License Plate Readers & Privacy: What the Norfolk Flock Ruling Actually Changes

It was supposed to be a test case. Two Virginia residents, represented by a libertarian civil liberties nonprofit, challenged Norfolk's network of nearly 200 automated license plate reader cameras. They called it a "dragnet." They said their movements were being tracked without their knowledge or consent. They had a federal bench trial scheduled. And then, days before opening arguments, a federal judge dismissed the entire case in a 51-page ruling that essentially declared Norfolk's surveillance network constitutional, as reported by 13News Now.

The decision stung. But it also revealed something important about how American privacy law has lagged behind technology.

This isn't just about Norfolk. It's not even really about Flock Safety, the Atlanta-based company that built the system. It's about a fundamental gap in constitutional law: courts are still evaluating mass surveillance through a framework designed for single, targeted surveillance. A framework from 1983. Before smartphones. Before the internet. Before AI could identify a vehicle's make, model, color, and accessories in real time, then correlate that data with your home address, workplace, and everywhere you've been for the past three months.

Judge Mark S. Davis's ruling in Schmidt v. City of Norfolk created a straightforward precedent: if a city's ALPR system doesn't track the "whole of a person's movements," it passes constitutional muster. In other words, dragnet surveillance is legal as long as the net isn't quite dragnet-sized. It's a threshold question that will reverberate through every jurisdiction considering ALPR deployment, as noted by Courthouse News.

What makes this moment crucial is that we're at an inflection point. Flock has transformed from a niche law enforcement tool into one of the largest surveillance networks in America. Cities like Santa Cruz and Charlottesville have started backing away. Senators have raised alarm bells. But the Norfolk ruling just handed the company and thousands of police departments a legal green light to expand.

Let's break down what happened, why it matters, and what it actually means for privacy in America.

Understanding Automated License Plate Readers: The Technology

Ten years ago, ALPR technology was straightforward. A camera would snap a photo, optical character recognition software would read the plate, and the system would store the number. It was useful for finding stolen cars or vehicles with outstanding warrants. It was blunt. It was limited.

Flock Safety transformed that entire game.

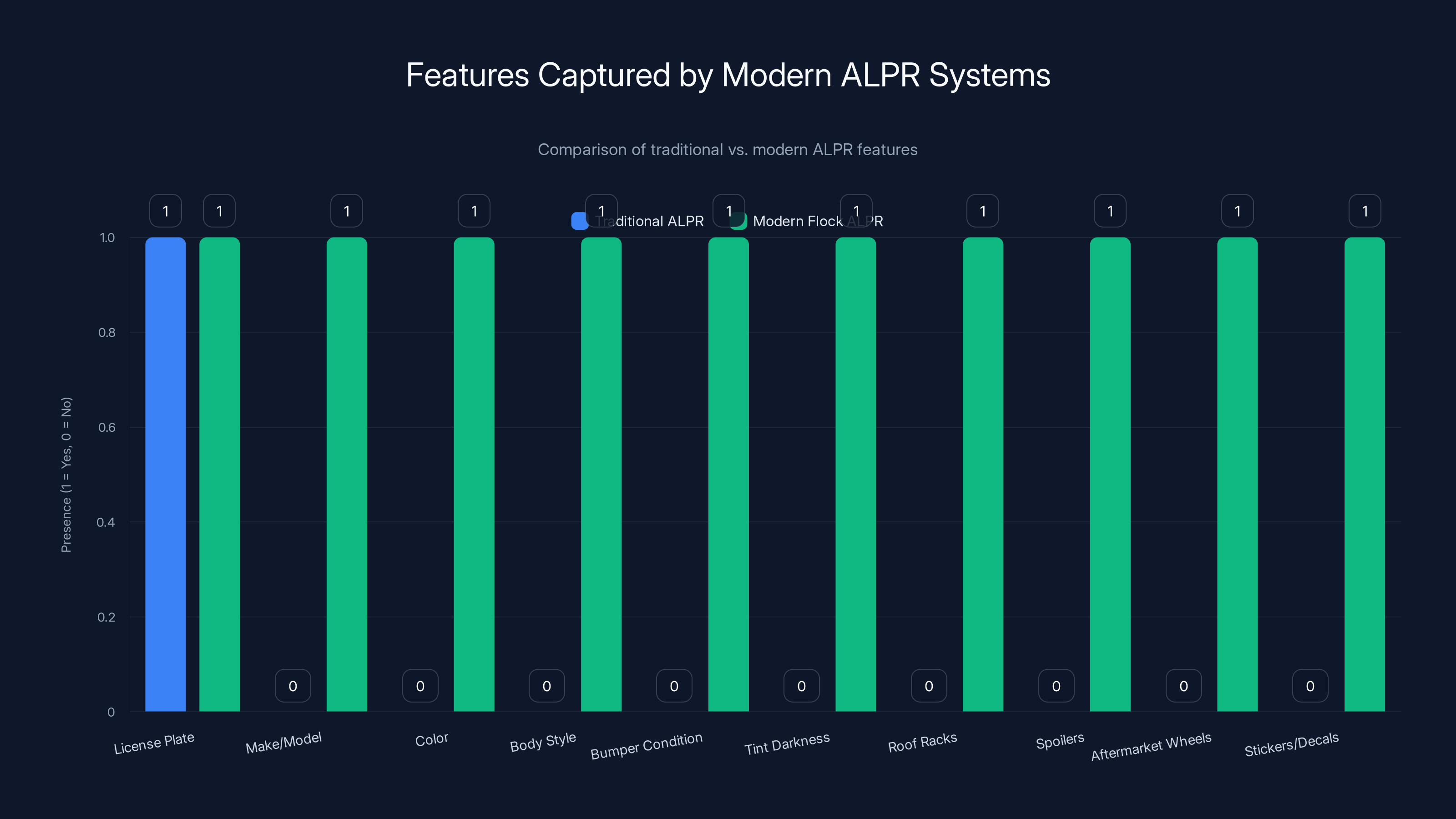

Modern Flock cameras don't just capture the license plate number. They capture the vehicle's make, model, color, body style, bumper condition, tint darkness, roof racks, spoilers, aftermarket wheels, and any visible stickers or decals. They tag whether the car has a ski rack, a bike rack, a tow hitch, or custom paint. Some cameras even capture whether someone is driving in the left or right lane.

Then comes the AI layer. Users can search this database with natural language queries. "Show me all silver Hondas with bike racks from the last 30 days." "Find every truck that passed through this intersection at 2 AM." The system doesn't just retrieve data; it synthesizes patterns. Over time, it learns where you live, where you work, where you worship, where you seek medical treatment, which therapist you see, which bars you frequent.

Flock's cameras capture not hundreds of data points per vehicle. They capture thousands. And because Flock operates as a cloud platform, the company itself has access to this data. So does every police department that subscribes. The system stores metadata for weeks or months, depending on jurisdiction settings. Some police departments have set retention to 120 days. Others keep the data indefinitely.

The scale is staggering. Flock claims over 10,000 customers, including law enforcement agencies, private companies, and municipalities. That means the network covers not just Norfolk, but hundreds of cities across America. Some jurisdictions have 50 cameras. Others have over 200. When you drive through Los Angeles, Denver, Houston, Atlanta, Charlotte, or Phoenix, there's a reasonable chance a Flock camera captured your vehicle. That image, metadata, and location data are now stored in a corporate database.

The technology isn't inherently malicious. Police can find stolen vehicles faster. They can track hit-and-run suspects. They can locate missing children. But the same tool that finds a kidnapper can also track a political activist, a woman leaving a domestic violence shelter, a person attending religious services, or a journalist meeting a source.

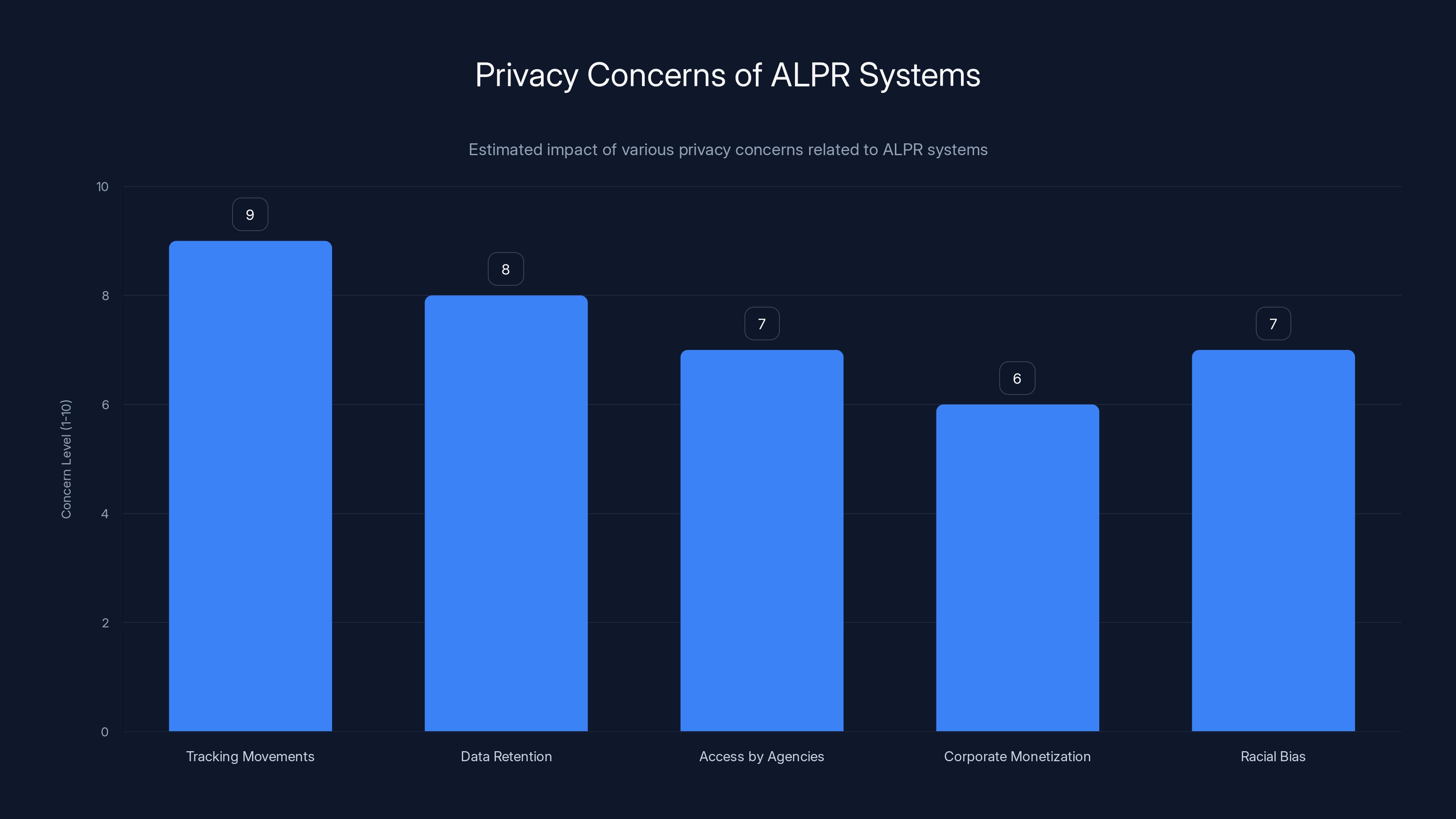

Tracking movements and data retention are the top privacy concerns associated with ALPR systems. Estimated data based on common privacy issues.

The Schmidt v. City of Norfolk Case: What Happened

In October 2024, two Virginia residents filed a lawsuit in federal court. Their names are on court documents as plaintiffs, but they've largely remained out of the public spotlight. What mattered was their legal argument: Norfolk's ALPR network violated their Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable searches.

They were represented by attorneys from the Institute for Justice, a libertarian nonprofit that specializes in civil liberties litigation. The legal strategy was elegant. They didn't argue that ALPR technology is inherently unconstitutional. Instead, they focused on scale and scope. They argued that Norfolk's network, with nearly 200 cameras creating a comprehensive tracking system, had crossed the line from surveillance into mass surveillance.

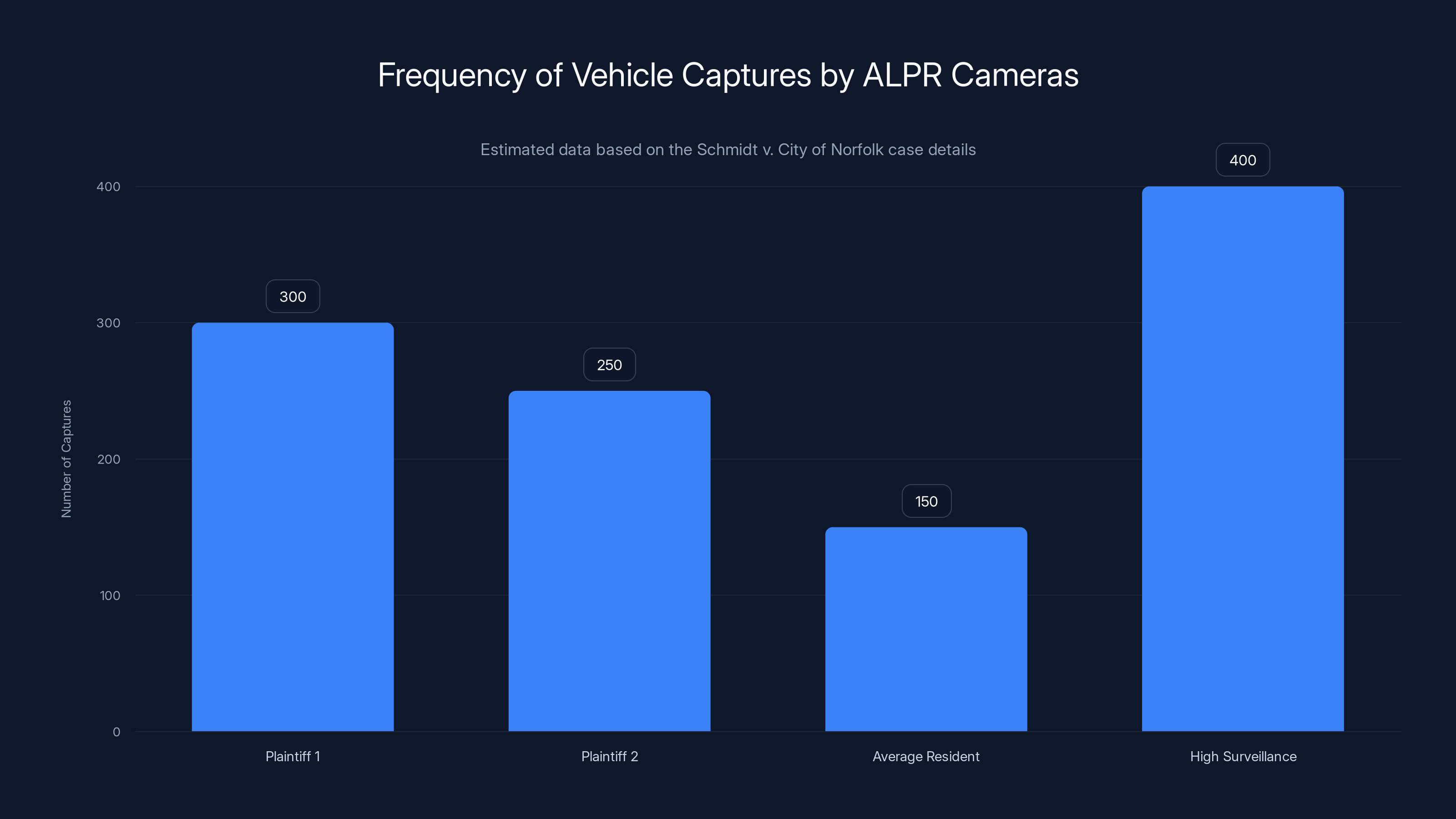

The plaintiffs submitted evidence showing that Flock cameras had captured their vehicles hundreds of times. One plaintiff's car was captured over 300 times. The cameras tracked them as they drove to work, to home, to medical appointments, to religious services, and to social events. The plaintiffs argued this created what they called a comprehensive "mosaic" of their movements, and that this mosaic violated their constitutional rights.

They had a reasonable legal theory. The U. S. Supreme Court had signaled concern about mass surveillance in a 2012 case called United States v. Jones, which involved GPS tracking. Justice Antonin Scalia wrote that even if individual surveillance might be legal, the "totality" of tracking could become unconstitutional. Justice Samuel Alito wrote separately that technology enabling "comprehensive, detailed, real-time tracking" might require a warrant even for public movements.

The plaintiffs thought they had momentum. The trial was set for January 2025. The Institute for Justice prepared their opening arguments.

Then, on January 7, 2025, Judge Mark S. Davis issued a ruling dismissing the case entirely. He granted Norfolk's motion for summary judgment, meaning the judge decided the law was so clearly in Norfolk's favor that no trial was necessary, as detailed by Ars Technica.

The plaintiffs lost without their evidence ever being heard.

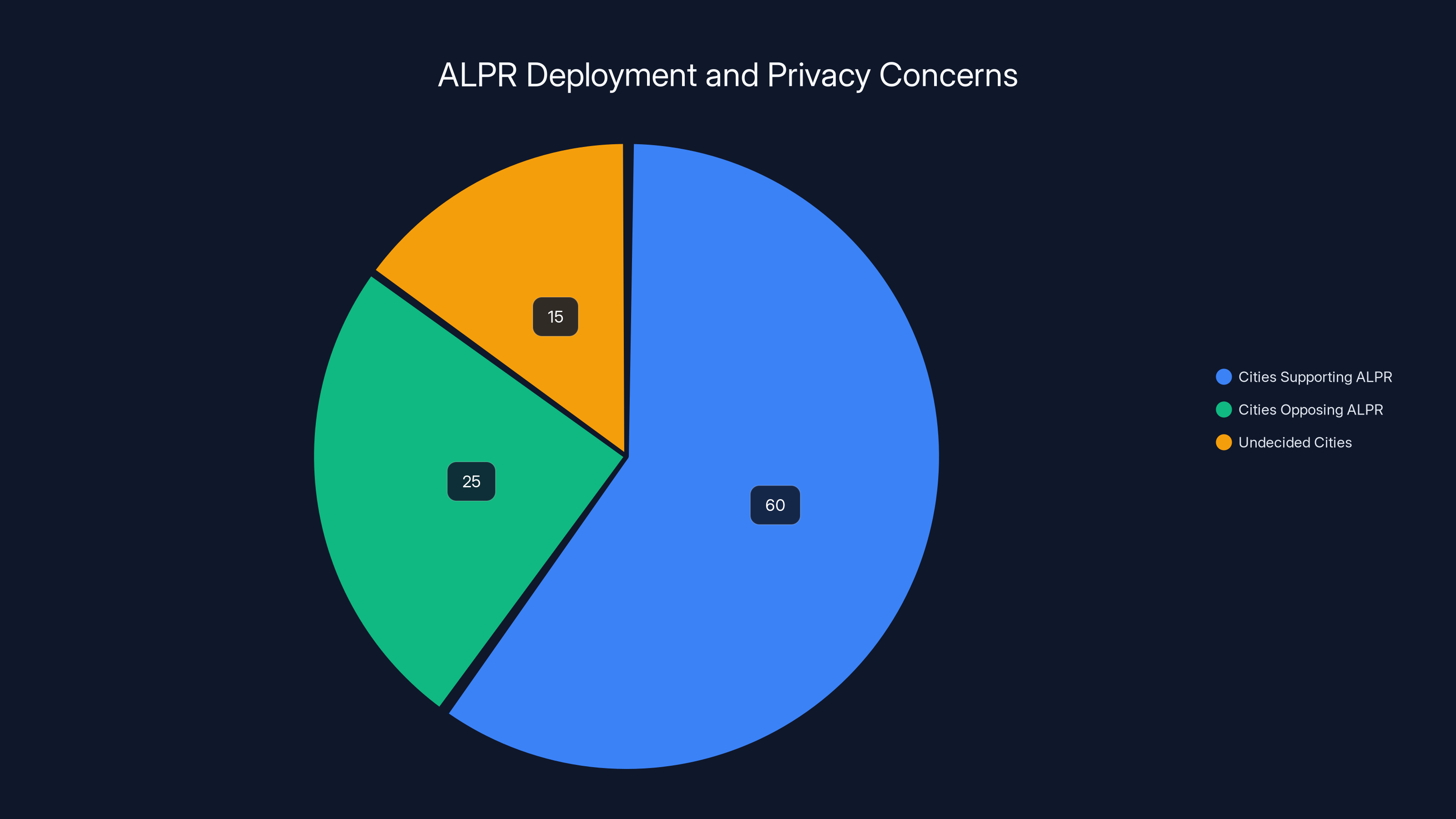

Estimated data shows that while a majority of cities support ALPR systems, a significant portion are either opposing or undecided, reflecting ongoing privacy concerns.

Judge Davis's Reasoning: The "Whole of Movements" Standard

Judge Davis acknowledged that ALPR technology is powerful. He wrote that "modern-day license plate reader systems, like Norfolk's, are nothing like [the technology of the early 1980s]." He recognized that the system creates detailed records of vehicles' movements. He even seemed sympathetic to privacy concerns.

But then he established a threshold: the system is constitutional as long as it doesn't track "the whole of a person's movements."

That phrase is doing a lot of work. What does "whole" mean? If the system captures 80 percent of your movements, is that constitutional? 90 percent? The judge didn't clarify. He just said that Norfolk's system, in his judgment, didn't meet the threshold. The plaintiffs hadn't demonstrated that they were comprehensively tracked.

This reasoning rests on a 1983 Supreme Court case called Knotts v. United States. In Knotts, the government placed a beeper (a radio transmitter) on a vehicle and tracked it across state lines. The Supreme Court ruled that the defendant had no reasonable expectation of privacy on public roads. Once you're on a public street, the Court reasoned, anyone can see your car. Therefore, the government tracking your car on a public street isn't a search requiring a warrant.

That logic made sense in 1983. If an officer follows your car, you can see them. You have notice. You can take evasive action. It's transparent.

But Judge Davis extended Knotts to automated, persistent, comprehensive surveillance conducted by AI systems operated by a private company and accessible to dozens of law enforcement agencies. The reasoning is where the legal theory breaks down, as highlighted by EFF's investigations.

The Privacy Implications: Why Legal Scholars Are Alarmed

Andrew Ferguson, a law professor at George Washington University and author of "Your Data Will Be Used Against You," called Judge Davis's ruling "understandably conservative and dangerous." Ferguson's concern is profound: the same logic that permits Norfolk's ALPR network could justify ALPR cameras on every street corner.

Think about the implications. An ALPR camera outside a religious institution reveals which faith people practice. Cameras outside medical clinics reveal health conditions. Cameras outside addiction treatment centers, psychiatrists' offices, Planned Parenthood clinics, or civil rights organizations reveal sensitive information about who frequents these places.

An ALPR camera outside a gun range reveals who owns firearms. Cameras outside abortion clinics reveal who seeks reproductive health services. Cameras outside political party headquarters reveal voting preferences or activism. Cameras outside protest sites reveal who exercises First Amendment rights.

Ferguson's point isn't theoretical. Police already use location data to profile suspects. Location history has become a key investigative tool. Dragnet ALPR data amplifies that capability exponentially. When the police want to investigate a crime, they can now search the ALPR database for every vehicle in a geographic area during a time window, then pull additional data on those vehicles from other sources. They can identify patterns. They can create networks of association.

The difference between justified surveillance and unjustified surveillance has traditionally been specificity. Police need specific information to target specific suspects. Mass surveillance eliminates that requirement. It enables fishing expeditions. It inverts the burden: instead of police identifying a suspect and surveilling them, the system surveils everyone and lets police sort through the haystack.

Judge Davis's ruling didn't address any of this. He evaluated the technology in isolation, not as a system. He looked at whether the ALPR network tracked the plaintiffs' entire lives, not whether it tracked enough to be concerning. He applied a 1983 legal standard to 2025 technology.

That's the dangerous part.

Modern ALPR systems, like those from Flock, capture a wide array of vehicle features beyond just the license plate, enhancing data richness and utility. Estimated data based on described capabilities.

Flock's Response: Framing the Ruling

Flock Safety celebrated the ruling immediately. The company issued a statement emphasizing that the court found its system "meaningfully different from systems that enable persistent, comprehensive tracking." Flock argued that when "used with appropriate limitations and safeguards, LPRs do not provide an intimate portrait of a person's life."

That characterization is worth examining closely. What are these "appropriate limitations and safeguards"? Flock didn't specify. Different jurisdictions have different policies. Some police departments minimize the retention period. Others keep data for months. Some departments have policies restricting searches to specific investigations. Others allow officers to search for any reason.

Flock's business model depends on police departments using the system broadly. The more searches, the more value the technology delivers, the more likely departments are to renew contracts. If Flock wanted to enforce strict limitations, the company would restrict customer access through software. Instead, Flock relies on customer policies, which vary wildly.

The company also emphasized the ruling's language about "appropriate safeguards." But the ruling didn't define what makes safeguards appropriate. It just assumed they exist. Judge Davis didn't examine Norfolk's actual policies. He didn't investigate how officers actually use the system. He didn't require Norfolk to implement any specific safeguards.

What Judge Davis did was declare that Flock's technology, as used by Norfolk, doesn't violate the Constitution. That's different from saying it's appropriate or that it properly balances public safety with privacy. Constitutional law sets the floor. It's the minimum standard. Many things are constitutional but still terrible policy, as discussed in WFLX.

Flock knows this distinction. The ruling allows the company to tell potential customers: "We're legally validated. You can deploy ALPR networks with confidence." That's powerful marketing in an industry where legal risk is a real concern.

The Supreme Court Precedent Problem: Knotts v. United States

The legal foundation of Judge Davis's ruling is Knotts v. United States, a 1983 Supreme Court case. Understanding why Knotts is a bad fit for modern ALPR technology is crucial to understanding why this ruling troubles legal scholars.

In Knotts, the government suspected a man of manufacturing methamphetamine. They placed a beeper (a radio transmitter) on a barrel of chemicals he purchased and tracked it to a secluded cabin in Minnesota. The Supreme Court ruled that placing the beeper didn't constitute a search under the Fourth Amendment because the defendant had no reasonable expectation of privacy while driving on public roads.

Chief Justice Warren Burger wrote for the majority: "A person traveling in an automobile on public thoroughfares has no reasonable expectation of privacy in his movements from one place to another." The reasoning was straightforward. Public spaces are public. The government can see what happens in public. Therefore, the government can track you in public.

But Knotts has been heavily criticized by modern courts and scholars. Justice Alito, in the 2012 GPS case (United States v. Jones), noted that Knotts predates the digital age. He wrote that while a single trip on a public road might not implicate privacy, the aggregate of all trips over time reveals intimate details about a person's life.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor went further in a concurring opinion in Jones. She argued that the traditional "reasonable expectation of privacy" test no longer works in an age of ubiquitous surveillance technology. She suggested that courts need a new framework entirely.

But Judge Davis didn't adopt any new framework. He just applied Knotts. He reasoned that because the plaintiffs were driving on public roads, they had no reasonable expectation of privacy in their vehicle movements. Therefore, the government can collect and store data about those movements. Therefore, the system is constitutional.

The problem is obvious: this logic extends infinitely. It would permit cameras on every block, tracking every car, retained forever. It would permit real-time location tracking of everyone in a city. It would permit the government to build a complete map of everyone's movements, beliefs, associations, and behaviors.

Judge Davis tried to draw a line by saying the system must not track "the whole of a person's movements." But that's exactly what ALPR networks do, especially as they expand. With enough cameras in enough locations, the system does track most of a person's movements. The judge's line is arbitrary and will collapse as the network expands.

The chart illustrates the frequency of vehicle captures by ALPR cameras, highlighting the extensive tracking of the plaintiffs compared to an average resident. Estimated data based on case details.

The Institute for Justice's Appeal: What's Next

The Institute for Justice immediately announced it would appeal. The organization has a track record of taking Second Amendment and property rights cases to the Supreme Court, so it has experience with high-stakes appellate litigation.

The appeal will likely focus on several arguments. First, the appellate court might reconsider whether the Knotts framework is appropriate for modern surveillance technology. Second, they'll argue that the aggregate of tracked movements reveals intimate information, even if no single movement is sensitive. Third, they'll emphasize that the system is automated, permanent, and accessible to multiple agencies, not a single officer conducting traditional surveillance.

There's also a potential Supreme Court angle. The Court has shown renewed interest in privacy and Fourth Amendment issues. Justice John Roberts has expressed concern about surveillance technology. The Court might be willing to revisit Knotts in light of technological change.

But appeals take time. The Norfolk ruling stands for now. And every police department in the country is watching. Cities that were on the fence about Flock deployment will likely move forward. Cities considering scaling up their ALPR networks will accelerate those plans.

Jurisdictional Divergence: Who's Pulling the Plug on Flock

While Norfolk's ALPR network survives legal challenge, other cities are moving in the opposite direction. Santa Cruz, California ended its Flock contract in 2023, citing privacy concerns. Charlottesville, Virginia, a city that shares Virginia's federal court jurisdiction with Norfolk, ended its Flock agreement in 2024. Both cities' city councils voted to terminate contracts after public pressure, as reported by Courier Press.

The pattern is interesting. These aren't rural conservative areas resistant to law enforcement technology. Santa Cruz is progressive, tech-forward, and home to tech workers who understand surveillance. Charlottesville is home to the University of Virginia. Both cities' councils included members who understood the privacy implications of ALPR networks.

Santa Cruz's city council noted that while the technology might be legal, it wasn't appropriate for their community's values. They cited concerns about immigration enforcement and racial bias in policing. Some officers, they noted, might use ALPR data to target immigrant communities or communities of color.

California has also moved to restrict ALPR deployment statewide. The state legislature passed AB 375, which created privacy protections and restricted police use of ALPR data. Officers can't search ALPR databases for investigative purposes without reasonable suspicion that a specific vehicle was involved in a specific crime. It's a threshold approach: you need a suspect and a crime before you search the ALPR database, as detailed by The Seattle Times.

Other states are watching. Massachusetts, Maryland, and New Hampshire have introduced ALPR restriction legislation. Vermont banned the technology outright for state police. The debate at the state level is heating up precisely because federal courts are refusing to strike down ALPR systems.

This creates an interesting dynamic. If federal constitutional law permits ALPR systems, then restrictions must come from state law, local ordinance, or corporate policy. That means the battlefield has shifted. It's no longer about whether ALPR is constitutional. It's about whether legislatures will restrict it anyway.

Flock is betting that legislatures won't. The company argues that ALPR technology helps law enforcement do their jobs. Police departments argue that they use ALPR data to recover stolen vehicles, find missing people, and apprehend suspects. These are valuable capabilities. Restricting ALPR means surrendering those capabilities.

But each restriction or jurisdictional opt-out represents a judgment that privacy concerns outweigh law enforcement benefits. Santa Cruz made that judgment. Charlottesville made that judgment. These aren't niche communities. They're legitimate policy decisions that ALPR networks aren't worth the privacy cost.

Santa Cruz and Charlottesville have terminated their Flock contracts due to privacy concerns, with Norfolk potentially following. Estimated data.

Immigration Enforcement and Federal Access: The Real Concern

One major concern that hasn't received adequate attention in the Norfolk ruling is federal immigration enforcement. Flock Safety has contracts with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), according to reporting by privacy advocacy groups. This means that federal immigration agents can access ALPR data from police department networks.

For many jurisdictions, this is a dealbreaker. City councils have made policy decisions that their resources won't be used for federal immigration enforcement. They've passed resolutions saying local police won't cooperate with ICE absent a judicial warrant. They've limited information sharing with federal agencies.

But if ICE can directly access police department ALPR data through Flock's platform, those policy decisions become meaningless. ICE agents can search the ALPR database directly, identifying vehicles and locations associated with immigration targets. They can use ALPR data to track individuals, build cases, and execute raids.

For immigrant communities, ALPR networks become a surveillance apparatus targeting their every movement. An undocumented immigrant driving to work, to a religious service, to a medical appointment, or to visit family is captured in the ALPR database. That data is accessible to ICE. The system enables comprehensive tracking of vulnerable populations.

Judge Davis's ruling doesn't address this concern at all. The ruling treats ALPR as a local law enforcement tool, evaluated in isolation. It ignores the reality that ALPR data flows across jurisdictional boundaries and reaches federal agencies with different enforcement priorities, as noted by Fox 13 Seattle.

Several senators have raised this concern publicly. In a 2024 letter to Flock Safety, senators expressed grave concerns about ALPR data reaching immigration enforcement agencies. They urged the company to implement technical measures preventing federal agency access. Flock responded by saying it would work with police departments to develop appropriate policies.

But policies aren't technical barriers. ICE can still demand access. Police departments can still comply. And Judge Davis's ruling now provides legal cover for those decisions. If ALPR systems are constitutional, then there's no legal impediment to federal immigration agencies using ALPR data.

The Mosaic Theory and Aggregated Privacy: Why Courts Are Split

One of the most important concepts in modern surveillance law is the "mosaic theory." The idea, articulated most clearly by Justice Alito in the 2012 Jones case, is that while a single data point might not be sensitive, the aggregate of many data points creates a detailed portrait of a person's life.

One location visit is innocuous. But a pattern of visits to specific locations reveals religion (visits to religious institutions), medical conditions (visits to health clinics), political beliefs (visits to party headquarters), lifestyle choices (bars, restaurants, entertainment venues), and associations (recurring meetings with specific people).

The "mosaic" is the problem. The FBI tracking you to a single meeting isn't necessarily problematic. The FBI tracking you to dozens of meetings over months reveals intimate information. That aggregate surveillance might reveal more than a wiretap or a search warrant ever could.

The Norfolk case presented a classic mosaic scenario. The plaintiffs were tracked hundreds of times. Their locations over months were visible in the ALPR database. A reasonable person could infer lifestyle patterns, associations, and beliefs from that data.

But Judge Davis rejected the mosaic theory in his ruling. He wrote that the plaintiffs must show comprehensive tracking of "the whole of a person's movements," but he didn't quantify that. The plaintiffs had been tracked 300+ times over several months. Was that "the whole" of their movements? Not if they drove 1,000 times during that period. Not if they took highway routes not covered by ALPR cameras.

Other courts have adopted stronger mosaic protections. Some federal courts have ruled that police need warrants for extended location tracking. California's Supreme Court ruled that police need warrants to access cell phone location data. These courts recognized that aggregate surveillance is qualitatively different from isolated surveillance.

But Judge Davis went the other direction. He required the plaintiffs to prove comprehensive tracking, which is nearly impossible because ALPR networks don't cover 100 percent of routes. The plaintiffs lose by default because no surveillance system tracks every single movement.

This threshold creates a perverse incentive. Police departments will carefully deploy ALPR networks to cover most routes but intentionally leave gaps, preserving the legal fiction that the system doesn't track "the whole" of movements. The system will capture 85 or 90 percent of movements while remaining legally insulated from mosaic theory critiques.

Ferguson notes that this is backwards. Privacy protections should strengthen as surveillance becomes more comprehensive, not weaken. The Knotts-based framework does the opposite. It creates a legal regime where comprehensive surveillance is more constitutional than limited surveillance because limited surveillance might actually track "the whole of movements" for a specific location, while comprehensive surveillance merely tracks most movements across the city.

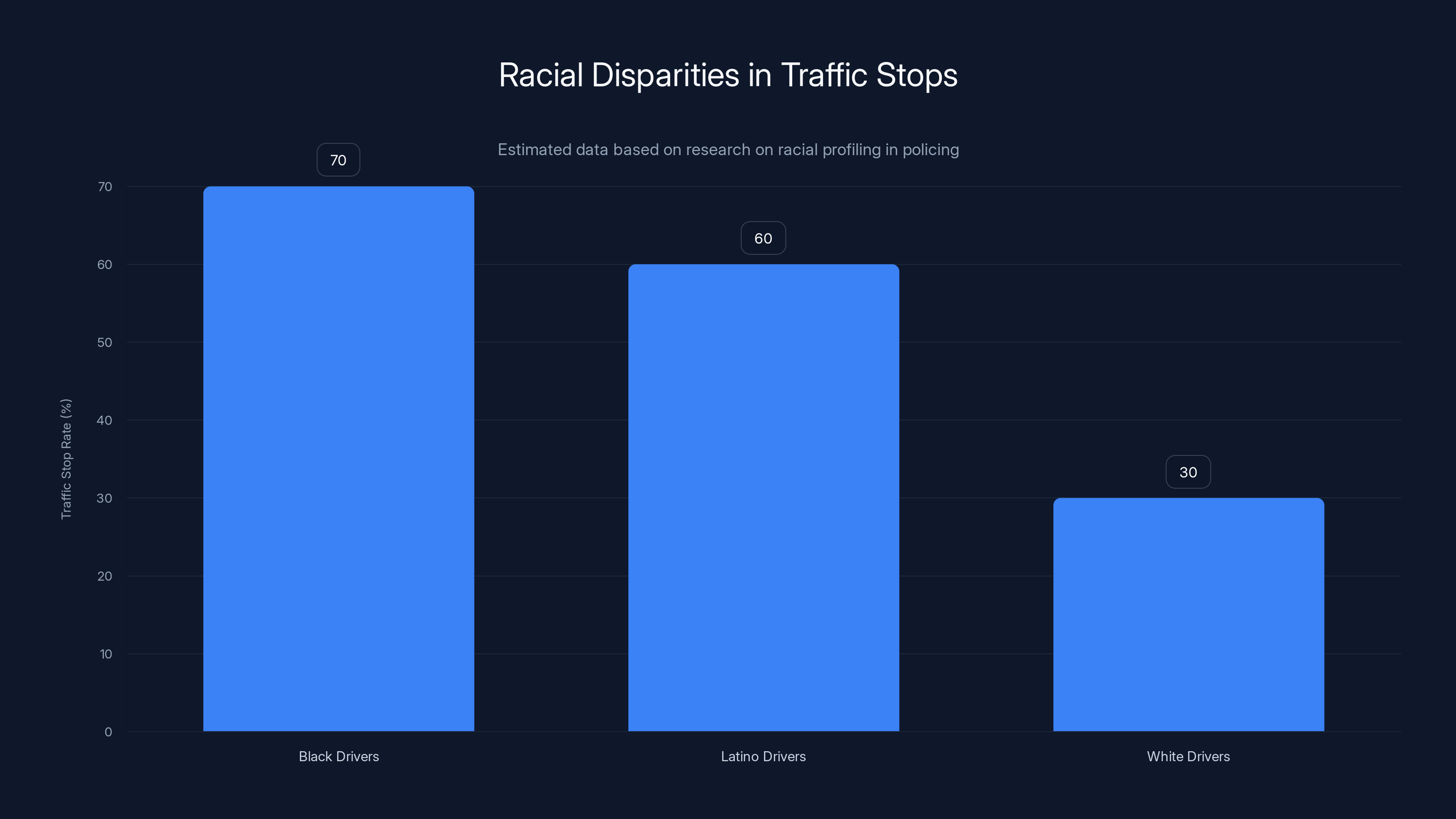

Estimated data suggests Black and Latino drivers are stopped at higher rates than White drivers, highlighting disparities in policing practices.

Racial Justice and Policing Disparities: The Equity Question

Another concern largely absent from Judge Davis's ruling is racial justice. ALPR technology doesn't discriminate at the camera level. The equipment captures all vehicles equally. But law enforcement's use of ALPR data reflects broader patterns of racial disparities in policing.

Research shows that police stop Black and Latino drivers at higher rates than white drivers for the same traffic violations. This bias happens at the point of police discretion. An officer encounters a vehicle, decides whether to initiate a stop, and that decision is influenced by racial stereotypes or demographic associations.

ALPR technology amplifies this pattern. Police can now search the ALPR database for "any truck in this neighborhood on this date" without a specific crime. They can then conduct traffic stops based on ALPR hits, allowing officers to exercise discretion about which hits warrant investigation.

Or worse, police can use ALPR data retrospectively. A crime occurs. Police search the ALPR database for all vehicles in the area. Then officers may approach drivers not based on eyewitness identification or specific evidence, but on algorithmic flagging. If the algorithm learns that crime correlates with certain neighborhoods, and those neighborhoods have particular demographic characteristics, then the algorithm becomes a proxy for racial profiling.

Flock Safety's AI features amplify this risk. The system can now search with natural language queries like "all pickup trucks, possibly with damage." The system learns patterns. Over time, it might become biased toward flagging vehicles associated with specific neighborhoods or demographic groups.

Nor does the system provide transparency. When an officer searches the ALPR database and receives results, the officer has no visibility into why those results appeared. Are they ranked by relevance? By recency? By algorithmic confidence? Is the algorithm considering the officer's previous searches and tailoring results accordingly?

Flock doesn't publicly disclose its algorithm. The company treats the AI system as a trade secret. That means police departments can't audit the system for bias. Defendants can't challenge the algorithm in court. The public has no idea how ALPR data is being processed or whether bias is embedded in the system.

Judge Davis's ruling doesn't address any of this. The court evaluated ALPR technology in the abstract, not in the context of actual police deployment and discretionary enforcement. The court didn't examine arrest data, stop data, or traffic citations to determine whether ALPR's expansion correlates with disparities in enforcement.

That's a major gap in the legal analysis. Privacy isn't the only concern with ALPR networks. Equity and fairness are equally important.

Data Security and Corporate Access: Who Owns Your Location Data

Here's something many people don't realize: when police deploy Flock cameras, Flock Safety itself has access to the data. The company operates the cloud infrastructure. The company handles backups, maintenance, and system administration. The company can see which vehicles are captured, where they're captured, and when.

Flock says it doesn't use ALPR data for other purposes. The company says it follows strict data governance policies. But the company is a venture-backed startup worth $7.5 billion with pressure to grow revenue. If the company could monetize ALPR data, why wouldn't it?

Insurance companies might pay for ALPR data showing which drivers frequent accident-prone areas. Marketing companies might pay to understand driver patterns and behaviors. Data brokers might acquire ALPR data to build comprehensive location profiles. The monetization possibilities are endless.

Flock claims it won't do any of this. But trusting a corporation not to monetize valuable data requires extraordinary faith in corporate ethics. History suggests otherwise. Every major tech company has faced criticism for monetizing user data in ways users didn't expect or approve.

Moreover, Flock is a venture-backed startup, which means it has fiduciary duties to investors to maximize return. If the company could generate additional revenue from ALPR data, executives might face shareholder pressure to do so. The company could argue that it's improving shareholder value while maintaining privacy by using anonymized data.

Except anonymization is mostly a myth. Location data is inherently identifying. Researchers have repeatedly demonstrated that they can re-identify individuals from supposedly anonymized location datasets. When you know that a person travels from home to work to specific locations, you can identify them even without a name attached.

Flock's entire data infrastructure should be subject to strict regulatory oversight. The company should be prohibited from accessing ALPR data without specific authorization from individual officers for specific investigations. The company should be required to implement technical controls preventing unauthorized access. The company should face substantial penalties for any unauthorized disclosure or misuse of ALPR data.

But Judge Davis's ruling doesn't impose any of these requirements. The ruling treats Flock as a neutral technology vendor. It doesn't address the corporate incentives driving data collection and retention. It doesn't grapple with the reality that ALPR creates a massive database of location information that represents enormous commercial value.

What Happens Now: Implementation and Expansion

With the Norfolk ruling providing legal validation, expect accelerated ALPR deployment. Cities that were hesitant will move forward. Police departments that were debating expansion will expand. Flock will use this ruling in sales pitches. The company will argue that federal courts have approved ALPR technology. The legal risk has diminished.

Norfolk itself will likely expand its ALPR network. With 200 cameras already deployed, the city might push toward 250 or 300 cameras, extending coverage to more neighborhoods. Each new camera increases the system's comprehensiveness.

Other Virginia jurisdictions will take note. Virginia is home to several mid-sized cities where Flock deployment could expand rapidly. Alexandria, Richmond, and Virginia Beach are natural candidates for expanded ALPR networks.

The ruling also encourages police unions to advocate for ALPR expansion. Cops want tools that help them do their jobs. ALPR systems help solve crimes and locate missing people. Police will cite the ruling in municipal budget requests, arguing for expanded surveillance capability.

But the ruling also provokes political opposition. As ALPR networks expand, privacy advocates will organize opposition campaigns. City councils will face constituent pressure. Some cities will follow Santa Cruz and Charlottesville's path and end their contracts.

The result will be geographic fragmentation. Some jurisdictions will have comprehensive ALPR networks. Others will ban or severely restrict the technology. People will naturally gravitate toward privacy-protective jurisdictions if they value anonymity. This creates an interesting dynamic where ALPR networks might actually push people away from some cities.

Legislation as the New Battleground: State-Level Restrictions

With federal constitutional law permitting ALPR systems, the battle will shift to state legislatures. Expect significant legislation over the next 2-3 years addressing ALPR deployment and use restrictions.

States will probably follow California's model or create variations. Many states will require reasonable suspicion before officers can search ALPR databases. Some states will implement data retention limits. Others will restrict federal agency access. A few will ban the technology entirely.

Flock will lobby heavily against restrictive legislation. The company will testify before legislatures, arguing that ALPR technology helps law enforcement. The company will provide case studies of crimes solved using ALPR data. Police unions will reinforce the message.

Advocates will counter with privacy and equity arguments. They'll highlight cases where ALPR data was misused or where the technology enabled discriminatory enforcement. They'll present research on bias in policing and how ALPR amplifies those biases.

The legislative outcomes will vary by state. California and Massachusetts will likely adopt restrictive frameworks. Texas and Florida might adopt permissive frameworks. States in the middle will develop compromise approaches.

This fragmentation creates compliance challenges for Flock. The company will need different systems for different states. Some jurisdictions might allow broad ALPR searches while neighboring jurisdictions require warrants. Flock will need to enforce these different rules through software controls.

Eventually, this might create pressure for federal legislation. If states develop wildly divergent ALPR rules, law enforcement might push for federal preemption. The result could be a federal ALPR regulatory framework, similar to how federal wiretapping laws preempted state legislation.

But that's years away. For now, expect state legislative activity focused on ALPR restrictions.

The Broader Privacy Crisis: ALPR Is Just One Piece

The Norfolk ruling matters not just for ALPR specifically, but for privacy law generally. The ruling exemplifies a broader problem: American courts haven't adequately updated privacy law for the digital age.

Courts are still operating under frameworks designed for physical intrusions. Trespass law, for instance, requires physical entry onto someone's property. But digital surveillance doesn't require trespass. It operates remotely through networks and sensors.

Courts are still applying reasonable expectation of privacy tests designed for 20th century technology. The Fourth Amendment asks whether someone had a reasonable expectation of privacy. In a car on a public road, the answer seems intuitive: no. But in a world where cars are tracked through ALPR networks, in a world where phone location data reveals home addresses and intimate locations, in a world where email surveillance and internet monitoring are routine, the answer becomes complicated.

The solution isn't fixing ALPR law. It's reconceptualizing privacy law. Courts need frameworks that address aggregate surveillance, algorithmic decision-making, corporate data collection, and persistent tracking. They need to understand that privacy isn't just about secrecy; it's about autonomy and freedom from surveillance.

Some legal scholars have proposed alternative frameworks. Professor Julie Cohen argues for privacy understood as freedom for human development and dignity. Professor James Grimmelmann argues for privacy understood as contextual integrity.

But these frameworks haven't penetrated federal court doctrine. Judges still cite Knotts. Judges still think about privacy as reasonable expectation in specific locations. Judges still evaluate technology in isolation rather than as systems.

The Norfolk ruling reveals the inadequacy of this approach. A system that captures hundreds of ALPR images per person per month, that retains that data for months, that's accessible to multiple agencies and to a venture-backed private company, and that enables automated tracking based on algorithmic processing shouldn't pass constitutional scrutiny. But under the Knotts framework, it does.

That's the real problem. It's not ALPR specifically. It's the entire framework courts use to evaluate privacy claims.

The Appeal and Timeline: When Might This Be Overturned

The Institute for Justice has promised an appeal. The appellate process will take time. First, the plaintiffs must file their notice of appeal, which typically happens within 30 days of the trial judge's ruling. Then the case goes to the U. S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, which covers Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and West Virginia.

The Fourth Circuit is known as a relatively conservative court, but it has sometimes been receptive to Fourth Amendment privacy arguments. The plaintiffs will file a brief arguing that Judge Davis's application of Knotts was incorrect. Norfolk will file a counter-brief defending the ruling.

Oral arguments will likely happen 12-18 months after the briefs are submitted. That means we're looking at sometime in 2026 or 2027 for appellate oral arguments. The Fourth Circuit might rule within 6-12 months of oral arguments.

If the Fourth Circuit reverses Judge Davis's ruling, the case could potentially go to the Supreme Court. The Institute for Justice might seek certiorari, asking the Supreme Court to review the decision. The Supreme Court receives thousands of cert petitions annually and grants only about 70. But ALPR cases, especially those raising novel Fourth Amendment questions about mass surveillance, would likely be seen as worthy of Supreme Court review.

The entire process could take 4-6 years. That's a long time. By then, ALPR networks will have expanded significantly. More jurisdictions will have deployed cameras. More surveillance infrastructure will be in place.

This highlights an important problem with privacy law: courts move slowly. Technology moves quickly. By the time courts develop legal doctrine around ALPR technology, the technology will have already been deployed at massive scale. The privacy harms will already have occurred.

This suggests that relying on courts to protect privacy is insufficient. Legislatures need to act faster. Privacy advocates need to organize politically. People need to make privacy protection a voting issue. Democracy needs to keep pace with technology.

Conclusion: Privacy in the Age of Ubiquitous Surveillance

The Norfolk ALPR ruling is a moment of reckoning. It's a federal court's declaration that mass surveillance, conducted by AI systems, operated by private corporations, and accessible to law enforcement agencies, is constitutional. It's a legal validation of the principle that if you're on a public road, you have no right to privacy in your movements, even when those movements are tracked by millions of cameras, even when that data is retained for months, even when sophisticated algorithms analyze patterns and behaviors.

But it's also a moment of opportunity. The ruling is so clearly problematic that it might trigger a legislative backlash. Cities like Santa Cruz and Charlottesville are already showing that elected officials can reject ALPR technology despite federal courts approving it. States are drafting legislation to restrict ALPR deployment and use. Civil society organizations are mobilizing to challenge the technology.

The Institute for Justice's appeal might succeed. The Fourth Circuit might reconsider Knotts. The Supreme Court might adopt a more sophisticated framework for evaluating surveillance technology. Or courts might continue permitting mass surveillance while legislatures restrict it.

But one thing is certain: the Norfolk ruling won't end the ALPR debate. It will intensify it. It will clarify that Americans who value privacy can't rely on the Constitution to protect them from surveillance technology. They have to rely on democracy, on elected representatives, on political organizing, on pushing back against expansion of surveillance infrastructure.

The next decade will determine whether America becomes a society where every movement is tracked, recorded, and permanently stored, or whether we establish legal and policy boundaries protecting privacy in public space. The Norfolk ruling moves us toward the former. But it doesn't make that future inevitable. That depends on what happens next.

FAQ

What is an automated license plate reader and how does it work?

An automated license plate reader is a camera system that captures vehicle license plate numbers and metadata. Modern ALPR systems, particularly those deployed by Flock Safety, capture not just the plate number but also the vehicle's make, model, color, body style, roof features, stickers, decals, tow hitches, and other visual characteristics. The captured images and data are stored in a cloud database that law enforcement can search using natural language queries like "silver Honda with bike rack" to locate specific vehicles or patterns of vehicle movement.

Why did the Norfolk residents lose their lawsuit against Flock cameras?

The federal judge ruled that the residents could not demonstrate that Norfolk's ALPR system tracked "the whole of their movements," which the judge determined was necessary to violate Fourth Amendment rights. The judge applied the 1983 Supreme Court decision Knotts v. United States, which held that there is no reasonable expectation of privacy when traveling on public roads. Even though the residents' vehicles were captured hundreds of times over several months, the judge found this didn't meet the threshold for unconstitutional surveillance.

What are the privacy concerns with license plate reader networks?

The primary privacy concerns include comprehensive tracking of vehicle movements that reveals patterns about where people live, work, worship, seek medical treatment, and socialize. The aggregate data creates what legal scholars call a "mosaic" that reveals intimate information about beliefs, health status, political associations, and lifestyle choices. Additionally, ALPR data is often accessible to multiple agencies and private companies, can be retained for extended periods, and raises concerns about immigration enforcement, racial bias in policing, and corporate monetization of location data.

Has Judge Davis's ruling been appealed?

Yes, the Institute for Justice, a libertarian nonprofit representing the plaintiffs, announced it would appeal Judge Davis's decision. The case will go to the U. S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, a process that typically takes several years. The appeal might eventually reach the Supreme Court, though the timeline for any Supreme Court review is uncertain and could extend 4-6 years from the initial ruling.

Are other cities removing their Flock ALPR systems?

Yes, some cities have terminated their Flock contracts despite the Norfolk court validation. Santa Cruz, California and Charlottesville, Virginia, both ended their Flock agreements, citing privacy concerns and concerns about immigration enforcement. Additionally, California has implemented state legislation restricting ALPR use, and several other states including Massachusetts, Maryland, New Hampshire, and Vermont are considering or have implemented ALPR restrictions or bans.

What legal framework did Judge Davis use to approve the ALPR system?

Judge Davis based his decision primarily on Knotts v. United States, a 1983 Supreme Court case holding that individuals have no reasonable expectation of privacy in their movements on public roads. The judge applied this decades-old framework to modern ALPR technology without addressing concerns raised by more recent cases like United States v. Jones (2012), which suggested that aggregate surveillance over time might require different constitutional analysis than individual surveillance incidents.

Why are legal scholars critical of this ruling?

Legal scholars like Andrew Ferguson argue the ruling is "understandably conservative and dangerous" because it applies a 1983 legal standard to sophisticated 2025 surveillance technology. Critics contend that the ruling overlooks how ALPR systems create detailed patterns revealing religion, medical conditions, political beliefs, and associations. Additionally, the judge's requirement that surveillance must track "the whole of a person's movements" to be unconstitutional sets an impossibly high threshold that police can circumvent simply by not deploying cameras on every single street.

What role do states play in restricting ALPR technology if federal courts approve it?

Since federal constitutional law appears to permit ALPR deployment, states and localities must rely on legislative action to restrict the technology. States can pass laws requiring warrants before ALPR searches, limiting data retention periods, restricting federal immigration agency access, or even banning the technology outright. Different states are pursuing different approaches, creating a fragmented legal landscape where ALPR rules vary significantly by jurisdiction.

Could this ruling affect other surveillance technologies beyond license plate readers?

Yes, the ruling's logic could extend to other surveillance technologies like facial recognition, stingray cell tower simulators, and automated gate recognition systems. If courts accept the reasoning that tracking movements on public spaces without a warrant is constitutional so long as the system doesn't track "the whole" of movements, that framework could justify deploying nearly any surveillance technology at scale without constitutional impediment.

What can individuals do to protect their privacy regarding ALPR systems?

Individuals can file public records requests with their local police department to see what ALPR data exists about their vehicles. They can attend city council meetings to advocate for policies restricting ALPR deployment or use. They can support state legislation limiting ALPR authority. They can support organizations like the Institute for Justice that litigate privacy cases. And they can consider choosing to live in jurisdictions that have restricted rather than embraced ALPR surveillance technology.

TL; DR

- A federal judge ruled that Norfolk's 200-camera ALPR network is constitutional, dismissing a lawsuit just before trial began, reasoning that it doesn't track "the whole of a person's movements."

- The decision rests on outdated legal precedent: The judge applied a 1983 Supreme Court case (Knotts v. United States) to sophisticated 2025 AI surveillance technology that captures detailed vehicle metadata and enables comprehensive tracking.

- Legal scholars warn the ruling is dangerous: Andrew Ferguson and other privacy law experts argue the precedent could justify ALPR cameras on every street corner and enable tracking of sensitive locations like medical clinics, religious institutions, and protests.

- Some cities are rejecting ALPR despite the ruling: Santa Cruz and Charlottesville terminated Flock contracts citing privacy concerns, and several states are drafting ALPR restriction legislation, showing that legal permission doesn't mean policy acceptance.

- The real battle has shifted to state legislatures: With federal constitutional law permitting ALPR systems, privacy protection now depends on state and local legislation, political organizing, and democratic decisions about whether comprehensive surveillance is worth the public safety tradeoff.

Key Takeaways

- A federal judge ruled Norfolk's ALPR network is constitutional despite capturing vehicles hundreds of times, reasoning it doesn't track 'the whole of movements'

- The ruling applies 1983 legal precedent (Knotts v. United States) to sophisticated 2025 surveillance technology, creating dangerous precedent for mass surveillance

- Legal scholars warn the decision could justify ALPR cameras on every street corner and enable tracking of sensitive locations revealing religion, health status, and political beliefs

- Some cities like Santa Cruz and Charlottesville have terminated Flock contracts despite federal court approval, showing legislative action can restrict technology independent of constitutional law

- The real battle for ALPR restrictions has shifted to state legislatures, which are drafting diverse frameworks ranging from warrant requirements to outright bans

Related Articles

- Technology Powering ICE's Deportation Operations [2025]

- UK Pornhub Ban: Age Verification Laws & Digital Privacy [2025]

- Pegasus Spyware, NSO Group, and State Surveillance: The Landmark £3M Saudi Court Victory [2025]

- I Tested a VPN for 24 Hours. Here's What Actually Happened [2025]

- The Tina Peters Paradox: Trump's Pardon Powers Don't Work Here [2025]

- Meta Blocks ICE List: Content Moderation, Privacy & Free Speech [2025]

![License Plate Readers & Privacy: The Norfolk Flock Lawsuit Explained [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/license-plate-readers-privacy-the-norfolk-flock-lawsuit-expl/image-1-1769632667484.jpg)