Google Fast Pair Security Flaw: The Whisper Pair Vulnerability Explained

In mid-2025, security researchers from Belgium's KU Leuven University Computer Security and Industrial Cryptography group discovered something genuinely alarming about your wireless headphones. They found a vulnerability in Google's Fast Pair protocol that could let hackers standing near you intercept your audio devices, hijack their microphones, inject fake audio, and track your location. All within seconds.

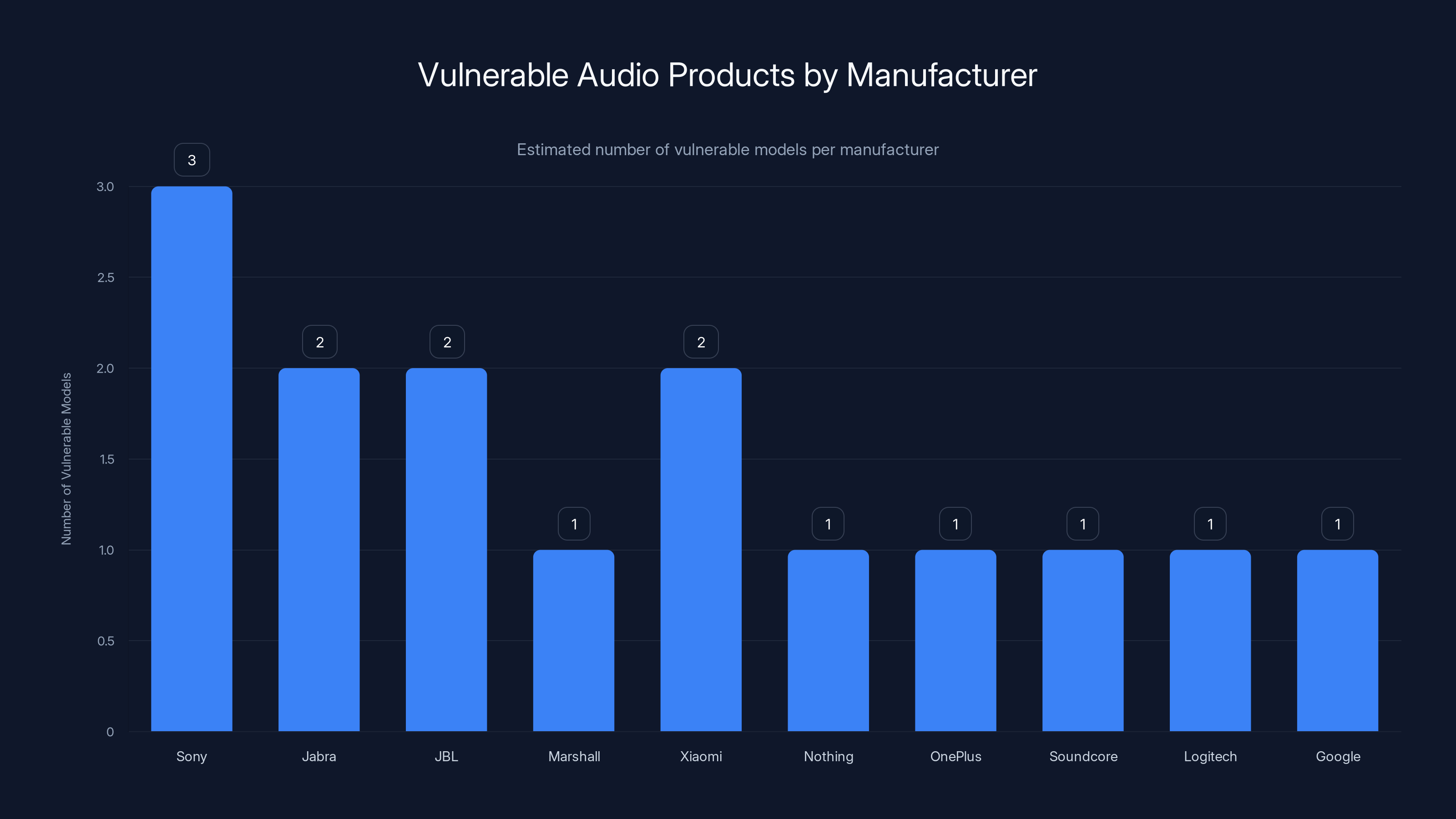

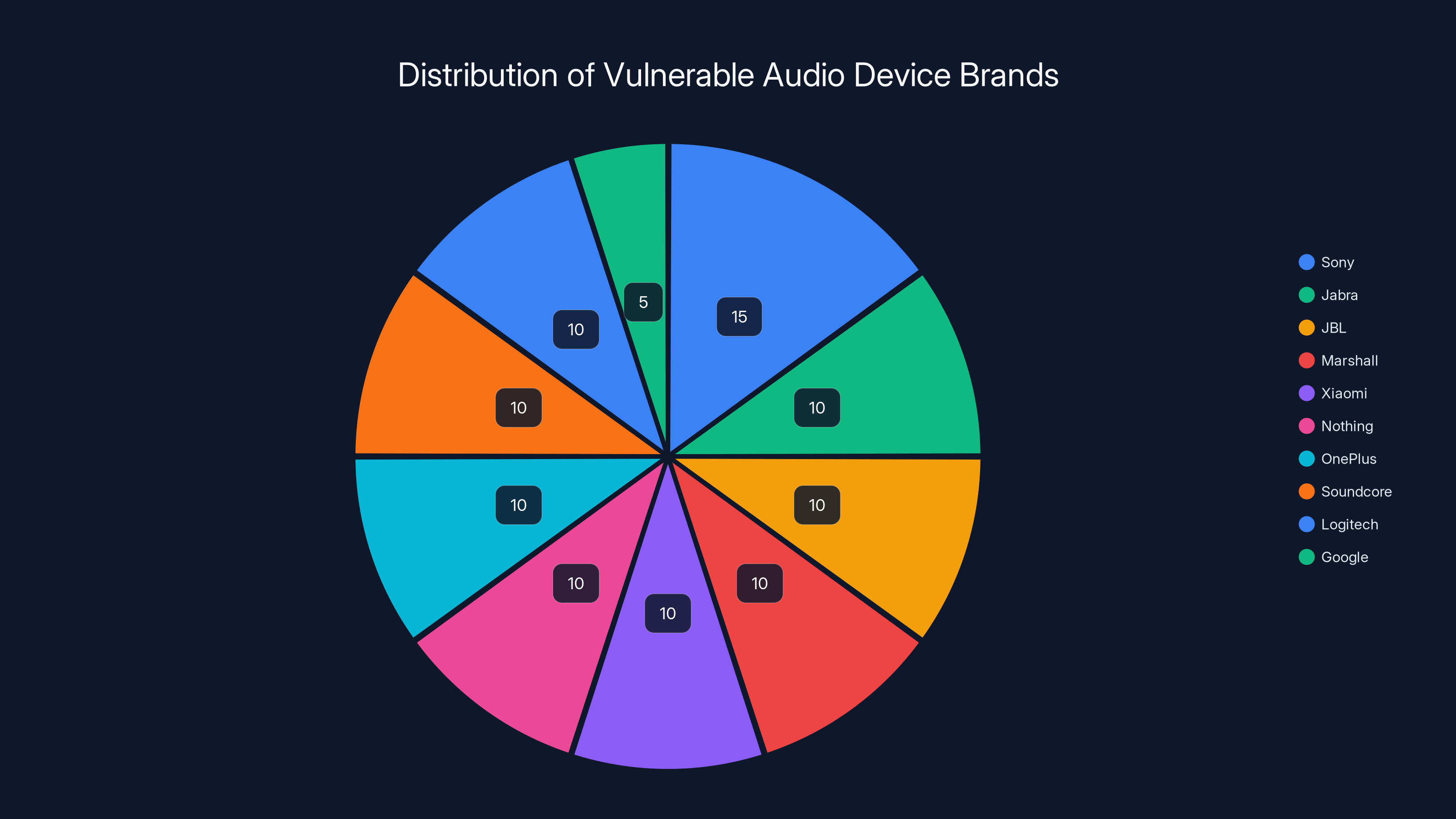

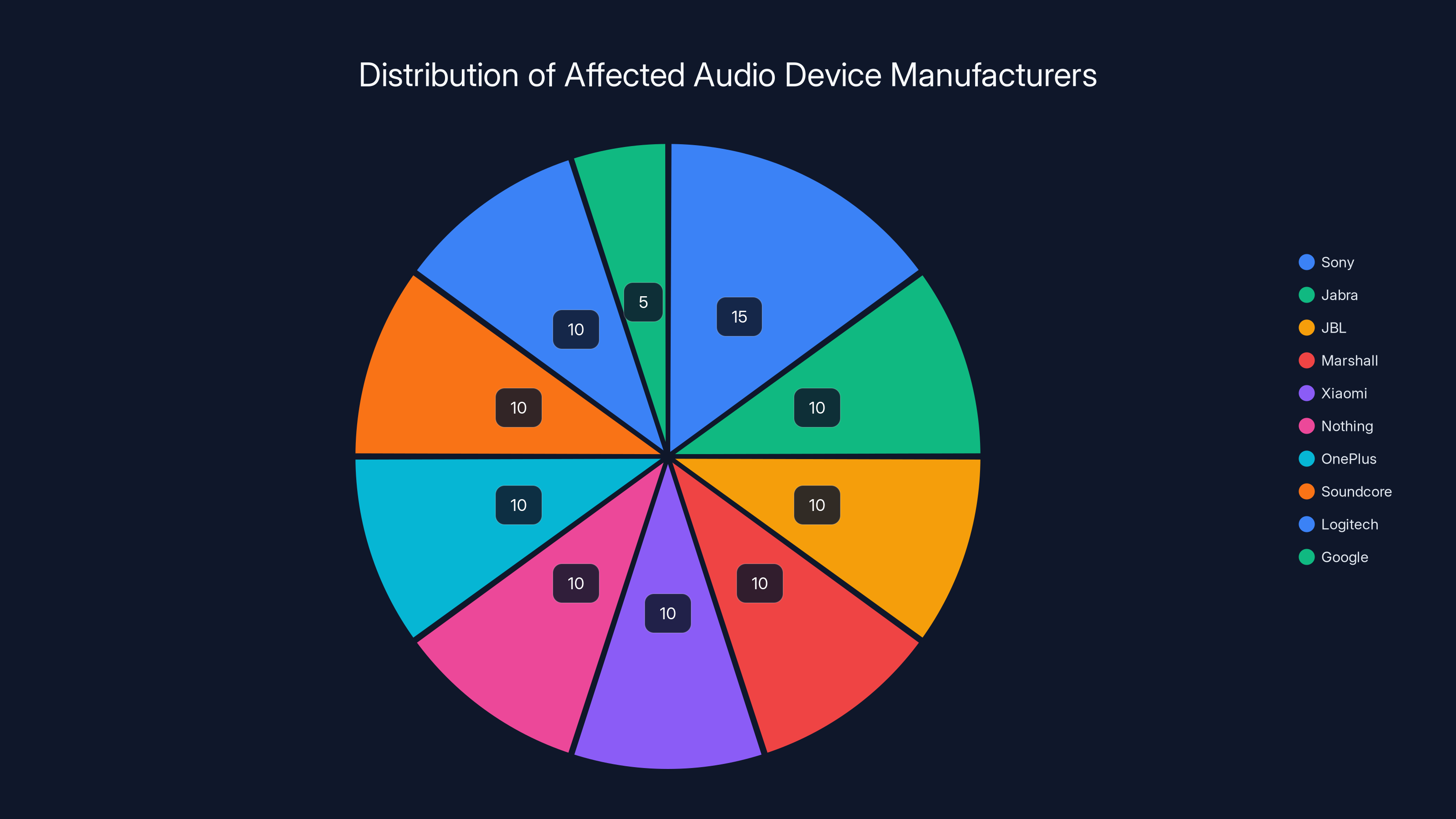

The vulnerability, christened "Whisper Pair" by the researchers, affects 17 different audio device models from 10 major manufacturers. We're talking Sony, Jabra, JBL, Marshall, Xiaomi, Nothing, One Plus, Soundcore, Logitech, and Google itself. If you own premium wireless earbuds or a Bluetooth speaker made by any of these companies in the last few years, there's a decent chance you're affected.

What makes this particularly concerning is how simple the attack is to execute. As one of the researchers explained to the press, a hacker within Bluetooth range needs nothing more than your device's model number (which is publicly available) and about 15 seconds of proximity. That's it. Not a complicated zero-day exploit, not specialized equipment, not even physical access to your device. Just proximity and a few seconds.

This isn't a theoretical exercise either. The researchers have demonstrated the attack repeatedly in controlled lab settings. They've shown how an attacker can pair with your earbuds without your knowledge, activate the microphone to listen to ambient sound around you, pump in fake audio, and use Google's Find Hub location service to track where you are. The attack chain is real, reproducible, and works against devices that were supposedly secure.

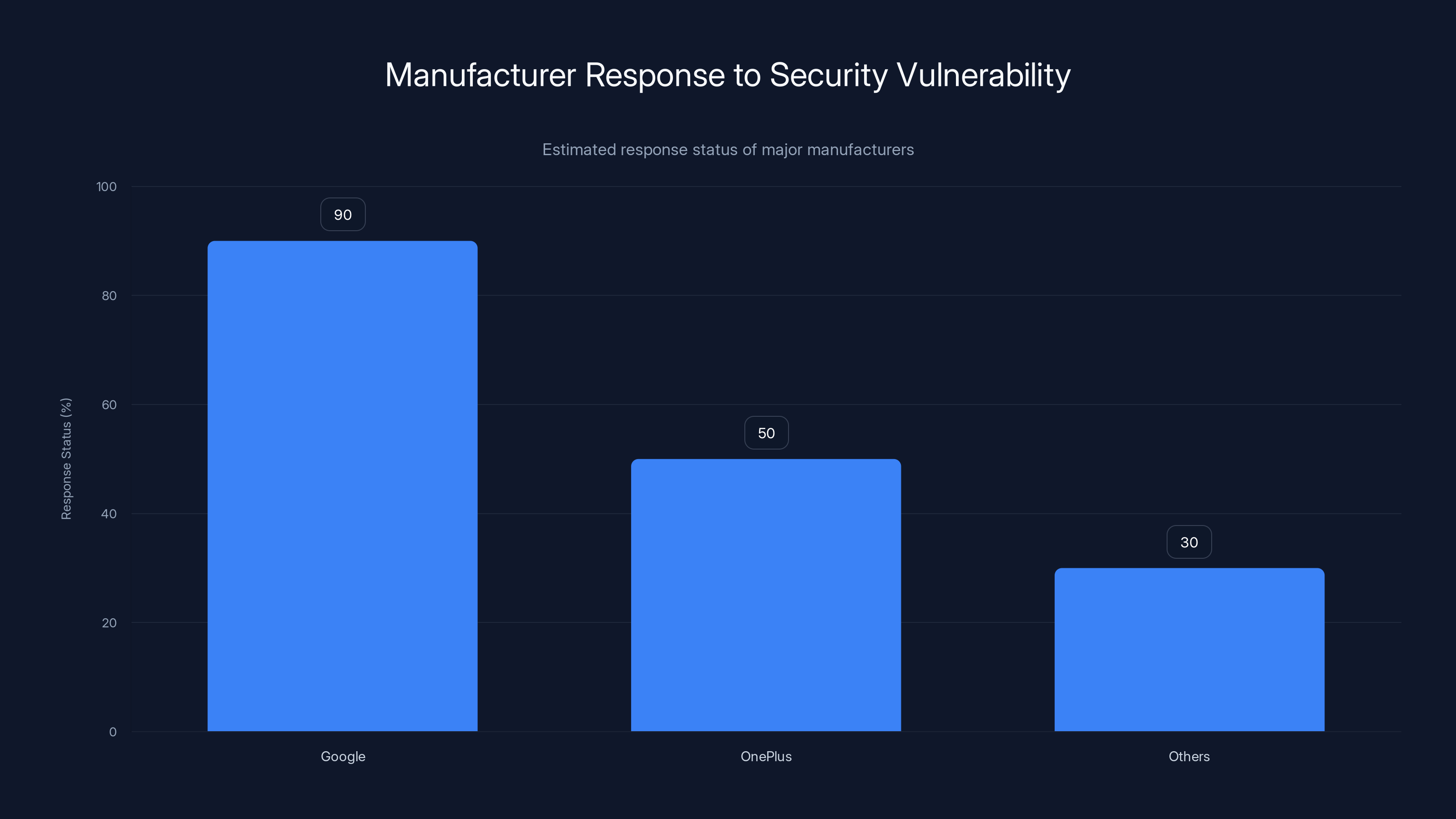

Google responded relatively quickly. The company began coordinating with hardware manufacturers in August when the researchers first reported the vulnerability. By September, Google had distributed recommended fixes to its OEM partners. The company also updated its Fast Pair Validator certification tool and tightened certification requirements for new devices. For its own Pixel Buds, Google claims the patch is already deployed. But for the other 16 affected devices from third-party manufacturers, the situation is messier. Some have patches available. Others might never get them.

That's where things get frustrating for regular users. Even if you wanted to update your headphones, you probably need to install the manufacturer's companion app first. Most people won't do that. They'll just keep using vulnerable devices indefinitely. The researchers flagged this exact problem as their biggest concern: outdated firmware leaves millions of devices exposed, not because of technical limitations, but because the update process is buried behind apps that most users never discover.

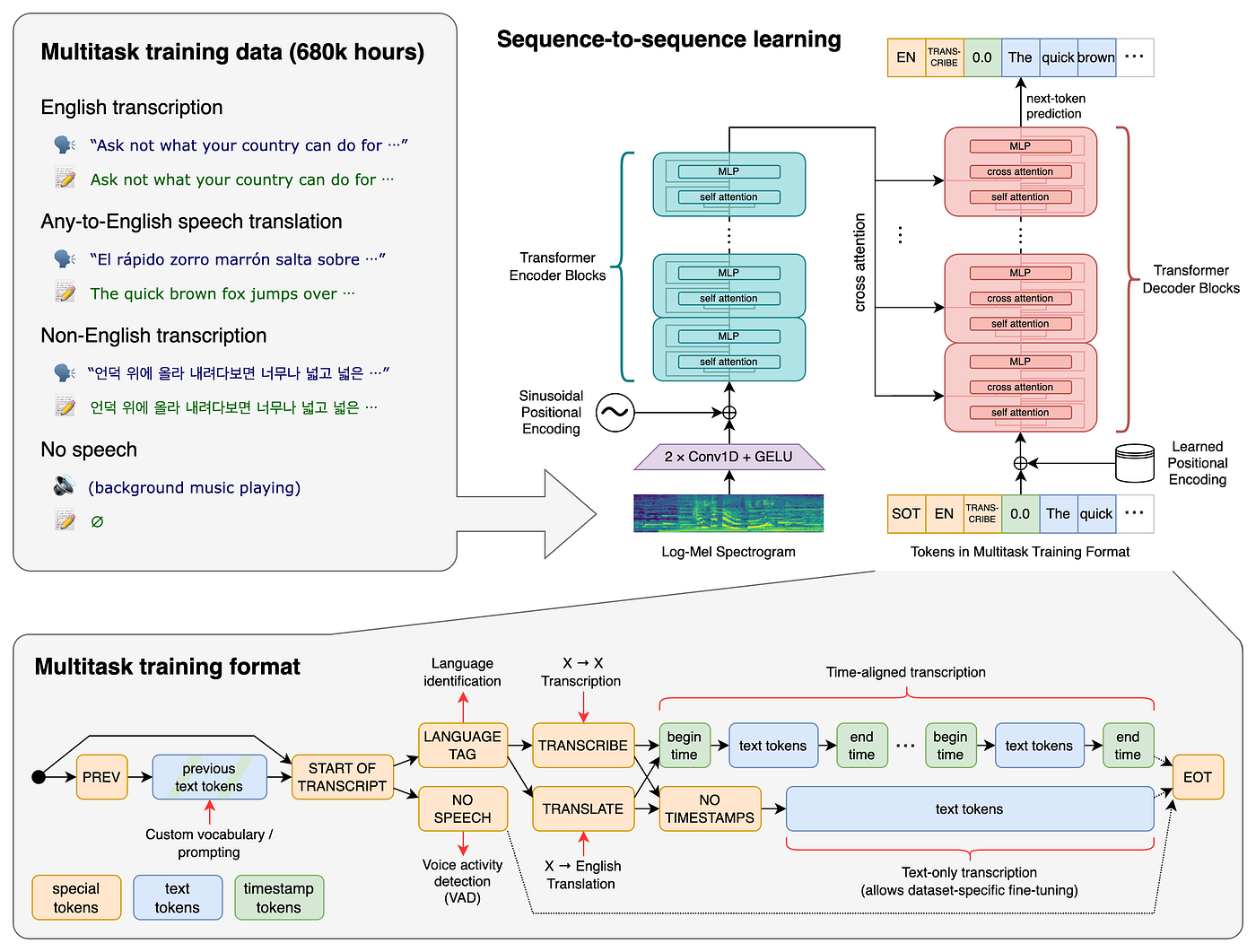

Understanding the Fast Pair Protocol Fundamentals

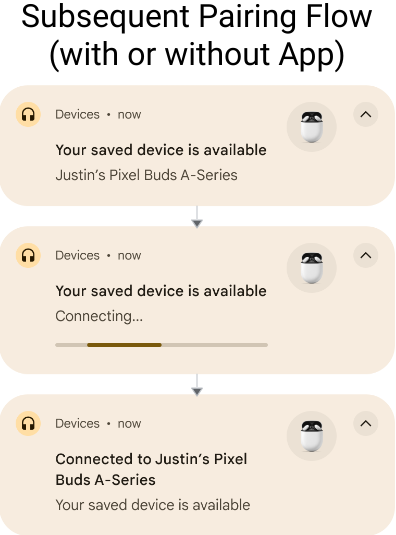

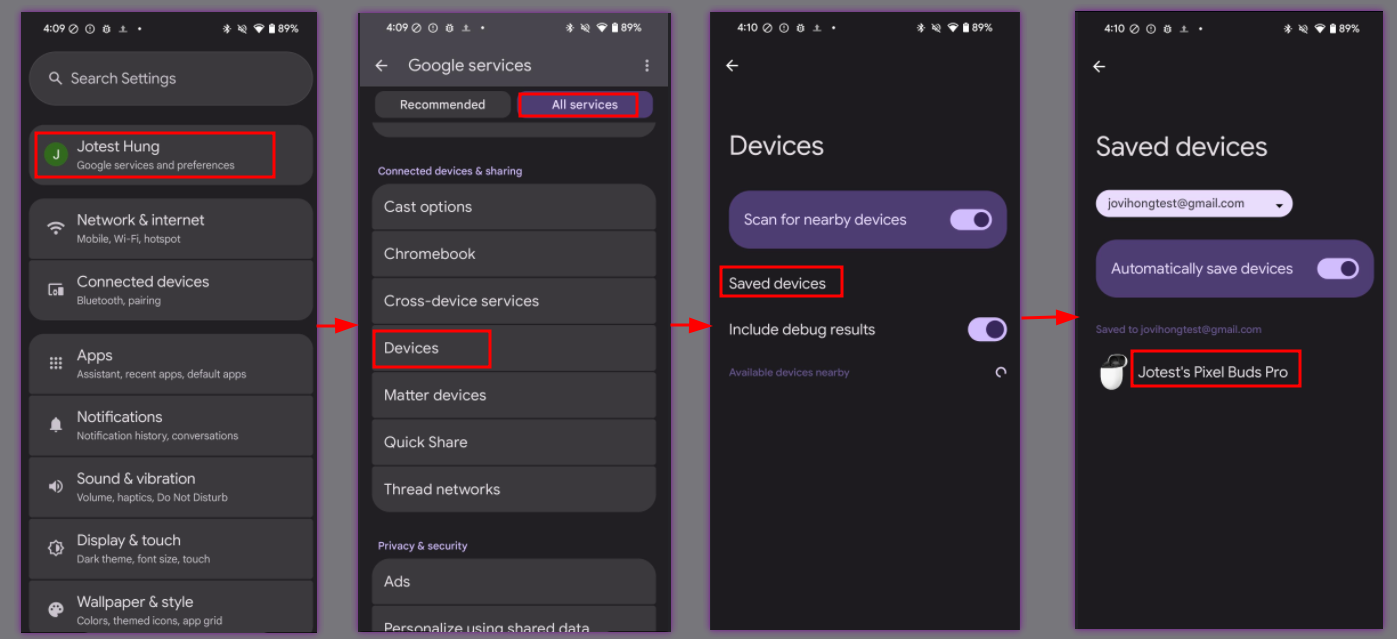

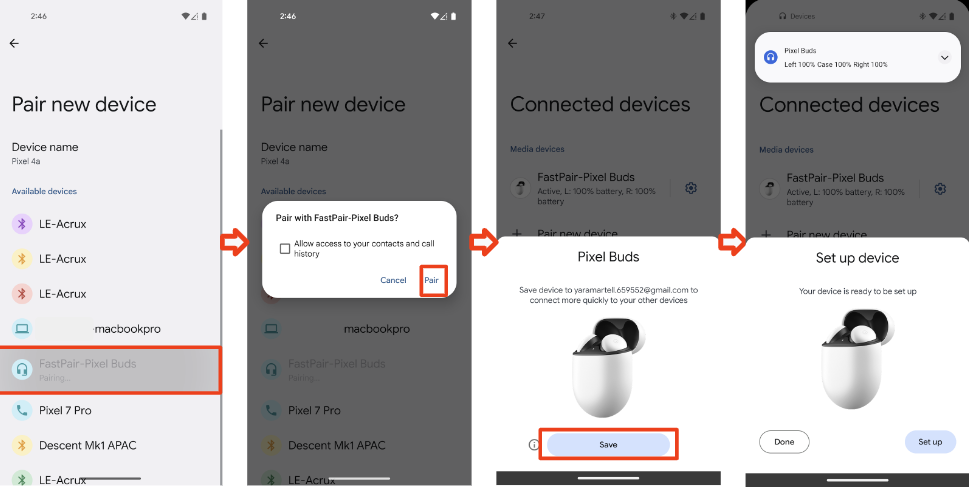

Before we can understand what went wrong with Fast Pair, let's talk about what it's supposed to do right. Fast Pair is Google's attempt to simplify Bluetooth pairing. Instead of digging through menus, hunting for device names, and typing PIN codes, you tap a button and boom, your phone recognizes the accessory and they're connected. It's fast, intuitive, and it generally works.

The protocol itself was designed with security in mind. Fast Pair is supposed to only allow new pairings when your audio device is actively in pairing mode. Once it's already paired with your phone, it should refuse any new pairing requests from other devices. This is a reasonable security assumption. If someone tries to pair with your earbuds, you'd expect the device to reject them unless you've explicitly put the device into pairing mode.

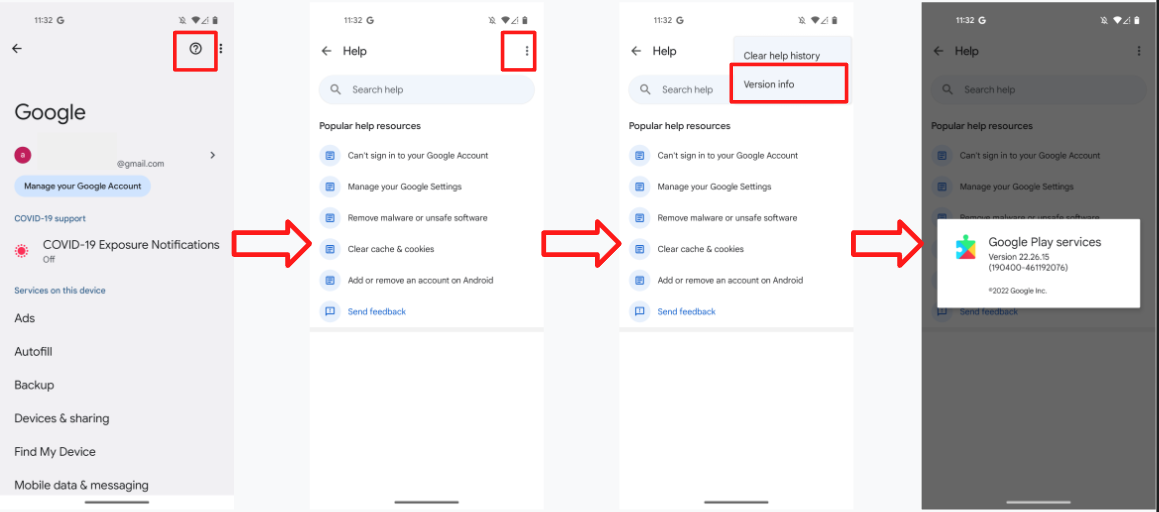

The magic behind this is something called "Fast Pair attestation." When a device is in pairing mode, it broadcasts cryptographic attestation data that proves to your phone it's legitimate hardware from a trusted manufacturer. Your phone verifies this attestation using Google's servers. If the attestation checks out, pairing proceeds. If it doesn't, the connection gets rejected.

The system depends on proper implementation at the hardware level. Manufacturers receive specifications from Google detailing exactly how to implement Fast Pair attestation. They're supposed to follow these specifications precisely. But here's the thing about specifications: they're often open to interpretation. One manufacturer might implement them correctly. Another might cut corners, misunderstand the requirements, or just get it wrong.

The protocol also relies on the fact that pairing is supposed to be intentional. You put your device in pairing mode. You initiate the connection from your phone. You confirm it. This ceremony is designed to prevent unauthorized access. But if that ceremony isn't properly enforced on the device side, an attacker can bypass it.

What makes Fast Pair elegant is also what makes it vulnerable in the wrong hands. The protocol is relatively simple. It doesn't have layers and layers of authentication checks. It trusts that manufacturers will implement the few critical checks correctly. If they don't, the whole security model collapses. And for 17 different devices, they didn't.

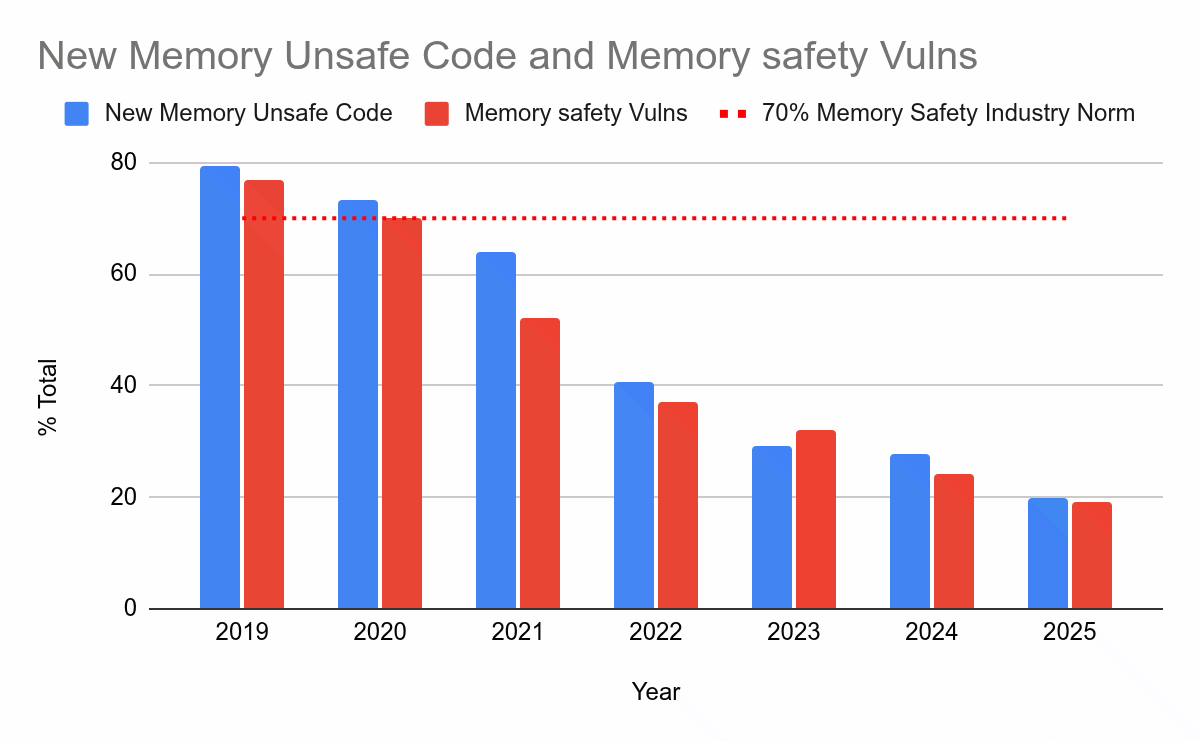

Sony leads with an estimated 3 vulnerable models, highlighting the widespread impact across major brands. Estimated data based on narrative.

How Whisper Pair Actually Works: The Attack Mechanism

Let's walk through exactly how Whisper Pair works, because understanding the mechanics is crucial for appreciating why this vulnerability is so serious.

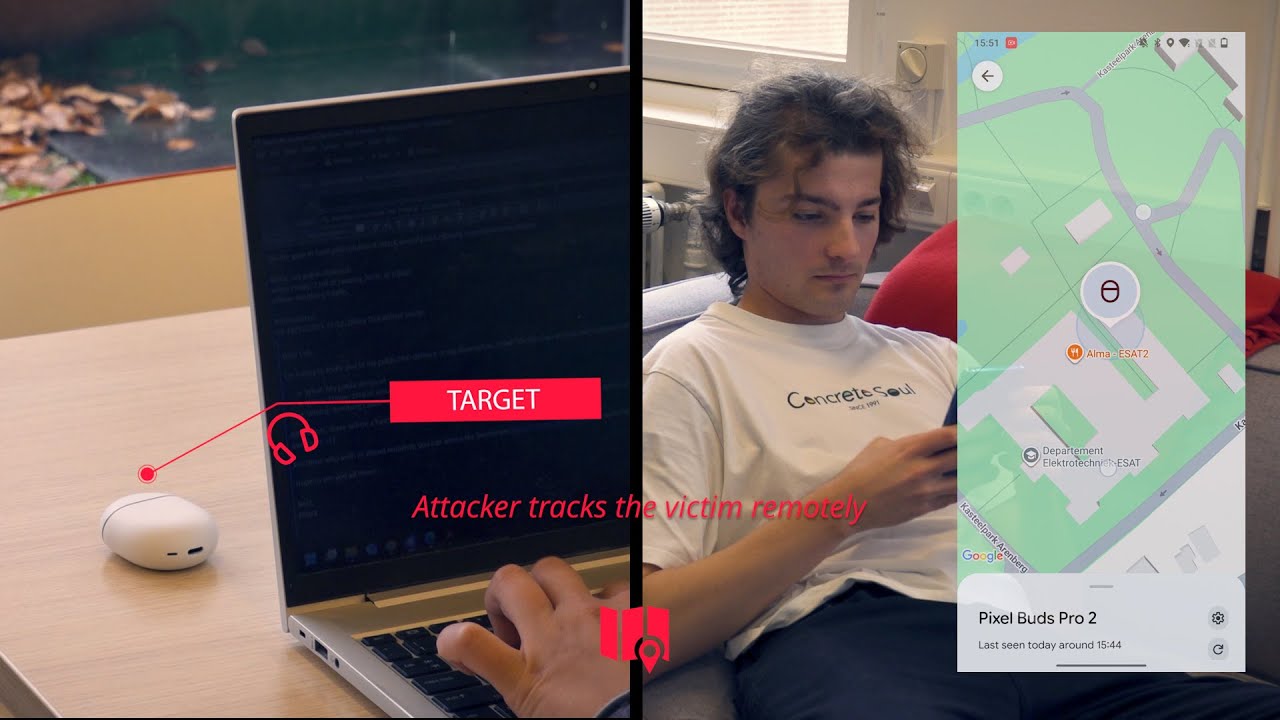

You're walking down the street wearing your wireless earbuds. The earbuds are connected to your phone. Everything seems fine. But an attacker standing nearby knows the model number of your earbuds (this is public information, found in the product manual or online). The attacker has a laptop or smartphone running modified software that can impersonate Google's Fast Pair service.

The attacker initiates a Fast Pair connection request to your earbuds. Because the earbuds' firmware doesn't properly validate whether they're in pairing mode, they respond to the request. They think maybe pairing mode is enabled. The device and the attacker's device begin the Fast Pair handshake.

Here's where the vulnerability kicks in. The earbuds don't properly verify the cryptographic attestation data. A correct implementation would check: "Is this attestation valid? Does it prove this is legitimate Google hardware?" But the vulnerable implementation skips this step or doesn't do it thoroughly. The handshake proceeds regardless.

Within seconds, a new pairing is established. The attacker's device is now paired with your earbuds without you doing anything. The earbuds don't alert you. Your phone doesn't notice. The connection is silent and invisible. From the user's perspective, nothing happened.

But from the attacker's perspective, they now have control. They can enable the microphone. Your earbuds were designed to pick up your voice for calls. Now they're picking up everything—conversations you're having, ambient sound around you, whatever audio exists in your proximity. The attacker is listening to everything.

Or the attacker can inject audio. They can play sounds directly through your earbuds. Imagine hearing instructions in your ears that seem to come from nowhere. The attacker can play music, speak to you, whatever they want. This could be used for harassment, social engineering, or worse.

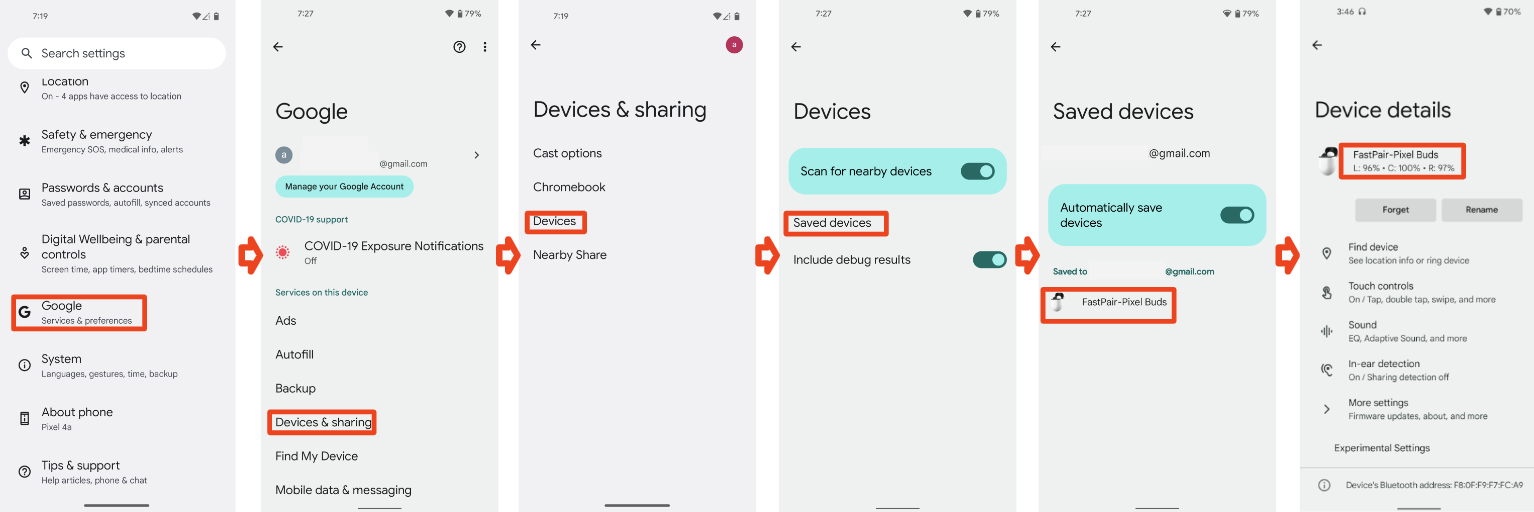

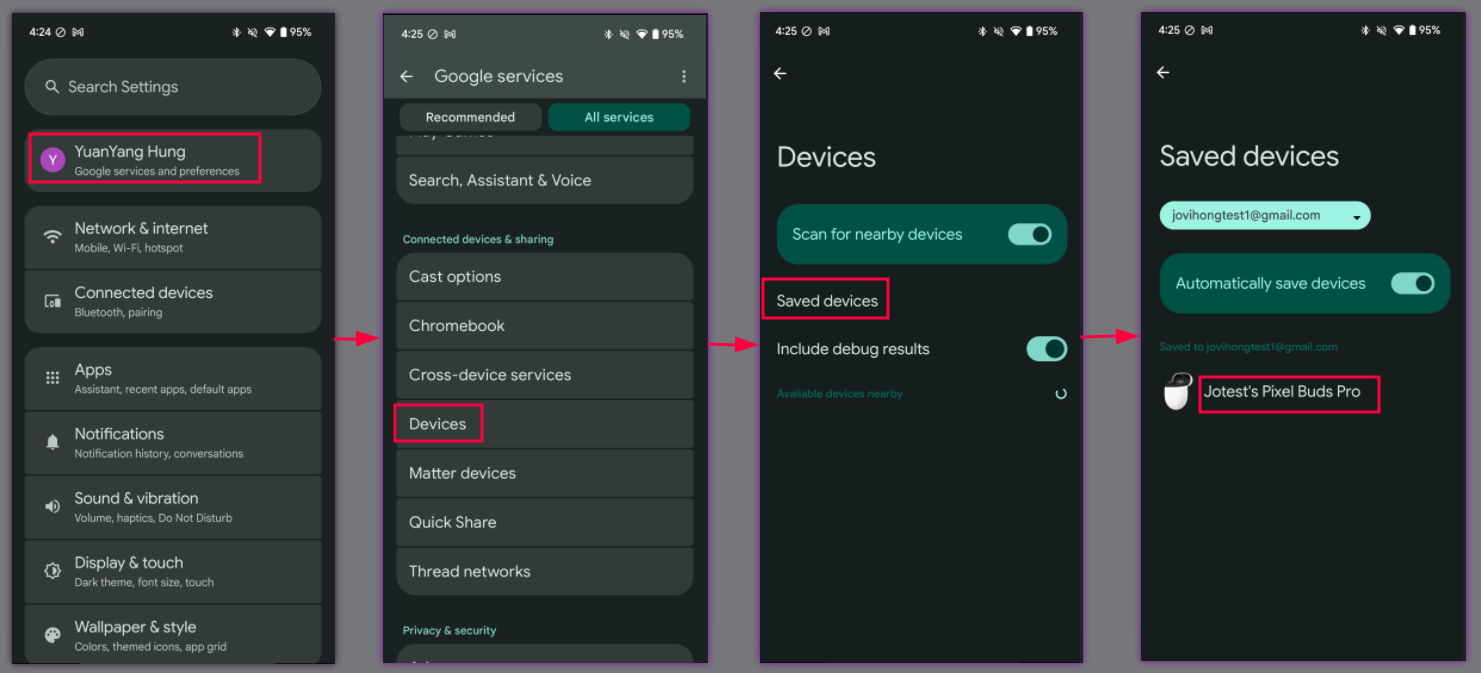

The most sinister part? The attacker can also use Google's Find Hub service against you. If you've previously paired your earbuds with your Google account, the attacker has access to location data. They know where your device is at any moment. And if the earbuds have never been paired with a Google account, the attacker can pair them with their own account and use Find Hub to track the device's location directly. Meaning they're tracking you.

The entire attack takes seconds. The researchers demonstrated completing the full chain—from initial Bluetooth discovery to microphone activation—in less than 15 seconds. More importantly, they demonstrated this in real-world conditions, not in some sterile lab setting with everything optimized to work perfectly. They did it with standard equipment. They did it repeatedly.

Estimated distribution of vulnerable devices shows Sony has the highest share, while Google has the lowest. Estimated data.

Affected Devices: Which Audio Products Are Vulnerable

The researchers identified 17 specific audio device models across 10 different manufacturers as vulnerable to Whisper Pair. This isn't a comprehensive list of every vulnerable device in existence. It's just the devices they tested and documented. There could be others. There might be more devices from these same manufacturers, or additional manufacturers we don't know about yet.

Sony has multiple models affected. We're talking some of their premium earbuds and headphones that people spend significant money on. Jabra, a company known for quality audio equipment especially in the professional space, has vulnerable devices. JBL, which is owned by Harman and is one of the world's largest speaker manufacturers, has affected products. Marshall, the legendary amplifier company that branched into consumer audio, has vulnerable models.

Xiaomi, the Chinese tech company, has affected devices. Nothing, the London-based startup making waves in the earbuds market, is on the list. One Plus, known for smartphones and audio products, has vulnerable gear. Soundcore, Anker's audio brand, is affected. Logitech, one of the most ubiquitous peripheral manufacturers globally, has vulnerable products.

And Google itself. The company that invented Fast Pair. Google's own Pixel Buds, their flagship wireless earbuds, were vulnerable. Though Google says they've already patched them. That's actually important context. Google could fix its own products quickly because they control the entire supply chain. Third-party manufacturers don't have that advantage.

What makes this list particularly jarring is that it spans multiple price points and market segments. These aren't cheap knockoffs with poor security. These are products from reputable companies with good engineering teams. Premium earbuds costing

The researchers created a searchable tool that lets you check if your specific device is vulnerable. You can look up your device model and see if it's on the affected list. This is helpful, but it's also a double-edged sword. On one hand, you can finally get a straight answer about whether you're at risk. On the other hand, that same information is available to potential attackers. They can use the same tool to identify targets in their vicinity.

The Timeline: Discovery, Disclosure, and Response

Understanding the timeline of this vulnerability matters because it shows how disclosure is supposed to work in cybersecurity, and also reveals the real-world challenges.

The researchers at KU Leuven likely discovered Whisper Pair sometime in early or mid-2024. Security research doesn't happen overnight. It probably took weeks of analysis and testing to understand the vulnerability fully, verify it worked across multiple devices, and document everything properly.

In August 2024, they responsibly disclosed the vulnerability to Google. This is standard procedure in security research. You find a flaw, you report it to the affected company before going public, giving them time to fix it. Google took the researchers' report seriously. The company immediately began coordinating with its hardware partners. This wasn't a dismissive "we'll look into it" response. Google engaged directly, acknowledged the researchers' findings, and started the remediation process.

By September 2024, Google had distributed recommended fixes to OEM partners. These are suggested patches that manufacturers could implement. Google also updated its Fast Pair Validator, the certification tool that tests whether devices properly implement the protocol. And they tightened certification requirements for new devices. Going forward, new devices should be tested more thoroughly to prevent similar issues.

The public disclosure happened in early 2025 when Wired published the full story with interviews and technical details. This is typical. There's usually some lag between initial discovery and public disclosure to give companies time to fix things. But eventually, the information becomes public because these are serious security vulnerabilities affecting millions of users.

Google's response has been reasonably transparent. The company acknowledged the vulnerability, explained what went wrong, described what they're doing about it, and committed to ongoing improvements. They said they've "not seen evidence of any exploitation outside of this report's lab setting," which is both reassuring and somewhat irrelevant. The fact that something hasn't been exploited yet doesn't mean it can't be.

What's noteworthy is Google's positioning this as an implementation problem with hardware partners, not a flaw in Fast Pair itself. The protocol is designed correctly, Google is saying. The problem is manufacturers didn't implement it correctly. This is technically true, but it's also kind of missing the point. If your protocol is so easy to implement incorrectly that 17 different products from 10 different companies all get it wrong in the same way, maybe your protocol needs to be designed more defensively.

Estimated data shows Sony has the largest share of affected models, highlighting the widespread impact of the WhisperPair vulnerability across major manufacturers.

Technical Deep Dive: Why the Implementation Failed

The core issue comes down to how manufacturers implemented the pairing mode check. Fast Pair is supposed to only allow new connections when a device is in pairing mode. Manufacturers are given specifications on how to implement this check. But the implementation details matter enormously.

One likely scenario is that manufacturers didn't properly validate the state of pairing mode before proceeding with Fast Pair authentication. Instead of checking "is pairing mode enabled right now?" they might be checking something like "has pairing mode been enabled in the last X seconds?" or "is there a pending pairing request?" These subtle differences in logic can create security gaps.

Another possibility is that the attestation verification wasn't as strict as it should be. The earbuds should cryptographically verify that the Fast Pair authentication is coming from legitimate hardware running legitimate code. But if that verification is perfunctory or skipped under certain conditions, an attacker can spoof it.

A third issue might be improper state management. Fast Pair has multiple states: looking for new pairing, already paired, reconnecting to existing pairing, etc. If the state machine isn't properly implemented, transitions between states might occur in the wrong order, allowing attacks that shouldn't be possible.

What's probably happening is a combination of these issues. The researchers noted that the vulnerability is present in the hardware implementations themselves, not in the Fast Pair protocol specification. This means the problem isn't something Google can fix with a software update. Hardware manufacturers need to update their device firmware. And getting firmware updates out to millions of devices is genuinely hard.

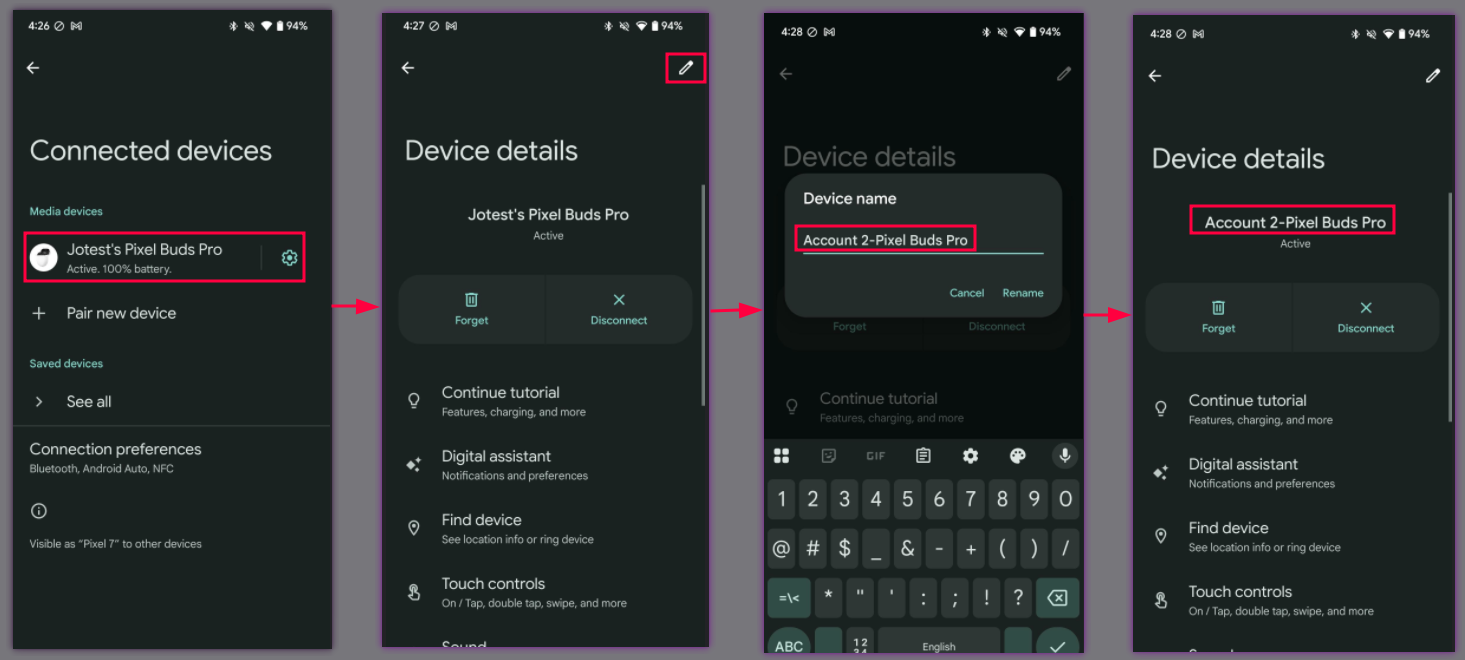

Most users never update their device firmware. They don't know it's necessary. They don't know how to do it. The update process is often buried inside a manufacturer's app that they've never heard of. So even after patches are available, most vulnerable devices remain unpatched for months or years, if they're ever patched at all.

The researchers specifically flagged this as their biggest concern. The technical fix is doable. Manufacturers can update their firmware. Google can provide better testing. But getting those updates deployed is the real challenge.

Security Implications: What Attackers Can Actually Do

Let's be concrete about what an attacker armed with Whisper Pair can actually accomplish, because the implications vary depending on your device, your situation, and what the attacker's motivation is.

First, microphone access. Once an attacker pairs with your earbuds, they can enable the microphone and listen to ambient sound around you. If you're in a meeting, they hear the meeting. If you're having a private conversation, they hear that too. They can listen to background conversations in cafes, offices, or homes. This is espionage-grade eavesdropping.

Second, audio injection. The attacker can pump fake audio directly into your ears. They could play instructions that seem to come from a trusted source. "This is your bank calling..." "Security verification required..." They could gradually gaslight you with false information. They could interfere with your ability to hear actual audio. The attack surface here is pretty wide.

Third, location tracking. If your earbuds are paired with a Google account, the attacker has access to location data through Find Hub. They can see where your device is. And since you're presumably wearing or carrying your earbuds, they're tracking you. Even if the earbuds have never been paired with a Google account, an attacker can hijack them and pair them to their own account, and then use Find Hub to track the device's location.

Fourth, repeated attacks. Once an attacker has successfully paired with your earbuds, they can continue attacking those specific earbuds for a long time. They don't need to repeat the initial pairing attack. They have a persistent connection to your device. Every time you use your earbuds, that attacker could potentially monitor them.

The threat model here is someone physically near you. An attacker can't execute this attack from across the world. They need to be within Bluetooth range, which is typically 30 feet or so depending on conditions. But Bluetooth range is larger than most people realize. In crowded public spaces like airports, trains, or conferences, an attacker could potentially target many people in sequence.

What makes this particularly insidious is that users have no way to detect the attack. Your earbuds don't alert you that a new device has paired. Your phone doesn't notify you. The attacker is completely invisible. You could be under surveillance and have no idea.

Google did implement one protection: the Find Hub patch. When the attacker tries to use Find Hub to track a device that hasn't been paired with any Google account, Google's servers now reject the request. But the researchers found a workaround to this protection within hours. So that's not even a reliable defense.

The timeline shows the progression from discovery in early/mid-2024 to public disclosure in early 2025, highlighting the stages of responsible disclosure in cybersecurity. Estimated data.

Manufacturer Response: Who's Fixed It and Who Hasn't

The response from affected manufacturers has been predictably mixed. Some have issued patches relatively quickly. Others are still "investigating the issue." Some will probably never issue a patch.

Google claims its Pixel Buds are already patched and protected. That's impressive speed, but Google controls both the hardware and software, so they can move fast. They can push updates directly to users without waiting for carrier approval or user action.

One Plus issued a statement saying it's investigating the issue and will "take appropriate action to protect our users' security and privacy." That's deliberately vague language. "Take appropriate action" could mean anything from pushing out a patch next week to quietly discontinuing the affected model.

The other manufacturers are largely silent. They've had time to respond since the initial disclosure. Some have probably issued patches that nobody knows about because their communication is terrible. Others might be working on patches but can't promise anything because their firmware update process is slow and bureaucratic. A few might be hoping people don't notice and will eventually upgrade to newer models.

This is where the system breaks down. Even when manufacturers can fix the vulnerability, they don't always communicate clearly to users. They don't send notifications saying "patch available, here's how to install it." They don't make updates automatic. They don't explain what the vulnerability was or why the update matters. So most users never hear about patches that would protect them.

Manufacturers also have limited ability to push firmware updates to older devices. They want to focus engineering resources on current products. A device from 2021 or 2022 might be considered "legacy" by the manufacturer even if you're still actively using and relying on it. Getting a security patch for legacy hardware is often impossible.

How to Protect Yourself: Practical Mitigation Steps

The most straightforward protection is to update your device firmware to the latest available version. If your manufacturer has released a patch, install it. This solves the Whisper Pair vulnerability directly.

Here's the practical reality though: most users won't do this. The update process is annoying. You have to install the manufacturer's app. You have to navigate menus to find the firmware update option. You have to let the update download and install while staying within range. It's friction all the way down.

If you can't or won't update, you have a few options. First, limit exposure. Don't wear or use vulnerable devices when you're worried about eavesdropping. If you're in a sensitive meeting, use wired headphones instead. If you need privacy, don't wear wireless earbuds.

Second, be aware of Bluetooth range. Whisper Pair requires an attacker to be within Bluetooth range, typically 30 feet. In open outdoor spaces, that's a smaller threat surface than in crowded indoor spaces. In a crowded coffee shop, there could be dozens of potential attackers. In your own home, there's just the people you live with.

Third, use a VPN on your phone. This doesn't directly prevent Whisper Pair attacks, but it prevents some of the follow-on attacks. If an attacker is trying to do something beyond just eavesdropping, VPN encryption might slow them down.

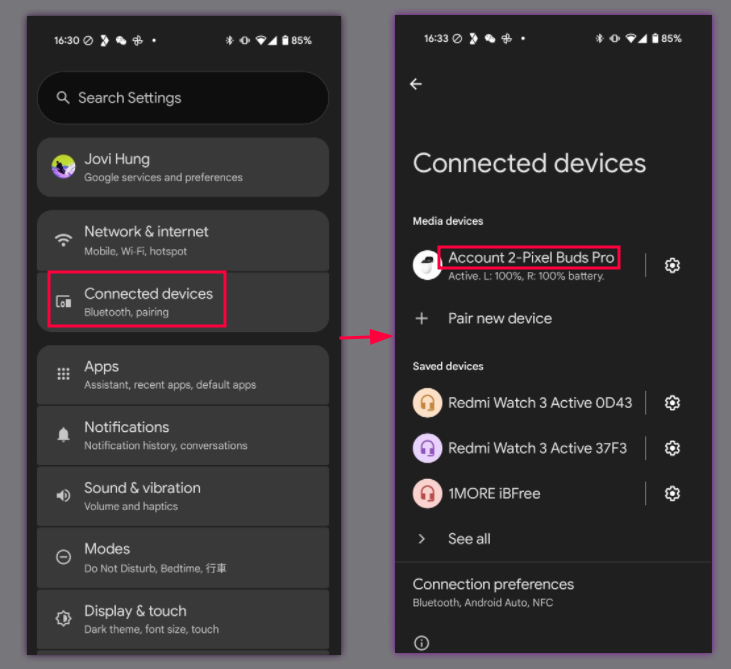

Fourth, regularly review your paired devices. In your phone's Bluetooth settings, check what devices are paired. If you see a device you don't recognize, remove it. This won't prevent the initial Whisper Pair attack, but it might help you notice if you've been compromised.

Fifth, consider switching to wired headphones for sensitive situations. Yes, wired is annoying. Yes, it's inconvenient. But it's also completely immune to wireless attacks. Sometimes old technology is better technology.

Sixth, if your device manufacturer has an app for your earbuds, check it regularly for firmware updates. Some manufacturers pushed patches through their apps before the public even knew about the vulnerability. Get notifications turned on if the app supports it.

Google has quickly patched their devices, while OnePlus is still investigating. Other manufacturers are largely unresponsive. (Estimated data)

The Bigger Picture: Certification and Quality Control Issues

Whisper Pair isn't just a bug. It's a symptom of deeper problems in how hardware gets certified and tested.

Google has a Fast Pair certification process. Manufacturers submit their devices for testing. Google's certification tool supposedly validates that the devices properly implement Fast Pair. If devices pass certification, they're supposed to be secure. But 17 certified devices all have the same vulnerability.

What does that say about the certification process?

Either the testing wasn't thorough enough, or the testing didn't specifically look for this type of vulnerability, or the test cases weren't comprehensive. Probably all three. Security testing is hard. You have to think like an attacker. You have to imagine how an attacker would try to exploit the implementation. And you have to test for those specific attack scenarios.

Google says it's updating the certification process going forward. New devices will be tested more thoroughly. Certification requirements are tighter. But that only protects future devices. The billions of vulnerable devices already out in the world won't automatically become secure.

There's also a question about who bears responsibility for this. Is it Google's fault for having a protocol that's easy to implement incorrectly? Is it the manufacturers' fault for not implementing it correctly? Is it the certification process's fault for missing the vulnerability? Is it the users' fault for not installing firmware updates?

The answer is probably all of them share some responsibility. But practically speaking, users are the ones bearing the consequences. They're the ones with vulnerable devices in their homes and pockets. They're the ones potentially at risk of eavesdropping.

Device Security Going Forward: What's Changing

Google is making several changes to prevent similar vulnerabilities in the future.

First, they're updating the Fast Pair Validator tool. This is the tool manufacturers use to test their implementations before submitting for certification. By making it more comprehensive and more stringent, Google is raising the bar for what passes certification.

Second, they're tightening certification requirements. New devices will have to meet higher security standards to be certified. This might slow down the process of getting new audio devices to market, but it should catch implementation flaws earlier.

Third, they're likely strengthening the Fast Pair specification itself. They're probably adding more explicit requirements about pairing mode validation, more detailed attestation checks, and more thorough state management requirements. This reduces the room for manufacturers to interpret the spec in insecure ways.

Fourth, Google is probably improving their security testing internally. They should be having dedicated security researchers try to break Fast Pair implementations during the certification process. They should be red-teaming manufacturers' implementations. They should be thinking like attackers.

But here's the hard truth: these changes only help future devices. They don't help the devices that have already shipped and are sitting in homes right now. Those devices exist in a security debt situation. They'll remain vulnerable until manufacturers push out firmware updates, and most never will.

Google could theoretically force manufacturers to push security updates by threatening to remove them from the certified devices list. But that's a nuclear option that might anger hardware partners. Plus, manufacturers could just push out updates that break other functionality, making users' devices worse.

Firmware updates are the most effective protection against WhisperPair, while using wired headphones also offers strong security. Estimated data based on typical security measures.

The User Education Problem: Why People Don't Update

Here's something that rarely gets discussed in security disclosures: the vast majority of people don't know firmware updates exist for their audio devices, and even those who do know often don't install them.

Why? Because it's inconvenient. To update your earbuds, you typically need to:

- Install the manufacturer's companion app (which you probably didn't know existed)

- Create an account or log into an existing account

- Pair your earbuds with the app

- Navigate through menus to find the firmware update section

- Initiate the update and wait while it downloads and installs

- Keep your earbuds and phone near each other during the entire process

- Verify the update was successful

That's a lot of friction for a security update that addresses a vulnerability most users don't know about and don't understand. Compare that to updating your smartphone, which usually takes two seconds and you get a notification about it.

Manufacturers could make this easier. They could send push notifications when updates are available. They could make updates automatic. They could make the update process simpler. But they often don't, because firmware updates are expensive. They require engineering resources, testing, quality assurance. It's not in manufacturers' business interests to make updates seamless and automatic. The more work they have to do, the less margin they have on products.

So users are caught between impossible choices. Use vulnerable devices, or figure out how to update them, which is a process most users can't complete successfully.

The security industry keeps saying "users should update their devices." Users keep not doing it. At some point, the industry has to acknowledge that relying on users to proactively install firmware updates is a failed strategy.

Comparing Whisper Pair to Other Bluetooth Vulnerabilities

Whisper Pair isn't the first serious vulnerability in Bluetooth technology. There have been others, and understanding how Whisper Pair compares helps put it in perspective.

Bluetooth Sniffing attacks are probably the oldest category of Bluetooth vulnerability. These involve capturing unencrypted Bluetooth packets to steal information. Bluetooth has supported encryption since early versions, but it's not always enabled, and early encryption implementations were breakable.

The KNOB attack (Key Negotiation of Bluetooth) in 2019 showed that attackers could downgrade Bluetooth encryption to weaker versions. An attacker could force a connection to use less secure encryption, making it easier to break. This affected virtually all Bluetooth devices for years.

There have been firmware implant vulnerabilities where attackers could inject malicious code into Bluetooth devices. There have been battery-draining denial-of-service attacks. There have been eavesdropping vulnerabilities in specific implementations.

What makes Whisper Pair notable is that it's a widespread vulnerability across multiple manufacturers affecting a huge number of devices, it's relatively easy to execute, it doesn't require specialized equipment, and it gives an attacker multiple capabilities (eavesdropping, audio injection, location tracking).

Previous Bluetooth vulnerabilities often required either physical access, specialized equipment, or deep technical knowledge. Whisper Pair just requires proximity and a few seconds. That makes it more practically dangerous.

Industry Standards and Regulatory Response

There's been surprisingly little regulatory response to Whisper Pair specifically, but it's part of a larger conversation about IoT device security.

The FTC has been increasing pressure on manufacturers to handle security vulnerabilities properly. But there's still no legally binding requirement that devices be patched for security vulnerabilities. A manufacturer can discontinue support for a product the day after launch and that's legal, even if the product is insecure.

Some countries are considering right-to-repair legislation, which could indirectly affect this. If users have a legal right to repair or modify their devices, maybe they have a right to updated firmware too. But that's a stretch.

The real issue is that there's no established standard for how long manufacturers should support security updates. Smartphones typically get 3 to 5 years of security updates. But audio devices? There's no standard. Some manufacturers support devices for years. Others support them for months.

What would actually help is if Google required longer security support as a condition of Fast Pair certification. "You want your device certified? You commit to security updates for at least 3 years." But implementing that would be controversial with manufacturers.

The other piece that's missing is transparency. Manufacturers don't always announce security vulnerabilities or patches. They'll quietly push out updates without explaining what was fixed. This makes it impossible for users to make informed decisions about whether to update.

Future of Fast Pair: Is the Protocol Still Viable?

The Whisper Pair vulnerability raises a bigger question: is Google's approach to Fast Pair the right one, or does the protocol need to be fundamentally rethought?

Fast Pair is designed to be simple and fast. That's the whole point. It's supposed to make pairing as easy as possible. But that simplicity might be incompatible with proper security.

Alternative approaches exist. Some companies use NFC (near-field communication) for pairing, which requires devices to be very close together, making attack much harder. Some use QR codes that you scan to verify the connection. Some use multi-factor authentication with phone confirmation.

These alternatives are more cumbersome. They require more user action. They're not as seamless as Fast Pair. But they might be more secure.

Google could redesign Fast Pair to require more explicit confirmation from the user. "Your phone received a pairing request from a Sony headphones device. Confirm on your earbuds by pressing the button three times." That's more annoying, but it's more secure because the user is consciously participating in the authorization.

Google could also require that pairing mode be explicitly enabled each time. Instead of relying on manufacturers to properly implement a pairing mode check, the protocol could require that the user physically enable a mode on the device before any new pairing is allowed. This would need to be a deliberate action each time, not something that persists for minutes or hours.

There's probably a middle ground where Fast Pair becomes more secure without becoming significantly less convenient. But it would require redesign and it would require manufacturers to implement it correctly. Given that they didn't get it right the first time, there's no guarantee they'd get it right the second time.

What This Means for Consumers: Long-Term Implications

For consumers, Whisper Pair raises uncomfortable questions about device security and privacy.

First, it's a reminder that wireless devices can be vulnerable in ways you might not expect. You might think your earbuds are secure because you're not connected to the internet, but they can still be hacked via Bluetooth. Physical disconnection from the network doesn't equal security.

Second, it highlights the challenge of maintaining security for years after purchase. You buy earbuds, they work fine, you forget about them. Years later, a vulnerability is discovered. If the manufacturer stops supporting the device, you're stuck with a vulnerability. You could be at risk indefinitely.

Third, it shows the difference between devices that get patched and devices that don't. If you buy from a manufacturer with a good track record of supporting devices, you're probably okay. If you buy from a manufacturer known for poor support, you might have a vulnerability device for years.

Fourth, it suggests that some of the features we like about modern devices (seamless, automatic pairing) have security trade-offs. The convenience we get from Fast Pair comes at the cost of reduced security. That might be an acceptable trade-off for many people. But it's a trade-off worth understanding.

Fifth, it indicates that the security of the device depends not just on the device maker but on Google maintaining their certification process and security infrastructure. If Google stops supporting Fast Pair devices in the future, or if they reduce their security efforts, that could become a larger problem.

Long term, consumers probably need to be more thoughtful about device purchase decisions. Buying from manufacturers with good security track records matters. Using devices from companies that have been around for decades and are likely to continue supporting products matters. Being willing to replace devices when they fall out of support matters.

It's not a perfect solution, but it's better than trusting that everything will magically stay secure forever.

Best Practices for Audio Device Security

If you own wireless audio devices, here are concrete practices that actually help:

Install all available firmware updates immediately. Don't wait. Don't assume it's not important. Firmware updates often contain security fixes. Install them as soon as they're available.

Keep your phone's operating system updated. Your phone is the hub for all your Bluetooth devices. If your phone is vulnerable, everything connected to it could be at risk. Keep your OS updated.

Use strong passwords for any accounts linked to your devices. Many audio devices let you create accounts. Use unique, strong passwords. If an attacker compromises your account, they might gain access to your devices.

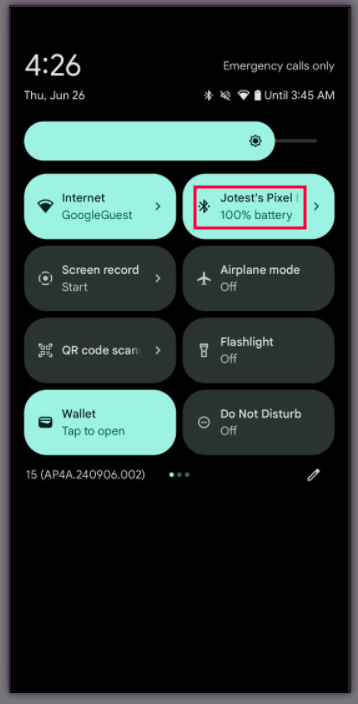

Review paired devices regularly. Check your phone's Bluetooth settings and verify that every paired device is one you actually use and recognize. Remove anything unfamiliar.

Be skeptical of devices you don't recognize. If your phone offers to pair with a mysterious Bluetooth device, decline it. An attacker might be trying to pair with your phone.

Disable Bluetooth when you don't need it. Actively using Bluetooth has some risk. If you're not actively using your earbuds or speakers, turn off Bluetooth on your phone. This eliminates the attack surface entirely.

Consider the manufacturer's track record before buying. Research how well the manufacturer supports their devices. Do they push security updates regularly? How long is the support period? This matters more than you might think.

For sensitive situations, use wired alternatives. If you're having confidential conversations or you're somewhere that requires maximum security, use wired headphones. Yes, it's less convenient. But it's also completely immune to wireless attacks.

The Bigger Security Ecosystem Problem

Whisper Pair is one vulnerability affecting one protocol on one category of devices. But it points to a larger problem in how we handle security for consumer IoT devices.

Consumer electronics manufacturers were never primarily security companies. They're good at designing hardware, optimizing for cost, manufacturing at scale. Security is often an afterthought. Firmware is frequently written with minimal security review. Updates are often treated as expensive engineering burdens.

Meanwhile, consumer expectations are that devices "just work" and don't require ongoing maintenance. People don't want to think about security. They want to buy something, use it, and have it be safe. That's a reasonable expectation, but the industry hasn't risen to meet it.

There's also a liability gap. If someone buys insecure earbuds and gets eavesdropped on, who's liable? The manufacturer who built it insecurely? The company that certified it? The wireless carrier? The user for not updating? Legally, it's often unclear. Because liability is unclear, there's not as much economic incentive to fix the problem.

Regulation could help, but regulations in this space are still being figured out. The EU has been more aggressive about requiring security standards and extended support periods. The US has been slower. Global standards for IoT device security don't really exist yet.

What would actually help is if there were binding standards that devices had to meet. "All audio devices with microphones must support security updates for at least 3 years." "All devices using Bluetooth pairing must pass at least these security tests." "Manufacturers must disclose known vulnerabilities within 60 days." Simple rules like that would incentivize better security.

But the industry will resist because compliance costs money. And politicians don't always prioritize security regulation. So we're stuck in a situation where security is often suboptimal because nobody has enough incentive to make it better.

Expert Perspective: What Security Researchers Are Saying

The researchers at KU Leuven who discovered Whisper Pair have been fairly vocal about the broader implications.

Their main concern, which they've emphasized repeatedly, is that the vulnerability will likely remain present in millions of devices indefinitely because most users will never update their firmware. The technical fix is available. Manufacturers can implement it. But deployment is the problem.

They've also been critical of the certification process. They've asked why devices passed certification when they have such obvious implementation flaws. They've suggested that more thorough security testing during certification would have caught this.

They've pointed out that the attack is practical and reproducible. This isn't theoretical. A determined attacker with modest technical skills could execute this attack. It's not like some obscure zero-day that requires a PhD to exploit.

They've also emphasized that users are essentially powerless to protect themselves. You can't prevent an attacker from trying Whisper Pair. You can't know if you've been compromised. Your only real protection is hoping your manufacturer releases a patch and hoping you install it. That's a weak security posture.

Other security researchers have noted that Bluetooth vulnerabilities in general tend to be problematic because Bluetooth is supposed to be low power and simple. Adding more security checks requires more power and more complexity. There's a fundamental tension between Bluetooth's design goals and strong security.

The consensus among experts is that this is fixable, but it requires commitment from manufacturers, better certification processes, and realistic expectations about updating devices throughout their lifecycle. None of those things are guaranteed.

FAQ

What is the Whisper Pair vulnerability?

Whisper Pair is a security flaw in Google's Fast Pair protocol affecting 17 audio device models. It allows attackers within Bluetooth range to hijack your headphones or speakers without your knowledge, enabling them to eavesdrop, inject audio, and track your location. The vulnerability affects devices from Sony, Jabra, JBL, Marshall, Xiaomi, Nothing, One Plus, Soundcore, Logitech, and Google itself.

How does Whisper Pair actually work?

An attacker within Bluetooth range initiates a pairing request to a vulnerable device. Because the device firmware doesn't properly validate whether pairing mode is enabled, it responds to the request. The attacker's device then impersonates legitimate Fast Pair hardware during the authentication handshake. The vulnerable device fails to properly verify the cryptographic attestation, allowing the pairing to complete. Once paired, the attacker can control the device's microphone, inject audio, and potentially track the device's location through Find Hub.

Which audio devices are vulnerable to Whisper Pair?

The confirmed vulnerable devices include models from Sony, Jabra, JBL, Marshall, Xiaomi, Nothing, One Plus, Soundcore, Logitech, and Google. The researchers identified 17 specific models across these 10 manufacturers. You can check if your specific device is vulnerable using the searchable tool they created, which is available online. Google's Pixel Buds have already been patched, but many devices from other manufacturers remain vulnerable pending manufacturer updates.

How can I tell if my device is vulnerable?

You can look up your specific device model in the searchable tool that the KU Leuven researchers provided. Find your device's exact model number (usually in the product manual or settings), then check the tool's database. If your device is listed, it's potentially vulnerable. You can also check your device's current firmware version and compare it to the latest version available from the manufacturer to see if updates exist.

What can attackers do with Whisper Pair?

Attackers can enable your device's microphone to listen to ambient sound around you. They can inject audio directly into your earbuds or speakers. They can use Google's Find Hub service to track your device's location, effectively tracking you. They can also modify audio playback or silence important alerts. The attack requires only that the attacker be within Bluetooth range for approximately 15 seconds to establish the initial pairing.

How do I protect myself from Whisper Pair?

Install firmware updates for your audio devices as soon as they're available from the manufacturer. Check your device's current firmware version and the latest available version. Keep your phone's operating system updated. Regularly review paired Bluetooth devices and remove anything unrecognized. Disable Bluetooth when you're not using it. For sensitive situations, consider using wired headphones instead. You can also limit your use of vulnerable devices while you're waiting for patches.

Has Google fixed this vulnerability?

Google has released patches for its own Pixel Buds and has worked with manufacturers to provide fixes. However, getting patches deployed to the 17 vulnerable device models is an ongoing process. Some manufacturers have released patches, but others are still investigating or haven't issued updates. Google has also updated its Fast Pair Validator certification tool and tightened certification requirements for future devices.

What's Google doing to prevent this from happening again?

Google updated its Fast Pair Validator tool to test for Whisper Pair-type vulnerabilities. They tightened certification requirements for new devices. They're requiring more thorough security testing during the certification process. However, these changes only apply to future devices. The billions of devices already on the market remain vulnerable unless manufacturers release firmware patches.

Why don't manufacturers just push automatic updates?

Manufacturers often don't push automatic firmware updates because the process is technically complex and expensive. Firmware updates require extensive testing, quality assurance, and support infrastructure. Manufacturers also worry about bricking devices or causing unexpected issues. Many manufacturers, especially those making low-margin consumer products, don't have the resources to support automatic updates indefinitely. This leaves most users stuck with vulnerable devices that never get updated.

How is Whisper Pair different from other Bluetooth vulnerabilities?

Whisper Pair is notable for affecting multiple manufacturers simultaneously, being relatively easy to execute compared to other Bluetooth attacks, and not requiring specialized equipment. Previous Bluetooth vulnerabilities often required either physical access to devices or specialized knowledge. Whisper Pair just requires proximity and a few seconds. It also gives attackers multiple capabilities simultaneously including eavesdropping, audio injection, and location tracking.

Conclusion: Moving Forward with Better Security Practices

The Whisper Pair vulnerability reveals deep structural problems in how consumer audio devices are designed, tested, and maintained. It's not just a bug that needs fixing. It's a symptom of an industry that prioritizes convenience and cost over security, that relies on manufacturers to self-police, and that leaves users vulnerable to attacks they can't detect or prevent.

The technical aspects are fixable. Google can improve its certification process. Manufacturers can implement more secure firmware. Devices can be patched. But the systemic problem—getting updates deployed to millions of devices in the field—is much harder to solve.

In the short term, users need to be proactive. Check if your devices are vulnerable. Install any available updates. Stay aware of your Bluetooth devices and remove anything unfamiliar. For sensitive situations, revert to wired alternatives. These aren't perfect solutions, but they reduce your exposure.

In the medium term, manufacturers need to commit to longer support periods for security updates. They need to make the update process easier and more transparent. They need to invest in firmware security from the beginning rather than treating it as an afterthought.

In the long term, the industry needs better standards. Regulation might be necessary. The EU is moving in that direction with their Digital Products Act, which includes security requirements for consumer electronics. The US is likely to follow eventually. But waiting for regulation is slow.

What would actually help is if Google used its leverage in the ecosystem to set higher standards. If manufacturers want their devices to use Fast Pair and get the associated certification benefits, they should have to commit to security updates for at least three to five years. They should have to make updating easy. They should have to communicate vulnerabilities transparently.

Until then, Whisper Pair will remain a threat to millions of users, most of whom have no idea their devices are vulnerable and no practical way to protect themselves. That's an uncomfortable reality in our increasingly connected world. We're buying devices that stay connected through their entire lifetime, but the security infrastructure to support that isn't in place.

The good news is that we know how to fix this. We have the technical knowledge. We understand the problem. The barriers are economic and organizational, not technical. Manufacturers could fix this if they made it a priority. Google could enforce better standards if it wanted to. Users could stay safer if they were more vigilant about updates.

Whether the industry will actually rise to the challenge remains to be seen. For now, check if your devices are vulnerable, install any available patches, and be aware of the Bluetooth devices around you. It's not perfect security, but it's better than assuming everything is fine.

Key Takeaways

- WhisperPair vulnerability in Google Fast Pair affects 17 audio device models from 10 manufacturers including Sony, Google, Logitech, and JBL

- Attackers within Bluetooth range can hijack earbuds in under 15 seconds with only device model number, enabling eavesdropping and location tracking

- Root cause is improper implementation of Fast Pair protocol by manufacturers, not a flaw in the protocol itself

- Most vulnerable devices will remain unpatched because users don't know updates exist or can't complete the complex update process

- Users can protect themselves by installing available firmware updates, disabling Bluetooth when not in use, and using wired alternatives for sensitive situations

Related Articles

- Copilot Security Breach: How a Single Click Enabled Data Theft [2025]

- LinkedIn Comment Phishing: How to Spot and Stop Malware Scams [2025]

- Telegram Links Can Dox You: VPN Bypass Exploit Explained [2025]

- Hackers Targeting LLM Services Through Misconfigured Proxies [2025]

- D-Link DSL Gateway CVE-2026-0625 Critical Flaw: RCE Risk [2025]

- Most Dangerous People on the Internet [2025]

![Google Fast Pair Security Flaw: WhisperPair Vulnerability Explained [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/google-fast-pair-security-flaw-whisperpair-vulnerability-exp/image-1-1768507722266.png)