The Future of Urban Transportation Arrived in Miami

Waymo just pulled the trigger on something that seemed impossible a decade ago. Starting today, anyone on Waymo's waitlist in Miami can hail a driverless car. No test program. No special permission. Just open the app and go.

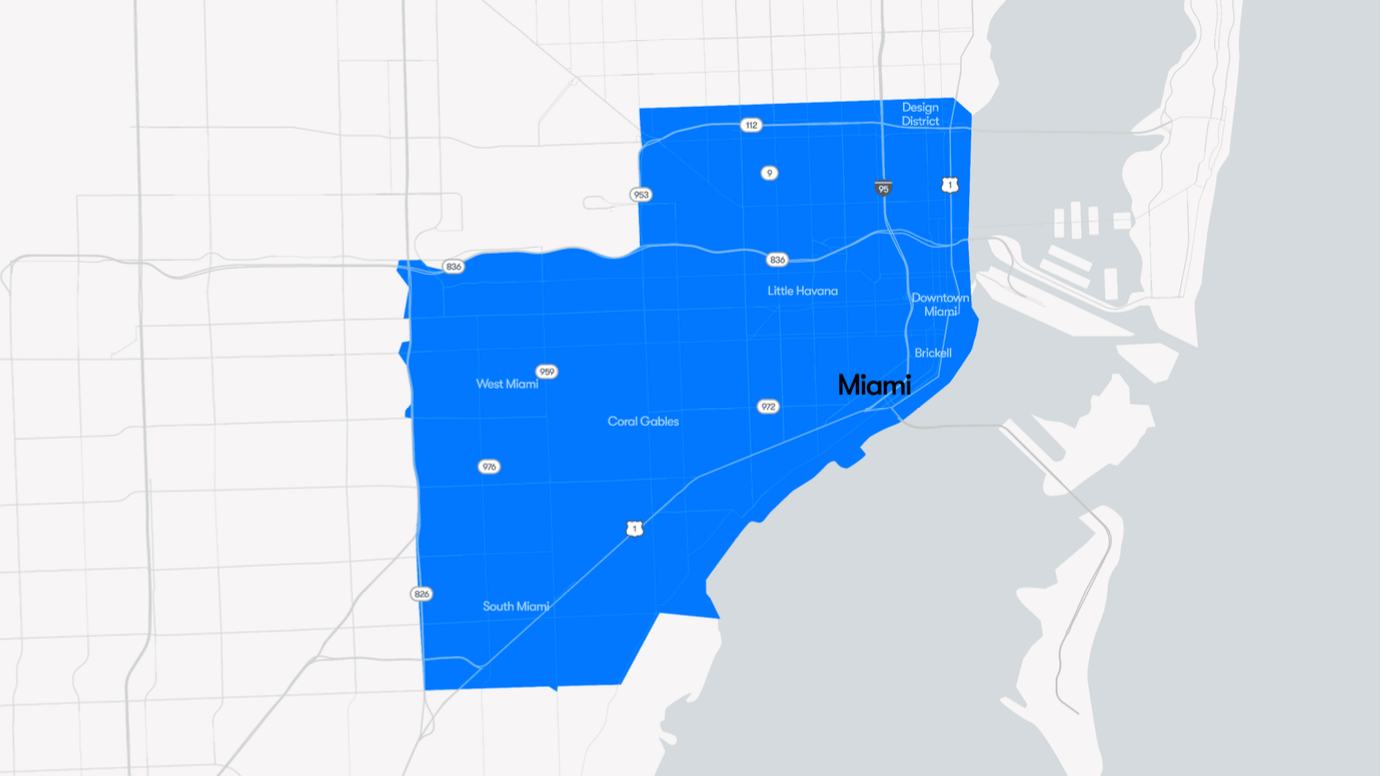

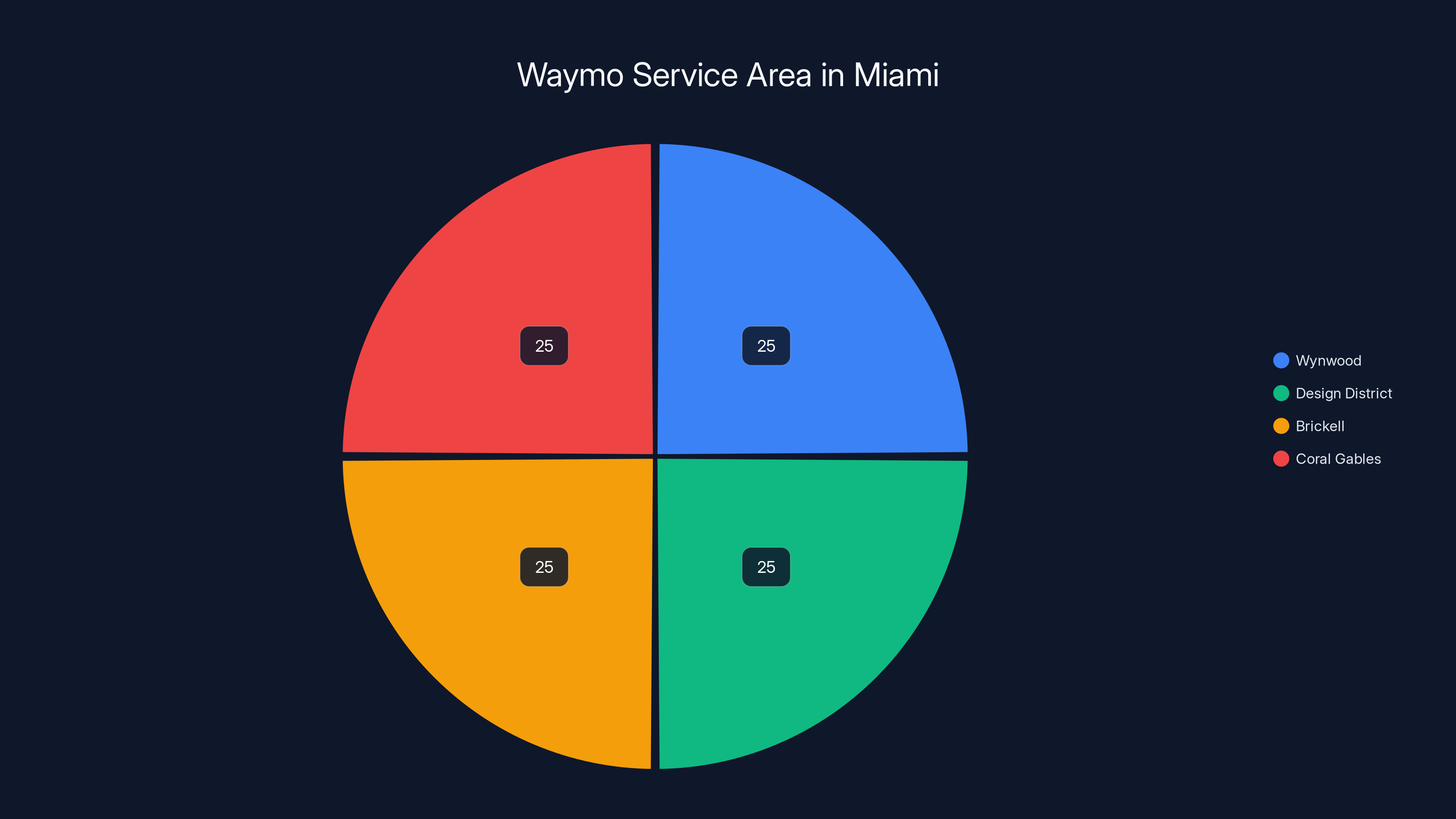

This isn't some soft-launch PR stunt either. We're talking about a functioning robotaxi network in a major metropolitan area with roughly 10,000 people already queued up to try it. The service covers 60 square miles of Miami including Wynwood, the Design District, Brickell, and Coral Gables. That's real infrastructure, real demand, and real consequences if something goes wrong.

But here's what actually matters: Miami represents Waymo's sixth official market in the United States and its first brand new city since 2025. This isn't expansion into another tech hub like San Francisco or Los Angeles where wealthy early adopters wait in line to beta test anything. This is Miami, a sprawling, chaotic, subtropical city with tourists, aggressive drivers, complex traffic patterns, and weather that makes most autonomous vehicle testing look like a joke.

The significance sneaks up on you. For years, skeptics pointed out that autonomous vehicles only work in perfect conditions in limited geographies. Waymo just proved that wrong by operating in San Francisco fog, Phoenix heat, Austin sprawl, Atlanta humidity, and Los Angeles congestion. Miami adds subtropical storms, salt-air corrosion, and some of America's worst drivers to that list.

The company won't be hiding anymore about where it's headed either. Waymo's already announced expansion plans that read like a map of America's biggest cities: San Diego, Philadelphia, Minneapolis, Tampa, Houston, Orlando, Washington DC, New York City, Denver, and New Orleans. Throw in Tokyo and London and you start seeing the actual ambition here. This isn't niche anymore. This is a transportation company planning global dominance.

So what changed? Why is a company that was testing self-driving cars in 2009 suddenly confident enough to serve 450,000 paid rides per week? And more importantly, what does Miami's launch tell us about the trajectory of autonomous vehicles over the next five years?

Understanding Waymo's Miami Service Area and Operational Boundaries

The 60-square-mile service area Waymo carved out in Miami tells you a lot about how they think about risk management. They didn't just flip a switch and allow robotaxis everywhere. They drew a careful perimeter around neighborhoods where they've tested extensively and where the traffic patterns are predictable enough to manage safely.

Wynwood's inclusion makes sense. The design and arts district attracts younger, tech-savvy residents who are more likely to use and trust autonomous vehicles. The Design District serves similar demographics with higher incomes and more acceptance of new technology. Brickell gives them access to Miami's financial center. Coral Gables provides upper-middle-class residential areas where ride demand is steady and predictable.

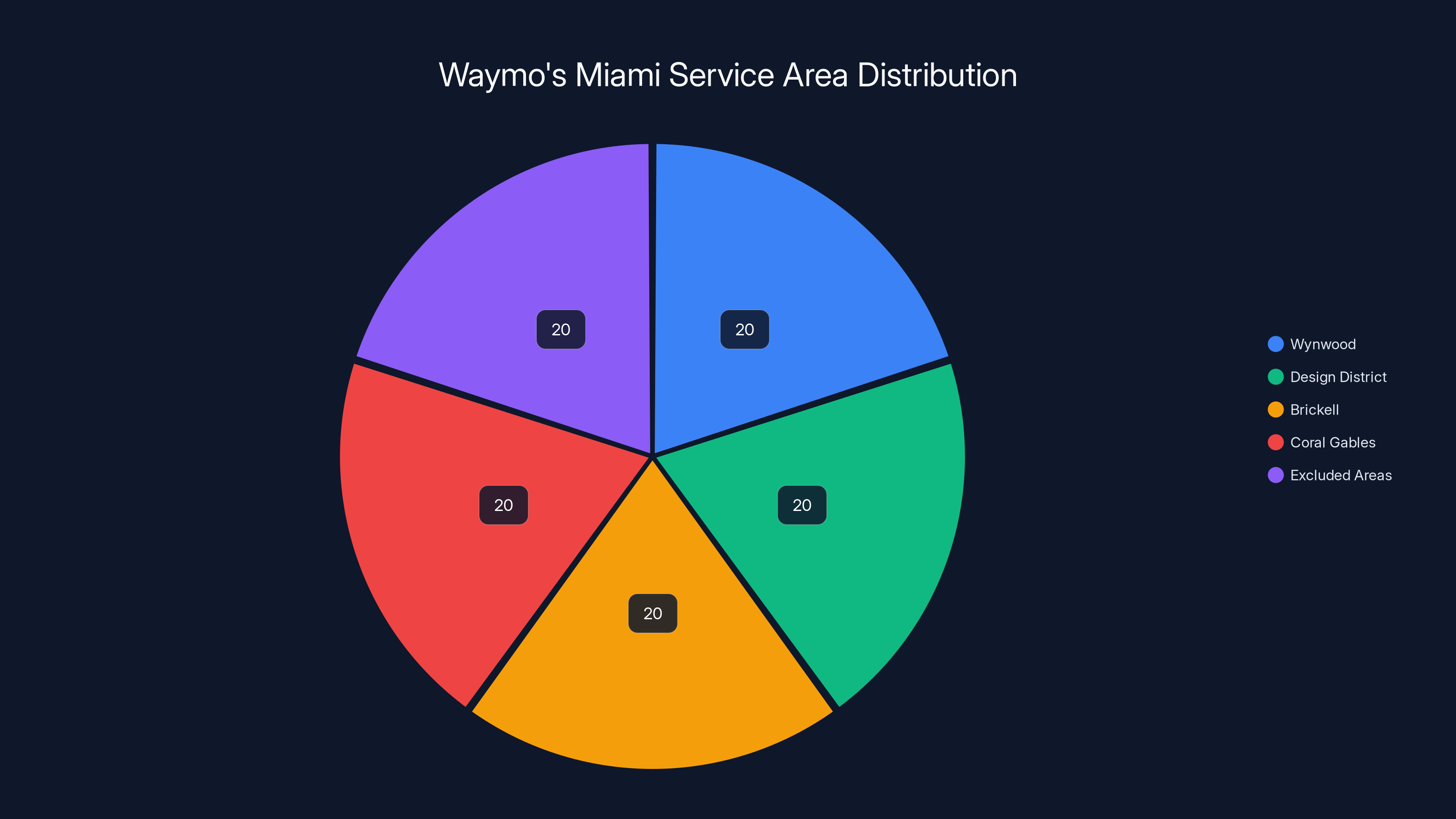

But notice what they left out: South Beach. The tourism hotspot is intentionally excluded from initial service. Why? Because South Beach is chaos. You've got rental car companies, ride-share vehicles, pedestrians who don't follow traffic rules, and congestion that would make any autonomous system work overtime. That's not a failure of Waymo's technology. That's smart operational practice. Deploy where you can succeed first, expand to harder areas later.

The initial restriction to local roads is equally telling. Highways mean higher speeds, longer reaction time requirements, and different safety challenges. Waymo isn't ready to handle I-95 rush hour yet, and they're honest about it. The plan involves expanding to faster-speed roads later in 2026, but only after accumulating enough data on how their vehicles behave in Miami's specific conditions.

This phased rollout pattern repeats across every Waymo market. They start with waitlist customers who've already expressed interest and ideally have realistic expectations. They gather dense operational data in a constrained geography. They monitor for failure modes specific to that region's climate, traffic, and infrastructure. Then they expand rings outward until they've mapped the entire city.

Miami International Airport will be the expansion prize later this year. Airport access changes everything for ride-share demand. Current estimates suggest airport trips account for 15-25% of premium ride-share revenue. Getting that right could transform Waymo's unit economics in Miami specifically.

The 60-square-mile limit also reveals something about Waymo's operational philosophy: density matters more than coverage. A smaller service area with high ride volume generates more data per mile driven. More data means faster iteration and improvement cycles. Smaller service areas are also easier to manage operationally, which becomes critical when you're proving the model works in a new city.

Waymo's weekly trips grew from an estimated 50,000 in late 2023 to 450,000 by the end of 2025, indicating steady but not explosive growth. Estimated data.

How Waymo's Safety Record Actually Compares to Human Drivers

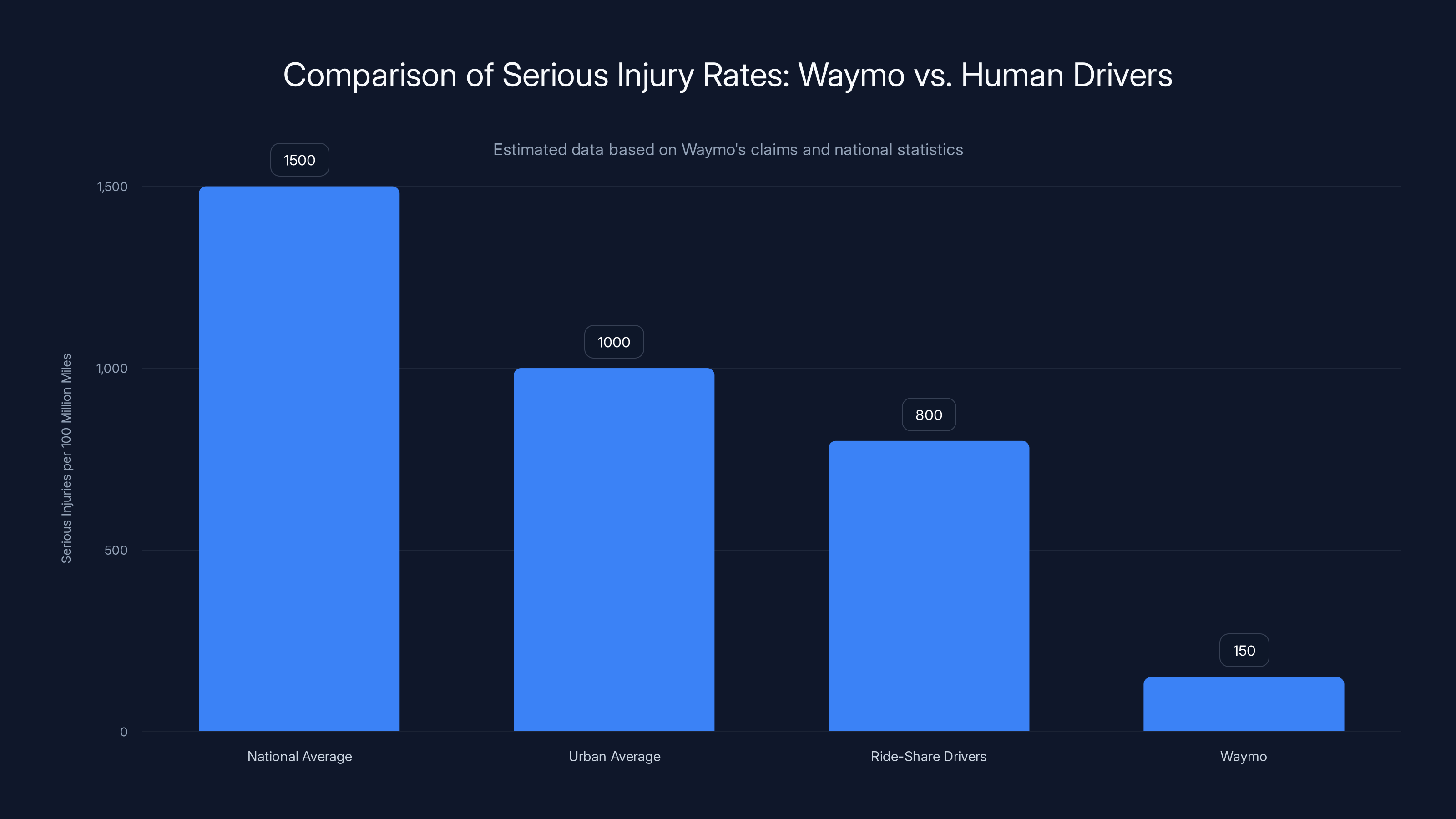

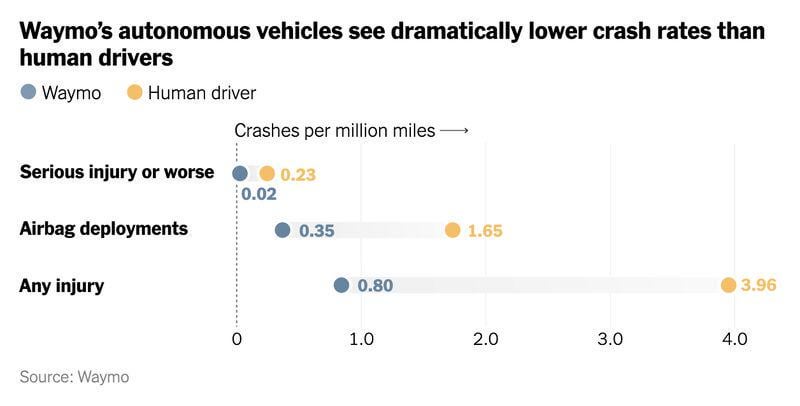

Waymo claims a tenfold reduction in serious injury crashes compared to human drivers in the cities where it operates. That's not a marketing number plucked from thin air. That's backed by actual collision data reported to regulators.

To understand what that means, you need context on human driver statistics. In the United States, there are approximately 42,500 fatal car crashes annually and another 6.5 million injury crashes. The serious injury rate is roughly 1,500 per 100 million vehicle miles traveled for human drivers. If Waymo actually operates at 10 percent that rate, they're at 150 serious injuries per 100 million miles, which would be extraordinary.

But here's where it gets complicated: Waymo's numbers come from specific urban areas where they operate. San Francisco isn't representative of national driving conditions. Neither is Phoenix or Los Angeles. Urban areas with moderate speeds have naturally lower injury rates than rural highway driving. So comparing Waymo's urban robotaxi performance to the national average human driver average is a bit like comparing a local pizza delivery driver to someone making cross-country semitruck runs.

What matters more is the apples-to-apples comparison: Waymo's safety record versus human ride-share drivers in the same geographies doing the same job. There, the data gets murky because Uber and Lyft don't publish comparable metrics the same way Waymo does. But accident reports from ride-share services suggest human drivers have serious injury rates in those exact geographies that are higher than what Waymo reports.

The tenfold improvement claim probably isn't hyperbole. But it's also not quite as impressive as it sounds when you untangle the comparison. Waymo is safer than human drivers in the specific scenarios where Waymo operates. That's genuinely significant but different from claiming they're ten times safer than all driving, everywhere.

What actually matters for Miami is whether that safety record holds up in new conditions. Miami drivers are objectively more aggressive than San Francisco drivers. Miami weather changes suddenly in ways that San Francisco never experiences. Miami infrastructure, from narrower streets in historic neighborhoods to confusing signage patterns, is different from Phoenix or Austin.

Waymo has been testing in Miami since 2019, which means they've accumulated years of local data before launching. That's not nothing. But deploying in a real service with 10,000 paying customers waiting to use you in month one creates pressure that testing never creates.

The Weekly Ride Numbers and What They Reveal About Demand

Waymo reported 450,000 paid driverless trips per week at the end of 2025. That number needs unpacking because it sounds impressive until you do the math.

450,000 trips per week means roughly 64,000 trips per day across all Waymo markets. That includes San Francisco, Los Angeles, Austin, Atlanta, and Phoenix. So the actual daily trips in any single city is somewhere around 10,000 to 15,000 if we assume roughly equal distribution, though San Francisco and Los Angeles probably skew higher.

For context, Uber processes roughly 26 million trips globally every single day. So Waymo's 450,000 weekly trips represent about 0.2 percent of Uber's daily volume. That's not insignificant for a company that started offering paid rides just a couple years ago, but it's also a reminder that Waymo isn't dominating ride-share yet. They're still in the scaling phase.

What's actually fascinating about the weekly trip number is the trajectory it implies. Waymo launched paid robotaxi service in San Francisco in late 2023. It took roughly 14 months to reach 450,000 trips per week. That's compound growth, but it's not explosive growth. Early adoption from enthusiasts and tech workers in five major metros is hitting demand ceilings that will require either expanding geographically or improving unit economics.

Miami's 10,000-person waitlist fits into that expansion strategy. If even half those people use Waymo regularly, that could add 1,500 to 3,000 trips per day to the network, pushing weekly totals toward 500,000 or beyond. But scaling from 450,000 to 500,000 is different from scaling to 5 million. The gap between current performance and real domination is still enormous.

The number also tells you something about pricing. If people are taking 450,000 paid trips per week at ride-share rates (typically

That's why Miami matters strategically. Waymo needs to prove they can reach 450,000+ weekly trips in new markets quickly. Miami's subtropical chaos is a better test of that ability than launching in another California city would be.

Waymo's serious injury rate is significantly lower than both national and urban averages, as well as ride-share drivers, highlighting its safety in specific urban areas. Estimated data.

Moove's Role as Fleet Manager and What That Means for Operations

Most articles about Waymo's expansion skip over the fleet management details and jump straight to the cars. That's a mistake because understanding Moove is crucial to understanding how Waymo actually scales.

Moove is a Nigeria-founded company that handles fleet services and financial products for mobility companies. They're backed by Uber and recently valued at $750 million. What that means practically is that Waymo doesn't own and manage its own fleet. Moove does. Waymo operates the autonomous system. Moove handles all the physical logistics of vehicle maintenance, repairs, cleaning, and replacement.

This structure is intentional. Building autonomous vehicles is hard. Managing thousands of physical vehicles, coordinating maintenance schedules, replacing parts, dealing with accidents, and handling insurance claims is a completely different business. Waymo's competitive advantage is in the software and autonomous systems. Fleet management is a commodity operation where Moove can apply economies of scale and expertise.

Moove's Uber backing matters here too. Uber has decades of experience managing ride-share fleets. Moove brings that expertise plus optimization focused specifically on autonomous vehicle logistics. That's different from managing Uber and Lyft driver fleets because autonomous vehicles have more predictable schedules, consistent wear patterns, and different maintenance needs than human-driven vehicles.

For Miami specifically, this arrangement means Waymo didn't have to set up complicated local operations. Moove can leverage existing relationships and logistics networks rather than Waymo building everything from scratch. That accelerates launch timelines and reduces local operational complexity.

It also spreads risk. If something goes seriously wrong with a vehicle or there's a major accident, Moove's insurance and legal infrastructure handles much of that. Waymo focuses on the technology. That separation of concerns is smart organizational design.

But it also creates potential tension points. If Moove makes mistakes in fleet maintenance, those failures reflect on Waymo's safety record. If Moove miscalculates the number of vehicles needed and creates service gaps, customers blame Waymo, not Moove. The integration isn't seamless because it can't be. Different companies have different incentives and priorities.

For investors watching this expansion, the Moove relationship is a positive signal. It suggests Waymo has figured out how to outsource non-core operations to capable partners rather than building everything vertically. That's the right approach for a company trying to scale rapidly.

Why Miami Specifically and What It Reveals About Waymo's Strategy

Waymo could have launched in San Diego or Tampa instead of Miami. Both cities are easier to navigate, have less aggressive traffic, and fewer extreme weather challenges. So why Miami?

The most obvious answer involves population density and ride-share demand. Miami metropolitan area has roughly 6 million people. That's a massive addressable market. Florida's population is growing faster than most states, and Miami is the epicenter of that growth. Waymo wasn't thinking about ease of operations. They were thinking about market size and revenue potential.

But there's a second reason that matters more strategically: proving the technology works in hard conditions. Every Waymo market has been relatively favorable for autonomous vehicle testing. San Francisco's mild weather and organized traffic patterns make testing easier. Phoenix is sunny and predictable. Austin's sprawl is manageable. Atlanta and Los Angeles are challenging but still operate in relatively stable weather patterns.

Miami is different. Sudden thunderstorms are normal. Salt air corrodes sensors and cameras. Rush hour traffic is objectively more chaotic than other major metros. The roads are narrower in historic neighborhoods. Pedestrians don't follow traffic rules as consistently. Traffic enforcement is inconsistent. These aren't bugs in Waymo's plan. They're features.

Launching in Miami proves that Waymo's technology isn't fragile or limited to California weather and driving patterns. It works when things are harder. That's crucial credibility for launching in Northeast winters, Southern humidity, or international markets with completely different driving cultures.

The timing also matters. January 2026 is Waymo signaling confidence coming into a new year. Tech companies often time announcements strategically around investor calendars and media cycles. Launching in a sixth major market at the start of a new year creates momentum and positive coverage heading into Waymo's next funding or acquisition conversations if they ever happen.

Miami also positions Waymo in Florida for expansion into Tampa, Jacksonville, and Orlando over the next few years. Launching one Florida city gives them the regulatory relationships and operational infrastructure to expand statewide faster than other companies could. Geography matters for business strategy, and Miami is a beachhead for Florida dominance.

The 20-City Expansion Timeline and Realistic Delivery Expectations

Waymo's ambitious expansion roadmap reads like science fiction: San Diego, Philadelphia, Minneapolis, Tampa, Houston, Orlando, Washington DC, New York City, Denver, New Orleans, Tokyo, London, and several others. The company is talking about launching in over 20 cities in the coming years.

That's either incredibly optimistic or a masterclass in setting the market's expectations before they deliver on a smaller set of actual launches. History suggests it's a bit of both.

Launching in 20 global cities is vastly harder than launching in five American metros. International markets require different regulatory approvals, different vehicle specifications in some cases, and massive local infrastructure adaptation. Tokyo's narrow streets and complex traffic rules are nothing like Phoenix's grid layout. London's left-side driving is a complete software rewrite from American deployment.

Then there's regulatory complexity. Philadelphia has different regulations than San Francisco. New York City's infrastructure makes San Francisco look simple. Washington DC has security requirements that don't exist elsewhere. Each city requires negotiation with local regulators, sometimes state-level approval, and community engagement that can take years.

Waymo's probably looking at a realistic timeline where they launch in five to seven North American cities by end of 2027. International expansion probably starts in 2027 or 2028 in one market, then accelerates if that works. Twenty-city dominance is probably a three to five-year goal, not a two-year goal.

But here's why they announce the big number anyway: it signals confidence to investors, attracts talent to the company, and starts the regulatory and community conversation in target cities years before actual launch. It's strategic communication, not a literal promise.

For Miami specifically, a realistic expectation is that Waymo goes from waitlist-only to broader public access sometime in 2026, probably mid-year once they're satisfied with the safety data and operational metrics. Airport service launches in late 2026 if everything goes well. Expansion to other South Florida cities happens in 2027.

That's not failure. That's the realistic pace of scaling a complex technology across different geographies.

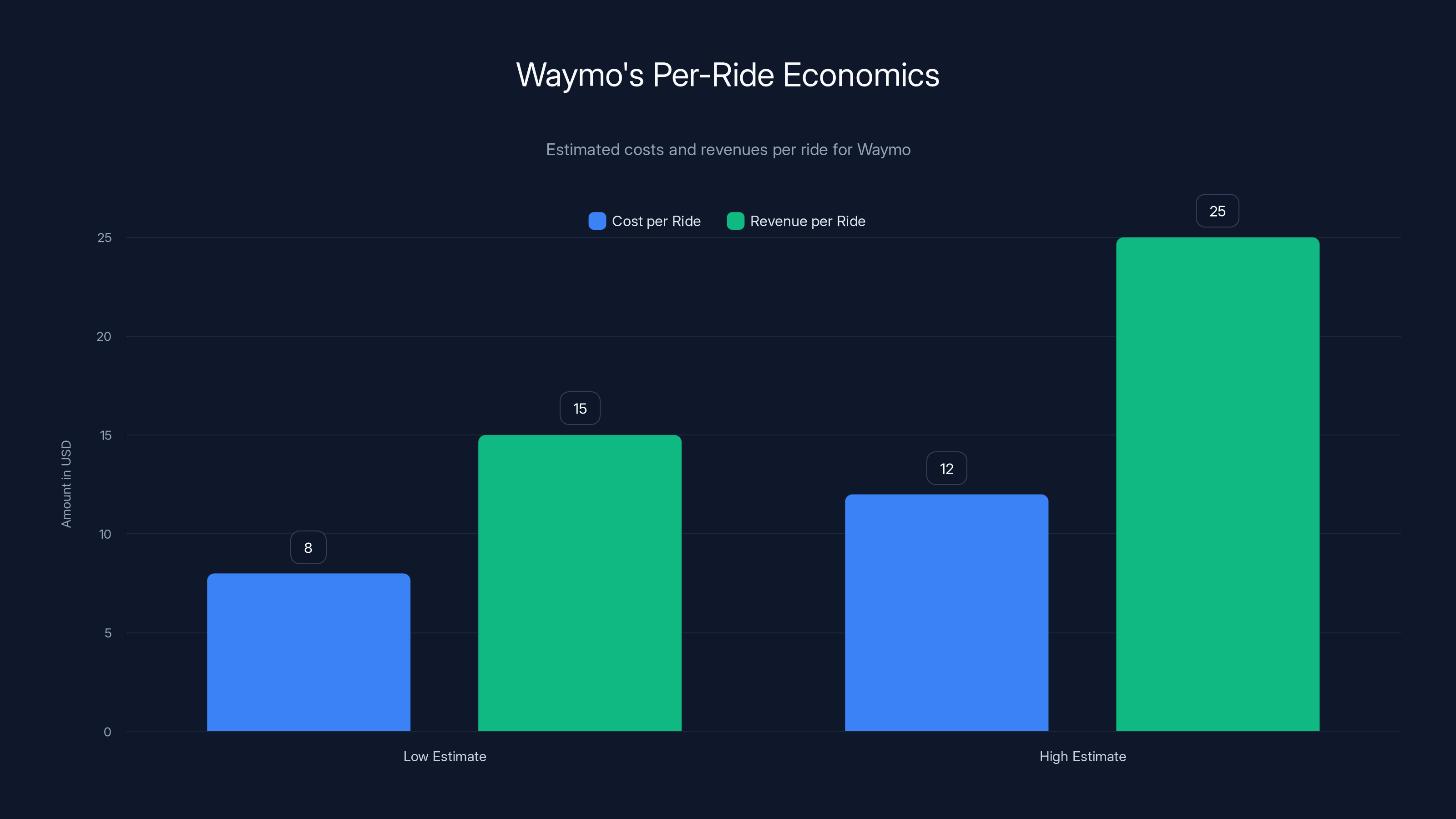

Waymo's estimated per-ride revenue ranges from

Safety Protocols and What Happens When a Robotaxi Encounters a Real Problem

Robotaxis aren't magic. They encounter situations that require human intervention. The question is whether Waymo's designed that intervention correctly.

Waymo maintains remote operators who can take control of vehicles if they get stuck or encounter unexpected situations that the autonomous system can't handle. That capability exists in every Waymo vehicle, though the company doesn't publicize exact response times or how often it's used.

The logical assumption is that remote intervention happens occasionally but not constantly. If it happened frequently, the economic model breaks. Remote operators are expensive. If you need a remote operator sitting in a control center monitoring one vehicle constantly, your labor costs don't improve over human drivers. Waymo's probably operating at a ratio where one remote operator monitors ten to twenty vehicles, intervening when necessary but not constantly.

For Miami specifically, the protocols around remote intervention probably tighten in the first months. Waymo's likely monitoring everything closely, ready to intervene earlier and more aggressively than they would in San Francisco where they have years of operational experience.

The other major safety question involves accident liability. If a Waymo robotaxi gets in a collision, who's liable? The insurance is complicated. Moove carries fleet insurance. Waymo carries manufacturer liability. The owner of the service (technically Waymo, operationally Moove) carries additional coverage. In practice, liability probably flows through multiple parties before customers ever see it.

For Miami residents, the practical effect is that riding in a Waymo is probably covered by multiple layers of liability insurance. You're not taking on uncompensated risk by using the service. That doesn't mean accidents won't happen. It means when they do, there's clear responsibility and insurance coverage.

The scarier question involves situations where the robotaxi's actions create the accident. If a Waymo robotaxi makes a sudden, unexpected turn that causes a collision, is that a software bug, a sensor failure, or just bad luck? Waymo's probably built in conservative fail-safes that make sudden unexpected behaviors less likely, but they can't be impossible. Complex systems always fail in unexpected ways eventually.

Miami's legal system will probably test these liability frameworks at some point. When it does, expect expensive litigation and regulatory scrutiny. Waymo's prepared for that in concept, but real-world litigation always goes differently than expected.

How Miami's Traffic Patterns Differ from Waymo's Other Markets

Waymo's existing markets tell a story about driving conditions. San Francisco has tech workers who follow traffic rules. Phoenix has sprawling, simple road layouts and predictable driving patterns. Austin has young drivers but relatively orderly traffic. Atlanta has bad traffic but geographic consistency. Los Angeles has chaos but chaos that's consistent across decades.

Miami is different. Miami traffic is aggressive in ways that other American cities aren't. Drivers switch lanes without signaling. Pedestrians cross against signals regularly. Delivery vehicles double-park without consequence. Traffic enforcement is inconsistent. Road infrastructure is a patchwork of historic narrow streets, new developments, and aging highways. Weather changes suddenly from clear to flooded in minutes.

That complexity is a feature for Waymo's learning algorithm. More edge cases mean more data for the neural networks that power autonomous driving. Weird situations that never happen in Phoenix definitely happen in Miami on a regular basis.

But it's also higher operational risk. If something goes wrong on a Miami road with aggressive traffic and unclear lane markings, the consequences are worse than similar failures in Phoenix. Waymo's probably expecting Miami to generate more edge cases, more remote interventions, and more safety incidents than San Francisco proportionally.

That's not a reason to avoid Miami. It's a reason to launch there carefully, which Waymo appears to be doing with the restricted 60-square-mile service area and phased expansion approach.

For riders, it means the first few months of service in Miami will probably involve slightly longer travel times as Waymo's AI errs on the side of caution in unfamiliar conditions. Conservative driving is safer than aggressive driving. By mid-2026, as the system accumulates Miami-specific data, ride times probably normalize.

Competition and How Uber and Lyft Are Responding to Waymo

Uber and Lyft can't ignore Waymo's expansion. But their response is complicated by the fact that they're ride-share networks, not autonomous vehicle manufacturers. They don't have in-house autonomous technology at the scale Waymo does. They're dependent on external partners.

Uber has invested in autonomous vehicle companies but doesn't operate its own fleet at scale. Lyft basically exited the autonomous vehicle business after struggling with the technology and costs. So both companies are in a reactive position.

Uber's most realistic path involves integrating third-party autonomous vehicles into their network as they become available. They've already announced plans to integrate Waymo and other autonomous providers into Uber's platform in select cities. That's smart strategy. Uber doesn't need to build autonomous vehicles. They need to maintain their network dominance by being the app where customers can request any type of vehicle and get transportation.

Lyft is in a weaker position. They basically need to integrate autonomous vehicles from other companies without having their own technology to offer in return. That makes them more dependent on vendors and reduces their negotiating power.

Both companies are probably lobbying regulators to impose restrictions on independent autonomous vehicle networks. The easier path for Uber and Lyft is to ensure robotaxis only operate through established ride-share platforms rather than as standalone services. That would let them maintain network effects and customer relationships even if they're not operating the vehicles themselves.

That regulatory fight is probably happening right now in Miami, San Francisco, and every other Waymo city. It's just not visible to consumers. Behind the scenes, lawyers and lobbyists are arguing about whether Waymo can operate independently or has to integrate with existing platforms.

For consumers, the outcome of that fight determines whether you can call a Waymo directly or have to call a Waymo through Uber. Both models work operationally. The difference is who owns the customer relationship and who captures the data.

Waymo currently operates in a 60-square-mile area in Miami, covering Wynwood, the Design District, Brickell, and Coral Gables equally. Estimated data.

Investment and Valuation Questions Around Autonomous Vehicle Companies

Waymo is owned by Alphabet. That's actually a huge advantage over competitors because it means Waymo has access to capital even if the business isn't profitable. Independent autonomous vehicle companies are burning through cash and need to reach profitability faster or face extinction.

But profitability timelines matter even for Alphabet-backed companies. Waymo's been operating for over a decade and still isn't profitable as a standalone business. For how much longer can Alphabet subsidize a business that loses money on each expansion?

The answer is: as long as Alphabet believes Waymo will eventually be hugely profitable. Autonomous ride-share is essentially a winner-take-most market. The first company to achieve real scale and profitability could be worth hundreds of billions of dollars. That's why Alphabet keeps funding Waymo even though it costs money today.

But if Waymo's path to profitability stretches five to ten years longer, Alphabet might get impatient. Alphabet's core business is advertising and cloud services, which are absurdly profitable. Funding a business that burns cash indefinitely isn't sustainable long-term unless the eventual return is enormous.

Miami's launch is partly about proving Waymo can scale profitably. If Miami shows that Waymo can grow revenue faster than operating costs, that's vindication of the entire strategy. If Miami shows that scaling is harder and costlier than expected, Alphabet might reconsider long-term funding.

For investors watching Alphabet, Waymo's trajectory matters because it's one of the few ways Alphabet is attempting to diversify beyond advertising. If Waymo succeeds, it's a multi-hundred-billion-dollar business eventually. If Waymo fails or stalls, Alphabet's stuck with an inherited cash-burning subsidiary with limited exit options.

Technology Prerequisites that Made Miami Launch Possible

Waymo couldn't launch in Miami five years ago because the technology didn't exist. That's not dramatic exaggeration. It's literal fact.

Autonomous driving requires Li DAR, high-definition cameras, radar, GPS, and processed computer vision. All those components have improved dramatically since 2019. Li DAR that was unreliable in rain five years ago now works in most conditions. Cameras now have better night vision and performance in challenging light. GPU chips have become powerful enough that on-vehicle processing handles most calculations without relying on cloud computing.

But the biggest prerequisite is the neural network models that power autonomous driving. Those models require massive datasets of driving scenarios, edge cases, failures, and successes. Waymo's accumulated that dataset through six years of testing in Miami plus years of testing in other cities. That data training is the real competitive moat. Other companies could theoretically build similar vehicles and sensors. They can't easily recreate Waymo's dataset.

The computing power to run these neural networks has also improved. The chips that power Waymo's vehicles are probably two to three generations newer than what Waymo was using in early testing. That means faster processing, lower latency, and better safety responses.

Miami's tropical weather also required specific technology improvements. Salt air corrodes electronics. Humidity causes sensor fogging. Sudden downpours create hydroplaning risks. Waymo's probably spent years specifically improving how their vehicles handle those conditions. That work wouldn't have been worth the investment five years ago when robotaxis weren't launching commercially. It becomes absolutely worth it once commercial service is imminent.

The underlying infrastructure matters too. Miami's roads have better GPS coverage and better mobile data availability than many cities. Without consistent connectivity and location data, autonomous vehicles can't operate safely. Waymo was probably waiting for infrastructure improvements in Miami to reach a certain threshold before committing to launch.

Public Perception and Social License to Operate

Technology doesn't spread just because it's good. It spreads when people accept it. Waymo's Miami launch depends partly on whether Miami residents think robotaxis are okay.

Early data suggests acceptance is higher than skeptics expected. Surveys show majorities in major cities saying they'd be willing to try autonomous ride-share. That's surprising given how much negative coverage autonomous vehicles get in media. But people seem willing to try new technology if they believe it's safe and economical.

Waymo's building that trust by being transparent about safety records and scaling gradually rather than flooding cities overnight. If robotaxis were everywhere suddenly, public backlash would follow. But starting with a 60-square-mile service area in tech-forward neighborhoods lets them build confidence incrementally.

Miami's waitlist of 10,000 people is the real proof of concept. Those are volunteers who specifically asked to be in this system. They're not a random sample. They're enthusiasts. But enthusiasts are how any technology adoption starts. Get the enthusiasts comfortable, then expand to mainstream users once the service is proven reliable.

The risk is that early problems create negative PR that spreads faster than Waymo can address it. One major accident gets covered nationally. Dozens of safety incidents create a narrative that these cars aren't safe. Waymo's probably expecting that risk and has strategies to manage it. But no company can perfectly control narratives once they go public.

For Miami specifically, the fact that South Beach is excluded from initial service suggests Waymo is avoiding high-visibility failures. If a robotaxi got in a collision outside a nightclub at 2 AM with tourists inside, the social media coverage would be enormous. Keeping robotaxis in more predictable neighborhoods reduces that risk, at least initially.

Waymo's Miami service area focuses on neighborhoods like Wynwood and Brickell, avoiding chaotic areas like South Beach. Estimated data.

The Path to Profitability and Unit Economics

Waymo makes money when customers pay for rides. The question is whether the revenue exceeds the costs of operating those rides.

Costs include: vehicle purchase or depreciation, maintenance and repairs, insurance, salaries for remote operators, software development, data processing, and general overhead. Current estimates from industry analysts suggest Waymo's per-ride costs are roughly

That gives a gross margin of roughly 2-4 dollars per ride if estimates are right. With 450,000 weekly rides, that's

Path to profitability requires either: increasing prices (risky because it reduces volume), decreasing costs (hard because labor and vehicles are expensive), or massively increasing volume (possible through geographic expansion). Waymo's pursuing all three strategies, but the pace matters.

Miami's significance is partly that expanding to a new city with demand from a waitlist of 10,000 people is lower-cost customer acquisition than traditional marketing. Those people showed up on their own. Waymo just has to deliver service to them.

If Miami generates $2-3 million in weekly revenue and Waymo can keep operating costs proportional to other cities, Miami becomes another node in a network that's inching toward breakeven. It's not profitability, but it's progress.

For Waymo to become truly profitable, they probably need to be operating in 10-15 major cities generating millions of daily rides collectively. That's probably a 2-3 year timeline if expansion continues at current pace. But profitability also depends on whether costs decrease as volume increases. If costs stay the same or increase, profitability remains perpetually out of reach.

Regulatory Landscape and What Approval Looked Like for Miami

Waymo didn't just decide to launch in Miami. They worked with Florida regulators, Miami city government, and probably various transportation agencies to get approval.

That approval process is invisible to consumers but crucial to understanding why some cities get robotaxis and others don't. Regulators need to be convinced that the service is safe, won't create traffic problems, and fits within existing transportation frameworks.

Florida's regulatory environment is relatively favorable to autonomous vehicles compared to some states. California has strict regulations. New York has been protective of human taxi drivers. Florida's been more permissive, partly because the state wants to attract tech companies and partly because nobody's organized effective opposition to robotaxis yet.

Miami city government probably negotiated with Waymo on various conditions: service area boundaries, insurance requirements, incident reporting protocols, and community engagement. Those negotiations happen in boring meetings that never make the news but determine whether service actually launches or stalls indefinitely.

The 60-square-mile service area is probably partly Waymo's choice about where they're confident and partly Miami's choice about where they're willing to allow it. South Beach's exclusion might be Waymo saying they can't guarantee safety there yet. It might also be Miami saying no robotaxis in our high-tourist area because of image concerns.

Regulatory approval varies by market. Some cities demand expensive insurance guarantees. Some require human monitoring. Some impose ride-sharing quotas where robotaxis have to participate in shared-ride programs. Understanding those requirements explains why Waymo can launch quickly in one city but slowly in another.

Miami's approval probably sets precedent for Florida. If Miami goes well, Tampa and Orlando probably face lower barriers to entry. If Miami has problems, other Florida cities will demand stronger guarantees. Waymo's Miami launch is essentially a regulatory test that determines how the rollout of Waymo across the Southeast proceeds.

What Doesn't Work Yet and the Honest Limitations

Waymo's expansion story sounds triumphant. But real talk: autonomous ride-share still doesn't work in many scenarios.

Rain reduces sensor effectiveness. Extreme weather forces manual control or service suspension. Night driving in poorly-lit neighborhoods is harder than daytime driving in well-lit areas. Construction zones confuse the system. Pedestrians in unexpected places create edge cases. Traffic accidents that involve emergency services require human coordination that autonomous vehicles can't fully handle.

Waymo's worked around these limitations in the cities where they operate, but they haven't solved them. They've designed systems that acknowledge limitations and either handle them carefully or call for human intervention.

For Miami, the tropical weather adds specific challenges. Sudden downpours that reduce visibility are common. Salt air gradually degrades sensors over time. Humidity creates fogging problems. Waymo's probably expecting these challenges and built systems to handle them, but unexpected failure modes probably exist.

The honest assessment is that Waymo has built autonomous vehicles that work well in most common conditions in most geographies. They haven't built vehicles that work perfectly everywhere. That honest limitation is actually why the phased rollout approach makes sense. They're testing in controlled geography first, learning from edge cases, then expanding.

For early adopters in Miami, understanding these limitations matters. Waymo works great on highways and major roads in good weather. It's less reliable in urban alleys, residential streets with parked cars, and bad weather. Experienced users probably learn which rides are reliable and which ones might need intervention.

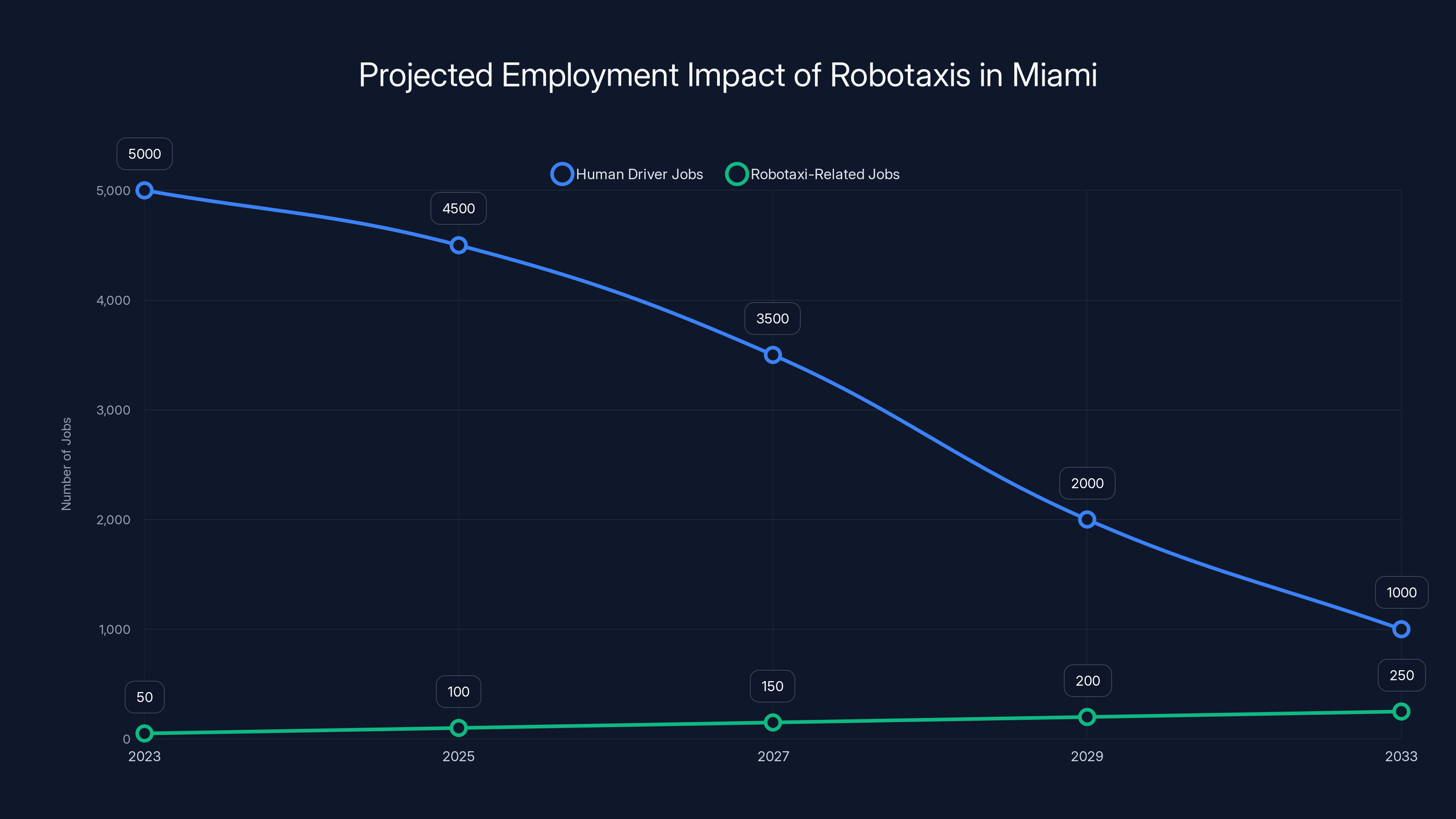

Estimated data shows a decline in human driver jobs as robotaxi-related jobs gradually increase over a decade. The transition highlights the need for strategic workforce planning.

The Waitlist Strategy and What It Reveals About Customer Demand

Waymo's got approximately 10,000 people on a Miami waitlist. That's either a huge number or a tiny number depending on how you look at it.

For a city with 6 million people, 10,000 is 0.17 percent of population. That sounds tiny. But for a niche transportation service in year one, 10,000 interested people is enormous. It's 10,000 people who voluntarily signed up and waited specifically to try this service.

The waitlist strategy serves multiple purposes. First, it reduces launch risk by starting with voluntary early adopters who have realistic expectations. Second, it creates scarcity and demand perception. "Only 10,000 people on the waitlist" sounds like a hot thing that might not be available. Third, it lets Waymo control initial volume to match operational capacity.

If all 10,000 people tried Waymo simultaneously, the system would probably overload. By releasing access gradually, Waymo can manage growth and learn from smaller volumes before ramping up.

The waitlist also generates free marketing. People on the waitlist tell their friends. Those friends want to try too. The system becomes word-of-mouth viral before it's even widely available. That's cheaper than advertising and more credible.

For Waymo, the real metric that matters is how many waitlist people actually use the service regularly versus how many try it once and abandon it. If 80% of waitlist people try it once then never use it again, that's disappointing. If 20% become regular users, that's actually good. Most new technology has that adoption pattern.

Miami's waitlist will probably determine how fast Waymo expands in Florida. If it converts well and retention is high, aggressive expansion to Tampa and Jacksonville happens quickly. If it converts poorly, expansion slows while Waymo figures out what went wrong.

Global Expansion Dreams and International Realities

Waymo's mentioning Tokyo and London in its expansion plans. Those cities sound exciting. They're also nightmares from an operational perspective.

Tokyo's roads are narrower, traffic rules are stricter, and drivers follow those rules obsessively. The autonomous vehicle would need retraining for a completely different driving environment. Sensor calibration changes. Safety requirements change. Insurance requirements change. Regulatory approval could take years.

London's got left-side driving, rain that's constant, roads that are older and poorly marked, and a public transport system so good that ride-share demand is lower than American cities. Getting approval in the UK also means navigating European AI and autonomous vehicle regulations that are stricter than American rules.

Waymo's probably serious about international expansion, but realistic timelines involve launching in Tokyo and London in 2028 or 2029, not 2026 or 2027. That's years away. It's not imminent.

The more realistic expansion story involves American cities first: San Diego, Tampa, Houston, Denver, Philadelphia. Those cities are easier to enter because the regulatory environment is simpler and Waymo's technology is already optimized for American driving patterns.

Once Waymo dominates America, international expansion becomes easier because the technology is proven and scaled. Right now, international expansion would drain resources from expanding domestically in easier markets. Smart capital allocation means finishing America first.

That doesn't mean Waymo's international plans are pie-in-the-sky. It means those plans are measured in years, not quarters. Miami's expansion is focused on proving the American model works. International comes later once that proof is solid.

Workforce and Employment Implications for Miami

Autonomous vehicles eliminate human driver jobs. That's the honest truth that doesn't get discussed enough.

Waymo's expansion to Miami means fewer jobs for taxi drivers and ride-share drivers in the long term. That's not evil. It's technological displacement, which is a real thing that happens. Some jobs become obsolete. New jobs are created elsewhere. The transition period is painful for people affected.

For Miami, Waymo's probably creating some jobs: remote operators monitoring vehicles, local maintenance staff, customer service roles. Estimates suggest maybe 50-200 jobs per city per autonomous fleet operation. That sounds good until you realize Miami's ride-share economy probably employs several thousand drivers who are now competing for fewer rides because robotaxis are doing some of that work.

The real employment change happens over five to ten years as robotaxis slowly displace human drivers. Initially, robotaxis do incremental rides. Human drivers still get work. But as robotaxis increase and human driver demand decreases, drivers exit the market. Some transition to other jobs. Some stay but make less money because surge pricing gets less frequent.

That's a public policy issue, not just a technology issue. Cities need to think about how to manage that transition. Some cities are talking about taxes on robotaxis that subsidize displaced drivers. Others are talking about restrictions on how many robotaxis can operate. Miami hasn't done much public planning on this yet, but it probably should.

For workers in Miami's ride-share economy, Waymo's arrival is interesting and somewhat threatening. It's not immediately threatening because Waymo's not immediately large. But five years from now, if robotaxis are 50% of ride volume, human drivers are having bad career conversations.

Insurance, Liability, and the Legal Questions Nobody's Answered Yet

When a robotaxi gets in a collision, who's liable? It's a genuinely hard question that courts will probably have to answer through litigation.

Traditionally, when a rideshare driver gets in an accident, the driver is liable. But a robotaxi doesn't have a driver. Waymo's liable? Moove's liable? The passenger? The other driver in the collision?

Legal theory suggests manufacturers are liable for defects in their products. Waymo built the autonomous system, so Waymo's probably liable if the accident was caused by a defect. But proving a defect was the cause requires extensive investigation. Maybe the accident was caused by sensor failure, maybe it was caused by a pedestrian stepping into traffic unexpectedly, maybe it was the other driver's fault.

Insurance arrangements determine the practical answer. Waymo probably carries insurance that covers most scenarios. Passengers sign terms of service that limit their liability. The other parties involved in a collision pursue insurance claims through established legal frameworks.

What hasn't been tested is whether those frameworks actually work in practice once real litigation starts. A major accident with significant injuries will probably create case law that changes how autonomous vehicle liability is understood. Miami might be where that happens.

For Miami residents, this probably means that if you get in a collision with a robotaxi, your injury claims go through insurance like normal. But the negotiations might take longer while lawyers argue about whether the collision was Waymo's fault, the passenger's fault, or just bad luck.

The political risk is that if major accidents happen, cities might impose strict liability on robotaxi operators regardless of fault. That would make operating robotaxis much more expensive and probably accelerate the timeline to full autonomy just to reduce human interaction liability.

The Competition from Traditional Taxi Services and Driver Advocates

Traditional taxi services are basically extinct in most American cities, but they're not gone. Miami still has established taxi and car service companies that make money from rides. Waymo's coming straight for that revenue.

Taxi companies are probably organizing opposition to robotaxi expansion. They've got political relationships and can lobby local government to create restrictions. They might demand that robotaxis operate under different rules, pay higher taxes, or face service restrictions that human drivers don't face.

Ride-share driver advocacy groups are also probably mobilizing against Waymo, but their leverage is weaker than traditional taxi services because ride-share drivers are mostly gig workers without unified organization. Uber and Lyft don't officially oppose Waymo because they can integrate Waymo vehicles into their platforms, so opposition comes from drivers themselves.

Miami city government is probably hearing from both sides: taxi companies wanting protection, driver groups wanting restrictions, plus tech advocates and consumer advocates wanting unrestricted robotaxis. The political balance determines what regulations actually get imposed.

For Waymo, local political resistance is real but probably not insurmountable. Waymo's got Alphabet's resources and has managed to navigate similar political opposition in five other cities. Miami's probably not significantly harder politically than San Francisco or Los Angeles were.

But political uncertainty adds risk to expansion timelines. If Miami city government changes and new leadership imposes strict restrictions, that could force Waymo to modify their service model or reduce investment in the market.

Looking Ahead: What the Next 12 Months Probably Look Like

If Waymo's Miami launch proceeds smoothly, the next year looks like gradual expansion within the city, introduction of airport service, and probably announcement of one or two additional Florida cities.

Other companies are definitely watching. Cruise (now owned by General Motors) is working on robotaxi deployment. Aurora (backed by Amazon and others) is testing technology. Tesla's been saying Cybercabs are coming eventually, though that timeline keeps slipping. International companies like Baidu and various European firms are working on autonomous vehicles too.

Competition will probably accelerate over the next few years. Waymo's got first-mover advantage in the United States, but other companies aren't far behind. The robotaxi market is probably going to get crowded quickly once the regulatory barriers fall fully and technology proves reliable enough.

For consumers in Miami, this probably means more choices over time. Right now, Waymo's basically the only option for robotaxi service. In 2027 or 2028, you might have choices between Waymo, Cruise, Aurora, or Tesla robotaxis depending on whose technology reaches commercial scale first.

Competition is good for consumers because it pushes prices down and service quality up. But it also means Waymo's competitive moat erodes as more companies deploy. Early dominance doesn't guarantee long-term success if competitors are executing well.

For the autonomous vehicle industry broadly, the next 12-24 months are probably the decisive period. Companies either prove their technology works reliably in real commercial service or they get displaced by companies that do. Waymo's proven reliability in five cities. Miami's the sixth test case. If Miami works well, Waymo probably accelerates expansion and cements its position. If Miami has major problems, that signals weakness that competitors will exploit.

TL; DR

-

Waymo launches in Miami: Starting today, approximately 10,000 waitlist members can hail autonomous robotaxis in a 60-square-mile service area covering neighborhoods like Wynwood, Brickell, and Coral Gables, excluding South Beach and highways initially.

-

Safety track record: Waymo claims a tenfold reduction in serious injury crashes compared to human drivers in its operating cities, with 450,000 paid trips per week across five existing markets by end of 2025.

-

Strategic importance: Miami is Waymo's sixth official market and first new city in 2026, testing autonomous systems in subtropical weather, aggressive traffic, and complex urban conditions harder than previous deployments.

-

Operational structure: Moove, a Nigeria-founded company backed by Uber, manages the fleet logistics while Waymo operates the autonomous technology, allowing both companies to focus on core competencies.

-

Profitability path ahead: Waymo's moving toward sustainable economics through geographic expansion and volume scaling, though the company likely remains unprofitable overall despite making progress in individual markets.

FAQ

What is Waymo and how does the autonomous ride-sharing service work?

Waymo is Google's (Alphabet's) autonomous vehicle division that developed self-driving taxi technology. The service works by allowing customers to request rides through an app, then autonomous vehicles pick them up and drive them to their destination without a human driver. Remote operators monitor vehicles and can intervene if necessary, but most of the time the vehicle drives itself using cameras, Li DAR, radar, and onboard AI systems.

How do I get access to Waymo in Miami and what does it cost?

Access to Waymo in Miami is currently limited to people on the waitlist of approximately 10,000 people who specifically requested access. Once you're activated from the waitlist, you can request rides through the Waymo app. Pricing is similar to traditional ride-sharing services, typically $15-25 per ride depending on distance and demand, though exact pricing hasn't been publicly disclosed for Miami specifically.

Is Waymo safer than human drivers in Miami?

Waymo reports a tenfold reduction in serious injury crashes compared to human drivers in cities where it operates. However, Miami's aggressive traffic patterns, tropical weather, and complex urban conditions present new challenges that Waymo has less operational data for. The company has been testing in Miami since 2019, but real-world commercial operation in actual traffic will provide the definitive safety assessment.

What areas of Miami will Waymo service and when?

Waymo initially covers a 60-square-mile area including Wynwood, the Design District, Brickell, and Coral Gables, but excludes South Beach and highways. The service area will expand over time to include additional neighborhoods and Miami International Airport, with airport service targeted for later in 2026 once the company accumulates sufficient operational data.

How long until Waymo expands to other Florida cities?

Waymo hasn't announced specific timelines for additional Florida cities, but if Miami proves successful, expansion to Tampa, Jacksonville, and Orlando is probable within one to two years. The company's stated goal involves 20+ cities globally, with most of that expansion happening in 2027 and beyond, but realistic timelines probably involve 5-7 North American launches by end of 2027.

What happens if something goes wrong during a Waymo ride?

If a Waymo encounters a situation it can't handle, remote operators at Waymo control centers can take over and manually drive the vehicle. For accidents or collisions, liability flows through multiple insurance layers: Waymo carries manufacturer liability, Moove carries fleet insurance, and passengers are covered by those policies. Legal liability is still being tested through courts, but practical insurance coverage appears comprehensive for typical scenarios.

Why doesn't Waymo service South Beach or highways in Miami initially?

South Beach is excluded because it's extremely congested with tourists, aggressive drivers, and unpredictable traffic patterns that would create higher safety risks for an initial deployment. Highways require higher-speed capabilities and different sensor optimization than local roads. Waymo's starting with manageable conditions to prove reliability, then expanding to harder scenarios once they've accumulated sufficient Miami-specific data.

How does Moove factor into Waymo's Miami service?

Moove handles all fleet management, vehicle maintenance, repairs, and logistics while Waymo operates the autonomous driving technology. This separation lets Waymo focus on what they do best (autonomous systems) while Moove applies their expertise in fleet operations. Moove carries fleet insurance, negotiates maintenance contracts, and manages the physical vehicle operations that keep robotaxis on the road.

Conclusion and What's Next for Autonomous Ride-Sharing

Waymo's Miami launch represents a genuine inflection point for autonomous vehicles in America. It's not the beginning of the robotaxi revolution. That started in San Francisco and evolved through four other cities. But it is proof that the technology is scalable beyond optimized test markets into genuinely challenging real-world conditions.

Miami's subtropical climate, aggressive driving culture, and complex urban geography were supposedly "too hard" for autonomous vehicles just a few years ago. Waymo's betting they're not. That's either confidence bordering on arrogance or just honest assessment of how far the technology has come. Probably both.

What happens next matters more than what happened already. If Waymo smoothly scales Miami service from waitlist to mainstream use, adds airport coverage, and expands to other Florida cities, the autonomous ride-share narrative flips decisively. It goes from "cool experiment in California" to "normal transportation option in major American cities."

If Miami hits obstacles, service gets restricted, or major safety incidents happen, the narrative gets complicated. It doesn't kill robotaxis, but it slows adoption and gives competitors time to catch up.

The waitlist of 10,000 people is the real test. Those are customers who specifically asked for this. If they find the service useful and reliable, word of mouth accelerates adoption. If they find it frustrating or limited, nobody adopts voluntarily.

For Miami residents and Florida broadly, Waymo's arrival signals that transportation is changing. Not immediately, not dramatically. But incrementally, over the next five years, the mix of human drivers, Uber, taxis, and buses will gradually shift to include autonomous vehicles. That's not inherently good or bad. It's just different. How well cities manage that transition determines whether residents experience it as improvement or disruption.

Waymo's been planning Miami since they first tested here in 2019. Seven years of preparation for a launch that happened today. That's how long getting autonomous vehicles right takes. That's also why the actual launch matters less than what comes next. The real test isn't that Waymo launched. It's whether they can keep the service running reliably, expand responsibly, and actually get to profitability in a profitable timeframe.

Miami's first robotaxi trip happened today. The next 12 months will determine whether that was a beginning or just one more milestone in a longer, harder journey than anyone predicted.

Key Takeaways

- Waymo launched its robotaxi service in Miami with 10,000 waitlist members accessing service in a controlled 60-square-mile area, marking its sixth official US market

- The company reports a tenfold reduction in serious injury crashes compared to human drivers, with 450,000 paid trips weekly across existing markets

- Miami's subtropical weather, aggressive traffic, and complex urban conditions represent a significantly harder test than Waymo's previous five cities

- Profitability remains distant but improving, with realistic timelines suggesting breakeven in individual cities over the next 2-3 years as volume scales

- Competition is accelerating with Cruise, Aurora, and Tesla developing competitive robotaxi systems, suggesting the autonomous ride-share market will be increasingly crowded

Related Articles

- New York's Robotaxi Revolution: What Hochul's Legislation Means [2025]

- Tesla FSD Federal Investigation: What NHTSA Demands Reveal [2025]

- Physical AI in Automobiles: The Future of Self-Driving Cars [2025]

- Luminar's Collapse: Inside Austin Russell's Bankruptcy Battle [2025]

- Physical AI: The $90M Ethernovia Bet Reshaping Robotics [2025]

- Hyundai's Autonomous Robotaxi: Las Vegas Launch & Future of Self-Driving

![Waymo Launches Miami Robotaxi Service: What You Need to Know [2026]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/waymo-launches-miami-robotaxi-service-what-you-need-to-know-/image-1-1769092791078.jpg)