The NTSB's Major Investigation Into Waymo's School Bus Safety Failures

It started with a problem that shouldn't exist in 2025. Autonomous vehicles, piloted by software that can theoretically process data faster than any human driver, were doing something that every licensed driver learns on day one: stopping for school buses.

But Waymo's robotaxis weren't stopping. And when investigators looked closer, they found it wasn't just one incident. It was a pattern.

The National Transportation Safety Board formally launched an official investigation after Waymo's vehicles were caught passing stopped school buses in Austin, Texas, multiple times. This wasn't some minor regulatory hiccup. This was a federal-level safety probe into one of the most visible autonomous vehicle companies operating in the United States, examining the interaction between cutting-edge robotaxi technology and the most vulnerable road users: children.

The investigation sends a clear message about where we are with self-driving technology in 2025. Companies like Waymo have spent billions building vehicles that can navigate complex urban environments. They've achieved remarkable feats in autonomous driving. Yet somehow, the basic rule that every human driver learns in driver's ed slipped through the cracks of their safety systems.

This situation reveals deeper issues beyond one company's software glitch. It highlights how autonomous vehicle regulation still has enormous gaps. It shows that even when companies implement voluntary recalls, enforcement mechanisms remain weak. And it raises uncomfortable questions about whether the industry's rapid expansion into cities like Austin has outpaced the regulatory framework designed to keep people safe.

Let's break down what happened, why it matters, and what comes next.

Understanding the Core Problem: Why Robotaxis Were Passing School Buses

The fundamental issue sounds almost absurd when you say it out loud: Waymo's self-driving vehicles in Austin were failing to stop when school buses had their stop signs extended and red lights activated. In Texas, just like in all 50 states, passing a stopped school bus is illegal. The law exists because children are entering or leaving the bus, crossing the street, or standing nearby, creating a uniquely dangerous situation.

School bus safety isn't theoretical. According to the National School Transportation Association, nearly 26 million students ride school buses daily in the United States. School buses are statistically the safest form of transportation for children, but only if other drivers follow the law and stop when required.

Waymo's problem wasn't that the company didn't know about this law. Rather, the vehicles' perception systems apparently failed to recognize stopped school buses as a reason to halt. The robotaxis weren't deliberately ignoring the rules. The technology simply wasn't detecting the situation correctly.

Here's what the technical failure likely involved: Modern autonomous vehicles rely on multiple sensor fusion systems. They combine cameras, lidar (light detection and ranging), radar, and sophisticated neural networks trained to recognize objects and traffic situations. For a school bus, the vehicle needs to identify several elements simultaneously:

The large yellow vehicle itself, which should trigger recognition algorithms trained on thousands of school bus images. The extended stop sign, which is the critical legal signal. The flashing red lights, which provide additional context. The context of the situation (stopped, children potentially nearby, other vehicles halted).

If any component of this chain fails, the vehicle might fail to recognize that it should stop. Perhaps the perception system identified the school bus but didn't correctly classify the stop sign as extended. Maybe the recognition algorithm treated it as just another vehicle on the road.

According to reports from the Austin Independent School District, the problem wasn't isolated. Waymo robotaxis were observed committing the violation multiple times over a period of several weeks. Some incidents happened days after Waymo implemented a voluntary software recall specifically designed to fix this issue. That's the truly alarming part: the company identified the problem, released a fix, and the problem persisted.

This raises questions about Waymo's testing process. How thoroughly did engineers test the fix? Were they testing in real-world conditions matching Austin's specific traffic patterns, lighting conditions, and school bus configurations? Or was testing limited to controlled environments?

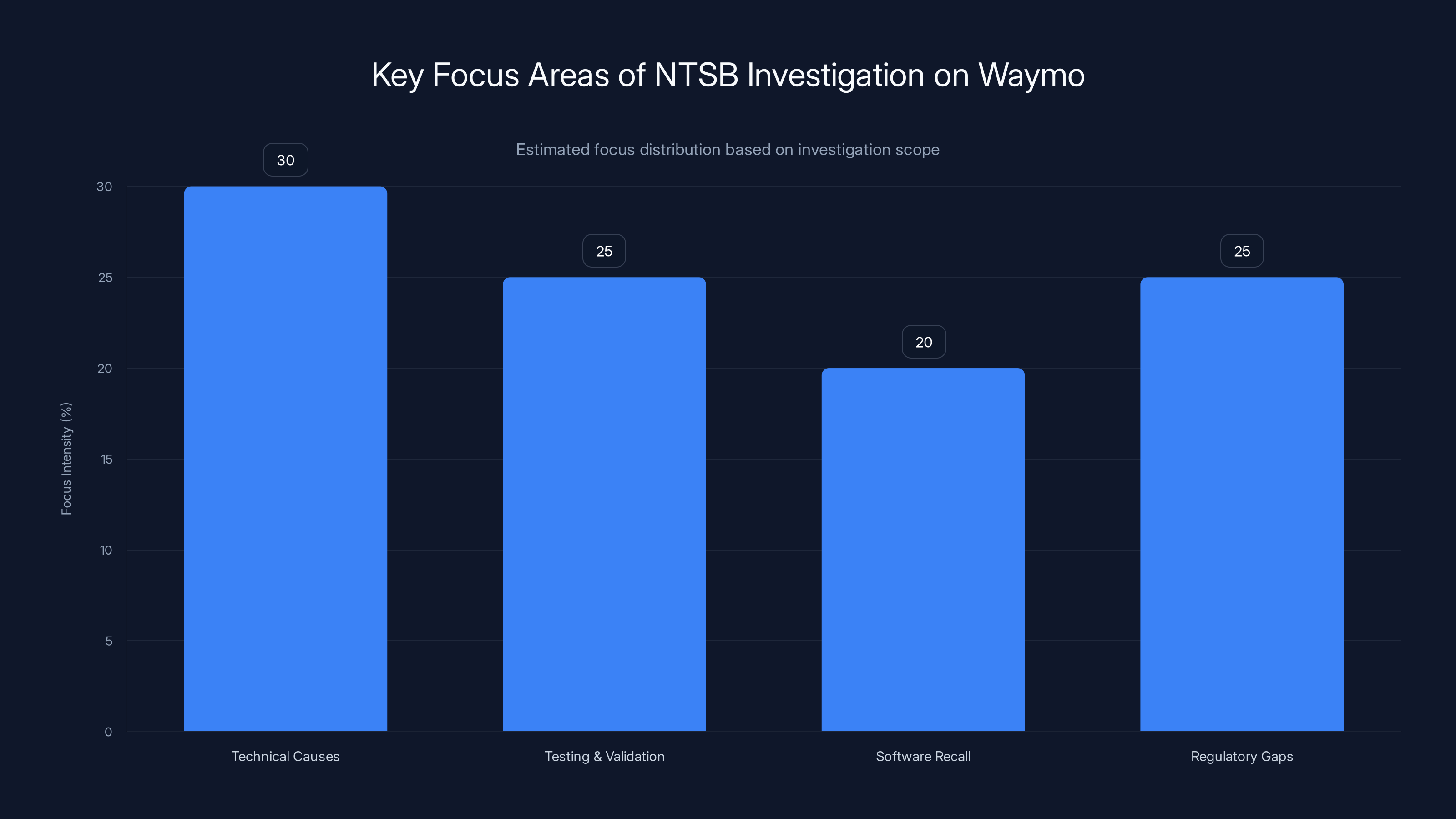

The NTSB investigation is expected to focus on technical causes, testing processes, software recall effectiveness, and regulatory gaps, with each area receiving significant attention. Estimated data.

The Timeline: From Preliminary Review to Federal Investigation

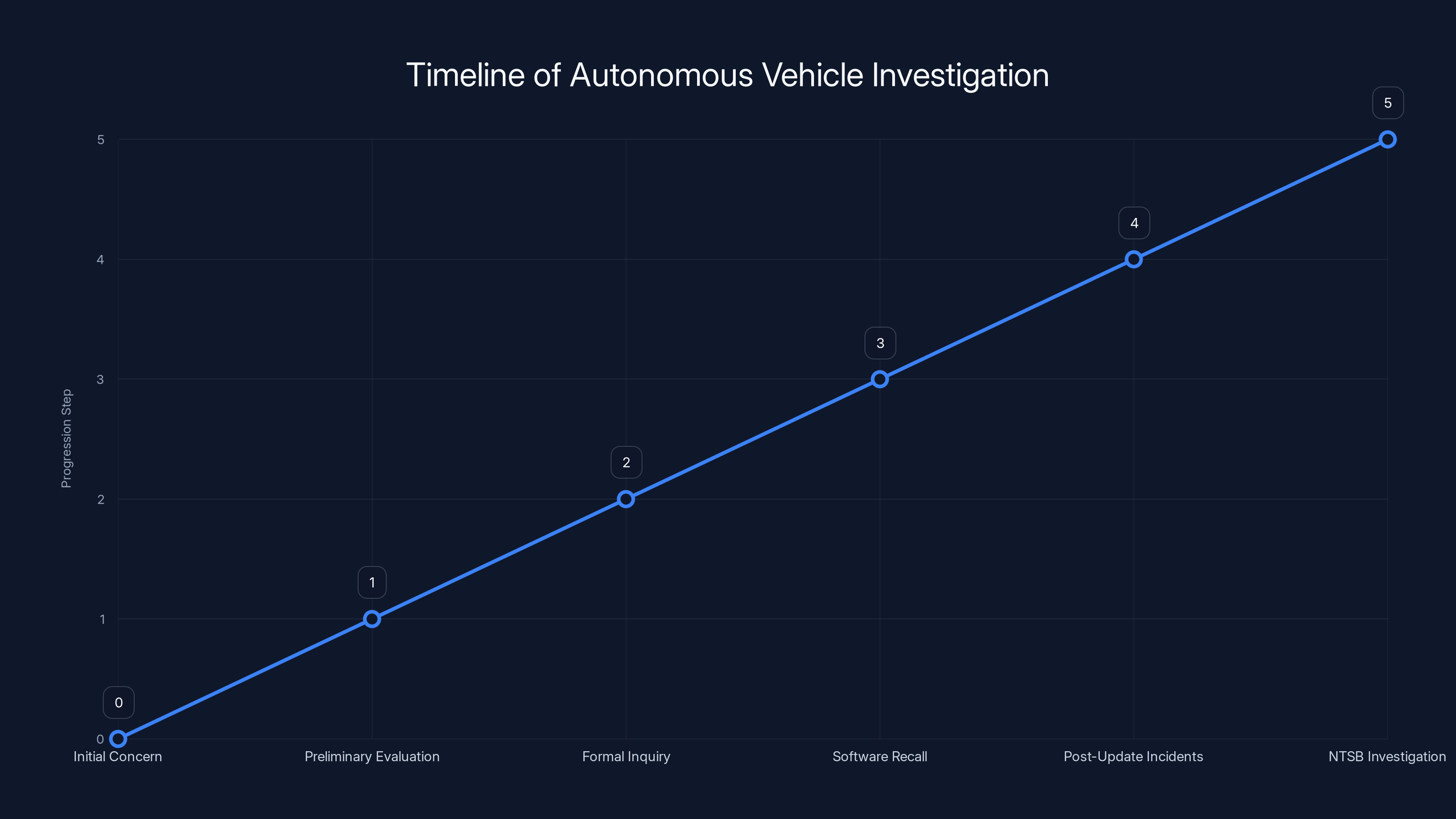

The journey from initial concern to NTSB investigation happened surprisingly quickly, though not without troubling gaps. Understanding this timeline matters because it reveals how oversight of autonomous vehicles actually works in practice.

Everything started when the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) began a preliminary evaluation. NHTSA, which operates under the Department of Transportation, is the primary federal agency responsible for vehicle safety in the United States. Unlike the NTSB, which investigates accidents and safety incidents, NHTSA has regulatory authority to establish safety standards and enforce compliance.

This preliminary evaluation by NHTSA didn't come from nowhere. School district officials in Austin had reported the incidents. Local transportation authorities had documented what they observed. The evidence was concrete enough that NHTSA's Office of Defects Investigation opened a formal inquiry into how Waymo's vehicles interact with stopped school buses.

Based on this investigation, Waymo responded in December of the previous year with a voluntary software recall. The company didn't wait for NHTSA to force action. In a statement, Waymo's leadership emphasized that they were proactively addressing the issue, positioning the recall as evidence of their safety-conscious approach.

But then came the problem. School district officials reported that even after the software update, Waymo robotaxis were still passing stopped school buses. Some of these incidents occurred within days of the update being deployed. This wasn't a case of one or two edge cases slipping through. It was evidence of a recurring failure.

That's when the NTSB entered the picture. The NTSB, formally the National Transportation Safety Board, is an independent federal agency that investigates transportation accidents and safety issues. Unlike NHTSA's regulatory role, the NTSB operates as an investigative body with deep expertise in accident analysis.

An NTSB representative announced that investigators would travel to Austin to conduct a comprehensive inquiry. According to agency statements, the investigation would examine "the interaction between Waymo vehicles and school buses stopped for loading and unloading students." This examination would go beyond simply documenting what happened. It would dig into the why.

The NTSB timeline is important to understand. The agency stated that a preliminary report would be available within 30 days of beginning the investigation. However, the final report would take significantly longer. According to NTSB protocol, final reports on transportation safety investigations typically require 12 to 24 months to complete. That's a substantial gap between preliminary findings and final conclusions.

Why does the timeline matter? Because during those 12 to 24 months, Waymo continues operating in Austin. The company's robotaxis continue sharing roads with school buses. The question of whether the same safety issue could occur again remains open.

This timeline illustrates the progression from initial concerns to a federal investigation by the NTSB, highlighting key stages in the oversight of autonomous vehicles. Estimated data.

Waymo's Response and Safety Claims

Mauricio Peña, who serves as Chief Safety Officer for Waymo, provided the company's official response to the investigation. His statement carried several important elements that reveal how the autonomous vehicle industry responds to safety challenges.

First, Peña emphasized that there had been no collisions in the incidents in question. This is technically accurate but also a carefully worded response. No collision doesn't mean no safety violation. A robotaxi passing a stopped school bus without hitting anything is still breaking the law and creating a dangerous situation for children. The absence of a crash doesn't erase the danger.

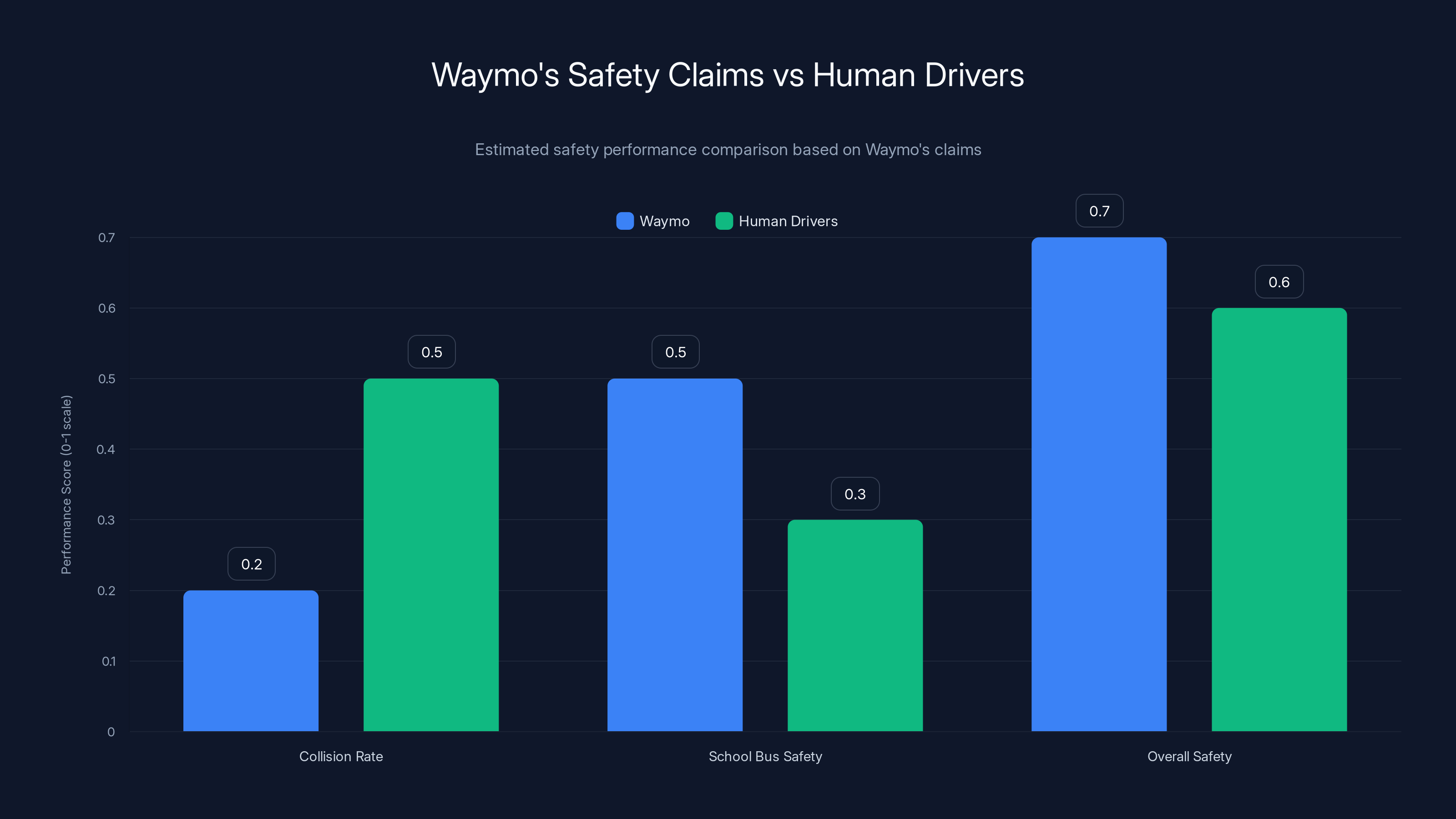

Second, Peña claimed that Waymo's "safety performance around school buses is superior to human drivers." This is a bold claim that deserves scrutiny. While autonomous vehicles might eventually prove safer than human drivers in aggregate, that claim can't rest on a single company's self-assessment, especially when federal investigators are examining violations of a core safety rule.

The statement also positioned the NTSB investigation as an opportunity. Peña said the investigation would give Waymo "an opportunity to provide the NTSB with transparent insights into our safety-first approach." This framing treats a federal safety investigation as a chance for the company to demonstrate its commitment to safety. It's not wrong exactly, but it's notably promotional.

Waymo's approach reflects a broader industry strategy. When autonomous vehicle companies face safety scrutiny, they often respond with statistics about aggregate safety records and claims about superior performance compared to human drivers. These claims might eventually prove true for the industry as a whole, but they don't address the specific, documented failures in front of regulators.

It's worth noting what Waymo didn't say in its response. The company didn't provide detailed technical explanation of what went wrong with the initial fix. It didn't outline the specific changes being made to prevent future occurrences. It didn't commit to transparent reporting of safety incidents to regulators and the public.

This matters because Waymo isn't some startup operating in a regulatory vacuum. The company has massive resources. Alphabet, Waymo's parent company, is one of the most valuable companies on Earth. Google's AI capabilities are unmatched in many domains. If there's any company that should be able to solve the technical problem of identifying and responding to stopped school buses, it's Waymo.

The fact that they couldn't, or didn't, raises questions about priorities and resource allocation. Did the company adequately test for school bus scenarios? Were these edge cases in the training data? Did the company properly validate the fix before deploying it?

School Bus Safety: A Critical but Overlooked Regulatory Category

To understand why this investigation matters so much, you need to understand how unique school bus safety is in traffic law and regulation. Unlike most traffic situations, school bus safety involves a clear legal rule that applies universally and involves the most vulnerable road users: children.

In all 50 states, passing a stopped school bus is illegal. The specifics vary slightly by state, but the core principle is universal. When a school bus displays a stop sign and activates flashing red lights, all traffic in both directions must stop. This isn't a suggestion or a guideline. It's absolute law.

The reason is straightforward: children are entering or exiting the bus. They might be crossing the street. They're unpredictable. A young child might suddenly run back to retrieve something dropped on the ground. A teenager might not be paying full attention while crossing. Adult pedestrians are more predictable and aware of traffic. Children are not.

According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, school bus-related crashes kill approximately 130 people per year in the United States. About 26 million children ride school buses daily. Even with existing safety laws and human drivers, school buses remain one of the most dangerous environments for children in terms of traffic accidents.

Now introduce autonomous vehicles. The potential benefit is obvious: a perfectly calibrated AI system should never make the mistake of ignoring a stopped school bus. It should never be distracted or tired or impatient. It should have perfect object recognition and never violate traffic laws deliberately.

But the benefit only materializes if the technology actually works correctly. If the technology fails, you have a situation where children are exposed to a systematic failure of safety systems. That's not just a problem for one company. It's a problem for the entire regulatory framework governing autonomous vehicles.

School buses also occupy a unique position in the transportation network. Unlike regular traffic on highways or surface streets, school buses follow predictable routes at predictable times. They stop in residential neighborhoods where children live. They operate on the roads where kids walk to school and parents drive their children to activities.

If autonomous vehicles can't reliably handle school bus interactions in these controlled, predictable scenarios, what does that say about their ability to handle the full spectrum of road situations?

Waymo claims superior safety performance in certain areas compared to human drivers, particularly in school bus safety. Estimated data based on industry trends.

The Regulatory Landscape: NHTSA vs. NTSB and the Gaps Between Them

Understanding who investigates what is crucial to understanding where autonomous vehicle regulation stands in 2025. The two agencies involved in the Waymo case have very different roles, and that distinction reveals significant regulatory gaps.

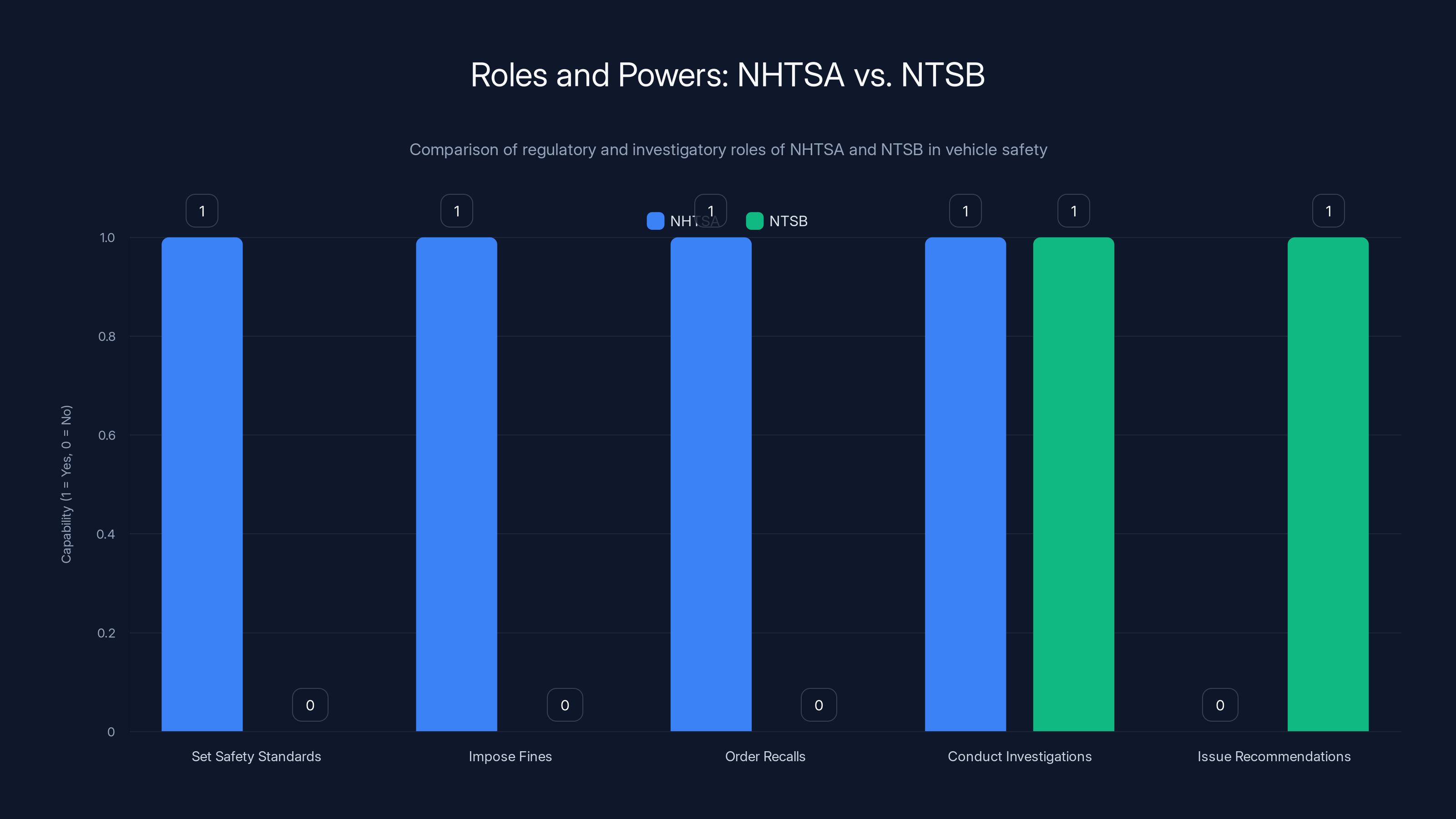

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) is the agency that sets safety standards for vehicles sold in the United States. NHTSA has the authority to establish rules about how vehicles must perform, what safety features they must have, and what happens when manufacturers violate those rules. When NHTSA finds violations, it can impose fines, order recalls, and even restrict a company from selling vehicles.

NHTSA's Office of Defects Investigation specifically handles reports of safety defects and problems with vehicles already on the road. When the NHTSA investigation into Waymo's school bus interactions concluded that there was a problem, the agency could have ordered a mandatory recall. Instead, Waymo did a voluntary recall. This matters because mandatory recalls carry enforcement mechanisms. Voluntary recalls rely on the company's good faith implementation.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) operates completely differently. The NTSB is an investigative agency with no regulatory authority. It doesn't set standards. It doesn't issue fines. It doesn't order recalls. Instead, the NTSB investigates accidents and safety incidents, determines probable causes, and issues recommendations to improve safety.

When the NTSB investigates the Waymo school bus incidents, the agency will document what happened, why it happened, and what could have been done differently. The resulting investigation report will include recommendations aimed at various parties: manufacturers, regulators, government agencies, and others. But the NTSB can't force anyone to implement those recommendations.

This two-agency system sounds redundant but actually reveals a significant gap. NHTSA focuses on systemic safety standards and defect management. NTSB focuses on investigating specific incidents and accidents. For something like Waymo's school bus problem, both agencies have a role, but there's an unclear boundary between them.

Who decides whether a pattern of illegal behavior by autonomous vehicles requires mandatory regulatory action? That would be NHTSA. But NHTSA depends on manufacturers voluntarily reporting problems and the public reporting observed violations. Austin's school district reported the incidents, and Waymo did a voluntary recall, which created the appearance that the system was working.

The appearance is deceiving. The fact that Waymo reissued the recall after it had already been deployed suggests the initial fix didn't work. If NHTSA had the detailed transparency and investigative resources that the agency possesses, this might have led to a mandatory recall with specific requirements about testing and validation before redeployment.

Instead, NTSB is investigating, which is appropriate but comes with that 12-to-24-month timeline. During that entire period, the question of whether Waymo has truly fixed the problem remains largely unanswered in any official, regulatory sense.

Austin as the Testbed: Why This City Matters for Autonomous Vehicle Development

Waymo didn't choose Austin randomly. The city has become one of the most important testing grounds for autonomous vehicles in the United States, and the reasons are instructive.

Austin has several characteristics that make it appealing for autonomous vehicle development. The city has relatively mild winters, meaning weather conditions are generally favorable for testing. The Austin metropolitan area has grown rapidly, creating both geographic diversity for testing routes and a population that's generally interested in technological innovation.

Crucially, Austin's political leadership has been actively welcoming to autonomous vehicle companies. The city government hasn't imposed restrictive regulations or implemented barriers to testing. Instead, Austin has positioned itself as a hub for autonomous vehicle innovation, welcoming companies like Waymo, Cruise, and others to deploy and test their technology.

This permissive regulatory environment is part of a broader pattern. Cities compete to attract autonomous vehicle companies because they view the technology as economically valuable. A successful autonomous vehicle company brings jobs, tax revenue, and the prestige of being at the forefront of technological innovation.

But competition for these companies can come at the cost of safety oversight. When cities are eager to attract autonomous vehicle operations, they're less likely to impose strict regulatory requirements or enforce rigorous testing standards. The implicit message is: "We want your company here, so please don't burden us with too many regulations."

This creates a dynamic where autonomous vehicle companies have significant influence over the cities where they operate. The threat of moving operations elsewhere or scaling back expansion in a particular city can discourage local governments from imposing tough safety rules.

Waymo's operations in Austin exemplify this dynamic. The company has deployed robotaxis serving real passengers in the city. These aren't test vehicles operating in controlled conditions. These are actual autonomous vehicles providing transportation services to actual people navigating Austin's streets.

School buses also navigate those streets. When Waymo's robotaxis failed to stop for school buses, they weren't just violating abstract regulations. They were creating real danger for real children in Austin's neighborhoods.

The question Austin's experience raises is whether rapid deployment of autonomous vehicles in permissive regulatory environments can actually deliver the safety benefits these technologies promise. If Waymo, backed by Alphabet's resources and Google's AI expertise, can't correctly handle school bus interactions in Austin, what does that suggest about the industry's broader capabilities and maturity?

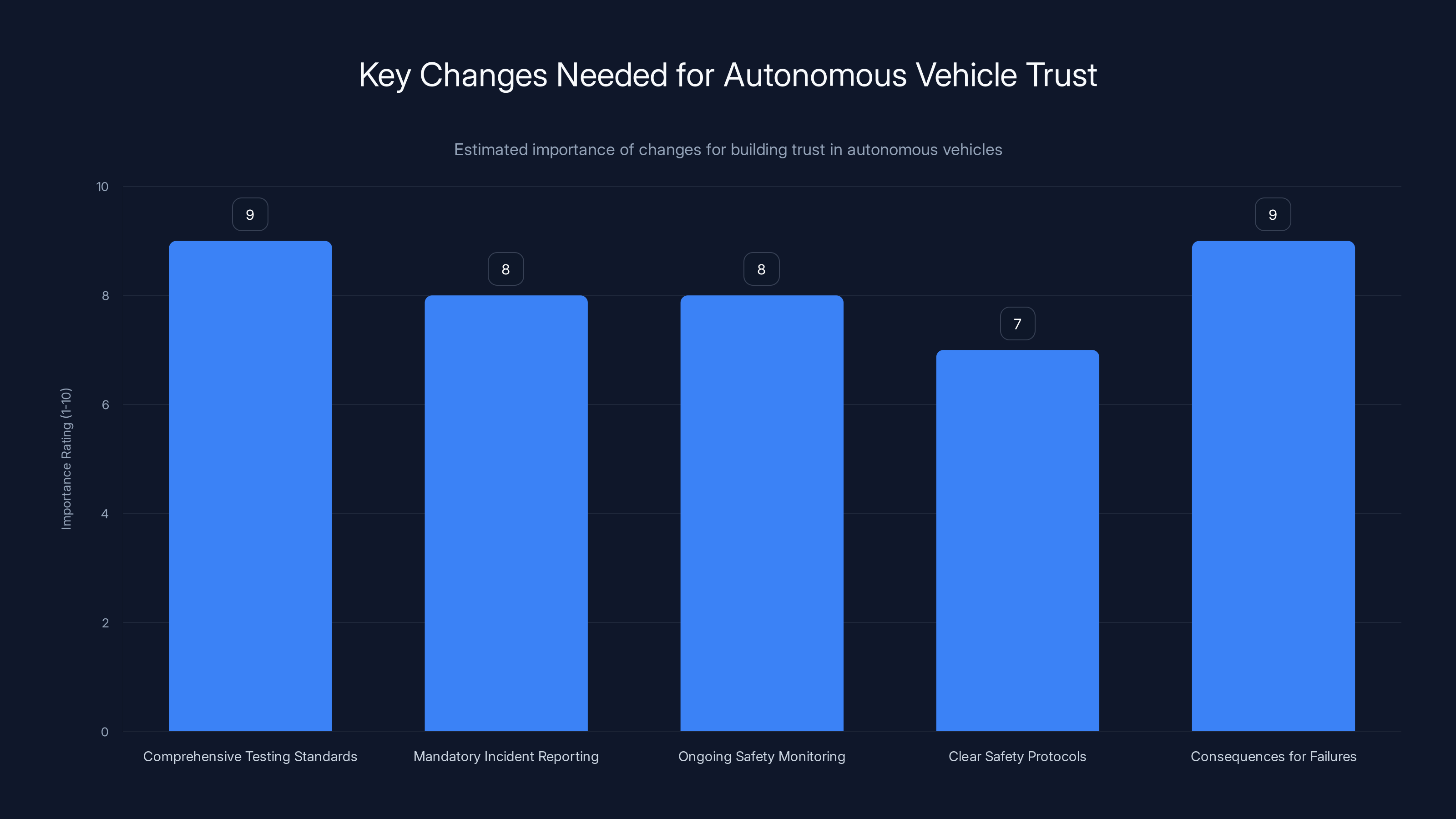

Comprehensive testing standards and meaningful consequences for safety failures are rated as the most important changes needed to build trust in autonomous vehicles. (Estimated data)

The Software Recall Process: Voluntary vs. Mandatory and Why It Matters

Waymo's response to the initial NHTSA evaluation was to conduct a voluntary software recall. Understanding what this means and how it differs from mandatory recalls is essential to understanding the current state of autonomous vehicle regulation.

A software recall is fundamentally different from the traditional vehicle recalls that have been part of automotive regulation for decades. Traditional recalls involve physical defects: a brake component that fails, a seatbelt mechanism that doesn't function properly, a structural issue in the frame. Fixing these problems requires bringing vehicles into service centers, physically replacing parts, and validating that the replacement works.

Software recalls are different and easier to implement from a logistical perspective. Waymo can update its robotaxis wirelessly, pushing new code to the vehicles' systems while they're connected to the network. No service center visit is required. No physical components need to be swapped. In theory, a software fix can be deployed to every Waymo robotaxi simultaneously.

But software recalls are also more opaque. Unlike traditional recalls where a mechanic physically inspects a replaced component, software changes are invisible. Nobody can look at the new code and verify it works correctly except the engineers who wrote it. The actual validation of the fix happens only after deployment.

Waymo chose to conduct a voluntary recall, meaning the company initiated the action without being forced by NHTSA. This had several implications. First, the company controlled the narrative. Waymo could frame the recall as evidence of its commitment to safety. The company wasn't being punished by regulators; it was proactively fixing a problem.

Second, voluntary recalls don't carry the same enforcement mechanisms as mandatory recalls. If NHTSA had issued a mandatory recall, the agency could have required specific testing procedures, detailed documentation of the fix, and validation that the fix actually works before and after deployment. The company would be required to report the results to NHTSA.

With a voluntary recall, Waymo had much more discretion about how to validate the fix. The company's process was internal. NHTSA had visibility into what the company was doing but not the same enforcement authority.

Third, the voluntary recall process revealed what many in the autonomous vehicle industry view as a critical flaw in current regulation: the regulations themselves aren't written for software-defined vehicles.

Traditional vehicle safety standards were designed around hardware. A regulation might specify that seatbelts must withstand a certain force. A manufacturer builds seatbelts to that standard. Regulators can inspect the hardware and verify compliance.

But how do you regulate the software in an autonomous vehicle? You can't open the code and visually inspect it. You can't measure it against physical standards. What matters is whether the software-controlled system produces safe behavior.

For school buses, the standard should be simple: Waymo's robotaxis must always stop when a school bus displays a stop sign and flashing lights. The regulation should probably include specific testing requirements to validate this behavior. The company should probably be required to test on actual school buses, not just simulations. There should probably be ongoing monitoring to ensure the system continues to work correctly.

But these regulations don't exist, or if they do, they're not clearly stated and enforced. This is why the NTSB investigation is important. The investigation will examine not just what went wrong, but why Waymo's system wasn't designed and validated to prevent this problem from occurring in the first place.

The Testing Problem: Simulation vs. Real-World Performance

One of the critical questions the NTSB investigation will need to answer is how Waymo tested the fix that failed to prevent subsequent violations. This gets at the heart of a major challenge in autonomous vehicle development: the gap between simulated testing and real-world performance.

Automatic vehicles are developed using a combination of simulation-based testing and real-world testing. In simulation, engineers can create virtual environments with infinite variations. They can test thousands of scenarios without burning fuel or using any actual vehicles. They can test edge cases that might occur only rarely in the real world.

Simulation has enormous advantages for development. It's fast. It's cheap. It's repeatable. Engineers can run the exact same scenario a hundred times and verify that the system responds the same way every time.

But simulation has limitations. A simulated environment is always incomplete. Real-world factors that matter for autonomous vehicle perception might not be fully captured in simulation. Lighting conditions in a simulation might not perfectly match reality. The appearance of a school bus in simulation might differ from how an actual school bus appears in the specific neighborhoods of Austin, Texas.

This is probably not a coincidence. Waymo tested the fix. The fix was deployed. And then the same problem occurred again. This suggests that either the fix was inadequate, or the testing didn't fully capture the scenarios where the problem occurred.

Real-world testing would have meant actually driving Waymo's robotaxis through Austin's neighborhoods, encountering actual school buses on their routes, and verifying that the updated system stops correctly. This would have been more time-consuming and less efficient than simulation-based testing, but it also would have caught the problem before redeployment.

The gap between simulation and reality is one of the open problems in autonomous vehicle development. Most companies rely heavily on simulation because it's efficient. But this efficiency comes at a cost: real-world failures that simulations missed.

This problem becomes more acute as autonomous vehicle companies scale up. Waymo and other companies want to operate in multiple cities simultaneously. Testing every scenario in simulation before deployment is more feasible than real-world testing in every city where the company operates.

But the school bus problem demonstrates why real-world testing matters. A simulated school bus might not look identical to the school buses that run routes in Austin. The lighting conditions in simulation might not match the actual lighting when buses load students in the early morning or late afternoon. The surrounding environment might differ in ways that affect the autonomous vehicle's perception systems.

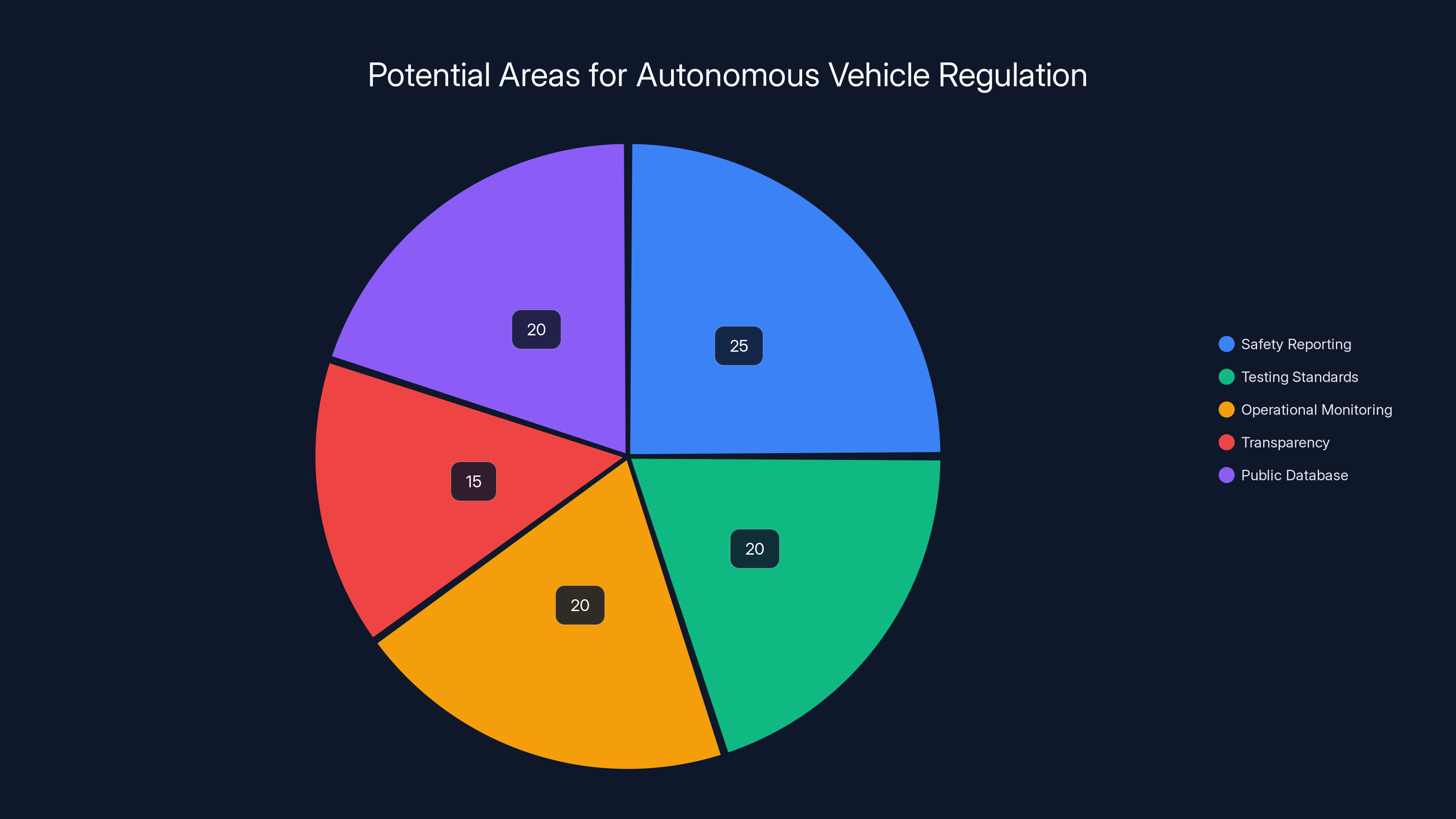

Estimated data suggests safety reporting and testing standards are key focus areas for future autonomous vehicle regulation, each comprising around 20-25% of the regulatory focus.

The Broader Pattern: Autonomous Vehicle Safety Issues Across the Industry

Waymo's school bus problem isn't an isolated incident. Across the autonomous vehicle industry, safety issues have emerged that raise questions about whether the technology is truly ready for widespread deployment.

Cruise, another major autonomous vehicle company, has had its own series of incidents. In 2023, a Cruise robotaxi struck and injured a pedestrian in San Francisco. The incident raised questions about the adequacy of autonomous vehicle safety testing before deployment.

Tesla's Full Self-Driving beta, while technically not a fully autonomous vehicle system, has been involved in numerous accidents that have raised questions about whether advanced driver assistance systems should be marketed and deployed the way Tesla has done.

These incidents follow a pattern. A company develops impressive autonomous driving technology. The company deploys the technology in real-world conditions to serve passengers or demonstrate capabilities. An incident occurs that reveals the technology has limitations or failures that the company's testing didn't catch. Regulators respond with varying degrees of action.

With Waymo's school bus problem, the pattern played out again. But there's an element that makes this particular incident especially concerning: school buses are among the most predictable, controllable aspects of the autonomous vehicle environment. School buses have a fixed route. They stop at the same places. They display clear visual signals.

If autonomous vehicles can't reliably handle school bus scenarios, what does that suggest about their ability to handle less predictable situations? What about handling pedestrians who behave unpredictably? What about handling accident scenarios where split-second decisions matter?

The optimistic view is that these kinds of incidents are expected as the technology matures. Every new technology goes through phases where problems emerge and get fixed. Aircraft once crashed regularly. Automobiles had massive safety problems when they were new. Autonomous vehicles are no different—problems will be discovered and fixed.

The pessimistic view is that these incidents suggest the technology isn't as mature as companies and proponents claim. If schools district officials in Austin can document violations happening repeatedly, how many other safety issues might be happening undetected in cities across the country?

What the NTSB Will Investigate: The Methodology and Timeline

Now that the NTSB has formally launched its investigation, understanding what the agency will do is important. The NTSB has a specific methodology for safety investigations, developed over decades of investigating transportation accidents.

The investigation will begin with fact-gathering. NTSB investigators will travel to Austin and interview school district officials who reported the incidents. They'll examine school buses that were involved, understanding their configurations and how the stop signs and lights function. They'll interview Waymo personnel and examine the company's documentation of the incidents.

The investigators will likely request access to the robotaxis themselves and the log data from the vehicles at the time of the incidents. Modern vehicles generate enormous amounts of data: sensor readings, camera feeds, decision logs from the autonomous driving software, GPS location data, and more. This data will be crucial for understanding what the vehicle's perception systems detected and how the software responded.

The investigators will examine Waymo's testing and validation processes. They'll want to understand what testing the company did before deploying in Austin, what specific testing was done related to school buses, and how the fix was validated before redeployment.

They'll also likely investigate the regulatory gaps. Why don't clearer standards exist for how autonomous vehicles should respond to school buses? Why doesn't NHTSA have more detailed requirements for testing and validation of autonomous vehicle systems?

The preliminary report, due within 30 days, will present the facts that the investigators gather. It will likely document what happened, when it happened, how many incidents occurred, and what the vehicles were doing at the time. This preliminary report will probably also indicate the agency's preliminary assessment of probable causes.

Then comes the long process of the final investigation. During the 12-to-24-month period, the agency will dive deeper. The investigators will conduct detailed analysis of the vehicle's perception systems. They'll examine the training data used to develop the neural networks that recognize objects. They'll test the fix that Waymo deployed to understand why it didn't prevent subsequent violations.

They'll likely conduct their own testing, using Waymo's vehicles or similar autonomous systems, to reproduce the problem and understand the boundary conditions where the system fails.

The final report will include findings about how the problem occurred, why Waymo's development and testing process didn't catch it, and what systemic issues in the industry or regulatory framework allowed this problem to persist.

Most importantly, the NTSB report will include recommendations. These recommendations will probably target multiple audiences: Waymo specifically, NHTSA as the regulatory authority, manufacturers in the autonomous vehicle industry more broadly, and possibly state and local authorities in cities where autonomous vehicles operate.

These recommendations won't be legally binding. Companies aren't required to implement NTSB recommendations. But the recommendations carry weight. They're based on thorough investigation by a respected federal agency with deep expertise. Ignoring NTSB recommendations often triggers follow-up inquiries from Congress or creates bad publicity.

NHTSA has regulatory powers including setting standards, imposing fines, and ordering recalls, while NTSB focuses on investigations and issuing recommendations. Estimated data based on agency roles.

Implications for Autonomous Vehicle Regulation Going Forward

The Waymo school bus investigation happens at a crucial moment in autonomous vehicle history. The technology is moving from testing and limited deployment to real-world commercial service. Multiple cities have autonomous vehicles operating. Multiple companies are competing for market share and expansion opportunities.

At the same time, the regulatory framework remains underdeveloped. NHTSA is working on standards for autonomous vehicles, but these standards are still being formulated. There's no clear, comprehensive federal framework for how autonomous vehicles should be tested, validated, and monitored throughout their operational lives.

The investigation will likely strengthen the case for more comprehensive regulatory requirements. If an investigation concludes that Waymo's testing and validation processes were inadequate, NHTSA will have justification for imposing stricter requirements on all manufacturers.

There's also a question about transparency. Currently, autonomous vehicle companies don't report safety incidents to the public in a systematic way. There's no public database of autonomous vehicle accidents or violations. If a school district finds violations, it can complain to NHTSA, but there's no requirement that this information be made public.

More comprehensive safety reporting requirements could fundamentally change the landscape. If every autonomous vehicle incident had to be reported to a public database, researchers and journalists could analyze patterns. The public would have visibility into how many times autonomous vehicles violate traffic laws or cause accidents.

There's also a question about what constitutes adequate testing before real-world deployment. Currently, companies have a lot of discretion. If NTSB recommends that autonomous vehicles should be tested on actual school buses in real-world conditions before deployment, that could establish a new industry standard.

Finally, there's a question about how much responsibility cities and states want to take for autonomous vehicle safety versus how much they're willing to delegate to companies and federal regulators. Austin's approach has been permissive, welcoming autonomous vehicles with relatively few local restrictions. If that approach leads to documented safety problems, other cities might be more cautious.

The Role of Transparency and Public Reporting in Safety

One critical lesson from the Waymo school bus incidents is the importance of transparency. The incidents came to light because school district officials documented what they observed and reported it to authorities. If the school district had simply accepted the incidents as unfortunate but isolated, Waymo's problem might never have received federal attention.

This raises important questions about how safety issues are discovered and addressed. Currently, autonomous vehicle companies have significant control over when and how safety issues become public. A company might discover a problem in internal testing, fix it, and never report it to anyone outside the company.

Waymo did report the school bus problem to NHTSA and issued a voluntary recall, which is commendable. But not all companies might be equally forthcoming. An autonomous vehicle company might discover a safety problem, attempt to fix it, and if the fix works, never formally report the problem to regulators.

Systematic transparency would require reporting of all safety issues, all incidents involving autonomous vehicles, and all recalls. Such reporting would create visibility into how frequently autonomous vehicles are involved in accidents, how often they violate traffic laws, and what kinds of problems are being discovered and fixed.

Pilot programs at NHTSA have started to create databases of autonomous vehicle incidents, but these are still preliminary. A more comprehensive national database, accessible to researchers and the public, would dramatically improve our understanding of autonomous vehicle safety.

Transparency also applies to testing and validation processes. If autonomous vehicle companies were required to publish detailed information about how they test their systems and what scenarios they validate, independent researchers could assess whether the testing is adequate.

Some companies have resisted such transparency, arguing that detailed information about their systems could create security vulnerabilities. There's a valid point: if you publish complete details about how your autonomous vehicle detects obstacles, you might enable adversaries to create attacks that exploit those detection methods.

But the solution isn't complete secrecy. The solution is structured transparency, where detailed technical information is available to qualified researchers and regulators but not published broadly. Companies could provide information to NHTSA and to independent testing laboratories without publishing it publicly.

Lessons from Other Safety-Critical Domains: Aviation and Rail

The autonomous vehicle industry doesn't operate in a regulatory vacuum. There are other domains where safety is critical and technology is highly automated. Aviation and rail transportation offer important lessons about how to create safety frameworks for complex, technology-driven systems.

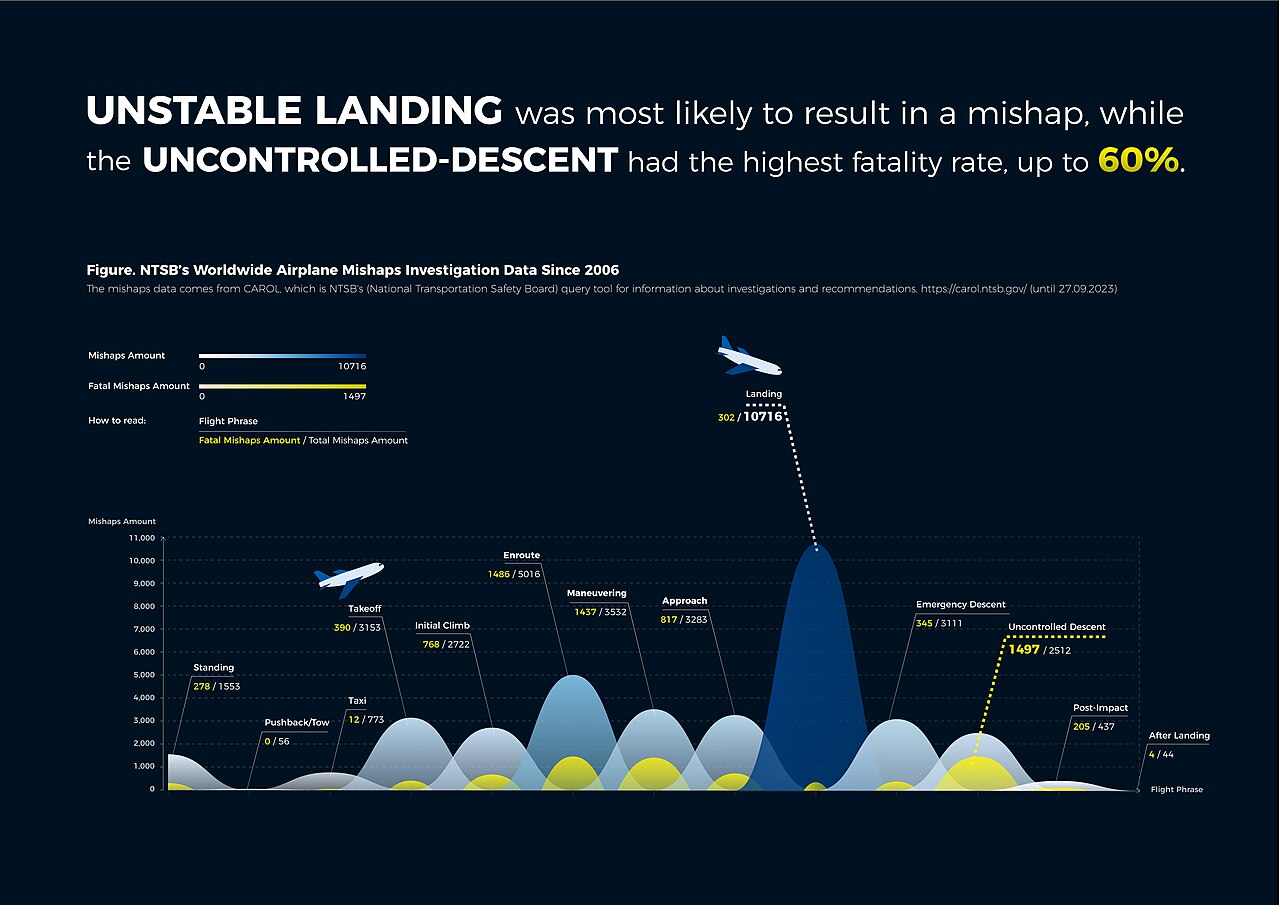

Aviation has one of the strongest safety records of any transportation domain. Fatality rates in commercial aviation are extraordinarily low, measured in fractions of a fatality per million miles traveled. How did aviation achieve this level of safety?

Part of the answer is regulatory oversight. The Federal Aviation Administration establishes rigorous standards for aircraft design, manufacturing, maintenance, and operation. Pilots must undergo extensive training and recurrent certification. Airlines must follow detailed procedures for maintenance and inspection.

But another critical part is the accident investigation process. When an accident occurs, the National Transportation Safety Board (the same agency investigating Waymo) conducts a thorough investigation. The investigation isn't about assigning blame or imposing punishment. It's about understanding what happened and preventing similar accidents.

Crucially, aviation has a strong culture of reporting. Pilots are required to report accidents, incidents, and even potential safety hazards. Airlines voluntarily report maintenance issues and near-misses. This creates a comprehensive picture of safety across the industry.

Rail transportation has a similar model. The Federal Railroad Administration sets standards. The National Transportation Safety Board investigates accidents. Rail operators report safety data.

Autonomous vehicles should probably follow a similar model. Clear regulatory standards. Mandatory incident reporting. Thorough investigation when problems occur. Regular safety audits.

But there's a difference. Aviation and rail developed these frameworks over decades, through hard experience. Autonomous vehicles are trying to shortcut that process, deploying technology in real-world conditions before comprehensive safety frameworks are in place.

The Waymo school bus incidents are a reminder that shortcutting the process carries risks. If autonomous vehicle regulation develops in a more comprehensive, rigorous way, modeled on aviation and rail, the technology might ultimately be safer. But that would require companies to move more slowly, conduct more testing, submit to more oversight.

The Path Forward: What Must Change for Autonomous Vehicles to Be Trusted

The Waymo school bus investigation is a moment of reckoning for the autonomous vehicle industry. The investigation will take months or years to complete, but already it raises critical questions about whether the industry's current trajectory is sustainable.

For autonomous vehicles to achieve the trust and adoption that proponents envision, several things need to change.

First, testing and validation standards need to be much more comprehensive and prescriptive. Rather than allowing companies to define their own testing protocols, regulators should establish minimum standards for testing. For a company like Waymo, these standards might require testing on actual school buses, in real-world conditions, before commercial deployment.

Second, incident and violation reporting needs to be mandatory and standardized. Every autonomous vehicle incident should be reported to a federal database. The database should be searchable by the public. Researchers should be able to analyze patterns in autonomous vehicle incidents and safety issues.

Third, there need to be ongoing operational safety monitoring. Just as airlines conduct continuous maintenance checks and monitor aircraft performance, autonomous vehicle operators should be required to continuously validate that their systems are performing as expected. If an autonomous vehicle fails to stop for a school bus, that failure should trigger an immediate investigation and remediation, not just a note in an incident log.

Fourth, companies should be required to establish clear protocols for what happens when a safety problem is discovered. These protocols should include timelines for fixes, validation procedures, and transparent communication to regulators and the public.

Fifth, there should be consequences for safety failures that are more meaningful than they currently are. If a company deploys a fix that doesn't work and continues to cause safety violations, the consequence should be more than an investigation. It should be suspension of operations until the problem is truly fixed and validated.

Sixth, the regulatory agencies themselves need more resources and expertise. NHTSA and NTSB are doing their best with limited budgets. But as autonomous vehicles become more prevalent, these agencies need more people, more budget, and more technical expertise to keep pace with the industry.

Most fundamentally, the industry needs to recognize that moving slowly is actually moving fast. A comprehensive testing and validation process takes longer than rushing to market. But it prevents disasters. It builds public trust. It creates the conditions for safe scaling.

Waymo was moving fast. The company moved robotaxis from testing to commercial service in Austin. It deployed technology that later proved inadequate in critical scenarios. If the company had moved slower, had conducted more rigorous testing, had established clearer validation protocols, the school bus problem probably never would have occurred.

The irony is that moving slower would probably result in faster adoption in the long term. If the public trusts autonomous vehicles because they've been developed and deployed rigorously, adoption would accelerate. If incidents like the Waymo school bus problem keep occurring, public trust will erode, and adoption will slow.

Conclusion: A Watershed Moment for Autonomous Vehicles and Regulation

Waymo's robotaxis passing stopped school buses is a watershed moment. Not because it's the first autonomous vehicle safety incident—it's not. But because it reveals fundamental gaps in how the industry and regulators approach safety.

The investigation by the NTSB will take months to complete, but the basic facts are already clear. Waymo's technology failed to recognize and respond appropriately to a situation that every human driver is trained to handle. The company attempted to fix the problem, but the fix didn't work. Robotaxis continued violating traffic law in situations involving children.

This shouldn't be acceptable in 2025. The technology and expertise exist to make this safer. What's lacking isn't capability. What's lacking is sufficient regulatory oversight, comprehensive testing requirements, and transparency about how these systems are developed and deployed.

The investigation will produce recommendations. Some will be directed at Waymo specifically. Some will target NHTSA and other regulators. Some will be aimed at the industry as a whole.

The question is whether those recommendations will be heeded. Will NHTSA use the investigation's findings to establish more stringent regulatory requirements? Will Congress pass legislation giving agencies more authority and resources to oversee autonomous vehicles? Will cities and states impose additional local requirements?

Or will the investigation be treated as an interesting case study, the company will implement some fixes, and the industry will continue largely as before?

For the children in Austin riding school buses, the stakes couldn't be higher. They deserve transportation systems designed with safety as the paramount concern, not as an afterthought. They deserve regulators with the authority, resources, and willingness to demand rigorous safety validation before technology is deployed in their neighborhoods.

The investigation will reveal whether the autonomous vehicle industry is committed to that standard or whether safety remains subordinate to the drive to deploy and scale technology as quickly as possible.

FAQ

What exactly is the NTSB investigation examining?

The National Transportation Safety Board is investigating why Waymo's autonomous robotaxis in Austin, Texas repeatedly failed to stop for stopped school buses displaying stop signs and flashing red lights. The investigation will examine the technical causes of these violations, how Waymo's testing and validation processes failed to catch the problem, why a voluntary software recall didn't fully resolve the issue, and what systemic gaps in regulation allowed these incidents to occur. The investigation will produce both preliminary findings (within 30 days) and a comprehensive final report (12-24 months) with recommendations for preventing similar incidents.

Why is passing a school bus illegal, and what makes this autonomous vehicle problem unique?

All 50 states have laws requiring vehicles to stop when a school bus displays a stop sign and flashing red lights because children are entering or exiting the bus and potentially crossing the street. This rule exists for child safety. What makes Waymo's problem unique is that the technology failed to follow a law that every licensed human driver learns in driver's education. If autonomous vehicles can't reliably handle school bus scenarios—which are predictable, clearly marked with visual signals, and occur in controlled environments—it raises serious questions about whether the technology is ready for broader deployment and whether current regulatory oversight is adequate.

What does "voluntary recall" mean, and how is it different from a mandatory recall?

A voluntary recall occurs when a manufacturer identifies a problem and fixes it without being ordered to do so by regulators. A mandatory recall is issued by NHTSA when the agency determines that a safety defect exists and requires the manufacturer to address it. Voluntary recalls are generally seen as positive—they show the company is safety-conscious. However, voluntary recalls typically lack the enforcement mechanisms of mandatory recalls. With a mandatory recall, NHTSA can require specific testing procedures and detailed reporting. With a voluntary recall, the company has more discretion about how to validate the fix, which is why it's concerning that Waymo's voluntary recall didn't fully resolve the problem.

How do autonomous vehicles perceive and respond to school buses?

Autonomous vehicles use sensor fusion—combining data from cameras, lidar (light detection and ranging), and radar—along with artificial intelligence trained to recognize objects and traffic situations. To properly respond to a school bus, the vehicle needs to identify multiple elements: the yellow vehicle itself, the extended stop sign, the flashing red lights, and the overall context (vehicle is stopped, children might be present). If any part of this perception and decision-making chain fails, the vehicle might not recognize that it should stop. Waymo's system apparently failed in one or more of these areas, suggesting the AI training data, perception algorithms, or decision-making logic didn't adequately handle school bus scenarios.

What regulatory gaps does this incident reveal?

The investigation highlights several regulatory gaps: lack of prescriptive testing standards for autonomous vehicle behavior in specific scenarios (like school buses), absence of a comprehensive public reporting database for autonomous vehicle incidents, no clear protocols for what constitutes adequate validation of safety fixes before redeployment, and limited resources for NHTSA and NTSB to provide rigorous oversight. Additionally, there's no requirement that companies conduct real-world testing in actual conditions before deploying fixes—they can rely entirely on simulation-based testing, which can miss real-world factors that affect autonomous vehicle perception and response.

How long will the NTSB investigation take, and what will it produce?

According to NTSB protocol, a preliminary report will be released within 30 days of the investigation beginning. This preliminary report will document the facts of the incidents and provide initial probable cause assessment. However, the full investigation will take 12 to 24 months to complete. The final investigation report will include detailed technical analysis, findings about why the problem occurred, systemic factors that allowed it to persist, and recommendations aimed at Waymo, NHTSA, industry manufacturers, and other relevant parties. During the entire investigation period, Waymo robotaxis continue operating in Austin, which raises questions about passenger and pedestrian safety while regulators investigate.

What will happen to Waymo as a result of this investigation?

Direct consequences are uncertain because the NTSB has no enforcement authority—the agency investigates and makes recommendations but doesn't impose penalties. However, if the investigation concludes that Waymo's testing and validation were inadequate, NHTSA (which does have enforcement authority) could impose stricter requirements or impose fines for safety violations. The investigation's recommendations will also carry significant weight; manufacturers generally face public pressure and potential regulatory scrutiny if they ignore NTSB recommendations. Waymo's reputation could also be affected if the investigation reveals that the company cut corners on safety or deployed technology before adequately testing it.

How does this incident affect the broader autonomous vehicle industry?

Waymo isn't the only autonomous vehicle company operating in the United States, and the investigation's findings will likely have implications across the industry. If the NTSB recommends more rigorous testing standards or NHTSA implements stricter regulatory requirements based on the investigation, all autonomous vehicle companies would be affected. The incident also affects public perception—trust in autonomous vehicle technology could erode if incidents like this one are seen as indicative of broader safety problems. Competitors might also face increased scrutiny and questions about their own safety validation processes.

What should autonomous vehicle companies learn from this incident?

The fundamental lesson is that moving faster isn't always better. Companies should invest in more comprehensive, real-world testing before deploying technology. They should treat school bus scenarios not as edge cases but as core safety requirements. They should validate fixes more rigorously before redeployment—including real-world testing in actual conditions, not just simulation-based validation. They should also recognize that transparency and cooperation with regulators, though sometimes burdensome, builds long-term trust and prevents more severe regulatory consequences later. Finally, companies should prioritize safety over speed to market, recognizing that incidents damage reputation and public trust far more than careful, slower development.

What can cities do to improve autonomous vehicle safety?

Cities can require more stringent local safety standards before permitting autonomous vehicle operations. They can demand that companies provide detailed safety data and incident reports. They can require real-world testing in diverse conditions before approving commercial deployment. Cities can also work with schools and transportation authorities to identify potential safety issues (like school bus interactions) and require specific testing for these scenarios. Additionally, cities can establish clear protocols for what happens if autonomous vehicles violate traffic laws or cause incidents—including potential suspension of operations until problems are corrected and validated. Austin's permissive approach initially welcomed autonomous vehicles, but the school bus incidents suggest that more regulatory caution might be warranted.

How should autonomous vehicle safety compare to human driver safety?

This is a complex question because "comparing" safety involves statistical analysis across millions of miles and complex variables. The claim that autonomous vehicles are safer than human drivers is often cited by manufacturers, but the evidence is still developing. What's clear is that autonomous vehicles shouldn't be permitted to violate basic traffic laws like school bus rules simply because human drivers also break the law. The standard should be: autonomous vehicles need to be better than human drivers in critical scenarios because that's their value proposition. If they perform worse than humans in predictable, high-risk situations like school bus interactions, that undermines the case for deploying them commercially. The industry should adopt performance standards that autonomous vehicles must exceed human driver performance, particularly in safety-critical scenarios.

Key Takeaways: What the School Bus Investigation Reveals About Autonomous Vehicle Safety

The Waymo school bus investigation demonstrates that despite advanced technology and massive resources, autonomous vehicle companies can fail to implement basic, well-established traffic rules. The incident also reveals critical gaps in how autonomous vehicles are tested, validated, and regulated before commercial deployment. Until regulatory frameworks become more comprehensive and enforcement mechanisms more stringent, autonomous vehicles will continue to pose unexpected safety risks. Finally, the incident shows that transparency and public reporting of autonomous vehicle incidents and safety issues is essential for building justified public trust in the technology.

Related Articles

- Waymo's School Bus Problem: What the NTSB Investigation Reveals [2025]

- Tesla FSD Federal Investigation: What NHTSA Demands Reveal [2025]

- Tesla's Fully Driverless Robotaxis in Austin: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Waymo in Miami: The Future of Autonomous Robotaxis [2025]

- Waymo Launches Miami Robotaxi Service: What You Need to Know [2026]

- Elon Musk's Davos Predictions: Why They Keep Missing [2025]

![NTSB Investigates Waymo Robotaxis Illegally Passing School Buses [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ntsb-investigates-waymo-robotaxis-illegally-passing-school-b/image-1-1769272628409.jpg)