Introduction: When Fringe Medicine Meets Federal Research Budgets

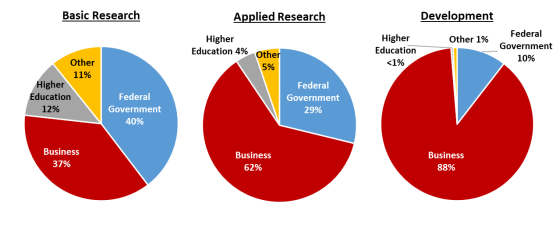

Imagine walking into a major medical institution and learning that precious research funding meant to tackle one of humanity's deadliest diseases is being redirected toward investigating a livestock dewormer. That's not a dystopian thought experiment anymore—it's happening right now within U.S. government health agencies.

The shift represents something far more troubling than a simple misallocation of resources. It signals a fundamental breakdown in the scientific gatekeeping that has protected federal research institutions for decades. When political ideology begins to override evidence-based medicine at the leadership level, the consequences ripple through entire research ecosystems, affecting not just funding priorities but the morale and credibility of the scientific workforce itself.

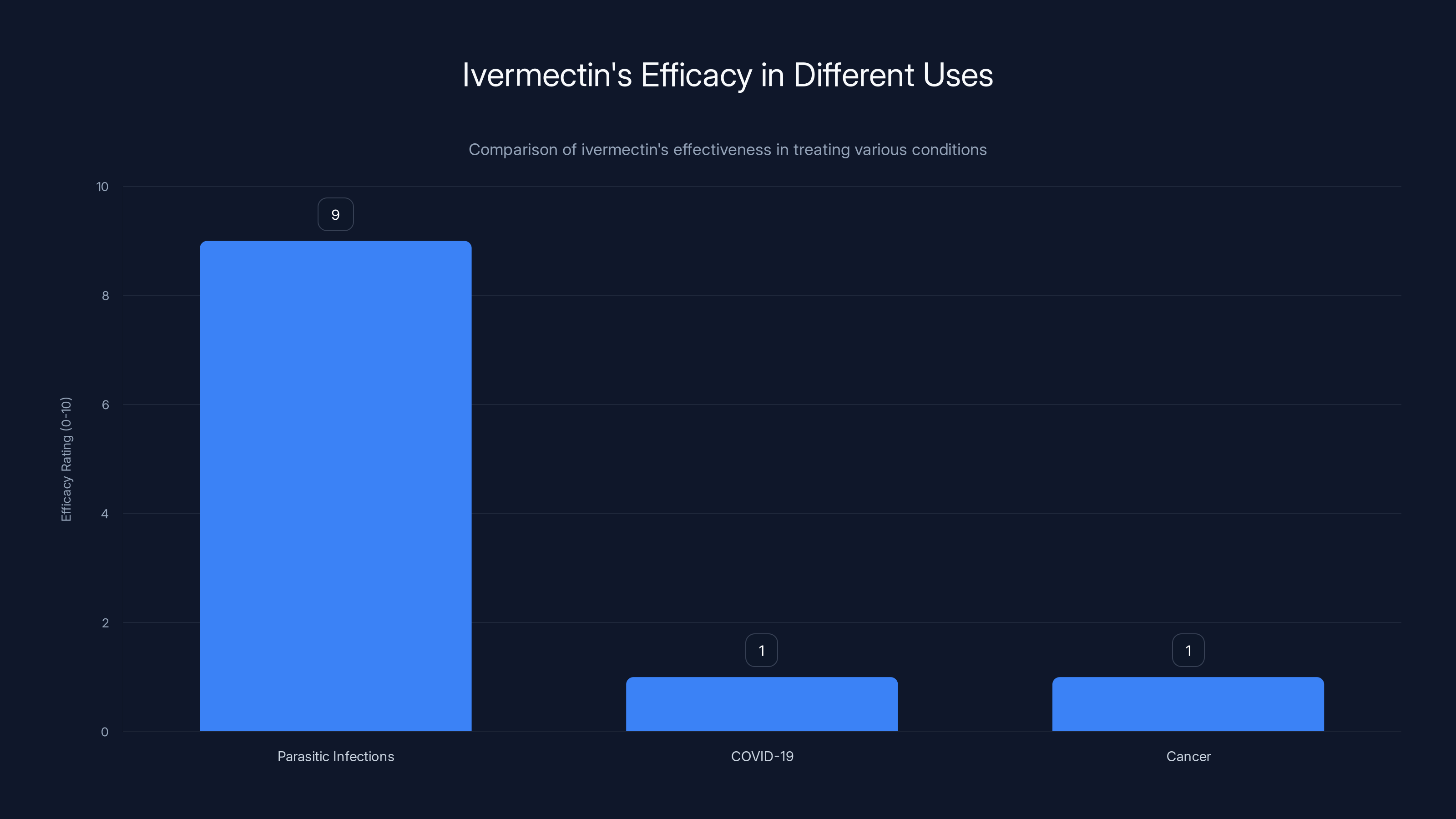

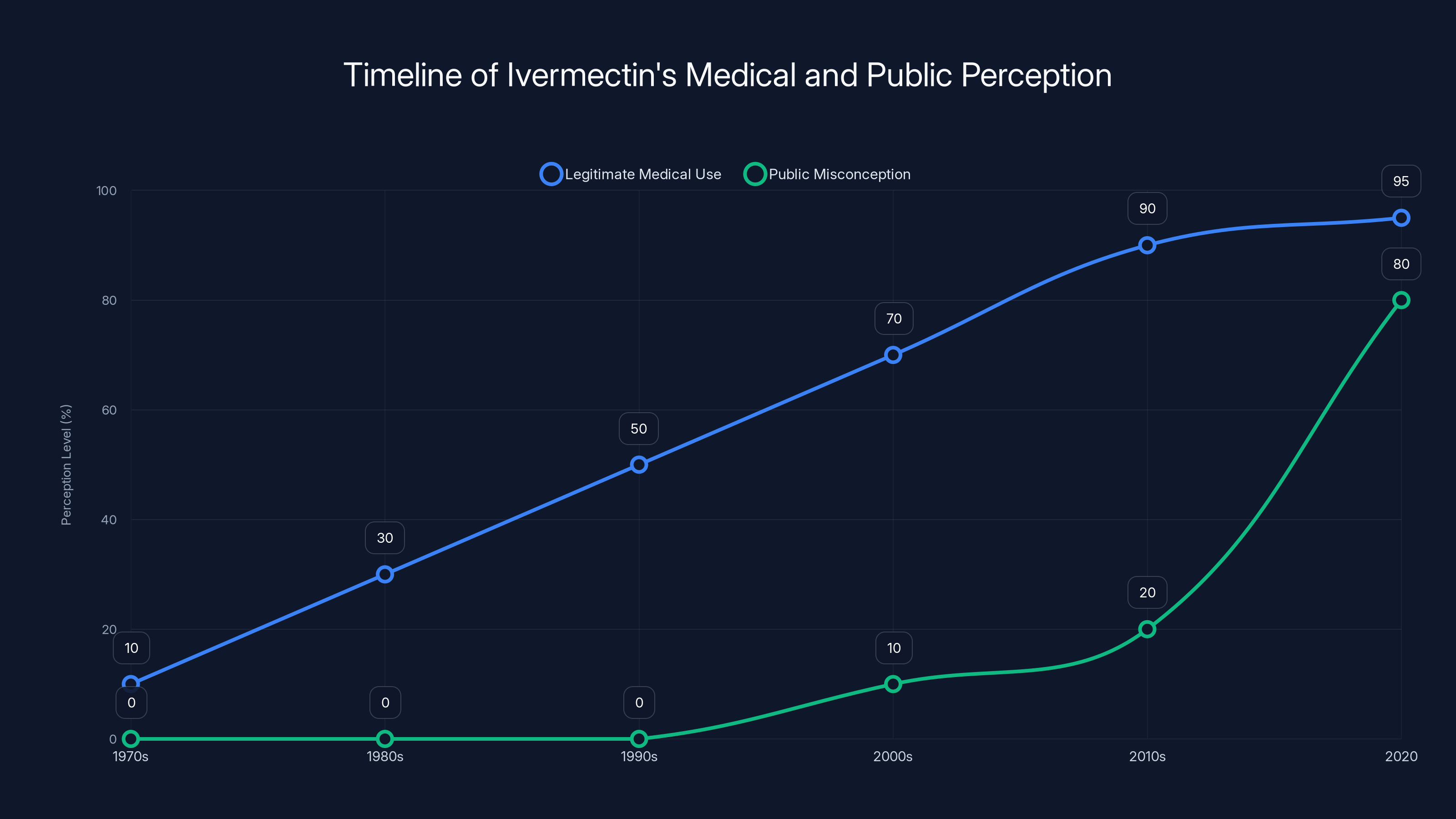

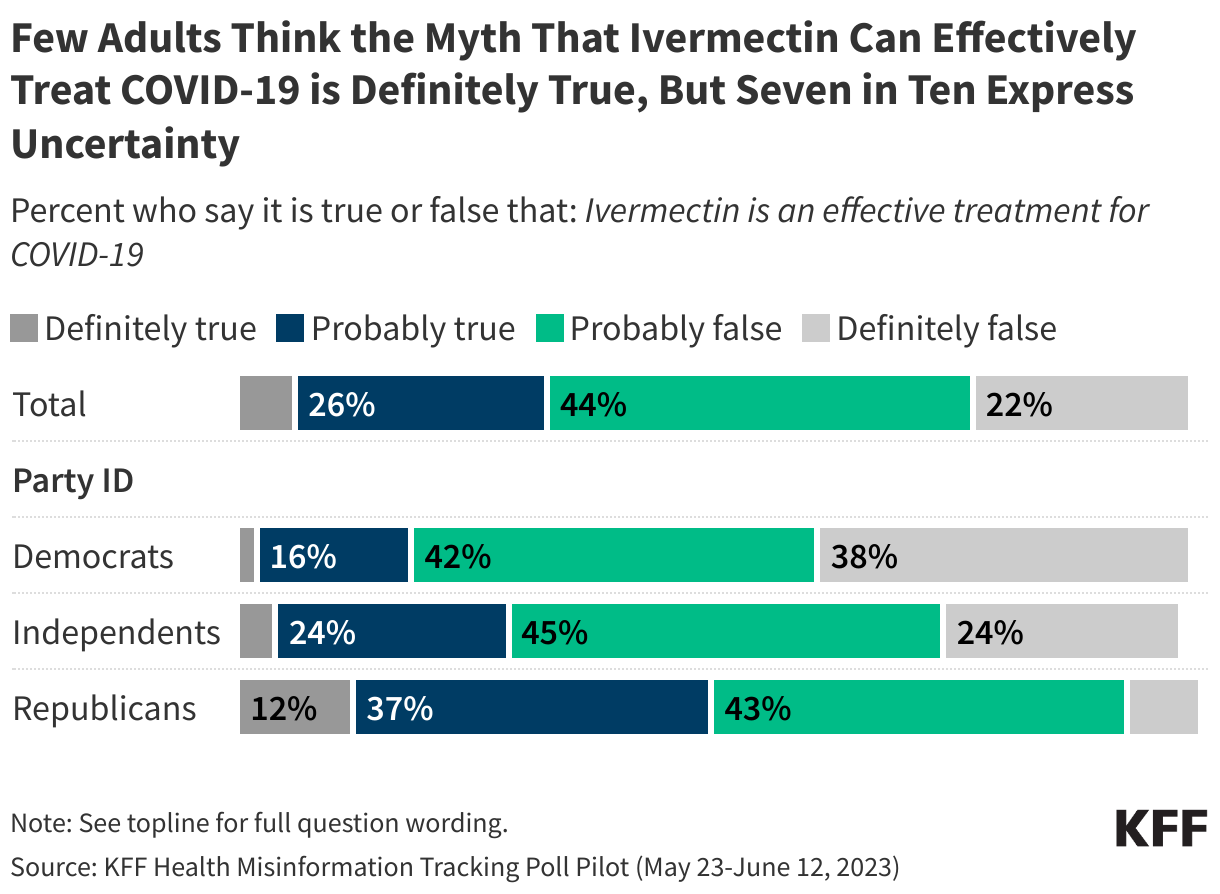

This story begins with a drug called ivermectin. For decades, it was an uncontroversial pharmaceutical tool—genuinely useful for parasitic infections in both humans and animals. Then came 2020. As the COVID-19 pandemic devastated populations worldwide, fringe medical communities seized upon ivermectin as a miracle cure. Despite overwhelming evidence showing it provided no benefit against the virus, the narrative persisted online, gaining traction in specific demographic and political circles.

But the ivermectin saga didn't end when COVID receded. Instead, it evolved. The same networks and individuals who promoted ivermectin for COVID have since repositioned the drug as a universal cure-all, now turning their attention to cancer. And here's where the story takes a darker turn: some of these same individuals now occupy influential positions within federal health institutions.

The question that demands urgent examination is this: How did a drug with no credible evidence for anti-cancer properties come to be studied under the auspices of the National Cancer Institute, the premier federal cancer research agency? The answer involves a convergence of political appointments, institutional capture by fringe medical figures, and a troubling willingness among some government leaders to sacrifice scientific integrity for ideological purposes.

This article explores the full scope of what's happening, why it matters to cancer patients and the broader scientific community, and what the long-term consequences might be if evidence-based medicine continues to erode at the federal level.

TL; DR

- Federal cancer researchers are studying ivermectin despite zero scientific evidence supporting anti-cancer properties, diverting resources from proven treatment pathways

- The initiative reflects broader institutional capture by fringe medical figures now positioned within government health agencies, including anti-vaccine advocates

- Internal National Cancer Institute scientists have privately expressed shock and outrage, calling the research priorities "absurd" and criticizing the redirection of funding

- Ivermectin gained notoriety as a false COVID-19 cure that was extensively studied and roundly debunked, yet the same rhetorical playbook is now being applied to cancer

- The controversy raises fundamental questions about scientific integrity in government institutions when political ideology influences research agendas

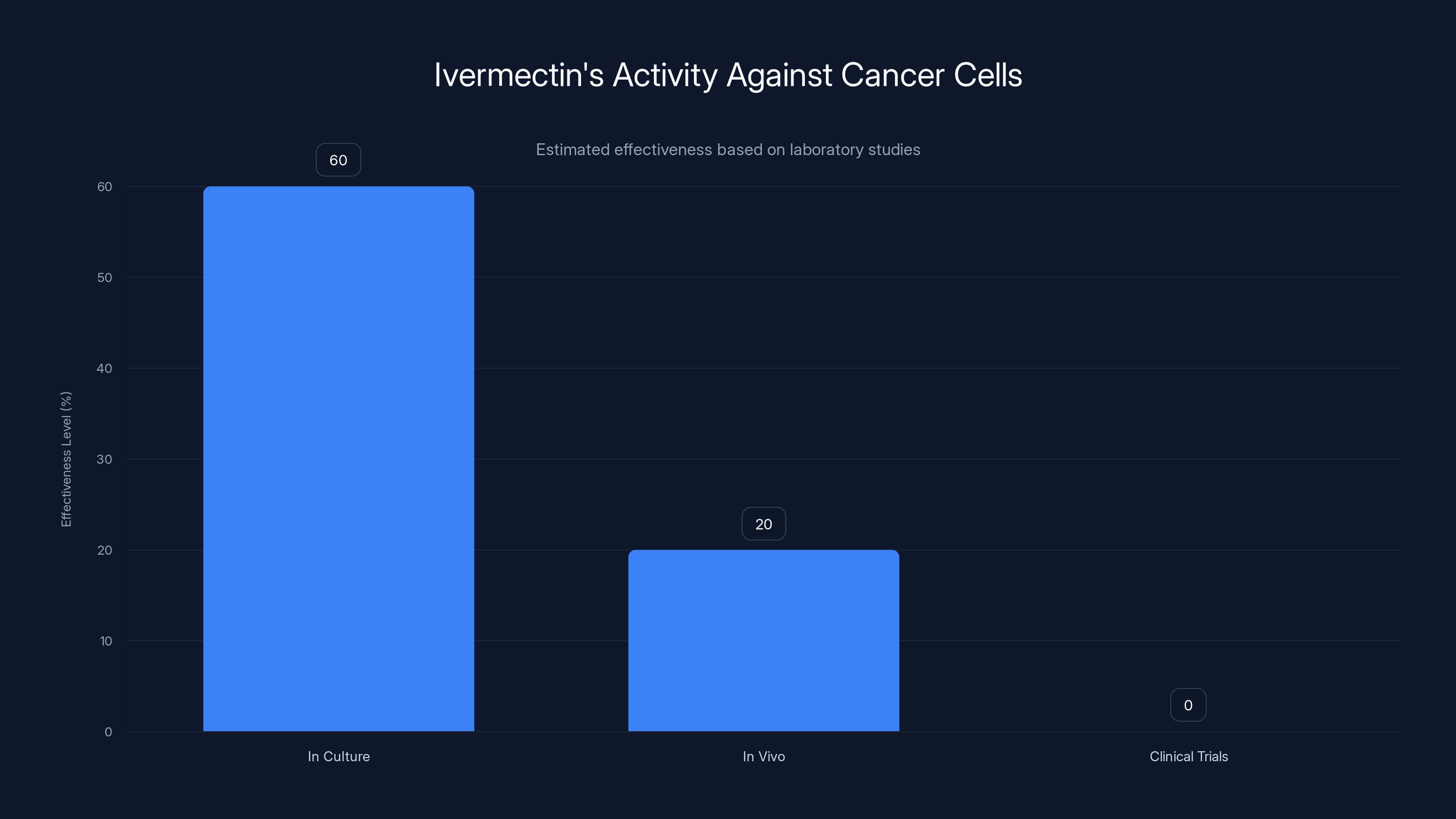

Estimated data shows ivermectin has some activity against cancer cells in culture, but significantly less in vivo and no proven clinical benefit.

Understanding Ivermectin: From Legitimate Medicine to Conspiracy Centerpiece

To understand how we arrived at this moment, we need to examine ivermectin's actual medical history and track exactly where the narrative derailed.

Ivermectin was developed in the 1970s by Japanese researchers who discovered a soil microorganism with remarkable antiparasitic properties. The drug proved genuinely revolutionary for specific applications. River blindness, a parasitic infection affecting millions in developing nations, became dramatically less prevalent following ivermectin distribution campaigns. Lymphatic filariasis, another devastating parasitic disease, has been substantially controlled through ivermectin-based programs. In veterinary medicine, the drug remains a standard deworming agent for livestock and companion animals.

The legitimate medical applications were sufficient to earn the developers a share of the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2015. The achievement wasn't hyperbolic—ivermectin genuinely saved lives and prevented blindness in populations that lacked access to other treatment options. This legitimate track record became crucial later, when advocates could point to genuine medical success as a rhetorical foundation for increasingly dubious claims.

The problem began with a fundamental misunderstanding of how medicine works. The fact that ivermectin targets parasites effectively doesn't mean it should work against viruses or cancer cells. These are completely different biological mechanisms requiring entirely different pharmaceutical approaches. Yet this basic distinction was lost in the online conversations and social media posts that exploded during the pandemic.

By late 2020, unproven claims about ivermectin treating COVID-19 had proliferated across alternative medicine communities. The spread accelerated when some physicians began prescribing it off-label, and when a few preliminary studies seemed to suggest possible benefits. The problem was that subsequent large-scale, high-quality clinical trials consistently found no meaningful effect. Study after study demonstrated that ivermectin didn't reduce hospitalization rates, didn't decrease mortality, and didn't shorten illness duration when compared against placebo.

Yet despite this overwhelming evidence, a specific coalition of alternative health practitioners, anti-vaccine activists, and fringe medical figures continued promoting ivermectin. They developed an increasingly elaborate narrative that pharmaceutical companies and government agencies were suppressing the drug to protect vaccine profits. This conspiratorial framing proved remarkably sticky in certain communities. It provided a simple explanation for complex pandemic challenges and offered people a sense of agency—they could take action against both disease and perceived institutional oppression by using ivermectin.

What makes this historical context crucial is that the rhetorical playbook developed for ivermectin's supposed COVID benefits is now being applied wholesale to cancer. The same figures who insisted the drug worked against COVID despite contradictory evidence now claim anecdotal cases of cancer remission prove ivermectin's efficacy. The same institutional skepticism toward mainstream medicine has transformed into justification for federal funding of unproven therapies.

The scientific method builds credibility through replication, large sample sizes, and mechanism-based understanding. A handful of anecdotal reports—people who took ivermectin and later experienced cancer remission—tells us virtually nothing about whether the drug caused the remission. People recover from cancer through numerous pathways. Some remissions are spontaneous. Others result from conventional treatments the patient may not have prominently mentioned. Attributing recovery to ivermectin simply because temporal coincidence exists is precisely the kind of logical fallacy that medicine abandoned centuries ago.

Ivermectin is highly effective for parasitic infections but shows no meaningful efficacy against COVID-19 or cancer. Estimated data based on clinical findings.

The Rise of Fringe Medical Influence in Federal Health Institutions

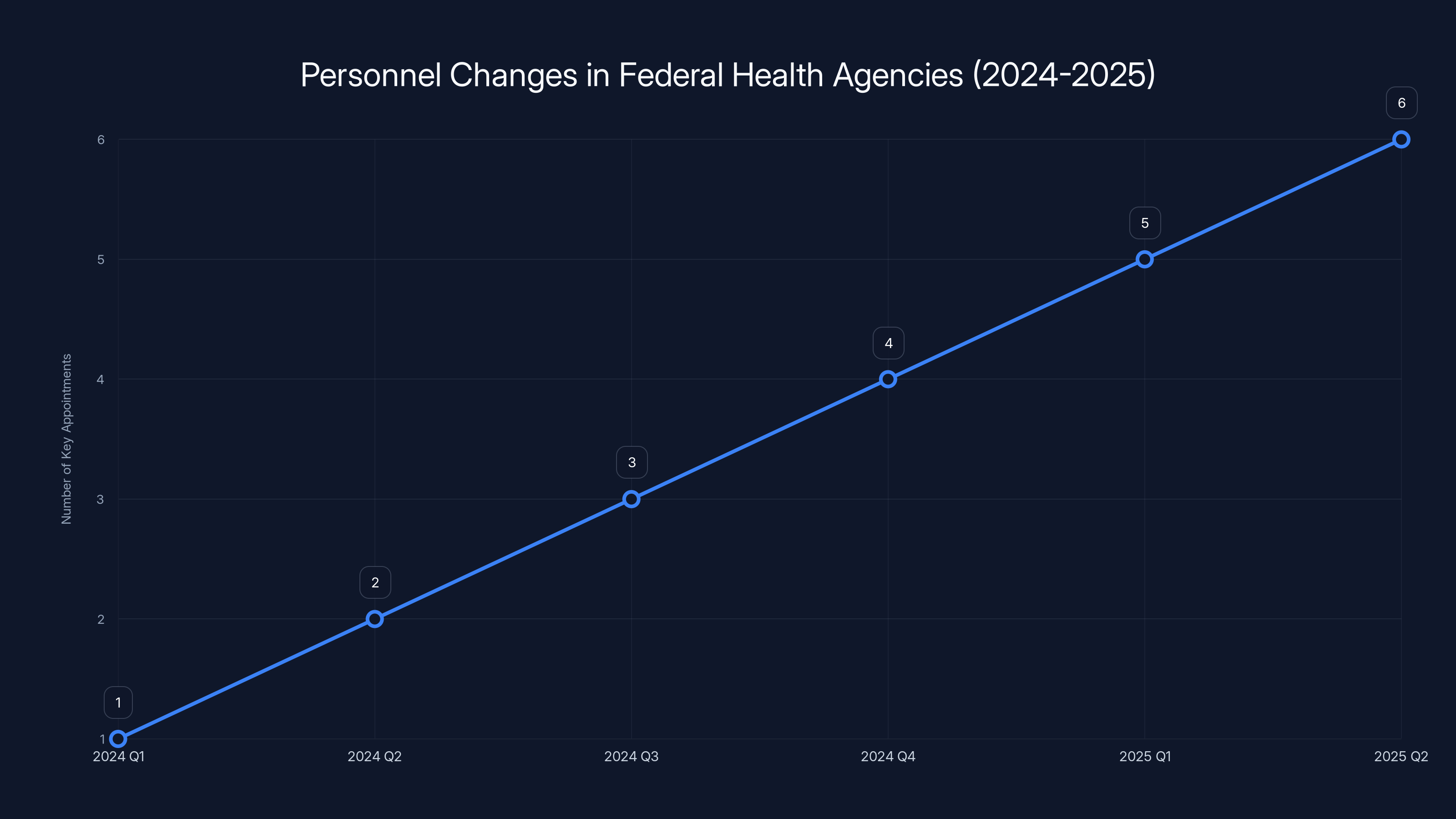

Understanding how ivermectin research became federally funded requires examining the personnel changes that took place in health agencies starting in 2024 and accelerating into 2025.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has long occupied a unique position in American public discourse. Initially known as an environmental attorney and nephew of President John F. Kennedy, Kennedy Jr. eventually became one of the most prominent voices promoting vaccine skepticism. He authored books claiming vaccines cause autism—a claim thoroughly debunked by decades of epidemiological research. He promoted the idea that a parasitic worm lives in his brain, claiming it affected his cognitive abilities. He has advocated for widespread use of unproven medical therapies while dismissing established pharmacological science.

Despite this background, Kennedy Jr. was appointed as Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services under the 2025 Trump administration. This position placed him at the helm of health policy for the entire nation, with authority over agencies including the National Institutes of Health and the National Cancer Institute.

Kennedy Jr.'s appointment wasn't an isolated staffing decision. It reflected a broader transformation in health agency leadership. Anthony Letai, a cancer researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital, was installed as director of the National Cancer Institute. While Letai had a legitimate research background, his appointment signaled a willingness to entertain research directions that wouldn't survive traditional peer review and institutional approval processes.

This personnel shift matters tremendously because agency leadership determines funding priorities, sets research agendas, and establishes institutional culture. When leadership embraces fringe ideas, it creates pressure—explicit or implicit—for agency scientists to pursue those ideas. It signals that questioning prevailing orthodoxy will be rewarded rather than penalized.

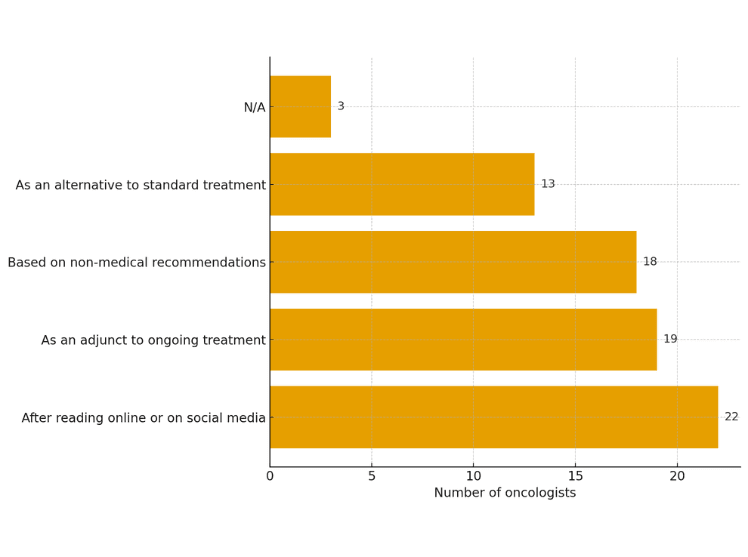

The problem became apparent during a January 2025 event called "Reclaiming Science: The People's NIH," organized by the Make America Healthy Again institute. At this event, Letai publicly discussed the National Cancer Institute's decision to fund research into ivermectin's anti-cancer properties. He framed the research as a response to "reports" and "interest" in the drug—vague terminology that obscured the fact that this interest originated primarily from fringe medical communities rather than from scientific evidence.

Letai attempted to walk a careful line. He acknowledged that ivermectin was "not going to be a cure-all for cancer" and admitted that preclinical studies showed "not a really strong signal" of anti-cancer activity. Yet simultaneously, he validated the anecdotal claims that circulated online about individuals whose cancers supposedly remitted after ivermectin use. This rhetorical approach was strategic—it allowed him to appear dismissive of overstated claims while actually legitimizing the underlying hypothesis through federal investment.

The response from within the National Cancer Institute was swift and damning. Anonymous scientists at the agency expressed shock at the research direction. One scientist told journalists, "I am shocked and appalled. We are moving funds away from so much promising research in order to do a preclinical study based on nonscientific ideas. It's absurd." Another dismissed the suggestion that the NCI had somehow overlooked ivermectin potential, calling the idea "ridiculous."

These internal criticisms reveal the core problem: career scientists understand that research priorities should be determined by scientific evidence, not by celebrity anecdotes or the political sympathies of appointees. The redirection of funding toward ivermectin research meant less money for studies on treatment mechanisms that had already shown promise, for explorations of tumor biology that could lead to genuine breakthroughs, and for clinical trials testing novel therapies in human populations.

The broader institutional capture of federal health agencies raises questions that extend far beyond a single drug or disease. When fringe medical figures gain influence over agencies responsible for protecting public health and directing research funding, what happens to the quality of medical guidance these agencies provide? What happens when health officials publicly promote therapies without scientific support? Do citizens trust medical advice from authorities they perceive as ideologically captured?

Examining the Evidence: What Science Actually Shows About Ivermectin and Cancer

To evaluate the scientific merit of investigating ivermectin as a cancer treatment, we need to examine what the actual evidence shows.

First, consider the basic biological question: what would make ivermectin effective against cancer? Cancer cells are fundamentally different from parasitic organisms. They're human cells that have acquired mutations enabling uncontrolled growth. The mechanisms that parasites use to evade immune systems or cause disease in tissue are not the mechanisms that drive cancer. A drug targeting parasite biology wouldn't logically target cancer biology.

That said, drugs sometimes have unexpected effects. Aspirin was developed as a pain reliever but also affects cardiovascular function. Some cancer drugs were discovered through serendipity rather than rational design. So the existence of cancer biology that's different from parasite biology doesn't absolutely rule out incidental anti-cancer activity.

The question then becomes: what does research actually show? When scientists examine ivermectin's effects on cancer cells in laboratory settings, do they observe meaningful activity?

Some published papers exist reporting that ivermectin shows activity against cancer cells in culture. However, the magnitude of these effects is typically modest, and "activity in culture" is a very different proposition from efficacy in treating actual cancer in living patients. The majority of substances will kill cancer cells if you expose those cells to high enough concentrations in a petri dish. The challenge is killing cancer cells in a living body while preserving healthy tissue—which is why the transition from laboratory findings to clinical benefit requires careful demonstration through clinical trials.

More importantly, no rigorous clinical trials demonstrate that ivermectin benefits cancer patients. When researchers have examined whether ivermectin treatment correlates with improved outcomes, they've found no meaningful benefit. This isn't surprising—the theoretical basis for expecting benefit is weak, and cancer biology has been extensively studied. If a common, inexpensive drug genuinely could treat cancer effectively, we would have identified this through decades of research already conducted.

The anecdotal evidence that drives current advocacy consists of individual reports of cancer remission following ivermectin use. These accounts deserve empathy—cancer survivors have experienced genuine trauma and fear, and they're grateful for recovery regardless of cause. But anecdotal accounts are extraordinarily unreliable guides to medication efficacy. People recover from cancer through numerous mechanisms. Some tumors spontaneously regress. Some apparent remissions reflect incorrect diagnosis or misclassification of disease status. Some involve concurrent conventional treatments the patient downplayed. Attribution to a single drug simply because temporal coincidence exists violates fundamental principles of causal reasoning.

The medical literature contains countless examples of substances that appeared to help individual patients but failed to show benefit in controlled studies. This pattern occurs so reliably that researchers view anecdotal evidence as hypothesis-generating rather than hypothesis-confirming. Anecdotes suggest directions worth investigating, but they require rigorous investigation to determine whether the apparent benefit reflects genuine drug activity or merely reflects coincidence, placebo effect, or other factors.

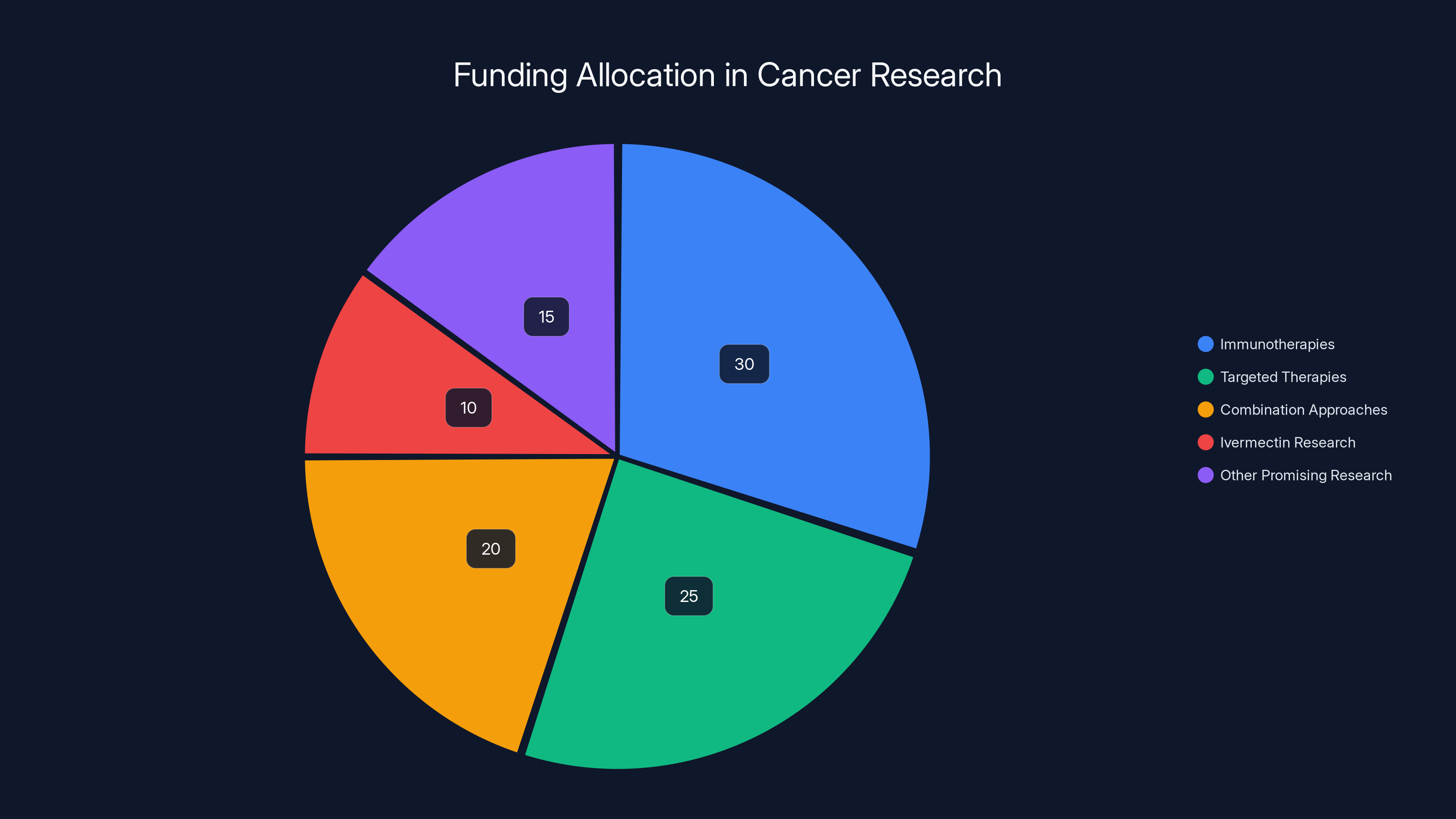

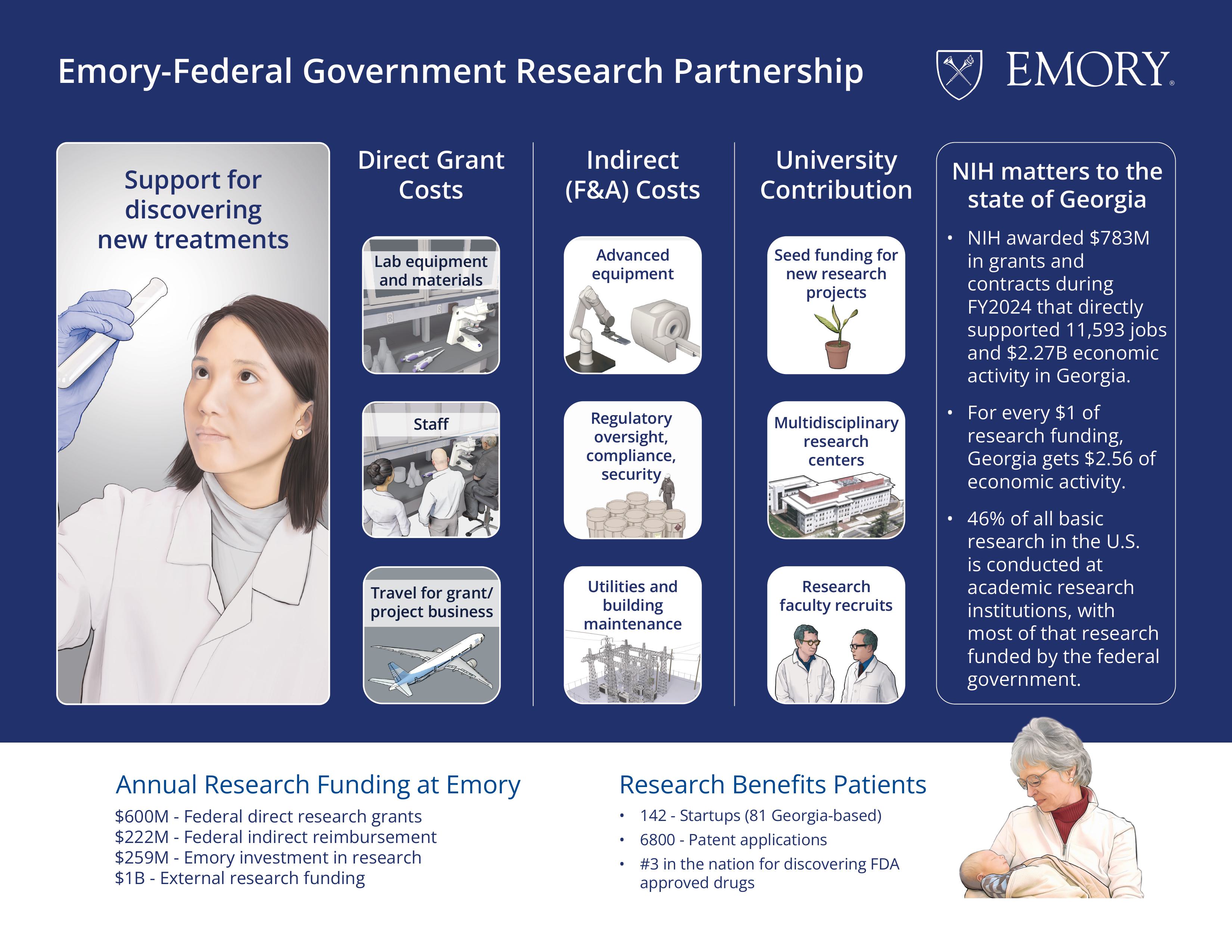

Consider also the opportunity costs. The National Cancer Institute's budget, while substantial, is finite. Research funded for ivermectin studies represents resources diverted from other investigations. What projects were deprioritized to fund ivermectin preclinical work? What studies testing actually promising therapeutic approaches failed to receive funding? These aren't abstract questions—they reflect real trade-offs affecting actual research progress.

Estimated data suggests that a significant portion of cancer research funding is allocated to immunotherapies and targeted therapies, with a smaller percentage directed towards ivermectin research, highlighting opportunity costs in research progress.

The COVID-19 Precedent: How a Disproven Therapy Gained Momentum

Understanding current ivermectin advocacy requires examining how the COVID-19 narrative developed, because the same patterns appear in cancer promotion.

Ivermectin entered COVID discourse because a small number of early studies suggested possible benefits. Some were conducted in developing nations where baseline health care was poor and where confounding variables abounded. Others involved small sample sizes. A few showed methodological problems that became apparent upon closer examination. Yet these initial studies circulated widely in online communities skeptical of established public health guidance.

As more rigorous studies accumulated, the evidence consistently pointed in the opposite direction. Large randomized controlled trials—the gold standard of clinical evidence—found no meaningful benefit. Meta-analyses combining data across multiple studies found no significant effect on hospitalization, mortality, or illness duration. The evidence became overwhelming. By the end of 2021, no credible review of ivermectin's COVID efficacy could conclude anything other than that it didn't work.

Yet despite this evidence, ivermectin advocacy persisted and even accelerated. This persistence revealed something important about how misinformation becomes sticky. Once a narrative takes root in specific communities, contradictory evidence often strengthens rather than weakens belief in that narrative. People interpret new evidence through existing beliefs. Evidence against ivermectin becomes "proof" of suppression by pharmaceutical companies. Studies showing no benefit become "evidence" that regulators are hiding the truth.

This psychological phenomenon—where contradictory evidence actually reinforces false beliefs—is well-established in research on misinformation. It's called the "backfire effect." The mechanism appears to involve cognitive dissonance. When evidence contradicts strongly held beliefs, people experience psychological discomfort. To resolve this discomfort, they sometimes reinterpret evidence rather than revising beliefs. The evidence that should convince them becomes proof of conspiracy.

The ivermectin-for-COVID narrative ultimately proved so resistant to evidence that it became a political and cultural marker. Belief in ivermectin's efficacy signaled skepticism toward establishment institutions, toward large pharmaceutical companies, and toward government health agencies. It became bound up with broader narratives about medical freedom, individual agency, and resistance to perceived authoritarianism.

When these narratives transferred to cancer, they carried this full ideological baggage. Ivermectin's supposed anti-cancer properties weren't primarily justified on scientific grounds—they were justified as another instance of establishment suppression of effective treatments. Cancer, in this narrative, was something the medical establishment actually had the ability to cure but chose not to disclose.

This framing is historically significant. Throughout the twentieth century, similar narratives circulated around various treatments. Some individuals claimed that cancer could be cured through special herbs, through specific diets, through psychological techniques, or through various pharmaceuticals. Many of these claims gained devoted followings. Most proved false when examined rigorously. Yet the narrative structure—that the cure existed but was being suppressed—proved remarkably durable across different contexts.

Institutional Consequences: What Happens When Science Leadership Embraces Fringe Positions

The decision to fund ivermectin research carries consequences that extend far beyond a single study.

First, consider the signal it sends to researchers within the National Cancer Institute and throughout the broader cancer research community. Junior scientists trying to establish careers face explicit career incentives to pursue research that aligns with leadership priorities and funding availability. If leadership indicates that ivermectin research is valued, some scientists will pursue this work—not necessarily because they believe in it, but because career advancement requires securing funding and publishing papers.

This creates a corrosive effect on research culture. Science progresses most effectively when researchers pursue questions they genuinely believe matter and where they see genuine promise. When funding mechanisms incentivize research directions that scientists don't believe in, two things happen. Either researchers pursue the work anyway, producing studies of diminished quality because they lack genuine engagement with the questions. Or researchers, recognizing the mismatch between leadership priorities and good science, become demoralized and seek employment elsewhere.

The National Cancer Institute's anonymous scientists expressed precisely this demoralization. They weren't abstract about the problem—they described it as "absurd." That language reflects genuine frustration that institutional resources are being devoted to pursuing nonscientific ideas. When career scientists view their leadership as scientifically unsound, confidence in institutional direction erodes.

Second, consider the institutional credibility implications. The National Cancer Institute exists because Congress, the public, and the medical community trust this institution to deploy substantial resources in pursuit of genuine scientific progress against cancer. That trust is premised on the assumption that scientific merit drives funding decisions. When leadership funds research lacking scientific support, it undermines the institution's credibility with its own workforce and with the broader scientific community.

This damage is difficult to repair. Trust, once lost, takes years to rebuild. Scientists at other institutions who hear about ivermectin research funding will form impressions about whether the NCI remains guided by evidence or by ideology. Physicians considering whether NCI guidance should influence their clinical practice may become skeptical about institutional recommendations. The public, to the extent it follows these debates, may conclude that government health institutions are captured by ideological forces.

Third, consider the precedent implications. If ivermectin can be funded despite lacking scientific support, what other treatments might receive federal research support under the same logic? Once the gate is open for funding research based on anecdotal reports and fringe advocacy rather than scientific evidence, numerous other unproven treatments could claim similar resources. This represents a fundamental shift in how federal research is allocated—away from evidence-based determination of priorities and toward a more democratic or populist determination where funding reflects cultural interest rather than scientific promise.

Historically, this approach has failed. When medical research organizations devoted resources to treatments popular in specific communities but lacking scientific support, the result was usually resources diverted from more promising work without advancing treatment of the underlying disease. The opportunity costs were substantial, but they were largely invisible—we don't see the discoveries that would have been made if resources had been allocated differently.

Ivermectin's legitimate medical use grew steadily until the 2010s, while public misconceptions surged in 2020, largely due to misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Estimated data.

The Role of Celebrity and Anecdotal Advocacy in Medical Narratives

Celebrities claiming personal health benefits from particular treatments have shaped medical narratives throughout modern history, and the ivermectin-cancer narrative represents a contemporary example of this phenomenon.

When celebrities discuss health treatments, they enjoy several advantages. They command media attention. Their personal accounts are compelling storytelling. They may lack detailed knowledge of the condition they discuss, which paradoxically can make them more persuasive—people relate to personal experiences more than to technical explanations. A celebrity saying "I took ivermectin and my cancer went away" captures attention far more effectively than a detailed discussion of how cancer remission rates vary by tumor type, stage, and prior treatment.

Mel Gibson's claim that ivermectin cured stage 4 cancer in three friends, discussed on a popular podcast and viewed millions of times, exemplifies how celebrity advocacy shapes public perception. The platform alone—a podcast with millions of viewers—ensures that this anecdotal claim reaches far more people than would ever read scientific literature about ivermectin's actual effects. The podcaster may or may not probe the claim's credibility or ask relevant questions about alternative explanations.

From a scientific standpoint, such claims are essentially worthless as evidence. We have no information about the three individuals' actual diagnoses, their prior treatments, their current health status, or any objective measures of remission. We don't know whether they took ivermectin exclusively or combined it with conventional treatments. We don't know the timeframe over which they recovered. The claim might be entirely true, or it might reflect misunderstanding, misremembering, or misrepresentation. Without rigorous documentation and independent verification, we can't determine which.

Yet these claims carry significant persuasive power with audiences. This power doesn't rest on logical evaluation of evidence—it rests on narrative resonance and emotional connection. Stories of individuals triumphing over disease through unconventional means are powerful. They promise agency and hope. They suggest that conventional medicine, which often offers only palliative care or modest survival benefits for advanced cancers, might be missing something.

Pharmaceutical companies understand this power well, which is why pharmaceutical advertising regulations restrict celebrity testimonials. The FDA prohibits "anecdotal" claims about medication benefits in advertising precisely because they're so persuasive despite lacking evidential value. The regulations exist because policymakers recognized that individual stories, while emotionally compelling, are poor guides to medication efficacy.

When government health officials begin validating celebrity anecdotes as research justifications, they undermine their own regulatory frameworks. If anecdotal reports of ivermectin's cancer benefits justify federal research investment, why shouldn't pharmaceutical companies be able to cite similar anecdotes in advertising? If personal testimonials constitute legitimate research guidance at the National Cancer Institute, what distinguishes this from the promotional medicine that the FDA restricts in commercial contexts?

The answer, presumably, is that it doesn't—which represents a significant reversal in how medical evidence is valued at the federal level.

Research Priorities and Opportunity Costs in Cancer Investigation

The decision to fund ivermectin research carries tangible costs in terms of research directions not pursued.

Consider what we actually know about cancer treatment progress. The past thirty years have witnessed remarkable advances in understanding cancer biology at molecular levels. Researchers have identified numerous genetic pathways driving cancer development. They've developed therapies that specifically target these pathways—immunotherapies that enlist the immune system against cancer, targeted therapies that interfere with specific growth signals, combination approaches leveraging multiple mechanisms simultaneously.

These advances didn't happen because researchers randomly tested thousands of compounds hoping something would work. They happened because researchers pursued mechanistic understanding—they asked why cancer cells behaved the way they did, what molecular signals drove their growth, what vulnerabilities could be exploited. This hypothesis-driven research, grounded in biological theory, proved extraordinarily fruitful.

Yet at any moment, far more promising research directions exist than funding allows. Researchers with excellent track records, compelling hypotheses, and preliminary data often fail to secure funding. This isn't because they lack merit—it's because research funding is limited and competition is intense. Roughly 20-30 percent of research proposals that expert reviewers rate as meritorious fail to receive funding simply due to financial constraints.

When the National Cancer Institute decides to fund ivermectin research, this decision necessarily means other research doesn't get funded. These opportunity costs aren't merely financial—they're measured in research progress delayed, in students trained in directions other than where they might most contribute, in breakthroughs that might have emerged from alternative research approaches.

We can't know precisely what research goes unfunded due to ivermectin allocation. But we can recognize that it represents a trade-off: a preclinical study examining a drug lacking biological rationale for anti-cancer activity instead of a clinical trial examining a treatment showing promise in preliminary studies, or instead of fundamental research into cancer biology that could identify new treatment targets.

Over time, these trade-offs accumulate. If research funding increasingly reflects political and ideological preferences rather than scientific merit, the cumulative effect is slower progress in understanding and treating disease. This isn't abstract theorizing—it's a straightforward consequence of resource allocation. When funding mechanisms reward research directions lacking scientific support, overall research productivity decreases.

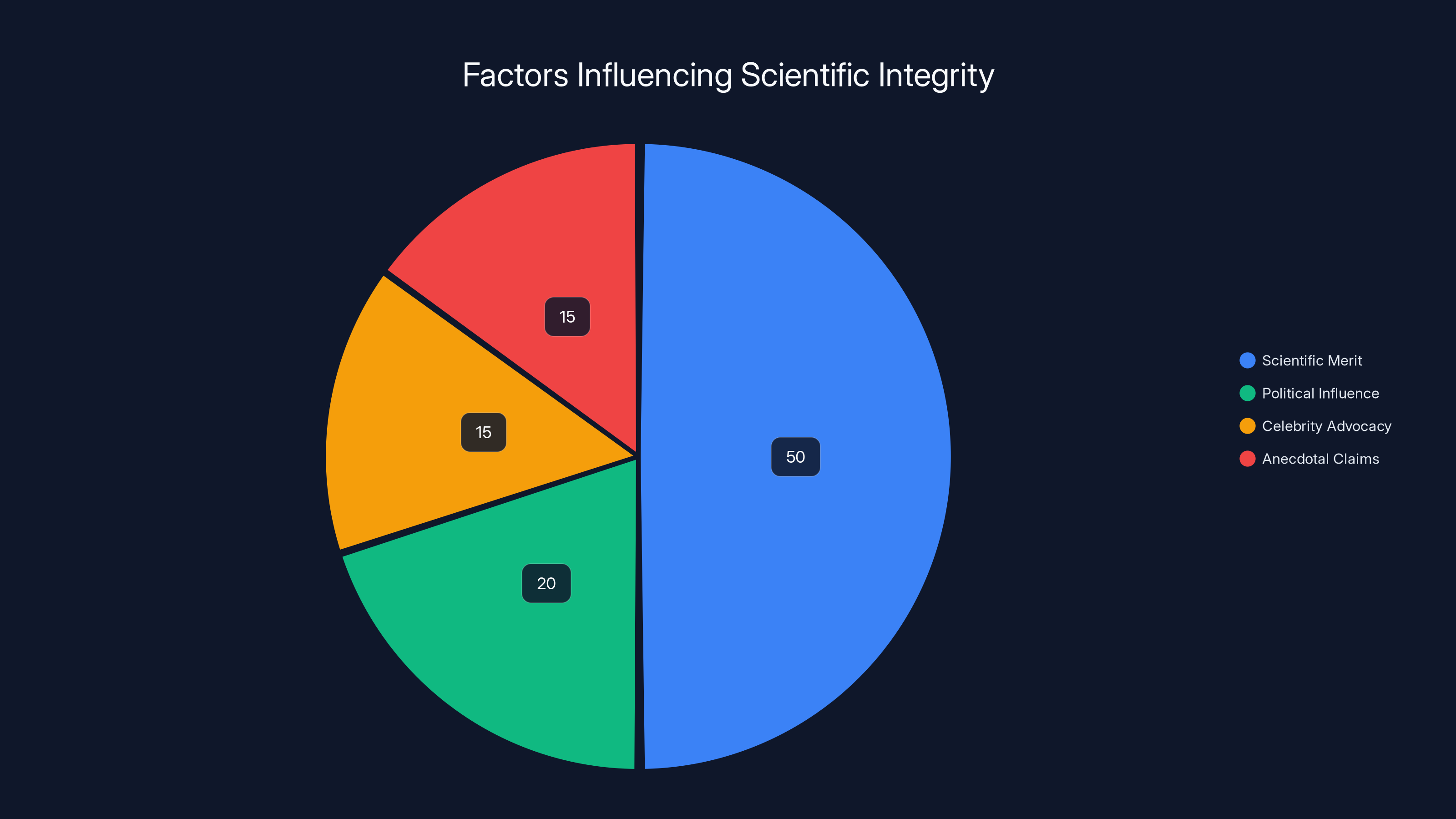

Scientific merit is estimated to be the primary influence on research directions, but political influence, celebrity advocacy, and anecdotal claims also play significant roles. Estimated data.

Mechanism of Action: Why Ivermectin Shouldn't Work Against Cancer

To understand why the ivermectin research initiative is problematic, consider what we know about how this drug actually works.

Ivermectin binds to chloride channels in parasitic organisms, interfering with neural and muscular function. This mechanism is extraordinarily effective for parasites because parasite nervous systems are sufficiently different from mammalian nervous systems that the drug affects parasites more severely than hosts. This selectivity—the ability to target parasites while sparing host tissues—is what makes ivermectin valuable as a medication.

Cancer cells, however, are human cells with human nervous systems. They possess the same chloride channels found in normal human neurons. If ivermectin interfered with these channels at sufficient concentration to kill cancer cells, it would simultaneously interfere with normal neural function throughout the patient's body. This would produce severe neurological toxicity.

Ivermectin does produce neurological side effects at high doses. Patients treated with ivermectin for parasitic infections sometimes experience dizziness, confusion, and motor effects. These effects emerge at doses substantially lower than what would be required to kill cancer cells through this mechanism. Consequently, using ivermectin as a cancer treatment through its primary mechanism of action would likely poison the patient before affecting the cancer.

Could ivermectin have some secondary mechanism affecting cancer cells? Potentially. Many drugs have multiple biological effects. But identifying such mechanisms requires research. The claim that ivermectin kills cancer cells in culture at modest concentrations doesn't automatically indicate that this activity reflects a genuine therapeutic target. Numerous substances kill cancer cells in culture, usually through mechanisms irrelevant to cancer treatment in living patients.

Proponents of ivermectin point to laboratory studies showing anti-cancer activity. However, the concentrations required for this activity in these studies typically far exceed what achieves in patients' tissues after standard dosing. This distinction matters tremendously. A drug might show "activity" against cancer cells at concentrations that clinical use never approaches. This doesn't translate to therapeutic benefit.

Furthermore, if ivermectin genuinely had significant anti-cancer activity through some mechanism, we would expect to see epidemiological signals. In countries where ivermectin is widely used for parasitic infections, cancer incidence and mortality rates should differ from countries with less ivermectin use. No such differences have been documented or suggested. This negative epidemiological evidence further undermines the hypothesis that ivermectin meaningfully affects cancer risk or progression.

Clinical Trial Requirements and Scientific Gatekeeping

Understanding why ivermectin research is problematic requires understanding how clinical trials normally proceed.

Before testing a new treatment in humans, researchers must establish scientific rationale. They conduct laboratory studies examining whether the proposed treatment affects disease biology in ways that might produce clinical benefit. They develop hypotheses about mechanism and effect size. They design clinical trials capable of detecting whether the hypothesized benefit actually materializes.

This gatekeeping process exists for good reasons. Human subjects deserve protection. Exposing patients to treatments without reasonable scientific foundation violates research ethics. The process of moving from laboratory to clinical research is deliberately designed to be selective—not all laboratory findings justify human testing.

When research lacks strong scientific foundation, clinical trials are required to demonstrate benefit before widespread use is justified. Ivermectin for cancer lacks strong scientific foundation. Therefore, clinical trials are required. The preclinical research being funded by the National Cancer Institute should be preliminary to clinical trials, not a substitute for them.

However, fringe medical advocates often frame the requirement for rigorous evidence as "suppression" of alternative treatments. They argue that evidence-based gatekeeping prevents treatments from reaching patients who might benefit. This argument has intuitive appeal, particularly to desperate patients facing terminal illness. It suggests that the medical establishment's caution prevents healing.

In reality, the gatekeeping process exists precisely to protect desperate patients. Without evidence requirements, charlatans could exploit vulnerable individuals, offering expensive ineffective treatments while disease progresses untreated. Patients might spend final months or years pursuing treatments lacking benefit while delaying palliative care that would improve quality of life. The evidence requirements don't prevent treatment—they protect patients from being exploited through false hope.

That said, the evidence requirements should be proportionate to disease severity and available alternatives. For terminal cancer with no effective conventional options, evidence standards might reasonably be lower than for treating mild infections with well-established options. Regulatory frameworks actually incorporate this principle through mechanisms like compassionate use exceptions and expanded access programs, which allow patients to access experimental treatments outside standard trials under specified circumstances.

If ivermectin truly showed signal of anti-cancer activity, a responsible process would involve establishing scientific foundation, designing a clinical trial, and testing the treatment in a limited population of patients with terminal cancer lacking other options. The research could proceed through ethical frameworks designed precisely for this purpose.

Instead, what's happening is that preclinical research is being funded based on political pressure and anecdotal claims rather than genuine scientific signal. This represents a backwards approach—gatekeeping designed to ensure only treatments with promise reach patients is being circumvented by political appointees.

The number of key appointments in federal health agencies increased from 2024 to 2025, reflecting a shift towards fringe medical influence. (Estimated data)

The Psychology of Belief in Unproven Treatments

Understanding the persistence of ivermectin advocacy requires understanding the psychology of how people evaluate medical claims.

When facing serious illness, people understandably seek treatments that might help. Cancer in particular inspires desperate searching for options when conventional medicine offers uncertain outcomes. The desire to find solutions—either for oneself or for loved ones—is entirely human and deserves compassion rather than mockery.

Within this context, unproven treatments become appealing because they offer several psychological benefits. They provide a sense of agency—the feeling that one can take action against disease rather than passively accepting medical verdict. They offer hope that somehow, despite medical consensus, a solution exists. They provide narrative coherence—a explanation for why conventional medicine "isn't working" (it's suppressed) and why alternative treatments might succeed (they're being hidden).

These psychological needs are powerful enough that they can override contradictory evidence. When someone has committed to believing ivermectin works, evidence that it doesn't produce cognitive dissonance. To resolve this discomfort, people can reinterpret evidence. Studies showing no benefit become "proof" that pharmaceutical companies funded the studies to discredit ivermectin. Researchers who criticize ivermectin become "establishment shills." The more evidence accumulates against the treatment, the more elaborate the conspiracy narrative becomes.

This pattern isn't unique to ivermectin. It's been documented across numerous unproven medical treatments. Once people become convinced that a treatment works, they tend to interpret subsequent evidence in ways that preserve this conviction. The psychology underlying this process involves cognitive biases that all humans share—confirmation bias (preferentially noticing evidence supporting existing beliefs), motivated reasoning (interpreting ambiguous evidence in ways favoring preferred conclusions), and susceptibility to conspiracy narratives (attributing contrary evidence to deliberate suppression).

Understanding this psychology doesn't invalidate the experiences of people who improved after taking ivermectin. Many people do improve or experience remission. The question isn't whether improvement occurs—it's whether ivermectin caused the improvement. This causal question is precisely what clinical trials are designed to answer, by comparing outcomes in people who receive ivermectin to outcomes in similar people who don't.

When fringe medical figures gain influence over research funding, they can short-circuit this careful process. Rather than designing trials to answer the causal question rigorously, they can fund research premised on the assumption that ivermectin works, research designed to identify how it works rather than whether it works. This approach produces research showing whatever the researchers hoped to find, because the research design lacks the skepticism necessary to test the hypothesis genuinely.

Erosion of Scientific Standards in Federal Agencies

The ivermectin research initiative represents a concerning trend: the gradual erosion of evidence-based decision-making in federal health agencies.

For much of the twentieth century, the National Institutes of Health and its constituent agencies functioned according to clear principles. Funding decisions were made by expert review panels evaluating research proposals against established scientific criteria. The process wasn't perfect—biases existed, some promising directions were overlooked, some poor research was funded. But the overall system oriented toward scientific merit.

This system relied on several assumptions. First, it assumed that scientific expertise should govern research funding decisions. Second, it assumed that political appointees, while setting broad research priorities, would respect scientific judgment about specific grant awards. Third, it assumed that scientists within agencies would be protected from political pressure to pursue research directions they viewed as scientifically unsound.

The ivermectin research initiative represents a challenge to each of these assumptions. Leadership is directing research toward specific treatments based not on scientific evaluation but on political conviction and anecdotal reports. The research direction is being publicly announced rather than allowing peer review to evaluate scientific merit. Scientists opposing the direction are responding with anonymous criticism rather than open dissent, suggesting they fear retaliation.

This erosion is significant because scientific institutions lose their ability to function when political pressure overrides scientific judgment. Scientists become demoralized. The public loses confidence in institutional recommendations. Other countries' scientists become less willing to collaborate. The entire system that generates reliable medical knowledge becomes compromised.

Historically, attempts to subordinate scientific institutions to political control have produced poor outcomes. During various authoritarian regimes, governments directed research toward politically favored conclusions rather than scientifically supported ones. The result was research institutions that ceased generating reliable knowledge. Once institutions lose credibility and become perceived as politically captured, restoring confidence takes decades.

The United States hasn't undergone authoritarian transformation. Democratic institutions remain in place. But the erosion of scientific standards within specific agencies can occur even within democratic systems, particularly when political movements gain sufficient power to appoint agency leaders who view scientific skepticism as ideology to be overcome.

Precedents: Historical Examples of Nonscientific Research Agendas

The current situation isn't without historical precedent. Understanding past examples illuminates the dangers of allowing nonscientific research agendas.

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union maintained enormous research establishments devoted to studying hypothetical capabilities—telepathy, telekinesis, remote viewing, and other parapsychological phenomena. Despite decades of research and substantial resource investment, no credible evidence for these capabilities emerged. Yet the research continued, driven by the belief that if enemies might develop such capabilities, the Soviets needed to pursue them as well.

The American research establishment maintained some similar programs, though typically less extensive. The CIA funded research into remote viewing and mind control. Universities received grants to study hypothetical psychic phenomena. Most of this research ultimately proved scientifically unproductive.

What's instructive about these historical episodes is that they show how research agendas can become untethered from scientific reality when ideology or geopolitical competition drives funding. Resources devoted to implausible research directions are resources unavailable for research addressing genuine scientific questions. The productivity loss accumulates over years.

More recent examples involve research into treatments that later proved ineffective. For decades, certain alternative medicine practices received substantial research attention despite lacking biological plausibility. Some of this research eventually produced negative results, demonstrating that the treatments didn't work as claimed. The investment in pursuing these avenues represented opportunity cost—the research might have addressed different questions.

The pharmaceutical industry provides another cautionary tale. When companies have invested in developing treatments for hypothetical diseases—conditions without clear epidemiological basis or scientific foundation—the result has typically been failed products and wasted resources. In contrast, companies that invested in mechanisms with clear biological foundation and preliminary evidence of efficacy were more likely to develop successful drugs.

These precedents suggest that research tends to be most productive when directed toward questions with genuine scientific merit. Once research becomes divorced from scientific evaluation of merit, productivity declines.

Restoring Scientific Integrity to Federal Research Institutions

If the ivermectin research initiative represents problematic erosion of scientific standards, restoring integrity requires specific steps.

First, research funding decisions need to return to expert review processes. This doesn't mean scientific decisions are apolitical—all large institutions reflect broader values and priorities. But the process of determining whether specific research proposals merit funding should involve scientific experts evaluating scientific merit, not political appointees making determinations based on ideology or anecdote.

Second, agency scientists need protection from retaliation for disagreeing with leadership. The current situation, where National Cancer Institute scientists feel compelled to criticize leadership anonymously rather than openly, suggests that retaliation is feared. Strong conflict-of-interest policies, whistleblower protections, and tenure systems should insulate scientists from political pressure.

Third, agency leadership should be selected based on demonstrated commitment to evidence-based decision-making. This doesn't require leaders to lack opinions about priorities—it requires that they respect scientific expertise when it contradicts their preferred conclusions. A director who insists funding pursue treatments lacking scientific support has abandoned the core principle that should guide scientific institutions.

Fourth, the public needs accurate information about research directions. When federal agencies pursue research lacking scientific foundation, this should be publicly acknowledged rather than obfuscated. The National Cancer Institute could truthfully say, "We're studying ivermectin because of substantial public interest despite lacking preliminary data suggesting efficacy." This transparency would allow informed public debate about whether this represents appropriate research allocation.

Fifth, the agency should establish clear criteria for when anecdotal reports justify research investment. This isn't to say anecdotal evidence should be completely dismissed—it can suggest research directions. But criteria should exist: How many anecdotal reports justify a study? What documentation level is required? How is causation inferred from temporal coincidence?

These steps wouldn't be without controversy. Some would characterize them as protecting "establishment science" against questioning. But protecting scientific institutions against political capture is precisely the goal. The alternative is research institutions that produce whatever results political appointees desire rather than knowledge reflecting reality.

The Future: What Happens If Fringe Medical Ideas Continue Capturing Federal Institutions

The ivermectin research initiative is unlikely to be isolated. If it succeeds in establishing that anecdotal reports and celebrity testimonials can justify federal research investment, numerous similar initiatives might follow.

Consider the portfolio of unproven treatments already circulating in alternative medicine communities: special herbs supposedly curing various cancers, dietary protocols claimed to reverse disease, supplements promoted as preventing disease, and practices ranging from acupuncture to homeopathy. Each has advocates. Each has anecdotal reports of benefit. Each could potentially claim federal research support based on the precedent established by ivermectin.

If research funding increasingly reflects anecdotal interest rather than scientific promise, the consequence is a research portfolio misaligned with where genuine breakthroughs might occur. Resources spread across numerous implausible directions rather than concentrated on most promising approaches. The pace of scientific progress slows. Patient outcomes deteriorate as research diverts from proven treatment development toward investigation of unlikely alternatives.

The problem compounds over time. As federal institutions become viewed as politically captured, private research funding from foundations, universities, and pharmaceutical companies becomes more important. But this creates a two-tiered system where government institutions pursue politically motivated research while private actors pursue scientifically rational research. Public confidence in government institutions declines further. Scientific training becomes less attractive when federal agencies are perceived as hostile to evidence-based practice.

International collaboration suffers. When foreign scientists perceive that American research institutions are scientifically compromised, they're less likely to collaborate with American researchers or share information and resources. The United States has historically benefited from being perceived as a leader in scientific rigor. Once this reputation erodes, the benefit declines.

None of this is inevitable. The dynamics I'm describing aren't laws of nature—they reflect consequences of specific choices about how research institutions function. Different choices could produce different outcomes. But if the trajectory continues, the long-term consequences for American scientific capacity will be significant.

What Cancer Patients Should Actually Know About Treatment

Given all this discussion of problematic research directions, it's worth emphasizing what actual evidence says about cancer treatment.

Cancer remains serious disease with significant mortality. Modern treatments have improved outcomes dramatically compared to decades past, but they're not panaceas. Some cancers are readily treatable—early stage breast cancer, for example, has excellent prognosis with current approaches. Others remain difficult despite intensive research.

Conventional treatments—surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy—have been tested extensively in clinical trials. Their benefits and risks are well-documented. They work through mechanisms grounded in cancer biology. They're effective enough to be considered standard of care.

That said, these treatments have limitations. They produce side effects. They don't work for all patients. Some cancers develop resistance to treatments initially effective. Researchers continue seeking better approaches.

This is precisely why clinical research is important. Researchers pursue new treatment approaches through rigorous testing, documenting what works and what doesn't. This process is slow and sometimes frustrating. It requires documenting negative results alongside positive ones. It requires disciplined skepticism about our own hypotheses.

Unproven treatments might work. But we can't know which ones, or how effectively, without testing. The testing process—clinical trials—is the means by which medicine distinguishes treatments that genuinely help from those that seem helpful but don't actually improve outcomes.

Patients with cancer deserve access to the best available evidence-based treatments. They also deserve the opportunity to participate in clinical trials testing promising new approaches. What they don't deserve is to have limited research resources diverted toward investigating treatments lacking scientific foundation.

FAQ

What is ivermectin and what is it actually used for?

Ivermectin is an antiparasitic medication developed in the 1970s, genuinely effective for treating parasitic infections like river blindness and roundworm infestations in both humans and animals. It works by interfering with parasite nervous system function and has legitimately saved millions of lives. However, this appropriate medical use for parasites is entirely separate from the unsubstantiated claims that it treats viral infections or cancer.

How did ivermectin become promoted as a COVID-19 treatment?

During the COVID-19 pandemic, some early small studies suggested possible benefit, and this led to widespread promotion in alternative medicine and online communities. However, large rigorous clinical trials consistently found no meaningful effect against COVID-19. Despite overwhelming evidence against efficacy, advocacy for ivermectin persisted in certain communities, often framed as resistance to institutional suppression rather than as response to new scientific evidence.

Why would ivermectin theoretically work against cancer?

There's no clear biological reason ivermectin should work against cancer. The drug targets parasite nervous systems through mechanisms specific to parasites. Cancer cells are human cells that have acquired growth mutations, requiring different treatment approaches. While laboratory studies sometimes show ivermectin activity against cancer cells in culture, this activity occurs at concentrations far exceeding what clinical use achieves and doesn't establish therapeutic benefit.

What do clinical trials show about ivermectin for cancer?

No rigorous clinical trials demonstrate that ivermectin benefits cancer patients. The National Cancer Institute is conducting preclinical research examining the drug's properties, but this research lacks strong scientific foundation. Historical pattern shows that treatments lacking both biological plausibility and preliminary clinical evidence rarely prove effective when tested in actual patients.

Why would federal research funding for ivermectin research be problematic even if the drug might work?

Research resources are finite and competition for funding is intense. Allocating resources to research lacking scientific merit necessarily diverts resources from research with genuine promise. Additionally, funding research based on anecdotal claims rather than scientific evaluation undermines evidence-based decision-making principles that have guided federal research institutions. This sets concerning precedent for research directed by political appointees rather than scientific experts.

How can patients with cancer distinguish between legitimate treatments and unproven ones?

Legitiimate cancer treatments have been tested in clinical trials, published in peer-reviewed medical literature, and incorporated into clinical practice guidelines developed by medical societies. The National Cancer Institute website provides reliable information about evidence-based cancer treatments. Patients should be skeptical of treatments promoted primarily through anecdotal reports, celebrity testimonials, or alternative medicine communities rather than scientific evidence.

What should happen if a patient is interested in trying an unproven treatment?

Patients should discuss any proposed treatment with their oncologist before pursuing it. Some unproven treatments might be worth investigating through clinical trials if the patient has exhausted conventional options. Compassionate use pathways exist precisely for this purpose, allowing access to experimental treatments outside standard trials under appropriate medical oversight. However, pursuing unproven alternatives while abandoning conventional treatment is generally counterproductive.

Why do people continue believing in treatments despite evidence showing they don't work?

This reflects well-established psychological patterns. Once people become convinced treatments work, contradictory evidence often strengthens rather than weakens belief, through processes like confirmation bias and motivated reasoning. Additionally, beliefs about treatments often become bound up with broader narratives about institutional trust, medical freedom, and resistance to authority, making them resistant to evidence-based revision.

What does this ivermectin situation say about the reliability of federal health agencies?

The situation raises concerns about potential erosion of evidence-based decision-making at the federal level if political appointees begin directing research toward treatments lacking scientific merit. However, the existence of internal scientific criticism and skepticism suggests that resistance to this erosion exists within agencies. The long-term trajectory depends on whether mechanisms protecting scientific integrity continue functioning.

How can the public stay informed about research quality and agency direction?

Following scientific and health news from reputable outlets that fact-check claims and explain evidence basis is helpful. Understanding basic principles of how evidence is evaluated—distinguishing between anecdotal reports and clinical trials, between laboratory findings and clinical efficacy—provides tools for evaluating medical claims. Being skeptical of treatments promoted primarily through celebrity endorsement or conspiracy narratives while remaining open to evidence-based innovations represents an appropriate middle position.

Conclusion: Why Scientific Integrity Matters in the Era of Medical Misinformation

The decision to fund ivermectin cancer research through the National Cancer Institute represents more than a questionable allocation of a specific research budget. It exemplifies a broader challenge facing science institutions in an era when misinformation circulates rapidly, when celebrity advocates amplify unproven claims, and when political appointees increasingly shape institutional directions.

At its core, the controversy is about institutional identity and purpose. The National Cancer Institute exists because the American public, through its elected representatives, chose to invest substantially in understanding and treating cancer. This investment reflects a social contract—the public provides resources, and the institute uses those resources to advance knowledge and improve outcomes. That contract is premised on an assumption that the institute will pursue research directions based on scientific merit.

When that contract is violated—when research is directed based on political ideology, anecdotal claims, or celebrity advocacy rather than scientific evidence—the institution loses its reason for existing in its current form. It becomes indistinguishable from entertainment, marketing, or advocacy organizations. Its ability to generate reliable knowledge declines. Its credibility with other scientists, with medical professionals, and with the public deteriorates.

The scientists within the National Cancer Institute who expressed shock and appeasement about the ivermectin research decision weren't exhibiting defensive orthodoxy protecting bad old ideas. They were attempting to preserve an institution's core function—the systematic pursuit of reliable knowledge about cancer biology and treatment. They were expressing concern that an institution designed to advance science was instead being directed toward politically motivated research.

This concern is legitimate. The long-term health of science depends on maintaining standards of evidence, on protecting research decisions from political capture, on allowing expertise rather than ideology to determine research priorities. Once these standards erode, they're difficult to restore. Other countries' scientists notice and respond. Training becomes less attractive. Collaboration declines. The institutions that once led globally in scientific advancement become known for political alignment rather than discovery.

None of this is inevitable. The situation can still be corrected. Leadership can acknowledge that the ivermectin research direction lacks scientific foundation and reorient toward research with genuine promise. Congress can reinforce protections for scientific integrity in federal agencies. The public can demand that government health institutions remain devoted to evidence-based practice. Scientists can continue speaking up for evidence-based decision-making, even when doing so requires challenging powerful appointees.

But these corrective steps won't happen automatically. They require commitment to the principle that scientific institutions should be governed by scientific evidence rather than by political ideology. They require willingness to acknowledge that some widely believed claims lack evidence supporting them. They require patience with the slow process of rigorous testing rather than expecting quick answers.

For cancer patients facing difficult diagnoses, the stakes of maintaining scientific integrity in cancer research are quite literal. When research resources are misallocated toward investigating unlikely treatments, fewer resources are available for investigating approaches with genuine promise. When research institutions lose credibility due to political capture, patients lose reliable guidance about what treatments might actually help. The erosion of scientific standards in research institutions isn't abstract—it affects real people making consequential decisions about their health.

The ivermectin research initiative will ultimately produce results. Months from now, scientists funded through the National Cancer Institute will publish findings about ivermectin's activity against cancer cells in laboratory conditions. Depending on what those conditions showed, the results might be positive, negative, or equivocal. But the value of the research is questionable regardless of outcome, because the research was never designed to answer the real question patients care about: does ivermectin actually help people with cancer?

Answering that question requires clinical trials, careful documentation of outcomes, comparison to standard treatment, and rigorous evaluation of whether observed improvements reflect the treatment or represent coincidence. Until such trials occur and produce evidence of benefit, ivermectin remains an unproven treatment. The federal government supporting research based on anecdotal claims rather than insisting on evidence before allocation of resources represents a troubling shift in how American research institutions function.

The broader implications are concerning. If ivermectin can be funded despite lacking scientific justification, numerous other unproven treatments could claim similar resources. If research directions can be determined by political appointees and online advocacy rather than by scientific experts evaluating merit, research institutions lose their distinctive value. If federal agencies that the public trusts to provide reliable medical guidance instead advocate for treatments lacking evidence, people lose reliable sources of information about health.

Maintaining scientific integrity in research institutions requires constant effort. It requires resisting pressure to pursue politically popular directions. It requires saying no to treatments that seem intuitively appealing but lack evidence. It requires patience with slow processes of rigorous testing. It requires humility about what we don't know, even when admitting uncertainty feels like admitting defeat.

But the alternative is institutions that produce propaganda rather than knowledge, that serve ideological rather than scientific purposes, that ultimately harm the patients and public they're meant to serve. The ivermectin research initiative represents a test of whether federal research institutions can maintain these standards in an era of political pressure. The outcome will shape not just cancer research, but the future of American scientific institution itself.

Key Takeaways

- Federal cancer research is being directed toward investigating ivermectin despite lacking scientific evidence for anti-cancer properties, representing institutional capture by fringe medical advocates

- Internal National Cancer Institute scientists have privately expressed shock at the research direction, calling it absurd and criticizing the redirection of funds from proven research pathways

- Ivermectin gained notoriety through false COVID-19 claims that were extensively tested and soundly debunked, yet the same rhetorical framework is being applied to cancer advocacy

- The situation reveals how political appointees at federal health agencies can override scientific merit-based decision-making when lacking strong institutional protections for scientific integrity

- Allowing anecdotal claims and celebrity testimonials to justify federal research funding sets dangerous precedent that could redirect resources away from evidence-based investigations across multiple disease areas

Related Articles

- NIH's Second Scientific Revolution: COVID Anger, MAHA Politics, and Real Reform [2025]

- DOE Climate Working Group Ruled Illegal: What the Judge's Decision Means [2025]

- Why Microdosing LSD Fails for Depression: The Placebo Study [2025]

- Best VPNs for Super Bowl LIX: Complete Streaming Guide 2025

- Medical Research Crisis: Trump Administration's Impact on NIH [2025]

- HHS AI Tool for Vaccine Injury Claims: What Experts Warn [2025]

![Ivermectin as Cancer Treatment: Why Federal Research Funding Raises Red Flags [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ivermectin-as-cancer-treatment-why-federal-research-funding-/image-1-1770750736134.jpg)