The Artemis 2 Launch Delay: What Happened and Why It Matters

In early February 2025, NASA experienced a setback that delayed one of humanity's most ambitious missions back to the Moon. The Space Launch System (SLS), already positioned on the launch pad at Kennedy Space Center in Florida, encountered a persistent liquid hydrogen leak during critical pre-launch testing. This wasn't a catastrophic failure or a fundamental design flaw, but it was serious enough that NASA had no choice but to postpone the Artemis 2 mission's launch window from February 6 to March 2025. According to NASA's official blog, the decision was made to ensure the safety and success of the mission.

For anyone following the Artemis program, this news might feel like déjà vu. The original Artemis 1 mission faced similar hydrogen leak issues, and the entire Artemis program has been defined by technical hurdles, schedule slips, and the constant challenge of preparing the most powerful rocket ever built for human spaceflight. But here's what makes this delay significant: it reveals something important about how NASA actually works, and why these apparently frustrating delays are actually evidence of a system working correctly, as explained by CNN.

The Artemis program represents humanity's return to lunar exploration after a 50-year gap. Artemis 2 will carry four astronauts around the Moon (but not landing), making it the first crewed lunar mission since Apollo 17 in 1972. That's not just a technical milestone. It's the foundation for everything that comes after, including the eventual lunar landing mission (Artemis 3) and the establishment of sustained human presence on the Moon, as detailed by The Planetary Society.

Understanding what went wrong, why it happened, and what NASA is doing about it gives you insight into both the complexity of modern spaceflight and the institutional culture that keeps astronauts alive. This isn't boring bureaucracy. This is the difference between success and catastrophe.

Why the Leak Matters More Than You Might Think

A liquid hydrogen leak in isolation doesn't sound like the end of the world. Hydrogen is used in countless industrial applications. But on a rocket, hydrogen represents one of the most energetic chemical fuels known. When combined with oxygen, it produces the thrust that lifts 17 million pounds off the ground. That's about 10 times the weight of the Statue of Liberty. The margin for error on something that powerful is measured in fractions of a percent, as noted by NASA's mission overview.

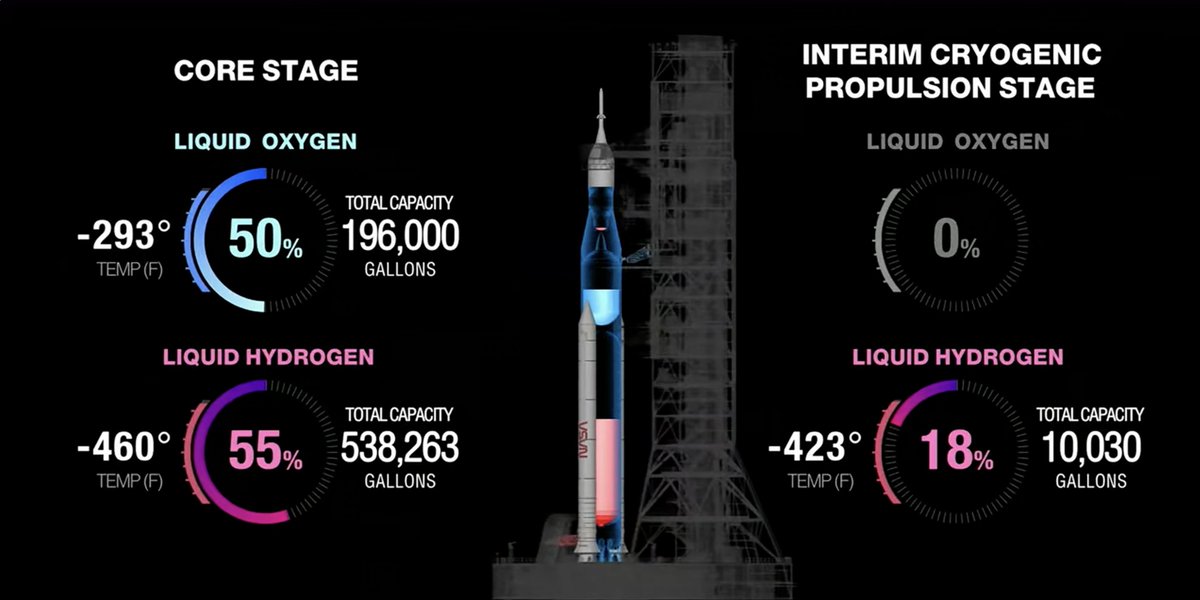

The leak itself occurred in the Space Launch System's core stage, the massive central tank that holds both liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen. During the wet dress rehearsal on February 3, engineers loaded the rocket with propellants to simulate exactly what would happen on launch day. This is where the hydrogen leak first appeared. The problem: every time they tried to solve it, they fixed one issue only to reveal another problem in the system.

NASA's Administrator Jared Isaacman later explained that the agency had "fully anticipated encountering challenges" during the rehearsal. This isn't false confidence or a salvage attempt. It's the actual philosophy behind why NASA conducts wet dress rehearsals in the first place. The test exists to surface problems before a crewed launch. Better to find issues with nobody aboard the spacecraft than to discover them at 100 kilometers altitude, as highlighted by NASA's blog.

Understanding the Wet Dress Rehearsal Process

A wet dress rehearsal isn't just another test on the checklist. It's the most realistic simulation possible short of an actual launch. Think of it like a full rehearsal of a theater production where the actors are actually on stage, the sets are real, and the lighting is live. Everything that will happen on launch day happens during the rehearsal, except the engines don't actually ignite and release the vehicle from the launch pad, as described by Mashable.

During Artemis 2's rehearsal, engineers began loading liquid hydrogen into the core stage's hydrogen tank. Liquid hydrogen requires extreme precision to handle. It exists at minus 253 degrees Celsius, colder than the coldest naturally occurring temperature on Earth. At that temperature, metals become brittle, seals behave unpredictably, and even tiny flaws can cause leaks.

The process of loading began in the early morning hours of February 3. Engineers connected the umbilical lines, opened the valves, and began flowing hydrogen into the massive tank. Everything proceeded normally until the leak rate began climbing. The term "leak rate" describes how fast hydrogen is escaping. During normal operations, some minimal leakage is expected and acceptable. But Artemis 2's leak rate exceeded acceptable limits, as reported by ABC News.

NASA engineers spent hours troubleshooting. They disconnected and reconnected umbilical lines. They inspected seals and valve positions. They ran diagnostics on sensors to make sure the leak wasn't just an instrument malfunction. Gradually, they brought the leak under control and managed to fill all the rocket's tanks. This is significant because it proved the tanks could be filled, which is what would need to happen on launch day.

But here's where the real issue emerged. As the countdown sequence began, the ground launch sequencer (the computer system that controls the automated countdown) was monitoring the hydrogen leak rate in real time. With approximately five minutes remaining in the countdown, that rate spiked again. The automated system did exactly what it was programmed to do: it stopped the countdown. No human operator overrode it. No one made a judgment call to push forward. The system worked, as detailed by International Business Times.

The Technical Problems NASA Identified

Once the countdown stopped, NASA had clear data about what needed fixing. But the hydrogen leak wasn't the only issue that emerged. During the wet dress rehearsal, engineers and software specialists identified three separate problem areas that would need resolution before the next attempt, as outlined by ProPublica.

First, there's the hydrogen leak itself. The source needs to be identified with certainty. Is it a faulty seal on one of the umbilicals? Is it a valve that's not closing completely? Is it a crack or defect in the tank itself? NASA's engineering teams needed to examine the system with instruments, conduct pressure tests, potentially replace components, and understand the root cause. Just fixing the symptom wouldn't be sufficient. You need to understand what caused the symptom to prevent it from recurring.

Second, NASA identified that the cold weather significantly affected equipment performance in ways that weren't expected. Specifically, the Orion crew module's hatch pressurization process took longer than planned. The crew module is where astronauts will sit during launch and return. Its hatch must pressurize before launch. If this process takes longer during actual conditions than planned, it could consume time budgeted for other critical activities. The pressurization delay suggested that cryogenic temperatures were affecting seals, mechanisms, or both in ways that need to be understood and corrected.

Third, and perhaps most frustrating for ground teams, the audio communication system for launch control dropped multiple times during the rehearsal. This isn't a rocket science problem in the traditional sense. It's an infrastructure problem. But it's critical. Launch controllers need clear communication. Garbled messages or dropped lines could delay crucial commands or cause miscommunications about vehicle status. Every communication dropout during the rehearsal was a symptom that something in the system needed improvement.

These three issues represent different types of challenges. The hydrogen leak is a hardware and systems integration problem. The hatch pressurization is an environmental response problem. The communications issue is partly hardware, partly software, possibly partly environmental interference. But they share one thing: they all need to be solved before launch, and solving them requires understanding root causes, not just applying quick fixes.

Why NASA Chose March: The Calendar and Launch Windows

NASA didn't randomly pick March for the next launch attempt. Launch windows for lunar missions are determined by orbital mechanics. The Moon's position relative to Earth changes throughout the month. Depending on the specific lunar destination and the mission objectives, only certain dates provide the right geometry for spacecraft to reach their targets efficiently, as explained by NASA's updates.

Artemis 2 targets a lunar flyby trajectory that will take the Orion spacecraft around the Moon and back. This requires a specific alignment between Earth and Moon. Miss the February window, and the next viable window opens in March. If Artemis 2 misses March, the next opportunity might be weeks away, depending on the mission profile.

The shift from a February 6 opening to a March opening also gives NASA something crucial: time. Time to investigate the hydrogen leak, remove the rocket from the pad if necessary for repairs, conduct maintenance, run additional testing, and restack everything for another wet dress rehearsal attempt. This isn't just scheduling convenience. It's a recognition that rushing through a repair without thorough validation is exactly how space disasters happen.

The Historical Context: Why This Delay Echoes Previous Challenges

Artemis 2 isn't the first vehicle in the SLS program to encounter hydrogen leaks. Artemis 1 faced similar issues during its pre-launch testing phase. The first SLS launch attempt in August 2021 was scrubbed due to a hydrogen leak in the core stage quick disconnect. Subsequent launch attempts were postponed for similar hardware issues. When Artemis 1 finally launched in November 2022, it was after more than a year of troubleshooting, as reported by NASA.

This pattern might suggest that NASA is struggling with a fundamental design flaw. Some critics have argued exactly that. But understanding these delays requires context about what the Space Launch System actually is. The SLS isn't a commercial rocket developed by a single company with streamlined supply chains and integration procedures. It's a government-developed vehicle built from hundreds of contractors, incorporating hardware originally designed for the Space Shuttle program, engines developed decades earlier, and new architecture designed specifically for deep space exploration.

The SLS core stage engines are Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSMEs), originally developed in the 1970s and 1980s. These are extraordinarily reliable and powerful, but they're also complex pieces of hardware with intricate plumbing for propellant flow. The core stage itself is new architecture, but it incorporates interface points and design principles influenced by decades of spaceflight heritage. This creates a complex integration challenge.

When you're designing a rocket from scratch, like Space X did with Falcon 9, you can make choices optimized for modern manufacturing, testing, and integration. When you're integrating heritage hardware with new systems, you're inheriting challenges from every previous program. This doesn't excuse delays. It explains them.

What Happens Between Now and the Next Launch Attempt

NASA's plan between now and the March launch window involves several parallel work streams. First, the SLS will likely be rolled back from the launch pad to the Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy Space Center. This allows technicians to access the core stage without the time pressure and operational complexity of working at the launch pad, as outlined by NASA's blog.

Once in the assembly building, engineers will conduct detailed inspections of the hydrogen umbilicals, valves, seals, and tank structure. They'll likely use specialized equipment like leak detectors and pressure testing apparatus to confirm the exact source of the leak. Depending on what they find, repairs might range from simple seal replacement to more extensive rework.

Simultaneously, NASA's Thermal Analysis team will examine why the hatch pressurization process slowed in the cold cryogenic environment. They may need to modify the pressurization sequence, adjust valve settings, or even redesign certain components to function properly at those temperatures. This work involves computer modeling, bench testing of components in cryogenic conditions, and validation testing.

The communications team will troubleshoot the audio dropouts. This might involve replacing equipment, rerouting cables, or modifying software. The work is less glamorous than rocket engineering, but it's equally important.

After these repairs and modifications are complete, NASA will conduct a second wet dress rehearsal. This rehearsal will validate that the hydrogen leak has been resolved, the hatch pressurization works correctly, and communications systems function reliably. Only after a successful second rehearsal will NASA set a specific launch date.

The Bigger Picture: Artemis 2 in the Context of the Program

Artemis 2 represents a specific mission within a longer-term program. The Artemis program aims to establish human presence on the Moon, conduct scientific research, and create the infrastructure for sustained lunar operations. Artemis 2, the crewed lunar flyby, is fundamentally important for several reasons.

First, it validates that the SLS and Orion systems work together in a crewed environment. Uncrewed test flights (like Artemis 1) provide valuable data, but human spaceflight adds complexity. Orion needs to support four astronauts in a closed-loop life support system for about 10 days. That's a different engineering challenge than flying uncrewed.

Second, Artemis 2 serves as a high-fidelity validation test for systems that will be used in Artemis 3, the actual lunar landing mission. If something fails on Artemis 2, NASA wants to know about it and fix it before astronauts attempt to land on the Moon. The risk tolerance for a lunar landing is much lower than for a flyby.

Third, Artemis 2 demonstrates to the international spaceflight community, Congress, and the public that NASA can execute a complex crewed deep-space mission. The optics matter because the Artemis program requires sustained funding, political support, and public interest. Launching successfully matters. Launching recklessly and failing would be catastrophic for the entire program.

The Broader Implications for Spaceflight Culture and Safety

Here's what's interesting about NASA's response to the hydrogen leak. The agency didn't minimize the problem or suggest it was minor. It didn't push for a quick fix to maintain schedule. Instead, NASA's leadership acknowledged the issue, explained why it matters, and committed to fixing it comprehensively before the next launch attempt, as noted by NASA.

This approach reflects a specific organizational culture that developed over decades of spaceflight, including some of the most painful lessons in aviation and space history. The Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986 happened partly because engineers and managers chose to proceed with a launch despite known issues with O-ring seals in cold weather. The Challenger Commission's investigation revealed that organizational pressure to maintain the launch schedule had contributed to a decision-making environment where technical concerns were underweighted against schedule pressure.

That disaster informed NASA's current culture. Engineers have a voice. Technical readiness is not compromised for schedule. When a vehicle isn't ready, it doesn't fly. This doesn't mean NASA is immune from schedule pressure. It does mean there are institutional mechanisms designed to prevent schedule pressure from overriding safety judgment.

The hydrogen leak and the decision to delay Artemis 2 is an example of that culture in action. The leak was discovered during the designed-purpose test intended to discover such issues. The discovery triggered a thorough investigation and a commitment to fix the root cause, not just patch the symptom. The schedule slipped. But the mission stays safe.

Hydrogen as a Rocket Fuel: Why This Leak Matters Technically

Hydrogen's use as a rocket fuel isn't arbitrary. It provides specific advantages and challenges. Liquid hydrogen has one of the highest specific impulses of any chemical rocket propellant, meaning it produces the most thrust per unit of fuel weight. For a vehicle like the SLS, which needs to be powerful enough to accelerate a crewed spacecraft to the Moon, hydrogen's performance is essential, as explained by NASA.

But hydrogen is also incredibly difficult to handle. At minus 253 degrees Celsius, it's cold enough to make most materials become brittle. Seals that work fine at room temperature can fail catastrophically at cryogenic temperatures. Metals contract unevenly, creating microscopic gaps. Thermal stress on connectors can cause failures.

Moreover, hydrogen is extremely diffusive. It's the smallest element, and it can penetrate through materials that block larger molecules. Even a tiny seal that has a microscopic defect might allow hydrogen to escape. Detecting leaks requires sensitive instruments. Preventing leaks requires exceptional manufacturing standards and frequent inspection.

The SLS uses hydrogen because the engineering advantages outweigh the handling challenges. But it means that pre-launch testing has to account for cryogenic conditions, hydrogen's material interactions, and the need for extraordinary attention to detail. The leak discovered during Artemis 2's wet dress rehearsal wasn't evidence of poor design. It was evidence that the test was working as intended: revealing issues in conditions where they can be fixed rather than where they can't.

The Role of Automation in Launch Safety

One detail from the Artemis 2 countdown shutdown is worth highlighting: the ground launch sequencer automatically stopped the countdown when the hydrogen leak rate spiked. No human decision made it happen. The computer system detected the problem and executed its programmed response, as described by NASA.

This automated safety system exists for good reason. During a launch countdown, there's an enormous amount of data being processed. Temperature sensors, pressure sensors, flow rate sensors, position sensors, and hundreds of other instruments feed information to the ground launch sequencer. A human operator couldn't process all that information fast enough or reliably enough to make real-time decisions about safety.

By contrast, a computer system can monitor dozens of parameters simultaneously and execute pre-programmed safety responses in milliseconds. When the hydrogen leak rate exceeded a threshold, the sequencer did exactly what it was designed to do. This prevented engineers from inadvertently proceeding with an unsafe countdown.

The fact that this system worked as designed is significant. It suggests that the engineering team designed appropriate safety margins and thresholds. The system caught a problem that would have been harder to detect without those automated safeguards.

Looking Ahead: What Artemis 2 Success Would Mean

A successful Artemis 2 mission would represent several important milestones. First, it would validate the SLS and Orion architecture for crewed missions. Second, it would demonstrate that NASA can execute a complex deep-space mission with a crew. Third, it would provide experience and data that directly inform Artemis 3.

Artemis 3, planned for the mid-to-late 2020s, will attempt to land astronauts on the Moon near the lunar south pole. This is exponentially more complex than a lunar flyby. The lunar landing requires a descent vehicle, a crewed landing system, surface operations, and a return ascent. Every system needs to work. The stakes are as high as they get in spaceflight.

Artemis 2 serves as a crucial validation step. It's the last fully uncrewed dress rehearsal before going all-in on the landing attempt. A successful Artemis 2 flight increases confidence that Artemis 3 can succeed. Conversely, if Artemis 2 encountered catastrophic failures, that would force a fundamental rethinking of the approach.

The delay caused by the hydrogen leak is frustrating from a schedule perspective. But it's also the system working as designed. Engineers have time to understand the root cause, fix it comprehensively, and validate the fix before the next attempt. That's the right approach, even if it means delays.

Communication and Transparency: How NASA Handled the Announcement

NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman's statement about the delay was notably transparent. He didn't blame contractors, point fingers at specific teams, or suggest the problem was minor. Instead, he acknowledged that challenges during a wet dress rehearsal are expected, and that the entire purpose of conducting the rehearsal is to surface issues before flight, as noted by NASA.

This kind of communication matters because it sets expectations. The public and Congress needed to understand that the delay wasn't evidence of program failure. It was evidence that the testing program was working. Without that explanation, the delay might have been perceived as a negative reflection on NASA's competence.

Transparency also builds credibility. When things go wrong with space missions, transparency about root causes and remediation plans is more convincing than vague promises that everything is fine. NASA's detailed explanation of the hydrogen leak, the hatch pressurization issue, and the communication problem gave people real information about what happened and why.

This approach contrasts with spaceflight programs that treat problems as embarrassments to be minimized. The culture of transparency that NASA has developed makes the program stronger, not weaker.

The Supply Chain and Manufacturing Implications

The hydrogen leak also raises questions about manufacturing precision. Every connection, every seal, every component needs to be manufactured to exacting specifications. But there's a difference between knowing specifications exist and actually achieving them across thousands of parts, as discussed by NASA.

NASA works with hundreds of contractors and subcontractors, each manufacturing specific components. The Space Launch System's core stage involves integration of parts from companies spread across multiple states. Each component arrives with its own documentation and testing records. But integrating all these components into a functioning system requires careful assembly, testing, and validation.

The hydrogen leak discovered during the wet dress rehearsal might be traced to a single faulty seal manufactured by a subcontractor, or it might be the result of a subtle issue in how two components interface. Either way, the discovery highlights the importance of comprehensive testing, and the challenge of maintaining quality standards across a complex supply chain.

This is one reason why commercial spaceflight companies like Space X often prefer to design and build more components in-house. It reduces supply chain complexity. But NASA's approach involves significant contractor participation, which brings different trade-offs. Working with contractors provides expertise and distributes cost, but it also requires more complex integration and testing.

International and Commercial Context

While NASA manages the Artemis program, it's not operating in isolation. Other nations are developing lunar exploration capabilities. China has successfully landed rovers on the Moon. The European Space Agency, Japan, India, and other nations have lunar exploration programs. The private space industry is also developing lunar capabilities, as reported by NASA.

International interest in lunar exploration means that NASA's timeline matters not just for domestic reasons but for geopolitical reasons as well. The first nations to establish sustained presence on the Moon will gain strategic advantages in terms of scientific discovery, resource assessment, and positioning for deeper space exploration.

NASA's delays in the Artemis program are notable against this international backdrop. But they're also a reflection of the engineering reality that building something unprecedented safely takes time. The Artemis program is attempting something that hasn't been done in 50 years, with new vehicle systems that are more capable than the Apollo-era equivalents.

The Cost of Delays

Delay also has financial implications. Every day that NASA's teams are working to troubleshoot and repair Artemis 2 costs money. Engineers' salaries, facility costs, equipment costs, and overhead all accumulate. The delay from February to March represents weeks of additional costs.

For a program like Artemis, which operates under budget constraints and congressional scrutiny, schedule delays are never popular. They consume budget that was planned for other work. They push other projects into the future. They make it harder to justify continued funding.

But the alternative, launching an unsafe vehicle to stay on schedule, would be far more expensive. A launch failure would destroy the vehicle, potentially injure or kill crew, and probably end the Artemis program entirely. No schedule is worth that trade-off.

This is a fundamental principle of modern spaceflight: safety first, schedule second. It's a principle that took decades to establish and is constantly tested by real-world pressure to achieve missions and maintain budgets.

Lessons from the Hydrogen Leak

For the broader aerospace industry, the Artemis 2 hydrogen leak offers lessons about testing, design for manufacturability, and quality control. The wet dress rehearsal caught the issue. That's good. But preventing such issues in the first place is better.

The lesson isn't that NASA doesn't know how to handle hydrogen or that SLS is fundamentally flawed. The lesson is that systems this complex, incorporating heritage hardware and new architecture, tested in extreme conditions, will occasionally reveal issues that weren't obvious during earlier testing phases. The solution is rigorous testing followed by root cause analysis and comprehensive repair, not schedule-driven risk acceptance.

Timeline to March Launch

From the February 3 wet dress rehearsal to the March launch window represents approximately four weeks. This timeline is ambitious. NASA needs to complete investigations, source replacement parts if needed, conduct repairs, and conduct another wet dress rehearsal to validate fixes.

The schedule suggests that NASA has specific confidence that the hydrogen leak issue is traceable and repairable within this timeframe. If repairs take longer than anticipated, the launch window might slip to the next available opportunity. But NASA has committed to the March timeline, suggesting that engineering teams believe this is achievable.

FAQ

What is a wet dress rehearsal?

A wet dress rehearsal is a full simulation of a launch countdown using actual propellants. The spacecraft is loaded with liquid hydrogen, liquid oxygen, and other propellants, and the entire launch sequence is executed, including all automated safety checks and countdowns, except the engines don't actually ignite and the vehicle doesn't release from the launch pad. It's the most realistic test possible before an actual launch.

Why is the hydrogen leak such a serious problem?

Liquid hydrogen is the fuel for the SLS core stage engines. A leak means propellant is escaping, which means either the tanks can't be filled to required levels or the leak represents a serious flaw in the vehicle's structural or systems integrity. More importantly, hydrogen leaks in a cryogenic environment can indicate problems with seals, connectors, or tank structure that could fail catastrophically during flight.

How does cold weather affect rocket components?

At cryogenic temperatures (minus 253 degrees Celsius for liquid hydrogen), metals become brittle, rubber seals lose flexibility, and thermal stress can cause materials to crack or fail. Components that work fine at room temperature may fail under cryogenic conditions. This is why NASA had to identify and fix the hatch pressurization issue that emerged only when the vehicle was exposed to these extreme temperatures during the wet dress rehearsal.

What happens if the March launch attempt also encounters problems?

If the March wet dress rehearsal reveals issues that aren't quickly fixable, NASA will skip that launch window and wait for the next available opportunity. Launch windows for lunar missions are determined by orbital mechanics and may be weeks or even months apart. NASA won't launch until the vehicle is ready, even if schedule pressure mounts.

Why does NASA use liquid hydrogen instead of other fuels?

Liquid hydrogen provides the highest specific impulse of common rocket propellants, meaning it delivers more thrust per unit of fuel weight. For a heavy-lift vehicle like the SLS that needs to accelerate a crewed spacecraft all the way to the Moon, hydrogen's performance advantages outweigh the engineering challenges of handling it.

How many people will be on Artemis 2?

Artemis 2 will carry four astronauts around the Moon but won't land on the lunar surface. The mission duration will be approximately 10 days. The next mission, Artemis 3, is planned to actually land astronauts on the Moon.

What does the hydrogen leak say about the SLS program's health?

The hydrogen leak, while concerning, is the kind of issue that the testing program is designed to catch. It's not evidence of fundamental design flaws. Rather, it's evidence that the wet dress rehearsal is working as intended. SLS is an extraordinarily complex vehicle integrating heritage hardware with new systems, and discovering issues during testing rather than during flight is the goal.

How often do launch delays happen in spaceflight?

Launch delays are routine in spaceflight, particularly for complex vehicles like the SLS. Space X delays Falcon Heavy missions. The Space Shuttle regularly experienced launch delays. Delays are so common that spaceflight programs build schedule margins specifically to absorb them. What matters is the reason for the delay and whether it's addressed properly.

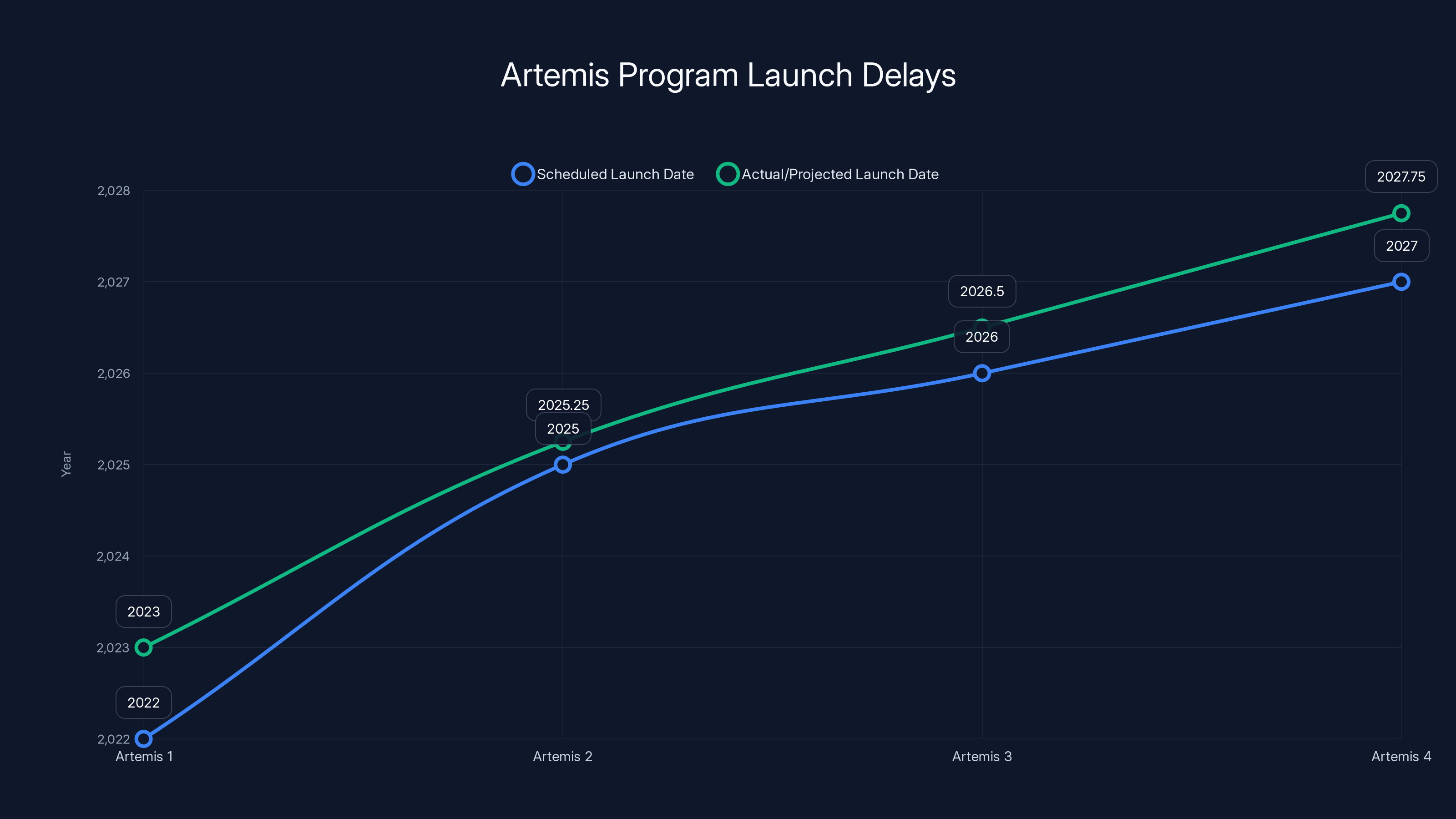

The Artemis program has faced several delays, with Artemis 2 experiencing a shift from February to March 2025 due to a hydrogen leak. Estimated data for future missions.

Conclusion

The delay of Artemis 2 from February to March 2025 isn't a failure of NASA's engineering or program management. It's evidence that the system is working as designed. A liquid hydrogen leak was discovered during the wet dress rehearsal, exactly the test designed to catch such issues. NASA responded by investigating the root cause, identifying related problems, and committing to a comprehensive fix before the next launch attempt.

This approach reflects decades of learning from spaceflight history, including painful lessons about the consequences of schedule pressure overriding engineering judgment. The hydrogen leak, the hatch pressurization issue, and the communication system problem are all being addressed methodically rather than quickly.

Artemis 2 represents a crucial step in humanity's return to the Moon. The mission will carry four astronauts on a lunar flyby, validating systems and approaches that will be used in future lunar landings. Getting this mission right matters more than getting it on a specific schedule.

The March launch window represents NASA's target, but it's conditional on successful validation testing. If that testing reveals additional issues, the launch will slip further. That's not failure. That's how spaceflight programs maintain safety while pursuing ambitious goals.

For anyone following the Artemis program, the hydrogen leak is a reminder that spaceflight is hard. The SLS is the most powerful rocket ever built. Orion is the most capable crew capsule ever developed. The systems are incredibly complex. Problems will emerge. The difference between successful spaceflight programs and failed ones is how those problems are handled. NASA's response to the Artemis 2 issues shows a program that prioritizes safety, transparency, and getting it right over checking boxes on a schedule.

The Moon has waited 50 years for humans to return. It can wait a few more weeks while NASA does the engineering right.

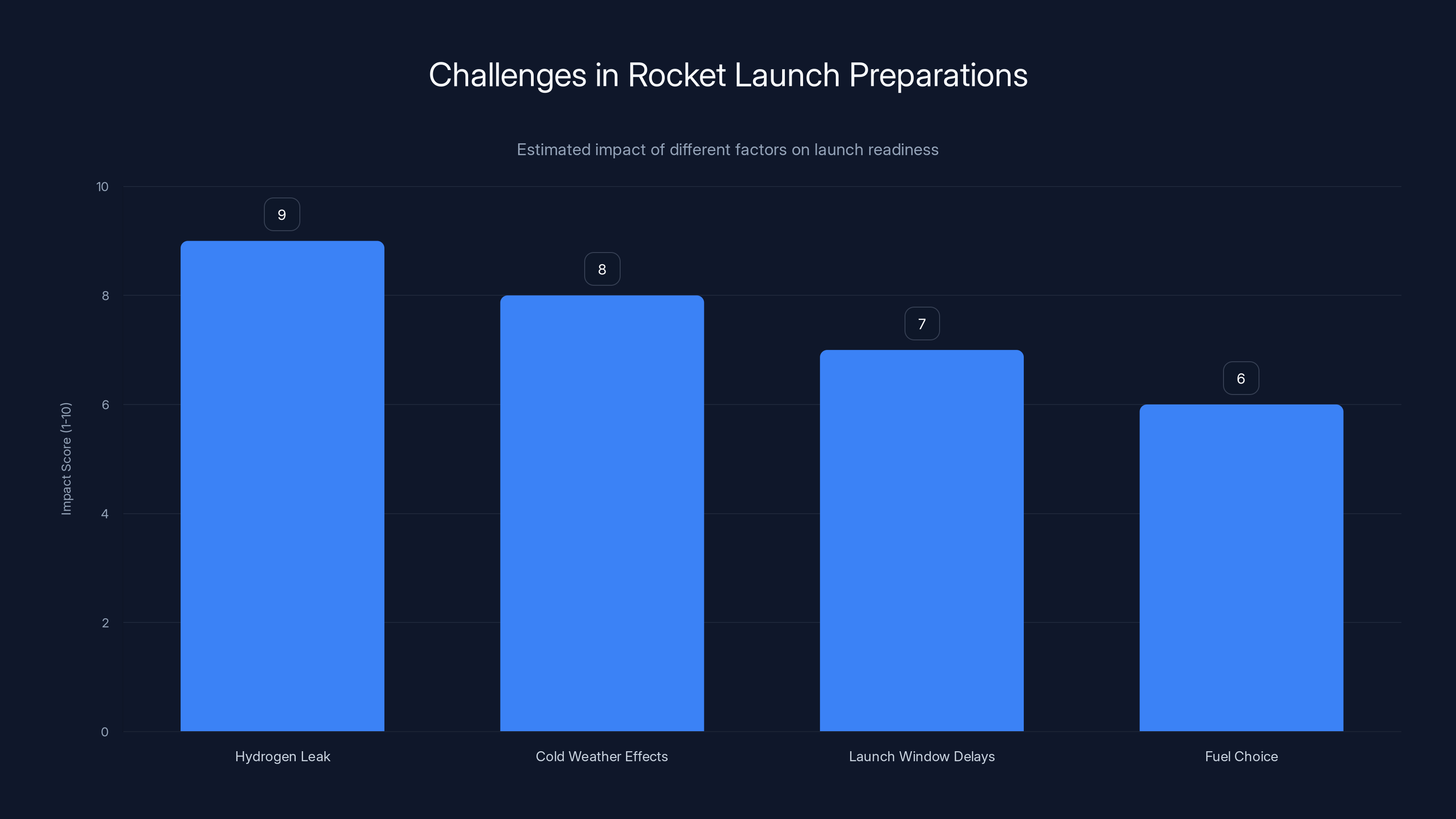

Hydrogen leaks and cold weather effects are the most critical challenges, scoring 9 and 8 respectively, in rocket launch preparations. Estimated data.

Key Takeaways

- NASA delayed Artemis 2 from February to March 2025 after discovering a liquid hydrogen leak during the wet dress rehearsal at Kennedy Space Center

- The leak emerged during the final stages of the countdown sequence when automated systems correctly halted the test, proving safety mechanisms worked as designed

- NASA identified three separate issues requiring fixes: the hydrogen leak itself, slower-than-expected hatch pressurization in cryogenic conditions, and communication system dropouts

- Wet dress rehearsals exist specifically to uncover problems in realistic launch conditions before crewed flight, making the delay an example of the testing system working correctly

- The March launch window was selected based on orbital mechanics requirements for lunar missions; if that window is missed, the next opportunity may be weeks away

Related Articles

- Artemis II Wet Dress Rehearsal: NASA's Final Test Before Moon Launch [2025]

- Artemis II Launch Delayed by Cold Weather: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Artemis II: The Next Giant Leap to the Moon [2025]

- NASA's Crew-11 Early Return: What the Medical Concern Means [2025]

- Blue Origin Pauses Space Tourism for NASA Lunar Lander Development [2025]

- The Challenger Remove Before Flight Tags: A 40-Year Mystery [2025]

![NASA Artemis 2 Launch Delayed to March: What the Hydrogen Leak Means [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nasa-artemis-2-launch-delayed-to-march-what-the-hydrogen-lea/image-1-1770129841132.jpg)