The Memory Crisis That Won't End: Understanding Kioxia's 2026 Shortage

We're deep into an unprecedented memory shortage, and the situation is getting worse before it gets better. Kioxia, the Japanese memory manufacturer spun off from Toshiba, just dropped a bombshell: their entire manufacturing capacity is sold out through the end of 2026. This isn't just a blip on the radar—it's a structural problem reshaping the entire storage market.

The memory industry is in what Kioxia's managing director calls a "high-end and expensive phase." What does that actually mean? It means if you're shopping for an SSD right now, you're paying top dollar. It means enterprise data centers are getting squeezed. It means the GPU shortage of 2021 looks quaint in comparison.

But here's what's really interesting: this shortage isn't accidental. It's driven by something unprecedented—a frenzy of AI data center investment that shows no signs of slowing down. Companies racing to build AI infrastructure are hoarding memory chips like they're going out of style. Because in their minds, they are. The competitive pressure to deploy AI is so intense that manufacturers can barely keep up.

In this article, we're diving deep into why Kioxia can't make enough memory, why that matters to you personally, and what the timeline looks like for actual relief. We'll explore the economics behind the shortage, the manufacturing constraints that won't disappear overnight, and what you can do about it if you need storage right now.

TL; DR

- Kioxia's entire 2026 capacity is already sold out to data centers and enterprise customers, with no relief in sight

- AI infrastructure investment is the culprit, driving unprecedented demand for memory chips and SSDs

- SSD prices won't drop significantly until at least 2027, with higher-capacity drives hit hardest

- Secondary storage solutions like adding M.2 slots or external drives are smart workarounds for consumers

- Manufacturing constraints are real, requiring years to build new capacity and achieve profitable yields

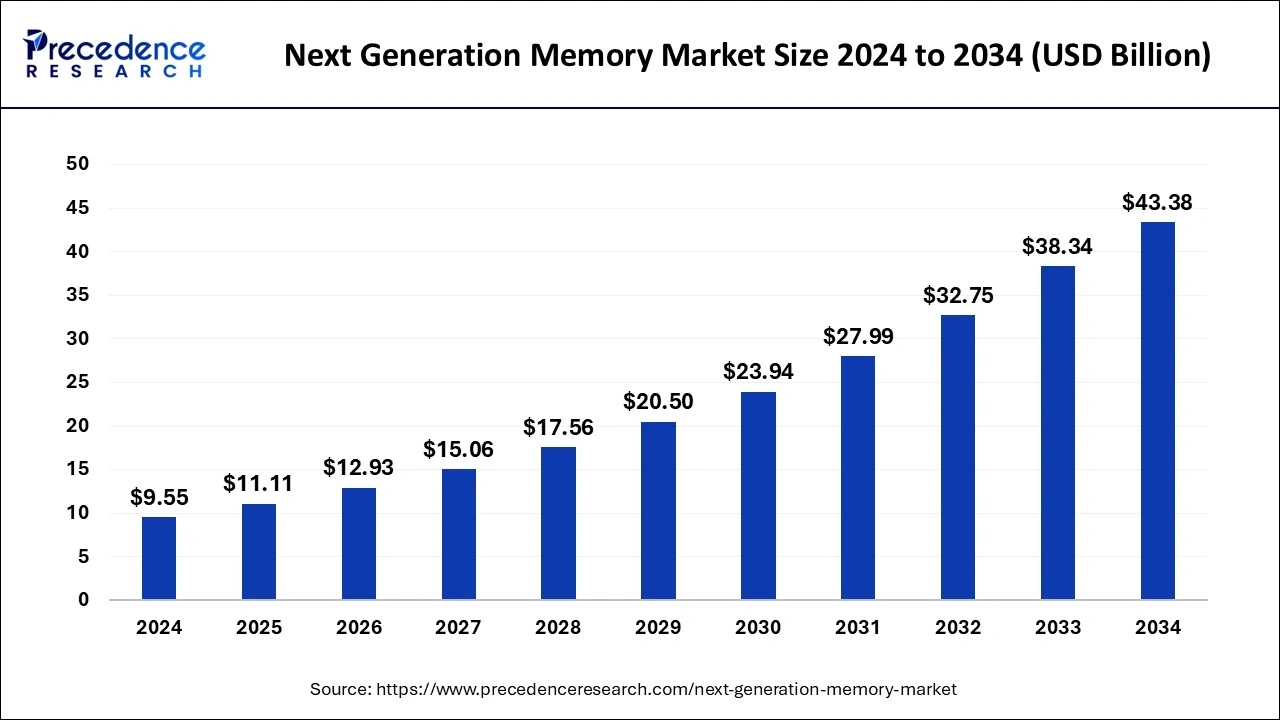

SSD prices for 1TB, 2TB, and 4TB drives are projected to decrease by 2028, with 2TB drives experiencing the most significant drop. Estimated data based on historical trends.

What Happened to the Memory Market in 2024-2025?

Just a few years ago, the memory market looked dramatically different. The 2020-2021 chip shortage hit every sector—from gaming consoles to cars to data centers. Prices spiked. Lead times stretched to months. It seemed unsustainable.

Then something changed. By 2023, the shortage eased. New fabrication plants came online. Supply chains normalized. Prices actually started dropping. For the first time in years, consumers could buy reasonably priced SSDs and RAM without hunting for deals.

That window closed in late 2024. The culprit wasn't a natural disaster or geopolitical crisis. It was the explosive growth of generative AI data centers.

Companies like Open AI, Google, Meta, and Microsoft suddenly needed memory chips in quantities that dwarfed anything the industry had seen before. Training large language models requires massive GPUs. Inference at scale requires enormous amounts of VRAM. Every new AI service launch created another wave of demand.

The manufacturing capacity that seemed adequate six months earlier became laughably insufficient. Kioxia, Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron all reported record profits not because they were producing more, but because they were selling every single chip they made at premium prices.

SSD prices are expected to peak around 2026 due to AI demand, with gradual price relief starting in 2027 and more significant drops by 2028. Estimated data.

The AI Data Center Paradox: Why Companies Keep Buying

Here's the twisted logic driving this shortage: the companies investing in AI infrastructure are caught in a competitive arms race with no finish line. They can't afford to stop buying memory chips because the moment they do, a competitor might leap ahead.

Shunsuke Nakato, Kioxia's managing director, explained this dynamic with stunning clarity. He said there's "a sense of crisis that companies will be eliminated the moment they stop investing in AI." This isn't hyperbole. It's the reality of the current market. Open AI, Google, Meta, Microsoft—they're all locked in a race to deploy the most capable AI systems. Each generation requires more compute. More compute requires more memory.

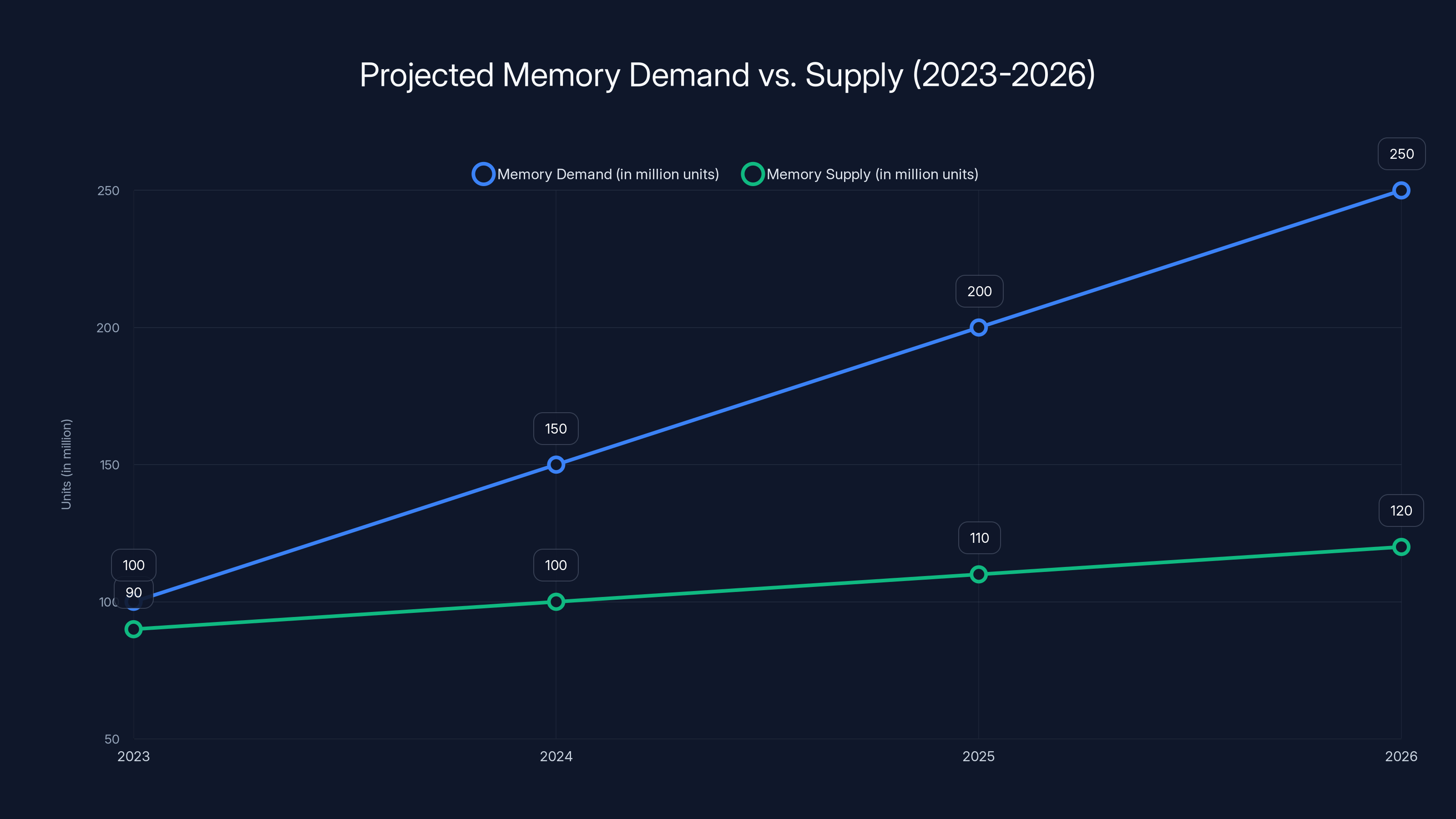

This creates a perpetual demand problem. Even if the industry suddenly doubled production capacity tomorrow, there would still be buyers for every single chip. The competitive dynamics are so intense that no company wants to be the one caught short when the next breakthrough happens.

It's different from previous shortages, which were typically driven by unexpected supply disruptions (hurricanes, fires, pandemics). This shortage is demand-driven, and the demand source shows no signs of weakening. As long as generative AI remains a priority for major tech companies, memory demand will exceed supply.

Why Kioxia Specifically Can't Keep Up

Kioxia is one of the world's largest memory manufacturers, along with Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron. But size doesn't equal unlimited capacity. Manufacturing memory chips is one of the most capital-intensive industries on Earth.

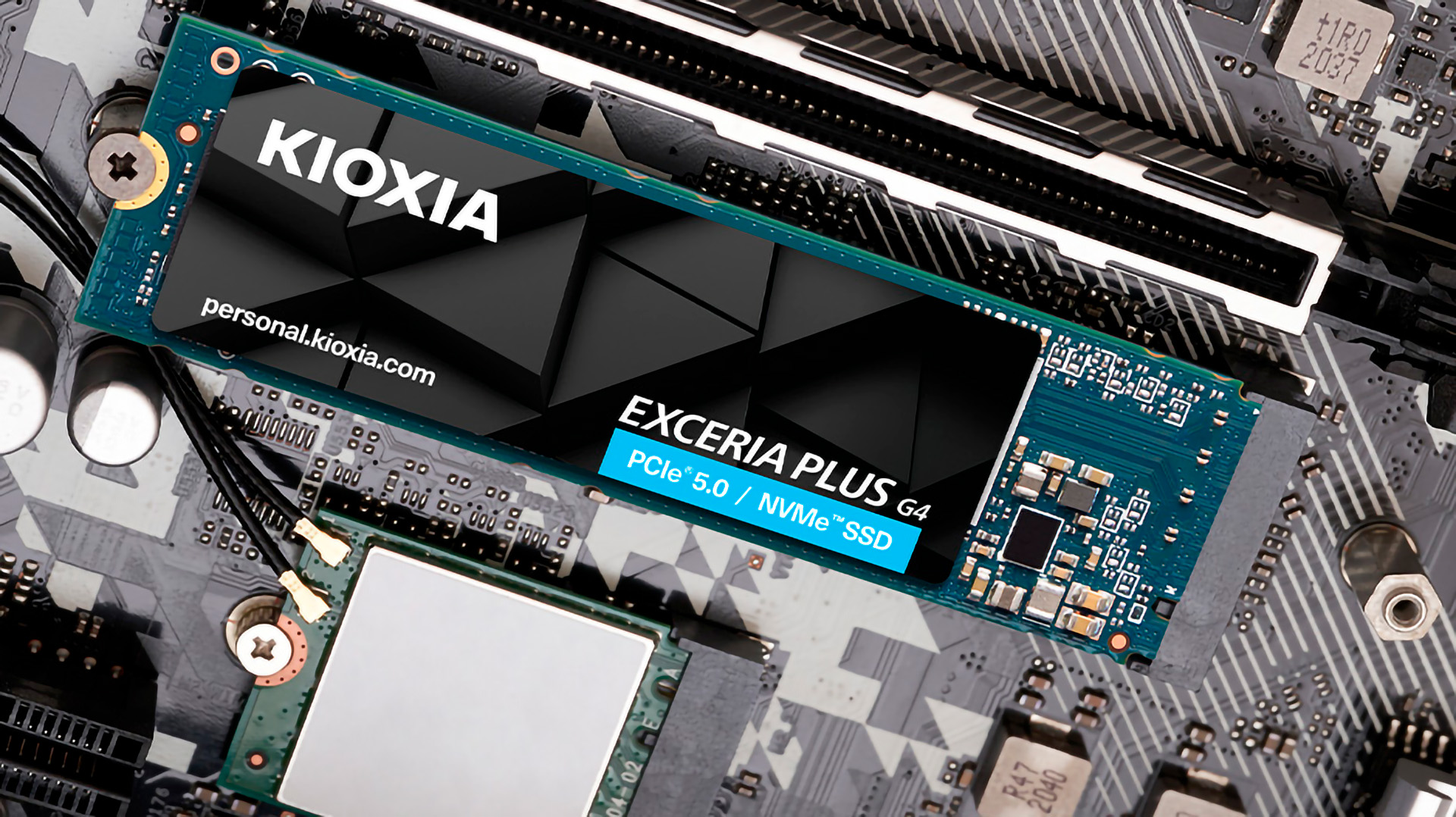

Kioxia operates two main fabrication plants: Yokkaichi in Japan and Kitakami, also in Japan. These aren't small operations—they're sprawling complexes with thousands of workers and equipment that costs billions to install. But even with these two massive facilities, Kioxia is maxed out.

The company is working to increase yield rates at Yokkaichi (meaning getting more usable chips from each production run) and ramping up production at Kitakami. But here's the constraint that everyone forgets: even when you build a new fab or expand capacity, it doesn't immediately translate to more chips you can actually sell.

Manufacturing semiconductor memory requires hitting extremely tight tolerances. When a new production line starts up, yields are often terrible—maybe 20-30% of chips pass quality control. It takes months or even years to optimize processes and get yields up to 70-80% or higher. Until that happens, the fab isn't profitable, and certainly isn't helping solve the shortage.

Kioxia expects Kitakami to reach "full-scale mass production" in 2026, but that's the company's optimistic timeline. Reality is often messier. Equipment doesn't arrive on schedule. Process optimization takes longer than expected. Yields plateau at disappointing levels.

Estimated data shows a growing gap between memory demand and supply from 2023 to 2026, driven by AI data center investments.

Manufacturing Reality: Why Building Capacity Takes Years

If Kioxia, Samsung, and others are so desperate to meet demand, why can't they just build new factories? The answer is brutally simple: it takes forever and costs an astronomical amount of money.

Constructing a single semiconductor fabrication plant runs

The timeline is equally brutal. From groundbreaking to first production: 3-5 years minimum. From first production to profitable production: another 2-3 years. So if a company breaks ground on a new fab today, they might not see real volume production until 2029 or 2030.

That's why previous chip shortages took years to resolve. The 2021 shortage didn't actually ease because suppliers suddenly had way more capacity. It eased because demand normalized and existing fabs ran better. The massive new capacity investments from that era are still coming online now.

Manufacturers also have to think about market risk. If you spend $20 billion building a new fab and the market cools before it's online, you're stuck with expensive assets and no customers. This happened in previous cycles—companies over-invested in capacity, demand dropped, and they ended up discounting heavily just to sell through inventory.

The Structure of the Shortage: Enterprise vs. Consumer

Kioxia makes both enterprise SSDs (for data centers and servers) and consumer drives (for laptops, desktops, and gaming systems). The shortage hits both, but enterprise customers get priority.

Here's why: enterprise customers spend way more money per drive. They buy 10,000 drives at a time. They have multi-year contracts. They're willing to pay premium prices to ensure they get capacity when they need it. Consumer customers? They buy one drive at a time, price-shop aggressively, and look for deals.

When Kioxia's manufacturing output is limited, the rational business decision is to allocate as much as possible to enterprise customers. They bring in more revenue per unit. They're more reliable customers. Enterprise contracts already signed mean predictable, high-volume orders.

This means consumer SSDs get squeezed at the allocation level. Retailers have to choose: wait months for new stock or pay higher wholesale prices. They pass these costs to consumers. Prices don't just go up a little—they go up significantly, especially for higher-capacity drives.

Our research into retail pricing shows that drives in the 2TB and 4TB range have seen more severe price increases than 1TB models. This makes sense—data center workloads need massive storage capacity, so enterprise customers specifically demand the high-capacity products. When you bid up the price on those drives, it has cascading effects through the retail channel.

If you want affordable storage in 2026, your best bet might actually be purchasing 1TB drives and stacking multiple drives in additional M.2 slots, rather than buying a single large capacity drive.

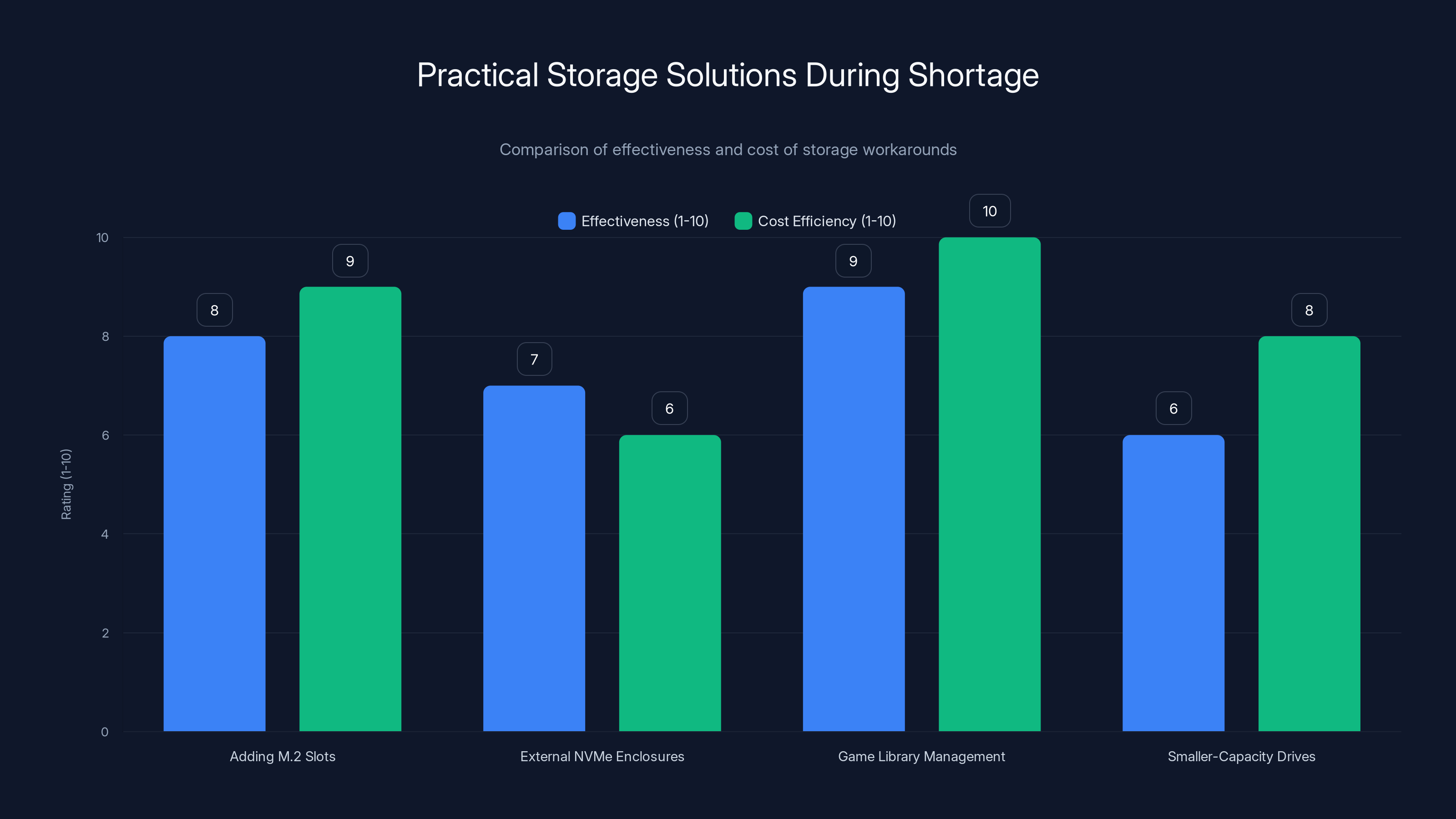

Game library management is the most cost-efficient solution, while adding M.2 slots is highly effective if available. Estimated data based on typical user scenarios.

The Price Dynamics: Why Expensive Drives Get Hit Hardest

Memory markets operate on the principle of supply and demand, but with a fascinating twist. When capacity is scarce, prices don't rise evenly across the board. They rise more aggressively for products with higher margins and higher perceived demand.

A 2TB SSD uses more memory than a 1TB drive, obviously. But the price difference isn't linear. The 2TB drive doesn't cost double—it costs maybe 1.7x to 1.8x. That's because the cost is split between memory and everything else (controller chip, PCB, firmware, packaging, testing, logistics).

When memory gets scarce, manufacturers have an incentive to produce more high-capacity drives because that's where the profit opportunity is. They'd rather sell one 4TB drive than four 1TB drives—same amount of memory, less manufacturing complexity.

But retail demand doesn't work that way. Consumers who need one drive and have a budget constraint buy the largest capacity they can afford. Enterprise customers who need huge storage capacity want the highest capacity drives. So when memory gets scarce, the entire market is pushing up demand for 2TB, 4TB, and 8TB drives specifically.

This creates a squeeze: manufacturers want to make high-capacity drives for profit reasons, customers want to buy them for capacity reasons, but they all want them at the same time. The result? Prices skyrocket for exactly what everyone needs most.

When Will Relief Actually Come? Timeline and Scenarios

Kioxia says manufacturing capacity will be sold out through the entire 2026 calendar year. That means the earliest realistic date for any meaningful relief is January 2027. But that assumes:

- AI demand doesn't accelerate further (unlikely assumption)

- New capacity comes online on schedule (historically rare)

- Yields improve as expected (frequently delayed)

- No new geopolitical disruptions (forever-uncertain)

The most optimistic scenario: Kitakami reaches full production in late 2026, adding maybe 20-30% more capacity. Enterprise customers still get priority, so consumer prices might drop 10-15% by mid-2027. The sweet spot—prices returning to pre-2024 levels—probably doesn't happen until 2028 or 2029.

The realistic scenario: Kitakami ramps slower than expected. Yields stay lower than projections through 2027. AI demand stays strong. Consumer SSD prices remain elevated through 2027, with gradual improvement starting in 2028. High-capacity drives remain particularly expensive.

The pessimistic scenario: A new AI application emerges that requires even more memory (quantum AI? neuromorphic computing?). Geopolitical tensions disrupt supply from Japan or South Korea. A major fab has a catastrophic failure. In these cases, the shortage extends well into 2028 or beyond.

What's most likely? The realistic scenario with elements of pessimism. Relief comes slowly, partially, and incompletely.

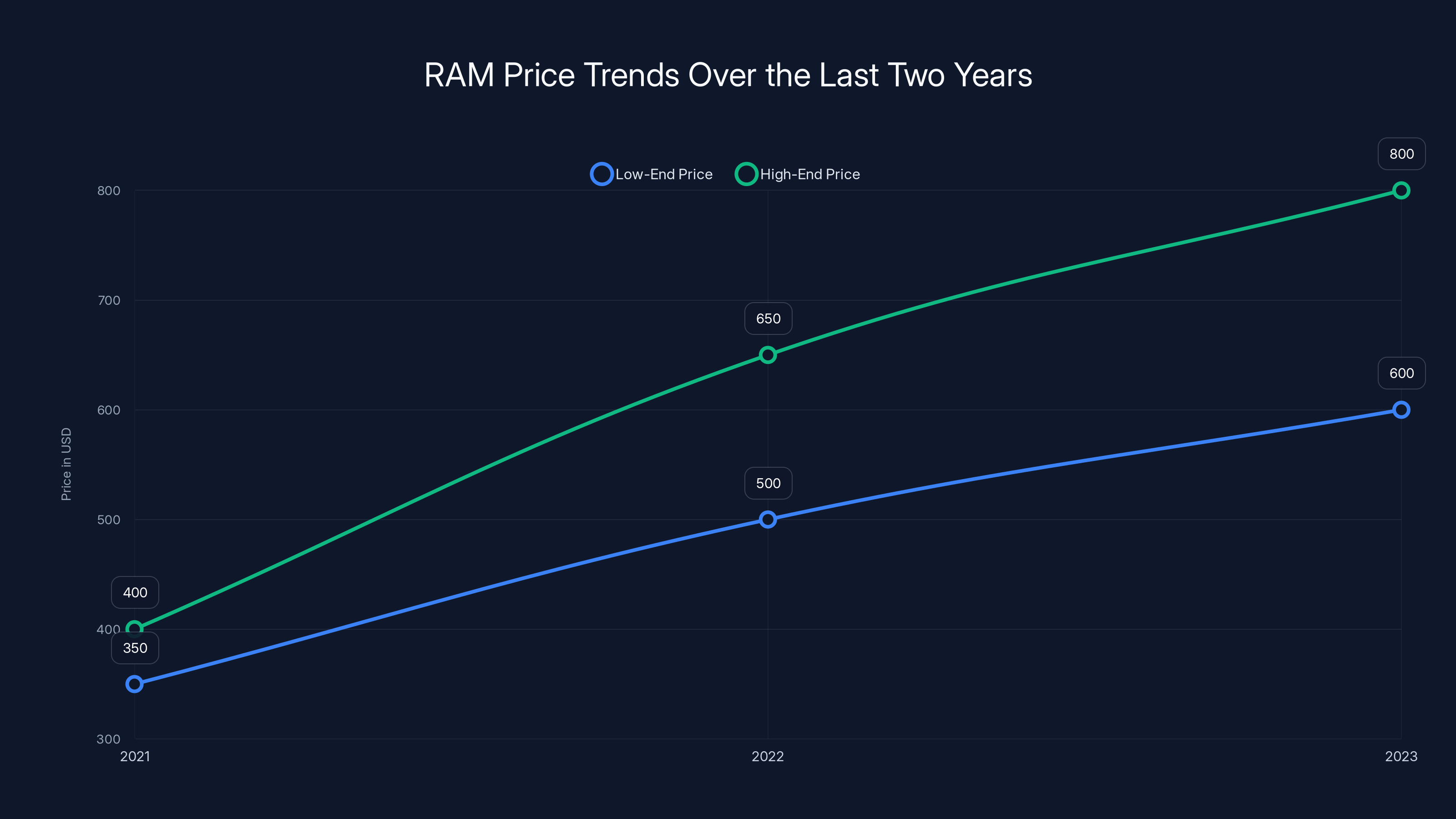

RAM prices have significantly increased over the past two years, with 64GB DDR5 kits rising from

Geographic Constraints and Geopolitical Risk

Here's something most people don't think about: memory manufacturing is geographically concentrated. Kioxia is in Japan. Samsung and SK Hynix are in South Korea. Micron's main operations are in the US, but it has significant operations in Japan. TSMC, the world's largest semiconductor manufacturer, is in Taiwan.

Taiwan is a geopolitical flashpoint. A military conflict that disrupts TSMC production would crater the entire semiconductor industry. South Korea's relationship with North Korea creates periodic tensions. Japan faces seismic risks and has experienced multiple factory disruptions from earthquakes.

This geographic concentration is actually one reason the memory shortage persists. There's not a competitive alternative supply base. If Kioxia has a problem, there's no easy way to shift production to another region. Samsung and SK Hynix are maxed out. Micron can't suddenly produce memory to replace what Kioxia makes.

Long-term, this geographic risk will probably drive investment in more diversified production. But that takes years. For now, we're dependent on manufacturing capacity in a handful of countries, in a handful of facilities, with massive geopolitical exposure.

It's one reason why governments (the US, EU, Japan, South Korea) are suddenly interested in subsidizing semiconductor manufacturing. They realize that depending on a single region for critical compute infrastructure is a national security vulnerability.

Enterprise Data Centers: The Real Shortage Drivers

When we talk about "memory shortage," most consumers think about difficulty buying an SSD for their gaming PC. But the real story is in enterprise data centers.

Companies deploying large language models need to build infrastructure. They're not buying one GPU. They're buying thousands. They're not buying storage once. They're building massive storage systems. A single large-scale AI model training run might require terabytes of DRAM just for the working set, plus terabytes of fast NVMe storage for data loading.

Google, Meta, Open AI, and Microsoft are all in this market simultaneously. They're all trying to build out massive data center capacity. They're all buying memory chips. They're all willing to pay premium prices because the business case for AI infrastructure is so strong.

Think about it from their perspective: if you can deploy an AI service that generates millions of dollars in revenue, you'll spend 20% of that revenue on data center infrastructure without blinking. That's a great return on investment. So they bid aggressively for memory, and they get it because they can afford to outbid consumer demand.

This is where Nakato's comment about "companies will be eliminated the moment they stop investing" makes sense. If Open AI pauses GPU purchases to save money, but Google keeps buying, then Google might end up with a competitive advantage. So nobody wants to be the one who blinks first.

Memory prices spiked during the 2020-2021 chip shortage, eased in 2023, but surged again in 2024-2025 due to AI-driven demand. (Estimated data)

How to Survive the Shortage: Practical Workarounds

If you need more storage right now and the prices are making you wince, you have options that don't involve waiting for the shortage to end or paying premium prices.

Adding M.2 Slots: Most modern desktops have at least two M.2 storage slots. Many have three. Check your motherboard spec sheet. If you have an open slot, you can add another drive without removing your existing one. This is the cheapest option if you have the physical slots available.

Using External NVMe Enclosures: If your PC doesn't have extra M.2 slots, you can buy an external USB-C or Thunderbolt enclosure and run an NVMe drive through that. It's not quite as fast as internal storage (bottlenecked by USB/Thunderbolt speeds), but modern USB 3.2 and Thunderbolt 4 are still very fast—much faster than old external drives or USB sticks.

Secondary M.2 Performance Considerations: Here's a technical detail people miss: sometimes a secondary M.2 slot is slower than the primary one. This happens when the primary slot connects to PCIe lanes built into the CPU (usually PCIe 4.0 or 5.0), while a secondary slot uses PCIe lanes from the chipset (might be PCIe 3.0). For gaming and most applications, this doesn't matter much. A PCIe 3.0 drive is still fast enough. But if you're doing heavy video editing or data-intensive work, check your motherboard documentation.

Game Library Management: If your shortage problem is specifically about game storage, most launchers (Steam, Epic, etc.) let you install games across multiple drives and move them between drives without re-downloading. You can keep frequently-played games on your fast primary drive and move older games to a secondary drive. This is almost zero-cost and lets you manage the shortage psychologically even if you can't physically add more storage.

Embrace Smaller-Capacity Drives: Buy two 1TB drives instead of one 2TB drive. You get the same storage, better redundancy (one can fail and you still have data), better performance (two drives can handle IO concurrently), and often spend less money. It's a genuinely better solution, not a compromise.

The Role of Market Consolidation in the Shortage

There are only four major memory manufacturers left: Kioxia, Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron. This consolidation is actually a problem during shortages.

In a fragmented market with many competitors, when demand spikes, you can shift orders to smaller manufacturers or regional players. But when there are only four players and they're all maxed out, there's nowhere to go. You're stuck waiting for the big four to increase capacity.

This consolidation happened over decades, driven by economics. Making memory chips is a capital-intensive, low-margin business. Smaller players can't compete. They eventually get acquired or go out of business. Now we're left with an oligopoly, and oligopolies are slow to respond to demand spikes.

Interestingly, this is starting to push some companies toward vertical integration. Microsoft is investing in chip manufacturing. Apple has moved to custom silicon for phones and tablets. Meta and Google are developing custom AI chips. If these companies succeed, they'll reduce their dependence on Kioxia and Samsung, but they'll also remove demand that currently supports those manufacturers' expansion plans.

It's a shifting landscape, and the changes won't happen overnight.

The Ripple Effects Beyond SSDs: RAM Market Impact

While this article focuses on storage, the memory shortage impacts RAM even more dramatically. Memory is memory—whether it's DRAM for RAM or NAND flash for SSDs, it comes from the same manufacturing facilities.

RAM prices have gone up even faster than SSD prices. A 64GB DDR5 kit that cost

The dynamic is the same: AI data centers need massive amounts of DRAM for running inference workloads. When a language model is serving requests, it needs fast memory to store activations and intermediate results. A single inference server might have 256GB-512GB of DRAM. Scale that across thousands of servers in a data center, and you need manufacturing capacity that simply doesn't exist.

Consumer impact: building a gaming PC or workstation suddenly requires choosing between high-end performance (expensive RAM) and budget consciousness. Many builders are waiting for prices to drop, which means the current upgrade cycle is slower than usual.

Manufacturing Efficiency: Yield Rates and Production Reality

Here's the crucial detail that most people miss when they think about expanding manufacturing capacity: producing the chips is only part of the problem. Making chips that actually work is another problem entirely.

When a new production line starts up, yields—the percentage of chips that pass quality testing—are often terrible. You might produce 1,000 chips and have only 200 pass testing. That's a 20% yield. Every week you can optimize the process, tweak temperatures and pressures, refine the chemical mixtures, and gradually improve. Maybe after three months you're at 40% yields. After six months, 60%. After a year, 75%.

During that ramp period, you're producing chips, but not profitably. You're burning money. The equipment is running, but most of the output is waste. This is why new capacity doesn't suddenly triple production—it ramps slowly as yields improve.

Kioxia and other manufacturers are dealing with this right now. They're probably operating Kitakami, but at yields that are well below optimal. They're producing some chips, but not at the rate they could eventually reach once processes are refined.

This is actually one reason the shortage will persist even as new capacity comes online—new capacity requires a ramp period, and during that ramp, the benefit is much smaller than people expect.

Price Predictions: What the Data Actually Shows

If we look at historical SSD prices and apply realistic assumptions about capacity growth and yield improvements, what emerges?

For 1TB drives: Expect prices to remain roughly flat through 2026 and possibly drop slightly (maybe 10%) in 2027-2028. The current market rate of

For 2TB drives: These are hit hardest by the shortage. Current market rate of

For 4TB and larger: These ultra-high-capacity drives will probably remain the most expensive for longest, simply because enterprise demand is highest here. Maybe $200-250 stays the baseline for a 4TB drive through 2027, with price drops coming in 2028-2029.

These predictions assume no major disruption (geopolitical conflict, economic depression, new AI demand spike). They're educated guesses based on historical supply-demand dynamics, not guarantees.

The bottom line: if you can defer a storage purchase until 2028, you'll probably get better prices. If you need storage in 2025-2026, brace for premium pricing.

What Consumers Should Do Right Now

Given all of this, what's the actual advice for someone who needs storage?

If you can wait: Do it. Waiting until 2027-2028 gives you better pricing and wider availability. There's no shame in deferring an upgrade.

If you need storage now: Buy the most capacity-efficient combination. That often means multiple smaller drives rather than one large drive. A pair of 1TB drives might give you the same capacity at lower total cost than a single 2TB drive in this shortage environment.

If you have secondary M.2 slots: Use them. Adding a secondary 1TB drive is often cheaper than upgrading to a larger primary drive. You get the same storage and better redundancy.

Avoid high-capacity models unless you need them: A 8TB external drive might seem like great value on the spec sheet, but 4TB or two 2TB drives will probably be cheaper in aggregate.

Think about your actual usage: Do you actually need 4TB, or do you think you do? Most users find that 1-2TB is plenty for active working files. Archive old stuff to cloud storage or external archive drives.

Monitor pricing, but don't obsess: SSD prices change weekly, but rarely drop suddenly. Setting price alerts for specific models helps you catch genuine deals without obsessive checking.

FAQ

Why is Kioxia's manufacturing capacity already sold out for 2026?

Kioxia has committed their entire 2026 production capacity to enterprise customers and existing contracts, primarily driven by unprecedented demand from AI data center construction. Large tech companies are buying memory chips in massive quantities to build infrastructure for generative AI models. The demand far exceeds what Kioxia (or any competitor) can produce, even at maximum capacity, because building new semiconductor factories takes 3-5 years and costs $15-25 billion each.

How does the AI boom affect regular consumer SSD prices?

Enterprise customers building AI infrastructure bid aggressively for memory chips and pay premium prices, which gives manufacturers incentive to allocate production toward enterprise orders. Consumer SSDs get squeezed at the allocation level, meaning retailers have fewer drives available, must pay higher wholesale prices, and pass those costs to consumers. High-capacity drives (2TB and above) are hit hardest because data centers specifically need large-capacity storage.

When will SSD prices return to normal levels?

Realistic estimates suggest gradual price improvements starting in late 2027, with meaningful relief (10-20% price drops) arriving in 2028. Return to pre-2024 pricing might not happen until 2029 or later. This assumes AI demand doesn't accelerate further, new capacity comes online on schedule, manufacturing yields improve as expected, and no major geopolitical disruptions occur.

What's the difference between manufacturing capacity and actual production?

Manufacturing capacity is the theoretical maximum a factory could produce under ideal conditions. Actual production is much lower because when production lines first start, yield rates (the percentage of chips that pass quality testing) are often only 20-40%. It takes months or years to optimize processes and improve yields to 70-80% or higher. This ramp period means new capacity doesn't immediately solve shortages.

Should I buy an SSD now or wait for prices to drop?

If you can defer your purchase until late 2027 or 2028, waiting will likely save you 10-20% on most drives and more on high-capacity models. If you need storage now, consider adding a secondary smaller drive rather than upgrading to a single large drive, which often costs less and provides redundancy. Most users find 1-2TB adequate for active files, with older data archived to cloud storage or external archive drives.

Why is Kioxia's Kitakami factory taking so long to reach full production?

Semiconductor manufacturing is extremely complex. New production lines require months of process optimization before they're profitable. Initial yields on new production lines are often 20-40%, requiring continuous tweaking of temperatures, pressures, chemical formulations, and other variables. Improving yields from 50% to 75% takes six months to a year, meaning new capacity ramps slowly rather than coming online suddenly.

Are there any workarounds to avoid paying high SSD prices?

Yes. Most modern PCs have multiple M.2 storage slots, so you can add a secondary drive without replacing your primary drive. Two 1TB drives often cost less than one 2TB drive in shortage conditions and provide redundancy. External USB-C or Thunderbolt enclosures offer another option if your motherboard doesn't have extra slots. You can also manage game libraries across multiple drives in most launchers, keeping frequently-played games on fast storage and archiving older games to secondary storage.

What role do enterprise data centers play in consumer SSD shortages?

Enterprise customers drive the majority of demand and get first priority for limited manufacturing capacity. A single large AI model training run might require terabytes of storage. Data centers deploying AI infrastructure are buying thousands of drives simultaneously. They're willing to pay premium prices because AI infrastructure generates enormous revenue. This demand crowds out consumer purchasing power, forcing retail prices higher and creating longer lead times for consumer products.

How is geographic concentration of memory manufacturing affecting the shortage?

Memory manufacturing is concentrated in Japan (Kioxia), South Korea (Samsung, SK Hynix), the US (Micron, partially), and Taiwan (TSMC). This concentration means there's no alternative supply base if one region has problems. A major earthquake in Japan, military conflict in Taiwan, or tensions between North and South Korea could severely disrupt supply. This geographic risk is why governments are now subsidizing semiconductor manufacturing to create more diversified production.

What's the difference between RAM prices and SSD prices during shortages?

Both come from the same manufacturers and use similar processes, so both are affected by memory shortages. RAM prices have actually risen faster than SSD prices because enterprise data centers need massive amounts of DRAM for AI inference workloads. A single inference server might have 256-512GB of DRAM. Scaling that across thousands of servers means RAM demand is even more insatiable than storage demand.

The Bigger Picture: What This Shortage Means for the Industry

Kioxia's announcement about sold-out capacity through 2026 is really a window into a fundamental shift in how we build computing infrastructure. The era of cheap, abundant memory might be ending, at least temporarily. Or maybe it's ending permanently.

Memory has been getting cheaper and more abundant for decades. That's the fundamental trend—Moore's Law, process improvements, increasing competition. But AI infrastructure is challenging that trend. It's creating demand that outpaces supply even as we build new capacity.

This pressure will eventually drive some important changes. Vertical integration—companies building their own chips—will probably accelerate. Governments will subsidize domestic semiconductor manufacturing. New technologies might emerge that require less memory or operate more efficiently. AI models might hit constraints that reduce memory demand.

But those changes take years. In the meantime, we're in a period where memory is scarce and expensive. It's frustrating for consumers. It's profitable for manufacturers. And it's a clear signal that the old assumptions about technology cost trends might not hold anymore.

The shortage won't last forever. But it's probably going to last longer than most people expect. That's the real message from Kioxia's capacity announcement.

Looking Ahead: What Should You Watch?

Over the next year or two, watch these developments:

Kitakami production ramp: Kioxia's new factory is where the real story unfolds. If it reaches full capacity faster than expected, prices could improve ahead of timeline. If it ramps slower, the shortage extends longer.

Yield improvements: News about manufacturing yield improvements would signal that existing capacity is being used more efficiently. That's a leading indicator of price improvements.

AI demand signals: If major tech companies suddenly reduce their memory purchases, that would indicate AI hype is cooling. Watch for earnings calls and capital expenditure guidance.

Geopolitical developments: Any tensions involving Taiwan, South Korea, or Japan could upend everything. This is an underappreciated risk factor.

New memory technologies: Research into faster, denser, cheaper memory could eventually disrupt current manufacturing constraints. Watch for announcements from research labs.

The memory shortage is real, and it's not going away quickly. But understanding the mechanics—why it happened, who's affected, and when it might improve—helps you make smarter decisions about storage investments and manage your expectations realistically.

In the meantime, add that secondary M.2 drive, archive your old files to cloud storage, and don't expect relief until 2027 or later. That's the realistic path forward.

Key Takeaways

- Kioxia's entire 2026 manufacturing capacity is already sold to enterprise customers, with no relief expected until 2027 at earliest

- AI data center construction is the primary driver, creating unprecedented memory demand that outpaces all manufacturing capacity

- Building new semiconductor fabs requires 3-5 years and costs $15-25 billion, making rapid capacity expansion nearly impossible

- High-capacity SSDs (2TB+) face steeper price premiums because enterprise customers specifically demand these sizes

- Adding secondary M.2 drives or purchasing multiple smaller drives is often more cost-effective than upgrading to single large capacity drives during shortages

Related Articles

- Data Centers to Dominate 70% of Premium Memory Chip Supply in 2026 [2025]

- DDR5 RAM Price Crisis: Why Memory Costs Keep Climbing [2025]

- DDR5 Memory Theft Crisis: Why Thieves Are Smashing Gaming PCs [2025]

- AI Storage Demand Is Breaking NAND Flash Markets [2025]

- DRAM Prices Surge 60% as AI Demand Reshapes Memory Market [2026]

- Trump and Governors Push Tech Giants to Fund Power Plants for AI [2025]

![Kioxia Memory Shortage 2026: Why SSD Prices Stay High [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/kioxia-memory-shortage-2026-why-ssd-prices-stay-high-2025/image-1-1769029927605.jpg)