NASA's Artemis II Hydrogen Leak Crisis: What Went Wrong and How NASA Plans to Fix It

There's something deeply unsettling about a rocket that can't hold its fuel. It sounds simple, almost comical. But when you're talking about the Space Launch System—a $23 billion rocket designed to send humans back to the Moon for the first time in over 50 years—a hydrogen leak isn't just a minor inconvenience. It's the kind of problem that can derail an entire mission, delay a national program, and force engineers back to the drawing board.

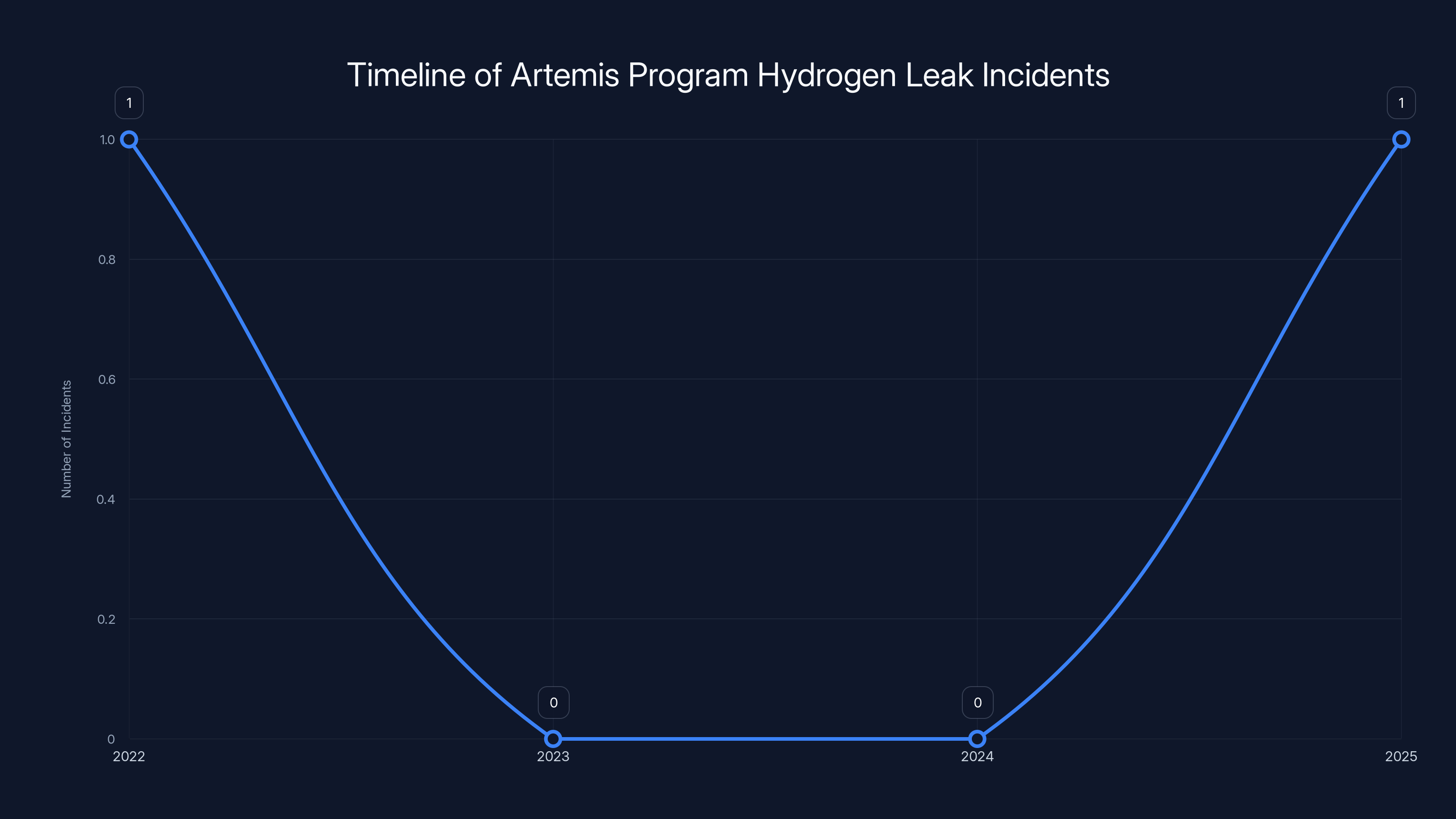

In February 2025, NASA's Artemis II mission faced exactly this scenario. During a Wet Dress Rehearsal (WDR), the practice countdown that tests every system before launch, technicians discovered hydrogen gas leaking from the connection points where fueling lines meet the Space Launch System's core stage. The leak cut the rehearsal short. NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman went public, promising fixes before the next countdown test. But this wasn't the first time the SLS had this problem.

The same hydrogen leak had plagued the Artemis I unmanned test flight in 2022, delaying the mission by months. Engineers thought they'd solved it three years ago. They didn't. So now, as NASA prepares Artemis II for launch and looks ahead to Artemis III's historic lunar landing mission, the agency faces a critical question: can they actually fix this, or will hydrogen leaks continue to haunt the SLS program?

This isn't just a technical story. It's about managing risk on the most expensive human spaceflight program ever built. It's about why rocket science is harder than it looks, even with billions in funding and three decades of engineering knowledge. And it's about what happens when the constraints of physics meet the realities of aerospace manufacturing.

The Hydrogen Leak Problem: Understanding the Technical Challenge

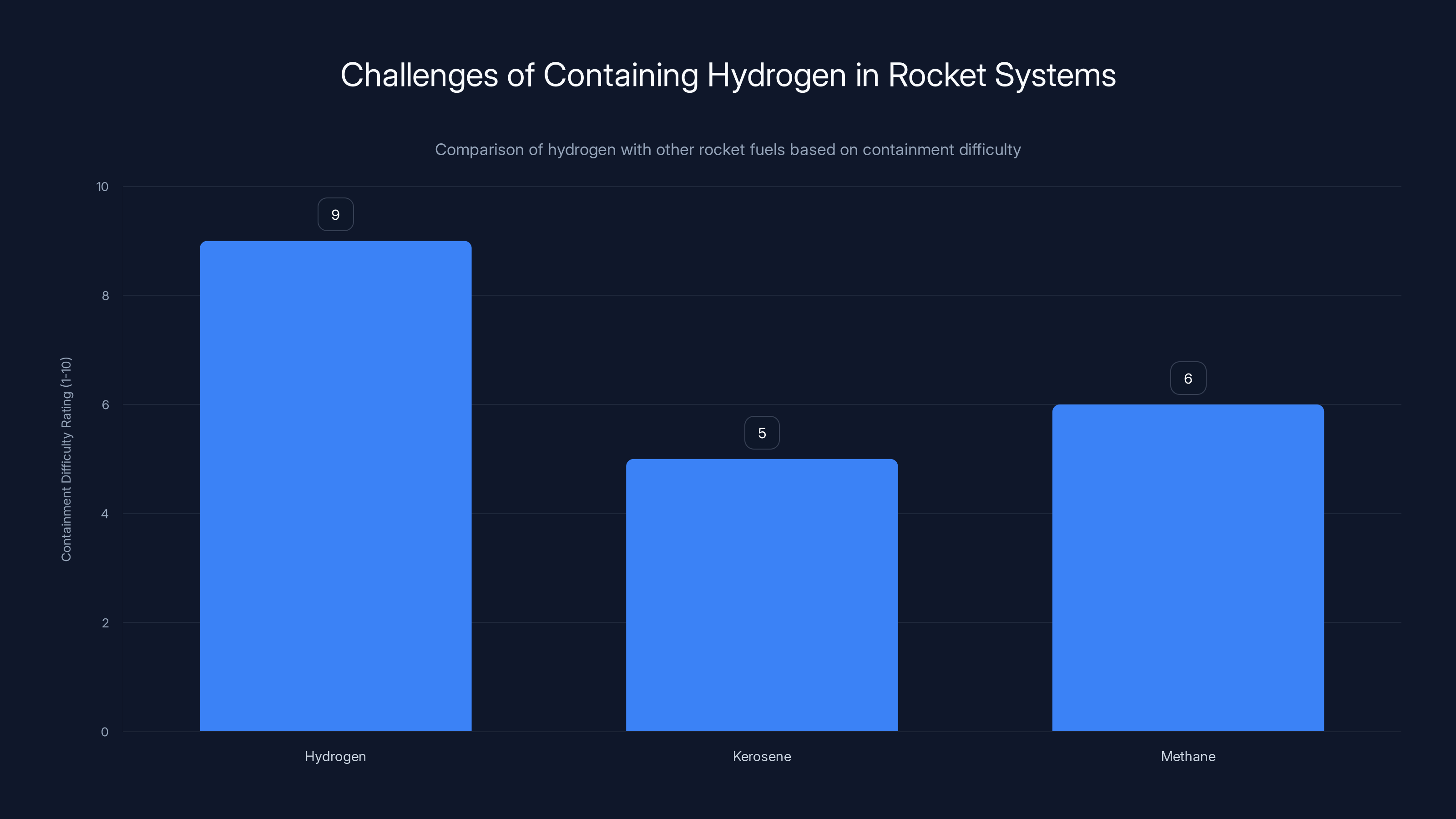

Hydrogen is the rocket engineer's paradox. It's the most powerful chemical fuel you can use—when burned with oxygen, it produces nothing but water vapor and incredible thermal energy. That's why every major launch vehicle, from the Space Shuttle to the Saturn V to modern Falcon 9 second stages, uses liquid hydrogen in their engines.

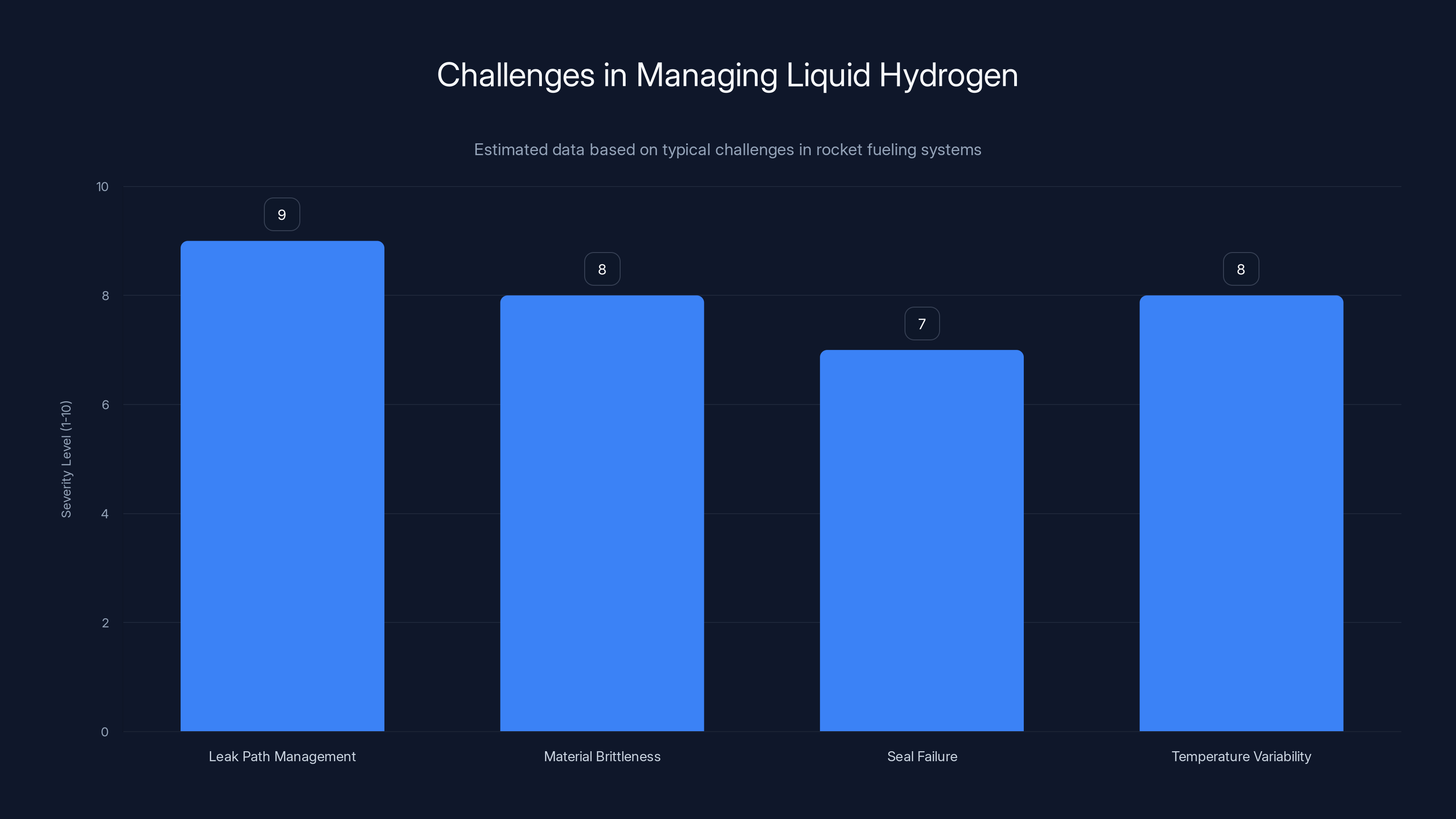

But hydrogen is also the most difficult fuel to manage on the ground. Here's why: molecular hydrogen is literally the smallest molecule in existence. Imagine trying to contain something so tiny that it can slip through gaps you can't even see. At the quantum level, hydrogen atoms behave differently than heavier molecules. They find paths through seals, past connections, and through materials in ways that seem almost intentional.

The other problem is temperature. Liquid hydrogen exists at minus 423 degrees Fahrenheit—that's minus 253 degrees Celsius. At this temperature, materials become brittle. Seals harden. Metals contract. The expansion and contraction rates of different materials create tiny gaps where hydrogen can escape. This is why hydrogen requires specially designed seals, lines, and equipment that simply don't exist for other fuels.

When engineers design a rocket fueling system, they're essentially engineering a battle against physics itself. Every connection point is a potential leak path. Every seal is a candidate for failure. Every temperature change is an opportunity for things to come apart.

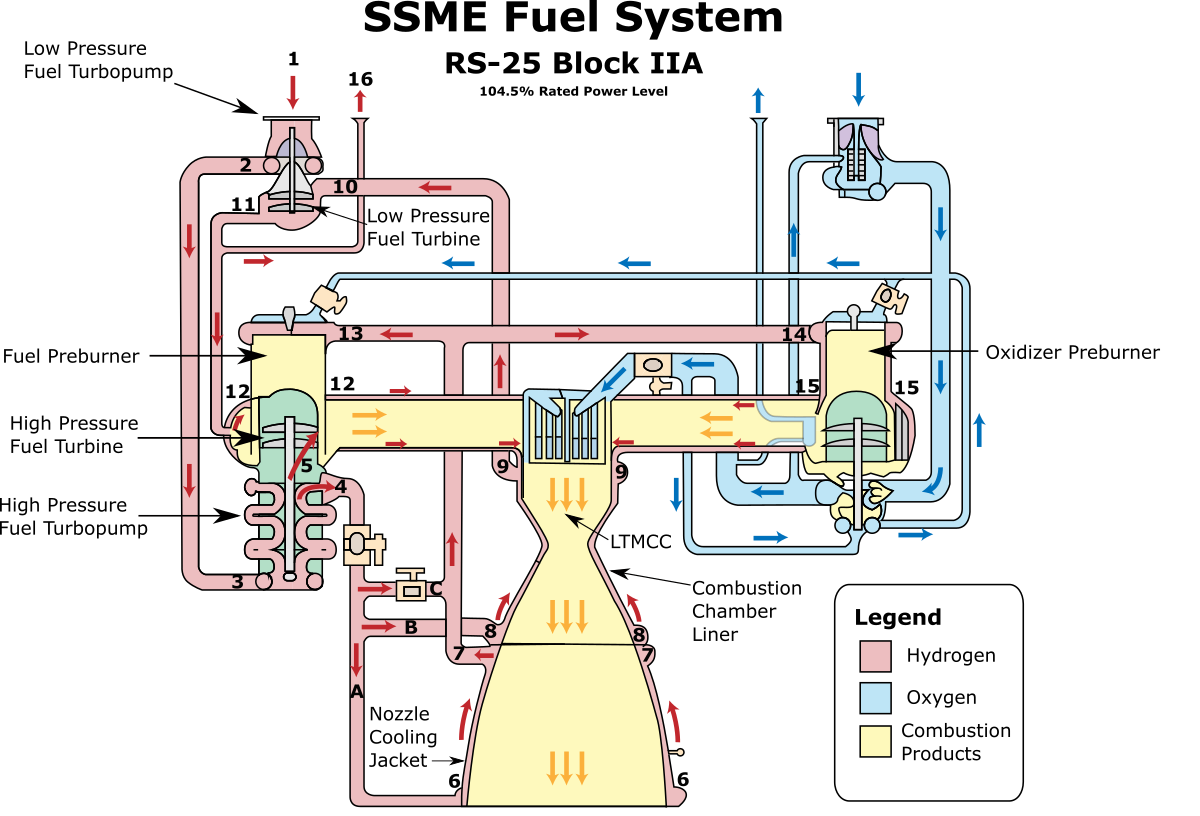

On the Space Launch System, the hydrogen fueling lines connect at the bottom of the core stage through two Tail Service Mast Umbilicals, or TSMUs. These are the gray structures you see extending above the launch platform in photos of SLS on the pad. The hydrogen TSMU has two lines—one 8 inches in diameter, one 4 inches—that connect through matching umbilical plates. These plates have seals that form the connection point.

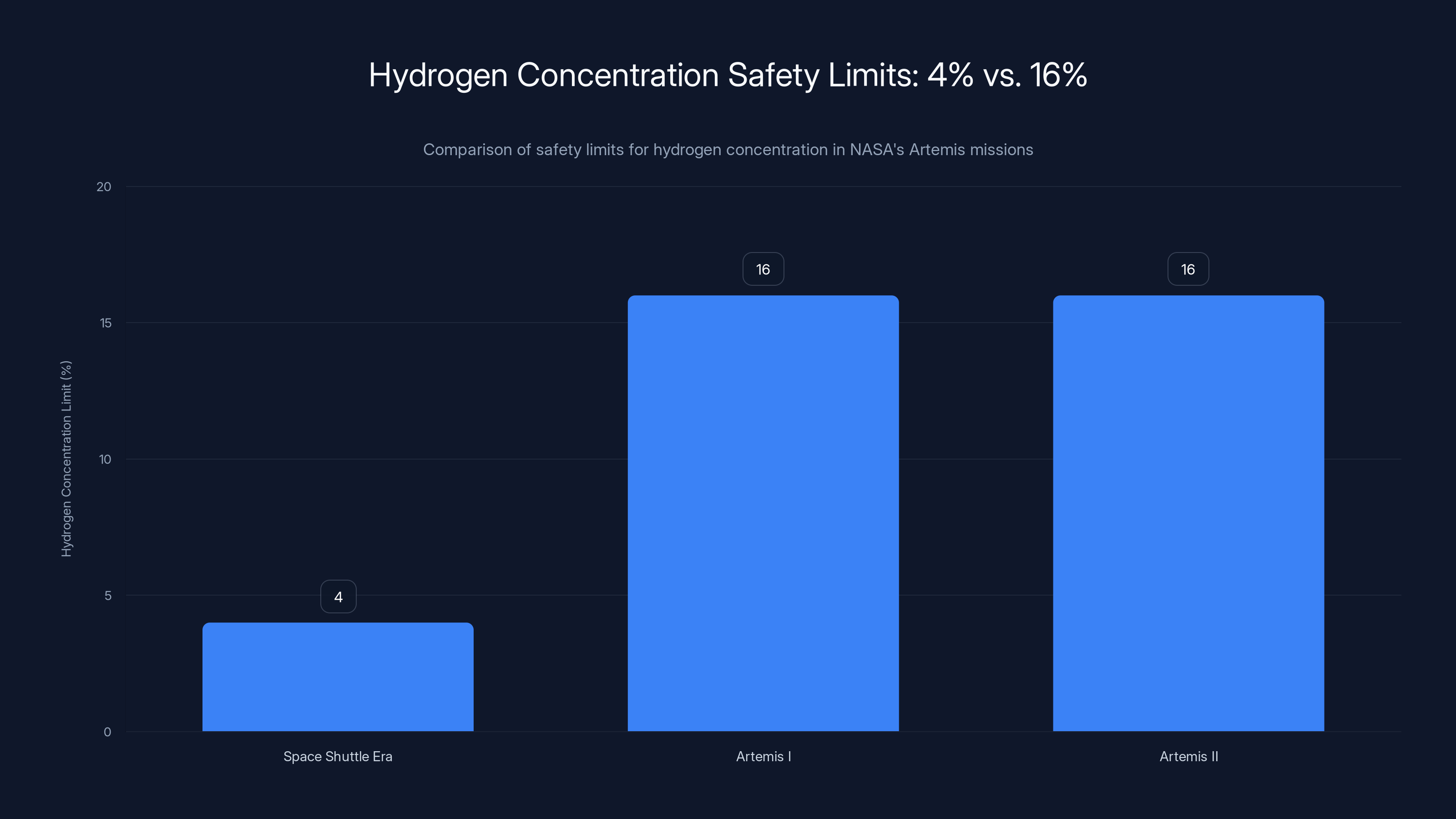

During the February 2 Wet Dress Rehearsal, hydrogen gas was detected in the area around these connection points at concentrations exceeding 16 percent—NASA's current safety limit. This is dangerous because hydrogen becomes explosive when mixed with air at concentrations above roughly 4 percent. So when you're getting spikes above 16 percent, you're dealing with a genuinely hazardous situation.

What made this particularly frustrating for NASA was that engineers had supposedly fixed this exact problem before Artemis I. They changed the fueling procedure—specifically how the super-cold liquid hydrogen was loaded into the core stage. That fix had seemed to work. But when they used the identical procedure on February 2, the leak came back.

This tells you something important: the fix wasn't actually a fix. It was a temporary patch that masked the underlying problem. And now NASA had to figure out what the actual problem was.

NASA raised the hydrogen concentration safety limit from 4% to 16% between Artemis I and II, based on specific environmental testing. Estimated data.

Artemis I's Hydrogen Lessons: The Three-Year Gap That Created Complacency

The Artemis I launch in 2022 should have been a dress rehearsal for a 2024 Artemis II crewed mission. Instead, the hydrogen leak at that launch pad caused months of delays. NASA's engineers traced the problem, made adjustments, and eventually launched successfully in November 2022.

Then nothing happened for three years. The SLS rocket sat on the pad. Artemis II's crew—Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Koch, and Jeremy Hansen—trained but didn't fly. The Space Launch System, designed to fly once per year, had become a once-every-three-years program at best.

During those three years, something subtle and dangerous happened in the engineering mindset. The leak wasn't solved—it was just put aside. Instead of investing in a fundamental redesign of the fueling connection system, NASA essentially got comfortable with hydrogen leaks as a fact of operations. The agency even raised its safety limit from 4 percent to 16 percent, reframing what had been an urgent safety problem as an acceptable operating parameter.

John Honeycutt, who previously served as NASA's SLS program manager and now chairs the Artemis II mission management team, explained the reasoning. NASA ran a test campaign that examined the characteristics of the cavity where the hydrogen concentrates, looked at the purge system's effectiveness, and tested hydrogen ignition thresholds. At 16 percent, they couldn't get hydrogen to ignite in those specific conditions. So they created a new safety limit.

This is where engineering meets institutional reality. The safety limit change wasn't reckless. It was grounded in test data. But it also reflected an uncomfortable truth: fixing the leak properly would have required more work, more time, and more money than NASA was willing to spend. Getting comfortable with higher leak rates was easier.

Now, in February 2025, that decision was coming back to haunt NASA. The leak reappeared right on schedule, suggesting that the problem was structural—something in how the connections were designed, manufactured, or installed.

The Root Cause: Ground Support Equipment Failures

After the February 2 Wet Dress Rehearsal ended abruptly, NASA's team did what they always do after a failure: they investigated. Engineers at Kennedy Space Center, along with contractors from Exploration Upper Stage (which builds the core stage) and Aerojet Rocketdyne (which supplies the fueling systems), traced the leak to specific components.

The culprit wasn't the rocket itself. It was the ground support equipment—specifically, the seals around the Tail Service Mast Umbilicals where the fueling lines connect to the core stage. These seals are where the 8-inch and 4-inch hydrogen lines interface with the rocket.

After the rehearsal, technicians replaced the seals. But on Thursday, February 20, when NASA ran a confidence test—a partial fueling test to verify the seals were working—something else went wrong. The launch team transitioned into "fast fill" mode for liquid hydrogen, which is when the seals experience the most stress and highest pressures. But before reaching full fast-fill conditions, the team noticed a reduction in fuel flow.

NASA investigated. The culprit this time appeared to be a filter in the fueling system. Engineers suspected the filter was partially clogged or failing, restricting hydrogen flow. Rather than push forward and risk damaging equipment or losing more data, the team decided to stop the test early.

But here's where things got interesting. Despite cutting the test short, NASA got useful data. The leak rates during this confidence test were materially lower than during the February 2 rehearsal. The seal replacements had worked. The test confirmed that engineers were moving in the right direction.

Jared Isaacman's characterization was telling: "I would not say something broke that caused the premature end to the test, as much as we observed enough and reached a point where waiting out additional troubleshooting was unnecessary." This is engineering-speak for: we got the confirmation we needed, so let's move on.

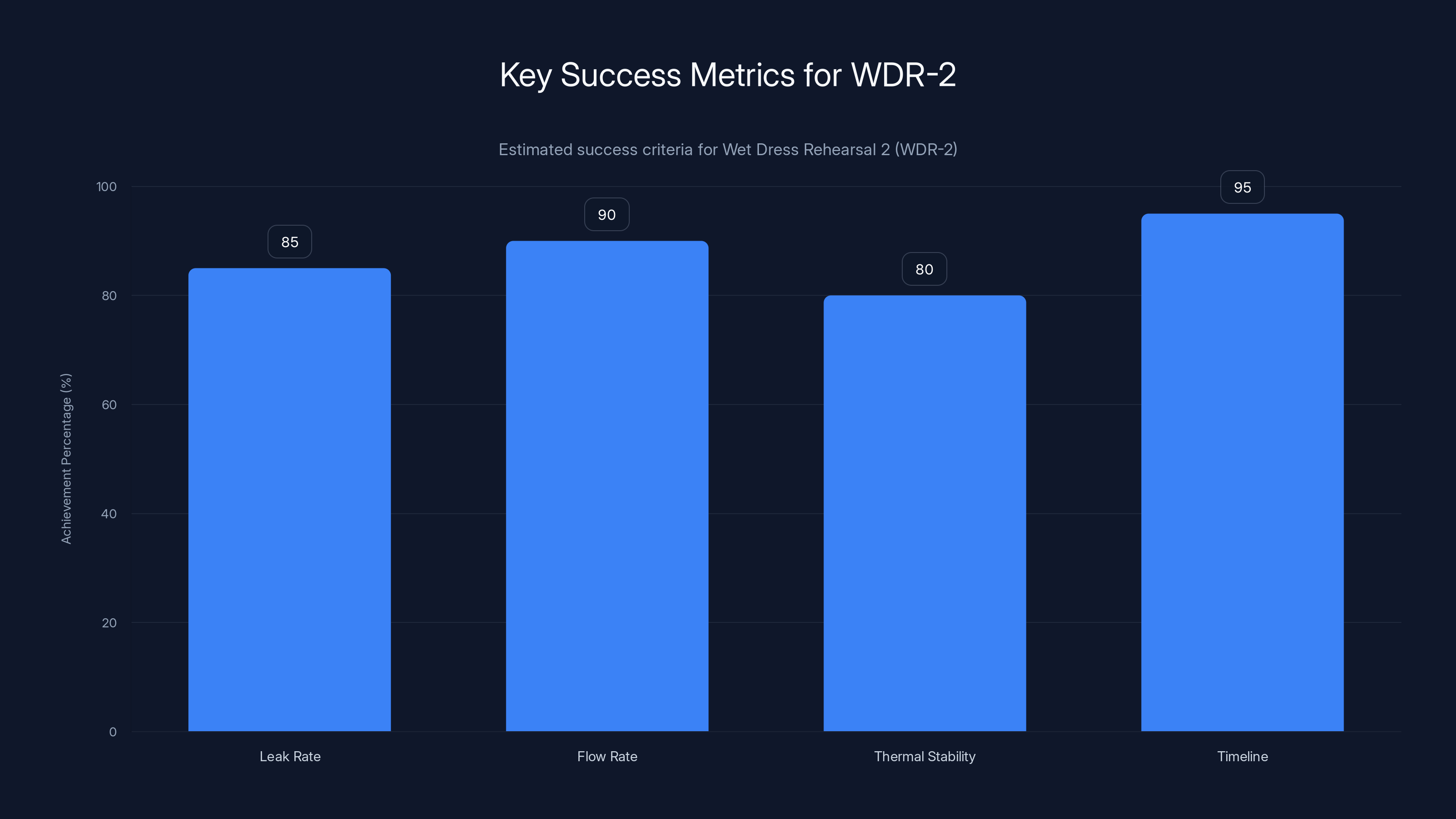

Estimated success rates for WDR-2 suggest high confidence in timeline and flow rate management, with thermal stability being the most challenging aspect. Estimated data.

Why Hydrogen Is So Hard to Contain: The Physics Beneath the Problem

Understanding why NASA struggles with hydrogen leaks requires understanding hydrogen's unique physical properties. This isn't just about engineering bad luck. It's about fundamental physics.

Hydrogen molecules are extraordinarily small. At the atomic level, a hydrogen atom has a radius of about 25 picometers—that's 0.000000025 millimeters. When two hydrogen atoms bond to form H2, the resulting molecule is still the smallest diatomic molecule known. This means hydrogen can diffuse through materials and find leak paths at the molecular level that other gases cannot.

The second problem is viscosity at cryogenic temperatures. Liquid hydrogen at minus 423 degrees Fahrenheit has different viscous properties than liquid oxygen, kerosene, or methane. These differences affect how it flows through lines, how much pressure is required to move it, and how it interacts with seals.

The third problem is material compatibility. Seals designed for room-temperature operations become brittle at cryogenic temperatures. Elastomers lose flexibility. Some metals become more brittle. The thermal contraction of different materials—steel shrinks at a different rate than aluminum, which shrinks differently than seals—creates gaps where hydrogen can escape.

Formula for thermal strain:

Where:

- = thermal strain

- = coefficient of thermal expansion

- = temperature change (475°F from ambient to liquid hydrogen)

For an aluminum component cooling from 70°F to minus 423°F, the thermal contraction is significant. If that component connects to a steel line with a different expansion coefficient, you get stress at the interface—exactly where seals need to maintain pressure.

The fourth problem is that hydrogen wants to escape. It's not just that it can find paths through materials—it actively seeks them. This is called embrittlement and permeation. Some materials actually allow hydrogen atoms to migrate through them at the atomic level, a process called hydrogen diffusion. A seal that prevents other gases from leaking might be permeable to hydrogen.

This is why the Space Shuttle program used special seals made of materials like Viton or other elastomers that resist hydrogen permeation. But even those seals have limits. Combine cryogenic temperatures with high pressure, add the vibration of a rocket being fueled and pressurized, and those seals begin to fail.

The final, counterintuitive problem is that successful hydrogen fueling procedures create familiarity that breeds complacency. Engineers who have successfully loaded liquid hydrogen dozens or hundreds of times can become less vigilant about the signs that a leak is developing. They know what normal looks like and what's acceptable. This can mask the early stages of seal failure.

The Confidence Test: What It Revealed and What It Meant

NASA's approach to the February 20 confidence test demonstrates how space agencies handle high-risk operations. You don't just jump to a full Wet Dress Rehearsal. You test in steps.

The goal of the confidence test was simple but critical: partially fill the core stage with liquid hydrogen and verify that the seal replacements had actually fixed the leak problem. This is more controlled than a full WDR but more realistic than just testing seals in isolation.

NASA's team filled the core stage partially, allowing them to measure hydrogen concentrations in the area around the fueling connections. If the seals worked, hydrogen concentrations would remain low. If they hadn't fixed the problem, concentrations would spike again.

What they found was encouraging. The leak rates dropped materially compared to the February 2 rehearsal. This confirmed that seal replacement had addressed the primary issue. But then the team attempted to transition to fast-fill mode—the most stressful phase of hydrogen loading, when high flow rates and high pressures stress the seals maximally—and noticed reduced flow.

The suspected cause was a filter in the hydrogen delivery system. Over three years on the pad, the filter had potentially accumulated contaminants, or perhaps it had simply accumulated ice particles from previous operations. Hydrogen's extreme cold can cause atmospheric moisture in fuel lines to freeze, creating blockages.

Rather than risk further damage or equipment failure, NASA decided to stop the test, investigate the filter, replace it, and then proceed to the next WDR. This is textbook engineering decision-making: you have confirmed your primary fix works, you've identified a secondary issue, you address it, and you move forward.

What Isaacman meant by "observed enough" was that NASA had gotten the critical data point: the seals were holding better. The filter issue was a separate, solvable problem. There was no value in continuing to stress a system with a partially clogged filter when the answer was to replace it.

Safety Limits and Risk Tolerance: The 4% vs. 16% Question

One of the most contentious aspects of the hydrogen leak story is NASA's decision to raise its hydrogen concentration safety limit from 4 percent to 16 percent between Artemis I and Artemis II.

To understand why this matters, you need to know that hydrogen becomes explosive when mixed with oxygen at concentrations as low as 4 percent. So 4 percent is the absolute threshold for hazardous conditions. NASA had carried that 4 percent limit forward from the Space Shuttle era as a conservative buffer—you avoid any conditions where hydrogen concentrations approach even 4 percent.

During Artemis I, hydrogen spikes reached 16 percent, which triggered the safety concern that led to delays and investigations. So instead of fixing the problem to stay below 4 percent, NASA's engineers ran tests to determine what hydrogen concentration would actually cause ignition in the specific environment where the leak occurs.

This specific environment matters. The fueling connection is in a cavity—an enclosed space but with specific dimensions, ventilation rates, and circulation patterns. Not all cavities behave the same way. NASA tested hydrogen ignition in this actual cavity and found that they couldn't get hydrogen to ignite at 16 percent under the prevailing conditions.

This created the scientific basis for raising the safety limit to 16 percent. It wasn't arbitrary. It was grounded in testing specific to the SLS fueling system. John Honeycutt explained the rationale: NASA tested the cavity characteristics, the purge system's effectiveness, and where hydrogen actually becomes ignitable in that environment.

But there's a subtle philosophical difference here. The old 4 percent limit said: "We won't allow conditions where hydrogen could become hazardous." The new 16 percent limit says: "We've tested and determined that hydrogen won't actually ignite in our specific cavity at 16 percent, so that's acceptable."

One approach is preventive. The other is data-driven but accepts higher risk levels. Both are defensible engineering positions. But they reflect different philosophies about how to manage an unresolved hardware problem.

The bigger picture is this: NASA got comfortable with the hydrogen leak as an operational reality rather than a problem to solve completely. This is pragmatic—you could potentially spend years and hundreds of millions of dollars to redesign the fueling system from the ground up. Or you can test the actual risk environment, establish data-driven safety limits, implement monitoring, and manage the operation carefully.

But pragmatism and rocket science are uncomfortable bedfellows. What seems like an acceptable risk on paper can become a genuine hazard if conditions are slightly different than expected or if multiple small problems combine in an unanticipated way.

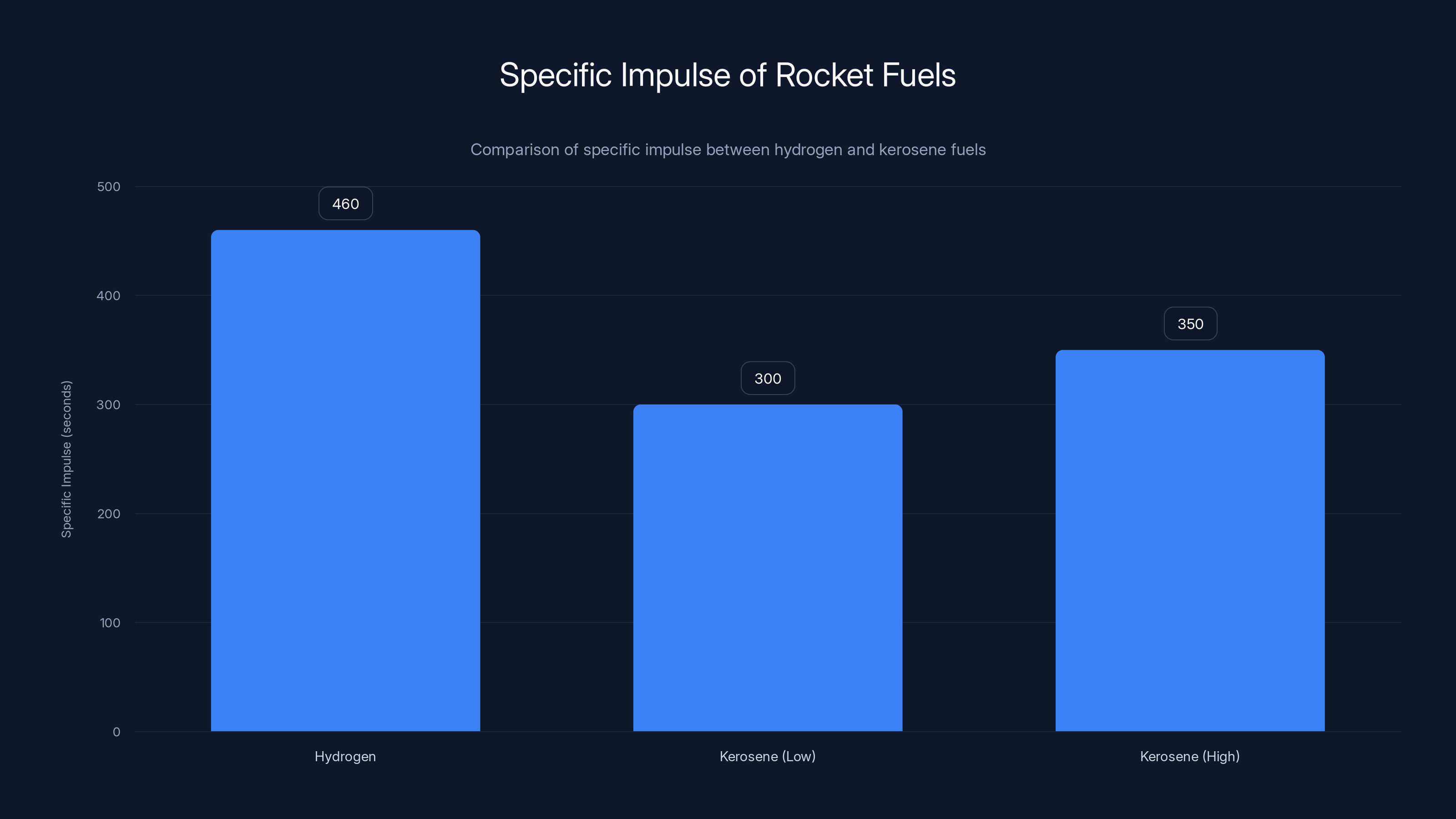

Hydrogen provides a superior specific impulse of 460 seconds compared to kerosene's range of 300-350 seconds, offering better performance for deep space missions.

Wet Dress Rehearsal Number Two: What NASA Must Prove

As of late February 2025, NASA was preparing for Wet Dress Rehearsal number two. This is critical. It's where everything gets tested together.

The goals for WDR-2 are unambiguous:

- Replace the suspected clogged filter in the hydrogen delivery system

- Verify that seal replacements continue to show low leak rates

- Complete the full hydrogen and oxygen loading sequence

- Transition into fast-fill mode with the hydrogen system under full stress

- Reach a countdown to less than 60 seconds before launch

- Safely drain the propellant tanks

If WDR-2 succeeds, it proves that NASA has solved the hydrogen leak problem—or at least solved it well enough to proceed. If it fails, the launch schedule slips again, and NASA faces difficult decisions about whether a fundamental redesign is necessary.

The stakes are enormous. Artemis II is a four-person crew mission. Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Koch, and Jeremy Hansen are trained and ready to fly. They've waited three years already. A delayed or canceled Artemis II doesn't just affect those four astronauts—it affects the entire Artemis program's momentum, public confidence, and political support.

Lessons from the Space Shuttle Era: Why This Problem Isn't New

When people talk about hydrogen leaks on the Space Shuttle, they're usually referring to the Main External Tank, which used hydrogen in its Reusable Launch Vehicle booster. The shuttle program dealt with hydrogen leaks repeatedly over 30 years of operations.

But the interesting pattern is that engineers never completely solved them. Instead, they developed better monitoring, better procedures, and better limits. They learned which leaks were acceptable and which weren't. They developed time windows for loading procedures and monitoring protocols during countdown.

The shuttle program's approach was fundamentally pragmatic: you cannot completely eliminate hydrogen leaks from complex fueling systems, so you manage them. You accept certain leak rates, you monitor closely, you stop operations if leaks exceed your safety limits, and you proceed carefully.

NASA seems to be returning to that same philosophy with Artemis, which is both comforting (this is proven operational knowledge) and concerning (shouldn't we have solved this by now?). The difference is that the shuttle program had 30 years to develop operational expertise with hydrogen systems. The SLS program has maybe five years at most, with three-year gaps between tests.

Contractor Responsibilities: Aerojet Rocketdyne and Exploration Upper Stage

When something goes wrong with SLS fueling systems, the responsible contractors come under scrutiny. Aerojet Rocketdyne built the hydrogen fueling system and connections. Exploration Upper Stage, which is part of Boeing Defense, Space and Security, built the core stage where the connections are located.

These contractors are expected to deliver systems that work. Hydrogen leaks on the launch pad become contractual and reputational issues. It's likely that both companies have teams dedicated to understanding and resolving the leak problem.

But here's the constraint: redesigning fueling connections takes time and passes through multiple review and test cycles. NASA doesn't approve changes to critical flight hardware quickly or casually. Every modification requires documentation, testing, analysis of failure modes, and verification before hardware is installed on the flight vehicle.

If the seal replacement strategy works—and early data suggests it does—NASA may avoid the need for major redesigns. But if leak rates remain high or develop again during WDR-2, NASA might be forced to accept either a delay while modifications are made, or a decision to proceed with managed hydrogen leak conditions.

Either way, the contractors are accountable. And contractors with accountability tend to move quickly when NASA says "fix this."

Hydrogen is significantly more challenging to contain in rocket systems compared to kerosene and methane due to its small molecular size and extreme temperature requirements. (Estimated data)

The Three-Year Gap Problem: Why Sitting Still Breaks Things

One factor that few people mention is the simple physics of vehicles sitting on the pad. When hardware sits dormant for three years, things degrade.

The SLS rocket has been exposed to Florida's corrosive salt air environment, temperature cycling, moisture infiltration, and the simple entropy of aging hardware. Seals that might have remained flexible with regular maintenance can harden. Connections that might have stayed clean with regular operations accumulate corrosion or contaminants.

This is different from vehicles in space, which exist in a stable vacuum environment. It's different from vehicles in hangars, which are climate-controlled. The SLS sits on the pad, exposed to the elements, with three years between meaningful operations.

Part of the hydrogen leak problem may simply be that the hardware degraded during the long wait. Seals aged. The fueling system's filter accumulated three years of contaminants. Connections developed oxidation or contamination from exposure.

This creates a vicious cycle: the longer the gap between missions, the more likely hardware will develop new problems, requiring more time to fix, which extends the gap further. The ideal solution is to fly the SLS regularly—once a year or more—so hardware doesn't have time to degrade. But that hasn't happened.

NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman acknowledged this in his statement: "Considering the issues observed during the lead-up to Artemis I, and the long duration between missions, we should not be surprised there are challenges entering the Artemis II campaign. That does not excuse the situation, but we understand it."

Translation: we knew this would be hard. We knew the long gap would create problems. But we're going to fix them anyway.

The Path Forward: Cryoproof Testing Before Artemis III

Isaacman made a critical commitment in his February 22 statement: before Artemis III, NASA will "cryoproof" the Space Launch System. This means subjecting the vehicle to a full cold-temperature cycle while in the launch configuration, testing every system that will handle cryogenic propellants.

Cryoproofing is the most comprehensive test of cryogenic systems possible short of an actual launch. It takes a fully assembled rocket, fills it with liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen, lets the systems stabilize at cryogenic temperatures, runs all the monitoring and safety systems, and verifies that every connection, seal, line, and component works as designed.

The Space Shuttle program did cryoproof testing. It's the gold standard for verifying that a cryogenic rocket is ready to fly.

NASA hasn't done a full cryoproof test of SLS yet. Artemis I flew without it—NASA tested systems piecemeal but never subjected a fully assembled SLS to the stress of full cryogenic loading and thermal stabilization. Artemis II's Wet Dress Rehearsals are partial cryoproofs but not complete.

Committing to cryoproof testing before Artemis III is significant. It's an admission that the current testing approach has gaps. It's also a promise that before crewed flights to the Moon, NASA will have subjected SLS to the most comprehensive hydrogen fueling test possible.

But Artemis III is likely at least three years away, possibly longer. That's a long time to wait for ultimate verification that the system works.

Implications for the Artemis Timeline: When Will Crewed Missions Actually Launch?

Artemis II's launch date was originally 2024. Then 2025. As of February 2025, the launch date isn't formally announced—NASA is working through hardware problems first.

Historically, when NASA encounters issues this significant, launch delays of six months to a year are common. If WDR-2 succeeds in March 2025, NASA might be able to launch Artemis II by late 2025 or early 2026. If WDR-2 reveals more problems, the timeline stretches again.

Artemis III, the actual Moon landing mission, is scheduled for sometime after Artemis II. Currently, estimates range from 2027 to 2030. The hydrogen leak issues might push that further.

This matters because other countries are pursuing lunar programs with potentially shorter timelines. China's lunar ambitions are accelerating. Other nations are developing competing lunar access systems. Every year NASA delays is a year that other programs get closer to achieving their goals.

But the alternative—launching before systems are proven—is worse. The Artemis program represents a commitment to sustainable lunar exploration. That has to start with hardware that works reliably.

The Artemis program has faced hydrogen leak issues in 2022 and 2025, impacting mission timelines (Estimated data).

The Bigger Picture: Why SLS Costs So Much and Still Has These Problems

The Space Launch System has consumed over $23 billion in development costs by some estimates, making it the most expensive launch vehicle program in history. Yet it struggles with hydrogen leaks that engineers thought they'd solved decades ago.

This creates an obvious question: where did the money go?

Most of it went to massive infrastructure development at Kennedy Space Center, the construction of the vehicle itself, extensive ground support equipment, and the development of the Orion spacecraft that flies on top of SLS. A smaller portion went to addressing issues and problems that emerge during development.

But here's the inconvenient truth: money doesn't guarantee that engineering problems disappear. Hydrogen leaks aren't a money problem. They're a physics problem. You can spend billions on ground support equipment, flight hardware, and testing, and still face the fundamental challenge that hydrogen is difficult to contain at cryogenic temperatures.

What money does buy is time, expertise, and the ability to try multiple solutions. NASA has done that. The seal replacements, the safety limit reassessment, the confidence testing—all of these cost money and represent solutions being tried.

But the core problem—how to achieve truly leak-free hydrogen fueling connections on a system as large and complex as SLS—remains genuinely difficult.

International Perspectives: How Other Programs Handle Hydrogen

NASA isn't alone in struggling with hydrogen systems. The European Space Agency's Ariane 5 rocket uses hydrogen in its upper stage. Space X Falcon 9 uses kerosene and liquid oxygen—hydrogen never gets mentioned as an option. Blue Origin's New Glenn is designed to use hydrogen and has required extensive development of cryogenic systems.

The fact that Space X avoided hydrogen for its most successful vehicle is telling. Kerosene (called RP-1) is heavier than hydrogen, so you need more fuel mass for the same energy. But RP-1 is room-temperature, soluble in most conventional materials, and relatively forgiving. It's easier to manage operationally.

NASA chose hydrogen for SLS because of Specific Impulse—the efficiency metric for rocket engines. Hydrogen-oxygen engines produce roughly 460 seconds of specific impulse, compared to 300-350 for kerosene-oxygen combinations. This efficiency matters enormously for deep space missions.

But the trade-off is operational complexity. You get more performance from your fuel mass, but you sacrifice simplicity. This is a classic engineering trade: performance versus practicality.

European Ariane 5 has operated successfully with hydrogen systems since the 1990s, so it's clearly possible to make hydrogen work reliably. But Ariane developed over decades with hundreds of flights to build operational expertise. SLS hasn't had that luxury.

Expert Analysis: What Honeycutt's Leadership Suggests About NASA's Direction

John Honeycutt's previous role as SLS program manager and current role chairing the Artemis II mission management team means he has deep perspective on both the technical issues and the organizational responses.

His explanation of the safety limit reassessment is worth taking seriously. He's not a contractor making excuses; he's a NASA official with decades of spaceflight experience. When he explains that the limit was changed based on testing, that carries weight.

But Honeycutt's leadership of the mission management team also signals that NASA is treating this seriously at the highest levels. These teams meet frequently, review extensive data, and make critical decisions about whether to proceed or delay. If Honeycutt sees problems that can't be solved, NASA will delay.

Conversely, if Honeycutt and Isaacman approve proceeding toward launch after confidence testing, that also carries meaning. These are professionals whose reputations are tied to mission success.

Managing liquid hydrogen involves high severity challenges such as leak path management and material brittleness due to its small molecular size and low temperature. Estimated data.

Testing and Monitoring: The Real Solution to Hydrogen Leaks

Ultimately, the solution to SLS hydrogen leaks isn't a single technology or design change. It's a combination of better seals, better filters, careful procedures, extensive monitoring, and conservative safety limits.

During countdown, NASA has sensors throughout the fueling area that detect hydrogen concentrations continuously. These sensors feed data to launch controllers in real-time. If concentrations spike above safe limits, controllers can stop the countdown immediately.

This monitoring is so good that launch teams can distinguish between a minor leak that poses no hazard and a developing leak that indicates a problem. Over time, as hydrogen loading proceeds, they can see whether leaks are stable or growing.

The filter replacements and seal updates address the sources of the leaks themselves. Better seals mean less hydrogen escapes. Cleaner filters mean fuel flows without restriction. Together, these changes should produce lower leak rates during WDR-2.

If that works, NASA can proceed to launch with confidence that the system is operating within tested and proven parameters.

What Happens If WDR-2 Fails

Scenario planning in aerospace is mandatory. Assume WDR-2 doesn't go smoothly. What are NASA's options?

Option one: the leak rates remain low enough that NASA proceeds to launch. This is the hope.

Option two: the leak rates exceed limits but identify a solvable problem (like another clogged filter or slightly incorrect seal installation). NASA addresses it, runs a WDR-3, and proceeds to launch. This adds months.

Option three: the leak rates indicate a deeper problem requiring hardware modification. Seals need redesign, connections need reconfiguration, umbilicals need replacement. This could add a year or more to the schedule.

Option four: the leak rates are high enough and the problems complex enough that NASA questions whether the current design can be made reliable. At that point, engineering teams explore redesigns or fundamental changes to how the fueling system connects to the rocket.

NASA would strongly prefer option one. The agency has invested years in current approaches and has operational expertise with the current system. A redesign would reset timelines and introduce new risks.

But the commitment to cryoproof before Artemis III suggests that NASA is willing to take additional time to ensure systems work before committing crews to the vehicle. That's the right instinct.

The Human Element: Four Astronauts Waiting

When discussing technical problems, it's easy to forget that Artemis II carries four people: Reid Wiseman (Commander), Victor Glover (Pilot), Christina Koch (Mission Specialist), and Jeremy Hansen (Mission Specialist). Hansen is Canadian, representing the Canadian Space Agency's commitment to the Artemis program.

These are experienced astronauts. Wiseman and Glover are shuttle veterans. Koch has flown to the International Space Station. They're trained to handle the vehicle in any condition—nominal operation or emergency scenarios.

But training for a spacecraft means nothing if the spacecraft isn't ready to launch. These four astronauts have been waiting for years. Every delay is personal, even though they understand intellectually that the delays serve a critical purpose: making sure the rocket can be flown safely.

NASA's commitment to solving the hydrogen leak problem before Artemis II carries an implicit promise to these four: we won't send you to the Moon on an unproven system. Hydrogen leaks will be addressed. The rocket will work.

That's the weight behind Isaacman's public commitment. It's not just about the schedule. It's about the trust between an agency and the people who are willing to ride 2.5 million pounds of carefully controlled explosions toward the Moon.

Contractor Accountability and Hardware Quality

When seal failures and filter problems emerge, contractors face scrutiny. Aerojet Rocketdyne built fueling systems with seals that apparently weren't adequate to the task. Exploration Upper Stage delivered a core stage where the fueling connections didn't perform as designed.

But contractors also push back. They argue that the problems are inherent to hydrogen systems, not unique to their designs. That seal degradation occurs naturally over time and isn't preventable. That three-year gaps between operations create challenges no contractor can fully mitigate.

There's truth in both perspectives. Hydrogen is genuinely difficult to contain. But contractors are also supposed to anticipate these challenges and design systems that overcome them.

The solution is typically rigorous root cause analysis followed by corrective action. NASA's engineers identify the specific failure mode (seal degradation, filter contamination), determine why it occurred, and implement fixes. Contractors are held accountable for those fixes.

This process is working. Seal replacements are being made. Filters are being replaced. New procedures are being tested. Whether the fixes hold will be determined by WDR-2.

The Broader Artemis Vision: Why This Matters Beyond the Technical Details

Artemis isn't just about returning to the Moon. It's about establishing sustained human presence in lunar orbit and on the lunar surface. Multiple missions. Multiple landing sites. Permanent infrastructure eventually.

That vision requires a rocket that works reliably. An SLS program that flies with regularity. A launch schedule that can support multiple missions per year, not one every three years.

The hydrogen leak problems are revealing that SLS isn't yet ready for that mission cadence. Getting to once-per-year flights requires not just solving individual problems like hydrogen leaks, but creating an operational rhythm where hardware is regularly exercised, systems are routinely tested, and teams have continuous experience.

Right now, the long gap between Artemis I and Artemis II is the opposite of that. It's creating the conditions where problems like hydrogen leaks can emerge and surprise even experienced teams.

Solving the leaks is necessary but not sufficient. NASA also needs to fundamentally change how SLS operates—flying more regularly, maintaining more consistent operational experience, and building a culture of continuous improvement rather than "fix it once then don't touch it for three years."

Lessons for Future Rocket Development

If engineers designing the next generation of human-rated rockets were to learn from SLS's hydrogen leak experience, what would those lessons be?

First: cryogenic fueling systems deserve more design attention than they typically receive. They're complex, they involve extreme conditions, and they're critical to mission success. Investing in better seal materials, better connection designs, and better testing infrastructure pays dividends.

Second: operational experience matters enormously. Rockets that fly regularly are better understood, better maintained, and less prone to surprise failures. Programs should be structured to achieve regular flight rates from early in their operational history.

Third: accepting higher leak rates as normal is a trade-off, not a solution. If leaks are unavoidable, the right approach is comprehensive testing that defines safe operating parameters, not simply raising safety limits until problems disappear from the paperwork.

Fourth: three-year gaps between tests are operationally damaging. Hardware degrades, teams lose continuity, and the learning curve flattens. Future programs should be designed with annual or more frequent test and flight objectives from the start.

Fifth: transparency about problems builds confidence more than silence does. Isaacman's public statements about hydrogen leaks, safety limits, and fix timelines demonstrate leadership that trusts the public and the astronauts to understand engineering challenges.

Timeline Predictions: When Can NASA Really Launch Artemis II?

Based on typical NASA testing patterns, here's a realistic timeline:

February-March 2025: Replace filters, repeat confidence test, verify seal performance holds up.

March-April 2025: Conduct WDR-2 with full hydrogen and oxygen loading. If successful, declare the system ready for launch operations.

May-June 2025: Final vehicle assembly, connection verification, and systems testing on the pad. Run final checklist items before committing to launch date.

July 2025 or later: Launch window opens. Weather, technical issues, or other factors might delay specific launch attempts, but the vehicle should be ready.

This assumes WDR-2 goes well. If it reveals new problems, add 3-6 months. If those problems require hardware redesign, add 12-18 months.

My prediction: Artemis II launches in late 2025 or early 2026, with success on WDR-2 being the critical gate. If that test shows low, stable leak rates and successful fast-fill transitions, NASA will feel confident enough to proceed.

The Bigger Stakes: Competition, Politics, and the Moon

The hydrogen leak story matters technically, but it also matters strategically. The United States is not the only country working toward sustained lunar exploration. China is accelerating its lunar program. The European Space Agency is planning Artemis contributions. India has demonstrated successful lunar missions.

Every delay to Artemis II is another year when other nations' programs advance. China has repeatedly stated ambitions to land humans on the Moon in the 2030s. If the Artemis program slips significantly, that timeline becomes more competitive.

From a geopolitical perspective, NASA's hydrogen leak problems aren't just engineering challenges. They're evidence that American rocket engineering faces real constraints, even with massive funding. That's relevant to decisions about future space policy, budget allocation, and international partnerships.

But it's also worth noting that other major rockets have faced similar technical challenges. Ariane 5 experienced lengthy development timelines. The Space Shuttle took years to mature into reliable operations. Large rockets are hard. Fixing large rockets is harder.

The fact that NASA is transparent about hydrogen leak challenges, is implementing fixes, and is committing to cryoproof testing suggests institutional maturity. The agency isn't hiding problems. It's solving them.

What Success Looks Like for WDR-2 and Beyond

Success for the next Wet Dress Rehearsal means:

Leak Rate Success: Hydrogen concentrations remain below 16 percent throughout the loading sequence and never spike dangerously above prior observed levels.

Flow Success: Hydrogen flow rates match expectations during transition to fast-fill. No filter blockages. No unexpected restrictions.

Thermal Success: Core stage remains thermally stable throughout the loading and fast-fill sequence. No unexpected temperature spikes that would indicate seal failures.

Timeline Success: The test completes as planned, reaches the intended countdown point (less than 60 seconds), and data quality is sufficient to declare confidence in system performance.

If all of this happens, NASA can declare the hydrogen fueling system ready for flight operations. That clears the path for Artemis II.

Common Questions About SLS and Hydrogen Leaks

Why does SLS use hydrogen when other rockets use easier fuels? Hydrogen delivers superior specific impulse (roughly 460 seconds compared to 300-350 for kerosene). For deep space missions, that extra efficiency matters enormously. You get better performance per pound of fuel mass, which translates to greater payload capacity or longer range.

Can't NASA just change the design to avoid hydrogen leaks? Changing away from hydrogen would reduce performance. Changing the fueling system design would require new hardware, extensive testing, and could add years to the program. Current approaches—better seals, monitoring, safety limits—are likely faster.

How dangerous is a hydrogen leak on the launch pad? Hydrogen is explosive when mixed with air at concentrations above 4 percent. At 16 percent, ignition requires specific conditions (adequate ignition source, oxygen availability, confinement). NASA's testing suggests the fueling area conditions make ignition unlikely above 16 percent, but that's based on modeling and testing, not absolute certainty.

What if WDR-2 shows the leaks are unfixable? Then NASA faces harder choices: proceed with accepted leak rates and tight monitoring, or redesign systems, or delay further. The cryoproof commitment before Artemis III suggests NASA would rather delay than proceed with uncertain systems.

Will Artemis II actually launch in 2025? Possibly. If WDR-2 succeeds, late 2025 or early 2026 is realistic. Earlier predictions were optimistic; current constraints suggest mid-2026 is more likely.

Does this hydrogen problem mean SLS is a bad rocket? Not at all. Hydrogen fueling challenges are inherent to hydrogen systems, not unique to SLS. The fact that NASA is addressing them transparently and committing to cryoproof testing suggests the vehicle will ultimately be reliable. But it will take time.

Why did NASA wait three years between Artemis I and II? Various factors contributed: Orion heat shield redesigns, SLS engine assembly challenges, supply chain issues from COVID, and resource allocation to other programs. The long gap created conditions where hydrogen systems degraded and new problems emerged.

Can the Space Shuttle experience with hydrogen help SLS? Absolutely. Shuttle engineers developed decades of operational knowledge about hydrogen systems. That knowledge is being applied to SLS procedures, monitoring, and safety limits. NASA is learning from history.

What percentage of SLS's cost goes to fixing hydrogen leak problems? Unknown publicly, but likely a small percentage of the overall program budget. Most costs are structural: vehicle development, core stage manufacturing, engine development, and ground support infrastructure.

How confident should we be that Artemis II will launch safely? Moderately confident. NASA's engineering teams are competent, testing procedures are rigorous, and safety consciousness is high. But hydrogen is genuinely difficult to manage. Unanticipated problems could still emerge.

FAQ

What exactly is the hydrogen leak problem affecting Artemis II?

During the February 2 Wet Dress Rehearsal, hydrogen gas was detected leaking from the connection points where fueling lines join the SLS rocket's core stage. The leak occurred at the Tail Service Mast Umbilical (TSMU) connections, specifically around the 8-inch and 4-inch diameter hydrogen lines that carry super-cold liquid hydrogen into the rocket during the countdown. Hydrogen concentrations in the area spiked above 16 percent, which is NASA's current safety limit. This was the same type of leak that had delayed Artemis I in 2022.

Why is hydrogen so hard to contain in rocket systems?

Hydrogen presents unique challenges because it's the smallest molecule known, meaning it can diffuse through seals and materials at the molecular level that other fuels cannot. Additionally, liquid hydrogen exists at minus 423 degrees Fahrenheit, causing materials to contract and creating gaps where leaks can occur. Hydrogen is also explosive when mixed with air at concentrations above 4 percent, adding safety complexity. These properties make hydrogen-fueling systems inherently more challenging to design and operate than systems using other fuels like kerosene or methane.

What is a Wet Dress Rehearsal and why is it important?

A Wet Dress Rehearsal (WDR) is a complete practice countdown test where ground teams load actual cryogenic propellants (liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen) into the rocket, run all systems as if preparing for launch, and count down to a predetermined point—usually less than 60 seconds before launch—before stopping and draining the tanks. It's the most comprehensive test possible without actually igniting the engines. For the SLS, WDRs are critical because they stress the fueling systems exactly as a real launch would, revealing problems that laboratory tests might miss.

Did NASA try to fix this hydrogen leak problem after Artemis I?

Yes, NASA modified the hydrogen loading procedure after Artemis I, changing how super-cold liquid hydrogen is introduced into the core stage. Engineers thought this fix had resolved the issue. However, when technicians used the same procedure on February 2 for Artemis II's WDR, the leak reappeared, suggesting the original fix addressed symptoms rather than the underlying problem. The real issue appears to be in the ground support equipment seals and connections, not the loading procedure itself.

Why did NASA raise the hydrogen safety limit from 4 percent to 16 percent?

NASA raised the safety limit from 4 percent to 16 percent based on specific testing of the fueling connection cavity on the SLS. While hydrogen becomes combustible at concentrations above 4 percent in general conditions, NASA ran tests to determine when hydrogen would actually ignite in the specific cavity where the leak occurs. Testing showed that the unique characteristics of that cavity—its dimensions, ventilation, and circulation patterns—make hydrogen ignition unlikely above 16 percent under normal fueling operations. The 16 percent limit is data-driven, but it reflects NASA accepting higher leak rates rather than solving the leaks completely.

What are the Tail Service Mast Umbilicals (TSMUs) and why do they matter?

The TSMUs are the gray structures extending from the SLS launch platform that carry liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen from ground support equipment into the rocket during countdown. The hydrogen TSMU has two fuel lines (8 inches and 4 inches in diameter) that connect to matching plates on both the rocket and ground equipment sides. These connections are where the hydrogen leak is occurring because the seals around these plates are failing or degrading. Replacing and upgrading these seals is central to NASA's fix strategy.

What does "cryoproof" testing mean and why is NASA committing to it before Artemis III?

Cryoproof testing means subjecting a fully assembled rocket to extreme cold conditions while in launch configuration, filling it with liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen, and operating all systems at cryogenic temperatures to verify everything works correctly. It's the most comprehensive test possible short of an actual launch. NASA committed to cryoproof testing before Artemis III because the current testing approach for Artemis II, while rigorous, doesn't subject the complete assembled vehicle to the full stress of cold operations. Cryoproof testing will definitively prove the hydrogen fueling system is ready before committing a crewed mission.

Why does SLS use hydrogen if it causes so many problems?

SLS uses hydrogen because it produces superior specific impulse—a measure of rocket engine efficiency—delivering roughly 460 seconds compared to 300-350 seconds for kerosene-based rockets. This extra efficiency allows SLS to carry more payload to the Moon or beyond. The performance advantage is significant enough that NASA accepted the operational complexity of managing hydrogen systems. The alternative would be either accepting lower payload capacity or using alternative fuels that don't deliver the deep-space performance needed for Artemis missions.

What happens if the next Wet Dress Rehearsal also shows hydrogen leaks?

If the February-March 2025 WDR-2 reveals that seal replacements and filter cleaning haven't adequately addressed leak rates, NASA faces escalating options. First attempt: run additional troubleshooting and try WDR-3. Second option: implement hardware modifications to the fueling connections, which could add 6-18 months. Third option: undertake more fundamental redesigns of the fueling system. NASA has committed to solving these problems before Artemis III at minimum, but the desire is to resolve them before Artemis II launches. The timeline impacts will depend on what WDR-2 reveals.

How does NASA monitor hydrogen during the actual countdown to prevent dangerous leaks?

NASA has hydrogen concentration sensors throughout the fueling area that continuously measure gas concentrations during countdown. These sensors feed real-time data to launch control. If hydrogen concentrations exceed safe limits or spike unexpectedly, launch controllers can immediately halt the countdown and stop fueling operations. This monitoring system is sophisticated enough to distinguish between minor, stable leaks and developing leaks that indicate problems. The approach combines hardware improvements (better seals) with operational safeguards (continuous monitoring and the ability to stop if necessary).

When will Artemis II actually launch?

No firm launch date has been announced, but realistic projections suggest late 2025 or early 2026, assuming WDR-2 succeeds in March 2025. If that test shows adequately low and stable leak rates, NASA would proceed toward final vehicle assembly and launch operations, potentially reaching a launch window in summer or fall 2025. However, technical issues, weather, or unexpected problems could delay specific launch attempts. The critical gate is WDR-2's success in demonstrating that seal replacements and system modifications have effectively addressed hydrogen leak rates to acceptable levels.

The Path Forward for Artemis and American Lunar Exploration

The hydrogen leak problem plaguing Artemis II is frustrating, but it's not insurmountable. NASA has identified the issue, implemented solutions, and is systematically testing whether those solutions work. The agency is also committing to cryoproof testing before Artemis III, ensuring that by the time crewed missions land on the Moon, the rocket will have been subjected to the most comprehensive verification possible.

What this situation reveals is that large, complex rockets are exactly that: large and complex. Hydrogen fueling systems push the boundaries of what's physically possible to contain and control. There are no easy solutions, only engineered answers that balance performance, reliability, safety, and schedule.

Isaacman's leadership in being transparent about these challenges while committing to solving them builds confidence. The agency isn't hiding problems behind bureaucratic language. It's explaining the physics of why hydrogen is difficult, showing what's being done to address it, and setting clear expectations for what verification will occur before crewed flights.

That's how you lead a program toward the Moon while keeping public and congressional trust intact. Not by pretending problems don't exist, but by acknowledging them, explaining them, and demonstrating competence in solving them.

Artemis II will launch when the systems are ready, not before. The four astronauts waiting for that mission deserve nothing less than confidence that the rocket beneath them has been tested, verified, and proven to work. The hydrogen leak problem is the challenge between current reality and that goal. But based on everything we know about NASA's engineering culture and competence, that challenge will be overcome.

The Moon is waiting. But it can wait for proven systems.

Key Takeaways

- NASA discovered hydrogen leaks from SLS fueling connections during Artemis II's February 2 Wet Dress Rehearsal, the same problem that delayed Artemis I three years earlier

- Hydrogen's molecular size allows diffusion through seals at cryogenic temperatures (minus 423°F), making it inherently difficult to contain compared to other rocket fuels

- Rather than fundamentally redesigning the fueling system, NASA raised its hydrogen safety limit from 4 percent to 16 percent based on cavity-specific testing, accepting higher leak rates as operational reality

- Engineers traced the leak source to seals in the Tail Service Mast Umbilical (TSMU) connections where 8-inch and 4-inch diameter hydrogen lines meet the core stage

- NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman committed to cryoproof testing before Artemis III—the most comprehensive verification possible—demonstrating institutional commitment to solving problems before crewed missions

Related Articles

- NASA's SLS Rocket Problem: Why the Costliest Booster Flies So Slowly [2025]

- SpaceX Starship Upper Stage Malfunction: Launch Recovery Timeline [2025]

- NASA Artemis 2 Launch Delayed to March: What the Hydrogen Leak Means [2025]

- Artemis II Wet Dress Rehearsal: NASA's Final Test Before Moon Launch [2025]

- SpaceX's Moon Base Strategy: Why Mars Takes a Backseat in 2025 [2025]

- NASA Astronauts Can Now Bring Smartphones to the Moon [2025]

![NASA's Artemis II Hydrogen Leak Crisis: What Went Wrong [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nasa-s-artemis-ii-hydrogen-leak-crisis-what-went-wrong-2025/image-1-1771105025974.jpg)