Jeffrey Epstein's 'Personal Hacker': The Zero-Day Exploits, Cyber Weapons, and International Espionage Network [2025]

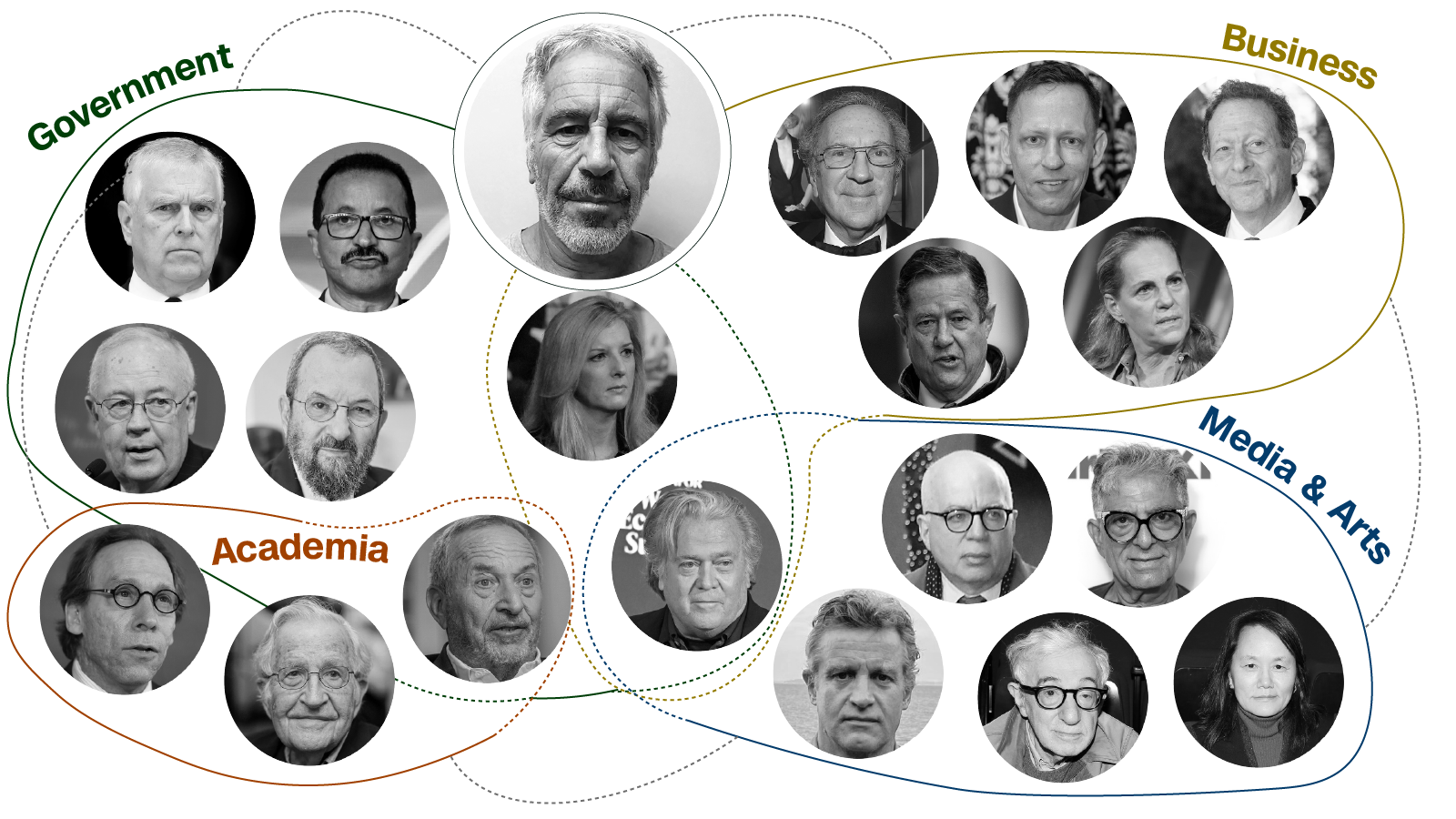

In January 2025, the Department of Justice released a bombshell document that fundamentally shifted how we understand Jeffrey Epstein's criminal enterprise. It wasn't just about financial manipulation or trafficking networks. Buried in thousands of pages of newly released files was a confidential informant's account of something far more sinister: Epstein allegedly employed a personal hacker who developed and sold zero-day exploits to foreign governments, militant organizations, and rogue actors across the globe, as reported by TechCrunch.

This revelation opens a door into a world most people don't realize exists, let alone understand. The cyber weapons market operates in shadows. It's worth billions of dollars annually, involves major governments, private military contractors, and sophisticated criminal organizations. And according to this FBI informant, Epstein—a financier known primarily for sex trafficking crimes—was deeply connected to this underworld.

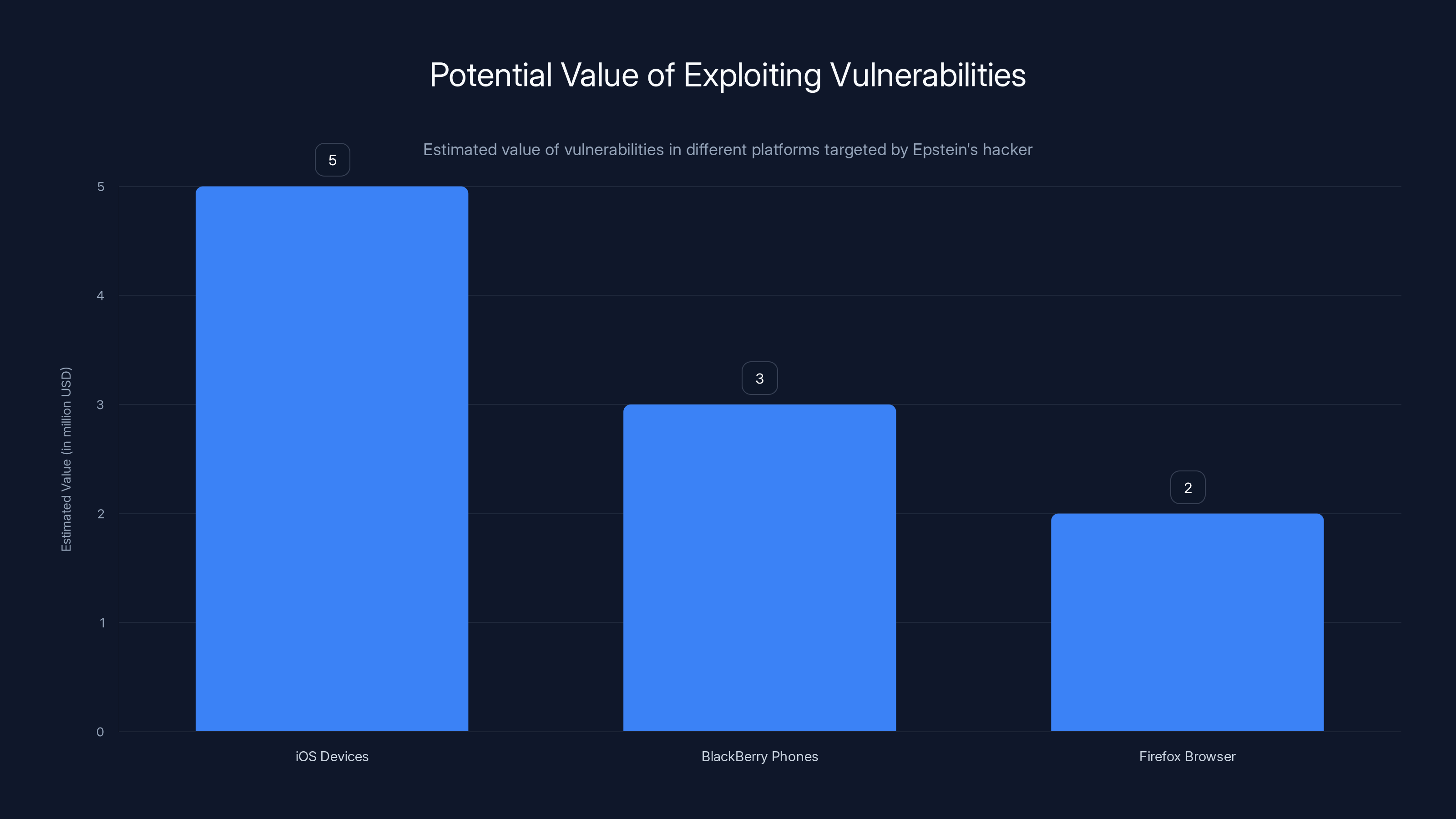

The hacker in question was allegedly born in Calabria, Italy, and possessed elite-level skills in finding critical vulnerabilities in iOS devices, BlackBerry phones, and Firefox browsers. These weren't bugs that would cause minor inconveniences. These were zero-day exploits, meaning they were unknown to the software companies that created the systems. Once sold or deployed, they could be weaponized to spy on anyone, anywhere, without their knowledge.

We're talking about the kind of tools that intelligence agencies dream about. The kind that can compromise an entire nation's communication infrastructure. The kind that, in the wrong hands, can topple governments or decimate critical infrastructure.

But here's the thing: the full scope of this network remains unclear. The document provides tantalizing details but massive gaps. Who was this hacker exactly? Is he still alive? What exploits did he actually develop? How many countries bought his tools? How much money changed hands? And most importantly, what happened to those zero-days after they were sold?

This isn't just a fascinating criminal story. It's a window into how the global cyber weapons market actually functions. It reveals the intersection between organized crime, government intelligence operations, and the multibillion-dollar trade in exploitable software vulnerabilities. And it raises uncomfortable questions about oversight, regulation, and who gets access to weapons that can surveil entire populations.

Let's break down what we know, what we don't, and what this tells us about the state of cybersecurity, government surveillance, and the murky world of zero-day trafficking.

TL; DR

- FBI documents reveal Epstein employed an Italian hacker specializing in iOS, BlackBerry, and Firefox vulnerabilities

- Zero-day market confirmed: The hacker allegedly sold exploits to central African governments, the U.K., the U.S., and Hezbollah

- Payment in cash: One transaction involved Hezbollah paying with "a trunk of cash" for a zero-day exploit

- Scale unknown: The full extent of the network, number of exploits sold, and current status remain undisclosed

- Cybersecurity implications: This case highlights the real-world consequences of the billion-dollar cyber weapons market and the vulnerability of critical systems

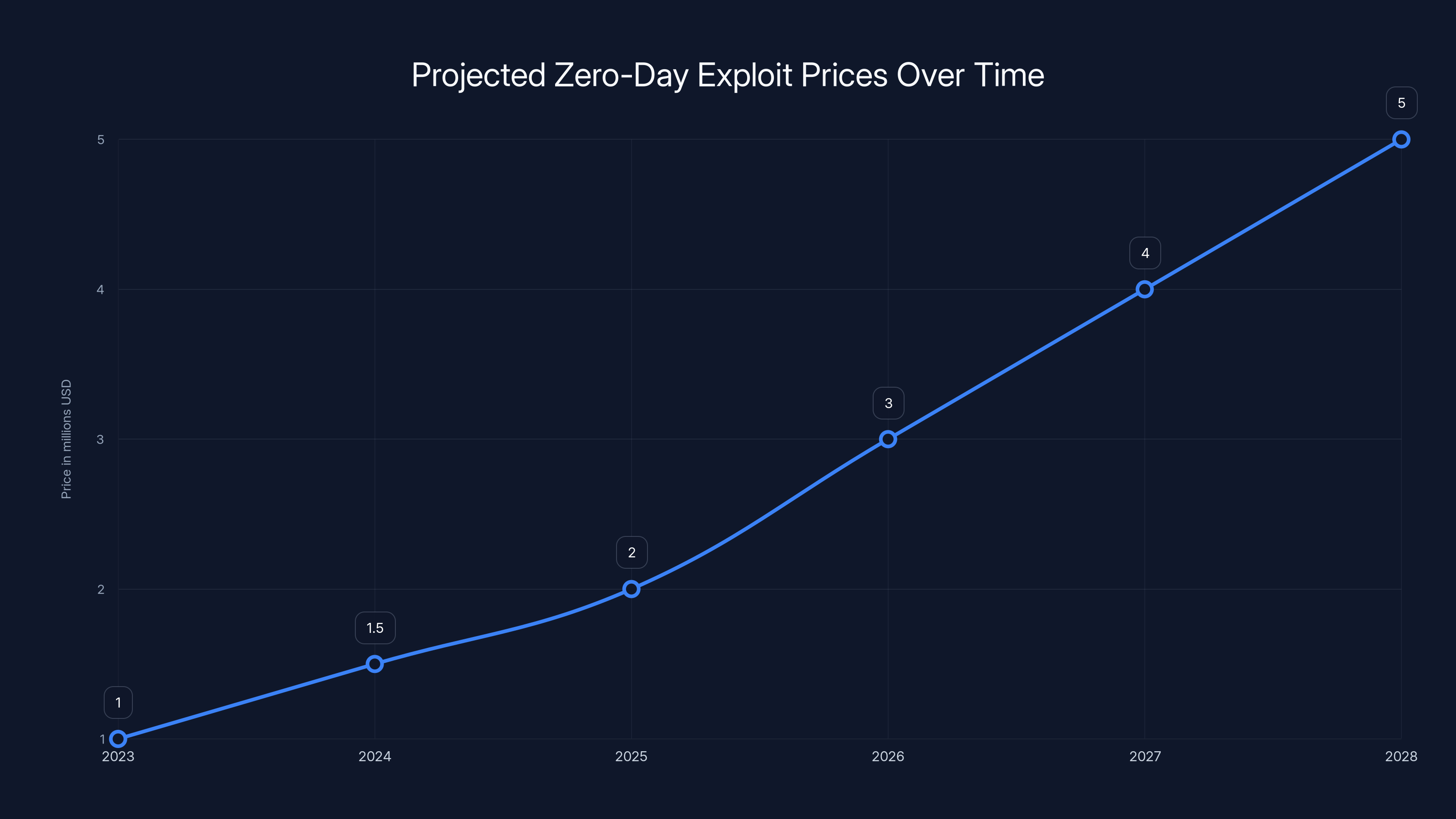

Zero-day exploits for iOS and BlackBerry can reach up to

Who Was Jeffrey Epstein's "Personal Hacker"?

The confidential informant told the FBI in 2017 that Epstein's hacker was an Italian national born in Calabria, a region in southern Italy with a well-documented history of organized crime connections. This detail alone is significant. Calabria is home to the 'Ndrangheta, one of the world's most powerful criminal organizations, with operations spanning drugs, weapons, money laundering, and increasingly, cybercrime.

Whether the hacker had ties to organized crime networks is unknown from the document. But the geographic origin raises legitimate questions about potential connections. What's clear is that this wasn't some bedroom coder messing around with bug bounty programs. This was a sophisticated operator with rare, elite-level capabilities.

According to the informant, the hacker specialized in finding vulnerabilities in three specific targets: iOS devices, BlackBerry phones, and the Firefox web browser. Why these three? That's the million-dollar question—literally. Each of these platforms was (and is) widely used by security-conscious individuals, corporations, and government agencies.

iOS vulnerabilities would be worth exponentially more because iPhones are the preferred devices of high-net-worth individuals, corporate executives, and government officials. Breaking into an iPhone means accessing emails, messages, location data, call logs, and any information stored on the device. Apple's reputation for security made iOS vulnerabilities exceptionally rare and valuable.

BlackBerry phones, while less prevalent today, were the gold standard for secure communication during the 2000s and 2010s. Government agencies, financial firms, and intelligence services relied on BlackBerry's encryption. A zero-day in BlackBerry could unlock access to some of the most sensitive communications on the planet.

Firefox vulnerabilities would allow remote code execution on millions of computers and browsers worldwide. Unlike iOS or BlackBerry, Firefox runs on countless devices, making it a broader target with massive potential impact.

The fact that this hacker focused on these three specific platforms suggests he understood the cyber weapons market intimately. He wasn't developing exploits randomly. He was targeting the highest-value systems used by the organizations most willing to pay for access.

But who exactly was this person? The FBI document doesn't identify him by name. Law enforcement agencies often withhold the identities of targets, especially if investigations are ongoing or if revealing the identity could compromise intelligence operations. The informant's description—Italian, from Calabria, skilled in finding iOS/BlackBerry/Firefox vulnerabilities—is detailed enough to be valuable, but vague enough to preserve operational security.

The remaining question is whether this person is still alive, still operating, or whether law enforcement eventually caught him. The 2025 release of this information suggests that either the investigation concluded or enough time has passed that secrecy is no longer critical. But without confirmation from the FBI or DOJ, we're left speculating.

Estimated data shows cyber surveillance and the cyber weapons market as major components of modern cybercrime, highlighting the intersection with government oversight and infrastructure vulnerability.

The Zero-Day Market: Why These Exploits Are Worth Millions

To understand the significance of Epstein's hacker selling zero-days, you need to understand what zero-days are and why they command such astronomical prices in the underground market.

A zero-day vulnerability is a software flaw that's unknown to the software vendor and the public. The term comes from the idea that developers have "zero days" to patch it before it can be exploited. Once discovered, a zero-day is effectively a key that unlocks a previously secure system.

In the legitimate cybersecurity world, responsible researchers discover vulnerabilities and report them to the software company, often receiving a bug bounty (payment) for the disclosure. Apple's program, for example, can pay up to $1 million for certain high-severity iOS bugs. Google, Microsoft, and other major tech companies have similar programs.

But in the underground market, prices are often dramatically higher. A zero-day for iOS might sell for

Why are governments and intelligence agencies willing to pay such extraordinary sums?

Surveillance capabilities. A zero-day is a surveillance weapon. If you control an iOS zero-day, you can silently install surveillance software on an iPhone without the user knowing. You can access emails, messages, location data, and even turn on the microphone and camera remotely. For intelligence agencies, this is equivalent to having a bug planted in someone's pocket, 24/7.

Offensive operations. Governments use zero-days for cyber attacks against adversaries. Disrupting critical infrastructure, stealing secrets, or degrading an enemy's communications capabilities all depend on the ability to penetrate supposedly secure systems. Zero-days are the ammunition for cyber warfare.

Competitive advantage. In intelligence operations, having access to a zero-day that other countries don't have is a massive advantage. It allows you to spy on targets while remaining undetected. Once a zero-day becomes public or widely known, its value collapses because vendors release patches and security researchers develop detection methods.

Price transparency doesn't exist. Unlike the legitimate bug bounty market, the underground zero-day market operates without published prices. A buyer might pay

The economics of zero-day trading also explain why sophisticated hackers like Epstein's alleged employee would engage in this activity. If you can find 5-10 exploitable vulnerabilities per year and sell each for

But here's what's critical to understand: each zero-day sold represents a potential breach in global cybersecurity infrastructure. Every exploit sold to a government is an exploit that could potentially be stolen, leaked, or misused. Every vulnerability sitting in a government's arsenal is a potential weapon that could fall into the hands of terrorists, criminal organizations, or rogue actors.

The fact that Epstein's hacker was allegedly selling to multiple countries simultaneously means he was willing to compromise security across multiple nations. This isn't patriotism. This isn't working for your country's intelligence service. This is pure commercialism—selling the same weapon to whoever pays the most.

The Buyers: Who Purchased These Zero-Days?

According to the FBI informant, Epstein's hacker sold zero-day exploits to at least four distinct buyers or buyer categories:

1. An Unnamed Central African Government

The informant mentions sales to "an unnamed central African government," which the released document doesn't identify. This is one of the most intriguing redactions because it raises questions about which country we're talking about.

Central Africa includes countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Chad, Central African Republic, Republic of Congo, Cameroon, and several others. Some of these nations have notoriously weak governance, while others are engaged in active conflicts or have documented histories of human rights abuses.

Why would a hacker sell cyber weapons to a central African nation? Several possibilities:

Financial desperation. Some central African governments might lack the resources to develop their own cyber capabilities but have sufficient funds (often from foreign aid, natural resource revenues, or illicit sources) to purchase them on the black market.

Regional conflict. Some of these nations are involved in active territorial disputes, ethnic conflicts, or wars. Acquiring cyber weapons could be part of military strategy.

Political repression. Several central African governments have documented histories of monitoring and suppressing political opposition. Cyber weapons would be valuable tools for surveillance and control.

Third-party beneficiary. The central African government might not be the end user. A foreign intelligence agency could have purchased the exploits through a proxy, using the central African nation as an intermediary to obscure the true buyer.

The refusal to identify which nation this was suggests either ongoing investigations, diplomatic sensitivity, or intelligence operations that are still active. If the actual buyer were identified, it could reveal sources and methods of intelligence gathering that the U.S. government wants to keep secret.

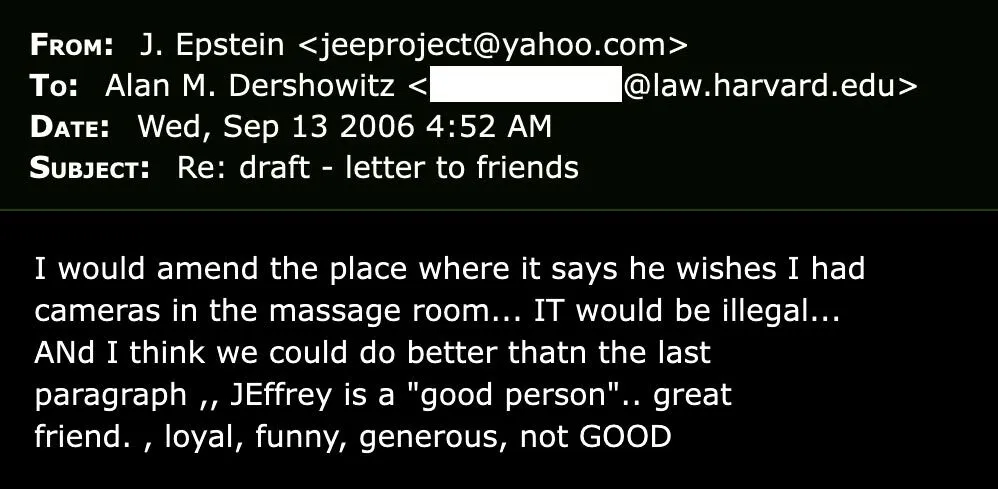

2. The United Kingdom

The informant explicitly mentions the United Kingdom as a buyer of zero-days from Epstein's hacker. This is less surprising than sales to central Africa, given that the U.K. has a sophisticated intelligence apparatus (GCHQ, MI6, MI5) and substantial resources for cyber operations.

British intelligence agencies have a documented history of conducting sophisticated cyber espionage. They've been involved in joint operations with the U.S. National Security Agency and have their own extensive signals intelligence capabilities. Purchasing zero-days for specific targets would be consistent with their operations.

What's interesting here is that this was disclosed in an FBI document about Jeffrey Epstein. Why would the U.S. government publicly (even in a partially redacted way) acknowledge that a British intelligence agency purchased cyber weapons from someone connected to an American sex trafficker?

One possibility: The U.K. might not have known who was ultimately behind the sale. Intelligence agencies often purchase zero-days through intermediaries and brokers specifically to maintain deniability. The hacker might have sold through layers of cutouts, and the U.K. buyer might have believed they were purchasing from a legitimate security firm or researcher.

Another possibility: By the time this document was released in 2025, the transactions were old enough (pre-2017 informant report) that officially acknowledging them wasn't considered operationally damaging.

3. The United States

The most revealing aspect of this disclosure is that the U.S. government itself was also purchasing zero-days from Epstein's hacker. This creates a bizarre and troubling situation: American intelligence and law enforcement agencies were knowingly or unknowingly acquiring cyber weapons from someone employed by a major criminal.

This revelation has profound implications. If U.S. agencies were buying from this source, questions arise:

Did they know Epstein was connected? If American intelligence agencies knowingly purchased cyber weapons from someone employed by Epstein, they would have been complicit in indirectly funding his criminal enterprise through the hacker's payments.

How many exploits did the U.S. acquire? The document doesn't specify the scale, but the U.S. intelligence community is one of the largest buyers of cyber weapons globally. The number could be significant.

Where are those exploits now? Have they been used for surveillance operations? Have they been inadvertently leaked? Are they still in active use?

What was the procurement mechanism? Did the NSA, CIA, or another agency contract directly with the hacker? Or did they purchase through intermediaries?

The U.S. government's typical response to questions about purchasing cyber weapons is "no comment" or claims of national security. The FBI declined to comment on this matter when reached, and the DOJ didn't respond to requests for clarification.

The fact that this information was released at all suggests that the statute of limitations on the operational sensitivity has passed, or that higher priorities (like transparency around the Epstein investigation) outweighed intelligence concerns.

4. Hezbollah

The most shocking buyer mentioned in the document is Hezbollah, the Lebanon-based militant organization designated as a terrorist group by the United States and several other countries. According to the informant, Hezbollah purchased at least one zero-day exploit from Epstein's hacker and paid with "a trunk of cash."

This transaction is significant for multiple reasons.

It's criminal funding. If true, Epstein's hacker was directly funding a terrorist organization. The profits from selling zero-days to Hezbollah represented financial support for an organization involved in militant operations, suicide bombings, and other violence.

It's destabilizing. Giving Hezbollah cyber weapons elevates their operational capabilities. They could use these exploits for surveillance of Israeli targets, Lebanese government officials, or security services. They could potentially disrupt infrastructure or conduct cyber attacks against military systems.

It represents international criminal enterprise. The sale connects an Italian hacker, an American crime boss, a Middle Eastern militant organization, and intelligence agencies across multiple countries in a single transaction. It's a glimpse into how serious criminal enterprise actually operates globally.

The payment method is telling. A "trunk of cash" suggests the transaction was conducted outside formal banking systems, reinforcing the underground nature of the market. No wire transfers, no cryptocurrency trails, just physical currency. This makes investigation and prosecution more difficult.

Hezbollah's interest in zero-days makes sense operationally. The organization operates in multiple countries, requires secure communications, and needs to conduct surveillance of adversaries. Cyber weapons would be valuable for these operations.

Estimated data suggests a diverse range of buyers for zero-day exploits, with central African governments and financially desperate governments being the primary purchasers.

How Zero-Days Are Developed: The Technical Reality

Understanding how Epstein's hacker actually developed these zero-day exploits requires understanding the technical skills involved and the methods used to discover vulnerabilities.

Finding Vulnerabilities in Complex Systems

Finding a zero-day is not like discovering a gold nugget lying on the ground. It requires extraordinary technical skill, deep understanding of how software works at a fundamental level, and either significant luck or a specific methodology.

There are generally two approaches to finding vulnerabilities:

Reverse engineering and source code analysis. This involves taking compiled software and attempting to convert it back into human-readable code (reverse engineering) or, in cases where source code is available (open-source software like Firefox), directly analyzing it for flaws. The researcher looks for common vulnerability patterns: buffer overflows, integer overflows, use-after-free errors, race conditions, and logic flaws that could be exploited.

Firefox, being open-source, would be theoretically easier to analyze for vulnerabilities than iOS or BlackBerry, which have proprietary, closed-source code. However, even with source code available, finding exploitable vulnerabilities requires understanding the broader security architecture and how specific bugs could be chained together to achieve remote code execution or privilege escalation.

Fuzzing and dynamic analysis. This approach involves feeding unexpected or random inputs into software and observing how it responds. If the software crashes or behaves unexpectedly, that's a potential vulnerability. Modern fuzzing tools can generate millions of test cases and identify edge cases that developers missed during testing.

For iOS and BlackBerry, where source code wasn't readily available, fuzzing and dynamic analysis would have been primary techniques. The hacker would need access to devices, development tools, and the ability to test extensively without triggering security alerts.

The iOS/BlackBerry/Firefox Specialization

The fact that Epstein's hacker specialized specifically in iOS, BlackBerry, and Firefox suggests he had developed efficient methodologies for finding vulnerabilities in these specific platforms. Maybe he had tools or techniques that worked particularly well against these systems. Maybe he had access to insider information or documentation that gave him advantages.

Specialization matters enormously in vulnerability research. A researcher who focuses on one platform for years develops deep knowledge that's difficult to replicate. They understand the architecture, the common developer mistakes, the patterns that lead to exploitable flaws. This specialization also makes their exploits more valuable because they're the result of focused, sophisticated research rather than broad, shallow analysis.

Chain of Exploitation

A sophisticated zero-day is often not a single vulnerability but a chain of vulnerabilities that work together to achieve the attacker's goal. For example:

- Vulnerability #1 might allow reading memory outside of intended bounds

- Vulnerability #2 might allow writing to protected memory regions

- Vulnerability #3 might allow executing code with elevated privileges

Chaining these together could allow remote code execution with system-level privileges. Developing these chains requires understanding not just individual vulnerabilities but how they interact within the broader system architecture.

Epstein's hacker, if he was finding iOS vulnerabilities, would likely be developing these chains specifically targeting the iOS security model. He'd be finding flaws in how iOS manages memory, how it enforces code signing, how it implements sandboxing. Each vulnerability has value individually, but together they might enable a complete device compromise.

The Broader Zero-Day Market Ecosystem

Epstein's hacker wasn't operating in isolation. He was part of a larger ecosystem of vulnerability researchers, brokers, intelligence agencies, and criminal organizations that constitutes the global cyber weapons market.

Legitimate vs. Underground Markets

There are two distinct markets for zero-days: the legitimate market (bug bounty programs, coordinated disclosure) and the underground market (government procurement, criminal sales).

The legitimate market operates openly. Apple, Google, Microsoft, Facebook, and other major tech companies publish their bug bounty programs. Researchers can submit vulnerabilities and receive payment for responsible disclosure. These programs incentivize security research and help companies patch vulnerabilities before criminals discover them.

Underground market transactions, by contrast, are secret, unregulated, and criminal. A researcher might sell the same vulnerability to multiple parties, or might sell to the highest bidder without any concern for how it will be used. Once sold, the vulnerability typically remains secret and unpatched, leaving users vulnerable.

The underground market is driven by extreme demand. Governments pay millions for capabilities that the legitimate market can't provide. A government agency wants a zero-day that's exclusive to them, not disclosed to the vendor and patched. The legitimate market provides the opposite: vulnerability disclosure that leads to patches that eliminate the vulnerability for everyone.

Epstein's hacker was operating in the underground market. His exploits weren't submitted to Apple or Mozilla for bug bounties. They were sold to governments and militant organizations for millions of dollars, kept secret, and deployed for surveillance and cyber warfare.

Brokers and Intermediaries

Vulnerability researchers rarely sell directly to end buyers. Instead, they typically work through brokers or intermediaries who handle the transaction, negotiate prices, and provide some degree of anonymity and security.

These brokers might be:

Legitimate security firms that have been approached by government agencies to facilitate purchases of zero-days.

Criminal organizations that operate in the cyber weapons space as their primary business.

Individual entrepreneurs who have developed relationships with both researchers and buyers and take a commission on transactions.

The fact that Epstein's hacker sold to multiple countries simultaneously suggests either direct relationships with government buyers or work through one or more brokers who handled the various transactions.

Using intermediaries provides plausible deniability. If the hacker was arrested and questioned, he might claim he was selling to legitimate security researchers or private contractors, not government intelligence agencies. The buyers, meanwhile, could claim they were purchasing from private firms, not directly engaging in cyber weapons trafficking.

Intelligence Agencies as Buyers

Intelligence agencies are the primary purchasers of zero-days in the underground market. The NSA, CIA, GCHQ, China's MSS, Russia's FSB and GRU, Israel's Unit 8200, and agencies from dozens of other countries actively purchase zero-days or have programs to acquire them.

These agencies face a fundamental problem: they need exploits and vulnerabilities to conduct cyber espionage and offensive operations, but they can't publicly declare this. So they develop covert procurement channels, use proxies and intermediaries, and operate through shell companies or classified budgets that aren't subject to public scrutiny.

The fact that U.S. intelligence agencies were willing to purchase from Epstein's hacker (whether knowingly or unknowingly) illustrates how compartmentalized these procurement operations are. The person making the purchase decision might not know the full background of the seller. The transaction might be handled through a contractor or intermediary who shields the ultimate buyer from direct involvement.

The timeline shows the increasing impact of cyber weapons incidents, with Stuxnet in 2010 marking a pivotal point. Estimated data based on historical context.

The Payment: Why "A Trunk of Cash"?

The informant's statement that Hezbollah paid with "a trunk of cash" reveals important details about how high-value underground transactions are actually conducted.

Avoiding Financial Surveillance

Modern governments have sophisticated financial surveillance capabilities. Large wire transfers, cryptocurrency transactions, and other electronic money movements can be tracked, monitored, and potentially intercepted by intelligence agencies.

Cash payments, by contrast, are effectively invisible to electronic surveillance systems. A physical exchange of currency leaves no digital footprint. This is why criminal organizations, terrorist groups, and traffickers have historically preferred cash for large transactions.

The Logistics Problem

A "trunk of cash" raises practical questions: How much cash? How was it transported? Who made the delivery? How did the parties verify the amount?

For a zero-day that might have been worth

This wasn't money transferred electronically. Someone physically delivered a large quantity of cash to a hacker, presumably in a secure location, and conducted a face-to-face transaction. This kind of transaction requires tremendous trust between parties, coordination of logistics, and significant personal risk for both sides.

What It Reveals About the Hacker

The fact that Epstein's hacker was willing to accept cash payment from Hezbollah reveals something important about his character and motivations. He wasn't a patriot selling to his government for lower compensation. He wasn't primarily concerned about political ideology or geopolitical alignment. He was motivated purely by money and willing to accept payment from any buyer, including organizations the U.S. government designates as terrorist groups.

This suggests a mercenary mindset. The hacker's primary concern was maximizing his income, not considering the consequences of his actions. By selling to Hezbollah, he was potentially funding suicide bombings, rocket attacks, and militant operations. But that didn't factor into his decision-making.

The Epstein Connection: How This Fits Into Larger Criminality

The most puzzling aspect of this revelation is: Why did Jeffrey Epstein employ a cyber weapons trader?

Epstein's public profile was as a financier. His criminal enterprise was sex trafficking, involving the recruitment, exploitation, and abuse of minors. What does that have to do with zero-day exploits and government cyber weapons?

Surveillance and Blackmail

One explanation: Epstein used cyber surveillance capabilities for leverage over victims, associates, and potential adversaries.

If Epstein had access to zero-day exploits, he could deploy them against people involved in his criminal network. Wives of prominent men could have their iPhones compromised, revealing affairs or financial fraud. Prosecutors could have their communications intercepted. Victims could be monitored to prevent them from talking to authorities.

Zero-days are powerful surveillance tools. They allow silent, undetectable access to a target's device. For a criminal enterprise operating at Epstein's scale, controlling information about associates, maintaining secrecy, and anticipating law enforcement activity would be crucial to survival.

Epstein's hacker could have been providing exactly these capabilities: the ability to spy on anyone, anytime, without detection.

Financial Intelligence and Money Laundering

Epstein's financial enterprise was complex and partly obscured. By using zero-days, his hacker could potentially:

Monitor competitors. If Epstein was engaged in any legitimate or semi-legitimate financial activities alongside his criminal enterprise, knowing what competitors and adversaries were planning would be valuable.

Intercept communications. By compromising phones and computers of law enforcement officials, prosecutors, or journalists investigating him, Epstein could potentially learn about investigations before they became public.

Access banking systems. While speculative, a sophisticated cyber weapon could potentially be used to access banking infrastructure, facilitating money laundering or financial fraud alongside the trafficking enterprise.

The Hacker as Criminal Associate

Alternatively, the hacker might simply have been another criminal associate in Epstein's extensive network. Epstein's enterprise involved wealthy associates from finance, politics, entertainment, and other sectors. Adding a sophisticated hacker to this network makes sense from an operational perspective.

The hacker might have provided multiple services:

- Surveillance capabilities for operational security

- Access to target systems for blackmail or extortion

- Communications security (secure phones, encrypted channels)

- Counter-intelligence against law enforcement monitoring

Estimated data suggests iOS vulnerabilities could be worth up to

Red Flags and Questions the FBI Investigation Left Unanswered

The released document raises more questions than it answers, and the silence from federal agencies is deafening.

Identity and Current Status

Who exactly was this hacker? Why hasn't he been identified in any public criminal proceedings or indictments? Is he still alive? Has he been arrested?

The document doesn't answer any of these questions. If the hacker was caught and prosecuted, you'd expect some public record of charges, trial, or conviction. The absence of any such information suggests either:

The investigation is ongoing. The hacker might still be at large, and the FBI is actively seeking him. Releasing his identity could compromise the investigation.

The investigation concluded differently. The hacker might have cooperated with authorities, received immunity, or been released. Making this public could be politically embarrassing or operationally sensitive.

International complications. The hacker might be outside U.S. jurisdiction, and revealing details about him could create diplomatic issues with the country harboring him.

Exploitation of Purchased Zero-Days

What happened to the zero-days that were sold? Are they still being used by the governments that purchased them? Have they been patched? Have they been leaked or stolen?

Apple, Mozilla, and the technology community would presumably want to know if zero-days were sold to foreign governments. If those exploits are still unpatched, millions of people are potentially vulnerable. If they've been patched, Apple and Mozilla would want to know about it for historical purposes.

The fact that this information isn't publicly available suggests either operational sensitivity or a lack of investigation into what happened to the exploits after they were sold.

Other Epstein Associates

Did other members of Epstein's network use the hacker's services? Did the hacker work exclusively for Epstein, or did he provide services to other criminals and organizations?

If the hacker had a broader customer base, there could be dozens or hundreds of victims of cyber espionage connected to his activities. Understanding the full scope of his operations would be important for justice and understanding the broader threat.

Why Was This Released?

The most fundamental question: Why did the Department of Justice release this information in 2025? What changed that made officials willing to disclose Epstein's connection to a cyber weapons trader?

The official explanation is that the DOJ released 3.5 million additional pages as part of a legal requirement to make Epstein-related documents available. But selection of what gets released and what stays redacted is a choice. Someone decided this information was important enough to make public.

Possible reasons:

- The statute of limitations on some crimes has passed

- Ongoing investigations have concluded

- The operational value of keeping it secret has expired

- Political pressure or transparency advocates forced the issue

- The information leaked anyway and the DOJ decided to get ahead of it

Without explicit guidance from the government, we're left speculating.

Implications for Cybersecurity and National Defense

This revelation has profound implications for how we think about cybersecurity, government procurement, and the regulation of cyber weapons.

The Vulnerability of Critical Infrastructure

If Epstein's hacker was selling zero-days to governments, critical infrastructure worldwide could be vulnerable. Water treatment plants, power grids, financial systems, and communications networks all run on software that might have exploitable flaws.

Intelligence agencies purchase zero-days specifically to exploit these systems in adversaries' countries. But once a zero-day is purchased, it could be stolen by other nations, leaked by insiders, or obtained by criminal organizations. The longer a zero-day remains secret and unpatched, the greater the risk of unauthorized use.

This creates a security paradox: to defend critical infrastructure, you need to patch vulnerabilities. But governments often deliberately avoid patching zero-days they've purchased, keeping them secret so they can use them for their own purposes. This leaves civilian populations vulnerable to attacks using the same exploits.

The Need for Transparency

Currently, there's no transparency about which zero-days governments possess or how they're using them. The intelligence community operates under the assumption that secrecy is necessary for national security. But absolute secrecy also enables abuse, corruption, and misuse.

A more transparent system might:

Require disclosure of major zero-day purchases. Not the technical details, but acknowledgment that the purchase occurred and some limited information about what was acquired.

Establish oversight. An independent body could verify that zero-days are being used only for authorized national security purposes, not for domestic surveillance or other abuses.

Mandate patching timelines. After a certain period (e.g., 5 years), zero-days would be required to be disclosed to the vendor so that patches can be developed and deployed.

These reforms would create tension between secrecy and security, between national defense and transparency. But the current system, where intelligence agencies hoard exploits indefinitely and civilians remain vulnerable, isn't sustainable long-term.

The Regulation Gap

Currently, there are few laws specifically regulating the sale or trade of zero-day exploits. The U.S. has export controls on cyber weapons, but enforcement is weak and inconsistent. Intelligence agencies themselves are largely exempt from these restrictions.

Closing this gap would require:

Defining cyber weapons legally. What exactly constitutes a cyber weapon? How do we distinguish between legitimate security research and criminal cyber weapons trafficking?

Establishing international agreements. Similar to nuclear weapons treaties or chemical weapons conventions, there could be international agreements limiting the development and sale of cyber weapons.

Enforcing against criminals. Epstein's hacker should have been prosecuted for trafficking in cyber weapons, not simply mentioned in an FBI document. But prosecutions are rare because the legal framework for charging people with this crime is underdeveloped.

Until these gaps are addressed, the market for zero-days will continue operating in shadows, enabling governments to spy on each other and criminals to profit from security vulnerabilities.

The price of zero-day exploits is expected to rise significantly, potentially reaching $5 million by 2028 due to increased demand and competition. (Estimated data)

Historical Context: The Cyber Weapons Trade and Previous Incidents

Epstein's hacker wasn't the first person caught up in the cyber weapons trade. Understanding the history provides context for how prevalent these operations are.

Stuxnet and Revealed Government Operations

In 2010, security researchers discovered Stuxnet, a sophisticated computer worm that targeted Iranian nuclear facilities. Later investigation revealed that Stuxnet was developed by the U.S. and Israel and deployed as part of an offensive cyber operation against Iran's nuclear program.

Stuxnet's discovery was significant because it provided public proof that governments were developing and using cyber weapons at scale. Before Stuxnet, cyber warfare was mostly theoretical. After it, everyone understood that major powers had significant offensive cyber capabilities.

Stuxnet used multiple zero-day vulnerabilities. Some were later disclosed, allowing researchers to analyze the malware and understand the sophistication. It represented the kind of capability that Epstein's hacker was trafficking in, but at a nation-state level of complexity.

The Shadow Brokers Leaks

In 2016, a group calling themselves "The Shadow Brokers" released thousands of pages of documents allegedly stolen from the NSA. The leak included exploits, malware, and information about the NSA's cyber weapons arsenal.

The leak was shocking because it revealed the kinds of tools the NSA had developed and the extent of their surveillance capabilities. It suggested that NSA cyber weapons were more sophisticated and widespread than publicly known.

The incident raised a terrifying question: if the NSA's tools could be stolen, what about zero-days purchased from outside sources? Could a single insider or successful hack compromise the entire arsenal of cyber weapons the U.S. government had acquired?

The Equation Group

The Equation Group (believed to be the NSA or a closely affiliated organization) was revealed through the Shadow Brokers leaks to have developed an array of sophisticated exploits and malware. Some of these tools targeted Android devices, Windows systems, and various other platforms.

The Equation Group's arsenal included zero-days and sophisticated offensive capabilities that had been developed over years and represented billions of dollars in research and development investment.

Exploit Dealers and Professional Security Firms

Companies like Zerodium, Intigriti, and others have emerged as legitimate brokers in the zero-day market. These firms purchase exploits from researchers and sell them to government agencies and private companies.

Zerodium, for example, has published prices for zero-days: up to

But underground dealers continue to exist as well, operating without the transparency or constraints of legitimate firms. Epstein's hacker likely operated through informal channels, dealing directly with buyers or through criminal intermediaries.

The Investigative Gaps and What Should Happen Next

The FBI's investigation into this aspect of Epstein's enterprise seems incomplete based on the released documents. Several investigative threads should be pursued.

Identifying the Hacker

The first priority should be identifying the hacker by name. Law enforcement agencies should have enough information from the informant to narrow down suspects significantly. An Italian national, born in Calabria, with elite-level skills in finding iOS/BlackBerry/Firefox vulnerabilities—this isn't a huge population.

Once identified, authorities could:

- Determine if he's still alive

- Check if he's been arrested or prosecuted

- Identify his current activities

- Locate and interview known associates

- Investigate financial records to determine the extent of his activities

Following the Money

Cash payments might not leave electronic trails, but they often leave other evidence:

- Logistics records of transporting large sums

- Witness accounts of meetings or exchanges

- Changes in lifestyle or unexplained wealth

- Bank deposits of money from known criminal associates

Financial forensics could potentially reveal the scale of the hacker's operations and his connections to organized crime.

International Cooperation

If the hacker is Italian, Interpol and Italian law enforcement should be involved. If he's operating in another country, that country's intelligence service or police should be engaged.

The countries that purchased the zero-days (U.K., U.S., central African nation, plus Hezbollah connections) all have interests in locating and either prosecuting or controlling the hacker.

Disclosing to Vendors

Apple, Mozilla, and BlackBerry (or its successor companies) should be informed of the exploits sold from their platforms, if they haven't been already. Even without identifying specific vulnerabilities, vendors need to know that their platforms had zero-days that were sold to foreign governments and militant organizations.

This information could help them:

- Improve their security practices to prevent similar exploitation

- Audit their systems for evidence of compromise using these tools

- Develop detection methods for surveillance using known exploit patterns

Transparency to the Public

Some details about this investigation should be made public, not to compromise ongoing operations, but to inform the public about risks to their devices.

For example: "The FBI has information that unpatched zero-days in iOS versions prior to 14.x and Firefox versions prior to 92.x were sold to foreign governments between 2012 and 2017. If you used devices with these versions during that period, your communications may have been compromised."

This wouldn't reveal sources and methods, but it would inform users of potential historical vulnerabilities.

The Broader Implications: Criminal Enterprise and Cyber Weapons

Epstein's employment of a cyber weapons trader reveals something important about the structure of sophisticated criminal enterprises. They're not monolithic organizations focused on a single crime. They're complex networks that intersect with legitimate business, government, and international trade.

Epstein's enterprise included:

- Sex trafficking and child abuse

- Money laundering

- Corruption of government officials

- Coercion and blackmail

- Cyber surveillance and espionage

- International arms and weapons dealing (presumably, given the hacker's activities)

This wasn't a simple criminal operation. This was a complex, multi-faceted enterprise operating across multiple countries and involving sophisticated operational security, including cyber capabilities.

The revelation that intelligence agencies were purchasing from someone connected to this enterprise, even unknowingly, demonstrates the risks of operating in murky procurement channels. It also raises questions about oversight and accountability in intelligence agencies' acquisition of cyber weapons.

Future investigations into criminal enterprises need to account for cyber capabilities. A high-level organized crime figure, a corrupt government official, or a terrorist organization that employs a sophisticated hacker has dramatically enhanced capabilities for surveillance, blackmail, fraud, and operational security.

The Zero-Day Market's Future

As cyber weapons become more important to national defense and more valuable in the underground market, the demand for zero-days will only increase. What can we expect moving forward?

Increased Sophistication

Zero-day researchers will develop more sophisticated techniques for finding vulnerabilities. Machine learning and automated vulnerability discovery will likely play an increasing role. The hacker who can find vulnerabilities faster and more efficiently than competitors will be the most successful.

Higher Prices

As governments compete for exclusive exploits, prices will likely continue rising. A zero-day that costs

More Buyers

Nations that don't currently have sophisticated cyber capabilities will increasingly seek to acquire them. As cyber weapons become as important as military hardware, more countries will enter the market, raising competition for exploits.

Leaked and Repurposed Exploits

Exploits will continue to be stolen, leaked, and repurposed. The Shadow Brokers release showed that government-owned exploits can be stolen and released to the public. As more exploits are developed and stored, the risk of leaks increases.

Regulation and Enforcement

Governments will attempt to regulate the market, but underground dealers will continue operating. The same way that governments attempt to stop drug trafficking, weapons smuggling, and human trafficking—with limited success—they'll attempt to stop cyber weapons trafficking. But the economic incentives are powerful, and the tools are difficult to control because they're information, not physical objects.

Lessons for Digital Security and Privacy

For ordinary users, this revelation has implications for how you should think about device security and privacy.

Your Device Can Be Compromised Silently

If a zero-day is deployed against your phone, you'll have no indication that it happened. Your device will function normally while being monitored. Your emails will be read, your messages intercepted, your location tracked, your camera and microphone potentially activated without your knowledge.

Zero-day exploits are the antithesis of transparency. There's no way for you to know if you've been targeted.

Device Updates Are Critical

The only defense against zero-days is regular software updates. Once a vulnerability is disclosed and patched, you're protected against known exploits. But unpatched vulnerabilities remain dangerous.

Updating your device regularly isn't just about fixing bugs. It's about closing security gaps that could be exploited by sophisticated attackers.

Privacy Is Conditional

If you're a high-value target (government official, journalist, activist, prominent business person), assume that sophisticated actors are attempting to compromise your communications. Even with security best practices, a zero-day could defeat your defenses.

Very high-risk individuals sometimes use specialized, hardened devices or air-gapped systems specifically to avoid cyber weapons. For most people, this level of security is impractical, but it's worth understanding that some threats are nearly impossible to defend against.

Government Surveillance Is Real

This document provides confirmation that governments purchase and use cyber weapons to surveil targets. This isn't theoretical or speculative. The U.S. government, the U.K., and other nations actively develop and deploy cyber surveillance capabilities.

This should inform your thinking about what privacy you can reasonably expect in an era of ubiquitous surveillance technology.

FAQ

What is a zero-day exploit and why is it so valuable?

A zero-day exploit is a previously unknown software vulnerability that hasn't been patched by the vendor. It's called "zero-day" because developers have zero days to patch it before it can be exploited. Zero-days are extremely valuable in both legitimate cybersecurity markets and underground markets because they provide unfettered access to systems. Intelligence agencies and criminal organizations pay millions for zero-days because they enable surveillance, cyber attacks, and espionage without detection. Once a zero-day is patched, its value collapses because the vulnerability no longer exists in updated systems.

How does an intelligence agency use a zero-day exploit?

Intelligence agencies deploy zero-days against specific high-value targets to achieve surveillance or offensive objectives. For example, a zero-day in iOS could be used to compromise an iPhone belonging to a foreign government official, allowing the agency to read their emails, intercept their messages, and track their location. Alternatively, a zero-day in critical infrastructure software could be used to penetrate and sabotage an adversary's power grid or communication systems. The agency must keep the zero-day secret to maintain its advantage. Once patched, it can no longer be used.

What does the Epstein case reveal about the cyber weapons market?

The case reveals that the cyber weapons market is real, operates globally, and involves not just governments but also criminal enterprises and terrorist organizations. Epstein's employment of a personal hacker who sold zero-days to governments, the U.K., and Hezbollah demonstrates that sophisticated criminals have access to the same cyber weapons that intelligence agencies use. It also shows that procurement channels can be murky, with intelligence agencies potentially purchasing from sources connected to criminal enterprises without fully understanding the supply chain.

Is it illegal to sell zero-day exploits?

The legality depends on jurisdiction and the buyer. In the United States, selling cyber weapons or exploits to foreign governments or terrorists can violate export control laws and terrorism statutes. However, selling zero-days to legitimate security firms or through bug bounty programs is legal. Many countries lack specific laws criminalizing zero-day sales. Intelligence agencies themselves are exempt from many restrictions and actively purchase zero-days. This legal gray area is one reason why the underground market continues to thrive.

What happened to the hacker that Epstein employed?

The FBI document does not identify the hacker by name or provide details about his current status. It's unclear whether he was ever apprehended, whether investigations into him are ongoing, or whether he continues operating. The refusal to disclose this information suggests either ongoing investigations, diplomatic sensitivity, or intelligence operations that the government wants to keep secret.

Could the zero-days sold to foreign governments still be used?

Yes, potentially. If a government purchased a zero-day and never disclosed it to the software vendor, the vulnerability would remain unpatched and exploitable in older versions of the software. However, most devices update regularly, and patched versions would be protected. The exploits would primarily be useful against devices running older, unpatched versions of iOS, BlackBerry, or Firefox. Given that this occurred in the mid-2010s or earlier, modern devices would likely be protected, but legacy systems could still be vulnerable.

What can users do to protect themselves from zero-day exploits?

Perfect protection against zero-days is impossible because they're unknown to everyone except the attacker. However, users can reduce risk by keeping devices updated with the latest security patches, avoiding suspicious links and attachments, using strong authentication, and being aware that high-risk individuals (journalists, activists, government officials) may be targeted by sophisticated attackers. For extremely high-risk individuals, specialized security measures like air-gapped computers or hardened devices might be necessary. For most people, regular security updates are the most effective defense.

Why does the U.S. government purchase zero-days if it wants them patched?

Governments purchase zero-days specifically because they don't want them patched. Intelligence agencies want exploits that remain secret and effective for conducting surveillance and cyber warfare against adversaries. This creates a tension between national defense (developing cyber weapons) and cybersecurity (patching vulnerabilities to protect civilian systems). Governments typically keep purchased zero-days secret indefinitely, which leaves civilians vulnerable to attacks using the same exploits.

Conclusion: The Intersection of Crime, Technology, and Surveillance

The revelation that Jeffrey Epstein employed a personal hacker who trafficked in zero-day exploits connects several dots that paint a disturbing picture of modern criminal enterprise and government cyber operations.

First, it demonstrates that sophisticated criminals don't operate in silos. They build complex networks that intersect with technology, finance, intelligence operations, and international trade. Epstein's enterprise wasn't just about trafficking victims. It involved cyber surveillance, international weapons dealing (in the form of cyber weapons), and access to sensitive intelligence.

Second, it confirms that the cyber weapons market is real and consequential. Governments don't just develop cyber capabilities internally. They purchase exploits and capabilities from outside sources, sometimes without fully understanding the supply chain. This creates risks: intelligence agencies might be unwittingly funding criminal enterprises, and exploits might be obtained by actors outside the intended buyer.

Third, it raises uncomfortable questions about government oversight and accountability. Intelligence agencies purchase cyber weapons in secret, use them for purposes that aren't disclosed to the public, and maintain exploits unpatched, leaving civilians vulnerable. There's minimal oversight and virtually no public debate about whether this is acceptable.

Fourth, it highlights the vulnerability of modern infrastructure to cyber attacks. If Epstein's hacker could sell exploits to multiple governments, those exploits could have been stolen, leaked, or obtained by unauthorized parties. Critical infrastructure worldwide could be vulnerable to attacks using these tools.

Finally, it underscores that cybersecurity isn't just about better passwords and software updates. It's about understanding who has access to your systems, what exploits exist that could compromise them, and whether those who wield those exploits (governments, criminals, terrorists) have incentives to surveil you.

The FBI's release of this information in 2025 suggests that authorities have concluded their investigation or that the operational sensitivity of disclosing it has diminished. But critical questions remain unanswered: Who was the hacker? Has he been prosecuted? What happened to the zero-days he sold? Is he still operating?

Without answers to these questions, we're left with an incomplete picture of how sophisticated criminal enterprises operate in the modern era and how deeply they're connected to the intelligence agencies that are supposed to protect us.

The Epstein case is ultimately about power. The power to surveil without consent. The power to exploit vulnerabilities for profit or politics. The power to operate in secret without accountability. As cyber weapons become more powerful and more proliferated, understanding and controlling these power dynamics becomes more important to society's security and freedom.

The 2025 document release gives us a glimpse into this world. But the full picture—who these actors were, what they did, what consequences they faced—remains largely hidden from public view. Until that changes, the cyber weapons market will continue operating in shadows, enabling both governments and criminals to exploit our vulnerabilities with near-total impunity.

Key Takeaways

- FBI documents confirm Jeffrey Epstein employed a sophisticated hacker who developed and sold zero-day exploits to multiple governments, the U.K., and Hezbollah

- The hacker, allegedly an Italian national from Calabria, specialized in iOS, BlackBerry, and Firefox vulnerabilities—the most valuable targets in the cyber weapons market

- Hezbollah paid for zero-day exploits with physical cash, demonstrating how underground cyber weapons transactions avoid financial surveillance

- U.S. intelligence agencies were among the buyers of these exploits, raising questions about oversight and supply chain integrity in government cyber procurement

- The case reveals the billion-dollar underground market for cyber weapons operates globally and connects criminal enterprises, governments, and terrorist organizations

- Once deployed, zero-day exploits remain unpatched to maintain their tactical advantage, leaving millions of users vulnerable to surveillance using the same tools

Related Articles

- Best Cheap VPN 2026: Complete Guide & Alternatives

- Polish Power Grid Breach: How Russian Hackers Exploited Default Credentials [2025]

- North Korean Labyrinth Chollima Malware Splits Into Three Entities [2025]

- Bumble & Match Cyberattack: What Happened & How to Protect Your Data [2025]

- Device Protection Beyond Hardware: Securing Your Digital Identity [2025]

- Google's War on Residential Proxies: How IPIDEA's Network Collapsed [2025]

![Jeffrey Epstein's 'Personal Hacker': Zero-Day Exploits & Cyber Espionage [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/jeffrey-epstein-s-personal-hacker-zero-day-exploits-cyber-es/image-1-1769812793837.jpg)