Poland's Energy Grid Came Under Attack From Never-Before-Seen Wiper Malware

Poland's electricity infrastructure faced one of the most dangerous cyberattacks in European history when Russian state-aligned hackers unleashed a custom-built wiper malware in late December 2025. The destructive payload, dubbed Dyno Wiper, represented a serious escalation in cyberwarfare tactics targeting critical infrastructure. But here's where it gets interesting: the attack failed. No blackouts. No disrupted power delivery. No electricity cut to millions of people.

That might sound like good news on the surface, but the reality is far more complicated. Researchers have been asking why such a sophisticated attack failed, and the answers reveal uncomfortable truths about the state of critical infrastructure security, the evolving nature of state-sponsored cyberattacks, and what comes next.

The timing wasn't random either. The attack occurred on the 10th anniversary of Russia's devastating 2015 cyberattack on Ukraine's power grid—an attack that left roughly 230,000 people without electricity for six hours during the coldest time of year. That wasn't just a hack. That was the first confirmed use of malware to cause a physical blackout. It changed everything about how countries think about energy security.

What happened in Poland reveals something crucial about modern cyberwarfare: Russia isn't just trying to knock out power anymore. The strategy has evolved. The deployment of a wiper means something different now. It's about sending messages, testing defenses, and keeping adversaries off-balance. It's about demonstrating capability without (maybe) using all of it.

Let's walk through what happened, why it matters, and what it tells us about the future of energy security in Europe and beyond.

TL; DR

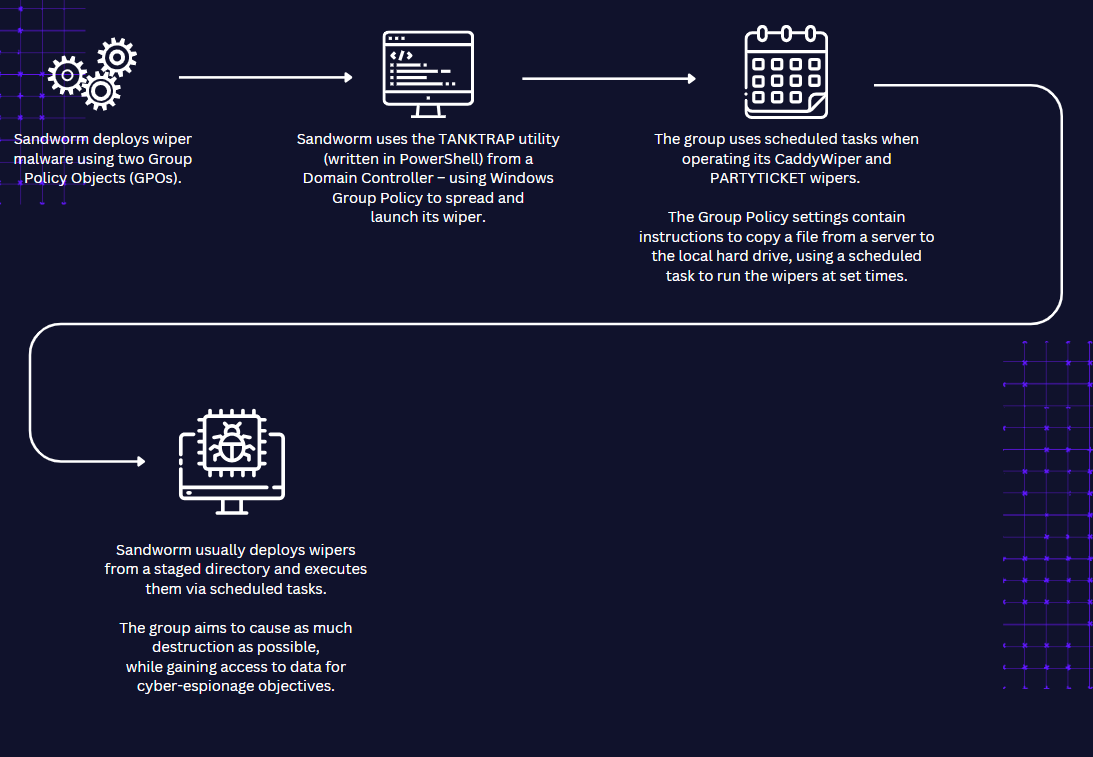

- The Attack: Russian-aligned Sandworm deployed custom Dyno Wiper malware against Poland's energy grid in late December 2025, targeting communications between renewable installations and power distribution operators

- Why It Failed: Reasons remain unclear, but likely included strong cyber defenses, successful detection and containment, or intentional restraint by Russia to send a message without full escalation

- Historical Context: The attack occurred on the 10th anniversary of Russia's 2015 Ukraine power grid attack that knocked out 230,000 customers for six hours

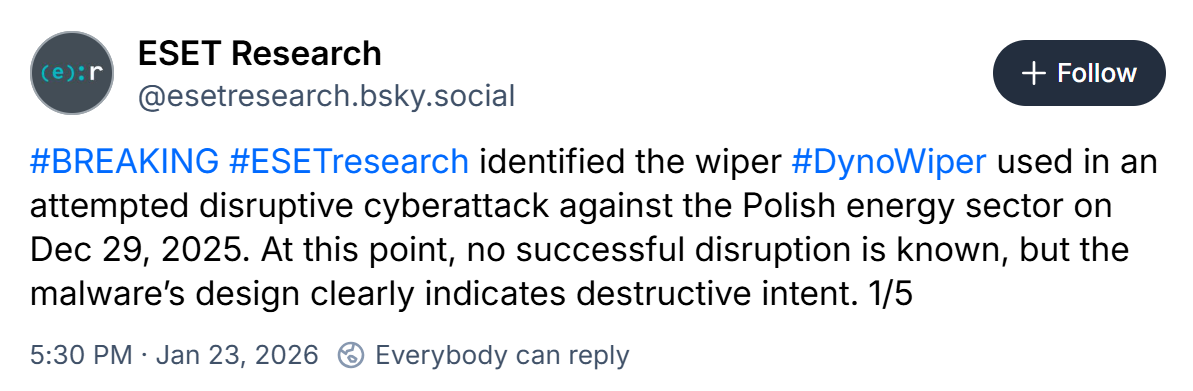

- Attribution: Security firm ESET attributed the attack to Sandworm with medium confidence based on malware tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) that overlap with previous Sandworm activity

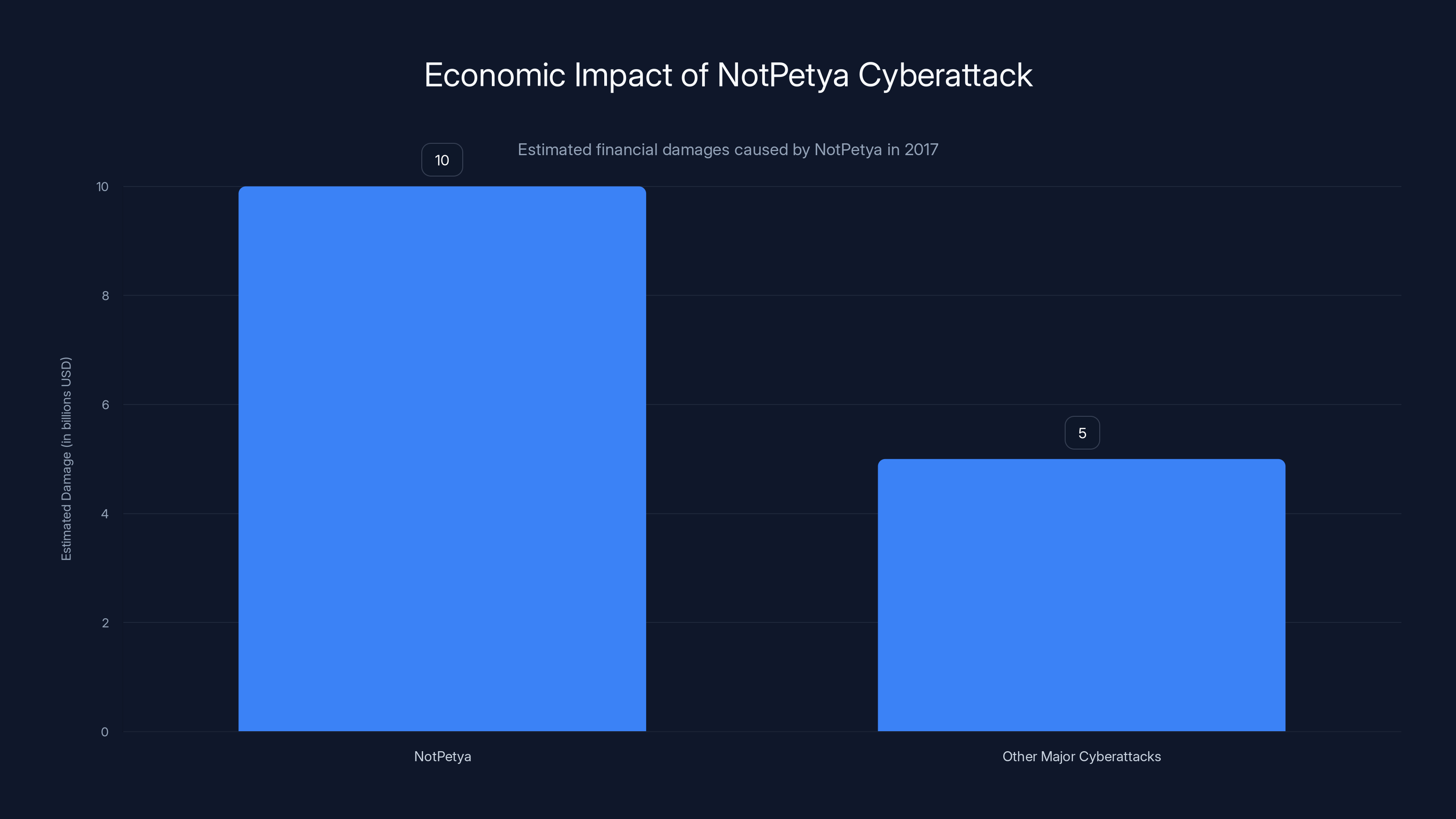

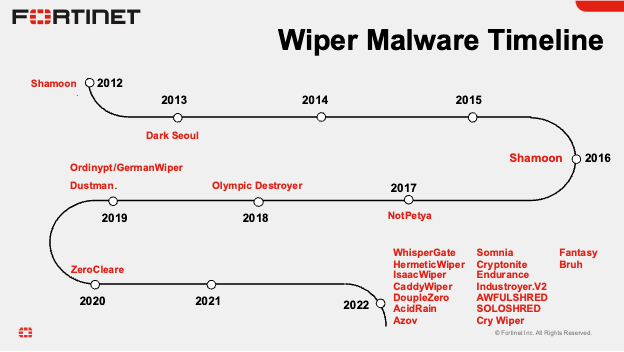

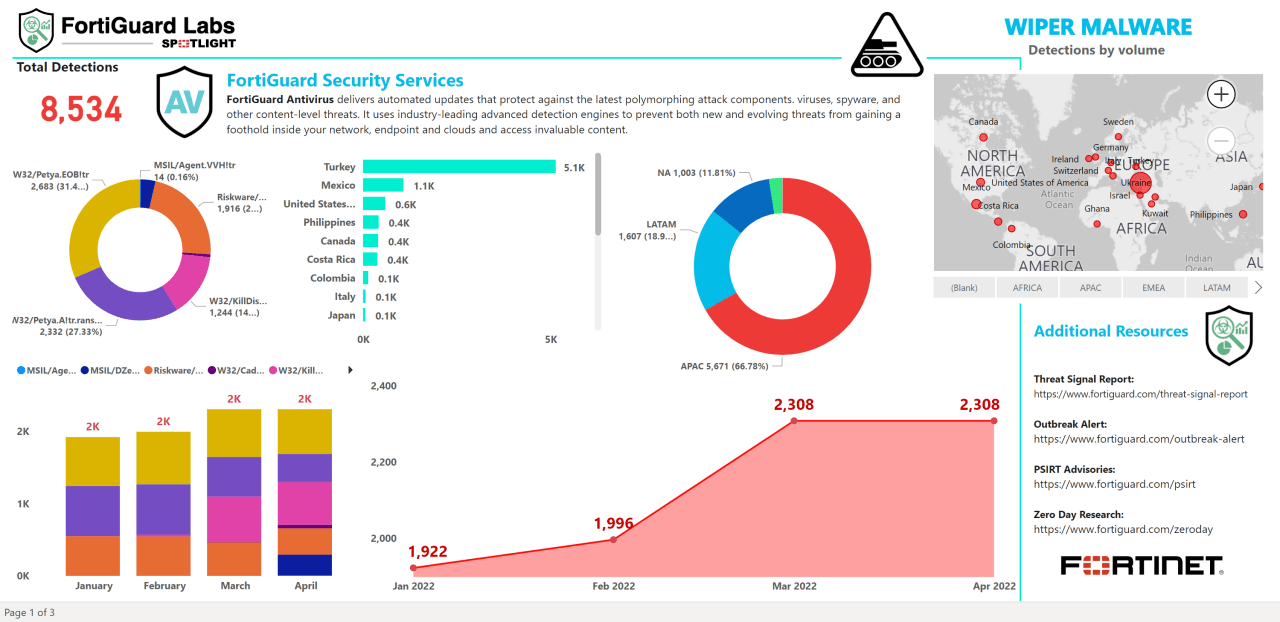

- Broader Pattern: This represents the latest in a series of destructive wipers Russia has deployed, including Not Petya ($10 billion damage in 2017) and Acid Rain (disabled 270,000 satellite modems in 2022)

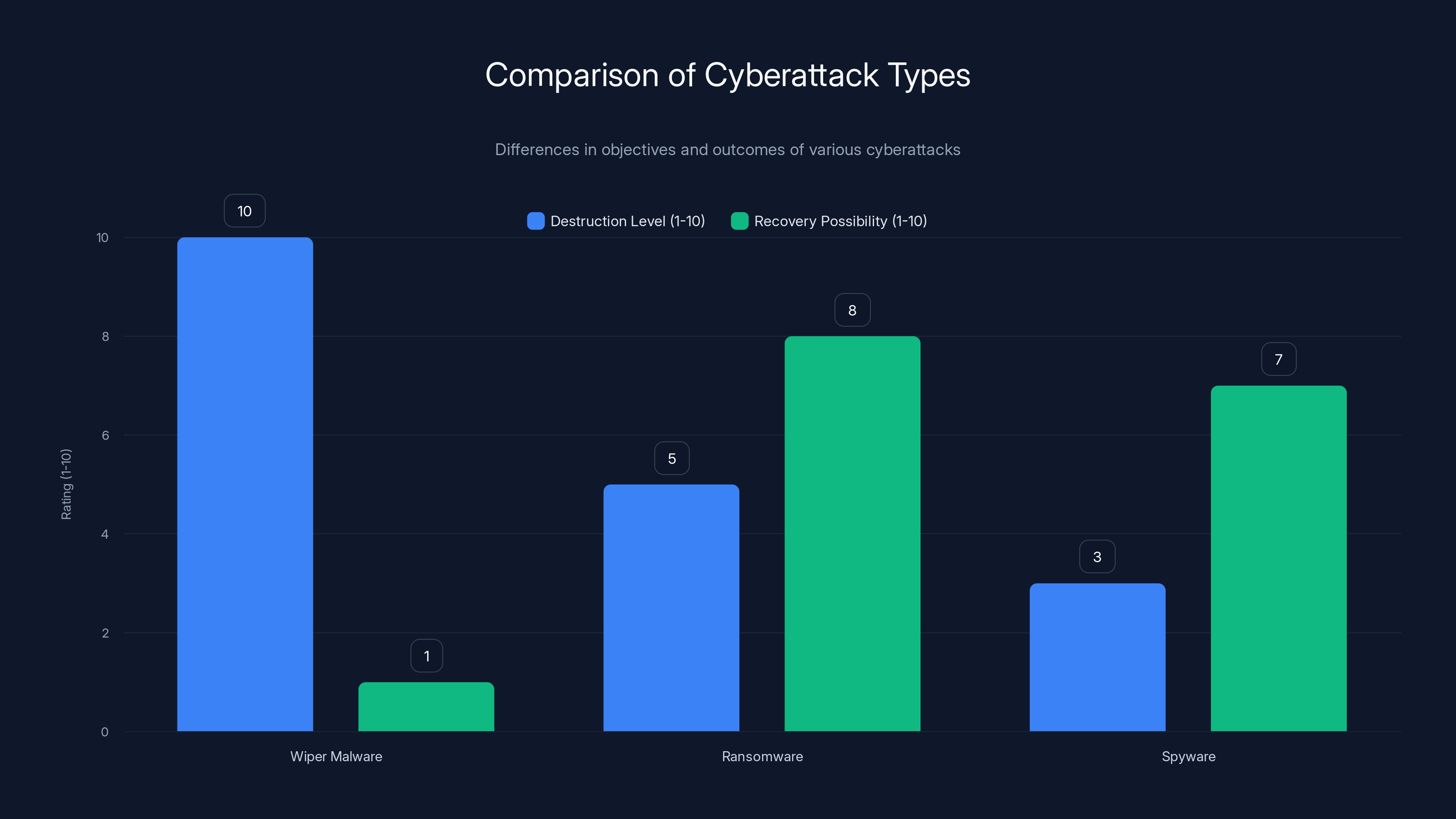

Wiper malware is the most destructive with no recovery options, unlike ransomware and spyware which allow some form of data recovery.

Understanding Wiper Malware: The Weapon That Destroys Everything

Wiper malware is fundamentally different from most cyberattacks you've heard about. It's not trying to steal your data. It's not looking for ransom opportunities. It's not establishing a backdoor for long-term access. A wiper exists for one purpose: complete destruction.

When wiper malware executes on a target system, it systematically erases everything. It overwrites files. It corrupts databases. It destroys boot sectors. It renders systems completely unusable. The goal isn't espionage or financial gain—it's operational destruction. It's economic sabotage wrapped in malicious code.

Think of the difference this way. Traditional malware wants to stay hidden and productive. Ransomware wants to extort money from you. Spyware wants to watch what you do. Wiper malware wants to burn everything down and leave nothing but wreckage. Once it finishes its work, it typically deletes itself, leaving investigators with minimal forensic evidence about what actually happened.

The reason wipers are so dangerous in critical infrastructure contexts is that they're designed for maximum disruption with minimal recovery time. A power company hit by ransomware can negotiate with attackers, pay a ransom, and decrypt their systems. A company hit by a wiper has no such option. Their data is gone. Their systems are destroyed. Recovery means rebuilding from complete backups, reimaging servers, and praying you kept those backups somewhere completely separate from your networked systems.

In the context of energy grids specifically, a successful wiper attack doesn't just cause a blackout. It causes a sustained blackout because it takes time to restore systems from backups. During that restoration period, tens of millions of people lose access to electricity. Hospitals switch to backup power. Traffic lights go dark. Water treatment facilities go offline. The cascading effects ripple through society faster than anyone expects.

What makes Dyno Wiper particularly concerning isn't just its destructive capability—it's that it was custom-built for this specific attack. Unlike off-the-shelf malware, custom wipers are engineered specifically to target the unique architecture of their intended victim. They're tailored to bypass specific defenses, interact with particular systems, and achieve maximum effect with minimal detection. This level of customization requires significant resources, institutional knowledge, and technical sophistication. It's not something independent cybercriminals do. It's what nation-states do.

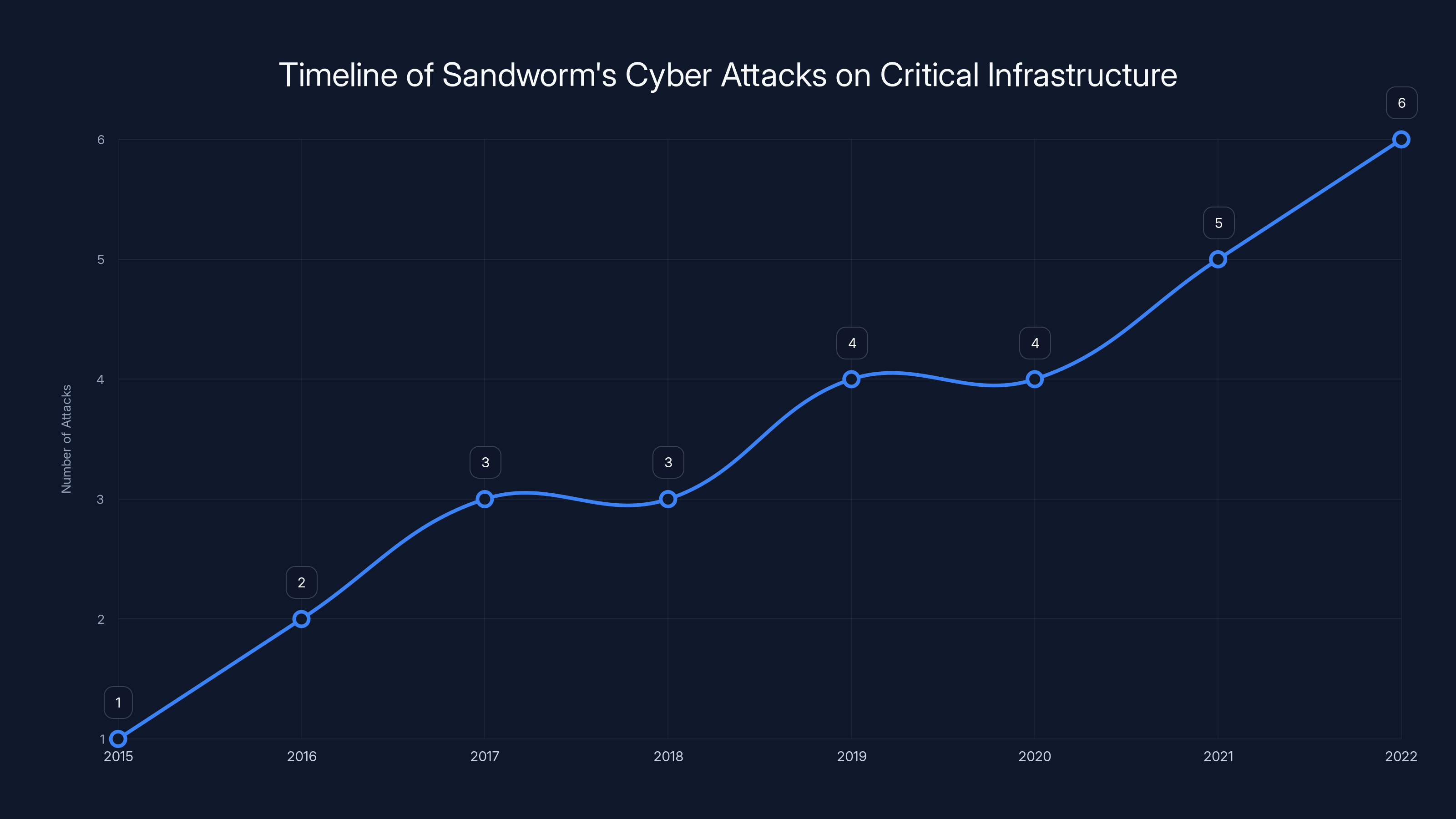

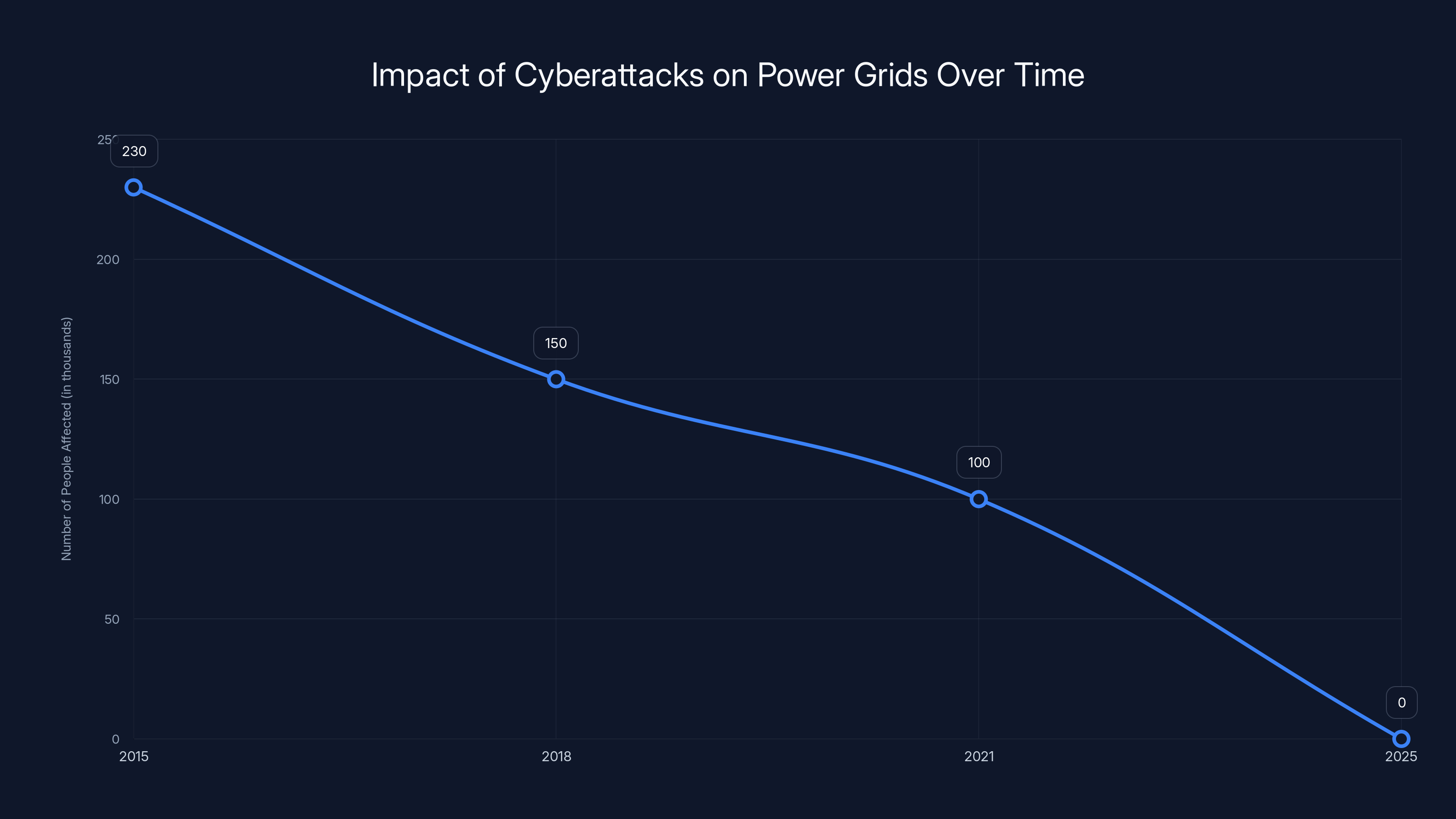

The line chart illustrates the increasing frequency of Sandworm's cyber attacks on critical infrastructure from 2015 to 2022, highlighting their evolving threat. Estimated data.

Sandworm: A Decade of Destructive Attacks on Critical Infrastructure

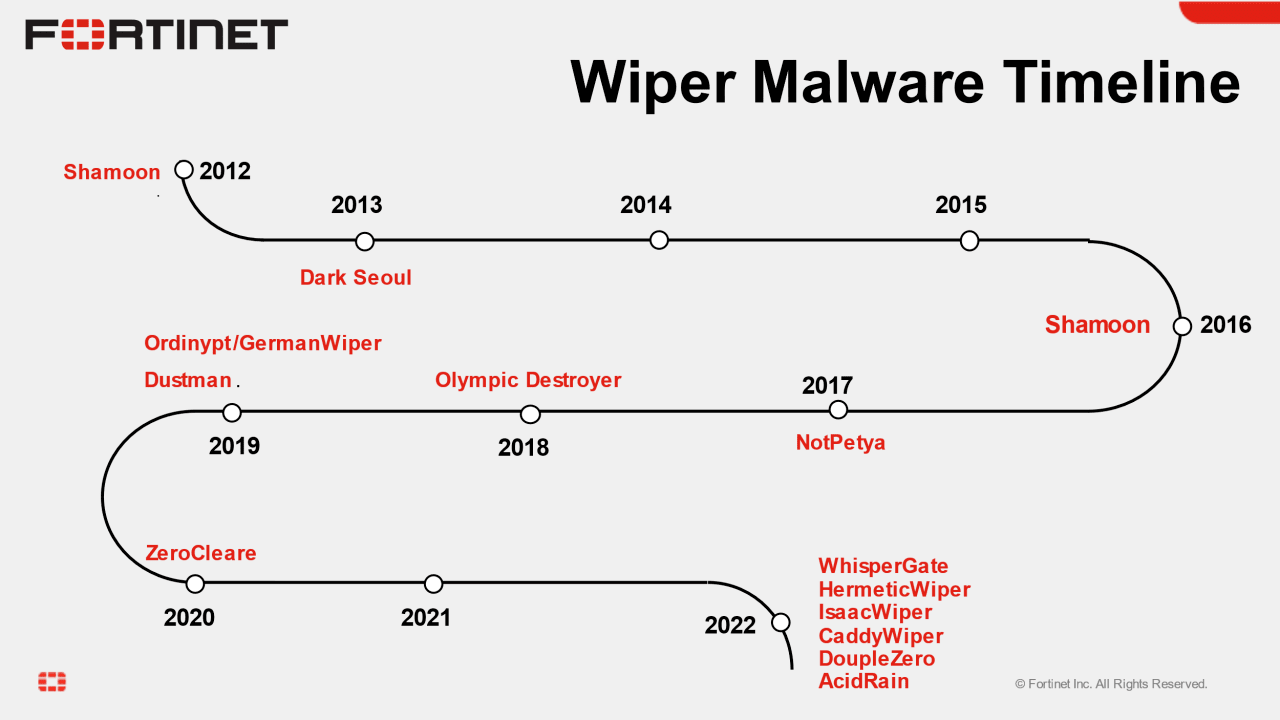

Sandworm, the group attributed to this attack by security firm ESET, isn't a new player in the cyberwarfare landscape. This is one of Russia's most sophisticated and destructive state-sponsored hacking groups, and they've been waging cyberwarfare campaigns for over a decade.

Sandworm's reputation was built on one incident: December 2015. That's when they used Black Energy malware to penetrate the systems of three Ukrainian power distribution companies. They didn't just steal data. They didn't just cause technical problems. They seized direct control of the systems that distribute electricity to customers, and they turned that distribution off. For about six hours in the middle of winter, roughly 230,000 people in Ukraine sat in the dark. Some of them were elderly. Some were sick. It was the first confirmed instance of malware causing a real-world power outage.

That attack changed everything. Before December 2015, critical infrastructure operators mostly thought cyberattacks were theoretical threats. After that attack, they became real. The incident forced every power company in the developed world to take cyberdefense seriously.

But Sandworm didn't stop. They evolved. Over the next decade, they deployed wiper after wiper after wiper. Each one more sophisticated. Each one targeting different critical infrastructure. Universities in Ukraine. Government networks. Telecommunications systems. Power facilities. They've been relentless.

In 2022, during the first weeks of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, Sandworm deployed a wiper called Acid Rain. This one wasn't targeting power systems. It was targeting satellite internet modems. Think about that for a moment. They knocked out 270,000 satellite modems in a coordinated attack designed to disrupt communications during the invasion. That's not defensive hacking. That's preparing the battlefield.

Then came 2023 and beyond. ESET documented multiple Sandworm wiper campaigns targeting Ukrainian universities, critical infrastructure facilities, and government networks. Each campaign was more refined. Each one incorporated better stealth mechanisms. Each one demonstrated deeper understanding of target networks.

The consistency is striking. The group has developed a recognizable playbook: reconnaissance and network mapping, credential harvesting, lateral movement through the target network, and finally, deployment of custom-built wiper malware tailored to that specific environment. It's methodical. It's effective. It works.

When ESET attributed the Poland attack to Sandworm, they weren't just guessing. They analyzed the malware code, examined the tactics used to deploy it, and looked at the techniques for navigating the target network. All of those matched established Sandworm patterns. The "medium confidence" attribution label in security research means they're pretty sure, but they're hedging because attribution is inherently difficult. There's no DNA test for malware.

The December 2025 Attack: Timeline and Technical Details

The attack targeting Poland's energy grid occurred during the last week of December 2025. Exact dates remain somewhat unclear because initial reporting came through Reuters and other news outlets rather than direct government disclosure. But the window was definitely late December, placing it uncomfortably close to the 10th anniversary of the December 2015 Ukraine attack.

According to available reporting, the attack specifically targeted communications infrastructure between renewable energy installations and the central power distribution operators. This is a crucial detail because modern power grids in Europe rely increasingly on distributed renewable sources. Centralized coal and nuclear plants are being phased out. Solar arrays, wind farms, and biomass facilities are scattered across countries. Coordinating all that distributed generation requires sophisticated communications networks.

Those communications networks are often separate from the control networks that manage power distribution to customers. That separation exists specifically to reduce security risk. If attackers break into the communications layer, the thinking goes, they can't immediately reach the distribution control systems. But coordinated disruption of both layers simultaneously could cause severe problems.

The attack appears to have targeted that communications layer. The malware was deployed against systems managing renewable installation data flows. If the wiper had successfully destroyed those systems, power operators would lose visibility into how much renewable power was being generated across the grid. They'd lose ability to coordinate distributed generation in real time. They'd have to shift load to traditional generation sources. The grid would become unstable.

But it didn't play out that way. The malware either didn't spread as intended, or it was detected and contained before it could cause damage. The communications remained intact. The grid stayed stable. No blackout occurred.

ESET's analysis found that the malware used was indeed a custom wiper, never seen in the wild before. They dubbed it Dyno Wiper. That name suggests its behavior, likely related to dynamic processes or dynamic data. The exact technical details of how Dyno Wiper worked remain under wraps, because security researchers typically don't publish complete technical details about zero-day exploits. Full disclosure happens eventually, but not immediately.

What we do know is that Dyno Wiper was designed to work within the specific environment of Polish energy infrastructure. It likely exploited vulnerabilities known only to Russian intelligence services (zero-days in security terminology). It was probably delivered through spear-phishing emails to trusted personnel at energy companies, or possibly through supply chain compromises in software or hardware used by those companies.

The exact delivery mechanism hasn't been disclosed, and may never be. What matters more is that it got in. It reached systems where it could cause damage. And then it failed.

NotPetya caused an estimated $10 billion in damages, making it one of the most costly cyberattacks in history. Estimated data.

Why Did the Attack Fail? The Unanswered Question

Here's the problem: nobody really knows why Dyno Wiper failed to achieve its objectives. ESET researchers explicitly stated they found no evidence of successful disruption. The malware either didn't work as intended, or something stopped it before it could work.

There are several possibilities, none of them reassuring.

The first possibility is that Poland's cyber defenses actually worked. Maybe incident response teams detected the attack in progress. Maybe they isolated affected systems before the wiper could spread. Maybe they had monitoring that caught unusual behavior and triggered automated responses. This would be the most comforting explanation because it would suggest that investments in cybersecurity actually paid off.

But here's the uncomfortable part: we don't know. Polish government officials have been mostly silent about details. They've acknowledged the attack occurred, but haven't explained their defensive response. That silence could mean they're still investigating. It could mean they're keeping operational details classified. Or it could mean they got lucky.

The second possibility is more troubling: maybe Russia intentionally didn't fully activate the attack. Maybe they sent Dyno Wiper not to destroy the grid, but to prove they could. Maybe this was a demonstration. A signal. A way of saying "we could do this, and we're not stopping, so you should be very nervous."

This possibility makes some sense in the geopolitical context. Russia has learned that actually destroying critical infrastructure in NATO countries carries enormous risk. It could trigger Article 5. It could provoke NATO military response. Cyberattacks exist in a gray zone where attribution takes time and response is ambiguous. But actual sustained blackouts? That's harder to explain away. That demands a response.

Sending a wiper that gets detected and fails might be the perfect attack from a geopolitical perspective. It demonstrates capability. It proves you can get inside their most protected systems. It shows you're still a threat. But it stops short of crossing the line into direct armed conflict.

The third possibility is that something in the malware itself didn't work as expected. Maybe a zero-day exploit failed for reasons the developers didn't anticipate. Maybe the custom wiper had a bug. Maybe defensive systems operated slightly differently than Sandworm expected, and that difference prevented execution. In complex software, tiny differences can cascade into complete failure.

None of these explanations are satisfying because each one points to a vulnerability we'd rather not acknowledge: either our defenses are fragile and we got lucky, or we've been deliberately probed by an enemy, or the malware itself was imperfect. None of those options are good.

What we do know is that failed attacks often teach the attackers as much as successful attacks teach defenders. Russia now knows more about Polish energy infrastructure defenses than they did before. They know where detection occurred. They know what they got wrong. They'll iterate. The next attack will be different. Better. More refined.

Not Petya: The Cautionary Tale About Wipers Getting Out of Control

The Dyno Wiper attack against Poland happened in the shadow of a much larger historical incident: Not Petya. That 2017 attack is the elephant in the room whenever security researchers discuss destructive malware. It's the cautionary tale that explains why everyone is so nervous about wiper attacks.

Not Petya was released in June 2017, and it was originally intended to target Ukraine. The creators designed it to spread through a supply chain compromise in accounting software widely used by Ukrainian companies. When those companies updated their accounting software, they unknowingly deployed malware onto their systems.

But something went wrong. Or maybe something went right, depending on your perspective. Not Petya didn't stay in Ukraine. It escaped. It infected computers around the world. It spread through corporate networks and took down systems in logistics companies, shipping firms, advertising agencies, and major corporations globally.

Within days, Not Petya had infected hundreds of thousands of computers. Within weeks, security researchers estimated the damage at $10 billion. That makes it potentially the most expensive cyberattack in history. A single piece of malware, released with the intention of targeting one country, caused more economic damage than most traditional terrorist attacks.

The Not Petya incident is crucial context for understanding why Dyno Wiper matters. It proved that wiper malware can escape its intended target. It proved that cyberweapons don't stay confined to their intended battlefield. It proved that launching destructive malware against one country can have global consequences.

That knowledge has presumably influenced how Russian state hackers think about deploying wipers against Poland or other NATO countries. Do they risk another Not Petya scenario? Do they risk malware escaping Poland and spreading to Germany, or the UK, or beyond? That escalation risk is real, and it probably influences decision-making about how aggressive to be.

But it also means Russia has learned to be more careful. Not Petya was sledgehammer tactics. Dyno Wiper appears to be more surgical. Targeted more carefully. Designed to work within a specific network. Less likely to escape and spread globally.

Medium confidence in cyberattack attribution is relatively high compared to other levels, highlighting the inherent uncertainty in identifying attackers. Estimated data.

The Broader Context: A Decade of Escalating Cyberwarfare

The Poland attack didn't happen in isolation. It's part of a pattern. Over the past decade, and especially since Russia's invasion of Ukraine in 2022, state-sponsored cyberattacks against critical infrastructure have accelerated dramatically.

Poland itself has been a target repeatedly. Ukrainian cyberattackers have hit Polish infrastructure (usually in retaliation or as part of coordinated operations). But this attack was different. This was Russian state apparatus. This was deliberate. This was sophisticated.

Before the Poland attack, the most recent major wiper campaign targeting critical infrastructure came in early 2022, when Russia deployed Acid Rain against satellite internet modems in Ukraine. That attack was part of the hybrid warfare strategy accompanying the invasion. Knock out communications. Disrupt coordination. Make the enemy's logistics harder.

But that was Ukraine. Ukraine is actively at war. Ukraine expects attacks. Poland, by contrast, is a NATO member. It's a stable democracy. It's not at war. The deployment of destructive malware against Polish critical infrastructure is a different category of escalation.

It signals that the rules have changed. It signals that critical infrastructure in NATO countries is fair game for cyberattacks. It signals that Russia is willing to take risks that it previously avoided.

Since the Poland attack, there have been whispers of other incidents. Other attempted attacks against energy infrastructure. Other reconnaissance operations. The full picture remains classified, but security researchers have hints from threat intelligence sharing and incident response consultants who work with energy companies.

The pattern is clear: Russia is testing NATO's defenses. They're probing energy grids. They're mapping critical infrastructure. They're developing attacks. Some fail. Some get detected. Some work. And everyone involved knows this is building toward something.

Critical Infrastructure Security: How Vulnerable Are We Really?

The Poland attack raises hard questions about the state of critical infrastructure cybersecurity, not just in Poland, but across Europe and North America.

On paper, critical infrastructure in developed countries should be well-defended. Power companies employ security teams. Governments invest in defensive capabilities. NATO has cyber commands. There are regulations requiring certain security practices. There's money. There's expertise. There's awareness.

And yet, sophisticated state-backed attackers still get in. They still reach systems where they can cause damage. They still deploy malware designed to destroy everything. The defenses might slow them down. The defenses might detect them eventually. But the defenses don't stop them from trying, and that matters.

Part of the problem is that critical infrastructure systems were built in a different era. Power grid control systems date back decades. Some of them run software from the 1980s. They were designed in an environment where the biggest security threat was disgruntled employees, not nation-state actors with unlimited budgets.

Modernizing that infrastructure is expensive and risky. You can't just shut down a power plant to update its control systems. You have to do it carefully, testing every change, maintaining redundancy. It takes years. It costs billions. Many utilities are in the middle of that modernization. Some haven't started.

The other problem is that cyber defense is fundamentally reactive. Attackers only need to find one vulnerability. Defenders need to find and fix all of them. It's an asymmetric game. Attackers can be patient and try over and over. Defenders have to be right every single time.

Add to that the fact that state-sponsored attackers have resources that dwarf what most critical infrastructure companies spend on security, and you get a situation where the attackers are fundamentally ahead of the defenders.

Poland's response to the attack reveals some of this challenge. They had cyber defenses. Presumably pretty good ones. And Sandworm still got in. Sandworm still deployed malware. The difference between the Poland attack being a successful blackout versus a failed attack might have come down to luck, or to detection by minutes, or to some defensive measure they'd implemented just recently.

That's not a sustainable security posture. You can't rely on luck. You can't hope attackers make mistakes. You can't assume that today's defenses will hold against tomorrow's attacks.

What you can do is invest in redundancy. Keep backups separate from live systems. Invest in incident response capabilities. Train staff. Implement monitoring that catches unusual behavior. Segment networks so that a compromise in one area doesn't immediately cascade through the entire infrastructure. Test regularly. Plan for failure.

Poland presumably has some of these measures in place. The fact that Dyno Wiper failed suggests at least some defensive capability worked. But the full extent of that capability remains unknown.

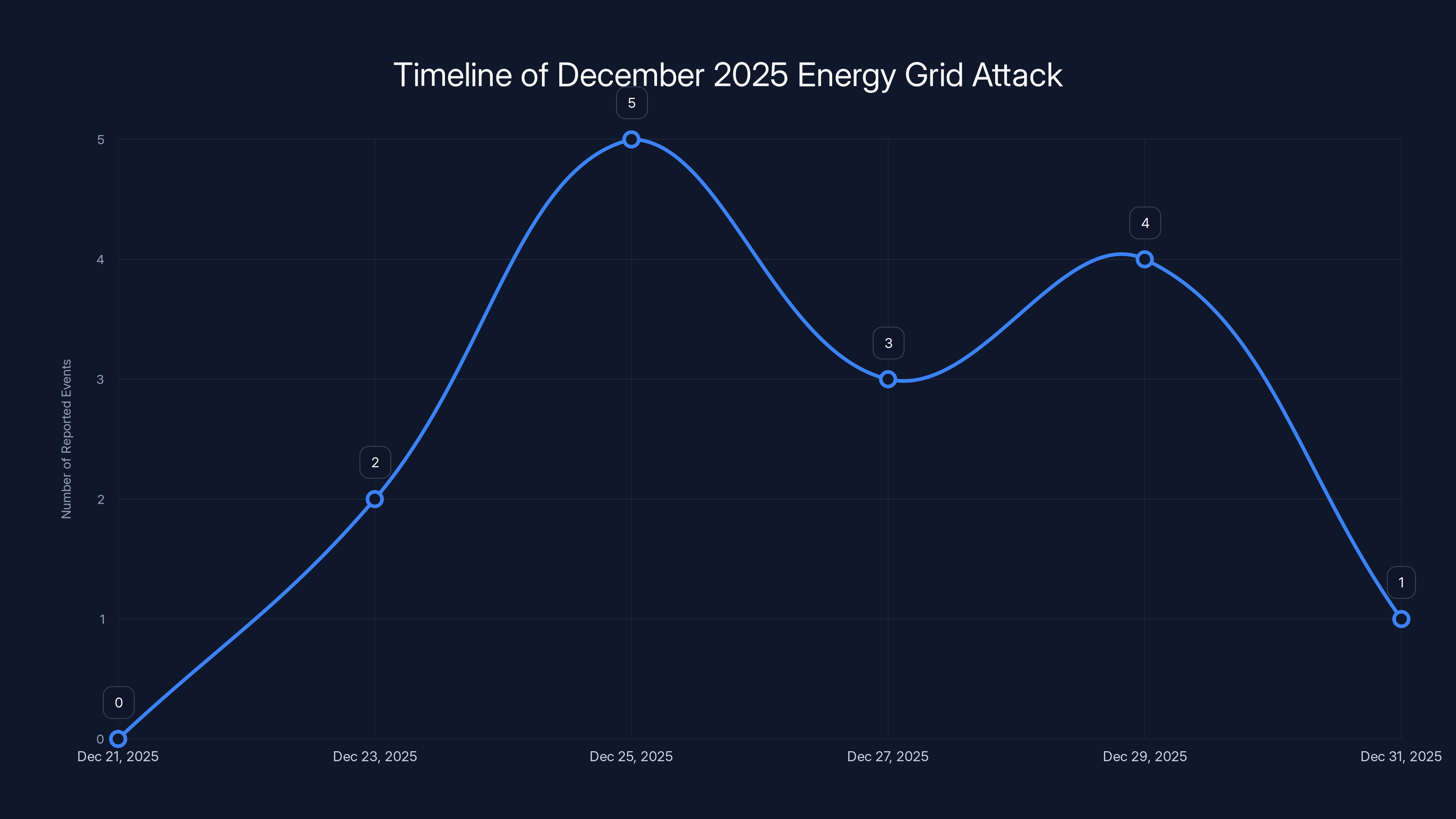

The line chart illustrates the estimated impact of major cyberattacks on power grids over the years. The 2025 attack on Poland's grid, despite its sophistication, resulted in zero outages, highlighting improved defenses. Estimated data.

The Evolution of Cyberwarfare Strategies

What's interesting about the Poland attack is how it fits into the broader evolution of how Russia conducts cyber operations. The strategy has changed over the decade from the first Ukraine attack to now.

The 2015 Ukraine attack was basically a proof of concept. Russia demonstrated that they could directly control power grid systems and cause a blackout. They proved the threat was real. The attack was destructive but geographically limited.

In the years between 2015 and 2022, Russia refined its approach. They deployed wipers against Ukrainian networks repeatedly, improving their capabilities each time. They studied defensive responses. They learned what worked and what didn't.

Then came 2022 and the invasion of Ukraine. Suddenly, cyber operations became part of active warfare. Acid Rain targeting satellite communications. Wipers targeting government networks. Denial of service attacks on banking systems. Cyber operations coordinated with kinetic military operations.

But invading Ukraine had limits. NATO didn't join militarily. The invasion got bogged down. And now, in late 2025, Russia seems to be testing a new phase: direct attacks on NATO critical infrastructure without crossing the line into kinetic warfare.

The Poland attack might be part of that testing phase. How much can Russia get away with before NATO responds? What's the threshold for cyber operations before it becomes a casus belli for military response? Where exactly is the line?

Nobody knows the answer. That ambiguity is terrifying because it creates incentive for escalation. Russia has every reason to keep probing. To keep testing. To keep pushing. The costs are relatively low. The information gained is valuable. And the risk of direct NATO response remains unclear.

Meanwhile, NATO countries are trying to figure out how to respond. Do they conduct retaliatory cyberattacks? Do they impose sanctions? Do they increase military posture? Do they publicly expose the attackers? Each option has risks and benefits. None of them has been tested at scale yet.

Implications for the Future of Energy Security

The Poland attack has implications that extend far beyond Poland. It affects how every energy company in the world thinks about cybersecurity. It affects policy decisions. It affects investment priorities. It affects how countries think about energy independence and resilience.

First, it reinforces the vulnerability of distributed renewable energy systems. As power grids move away from centralized generation toward distributed renewable sources, they're introducing new complexity and new vulnerabilities. Every solar installation, every wind farm, every battery storage facility is a potential attack vector. Securing all of that requires a fundamentally different approach than securing centralized power plants.

Second, it highlights the importance of redundancy and resilience. Power grids need to be able to operate even when communications systems are degraded or destroyed. That means falling back to manual operations. That means local control capabilities. That means training operators to run the grid the way they did before computers. Many modern operators have never done that. It's a skill that's being lost.

Third, it suggests that power companies need to invest much more heavily in cyber defenses. The cost of a successful attack is so high that spending millions or tens of millions on security is actually cheap insurance. But many utilities have been slow to make those investments. The Poland attack might change that calculation.

Fourth, it implies that international cooperation on cyber defense is essential. The Poland attack wasn't just Poland's problem. It was a NATO problem. It was a European problem. Solving it requires information sharing, coordinated response, and unified deterrence.

Estimated timeline showing the frequency of reported events during the December 2025 attack. The peak on December 25 indicates heightened activity or reporting.

The Role of Attribution and Geopolitics

ESET's attribution of the attack to Sandworm with "medium confidence" is actually quite high certainty by attribution standards. But the phrasing reveals something important: attribution is hard. Even with malware analysis and behavioral analysis, you can't be 100% certain who launched an attack.

That ambiguity has geopolitical consequences. Russia can deny responsibility. They can claim they don't know anything about it. They can point to the possibility that someone else deployed malware and framed Russia. And because complete certainty is impossible, there's just enough plausible deniability for some people to believe them.

But the technical evidence is compelling. The malware used Sandworm's tradecraft. The TTPs matched previous Sandworm operations. The targeting matched Russian strategic interests. The timing matched the 10th anniversary of the Ukraine attack, suggesting symbolic significance.

All of that points toward Sandworm. Medium confidence is actually quite high. It's probably right.

But from a policy perspective, the fact that attribution is ambiguous matters. It means responding to the attack is politically complicated. International law doesn't clearly define how to respond to cyberattacks. Military response to a cyberattack is unprecedented. Economic sanctions require international agreement. Diplomatic protests can be dismissed as baseless accusations.

Russia understands this advantage. They understand that cyberattacks exist in a gray zone where response is uncertain. They understand that they can probe and test and demonstrate capability, and the response will be muted because nobody wants to escalate to shooting war.

That calculus might be changing. The newer NATO members, particularly those in Eastern Europe and the Baltics, have been pushing for more aggressive responses to cyberattacks. They've experienced Russian cyber operations firsthand. They understand the threat differently than Western European countries or North America.

Poland is a stronger voice within NATO after the Ukraine crisis demonstrated Russia's willingness to invade. If Poland demanded a strong NATO response to the energy grid attack, they might get it. That would be a significant escalation.

Defensive Measures Energy Companies Should Implement Now

Regardless of what policymakers decide, energy companies need to act now. They can't wait for government guidance. They can't assume government will protect them. They have to protect themselves.

The first priority is detection. You have to know when you're being attacked. That means investing in security monitoring, in threat intelligence, in incident response capabilities. That means hiring and retaining security talent in an incredibly competitive market. That means building relationships with threat intelligence providers who can give you early warning of attacks being developed against your sector.

The second priority is segmentation. Critical control systems that manage power distribution should not be connected to networks that communicate with renewable installations. They should not be connected to the internet. They should not be reachable from email systems or administrative networks. The isolation should be absolute. If an attacker gets into your business network, they shouldn't be able to reach your control systems.

The third priority is backup and recovery. You need backups of everything. But you need backups that are stored completely separate from your production systems. Offline. In different geographic locations. Encrypted. Protected. If an attacker wipes your production systems, you need to be able to restore from backups that the attacker couldn't reach.

The fourth priority is resilience and redundancy. Build systems that can operate even when parts of them are unavailable. Have fallback communications. Have manual processes that staff can follow if automated systems fail. Train people on those manual processes regularly so they're not just theoretical.

The fifth priority is recovery time. Plan how long it would take to restore systems from backups. Work to reduce that time. Because the longer your critical systems are offline, the more people are without electricity, the more pressure there is to make bad decisions.

The sixth priority is information sharing. Join industry information sharing organizations. Share intelligence with peers about attacks you've experienced or defended against. The more the industry collectively knows about attacks, the better everyone's defenses become.

None of this is cheap. None of this is quick. But the alternative is remaining vulnerable to attacks like Dyno Wiper. And if the next attack succeeds where Dyno Wiper failed, the costs will be measured in billions of dollars and in people suffering without electricity.

NATO's Strategic Response Options

NATO faces a difficult strategic choice about how to respond to the Poland attack. Each option has merits and drawbacks.

The most modest response would be diplomatic: release a statement attributing the attack to Russia, demand they stop, warn of consequences if attacks continue. This response is low-risk politically. It doesn't escalate. But it's unlikely to deter Russia if they didn't intend Dyno Wiper to succeed anyway. A statement saying "stop doing what you might have intended to do, which you failed at anyway" carries no weight.

A stronger response would include economic sanctions targeting Russian officials, institutions, or technology companies. This has precedent. NATO countries have already imposed sanctions on Russia over the Ukraine invasion. Targeted sanctions related to cyberattacks would be an extension of existing policy. The risk is that Russia responds with their own sanctions, and the economic relationship between NATO countries and Russia deteriorates further. But that relationship is already pretty far degraded.

A more aggressive response would be retaliatory cyberattacks. NATO countries could attack Russian critical infrastructure in return. A power grid for a power grid. But this is extremely risky because cyberattacks are unpredictable. Attacking Russian infrastructure might cause damage outside Russia. It might escalate the conflict in ways that are hard to control. It might provoke military response. This option is probably too risky for defensive actions.

The most aggressive response would involve military or quasi-military measures, though it's unclear what those would look like. Increased military presence in Poland. Naval deployments. Air force exercises. These are symbolic, not direct responses to the cyberattack, but they communicate resolve and raising the cost of aggression.

Most likely, NATO will respond with a combination: public attribution, sanctions, increased military presence, and private warnings through diplomatic channels. This calibrated response signals that cyberattacks are taken seriously without escalating to kinetic conflict.

But from a deterrence perspective, the question remains: is that enough to deter Russia from future attacks? Or will Russia continue probing NATO defenses, testing the boundaries, waiting to see how far they can push?

Looking Forward: What Comes Next?

The Poland attack almost certainly isn't the end of Russian cyberattacks against critical infrastructure in NATO countries. It's probably the beginning of a new phase. Russia has demonstrated they can deploy custom malware against European energy grids. They've proven they can get inside these systems. They've tested NATO's response capabilities.

We should expect more attacks. We should expect them to be more sophisticated. We should expect Russia to incorporate what they learned from Dyno Wiper's failure into future operations. The next attack might succeed where this one failed.

From a defensive perspective, energy companies and governments need to accelerate security investments. They need to move faster on network segmentation, backup strategies, and incident response capabilities. They need to hire and train more security personnel. They need to share threat intelligence aggressively.

From a policy perspective, NATO needs to decide what deterrence looks like for cyberattacks. Is sanctions enough? Do they need to establish escalation thresholds? Do they need to make clear that successful attacks on critical infrastructure will trigger military response? The ambiguity is actually destabilizing because it creates incentive for Russia to test the boundaries.

From a technology perspective, there need to be innovations in how power grids operate during cyberattacks. More resilient communications. Better distribution of control systems. Automation that degrades gracefully instead of failing completely. Some of this is already happening, but it needs to accelerate.

From a geopolitical perspective, the Poland attack is just one data point in a larger story about Russia's willingness to use cyberwarfare as a strategic tool against NATO. It's part of the hybrid warfare strategy that includes information operations, conventional military pressure, and economic coercion. Understanding cyberattacks as part of that broader strategy is essential.

The next year will be telling. Will Russia continue testing Polish defenses? Will they target other NATO countries? Will they graduate from testing to actual operations designed to cause maximum damage? Will NATO establish clear red lines and consequences? Or will the ambiguity continue, with cyberattacks becoming an accepted part of the new normal?

No one knows. But the Poland attack gives us a glimpse into a future where critical infrastructure in the developed world faces constant pressure from sophisticated state-sponsored attackers. We're not ready for that future. We're probably decades away from being ready. Which means it's time to get serious about catching up.

FAQ

What is wiper malware and how is it different from other types of cyberattacks?

Wiper malware is a destructive attack designed specifically to erase data and render systems completely inoperable. Unlike ransomware that extorts victims or spyware that steals information, wipers have one goal: permanent destruction. Once deployed, they systematically overwrite files, corrupt databases, and destroy boot sectors, leaving investigators with minimal forensic evidence. The critical difference is that while ransomware victims can decrypt their data by paying ransom, and spyware victims can remove the intruding software, wiper victims have no recovery option without previously created backups stored completely outside the compromised network.

Who is Sandworm and why are they considered such a significant threat?

Sandworm is a sophisticated Russian state-sponsored hacking group with a documented history of destructive cyberattacks against critical infrastructure since at least 2015. They became infamous for orchestrating the first confirmed malware-facilitated power grid blackout in Ukraine in December 2015, leaving 230,000 people without electricity in winter conditions. Since then, they've deployed multiple custom wiper variants including Acid Rain and Not Petya, demonstrating consistent capability to develop sophisticated attack tools tailored to specific targets. Their threat level is particularly high because they have nation-state resources, institutional knowledge, and apparent immunity from traditional law enforcement consequences.

Why did the Dyno Wiper attack against Poland's energy grid fail to cause a blackout?

The exact reason for Dyno Wiper's failure remains unexplained, though researchers confirmed no successful disruption occurred. Possible explanations include: Poland's cyber defenses successfully detected and contained the malware before it could spread; the custom wiper had technical flaws that prevented execution in the target environment; or Russia intentionally didn't fully activate the attack to avoid escalating to kinetic NATO response. The third explanation is particularly troubling because it would indicate Russia is using cyberattacks as messaging tools to demonstrate capability and test defenses rather than attempting immediate disruption.

What is the relationship between the Poland attack and the 2015 Ukraine power grid attack?

The Poland attack occurred on December 23, 2025, marking the exact 10-year anniversary of Russia's December 23, 2015 cyberattack that knocked out Ukrainian power systems. That 2015 attack was historically significant as the first confirmed instance of malware causing a physical power outage, affecting 230,000 customers during winter conditions. The timing of the Poland attack on this anniversary suggests symbolic significance and demonstrates Russia's continuous willingness to target critical infrastructure in the region. The 2015 attack forced global power companies to take cyberattacks seriously; the Poland attack indicates threats have only intensified.

What makes critical infrastructure, particularly power grids, vulnerable to cyberattacks?

Critical infrastructure faces unique vulnerability challenges because many systems were designed decades ago before modern cybersecurity threats were anticipated. Power grid control systems often run legacy software from the 1980s and 1990s that lacks modern security features. Upgrading these systems is expensive and risky since utilities cannot simply shut down power plants to install patches. Additionally, defenders must secure every possible vulnerability while attackers only need to find one, creating an asymmetric advantage. Distributed renewable energy systems introduce additional complexity by expanding the network perimeter and creating numerous potential attack vectors that didn't exist in centralized power generation models.

How should energy companies protect themselves against sophisticated wiper attacks like Dyno Wiper?

Energy companies should implement multi-layered defenses including: complete network segmentation with critical control systems isolated from business networks and the internet; continuous security monitoring and threat detection systems; regular incident response exercises and tabletop simulations; offline encrypted backups stored in geographically separate locations; backup manual operational procedures for when automated systems fail; investment in skilled security personnel and threat intelligence partnerships; and formal participation in industry information-sharing organizations. Recovery time is critical, so companies should regularly test how quickly they can restore operations from backups. These measures require significant investment but cost far less than recovering from a successful attack that disrupts power to millions of people.

What does the Poland attack reveal about NATO's capacity to respond to cyberattacks?

The Poland attack exposes a significant strategic ambiguity in NATO's response doctrine. While NATO members have collectively stated that cyberattacks could trigger Article 5 collective defense, no cyberattack has ever done so in practice. This ambiguity creates perverse incentive for Russia to continue testing boundaries and probing defenses, since responses are unpredictable and potentially limited. NATO must establish clearer thresholds for what constitutes an attack serious enough to trigger military response, develop retaliatory capability equivalent to attacks suffered, and coordinate with allies on proportionate responses including sanctions and military posturing. Without clarity, Russia will continue treating cyberattacks as a tool within an acceptable risk band.

Why is Not Petya considered the most expensive cyberattack in history?

Not Petya, released in 2017, demonstrates the catastrophic risk of wipers escaping their intended target. Originally designed to target Ukrainian accounting software, Not Petya spread globally and infected hundreds of thousands of computers across multiple continents. Within days, the destructive malware had caused an estimated $10 billion in damage by corrupting systems in major corporations including shipping companies, logistics firms, advertising agencies, and manufacturers. The incident proved that cyberweapons cannot reliably be contained to geographic or sectoral boundaries, and that a single piece of malware can cause more economic damage than traditional terrorist attacks. It remains the cautionary tale that makes Russia hesitant to deploy wipers with maximum aggressive intent.

How does the Poland attack fit into Russia's broader hybrid warfare strategy?

The Poland attack represents an escalation in Russia's hybrid warfare approach that combines cyberattacks, military pressure, information operations, and economic coercion. Since the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Russia has demonstrated willingness to integrate cyber operations with military objectives, as seen in Acid Rain attacks on satellite communications coordinated with invasion tactics. The Poland attack suggests Russia is now testing whether similar cyberattacks against NATO members will trigger military response or remain within acceptable risk boundaries. By targeting critical infrastructure in a NATO country but failing to cause actual disruption, Russia can gather intelligence about Polish defenses and NATO response thresholds without triggering the threshold for military retaliation.

What international policy changes might result from the Poland cyberattack?

The Poland attack will likely drive policy discussions about establishing clearer NATO cyber doctrine, including defining what constitutes an act of war under Article 5; implementing coordinated economic sanctions against Russian individuals and institutions responsible for cyberattacks; increasing military presence and capabilities in Eastern European NATO members; developing offensive cyber capabilities for retaliatory response; strengthening critical infrastructure protection standards across NATO; and improving information sharing among allies about cyberattack methods and indicators of compromise. Poland's strong voice within NATO following the Ukraine crisis means their response will carry particular weight in shaping collective NATO policy on cyberwarfare.

Conclusion: Living With Constant Threat

The Poland energy grid attack reveals an uncomfortable truth about life in 2025: critical infrastructure is under constant assault from sophisticated state-sponsored attackers, and our defenses are inadequate.

That's not alarmism. That's just reality. Russia has demonstrated repeatedly that they can penetrate energy systems. They can deploy custom malware. They can cause disruption. The only question each time is whether the attack succeeds or fails, and success has nothing to do with the sophistication of the attack and everything to do with factors largely outside the control of defenders.

The fact that Dyno Wiper failed is not comforting. It's terrifying because it means we still don't know why. Was it luck? Was it good defense? Was it Russian restraint? Without understanding why the attack failed, we can't ensure that the next attack will also fail.

Energy companies across Europe and North America need to treat this attack as a wake-up call. They need to accelerate security investments. They need to implement redundancy and resilience. They need to plan for failure. They need to test their recovery capabilities. They need to hire security talent. They need to invest in monitoring. They need to segregate networks. They need backups stored offline.

Governments need to establish clear policy about how NATO responds to cyberattacks. Is sanctions enough? Do threshold attacks trigger military response? What's the escalation ladder? Right now, that ambiguity is destabilizing because it creates incentive for Russia to keep testing.

Technology companies building infrastructure management systems need to prioritize security in design. They need to assume from the beginning that attackers will get in, and design systems to degrade gracefully instead of failing completely. They need to build in redundancy. They need to enable manual control of critical systems.

The Poland attack was either a message ("we can get in, and we're not stopping") or a failed attempt ("we tried, and we'll try again differently"). Either interpretation suggests more attacks are coming. Better defenses are essential.

The good news is that this situation is not inevitable. Better defenses are possible. Resilience is achievable. The bad news is that it requires sustained investment, hard work, and difficult political decisions that nobody wants to make during peacetime.

Poland's energy grid survived Dyno Wiper. The question is whether the next attack will be as forgiving.

Key Takeaways

- DynoWiper wiper malware attacked Poland's energy grid on the 10th anniversary of Russia's 2015 Ukraine blackout attack, but failed to disrupt electricity

- Wiper malware is fundamentally more dangerous than ransomware or spyware because it permanently destroys data with no recovery option without external backups

- Russia-aligned Sandworm group has deployed increasingly sophisticated cyberattacks against critical infrastructure since 2015, with NotPetya causing $10 billion in damages

- The reason DynoWiper failed remains unknown, suggesting either strong Polish defenses, technical flaws, or intentional Russian restraint to avoid NATO escalation

- Energy companies must implement network segmentation, offline backups, incident response procedures, and redundancy to survive sophisticated cyberattacks targeting critical infrastructure

Related Articles

- Russian Hackers Targeted Poland's Power Grid: What Happened [2025]

- Critical Cybersecurity Threats Exposing Government Operations [2025]

- LinkedIn Phishing Scam Targeting Executives: How to Protect Yourself [2025]

- What We Know About Major Winter Storms Hitting the US [2025]

- LastPass Phishing Scam: How to Spot Fake Support Messages [2025]

- Most Spoofed Brands in Phishing Scams [2025]

![Poland Energy Grid Wiper Malware Attack: What Really Happened [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/poland-energy-grid-wiper-malware-attack-what-really-happened/image-1-1769283410230.jpg)