How Microsoft's Bet on Superconductors Could Transform Data Center Efficiency

Your data center is burning money every single day. Not just on electricity bills, but on heat loss alone.

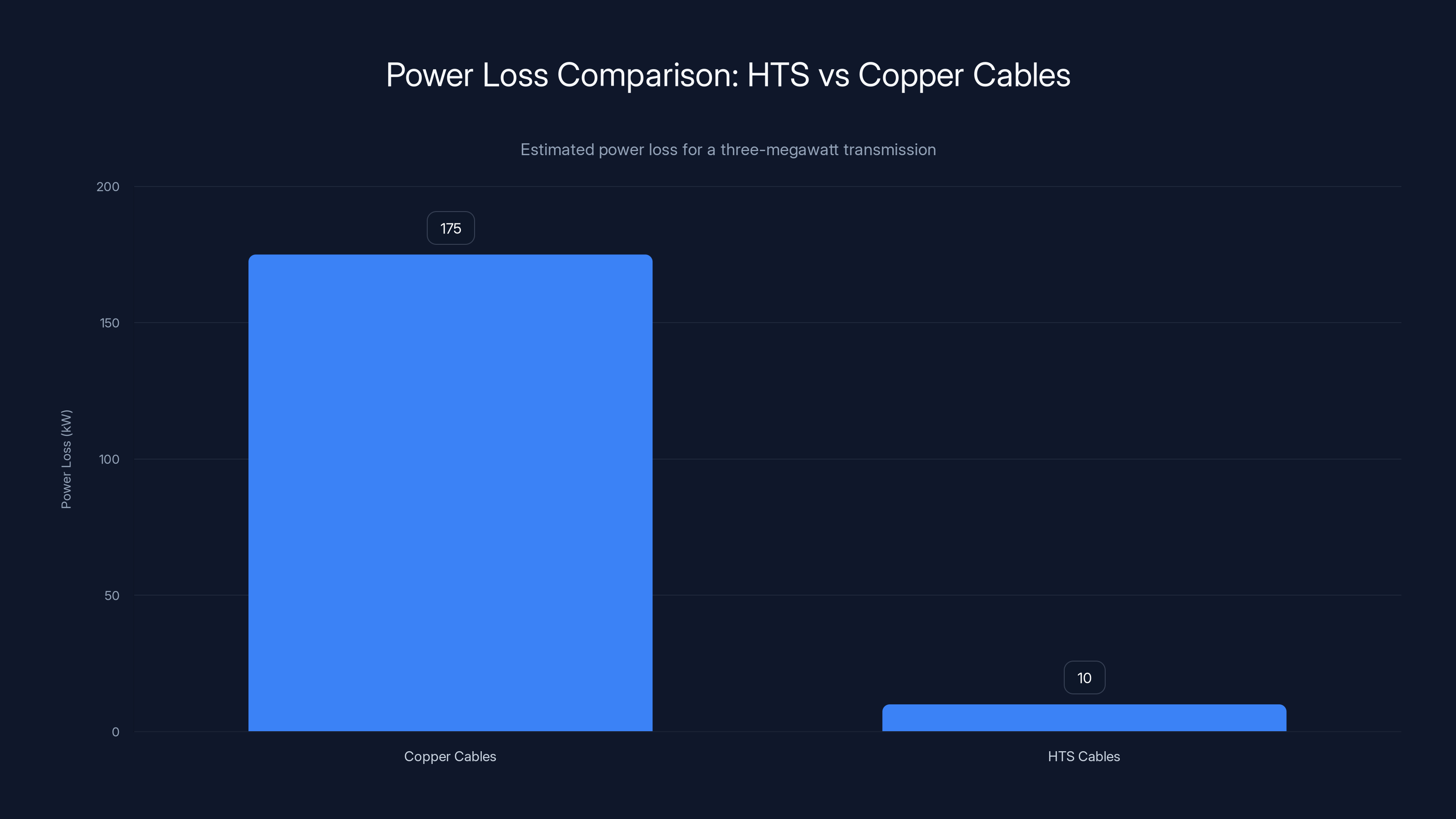

Think about it: every time electricity flows through copper or aluminum cables, it generates heat. Resistive heating. It's unavoidable with traditional conductors, and it wastes enormous amounts of energy. For a three-megawatt power transmission, traditional copper cables would shed between 150 to 200 kilowatts as pure waste heat. That's not a rounding error. That's a second or third data center's worth of cooling costs just disappearing into the air.

Now, what if you could eliminate that loss almost entirely?

Microsoft isn't just talking about the future anymore. The company has invested heavily in high-temperature superconducting (HTS) technology through a partnership with Veir, a startup building the next generation of data center power systems. And in November 2024, Veir demonstrated exactly what this could look like: three megawatts of power flowing through a single superconducting cable in a controlled environment, with virtually zero resistive losses as reported by Microsoft.

This isn't science fiction. It's happening right now. But it's also incredibly complicated, wildly expensive, and probably still years away from real-world deployment at scale according to The Register.

Here's what you actually need to know about why Microsoft is betting billions on this technology, how it actually works, what stands in the way, and whether it'll ever actually become standard in data centers worldwide.

TL; DR

- HTS technology eliminates resistive heat loss: Superconducting cables transmit electricity with near-zero resistance using liquid nitrogen cooling, eliminating 150-200 kW of waste heat per three-megawatt transmission as noted by Data Centre Magazine.

- Veir demonstrated three megawatts in November 2024: The proof-of-concept successfully showed that HTS could work in simulated data center environments, a major technical milestone reported by Windows Report.

- Power density increases without infrastructure expansion: HTS enables denser power delivery without expanding electrical substations or adding multiple parallel cables as explored by WIMZ.

- Major obstacles remain: High material costs, cooling complexity, supply constraints, and voltage limitations mean commercial deployment likely won't happen until 2026 at the earliest, with Microsoft deployment potentially years beyond according to 36Kr.

- Industry game-changer if viable: If costs drop and reliability improves, HTS could reshape how data centers are designed, reducing cooling expenses and operational footprints significantly as discussed by TechRadar.

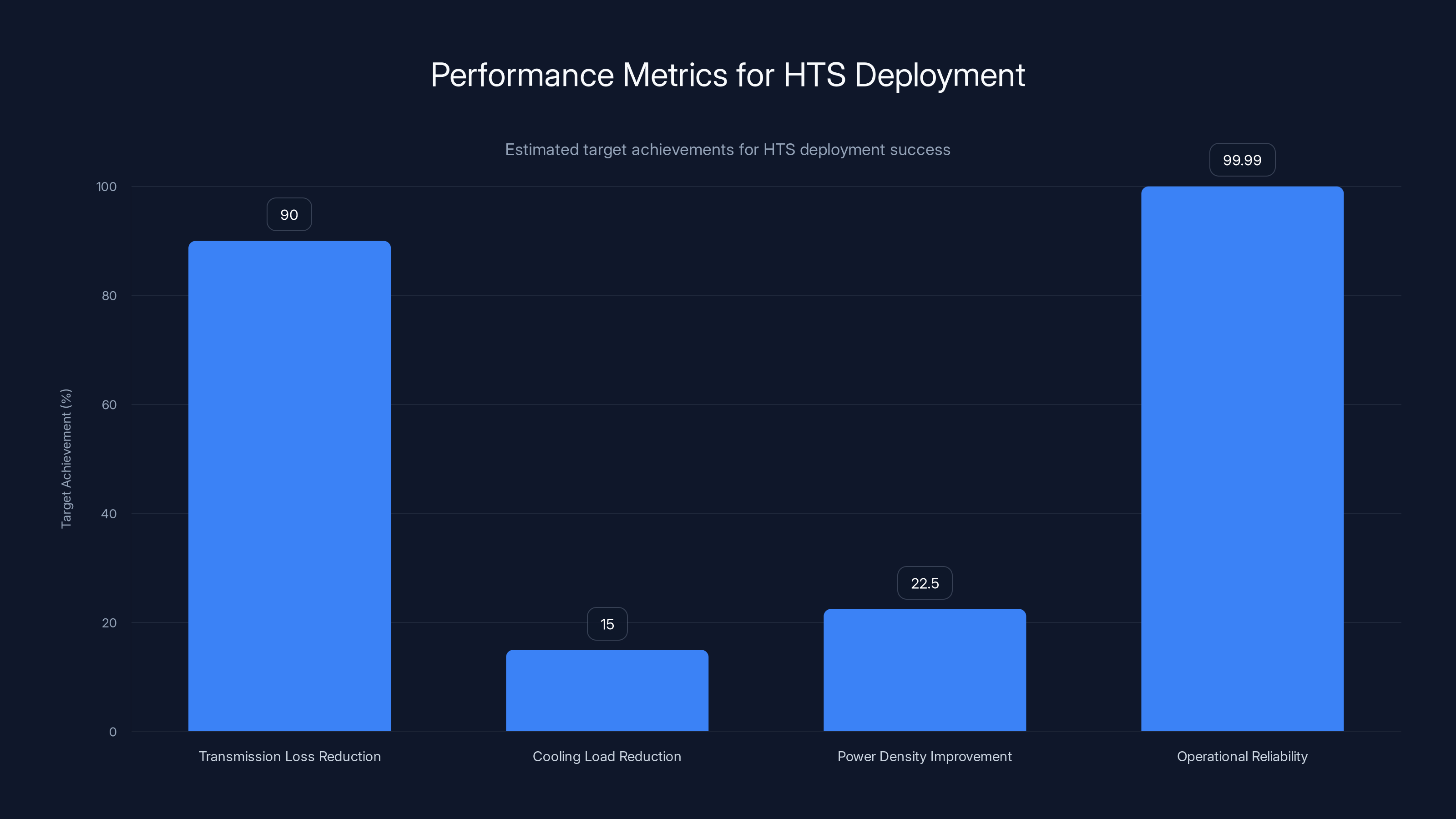

Estimated data shows HTS deployment aims for significant improvements: over 90% reduction in transmission losses, 15% reduction in cooling load, 22.5% increase in power density, and 99.99% operational reliability.

The Physics Problem Nobody Talks About: Resistive Heating in Power Transmission

Let's start with a basic reality: electricity doesn't teleport. It has to travel through physical conductors, and those conductors resist the flow of current. This resistance creates heat, described by Joule's law in physics.

The power dissipated as heat follows this equation:

Where P is power lost as heat (watts), I is current (amperes), and R is resistance (ohms).

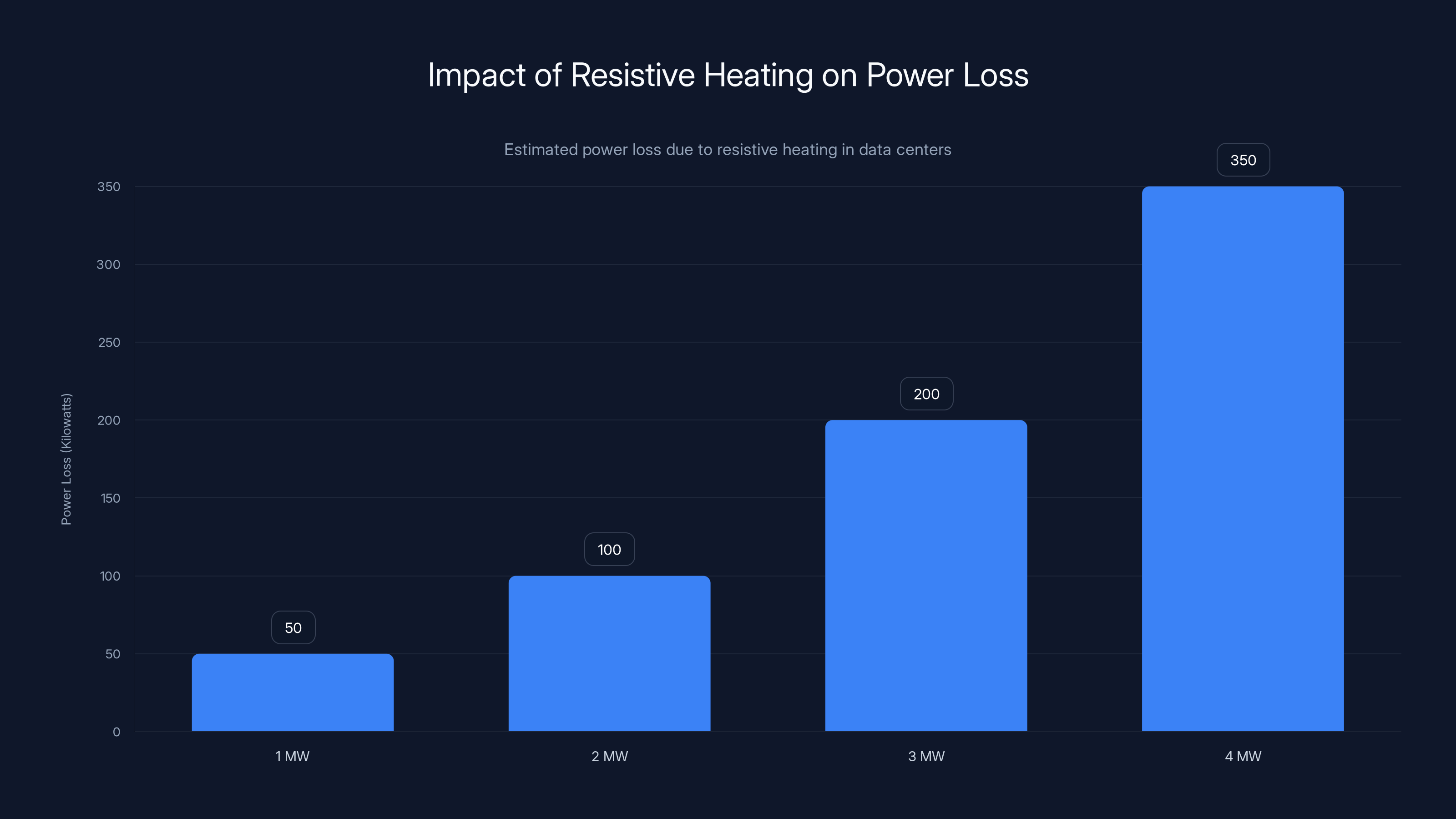

So here's the problem: as your data center grows and demands more power, you need to pump more current through those cables. But when you increase current, power loss increases exponentially. Double the current, and you quadruple the heat generated.

For a data center pulling three megawatts of power through traditional aluminum or copper conductors, that equation becomes devastating. You're looking at 150 to 200 kilowatts of pure waste heat. Every single day. Every single month. Year after year.

That's not just an efficiency problem. That's a cascading infrastructure problem. You need cooling systems to remove that heat. You need bigger chillers. You need more water. You need better ventilation. You need redundancy in case cooling fails. All of that adds cost, complexity, and footprint.

Traditional solutions to this problem involve either accepting the losses or using thicker cables and multiple parallel conductors to spread the current across more cross-sectional area. But spreading the current means needing more physical space, more connection points, and more material. Your electrical room becomes cramped. Your power distribution grows exponentially.

Microsoft and data center operators everywhere have been working around this fundamental physics problem for decades. It works. But it's inefficient, expensive, and becomes increasingly impractical as computational demands keep accelerating.

Then superconductors enter the room.

What Makes High-Temperature Superconductors Different from Everything Else

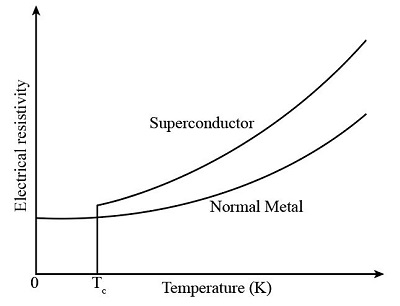

A superconductor is a material that exhibits zero electrical resistance when cooled below a certain temperature called the critical temperature.

Zero resistance.

Let me repeat that because it's absolutely wild: zero electrical resistance. Not low resistance. Not pretty good resistance. Zero.

When a superconductor reaches its critical temperature, the electrons inside it stop colliding with the atomic lattice. They form paired states called Cooper pairs, and they flow through the material without any dissipation whatsoever. No friction. No heat generation. Just pure, lossless transmission of electricity.

But here's the catch: traditional superconductors required cooling to liquid helium temperatures, around 4 Kelvin or minus 269 degrees Celsius. That's absurdly cold. That's space-cold. That's the kind of cold that makes everything brittle and difficult to work with.

High-temperature superconductors, on the other hand, transition into superconducting states at the critical temperature of around 77 Kelvin, which is the boiling point of liquid nitrogen.

Liquid nitrogen.

Nitrogen is the most abundant element in Earth's atmosphere. We can produce it cheaply almost anywhere. It doesn't require specialized supply chains or exotic handling procedures the way liquid helium does. It's still incredibly cold, but it's infinitely more practical for industrial applications.

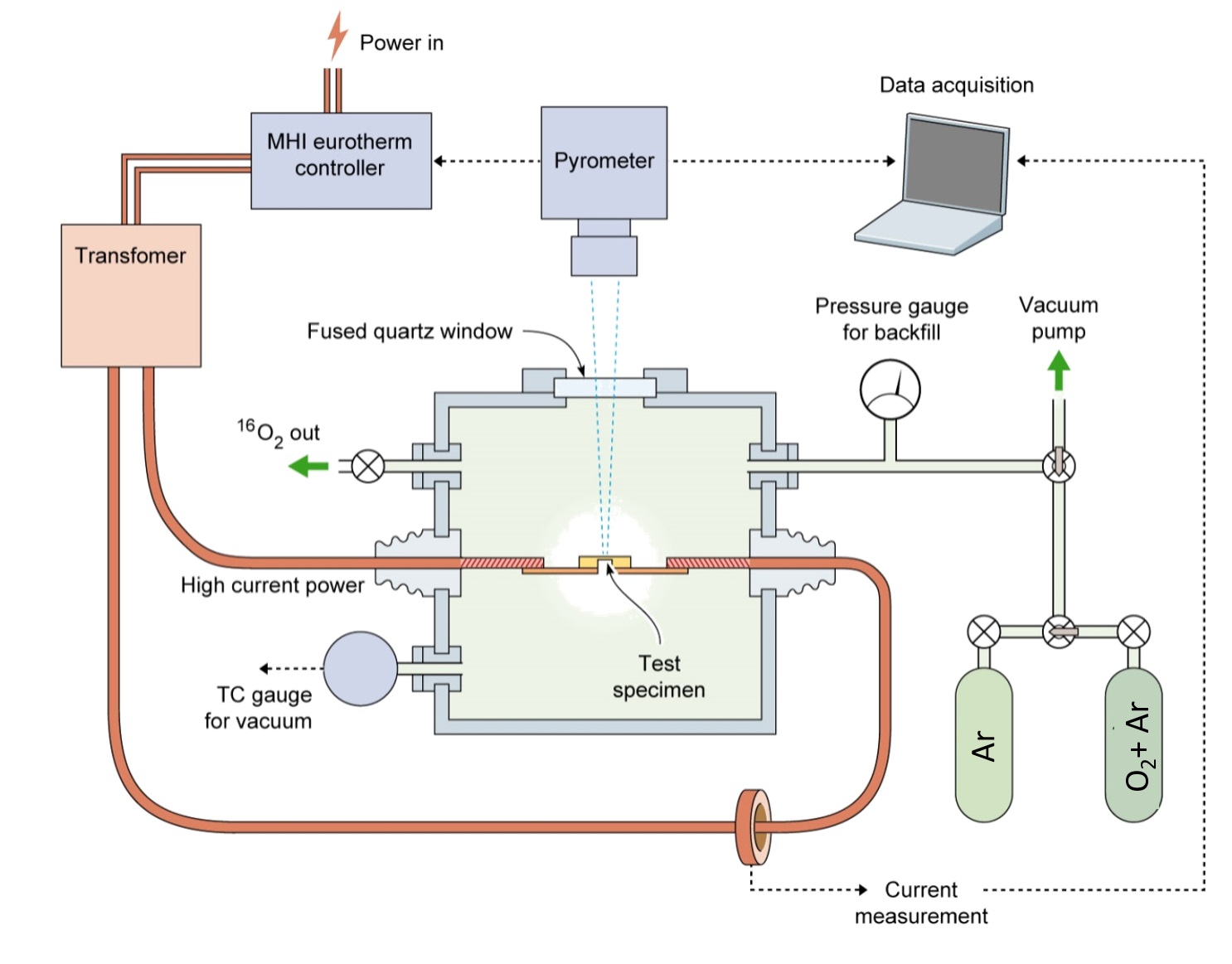

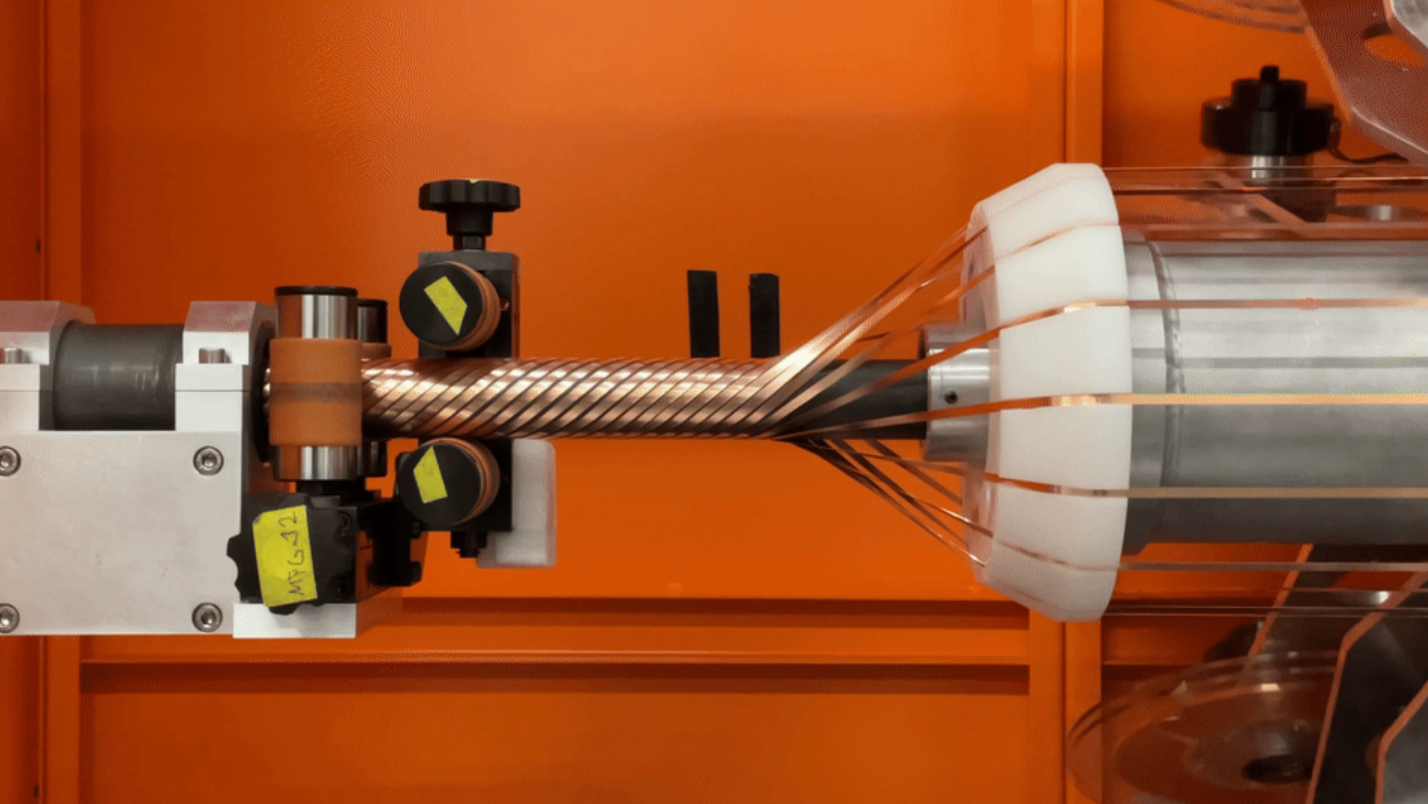

Veir's approach uses yttrium barium copper oxide (YBCO) based superconducting wire, cooled by liquid nitrogen circulation. The wire is wound into cable configurations optimized for three-phase power distribution. When cooled, the current flows through the superconductor with virtually no resistance as detailed by Farmonaut.

The difference in performance is staggering. Where traditional copper cables would waste 150 to 200 kilowatts as heat over a three-megawatt transmission, an HTS cable maintains the same performance with losses measured in kilowatts instead of hundreds of kilowatts.

That efficiency gain cascades throughout the entire data center. Less heat generation means less cooling demand. Less cooling demand means smaller chillers, less water consumption, lower electricity bills for cooling infrastructure, and more space available for actual computational equipment.

Microsoft estimates that HTS technology could enable data center designs that are significantly more compact and power-dense than current approaches allow according to The Register.

HTS cables can reduce power loss by approximately 90-95% compared to copper cables for a three-megawatt transmission, highlighting their efficiency advantage.

The November 2024 Demonstration: What Actually Happened

In November 2024, Veir conducted what it characterized as the first successful demonstration of HTS cables delivering three megawatts of power in a simulated data center environment.

This wasn't just lab equipment on a bench. The demonstration used multiple superconducting cables configured to handle three-phase power, the standard power distribution system used in real data centers. The cables were cooled with liquid nitrogen circulation, and the system successfully transmitted power while maintaining superconducting conditions throughout the test as reported by WIMZ.

Three megawatts might not sound enormous to anyone familiar with utility-scale power, but for a data center context, it's a meaningful proof point. A modern data center might have multiple three-megawatt feeds coming in from the utility grid. The ability to safely transmit that power through a single superconducting cable rather than multiple thick copper cables opens up entirely new possibilities for electrical architecture.

Microsoft recognized this immediately. The company has made strategic investments in Veir and publicly committed to evaluating the technology for potential deployment in future data center facilities as noted in Microsoft's blog.

But here's what's important to understand about demonstrations versus real-world deployment: a proof-of-concept that works for a few hours in a controlled laboratory environment is not the same as a system that runs reliably 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, in a production data center.

The test proved that the physics works. It didn't prove that the engineering is ready for prime time.

Comparing HTS Cables to Traditional Copper and Aluminum Conductors

Let's look at a detailed comparison of how HTS stacks up against the materials data centers have relied on for decades.

Electrical Resistance and Efficiency

Traditional copper has a resistivity around 1.68 × 10⁻⁸ ohm-meters at room temperature. Aluminum comes in around 2.65 × 10⁻⁸ ohm-meters. Both materials generate significant heat when carrying high currents over distance.

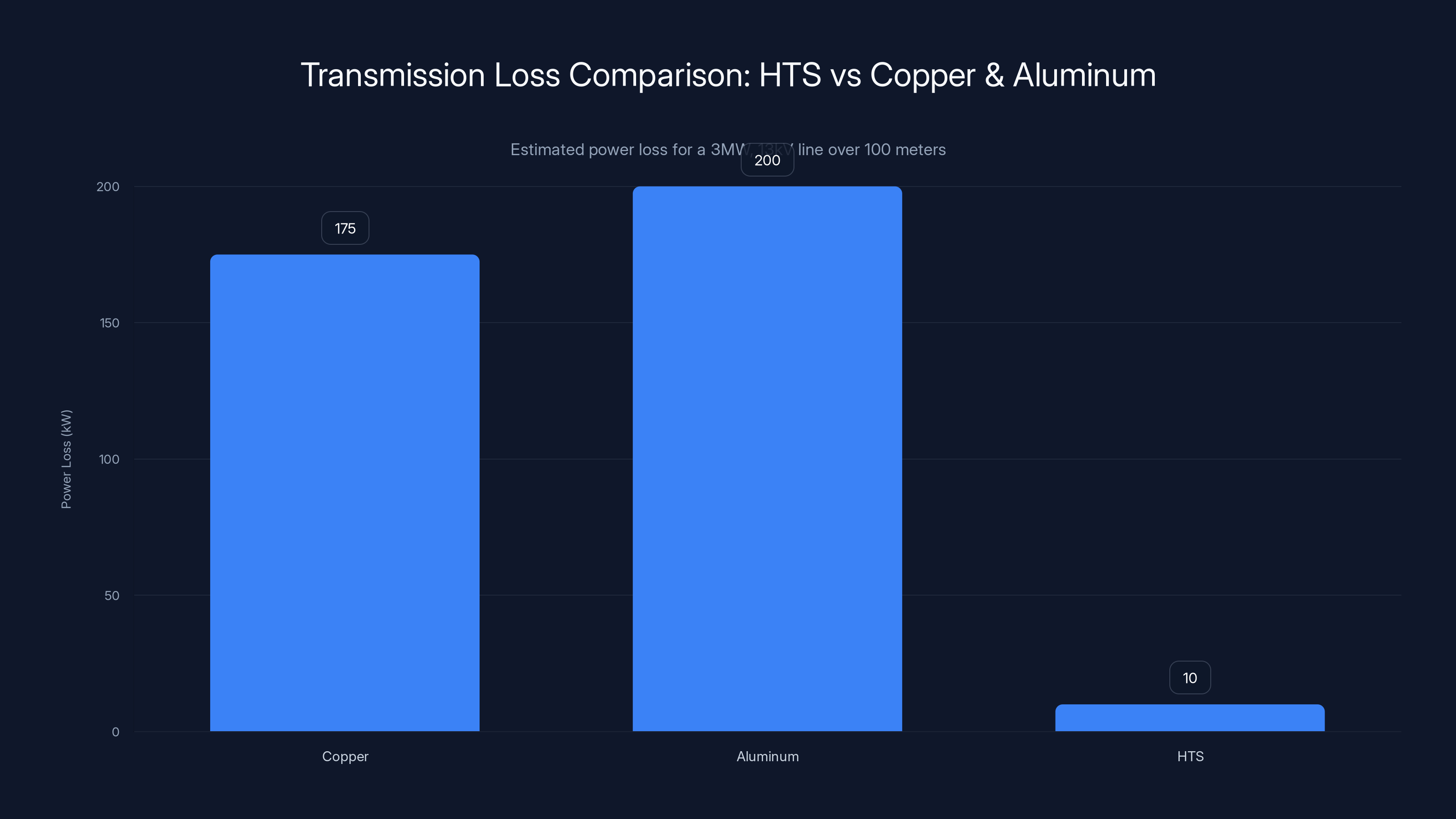

HTS cables have essentially zero resistivity below their critical temperature. The practical difference in transmission losses is enormous. For a three-megawatt, 13-kilovolt line over 100 meters:

- Copper cables: Approximately 150-200 kW of loss

- Aluminum cables: Approximately 180-220 kW of loss

- HTS cables: Approximately 5-15 kW of loss

That's not a marginal improvement. That's 90-95% reduction in transmission losses as highlighted by Windows Report.

Physical Space and Density

Copper and aluminum cables need to be thick enough to handle current without overheating. Three-megawatt transmission typically requires multiple parallel cables, each several inches in diameter, bundled together in cable trays or conduits.

HTS cables can achieve the same power transmission with a single cable that's often narrower and always lighter than the equivalent copper cable setup. A single HTS cable replacing three or four copper cables opens up massive space savings in electrical rooms, cable routing, and connection infrastructure as noted by Data Centre Magazine.

Installation and Flexibility

Traditional cables are relatively simple to install. Just run them through conduit, connect the terminals, and you're done. HTS cables require cryogenic cooling systems, which adds complexity. You need liquid nitrogen supply infrastructure, thermal insulation, cryogenic pumps, and monitoring systems.

The installation footprint is smaller, but the operational footprint is larger due to cooling requirements.

Cost Comparison

This is where the real tension emerges. Copper cables are cheap. Mature manufacturing, abundant material, proven supply chains. A three-megawatt copper transmission line might cost several tens of thousands of dollars.

HTS cables with their associated cooling systems cost significantly more. Estimates suggest HTS systems can be 3-10 times more expensive than equivalent copper solutions, though costs are declining as manufacturing scales up as discussed by TechRadar.

Even accounting for operational savings in cooling, the payback period for HTS is typically measured in years, not months. For many facilities, the initial capital cost is prohibitive.

Temperature Stability Requirements

Copper and aluminum work fine at room temperature. They're stable and predictable. HTS cables require continuous cooling to 77 Kelvin. If the cooling system fails, the superconductor warms above its critical temperature and instantly loses superconductivity, switching to normal resistive behavior.

That means you need redundant cooling systems, temperature monitoring, and failover capability. The system becomes less tolerant of failure modes.

Infrastructure Constraints: The Real Problem HTS Could Solve

Here's a scenario that data center operators face constantly: your facility is reaching maximum power density. You're pulling everything the utility can deliver through your existing substations and feeders. You want to deploy more servers, more GPUs, more computing capacity. But you can't, because your electrical infrastructure is maxed out.

Your choices are:

-

Build more electrical infrastructure: Expand substations, add new feeders, run new cables. This is expensive, time-consuming, and often requires working with local utilities, which means permitting, delays, and coordination challenges.

-

Accept reduced density: Don't pack servers as tightly. Give up potential revenue and computational capacity to stay within your power budget.

-

Deploy in new locations: Build a new data center facility elsewhere. But finding suitable locations, getting permitting, and building from scratch takes years and massive capital investment.

HTS cables offer a fourth option: transmit the same power through your existing infrastructure pathway.

Where you previously needed three parallel copper cables to safely deliver power, an HTS cable might do the same job. You keep your existing cable routing infrastructure, your existing breakers and disconnects, your existing substations. But you can push more power through them.

This density advantage becomes absolutely critical for companies like Microsoft operating in dense urban environments or locations where electrical infrastructure expansion is difficult or impossible as explored by WIMZ.

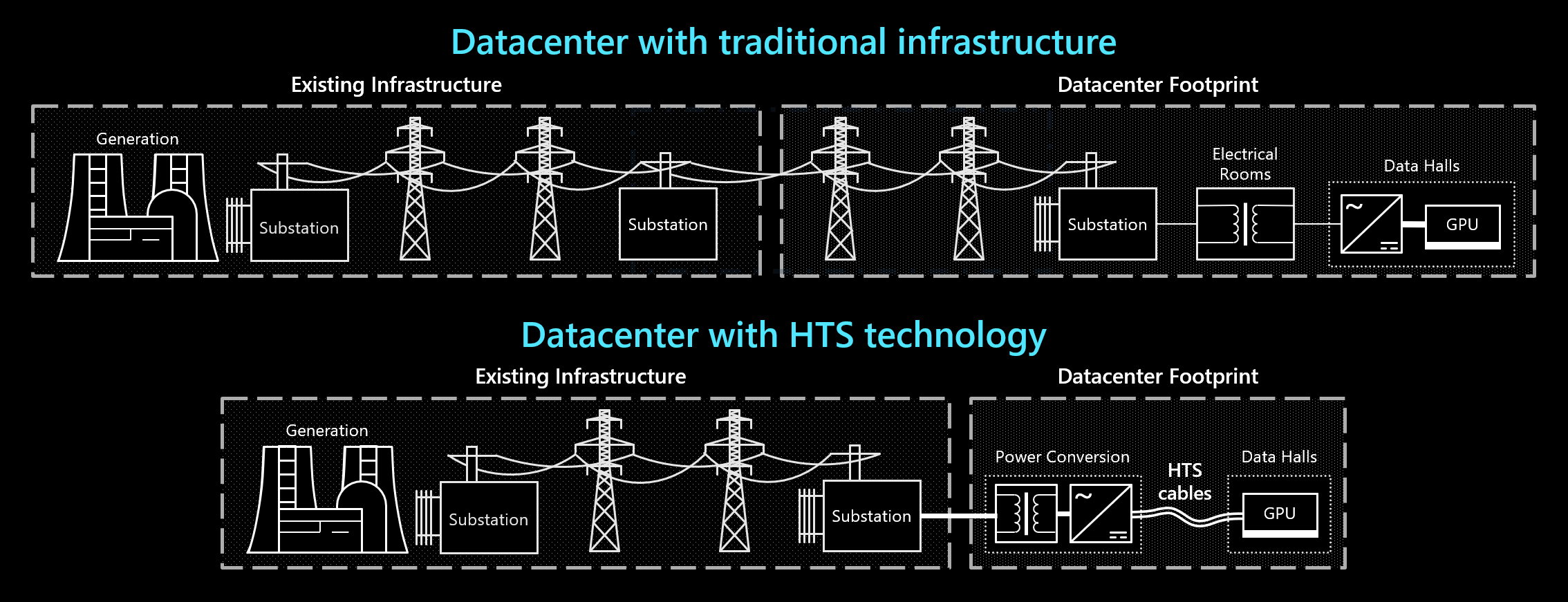

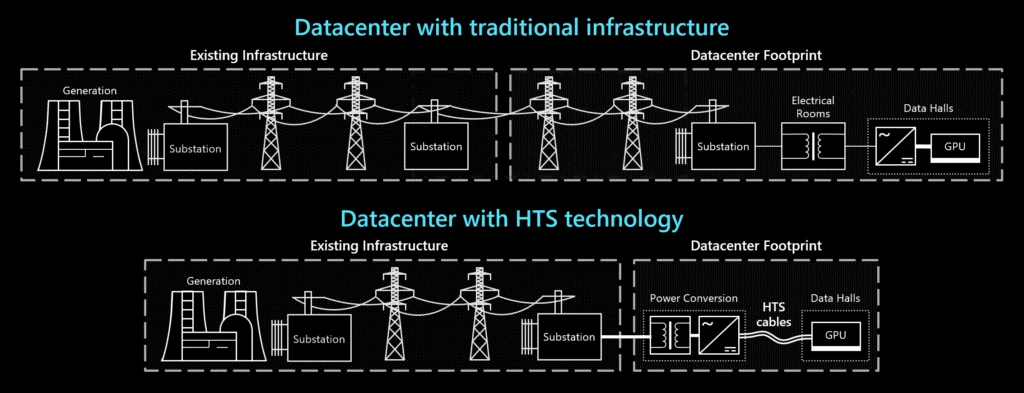

Microsoft's framing emphasizes exactly this point: HTS could "allow denser power delivery without expanding substations or adding additional feeders."

Translate that to business terms: HTS could delay or eliminate multimillion-dollar infrastructure expansion projects. That's enormous value, even if the HTS cables themselves cost more upfront.

Estimated data shows that as data centers increase power draw from 1 MW to 4 MW, resistive heating losses can rise from 50 kW to 350 kW, highlighting the need for efficient cooling solutions.

The Real Obstacles: Why HTS Isn't Standard Yet

If HTS is so great, why aren't we using it everywhere already? Why is Microsoft still in the "evaluation" phase instead of the "deployment" phase?

Because real-world engineering is far more complicated than laboratory demonstrations.

Material Supply and Scalability

Superconducting wire production is not a commodity manufacturing process. The companies that manufacture YBCO-based wire operate at limited scale. Producing enough HTS cable to retrofit or build a single hyperscale data center would stretch current global manufacturing capacity.

Scaling production to supply dozens of data centers would require building entirely new manufacturing facilities, training workers, establishing quality control processes, and dealing with all the complexity of scaling a precision manufacturing process as noted by 36Kr.

Microsoft and other companies interested in HTS are not alone in wanting this technology. Utility companies, renewable energy infrastructure, electric vehicle charging networks, and other industries all see potential. That creates competition for limited production capacity.

Wire manufacturers are expanding capacity, but ramping production to meet potential demand takes years and billions in capital investment.

Cooling System Complexity

Liquid nitrogen cooling isn't exotic, but it's also not trivial. You need reliable cryogenic pumps, insulated cryogenic piping, temperature monitoring systems, and failover capability. The cooling infrastructure needs to be maintained, inspected, and operated by trained technicians.

Compare that to copper cables, which require basically zero ongoing maintenance. They just sit there and work for decades.

For HTS, you're introducing new failure modes. Pump failure. Insulation failure. Temperature sensor failure. Any of these could force the system offline while repairs happen.

Data centers are designed around extreme redundancy and availability. Introducing a technology that's less mature and has more failure modes is a significant risk that engineers need to carefully evaluate.

Cost Economics and Payback Period

Even if you account for cooling savings, the economics are marginal for most facilities. The capital cost for HTS is high. The operational savings accumulate slowly.

For a company like Microsoft, with a 5-10 year planning horizon and the ability to amortize costs across hundreds of facilities, the investment might make sense. For smaller operators, the payback period might stretch beyond their planning horizon.

Until HTS cable costs drop significantly, adoption will likely be limited to leading hyperscalers who can absorb the risk and costs.

Voltage and Power Level Constraints

Most HTS demonstrations and deployments have been at relatively low voltage levels and moderate power levels. Scaling HTS to utility-level voltages (hundreds of kilovolts) introduces additional technical challenges.

HTS performance can degrade in high magnetic field environments, and power system voltages create significant magnetic fields. The technology works well at distribution voltages (13 kV to 69 kV), but extending it to transmission voltages requires additional development.

For data center applications, distribution voltage is actually perfectly appropriate, but for broader utility applications, voltage limitations restrict where HTS can help.

Standards and Testing

Electrical equipment for data centers and utilities operates under strict standards. Equipment needs to be tested, certified, and validated against those standards. New HTS systems need to go through this entire process.

There's no existing body of operating experience. Engineers and operators are cautious. Proving reliability, safety, and performance at production scale takes time.

Microsoft's Strategic Positioning: Why Now?

Microsoft isn't investing in HTS because the company is being impulsive or chasing shiny new technology. The company's recent public statements about data center power constraints are remarkably candid.

Microsoft has committed to deploying enormous capacity for artificial intelligence workloads. AI models require GPUs. GPUs require power. Lots of power.

Microsoft has also committed to ambitious carbon reduction goals and operational sustainability improvements. More power-efficient infrastructure supports those commitments.

And Microsoft operates in a competitive landscape where Amazon Web Services and Google Cloud are also building massive AI infrastructure. Every efficiency gain translates to cost advantage and capability advantage.

HTS technology checks multiple boxes for Microsoft:

- Enables denser deployments in existing facilities without waiting for utility infrastructure upgrades

- Reduces cooling costs, improving operational economics

- Improves sustainability by eliminating resistive heating losses

- Provides optionality for handling extreme power density demands from AI workloads

- Positions Microsoft as an innovator in data center technology

From a strategic perspective, Microsoft's investment makes sense even if widespread deployment is still years away. The company is hedging against the risk that power density demands outpace utility infrastructure expansion.

If HTS matures faster than expected, Microsoft gets first-mover advantage. If it matures slower than expected, the company still has conventional alternatives. Either way, the investment provides strategic optionality.

The AI Workload Factor: Why Power Density Matters Now More Than Ever

Traditional data center planning assumed gradual, predictable growth in computational demand. You could plan infrastructure expansion in 3-5 year cycles and be pretty confident about capacity.

AI workloads broke that assumption.

AI training requires GPUs. Modern GPU clusters for large language models require enormous amounts of power. A single data center cluster might draw 10-100 megawatts continuously, far more than traditional computational workloads of similar economic value.

The power density (megawatts per square foot or per kilogram of equipment) jumped by orders of magnitude.

Data center operators are suddenly constrained not by rack space but by available electrical power. Utility connections that seemed adequate a year ago are now bottlenecks.

For Microsoft, OpenAI, Google, and other companies racing to build AI capability, power availability is no longer a nice-to-have. It's a blocker. If you can't get power to the facility, you can't deploy GPUs, regardless of available space or cooling.

HTS technology directly addresses this constraint. By enabling denser power delivery, HTS could unlock deployment capacity that would otherwise be constrained by utility infrastructure.

That's why Microsoft is suddenly willing to invest in a technology that's still in development. The company needs solutions to power constraints, and HTS is one of the more promising options.

HTS cables show a dramatic reduction in power loss, with only 5-15 kW compared to 150-220 kW for copper and aluminum. Estimated data.

Timeline Reality: When Will HTS Actually Be Deployed in Production?

Microsoft's statements have been carefully qualified. The company said HTS "remains in the development and evaluation stage for adoption at Microsoft's scale."

Translate that: not yet.

Veir is targeting commercialization in 2026, meaning the company plans to have products available for purchase by that date. But Veir's commercialization might look like limited production runs, beta customer deployments, and operational experience gathering as noted by The Register.

Microsoft's actual deployment in production data center facilities could easily be 2027, 2028, or later. The company needs to:

- Complete engineering and design for HTS integration into data center power systems

- Build one or more test deployments to validate reliability and performance

- Work out operational procedures and training

- Establish supply chain relationships with HTS manufacturers

- Handle permitting and utility coordination

- Deploy at scale

Each of these steps takes time.

Realistic expectations: HTS cable deployment in some Microsoft data centers by 2027-2028. Broader adoption across the industry by 2030s. Transformation of data center power architecture by 2035+.

That's not imminent. That's "the future we're preparing for now."

But it also matches the timeline for other major infrastructure investments. Microsoft is playing a long game. The company is placing bets on technologies that might be game-changing 5-10 years from now.

Competing Approaches to Data Center Power Management

While Microsoft is betting on HTS, other organizations are exploring different approaches to the same fundamental problem: how to safely, efficiently, and flexibly deliver power to increasingly power-dense facilities.

Advanced Cooling Approaches

Some companies are pursuing better cooling technologies. Immersion cooling, where servers are submerged in dielectric fluid, removes heat much more efficiently than air cooling. Liquid cooling, where coolant flows directly through server components, is increasingly common.

Better cooling doesn't solve the resistive heating problem in power cables, but it can reduce the cooling burden, which has economic benefits.

Modular Power Systems

Other approaches focus on distributing power generation closer to where it's needed. On-site renewable energy, battery storage, and local power conversion can reduce dependence on utility-delivered power.

Google has made significant investments in renewable energy integration. Other companies are exploring similar approaches.

Infrastructure Expansion

The traditional approach is just more expensive than it's worth. Invest in upgrading utility connections, expanding substations, and adding new feeders. It works, but it's slow and capital-intensive.

Grid Services and Optimization

Adaptive management approaches like demand flexibility, load shifting, and dynamic power allocation can squeeze more capability out of existing infrastructure without hardware changes.

None of these approaches are mutually exclusive. Companies will likely pursue multiple strategies simultaneously. HTS is one tool in the toolkit, not a silver bullet.

Practical Challenges Beyond Physics and Engineering

Superconductors face challenges that aren't just about electrons and thermodynamics. They face real-world practical challenges that slow adoption.

Supply Chain Fragility

HTS wire manufacturing is concentrated in a handful of companies. Disruptions in supply can create shortages. There's also intellectual property complexity, with different manufacturers using different designs and requiring different cooling approaches.

Building a robust supply chain for a technology that's just entering commercialization is risky. Early adopters often face supply constraints and extended lead times.

Training and Expertise

Data center operations teams are trained on conventional power systems. They know how to work with copper cables, breakers, and distribution transformers. HTS requires different training.

Cryogenic systems, specialized monitoring equipment, different failure modes, different troubleshooting procedures. Operating an HTS system requires expertise that few technicians currently possess.

That expertise gap will close over time, but in the near term, it's a real obstacle to adoption.

Regulatory and Standards Uncertainty

Electrical codes and standards for HTS systems are still being developed. Different jurisdictions might have different requirements. Utilities might have different policies about accepting HTS systems into their network.

That regulatory uncertainty creates risk for early adopters. You might invest in HTS infrastructure only to discover that your local utility won't accept it, or that a code change requires upgrades.

Risk of Rapid Technology Evolution

HTS cable technology is improving rapidly. Materials are getting better. Manufacturing is becoming more efficient. Costs are dropping.

If you deploy first-generation HTS systems today, you might find that second-generation systems deployed a few years from now are significantly better and cheaper. That creates risk of stranded investment or obsolescence.

Large organizations like Microsoft can absorb that risk. Smaller organizations might prefer to wait.

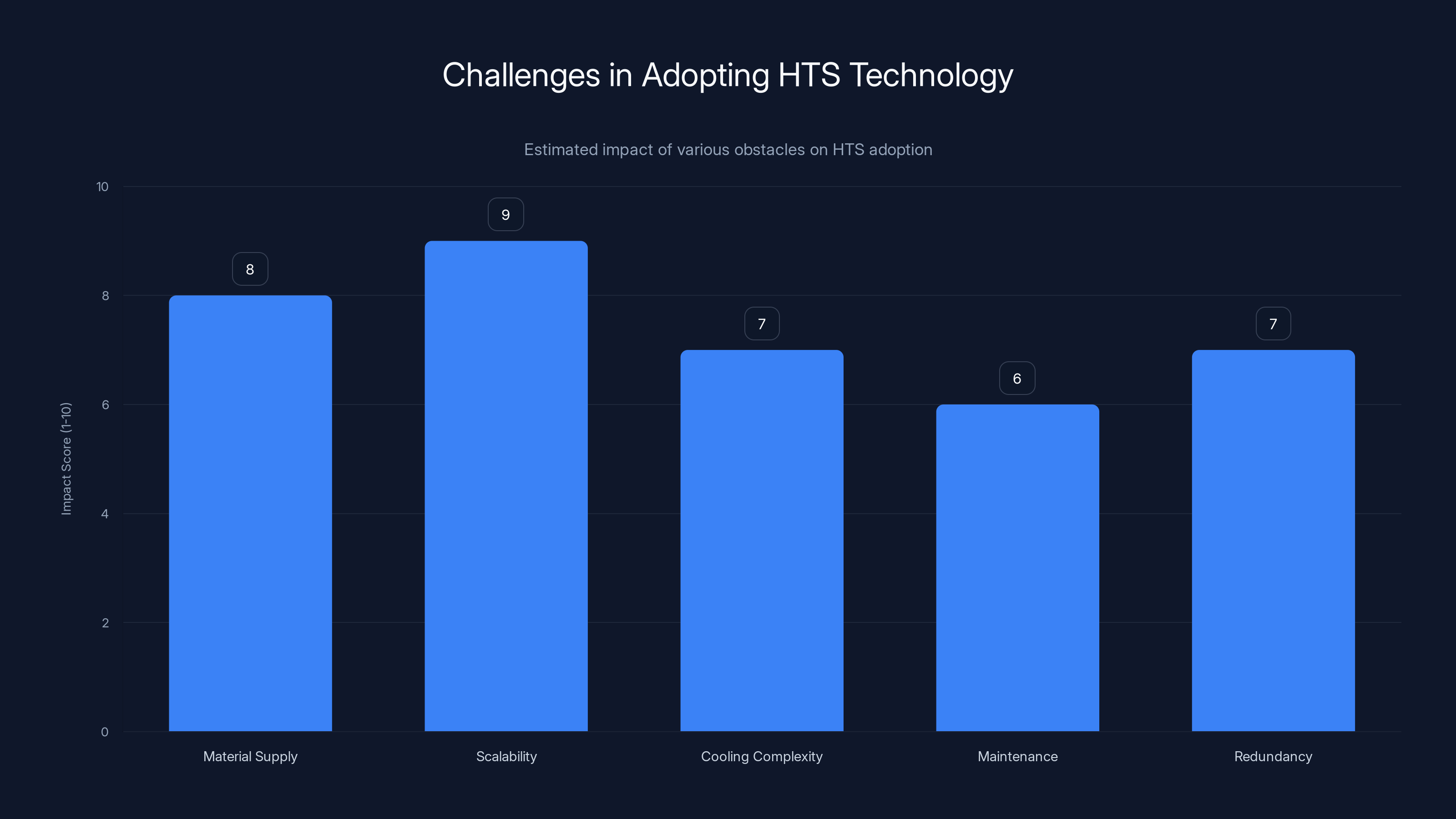

Material supply and scalability are the most significant obstacles to HTS adoption, with high impact scores. Estimated data.

Comparing HTS to Alternative Solutions for Power Delivery Challenges

Let's step back and look at the broader solution space. If you're facing power delivery constraints, what are your actual options?

Option 1: Utility Infrastructure Expansion

Approach: Work with your local utility to expand electrical service to your facility.

Timeline: 2-5 years (planning, permitting, design, construction)

Cost: Millions of dollars, shared between facility operator and utility

Reliability: Very high once complete, based on decades of proven design

Scalability: Limited by utility's willingness and ability to invest in your area

Best for: Facilities in locations where utilities are actively expanding capacity

Option 2: On-Site Generation

Approach: Install natural gas generators, renewable energy, or energy storage to supplement utility power.

Timeline: 1-2 years for design and deployment

Cost: High capital cost for generation equipment, ongoing fuel costs

Reliability: Dependent on fuel supply, maintenance, and redundancy design

Scalability: Limited by available space and environmental constraints

Best for: Facilities that can integrate renewable energy or have reliable fuel supplies

Option 3: Computational Flexibility

Approach: Design workloads to be flexible about timing and location. Shift computation to facilities with available power.

Timeline: Months to years (software and architecture changes)

Cost: Engineering investment, potential performance trade-offs

Reliability: Depends on having multiple facility options

Scalability: Good for geographically distributed operators

Best for: Cloud platforms and large operators with multiple facilities

Option 4: HTS Power Delivery

Approach: Deploy HTS cables and systems to increase power density in existing infrastructure.

Timeline: 3-5 years (current state, will improve)

Cost: Very high for first deployments, declining as technology matures

Reliability: Maturing, but not yet battle-tested at scale

Scalability: Excellent once supply chains and expertise scale

Best for: Well-capitalized organizations, new facility builds, high-constraint locations

What Success Looks Like: Performance Metrics for HTS Deployment

If Microsoft and other organizations do deploy HTS at scale, how would you know whether it actually worked?

Several key metrics would demonstrate success:

Transmission Loss Reduction

Target: Reduce power transmission losses from 150-200 kW down to 5-15 kW for three-megawatt transmission. If achieved, this represents 90%+ reduction in resistive heating.

Measurement: Direct comparison of electrical losses (watts entering the system vs. watts delivered after transmission) under controlled conditions.

Cooling Load Reduction

Target: Reduce cooling requirements by 10-20% through elimination of transmission heat losses.

Measurement: Compare total facility cooling load and cooling energy consumption before and after HTS deployment.

Power Density Improvement

Target: Increase available power capacity in existing infrastructure by 15-30% without expansion.

Measurement: Maximum safe sustained power delivery through existing electrical infrastructure, measured before and after HTS deployment.

Operational Reliability

Target: Achieve 99.99%+ availability (52 minutes or less of unplanned downtime per year).

Measurement: Track planned and unplanned downtime, failures, and performance degradation in HTS systems compared to conventional systems.

Cost Competitiveness

Target: Achieve total cost of ownership (capital + operating) comparable to or better than conventional alternatives when accounting for all factors.

Measurement: Complete lifecycle cost analysis including equipment, installation, maintenance, cooling, and electricity.

If HTS deployments hit these targets, the technology becomes a legitimate option for future data center builds and upgrades.

The Future of Data Center Power Delivery

Let's think beyond HTS for a moment. What does the long-term trajectory of data center power systems look like?

Three major trends are converging: higher computational density (especially AI), greater sustainability focus, and technological innovation in power transmission.

Traditional copper and aluminum cables probably won't disappear. They work too well for too many applications. But in new facility designs and high-constraint locations, HTS and other advanced technologies will likely become standard.

Microsoft's bet on HTS is partly a bet on the company's own future needs. As AI workloads grow and become more power-hungry, the company needs increasingly dense power delivery. HTS could enable deployments that would otherwise be constrained.

But it's also a broader bet on technology trajectory. Superconductor technology is improving. Manufacturing is scaling. Costs are dropping. The physics works beautifully.

At some point, probably in the 2030s, HTS will transition from "interesting experimental technology" to "industry standard for high-density applications."

Microsoft is trying to be ahead of that curve. So is Veir. And so are utility companies, renewable energy operators, and other organizations recognizing the potential.

The historical pattern of infrastructure technology adoption suggests that HTS will follow an S-curve trajectory: slow initial adoption, then rapid growth as costs drop and supply chains scale, eventually reaching saturation as the technology matures.

We're currently at the inflection point, moving from laboratory and pilot demonstrations toward initial commercial deployments.

The question isn't whether HTS will eventually become standard. The physics guarantees it will. The question is how fast the transition happens and who captures the first-mover advantages.

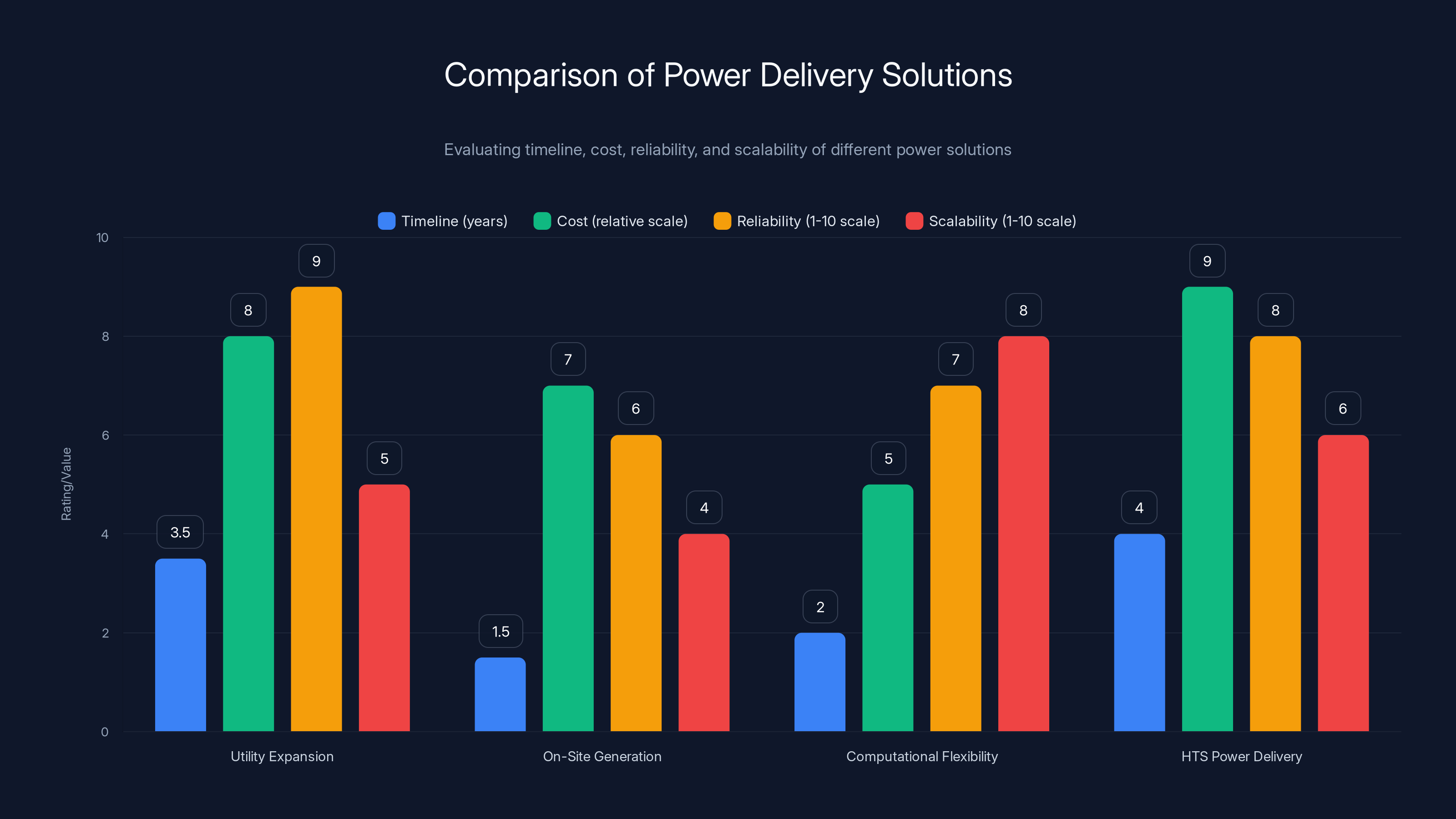

Utility expansion offers high reliability but at a high cost and long timeline. HTS power delivery is promising but currently expensive. Estimated data.

Key Obstacles Preventing Immediate Adoption

Despite the enormous potential, HTS faces real obstacles that will prevent widespread adoption for at least 3-5 more years.

Cost: HTS systems remain 3-10 times more expensive than conventional alternatives. Until costs drop closer to parity, adoption will be limited to organizations with strong economic incentives.

Maturity: HTS is still in development and early commercialization. The technology is proven in concept but not battle-tested at scale in production environments.

Supply: Manufacturing capacity is limited. Scaling production to meet broad demand requires significant capital investment that companies are making but will take years to complete.

Expertise: Operating HTS systems requires different knowledge and skills than conventional power systems. Training programs, certification standards, and experienced technicians are still developing.

Integration: Deploying HTS into existing facility designs requires rethinking electrical architecture, cooling systems, and control systems. Integration work is non-trivial.

Risk: Organizations deploying HTS now are taking on technology risk. Equipment might not perform as expected. Supply might be interrupted. Operating experience might reveal unforeseen challenges.

For hyperscalers like Microsoft, that risk is manageable. The potential payoff justifies the investment. For smaller operators, the risk-reward calculation is less favorable.

What This Means for Data Center Operators and the Cloud Industry

If you operate data centers or use cloud infrastructure, you might be wondering: does this actually matter to me?

In the medium term (next 5 years), probably not directly. HTS deployments will remain limited to leading hyperscalers and specialized applications. Cloud services from major providers will continue using conventional infrastructure.

In the longer term (5-15 years), HTS technology could reduce the capital costs and operational costs of data center infrastructure, leading to lower cloud service prices and more efficient facilities.

But there's a more important implication: power availability and power efficiency are becoming critical constraints for computational capacity.

If you're planning to deploy large-scale AI workloads, you need to think about power delivery, not just compute and storage. Your bottleneck might be power availability, not rack space or cooling.

Microsoft's public statements about power constraints are essentially a warning: if you're running AI workloads that require enormous GPU capacity, you need to plan for power requirements from the start.

Technology like HTS might solve that problem, but only if it's deployed proactively as part of facility design. Retrofitting power delivery to existing facilities is much harder than designing for it from the beginning.

Industry Momentum and Competitive Positioning

Microsoft isn't the only organization betting on superconductor technology. Several utility companies and infrastructure operators are also investing in HTS.

The Department of Energy has funded HTS research. Electricity grid operators in the U.S. and Europe are exploring HTS for transmission line applications. Private companies are building commercial products.

This broad industry momentum suggests that HTS will eventually become a standard technology for power delivery, even if adoption is slower than optimistic projections suggest.

From a competitive perspective, early adopters of HTS might gain advantages:

- Lower operational costs from reduced cooling and transmission losses

- Higher power density enabling more computational capacity in constrained locations

- Sustainability advantages from improved energy efficiency

- Scalability options for handling continued growth in power-hungry workloads

For a company like Microsoft competing with Amazon and Google, even incremental advantages matter. If HTS enables 10-15% cost reductions in power delivery and cooling, that translates to hundreds of millions of dollars in cost advantage across a global data center footprint.

That's not a reason to be excited about superconductor physics. That's a reason to be intensely focused on deploying the technology as quickly as possible.

Lessons from Past Infrastructure Technology Adoptions

Historically, major infrastructure technologies follow predictable adoption patterns. Looking at how previous power delivery innovations got adopted might tell us something about HTS trajectory.

When solid-state electronics started replacing vacuum tubes, the transition took 15-20 years. Early adopters had advantages, but skeptics weren't wrong to be cautious. Early solid-state equipment was expensive and fragile.

When fiber optic cables started replacing copper in telecommunications, the adoption curve was similarly slow initially, then rapid once costs dropped and reliability improved. Companies that invested early in fiber infrastructure gained enormous advantages.

The commonalities:

- Physics was never the limiting factor. The technologies worked in principle from the beginning.

- Cost and supply were the real constraints. Early adoption required either exceptional need (Microsoft's power constraint) or exceptional capital availability.

- Killer applications drove adoption. Fiber optics took off because telecommunications demand kept growing and fiber was the only way to meet that demand cost-effectively.

- Skepticism was justified early on. The technologies did have real limitations and risks that early critics correctly identified.

- Eventually, economic advantage became undeniable. Once costs dropped enough, the business case became obvious, and adoption accelerated.

HTS is likely to follow the same pattern. We're currently in the phase where the physics works, but costs are high and adoption is limited to organizations with strong economic drivers.

In 5-10 years, if costs drop and supply scales, adoption will accelerate. In 15-20 years, HTS might be standard for new infrastructure.

The Bottom Line: Hype Versus Reality

Let's be honest about what Microsoft's HTS announcement actually represents.

It's not a revolution that's happening tomorrow. It's not even a revolution that's happening next year.

It's a company placing strategic bets on technology that might become important 5-10 years from now, while honestly acknowledging that substantial obstacles remain.

Microsoft isn't claiming that HTS will solve all data center power problems. The company is saying it's interesting and worth investigating further.

That's actually more credible than some of the hype surrounding other technologies.

The physics is solid. Superconductors genuinely do eliminate resistive heating. Liquid nitrogen cooling is genuinely practical. Dense power delivery is genuinely valuable.

But engineering takes time. Supply chains take time. Cost reduction takes time. Adoption takes time.

Expect first real-world deployments in 2027-2028. Expect broader adoption by 2032-2035. Expect HTS to be standard for new high-density facilities by 2040.

That's not imminent. But it's also not impossible or improbable.

And for organizations like Microsoft that need to solve power delivery challenges right now, investigating HTS isn't excessive caution or hype-driven thinking. It's prudent long-term planning.

FAQ

What exactly are high-temperature superconductors and how do they work?

High-temperature superconductors are materials that exhibit zero electrical resistance when cooled below a critical temperature, typically around 77 Kelvin (the boiling point of liquid nitrogen). When cooled, electrons in the material form paired states called Cooper pairs, allowing them to flow without colliding with the atomic lattice and generating no heat. This is fundamentally different from normal conductors like copper, which always have some resistance and generate heat according to Joule's law.

How much power loss can HTS cables actually eliminate compared to copper cables?

For a three-megawatt transmission, traditional copper or aluminum cables would lose approximately 150-200 kilowatts as resistive heat. HTS cables can transmit the same power with losses of only 5-15 kilowatts, representing a 90-95% reduction in transmission losses. This dramatic improvement comes from zero electrical resistance in the superconducting state, compared to the inherent resistance of conventional conductors.

Why would Microsoft invest in HTS technology if it's not ready for deployment yet?

Microsoft is investing in HTS because the company faces growing power constraints from AI workload deployment, and conventional utility infrastructure expansion can't keep pace. By investing now, Microsoft gains several advantages: potential first-mover benefits if HTS matures faster than expected, strategic optionality for handling extreme power density demands, and positioning as a technology innovator. The company is essentially hedging against the risk that power availability becomes a major constraint for AI deployment.

What are the main obstacles preventing HTS adoption in data centers right now?

The primary obstacles are: high cost (HTS systems are currently 3-10 times more expensive than copper alternatives), limited manufacturing capacity and supply, immature technology (not yet battle-tested in production environments at scale), shortage of trained technicians and operators, integration complexity, and genuine risk for early adopters. While the physics works beautifully, the engineering, economics, and logistics of scaling HTS deployment remain challenging.

When will HTS cables actually be deployed in production data centers?

Veir, the company developing HTS systems, targets commercialization in 2026, meaning products should be available for purchase by that date. However, Veir's commercialization will likely involve limited production and beta customers. Microsoft's actual deployment in production facilities could realistically occur in 2027-2028, with broader industry adoption potentially following in the 2030s. Complete transformation of data center power architecture using HTS might not occur until 2035 or later.

How does HTS cooling with liquid nitrogen compare to traditional air cooling in terms of complexity and cost?

Liquid nitrogen cooling is more complex than air cooling but more practical than liquid helium cooling used in earlier superconductor applications. The system requires cryogenic pumps, insulated piping, temperature monitoring, and failover capability. Operating and maintaining HTS cooling systems requires specialized training and expertise. While cooling costs are lower (nitrogen is abundant and cheap), the infrastructure cost is higher, resulting in complex trade-offs between capital and operational expenses.

Could HTS technology completely replace copper cables in data centers?

Unlikely in the near term. Copper cables are proven, reliable, inexpensive, and require no special cooling infrastructure. HTS will likely become standard for specific high-density applications and new facility designs, but conventional conductors will remain the default for many applications where their lower cost and simplicity justify the higher transmission losses. The optimal approach will likely involve hybrid systems using both technologies where each is most appropriate.

What happens if HTS cooling fails during operation?

If cooling fails and the superconductor warms above its critical temperature, it instantly loses superconductivity and switches to normal resistive behavior, immediately generating heat. This would be detected by temperature sensors, triggering alarms and potentially automatic load shedding. Well-designed HTS systems include redundant cooling, monitoring, and failover capability, but compared to simple copper cables, HTS systems have more failure modes and require more sophisticated operational management.

How does HTS technology relate to Microsoft's AI infrastructure expansion plans?

AI workloads require enormous amounts of power, especially for GPU-heavy training and inference. Microsoft's ambitious AI deployment plans have revealed that power availability is becoming a bottleneck in many locations, more constraining than physical space or cooling capacity. HTS technology enables denser power delivery without waiting for years-long utility infrastructure upgrades, potentially unlocking deployment capacity that would otherwise be constrained by available electrical power from the grid.

Will HTS technology reduce cloud computing costs for end users?

Potentially, but not immediately. In the medium term (next 5 years), HTS will remain limited to hyperscaler deployments and specialized applications. Broader impact on cloud pricing would only emerge in the longer term (5-15+ years) as HTS costs drop, manufacturing scales, and the technology becomes standard. When that transition occurs, reduced data center capital and operational costs could translate to lower cloud service pricing, but that's a medium-to-long-term effect rather than immediate benefit.

Key Takeaways

-

HTS technology has genuine potential: The physics works beautifully, transmission losses can be reduced 90-95%, and power density gains are significant.

-

Cost and supply remain major obstacles: HTS systems are still 3-10 times more expensive than copper alternatives, manufacturing capacity is limited, and expertise is scarce.

-

Microsoft's investment is strategically sound: The company faces real power constraints from AI deployment and has the capital and planning horizon to invest in emerging infrastructure technologies.

-

Realistic timeline extends beyond 2030: Expect first production deployments around 2027-2028, with broader adoption gradually following over the next 10-15 years.

-

HTS is part of a broader solution: Multiple complementary approaches (renewable energy, cooling technology, computational flexibility, infrastructure expansion) will work together to address power delivery challenges.

-

Early adoption carries meaningful risk: Organizations deploying HTS now are accepting technology risk, supply chain risk, and operational uncertainty. The economic case for early adoption only works for well-capitalized companies with strong power constraints.

-

Long-term trajectory is clear: Superconductor technology will eventually become standard for high-density power delivery, but the path to that future requires solving substantial engineering, economic, and logistical challenges.

Related Articles

- Microsoft's Superconducting Data Centers: The Future of AI Infrastructure [2025]

- EU Data Centers & AI Readiness: The Infrastructure Crisis [2025]

- New York's Data Center Moratorium: What the 3-Year Pause Means [2025]

- Data Center Services in 2025: How Complexity Is Reshaping Infrastructure [2025]

- SpaceX's Million Satellite Data Centers: The Future of Cloud Computing [2025]

- Saudi Arabia's The Line Transforms into AI Data Centers [2025]

![Microsoft's High-Temperature Superconductors for Data Centers [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/microsoft-s-high-temperature-superconductors-for-data-center/image-1-1771177110031.png)