COVID-19 Cleared Skies but Supercharged Methane: The Atmospheric Paradox

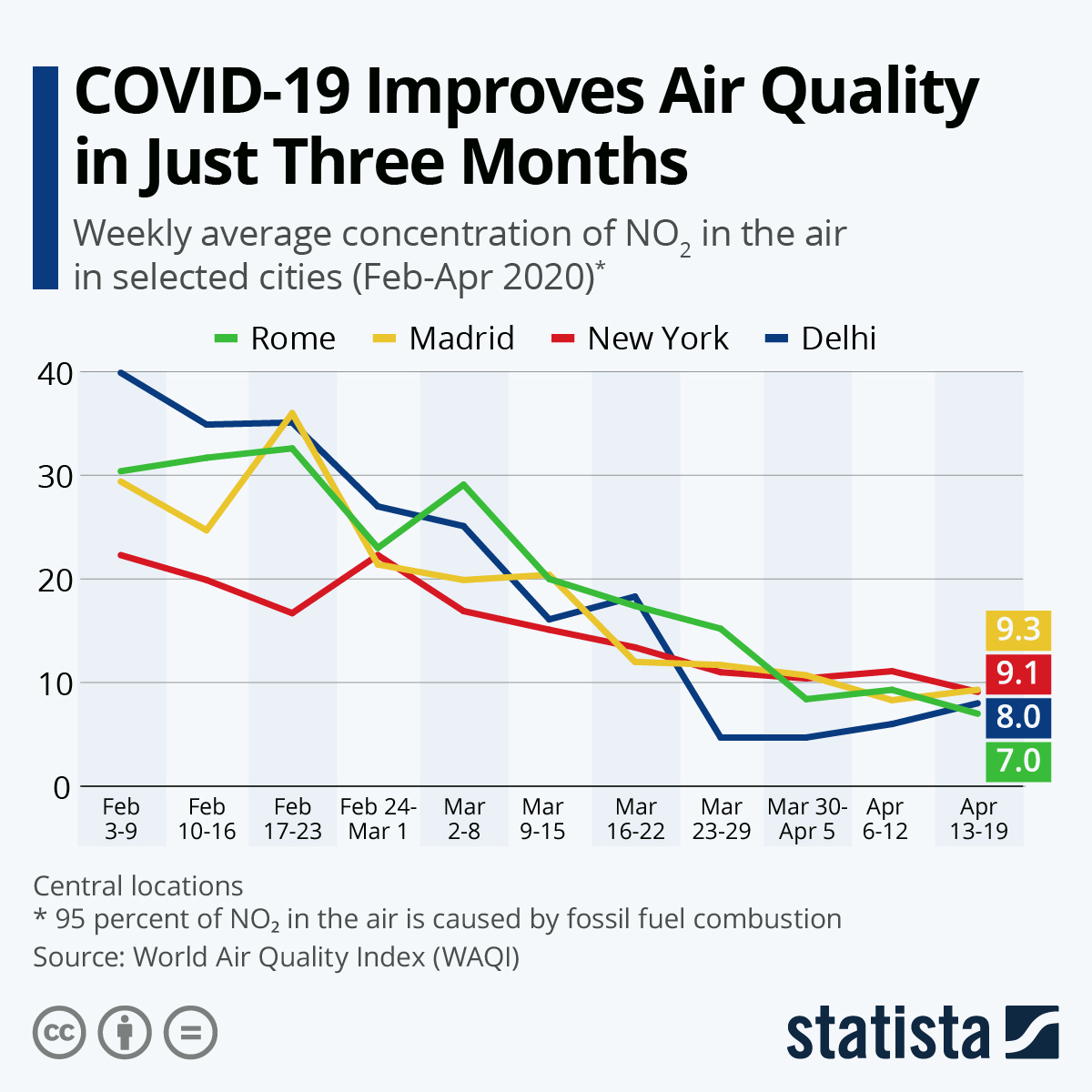

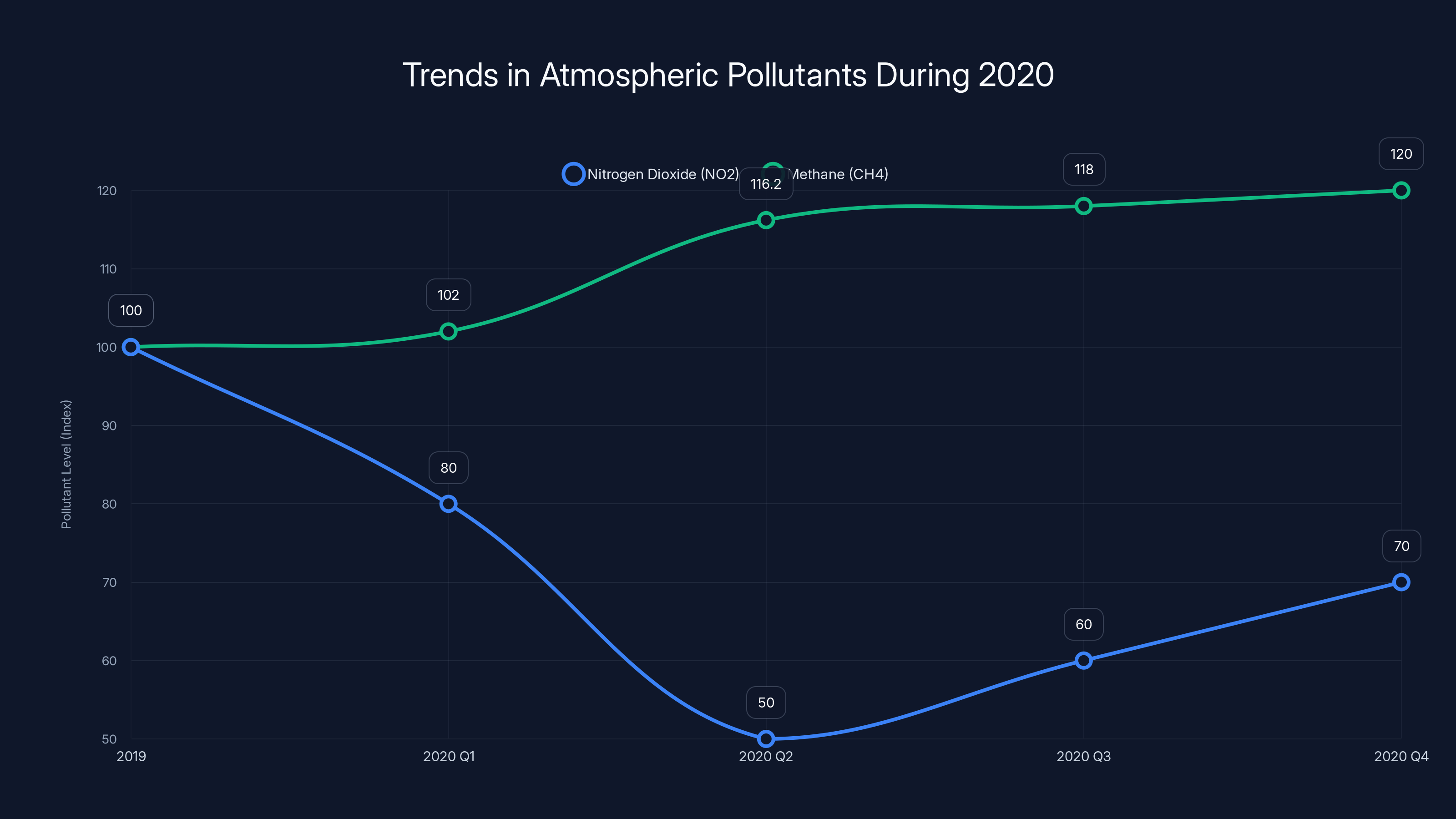

When the world shut down in spring 2020, something remarkable happened. Satellite sensors watching our planet detected a dramatic collapse in nitrogen dioxide, the acrid pollutant that paints cities brown and burns throats during rush hour. Highways emptied. Factories powered down. Ships sat idle in ports. For a fleeting moment, the air quality improved in ways climate scientists had been modeling for decades but had never actually observed at such a massive scale.

Then something deeply unsettling occurred.

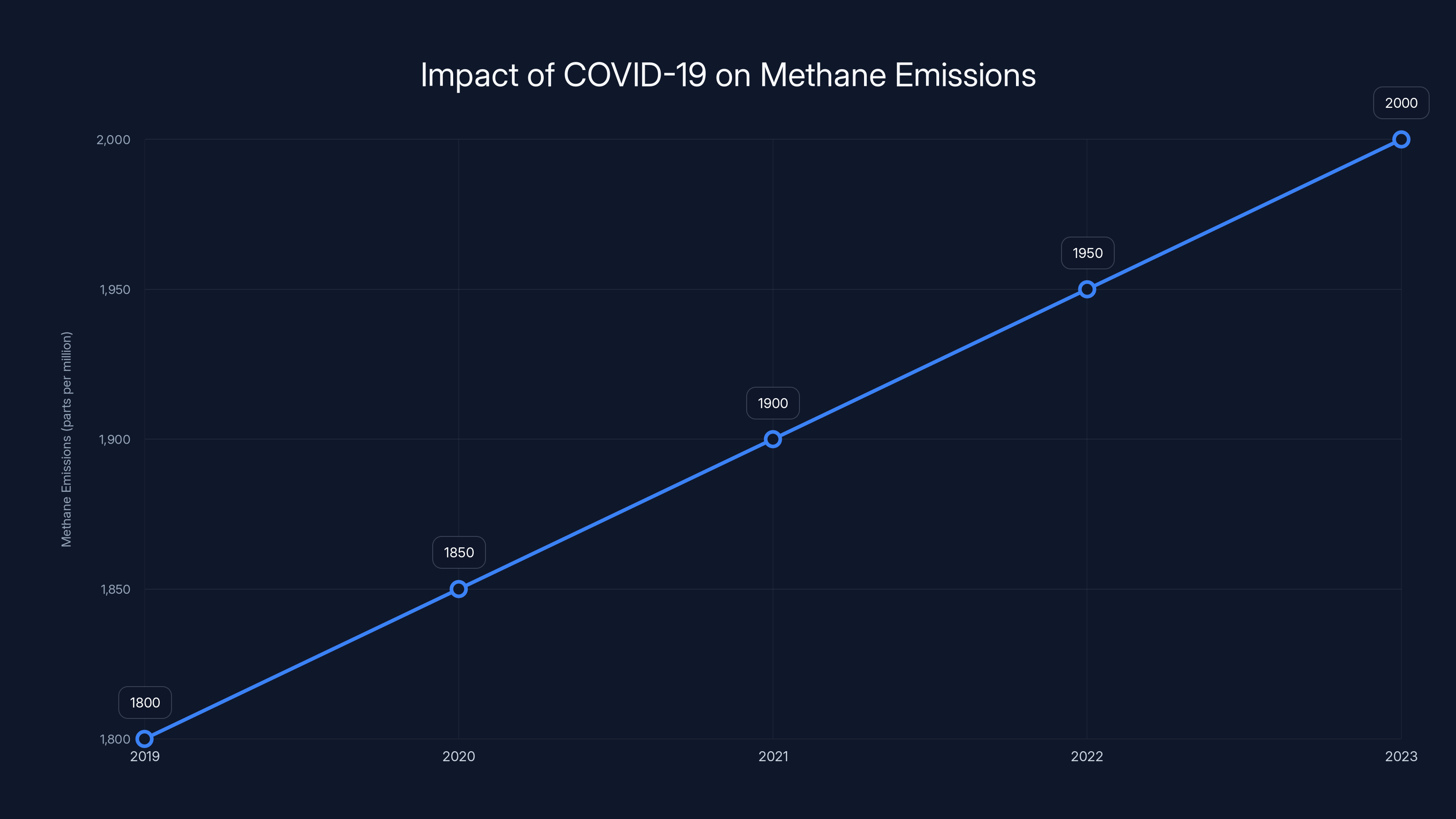

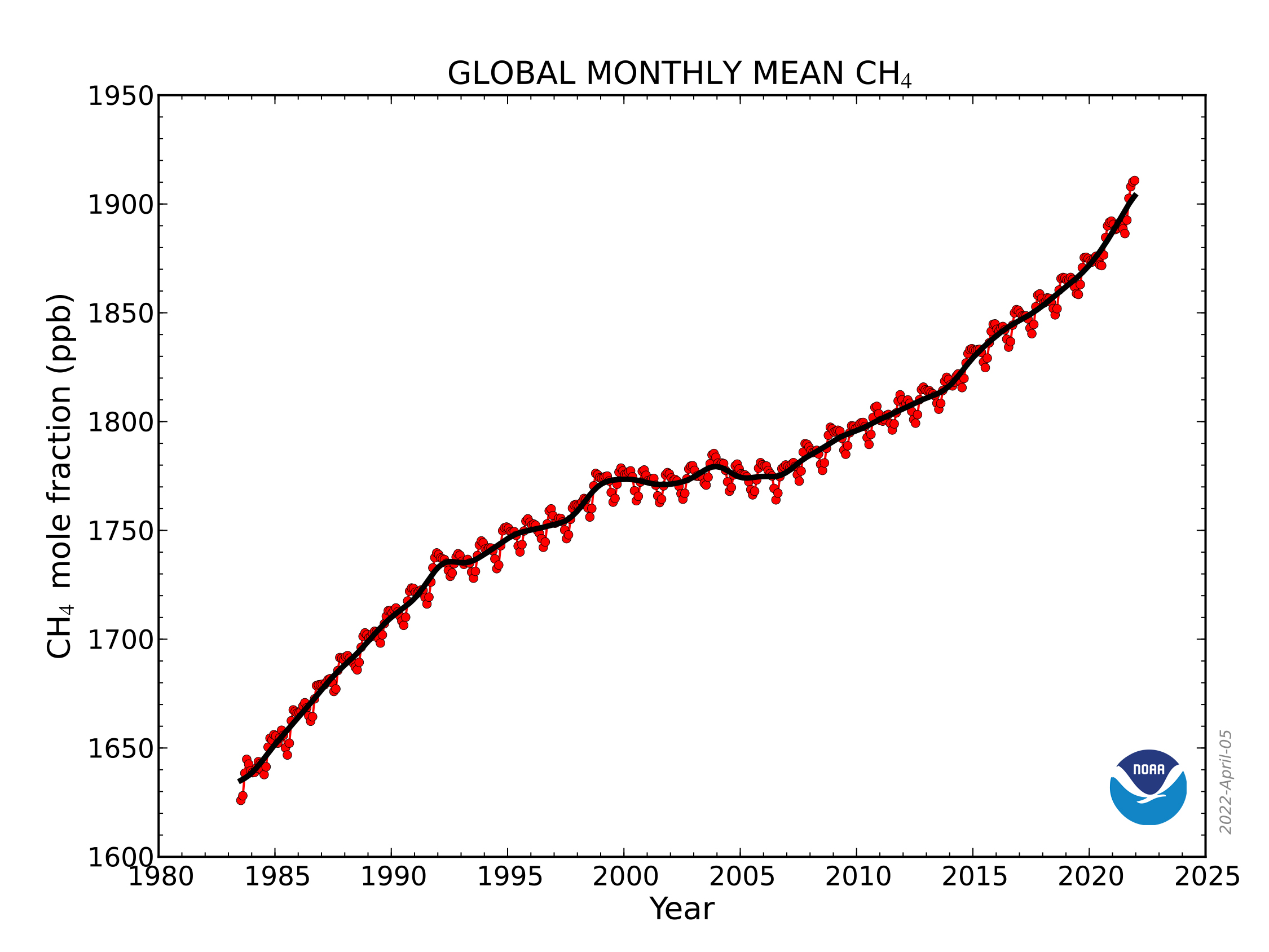

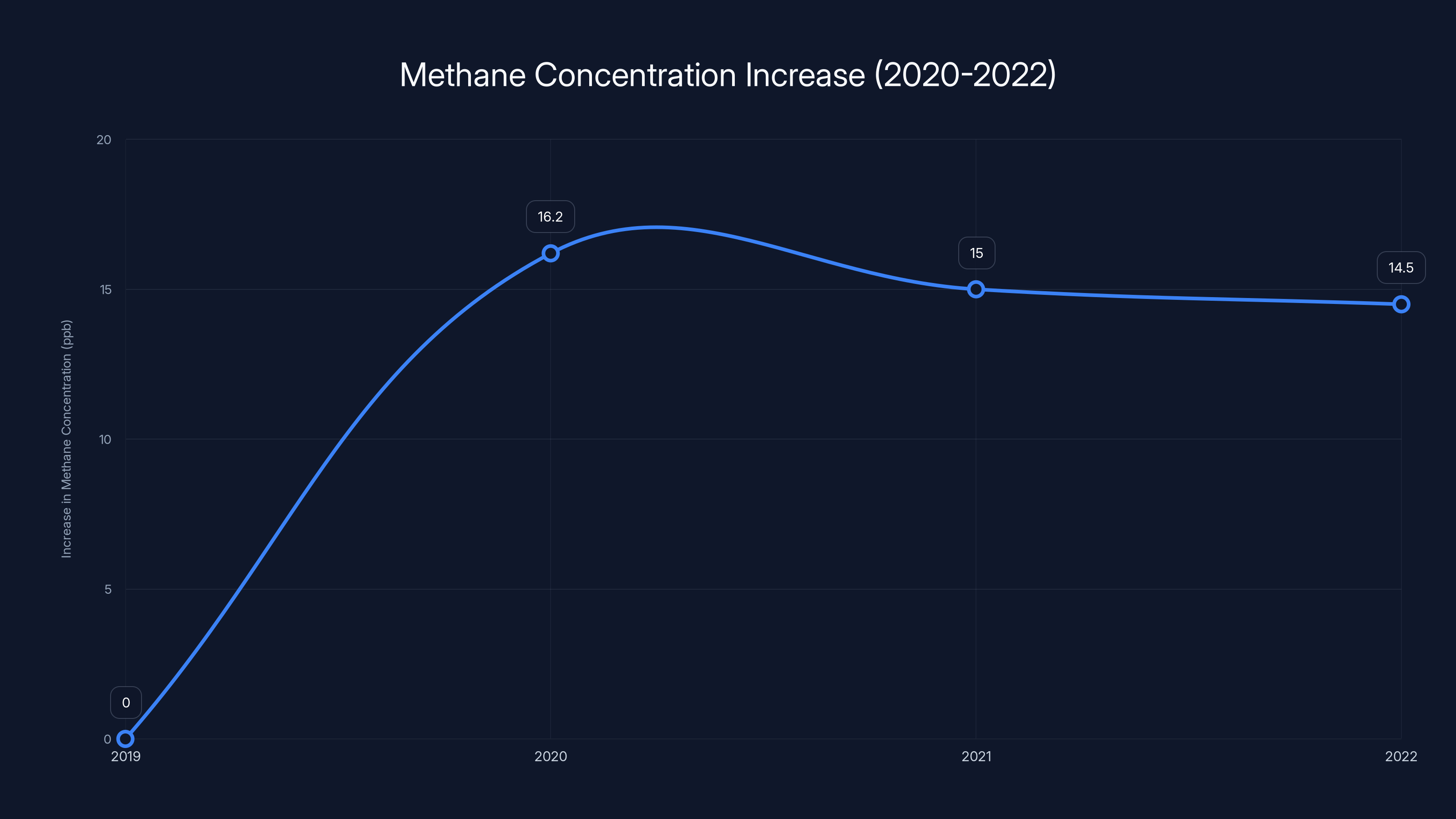

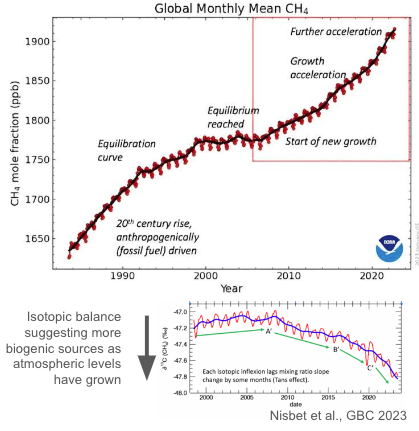

While nitrogen dioxide plummeted, methane started climbing. Not gradually, the way it had been creeping upward for years. But sharply. Aggressively. The growth rate hit 16.2 parts per billion in 2020—the highest spike since scientists started keeping systematic records in the early 1980s. This wasn't supposed to happen. Cleaner air should mean less warming, not more.

A groundbreaking study published in the journal Science untangled this paradox, revealing a truth that shook the foundations of how we understand atmospheric chemistry. The pandemic's gift of cleaner skies had come with a hidden cost. By reducing the very pollutants we've spent decades fighting to eliminate, we'd inadvertently weakened the atmosphere's natural ability to destroy methane. And that weakness allowed this far more potent greenhouse gas to linger and accumulate.

This isn't just a curiosity about what happened during 2020. It's a window into a profound challenge that humanity faces as we transition away from fossil fuels. The more we clean the air, the weaker our natural methane scrubber becomes. Fix one problem, and you risk making another worse. It's a clean air paradox that could reshape how we think about climate policy for decades to come.

The Methane Mystery That Started in 2020

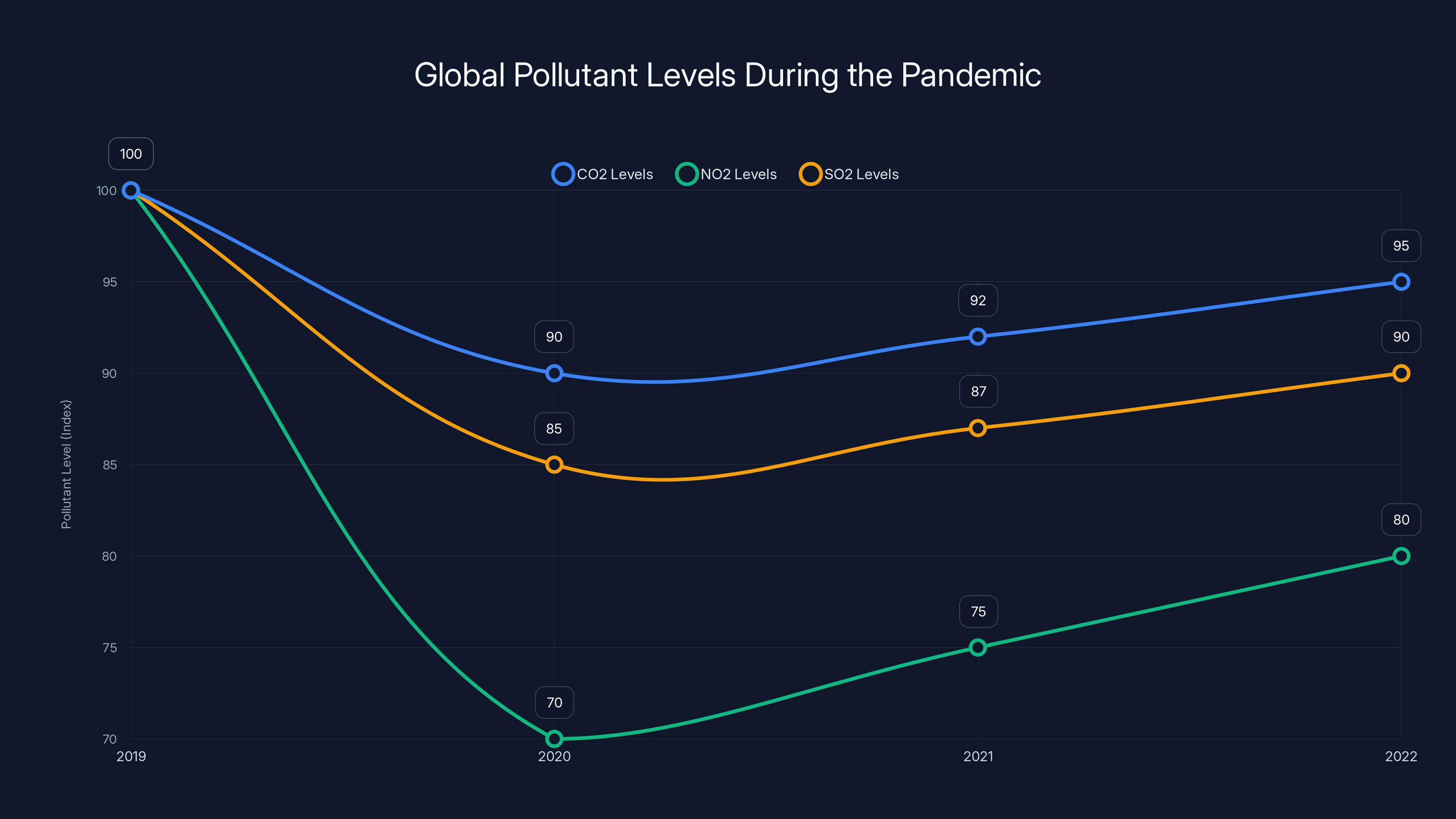

For weeks after the initial lockdowns began, scientists watched the data in disbelief. Nitrogen dioxide concentrations dropped roughly 15 to 20 percent globally—a reduction so dramatic that it would take conventional air quality improvements decades to achieve. In major cities like Beijing, Delhi, and Los Angeles, the improvement was even more pronounced, with some areas seeing nitrogen dioxide levels cut nearly in half.

Yet methane told a different story. While most pollution indicators declined sharply, methane concentrations climbed steadily through 2020, 2021, and into 2022. The growth rate wasn't just elevated—it was historic. The 16.2 parts per billion increase in 2020 shattered the previous record of 13.2 parts per billion set in 2014, an event that had already alarmed climate scientists.

Initially, researchers had competing theories about where this methane surge originated. Some pointed to oil and gas operations, theorizing that pandemic-related shutdowns might have caused infrastructure failures, leaky valves, and abandoned maintenance routines. Super-emitter events in gas fields seemed plausible. Others suspected landfills and wastewater treatment plants operating with reduced oversight. A few researchers even hypothesized that the unusual atmospheric conditions created by the absence of normal aerosol patterns might somehow be amplifying methane's concentration.

But the real answer turned out to be far more complicated than any single source. It required looking at atmospheric chemistry itself—specifically, at one of the shortest-lived but most crucial molecules in Earth's atmosphere.

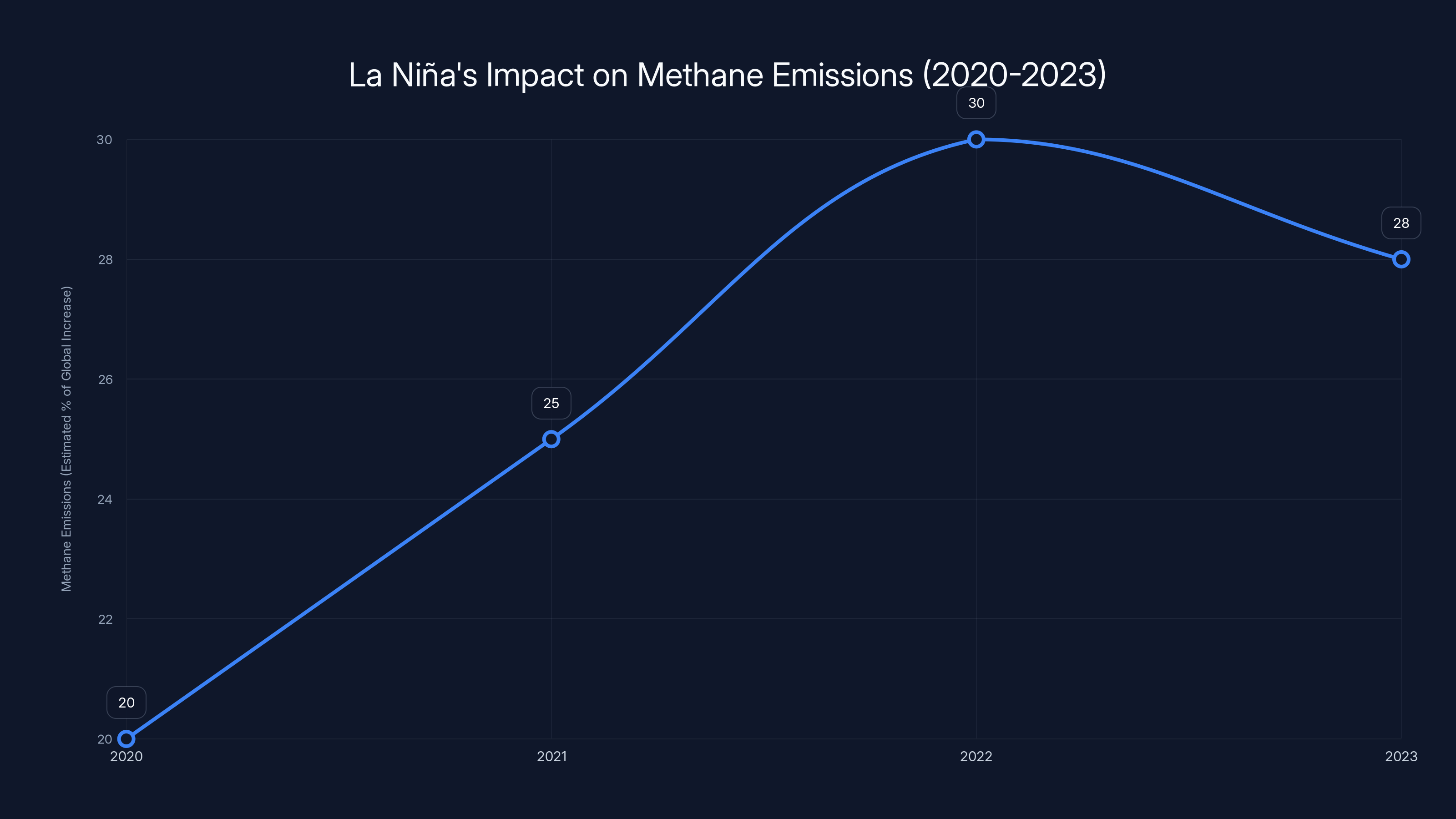

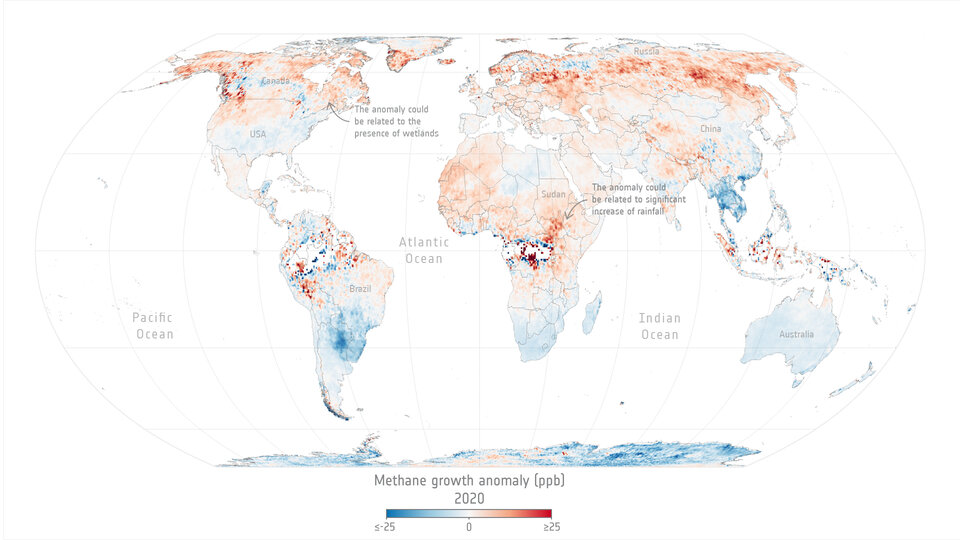

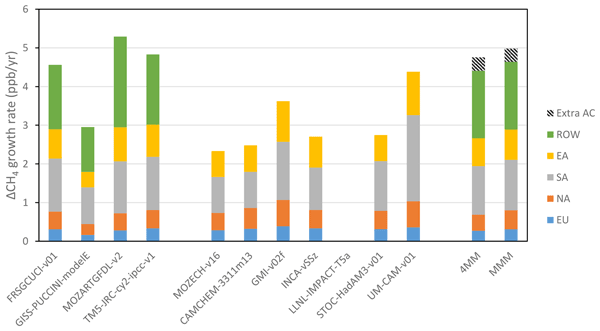

Methane emissions increased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic due to reduced nitrogen oxide emissions and La Niña-induced wetland flooding. Estimated data.

The Hydroxyl Radical: The Atmosphere's Invisible Janitor

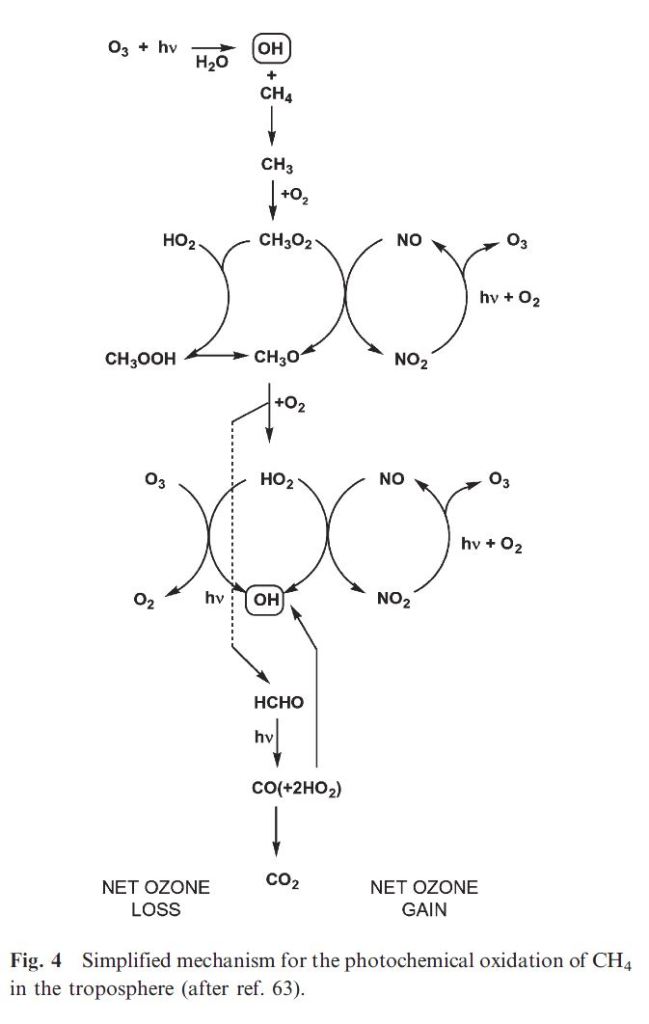

Since the late 1960s, atmospheric chemists have known something remarkable. Methane doesn't just stay in the atmosphere indefinitely, slowly leaking out to space or being removed by obscure processes. Instead, it gets scrubbed out by a highly reactive molecule called the hydroxyl radical (OH).

Think of hydroxyl radicals as the atmosphere's cleaning crew. They patrol the troposphere—the lowest region of the atmosphere where weather happens—and systematically destroy methane molecules, breaking them apart and converting them into water vapor and carbon dioxide. One hydroxyl radical encounters methane, breaks its bonds, and both molecules transform into something else. Then that hydroxyl radical is consumed in the process.

This is where things get fascinating. The hydroxyl radical has an extraordinarily short lifespan. As Shushi Peng, a professor at Peking University and a lead author of the Science study, explains, its existence lasts less than a single second. Less than a second to do its job before it ceases to exist.

This means that the atmosphere needs a constant, uninterrupted supply of freshly created hydroxyl radicals to maintain its ability to destroy methane. Without continuous replenishment, the methane-scrubbing capacity collapses. And hydroxyl radicals don't spontaneously appear from nothing. They're created through a series of interconnected chemical reactions, all triggered by one essential ingredient: sunlight.

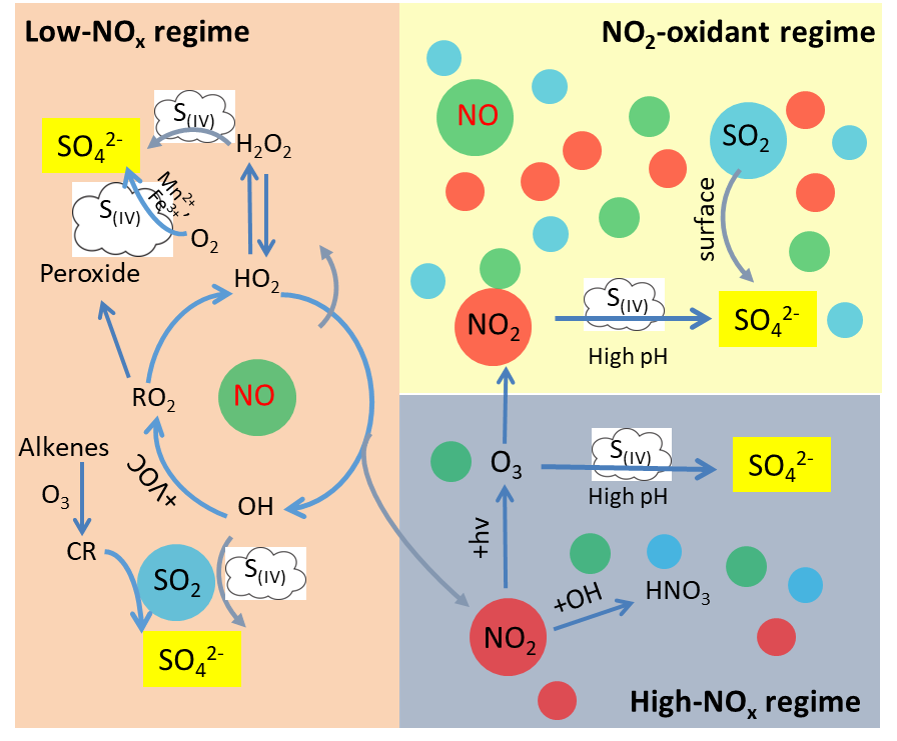

The Nitrogen Oxide Connection: Where Pollution Helps Clean Air

Here's where the paradox begins to crystallize. The chemical reactions that create hydroxyl radicals require nitrogen oxides as essential catalysts. Nitrogen oxides—those same pollutants that cause smog, acid rain, and respiratory disease—are actually necessary for the atmosphere to produce the molecules that destroy methane.

Before 2020, nitrogen oxide concentrations were elevated across the globe due to combustion from vehicles, power plants, and industrial facilities. These were hardly welcome emissions. They're serious air pollutants linked to asthma, heart disease, and premature death. But from the perspective of atmospheric methane destruction, they served a critical function. They were feeding the production line of hydroxyl radicals.

When lockdowns arrived and the world's vehicles largely stopped moving, factories powered down, and power generation shifted, nitrogen oxide levels plummeted. This is celebrated as a victory for air quality. Fewer people breathing toxic fumes is objectively good. But simultaneously, the reduction in nitrogen oxides slowed the creation of hydroxyl radicals.

Without sufficient nitrogen oxides driving the hydroxyl radical production reactions, the atmosphere's methane-destroying capacity diminished. The cleaning crew suddenly had far fewer workers on shift. Methane molecules that would have normally survived only 7 to 10 years in the atmosphere before being destroyed now lingered even longer. They accumulated.

Peng and his research team calculated that this reduction in the methane sink—this weakened destruction capacity—accounted for approximately 80 percent of the massive spike in methane growth rate observed in 2020. That's the clean air paradox in its starkest form. Reduce pollutants that harm human health directly, and you simultaneously reduce the atmosphere's ability to destroy a greenhouse gas that harms the entire climate system.

Methane concentrations rose significantly from 2020 to 2022, with a record increase of 16.2 ppb in 2020. Estimated data shows continued growth in subsequent years.

Following the Isotopic Trail: Where the Extra Methane Really Came From

While the weakened hydroxyl radical sink explained most of the 2020 surge, it wasn't the only factor. About 20 percent of the 2020 increase, and an even larger proportion of the growth continuing into 2021 and 2022, came from somewhere else. The actual emissions of methane from the ground were increasing.

Finding the source required detective work worthy of a forensic investigation. Methane comes in different forms—different isotopic signatures that reveal its origin. This is crucial because methane from different sources has distinct chemical fingerprints.

Methane derived from fossil fuels—leaking natural gas pipelines, coal mining operations, oil field emissions—contains a higher proportion of the heavier carbon-13 isotope. It's literally weightier, in the isotopic sense. Conversely, methane produced by microbes contains more of the lighter carbon-12 isotope. This biogenic methane comes from bacteria in livestock guts, in landfills, in rice paddies, and most prominently, in wetlands where anaerobic microorganisms thrive.

Peng's team analyzed measurements from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's global flask network—a worldwide system of monitoring stations that continuously sample and analyze the chemical composition of Earth's atmosphere. They specifically examined the isotopic composition of atmospheric methane during the surge years.

The data revealed something striking. The methane in the atmosphere was becoming significantly lighter in isotopic composition, enriched in carbon-12. This was the smoking gun. The extra methane surging into the atmosphere wasn't coming from oil and gas infrastructure. It wasn't escaping from leaky pipes or abandoned equipment. It was coming from microbes—from the biological production of methane in wetlands.

La Niña's Influence: When Climate Patterns Amplify Emissions

The timing of this microbial methane surge wasn't random. Something extraordinary was happening to Earth's weather systems in the early 2020s. A meteorological phenomenon called La Niña had emerged—the cool phase of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation that typically brings increased rainfall to tropical regions.

But La Niña didn't just appear in one year and fade. It persisted. Three consecutive Northern Hemisphere winters, from 2020 through 2023, saw La Niña conditions. For the tropical regions, this meant rainfall at levels well above historical averages. The early 2020s became exceptionally wet.

Using satellite data and sophisticated atmospheric models, Peng's team traced the origin of this biogenic methane signature to massive wetland complexes in tropical regions. The Sudd in South Sudan, one of the world's largest freshwater swamps, experienced record flooding. The Congo Basin in Central Africa saw vast expanses of normally dry land submerged under water. Southeast Asian wetlands similarly experienced exceptional inundation.

In these waterlogged, oxygen-poor environments, microbial methanogens thrived. Methanogens are a class of bacteria that produce methane as a metabolic byproduct. They flourish in anaerobic conditions—places without oxygen—where they break down organic matter and release methane. With more wetland area flooded, more habitat for methanogens became available. With warmer temperatures and continuous water coverage, these microbes worked at accelerated rates.

The research suggests that tropical African and Asian wetlands alone were responsible for approximately 30 percent of the global methane emissions increase during the 2020 to 2022 period. That's a staggering contribution from one source category. The data points to a clear cascade: La Niña brought rain, rain flooded wetlands, flooded wetlands amplified microbial methane production, and that methane remained in the atmosphere longer because hydroxyl radicals were scarce.

The Methane Lifetime Problem: Why Shorter Isn't Always Better

Methane has long been positioned as the "low-hanging fruit" of climate policy. Compared to carbon dioxide, methane has a much shorter atmospheric lifetime. Carbon dioxide persists for roughly 300 to 1,000 years, accumulating and staying in the atmosphere across multiple human lifetimes. Methane, by contrast, typically remains in the atmosphere for only 7 to 10 years before being destroyed by hydroxyl radicals.

This shorter lifetime has been celebrated as an advantage. The logic goes: if we stop methane emissions today, the methane already in the atmosphere will be cleared away within a decade. No millennia-long commitment to atmospheric burden. No multi-generational climate debt. Just a 7 to 10 year clearing period, and the methane problem largely vanishes.

This framing drove policy discussions about rapid methane reduction targets. Many nations and organizations committed to aggressive methane cuts, reasoning that stopping methane emissions would produce faster climate benefits than focusing solely on carbon dioxide reduction. It made intuitive sense and aligned with the urgency of the climate crisis.

But Peng's research introduces a complication into this straightforward narrative. The methane lifetime isn't a fixed property of physics that we can simply ignore. It depends fundamentally on something outside our direct control: the availability of hydroxyl radicals. And hydroxyl radical availability is interconnected with air pollution.

Estimated data shows a significant increase in methane emissions from tropical wetlands during consecutive La Niña years, peaking in 2022. Estimated data.

The Clean Air Paradox: Facing An Uncomfortable Trade-Off

As we transition away from fossil fuels and improve urban air quality globally, we'll inevitably reduce nitrogen oxide concentrations. This is unequivocally positive for public health. Fewer nitrogen oxides means less smog, less respiratory disease, fewer premature deaths from air pollution.

But the clean air paradox emerges from the research: as nitrogen oxides decline, the production of hydroxyl radicals will also decline. Our atmosphere's natural capacity to scrub methane will diminish. We'll face a situation where the methane in the air sticks around longer, persists more stubbornly, and accumulates in the atmosphere more readily.

This creates a genuine tension in climate strategy. Policies that improve air quality—which is essential for human health and remains a legitimate priority—may simultaneously reduce the atmosphere's ability to destroy methane, a potent greenhouse gas. We could find ourselves in a position where cleaning the air paradoxically makes the climate problem harder to solve.

The implications are profound. We can't simply turn off methane emissions. We can't switch off fossil fuel use without also reducing nitrogen oxides. These systems are interconnected in ways that linear climate thinking often misses.

Climate Feedbacks: The Biological Time Bomb

Beyond the atmospheric chemistry puzzle, there's another layer of complexity that keeps climate scientists awake at night. The research suggests that climate feedbacks could amplify methane emissions in ways we can't simply control.

Warmth itself changes the behavior of wetlands. As global temperatures rise, wetland productivity increases. More plant growth occurs in wetland environments. When that plant material decays in oxygen-poor conditions, it generates methane. Warmer temperatures also accelerate microbial metabolism, meaning the methanogens work faster and produce more methane per unit of organic matter decomposed.

Changing precipitation patterns add another layer. If climate change alters rainfall patterns such that tropical wetlands become wetter and more extensive, methane emissions from those regions will increase. If monsoon patterns shift, if hurricane frequency changes the distribution of water, if snowmelt timing alters seasonal flooding patterns—all of these can amplify or diminish methane emissions from natural sources.

Unlike emissions from human activities, which we can theoretically reduce through policy and technology, natural wetland emissions respond to climate patterns we can influence but not fully control. We can't turn off a wetland the way we can shut down a coal plant. We can't retrofit a rainforest with emissions controls. These are biological systems that respond to temperature, moisture, and atmospheric conditions in ways that often escape our direct management.

Worse, these feedbacks create potential runaway loops. Warming increases methane, methane causes more warming, more warming increases methane further. This isn't hypothetical speculation—it's a straightforward extrapolation of known physics and biology.

The Atmospheric Chemistry Complexity: Multiple Variables, Unexpected Interactions

The hydroxyl radical story illustrates a broader principle about atmospheric chemistry. Our atmosphere isn't a simple system where you can adjust one variable and predict the outcome. Instead, it's a complex web of chemical reactions, photochemical processes, and physical interactions that often produce counterintuitive results.

The relationship between nitrogen oxides and hydroxyl radical production is just one example. There are dozens of other chemical species interacting in ways that remain incompletely understood. Ozone, nitric oxide, nitric acid, peroxides—all participate in the cycles that determine how much hydroxyl radical gets produced and how quickly it removes methane.

Add in variations in sunlight intensity, seasonal patterns, stratospheric processes, ocean-atmosphere interactions, and the system becomes staggeringly complex. A small change in one component can ripple through multiple chemical pathways and produce effects that appear disconnected from the original change.

This complexity is humbling. It suggests that our intuitive understandings of how the atmosphere responds to human activities can be misleading. The pandemic provided an unprecedented natural experiment—a sudden, global-scale reduction in multiple pollutants simultaneous—and the results defied simple expectations.

Estimated data shows a significant drop in global pollutant levels during the pandemic, with gradual increases as activities resumed. The pandemic period provided unique insights into atmospheric chemistry.

Regional Variations: Why Methane Doesn't Rise Uniformly

While the global methane increase was dramatic, the surge wasn't evenly distributed across Earth's regions. Tropical wetlands contributed disproportionately, as the research emphasized. But different regions experienced different pressures and responded differently.

Tropical regions experienced both strong La Niña effects and generally high temperatures, creating ideal conditions for microbial methane production. The flooded wetlands in Africa and Southeast Asia became biological methane factories operating at peak capacity.

Middle and higher latitudes experienced some methane increase, but from different sources and at different magnitudes. Siberian wetlands and other permafrost-adjacent ecosystems showed some acceleration in methane emissions, though the La Niña effect was less pronounced in northern regions. Some of the increase in temperate and boreal zones likely came from shifting agricultural practices and livestock management, which changed during and after the pandemic.

Ocean regions showed different patterns still. Some marine regions experiencing unusual thermal conditions and circulation patterns saw methane emissions from hydrate deposits or bacterial activity shift. The global ocean itself acts as both a sink and source for atmospheric methane, and these fluxes changed in complex ways during the pandemic period.

No single global number tells the whole story. Instead, a patchwork of regional changes combined to produce the global surge. Understanding those regional variations matters because it means our mitigation strategies need to be equally nuanced and regionally tailored.

Isotopic Analysis: A Window Into Methane's Molecular Secrets

The isotopic detective work deserves deeper exploration because it represents the kind of sophisticated atmospheric chemistry that modern climate science employs. Isotopes are atoms of the same element with different numbers of neutrons—different masses, but same chemical behavior.

Carbon has two stable isotopes: carbon-12, which is lighter and far more common, and carbon-13, which is heavier and comprises about 1 percent of natural carbon. When methane forms in different environments, the ratio of carbon-12 to carbon-13 in the resulting methane varies based on the source process.

Fossil methane—from oil and gas deposits formed hundreds of millions of years ago—is enriched in carbon-12 because the biological processes that created it preferentially incorporated the lighter isotope. Modern biogenic methane produced by current bacteria similarly favors carbon-12, but sometimes to slightly different degrees depending on the specific metabolic pathway and environmental conditions.

When atmospheric chemists measure the isotopic ratio of atmospheric methane, they're essentially reading the methane's biographical history. A heavier isotopic signature points toward fossil fuel sources. A lighter signature points toward biological sources. By comparing the isotopic changes during the pandemic surge to baseline values, Peng's team could quantify what proportion came from each source category.

The finding that atmospheric methane became lighter—richer in the biological carbon-12 signature—was definitive. It meant roughly 20 percent of the 2020 surge and even larger proportions of the 2021-2022 increases came from natural biological sources rather than fossil fuel leakage.

The Global Monitoring Network: How Scientists Track What We Can't See

Behind every conclusion in Peng's study sits an infrastructure of monitoring and measurement. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's global flask network comprises dozens of stations distributed across continents and oceans. At these stations, staff periodically collect air samples in specially prepared flasks, carefully avoiding contamination and ensuring proper preservation.

These samples get shipped to central laboratories where instruments measure their chemical composition with extraordinary precision. The same infrastructure has been operating continuously since the 1980s, creating a decades-long record of atmospheric composition. This continuity matters because it allows scientists to distinguish genuine changes from normal variations.

Satellite observations add another layer. Instruments aboard satellites like the NOAA Greenhouse Gases Observing Satellite provide continuous, global coverage. They can't achieve the precision of ground measurements, but they offer spatial resolution that ground stations alone cannot. By combining satellite data with ground measurements, researchers construct a three-dimensional picture of how methane concentrations vary around the planet.

This monitoring infrastructure represents an enormous investment in understanding our atmosphere. The data it produces is freely available to researchers worldwide, enabling independent verification and novel analyses. It's one of climate science's greatest successes—a global scientific collaboration that transcends national boundaries and produces information of planetary importance.

Estimated data showing how different environmental interventions can have varied impacts across interconnected systems, highlighting the importance of systems thinking.

Policy Implications: Rethinking Emissions Reduction Strategies

The findings force a reconsideration of how we structure climate and air quality policy. Historically, these have been somewhat separate domains. Air quality policy focused on nitrogen oxides, particulate matter, sulfur dioxide, and other local pollutants affecting human health. Climate policy focused on greenhouse gases, particularly carbon dioxide and methane.

But the pandemic research reveals they're interconnected. Reducing emissions that harm air quality will inevitably change the chemistry of the troposphere in ways that affect methane destruction. This doesn't mean we should stop reducing nitrogen oxides—the public health costs of air pollution are enormous and immediate. Rather, it means we need to account for these atmospheric chemistry effects when designing our climate mitigation strategies.

One approach involves considering how we reduce nitrogen oxides. Instead of simply shutting down all sources simultaneously, we might prioritize different sources differently. For example, shifting to electric vehicles reduces nitrogen oxides from transportation while preserving nitrogen oxides from other industrial sources that might be essential for maintaining hydroxyl radical production. It's not about keeping pollution, but about being strategic about which sources we target first and how quickly we reduce them.

Another implication involves methane reduction targets. If methane remains in the atmosphere longer due to reduced hydroxyl radical availability, the same reduction in emissions will produce smaller near-term climate benefits. This doesn't mean methane reduction becomes less important—it remains crucial. But it means we need aggressive action on multiple fronts simultaneously, not sequential strategies focused on single pollutants.

A third consideration involves natural emissions. Since a significant portion of the methane surge came from natural wetlands responding to climate patterns, managing climate change becomes intertwined with managing methane. We can't completely separate climate mitigation from methane mitigation when climate feedbacks amplify methane emissions.

Future Methane Emissions: Trends and Uncertainties

Looking forward, methane emissions face multiple pressures working in different directions. On one side, efforts to reduce fossil fuel use and improve energy efficiency should reduce anthropogenic methane emissions from oil and gas operations, coal mining, and agricultural sources.

On the other side, climate warming and changing precipitation patterns will likely increase natural methane emissions from wetlands, especially in tropical and Arctic regions. As permafrost thaws in the Arctic, previously frozen soil containing vast amounts of organic matter will become accessible to microbial decomposition. Methanogens will colonize thawing permafrost, producing methane at rates we haven't observed in recent human history.

The balance between these opposing trends will determine whether atmospheric methane concentrations eventually stabilize, continue increasing, or begin declining. Currently, the trajectory points toward continued increases, though at rates that vary year to year based on climate patterns and human activity.

The La Niña events of 2020 to 2023 were unusual. The next few years will likely see different climate patterns—possibly El Niño conditions bringing drier weather to tropical regions. Drier conditions could reduce wetland methane emissions significantly. But this would be temporary relief rather than a solution. The long-term trend, absent major changes in human civilization and climate trajectory, points toward continued or even accelerated natural methane emissions.

The Methane-Climate Feedback Loop: A Potential Runaway Scenario

Climate science has long worried about positive feedback loops—scenarios where warming causes changes that produce even more warming, creating a self-reinforcing spiral. The methane cycle presents exactly this kind of risk.

Warming → increased wetland productivity and methane emissions → more methane in atmosphere → increased warming → further wetland activation and methane release → even more warming. This cycle could accelerate if thresholds are crossed—for example, if Arctic permafrost thaw reaches a tipping point, it could release enormous quantities of trapped methane currently sequestered in frozen ground.

The research suggests we're potentially entering a phase where natural systems themselves become increasingly important as methane sources. Earlier in the industrial era, methane emissions were dominated by human activities: coal mining, oil and gas extraction, agriculture, waste. The balance is shifting. By mid-century, natural emissions could represent a larger proportion of the total atmospheric burden.

This has profound implications for whether we can actually stabilize atmospheric methane. If human methane emissions decline due to successful climate policy and technological improvement, but natural emissions rise due to climate feedbacks, the net effect could be minimal atmospheric change. We could reduce what we can control while struggling against what we can't.

During 2020, nitrogen dioxide levels dropped significantly due to reduced human activity, while methane levels experienced a sharp increase, highlighting an atmospheric paradox. (Estimated data)

Hydroxyl Radicals in a Cleaner Atmosphere: The Long-Term Outlook

Assuming successful transition to renewable energy and elimination of fossil fuel combustion, nitrogen oxide concentrations will decline substantially from today's levels. This is essential for air quality. But it inevitably means hydroxyl radical production will also decline, at least in the near to medium term.

However, the long-term outlook might be more nuanced. As fossil fuel combustion declines, coal smoke, industrial pollution, and other complex pollutant mixtures will diminish. Some of these compounds interact with tropospheric chemistry in ways that suppress hydroxyl radical production through different mechanisms. Removing them might actually help maintain hydroxyl radical levels even as nitrogen oxides decline.

Additionally, solar radiation and ultraviolet light drive hydroxyl radical production. As we address stratospheric ozone depletion, ultraviolet radiation at the surface will change, potentially affecting production rates. Cleaner stratospheric conditions—fewer ozone-depleting substances—could paradoxically affect tropospheric chemistry in complex ways.

These interactions highlight the irreducible complexity of atmospheric chemistry. We can't simply draw a straight line from "nitrogen oxides decline" to "hydroxyl radicals decline." The full system is more intricate, with multiple interdependencies and feedback mechanisms.

Technology and Innovation: Tools for Managing Atmospheric Chemistry

One frontier in climate science involves developing technologies to manipulate atmospheric chemistry more directly. If hydroxyl radical availability becomes a constraint on methane destruction, could we somehow increase it?

Some researchers explore atmospheric chemistry interventions, though this remains highly speculative and controversial. The idea would be to introduce compounds or encourage processes that increase hydroxyl radical production or shield methane from loss mechanisms that currently remove it.

But these approaches face enormous obstacles. The atmosphere is vast. The interactions are complex. Unintended consequences could easily outweigh intended benefits. Most climate scientists prefer focusing on reducing emissions at the source rather than attempting to engineer the atmosphere.

That said, understanding the chemistry more deeply enables better prediction. Better prediction enables better policy. The research into hydroxyl radicals and methane destruction isn't purely academic—it informs how we assess the effectiveness of different climate policies and where we should focus effort.

Technology development also matters on the emissions side. Improved capture of methane from landfills, better livestock management practices that reduce digestive methane, more efficient agricultural techniques—these all reduce the source emissions that must then rely on hydroxyl radical destruction.

The Research Legacy: What We Learned From The Pandemic's Unintended Experiment

Historians of climate science might view the COVID-19 pandemic as a tragic but scientifically invaluable period. The sudden, global-scale shift in human activity created conditions that hadn't existed in recent history: a massive, coordinated reduction in multiple pollutants simultaneous, occurring worldwide over an extended period.

Normal climate science relies on models and observations from varying conditions. We observe how the atmosphere responds to El Niño events, to volcanic eruptions that inject particles into the stratosphere, to slow changes in carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. But we rarely get a sudden, global perturbation where multiple variables change simultaneously.

The pandemic provided exactly that. The data collected during 2020 to 2022 will inform atmospheric chemistry research for decades. It validated certain theoretical predictions while revealing surprises that models hadn't fully captured. It demonstrated that our atmosphere's response to human activity is more complex and interconnected than simplified linear models suggest.

Future research will continue teasing apart the mechanisms. New satellite instruments will provide better measurements. Better atmospheric models will be developed incorporating lessons from the pandemic period. Isotopic analysis techniques may improve, allowing even more precise attribution of methane sources.

But the fundamental insight—that cleaning the air has unintended consequences for atmospheric chemistry—is likely to endure. It's a reminder that Earth's atmosphere is a coupled system where you cannot change one element without affecting others.

Climate Policy Redesign: Integrating Air Quality and Greenhouse Gas Reduction

Traditionally, air quality agencies and climate policy makers operated somewhat independently. Air quality agencies focused on local and regional pollution affecting health. Climate agencies focused on global greenhouse gas concentrations affecting the entire planet.

The research suggests these domains need closer integration. Policies designed to reduce nitrogen oxides should explicitly account for how those reductions affect the atmosphere's methane-destroying capacity. Climate policies targeting methane reduction should consider how they interact with air quality improvements.

This could mean prioritizing certain types of emissions reductions over others. For example, reducing methane from agriculture and waste might be prioritized alongside reducing carbon dioxide from energy sectors, while allowing some nitrogen oxide emissions reductions to occur more gradually in ways that preserve hydroxyl radical production.

It doesn't mean abandoning air quality improvements—those remain essential for human health and remain a moral imperative. Rather, it means implementing those improvements thoughtfully, with awareness of their atmospheric chemistry effects.

Some regions might explore different transition pathways than others. A region with severe air quality problems might prioritize rapid nitrogen oxide reduction despite the methane implications. A region with already-clean air might focus first on methane reduction while gradually improving air quality. Flexibility and regional customization become more important when we recognize the interconnections.

The Bigger Picture: Interconnected Systems and Unintended Consequences

The methane story is emblematic of a broader principle in environmental science: Earth's natural systems are deeply interconnected, and interventions in one domain almost inevitably affect others. There are rarely purely beneficial actions. Instead, we navigate trade-offs, managing harms while pursuing benefits.

Similar stories emerge across environmental domains. Efforts to restore wetlands for water treatment and biodiversity can increase methane emissions. Wind farms provide clean energy but affect bird populations. Biofuel production reduces fossil fuel use but competes with food production. Every intervention cascades through multiple systems.

This doesn't counsel paralysis or resignation—the alternative to acting is accepting the status quo, which carries enormous costs. Rather, it counsels humility and systems thinking. Designing better policies means understanding these interconnections and managing them deliberately rather than stumbling into unintended consequences.

The pandemic research provides a case study in how this works in practice. A policy intervention (lockdowns, not deliberately designed for environmental reasons) produced environmental effects (reduced nitrogen oxides) that rippled through atmospheric chemistry in unexpected ways (reduced hydroxyl radical production) that had climate implications (increased methane lifetime and accumulation).

Understanding that cascade, reconstructing it from data, and articulating the mechanisms is precisely what science is supposed to do. The research succeeds in all three. What remains is whether we'll design our climate and environmental policies with appropriate awareness of these interconnections.

FAQ

What caused methane emissions to spike during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Methane emissions spiked during the pandemic due to two interconnected factors. First, reduced nitrogen oxide emissions from factories and vehicles weakened the atmosphere's natural methane destruction mechanism, allowing methane to persist longer. Second, La Niña conditions from 2020 to 2023 caused exceptional rainfall in tropical regions, flooding massive wetland areas in Africa and Southeast Asia where microbial methane production accelerated dramatically.

How do hydroxyl radicals destroy methane in the atmosphere?

Hydroxyl radicals are highly reactive molecules that encounter methane molecules and break their chemical bonds, converting methane into water vapor and carbon dioxide. This process occurs continuously throughout the troposphere, and hydroxyl radicals are replenished through a series of chemical reactions triggered by sunlight. Since hydroxyl radicals have lifespans of less than a second, the atmosphere requires constant replenishment to maintain its methane-destroying capacity.

Why does reducing pollution decrease the atmosphere's ability to destroy methane?

Reducing nitrogen oxide concentrations, while beneficial for air quality, slows the production of hydroxyl radicals. Nitrogen oxides act as catalysts in the chemical reactions that create hydroxyl radicals. When nitrogen oxide levels decline by 15 to 20 percent during lockdowns, the production of hydroxyl radicals decreased proportionally, reducing the atmosphere's capacity to destroy methane molecules. This creates a trade-off between improving air quality and maintaining the atmosphere's methane sink.

What is the clean air paradox mentioned in the research?

The clean air paradox describes a contradiction in climate policy: as we transition away from fossil fuels and improve air quality, nitrogen oxide concentrations will decline, which is positive for human health. However, this reduction simultaneously weakens the atmosphere's natural ability to destroy methane, a potent greenhouse gas. We face a situation where reducing one pollutant that harms air quality inadvertently makes climate change more difficult to manage.

How did scientists determine that the extra methane came from wetlands rather than oil and gas operations?

Scientists analyzed the isotopic composition of atmospheric methane using measurements from the global flask network operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Methane from fossil fuels contains more of the heavier carbon-13 isotope, while methane from biological sources contains more of the lighter carbon-12 isotope. The data showed that atmospheric methane became lighter during the surge period, indicating biological rather than fossil fuel sources.

What role did La Niña play in the methane surge?

La Niña, the cool phase of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, persisted for three consecutive Northern Hemisphere winters from 2020 to 2023, bringing exceptional rainfall to tropical regions. This flooding inundated massive wetland areas in Central Africa, South Sudan, and Southeast Asia, creating ideal conditions for methanogens—bacteria that produce methane as a metabolic byproduct. Researchers estimate that tropical African and Asian wetlands alone accounted for roughly 30 percent of the global methane emissions increase during this period.

Will cleaner air permanently reduce the atmosphere's ability to destroy methane?

The relationship between nitrogen oxides and hydroxyl radical production is complex. While eliminating fossil fuel combustion will reduce nitrogen oxide concentrations, other compounds associated with fossil fuel burning also suppress hydroxyl radical production. As multiple pollution sources decline, the net effect on hydroxyl radical levels may be different than the simple projection based on nitrogen oxides alone. Additionally, other factors like stratospheric ozone recovery could affect tropospheric chemistry in unpredicted ways.

What are the climate implications of longer methane lifetimes?

If methane persists in the atmosphere longer because fewer hydroxyl radicals are available to destroy it, the same reduction in emissions will produce smaller near-term climate benefits. Methane would accumulate more readily, creating a longer-lasting climate problem. This complicates climate policy design, as reducing methane emissions becomes more important to achieve equivalent climate goals if the methane stays around longer.

How do climate feedbacks threaten to amplify methane emissions further?

Warmth itself increases methane production from wetlands by accelerating microbial metabolism and increasing plant productivity in wetland ecosystems. If warming temperatures cause wetlands to expand or remain wet longer, methane emissions increase. More methane means more warming, which causes further wetland expansion—creating a positive feedback loop. This is particularly concerning for Arctic permafrost, where thawing could release vast quantities of methane currently sequestered in frozen ground.

What changes to climate policy does this research suggest are necessary?

The research suggests that air quality policy and climate policy need closer integration. Policies should account for how reducing nitrogen oxides affects the atmosphere's methane-destroying capacity. This might involve prioritizing methane reduction and transitioning away from fossil fuels while being more gradual about reducing all nitrogen oxide sources simultaneously. Additionally, managing natural methane emissions from wetlands and permafrost becomes increasingly important as human methane emissions decline.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic provided climate science with an unintended gift: a brief window into how the atmosphere responds when massive human activities suddenly pause. The results were surprising and humbling. While the data confirmed that human civilization's emissions are indeed driving atmospheric pollution, it also revealed unexpected complexities in how the atmosphere regulates itself.

That a reduction in air pollutants could somehow amplify a greenhouse gas seemed paradoxical until scientists traced the atmospheric chemistry pathways. It's not a paradox of nature but a paradox of policy: two legitimate environmental goals—cleaning the air and preventing climate change—can work at cross purposes when we don't understand their interconnections.

The story of hydroxyl radicals, wetland microbiology, and atmospheric chemistry is simultaneously reassuring and concerning. It's reassuring because it demonstrates that scientists can identify these mechanisms, measure them precisely, and explain them to others. The monitoring infrastructure and analytical tools available today would have been unthinkable a generation ago. Our ability to understand our atmosphere continues improving.

It's concerning because it illustrates how much remains uncertain. We're discovering that problems we thought were separate—air quality and climate—are actually coupled systems. We're realizing that natural emissions from ecosystems might eventually dominate over human emissions as we reduce the latter. We're confronting the possibility that managing climate change successfully isn't simply a matter of reducing carbon dioxide, but involves managing multiple interconnected problems simultaneously.

The path forward requires integrating knowledge across disciplines. Climate scientists need to engage with atmospheric chemists. Air quality researchers need to partner with ecologists studying wetlands. Policy makers need to listen to all of them and design solutions that account for these interconnections.

It requires accepting uncertainty while still acting decisively. The methane problem hasn't been solved. The atmosphere's chemistry hasn't been fully mapped. But waiting for perfect knowledge isn't an option when the climate is already changing and atmospheric composition is already shifting. We must act with the best understanding available today while remaining open to new findings that might require policy adjustments.

Most of all, it requires recognizing that Earth's atmosphere and biosphere form an integrated system where actions in one domain reverberate through others. The pandemic showed us that system in action. The research afterward demonstrated how to read that system's signals and understand its mechanisms. The challenge ahead is using that knowledge to design a sustainable future where we clean the air for human health, stabilize the climate for planetary stability, and manage natural systems with respect for their complexity and our incomplete understanding of them.

The cleaner skies of 2020 were real. The rising methane was also real. Both revealed truths about our world that we're still grappling with. How we respond to those truths will determine whether we can build genuinely sustainable systems or whether we'll continue navigating from one unintended consequence to another.

Key Takeaways

- Methane emissions surged 16.2 parts per billion in 2020—the highest spike since records began in the 1980s—despite dramatic improvements in air quality

- Hydroxyl radicals, the atmosphere's natural methane-destroying molecules, require nitrogen oxides to be continuously produced; reduced pollution weakened this mechanism

- Approximately 80% of the 2020 methane surge came from the weakened atmospheric sink rather than increased emissions

- Isotopic analysis revealed the remaining 20% of the surge and ongoing increases through 2022 originated from microbial methane in tropical wetlands, not fossil fuel leaks

- La Niña conditions from 2020-2023 caused exceptional rainfall that flooded African and Asian wetlands, creating ideal conditions for methane-producing microbes

- The 'clean air paradox' reveals a fundamental tension: reducing nitrogen oxide pollution that harms human health simultaneously reduces atmospheric methane destruction capacity

- Climate feedbacks could amplify natural methane emissions as warming temperatures increase wetland productivity and Arctic permafrost thaw

Related Articles

- AI Data Centers Drive Historic Gas Power Surge [2025]

- Ocean Heat Records Shatter Again: What 2025's Climate Data Reveals [2025]

- 2026 Winter Olympics Environmental Impact: Snowpack Loss and Climate Crisis [2025]

- Data Centers & The Natural Gas Boom: AI's Hidden Energy Crisis [2025]

- Doomsday Clock at 85 Seconds to Midnight: What It Means [2025]

- Obvious Ventures Fund Five: The $360M Bet on Planetary Impact [2026]

![COVID-19 Cleared Skies but Supercharged Methane: The Atmospheric Paradox [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/covid-19-cleared-skies-but-supercharged-methane-the-atmosphe/image-1-1770413784144.jpg)