The Great Space Compute Dream Meets Reality

When visionary entrepreneurs talk about the future of artificial intelligence, they increasingly look upward—not toward more efficient chips or clever algorithms, but literally into the sky. The premise is seductive: position data centers in orbit where solar energy flows unobstructed, where land costs nothing, and where physics itself might offer computational advantages. Yet beneath this compelling narrative lies a mathematical reality that makes traditional venture capitalists wince: a 1-gigawatt orbital data center would cost approximately $42.4 billion, nearly three times the cost of an equivalent ground-based facility.

This dramatic cost differential hasn't deterred the world's most ambitious technologists. SpaceX has petitioned regulators to launch solar-powered orbital data centers distributed across potentially a million satellites, theoretically shifting 100 gigawatts of compute power beyond Earth's atmosphere. Meanwhile, Google is developing Project Suncatcher with plans for prototype launches in 2027. Anthropic's leadership has made billion-dollar bets that by 2028, a meaningful percentage of global compute will operate in orbit. Even Amazon Web Services executives publicly acknowledge this trend as an inevitable part of the future infrastructure landscape.

But recognizing a future doesn't make it economically viable today. The gap between aspirational vision and practical execution encompasses multiple engineering challenges, unprecedented manufacturing requirements, and fundamental physics constraints that have never been overcome at scale. Understanding orbital AI requires examining not just the technology itself, but the intricate economic machinery that would need to function flawlessly for space-based computing to replace even a fraction of terrestrial data center capacity.

This article deconstructs the brutal economics of orbital AI, analyzing why costs remain prohibitively high, what technological breakthroughs would be required, and whether the vision can realistically materialize within the timelines being publicly promoted.

Understanding the Cost Structure: Why Space Isn't Cheap

The Launch Cost Foundation

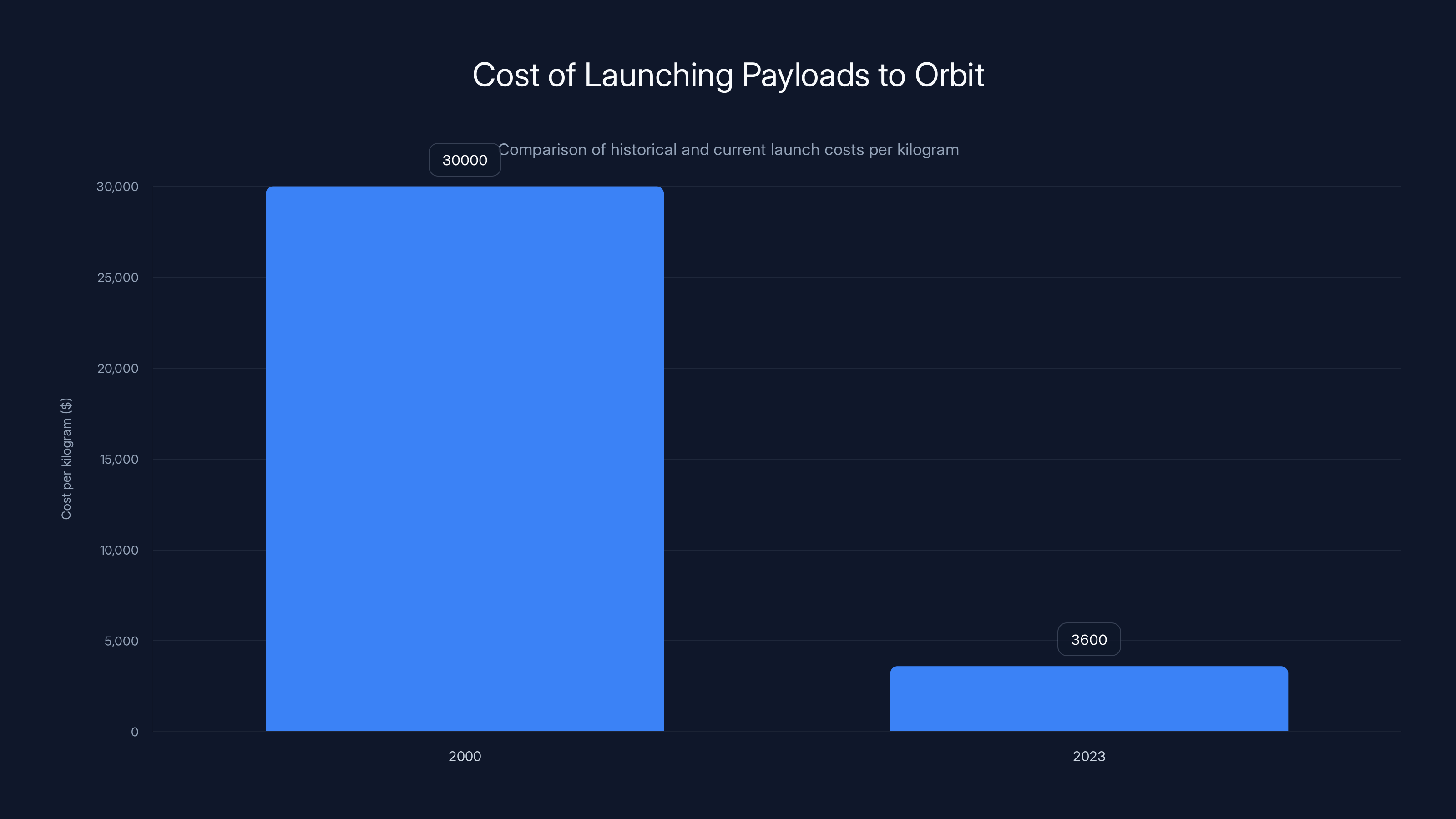

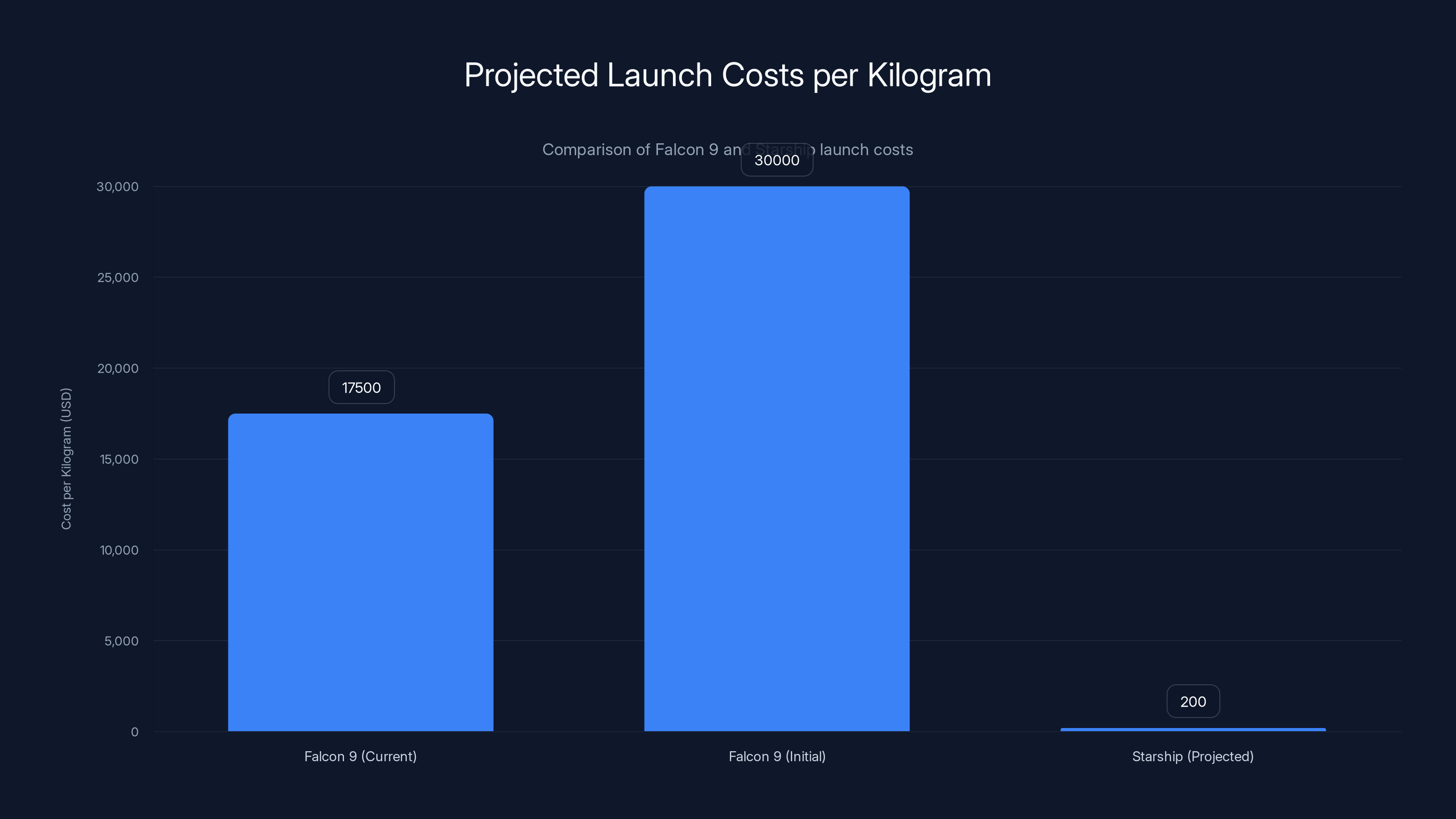

Every orbital data center begins with a single, irrefutable problem: getting mass into space is extraordinarily expensive. Currently, SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket delivers payload to orbit at approximately

To illustrate this reality with concrete numbers: a single modern satellite weighing 500 kilograms incurs launch costs of approximately $1.8 million before any design, manufacturing, or operational considerations. Multiply this across the projected constellation of a million satellites, and launch costs alone approach figures that exceed the gross domestic product of small nations.

The fundamental constraint is physics itself. Reaching orbital velocity requires accelerating mass to 7.8 kilometers per second while overcoming gravitational pull and atmospheric drag. Every kilogram represents stored energy that must be released through combustion of exotic fuels. The Tsiolkovsky rocket equation—the mathematical foundation of all spaceflight—dictates that the relationship between payload and fuel is exponential, not linear. Doubling your payload doesn't require twice the fuel; it requires dramatically more.

Manufacturing and Component Costs

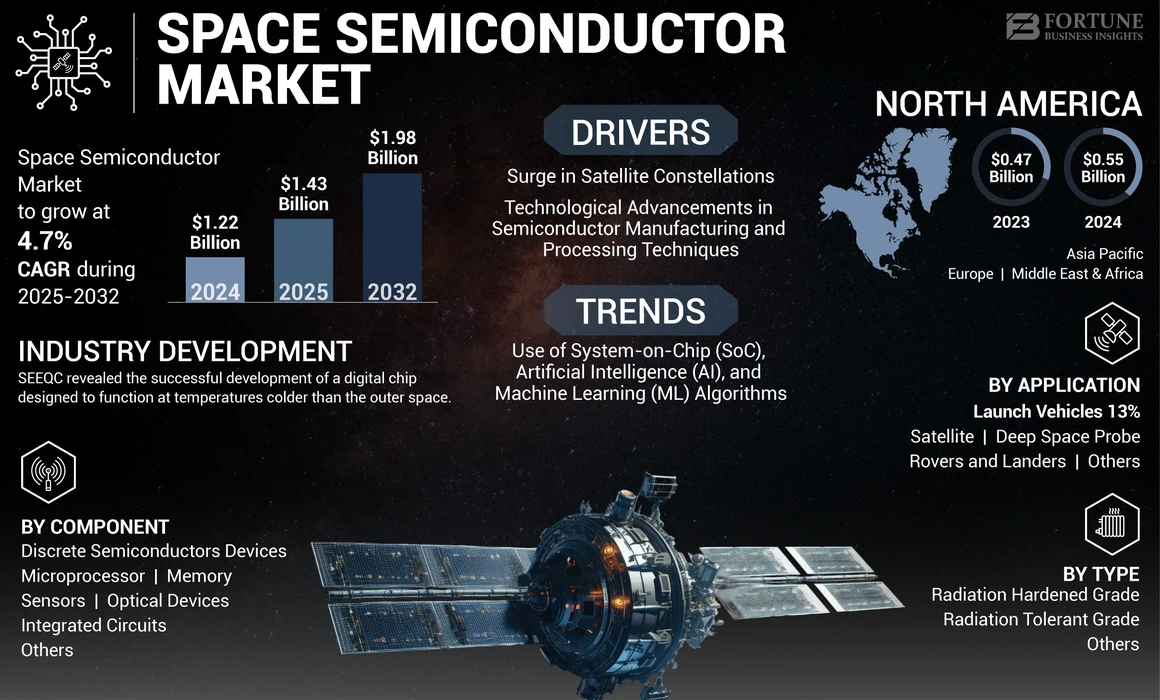

Yet launch costs represent only one component of the total equation. Manufacturing satellite-based data centers introduces requirements that terrestrial facilities never encounter. Space-grade components—processors, memory systems, power conversion equipment—must operate in radiation-saturated environments where conventional semiconductors degrade over time. They require redundancy systems, shielding, and thermal management approaches fundamentally different from ground-based cooling towers.

Current satellite manufacturing costs average approximately

These manufacturing costs represent the largest component of the total $42.4 billion equation. While launch costs scale with quantity (more satellites require more launches), manufacturing costs scale with specifications. Every specification improvement—higher performance processors, greater redundancy, extended operational lifespan—pushes manufacturing costs upward. The challenge facing orbital data center developers is that competitive terrestrial data centers continue improving their cost curves through established manufacturing optimization, creating a moving target that space systems must chase.

Depreciation and Operational Lifespan

Another critical but often overlooked cost factor is the operational lifespan of space-based hardware. Terrestrial data centers often operate productively for 10-15 years, with equipment refresh cycles allowing for technology improvements and gradual cost recovery. Orbital systems face different constraints.

Satellites in low Earth orbit experience atmospheric drag that gradually decreases altitude. Within 10-20 years, even a satellite launched into standard operational orbit will begin deorbiting, eventually burning up in reentry or crashing. Space debris collisions pose constant risk—even small objects traveling at orbital velocity carry kinetic energy equivalent to explosions. Radiation exposure degrades semiconductors over time, reducing performance and reliability. The operational window for current satellite technology is significantly shorter than terrestrial facilities.

This creates a depressing financial reality: the capital investment in an orbital data center must be fully amortized within perhaps 8-12 years, while terrestrial facilities spread identical investments across 15+ year periods. This compressed timeline inflates the per-year cost burden, making unit economics substantially worse than initial capital cost comparisons might suggest.

Orbital data centers are significantly more expensive than terrestrial ones, primarily due to launch and manufacturing costs, which are absent in terrestrial facilities.

The Falcon 9 Baseline and Starship's Uncertain Promise

Current Economics with Reusable Rockets

SpaceX's Falcon 9 represents the current state-of-the-art for cost-effective launch services. By developing reusable first stages that return to Earth for reflight, SpaceX achieved a revolutionary improvement in launch economics. The first Falcon 9 flight cost approximately $60 million; modern missions cost roughly half that, with marginal costs per kilogram remaining constant. This innovation fundamentally shifted the space industry's trajectory, enabling mega-constellations like Starlink that would have been economically impossible just five years earlier.

Yet even reusable rocket economics appear insufficient for orbital data centers at contemporary pricing. SpaceX currently charges approximately

The Starship Equation

This is where SpaceX's Starship enters the narrative. The second-generation orbital launch system promises revolutionary improvements: massive payload capacity (up to 150+ metric tons), full reusability of both first and second stages, and potential launch costs approaching $200 per kilogram. Google's Project Suncatcher white paper specifically identifies Starship-level pricing as the breakeven point for orbital data center economics.

However, Starship represents an engineering frontier that remains largely theoretical from an operational standpoint. The vehicle has not yet completed an orbital flight test. Multiple test flights have experienced failures or partial successes. The engineering challenges are monumental: full-stack reusability requires heat shield systems that withstand 2,800-degree Fahrenheit reentry temperatures, fuel management systems that function across 200-million-cubic-meter tanks, and reliability standards demanding that failures become statistically rare events.

Historical precedent suggests cautious optimism tempered with realistic skepticism. The Space Shuttle promised revolutionary improvements over expendable rockets through reusability, yet it never achieved the cost reductions its architects envisioned. Thermal protection systems required extraordinary maintenance between flights. Turnaround times between launches remained measured in months rather than weeks. The Shuttle eventually cost more per flight than conventional rockets despite its sophistication.

Pricing Dynamics in a Competitive Market

Assuming Starship achieves its theoretical capabilities, another economic reality deserves consideration: SpaceX's actual pricing may diverge substantially from what orbital AI developers hope. The company faces a classic business economics problem: if launch costs drop dramatically, SpaceX must decide whether to dramatically reduce pricing or maintain prices near competitive levels and capture the margin as profit.

Blue Origin's New Glenn rocket, though years behind Starship in development, targets similar technological achievements and promises competitive pricing around $70 million per flight. If New Glenn reaches operational status offering comparable performance, SpaceX faces pressure to maintain price parity or lose customers. But maintaining price parity while operating Starship at half the cost provides extraordinary profit margins—precisely what any rational business would pursue.

Consultancy analyses suggest that even with Starship's technical success, actual prices available to external customers may remain 2-3 times higher than engineering cost models suggest. This gap between theoretical unit costs and actual market pricing could perpetually disadvantage orbital data center economics relative to terrestrial alternatives improving through conventional optimization.

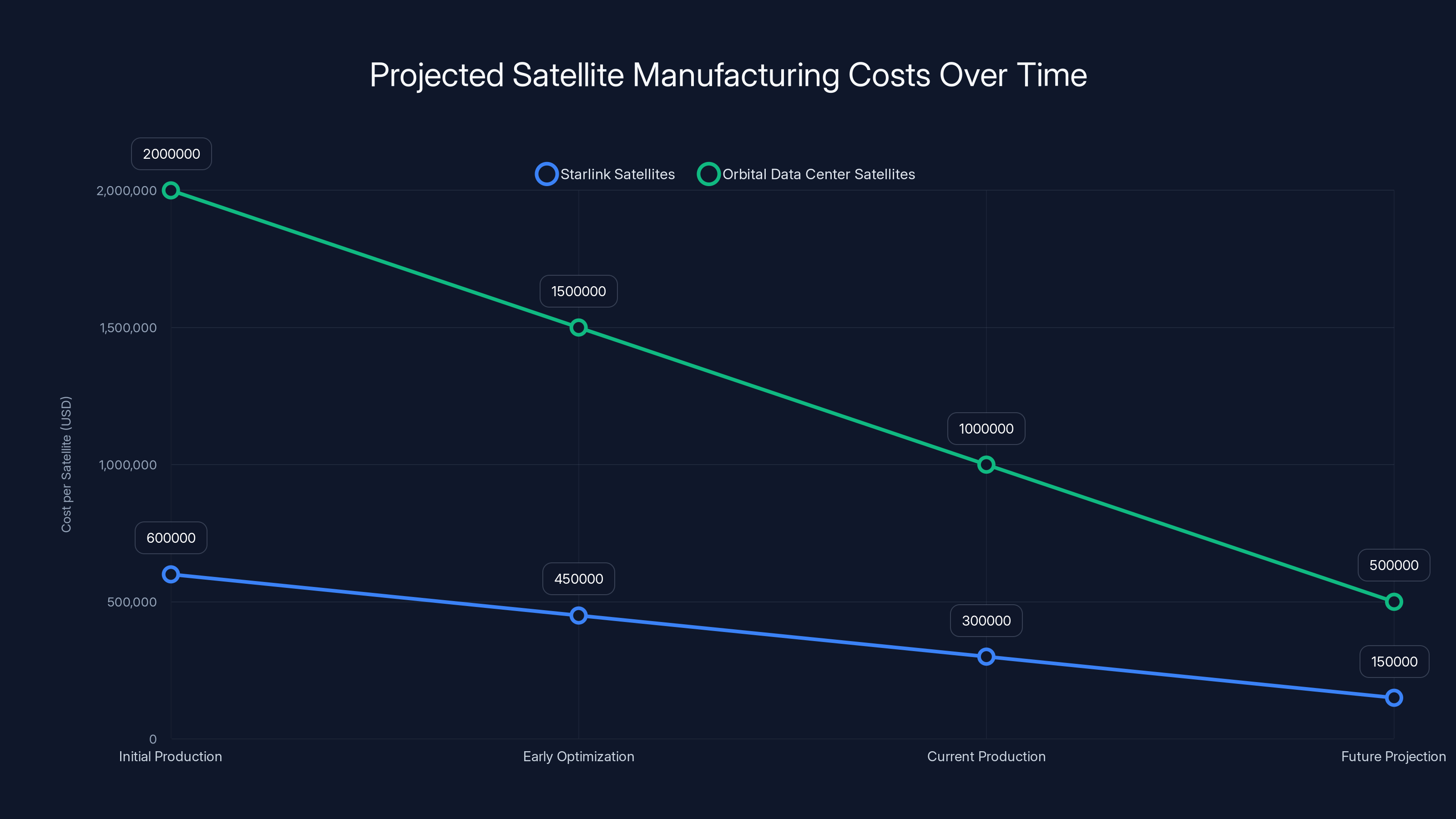

Estimated data shows potential cost reductions for orbital data center satellites, mirroring Starlink's cost optimization trajectory. Initial costs are higher due to complexity, but could halve with scale.

Satellite Manufacturing: Scaling the Unsealed Constraint

Current Production Economics

Building a million satellites represents a manufacturing challenge without historical precedent. SpaceX's Starlink constellation, the largest satellite deployment to date, involves thousands of units, not millions. Each Starlink satellite weighs approximately 260 kilograms and costs roughly $300,000 to manufacture and deploy. The company has invested billions in automated manufacturing facilities to achieve these unit economics.

A 1-gigawatt orbital data center might require 5,000-10,000 satellites, each significantly more sophisticated than Starlink units. These would need powerful processors capable of executing AI workloads, redundant memory systems, precise power management, and thermal regulation systems managing heat dissipation in the vacuum environment. Current engineering estimates suggest manufacturing costs in the

The cruel mathematics: if each satellite costs

The Promise and Problem of Scale Manufacturing

Proponents of orbital AI argue that manufacturing costs will fall dramatically as production volumes increase. SpaceX achieved roughly 50% cost reductions in Starlink manufacturing between early and current production, through optimization, automation, and supply chain improvements. Could similar improvements apply to orbital data center satellites?

Potentially, yes—but with important caveats. Starlink optimization benefited from extraordinary production volumes (thousands of units annually) and relentless focus on manufacturing efficiency. Replicating this for orbital AI satellites requires similar commitment levels and volumes. Yet predicting that volumes will reach levels justifying such investment requires confidence that orbital data centers will become economically viable—a circular dependency that leaves investors uncertain.

Moreover, the components used in space systems face fundamental constraints that terrestrial manufacturing doesn't encounter. Space-qualified microprocessors cannot use the most advanced semiconductor nodes available to terrestrial data centers; they instead use older, proven designs that offer reliability over bleeding-edge performance. The radiation-hardened memory required for orbiting systems uses older technology. Power conversion and thermal management systems require exotic materials and precision construction that don't respond to conventional cost-reduction approaches.

Supply Chain Realities

Building thousands of satellites annually would require dedicated supply chains for hundreds of specialized components. Radiation-hardened processors require dedicated foundries with years-long lead times. Specialized thermal materials must be sourced from limited suppliers. The semiconductor industry's already-strained supply chains would face additional pressure from simultaneous demand for space-qualified components.

Historically, space manufacturing has operated in a world of scarcity—small volumes, specialized suppliers, and acceptance of long lead times and premium pricing. Scaling to millions of units would require transforming this entire ecosystem. New suppliers would need to qualify for space applications (a 2-3 year process requiring extensive testing). Existing suppliers would need to add capacity (expensive, risky if demand turns out to be temporary).

Unlike Starlink, which provides clear revenue through internet services, orbital AI data centers would be unproven commercial ventures. Suppliers facing requests to invest in new capacity for an untested market would demand premium pricing, extending cost curves far beyond optimistic projections.

Thermal Management: Physics' Penalty in Vacuum

The Cooling Challenge at Orbital Temperatures

Terrestrial data centers rely on a simple but elegant solution to manage the intense heat generated by processors: air and water. Fans pull ambient air across hot components; water circulation systems capture and redistribute thermal energy. Data centers typically reject waste heat at 30-40 degrees Celsius above ambient, efficiently and reliably.

Orbital systems encounter a fundamentally different problem. In the vacuum of space, traditional convection cooling doesn't exist—there is no air to move heat away from components. Heat dissipation must occur through radiation, the process by which objects emit electromagnetic radiation proportional to their absolute temperature raised to the fourth power. This means cooling efficiency decreases dramatically as systems get hotter.

For a 1-gigawatt data center generating perhaps 200-300 megawatts of waste heat (assuming 70-80% power efficiency), radiative cooling alone requires enormous surface areas maintained at manageable temperatures. A satellite-based data center would need radiator panels covering hundreds of square meters, adding mass, complexity, and cost.

Materials Science and Operating Temperatures

Computers generate heat because electrical current flowing through resistive materials produces thermal energy as described by Joule's law:

Orbital radiators operating in vacuum face a different constraint: they radiate heat away based on the Stefan-Boltzmann law, which states that power radiated is proportional to the fourth power of absolute temperature:

This creates an engineering tension: computers need to stay cool (preferably below 80 degrees), while radiators must operate hot (perhaps 80-100 degrees) to efficiently reject heat. Achieving this temperature differential across orbital systems requires sophisticated thermal transport systems using heat pipes, liquid loops, or other advanced technologies. Each adds mass, complexity, power consumption, and cost.

Secondary Effects and Cascading Costs

Higher operating temperatures reduce processor reliability and lifespan. Every 10-degree-Celsius increase in operating temperature roughly halves semiconductor lifespan. Operating orbital processors at temperatures 10-20 degrees higher than terrestrial data centers dramatically reduces expected operational life, compressing the window for cost amortization.

Thermal cycling poses another challenge. Satellites experience dramatic temperature swings as they orbit into Earth's shadow and back into sunlight—potentially 100-degree-Celsius or greater variations across 90-minute orbital periods. This thermal cycling causes stress on components, solder joints, and materials, promoting fatigue failures that ground systems simply don't experience.

Moreover, the radiator panels themselves represent mass and drag. Additional mass increases launch costs; additional surface area increases atmospheric drag in low Earth orbit, requiring periodic reboost maneuvers burning fuel to maintain altitude. These reboost burns represent ongoing operational costs that terrestrial facilities never encounter.

Launch costs have significantly decreased from

Power Generation in Space: The Solar Advantage and Disadvantage

The Promise of Unobstructed Solar Energy

Orbital AI evangelists frequently cite solar energy as a major cost advantage. In space, solar panels receive continuous, unobstructed sunlight during orbital day periods (roughly 45 minutes per 90-minute orbit for low Earth orbit), with intensity approximately 1,361 watts per square meter—the solar constant. Modern photovoltaic panels achieve 30-35% efficiency in space environments, substantially higher than terrestrial installations achieving 15-20% due to atmospheric absorption and angle-of-incidence effects.

A 1-gigawatt data center would require approximately 3-4 square kilometers of solar panels to supply peak power. These massive arrays would need to track Earth as the satellite orbits, maintaining optimal angle with respect to the sun. The engineering is challenging but theoretically feasible—space stations and countless satellites employ solar arrays of substantial scale.

Intermittency and Energy Storage Challenges

However, the advantage of abundant solar energy carries a significant penalty: intermittency. Every 45 minutes, as satellites enter Earth's shadow, solar generation drops to zero. The data center must either shut down, reduce power, or draw from stored energy reserves. All three options present problems.

Shutdown or power reduction means data center workloads cannot maintain continuous operation. Customers expect their AI computations to run without interruption. This requires massive battery or energy storage systems capable of maintaining 1-gigawatt operations for 45-minute shadow periods. Current battery technology would require weight and volume equivalent to multiple rocket launches just for energy storage, adding billions in costs and mission-critical failure modes.

Alternatively, redundant solar arrays could be deployed such that multiple satellites collectively maintain coverage. But this requires deploying far more solar panel area than minimal requirements, further increasing mass and launch costs. The economics rapidly degrade as redundancy increases.

Thermal Management of Solar Arrays

Another overlooked challenge: solar arrays themselves generate thermal issues. Panels convert roughly 30% of incident solar energy to electricity; the remaining 70% becomes heat. Thousands of square kilometers of solar arrays collectively generate tremendous heat, potentially warming the satellite constellation and complicating thermal management.

Further, solar panels degrade over time due to radiation exposure, micrometeorite impacts, and thermal cycling. A 10-15 year operational lifespan might see 20-30% efficiency loss. This means deployed systems degrade continuously, requiring either replacement of panel segments or acceptance of declining power availability and computational capacity.

Power Consumption: The Computational Demand Reality

AI Workload Characteristics

Large language models and transformer-based AI systems consume extraordinary power. Training a large model can consume megawatt-hours; inference workloads require sustained power levels based on model size and throughput requirements. A model with billions of parameters might consume 100-500 watts continuously during inference, scaled up across thousands of requests.

A 1-gigawatt orbital data center would theoretically support computational capacity equivalent to 1,000 megawatts of continuous processing. In practice, power efficiency matters tremendously. Modern data centers achieve power usage effectiveness (PUE) of 1.1-1.3, meaning overhead from cooling, power conversion, and management adds only 10-30% to raw computational power consumption.

Orbital systems face worse PUE due to space-specific challenges: radiation shielding consumes power; thermal management requires active systems; power conversion and distribution systems are less efficient. PUE might reach 1.5-2.0, meaning the data center consumes 1.5-2 watts of energy for every watt of computational power delivered.

Demand vs. Supply Mismatch

Here emerges a critical economic tension: AI compute demand is growing, but it's not distributed evenly across the globe. Large AI training and inference occurs predominantly in North America, Europe, and parts of Asia. An orbital data center in low Earth orbit passes over every latitude on Earth, but spend time over computing demand centers during only a fraction of its orbit.

A satellite passing over the Atlantic Ocean provides no value serving European data center customers; it must wait until it completes a quarter-orbit to again pass over Europe. This means customers cannot reliably route their workloads to a specific satellite. Instead, workloads would need to be distributed across constellations, with sophisticated scheduling systems managing job assignment.

This distribution challenge introduces latency. A customer in New York hoping to connect to nearby orbital processing might experience latency of 100-300 milliseconds as data travels to space and back, compared to sub-10-millisecond latency to ground-based data centers. For interactive applications, this latency proves prohibitive. For training workloads that don't require constant interaction, latency matters less but still represents inefficiency.

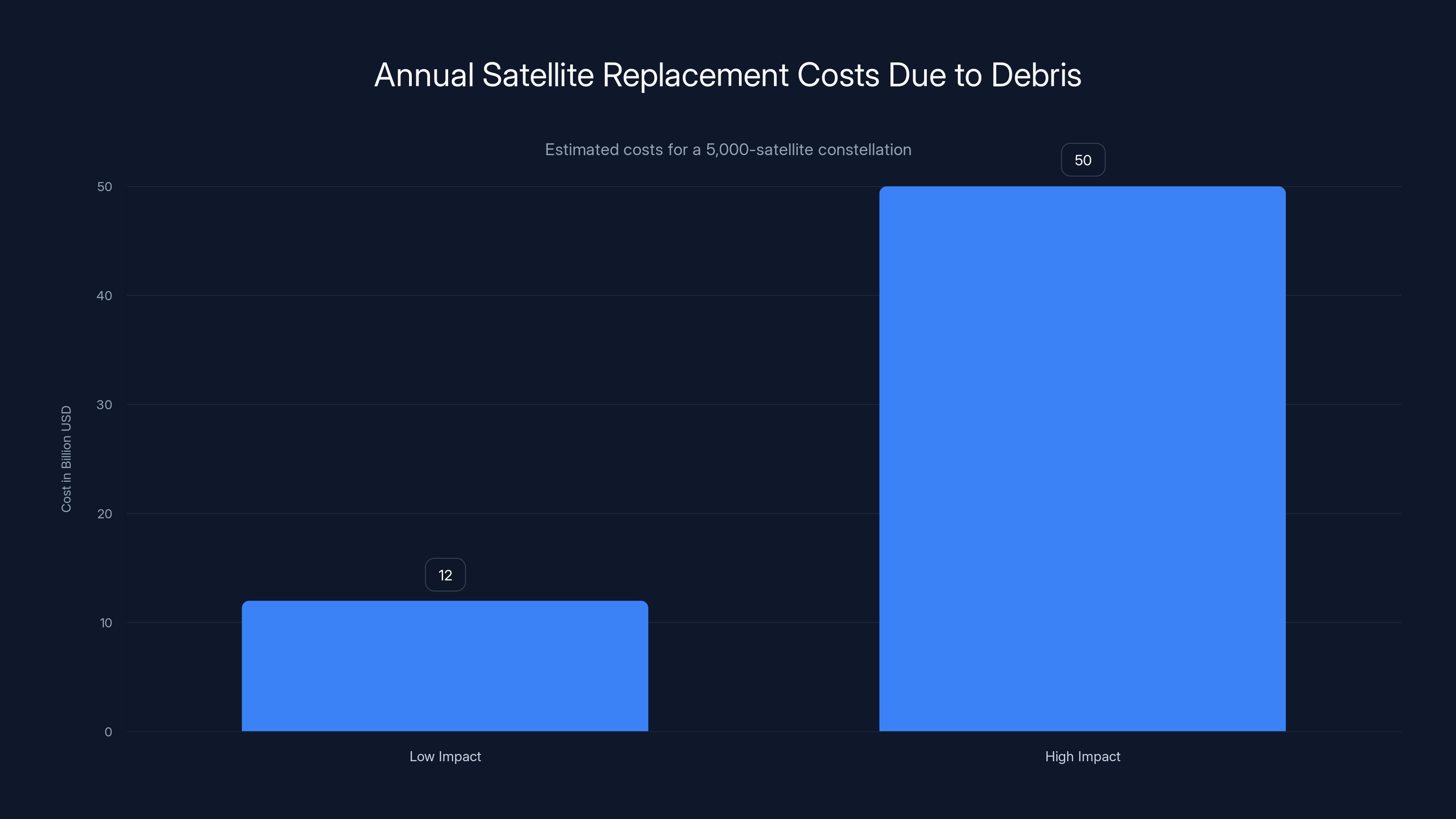

Estimated annual replacement costs for a 5,000-satellite constellation range from

Reliability, Redundancy, and Operational Complexity

Single Points of Failure in Extreme Environments

Terrestrial data centers achieve exceptional uptime (typically 99.99%+) through redundancy and geographic distribution. If one facility experiences issues, traffic routes to others. If cooling systems fail, maintenance teams arrive within hours. If power distribution encounters problems, trained technicians troubleshoot and repair.

Orbital systems lack these safety nets. A satellite experiencing component failure cannot be repaired on-orbit with current technology. It either continues operating in degraded mode or must be replaced entirely. The replacement process requires a rocket launch, regulatory approvals, orbital reboost of the failed unit, and deployment of a new satellite—processes taking weeks or months.

For a constellation to maintain desired uptime levels, substantial redundancy is required. Instead of deploying 5,000 satellites to meet peak demand, perhaps 8,000-10,000 are needed to maintain service despite continuous failures. This multiplicative effect dramatically increases total constellation costs.

Orbital Debris and Collision Risk

Orbital space at popular altitudes (300-500 km) increasingly resembles a crowded marketplace. Thousands of active satellites orbit, along with thousands of pieces of debris from past launches and collisions. A 10-kilogram piece of debris striking a satellite traveling at 7,800 meters per second carries kinetic energy equivalent to a car traveling at highway speeds. Such collisions catastrophically damage satellites.

The risk is measurable: statistically, a large satellite constellation loses 0.5-2% of satellites annually to micrometeorite impacts and debris collisions. For a 5,000-satellite constellation, this means 25-100 satellites require replacement annually. At

Regulatory and Coordination Challenges

Launching a million satellites requires coordinating with global regulatory bodies: the International Telecommunication Union, Federal Communications Commission, and equivalent bodies worldwide. Each nation's airspace and orbital authority has jurisdiction. Avoiding collisions with other constellations requires coordination with SpaceX's Starlink, Amazon's Project Kuiper, and numerous other operators.

Each regulatory approval takes time and creates uncertainty. Disputes over spectrum allocation, orbital slots, or debris remediation could delay deployments indefinitely. Unlike terrestrial infrastructure where a company can build and operate independently, orbital constellations exist in a commons requiring international cooperation.

Comparing Orbital and Terrestrial Economics: The Cost Model

The $42.4 Billion Baseline Analysis

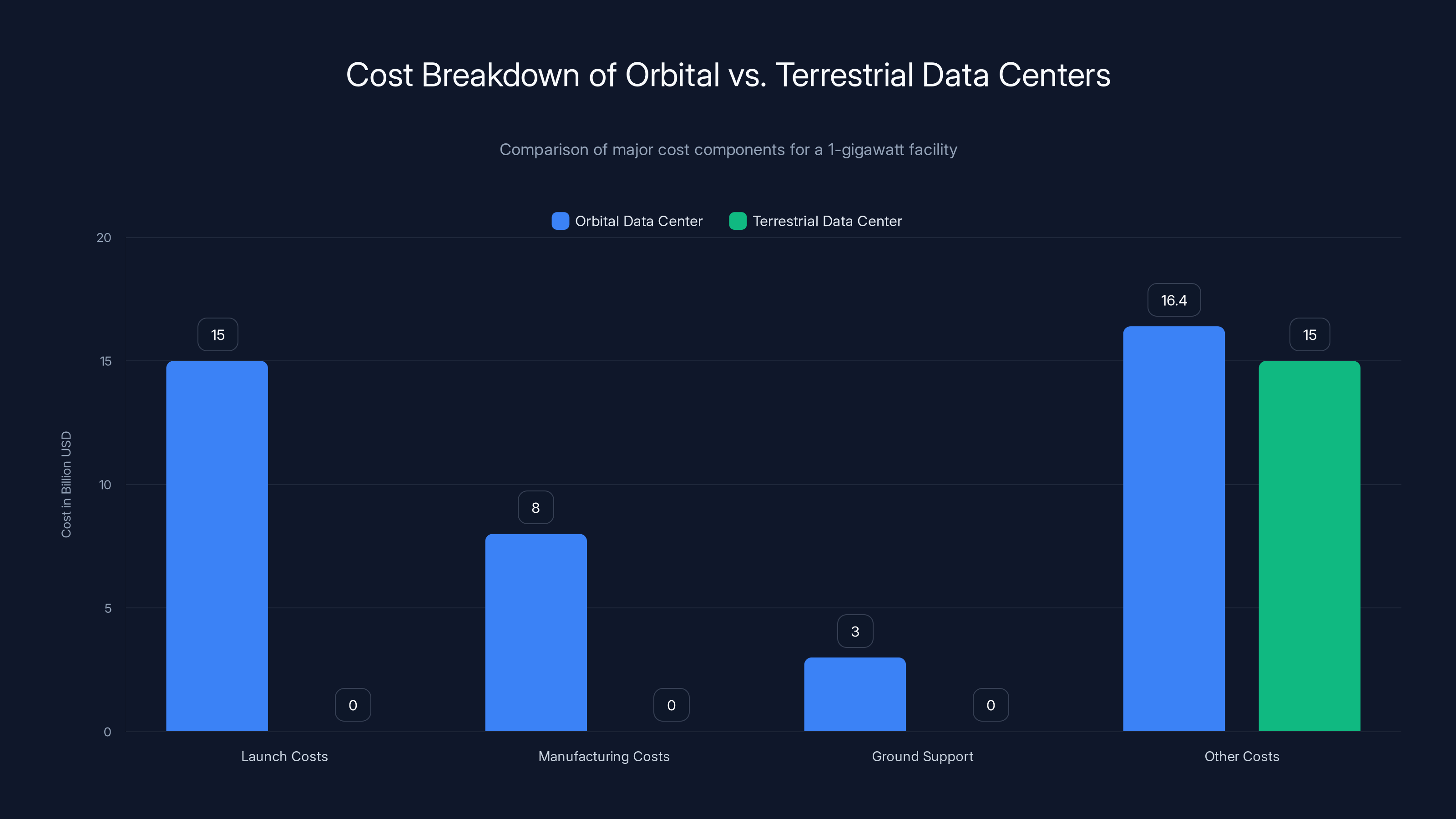

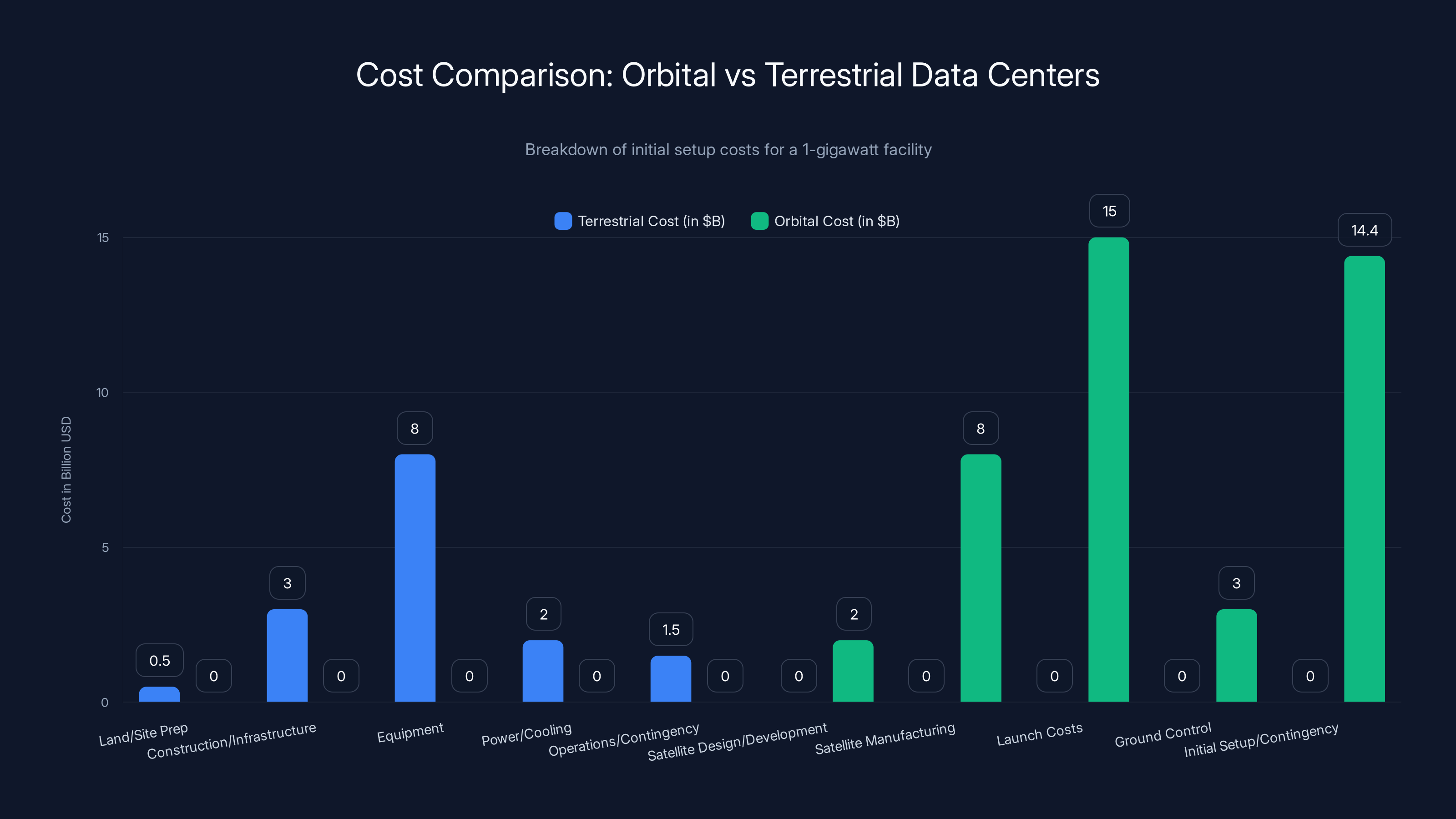

The seminal analysis comparing orbital versus terrestrial data centers considered a 1-gigawatt facility. This represents roughly the computational capacity of a large, modern hyperscale data center. The comparison yields striking results:

Terrestrial Equivalent Cost: ~$15 billion

- Land acquisition and site preparation: $500 million

- Building construction and infrastructure: $3 billion

- Computing equipment (servers, storage, networking): $8 billion

- Power infrastructure and cooling systems: $2 billion

- Operations ramp and contingency: $1.5 billion

Orbital Equivalent Cost: ~$42.4 billion

- Satellite design and development: $2 billion

- Satellite manufacturing (5,000 units): $8 billion

- Launch costs (assuming 15 billion

- Ground control infrastructure: $3 billion

- Initial operational setup and contingency: $14.4 billion

The threefold cost difference is not incidental; it reflects fundamental physical realities that cannot be easily engineered away. Launch costs alone represent 35% of total orbital expenses—entirely absent from terrestrial systems. Manufacturing costs reflect space-qualification requirements. Ground infrastructure requirements match terrestrial facilities while providing far less computational density per facility.

Operating Costs Over Time

The comparison becomes even more severe when considering multi-year operational costs. A terrestrial facility, once deployed, operates at remarkably low marginal costs: electricity, maintenance, and staffing dominate. A well-maintained data center can operate for 15+ years with declining cost per unit of computation as depreciation is amortized.

Orbital systems incur continuous replacement costs. Satellites fail or deorbit; solar panels degrade; components accumulate radiation damage. The operating cost model assumes 5-10% of the constellation requires replacement annually—meaning $5-10 billion per year in ongoing launch and manufacturing costs just to maintain constellation size and capability.

Over a 10-year operational period, the terrestrial facility might cost an additional

The initial setup cost for orbital data centers is significantly higher than terrestrial ones, mainly due to launch and satellite manufacturing expenses. Estimated data.

When Might Space Economics Improve?

Technological Breakthroughs Required

For orbital data centers to approach cost parity with terrestrial alternatives, multiple simultaneous breakthroughs are necessary:

-

Launch costs must reach $200/kg or below—an 18-fold improvement from current levels. This requires not just Starship's theoretical capabilities, but actual operational achievement at those costs for years, proven reliability, and sustained pricing.

-

Satellite manufacturing must halve in cost—moving from

500/kg through automation, scale, and supply chain optimization. This requires proven manufacturing processes and multi-year production commitments. -

Orbital operations must develop in-situ repair or rapid replacement capabilities—either robotic repair systems that function on-orbit, or launch cadences that enable satellite replacement within days rather than weeks.

-

Power and thermal management must substantially improve—developing lighter, more efficient radiators and energy storage systems that dramatically reduce payload mass requirements.

-

Computational efficiency must improve dramatically—through specialized processors optimized for space environments that extract more computation per watt and per kilogram than terrestrial systems.

Timeline Considerations

Optimistic proponents suggest these improvements could materialize within 5-10 years. Historical precedent suggests greater skepticism is warranted. The Space Shuttle was expected to reduce costs to

SpaceX itself required a decade and billions in investment to reduce launch costs from

Meanwhile, terrestrial data center costs continue improving through conventional optimization. New cooling technologies, advanced chip architectures, and automated operations reduce costs 5-15% annually. Over a decade, terrestrial unit costs might decline 50-75%, maintaining or widening the economic advantage over orbital systems.

The Role of Government Support and Subsidies

Defense and Intelligence Applications

One path to orbital data center viability involves government procurement. The U. S. Department of Defense and intelligence agencies face constraints on terrestrial data center deployment due to geographic limitations. Space-based computing could theoretically enable secure, distributed processing across global mission sets.

Government funding could accelerate development and absorb early losses. If the Pentagon subsidizes orbital data center development to the tune of $20-50 billion over a decade, commercial viability could arrive earlier. However, this represents a hidden cost—government funding ultimately derives from taxpayers and could be invested in other priorities.

Moreover, government-backed projects face different economic logic than commercial ventures. A government program might accept 50% profit margins or indefinite losses if strategic value justifies the expense. Commercial companies face investor scrutiny and must demonstrate clear paths to profitability.

International Competition and Geopolitics

The orbital AI race increasingly reflects geopolitical dimensions. China and other nations might pursue space-based computing for strategic advantages unrelated to pure economics. If China launches a 500-gigawatt orbital compute constellation for national purposes, the U. S. might feel compelled to match the capability regardless of unit economics.

This geopolitical dimension could drive deployment timelines and funding levels above what economics alone would justify. International competition might accelerate breakthroughs in launch costs and satellite manufacturing simply through coordinated investment and prioritization.

Falcon 9 has reduced launch costs significantly from its initial

Industry Sentiment and Investor Perspectives

Optimistic Narratives

Venture capital and technology industry enthusiasm for orbital AI remains high. Prominent investors have backed multiple space-AI startups. Analogies to previous technological transitions—"space computing is the cloud era's equivalent to cloud computing"—circulate in investor presentations. The narrative suggests that early movers will capture transformative value if orbital computing achieves even modest market share.

This optimism is not entirely unfounded. If orbital data centers eventually achieve cost parity with terrestrial facilities and offer advantages like redundancy, latency benefits, or security improvements, they could eventually capture significant market share. Early investors in SpaceX or Tesla benefited enormously from technologies that initially seemed economically marginal.

Skeptical Analysis

Yet skeptics point to fundamental differences between space computing and previous technology transitions. Cloud computing succeeded because it provided genuine advantages: reduced capital requirements, geographic distribution, and operational leverage that terrestrial data centers couldn't match. Orbital computing offers few advantages beyond the speculative promise of lower future costs.

Moreover, the timeline being publicly promoted—orbital AI reaching price parity by 2027-2030—appears aggressive given current technology status and historical precedent for space development delays. Missing by 5 years would mean 2032-2035, during which terrestrial data center costs continue declining, potentially perpetually widening the economic gap.

Alternative Approaches and Competing Visions

Distributed Ground-Based Computing

An alternative to orbiting data centers is distributed terrestrial computing at unprecedented scale. Instead of concentrating AI compute in expensive orbital facilities, deploying thousands of smaller data centers globally could offer similar redundancy, latency benefits, and geographic distribution. This approach uses proven technology and economics, avoiding the unproven challenges of space operations.

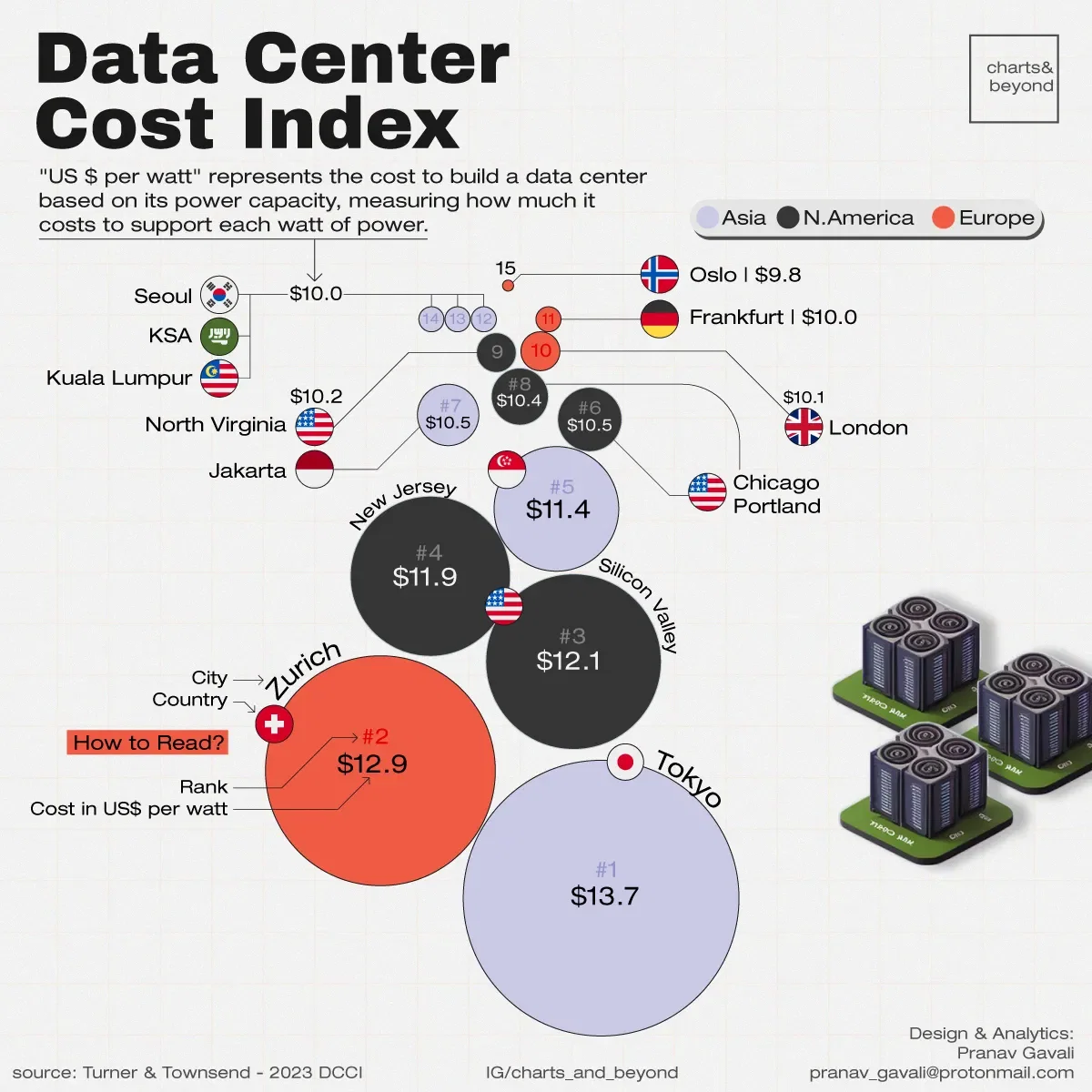

the constraint is land use and electricity availability. However, many regions with excellent natural cooling (Nordic countries, Canada) and abundant renewable energy remain underdeveloped for data center deployment. Investing in these regions might offer similar advantages to orbital systems at a fraction of the cost.

Specialized Orbital Applications

Orbital computing might eventually find economically justified niches without achieving broad parity with terrestrial systems. Earth observation processing, meteorological analysis, and some defense applications could benefit from processing data close to where satellites collect it. These specialized applications might justify orbital computing without requiring general-purpose cost parity.

Similarly, low-latency applications might accept premium pricing if orbital systems reduce latency to mere milliseconds for specific use cases. Algorithmic trading, real-time financial applications, or other latency-sensitive workloads could justify orbital deployment at higher costs than terrestrial alternatives.

Synthesizing Reality: The Likely Future

Most Probable Scenario

Based on current economics, technology status, and historical precedent, the most likely outcome is that orbital data centers develop as a niche capability rather than a transformative replacement for terrestrial infrastructure. By 2030-2035, SpaceX will likely have achieved operational Starship capability and reduced launch costs to

During this period, multiple orbital data center startups will attempt commercial operations. Some will fail; others will find profitable niches in specialized applications. A few might scale to meaningful revenue levels. By 2040, orbital computing could represent 1-5% of global data center capacity—meaningful, but not transformative.

Terrestrial data centers will continue dominating, particularly for latency-sensitive and cost-sensitive workloads. As renewable energy becomes increasingly abundant, terrestrial electricity costs may drop further, widening the economic advantage over orbital systems.

Optimistic Path

In more favorable scenarios where multiple technological breakthroughs align, orbital data centers could achieve broader adoption. If Starship costs genuinely reach

This scenario requires sustained technology improvements, massive private and public investment, and favorable regulatory outcomes. It's possible but requires multiple aligned developments beyond current technology demonstration.

Pessimistic Path

In less favorable outcomes, orbital data centers could remain economically unjustifiable throughout the 2030s and 2040s. If Starship encounters sustained delays (plausible given complex aerospace development), if in-situ capabilities prove technologically infeasible, or if terrestrial data center costs drop faster than orbital manufacturing costs, space-based computing could become a perpetual "future possibility" without mainstream deployment.

Historically, this has been the most common outcome for speculative space industries. The space tourism industry was predicted to transform travel; decades later, it remains a niche luxury service. Space manufacturing has been promoted for decades as the next frontier; meaningful space-based manufacturing remains minimal.

Implications for Businesses and Developers

Current Decision-Making

For organizations evaluating computing infrastructure today, orbital data centers should not feature in decision-making. Terrestrial options—whether cloud providers, edge computing networks, or hybrid approaches—offer proven economics, reliability, and capabilities. Betting critical workloads on orbital infrastructure would be imprudent.

However, monitoring orbital AI development remains sensible for forward-looking technology organizations. Early movers in specialized niches could potentially capture value if orbital computing does achieve breakthrough economics. Companies in defense, intelligence, space operations, or other government-supported sectors might find opportunities in orbital systems funded through government channels.

Strategic Positioning

For developers and architects, understanding orbital compute constraints informs broader infrastructure strategy. The tools and software models optimized for terrestrial data centers—based on abundant cheap electricity, low latency, and reliability—remain optimal for foreseeable timescales.

However, designing software and AI models with geographic distribution and offline processing capability creates flexibility. As orbital and edge computing options eventually mature, such designs can adapt more easily. This hedging approach acknowledges uncertainty while remaining pragmatically grounded in current reality.

For platform developers like Runable, which provide AI-powered automation and workflow tools, the implications are clear: focus remains on terrestrial infrastructure. The current market for AI automation, document generation, and workflow optimization operates entirely through ground-based compute. As orbital capabilities eventually mature in specialized niches, platform adaptation can occur then, but early focus should remain where the market exists today.

Expert Insights and Industry Perspectives

From Aerospace Engineers

Space professionals tend to be more skeptical of near-term orbital AI viability than venture capitalists. The engineering challenges—thermal management, power distribution, radiation shielding, debris avoidance—are formidable. Space engineers have learned through decades of experience that systems operating in the space environment encounter unexpected challenges and higher-than-modeled failure rates.

Their consensus suggests that orbital data centers are technically feasible but economically marginal at best for at least the next decade. The engineering possibilities don't translate to practical viability without breakthrough cost reductions or specialized applications that genuinely benefit from space-based deployment.

From Cloud Infrastructure Operators

Hyperscale cloud providers like Amazon, Google, and Microsoft express measured interest in orbital computing but have not committed substantial resources to the space. AWS executives have publicly noted that current orbital economics don't justify deployment. These companies, with unparalleled expertise in optimizing terrestrial data center economics, recognize that orbital systems struggle to compete even against their already-optimized facilities.

Their strategy appears to be monitoring developments while continuing terrestrial investment. If orbital computing eventually achieves viability, they have the resources to rapidly adopt and scale. Meanwhile, their competitive advantage remains in optimized ground-based infrastructure and software ecosystems.

From Space Entrepreneurs

Fundamentally, space entrepreneurs pushing orbital AI believe that breakthroughs are inevitable and near-term skepticism reflects conservative thinking that missed previous technology transitions. They point to how SpaceX's reusable rockets seemed impossible until they worked; how Starlink seemed uneconomical until it operated.

Yet these entrepreneurs also acknowledge the challenges. Even the most optimistic recognize that current economics don't work, that technology breakthroughs are required, and that timelines are uncertain. Their confidence reflects belief in eventual breakthrough, not belief that current economics are sound.

Conclusion: Separating Vision from Economics

The Fundamental Reality

Orbital AI data centers represent a genuinely interesting technological vision with legitimate long-term potential. The physics of orbital infrastructure is well understood; the engineering challenges, while severe, are solvable through sufficient investment and time. It's theoretically possible that space-based computing could eventually offer advantages over terrestrial systems.

However, "theoretically possible over a 20-year horizon" is fundamentally different from "economically viable in the next 3-5 years" or "transformative by 2028." The brutal mathematics of orbital economics—the

Breakthrough improvements in launch costs remain speculative. Manufacturing cost reductions depend on volume commitments that themselves depend on economic viability—a chicken-and-egg problem. Operating costs remain troubling when satellites degrade, deorbit, and require replacement. Thermal and power challenges introduce engineering margins that terrestrial systems never face.

Separating Hype from Reality

The orbital AI narrative has become increasingly divorced from economic reality. When entrepreneurs and investors speak of massive cost reductions arriving within 36 months, they're extrapolating from theoretical engineering models without accounting for the numerous uncertainties, delays, and unexpected challenges that historically characterize space development.

This doesn't mean these individuals are dishonest or delusional. Rather, they're engaging in the standard practice of technology entrepreneurship: advancing a vision, securing investment, and maintaining momentum despite uncertain outcomes. History is filled with technologies that seemed promising but never achieved their projected economics. It's also filled with technologies that overcame obstacles and achieved transformation.

Orbital AI could fall into either category. The outcome depends on technological breakthroughs not yet demonstrated, sustained investment over many years, and favorable market conditions that terrestrial alternatives don't eliminate through continued optimization.

Making Informed Decisions

For individuals and organizations making decisions today, the appropriate stance is cautious skepticism combined with strategic monitoring. Orbital computing is unlikely to disrupt terrestrial data centers significantly before 2040, if ever. This should inform infrastructure investment and technology adoption decisions.

Yet maintaining awareness of orbital developments remains prudent. If breakthroughs do occur, early awareness enables rapid adaptation. The responsible approach combines realistic assessment of current economics with openness to future possibilities.

The entrepreneurs, investors, and engineers working on orbital AI deserve respect for their ambition and technical depth. The economic analyses suggesting viability deserve serious consideration. But respecting the vision doesn't require accepting that current timelines and cost projections are reliable. History suggests greater caution is warranted.

Orbital AI may eventually transform computing. But probably not in the timeframes being publicly promoted, and probably not through the economics that current analyses project. The vision is genuinely compelling; the path to realization remains genuinely brutal.

FAQ

What makes orbital data centers so expensive?

Orbital data centers face three major cost drivers: launch costs (

How does the cost of launching satellites affect overall orbital data center economics?

Launch costs represent roughly 35% of total orbital data center expenses at current pricing of

What is the thermal management challenge in orbital data centers?

Unlike terrestrial data centers that dissipate heat through air and water cooling, orbital systems must rely on radiative cooling in vacuum. Satellites must reject 200-300 megawatts of waste heat using radiator panels covering hundreds of square meters, operating at elevated temperatures (80-100°C). This requires exotic materials, sophisticated heat management systems, and adds substantial mass and cost. Additionally, orbital systems experience dramatic thermal cycling—100°C+ swings every 90 minutes—causing stress and component fatigue that terrestrial systems never encounter.

Can solar power make orbital data centers economically viable?

Orbital solar offers advantages—unobstructed sunlight, high panel efficiency (30-35% in space vs. 15-20% terrestrially)—but carries significant disadvantages. Satellites enter Earth's shadow every 45 minutes, requiring either massive battery storage (adding billions in cost), redundant power systems (exponentially increasing satellite count), or accepting operational interruptions. Degradation from radiation and micrometeorite impacts means panels lose 20-30% efficiency over a 10-15 year operational lifespan, requiring continual replacement and maintenance.

What is the most significant obstacle preventing orbital AI data centers from launching at scale?

The fundamental obstacle is economics: even with optimistic assumptions about technological improvements, orbital data centers remain 2-3 times more expensive than terrestrial alternatives. While engineering challenges are severe, they're ultimately solvable with sufficient resources. The economic equation is harder to solve because it depends on simultaneous breakthroughs in launch costs, manufacturing efficiency, satellite reliability, and operational procedures—any one of which could take a decade to achieve. Terrestrial data center costs continue improving through conventional optimization, making the target an even-moving one that orbital systems struggle to catch.

How long until orbital data centers become cost-competitive with ground-based facilities?

Optimistic scenarios suggest cost parity could arrive by 2035-2040 if multiple technological breakthroughs align successfully. Realistic assessments suggest 2040-2050 or potentially never, depending on whether fundamental economics can be overcome. The timeline depends on Starship achieving operational maturity and maintaining $500-1,000 per kilogram launch costs, satellite manufacturing costs falling 50%, and numerous other breakthroughs proving successful simultaneously—all assumptions with substantial uncertainty based on historical precedent with space technology development.

Could orbital data centers find profitable niches even without general cost parity?

Absolutely. Specialized applications could justify orbital computing even at premium costs: Earth observation processing (analyzing satellite data close to collection point), real-time defense applications, low-latency financial trading, and government intelligence operations could all justify orbital deployment in specific niches. However, these niche applications would likely represent 1-5% of global data center capacity even if widely pursued, not the transformative replacement some proponents suggest.

What role would governments play in making orbital AI viable?

Government support through defense and intelligence procurement could substantially accelerate orbital data center viability by funding early losses and accepting lower return-on-investment thresholds than commercial investors require. The U. S. Department of Defense, intelligence agencies, and other governments might pursue orbital computing for strategic advantages unrelated to pure economics. However, government funding ultimately derives from taxpayers and represents opportunity costs—investment in orbital systems means less investment in other priorities, making this path economically questionable at a societal level.

How do operational costs for orbital data centers compare to terrestrial facilities over time?

Terrestrial data centers operate for 15+ years with relatively stable costs (electricity, maintenance, staffing). Orbital systems face continuous replacement costs as satellites fail or deorbit—statistically, 5-10% of a constellation annually requires replacement, translating to

What alternatives exist to orbital data centers for addressing AI compute demands?

Several alternatives can address growth in AI compute demands: distributed terrestrial data centers in regions with abundant renewable energy (Nordic countries, Canada), specialized edge computing closer to data sources, and development of more efficient AI algorithms and architectures reducing compute requirements. For developers and teams needing AI-powered automation capabilities, platforms like Runable offer cost-effective AI-driven solutions ($9/month) for document generation, workflow automation, and content creation without requiring any space-based infrastructure.

Key Takeaways

- Orbital data centers cost 3x more than terrestrial equivalents (15B) due to launch costs, manufacturing, and space-specific engineering

- Launch costs must fall from 200/kg (18-fold improvement) for economic viability—Starship is theoretical, not proven operational

- Satellite manufacturing costs of $1,000/kg must fall 50% through mass production, creating circular dependency: need volume commitment before proving viability

- Thermal management in vacuum through radiative cooling requires massive radiator panels, complex systems, and limits operational lifespan through thermal cycling

- Operational costs perpetually degrade economic model through satellite replacement (5-10% annually), deorbiting from atmospheric drag, and radiation-induced degradation

- Intermittency of solar power in orbit requires massive battery storage or deployment redundancy, both adding billions to constellation costs

- Reliability challenges including orbital debris collisions and single points of failure require substantial redundancy multipliers that increase total constellation costs

- Terrestrial data center costs continue improving through conventional optimization, making orbital systems chase a moving target that may never be caught

- Most probable scenario: orbital AI becomes niche capability for specialized applications by 2035-2045, not transformative replacement for terrestrial infrastructure

- Current promotional timelines (2027-2030 viability) appear aggressive given technology status and historical precedent for space development delays; 2040-2050 more realistic

Related Articles

- Nvidia's $2B CoreWeave Bet: Vera Rubin CPUs & AI Factories Explained [2025]

- xAI's Lunar Manufacturing Plans: Musk's Moon Strategy Amid IPO & Leadership Exodus

- Microsoft's $37.5B AI Bet: Why Only 3.3% Actually Pay for Copilot [2025]

- Z-Angle Memory: Intel & SoftBank's HBM Challenge Explained [2025]

- How AI and Nvidia GB10 Hardware Could Eliminate Reporting Roles [2025]

- Intel GPU Development 2025: Strategic Hiring & Nvidia Challenge