Inside Pig Butchering Scam Compounds: How Forced Labor Fuels Cybercrime

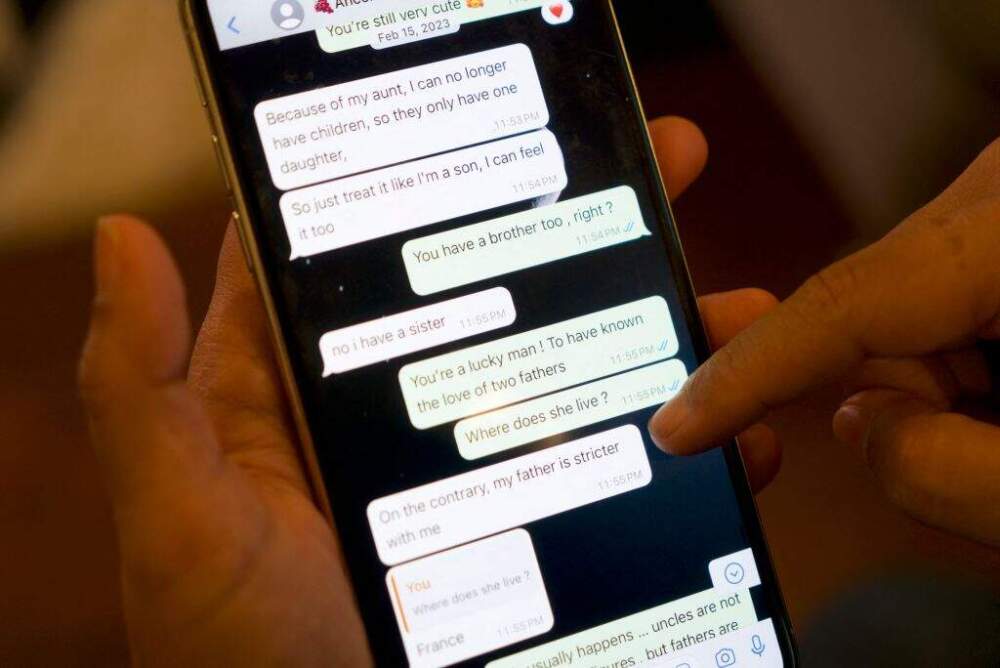

Everybody thinks scams happen at the click of a button. Someone shoots you a message on social media. They claim to be an investor, or a beautiful woman interested in romance. They build trust, gain your confidence, and eventually convince you to send money to a crypto wallet that doesn't belong to them. What most people don't realize is that behind that message is often not a sophisticated hacker sitting in a dark basement. It's something far darker: a person trapped in a compound, forced to work 15-hour shifts, unable to leave, their passport taken away, fined for the smallest infractions, and coerced into committing fraud to survive.

In April 2024, a whistleblower trapped inside one of these operations managed to leak thousands of pages of internal communications from a scam compound in Northern Laos. These documents reveal an operation that combines the worst elements of corporate management with human trafficking and organized crime. The compound, known as Boshang, is one of dozens operating across Southeast Asia, enslaving hundreds of thousands of people in what's become the most profitable form of cybercrime in the world.

The leaks are unprecedented in their scope and detail. Over 4,200 pages of WhatsApp messages, operational flowcharts, training guides, scam scripts, and internal documents paint a picture of an industry that generates tens of billions of dollars annually while simultaneously destroying the lives of both victims and the trapped workers forced to defraud them.

What makes this story so important now is that law enforcement globally is finally waking up to the scale of the problem. Intelligence agencies have begun coordinating across borders. Tech platforms are cracking down on recruitment ads. And yet, the compounds keep operating, keep expanding, and keep trapping new victims every single day.

This is the story of how a multi-billion-dollar criminal industry hides in plain sight, how it recruits and controls an enslaved workforce, and what it will actually take to stop it.

TL; DR

- Pig butchering scams steal tens of billions annually from victims globally, often defrauding individuals out of hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars each through fake romance and cryptocurrency investment schemes.

- Hundreds of thousands of forced laborers are enslaved in Southeast Asian scam compounds across Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar, and Thailand, trapped through debt bondage, passport confiscation, and threats of violence.

- Leaked documents from whistleblower Mohammad Muzahir expose the operational details of the Boshang compound, including 4,200 pages of internal WhatsApp messages revealing how these operations function like corporate entities while employing brutal psychological manipulation and coercion.

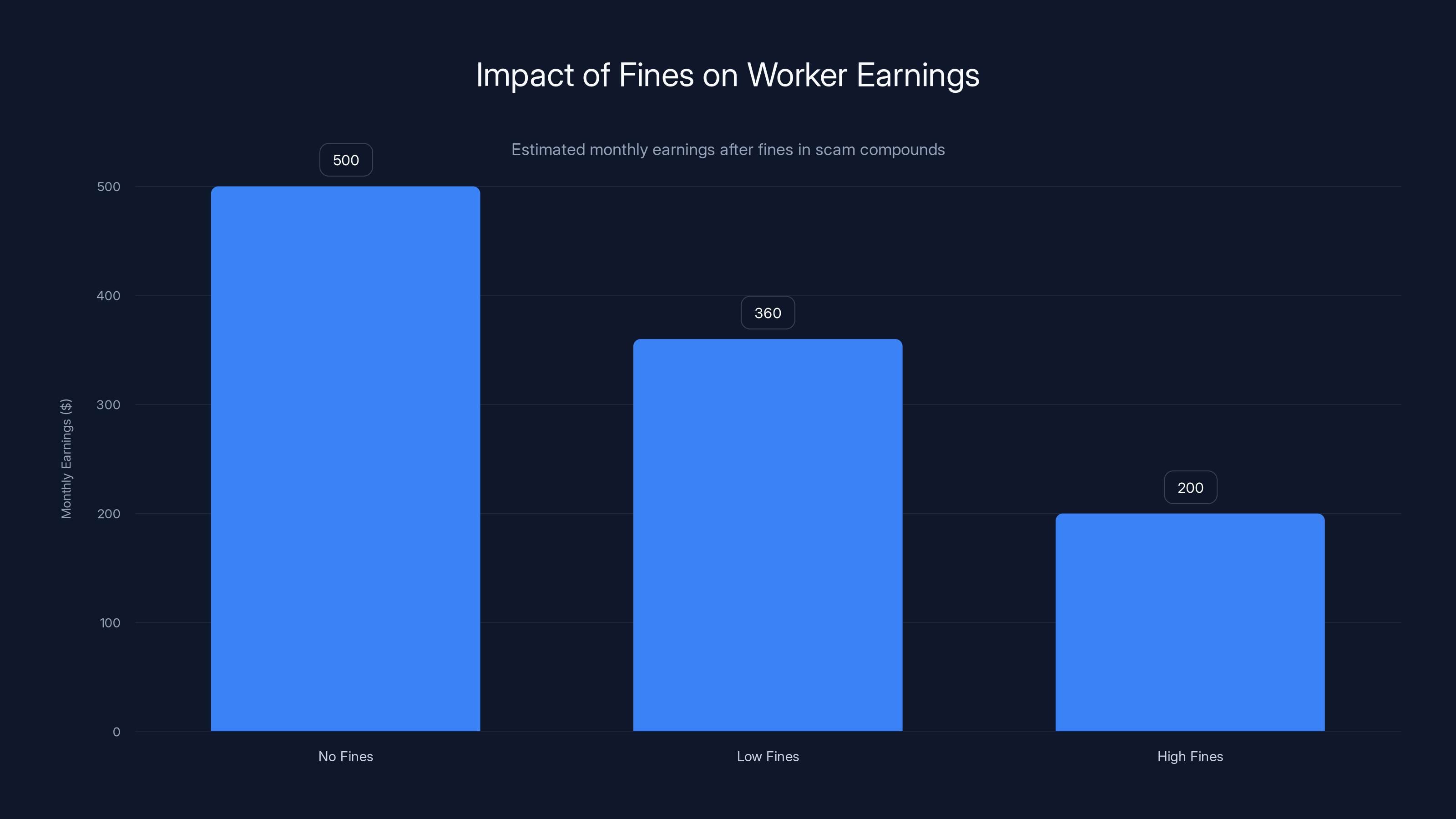

- The economics are staggering: workers paid roughly $500 monthly base salary while generating millions in fraudulent revenue, with fines systematically preventing them from ever earning enough to leave.

- Law enforcement is ramping up efforts but the compounds continue expanding because recruitment funnels remain active, cryptocurrencies enable easy money laundering, and border security in Southeast Asia remains porous.

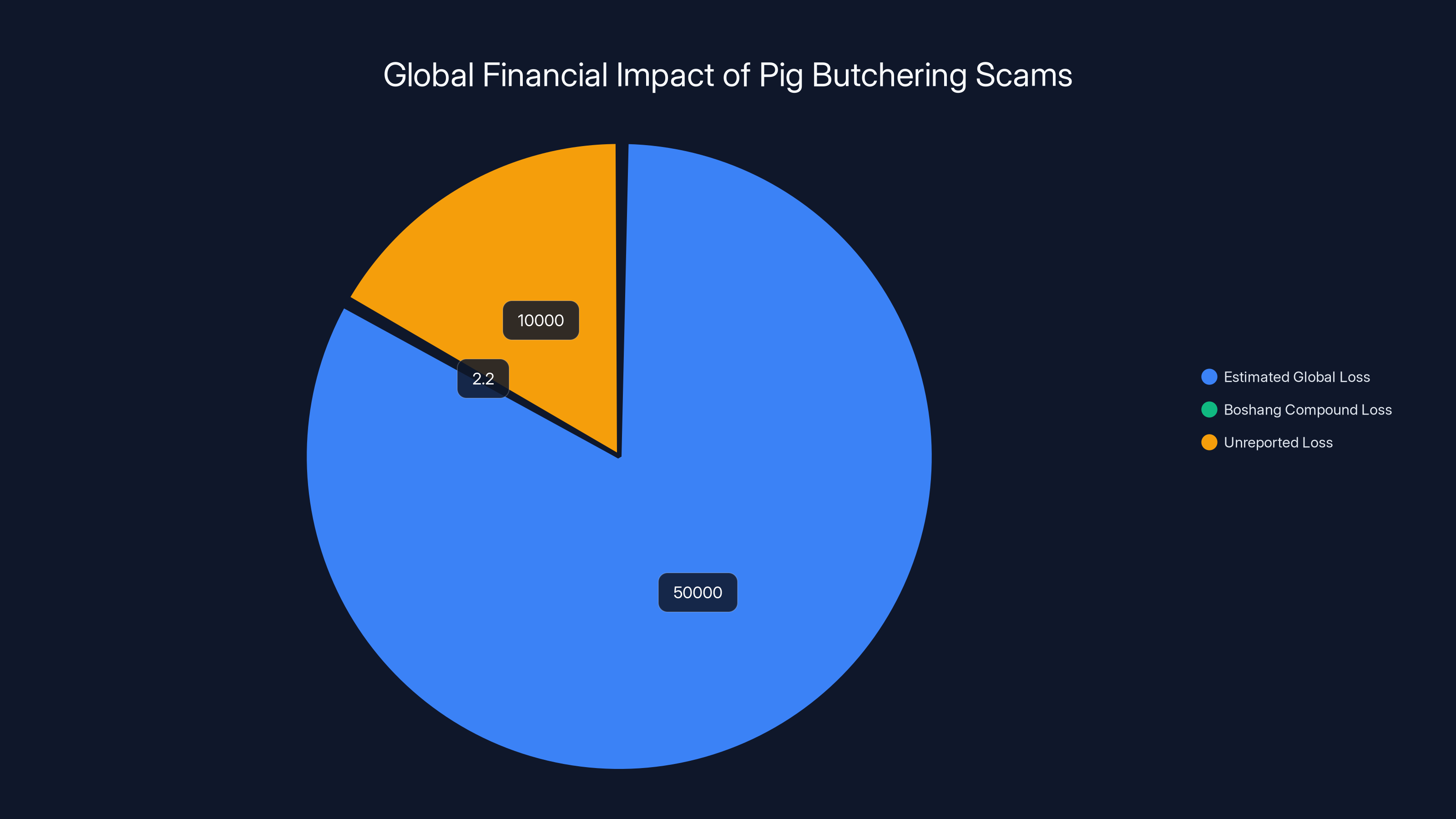

Pig butchering scams are estimated to steal $10-50 billion annually, with individual compounds like Boshang defrauding millions in weeks. Estimated data.

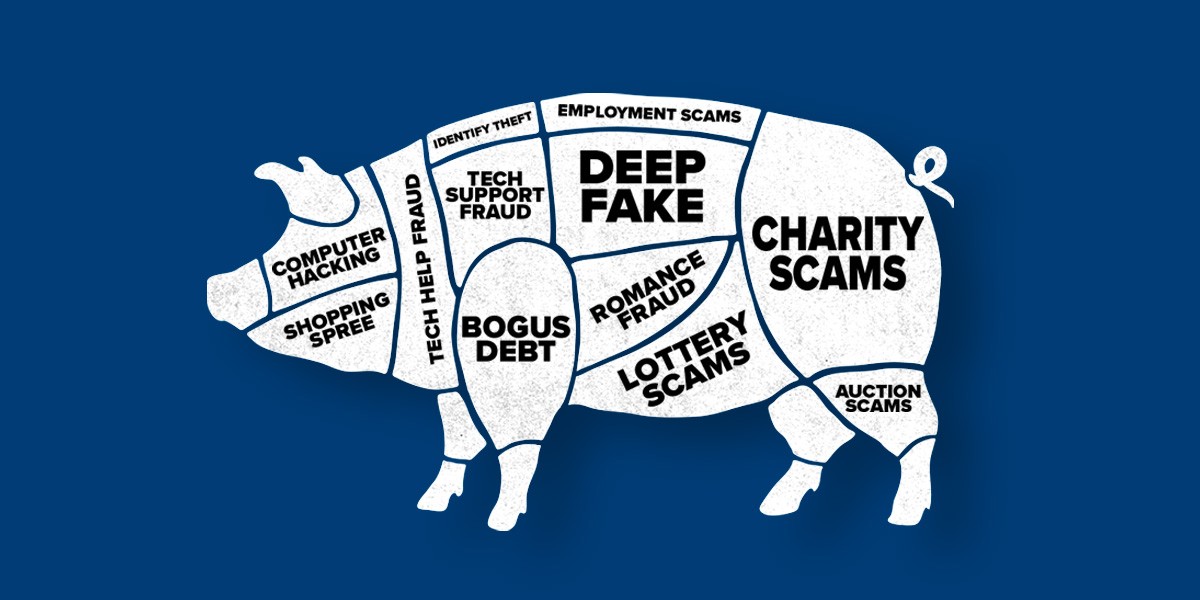

What Exactly Is a Pig Butchering Scam?

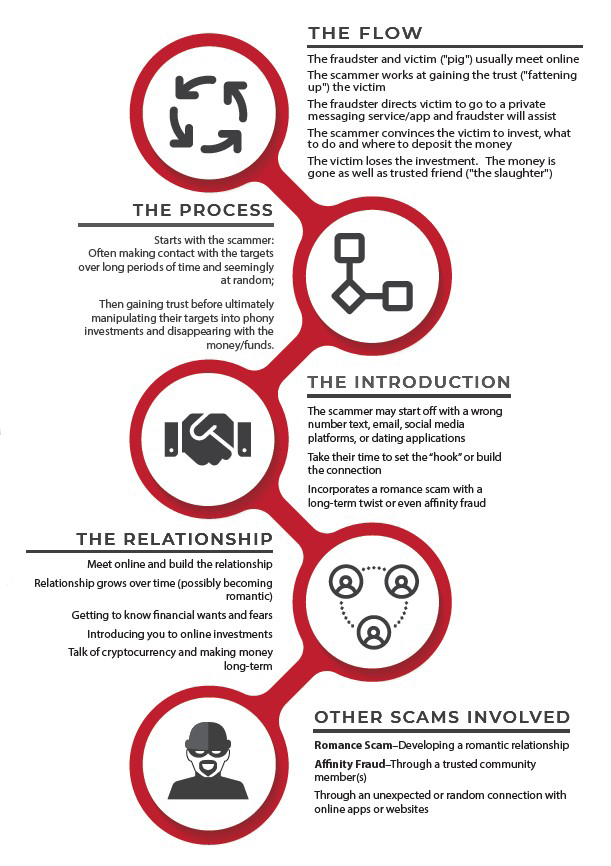

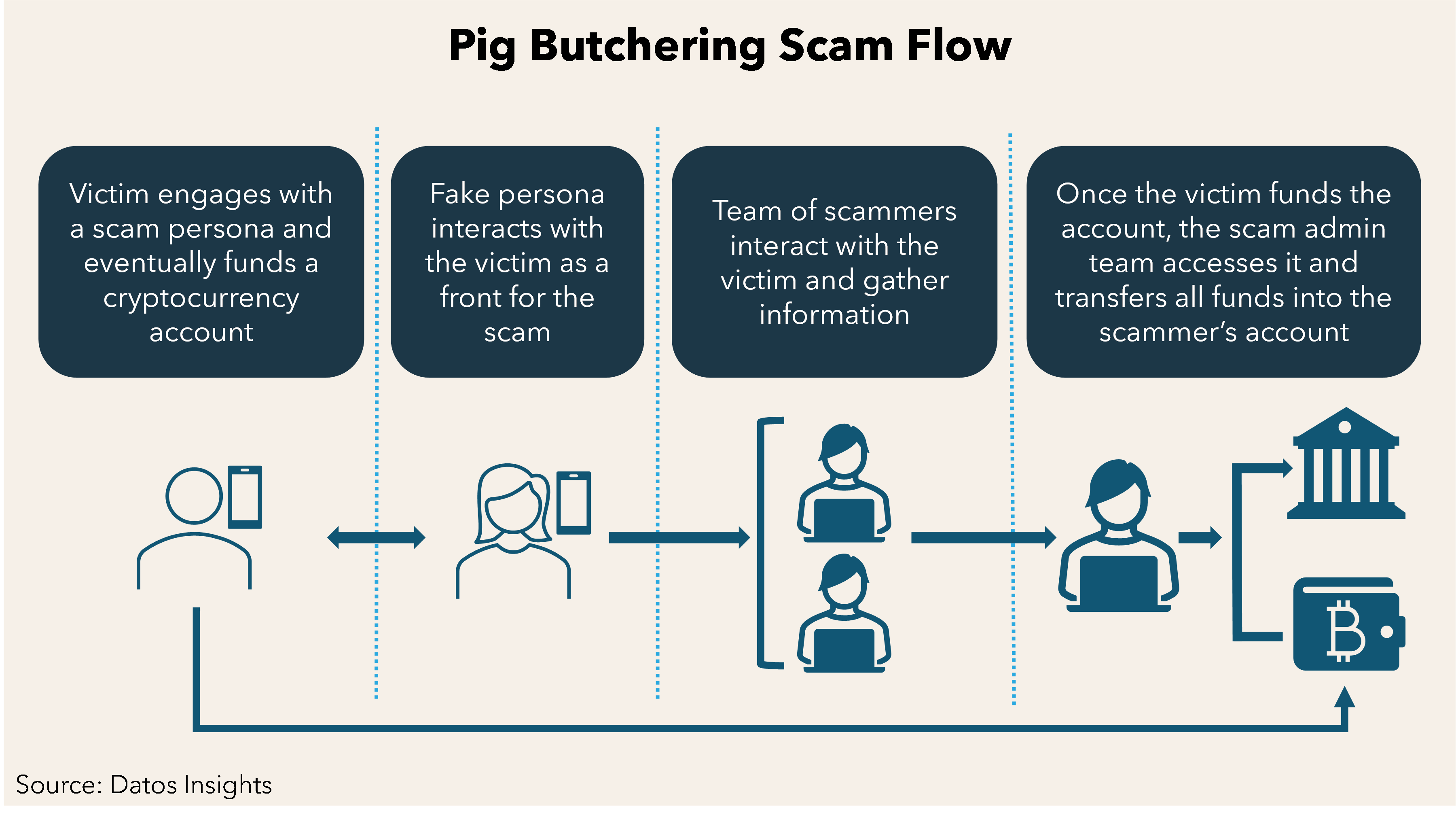

The term "pig butchering" comes from a Chinese metaphor. You raise a pig, feed it well, care for it, build its trust. Then you slaughter it. The scam works the same way.

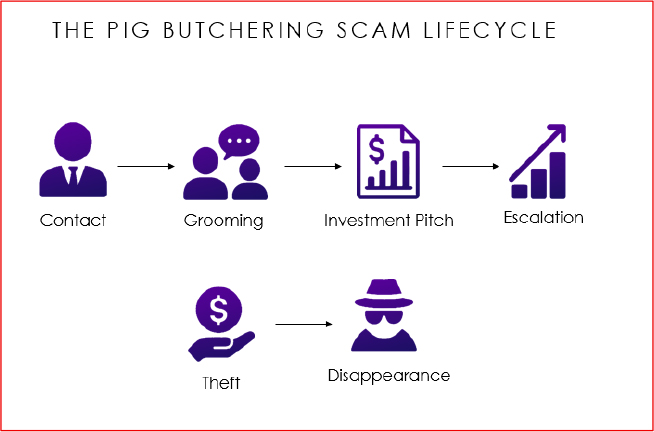

It typically begins with contact through dating apps, social media, or messaging platforms. The scammer, operating from a compound, creates a fake identity. They might pose as a wealthy businessman, an attractive woman looking for love, or an investment advisor with insider knowledge of cryptocurrency markets. The scammer builds rapport over weeks or months, establishing genuine emotional connections with the victim. They share photos, tell stories, discuss dreams and goals.

Then, when trust is established, the pitch comes. They're facing a financial emergency. Or they've found an incredible investment opportunity in cryptocurrency or a startup. They ask the victim if they'd be interested in helping them, or investing themselves. Once the victim sends money, the operation either disappears completely, or in more sophisticated versions, the victim receives fake screenshots showing their investment growing. The scammer encourages them to invest more. Eventually, when the victim tries to withdraw their profits, they're told they need to pay taxes or fees first. Those fees, of course, are never refunded.

The sophistication varies enormously. Some operations are relatively simple, with individual scammers running small schemes from their homes. But the larger operations, like Boshang, are industrial-scale enterprises. They employ hundreds of people, work in shifts, have specialized departments, training programs, and management hierarchies. They're not just scamming individuals. They're scamming hundreds or thousands simultaneously, each with different relationship development timelines, investment amounts, and withdrawal cycles.

What's different about contemporary pig butchering schemes compared to earlier forms of romance scams or advance-fee fraud is the cryptocurrency angle and the sheer scale. Traditional scams might defraud a few people out of tens of thousands. Pig butchering operations steal billions. One victim can lose half a million dollars. The Boshang compound alone, according to analysis of leaked chats, fraudulently obtained around $2.2 million in just 11 weeks of recorded activity from 30+ workers. Scale that up across an entire year, across dozens of compounds, and you're looking at billions globally.

Estimated data shows that fines significantly reduce workers' monthly earnings, extending the time needed to buy out their contracts.

The Scale: How Widespread Are Scam Compounds?

Think Southeast Asia has a small problem with scam compounds. Think again.

According to research and law enforcement estimates, there are dozens of major scam compounds operating across the region. The primary hub is the Golden Triangle, a special economic zone straddling Laos, Myanmar, and Thailand. But operations also exist in Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia, and other countries. Compounds range in size from a few dozen workers to operations with several hundred.

The total number of enslaved workers is staggering. Conservative estimates place it at several hundred thousand people. Some estimates go much higher. These aren't people who chose to be there. The vast majority were recruited through false job advertisements. They were promised legitimate work as translators, customer service representatives, or software developers. They were told they'd earn good money, gain experience, and have opportunities for advancement.

Instead, they arrived at compounds where their documents were confiscated, where they discovered the real nature of the work, and where they learned that leaving was essentially impossible. Some have been trapped for years. Escape attempts result in violence. Threats are made against families back home. The debt system ensures that even if someone wanted to leave, they'd owe thousands more than they could possibly earn.

The geographic concentration in the Golden Triangle isn't accidental. The region is poorly governed, with limited law enforcement cooperation between countries. Corruption is endemic. Border security is porous. The special economic zones operate with their own rules, making it easier for criminal organizations to set up operations. Myanmar's civil war has destabilized the region further, creating ungoverned spaces where organized crime thrives.

But here's the critical thing: these compounds aren't hidden from the regional governments. They're often operating with local knowledge, tacit approval, or outright cooperation from officials who benefit from bribes and kickbacks. Some compounds have been raided and briefly shut down, but they simply relocate and restart. The infrastructure persists.

Who Gets Trapped: The Recruitment Pipeline

Most enslaved workers in scam compounds are not criminals. They're not there by choice. They're ordinary people who fell victim to deceptive recruitment.

The recruitment pipeline is well-established. Fake job advertisements appear on legitimate job sites, social media, and recruitment platforms. The positions sound attractive: customer service representatives earning $1,500 monthly, software developers, translators, logistics coordinators. Many ads specifically target people from economically disadvantaged regions. An advertisement might be posted in Vietnamese, Burmese, or Filipino job forums, targeting people desperate for work and willing to relocate.

The targeted regions are specific. Northern Thailand, rural Laos, Myanmar's border regions, poor provinces in Vietnam, parts of Cambodia. These are areas with limited economic opportunity, where

Recruited workers often spend several thousand dollars of their own money on the journey to the compound. Transportation, visa processing, fees for "job placement companies" that are actually smuggling operations. By the time they arrive at the facility, they've already invested heavily.

The moment they enter the compound and discover the truth, they face a calculated choice: stay and try to work their way out through the debt system, or attempt to leave and face serious consequences. The first night, most don't attempt escape. They're confused, they're hoping this is somehow a misunderstanding. By night three, when they understand it's organized crime and they're essentially imprisoned, escape has become far more dangerous.

Some workers come from wealthy countries too. Indian, Pakistani, and Filipino workers have been trapped in these compounds. A few have even been recruited from the United States and Europe, convinced they'd be working in cryptocurrency trading or fintech companies. The sophistication of the deception varies, but the result is always the same: someone realizes they're trapped doing illegal work and have no obvious way out.

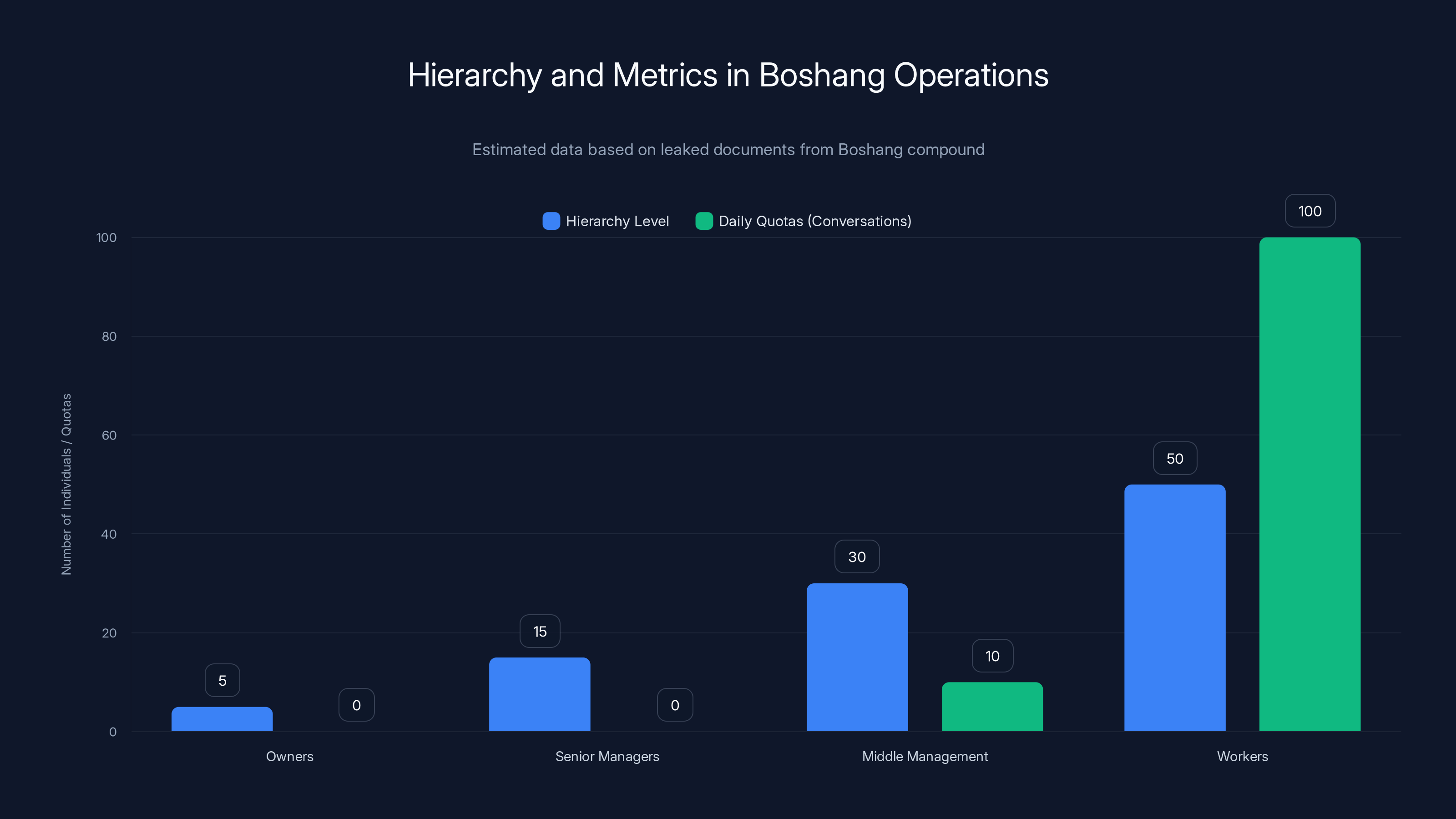

Estimated data shows a clear hierarchy with owners at the top and workers at the bottom, who face high daily quotas for initiating conversations. Estimated data.

Inside Boshang: The Leaked Documents

In June 2024, Mohammad Muzahir, an Indian man trapped inside the Boshang compound, managed to contact a journalist while still in captivity. Over several weeks, he leaked extensive internal materials from the operation. His leaks included operational flowcharts, training manuals, scam scripts, internal policies, and most damning of all, screen recordings of three months of WhatsApp group chats between workers and management.

Those WhatsApp messages represent an extraordinary window into how these operations actually function. They're not mysterious or shadowy. They're weirdly corporate. Managers post motivational messages about teamwork and customer focus. There are performance metrics and quotas. There are fines listed in spreadsheets. There are announcements about policy changes and schedule updates. If you didn't know the context, you might think you were reading the internal communications of a legitimate tech startup.

Except the context is slavery and systematic fraud.

The chats reveal several critical things about how the compound operates. First, there's a clear hierarchy. At the top are the owners, likely organized crime figures. Below them are senior managers who handle strategic decisions and criminal organization. Middle management handles team leads and worker supervision. At the bottom are the workers themselves, performing the actual scamming work.

Second, there's a sophisticated system of metrics and quotas. Workers are required to initiate a certain number of conversations with potential victims daily. They're tracked on how many victims respond, how many they build relationships with over weeks, how many eventually send money, and how much money is sent. There are individual targets and team targets. Performance is announced publicly in the group chats, creating peer pressure and competition.

Third, there's an elaborate system of fines that essentially prevents workers from ever breaking even on their "contract." The base salary of roughly

Fourth, the chats reveal the psychological pressure tactics used to keep workers compliant. Managers alternate between motivational messages and threatening statements. "Don't resist the company's rules and regulations," one message warns. "Otherwise you can't survive here." Another manager celebrates team success while noting that underperformers will face consequences. Workers receive public praise for achieving targets and public shaming for failures.

The Mathematics of Enslavement

The financial system in scam compounds is designed with brutal precision. It appears to offer workers a path to freedom while actually ensuring permanent entrapment.

Let's work through the math. A worker starts with a contract buyout fee of

But here's where the system breaks them. Fines are applied for any deviation from the rules. The average worker in the leaked chats was fined between 1,000-3,000 yuan (

So rather than earning

Real workers in the leaked chats described being functionally broke despite working 75+ hours weekly. They couldn't afford to send money home. They couldn't buy basic supplies. They were entirely dependent on the compound for food, shelter, and everything else.

Meanwhile, the compound is generating massive profits. Conservatively, if 30 workers are generating

The workers see almost none of this. It's a relationship that resembles pre-abolition slavery economics. Workers produce value worth hundreds of thousands while being compensated with barely enough to survive.

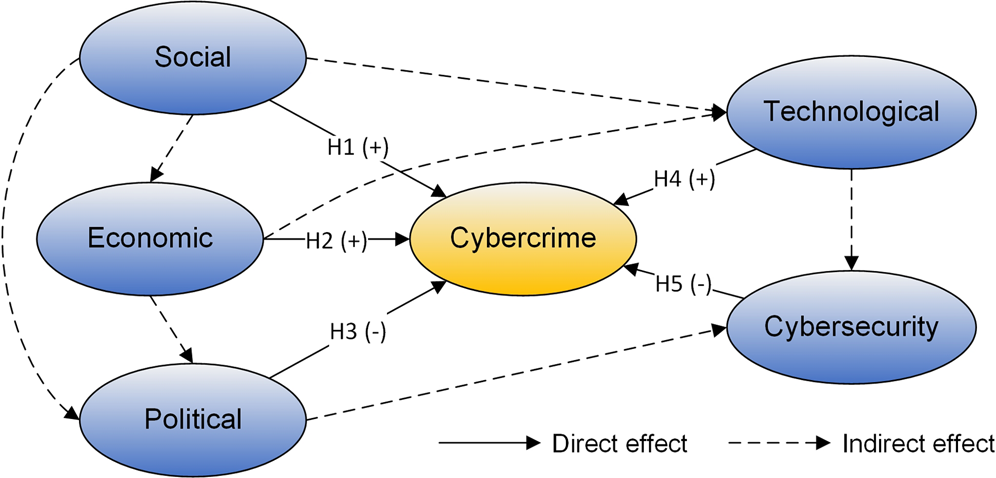

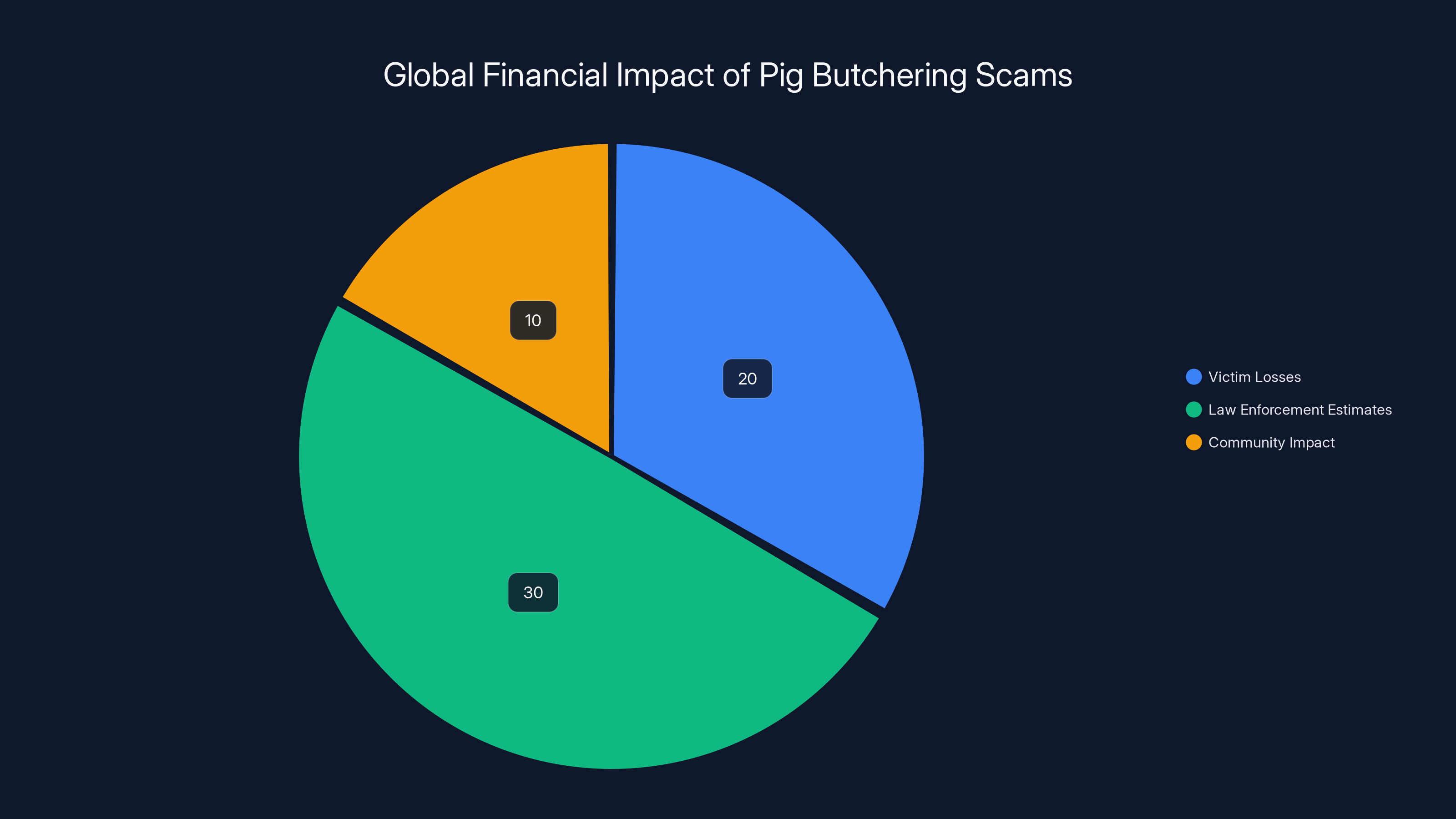

Estimated data shows that pig butchering scams result in $10-50 billion in losses annually, with significant financial and community impacts.

The Psychological Operations

What separates contemporary scam compounds from traditional labor trafficking is the sophisticated psychological manipulation employed alongside physical control.

Managers in the Boshang compound used a calculated mix of motivation and threat. They'd send lengthy messages about the importance of the work, framed as building a business and contributing to the organization. They'd celebrate individual achievements and team milestones. They'd create the impression that this is a legitimate company where hard work is rewarded.

Simultaneously, they'd include explicit threats. "Don't resist the company's rules," the message warned. "Otherwise you can't survive here." The implication was clear: resistance leads to consequences. And these weren't abstract threats. Workers knew that people who tried to escape faced violence. Stories circulated about what happened to defectors.

This combination is devastatingly effective. Workers are trapped by both physical constraints (passport confiscation, remote location, overwhelming fines that create debt) and psychological constraints (identification with the organization's goals, fear of punishment, shame at their situation).

Psychologists studying cult behavior recognize these exact patterns: isolation from outside information, construction of an in-group identity, alternation between reward and punishment, and a charismatic leadership structure that provides clear direction and purpose.

The WhatsApp chats reveal managers explicitly engaging in these tactics. They'd publicly praise workers who achieved targets, creating competition and division among the workforce. This prevented unified resistance. Workers who performed well were given special privileges: better sleep schedules, less intensive fine-focused monitoring, or slightly better food. This incentivized compliance and created a hierarchy within the enslaved workers themselves.

Another tactic was the normalization of unethical behavior. The scamming work itself is dehumanizing. Workers are instructing people to send their life savings to fake investment schemes or non-existent romantic partners. Most workers initially feel guilt about this. Managers addressed this by framing victims as deserving of their fate, as stupid or greedy people who should have known better. This rationalization helped workers compartmentalize the moral wrongness of their actions and focus on meeting quotas.

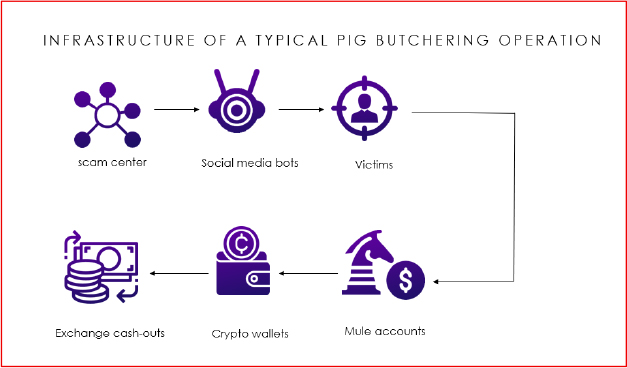

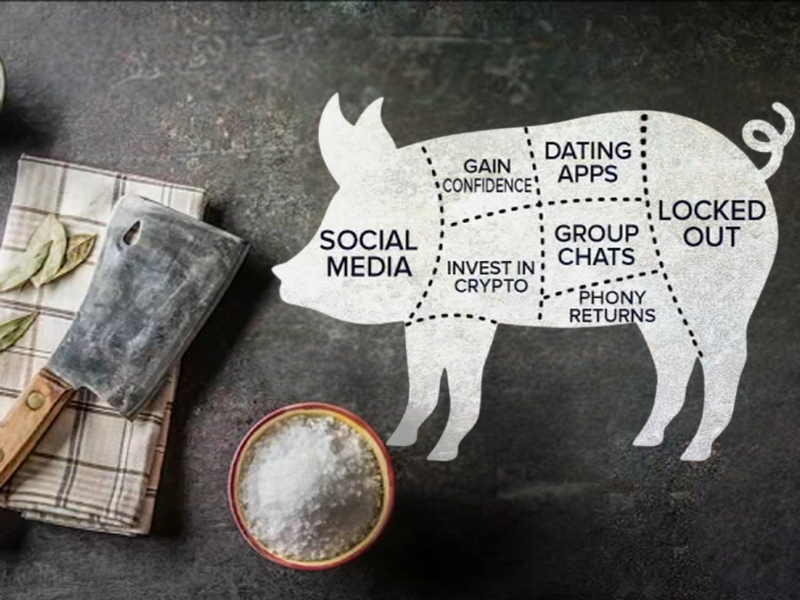

The Revenue Model: Scamming at Scale

The scam compounds aren't monolithic operations with a single scamming method. They've evolved sophisticated operations with multiple parallel scamming schemes running simultaneously, often targeting different victim demographics.

The primary method remains romance scams. Workers establish fake identities, usually posing as attractive women or successful men. They match with victims on dating apps or social media. The initial weeks involve genuine relationship building: sharing photos (usually stolen from social media), asking personal questions, expressing interest in the victim's life. They learn about the victim's financial situation, their vulnerabilities, their dreams.

Once sufficient trust is built, the scammer introduces a reason to send money. It might be medical emergency for a family member, business investment opportunity, or immigration fees for the romantic partner to travel to meet the victim. Early requests are small,

The cryptocurrency angle is crucial. Rather than requesting bank transfers that can be reversed or tracked, scammers direct victims to cryptocurrency exchanges where they purchase Bitcoin or Ethereum. This money is then transferred to wallets controlled by the criminal organization. Once the money is in crypto, it's nearly impossible to recover. The trail is permanent but practically untraceable if the receiving wallet is regularly moved and cleaned through mixing services.

A second major scamming method is the "investment opportunity" scheme. Workers present themselves as successful traders or investment advisors. They'll show victims websites (often elaborate fakes) claiming to be legitimate cryptocurrency trading platforms or fintech companies. They'll offer access to exclusive investment opportunities with guaranteed returns. Victims are convinced to invest

A third method is employment scams targeting vulnerable populations. Scammers pose as recruiters for multinational companies, offering remote work positions. Once the target is engaged, they're told they need to pay for training, certification, or equipment upfront. Victims send hundreds or thousands, thinking they're investing in their career.

Each scamming worker doesn't specialize in one method. They rotate through different schemes throughout their shift, targeting new victims or maintaining existing victim relationships. The work is essentially industrial-scale fraud, with workers as production units and victims as raw material to be processed for maximum extraction.

The economic efficiency is remarkable from a purely criminal perspective. A single worker, working an 8-hour shift, might initiate conversations with 10-15 potential victims. If 20% respond, that's 2-3 active conversations. If 10% of active conversations eventually result in money being sent, that's one victim per shift being defrauded of unknown amounts. Some victims lose thousands of dollars to a single worker. Some lose nothing. But averaged across dozens of workers, the operation generates millions monthly.

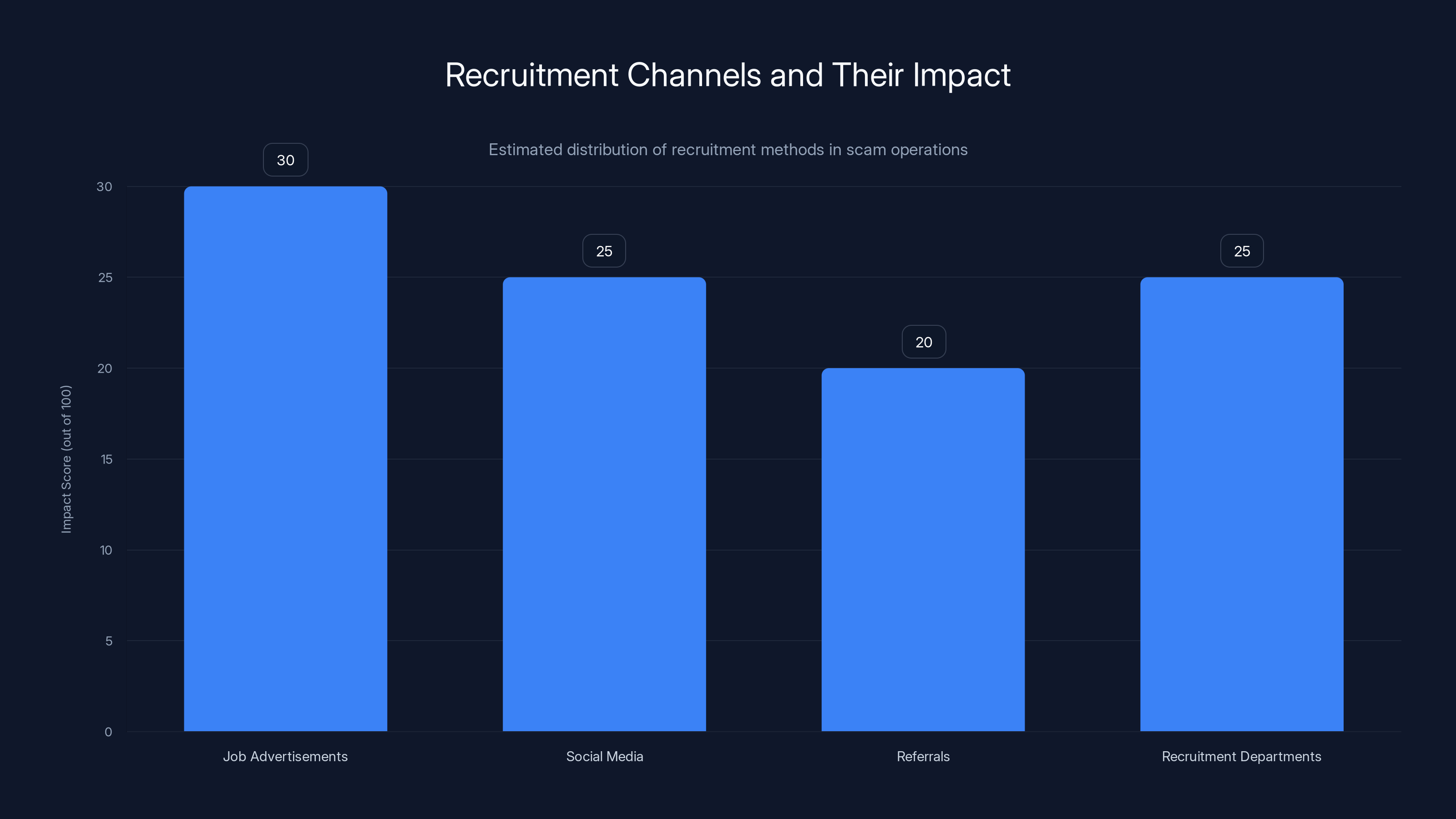

Job advertisements and recruitment departments are estimated to be the most impactful channels in recruiting for scam operations, each contributing significantly to the recruitment funnel. Estimated data.

How Law Enforcement Is Responding

For years, law enforcement agencies largely treated scam compounds as a Southeast Asia problem. It wasn't their jurisdiction, it involved cryptocurrency which was poorly regulated, and most victims didn't report crimes out of shame.

That's changing, albeit slowly.

The United States has expanded the definition of trafficking crimes to explicitly include forced labor in scam operations. The FBI, ICE, and international law enforcement bodies now have scam compound investigations as active priorities. Interpol issued notices about major compound operations. Several countries have established task forces focused on cryptocurrency money laundering that these operations depend on.

Law enforcement in Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia have conducted raids on known compounds. Some have resulted in arrests of senior management. But the raids often come with warnings, giving operators time to relocate. Corruption means some raids are broadcast to targets in advance. Even successful raids are often temporary setbacks. Compounds shut down and restart in a different location within months.

The core challenge is that combating these operations requires simultaneous action across multiple countries with varying levels of law enforcement capacity and corruption. It requires tracking cryptocurrency through multiple exchanges and mixing services. It requires victim reporting despite their shame. It requires international coordination that's still in its early stages.

Some progress is happening. Countries are signing mutual legal assistance treaties. Tech platforms are removing recruitment ads more aggressively. Cryptocurrency exchanges are implementing better know-your-customer procedures. Countries are increasing penalties for human trafficking.

But these are incremental improvements to a problem that's rapidly scaling.

The Victim Impact: Financial and Psychological Devastation

The direct victims of pig butchering scams lose staggering amounts of money. Individual cases regularly involve losses exceeding

Victims experience severe psychological trauma. They fell in love with someone who doesn't exist. They built emotional connections that were entirely manufactured. They trusted someone who systematically exploited that trust. Many victims experience depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress after discovering the scam.

Some victims have taken their own lives after realizing they've lost their life savings to a scam. Others have become homeless. Relationships break up because victims can't bear to tell family members they've been scammed. Elderly victims sometimes lose retirement savings they can never replenish.

The second-order effects extend further. Family members become involved in covering losses. Friends and relatives become unwitting victims themselves when the scammer tries to extract more money through them. Communities lose trust in online dating and cryptocurrency more broadly. Legitimate businesses in the fintech and crypto space suffer reputational damage.

Law enforcement estimates that there's potentially $10-50 billion stolen annually by pig butchering scam operations globally. This places it among the most profitable forms of organized crime globally, exceeding drug trafficking in some regional markets.

What's remarkable is how normalized scams have become. In some countries, falling victim to a romance scam is so common that there's minimal social stigma. Entire online communities exist where victims share their stories and support each other. Dating app users now engage in due diligence like reverse image searches and video verification calls before investing emotional energy in new relationships.

The scams have essentially degraded trust in online dating as a medium.

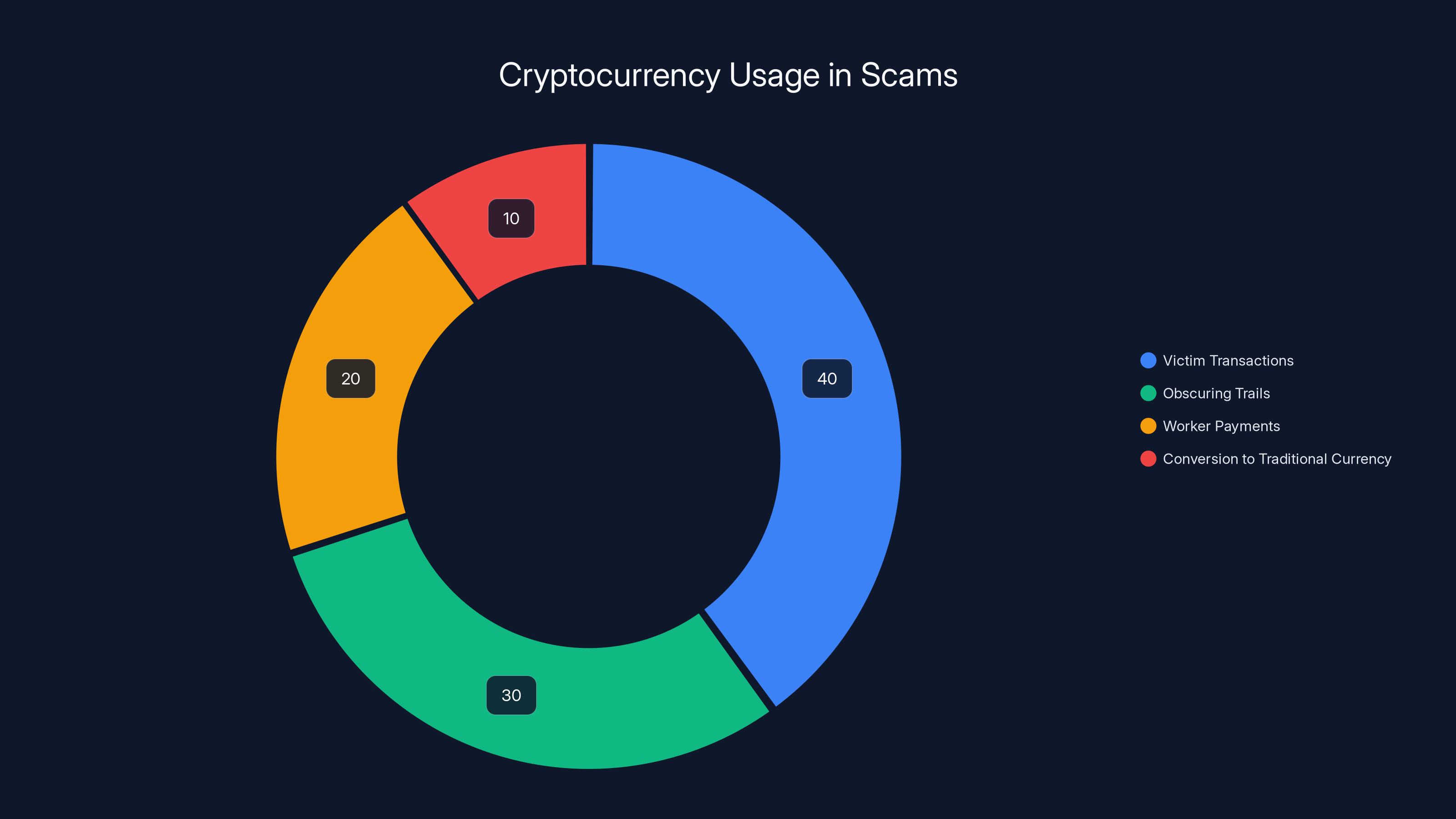

Estimated data shows that victim transactions account for the largest role in cryptocurrency-based scams, followed by methods to obscure transaction trails.

Compound Structure and Organization

The Boshang compound, like others in the region, operates with a clear organizational structure that mirrors a legitimate company.

At the top are the owners and shareholders. These are typically organized crime figures or criminal syndicates with connections to other illegal enterprises. They provide capital, strategic direction, and handle high-level relationships with government officials and rival criminal organizations. The owners are rarely present at the compound. They might visit occasionally to inspect operations and collect profits, but day-to-day management is delegated.

Below the owners is a senior management team. These individuals handle recruitment, acquisition of facilities, employee management policies, and coordination with affiliated criminal enterprises. They interface with the owners and represent the company in dealings with officials. In the Boshang compound, this layer included individuals like Amani, who sent motivational messages to the workforce.

The next level down includes team leads and department heads. These might oversee different scamming "teams," each focused on a specific victim demographic or scamming method. The Boshang org chart showed at least 5-6 major departments, each with multiple team leads beneath them. These individuals were responsible for meeting daily targets, addressing worker issues, and enforcing policies.

At the bottom are the actual scamming workers. These were further stratified by performance. Top performers had slightly better working conditions. Underperformers faced intensified monitoring and additional punitive fines.

There's also an administrative staff: people handling scheduling, payroll, facilities maintenance, security, food service. These roles are sometimes filled by workers who'd been promoted for loyalty or performance.

The compound itself typically occupies office space in a multi-floor building. Workers share dormitories with 5-6 people per room in bunk beds. The company maintains an office cafeteria, though workers often complain about food quality. There's a security apparatus to prevent escapes and entry by outsiders. Internet and phone connectivity are restricted, with workers using company-provided devices that are monitored.

The organizational structure is deliberate. It creates hierarchy and status differentiation, which keeps workers invested in compliance. A worker who performs well might get promoted to team lead, gaining slightly better status and treatment. This incentivizes pushing harder against your colleagues. The organization itself becomes a source of meaning and identity, even as it enslaves you.

Recruitment and Trap Mechanisms

The recruitment funnel is the lifeblood of these operations. Without a continuous stream of new recruits, compounds couldn't replace workers who escape, die, or become unusable.

Recruitment happens through multiple channels. Job advertisements on legitimate job sites. Messages on social media from fake recruitment accounts. Referrals from people who've been scammed into recruiting their friends. Some compounds maintain entire departments focused on recruitment.

The job advertisements are specifically designed to appeal to economically vulnerable people in low-income countries. The positions offer salaries that are aspirational, typically 2-3x what an equivalent local job would pay. The positions are described as remote or abroad-based, suggesting access to wealth and international opportunity. The ads are posted in local languages and target local job markets.

Once a potential recruit expresses interest, they're matched with a "recruiter" who's often a former scam compound worker now tasked with bringing in new people. This person has credibility because they're from the same background as the recruit. They might share their own story of success: "I came here two years ago, made good money, and bought property back home."

The recruiter guides the prospective worker through the process. There are visa requirements, which the "recruiter" handles. There are travel arrangements. Small upfront fees for processing and travel. By the time the recruit is traveling to their "new job," they've already spent

When they arrive at the compound and learn the truth, they've already crossed a psychological and financial threshold. The debt is real. The location is real. The organization is real. The consequences are real.

The trap mechanisms are multi-layered. Immediate confiscation of passports and documents. Placement in a remote location with limited communication outside. Introduction to the debt system that ensures financial escape is mathematically impossible. Forced participation in criminal activity that creates legal liability (if arrested, the worker faces charges for fraud, not trafficking). Threats against family members still in their home country.

Some compounds employ specific violence to discourage escape attempts. Workers learn that people who tried to leave were beaten. Some died. This information spreads rapidly through informal networks within the compound. A few examples are sufficient to create widespread deterrence.

The Cryptocurrency Connection

Pig butchering scams couldn't exist at their current scale without cryptocurrency. The technology enables the core criminal mechanics of these operations.

When a victim sends money through traditional banking channels, there are records. Bank transfers leave trails. Credit card charges can be disputed and reversed. Regulatory bodies can freeze accounts. Law enforcement can subpoena banks for transaction records. Traditional banking is essentially a recorded ledger of who sent what to whom.

Cryptocurrency sidesteps all of this. A victim purchases Bitcoin or Ethereum through a regulated exchange. They send it to a wallet address provided by the scammer. The transaction is permanent and irreversible. The wallet address is pseudonymous. The person who created it is unidentifiable through the blockchain alone.

Once the money is in the wallet, it can be moved through additional wallets to obscure the trail. It can be sent to mixing services that combine it with other cryptocurrencies, further obscuring its origin. It can be converted back to traditional currency through unregulated exchanges in countries with weak financial oversight.

This is the essential function of cryptocurrency in scam operations: it decouples money transfer from regulatory oversight. A victim can send $100,000 and the transaction is permanent and untraceable at scale.

Furthermore, cryptocurrency enables workers in scam compounds to be paid. The compound receives money in crypto. They can pay worker salaries in cryptocurrency, which workers can convert to local currency at underground exchanges. This sidesteps banking records of how workers were compensated for their criminal work.

Some major cryptocurrencies have begun implementing better anti-money-laundering features. Exchanges have improved know-your-customer procedures. But the ecosystem remains fundamentally designed for pseudonymity. New cryptocurrencies with privacy-focused features are launched regularly specifically to circumvent these controls.

Law enforcement agencies are gradually building expertise in cryptocurrency tracing. Some blockchain transactions can be partially traced by analyzing patterns and following coins to regulated exchanges where people cash out. But this requires significant investigative resources and technical expertise.

The cryptocurrency industry's relationship with scam compounds is complicated. Most legitimate exchanges prohibit money laundering. But the scale of the problem and the financial incentives mean that enforcement remains inconsistent. And the existence of decentralized exchanges and privacy coins means there will always be pathways for criminal organizations to move money with reduced oversight.

Escape and Rescue Operations

Some workers manage to escape. It's dangerous, expensive, and often involves help from law enforcement or anti-trafficking organizations.

Mozahir, the whistleblower, managed to escape and contact journalists while still nominally employed at Boshang. He had access to communication tools that allowed him to leak documents. He had the knowledge and education to understand what he was seeing and reach out to external contacts. Not all workers have these advantages.

When workers escape, they face immediate practical challenges. They're in a foreign country with no money and no documents. They don't speak the local language. They might not even know which country they're in. Compound security attempts to find them. The organization marks them as liabilities who could inform on operations.

Law enforcement rescue operations are complicated. They require jurisdiction, which is difficult when compounds cross borders. They require coordination between multiple agencies across countries. They require knowing where to look. Many compounds deliberately operate from locations that are difficult to access.

Some workers have been rescued through tips from family members who became suspicious when they stopped communicating. Others have been found by law enforcement during raids. Some have been rescued by anti-trafficking NGOs that operate in the region and have informants within the criminal ecosystem.

Once rescued, workers face additional challenges. Many have been in the country illegally. They might face charges for their role in scamming operations, even though they were coerced into the work. They're traumatized. They often have significant debt they believe they still owe. They're separated from the compound but not truly free.

Anti-trafficking organizations work to provide legal assistance, psychological counseling, and community reintegration. Some countries have amnesty programs that shield trafficking victims from prosecution for crimes they were forced to commit. But the legal and practical support is inconsistent across the region.

Future Evolution and Emerging Threats

Scam compounds are evolving. As law enforcement increases pressure in some regions, operations are relocating and adapting.

One emerging concern is the use of artificial intelligence to automate parts of the scamming work. Instead of human workers building relationships with victims, AI chatbots could maintain thousands of simultaneous fake relationships. Early scammers have experimented with AI to reduce labor costs. If this technology becomes sophisticated enough, it could dramatically increase the efficiency of scamming operations while reducing the need for enslaved workers.

Another emerging threat is the expansion of scam compounds into regions beyond Southeast Asia. There's evidence of operations in parts of Africa, South America, and Eastern Europe. Some have relationships with traditional organized crime networks in those regions.

The sophistication of deepfake technology poses another risk. Currently, scammers use stolen photos and stolen videos to represent fake identities. As deepfakes become more convincing, it becomes harder for victims to verify that the person they're talking to is real. Scammers could maintain dozens of fake video identities simultaneously, making verification nearly impossible.

There's also expansion into non-cryptocurrency scams. As law enforcement has targeted cryptocurrency money laundering, some compounds are experimenting with traditional wire transfers, money mules, and physical cash movement. This makes the money flow slower and more cumbersome, but potentially reduces law enforcement visibility.

Politically, there's growing pressure on Southeast Asian governments to address these operations. International entities like the US State Department explicitly name scam compound prevalence as a human trafficking concern. This creates incentive for regional governments to take action. But without economic investment in developing legitimate employment alternatives and addressing corruption, enforcement alone won't solve the problem.

What Can Actually Stop This

Stopping pig butchering scams at scale requires action across multiple domains simultaneously.

First, there needs to be serious law enforcement action. This means international task forces with dedicated resources. It means shared intelligence between countries. It means countries being willing to prosecute organized crime figures involved in scam compounds, not just arrest low-level workers. It means coordinating arrests across multiple countries simultaneously so that when one compound shuts down, the organization doesn't just relocate.

Second, there needs to be regulation of the cryptocurrency ecosystem that makes money laundering more difficult without completely destroying privacy-friendly technologies. This is a difficult balance, but it's necessary. Better customer identification at exchanges. Better monitoring of wallet movements. Better coordination with law enforcement when large sums move through regulated platforms.

Third, there needs to be investment in victim support and recovery. Many victims don't report because they feel shame or blame themselves. Victim support organizations need funding to reach people who've been scammed and help them access law enforcement and psychological support.

Fourth, there needs to be economic investment in the regions where workers are recruited. As long as legitimate employment opportunities are scarce and wages are low, recruitment will remain easy. This isn't a quick fix. It requires investment in education, infrastructure, and economic development. But without addressing the desperation that makes people vulnerable to recruitment, law enforcement will always be fighting a losing battle.

Fifth, there needs to be education. Potential victims need to understand how these scams work. Potential recruits need to understand the reality of scam compound employment. This education needs to be culturally sensitive and available in relevant languages.

Finally, there needs to be pressure on tech platforms. Dating apps, social media platforms, and job sites are used extensively for recruitment and victim contact. These platforms have the ability to identify and remove fake accounts, recruitment ads, and suspicious scamming activity. They've made progress, but more aggressive action is needed. When a platform makes recruitment or scamming harder, that directly reduces the scale of these operations.

The intersection of all these factors is where real progress can happen. No single intervention will stop scam compounds. But a coordinated international approach combining law enforcement, regulation, development, and technology platform accountability could significantly reduce their scale.

FAQ

What exactly is a pig butchering scam?

A pig butchering scam is a type of confidence fraud where a scammer builds trust with a victim over weeks or months, typically by posing as an attractive woman, successful businessman, or investment advisor through dating apps, social media, or messaging platforms. Once trust is established, the scammer convinces the victim to send money, usually under the guise of cryptocurrency investment, emergency funds, or immigration fees. The term comes from the concept of raising an animal well before slaughter. The scam is often orchestrated from criminal compounds in Southeast Asia where enslaved workers are forced to carry out the fraudulent work.

How do scam compounds force workers to stay?

Scam compounds use multiple mechanisms to control workers: confiscating passports and travel documents, placing workers in remote locations far from home, implementing a debt-based system where fines perpetually exceed earnings, threatening violence against escapees or family members, and requiring workers to participate in illegal activity that creates legal liability. The combination of physical constraints and psychological manipulation makes escape extremely difficult. Most workers cannot simply walk away because they lack documents, don't know their location relative to help, and believe they'll face violent consequences for attempting escape.

How much money do pig butchering scams steal globally?

Estimates suggest pig butchering scams steal

Who typically becomes a victim of these scams?

Victims come from diverse backgrounds and income levels, though certain demographics are more vulnerable. Lonely individuals, particularly men seeking romantic relationships, are frequently targeted. Entrepreneurs and business owners interested in investment opportunities are also common victims. Victims tend to be people who are emotionally vulnerable, seeking connection, or interested in financial opportunities. The scammers are sophisticated at identifying emotional triggers and vulnerabilities. Victims can lose anywhere from thousands to over $1 million in a single scam.

What is being done to stop these operations?

Measures being implemented include increased international law enforcement coordination, cryptocurrency exchange regulations requiring better customer identification, targeted raids on known scam compounds in Southeast Asia, victim support organizations offering psychological and legal assistance, and tech platform improvements to remove scam recruitment ads and fake accounts. However, progress is slow because the problem requires simultaneous action across law enforcement, cryptocurrency regulation, technology platforms, victim support, and economic development in vulnerable regions. Individual countries vary significantly in their commitment and capacity to address the issue.

Why is cryptocurrency so important to these scams?

Cryptocurrency is essential to pig butchering scams because it enables money transfer that's permanent, irreversible, and difficult to trace compared to traditional banking. When a victim sends traditional bank funds, there are regulatory records and the transaction can potentially be reversed. Cryptocurrency transactions are pseudonymous and final. Money can be moved through multiple wallets and mixing services to obscure its trail, making it nearly impossible for law enforcement to recover stolen funds. Additionally, cryptocurrency enables criminals to pay workers in the compound while avoiding traditional banking records that might reveal the illegal nature of their compensation.

The leaked documents from the Boshang compound represent an unprecedented window into an industry that's fundamentally changed organized crime in the 21st century. These aren't small-time con artists working independently. They're industrialized criminal enterprises that combine modern technology, psychological manipulation, human trafficking, and cryptocurrency to steal tens of billions annually.

What's most striking about the leaked materials is how mundane the operations appear. There are schedules and quotas and performance reviews. There's corporate communication and team motivation. If you didn't know the context, you might mistake these for a legitimate technology company. That ordinariness is precisely what makes it terrifying. The scam compounds have perfected the art of making slavery and fraud seem like just another job.

Mohammad Muzahir's decision to leak these materials from inside the compound was extraordinarily courageous. He risked everything to expose operations that employ hundreds of thousands of forced laborers. His information has already begun to influence law enforcement responses and regulatory approaches globally.

But one whistleblower and one leaked compound won't stop an industry generating tens of billions annually. What's needed is sustained international pressure: coordinated law enforcement action across borders, stricter cryptocurrency regulation, investment in the regions where workers are recruited, support for victims, and accountability from technology platforms that enable recruitment and scamming.

The scam compounds will evolve. They'll migrate to new locations, adopt new technologies, and develop new scamming methodologies. But the fundamental structure they depend on—vulnerable workers in desperate circumstances, lack of law enforcement capacity in the regions where they operate, cryptocurrency that enables money movement, and victim shame that prevents reporting—these factors persist.

Addressing pig butchering scams at scale requires recognizing them not as a distant Southeast Asian problem, but as a global organized crime threat with direct consequences for victims worldwide. It requires investment and coordination that has only recently begun. And it requires understanding that behind every scam is a person trapped in a compound, forced to defraud others, living in conditions resembling slavery. That human cost is what should drive action.

Key Takeaways

- Pig butchering scams steal 200,000-$1 million on average.

- Hundreds of thousands of workers are enslaved in Southeast Asian scam compounds through recruitment deception, passport confiscation, and debt bondage systems designed to make escape mathematically and physically impossible.

- The Boshang compound whistleblower leak revealed that enslaved workers generating 200 after base salary and systematic fines.

- Scam compounds operate with corporate-like hierarchies, performance metrics, and psychological manipulation tactics that combine motivational messaging with explicit threats to maintain worker compliance and psychological investment in the organization.

- Cryptocurrency is essential to these scams because it enables permanent, untraceable money transfer compared to traditional banking, with stolen funds moved through multiple wallets and mixing services to prevent law enforcement recovery.

Related Articles

- From Bitcoin Heist to Cybersecurity: A Hacker's Path to Redemption [2025]

- Target Data Breach 2025: 860GB Source Code Leak Explained [2025]

- SandboxAQ Executive Lawsuit: Inside the Extortion Claims & Allegations [2025]

- The Viral Food Delivery Reddit Scam: How AI Fooled Millions [2025]

- Condé Nast Data Breach 2025: What Happened and Why It Matters [2025]

- Best Cybersecurity Journalism 2025: Stories That Defined the Year

![Inside Pig Butchering Scam Compounds: How Forced Labor Fuels Cybercrime [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/inside-pig-butchering-scam-compounds-how-forced-labor-fuels-/image-1-1769514071257.jpg)