Polish Energy Infrastructure Under Fire: The December Cyberattack That Nearly Crippled a Nation

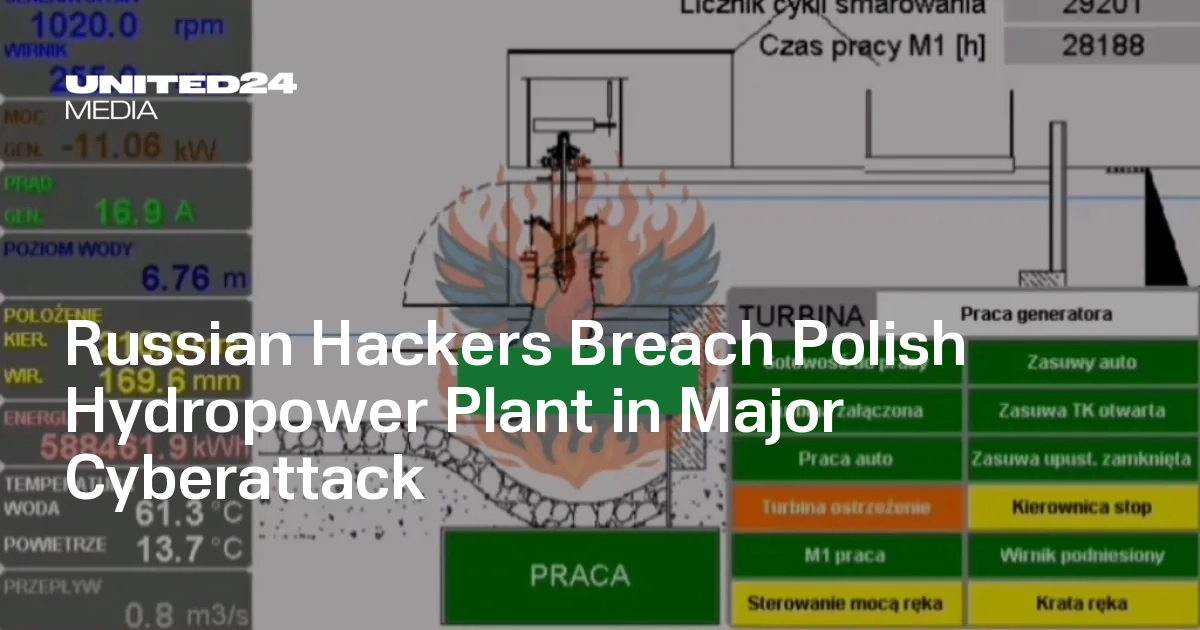

On December 29 and 30, something terrifying almost happened in Poland. Not a natural disaster, not a mechanical failure, but something potentially more dangerous in our interconnected world: a coordinated cyberattack designed to destroy critical infrastructure and leave hundreds of thousands of people without heat and electricity during winter.

The target was Poland's energy grid. The attackers were Russian government hackers. The weapon was destructive malware that could have wiped machines clean, making them completely unusable. And here's the sobering part: the attack nearly worked.

Polish Energy Minister Milosz Motyka called it the strongest attack on the country's energy infrastructure in years. Two heat and power plants were directly targeted. The hackers also attempted to disrupt communication links between renewable energy installations like wind turbines and the distribution operators who manage power flow. If successful, the attack could have left at least half a million homes without heat during the freezing Polish winter.

But the attack failed. Poland's cybersecurity defenses held. No power was cut. No homes went dark. Life continued.

Yet this incident tells us something critical about the state of modern warfare, the fragility of infrastructure we depend on every day, and the escalating sophistication of state-sponsored cyber operations. This wasn't a ransom demand. This wasn't corporate espionage. This was a nation-state deliberately trying to cause physical harm to civilians by destroying the systems that keep them warm and alive.

And if you think this is just a Polish problem, you're missing the bigger picture. Every country with an electrical grid, a water system, or critical infrastructure is watching Poland right now, realizing that this could happen to them next.

Let's break down what actually happened, who did it, and what it means for cybersecurity around the world.

TL; DR

- Russian military hackers (Sandworm) attempted to destroy Poland's power infrastructure on December 29-30 using destructive "wiper" malware called Dyno Wiper

- The attack targeted two heat and power plants plus communication systems linking renewable energy installations to distribution operators

- Half a million homes could have lost power during winter if the attack had succeeded, but Poland's defenses held

- This mirrors a 2015 Sandworm attack on Ukraine that knocked out power for 230,000 homes and established the playbook for targeting energy grids

- The implications are serious: Nation-states are now directly targeting civilian infrastructure with destructive intent, marking a dangerous escalation in cyber warfare tactics

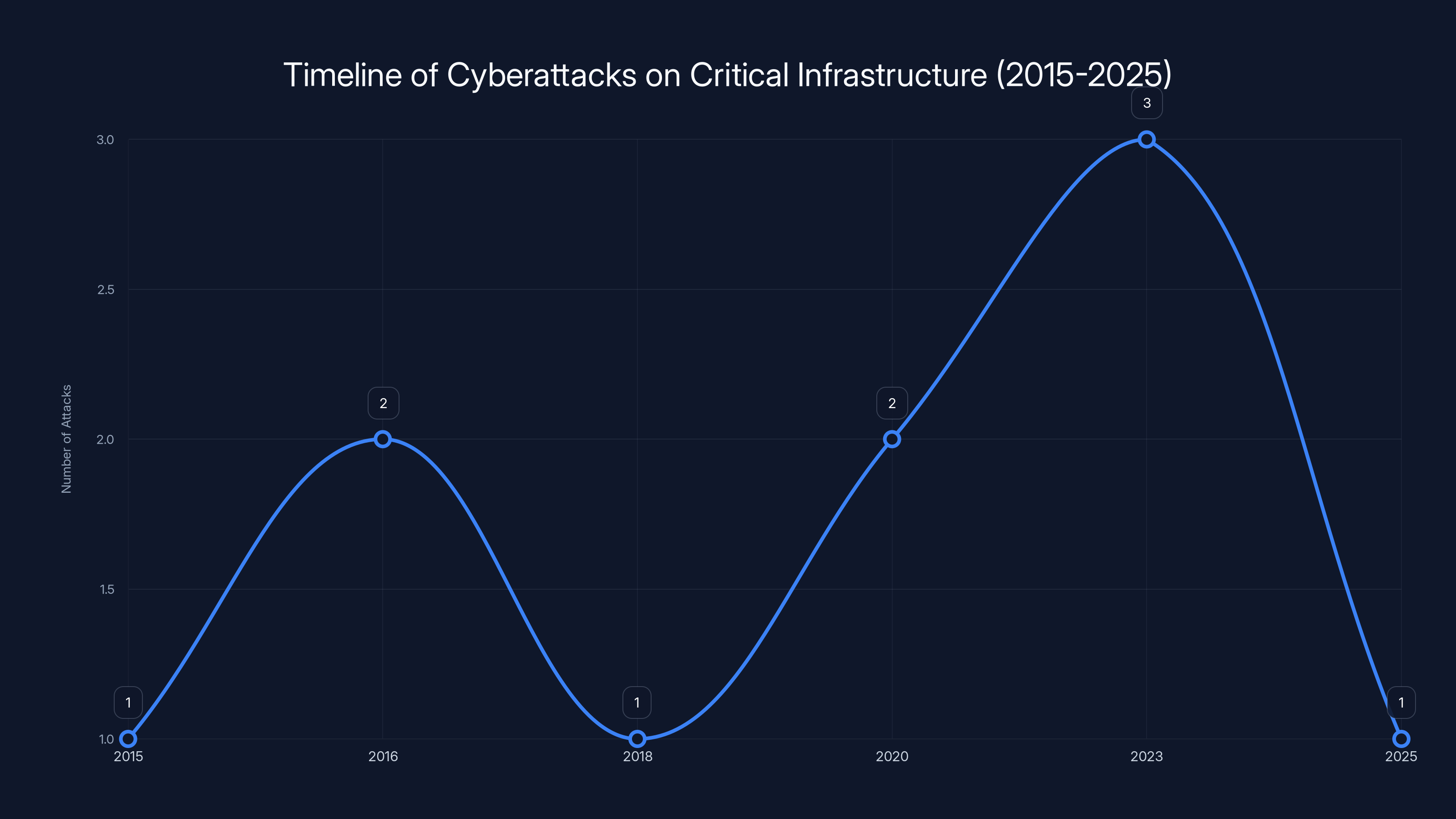

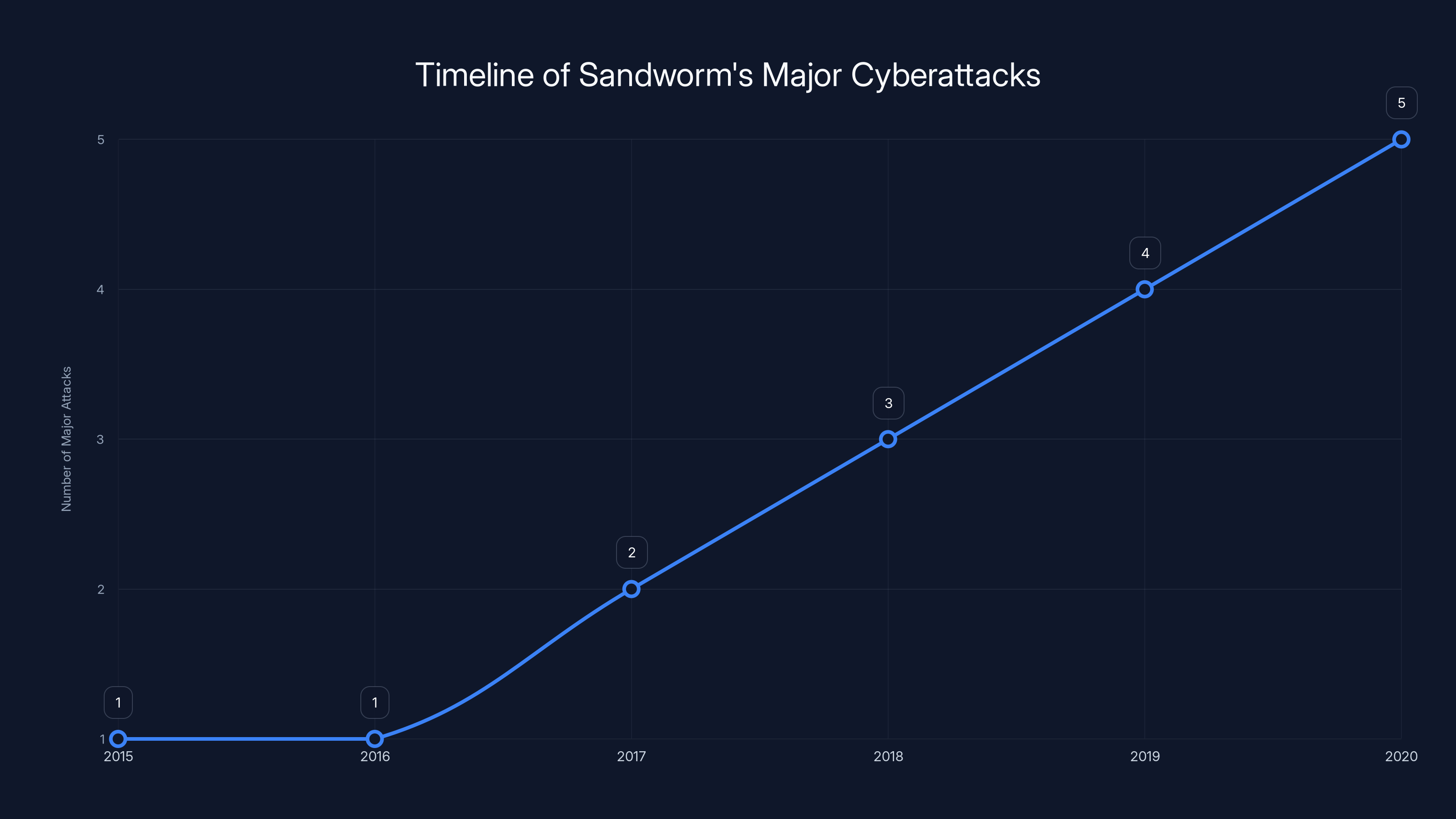

This line chart illustrates the frequency of major cyberattacks on critical infrastructure attributed to Sandworm from 2015 to 2025. The data shows an increasing trend in attacks, peaking in 2023. (Estimated data)

Understanding the Attack: What Happened on December 29-30

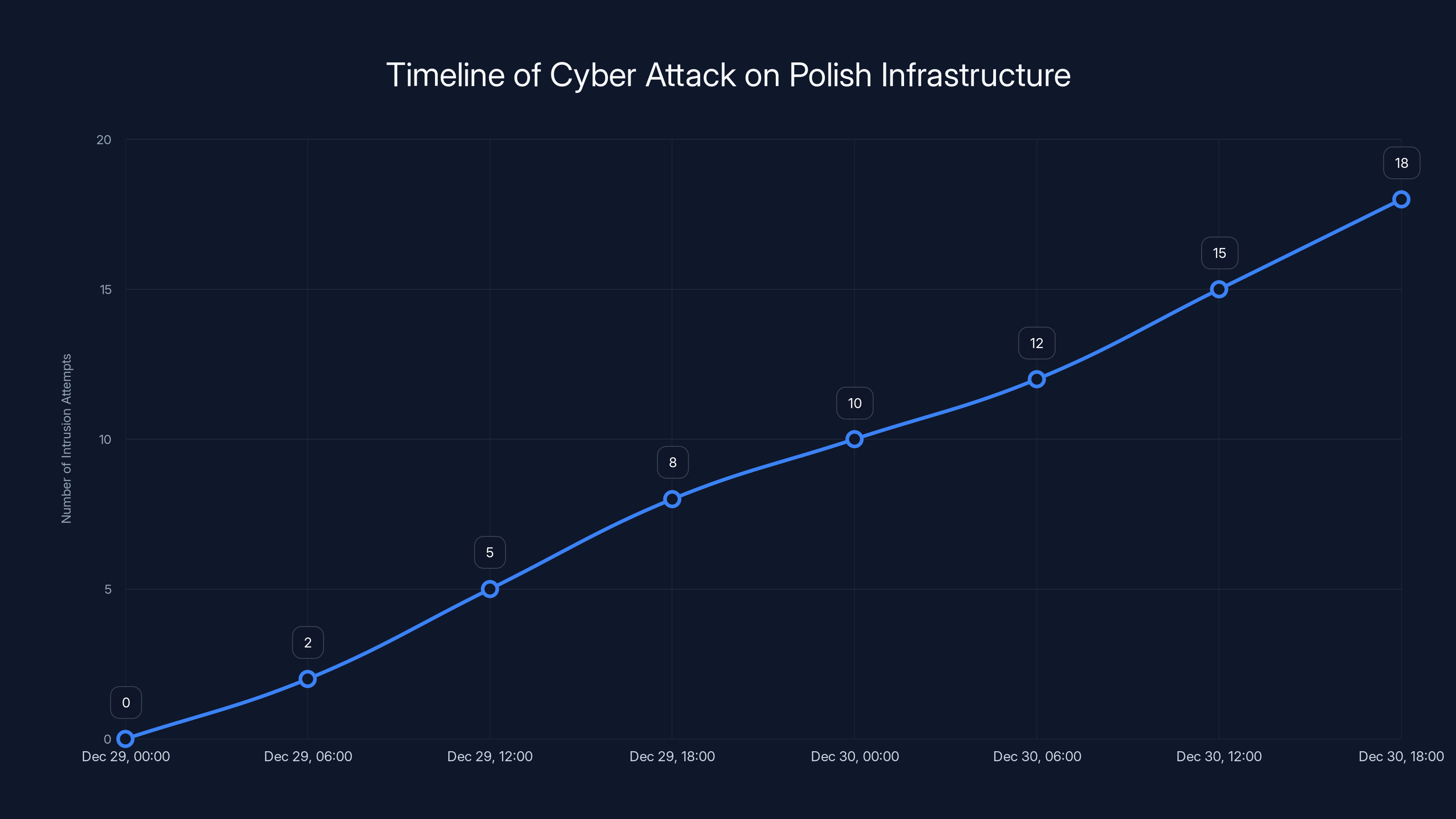

The timeline of the attack is important because it shows the deliberation and coordination involved. This wasn't a probe or a test. This was a planned operation timed for maximum impact.

On December 29 and 30, Polish security agencies detected multiple intrusion attempts targeting the country's energy infrastructure. The attackers weren't looking to steal data or extort money. The malware they deployed was specifically designed to destroy data irreversibly and render computers completely inoperable.

The affected systems weren't random. Two heat and power plants were primary targets. These facilities generate and distribute both electricity and heating, making them critical infrastructure that affects hundreds of thousands of people. The attackers also attempted to compromise the communication networks connecting renewable energy installations like wind farms to the power distribution operators.

Think about what that means. Wind turbines generate power. That power needs to reach people's homes. It does so through a network of computers and communication systems that coordinate production and distribution. If you destroy those communication links, you create a disconnect between supply and demand. You can black out entire regions even if some power plants are still running.

Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk stated that the country's cybersecurity defenses worked and that "at no point was critical infrastructure threatened." That's the official statement. But read carefully: the attack was detected and stopped. The systems held. But the capability was there, the intent was clear, and the operation was sophisticated enough to reach Poland's most critical infrastructure.

The Polish government immediately blamed Moscow. That accusation wasn't speculation or political theater. It was based on technical evidence and the known patterns of Russian cyber operations targeting neighboring countries.

Dyno Wiper: The Destructive Malware Designed to Cripple Infrastructure

The technical details matter because they reveal the sophistication and intent of the operation.

Security researchers at ESET obtained a copy of the malware used in the attack and named it Dyno Wiper. The name is descriptive. This is a wiper, a category of malware specifically engineered to destroy data and disable computers.

Wiper malware is different from the ransomware you might hear about in the news. Ransomware encrypts your files and demands money to decrypt them. The attacker still wants something. Wiper malware just destroys everything. It's designed for maximum damage with zero intention of recovery. It's the nuclear weapon of malware.

The Polish government and international observers immediately recognized the implications. Wiper malware isn't used for espionage, theft, or extortion. It's used when you want to break things. When you want to cause physical-world harm to civilians. When you want to make a political statement through infrastructure destruction.

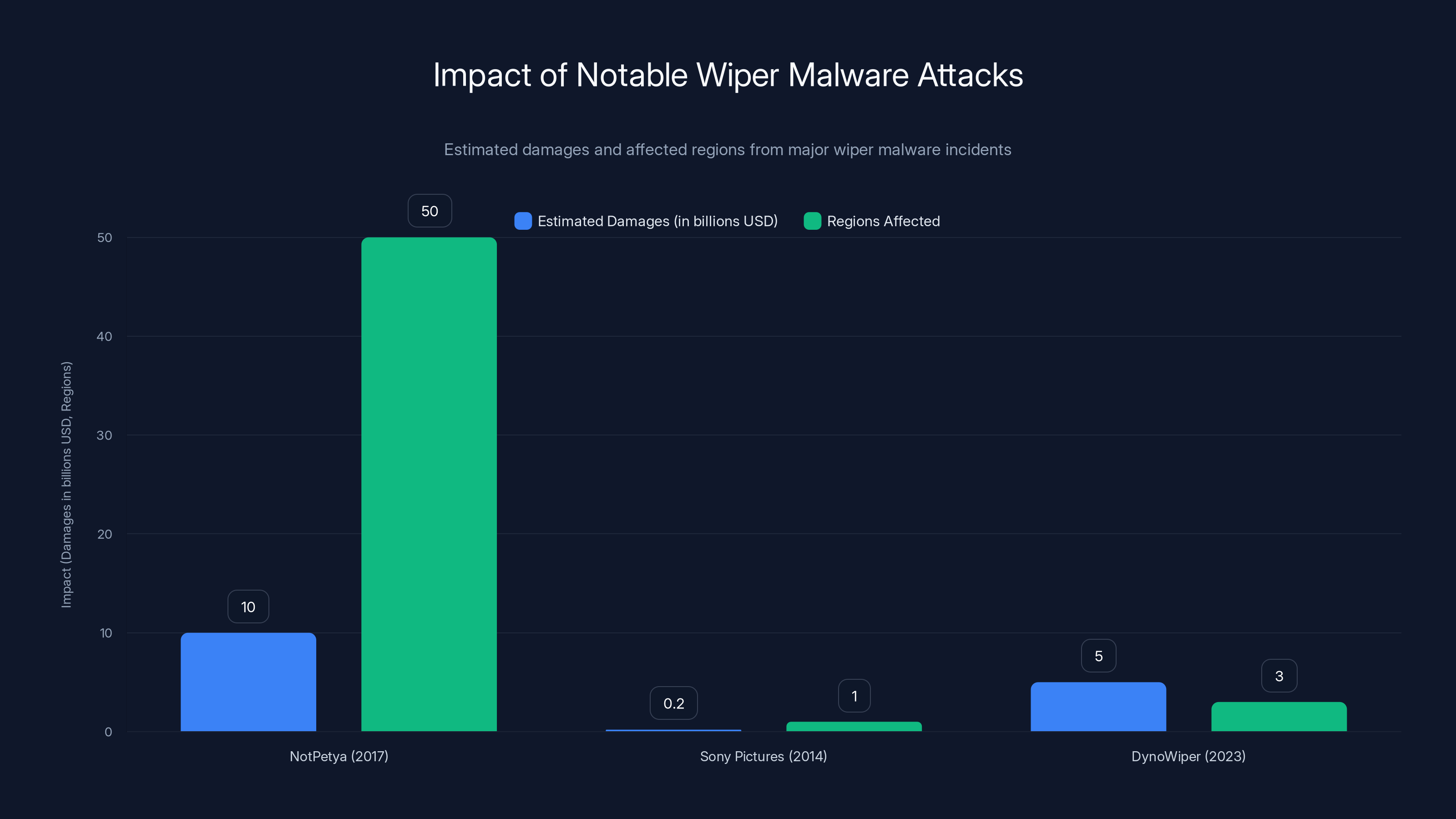

This type of malware has a history. Not Petya was a destructive wiper that spread globally in 2017, causing billions in damages. It wasn't targeting Ukraine specifically, but it devastated Ukrainian infrastructure and spread worldwide. Wiper malware attributed to North Korea destroyed systems at Sony Pictures in 2014. The pattern is clear: destructive wiper malware shows up when state actors want to make a dramatic impact.

Dyno Wiper appears to be custom-built for this specific operation. Researchers found code similarities with previous malware used by the same hacking group, suggesting a sophisticated, purpose-built tool rather than an off-the-shelf weapon.

What makes wiper malware particularly dangerous is that recovery requires physical intervention. You can't simply restore from backup if the malware has overwritten the data. Depending on the sophistication of the attack, you might need to replace entire systems. Imagine a power plant where the control systems have been destroyed. You can't just reboot. You need technicians on-site to manually rebuild the configuration. That takes hours or days. During winter in Poland, hours or days without power isn't inconvenient. It's dangerous.

Estimated data suggests financial gain is the primary motivation for cyberattacks, but a significant portion is also driven by espionage and destruction, often linked to state actors.

Sandworm: The Russian Military Intelligence Unit Behind the Attack

Attribution in cybersecurity is tricky. You rarely have a signed confession. But ESET attributed the attack to Sandworm with "medium confidence" based on technical overlaps with the group's previous work.

Sandworm is a unit within Russia's military intelligence agency, the GRU (Glavnoye Razvedyvatelnoye Upravleniye, or Main Intelligence Directorate). They're not mercenaries or independent hackers. They're an official government cyber operations unit, which means this attack carries the weight of state authorization.

Sandworm has a well-documented history of targeting Ukraine's energy infrastructure. The group conducted what many security researchers consider the first-ever cyberattack to cause a large-scale power outage. On December 23, 2015, Sandworm attacked multiple Ukrainian power distribution companies. The result: more than 230,000 homes lost electricity during winter. It was a watershed moment in cybersecurity. Previously, cyberattacks were theoretical threats to infrastructure. After 2015, they became real, documented events with real victims.

A year later, in December 2016, Sandworm attacked Ukraine again, this time targeting a different power grid operator. Ukraine's infrastructure was becoming a testing ground for Russia's cyber warfare capabilities.

But here's what's important: Sandworm didn't stop with Ukraine. The group has been linked to cyberattacks on Georgian infrastructure, operations against the U. S. power grid, attacks on NATO countries, and intrusions against critical infrastructure globally. They're not just hackers. They're a state-sponsored operational unit conducting what amounts to cyberwarfare.

The fact that the same group now has its sights on Poland is significant. Poland is a NATO member. Poland is part of the European Union. Attacking Polish infrastructure isn't an operation against a neighboring country in a territorial dispute. It's an operation against an alliance member. It's an escalation.

Yet attribution is complex. ESET said "medium confidence," not absolute certainty. That means the technical evidence is strong but not definitive. Sophisticated attackers can leave false flags. They can use tools they didn't develop themselves. Attribution requires matching multiple factors: the tools used, the tactics employed, the timing, the targets, and the outcomes.

In this case, the tools matched previous Sandworm operations. The tactics aligned with their historical methods. The targets were consistent with their previous focus on energy infrastructure. The confidence level reflects the strength of that correlation.

The 2015 Ukrainian Precedent: A Decade of Infrastructure Attacks

The timing of the Poland attack is striking. On December 23, 2015, Sandworm attacked Ukraine's power grid. Exactly a decade later, on December 29 and 30, 2025, Sandworm (allegedly) attacks Poland's power grid.

That's not coincidence. That's a pattern. That's an evolving strategy.

The 2015 Ukraine attack established a playbook. Here's what Sandworm learned: you can disrupt power with cyberattacks. You can reach critical infrastructure through connected systems. You can cause real-world harm to civilians. You can do it and survive the consequences.

Ukraine reported the 2015 attack to international authorities. The United States and other nations attributed it to Russia. But there were no military consequences. No invasion. No direct retaliation. Russia learned that you can attack another nation's critical infrastructure, and the worst that happens is international condemnation and economic sanctions that Russia can work around through alternative economic relationships.

That emboldened Russia to try again. In 2016, another attack on Ukraine. Then attacks on Georgia. Then probes against U. S. infrastructure. Each operation tested the boundaries of what's acceptable. Each operation refined the tactics.

Now, in 2025, Russia is applying those lessons against Poland, a NATO member. This isn't just a continuation of old patterns. This is an escalation.

The Ukrainian precedent also shows us what the consequences of a successful attack would have been. 230,000 homes without power. In winter. With no immediate way to restore it. People died in the 2015 attack. Not directly from the cyberattack, but from the cascade effects: hospitals without power, heating systems offline, water systems failing. That's the reality of infrastructure warfare.

Poland avoided that outcome this time. But the attempt was made. The capability is proven. And if Poland was targeted, other NATO countries are likely in Russia's scope as well.

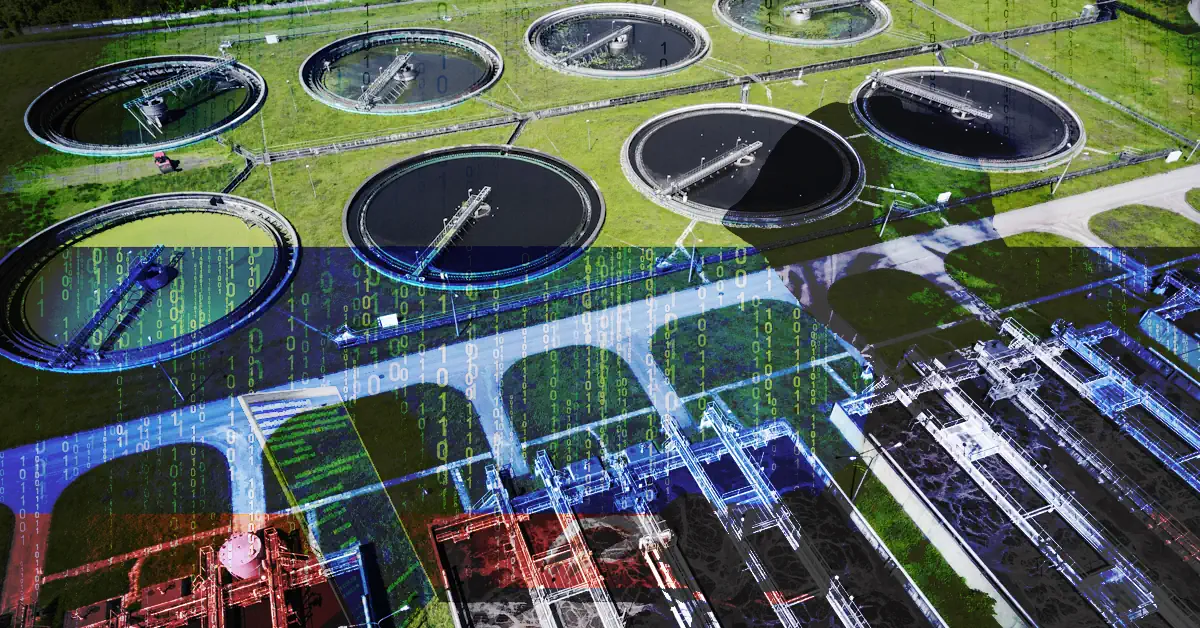

How Energy Infrastructure Became a Cyberattack Target

Power grids seem like they should be unhackable. They're critical systems. They should be heavily protected. So why are they vulnerable?

The answer is complexity and connectivity. Modern power grids are interconnected networks. Your home's electricity comes from a power plant. The power plant receives fuel and instructions. The instructions come from control centers. The control centers communicate with distribution substations. The substations connect to local transformers. Each connection is a potential vulnerability.

More specifically, energy companies have been connecting their operational technology (the systems that actually control power flow) to information technology networks (the systems that manage data and communications). That connectivity makes operations more efficient. It also creates attack vectors.

A power plant operator used to need to be physically present at the plant to operate it. Now they can log in remotely. That's convenient. It's also a potential entry point for an attacker.

Energy infrastructure also runs on systems that were designed decades ago, before cybersecurity was a priority. You have old SCADA systems (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition), old PLCs (Programmable Logic Controllers), and old distributed control systems that were never designed to be connected to the internet or to withstand cyberattacks.

Upgrading this infrastructure is expensive and disruptive. A power plant can't just shut down to install new security systems. It has to keep running. So security often becomes a retrofit, a system layered on top of older infrastructure rather than built into it from the start.

Industrial control systems also use specialized protocols and tools that security researchers aren't always familiar with. General cybersecurity knowledge doesn't directly translate to understanding power grid vulnerabilities. There's a skills gap. There's a knowledge gap.

Addition to this the fact that energy infrastructure is often operated by smaller companies with limited cybersecurity budgets. A major power company might have a dedicated security team. A smaller utility might have one person managing security for the entire operation. The Sandworm attack on Ukraine targeted smaller distribution companies, not just major generators. That was strategic. Smaller targets have weaker defenses.

The chart illustrates the increasing number of intrusion attempts detected over the two-day period, highlighting the coordinated nature of the attack. Estimated data.

The Wiper Strategy: Destruction as Political Messaging

Why use wiper malware instead of ransomware? Why try to destroy instead of encrypt and extort?

The answer tells us something about Russia's strategic intent. Ransomware is a profit-seeking attack. Wiper malware is a statement. It's saying: "I can hurt you. I can destroy your critical infrastructure. There's nothing you can do about it."

Ransom demands are about extracting money. They're pragmatic. Destruction is about demonstrating power and will. It's about making a political point. It's about showing that you can harm a NATO ally and there will be no military consequence.

From Russia's perspective, there's another advantage to wiper malware: it's harder to negotiate with. You can't demand ransom from a power plant operator and hope they pay. They have no mechanism to pay you. The government has to step in. That escalates the incident from a criminal matter to a national security matter.

For the attacker, that's the point. Wiper attacks on infrastructure are acts of war, not crime. They're meant to send a message to the government, not to the operator of the individual system.

The choice to use destructive malware also suggests that Russia wasn't primarily seeking to steal information. If they wanted intelligence on the Polish energy grid, they wouldn't use wiper malware. They'd use espionage tools that hide their presence and allow long-term monitoring. Wiper malware is noisy. It destroys things. It gets noticed.

The fact that they chose destruction over espionage or extortion suggests this was about demonstrating capability and testing Poland's defenses. It was a capability demonstration.

Poland's Defense: How Systems Held Under Attack

Here's the good news: the defenses worked. Poland detected the attack. Poland blocked it. Poland prevented the destruction.

But how? What made the difference between this attack failing and the 2015 Ukraine attack succeeding?

Poland learned from Ukraine's experience. After the 2015 attacks, Ukraine and other NATO allies worked with the United States and international partners to strengthen their energy grid defenses. Poland invested in intrusion detection systems. They set up monitoring. They created isolated networks so that if one part of the infrastructure is compromised, the entire grid doesn't collapse. They trained security personnel. They built redundancy into critical systems.

They also improved information sharing. Ukraine, Poland, and other countries now share threat intelligence about Sandworm and other Russian cyber operations. When Ukraine detects an attack technique, they report it. When Poland sees similar activity, they know what to look for.

Prime Minister Tusk's statement that "at no point was critical infrastructure threatened" is important. It means the attack didn't reach the operational systems. The attackers either failed to get past the defensive perimeter, or they got in but couldn't progress to the critical systems.

This is a critical distinction. A cyberattack on energy infrastructure typically has multiple stages. First, you need to get inside the network. That might be through phishing, a vulnerable server, or a compromised supplier. Second, you need to move laterally through the network, going from less-critical systems to more-critical ones. Third, you need to reach the operational systems that actually control power flow. Fourth, you deploy your malware or commands to disable those systems.

Poland's defenses apparently held at some point in that chain. Whether at the perimeter, in the lateral movement phase, or at the operational systems level, the attack didn't achieve its objective.

That doesn't mean Polish infrastructure is unhackable. It means that this particular attack, from this particular group, at this particular time, was unsuccessful. Future attacks might be more sophisticated, better-targeted, or exploit vulnerabilities Poland hasn't yet discovered.

NATO's Response: What Does Article 5 Mean for Cyberattacks?

Poland is a NATO member. NATO members have a collective defense clause, Article 5. An attack on one is considered an attack on all. But does that apply to cyberattacks?

NATO's position on cyberattacks has evolved. In 2016, NATO agreed that cyberattacks could trigger Article 5. But the bar is high. The attack has to be serious enough to be considered an armed attack, not just espionage or minor disruption.

The Poland attack, had it succeeded, might have crossed that threshold. Destroying power infrastructure during winter, causing deaths among the civilian population, would be serious enough to potentially invoke collective defense. But because the attack failed, the question is moot.

Still, the incident raises the question: what does NATO do when a member is attacked but the defense holds? You can't invoke Article 5 if the attack was successfully defended. But you can take other actions: sanctions, diplomatic protests, military posturing, or cyber retaliation.

None of those has happened yet, at least not publicly. The public response has been diplomatic: condemnation of Russia, reaffirmation of Poland's security, and probably a lot of classified threat intelligence sharing.

The question for NATO going forward is whether relying on technical defenses is sufficient or whether there needs to be a more strategic response to cyber operations that target member states. If Russia can probe NATO infrastructure without consequence, what's to stop them from trying again?

NotPetya caused the most widespread damage with an estimated

The Broader Pattern: Russian Cyber Operations Against Neighboring Countries

The Poland attack isn't isolated. It's part of a pattern of Russian cyber operations against its neighbors, particularly those that are NATO members or are moving closer to the West.

Georgia experienced major cyberattacks in 2008 around the time of military conflict. Ukraine has been targeted repeatedly since 2014. Estonia experienced major cyberattacks in 2007. Lithuania, Latvia, Poland, and other Eastern European countries have all reported Russian cyber intrusions.

The targets aren't random. They're countries that: 1) are former Soviet satellites now moving toward the West, 2) border Russia or are in Russia's perceived sphere of influence, and 3) have strategic infrastructure that Russia wants to disrupt or could use as leverage.

The timing is also strategic. Cyberattacks often coincide with military exercises, political tensions, or negotiations. They're used as a negotiation tactic, a warning, or a demonstration of capability.

Esperitus have called this "hybrid warfare." It's a combination of military operations, propaganda, disinformation, cyberattacks, and economic pressure used together to achieve political objectives. The cyberattack alone might not achieve the goal, but combined with other pressure, it might.

From Russia's perspective, there are advantages to cyberattacks. They're deniable. They don't directly violate international law (laws against cyberattacks are still being written). They can cause real damage without visible military operations. And they test defenses without committing military forces.

For the West, the challenge is that the same advantages that make cyberattacks attractive to Russia make them difficult to counter. How do you respond to an attack that might be deniable? How do you deter an attack that carries low military risk? How do you coordinate a response when different nations have different cyber capabilities?

The Escalation Ladder: From Espionage to Destruction

Historians of technology often point out that new weapons go through phases. First, they're used for gathering intelligence. Then for disruption. Then for destruction. Then for large-scale warfare.

Cyberattacks on infrastructure are moving through that progression. The early attacks (2007 Estonia, 2008 Georgia) were disruptive but not destructive. They knocked services offline but didn't permanently damage infrastructure. The 2015 Ukraine attack was the first major destructive attack. It actually broke things that took time to repair.

The Poland attack represents another step on that escalation ladder. It targeted infrastructure during a sensitive time (winter). It intended to destroy critical systems. It targeted a NATO member.

Where does the escalation go from here? That's the scary question.

One scenario: cyberattacks become a standard tool of conventional military operations. When Russia wants to prepare for a military operation, it first disables communications and power through cyberattacks, then moves military forces. That would be a major escalation.

Another scenario: cyberattacks on infrastructure become more common and more destructive, until multiple countries experience infrastructure failures simultaneously. Imagine a coordinated attack on power grids in multiple NATO countries. That could approach the threshold of collective defense and trigger military responses.

A third scenario: attribution becomes so difficult that countries can't agree on who attacked them, making coordinated response impossible. Cyberattacks become part of the background noise of international relations, without clear attribution or response.

None of these scenarios is inevitable. But the Poland attack shows that the technology exists, the expertise exists, and the intent exists. The only question is how the international community will respond.

Defensive Lessons: What Energy Infrastructure Operators Must Do Now

The Poland attack provides a masterclass in what can go wrong and what can go right. For energy infrastructure operators and security leaders, it's a wake-up call.

First, detection matters. Poland detected the attack quickly. That early detection allowed a coordinated response. Invest in intrusion detection systems, security monitoring, and incident response capabilities.

Second, segmentation is critical. If your entire power grid is one network, one compromised system can lead to cascading failures. Segment your network so that operational systems are isolated from information systems. Use air-gapped networks for critical control systems. Make lateral movement difficult.

Third, backup and recovery plans are essential. Even if malware reaches your systems, can you recover? Do you have offline backups? Do you have alternative operational procedures for running the system manually? Can you isolate the malware and restore from clean backups?

Fourth, training matters. Cyberattacks often start with phishing or social engineering. A trained employee who notices a suspicious email can prevent the entire attack chain. Invest in security training for your staff.

Fifth, threat intelligence sharing is valuable. Organizations that share information about attacks are collectively stronger. Work with government agencies, industry peers, and security researchers. The attack that happened to Ukraine can teach you lessons.

Sixth, assume breach. Even if you have the best defenses, assume that an attacker will eventually penetrate your network. Design your systems so that even if they're breached, the damage is limited.

Sandworm's cyberattack activities have increased over the years, with a notable rise in the number of major attacks from 2017 to 2020. (Estimated data)

The Intelligence Implications: What This Tells Us About Russian Capabilities

Cybersecurity professionals and intelligence analysts can draw several conclusions from the Poland attack.

First, Russia's cyber capabilities are sophisticated. Building custom malware, conducting reconnaissance on target infrastructure, and coordinating the attack requires resources and expertise. This isn't a random hack. This is a well-resourced operation.

Second, Russia has the ability to reach critical infrastructure in neighboring countries. They know who to target, how to reach them, and how to exploit vulnerabilities. Their intelligence on Poland's energy sector is detailed.

Third, Russia is willing to use its cyber capabilities against NATO members. This is a strategic decision. It suggests that either Russia believes the consequences will be limited, or Russia is willing to accept the consequences to achieve political objectives.

Fourth, Russia has learned from past operations. The techniques used against Ukraine are refined and applied elsewhere. The malware is purpose-built. The operational planning is deliberate.

For intelligence communities analyzing this attack, the questions are: How far will Russia escalate? Are cyberattacks against NATO infrastructure likely to increase? Is this a one-off incident or the beginning of a campaign?

The answers depend partly on how other countries respond. If the response is minimal (diplomatic protests but no real consequences), Russia learns that it can continue without risk. If the response is significant, Russia learns that there are boundaries.

Supply Chain Vulnerabilities: How Attackers Get In

The Poland attack details aren't fully public, but based on similar operations, it likely involved supply chain compromises.

Energy companies don't build their infrastructure from scratch. They buy equipment from vendors. They use software from software companies. They contract with integrators and security firms. Each vendor, each software package, each contractor is a potential entry point for an attacker.

In the 2015 Ukraine attack, one theory suggests that the attackers compromised a software update from an energy company's vendor, embedding malware in the software that the company trusted. When the energy company installed the update, they installed the malware.

This is a sophisticated attack vector because the victim trusted the vendor. The software came from a known source. It appeared legitimate. But it contained malware.

For energy companies and critical infrastructure operators, this means you can't just trust vendors. You need to:

- Validate software before deploying it

- Verify digital signatures of updates

- Implement application whitelisting so only approved software runs

- Monitor your supply chain for compromises

- Have security clauses in vendor contracts

- Conduct regular audits of installed software and configurations

The supply chain is both a strength and a vulnerability of modern infrastructure. The strength is that you can leverage other organizations' expertise. The vulnerability is that you're trusting organizations you don't fully control.

International Response: Sanctions, Attribution, and Deterrence

Following confirmed cyberattacks by nation-states, some countries impose sanctions. But sanctioning for a cyberattack is complicated.

First, there's the attribution problem. How confident do you need to be before you sanction? The Poland attack was attributed with "medium confidence." Is that enough? Some countries would say yes. Others would require higher certainty.

Second, there's the response calibration problem. How severe should sanctions be for a cyberattack that was successfully defended? For one that caused damage? For one that caused deaths?

Third, there's the effectiveness question. Do sanctions actually deter future cyberattacks? Russia has been sanctioned for various cyber operations, yet the operations continue. It's not clear that economic sanctions are an effective deterrent for state-sponsored cyber operations.

There are other response options: cyber retaliation (hacking back), military responses (conventional military action), diplomatic isolation, or technology restrictions (denying access to specific technologies). Each has advantages and disadvantages.

The Poland incident will likely lead to discussions within NATO about how to respond to cyberattacks on member states. Those discussions are happening in classified settings, so we won't see the conclusions publicly. But expect policy changes, possibly increased military presence in Eastern Europe, and definitely increased cyber defense investments.

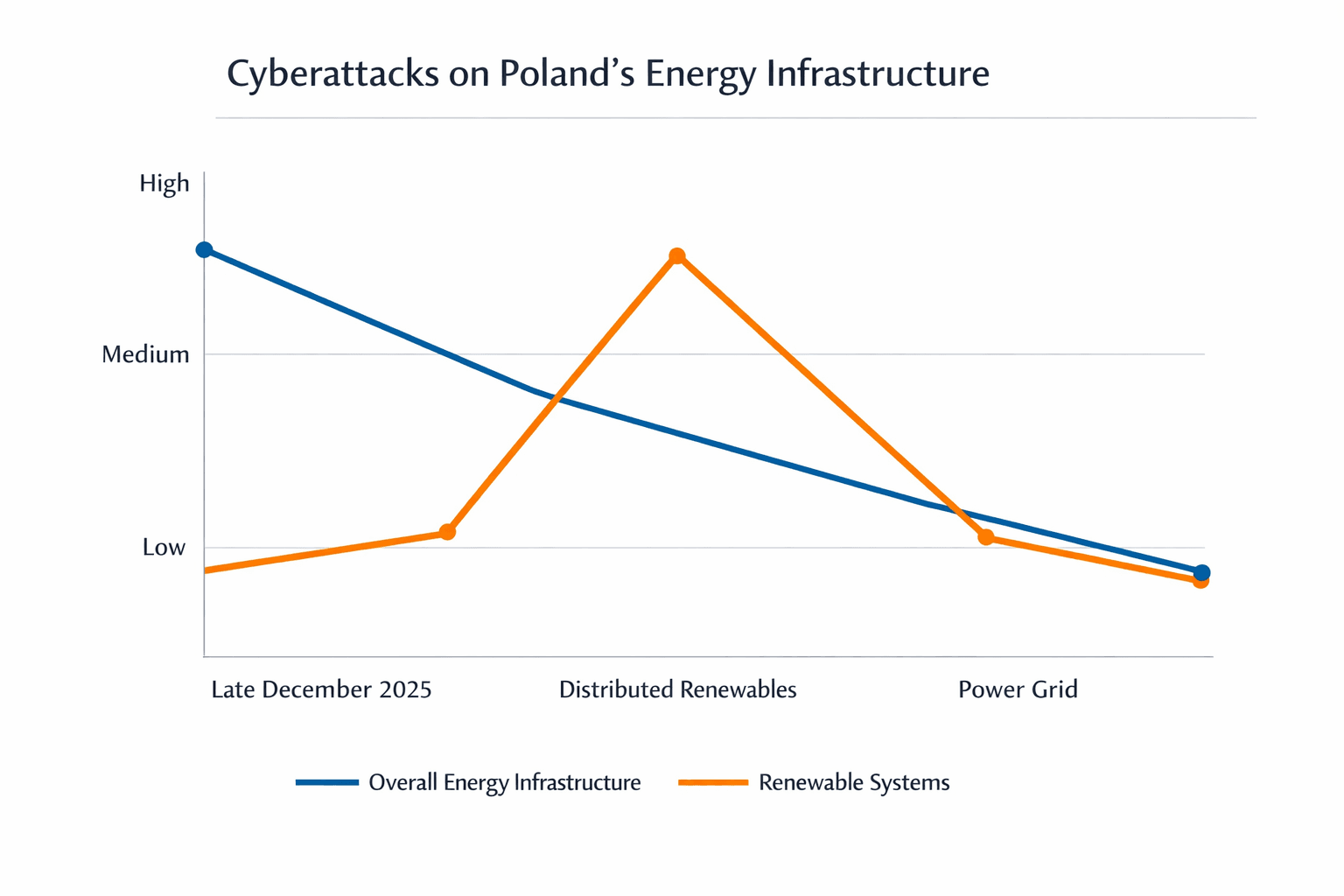

Ransomware is primarily used for financial gain, while wiper malware is used for political messaging and demonstrating capability. (Estimated data)

The Future of Energy Grid Security: Toward Resilience

The lesson from Poland and Ukraine is that energy grids need to be resilient. Resilience means: attacks might happen, but you survive them. You detect them quickly. You recover from them. You continue to provide essential services.

This requires a shift in how we think about security. Traditional security was about prevention: building walls so attackers can't get in. Resilience is about survival: assuming attackers will get in, but making sure you can deal with it.

For energy companies, resilience means:

- Redundancy: Multiple power plants, multiple distribution routes, so that if one fails, others compensate

- Monitoring: Continuous visibility into what's happening on your systems so you detect attacks quickly

- Automation: Systems that can respond to attacks without human intervention

- Restoration: The ability to quickly restore service if systems are compromised

- Adaptation: Learning from attacks and updating defenses accordingly

Some countries are investing heavily in this. The U. S. has programs to upgrade power grid resilience. Europe is investing in cyber defenses for critical infrastructure. But the pace of investment is slow compared to the pace of cyber threat evolution.

The Poland attack should accelerate that investment. It proved that the threat is real, that nation-states will use cyber operations against critical infrastructure, and that the consequences can be severe.

Lessons for Other Critical Infrastructure Sectors

While this incident targeted energy infrastructure, the lessons apply to water systems, transportation, healthcare, communications, and other critical infrastructure.

All of these sectors have similar vulnerabilities: aging systems, connectivity for operational efficiency, supplier dependencies, and limited security budgets. All of them could be targets for similar attacks.

Water systems are attractive targets because attacking water supplies can affect large populations. Transportation systems (air traffic control, rail networks) are attractive because disrupting them can cause cascading economic impacts. Healthcare systems are attractive because disrupting them puts lives at risk.

Yet most of these sectors are less prepared for cyberattacks than the energy sector. Energy companies have benefited from years of increased focus on cyber resilience. Water systems, transportation systems, and healthcare systems are playing catch-up.

The Poland attack should prompt a reassessment of cyber risk across all critical infrastructure. Regulators should mandate security standards. Organizations should invest in detection and response capabilities. Governments should provide funding and resources.

Because the next attack might not be on energy. It might be on something else. And the consequences could be severe.

The Geopolitical Context: Why Russia Attacked Poland Now

Timing in geopolitics is rarely coincidental. Russia chose to attack Poland in late December 2025, exactly 10 years after the Ukraine attack. Why?

Possible explanations:

Testing NATO readiness: NATO was founded as a collective defense alliance. If Russia can attack a NATO member's infrastructure and survive the consequences, it suggests NATO's deterrent is weak. An attack that's successfully defended still proves that Russia can reach NATO infrastructure.

Escalating pressure: Poland has been a strong NATO ally and a supporter of Ukraine. Attacking Polish infrastructure is a way to pressure the country, to make clear that there are costs to NATO alignment.

Demonstrating capability: For domestic audiences in Russia, the attack demonstrates that Russia has world-class cyber capabilities. It's a show of strength.

Probing defenses: Every attack provides intelligence about how NATO countries defend their infrastructure. What worked? What didn't? Where are the gaps? That intelligence is valuable for planning future operations.

Escalation in the Ukraine conflict: Russia might be testing whether escalation in cyberattacks will prompt military escalation from NATO. Or, alternatively, demonstrating that cyberattacks short of military action are tolerated.

The geopolitical context matters because it suggests this isn't a one-off incident. This is part of a broader campaign to test, probe, and gradually escalate cyber operations against NATO.

When Attacks Fail: The Importance of Defensive Success

We focus a lot on attacks that succeed. But this case is important because of what didn't happen. The attack failed. The defenses held. People stayed warm. Lights stayed on.

That might not sound dramatic, but it's crucial. If the attack had succeeded, we'd be reading different headlines: "Half a million Poles lose power in winter cyberattack," "Hospitals go offline due to cyber warfare," "NATO member city left in dark."

Instead, we're reading: "Attack was detected and stopped." That's a win. That's proof that defense works. That's evidence that investing in security pays off.

For other critical infrastructure operators struggling to justify cybersecurity budgets, the Poland incident is powerful evidence. Yes, it costs money. Yes, it's an ongoing investment. But when cyberattacks do come, that investment prevents catastrophe.

Poland's success also provides a blueprint. Here's what worked:

- Investment in detection capabilities

- Training and awareness programs

- Collaboration with international partners

- Segmented networks that limit damage

- Incident response plans

- Quick decision-making once the attack was detected

Other countries and organizations can study Poland's approach and implement similar defenses.

What We Still Don't Know: Open Questions

The full technical details of the Poland attack haven't been released publicly. Neither have details about how the attack was detected or stopped. That's understandable for operational security reasons, but it means we're working with incomplete information.

Open questions include:

How did the attackers initially gain access? Phishing? A vulnerable server? A compromised supplier? A former employee?

How much progress did they make inside the network before being detected? Were they stopped at the perimeter, or did they penetrate deep and then get caught?

What other tools and techniques did they use? The article mentions Dyno Wiper, but attackers typically use multiple tools. What else was deployed?

Were other Polish targets outside of energy attacked? Or was energy the exclusive focus?

What intelligence was the attackers seeking? Were they trying to gather information, or was destruction the only goal?

How did Poland detect the attack? Did they notice unusual network traffic? Did they respond to an alert? Did they see actual data destruction?

These details matter for other organizations trying to learn from the incident. As more information becomes available (through security conferences, research papers, or government briefings), the picture will become clearer.

The Role of Information Sharing: Collaborative Defense

One of the silver linings of the Poland incident is that it should prompt increased information sharing about cyberattacks.

When Ukraine experienced attacks in 2015 and 2016, security researchers from multiple countries studied the attacks and published findings. Those findings helped other countries understand Sandworm's tactics and prepare defenses. Countries didn't have to learn through painful experience. They could learn from Ukraine's experience.

The same should happen with the Poland attack. As soon as security researchers have detailed information, they should publish it (without revealing sensitive operational details). As soon as Polish authorities understand the attack, they should brief international partners.

Information sharing is sometimes complicated by security concerns, classified information, and competitive dynamics. But the benefits of shared defense outweigh the costs. An attack that's analyzed and its details shared prevents the same attack from succeeding elsewhere.

International organizations like NATO, Interpol, and international cybersecurity forums should facilitate this sharing. Organizations like CISA (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency) in the U. S. should coordinate information flows.

The goal is to create a situation where when one country is attacked, all countries benefit from understanding that attack and improving their defenses. That's collaborative cyber defense.

Preparing for the Next Attack: A Strategic Outlook

The Poland incident is unlikely to be the last attack on European critical infrastructure. More attacks should be expected.

Futuro attacks might:

- Target multiple infrastructure sectors simultaneously (power, water, communications)

- Coincide with military exercises or political crises

- Use more sophisticated malware with advanced evasion techniques

- Target specific facilities to cause maximum harm (hospitals, water treatment plants)

- Include a disinformation component (false claims about what happened to sow confusion)

To prepare, countries and organizations should:

Invest in cyber defense: Hiring skilled defenders, deploying detection tools, maintaining infrastructure.

Develop incident response procedures: How will you respond when attacked? Who decides what? What are your escalation procedures?

Conduct tabletop exercises: Simulate attacks. Practice your response. Identify gaps before you're under actual attack.

Establish mutual aid agreements: If one facility is compromised, can others provide support? Can they redirect services?

Build relationships with government agencies: Establish clear lines of communication so information flows quickly.

Stay updated on threat intelligence: Know what attackers are targeting, what techniques they're using, and what defenses are effective.

The good news is that defenses are available and, as Poland demonstrated, they work. The challenge is implementing them consistently and adapting them as threats evolve.

FAQ

What exactly is destructive malware like Dyno Wiper?

Destructive malware, or "wiper" malware, is specifically designed to irreversibly destroy data and disable computers rather than steal information or extort money. Unlike ransomware that encrypts files for a ransom demand, wiper malware renders systems completely unusable by overwriting or deleting critical data. The attacker has no way to restore the system or profit from it, making this type of malware a tool for causing maximum damage rather than for financial gain. This is why wiper attacks are often attributed to state actors rather than criminal groups.

How did Poland detect and stop the cyberattack?

While the exact technical details haven't been publicly disclosed for operational security reasons, Poland likely detected the attack through intrusion detection systems monitoring for suspicious network activity, particularly any signs of command and control communications with the malware. Once detected, Polish cybersecurity teams isolated affected systems, prevented lateral movement through the network, and disconnected critical infrastructure from the internet where possible. The key was that Poland had invested in monitoring and detection capabilities following lessons learned from Ukraine's experiences, allowing them to catch the attack before it could reach and destroy critical operational systems.

Why is Sandworm considered a Russian government operation?

Sandworm is assessed to be a unit within Russia's GRU (military intelligence agency) based on multiple factors: the sophistication and resources required for their operations, their targeting patterns that align with Russian geopolitical interests, the timing of attacks that coincides with Russian military operations or political events, and attribution from multiple security researchers and government agencies. The group's access to zero-day vulnerabilities and custom malware suggests state-level resources rather than independent hackers. Additionally, their operations have been consistent and coordinated in ways that suggest institutional support, rather than the sporadic nature of criminal hacking groups.

What would have happened if the Poland attack had succeeded?

Had the attack successfully destroyed critical systems at Poland's heat and power plants, the cascade effects could have been catastrophic. As many as half a million homes could have lost both electricity and heating in the middle of winter. This would have disrupted hospitals, water treatment plants, and transportation systems. Based on the 2015 Ukraine attack that disabled similar infrastructure, people could have died from exposure, lack of heating during winter, hospital failures, and infrastructure failures. The economic damage would have been significant, affecting not just households but also businesses that depend on power. This illustrates why critical infrastructure cyberattacks are considered acts of war rather than ordinary crimes.

Could this type of attack happen in other countries?

Absolutely. While the Poland attack targeted specific facilities, the same vulnerabilities and attack methods exist in other countries' energy infrastructure, particularly in Europe and NATO allies. Any country with interconnected power systems, aging operational technology, supply chain dependencies, and connectivity for operational efficiency is potentially vulnerable. The United States, Germany, France, and other major economies with complex energy infrastructure could face similar attacks. In fact, there's evidence that Sandworm and other Russian cyber units have conducted reconnaissance on critical infrastructure in multiple countries, suggesting Poland may not be an isolated target but rather part of a broader reconnaissance and testing campaign.

What can individual citizens do to prepare for potential cyberattacks on infrastructure?

Individual preparation includes having emergency supplies like bottled water, non-perishable food, flashlights, batteries, and first aid kits in case infrastructure fails for extended periods. Keep devices charged, maintain backup communication methods (like mobile phones with offline maps), know how to manually operate essential systems if needed, and stay informed through news sources about cybersecurity risks. On a policy level, advocate for critical infrastructure investment and support politicians who prioritize cybersecurity funding. Communities can develop mutual aid plans with neighbors in case of extended outages. Having these preparations isn't paranoia; it's practical risk management given the documented threat of cyberattacks on infrastructure.

How does the Poland incident compare to previous cyberattacks on infrastructure?

The Poland attack is significant because it represents an escalation in several ways: it targeted a NATO member rather than a non-aligned country, it used destructive malware rather than disruption tools, it was timed symbolically (exactly 10 years after the Ukraine 2015 attack), and it demonstrated that Russia's capabilities have advanced significantly since previous operations. The 2015 Ukraine attack successfully caused widespread power outages affecting 230,000 homes. The 2016 Ukraine attack struck again, suggesting that Ukraine's defenses had improved. The Poland attack, which failed to cause disruption despite reaching the infrastructure, suggests that defensive capabilities in NATO countries may be more advanced than in Ukraine. However, the attempt itself is alarming because it proves Russia is willing to attack NATO members and that their capabilities are sophisticated.

What role did NATO play in Poland's defense?

While NATO itself doesn't directly operate Poland's energy infrastructure, NATO members have been sharing threat intelligence and best practices for defending critical infrastructure since the Ukraine attacks. Poland benefits from NATO intelligence sharing about Russian cyber threats, coordination with U. S. Cyber Command and other allied cyber defense centers, and access to NATO-wide incident response networks. NATO's collective defense commitment (Article 5) also serves as a deterrent. However, the actual defense of Poland's infrastructure was conducted by Polish cybersecurity professionals and government agencies. NATO's role was more strategic than tactical, providing the framework for cooperation and intelligence sharing that informed Poland's defensive posture.

Could cyberattacks trigger a military response from NATO?

NATO recognizes that cyberattacks can trigger Article 5 (collective defense), but only if the attack is severe enough to constitute an "armed attack." The threshold is intentionally high because cyberattacks exist in a gray zone between espionage and war. A successful destructive attack on critical infrastructure that caused civilian deaths would likely cross this threshold. However, unsuccessful attacks even if detected, may not meet the bar for collective military response. Instead, NATO would likely respond with sanctions, cyber retaliation, military posturing, or intelligence operations. The challenge is that cyber deterrence is less clear than traditional military deterrence, so it's uncertain whether military responses would actually prevent future cyberattacks or escalate the situation further.

What are the long-term implications of this attack?

Long-term implications include: accelerated investment in cyber defense for critical infrastructure across NATO; increased focus on infrastructure resilience and redundancy; potential changes to the rules of engagement for cyber operations; closer coordination between government and private sector on cybersecurity; investment in training and hiring cyber defense professionals; upgrades to aging operational technology systems; and possibly changes to international law regarding cyberattacks on civilian infrastructure. The incident also serves as a wake-up call that the international system currently has limited mechanisms for deterring or punishing state-sponsored cyberattacks, suggesting that future attacks may continue unless stronger deterrence frameworks are established through international agreements and coordinated responses.

The Bottom Line

The attempted cyberattack on Poland's energy infrastructure in late December 2025 represents a dangerous escalation in cyber warfare. Russian military intelligence, through the Sandworm unit, deployed sophisticated destructive malware with the explicit goal of disabling critical infrastructure and potentially causing harm to civilians during winter.

But the attack failed. Poland's defenses held. This success offers lessons for every country and every critical infrastructure operator: investment in cybersecurity works. Detection capabilities work. Coordination and preparation work.

The incident also serves as a warning. It proves that nation-states will target critical infrastructure. It proves that the capability exists. And it proves that the geopolitical tensions underlying these operations are real and escalating.

As we move forward, the key question isn't whether more attacks will come. They will. The question is whether countries and organizations will invest in the defenses necessary to survive them. Poland showed it's possible. Other countries need to follow that example before they face their own moment of crisis.

The power grid attack that Poland prevented from happening is a roadmap for what happens next if we don't take cybersecurity seriously. It's a fire alarm. The question is whether we'll respond before the actual fire arrives.

Key Takeaways

- Russian military intelligence (Sandworm) attempted to destroy Poland's power infrastructure using custom destructive malware (DynoWiper) on December 29-30, 2025

- The attack could have left half a million homes without heat during winter, but Poland's cyber defenses successfully detected and stopped it

- This represents an escalation from previous cyberattacks, targeting a NATO member with destructive intent rather than espionage or extortion

- Poland's successful defense demonstrates that investment in intrusion detection, network segmentation, and security preparedness actually works to prevent catastrophic infrastructure damage

- Similar vulnerabilities exist in critical infrastructure worldwide, making this incident a blueprint for understanding threats to power grids, water systems, and transportation networks globally

Related Articles

- Federal Cybersecurity Crisis: Why Government Digital Defense Is Collapsing [2025]

- LinkedIn Phishing Scam Targeting Executives: How to Protect Yourself [2025]

- LastPass Phishing Scam: How to Spot Fake Support Messages [2025]

- Most Spoofed Brands in Phishing Scams [2025]

- Jen Easterly Leads RSA Conference Into AI Security Era [2025]

- Why Your Backups Aren't Actually Backups: OT Recovery Reality [2025]

![Russian Hackers Targeted Poland's Power Grid: What Happened [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/russian-hackers-targeted-poland-s-power-grid-what-happened-2/image-1-1769200668516.jpg)