How Meta Burned $19 Billion and Pivoted to Survive

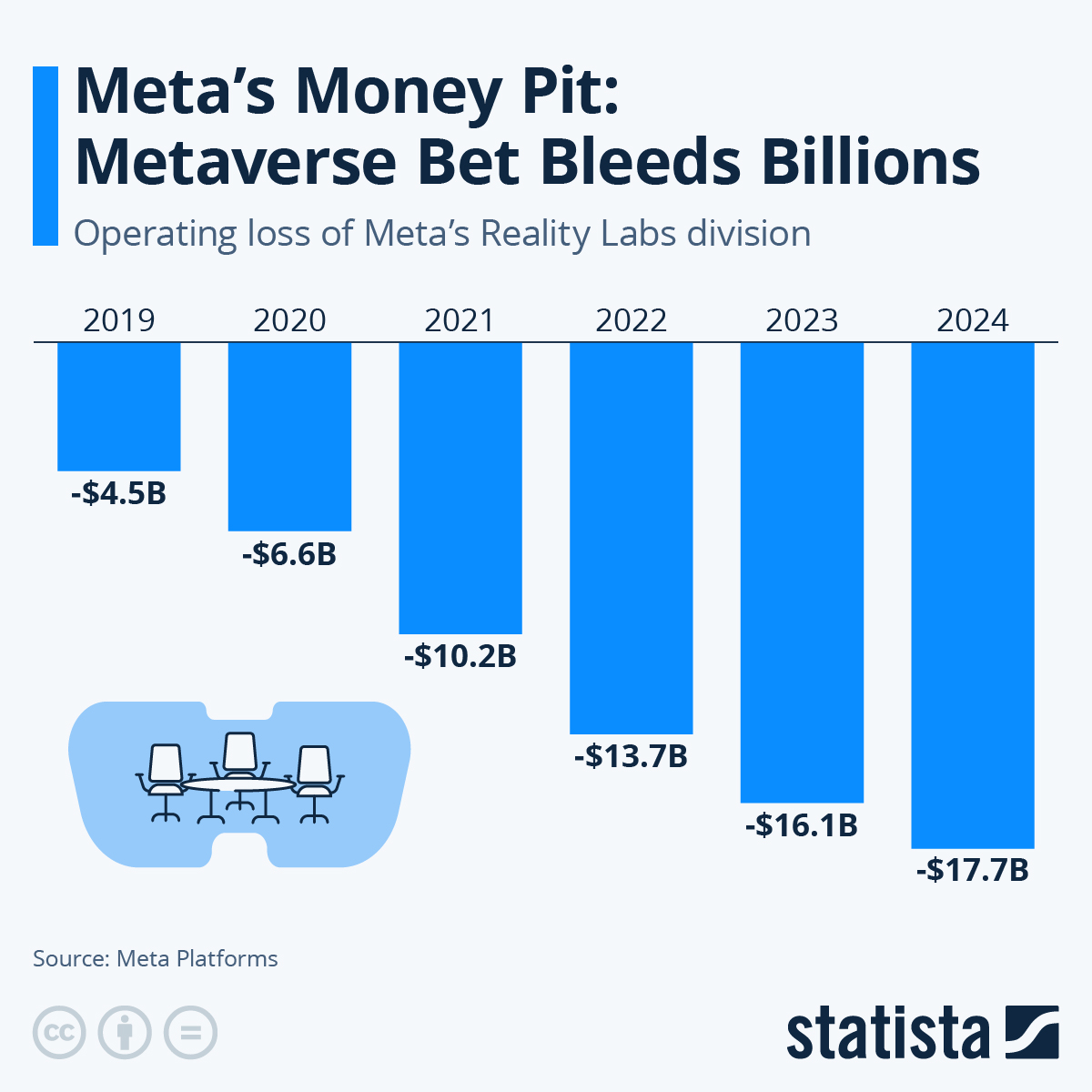

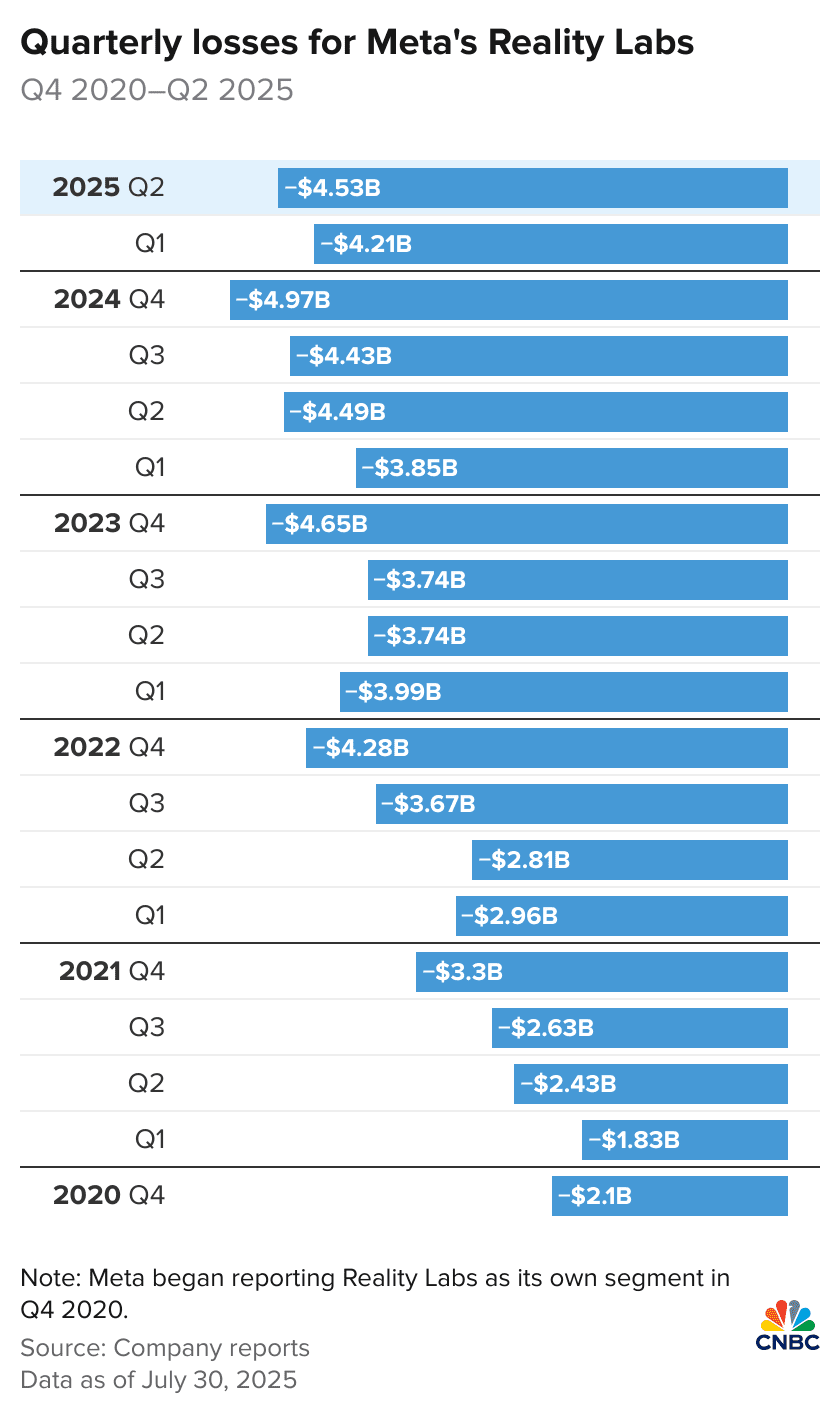

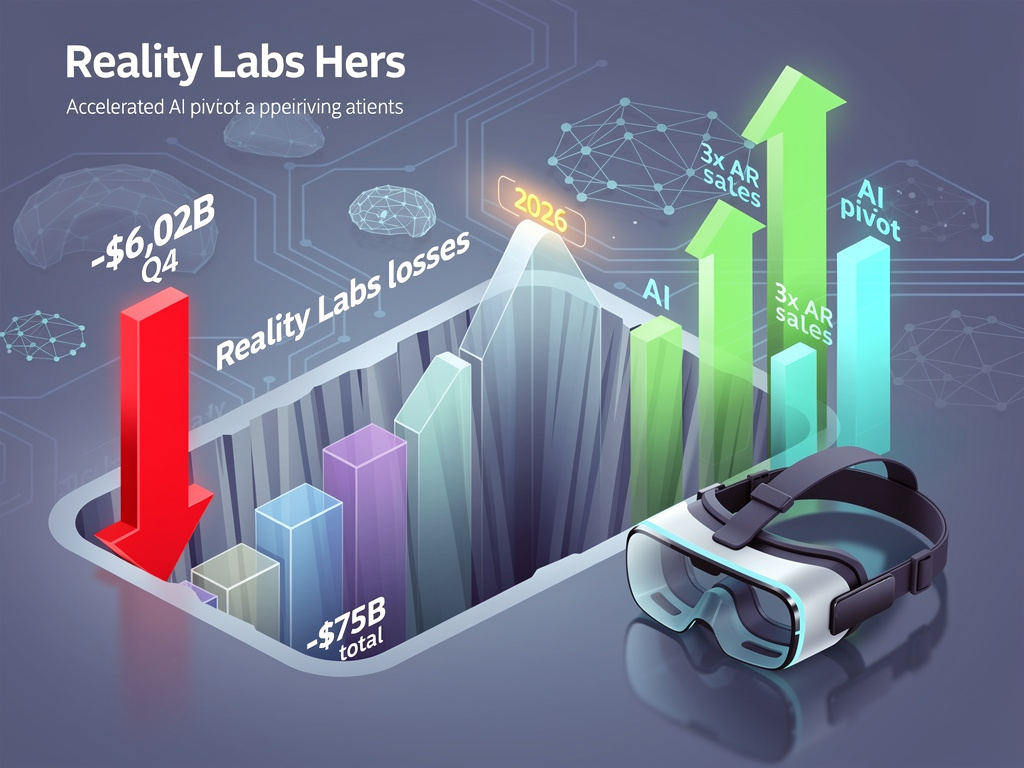

Last quarter, Meta's Reality Labs division lost more than $19 billion in a single year. Let that number sit for a moment. Nineteen billion dollars. That's roughly the GDP of El Salvador. It's more than Tesla's entire annual revenue. It's the kind of number that makes shareholders sweat.

Mark Zuckerberg walked into Meta's earnings call with a message that seemed designed to stop the bleeding: the losses are plateauing. More importantly, the company is shifting away from the metaverse dream that consumed that staggering amount of capital. Instead, Reality Labs is reorienting itself around artificial intelligence-powered glasses and wearables, hoping to find a path to profitability that doesn't require building an entire parallel digital universe.

This isn't just a tactical adjustment. It's a fundamental admission that the metaverse strategy, as originally envisioned, wasn't working. But it also represents something potentially more important: a realistic glimpse into what might actually become the next major computing platform.

We're going to walk through exactly what happened, why Meta is making these changes, what's actually working with their smart glasses division, and whether this pivot represents genuine progress or just a different way to lose large amounts of money. The stakes here are massive, not just for Meta's shareholders but for what the future of computing might actually look like.

TL; DR

- Reality Labs lost $19 billion in 2025 alone, making it one of the most expensive bets in tech history

- Meta is officially shifting focus away from VR and the metaverse toward AI-powered glasses and wearables

- Smart glasses sales tripled in 2025, suggesting consumer interest in AR might finally be materializing

- The company cut 1,000+ employees from Reality Labs and shut down three VR studios to right-size the division

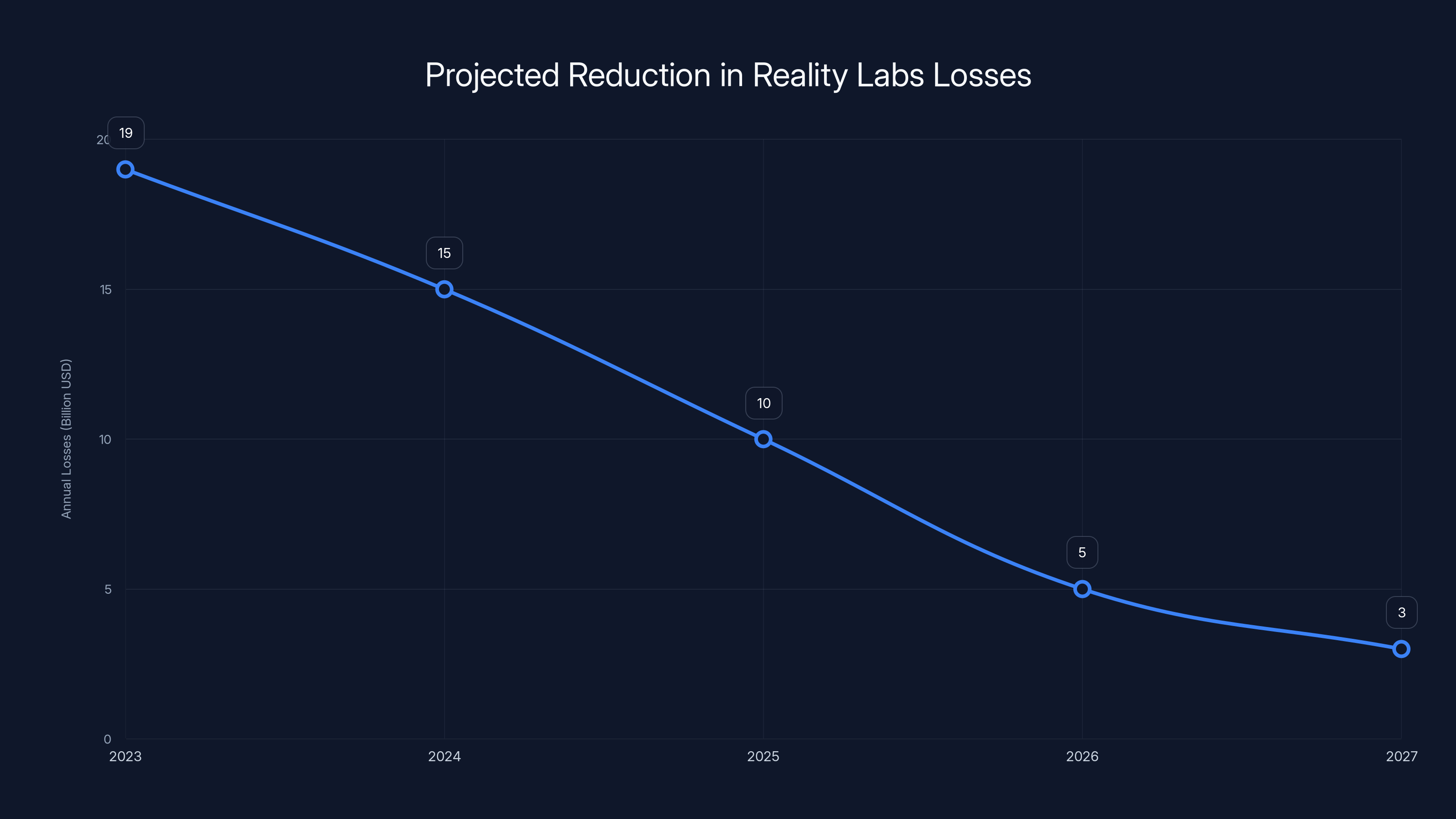

- Zuckerberg expects losses to peak in 2025, with gradual reductions starting in 2026 as the glasses business scales

Estimated data shows Reality Labs' annual losses could reduce from

The Reality Labs Financial Bloodbath: Understanding the Numbers

Reality Labs didn't start losing money yesterday. The division has been burning cash consistently for years, but the scale of losses accelerated dramatically as Meta doubled and tripled down on what it called the metaverse. When you're spending billions on R&D, manufacturing hardware, building software ecosystems, acquiring companies, and marketing virtual worlds that most people don't want to enter, financial losses become inevitable.

The nineteen billion dollar loss figure represents the most expensive bet on an unproven future that any major tech company has made in recent history. To put this in context, that's more than Apple spends annually on all research and development across every product line. It's roughly equivalent to what the entire U. S. film and television industry generates in a single year.

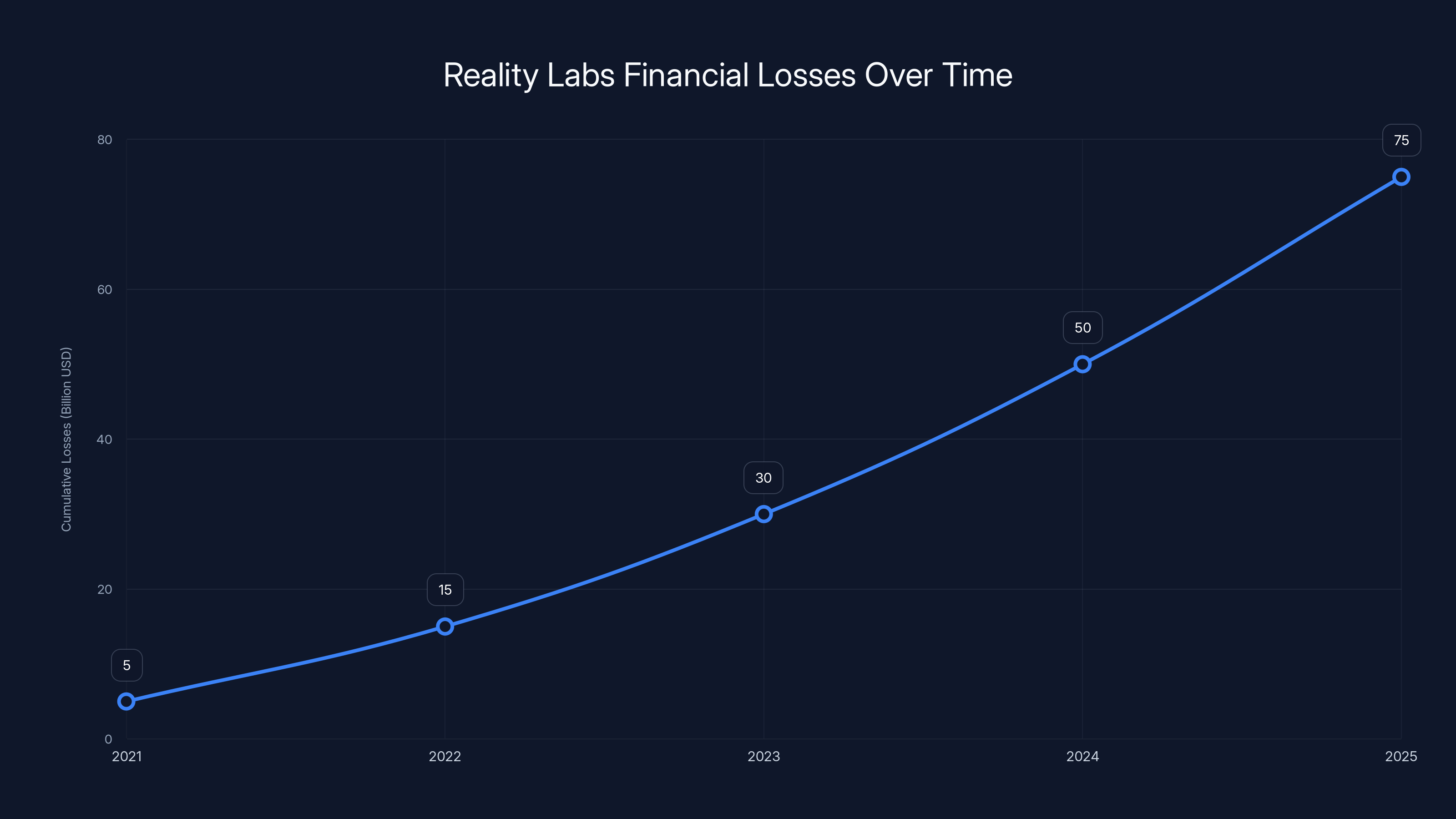

What makes this particularly striking is that these losses have been cumulative and consistently massive. Reality Labs didn't have one bad year. It's had multiple years where losses exceeded five billion dollars, building toward the 2025 total. The compound effect across multiple years means Meta has essentially written a check for somewhere in the neighborhood of seventy to eighty billion dollars total on virtual reality and metaverse infrastructure since Zuckerberg rebranded the company in October 2021.

For context, that's roughly what it cost to build the entire U. S. Interstate Highway System in inflation-adjusted dollars. That's the total annual revenue of many Fortune 500 companies. That's enough to fund cutting-edge research institutions, build space stations, or fundamentally transform global healthcare infrastructure.

Why the Losses Kept Growing

The losses grew for a straightforward reason: Meta kept investing more heavily in an area where adoption was flatlined. The company didn't pull back as consumer demand remained tepid. Instead, Zuckerberg and the board doubled down, convinced that patience would eventually pay off.

This strategy made a certain kind of sense on paper. Building entirely new computing platforms is expensive. The smartphone market took years to develop. The cloud computing ecosystem required massive upfront investment before generating meaningful returns. Patience, in theory, should be rewarded.

But there's a critical difference: smartphones and cloud infrastructure solved immediate, tangible problems that consumers and businesses already knew they had. The metaverse, by contrast, required first convincing people that they even wanted to spend hours in virtual reality social spaces. That proved to be a much harder sell than anticipated.

The VR headset market stagnated. Horizon Worlds, Meta's flagship metaverse platform, struggled to attract users. The open ecosystem of third-party Horizon OS headsets that Meta was developing found minimal commercial interest. Meanwhile, the hardware was expensive, uncomfortable for extended wear, and required constant refinement.

Meta kept investing anyway, acquiring talent, building infrastructure, and hoping that if they built it comprehensively enough, people would eventually come. They didn't, at least not at the scale required to justify the expenditure.

The Hidden Costs Beyond Hardware

When people think about why Reality Labs burned through billions, they often focus on hardware development. Creating a new device category is expensive. Manufacturing, iteration, tooling, supply chain management—these all require significant capital.

But the real money went to something more expansive: building an entire ecosystem from the ground up. This included acquiring multiple companies in the AR and VR space, developing proprietary operating systems, building content creation tools, funding game development studios, creating spatial computing platforms, and marketing these products into a market that had limited demand.

Meta essentially tried to do what the smartphone industry does organically across hundreds of companies and multiple decades, but do it in-house and in less than a decade. That approach works for certain things. It doesn't work for building cultural momentum around a new platform when the market isn't ready.

The acquisition strategy alone was staggering. Meta paid two billion dollars for Beat Saber, a popular VR rhythm game. It acquired companies like Surreal Vision, Downpour Systems, and numerous others at premium prices. Each acquisition required integration, ongoing development, and coordination with existing teams. That's all overhead that contributes to losses without directly generating revenue.

Estimated data shows Reality Labs' cumulative financial losses growing from

The Metaverse Moment That Never Came

In October 2021, Mark Zuckerberg announced that Meta was rebranding from Facebook. The new name represented the company's strategic pivot toward what he called the metaverse. He published a lengthy manifesto about spatial computing, persistent virtual worlds, and how the metaverse represented the successor to the mobile internet.

The timing seemed almost calculated to maximize investor disappointment. Meta announced this massive strategic shift just as Apple released the first results of a major App Tracking Transparency update that would devastate Meta's advertising targeting capabilities and revenue growth. The market didn't react well.

But within Meta's leadership, conviction was high. Zuckerberg genuinely believed that the metaverse was coming, that spatial computing would eventually become the primary way humans interact with information and each other, and that the company that owned the platform would have enormous power and opportunity.

He wasn't entirely wrong about the premise. Spatial computing is genuinely interesting. The technology is improving rapidly. There are legitimate use cases for immersive virtual environments. But there's a massive gap between "this technology is interesting and will eventually matter" and "we should invest eighty billion dollars immediately in hopes of creating consumer-scale adoption."

The metaverse as Zuckerberg envisioned it—millions of people regularly hanging out in interconnected virtual worlds, conducting business, socializing, and building identity—simply hasn't materialized. The reasons are numerous: VR headsets remain expensive and uncomfortable, content is limited, the technology is still early, consumer interest hasn't developed, and perhaps most fundamentally, there isn't a killer app that makes people think virtual reality social spaces are better than real human interaction.

The 2025 Reckoning: When Losses Peak

At the earnings call, Zuckerberg made a specific prediction: 2025 would likely represent the peak of Reality Labs' losses. After that, the company would "gradually reduce" annual losses as it shifted its strategic focus.

This statement is crucial because it represents an implicit acknowledgment of reality. The metaverse bet didn't work at the scale and speed originally anticipated. Continuing down that path would be irrational. So the company is fundamentally restructuring how it approaches the space.

Part of this restructuring is defensive. Reality Labs is no longer trying to build a complete ecosystem. The company shut down three VR studios, paused plans for third-party Horizon OS headsets, and retired its app for VR meetings. These weren't trivial decisions. They represented years of work and significant sunk costs being abandoned.

But part of this restructuring is also genuinely strategic. Meta identified something that actually is working: smart glasses that can overlay digital information onto the real world. This is fundamentally different from the VR approach. Instead of replacing reality with a virtual alternative, AR-enabled glasses enhance reality by adding digital information to it.

This matters because AR solving a different problem than VR. Virtual reality asks: "Why would you want to leave reality?" Augmented reality asks: "How can digital information make your existing reality more useful?" The second question is much easier to answer. It's more intuitive to most people. And it doesn't require creating entirely new virtual worlds.

The Cost of Course Correction

Shifting a company's strategic direction isn't free. Meta announced layoffs of more than one thousand employees from the Reality Labs division. These were skilled engineers, designers, and product managers who'd been hired specifically to build the metaverse vision.

Layoffs hurt people. They hurt the people being laid off immediately. They hurt remaining teams through disruption and uncertainty. They hurt the company's culture. But from a financial perspective, right-sizing an organization that was overinvested in a strategy that wasn't working is necessary.

The reality is that Reality Labs was bloated relative to what it was actually accomplishing. The team was large enough to build multiple VR operating systems, fund numerous content studios, develop cutting-edge hardware, and maintain a sprawling ecosystem. That's an enormous organization focused on a product that most people don't want.

A smaller, more focused team can build smart glasses. That's a more tractable problem. It requires less infrastructure. It doesn't require building entire content ecosystems from scratch. It plays more directly to Meta's existing strengths in software, mobile integration, and understanding user behavior.

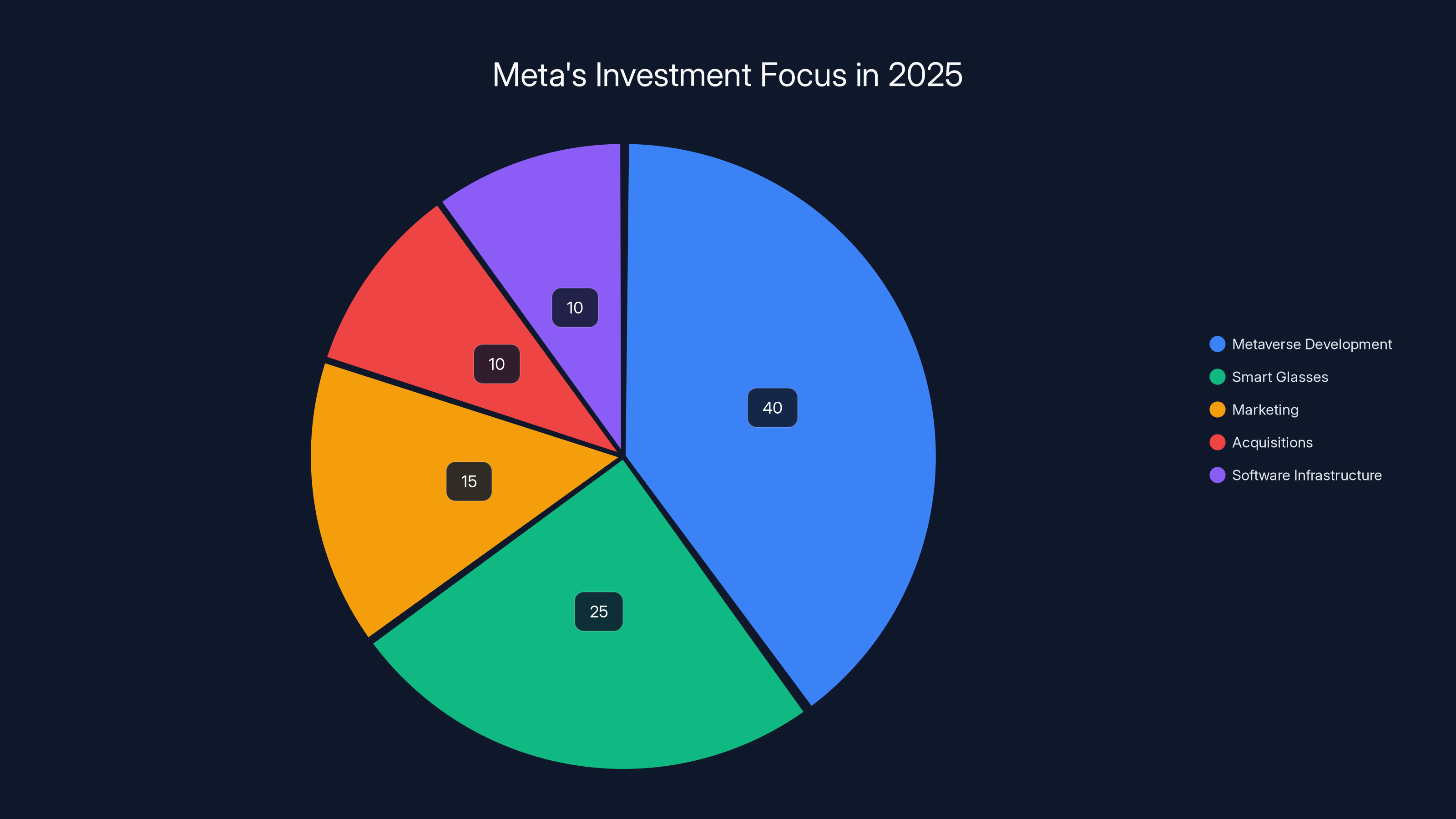

Estimated data shows Meta's significant investment in metaverse development, overshadowing other areas like smart glasses and marketing.

Smart Glasses: The Division That's Actually Working

While the metaverse burned billions with minimal consumer adoption, Meta's smart glasses division did something remarkable: it showed actual growth. Sales of Meta's smart glasses more than tripled in 2025.

This matters because it's real evidence of consumer demand. People are actually buying these things. Not in the billions of units, but in meaningful volumes. And the trajectory is positive, moving in the opposite direction from metaverse adoption.

Meta's smart glasses represent something genuinely useful. They're camera-equipped glasses that can record video from the user's perspective, provide notifications and information overlays, and eventually could include more sophisticated AR capabilities. They're the kind of thing that could become an everyday accessory, like airpods or smartwatches.

The current generation of Meta smart glasses does something straightforward: it captures the user's perspective with a built-in camera. This alone has use cases. Users can record moments hands-free. They can livestream their point of view. Eventually, the glasses could use the front-facing and side-facing cameras to understand what they're looking at and provide relevant information.

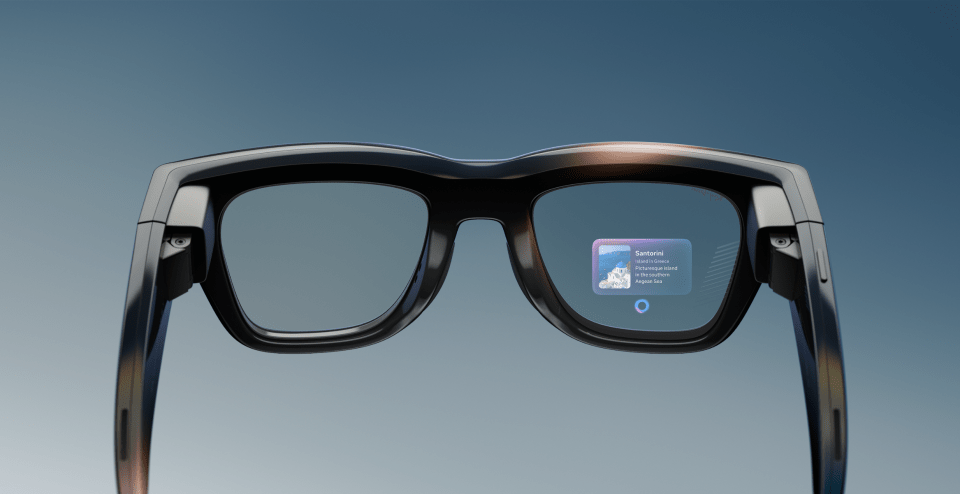

Zuckerberg described the long-term vision during the earnings call: glasses that can see what you see, hear what you hear, and provide helpful information or generate custom UI right in your field of vision. That's essentially a lightweight augmented reality computer for everyday use.

Why Smart Glasses Beat VR Headsets

Smart glasses have several fundamental advantages over the VR headsets that were consuming Reality Labs' budget:

First, they're lightweight and practical. You can wear smart glasses all day without getting neck strain or fatigue. VR headsets are heavy, uncomfortable for extended wear, and isolate you from your actual surroundings. That makes them suitable for entertainment but not for daily use.

Second, they enhance rather than replace. Smart glasses keep you aware of your actual environment while adding digital information. VR headsets completely replace your reality with a virtual one. Most people, most of the time, prefer to stay connected to reality.

Third, they're socially acceptable. Wearing glasses in public looks normal. People wear glasses, sunglasses, and smart eyewear constantly. Strapping a VR headset to your face in a coffee shop makes you look ridiculous. Consumer acceptance matters, and glasses have built-in social legitimacy.

Fourth, they integrate with existing behavior. People already wear glasses or sunglasses. Smart glasses can replace sunglasses. They fit into existing behavior patterns. VR headsets require entirely new contexts and behaviors.

Fifth, they're cheaper to manufacture and iterate. Smart glasses can leverage existing manufacturing infrastructure. The compute requirements are lower than VR headsets. They can be built in smaller, more efficient form factors. This means faster iteration and lower costs.

The AR Opportunity That VR Missed

The broader opportunity here is that augmented reality might finally be reaching an inflection point where it becomes practical. For years, AR was "the technology of the future that's always five years away." The hardware didn't exist. The software ecosystem wasn't developed. It wasn't clear what problems AR actually solved better than existing solutions.

But over the last few years, multiple factors have converged. Processors have gotten more efficient. Battery technology has improved. Camera and sensor technology has advanced dramatically. Computer vision algorithms have become far more capable. And most importantly, there are now clear use cases that people actually want to use.

Think about smartphone navigation. Before GPS-enabled phones with maps applications, getting directions was genuinely painful. You'd print out directions or ask for help. Once smartphones solved navigation as a core feature, it became essential to the platform. AR in glasses could play a similar role: providing contextual information and guidance without requiring you to look away from your environment.

Imagine being in an unfamiliar city. AR glasses could highlight points of interest, show you restaurant reviews floating above storefronts, provide real-time language translation, or guide you to your destination without you needing to stare at a phone. Imagine being a technician working on equipment and having access to diagrams and troubleshooting information overlaid on the actual device. Imagine being in a meeting and having relevant information about the person you're talking to displayed in your field of vision.

These are compelling use cases. They don't require a metaverse. They don't require anyone to believe in virtual reality social spaces. They just require glasses that can provide useful information in a hands-free, always-available way.

The AI Integration: Where AR Actually Gets Interesting

Here's where Meta's pivot becomes more sophisticated than just "VR didn't work, so let's try AR instead." The company is integrating artificial intelligence capabilities into smart glasses, and that's where the real potential emerges.

Zuckerberg mentioned during the earnings call that future AR glasses would "help you as you go about your day" using AI. This isn't just overlaying information. This is glasses that actively understand your context and provide intelligent assistance.

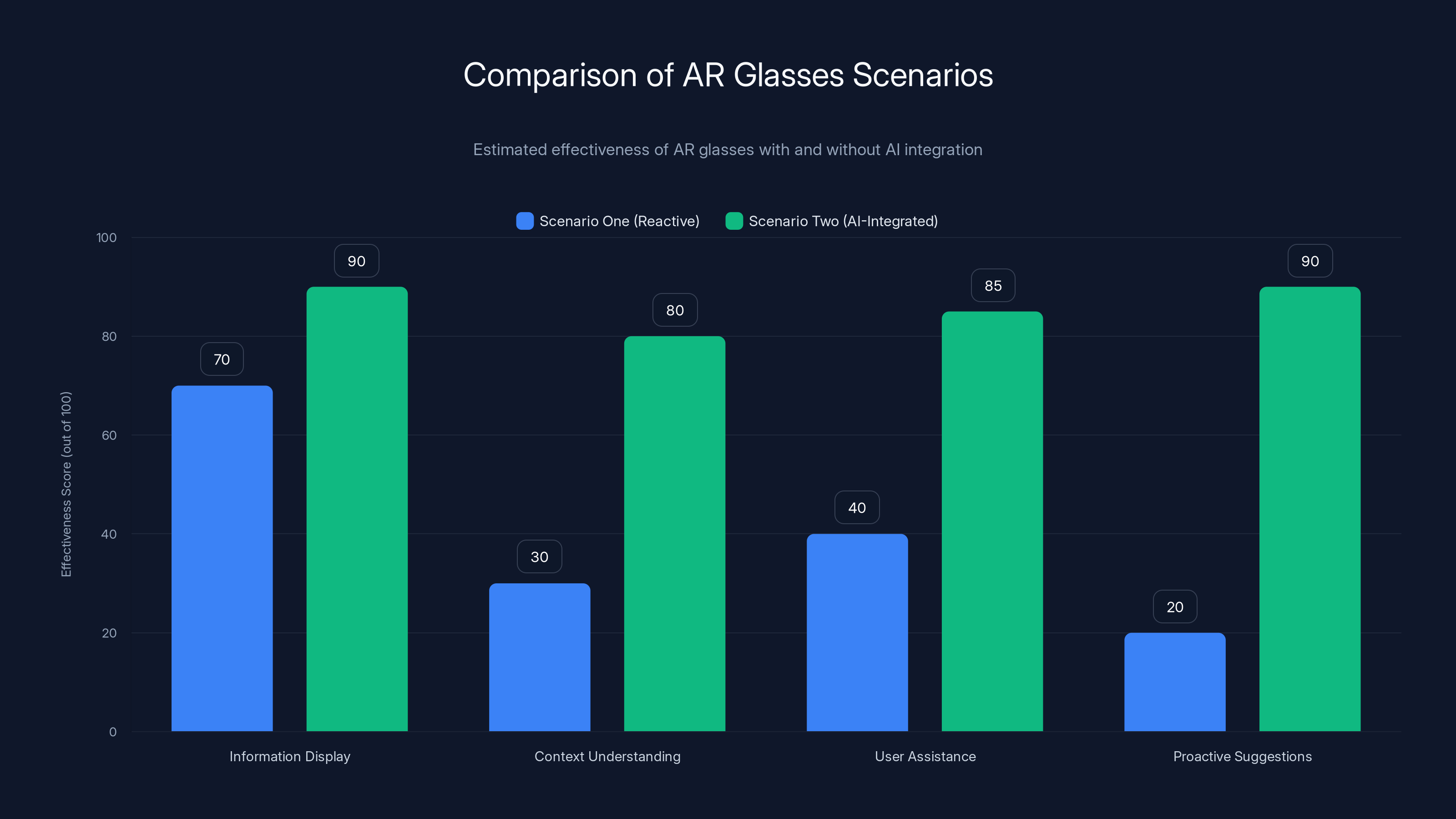

Consider the difference between two scenarios:

Scenario One: Your AR glasses display information you explicitly search for. You see a restaurant, you ask for reviews, the glasses show ratings. You're at a store, you ask for prices, the glasses show comparisons. This is useful but still reactive. You have to know what information you want.

Scenario Two: Your AR glasses understand your context, your goals, and your history. You're looking for coffee. The glasses recognize that you like single-origin pour-over, that you prefer shops with outdoor seating, and that you've been meaning to try a new place in the neighborhood. Without you asking for anything, the glasses highlight three nearby options that match your preferences, show you current wait times, and suggest the best one based on your preferences.

The second scenario is what AI integration enables. The glasses become an intelligent assistant that actively helps you navigate and understand the world around you, not just a passive information display.

This is also where Meta's existing capabilities become relevant. Meta has spent years building recommendation algorithms, understanding user preferences, and predicting what information users find valuable. That expertise, applied to AR glasses with AI assistance, becomes genuinely powerful.

The Infrastructure Investment Pays Off

This is important: the infrastructure investment Meta made during the Reality Labs metaverse years isn't entirely wasted. The company built:

- Advanced research teams working on spatial computing, computer vision, and hardware design

- Manufacturing relationships and supply chains for specialized electronics

- Software platforms for building immersive experiences

- Expertise in power management and display technology for AR

- Talent in areas like eye tracking, gesture recognition, and spatial audio

All of this translates to smart glasses and AI-integrated wearables. The company doesn't have to start from scratch. It has a sophisticated technical foundation, even if the specific products that foundation was built for are being abandoned.

Meta is essentially saying: "We over-invested in the metaverse idea, but the underlying technology research was valuable. Let's apply that research to products that actually solve problems people care about."

That's a more realistic assessment than simply accepting the losses as sunk costs and moving on completely.

AI integration significantly enhances AR glasses' effectiveness by enabling proactive and context-aware assistance. Estimated data.

Why the Metaverse Failed: The Fundamental Problem

Before moving forward, it's worth understanding why the metaverse didn't work. This isn't just relevant to Meta's specific bet. It's relevant to understanding how technology adoption actually works.

The metaverse was predicated on a specific assumption: that virtual reality social spaces would eventually become preferable to physical reality for human interaction and experience. That assumption was wrong, or at least far more wrong than Meta anticipated.

There are several reasons why this assumption failed:

First, humans are not primarily visual creatures. We often think of VR as immersive because it fills your entire visual field. But human experience is multisensory. We feel physical presence through touch and proprioception. We taste and smell. We feel temperature, air movement, and spatial orientation in ways that aren't replicated in virtual spaces. Virtual reality addresses sight and sound primarily. It's incomplete.

Second, physical presence has powerful psychological benefits that VR doesn't replicate. Being in the same physical space as someone activates different parts of the brain and creates different kinds of connection. There's something about physical co-presence that virtual proximity doesn't capture, even with sophisticated VR. Humans seem to deeply prefer physical interaction for close relationships.

Third, virtual worlds require constant content creation and maintenance. Physical reality doesn't require anyone to design and build it. It just exists. Virtual worlds, by contrast, require someone to create every element, maintain servers, prevent harassment and abuse, moderate content, and constantly refresh things so they don't become boring. That's expensive and hard.

Fourth, there was no killer app. Smartphones had a killer app: wireless communication and on-demand information access. The internet had email and the web. Cloud computing had elasticity and cost savings. The metaverse didn't have a clear, compelling reason that people must use it instead of other options. People didn't wake up desperate to spend time in virtual reality.

Fifth, the network effects didn't work the way Meta predicted. Network effects matter for platforms: the value increases as more people join. But network effects require the platform to solve a problem that people actually have. If the problem isn't real, network effects become irrelevant. You can't force millions of people to join a virtual world if they don't want to be there.

The Broader Lesson About Emerging Technology

Meta's metaverse loss is instructive for thinking about emerging technology generally. Companies often over-invest in platforms they believe will matter, even when consumer demand isn't materializing. This happens because:

- Sunk cost bias makes it hard to redirect resources

- Conviction in the vision can exceed evidence from the market

- Long-term thinking sometimes becomes disconnected from actual demand signals

- Competitive fears drive investment even when ROI is questionable

Meta believed, genuinely, that the metaverse was inevitable. So investing billions to ensure the company had a leading position made sense from a strategic perspective. But inevitability and actual consumer desire are different things.

The takeaway: when evaluating technology investments, watch for the gap between what's technically possible and what people actually want to do. Metaverse VR was technically impressive. It was genuinely innovative. But almost nobody wanted to spend significant time in it. That gap is where the billions got lost.

The Strategic Pivot: Focusing on Wearables and AI

Meta's new strategic direction for Reality Labs can be summarized as: "Stop trying to replace reality, and focus on enhancing it."

This is a meaningful shift. Instead of trying to build an entire alternative universe with its own content ecosystem, business models, and social networks, the company is building tools that integrate with reality and leverage AI to provide practical value.

The wearables focus makes sense from multiple angles:

It plays to Meta's strengths. The company understands mobile devices, sensors, connectivity, and AI integration. Wearables require all of those capabilities. VR required building entirely new platforms from scratch.

It addresses actual pain points. Smartphones are ubiquitous, but they require you to look at a screen. That's inconvenient in many situations. Wearables that provide information without requiring your visual attention solve a real problem.

It's a larger market opportunity. The potential market for smart glasses and wearables is vastly larger than the market for VR headsets. Billions of people wear glasses, watches, or other wearables. Potentially all of them could upgrade to smart versions. The market for VR headsets is orders of magnitude smaller.

It's harder for competitors to copy. Apple, Google, and other major tech companies all could theoretically build VR headsets. But Meta has years of hardware experience and relationships with manufacturers. Building competitive smart glasses is also hard, but it's harder for completely new competitors to enter than it would be in VR.

It's a clearer path to profitability. Smart glasses can be sold at healthy margins, especially if they integrate with existing Meta platforms like Whats App and Messenger. VR headsets face margin pressure from competitors and limited price elasticity in a niche market.

Making Horizon Mobile a Success

One specific focus of the new strategy is making Horizon a "massive success on mobile." This is interesting because it represents an acknowledgment that Horizon, Meta's metaverse platform, isn't going away entirely. But it's being repositioned.

Instead of a standalone VR platform that requires expensive hardware, Horizon is becoming a mobile application. That's a massive difference in addressability. Mobile has billions of users. VR has millions. Mobile development is a solved problem with massive ecosystems. VR still has major challenges.

This suggests Meta might try to make Horizon work as a mobile game or social app first, prove the concept at scale, and then potentially extend it to AR glasses if there's genuine demand. That's a more sensible progression than trying to prove the metaverse via expensive hardware to a niche audience.

Profitable VR Ecosystem

Meta also mentioned making VR "a profitable ecosystem over the coming years." This isn't about abandoning VR entirely. It's about right-sizing the VR business to be sustainable without requiring massive losses.

VR will likely continue to exist and improve. Gaming companies will continue developing VR experiences. Some percentage of consumers will continue adopting VR headsets. But Meta is deprioritizing VR hardware development and instead focusing on being one player in a diverse VR ecosystem, rather than trying to control the entire category.

This is more realistic. It acknowledges that VR has genuine value for gaming, entertainment, and specific enterprise use cases. But it's not the transformative consumer platform Meta hoped it would become, at least not on the timeline the company originally imagined.

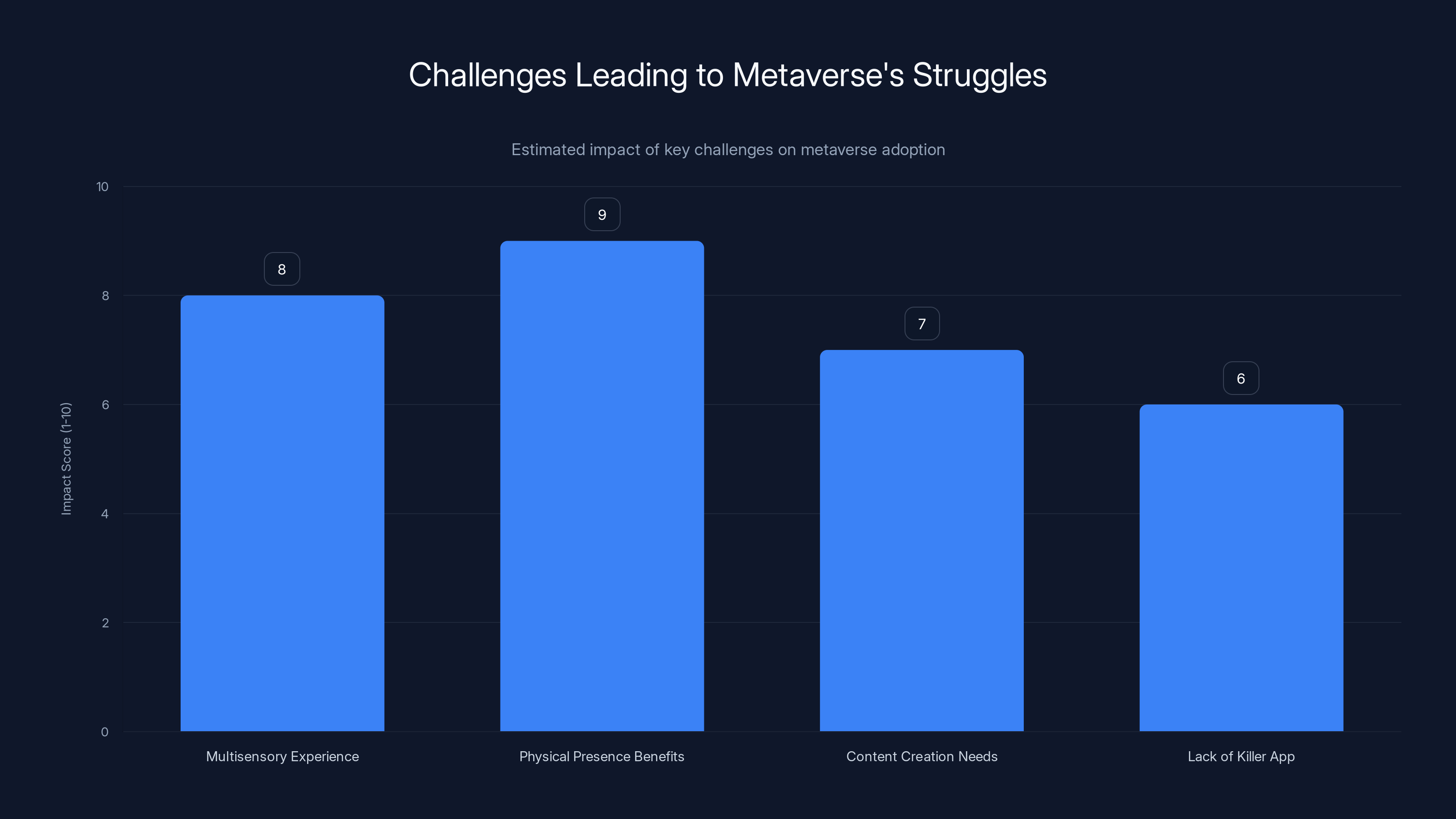

The metaverse faced significant challenges, with physical presence benefits and multisensory experience gaps being the most impactful. (Estimated data)

The Financial Path to Profitability

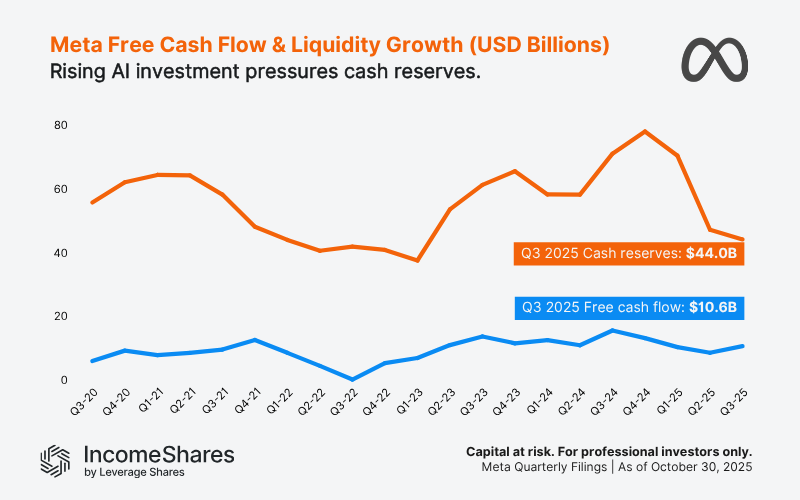

Zuckerberg explicitly stated that 2025 would likely represent the peak of Reality Labs losses, with gradual reductions going forward. This is an important projection because it impacts Meta's overall financial health and shareholder sentiment.

If accurate, it means the company expects to reduce annual losses from nineteen billion dollars toward something more manageable. Even getting losses down to five billion dollars annually would represent a seventy percent reduction. Getting to two or three billion dollars would be eighty to ninety percent.

How would this happen?

First, through headcount reduction. The thousand-plus layoffs already announced reduce ongoing salary, benefits, and operational costs.

Second, through reduced R&D spending. No longer funding three VR studios, multiple hardware projects, and ecosystem development means less daily burn rate.

Third, through revenue from smart glasses. If sales continue tripling year-over-year, even at current price points, revenue can grow substantially.

Fourth, through margin improvement as manufacturing scales. Early hardware production has high per-unit costs. As production scales and processes mature, costs decrease, and margins improve.

Fifth, through successful AI integration. If AI-powered glasses become genuinely useful, they could command premium pricing and drive higher unit volumes.

The Timeline to Actual Profitability

Getting to profitability is different from reducing losses. Zuckerberg didn't promise profitability. He promised that losses would "gradually reduce." That's a crucial distinction.

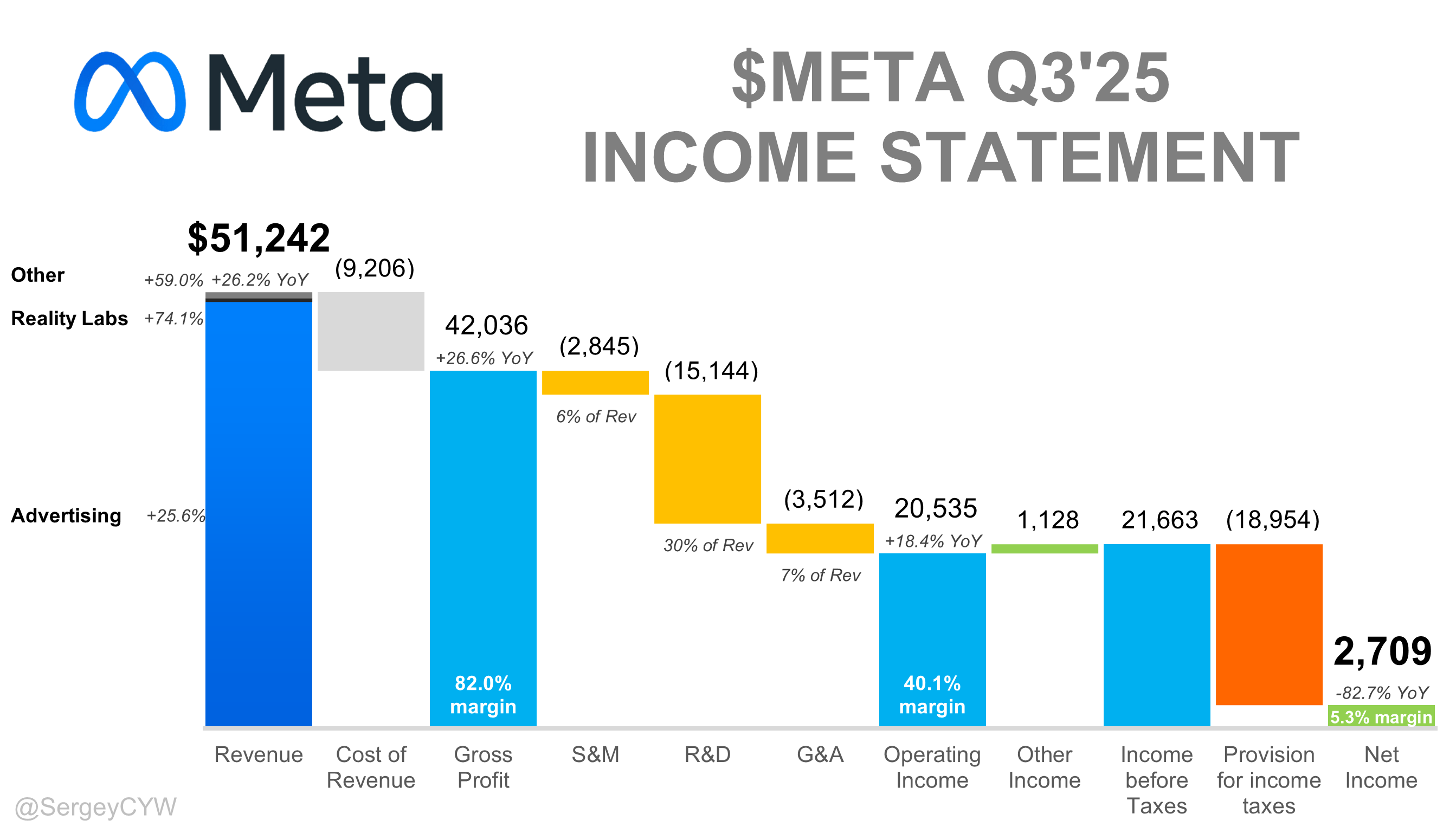

Reality Labs could reduce losses to three or four billion dollars annually and still not be profitable. But from Meta's broader business perspective, that might be acceptable. The company makes about twenty-five billion dollars in annual operating profit from its core advertising business. A loss of four billion from Reality Labs would reduce overall company profitability but wouldn't be devastating.

The path to actual Reality Labs profitability likely requires:

- Smart glasses to become a mass-market product (tens of millions of units annually)

- Gross margins of at least 30-40% on hardware

- Software and services revenue beyond hardware sales

- Enterprise adoption for professional use cases

- Continued cost reduction from manufacturing and R&D efficiency

That's achievable, but it requires execution across multiple dimensions. It's not guaranteed.

What Meta's Smart Glasses Can Actually Do

To understand why Meta is optimistic about the smart glasses business, it's worth understanding what current and near-future smart glasses can actually accomplish.

Current generation smart glasses: Meta's current smart glasses product is primarily a camera device. It can record video from the user's point of view, overlay frames that integrate with Meta's social platforms, and provide a hands-free recording device for content creation.

This might sound limited, but it's actually useful. Content creators like the hands-free recording. People like being able to share their perspective. The glasses integrate with Meta's platforms, making it natural to share to Instagram or Whats App. For certain use cases, this is genuinely valuable.

Next-generation capabilities: Zuckerberg described the vision for future AR glasses: "They're going to be able to see what you see, hear what you hear, talk to you and help you as you go about your day and even show you information or generate custom UI right there in your vision."

This describes glasses with:

- Full-color display capable of showing detailed UI

- Built-in microphones and speakers for interaction

- Robust computer vision to understand the environment

- AI processing to generate helpful responses

- Integration with Meta's AI and software infrastructure

A device like this could:

-

Provide real-time information overlays. You look at a building, the glasses identify it and show you information. You look at a plant, they identify the species and provide care tips. You look at a person's face in a business meeting and their Linked In profile appears in your field of vision.

-

Enable hands-free communication. You could receive messages, calls, and notifications in AR. You could respond through voice. You could video chat with the glasses handling the camera and display.

-

Assist with navigation and wayfinding. The glasses could guide you through unfamiliar spaces, highlight points of interest, and provide context about your surroundings.

-

Support professional workflows. Engineers could see technical documentation overlaid on equipment. Surgeons could see imaging data during procedures. Technicians could access repair guides hands-free.

-

Enable new forms of social interaction. Shared AR experiences between multiple users. Collaborative visualization of digital content in physical space.

The Challenge of Delivering These Capabilities

Describing what smart glasses could do is much easier than actually building it. Several technical challenges remain:

Display technology: Current AR displays are limited in brightness, field of view, color accuracy, and power consumption. Making displays that work in bright sunlight while consuming minimal power is genuinely hard.

Compute power: Running computer vision, AI inference, and application logic while staying within power and thermal constraints is challenging. You can't use standard laptop processors in glasses without creating a device that gets uncomfortably hot and drains batteries in hours.

Battery life: Current smart glasses might last a day or two on a charge. Making them last multiple days while adding more powerful compute is difficult.

Eye tracking: Knowing where the user is looking is useful for interaction and for understanding attention. But eye tracking adds complexity, power consumption, and calibration challenges.

Privacy and safety: Glasses that can see what you see and send that information somewhere raise significant privacy concerns. People need to trust the device. There are also physical safety concerns around driver attention and accident risk.

Content ecosystem: Even with perfect hardware, you need applications and experiences that justify wearing the glasses. Building that ecosystem requires developer support, which requires a clear business model and enough users to justify investment.

These aren't insurmountable challenges, but they're real. Meta has the resources to solve them, but it will take time and continued investment.

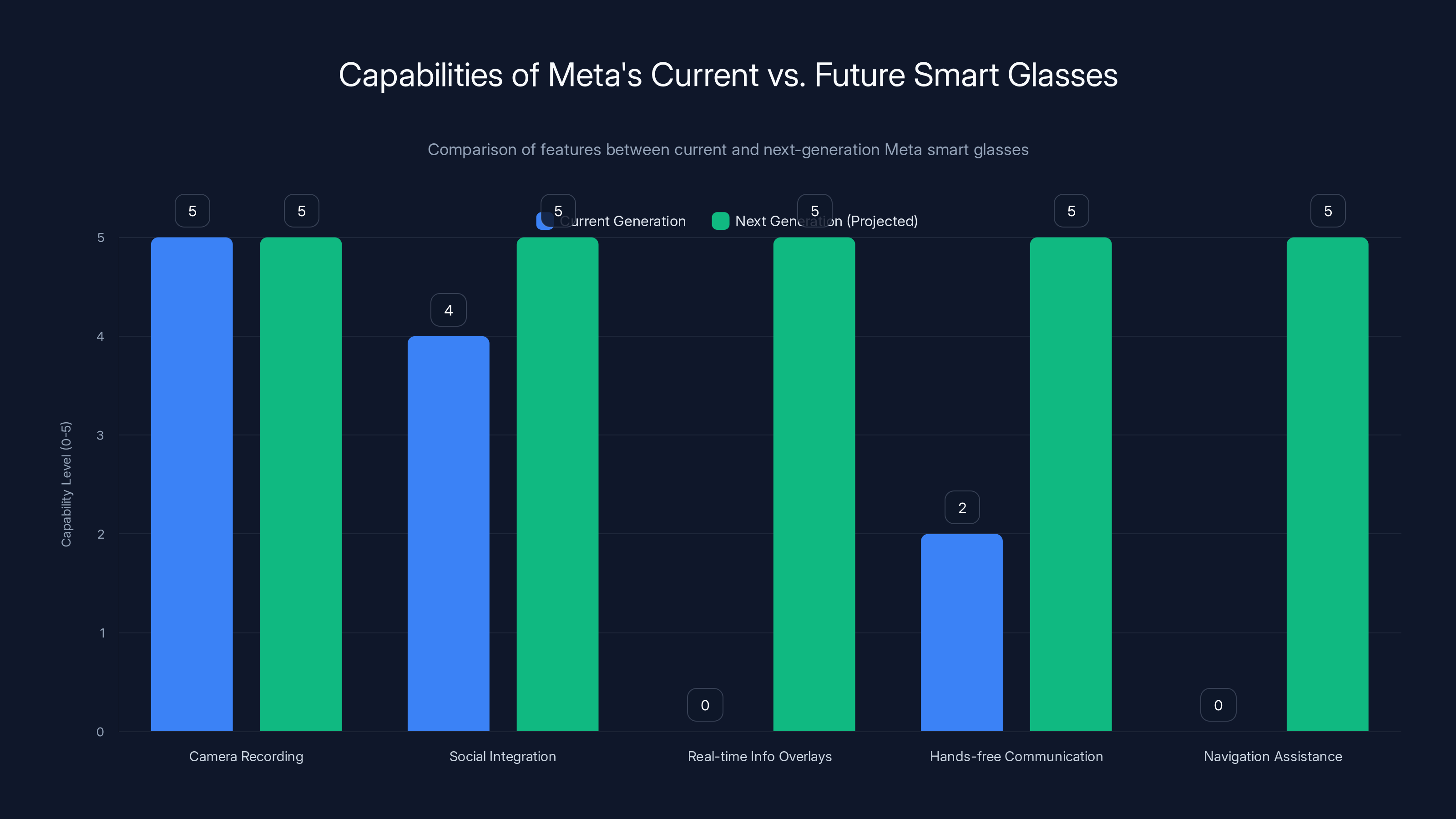

Current Meta smart glasses excel in camera recording and social integration, while future models are projected to offer comprehensive AR capabilities. Estimated data for future features.

The Competitive Landscape: Who Else Is Building Smart Glasses

Meta isn't alone in pursuing smart glasses. Several major tech companies and startups are working on similar products, which makes the competitive environment more complex.

Apple's approach: Apple hasn't released a consumer smart glasses product yet, but the company has been clear about its interest in spatial computing. The Vision Pro is an expensive, high-end device designed for computing and entertainment rather than everyday wear. But the company is researching lighter AR glasses for future release. If Apple launches consumer AR glasses, they could become the default device, given Apple's market position and brand loyalty.

Google's efforts: Google abandoned its Google Glass project years ago but has been investing in AR research and chip development. The company has the AI capabilities, the search and mapping data, and the software platforms that could make AR glasses compelling. Google might approach the market differently than Meta, focusing on practical information delivery rather than social connection.

Snap's position: Snap has been selling Spectacles, camera-equipped glasses focused on social sharing. The company has been iterating on the design and adding functionality. Snap has a younger user base predisposed to adopting new wearables, which could give them an advantage in scaling adoption.

Startup activity: Numerous startups are building specialized AR glasses for enterprise use cases. Companies are developing glasses for medical professionals, technical workers, warehouse employees, and other vertical markets.

The competitive dynamic matters because it affects Meta's strategy. If Apple launches compelling AR glasses, Meta's hardware might become secondary to a better-designed or more culturally desirable device. That would shift Meta's opportunity from selling hardware to selling services and software that run on competitors' devices.

This is actually not necessarily bad for Meta. The company makes money primarily from software, services, and advertising, not hardware. If Meta can integrate its services into popular glasses regardless of the hardware manufacturer, it wins. But it requires a shift in thinking away from the "our device, our platform" approach that dominated the Reality Labs metaverse strategy.

The Role of AI Agents in Smart Glasses

One of the most interesting aspects of Meta's pivot is the integration of AI agents into smart glasses. This is more sophisticated than simply adding AI assistance. It means the glasses themselves are running agent-like systems that can understand context, make decisions, and take actions.

Consider what an AI agent in smart glasses might do:

-

Contextual awareness: The agent understands what you're looking at, what you're doing, your location, the time of day, and your personal preferences and history.

-

Proactive assistance: Rather than waiting for you to ask a question, the agent suggests helpful actions or information based on your context.

-

Integration with services: The agent can interact with Meta's services (messaging, maps, search) and eventually third-party services to accomplish tasks.

-

Learning and personalization: The agent learns from your patterns of behavior and becomes more helpful over time.

This is different from a simple voice assistant like Alexa or Siri. Those systems respond to explicit queries. An AI agent in AR glasses operates continuously, understands your environment visually, and can suggest actions based on situation understanding.

Meta's expertise in recommendation algorithms and user behavior prediction becomes valuable here. The company has spent years figuring out what content individual users find compelling. That same expertise, applied to real-time context, could make AI agents in smart glasses genuinely useful.

The Privacy Implications of Always-On AI

Smart glasses with AI agents create significant privacy considerations. If the glasses are continuously analyzing your environment and your attention, that data needs to be handled carefully.

Meta will need to provide clear privacy controls, transparent data handling, and probably on-device processing to keep users comfortable. The company learned from public backlash against Facebook's data practices that privacy concerns can significantly limit adoption of new platforms.

If Meta executes this poorly, it could undermine adoption of smart glasses. If the company handles privacy thoughtfully, it becomes a competitive advantage.

How the Metaverse Years Changed Meta as a Company

Even though the metaverse bet didn't deliver financial returns, the investment changed Meta in important ways.

First, it forced investment in hardware expertise. Meta went from a pure software company to a company that manufactures hardware, manages supply chains, and understands the complexities of physical products. That expertise transfers to smart glasses.

Second, it built spatial computing research capabilities. The computer vision, augmented reality, and spatial audio research that was pursued for metaverse applications translates directly to smart glasses development.

Third, it attracted and retained specialized talent. The company hired researchers and engineers interested in spatial computing, wearables, and immersive technology. Those people are now focused on smart glasses instead of the metaverse, but they're still there building advanced technology.

Fourth, it shifted the company's long-term thinking. Meta now sees itself as not just an advertising and social platform company, but also a hardware company and a spatial computing company. That broader identity could lead to more diverse revenue streams.

Fifth, it taught difficult lessons about capital allocation. Meta learned, expensively, that conviction plus resources doesn't equal market success. That lesson should influence future decisions about massive long-term bets.

The Path Forward: What Needs to Happen Next

For Meta to successfully transition from the metaverse bet to a profitable Reality Labs business, several things need to happen:

Hardware excellence: Smart glasses need to be genuinely good. The hardware needs to be comfortable, reliable, useful, and well-designed. This requires sustained engineering excellence.

Killer applications: There need to be specific use cases that make smart glasses so useful that people want to wear them daily. This might be work applications, navigation, communication, or something nobody has thought of yet.

Ecosystem development: Developers need to build applications for smart glasses. This requires clear development tools, a business model that works for developers, and a large enough user base to justify investment.

Consumer adoption: Millions of people need to start wearing smart glasses. This requires the devices to be affordable (or perceived as worth the cost), attractive, and solving real problems.

Profitability: Ultimately, Reality Labs needs to become a business that generates profit or at minimum doesn't generate losses. This requires either higher hardware sales volume, higher margins, or successful software and services business models.

Strategic patience with realistic expectations: Meta needs to invest in the right technologies without over-committing resources to speculative bets. The company got burned by believing the metaverse was inevitable. It needs to let smart glasses prove themselves in the market rather than assuming they will inevitably succeed.

The Timeline Question

How long will this take? Zuckerberg suggested gradual loss reduction starting in 2026. But gradual could mean five years or ten years. Getting to significant scale in smart glasses adoption could take a decade or more.

That's a long time for shareholders to wait for profitability. But in the context of building entirely new product categories, it's actually reasonable. Smartphones took nearly a decade to become the dominant computing platform. AR glasses might follow a similar trajectory, or it might take longer.

The key is that Meta is finally taking a more measured approach. The company isn't betting the entire business on smart glasses. It's investing in them strategically while continuing to generate massive cash flows from its core advertising business.

What This Means for the Broader VR and AR Industry

Meta's pivot from VR to AR has implications beyond just Meta. It signals to the industry that the consumer VR revolution that many people predicted hasn't materialized, and may not materialize for years.

This affects other VR companies. Sony, HTC, and others making VR headsets need to recognize that the market is limited. The boom in VR adoption that everyone expected hasn't happened. These companies need to find profitable niches rather than expecting mass-market adoption.

But it's bullish for AR. Meta's massive investment in AR research, its commitment to building AR glasses, and the company's expectation that AR will eventually be much larger than VR all signal that AR is probably the more likely spatial computing platform for the future.

This should encourage companies building AR technology, AR software, and AR applications. It validates that AR is where the real opportunity is.

For consumers, it means waiting longer for the next major computing platform. Smart glasses won't be ubiquitous tomorrow. But the research, investment, and focus that Meta is directing toward AR suggests that genuinely useful AR glasses are probably closer than many people think.

FAQ

What is Reality Labs and why did it lose so much money?

Reality Labs is Meta's division focused on virtual and augmented reality technologies. It lost over nineteen billion dollars in 2025 primarily because Meta massively invested in building the metaverse (a virtual world platform) that consumers showed minimal interest in adopting. The company spent billions on hardware development, software infrastructure, acquisitions, and marketing for products that failed to achieve meaningful consumer adoption. The losses accumulated over years as Meta continued investing in metaverse technologies despite weak market demand.

Why is Meta shifting away from the metaverse?

Meta is shifting away from the metaverse because the strategy wasn't delivering results. Despite years of investment and development, the virtual reality social platforms Meta built saw minimal user adoption. Simultaneously, Meta's smart glasses division showed genuine consumer demand with sales more than tripling in 2025. The company realized that enhancing reality through AR glasses is more appealing to consumers than asking them to replace reality entirely with virtual worlds. This pivot is driven by actual market signals rather than theoretical positioning.

What makes smart glasses more promising than VR headsets?

Smart glasses offer several advantages over VR headsets. They're lighter and more comfortable for all-day wear, they keep users aware of their actual surroundings, they enhance reality rather than replacing it, they're socially acceptable in public settings, and they solve more intuitive problems like accessing information hands-free. Additionally, smart glasses integrate more naturally with smartphones and existing consumer behavior patterns. While VR is suitable for entertainment in specific contexts, smart glasses have broader potential applications in daily life.

How much did Meta actually spend on the metaverse and Reality Labs?

Meta's losses from Reality Labs totaled approximately nineteen billion dollars in 2025 alone, and the division accumulated massive losses across multiple previous years. Estimates of the total spending on metaverse and Reality Labs infrastructure since the 2021 rebrand range from seventy to eighty billion dollars. This includes hardware development, software infrastructure, acquisitions of AR and VR companies, content studio funding, and marketing. It represents one of the largest single technology bets any company has made on an unproven future platform.

When will Reality Labs become profitable?

Meta's CEO stated that 2025 will likely represent the peak of Reality Labs losses, with gradual reductions starting in 2026. However, "gradual reduction" doesn't specify when actual profitability will occur. Reaching profitability likely requires smart glasses to become a mass-market product, which could take several years or a decade depending on adoption rates. The company expects to reduce losses significantly but hasn't committed to a specific timeline for profitability or provided financial projections for future years.

What can future AI-powered smart glasses actually do?

Future AR glasses integrated with AI could provide real-time information overlays about your environment, enable hands-free communication and notifications, assist with navigation and wayfinding, support professional workflows by overlaying technical information, and enable new forms of social interaction. The AI integration means the glasses don't just display information but actively understand your context, location, preferences, and goals to proactively suggest helpful actions and information without requiring you to explicitly request anything.

How does Meta's smart glasses strategy compare to competitors like Apple and Google?

Meta is taking an earlier-to-market approach with consumer smart glasses focused on social sharing and AI assistance. Apple is pursuing a high-end spatial computing approach with the Vision Pro while researching consumer AR glasses for future release. Google has the search and mapping data that could make AR glasses particularly useful but hasn't released a consumer product yet. Snap is iterating on camera-equipped glasses. The competitive landscape suggests that AR glasses will eventually become important, but it's unclear which company's approach will ultimately dominate the market.

Did Meta waste seventy billion dollars on the metaverse?

Whether the metaverse investment was wasted depends on perspective. Meta developed genuine technological capabilities in spatial computing, hardware manufacturing, and AR research that it's now applying to smart glasses. The company attracted and retained talented engineers focused on emerging technology. However, the company over-invested in a specific vision of the metaverse that market demand didn't support, and that resulted in enormous financial losses that shareholders have rightly questioned. The investment wasn't productive for the original goal but may prove valuable for new applications.

The Bottom Line: From Metaverse Billions to Smart Glasses Future

Meta's Reality Labs pivot represents both a failure and a course correction. It's a failure because the company bet billions on a metaverse vision that simply didn't materialize. No amount of engineering excellence or marketing can force consumers to embrace something they don't want. That's a hard lesson, and it cost Meta shareholders tens of billions of dollars.

But it's also a course correction because the company is finally taking market signals seriously. Consumer interest in VR remained tepid despite years of investment. Consumer interest in smart glasses is growing. The company is reallocating resources accordingly.

What makes this pivot significant is that it suggests Meta is learning from its mistake. The company isn't doubling down on a failed strategy. It's not trying to force the metaverse by investing even more aggressively. Instead, it's redirecting resources toward technologies where actual consumer demand exists.

The question now is whether smart glasses can actually deliver on the promise. The technology is genuinely interesting. AI integration could make smart glasses genuinely useful. The market opportunity is enormous. But execution matters. Meta needs to build products that people actually want to wear, create applications that solve real problems, and develop business models that work.

Zuckerberg's prediction that Reality Labs losses will peak in 2025 and gradually decline is important. It signals that the era of unlimited investment in speculative platforms is ending. Reality Labs will continue to be an investing area, but it will be expected to show progress toward profitability.

For the tech industry and consumers interested in future computing platforms, Meta's pivot is instructive. It shows that even the largest, most well-resourced technology companies can misjudge market demand. It also shows that pivoting is possible, even if it's expensive. And it suggests that augmented reality, not virtual reality, is probably the spatial computing platform that will eventually matter.

The metaverse as originally envisioned isn't dead, but it's been deprioritized. AR glasses, powered by AI and integrated with Meta's massive user base and software ecosystem, represents the company's best bet for building the next major computing platform. Whether that bet succeeds remains to be seen. But at least it's based on actual market signals rather than wishful thinking about inevitable futures.

Key Takeaways

- Meta lost $19 billion in Reality Labs during 2025 alone, representing one of technology's largest failed strategic bets

- The metaverse vision that consumed eighty billion dollars failed to achieve meaningful consumer adoption despite years of investment

- Smart glasses sales have more than tripled, demonstrating genuine consumer demand contrasts sharply with metaverse platform struggles

- Mark Zuckerberg expects 2025 to represent peak losses with gradual reductions as focus shifts to AI-powered glasses and wearables

- The strategic pivot from VR replacement to AR enhancement represents fundamental learning about what consumers actually want

Related Articles

- Meta's Reality Labs Layoffs: What It Means for VR and the Metaverse [2025]

- Meta's VR Pivot: Why Andrew Bosworth Is Redefining The Metaverse [2025]

- Snap's AR Glasses Spinoff: What Specs Inc Means for the Future [2025]

- Meta's Quest 3 Horizon Integration Removal: What It Means [2025]

- Meta's Horizon Workrooms Shutdown: Why VR Meeting Rooms Failed [2025]

- Meta Display Smart Glasses: Why Demand Exceeds Supply [2025]

![Meta Reality Labs: From Metaverse Losses to AI Glasses Pivot [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/meta-reality-labs-from-metaverse-losses-to-ai-glasses-pivot-/image-1-1769639844205.jpg)