How 2150's €210M Fund Is Reshaping Climate Tech for Urban Carbon Solutions

Cities are broken. Not in the way that makes headlines, but in a way that costs the world trillions. They consume 80% of global GDP yet generate 70% of emissions. They're the machine that powers prosperity, but also the machine that's burning the house down.

This is where 2150 comes in. The European venture capital firm just closed a €210 million second fund—and they're not trying to save the world. They're trying to save cities.

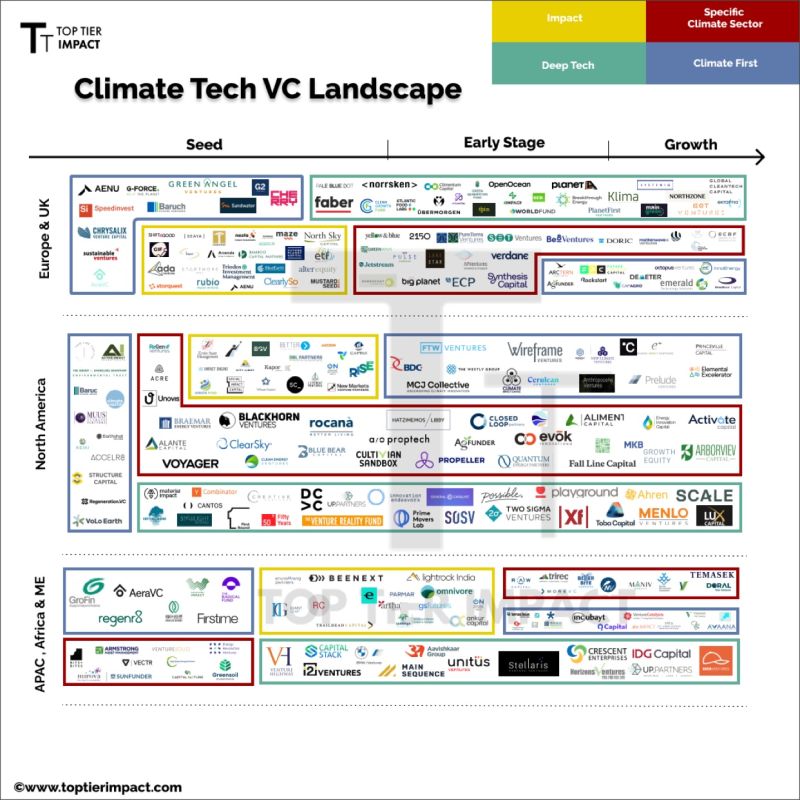

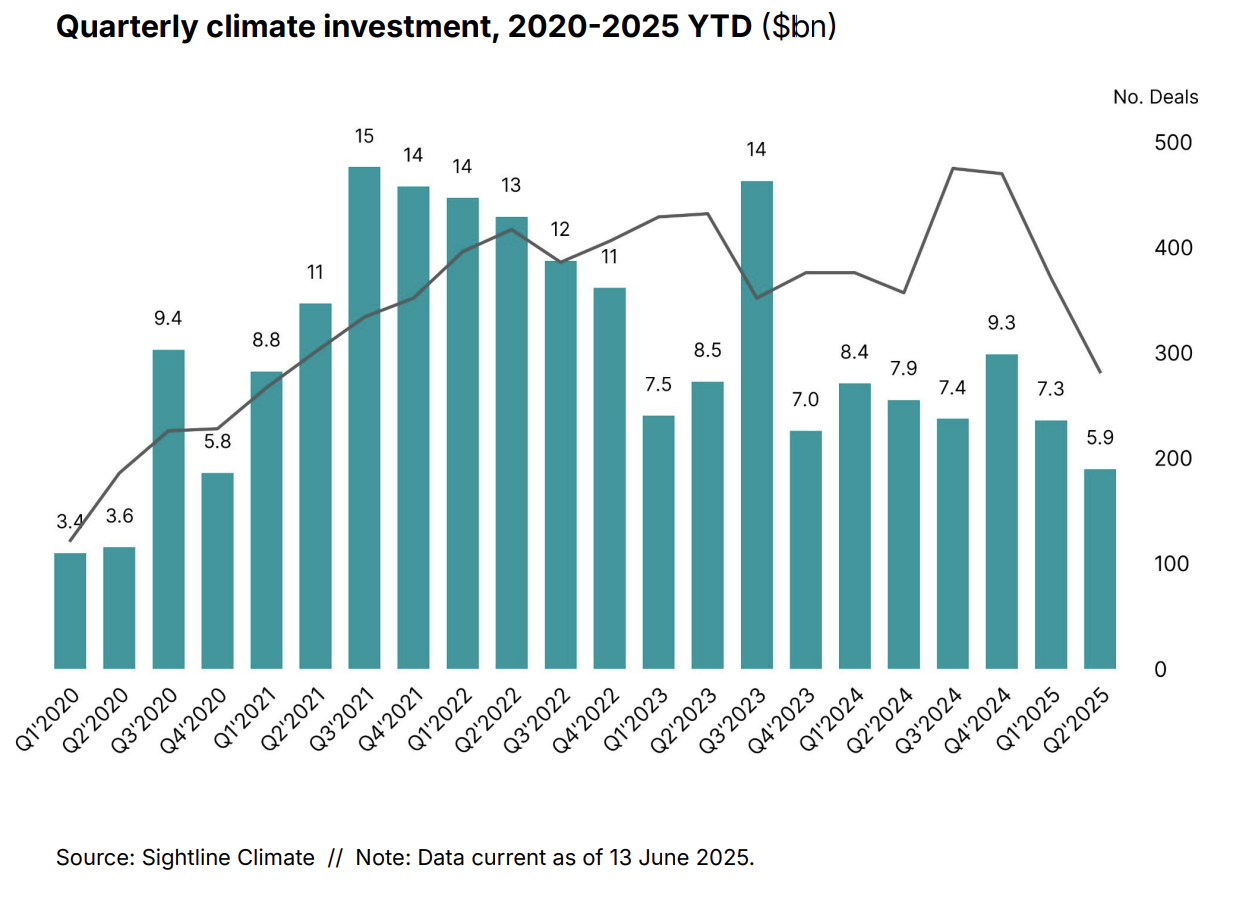

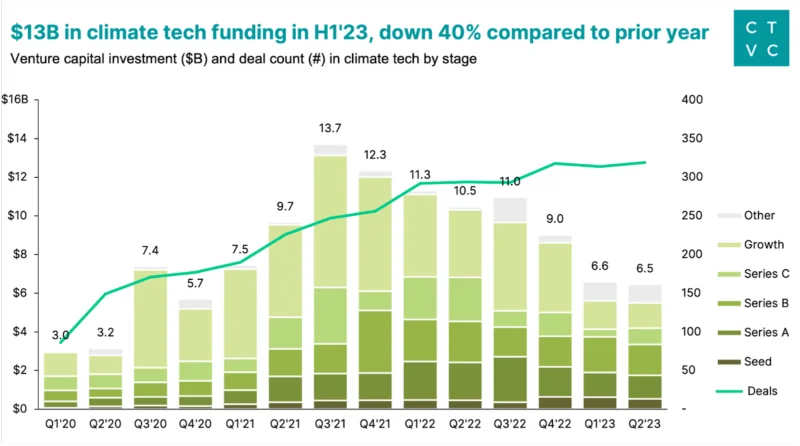

If you've been paying attention to climate tech funding, you know it's gotten weird. Billions are flowing into everything from carbon capture to synthetic proteins to direct air removal technology. Some of it works. Most of it doesn't. The problem is that venture capital, by nature, chases scale. But climate solutions don't always scale the way a software company scales. Industrial heat pumps don't go viral. E-waste recycling doesn't have network effects.

What 2150 figured out is that cities aren't just the problem—they're the constraint. If you can solve something within the urban system, you've got a real business. You've got margins. You've got customers who actually care about return on investment, not just carbon offsets.

This shift in thinking has attracted serious institutional capital. The new fund includes backing from the Danish sovereign fund EIFO, Church Pension Group, Novo Holdings, and Viessmann Generations Group. Thirty-four limited partners in total. These aren't climate evangelists writing checks to feel good. These are institutional investors betting that climate + better business fundamentals equals real returns.

Let's break down what's actually happening here, why it matters, and what it means for the future of climate tech investment.

The Urban Climate Paradox: Why Cities Are Ground Zero for Carbon Solutions

Jacob Bro, co-founder of 2150, uses a metaphor that sticks with you. He calls cities a "beautiful vampire squid that sucks in all the resources." It's not flattering, but it's accurate. Cities concentrate everything: wealth, people, infrastructure, consumption, and yes, emissions.

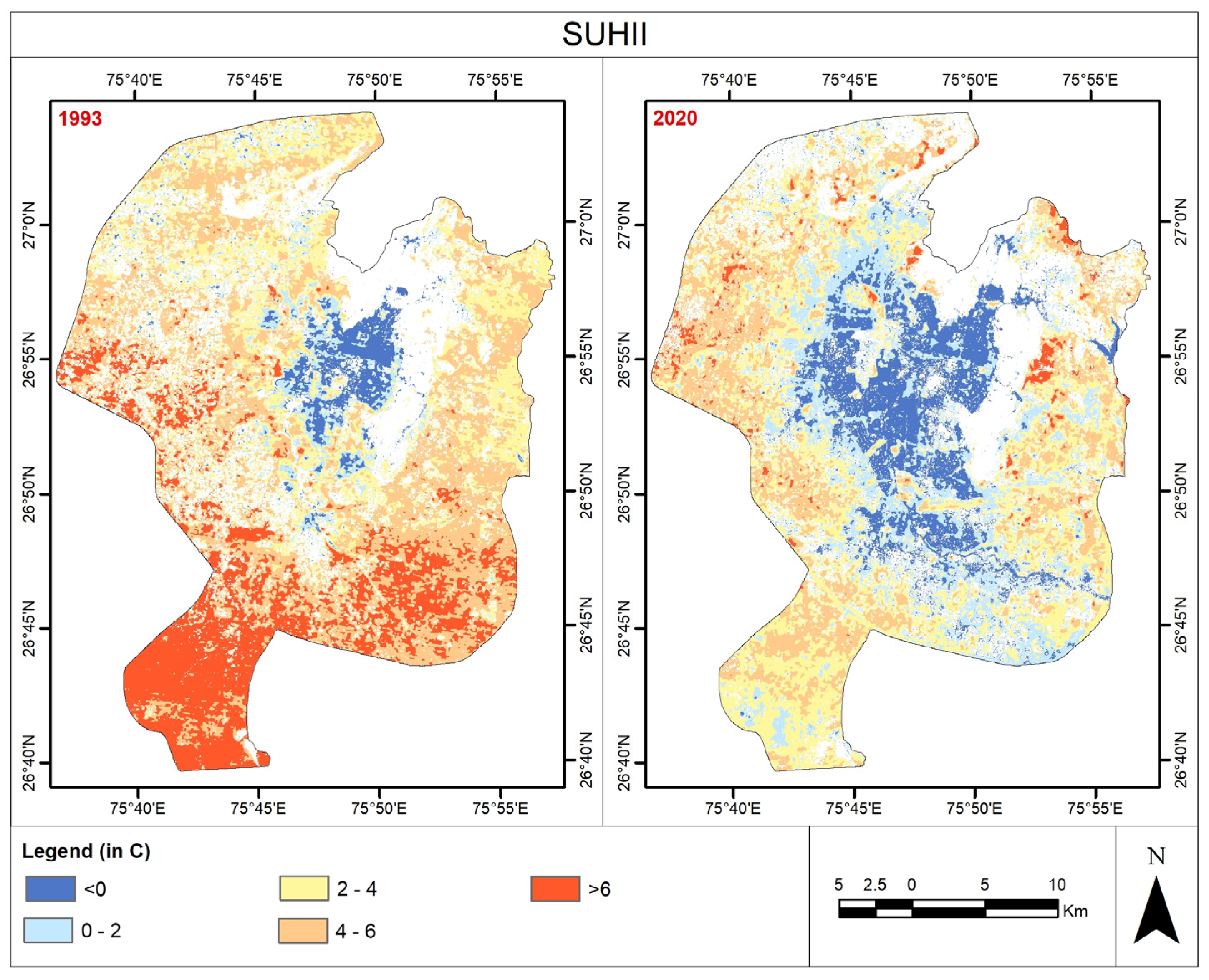

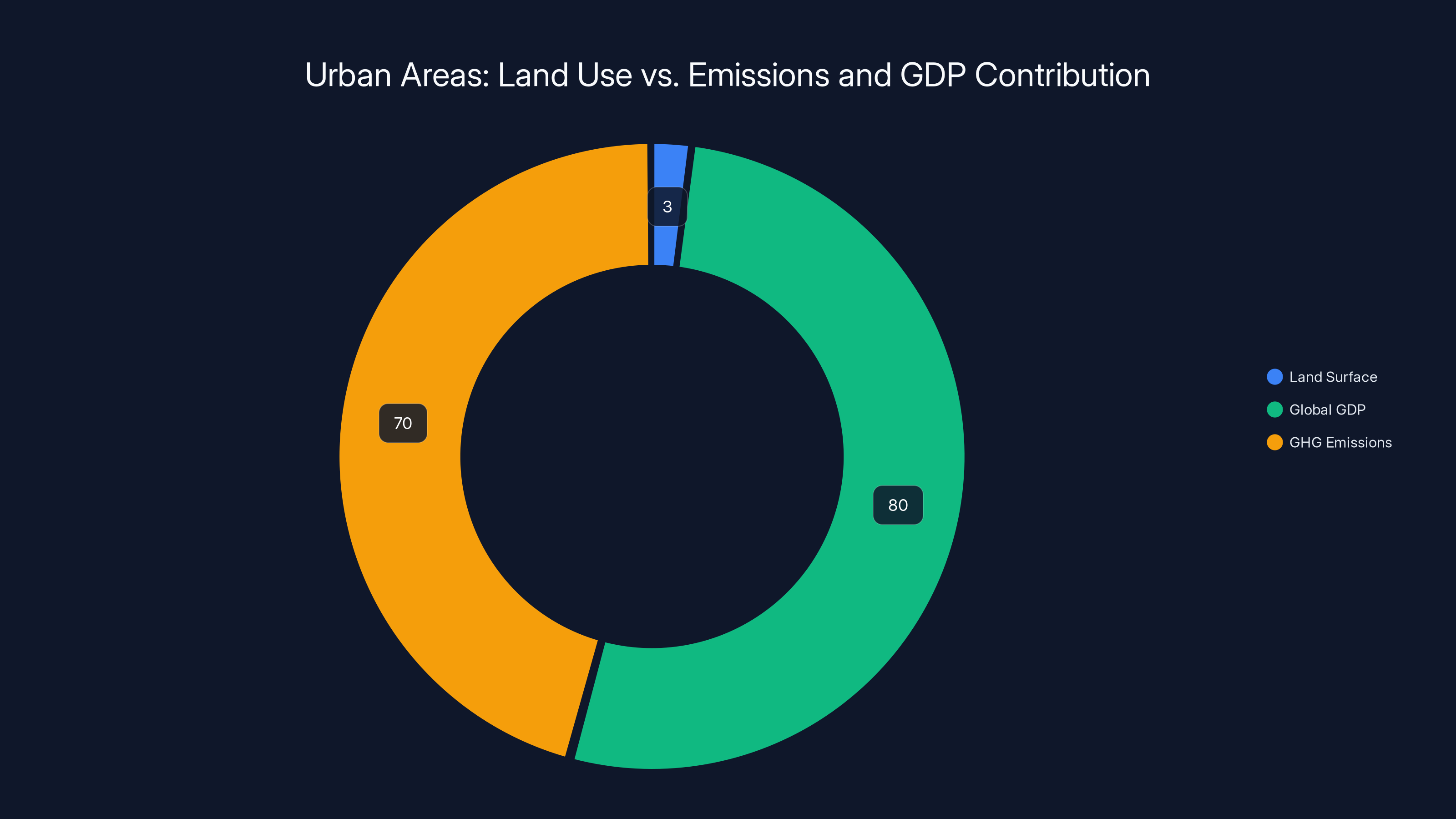

Here's the math that matters. Cities cover about 3% of Earth's land surface. Yet they generate roughly 80% of global GDP and are responsible for approximately 70% of global greenhouse gas emissions. That concentration is actually useful for climate tech investors. It means problems are dense. They're clustered in places where infrastructure already exists, where regulation might apply, where money flows.

Consider what a city needs to function. Energy systems. Transportation networks. Building heating and cooling. Water treatment. Waste management. Food supply chains. Manufacturing. Every single one of these systems has emissions attached to it. Every single one also has cost structures that make climate tech viable if done right.

This is the insight that separates 2150 from climate funds that cast wider nets. They're not looking for technologies that solve climate change in the abstract. They're looking for technologies that solve specific problems within the urban system that happen to have climate benefits attached.

The distinction matters because it changes what gets funded. Instead of betting on speculative carbon removal technology that might work at scale in 2040, you're funding heat pumps that replace fossil fuel heating systems today. Instead of betting on theoretical industrial processes, you're funding companies that recycle scrap metals and electronics because those waste streams already exist and need solutions.

Urban areas also generate the data that makes climate tech work better. You can measure emissions, track consumption patterns, monitor energy flow, and adjust in real time. Rural climate solutions often lack that feedback loop. Cities are measurable. Cities are investable.

Bro and Christian Hernandez, the other co-founder, spent years identifying these bottlenecks before raising their first fund. They weren't looking for technology that might exist someday. They were looking at what cities actually consume, what they actually spend money on, and where inefficiency creates opportunity.

The result is that 2150's portfolio doesn't feel like a climate fund. It feels like an urban infrastructure fund that happens to reduce carbon. Atmos Zero makes industrial heat pumps. Get Mobil recycles electronic waste. Metycle operates a metals marketplace. Mission Zero captures carbon directly. These are businesses with revenue potential, unit economics that work, and markets that exist today.

2150's investment strategy is diversified across sectors, with a balanced focus on industrial heat pumps, electronic waste recycling, scrap metals marketplaces, and direct air capture technologies. (Estimated data)

The €210 Million Second Fund: What Changed, What Stays the Same

The first fund was €290 million. The second fund is €210 million. On the surface, that looks like a decline. It's not. It's actually a statement about how capital flows work in climate tech.

2150 raised their first fund because nobody else was doing what they were doing. They had a thesis—cities are the constraint, urban problems are solvable, climate is a feature not a bug—and they were willing to bet institutional capital on it. That fund closed around 2020-2021, during the height of climate tech enthusiasm. Every climate fund was raising massive second funds. The space felt hot.

Second funds in venture capital are always harder. You've got performance metrics to hit. You've got a track record to defend. You've got limited partners asking harder questions. A smaller fund size often reflects discipline, not weakness. It suggests the team is getting picky about what they invest in.

Hernandez emphasized that the new fund would focus on quality over quantity. They're planning to invest in 20 companies total from the €210 million fund. That's roughly €10.5 million per company on average, with checks ranging from €5 million to €6 million. Half the fund is reserved for follow-on investments in successful portfolio companies. The other half gets deployed across new investments.

What's remarkable is that the LP base remained strong and arguably got more sophisticated. The fund includes EIFO (the Danish sovereign wealth fund), Church Pension Group (which manages over $13 billion in assets), and Novo Holdings (which has stakes in pharmaceutical and biotech companies). These aren't venture capital firms. These are institutional capital holders who typically deploy money in bonds, public equities, or real estate. Their presence in a climate tech fund suggests the investment case has become more concrete.

Viessmann Generations Group is particularly interesting. Viessmann is one of the world's largest heating and cooling technology companies. They've been around for over 150 years. Their investment in 2150 isn't ideology. It's strategic. They see the future of heating systems as something that needs to change radically, and they're hedging their traditional business by backing startups that might disrupt it.

The fund targets bring total assets under management to €500 million. That's meaningful scale for a regional fund. It allows them to take bigger positions, support portfolio companies through multiple funding rounds, and actually impact the ecosystems they invest in.

One detail that matters: 2150 has already mitigated one megaton of carbon emissions from their portfolio in a single year. For context, that's roughly equivalent to removing 200,000 cars from the road for a year. From a four-year-old fund. That's not trivial, and it's exactly the kind of metric that gets institutional capital interested.

The €210 million second fund is equally split between new investments and follow-on investments, reflecting a balanced approach to nurturing existing portfolio companies while exploring new opportunities.

Beyond Carbon: Why Industrial Automation Is the Real Climate Opportunity

Here's where 2150's thesis gets interesting. They're excited about data centers and industrial automation. That excitement isn't about climate change at all. It's about Europe's demographic crisis.

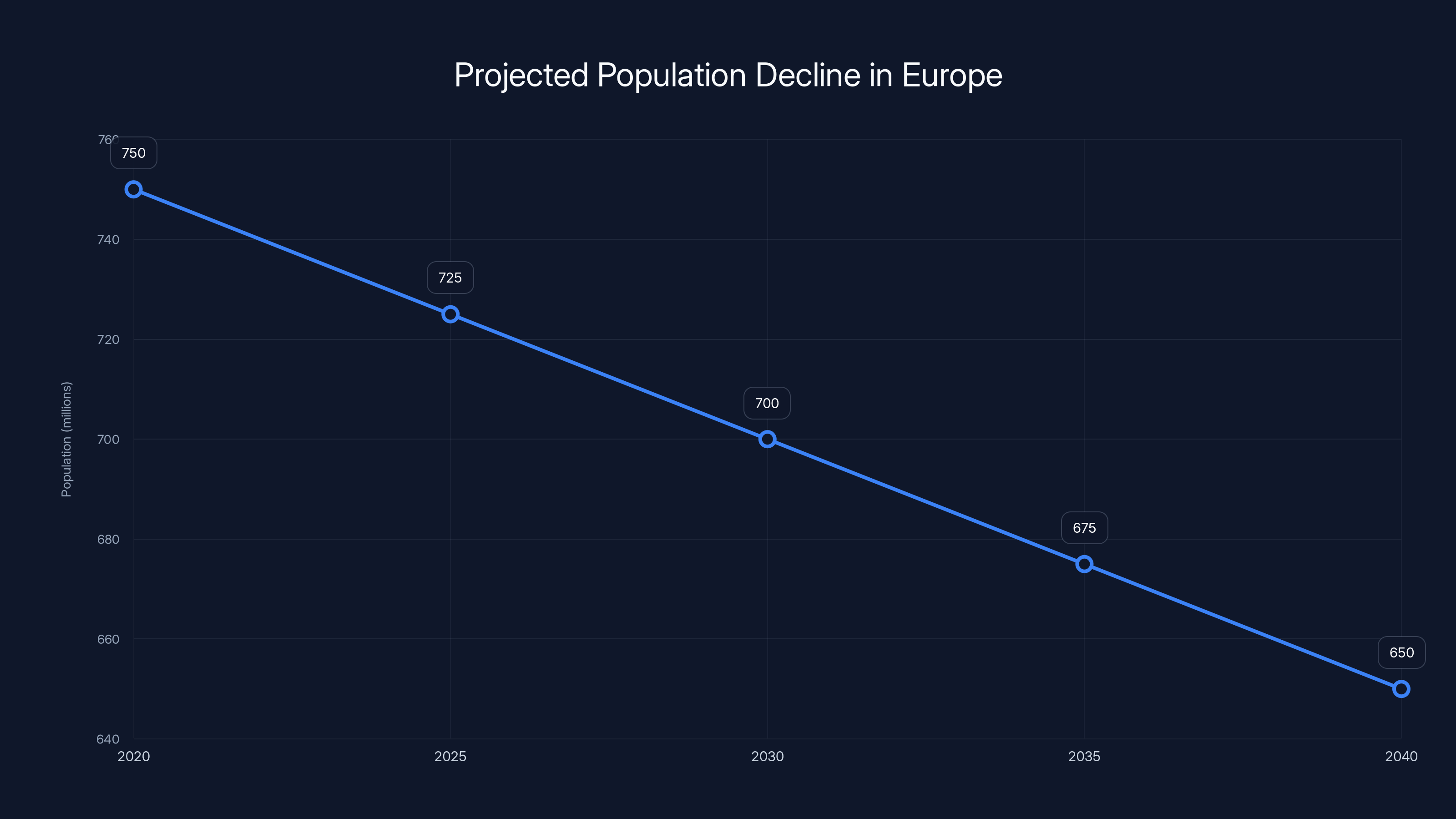

Europe is aging fast. The continent is expected to lose 100 million people by 2040. That's not growth—that's contraction. The Netherlands already has over 50% of its population over 50 years old. These are countries with fully developed infrastructure, high labor costs, and aging workforces that can't be replaced by hiring more people.

What do you do when you can't hire more people? You automate. You build robots. You optimize processes. You make existing workers vastly more productive. And if you're going to industrialize around automation, you might as well do it with technologies that happen to be more efficient, require less energy, and reduce emissions.

This is where the climate component actually becomes elegant. The business case for industrial automation in Europe isn't climate. It's survival. But when you automate, you almost always reduce energy intensity. You run plants more efficiently. You cut waste. The climate benefit is almost automatic.

Hernandez explained it clearly: "Europe is expected to lose 100 million people between now and 2040. So what role does industrial automation help with helping those people be productive, but also generating GDP and funding those people's pensions?"

That's not climate ideology. That's economics. And that's exactly why institutional capital is flowing into funds like 2150. They've identified a real problem—demographic decline and labor shortages—and they're backing technology companies that solve it in ways that also happen to be environmentally beneficial.

AI is catalyzing this shift. Data centers need massive amounts of energy, which makes them climate-critical. Industrial automation driven by AI requires significant capital investment, which makes them venture-scale. The timing is right for funds that understand both the AI opportunity and the climate constraints.

2150 sees this clearly. They're not backing AI companies that claim to solve climate. They're backing industrial companies using AI to become more efficient, which in turn reduces their carbon footprint.

The Portfolio: Real Companies Solving Real Urban Problems

Let's look at what 2150 is actually funding, because this is where the thesis becomes concrete.

Atmos Zero makes industrial heat pumps. This is boring technology. Pump technology has existed for decades. But industrial facilities currently heat water and steam using fossil fuels. Switching to heat pump technology cuts energy consumption dramatically while also reducing emissions. The market exists. Companies are desperate for solutions because heating costs are rising. It's a problem you can sell to a CFO, not a sustainability officer.

Get Mobil recycles electronic waste. E-waste is one of the fastest-growing waste streams in the world. Every year, humans generate roughly 57 million metric tons of electronic waste. Most of it ends up in landfills or gets shipped to countries with minimal environmental regulations. But if you can extract valuable materials from that waste—copper, gold, rare earth elements—you've got a business. Get Mobil isn't a charity. They're extracting value that currently gets thrown away.

Metycle operates a marketplace for scrap and recyclable metals. Same logic. Metals are expensive. Companies that use metals want to buy recycled content because it's cheaper than virgin material. A marketplace that connects suppliers of scrap metals to industrial buyers solves a real market inefficiency. It also happens to reduce mining pressure and lower carbon intensity compared to virgin metal production.

Mission Zero does direct air capture—removing CO2 directly from the atmosphere. This is harder to justify on pure economics, but it's worth noting because it shows 2150 isn't dogmatic. They're willing to fund speculative technology if the business case starts to work. Mission Zero is building a company around direct air capture, which requires massive amounts of energy but also creates potential business models around selling captured carbon or utilizing it in industrial processes.

Three additional portfolio companies remain unnamed, but the pattern is clear. 2150 funds companies solving urban infrastructure problems that have climate benefits and viable business models.

They're planning to invest in 20 companies total from the second fund. They've already deployed capital into seven. That suggests they're selective and potentially already experiencing higher rejection rates or longer due diligence cycles than typical venture funds.

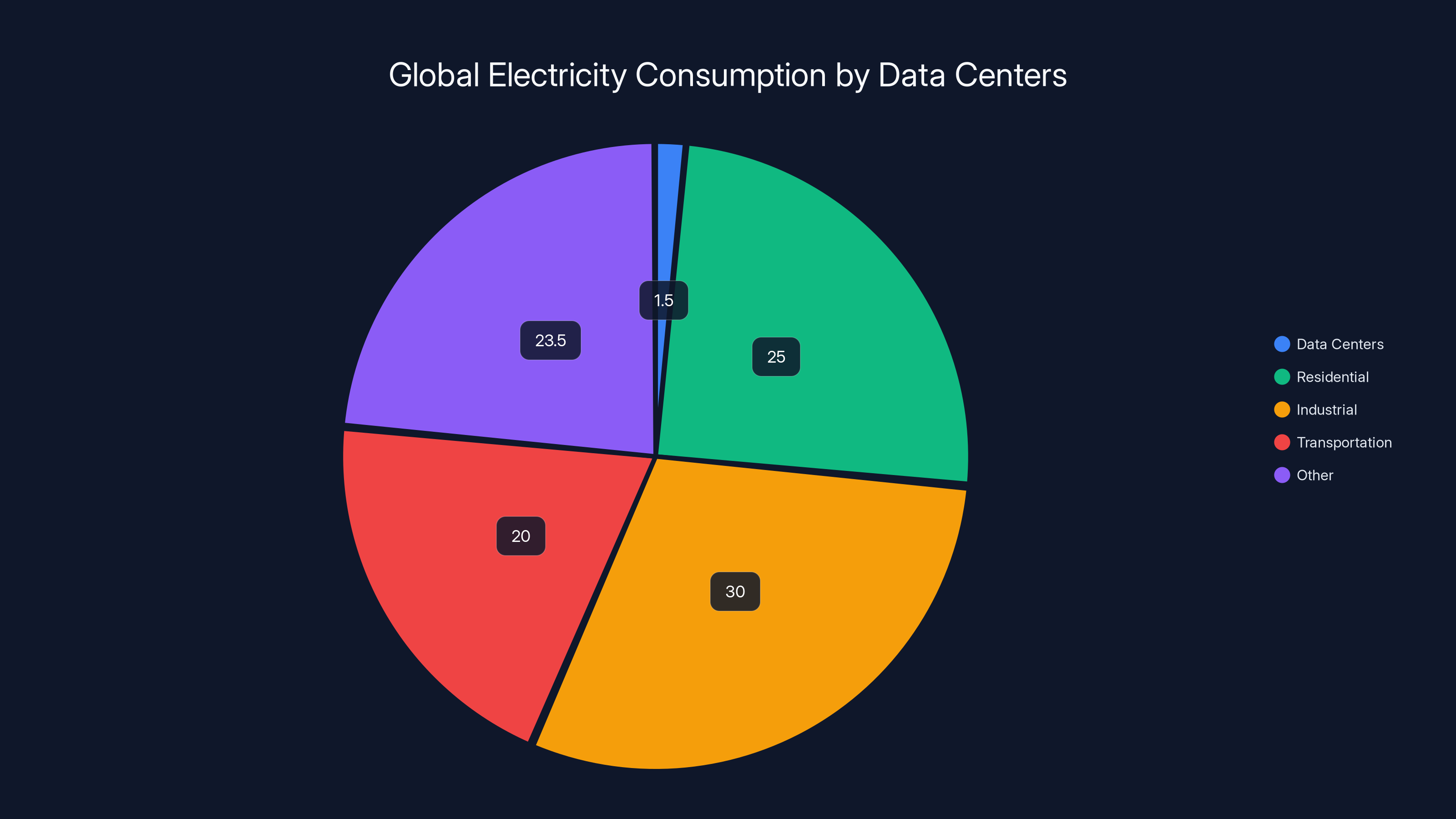

Data centers consume an estimated 1.5% of global electricity, a figure expected to rise due to AI demands. Estimated data.

The Investment Thesis: Sustainability as Better Business

Bro articulated the core thesis in one sentence: "Sustainability, if done well, is just better business. It's cheaper, faster, and more independent from geopolitics."

This is a departure from how climate tech is typically funded. Most climate venture funds frame their investments as fighting climate change. They measure success partly by carbon reduction. They're comfortable with investments that don't make traditional venture returns if the climate impact is big enough.

2150 rejects that framing. They want both. They want companies that happen to be more climate-friendly because they're more efficient, not despite being unprofitable. They want technologies that are cheaper to implement than the alternatives they're replacing. They want companies that reduce geopolitical dependence, not increase it.

This shapes everything they fund. It means no speculative technology that might work in 2050. It means no betting on government subsidies as a core business model. It means companies that could thrive even if climate regulations disappeared tomorrow.

The geopolitics piece is particularly important. Europe depends on fossil fuel imports from politically unstable regions. It also has labor cost and environmental regulations that make it harder to compete on pure cost. But it has capital, technical expertise, and regulatory certainty. Climate tech that reduces resource dependence while increasing efficiency plays to European strengths.

Heat pumps reduce natural gas imports from Russia. Electric vehicles reduce oil imports from the Middle East. Industrial efficiency reduces overall energy imports. These aren't just environmental wins. They're strategic wins for Europe as a region.

That's why institutional investors like sovereign wealth funds and large pension funds are comfortable writing checks. The climate tech narrative appeals to their stakeholders. But the underlying thesis is about building better businesses that happen to be more sustainable.

Urban Density as Venture Capital Advantage

Here's a strategic insight that most climate funds miss. Urban density is a venture capital advantage, not a limitation.

Rural climate solutions—regenerative agriculture, land restoration, forest management—are genuinely important for addressing climate change. But they're hard to scale as venture capital plays. The unit economics don't work. You can't raise Series B funding for a soil carbon program. The margins are too thin. The exit opportunities are limited.

Urban climate solutions are different. Cities have concentrated infrastructure. They have multiple stakeholders competing for efficiency. They have dense customer bases where one sale can be replicated across hundreds of similar buildings or facilities. A heat pump solution that works in Berlin can be implemented in Frankfurt, Munich, Hamburg. Network effects exist, even if they're not software-style network effects.

The urban focus also means 2150 portfolio companies benefit from data. When you're operating in a city, you can measure everything. You can see where energy is flowing. You can identify inefficiencies. You can test solutions and measure impact. Rural climate tech often operates blind until the outcome is measured years later.

Data also enables faster iteration. If your heat pump installation cuts energy usage by 30% instead of the expected 40%, you can see that immediately and adjust your product. If your recycling operation recovers 5% less material than modeled, you'll know within weeks. This feedback loop accelerates learning and improves odds of success.

The urban focus also creates defensibility. Once a startup has installed industrial heat pumps in 50 facilities across a region, they've built relationships, they've got data on performance, they've trained technicians. Competitors can't just copy that. They have to build their own network from scratch.

This is why 2150's thesis—start with cities, look at their resource flows, identify bottlenecks—actually works better than the broader climate tech approach. You're looking for places where inefficiency is both expensive and visible. You're looking for problems where there's strong motivation to solve them right now, not someday.

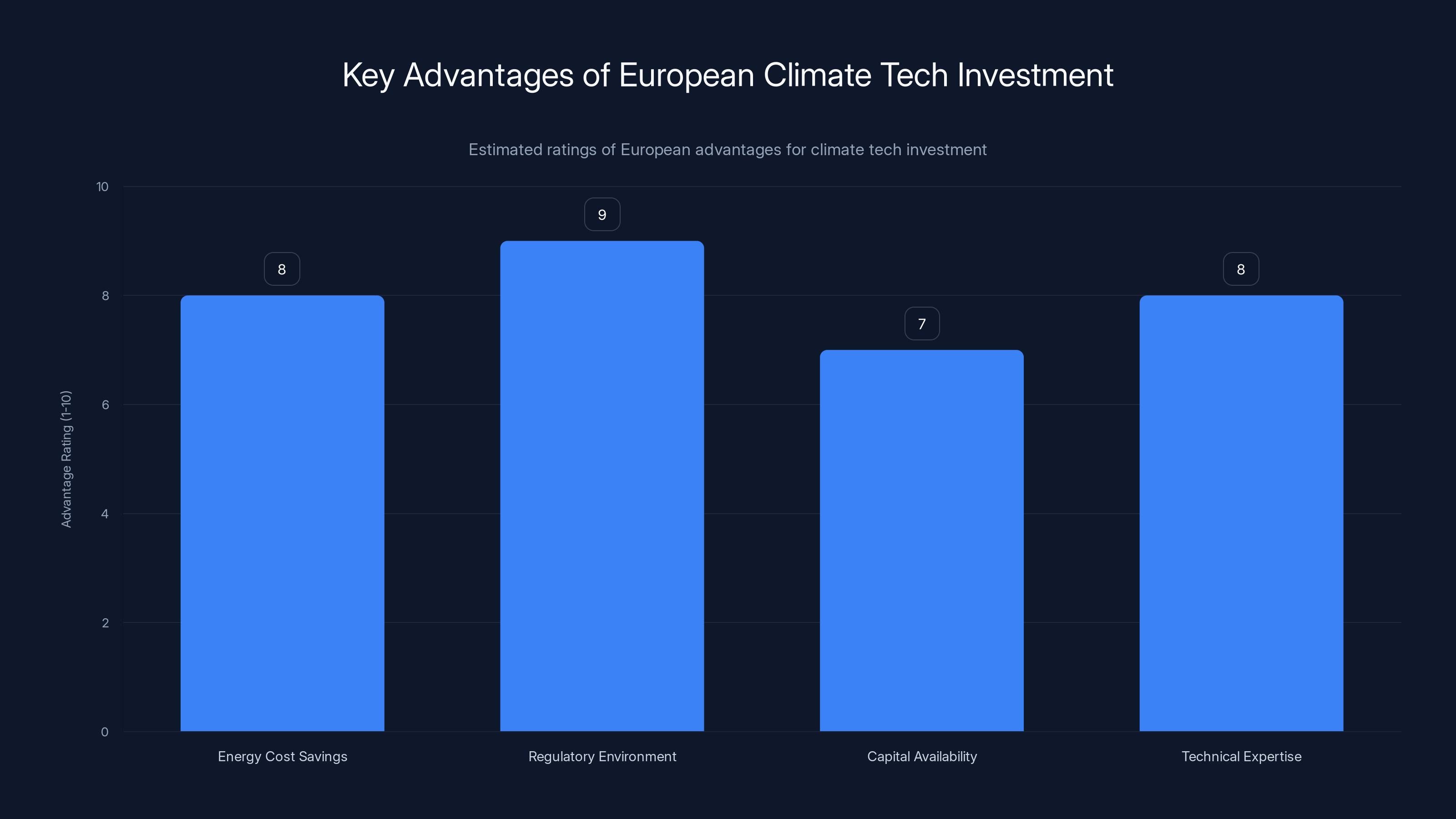

Europe offers significant advantages for climate tech investment, particularly in regulatory environment and energy cost savings. (Estimated data)

The Second-Fund Challenge: Deploying Capital in a Changing Climate Tech Landscape

Second funds are always harder. First funds can be exploratory. You're testing a thesis. You're building relationships. You're making mistakes with other people's money that nobody's really tracking closely because the asset class is new.

Second funds have to prove the thesis. The market is now watching. Limited partners are watching. Competitors are watching. If your first fund underperformed, you won't raise a second fund, period. If your first fund did well, expectations reset. The second fund has to do as well or better, even though the market conditions have changed and the thesis is now known to competitors.

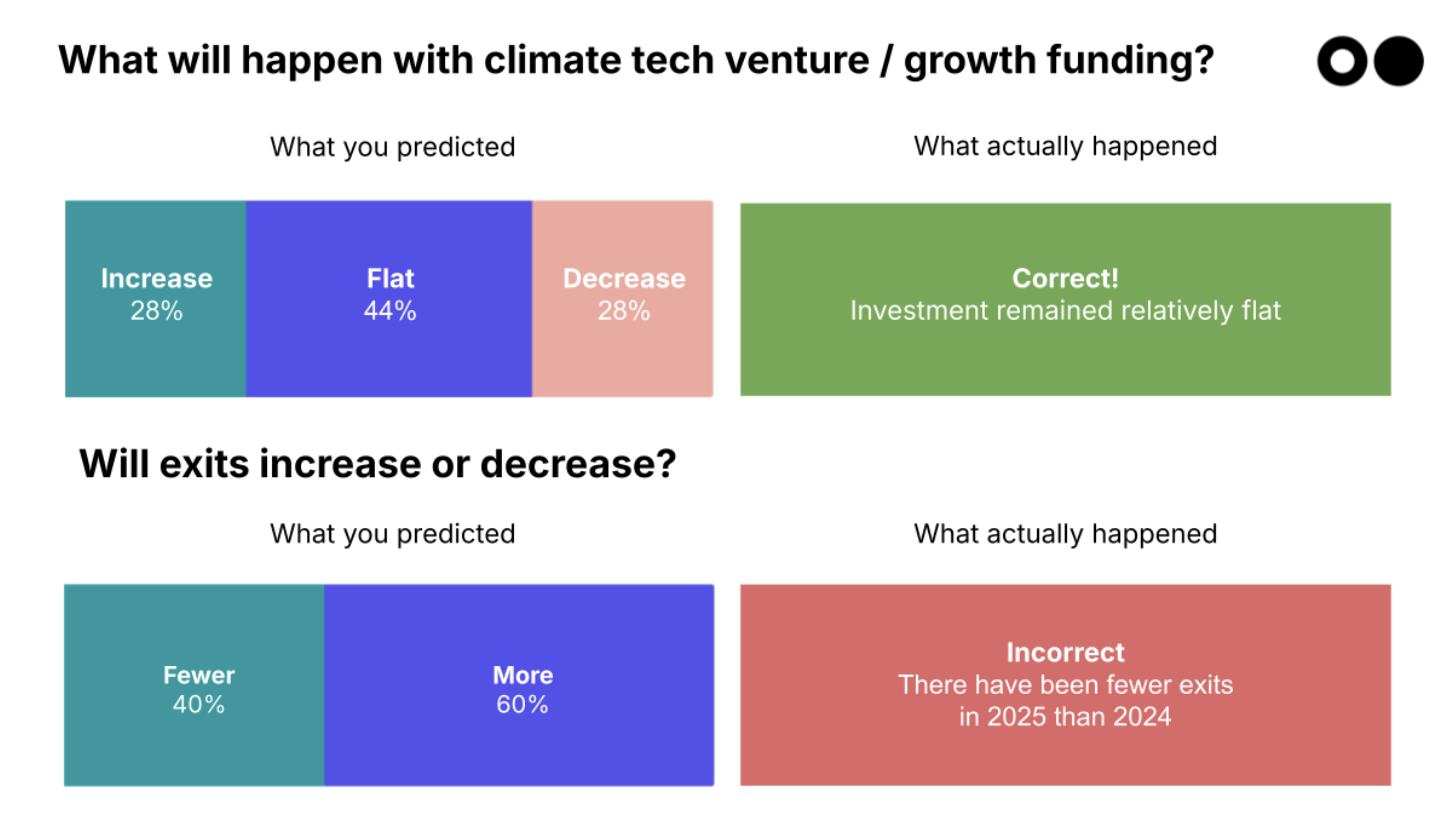

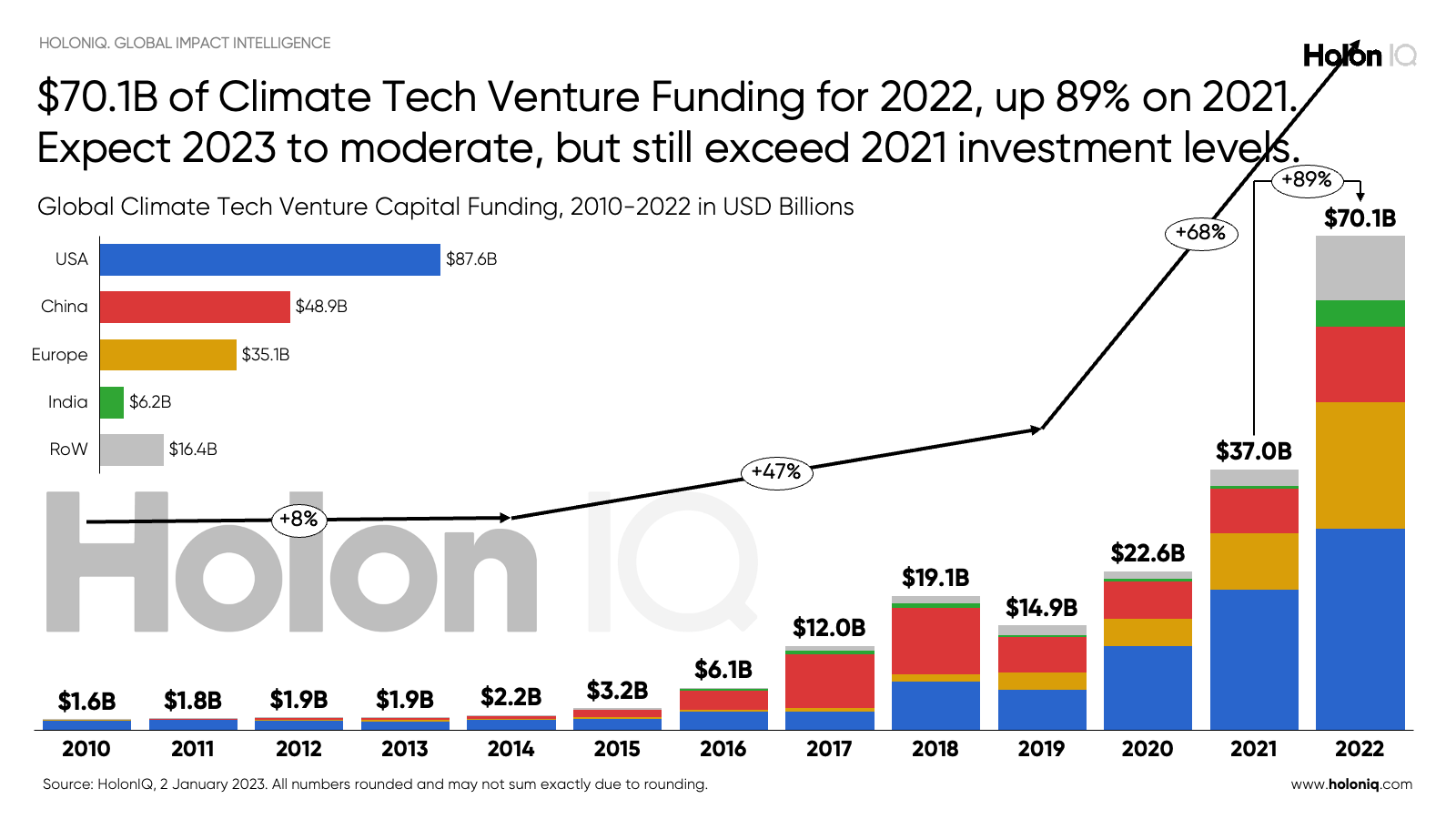

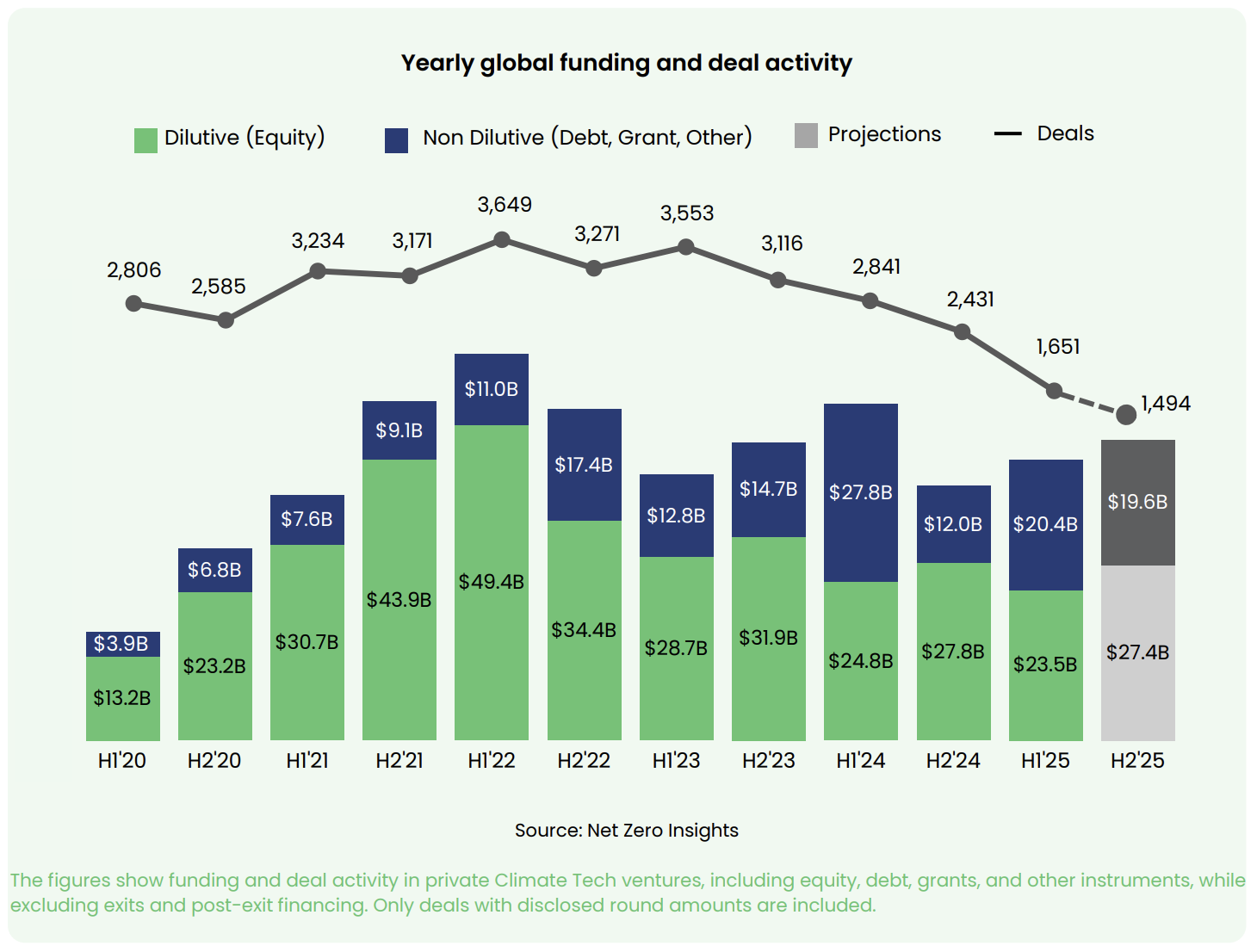

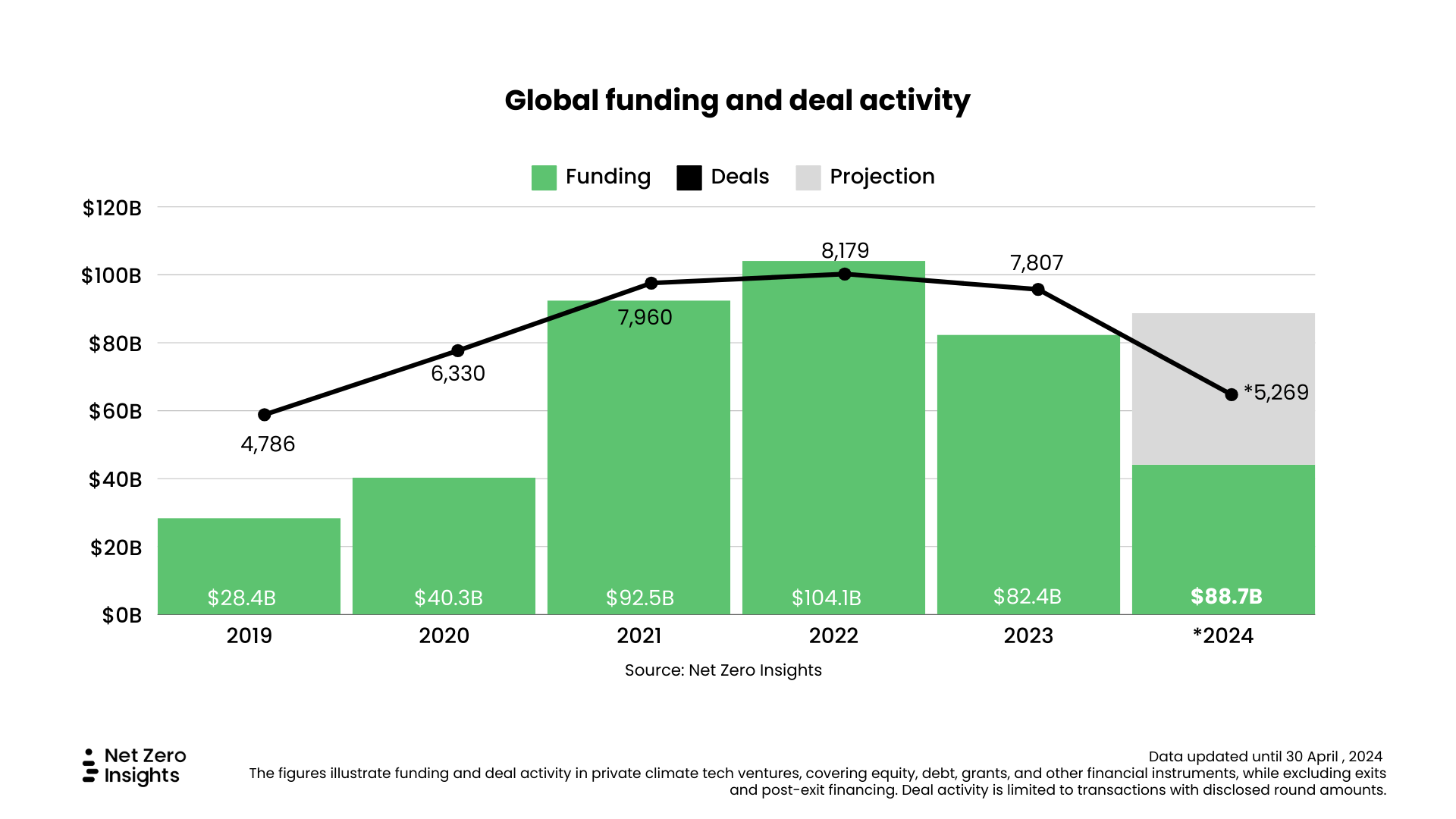

2150's first fund was raised during the climate tech boom. Government attention on climate was increasing. Climate venture funding was accelerating. The window felt open. The second fund closes in a different environment. Climate attention is still high, but the market is more skeptical. There's been a realization that not all climate tech is investable, and betting heavily on government subsidies is risky.

This probably explains why the second fund is slightly smaller. It's not a retreat. It's a recalibration. A smaller fund with a disciplined deployment strategy is more likely to hit target returns than a larger fund deployed promiscuously.

The focus on 20 investments rather than a larger number also suggests higher bar for each investment. Each company needs stronger fundamentals, clearer paths to revenue, more convincing unit economics. That's harder in a market where venture multiples are compressing and exit opportunities are limited.

2150 is also doing something smart: reserving 50% of the fund for follow-on investments. This means they're committing to back winners multiple times rather than diversifying across many small bets. If a portfolio company is gaining traction, 2150 will have capital available to support Series B and Series C rounds. This increases the odds that successful portfolio companies actually reach meaningful scale rather than running out of capital and dying.

The LP base also matters. When your limited partners include a sovereign wealth fund and a 150-year-old industrial company, you've got patient capital. These institutions aren't demanding venture returns. They're comfortable with 8-10% annual returns if they're confident about the thesis. That's fundamentally different from raising from endowments or family offices that expect 3x returns in 7 years.

Data Centers, AI, and the New Climate Tech Imperative

2150 is specifically excited about data centers and industrial automation, both of which have been turbo-charged by AI adoption. This isn't about backing AI companies directly. It's about backing the infrastructure that makes AI possible while making that infrastructure climate-viable.

Data centers consume roughly 1-2% of global electricity, a number that's rising as AI model training demands accelerate. Training large language models requires massive amounts of computational power running for weeks or months. That's energy-intensive. It also generates heat that needs to be managed. But here's the thing: data centers are currently one of the only sectors that's seriously trying to solve climate impact while growing.

Major cloud providers—Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure—have all committed to renewable energy targets. They're not doing this out of environmental virtue. They're doing it because renewable energy is increasingly cheaper than fossil fuel power in most regions. Data center operators have figured out that climate efficiency and financial efficiency often point in the same direction.

This creates an enormous market for climate tech startups serving data centers. You need better cooling systems. You need software that optimizes energy consumption. You need tools to predict and manage thermal load. You need energy management systems that balance computation against power availability. These are all valuable problems with existing customers who will pay for solutions.

Industrial automation is slightly different but follows a similar logic. European manufacturers need to maintain productivity despite shrinking workforces. They're automating. Automation requires robotics, AI, computer vision, and complex control systems. All of that can be done more efficiently than legacy industrial processes.

2150's insight is that both trends—data center expansion and industrial automation—are guaranteed to happen regardless of climate policy. But they also happen to be opportunities to build climate-better infrastructure if you architect it right from the beginning.

This is where the fund makes sense for institutional capital. You're not betting on climate policy. You're not betting on carbon pricing. You're betting on trends that are happening anyway—data center expansion, industrial automation—and backing technology companies that make those trends more efficient and sustainable as a side effect.

Urban areas, covering only 3% of Earth's land, contribute to 80% of global GDP and 70% of greenhouse gas emissions, highlighting their significance in climate solutions.

Measuring Climate Impact: Beyond Carbon Offsets

2150 measures success in two dimensions: financial returns and carbon impact. One megaton of emissions mitigated in the first year from their portfolio is significant. But how do you know that number is real?

This is where climate tech funds have a credibility problem. Many climate funds measure impact using carbon offset methodologies, which are notoriously imprecise. An offset methodology might claim that planting trees sequesters carbon based on forestry models. But those models are assumptions. Did the trees actually grow? Did somebody cut them down? Did the land use change anyway?

2150's approach is different. When they back a company making industrial heat pumps, the carbon impact is measurable in real time. Install a heat pump in a facility that was using natural gas boilers. Measure the energy consumption before and after. Calculate the emissions reduction based on actual data. That's not theoretical carbon accounting. That's real emissions reduction that happened.

Same with recycling. When Get Mobil recycles electronic waste, they're preventing emissions from mining new materials and processing virgin ore. That impact can be calculated based on lifecycle analysis data. It's not perfect, but it's grounded in physical reality.

Mission Zero's direct air capture is harder to measure because it requires assumptions about what would have happened with the captured carbon. But even there, if the carbon is utilized in industrial processes or permanently stored, there's a verifiable impact.

This focus on measurable impact is why institutional investors are comfortable backing 2150. The climate impact story isn't a story. It's a spreadsheet. You can audit it. You can verify it. That's how you get sovereign wealth funds to write checks.

The European Advantage: Why This Fund Matters Geographically

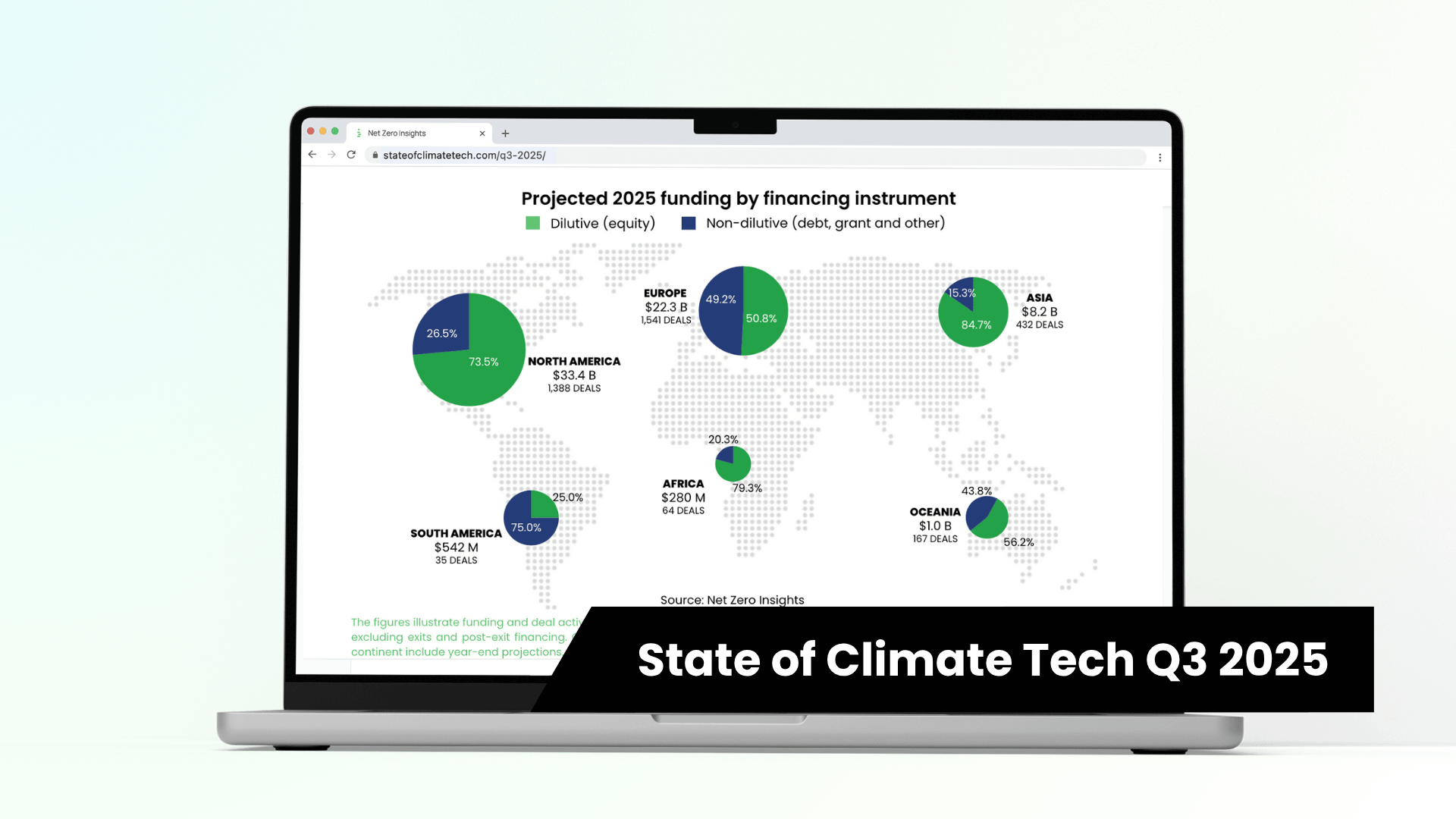

Climate tech is global, but 2150 is specifically European. That's not a limitation. It's a strategic advantage.

Europe has several structural advantages for climate tech investment. First, energy costs are higher than in the United States or most of Asia. This means efficiency improvements translate directly into cost savings. A technology that cuts energy consumption by 20% is worth implementing in Frankfurt. It might not be worth implementing in Texas where electricity is cheap.

Second, European regulation is stricter than most places. Building codes are tighter. Environmental standards are higher. Industrial emissions face regulations and pricing. This creates market pull for climate solutions. Companies invest in climate tech because they have to, or because it's economically attractive given regulatory constraints.

Third, Europe has capital. The continent has sovereign wealth funds, pension funds with trillions in assets, and institutional investors sophisticated enough to understand climate tech. Raising €210 million as a European climate fund is feasible. Raising the same amount in Southeast Asia or Sub-Saharan Africa would be much harder, despite those regions having enormous climate tech needs.

Fourth, Europe has technical expertise. You can find engineers who understand heat pump design, industrial automation, battery systems, and power electronics. You can build companies around world-class technical talent. That's an advantage.

The tradeoff is that European markets are smaller than global markets. A heat pump manufacturer focused on Europe won't reach the scale of a company focused on global markets. But for venture capital, European markets are sufficient. You can build meaningful businesses at €200-500 million revenue focused on Europe, and that's sufficient for venture capital returns.

2150 is also positioned to benefit from European policy tailwinds. The Green Deal. Emissions Trading Systems. Building renovation programs. These aren't guaranteed forever, but they create near-term demand for climate solutions.

Europe is projected to lose 100 million people by 2040, highlighting the need for industrial automation to maintain productivity and economic stability. Estimated data.

The Competitive Landscape: How 2150 Stands Apart

Climate tech venture funding has become crowded. There are now hundreds of climate funds globally. Some are focused on specific technologies. Some are focused on specific geographies. Some are focused on specific impact metrics.

What differentiates 2150 is their focus on cities and their commitment to unit economics. They're not competing on impact magnitude. They're competing on companies that can actually grow into sustainably profitable businesses.

That positions them differently than climate funds that are willing to finance unprofitable companies based on environmental impact alone. Those funds make sense if you believe government will eventually pay for carbon removal or if you believe venture capital will tolerate negative unit economics indefinitely. 2150 doesn't bet on that. They bet on companies that work as businesses.

They're also different from traditional venture funds that have added climate to their mandate. Those funds have all the incentive structures of venture capital. They need 10x returns. They need exits. That pushes them toward speculative technology bets that might achieve viral adoption. 2150 has institutional LP bases that are comfortable with lower returns, which allows them to back companies with more modest but more certain growth prospects.

The competitive advantage compounds. When you back good companies and help them grow, you develop reputation. You develop portfolio synergies. Companies in the same space start referring to you. LPs increasingly want to back teams with track records. 2150's first fund created that track record. The second fund capitalizes on it.

Future Trends: Where Climate Tech Venture Capital Is Heading

The €210 million raise signals several trends worth watching.

First, institutional capital is moving toward climate tech. When sovereign wealth funds and pension funds start writing checks, it's a signal that climate is transitioning from a niche investing category to a mainstream asset allocation decision. That means more capital will flow into the space, which paradoxically makes it harder for individual companies to stand out.

Second, impact measurement is becoming a requirement, not optional. Institutional investors won't deploy capital to climate funds that can't measure impact. This will push climate funds to back companies with verifiable carbon reduction, which favors technologies like heat pumps, recycling, and efficiency over speculative carbon removal.

Third, climate tech is bifurcating. You're seeing some companies achieve venture scale—companies like Rivian (electric vehicles) and Commonwealth Fusion Systems (nuclear fusion) raising massive rounds. But the median climate startup is getting smaller, more focused, more capital-efficient. A €5-6 million check from 2150 is bigger than it sounds if you structure the business right.

Fourth, geographic diversification of climate tech is accelerating. Climate tech hasn't been evenly distributed. Most investment has been in the United States and China. But as funding increases, it's spreading. European climate funds like 2150 will become more common. Investors will look at Southeast Asia, India, Latin America—regions with massive climate challenges and capital constraints.

Fifth, the intersection of AI and climate is becoming real, not hypothetical. AI doesn't solve climate change. But AI makes industrial optimization possible, which reduces emissions. AI makes energy management better. AI makes supply chain optimization feasible. Climate tech startups will increasingly incorporate AI, not as their core technology, but as an enabling layer that makes their core technology more efficient.

Investment Implications: What This Means for Limited Partners and Entrepreneurs

For limited partners evaluating climate funds, 2150 represents a template worth studying. They've figured out something difficult: how to back climate technology at venture scale with institutional capital and reasonable return expectations. They've done it by focusing on a specific constraint (cities), identifying specific problems (resource inefficiency), and backing specific companies (Atmos Zero, Get Mobil, Metycle, Mission Zero).

The model is replicable. You could do the same thing for coastal cities specifically. You could do it for agricultural regions. You could do it for manufacturing-dependent regions. The template is: identify a geographic or sectoral constraint, look at what gets consumed inefficiently, back companies solving those inefficiencies.

For entrepreneurs raising climate tech funding, the lesson is simpler. Build a business that works for customers who care about cost, not climate. Make climate reduction a side effect of better business fundamentals. If you structure it that way, institutional capital becomes accessible. If you structure it as "we're solving climate, hopefully we can find a business model," you'll struggle to raise from anyone except ideologically motivated climate funds.

This is a healthy evolution for the space. Climate tech that depends on climate ideology for success is fragile. Climate tech that depends on business fundamentals is durable.

The Megaton Milestone: Understanding Scale in Climate Tech

One megaton of carbon emissions mitigated in one year from a €290 million first fund is remarkable for context.

For comparison, the entire aviation industry generates about 1 billion tons of CO2 annually. Agriculture generates about 10 billion tons. Energy production generates about 30 billion tons. One megaton is a rounding error on those scales.

But for a venture fund? It's enormous. Most venture-backed companies never measure carbon impact at all. Most that do measure it theoretically, using lifecycle analysis and assumption-heavy methodologies. To have a portfolio that's actually prevented one million metric tons of CO2 equivalent from entering the atmosphere is legitimately impressive.

It also shows the power of operational impact over speculative impact. Heat pumps in manufacturing facilities create real impact. Recycling operations reduce mining impacts. Industrial automation lowers energy intensity. These aren't theoretical. They're measurable year to year.

If 2150 can hit one megaton per year from a €290 million fund with seven companies, and they scale that proportionally to €500 million in total capital, they could be looking at 2-3 megatons annually within five years. That starts to look like meaningful climate contribution, even if it's still small relative to global emissions.

This is where climate tech venture capital eventually has to go. Not billion-ton solutions (those are policy and energy infrastructure). But megaton-scale solutions that are economically viable, defensibly built, and genuinely reducing emissions through business fundamentals rather than ideology.

Structural Lessons: How to Build an Investable Climate Company

Looking at 2150's portfolio and thesis, certain patterns emerge about what makes climate tech investable at scale.

First, solve a cost problem that happens to be climate-related. Heat pumps cut energy costs and emissions. Recycling creates revenue and avoids mining. Industrial automation improves productivity and lowers energy per unit. In each case, the business case comes first. The climate benefit is real but secondary.

Second, focus on systems where inefficiency is expensive. Industrial facilities pay for every unit of wasted energy. Manufacturing plants pay for every ton of material that ends up in landfills. This creates budget for solutions. You're not asking someone to spend money on climate. You're asking them to spend money on operational efficiency.

Third, target industries with regulatory or cost pressures. Europe's carbon pricing. Building energy directives. Labor shortages pushing automation. These create pull for solutions. You're riding waves of change that are happening anyway.

Fourth, build companies around existing supply chains and customer bases. 2150's portfolio companies aren't inventing entirely new categories. They're making existing categories more efficient and sustainable. That's faster to scale and easier to fund.

Fifth, measure everything. The difference between claimed impact and real impact is where most climate tech fails credibility checks. Companies like 2150 back will be able to show customers, investors, and regulators exactly what impact they're creating. That's defensible.

These aren't revolutionary insights. But they're often ignored by climate startups that lead with ideology instead of pragmatism. 2150's success suggests the market is moving toward pragmatism.

Conclusion: The Future of Climate Tech Investment

2150's €210 million second fund closing represents a milestone in how climate technology gets funded and scaled. It shows institutional capital has figured out how to allocate to climate without requiring climate ideology to substitute for business fundamentals.

The fund's thesis is elegant precisely because it's narrow. Focus on cities. Look at what gets consumed. Identify inefficiencies. Back companies that eliminate those inefficiencies. Climate reduction happens as a side effect. This approach attracts institutional capital because it aligns environmental and business incentives rather than positing them as trade-offs.

It also shows a maturing understanding of how climate actually gets solved. Not through revolutionary technology that doesn't exist yet. But through better deployment of technology that already works. Heat pumps are decades old. Recycling is ancient. Industrial automation is established. The climate impact comes from systematically replacing less efficient versions with more efficient versions. That's a venture capital scale problem, and it's how massive emissions reductions actually happen.

What's particularly interesting is that this approach works regardless of climate policy direction. If carbon prices disappear, these companies still thrive because they're cheaper to operate. If regulations disappear, these companies still thrive because customers prefer lower costs. That robustness is why institutional capital is comfortable deploying billions into climate tech funds like 2150.

The path forward isn't harder climate regulation or bigger government commitments. It's better business fundamentals. 2150's approach suggests that the future of climate tech isn't venture capital betting on speculative solutions. It's venture capital backing the best companies to solve problems customers are already desperate to address.

That shift—from ideology-driven to pragmatism-driven climate tech—is what allows €210 million to flow into a fund focused on cities solving emissions through industrial heat pumps, recycling, and automation. It's not exciting in the way that direct air capture or fusion is exciting. But it's powerful because it's already working, already scaling, and already creating emissions reductions you can measure today.

FAQ

What is 2150 and what makes it different from other climate venture funds?

2150 is a Europe-based venture capital fund focused specifically on backing climate technology startups in urban areas. What differentiates them is their thesis that cities are the constraint for climate solutions—rather than betting on speculative global climate technology, they focus on solving resource inefficiency problems within urban systems. They measure success both by financial returns and measurable carbon impact, and they prioritize companies with strong business fundamentals where climate reduction is a beneficial side effect, not the primary value proposition.

How does 2150's investment approach work in practice?

2150 identifies inefficiencies in urban resource flows—energy, materials, waste—and backs companies that eliminate those inefficiencies. They make equity investments typically in the €5-6 million range, targeting companies preparing for Series A funding rounds. They reserve 50% of each fund for follow-on investments in successful portfolio companies, allowing them to support winners through multiple funding rounds. Their portfolio spans industrial heat pumps, electronic waste recycling, scrap metals marketplaces, and direct air capture technology.

Why are sovereign wealth funds and pension funds investing in climate venture funds like 2150?

Institutional investors like sovereign wealth funds and pension funds are allocating capital to climate funds because they're increasingly confident in the business case for climate technology. Funds like 2150 attract institutional capital by demonstrating measurable financial returns and verifiable carbon impact through operational efficiency improvements rather than speculative technology bets. These investors can accept lower venture-scale returns (8-10% annually) in exchange for greater certainty about both business performance and climate outcomes.

What is the significance of 2150 achieving one megaton of carbon emissions mitigation in one year?

Achieving one megaton of verified carbon emissions reduction from a relatively small venture fund's portfolio in a single year demonstrates that venture-backed climate tech can create meaningful impact within years rather than decades. This milestone shows that focusing on operational efficiency improvements in existing industries—rather than waiting for revolutionary technology—produces real, measurable climate benefits that institutional investors can verify and track. It also proves that venture-scale capital can support climate solutions without requiring government subsidies or carbon pricing mechanisms.

How does 2150's geographic focus on Europe create investment advantages?

Europe provides several structural advantages for climate tech investment: higher energy costs make efficiency improvements economically attractive, stricter environmental regulations create market pull for climate solutions, existing capital and technical expertise enable company building, and policy support through programs like the EU Green Deal creates near-term demand. While European markets are smaller than global markets, they're sufficient for venture capital returns and allow 2150 to focus capital where regulatory and cost pressures are strongest.

What role does artificial intelligence play in 2150's investment strategy?

2150 is excited about opportunities in data centers and industrial automation, both heavily influenced by AI adoption. However, they're not backing AI companies directly—rather, they're backing industrial and infrastructure companies that use AI to become more efficient. Data centers require massive computational power and cooling infrastructure, creating demand for climate solutions. Industrial automation driven by AI enables European manufacturers to maintain productivity despite labor shortages, while also reducing energy intensity. In both cases, climate benefits emerge as side effects of solving fundamental business problems.

How should entrepreneurs structure climate tech companies to attract institutional capital like 2150?

Successful climate tech companies that attract institutional capital typically lead with the business case rather than climate ideology. Build solutions that reduce costs for customers—lower energy bills, higher material recovery, improved operational efficiency—and treat carbon reduction as a measurable side effect. Focus on solving problems in existing, established industries with clear customer bases and existing supply chains. Measure impact through real operational data rather than lifecycle analysis assumptions. Structure companies around existing resource inefficiencies that are expensive to maintain, making your solution valuable regardless of climate policy direction.

What are the implications of 2150's €210 million second fund for the broader climate tech investment landscape?

The successful closure of 2150's second fund signals that institutional capital is moving from viewing climate tech as a niche category to treating it as a mainstream asset allocation decision. It demonstrates that climate funds with proven track records and clear measurement methodologies can attract serious capital from sovereign wealth funds and pension funds. This trend suggests continued growth in climate tech funding, but with increasing focus on companies with viable business models and measurable impact rather than speculative technological bets.

Key Takeaways

- 2150 raised €210 million for their second fund by focusing on cities as the constraint for climate solutions, bringing total AUM to €500 million

- The fund's thesis positions climate benefits as a side effect of operational efficiency improvements, not the primary investment thesis, which attracts institutional capital

- 2150's portfolio achieved one megaton of verified carbon emissions reduction in one year from just seven invested companies, demonstrating tangible climate impact at venture scale

- European demographic challenges (100 million population loss by 2040) drive demand for industrial automation and efficiency—creating venture-scale business opportunities with climate co-benefits

- Climate tech investment is bifurcating toward companies with strong unit economics and measurable impact, moving away from speculative technology bets dependent on government subsidies

Related Articles

- How E-Bike Battery Swapping Powers Food Carts: The PopWheels Model [2025]

- The Hidden Terawatt: Why 1TW of Geothermal Power Is Being Ignored [2025]

- Humanoid Robots in Factories: The Real Shift Away From Labs [2025]

- Microsoft's Carbon Removal Strategy: Inside Varaha's Asia-First Deal [2025]

- Skild AI Hits $14B Valuation: Robotics Foundation Models Explained [2025]

- CES 2026 Robots: The Good, Bad, and Revolutionary [2025]

![How 2150's €210M Fund Is Reshaping Climate Tech for Urban Carbon Solutions [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-2150-s-210m-fund-is-reshaping-climate-tech-for-urban-car/image-1-1769449050819.jpg)