactor. Regulators might slow deployment with unforeseen requirements. Neighbors might object to a fusion plant nearby. Public perception of fusion is positive now, but a setback could change that quickly.

Sixth, the market problem. The timeline assumes steady electricity demand and favorable power purchase agreements. What if there's a recession? What if renewable energy costs drop faster than expected? What if grid dynamics shift in ways that don't favor large baseload plants?

These are all solvable problems, but they're real. Inertia is betting they can solve them faster than competitors. That's a confidence statement, not a guarantee.

The Timeline Ahead: 2026-2030 and Beyond

If Inertia executes on plan, here's what the next few years probably look like.

2026-2027: Engineering and prototyping. Build lasers, test them, iterate on design. Probably several iterations and failures along the way. Develop target manufacturing processes. File patents. Hire talent.

2027-2028: Scale up testing. Prove the 10 Hz laser system works at scale. Demonstrate consistent fusion yields. Maybe get NIF or another national lab to validate results. Show that the approach is reproducible.

2028-2029: Design the power plant. Work with regulators and grid operators. Figure out interconnection points, safety standards, permitting. Finalize the power plant design.

2029-2030: Start construction. Break ground, build facility, install equipment. This is the public milestone they've announced.

2030-2035: Commission the power plant. Get it operating, debug problems, optimize performance. First electricity to the grid, hopefully by 2035 or so.

2035+: If successful, scale to multiple plants. Replicate the design. Build a supply chain. Become a power company.

This assumes everything works roughly on schedule. In reality, there will be delays. Some technical problems will take longer to solve than expected. But if Inertia stays on something like this trajectory, they could have commercial fusion power within 10 years. That would be revolutionary.

The Broader Implications: Why Fusion Matters for Energy

If Inertia succeeds, it's not just good for them. It's transformational for energy.

Power generation today is dominated by large central plants: coal, natural gas, nuclear. These plants are built once and operate for 40-60 years. They're optimized for capital efficiency and operating reliability. Renewables have disrupted this model, but they require storage and grid balancing.

Fusion could offer something different: reliable, abundant, clean power from a plant that's comparable in size to existing plants but produces no carbon and minimal waste. That's genuinely game-changing.

If the first plant works, Inertia probably licenses the design to other operators. Maybe utilities want to replace aging coal plants with fusion. Maybe governments want to add capacity. Maybe developing nations want fusion as a path to electrification without building coal infrastructure.

The global electricity generation market is worth trillions. Even a 10% market share would be enormous. That's why venture capital is interested. That's why government labs are interested. That's why this matters.

Of course, that's the optimistic scenario. There are other scenarios: Inertia hits technological limits and doesn't achieve net useful energy output. Or they do, but the cost is too high to compete with renewables. Or they succeed technically but hit regulatory or public acceptance issues. Those are all real possibilities.

But from a risk-reward perspective, the potential upside justifies the investment. If fusion works, it solves humanity's energy problem. That's not hyperbole. It's genuine.

Following the NIF breakthrough, significant funding was secured by fusion startups, indicating a shift in focus from proving fusion viability to achieving cost-effective solutions. (Estimated data for TAE Technologies)

The Role of Government Labs: Public-Private Fusion

One thing that makes Inertia different from typical venture startups is their deep connection to government research infrastructure. Annie Kircher is at Lawrence Livermore. The designs are based on NIF research. The co-founders have academic affiliations.

This is a fascinating model: government labs do fundamental research, prove it works, then private companies commercialize it. The public pays for the hard science. Private capital pays for the engineering and scaling. The results belong to everyone.

This model has worked for other technologies: the internet (ARPA/DARPA funded), GPS (military funded), touchscreens (publicly funded research), pharmaceuticals (NIH funded basic research, pharma companies do clinical trials).

For fusion, this model makes sense. Decades of government research proved fusion was possible. NIF's breakthrough was the inflection point. Now private companies are racing to commercialize. Government labs get the satisfaction of seeing their research used. Private companies get access to proven science. The public gets cheaper energy eventually.

But there are tensions in this model. IP ownership gets complicated. How much research belongs to the government vs. the company? What if Inertia goes public or gets acquired? What happens to access to government lab resources?

Inertia has probably negotiated some kind of agreement with Lawrence Livermore and the DOE that gives them access in exchange for some level of IP sharing or licensing. Those details aren't public, but they probably exist.

This public-private partnership is actually a model other fusion companies should consider. Getting direct access to national lab expertise and facilities is a huge advantage. It's worth negotiating for.

The Competitive Pressure: Who Needs to Worry

Inertia's $450 million raise and aggressive timeline put pressure on other fusion companies. If they achieve what they're claiming, they move the goalposts.

Commonwealth Fusion Systems has more funding overall, but they're on a different technological path (magnetic confinement vs. inertial confinement). If Inertia reaches grid power first, even if CFS's design is ultimately superior, Inertia gets the first-mover advantages: experience, supply chain, regulatory knowledge, and market relationships.

Smaller fusion startups probably feel the pressure most acutely. If Inertia demonstrates a working power plant design, every other startup needs to explain why their approach is better or faster. Investors will ask hard questions. Some companies might struggle to raise follow-on funding.

But there's also room for multiple winners. If multiple approaches work, the industry can specialize. One company might focus on baseload power, another on distributed generation, another on extreme high-temperature applications. Different approaches for different problems.

The real loser would be if fusion in general fails to achieve commercial viability. That would make all the venture funding look foolish. But if any significant approach works, multiple players will probably succeed.

Lessons for Deep Tech Founders: What Inertia Gets Right

Inertia's approach offers lessons for other deep tech founders trying to raise massive capital for technically ambitious projects.

First, credibility matters. Inertia's co-founders aren't randomers with a fusion dream. Lawson built Twilio. Kircher ran NIF experiments. Dunne is a Stanford professor. That matters to investors. If you're asking for hundreds of millions for deep tech, you need a track record or deep expertise.

Second, standing on shoulders helps. Inertia isn't inventing fusion from scratch. They're commercializing proven government research. That de-risks the technical bet. Investors care less about "will this work" and more about "can you execute."

Third, aligned incentives matter. Inertia probably has relationships with Lawrence Livermore and DOE that are aligned with commercial success. Government labs want to see their research used. That creates partnership and support beyond just the venture capital.

Fourth, clear timeline and milestones matter. Inertia said they'll start construction in 2030. That's specific. It's testable. It's aggressive but plausible. Investors want to believe in a path to success. A vague "someday we'll solve this" doesn't work. A "2030 construction start" does.

Fifth, massive capital can move the needle. $450 million is real money. It can fund a large engineering team, expensive prototyping, supply chain development. Deep tech requires patient capital and capital intensity. Getting it right the first time matters less than having the resources to iterate quickly.

These lessons apply beyond fusion: biotech, materials science, hard tech generally. Credibility, standing on proven work, aligned partnerships, clear timelines, and sufficient capital are the fundamentals.

The Future of Fusion Funding: Is the Boom Sustainable?

We're in a fusion funding boom. Over $10 billion has been invested. Dozens of companies are raising hundreds of millions. Is this sustainable?

In the short term, yes. Climate change isn't going away. Venture capital has dried up in some sectors (crypto, consumer tech) but not in climate and energy. Government funding for fusion continues. Big tech companies (Google, Microsoft) are investing because they need clean power. That's a structural tailwind.

Medium term, it depends on execution. If fusion companies start demonstrating progress toward commercial power, funding will accelerate. If multiple companies hit technical roadblocks, funding will tighten. Investors will have to pick winners, and that could lead to consolidation.

Long term, fusion will either become a real power source or it won't. If it does, this funding will look cheap. If it doesn't, a lot of money will have been wasted. Venture capital can absorb some losses, but eventually, returns matter. Companies need to achieve milestones and progress toward profitability.

Inertia's 2030 timeline and $450 million funding is a bet that fusion will become real. The next few years will show if that bet is justified.

Counterarguments: Why Fusion Might Not Win

For balance, let's consider why Inertia might fail or why fusion might not dominate energy.

First, renewables are getting cheaper faster than anyone predicted. Solar and wind costs have dropped 90% in the last decade. Battery costs are dropping 10% per year. At this rate, renewables plus storage might be sufficient to decarbonize the grid faster and cheaper than waiting for fusion.

Second, the timeline matters. If Inertia doesn't produce electricity until 2035 or 2040, solar and wind will have already largely solved the problem. First-mover advantages matter only if you move first.

Third, regulatory challenges are real. A new technology that produces radiation (even fusion doesn't produce dangerous neutrons, people associate it with nuclear) will face scrutiny. Public acceptance matters. One accident could derail fusion's reputation.

Fourth, the laser efficiency problem is fundamental. NIF's lasers are only about 10% efficient overall. Even if Inertia improves this, reaching 30-40% efficiency would be a huge achievement. At 10% efficiency, fusion is competing against renewables on the wrong end of the cost curve.

Fifth, scaling beyond the first plant is uncertain. Building one power plant is hard. Building 100 identical power plants and maintaining quality is harder. If construction costs don't drop with volume, the economic case weakens.

These aren't deal-killers. They're realistic concerns. Inertia has to solve all of them to achieve commercial success. That's a high bar.

The Convergence of Technologies: Why Now Is Different

Fusion has been "30 years away" for decades. Why is now actually different?

A few things have converged. First, lasers have improved dramatically. Laser technology has benefited from decades of incremental improvement in other applications. Inertia inherits that progress.

Second, materials science has improved. You need materials that can withstand extreme temperatures and radiation. Modern materials are better than materials of 20 years ago. That enables better reactor designs.

Third, computing power has increased. Simulating fusion reactions requires massive computation. What took weeks to simulate in 2000 takes hours now. Better simulation enables better designs.

Fourth, manufacturing has improved. Precision manufacturing, automation, quality control. The infrastructure to mass-produce components exists now in a way it didn't 20 years ago.

Fifth, climate change has created urgency. Governments are investing in clean energy. Corporations need power. Investors see opportunity. That creates capital and will to solve hard problems.

Sixth, NIF proved it works. That's the permission to believe.

Take away any one of these factors, and fusion is still decades away. Together, they create a moment where fusion becomes possible. That's why the funding is happening now. It's not irrational exuberance. It's convergence of technology and necessity.

The Personal Bet: What Founders Are Risking

Lawson, Kircher, and Dunne are betting their reputations and probably significant personal capital on Inertia. Lawson made substantial money from Twilio, so he can afford to risk it. But if Inertia fails, it becomes a footnote in his career. If it succeeds, it could be bigger than Twilio.

Kircher is leaving or significantly reducing her position at NIF to pursue this. She's risking a stable government job for startup equity. That's a real risk. If Inertia fails, coming back to NIF might be awkward.

Dunne is a Stanford professor committing time and reputation. If the company fails, that could affect his academic standing and future opportunities.

These are smart, talented people betting that they can commercialize fusion. They're not naive. They know the risks. But they believe the upside justifies the bet.

That's what venture capital rewards: smart people betting on hard problems with credible execution plans.

Looking Forward: The Next Decade

The next decade will be fascinating for fusion. We'll see if Inertia's timeline is realistic. We'll see if other companies hit the same roadblocks or find different paths. We'll see if climate change, regulatory pressure, and energy demand continue driving capital into fusion.

In the best case, we'll have commercial fusion power by 2035. We'll be looking at a next generation of power plants that are cleaner and potentially cheaper than current alternatives. We'll be thinking about how to integrate fusion into the grid, how to scale manufacturing, how to train operators.

In a more realistic case, we'll have demonstrations of working fusion systems, but commercial deployment will take longer. First plants will be expensive. The second, third, and fourth plants will be cheaper. We'll gradually prove the model works and scale from there.

In the worst case, we'll hit unexpected technical roadblocks. Efficiency improvements plateau. Manufacturing can't reach cost targets. Regulatory barriers slow deployment. In that scenario, fusion remains 30 years away for another 30 years.

Inertia's $450 million funding and 2030 timeline suggest the founders and investors believe the best case is possible. That's a bet worth watching.

Fusion has always been the future energy source. The question has always been: when? Inertia and other startups funded by serious venture capital are saying: soon. The next few years will tell if they're right.

FAQ

What is inertial confinement fusion?

Inertial confinement fusion is a fusion approach where lasers (or other energy sources) compress fuel pellets so rapidly that the atoms inside fuse and release energy. The idea is that the fuel's own inertia keeps it compressed long enough for fusion reactions to occur, distinguishing it from magnetic confinement which uses magnetic fields to hold plasma steady. This approach was proven at the National Ignition Facility in December 2022.

How does Inertia's fusion reactor differ from traditional nuclear fission reactors?

Inertia's reactors use fusion (combining hydrogen isotopes) rather than fission (splitting uranium). Fusion reactions produce no long-lived radioactive waste, no carbon emissions, and are inherently safer because the reaction naturally stops if containment is lost. Inertia aims to use abundant hydrogen isotopes from seawater as fuel, whereas fission requires mined uranium. The main advantage is clean, abundant energy from globally available fuel.

What are the main technical challenges Inertia faces to commercialize fusion power?

Inertia must solve several interconnected problems: building high-efficiency lasers that can fire 10 times per second reliably, developing manufacturing processes to produce fuel targets at $1 each instead of thousands of dollars, improving overall laser efficiency (currently about 10%) to achieve useful net energy output, achieving consistent high-yield fusion reactions under repeated industrial operation, and navigating regulatory approval and grid interconnection requirements for a novel power generation technology.

Why is NIF's fusion breakthrough significant for startups like Inertia?

The National Ignition Facility's December 2022 achievement of fusion energy gain (more energy out than input) proved that inertial confinement fusion works in practice, not just theory. This shifted investor and scientific focus from "will this ever work" to "who can commercialize this fastest." For Inertia, it validates their chosen technology path and provides a proven foundation for engineering optimization.

What is the timeline for Inertia to produce electricity to the grid?

Inertia has stated it will begin construction on a grid-scale power plant in 2030. Construction typically takes 5-7 years for power plants, suggesting electricity generation around 2035-2037. However, this timeline is aggressive for fusion technology, which historically has experienced delays. Success depends on solving engineering challenges and obtaining regulatory approval within the stated schedule.

How does Inertia's funding compare to other fusion startups?

At

What happens if Inertia's approach doesn't work as planned?

Fusion is littered with missed timelines and technical setbacks. If Inertia encounters efficiency plateaus, manufacturing challenges, or unexpected physics limitations, they might redirect toward demonstration projects rather than commercial power plants, license their technology to other companies, or pivot to different applications. The venture capital model assumes some failures; the question is whether they achieve enough progress to justify the investment.

How does fusion energy production compare economically to renewables and current nuclear power?

Fusion's fuel costs would be minimal (hydrogen isotopes from seawater), but the capital cost of building reactors is uncertain. If Inertia achieves their cost targets, fusion could compete with nuclear on lifetime cost per megawatt-hour. However, solar and wind costs are dropping faster than anyone predicted. The economic race depends on whether fusion deployment accelerates faster than renewable costs fall and battery storage matures.

What role do government labs play in Inertia's success?

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and NIF provide foundational research, proof-of-concept validation, and institutional expertise. Inertia's co-founders maintain ties to these labs, likely enabling access to research infrastructure and personnel that accelerates development. Government labs benefit from seeing their research commercialized, creating aligned incentives. This public-private partnership reduces technical risk compared to startups inventing from scratch.

Why is Jeff Lawson, Twilio's founder, betting on fusion instead of pursuing another software company?

Lawson has already built a successful, public company and accumulated significant capital. Fusion represents a hard problem with massive societal impact and trillion-dollar market potential. For experienced founders, the appeal often shifts from incremental improvement in proven markets to solving fundamental challenges. Fusion offers that opportunity: if successful, it could transform global energy infrastructure. That's a different scale of impact than communications software.

Key Takeaways

- Inertia Enterprises raised $450M Series A backed by Bessemer Venture Partners and GV to commercialize laser-powered fusion reactors based on NIF's proven breakthrough

- The company plans to start construction on a grid-scale power plant in 2030 with electricity generation targeted by 2035, using 1,000 lasers firing 10 times per second at $1 fuel targets

- Inertia's co-founders bring proven execution: Jeff Lawson built Twilio, Annie Kircher conducted NIF's fusion breakthrough experiments, and Mike Dunne designed the power plant architecture

- Fusion startups have attracted over $10 billion in venture funding as NIF's 2022 breakthrough shifted focus from theoretical feasibility to commercial engineering challenges

- The key technical challenges center on laser efficiency improvement, mass-producing fuel targets, achieving consistent high-yield reactions, and navigating regulatory approval for novel power generation technology

Related Articles

- Venture Capital Split Into Two Industries: SVB 2025 Report Analysis [2025]

- Meridian AI's $17M Raise: Redefining Agentic Financial Modeling [2025]

- Apptronik $935M Funding: Humanoid Robots Reshaping Automation

- AI Rivals Unite: How F/ai Is Reshaping European Startups [2025]

- Thomas Dohmke's $60M Seed Round: The Future of AI Code Management [2025]

- India's Deep Tech Startup Rules: What Changed and Why It Matters [2025]

![Inertia Fusion: $450M Funding Boom and the Race to Grid-Scale Power [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/inertia-fusion-450m-funding-boom-and-the-race-to-grid-scale-/image-1-1770827811947.jpg)