How the US Secretly Spied on Soviet Communications From High Above the Arctic

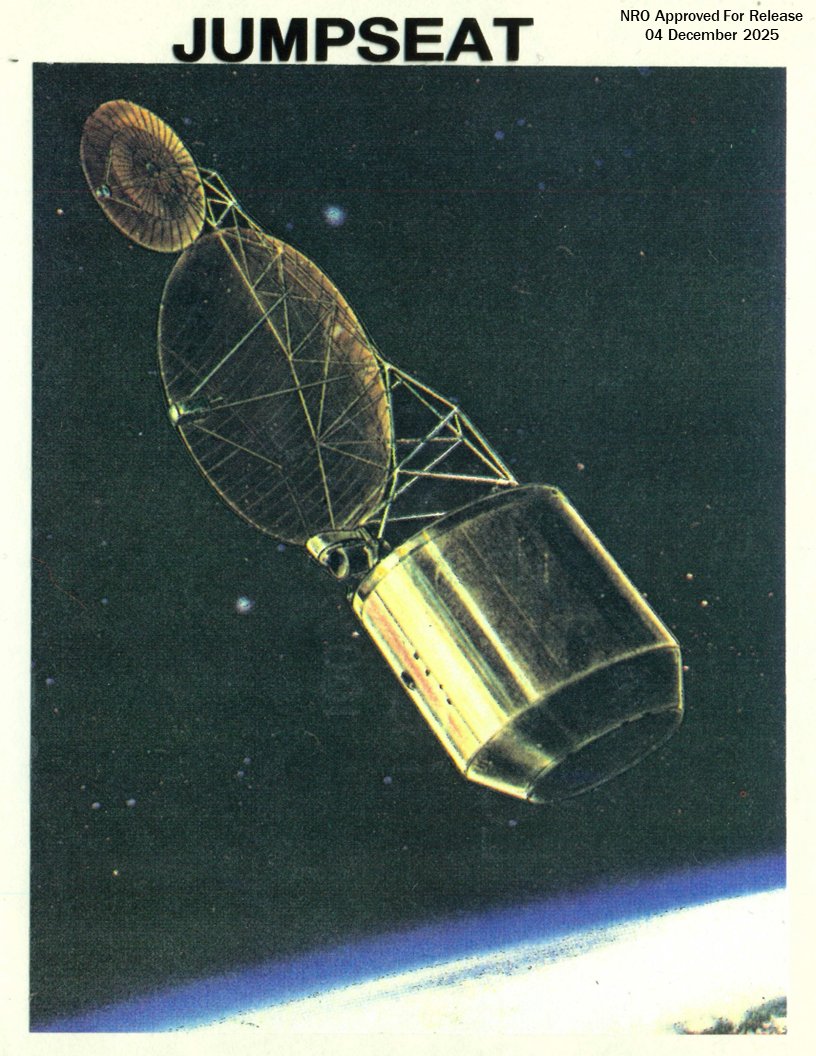

For decades, the details of one of America's most sophisticated Cold War surveillance programs remained locked behind classified doors at the National Reconnaissance Office. But in December 2024, something remarkable happened. The NRO officially declassified key information about the JUMPSEAT program, lifting the veil on a network of spy satellites that revolutionized signals intelligence collection from space.

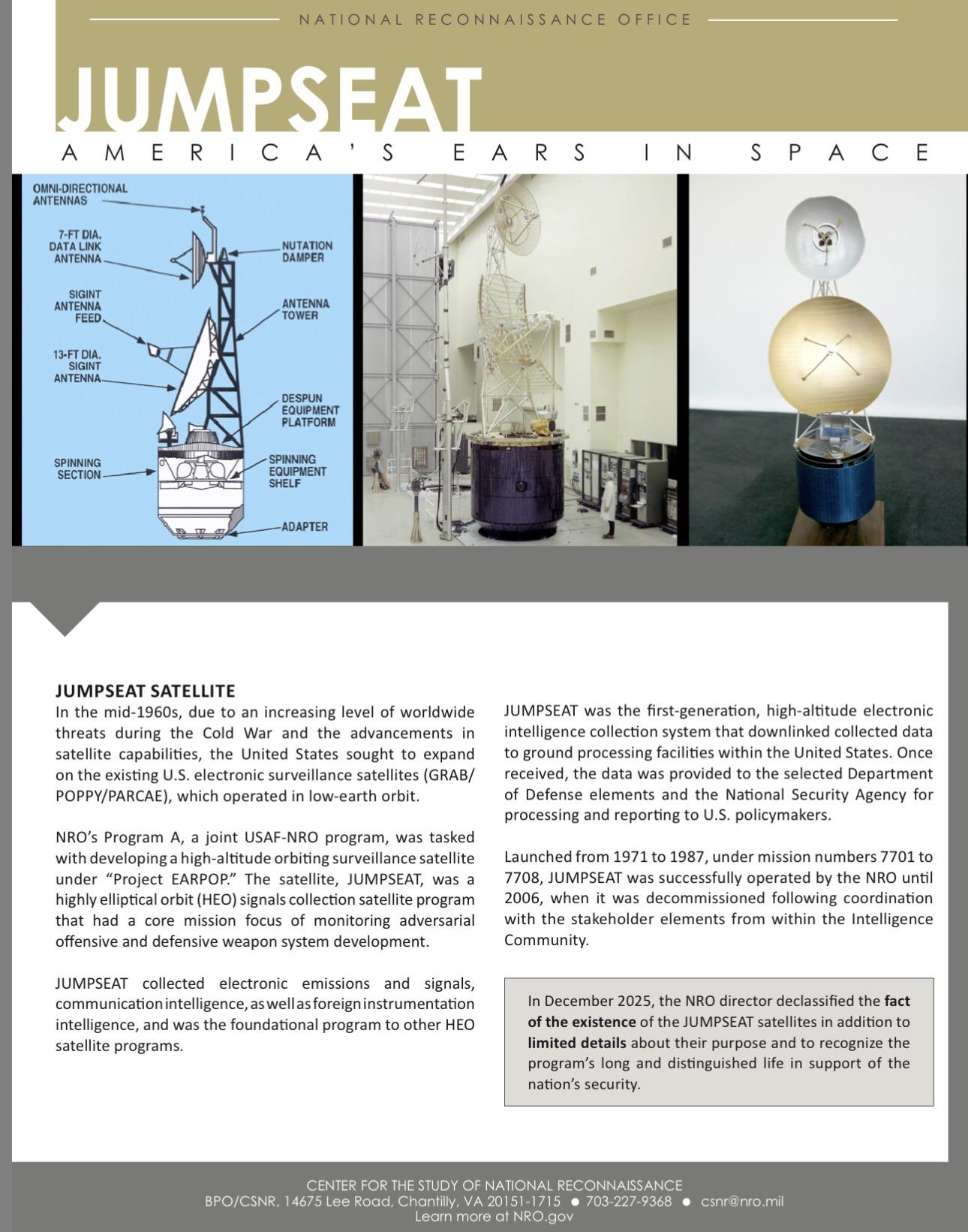

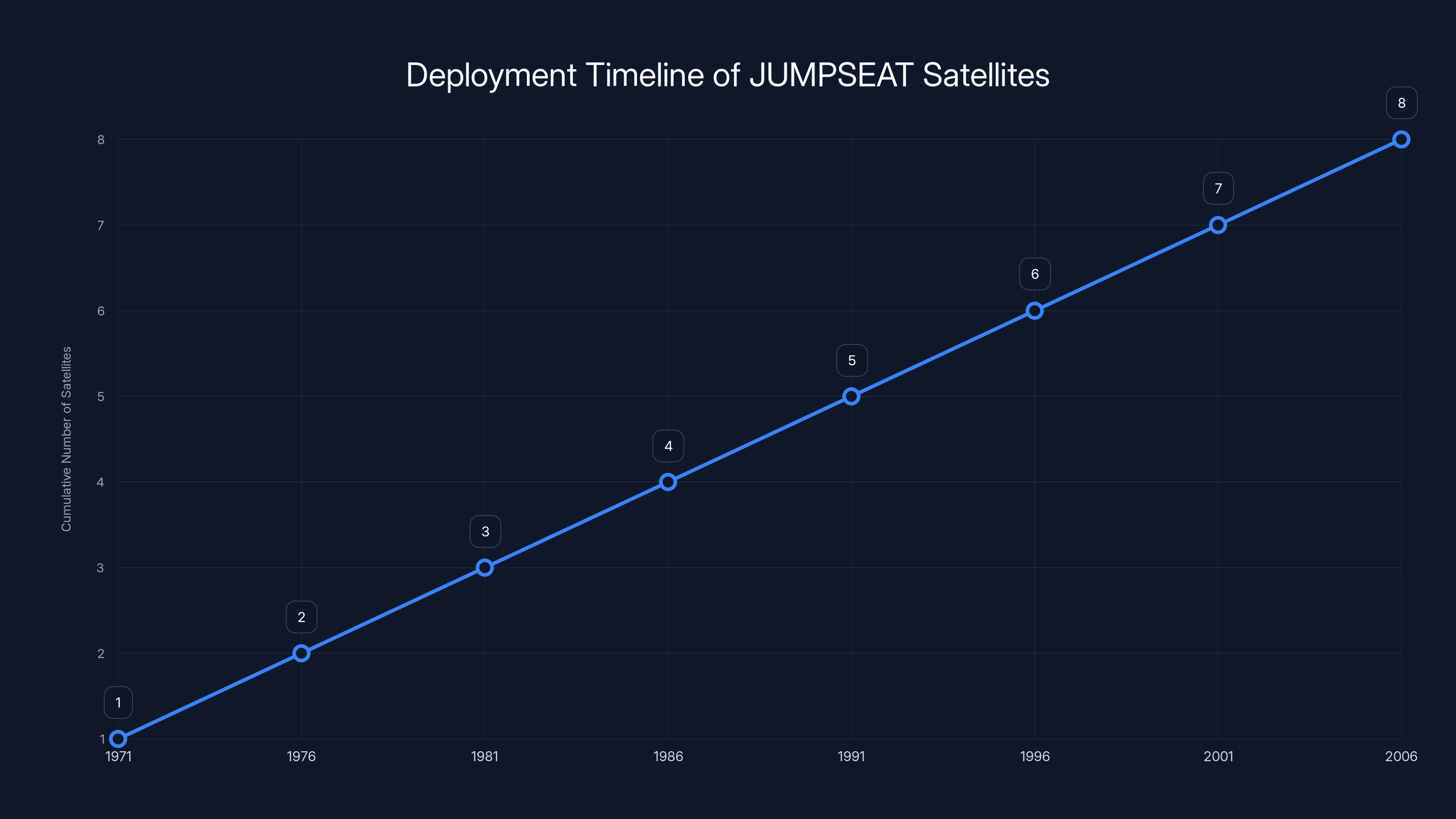

The story of JUMPSEAT isn't just about technology. It's about innovation born from necessity, the chess match between superpowers during the height of nuclear tensions, and the relentless ingenuity of engineers who pushed the boundaries of what satellites could accomplish. For over three decades, from 1971 through 2006, eight JUMPSEAT satellites orbited the Earth in ways that seemed almost magical. They could hover over the Arctic for hours, intercepting radio signals from Soviet military installations while remaining practically invisible to traditional tracking methods.

What makes this declassification significant now is the context. In 2025, as space surveillance capabilities have become increasingly sophisticated and the global spotlight turns to satellite reconnaissance, understanding how the Cold War intelligence community developed signals intelligence satellites offers crucial lessons. The technical achievements of JUMPSEAT set the template for modern space-based eavesdropping. The orbital mechanics pioneered for JUMPSEAT influence how satellites are positioned today.

But here's what's truly remarkable: the JUMPSEAT program was both remarkably successful and remarkably secretive. The journalist Seymour Hersh accidentally revealed its existence in 1986 through a book about the Korean Air Lines Flight 007 disaster. Yet even with that exposure, the American public knew almost nothing about how these satellites actually worked, what they looked like, or the full scope of their capabilities. The newly declassified documents and photographs finally fill those gaps.

This comprehensive guide explores everything we now know about JUMPSEAT: the orbital mechanics that made it possible, the technical specifications that set it apart, the signals it intercepted, and the lasting impact this program had on modern satellite reconnaissance. Whether you're interested in Cold War history, satellite technology, intelligence gathering, or the origins of modern space surveillance, JUMPSEAT represents a pivotal moment when the United States fundamentally changed how it conducted espionage.

TL; DR

- Eight JUMPSEAT satellites launched between 1971 and 1987, operating until 2006, representing America's first-generation highly elliptical orbit signals-collection spacecraft

- Highly elliptical orbits ranging from hundreds to 24,000 miles allowed satellites to loiter high over the Arctic and Soviet Union, providing persistent coverage for 12-hour orbital periods

- Primary mission focused on signals intelligence collection, monitoring Soviet weapon system development, communications, and early-warning systems across the northern hemisphere

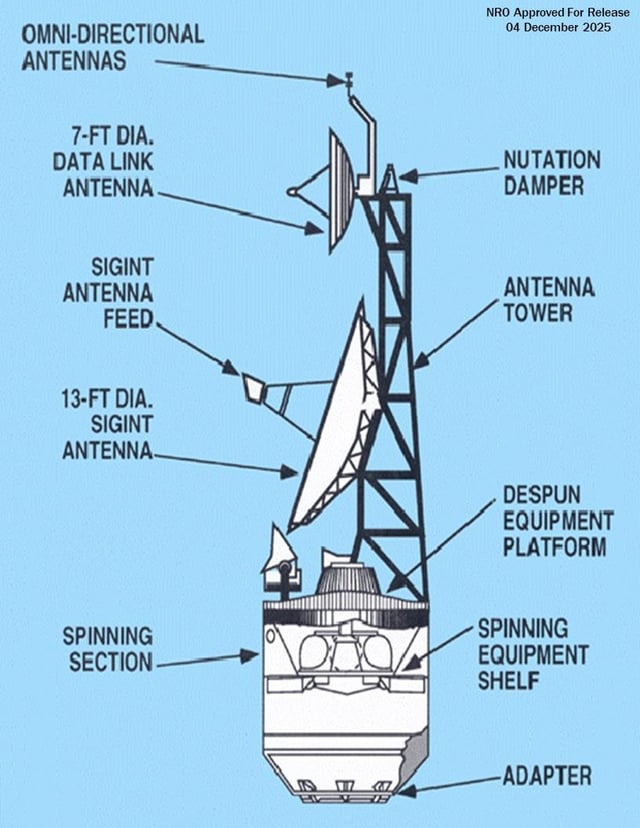

- Hughes Aircraft Company built the satellites using spin-stabilized design with 13-foot antennas for interception and 7-foot antennas for downlinking data to US ground stations

- The program remained classified until 2024, though journalist Seymour Hersh revealed its existence in 1986, demonstrating both the program's secrecy and the difficulty of keeping space operations truly hidden

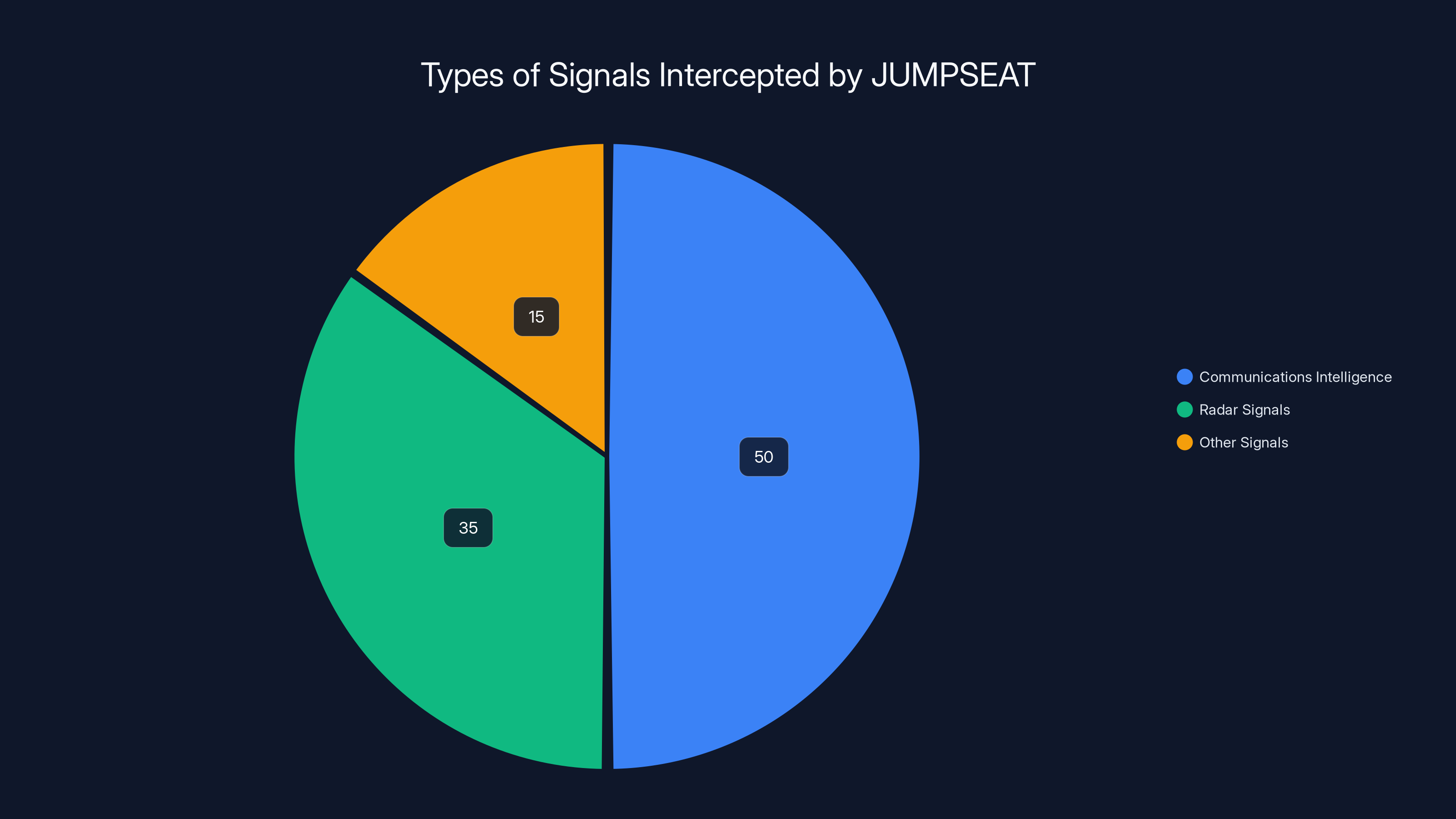

Communications intelligence made up the majority of signals intercepted by JUMPSEAT, followed by radar signals. Estimated data based on typical intelligence priorities.

The Architecture of Surveillance: Understanding Highly Elliptical Orbits

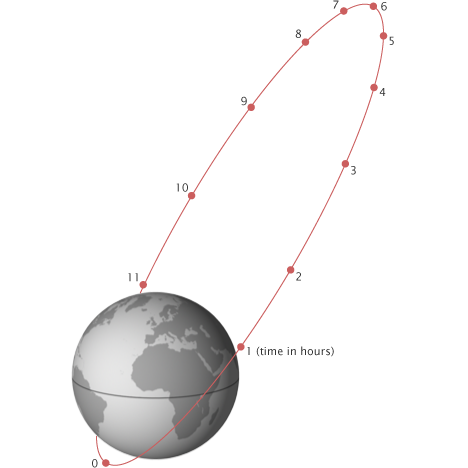

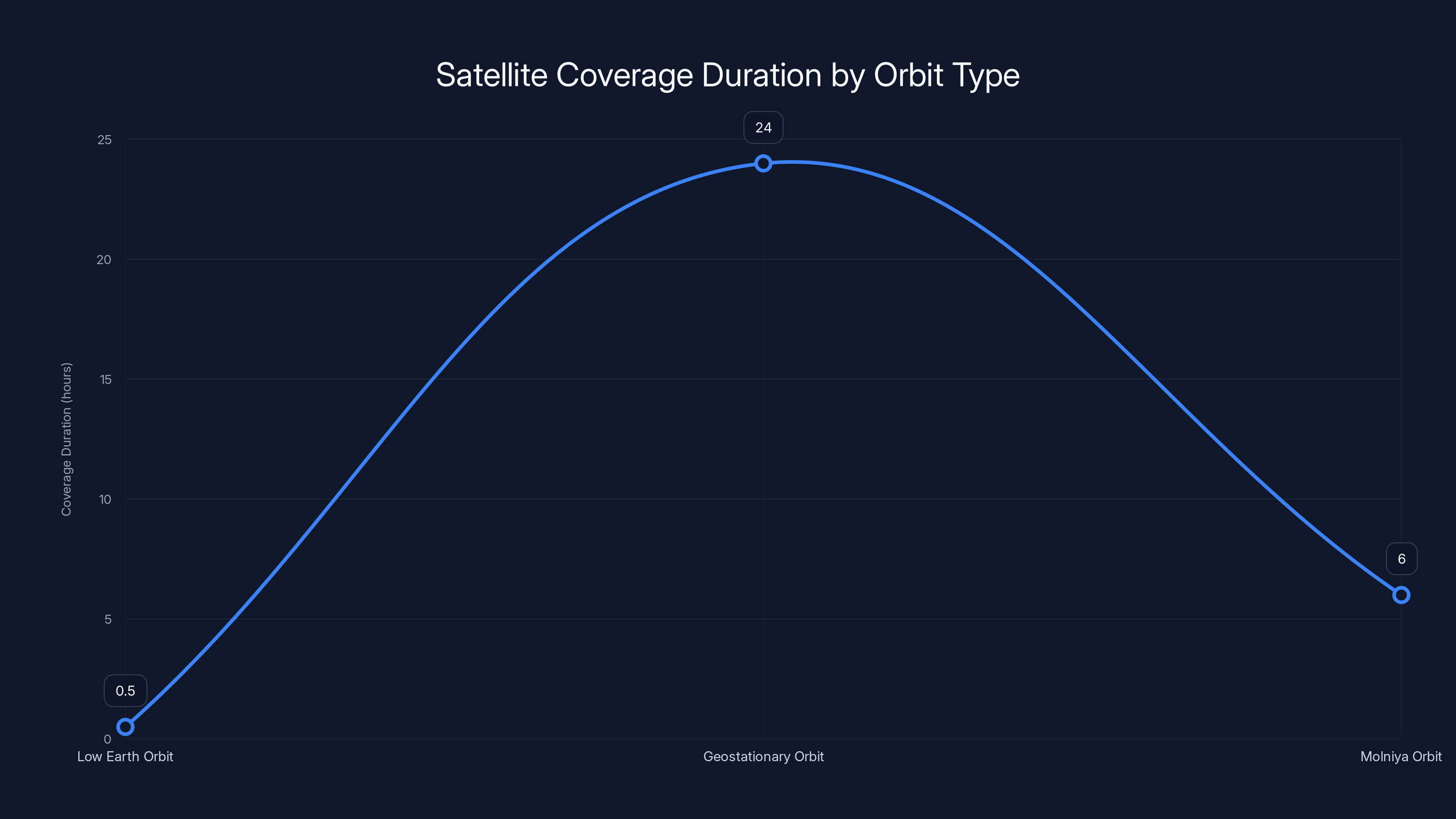

To grasp why JUMPSEAT was revolutionary, you need to understand the fundamental problem it solved. Traditional satellite orbits fall into two basic categories: low Earth orbit, where satellites circle the planet at altitudes of a few hundred miles, and geostationary orbit, where satellites sit fixed above a single point on the equator at 22,236 miles altitude.

Each approach has limitations. Low Earth orbit satellites move quickly over their targets but only pass over any given location briefly before racing toward the horizon. Geostationary orbit satellites offer continuous coverage from one location, but they're positioned over the equator, which means countries in far northern latitudes like the Soviet Union receive poor coverage. The coverage angle becomes progressively worse as you move toward the poles.

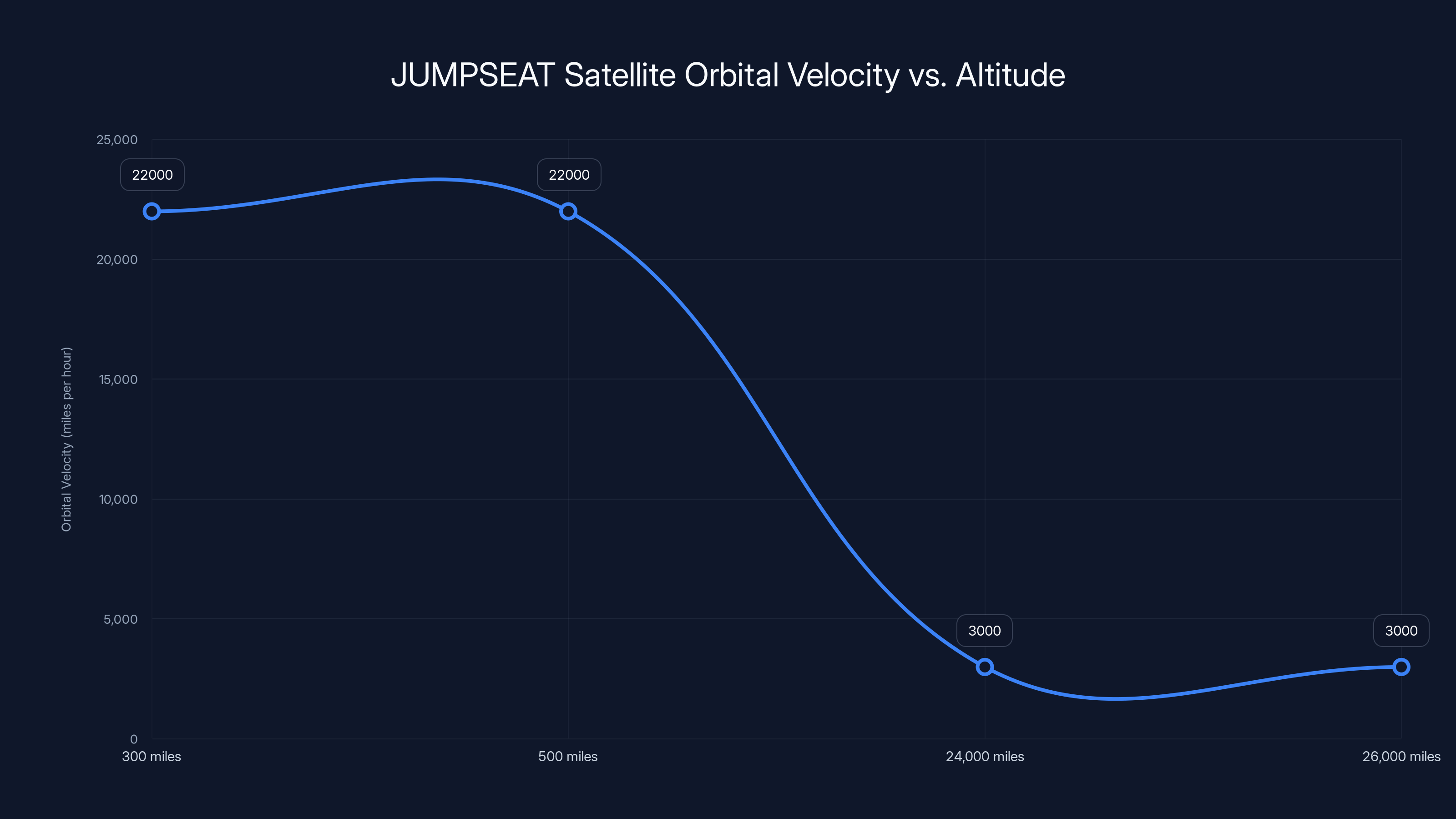

The Soviet Union discovered an elegant solution in the 1960s. They developed what became known as the Molniya orbit, named after the Russian word for lightning. In a highly elliptical orbit, a satellite rises from a low point called perigee a few hundred miles above Earth to an extremely high point called apogee at roughly 24,000 to 26,000 miles altitude. Here's the crucial physics principle that makes this work: satellites move slowest at apogee, their highest point, and fastest at perigee, their lowest point. This is a direct consequence of orbital mechanics and Kepler's laws of planetary motion.

When Soviet engineers designed the Molniya orbit with its specific dimensions, they positioned the apogee over the northern hemisphere. This meant their satellites would hang almost motionless in the sky for hours while directly overhead Russia, Canada, and the Arctic region. Then they'd rapidly descend through perigee and climb again on the other side of Earth. A complete orbit took twelve hours. By launching multiple satellites into similar orbits at different positions, the Soviets achieved continuous coverage over northern latitudes.

The mathematical elegance here cannot be overstated. The formula for orbital velocity at any point in an elliptical orbit follows from the vis-viva equation:

Where G is the gravitational constant, M is Earth's mass, r is the current distance from Earth's center, and a is the semi-major axis of the elliptical orbit. At apogee, r increases dramatically, making velocity extremely small. At perigee, r decreases, making velocity very high. This mathematical relationship meant that by positioning the apogee strategically, satellites could dwell over regions of interest.

The United States military and intelligence communities watched the Soviet Molniya satellites closely. They recognized immediately that this orbit provided a perfect platform for signals intelligence collection over the Soviet Union. Unlike visual reconnaissance satellites that needed clear skies and good lighting, signals intelligence satellites could operate anytime, day or night, in any weather, intercepting radio emissions and electronic signals.

When American engineers designed JUMPSEAT, they essentially adopted the same orbital approach but configured it specifically for intercepting electronic emissions. Eight satellites would launch into these highly elliptical orbits across the 1970s and 1980s. The total program cost remains classified, but developing an entirely new class of satellite with completely novel collection instruments required tremendous resources, technical expertise, and determination.

Molniya orbits provide extended coverage over high latitudes for up to 6 hours, bridging the gap between brief low Earth orbit passes and continuous geostationary coverage. Estimated data.

The JUMPSEAT Program Emerges: Origins and Development

The JUMPSEAT program emerged during a crucial period in Cold War signals intelligence operations. Throughout the 1960s, the United States had developed sophisticated ground-based signals intelligence collection facilities along the Soviet border, particularly in Turkey, Iran, and Pakistan. These ground stations could intercept Soviet radio transmissions, radar signals, and electronic communications. However, they suffered from a critical limitation: they could only collect signals from transmitters visible from their ground locations. Large areas of the Soviet Union remained beyond their reach.

Space-based signals intelligence collection offered a potential solution. Satellites could be positioned to intercept signals from anywhere on Earth, uncontested by borders or geography. By the late 1960s, the National Reconnaissance Office was evaluating how to build such a system. The success of Soviet Molniya satellites demonstrated that the highly elliptical orbit could work effectively. American engineers proposed adapting this concept for signals intelligence gathering.

The program's development faced significant technical challenges. Building a satellite to intercept radio signals required creating enormous antennas capable of picking up faint electromagnetic transmissions from thousands of miles away. The satellites needed to process and store vast amounts of intercepted data, then downlink it to ground stations. All this had to be accomplished in space, where reliability was paramount and repairs were impossible.

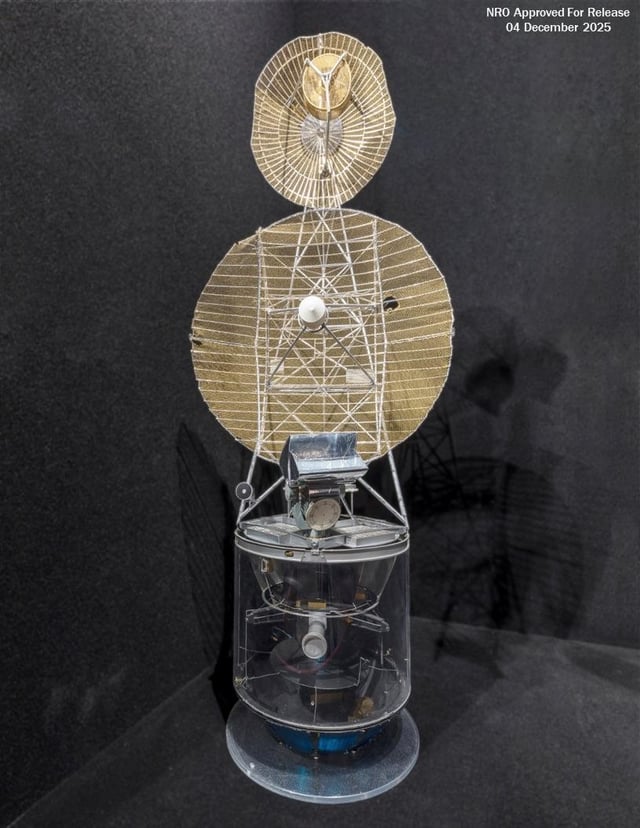

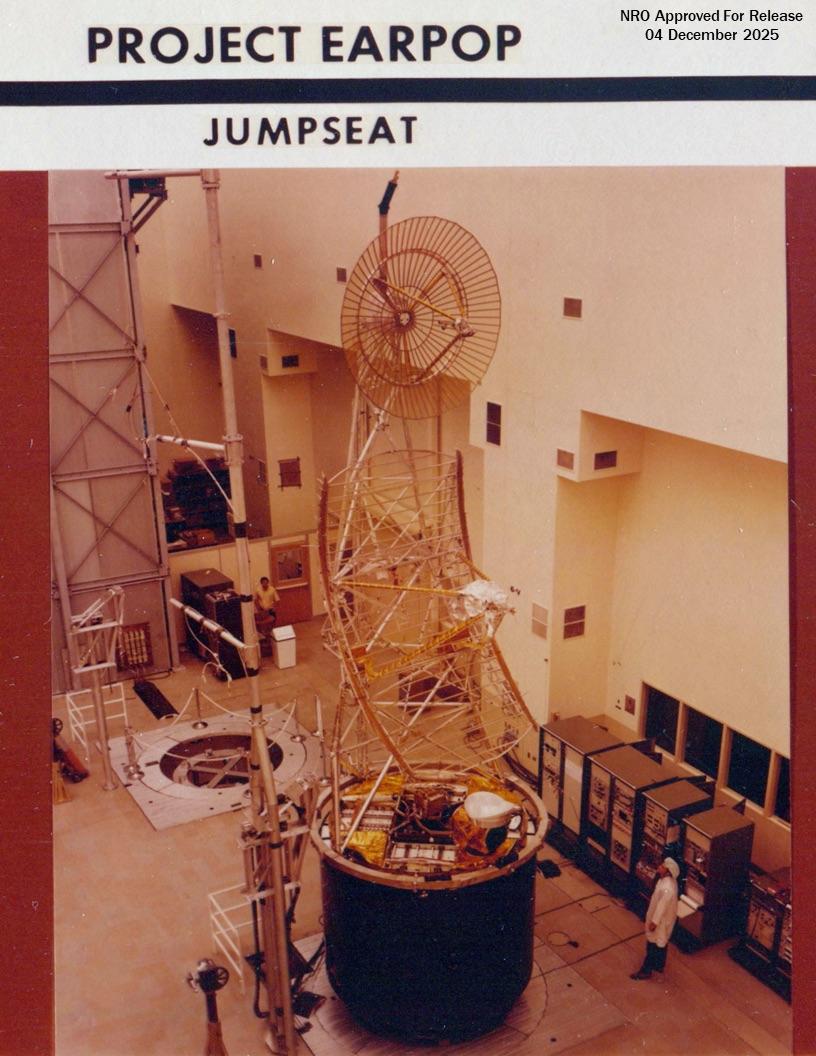

Hughes Aircraft Company won the contract to build JUMPSEAT satellites. Hughes had extensive experience building communications satellites and reconnaissance spacecraft. The company's expertise in spin-stabilized satellite design proved particularly valuable. Unlike satellites that use solar panels and reaction wheels for stabilization and orientation, spin-stabilized satellites spin like a gyroscope, using angular momentum to maintain stability. This approach offered several advantages for JUMPSEAT: it was mechanically robust, used less electrical power, and allowed for the deployment of large, complex antenna structures.

The first JUMPSEAT satellite launched in June 1971 aboard a Titan III rocket. The launch was classified, and the satellite's existence remained unknown to the public for fifteen years. Subsequent JUMPSEAT satellites launched approximately every two years, with the eighth and final operational satellite launching in 1987. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the JUMPSEAT constellation provided continuous coverage of Soviet territory, intercepting an estimated 90 percent of Soviet communications that traveled through radio transmissions.

The program's security was extraordinarily tight. Only a few thousand people in the entire United States government knew about JUMPSEAT. Engineers working on the satellite itself were compartmentalized, knowing only their specific component rather than the overall system. The satellites themselves were nicknamed after jump seats in airplanes, a deliberately vague reference that provided no meaningful description of their actual function. This operational security held remarkably well until journalist Seymour Hersh's 1986 book on the Korean Air Lines Flight 007 disaster accidentally mentioned JUMPSEAT satellites.

Technical Specifications: What the Declassified Details Reveal

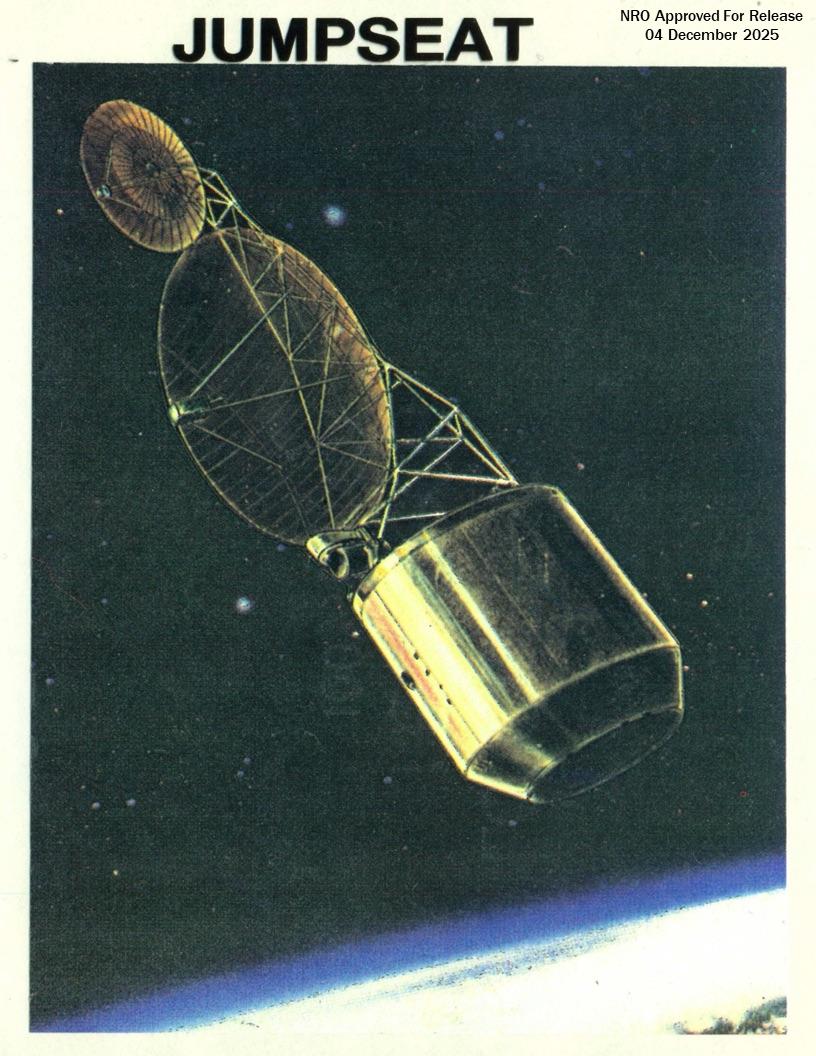

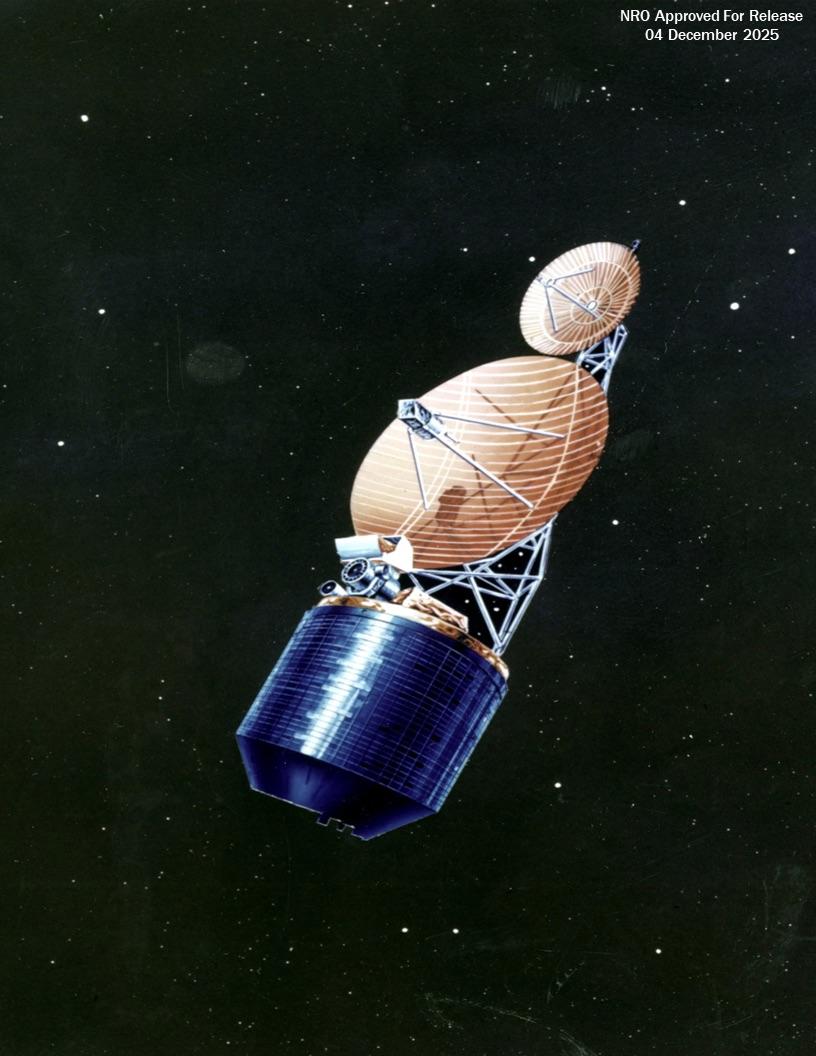

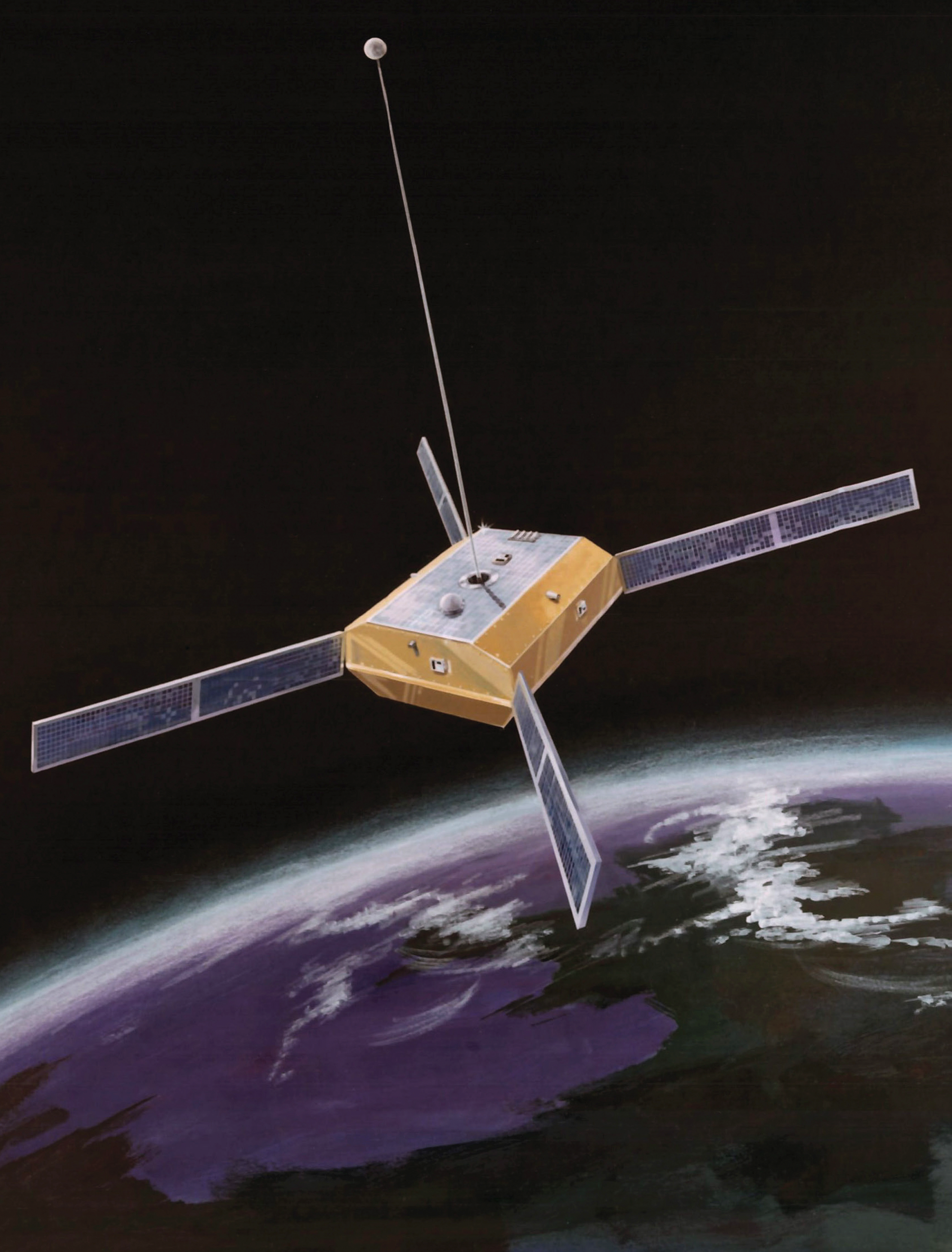

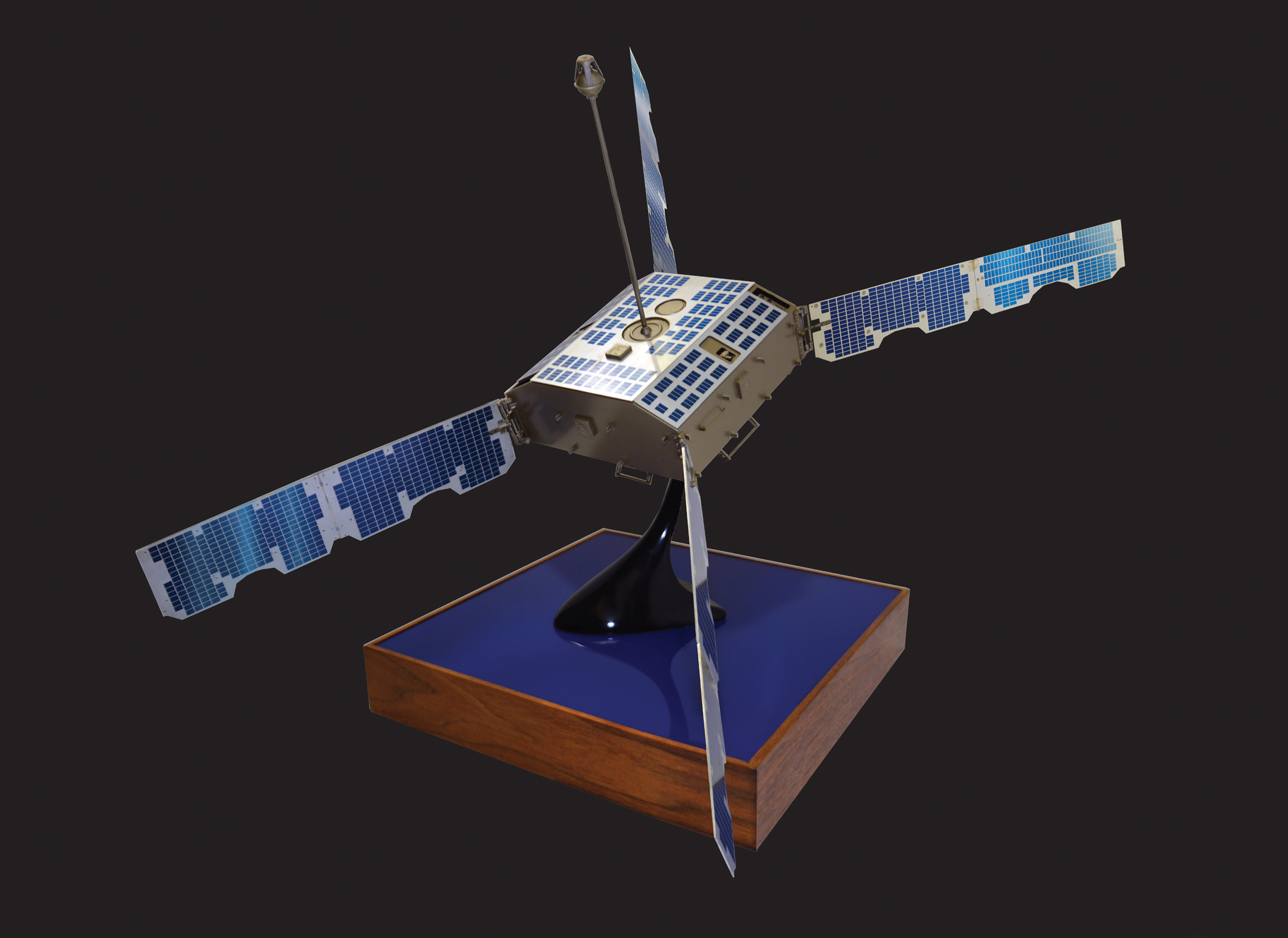

The National Reconnaissance Office's December 2024 declassification included previously unreleased photographs and technical specifications of JUMPSEAT satellites. These details offer a fascinating window into how 1970s-era engineers approached the problem of space-based signals intelligence collection.

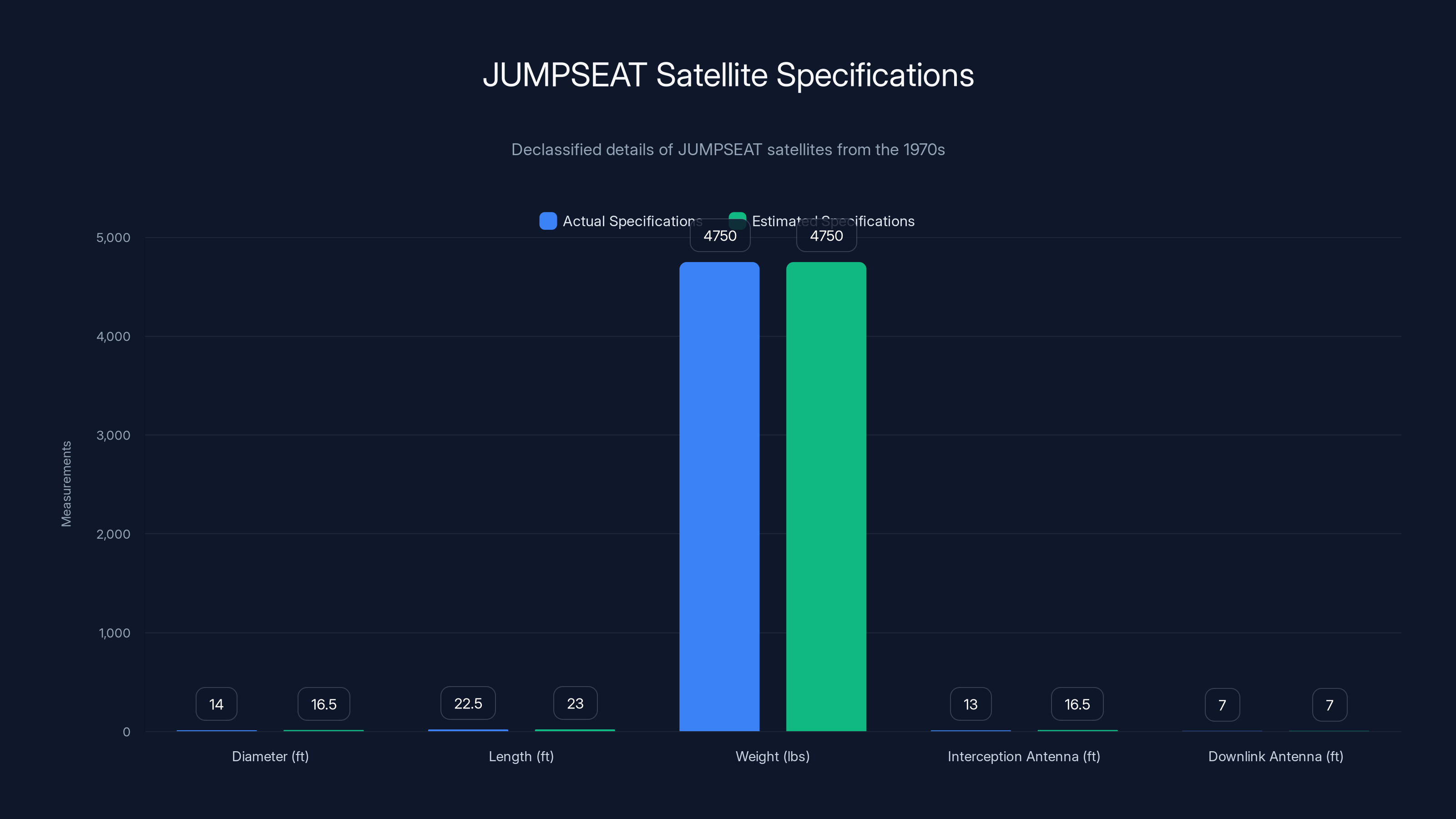

Physically, JUMPSEAT satellites resembled large spinning drums. This distinctive appearance reflected their spin-stabilized design. The satellites measured approximately 13 to 15 feet in diameter and extended roughly 20 to 25 feet in length. Solar panels wrapped around the cylindrical body, generating electrical power as the satellite rotated in sunlight. The total weight of each satellite at launch approached 4,500 to 5,000 pounds, making it a substantial payload for the Titan III launch vehicles that carried them to orbit.

The signature feature visible in declassified photos is the antenna system. Mounted on the upper deck of each satellite was a large 13-foot antenna designed specifically for intercepting foreign radio transmissions. This antenna could be oriented to point toward radio sources while the rest of the satellite continued its rotation. A despun platform, technically called a bias momentum device, allowed the antenna to remain pointed at targets even as the satellite's body spun. Additionally, satellites carried a smaller 7-foot antenna dedicated to downlinking intercepted data back to American ground stations.

These antenna specifications differed slightly from open-source estimates published by space historians before declassification. Some analysts had predicted the interception antenna might be even larger, perhaps 15 to 18 feet. The 13-foot dimension still represented extraordinary capability for intercepting weak radio signals from vast distances.

The internal payload represented the true technological marvel of JUMPSEAT. The satellites carried extremely sensitive receivers capable of detecting radio emissions from Soviet military transmitters, radar installations, and communication systems. These receivers had to overcome an enormous challenge: they needed to pick up signals that had traveled hundreds or thousands of miles through the atmosphere and space, arriving at the satellite with power levels measured in femtowatts (millionths of a billionth of a watt). Receivers of this sensitivity require extensive filtering and amplification, with multiple stages of signal processing to distinguish meaningful signals from background noise.

Data recording and storage systems allowed satellites to capture intercepted signals in real time. Earlier-generation signals intelligence satellites had transmitted data continuously to ground stations, but this approach limited coverage to areas where line-of-sight communication existed. JUMPSEAT satellites employed tape recorders, a groundbreaking approach for the time, allowing them to store signals during their long loiter over the target region, then downlink the data rapidly when positioned over friendly territory.

The satellites' power systems depended on large solar panel arrays. Providing adequate electrical power proved challenging, as JUMPSEAT's antenna and receiver systems consumed significant energy. The spin-stabilized configuration helped: slowly rotating satellites required less attitude control fuel than satellites using reaction wheels. Nevertheless, operational lifetime was limited. Most JUMPSEAT satellites operated for approximately five to seven years before their propellant reserves for orbit maintenance became depleted.

Heat management presented another significant engineering challenge. Satellite electronics generate considerable heat, but space is a vacuum with no medium for heat dissipation through convection. Engineers had to use radiator panels and heat pipes to transport thermal energy away from sensitive components. The spin-stabilized design helped here too, as rotation ensured even heat distribution around the satellite's surface.

The declassified specifications of JUMPSEAT satellites reveal a 13-foot interception antenna, contrary to previous estimates of 15-18 feet. Estimated data reflects prior assumptions.

The Orbital Dance: How JUMPSEAT Achieved Persistent Coverage

Understanding JUMPSEAT's operational effectiveness requires examining precisely how these satellites were positioned in their highly elliptical orbits. The specific orbital parameters directly determined coverage patterns, dwell time over targets, and collection opportunities.

JUMPSEAT satellites reached perigee altitudes between 300 and 500 miles above Earth. At this low point, they traveled at orbital velocities around 22,000 miles per hour. At apogee, approximately 24,000 to 26,000 miles altitude, orbital velocity dropped to roughly 3,000 miles per hour. The dramatic contrast in speed created the mission's core advantage: hours of slow, hovering coverage over the Arctic and Soviet Union.

Orbit inclination was set at approximately 65 degrees. This inclination determined the highest latitude the satellite could reach. With a 65-degree inclination, satellites could reach as far north as latitude 65 degrees North, covering much of Soviet territory, Canada, and the Arctic Ocean. The orbital plane was oriented so that apogee occurred when satellites passed over the northern hemisphere.

The orbital period of approximately 12 hours meant that JUMPSEAT satellites completed two orbits per day. By launching satellites into similar orbits but with timing offsets, the NRO achieved continuous coverage. While one satellite loitered over the Soviet Union at apogee, another would be accelerating toward perigee on the opposite side of Earth, and a third would be ascending from perigee toward apogee elsewhere in its orbit.

Ground stations positioned across North America, particularly in the United States and Canada, received downlinked data from JUMPSEAT satellites as they passed overhead. The locations of these ground stations remained classified, but space historians have identified probable facilities in places like Colorado, California, and various Canadian locations. High-speed data links transmitted the enormous volume of intercepted signals back to processing centers, where the National Security Agency and military intelligence agencies analyzed the collected information.

This persistent coverage represented a quantum leap forward for American signals intelligence operations. Instead of catching brief snapses of Soviet communications as satellites passed overhead, JUMPSEAT provided hours of continuous monitoring of specific regions. Ground-based direction-finding stations could work with JUMPSEAT data to triangulate signal sources, building detailed maps of Soviet transmitter locations and frequencies.

The operational tempo demanded coordination between multiple government agencies. The NRO operated the satellites themselves, managing orbital mechanics and data downlinks. The National Security Agency processed and analyzed intercepted communications. The Defense Intelligence Agency focused on military-related signals. Each agency had specific intelligence requirements, and JUMPSEAT had to be programmed to intercept signals from frequency bands relevant to their missions.

Signals Intelligence Collection: What JUMPSEAT Actually Intercepted

The declassified NRO documents describe JUMPSEAT's collection mission in carefully measured terms. The satellites collected "electronic emissions and signals, communication intelligence, as well as foreign instrumentation intelligence," according to the official description. These euphemistic terms mask the true scope of what JUMPSEAT accomplished.

Communications intelligence was the primary focus. Soviet military forces relied on radio communications for coordination between units, commands, and missile launches. Radio links connected air defense radars to command centers, allowing operators to share target information and coordinate intercepts. Tank units communicated with higher commanders via military radio networks. Aircraft-to-ground and ground-to-air communications carried vital information about flight operations, navigation, and targeting.

JUMPSEAT satellites intercepted these transmissions as they traveled through the atmosphere and space. Once received, signals could be recorded for later analysis. Analysts examined communication patterns, identified which units were transmitting, determined the approximate locations of transmitters, and analyzed the content of conversations. Over time, this information built a comprehensive picture of Soviet military operations, technological capabilities, and strategic intentions.

Radar signals represented a critical intelligence target. The Soviet Union deployed thousands of radar installations across its territory. These radars fell into several categories: air defense radars detecting aircraft, early-warning radars scanning for ballistic missile threats, and weapons control radars guiding anti-aircraft missiles to targets. Each radar type transmitted at specific frequencies, with characteristic signal patterns. JUMPSEAT could detect these transmissions from the orbiting platform. Direction-finding analysis combined with ground-based direction-finding stations allowed analysts to pinpoint radar locations with remarkable precision.

One specific focus mentioned in space historian accounts involved monitoring Soviet anti-ballistic missile systems. The Soviet Union had deployed the A-35 anti-ballistic missile system around Moscow, along with associated radar complexes. American military planners worried that this system might be more capable than publicly understood. JUMPSEAT satellites intercepted signals from these radars, revealing their operational characteristics and providing early warning if the system was activated. This information proved crucial for strategic force planning.

Missile test range signals represented another priority. The Soviet Union conducted frequent tests of new missiles at ranges in Central Asia and near the Arctic. Ground-based transmitters sent telemetry data from test missiles, reporting performance information to receiving stations. Radar systems tracked missile flight paths. JUMPSEAT could intercept both telemetry transmissions and radar signals, providing unprecedented visibility into Soviet missile development. This information allowed American intelligence agencies to monitor the progress of new Soviet weapons systems years before they entered operational service.

Voice communications presented a special challenge and opportunity. JUMPSEAT could intercept conversations between Soviet pilots and ground controllers, between missile commanders and launch facilities, between radar operators and air defense commanders. Early-generation collection systems didn't provide reliable automated translation, but Russian-speaking linguists could analyze intercepted conversations, identifying unit identifications, threat warnings, and tactical information.

Journal reports from operation specialists working with JUMPSEAT data indicated the program consistently collected signals from multiple Soviet military exercises. When the Soviet military conducted large-scale war games, radio traffic increased dramatically. Ground communications proliferated as units coordinated movements. JUMPSEAT satellites positioned at apogee could simultaneously monitor multiple regions of the Soviet Union, potentially tracking the exercise's progression across the country.

The program also intercepted signals from Soviet early-warning systems designed to detect American missile launches. These systems used specific radar frequencies and operated with known protocols. By monitoring them, JUMPSEAT could reveal when the Soviet early-warning network was operating, providing indicators of strategic force readiness. In a crisis situation, changes in early-warning radar activity could signal whether the Soviet military was entering a higher state of alert.

Declassified intelligence assessments from the 1970s and 1980s reveal that JUMPSEAT intercepts directly influenced American strategic force decisions. Signals showing that Soviet early-warning systems were not actively scanning the skies might have influenced decisions about conducting certain military operations. Information about Soviet radar capabilities shaped American electronic warfare doctrine and equipment design.

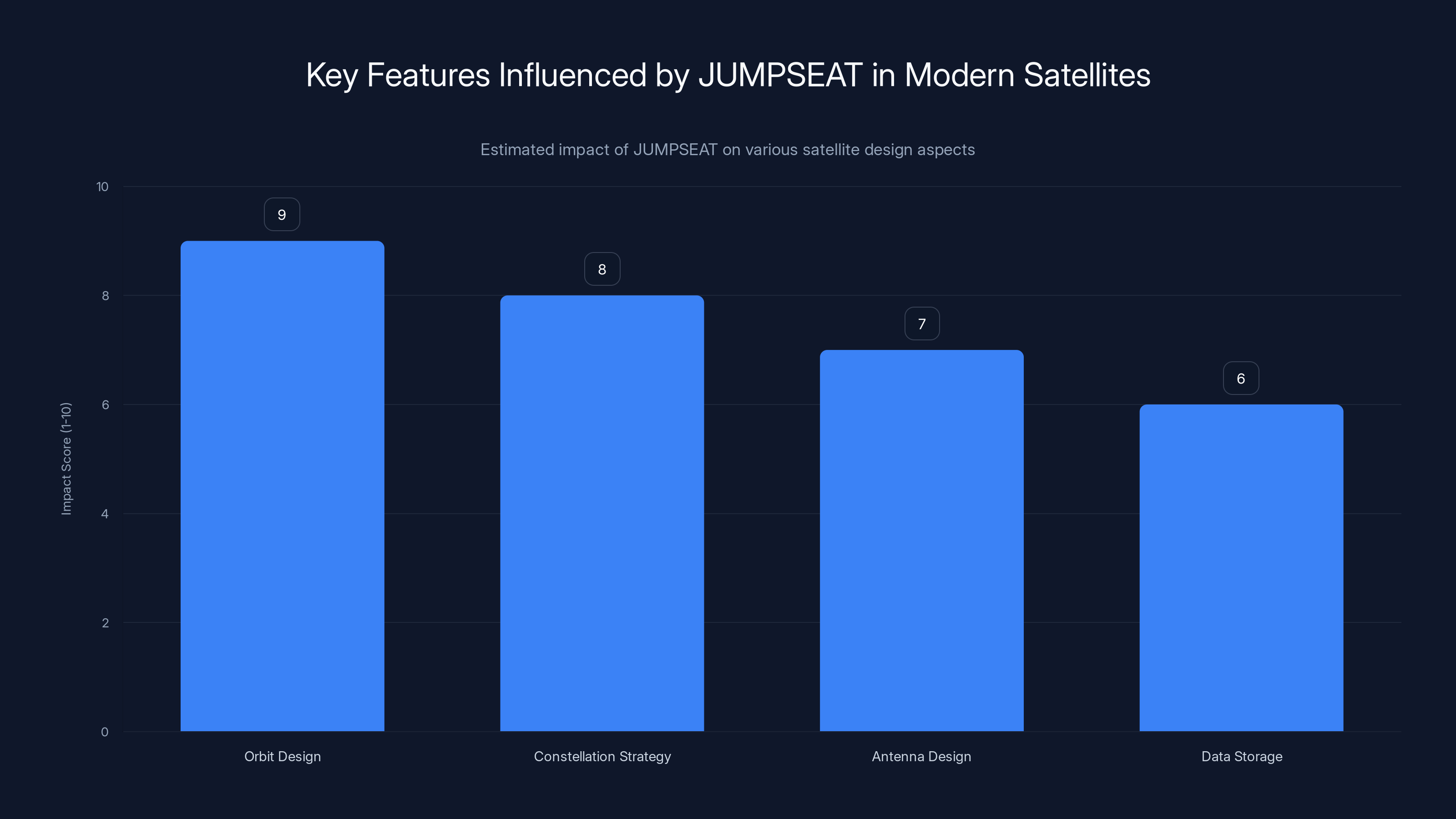

JUMPSEAT significantly influenced modern satellite design, especially in orbit design and constellation strategy. Estimated data.

The Soviet Response: Detecting the Invisible

Despite the program's extraordinary secrecy, the Soviet Union eventually became aware that American satellites operated in highly elliptical orbits. This awareness came not from discovering classified American programs but from observing where American satellites were positioned in space.

Soviet ground-based radar installations, particularly at Krasnoyarsk and other locations, tracked satellites in orbit. While they might not have known the specific purpose of satellites in highly elliptical orbits, Soviet strategic planners recognized the pattern: American satellites loitered over Soviet territory at apogee, remaining in view for hours at a time. This was consistent with signals intelligence collection.

The Soviet response took several forms. First, the military increased reliance on landline communications for sensitive transmissions. Instead of radio links, critical communications traveled through buried telephone cables that satellites couldn't intercept. This shift improved security but reduced operational flexibility, as field units couldn't communicate as readily with higher commands.

Second, Soviet military communications and radar operations employed greater operational security. Signals were encrypted more thoroughly. Radio operators used frequency-hopping techniques, rapidly changing frequencies to avoid direction-finding. Messages were kept brief. Transmitter locations were changed frequently to prevent adversaries from locating and targeting them.

Third, the Soviet Union deployed electronic warfare measures designed to degrade American collection. Radar signals were modulated with coding that made analysis more difficult. Intentional interference was introduced into communications bands to obscure legitimate traffic. These countermeasures increased the challenge for American analysts processing JUMPSEAT intercepts.

Despite Soviet countermeasures, JUMPSEAT remained extraordinarily valuable throughout its operational lifetime. The volume of intelligence it collected exceeded what ground-based systems alone could provide. Even encrypted or protected signals revealed patterns, frequencies, and operational activity. The combination of JUMPSEAT signals intelligence with other collection methods provided American planners with detailed understanding of Soviet military capabilities and intentions.

JUMPSEAT's Impact on Modern Signals Intelligence Satellite Design

The JUMPSEAT program established design principles and operational concepts that continue influencing signals intelligence satellite development today. Although satellites have become dramatically more sophisticated since 1971, fundamental concepts remain unchanged.

The highly elliptical orbit itself proved so effective that modern signals intelligence satellites operated by the United States, Russia, and allied nations continue using variations of this orbit. The extreme dwell time at apogee remains unmatched by any other orbit for achieving persistent coverage over specific regions. Modern Russian Luch satellites operate in Molniya-type orbits providing communications relay and signals intelligence collection. Advanced American signals intelligence satellites operated for the National Reconnaissance Office employ various orbital configurations, including highly elliptical orbits for some collection missions.

JUMPSEAT's emphasis on multiple-satellite constellations established a model for reliable, continuous coverage. Rather than relying on a single satellite that could be lost to failure, spreading intelligence collection across several platforms in carefully timed orbits ensures that even if one satellite fails, collection continues. Modern constellations built by commercial operators and governments alike follow this principle.

The antenna designs pioneered for JUMPSEAT influenced subsequent signals intelligence satellites. Large despun antenna platforms capable of precise orientation became standard in signals intelligence satellite design. The 13-foot JUMPSEAT antenna established that extremely large antenna structures were feasible in space. Subsequent satellites incorporated ever-larger antennas for even greater sensitivity.

Data storage using tape recorders gave way to solid-state systems, but the principle remained: satellites should record intercepted signals for later transmission rather than requiring real-time downlinks. This approach allows collection over regions where ground stations aren't available and provides flexibility in managing the enormous data volumes that modern satellites generate.

Signals processing techniques developed for JUMPSEAT established patterns followed by modern systems. Identifying and separating meaningful signals from background noise, performing direction-finding analysis, and correlating signals from multiple satellites all began with JUMPSEAT operations. Modern satellites employ artificial intelligence and machine learning for signal classification, but the fundamental approach traces to early programs like JUMPSEAT.

The JUMPSEAT program deployed eight satellites over 35 years, enhancing intelligence capabilities during the Cold War. (Estimated data)

The Declassification Decision and Its Implications

The December 2024 declassification decision represented a significant shift in how the American government manages Cold War history. Chris Scolese, director of the National Reconnaissance Office, personally approved the release, citing both historical significance and the principle that former intelligence programs should eventually be revealed to the public.

Scolese's declassification memorandum explained the reasoning: publicly acknowledging limited facts about JUMPSEAT would not cause harm to current or future satellite systems. The program had ended operations in 2006. The fundamental principles of signals intelligence satellite design were well understood internationally. No active American systems would be compromised by revealing JUMPSEAT details.

The declassification also reflected changing attitudes toward Cold War transparency. The Cold War itself ended over three decades ago. The Soviet Union dissolved in 1991. Many individuals who worked on JUMPSEAT had retired or passed away. Continuing to classify historical information about a program that younger generations of intelligence professionals might benefit from understanding made less sense than maintaining absolute secrecy.

However, the declassification was carefully limited. The NRO did not release detailed technical specifications of antenna design, receiver sensitivity, or signal processing algorithms. The locations of ground stations receiving JUMPSEAT data remained classified. The specific frequencies monitored and the protocols for operations were not disclosed. The agency released "certain limited facts," carefully bounded to provide historical context without revealing operational details that could inform current adversaries or benefit foreign intelligence services.

Space historians and intelligence analysts welcomed the declassification as a significant step toward better understanding Cold War space operations. The historian Dwayne Day, who has written extensively about reconnaissance satellites, noted that the declassified photos and specifications solved decades-old questions about JUMPSEAT's appearance and basic capabilities.

The declassification decision also reflected recognition that commercial and international developments had changed the intelligence landscape. Commercial satellite operators now deploy signals intelligence satellites with publicly discussed capabilities rivaling or exceeding classified American systems. Sophisticated amateur radio operators can intercept and analyze satellite signals. Maintaining absolute secrecy about a 1970s-era program became less defensible when modern commercial competitors operated openly.

Looking forward, Scolese indicated that the NRO would "evaluate a more complete declassification for the JUMPSEAT program as time and resources permit." This suggests that additional details about JUMPSEAT may eventually be released, perhaps including more technical specifications or operational history. Whether this will include information about other highly elliptical orbit signals intelligence satellites remained unaddressed.

Comparing JUMPSEAT to Competing Soviet Systems

While JUMPSEAT represented American signals intelligence collection capabilities, the Soviet Union developed parallel programs aimed at collecting intelligence about American and allied military activities. Understanding Soviet capabilities provides context for recognizing that the space-based intelligence competition was genuinely bilateral.

The Soviet Union operated signals intelligence satellites in highly elliptical orbits, using the same Molniya-type orbits that JUMPSEAT utilized. These Soviet satellites, known by various designations including Prognoz and other names, intercepted American military communications, radar signals, and transmissions from allied nations. Soviet satellites could monitor American early-warning radars, intercept military communications from bases, and track strategic force activity.

Soviet signals intelligence satellites were generally smaller and less sophisticated than JUMPSEAT. The Soviet space program prioritized launches above perfection, sometimes accepting somewhat lower performance to achieve rapid deployment. Soviet satellites often had shorter operational lifespans and required more frequent replacement.

However, Soviet operational discipline and multiple satellite deployments compensated for less sophisticated individual satellites. By the 1980s, the Soviet Union maintained multiple signals intelligence satellites in orbit at any given time, ensuring continuous coverage of regions of interest. The combination of persistent coverage, even with less sensitive collection equipment, provided intelligence value.

The competition between American and Soviet space-based intelligence systems represented a crucial dimension of Cold War military competition. Each side sought technological advantage through satellite reconnaissance, signals intelligence, and early warning systems. The space race that captured public attention with Moon landings and Space Shuttle flights had a deeply classified parallel in military space operations. JUMPSEAT represented one side of this competition; understanding Soviet parallel programs provides balanced perspective.

JUMPSEAT satellites exhibit significant velocity changes, from 22,000 mph at perigee (300-500 miles) to 3,000 mph at apogee (24,000-26,000 miles), enabling prolonged coverage over target areas.

JUMPSEAT's Operational Challenges and Technical Evolution

Operated across nearly four decades, JUMPSEAT satellites encountered numerous challenges that drove continuous technical evolution. Understanding these problems illuminates how space systems must evolve to remain effective in contested environments.

Power generation remained a persistent challenge. Solar panels degraded over time, reducing power output. Early JUMPSEAT satellites suffered more significant power degradation than later models, as solar cell technology improved. Engineers developed mitigation strategies, including battery systems that stored power during eclipse periods and optimized power management to extend satellite lifespans.

Antenna performance presented unforeseen challenges. Large antenna structures in the space environment encountered vibration, thermal expansion and contraction, and occasional structural degradation. Some JUMPSEAT satellites experienced antenna misalignment issues that reduced collection effectiveness. Ground controllers could sometimes command antenna adjustments, but the satellites lacked full fine-tuning capability.

Data link reliability required constant attention. The downlink from JUMPSEAT satellites to ground stations used powerful transmitters and sensitive ground station receivers. However, propagation effects, solar activity, and occasional equipment failures caused data loss. Engineers developed error correction coding and redundant transmission schemes to compensate.

The Soviet Union's growing awareness of JUMPSEAT operations prompted operational changes. Earlier JUMPSEAT missions operated with relative freedom, intercepting signals from Soviet military exercises and routine operations. As the Soviets recognized their signals were being collected, they implemented better operational security, changed procedures, and employed countermeasures. Later JUMPSEAT satellites required more sophisticated signal processing to accomplish their missions as Soviet secrecy improved.

JUMPSEAT satellites also had to contend with natural space environment hazards. Solar particle events occasionally damaged satellite electronics. Micrometeorite impacts, while rare, occasionally affected satellites. Radiation in the space environment caused gradual degradation of sensitive components. Modern satellites employ shielding and radiation-hardened electronics to mitigate these hazards, but JUMPSEAT-era technology was less protected.

Financial pressures occasionally threatened the program. Defense budgets tightened during certain periods, leading to delays in launching replacement satellites. When JUMPSEAT satellites reached the end of their operational lifespans, replacement missions had to be prepared to ensure uninterrupted coverage. The NRO had to balance JUMPSEAT's continued value against competing priorities for reconnaissance satellites, early-warning satellites, and communications satellites.

The Transition Era: JUMPSEAT's Later Years and Succession

As the 1990s progressed, JUMPSEAT satellites gradually retired from operations. The last JUMPSEAT satellites ceased operations around 2006. By this point, technology had advanced dramatically since the first JUMPSEAT launch in 1971. What had been revolutionary in the early 1970s seemed archaic by the early 2000s.

Before JUMPSEAT's complete retirement, the NRO had begun deploying successor signals intelligence satellites. The advanced Orion system (known by various designations) took over many of JUMPSEAT's missions. Advanced Orion satellites operated in different orbits, sometimes in highly elliptical orbits for some missions and in other configurations for other collection requirements. The newer satellites offered improved antenna technology, more sensitive receivers, and sophisticated digital signal processing.

However, some JUMPSEAT satellites remained in operation far longer than originally anticipated. As operational lifespans exceeded initial predictions, the NRO sometimes kept older satellites operating in secondary roles to maintain continuous coverage while waiting for newer satellites to achieve operational capability. The redundancy and longevity of some JUMPSEAT satellites provided valuable insurance against gaps in signals intelligence coverage.

The transition from JUMPSEAT to successor systems reflected both technological progress and changing strategic requirements. By the 1990s, the Soviet Union had collapsed. The primary target of Cold War signals intelligence operations no longer existed. Russia remained a potential adversary, but the scale of the intelligence requirements changed fundamentally.

Newer signals intelligence satellites were designed for more diverse collection requirements: monitoring terrorism, tracking rogue state weapons programs, and supporting allied military operations. The highly elliptical orbit remained valuable for coverage of specific regions, but it was no longer the primary platform for American signals intelligence collection from space.

Government budgets increasingly shifted toward other space-based systems. Early-warning satellites detecting ballistic missile launches became higher priority. Communications satellites supporting military operations worldwide received greater investment. Digital reconnaissance satellites with advanced imaging capabilities grew in significance. The discrete focus on one region that characterized JUMPSEAT gave way to globally responsive systems.

Intelligence Community Organization: Who Used JUMPSEAT

The intelligence information collected by JUMPSEAT satellites flowed through a complex organizational structure. Understanding who used JUMPSEAT data provides perspective on its strategic significance.

The National Security Agency (NSA) held primary responsibility for processing and analyzing signals intelligence. JUMPSEAT intercepts were transmitted to NSA facilities, where linguists, analysts, and signal processors worked to extract meaning from the collected data. The NSA's Fort Meade headquarters served as the central repository for signals intelligence analysis.

The Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) received processed signals intelligence for military applications. DIA analysts focused on Soviet military capabilities: weapons systems performance, unit readiness, operational tactics, and strategic intentions. JUMPSEAT signals provided raw material for the detailed military assessments that influenced American defense planning.

Military service intelligence branches maintained their own signals intelligence analysis. Navy intelligence focused on Soviet naval communications and radar signals. Air Force intelligence prioritized communications from Soviet air defense forces and aircraft. Army intelligence sought information about ground force capabilities and command and control systems. Each service intelligence organization operated under the overall NSA umbrella but maintained specialized analytical focus.

Central Intelligence Agency analysts received signals intelligence tailored to policy and strategic questions. CIA policymakers needed to understand Soviet leadership intentions, assess military morale and readiness, and evaluate the success of Soviet weapons programs. JUMPSEAT signals contributed to comprehensive intelligence assessments.

The National Reconnaissance Office itself retained portions of the JUMPSEAT raw data for technical analysis. NRO engineers studied how well the satellites performed, whether equipment operated as intended, and whether operational procedures produced optimal results. This technical feedback influenced satellite operations and informed design of successor systems.

Coordination between these organizations required secure communications networks and established protocols. The NSA coordinated with military intelligence organizations to ensure that processed signals intelligence reached users in appropriate classification and format. Requirements from military commanders and policy officials flowed back to the NRO, informing satellite operations priorities.

Allied intelligence services, particularly from the United Kingdom and Canada, received selected information from JUMPSEAT operations. The special relationship between American and allied intelligence services meant that important insights from signals intelligence were shared, subject to various security and diplomatic considerations. This sharing reinforced alliance relationships and improved collective intelligence about Soviet capabilities.

The compartmented nature of JUMPSEAT operations meant that information was highly restricted. Few individuals outside the signals intelligence community knew details about the program. This compartmentation protected both the program's secrecy and the individuals involved, limiting exposure if security breaches occurred.

Historical Significance: JUMPSEAT in the Broader Cold War Context

Placing JUMPSEAT in its historical context reveals its profound significance for Cold War strategy and the eventual American victory in that prolonged competition.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the Cold War involved intense strategic competition. The Soviet Union deployed new weapons systems: advanced fighter aircraft, improved surface-to-air missiles, modernized intercontinental ballistic missiles. American military planners faced the central question of all military competition: what exactly is the adversary's capability?

Traditional intelligence methods provided partial answers. Human intelligence agents in Soviet military establishments offered limited insight. Photographic reconnaissance satellites revealed weapons deployment and training activities. Electronic intelligence satellites detected radar and communication signals. But the complete picture remained frustratingly unclear. What was the actual performance of new Soviet weapons? How effective were their command and control systems? How ready was the Soviet military for large-scale operations?

JUMPSEAT provided critical pieces of this puzzle. Signals intelligence revealed the tempo of Soviet military operations, the frequency of training exercises, the technical characteristics of weapons systems through their electronic emissions, and the effectiveness of Soviet command and control. By intercepting communications from Soviet test ranges, American analysts could monitor weapons development progress. By monitoring radar transmissions, they could assess system performance. By listening to military exercises, they could evaluate tactical proficiency.

This intelligence shaped American strategy. If Soviet capabilities appeared more advanced than previously believed, American defense programs would accelerate. If capabilities seemed less impressive than feared, defense spending might shift to other priorities. The decision to deploy the B-1 bomber, to continue developing cruise missiles, to maintain strategic force readiness at particular levels—all these decisions incorporated intelligence estimates based partly on JUMPSEAT signals intelligence.

JUMPSEAT also supported strategic arms control. During negotiations for arms control treaties like the Strategic Arms Reduction Talks (START), American negotiators relied on intelligence about Soviet weapons capabilities. JUMPSEAT signals intelligence verified that the Soviet Union complied with agreed limitations. When inspecting weapons, negotiators asked how many missiles existed? JUMPSEAT intercepts of communications from Soviet military units provided the answer. How many missiles were deployed? Again, signals intelligence offered verification.

The deterrence relationship between superpowers depended partly on each side understanding the other's capabilities. Excessive uncertainty could provoke unnecessary arms buildups. JUMPSEAT helped reduce that uncertainty, providing American planners with confidence in their understanding of Soviet military capabilities. This reduced risk of destabilizing misperceptions.

As the Cold War wound toward conclusion in the late 1980s, JUMPSEAT signals provided evidence of the Soviet system's internal decay. Soviet military communications revealed declining readiness, shortages of spare parts, and morale problems. When the Soviet Union finally collapsed, American intelligence planners were not entirely surprised—JUMPSEAT had been providing warning signs for years.

JUMPSEAT's Legacy in Modern Intelligence Operations

Although JUMPSEAT satellites have retired from operations, their legacy profoundly influences modern intelligence practices and space operations.

The principle of persistent coverage over regions of strategic interest remains central to American intelligence operations. Modern signals intelligence satellites continue operating in highly elliptical orbits for specific missions. The National Reconnaissance Office operates sophisticated satellites that far exceed JUMPSEAT capabilities, yet they still loiter at apogee over regions of interest, just as JUMPSEAT did decades ago.

The concept of constellation operations—multiple satellites working together to provide continuous coverage—became standard for American space-based intelligence systems. JUMPSEAT pioneered the practical implementation of this concept. Modern intelligence satellite constellations owe intellectual debt to JUMPSEAT's operational model.

Direction-finding techniques developed during JUMPSEAT operations remain relevant for modern intelligence gathering. Identifying transmitter locations from signal characteristics, using signal arrival time differences and frequency analysis—these techniques developed in the JUMPSEAT era remain core skills for signals intelligence analysts today.

The integration of signals intelligence with photographic intelligence created a comprehensive picture of Soviet capabilities during the Cold War. This lesson—that multiple intelligence collection methods provide better insight than any single method—remains fundamental to modern intelligence operations. Modern intelligence agencies coordinate imagery, signals intelligence, human intelligence, and measurement and signatures intelligence to construct complete pictures of situations.

JUMPSEAT also demonstrated that operating sophisticated systems in space over long periods was feasible. Some JUMPSEAT satellites operated for decades, proving that reliability engineering could enable prolonged space operations. This lesson influenced subsequent satellite design, emphasizing reliability and longevity as critical requirements.

Modern commercial satellite operators have demonstrated capabilities paralleling JUMPSEAT's signals intelligence collection. Today, private companies operate signals intelligence satellites alongside military and government systems. These commercial developments would have been unimaginable during the Cold War when reconnaissance satellites were exclusively government domains. JUMPSEAT represented the cutting edge of intelligence capability; today, commercial operators offer similar services.

The declassification of JUMPSEAT in 2024 itself reflects a changing intelligence environment. Modern challenges—terrorism, cyber threats, space competitors—differ fundamentally from Cold War competition. Intelligence priority has shifted from monitoring a single superpower adversary to addressing diverse threats globally. In this context, protecting 50-year-old program details seems less critical than maintaining transparency about historical operations.

FAQ

What exactly was the JUMPSEAT program?

JUMPSEAT was a United States signals intelligence satellite program operated by the National Reconnaissance Office from 1971 to 2006. The program deployed eight satellites into highly elliptical orbits to intercept radio communications, radar signals, and electronic emissions from the Soviet Union and other targets. Designed and built by Hughes Aircraft Company, JUMPSEAT satellites represented America's first-generation highly elliptical orbit (HEO) signals-collection spacecraft and provided critical intelligence about Soviet military capabilities throughout the Cold War and beyond.

How did JUMPSEAT satellites maintain coverage over the Arctic and Soviet Union?

JUMPSEAT satellites used highly elliptical orbits (HEOs) that carried them from altitudes of a few hundred miles at perigee to approximately 24,000 miles at apogee. Due to orbital mechanics, satellites move slowest at their highest point (apogee), causing JUMPSEAT spacecraft to loiter nearly motionless over the Arctic and Soviet territory for extended periods during each 12-hour orbit. By deploying multiple satellites in similar orbits with staggered timing, the NRO achieved continuous coverage of critical regions where traditional circular orbits would only provide brief coverage windows.

What signals did JUMPSEAT intercept and why was this valuable?

JUMPSEAT intercepted communications between Soviet military units, radar signals from air defense and early-warning systems, telemetry from weapons tests, and electronic emissions from military installations. This signals intelligence was extraordinarily valuable because it revealed the Soviet military's capabilities, readiness, operational activity, and technological development—information that could not be obtained through other intelligence collection methods. American military planners used JUMPSEAT intelligence to assess threats, make defense decisions, and verify compliance with arms control agreements.

Why did the United States keep JUMPSEAT classified for so long?

Keeping JUMPSEAT classified protected the program's operational effectiveness. If the Soviet Union had known precisely how American satellites were positioned and what signals they could intercept, military commanders could have implemented better countermeasures, changed communication procedures, and employed more sophisticated operational security. Revealing collection methods and capabilities would have allowed adversaries to develop defenses. Only after the program ended operations in 2006 and technology evolved significantly beyond JUMPSEAT's capabilities did declassification become feasible without compromising current intelligence operations.

How did Soviet Molniya orbits relate to JUMPSEAT?

The Soviet Union pioneered the highly elliptical orbit, called Molniya (Russian for "lightning"), in the 1960s for their own communications and military satellites. American engineers recognized this orbit's advantages for signals intelligence collection, as satellites could loiter over northern regions like the Soviet Union for extended periods. JUMPSEAT essentially adapted the Soviet innovation for American signals intelligence purposes, using similar orbital characteristics but with a completely different mission and collection payload. This demonstrates how space competition drove innovation on both sides.

What happened to JUMPSEAT's successor satellites?

Before JUMPSEAT satellites completely retired around 2006, the National Reconnaissance Office deployed more advanced signals intelligence satellites to assume collection responsibilities. The Advanced Orion system, known by various designations, succeeded JUMPSEAT with superior capabilities: more sensitive receivers, larger antennas, more sophisticated signal processing, and improved data handling. Modern American signals intelligence satellites continue operating in various orbits, including highly elliptical orbits for some collection missions, but individual systems are far more specialized and advanced than the general-purpose JUMPSEAT design.

Why did the National Reconnaissance Office declassify JUMPSEAT in 2024?

NRO Director Chris Scolese approved the declassification because the program ended operations nearly 20 years earlier, knowledge of the program's general capabilities was already public through publications and historical research, and revealing limited facts would not compromise current or future satellite systems. Additionally, the declassification reflected principles established by executive order regarding appropriate timelines for releasing historical intelligence information. The decision also recognized that Cold War space programs merit historical transparency now that the competition itself has ended and many individuals involved have retired or passed away.

How did JUMPSEAT influence the design of modern signals intelligence satellites?

JUMPSEAT established fundamental design principles still employed today: using highly elliptical orbits for persistent regional coverage, deploying multiple satellites in constellation operations to ensure continuous coverage, designing large despun antenna platforms for precise signal interception, and implementing onboard data storage rather than requiring real-time downlinks. The satellite's spin-stabilized design proved robust and efficient, influencing subsequent satellite designs. Modern signals intelligence satellites use more advanced technology but follow design philosophy and operational concepts pioneered by JUMPSEAT.

What role did JUMPSEAT play in Cold War arms control verification?

JUMPSEAT signals intelligence provided critical verification capabilities for arms control treaties between the United States and Soviet Union. Intercepted communications from Soviet military units allowed verification that the Soviet Union was complying with agreed limitations on weapons deployments. Intelligence about Soviet weapons testing helped American negotiators understand actual capabilities and make informed decisions about acceptable treaty limits. JUMPSEAT intercepts of Soviet command and control communications provided confidence that the Soviet military was implementing treaty provisions, reducing uncertainty and supporting strategic stability.

Conclusion: From Classified Mystery to Historical Record

The declassification of JUMPSEAT in December 2024 marked a significant transition in how the American government addresses its Cold War space heritage. What had been one of the most closely guarded secrets in the intelligence community—the capabilities and specifications of America's first-generation highly elliptical orbit signals intelligence satellites—became historical record available for scholarly examination and public understanding.

The JUMPSEAT story encompasses multiple fascinating dimensions. Technically, the program represented a bold adaptation of Soviet orbital concepts for American intelligence purposes, pushing the boundaries of what satellites could accomplish in the early 1970s. Eight Hughes-built satellites, distinguished by their large antennas and spin-stabilized design, loitered over the Arctic and Soviet Union for decades, intercepting radio communications, radar signals, and electronic emissions that provided American military planners with crucial understanding of Soviet capabilities.

Strategically, JUMPSEAT contributed significantly to American Cold War success. The intelligence it provided informed defense spending decisions, supported arms control verification, and helped reduce dangerous uncertainties about Soviet military capabilities. When Soviet leadership eventually recognized that American satellites were eavesdropping on military communications, they implemented countermeasures, but JUMPSEAT's contribution to American strategic knowledge was already substantial.

Operationally, JUMPSEAT demonstrated that sophisticated space-based intelligence collection systems could operate reliably for decades, providing continuous value across changing political circumstances. The program's three-plus-decade operational span from 1971 to 2006 testified to the robustness of Hughes' satellite design and the ongoing relevance of its capabilities even as technology evolved around it.

The program also illustrates broader principles about intelligence community organization and space operations. JUMPSEAT data flowed through complex organizational structures connecting the National Reconnaissance Office, National Security Agency, Defense Intelligence Agency, and military service intelligence branches. The program demonstrated the necessity of sustained investment in multiple collection systems to provide comprehensive intelligence. And it showed how technological innovation in space could support strategic national security objectives.

Looking forward, JUMPSEAT's legacy continues shaping American intelligence operations. The operational concepts pioneered by JUMPSEAT—constellation operations, persistent coverage over regions of strategic interest, integration with other intelligence collection methods—remain relevant for modern challenges. The technical principles embodied in JUMPSEAT design influenced subsequent satellite systems that continue serving American intelligence requirements today.

The declassification decision itself reflects recognition that intelligence transparency about historical programs can be balanced with security requirements for current operations. JUMPSEAT secrets that would have endangered active operations in 1980 no longer pose security threats in 2025. Allowing scholars, historians, and the public to understand how America conducted space-based intelligence collection during the Cold War serves the national interest by providing historical education without compromising current capabilities.

JUMPSEAT stands as a remarkable achievement in space technology, intelligence operations, and military innovation. The newly declassified photographs and specifications finally allow detailed appreciation of what these spacecraft accomplished. For space historians and intelligence analysts, the declassification resolves decades of speculation about JUMPSEAT's appearance and basic specifications. For policy professionals and military strategists, understanding JUMPSEAT provides perspective on how space-based intelligence collection evolved and how such systems support national security.

As the United States, Russia, China, and other nations continue developing more advanced space-based intelligence systems, understanding JUMPSEAT provides historical context for appreciating how space operations have become increasingly sophisticated. The satellite that seemed so advanced in 1971 operated until 2006, and its technical descendants continue serving intelligence requirements today. That remarkable longevity testifies to the fundamental soundness of Hughes' engineering and to the enduring value of the operational concepts JUMPSEAT pioneered.

The JUMPSEAT declassification also represents a watershed moment in Cold War historical documentation. As more Cold War programs gradually become declassified, a clearer picture emerges of how intensely the intelligence and military communities worked to understand Soviet capabilities. JUMPSEAT was just one component of a vast intelligence collection enterprise, but one with particular technological elegance and strategic significance. Understanding JUMPSEAT helps explain how American national security professionals navigated the uncertain strategic landscape of the Cold War and made decisions that ultimately contributed to American strategic success.

For those interested in space technology, Cold War history, intelligence operations, or strategic policy, JUMPSEAT offers rich material for study. The technical specifications reveal how engineers solved difficult problems with 1970s-era technology. The operational history demonstrates how intelligence satellites contribute to national security. The declassification decision itself illustrates principles of governmental transparency and historical documentation.

As we look toward future space competition and intelligence challenges, JUMPSEAT reminds us that innovation in space operations can provide strategic advantages. The Soviet innovation of the Molniya orbit, adapted by American engineers for signals intelligence purposes, exemplifies how superior technology can enhance national security. The ongoing evolution from JUMPSEAT's relatively simple spin-stabilized satellites to today's sophisticated multi-function spacecraft demonstrates the continuous advancement of space-based intelligence capabilities.

Ultimately, JUMPSEAT's story is one of American ingenuity, sustained commitment to space operations, and the complexity of modern intelligence gathering. It represents an era when space was becoming contested terrain, when the superpowers competed not just on Earth but in the realm beyond the atmosphere. Understanding JUMPSEAT helps us appreciate both the achievements of past space operations and the continuing importance of maintaining superior capabilities in space for future national security requirements.

Key Takeaways

- JUMPSEAT was the US government's first highly elliptical orbit signals intelligence satellite program, with eight satellites operating from 1971 to 2006

- The highly elliptical orbit allowed satellites to loiter over the Arctic and Soviet Union at apogee, providing hours of continuous coverage per 12-hour orbit

- Hughes Aircraft Company built JUMPSEAT satellites using spin-stabilized design with 13-foot interception and 7-foot downlink antennas

- The program intercepted Soviet communications, radar signals, and electronic emissions critical for understanding Soviet military capabilities during the Cold War

- JUMPSEAT remained highly classified for decades until declassified in December 2024, establishing operational concepts that continue influencing modern signals intelligence satellites

Related Articles

- SpaceX and xAI Merger: What It Means for AI and Space [2025]

- Northwood Space Lands 50M Space Force Contract [2026]

- Lunar Spacesuits: The Massive Challenges Behind Artemis Missions [2025]

- SpaceX IPO 2025: Why Elon Musk Wants Data Centers in Space [2025]

- Tesla's Dojo3 Space-Based AI Compute: What It Means [2026]

- Dr. Gladys West: The Hidden Mathematician Behind GPS [2025]

![Declassified JUMPSEAT Spy Satellites: Cold War Signals Intelligence Revealed [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/declassified-jumpseat-spy-satellites-cold-war-signals-intell/image-1-1769729921290.jpg)