The Real Problem With Ring's New Direction

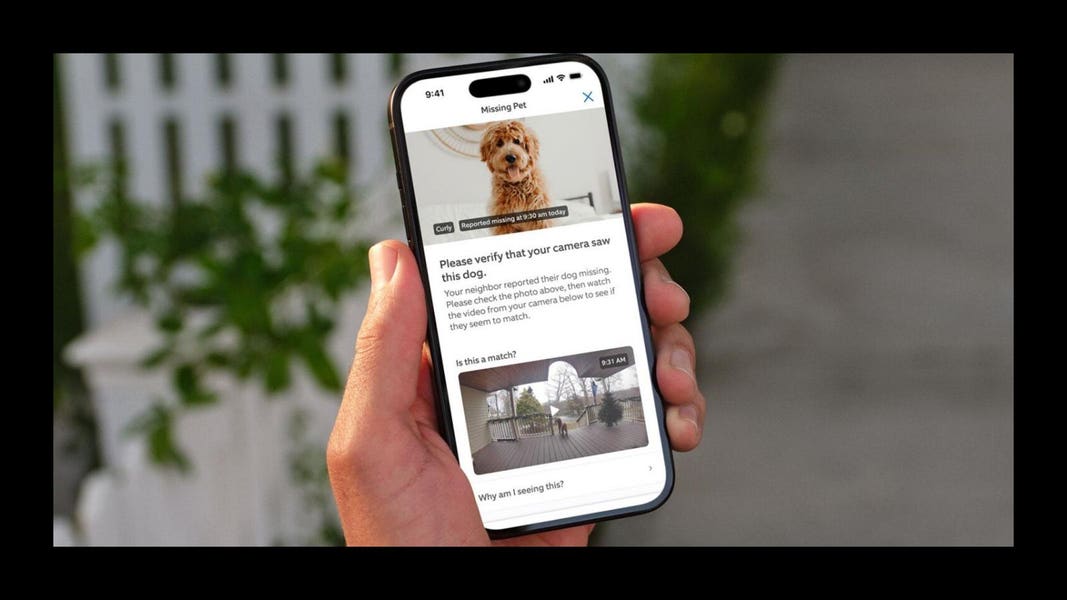

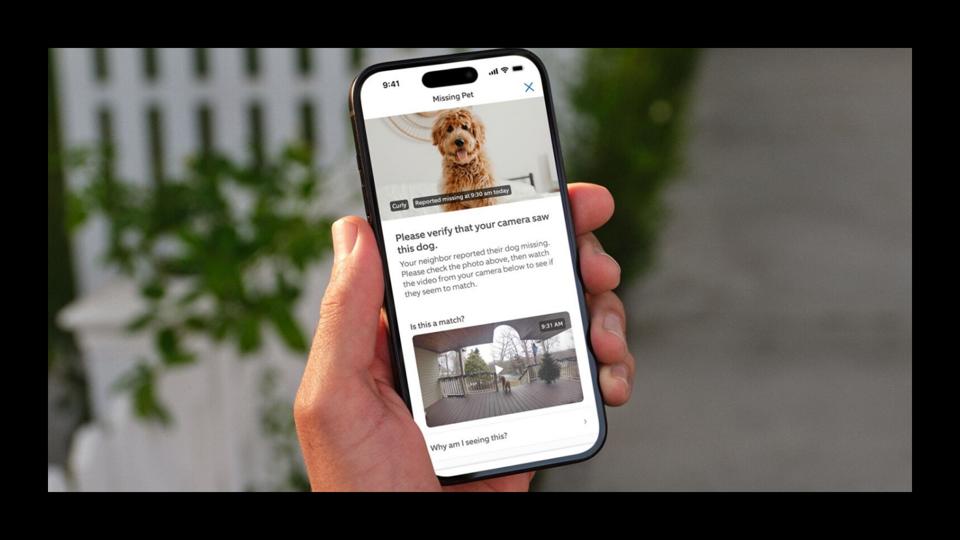

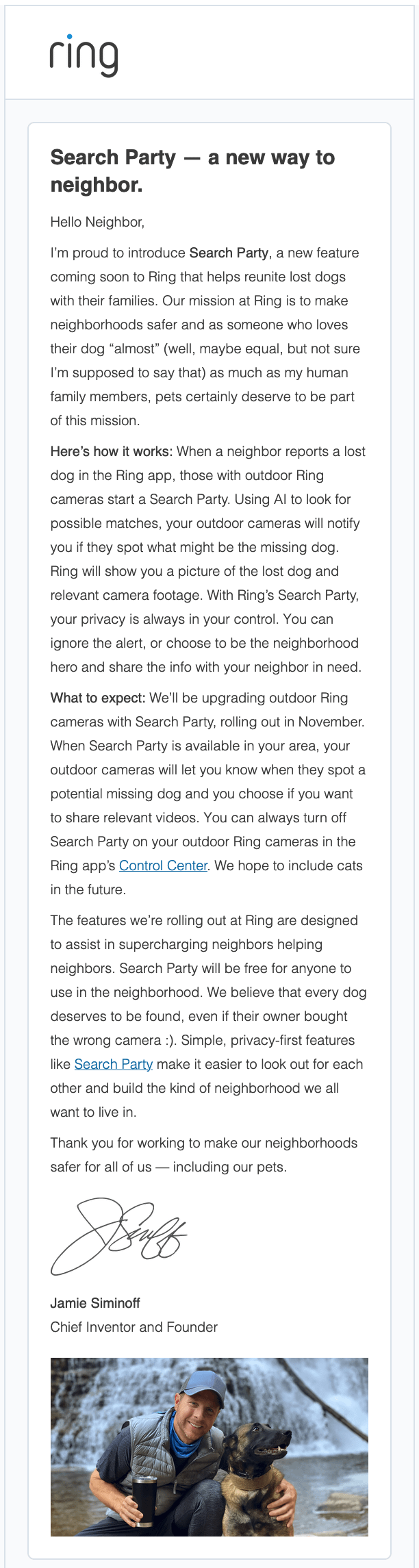

Ring isn't just selling doorbell cameras anymore. What started as a way to catch package thieves has evolved into something far more complicated: a networked surveillance system with the power to track people's movements across entire neighborhoods, powered by AI that can search video footage by description rather than date and time. According to GeekWire, the company's new Search Party feature triggered a backlash after a Super Bowl ad showed blue rings radiating from suburban homes, instantly conjuring images of panopticon-style monitoring. The ad wasn't subtle. It was meant to show how Ring's cameras could help find a lost dog, but what viewers saw was different: a visual metaphor for comprehensive neighborhood surveillance.

Ring founder Jamie Siminoff went on an explanation tour after the backlash. In interviews with major outlets, he acknowledged the ad was poorly timed, promised fewer maps in future advertising, and repeated the company's core message: more cameras mean safer neighborhoods. He insisted Ring isn't building mass surveillance infrastructure, that privacy protections are robust, and that users control their own footage. However, as noted by The New York Times, he never really answered the hard questions. And that's the problem.

The backlash wasn't about maps. It wasn't about bad ad design. It was about the fundamental reality that Ring has quietly assembled the infrastructure for something that looks, sounds, and acts like mass surveillance, whether the company intends it that way or not. And Siminoff's response has been to double down on expansion rather than address the legitimate concerns.

Why Search Party Changes Everything

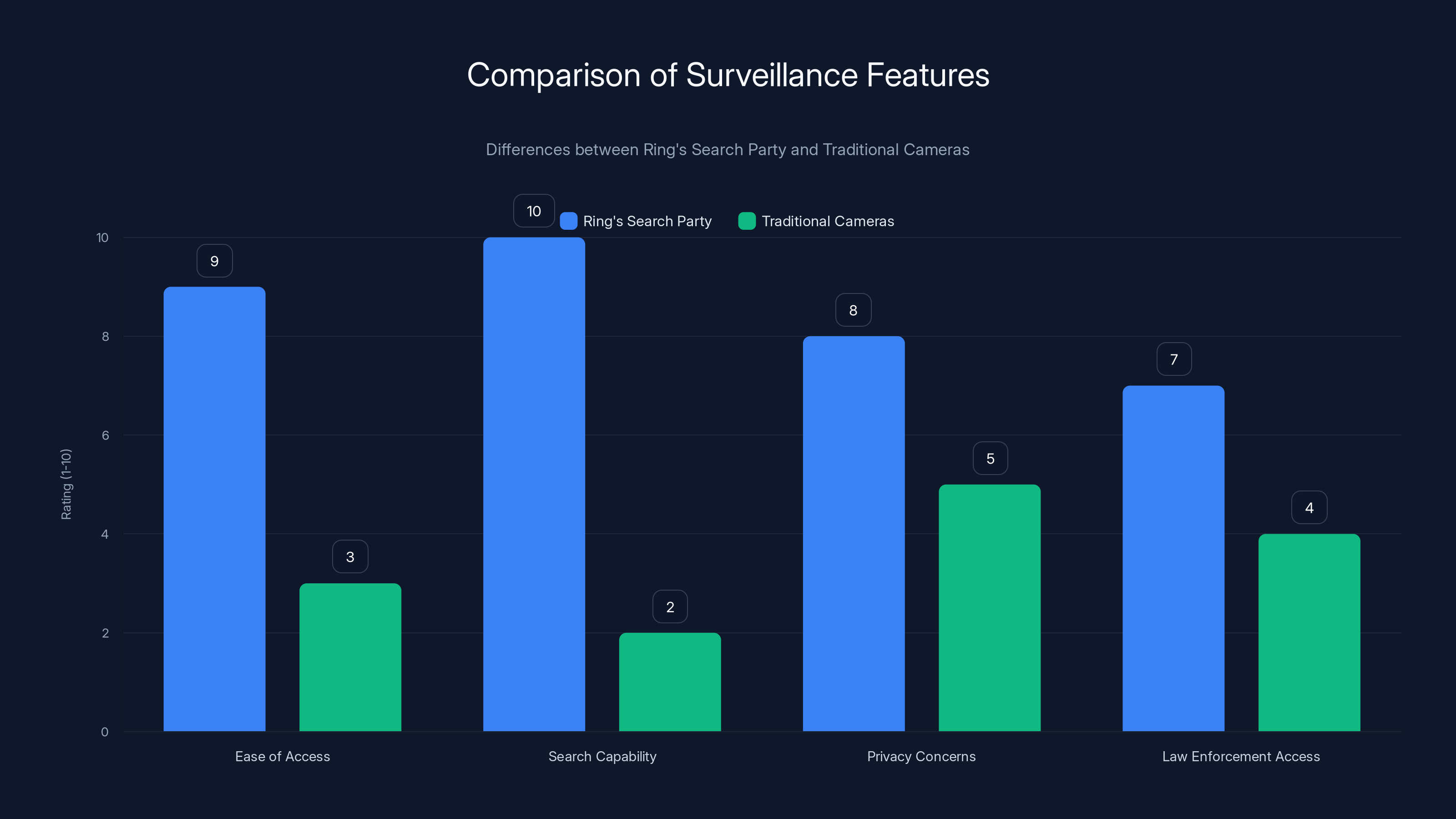

Before Search Party, Ring footage was reactive. You had to know approximately when something happened, then scroll through hours of video. It was tedious, which created a natural friction. If you wanted to find footage of someone breaking into your car, you'd need to remember roughly when it happened and watch the recordings around that time.

Search Party removes that friction entirely. Now you can type "person in a red jacket" or "bike" or "person looking in windows," and AI will search through all the video in the Ring network it has access to. You don't need to know when something happened. You don't even need to know exactly what you're looking for. The AI interprets your description and finds matches. This is fundamentally different. It transforms Ring cameras from a system designed to record and store video (which is already intrusive) into a searchable database where you can ask questions about who moved where and when. The difference between recording video and being able to query video is enormous.

For law enforcement, the implications are staggering. If a police officer has access to this system through Ring's Community Requests program, they can search for people based on appearance. They can find everyone wearing a certain color on a given day. They can track movements across multiple properties. They don't need a warrant or specific evidence of a crime. They just need to describe what they're looking for, as highlighted by Consumer Reports.

The company says it requires law enforcement to go through formal requests and that it logs all access. But historical precedent suggests those guardrails erode quickly. Police departments have repeatedly exceeded the scope of surveillance programs they claimed would be limited. They've used tools designed for one purpose to accomplish another. They've shared data with agencies like ICE and CBP far more broadly than the public understood, as reported by The New Republic.

Ring already cancelled its partnership with Flock Safety, a license plate recognition company that law enforcement used to share data with immigration authorities. But the company still has Community Requests, which is potentially more powerful. And it's expanding its partnership with Axon, a company best known for Tasers that's now trying to be the enterprise software backbone for law enforcement agencies nationwide, as noted by Mezha.

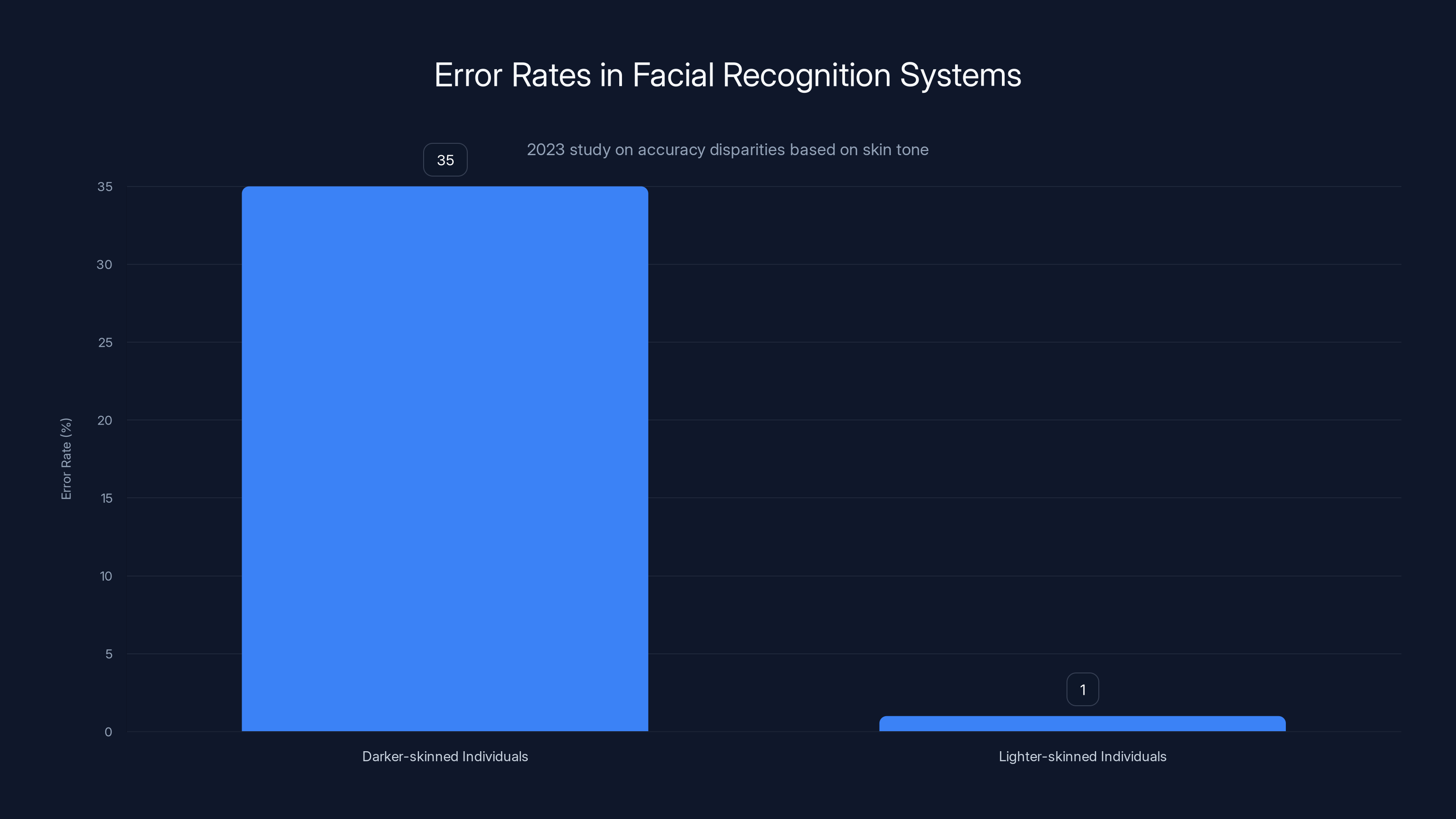

Facial recognition systems show a significant disparity in error rates, with up to 35% for darker-skinned individuals compared to less than 1% for lighter-skinned individuals.

The Default Setting Problem

Here's something that reveals Ring's actual priorities: the company turned Search Party on by default. When Ring introduced this feature, it could have made it opt-in, which would have respected user choice and acknowledged the sensitive nature of what was being created. It didn't. Instead, it enabled Search Party automatically for everyone, which meant that from day one, users' video was being indexed and searchable without explicit consent. Siminoff told The New York Times that he understands people's concerns and that Ring has robust privacy protections. But he also told The Times that he believes most people want more cameras and more video, even if they say otherwise. This is the kind of claim that reveals a fundamental disconnect. He's telling people that they're wrong about their own preferences while simultaneously designing systems that bypass their ability to choose.

When Ring turned Search Party on by default, it demonstrated that the company has complete control over how aggressively it deploys this technology. Users can opt out, sure, but most won't. Most people don't change default settings. Most people don't know what Search Party even is. By the time they do, their footage has already been indexed.

The argument that users have control because they can opt out puts the burden entirely on individuals while the company enjoys the benefits of a vast searchable video database. It's a clever inversion of responsibility, but it doesn't change what's actually happening. There's also no guarantee that default settings will remain this way. Ring has changed its privacy policies and feature availability multiple times. What's opt-in today could become opt-out tomorrow. What's opt-out could become mandatory as the company integrates further with law enforcement systems, as discussed in Consumer Reports.

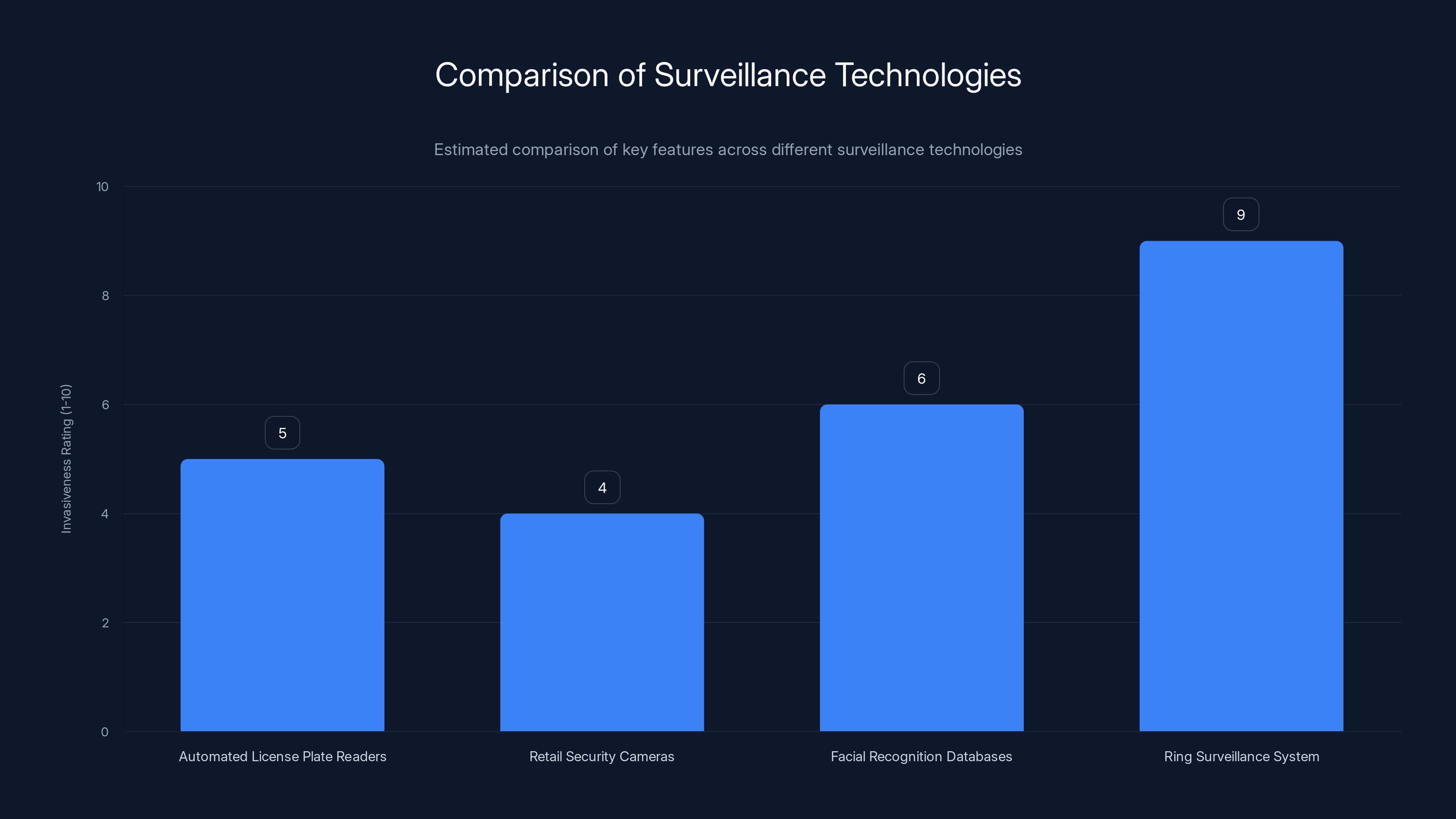

Ring's surveillance system is rated as the most invasive due to its comprehensive, continuous, and integrated features. Estimated data.

The Expansion Roadmap Nobody's Talking About

Siminoff confirmed to The New York Times that Ring is actively expanding Search Party. The company plans to add cat detection to its capabilities. Then what? Siminoff didn't say, and more importantly, nobody asked follow-up questions about where Ring plans to draw the line.

Will Search Party eventually search for people's faces? Ring hasn't committed to not doing this. Facial recognition has massive implications for civil liberties and policing. It enables tracking people across entire cities. It enables matching people against watchlists. It enables identifying protesters and attendees at political events. It's a tool that fundamentally changes the power dynamic between individuals and institutions.

Will Search Party eventually work across multiple neighborhoods? Right now it works within a user's own neighborhood, but Ring is constantly expanding. The company's stated goal is to make communities safer, and expanding geographic reach would logically be the next step. A searchable database that covers an entire city would be qualitatively more powerful than one that covers a neighborhood.

Will third parties eventually be able to access Search Party? Ring's Community Requests program already allows police access. What about insurance companies investigating claims? What about private investigators? What about people with court orders? What about data brokers?

Ring hasn't said. And Siminoff isn't addressing these questions. Instead, he's out explaining why maps in advertisements were a mistake while the actual infrastructure for something much more significant continues to expand in the background.

People in the Video Don't Have a Choice

One of the most overlooked aspects of Ring's expansion is this: the people being filmed didn't ask to be filmed. If you live in a neighborhood with Ring cameras, your movements are being recorded whether you consented to it or not. If someone's Ring camera points at the street, it's capturing you walking to your car. It's capturing you jogging. It's capturing you leaving your house. That footage exists without your permission, and now it's searchable.

This is fundamentally different from ring cameras pointing at someone's own property. It's different from recording your own front yard. When cameras pointed by private citizens capture public spaces, we've collectively agreed that's acceptable. But when those recordings are aggregated into a searchable, queryable database, something important changes.

You can tell Ring to delete its footage of you, presumably, if you know it exists and if Ring provides that functionality. But you can't prevent the recording from happening in the first place. You can't opt out of a surveillance system you didn't sign up for. You can't control how the data is used or who can access it.

And if law enforcement requests footage of you based on a Search Party query, you may never know it happened. You might never find out that police searched for "person in blue jacket" and found you, or that they identified you from a recording of a public street.

Ring has created a system where people's movements can be tracked and searched without their knowledge or consent. Siminoff talks about the value of video evidence and how footage can tell stories that wouldn't be told otherwise. That's true. But it's also true that the same infrastructure enables tracking, surveillance, and control in ways that should concern anyone who values privacy and freedom of movement.

Ring's Search Party significantly enhances search capability and ease of access compared to traditional cameras, but raises more privacy concerns and allows greater law enforcement access. Estimated data.

The Law Enforcement Connection Nobody's Addressing

Ring's Community Requests program is positioned as a way for users to voluntarily help local police by sharing video footage. Users initiate the request, they decide what to share, they maintain control. That's the company's narrative.

But Search Party changes this dynamic. Now police don't need to ask users to share footage. They can search directly through the Ring network for whatever they're looking for. If a police officer has access to Search Party (through a formal request or an informal arrangement), they can find footage without the knowledge or permission of the people in it.

Ring says it requires formal requests and logs all access. But the company has strong incentives to make police happy. Law enforcement adoption drives customer interest, which drives network effects, which makes Search Party more valuable. There's a misalignment of incentives here that Ring isn't acknowledging.

Historically, law enforcement agencies have been remarkably creative at using technology in ways that exceed its original scope. Stingray devices, originally designed to locate specific suspects, became tools for dragnet surveillance. Cell-site simulators were used to track everyone in an area. Automated license plate readers, designed to find stolen cars, became tools for tracking the movements of civil rights protesters.

Ring says it's different. The company says it has safeguards. But those safeguards exist only as long as Ring is willing to enforce them, and Ring's business incentives are aligned with expanding law enforcement access, not restricting it.

The cancelled Flock Safety partnership showed that Ring can respond to public pressure. But that partnership was explicitly designed to share footage with ICE, which triggered massive backlash. Community Requests and Search Party operate with less visibility. Most people don't know they exist. There's less public pressure. There's less reason for Ring to restrict their use.

The Technical Problem: AI Hallucination and Misidentification

Search Party relies on AI to identify objects and people in video. And here's where things get really problematic: AI makes mistakes, sometimes confidently.

Computer vision systems frequently misidentify people. They struggle with different lighting conditions, camera angles, partial views, and unusual clothing. More importantly, they make systematic errors based on race, gender, and age. Research has repeatedly shown that facial recognition systems are significantly more accurate at identifying white men than anyone else.

Now imagine a police officer using Search Party to find a suspect. They describe someone as "tall male, dark hair, red jacket." The system returns results. Some are correct matches. Some are false positives. Some are people who have dark hair and a red jacket but are completely unrelated to whatever the officer is investigating.

In the best case, the officer realizes these are just initial leads and investigates further. In the worst case, an innocent person becomes a suspect based on an AI system's hallucination. Search Party doesn't identify people by name. It just finds people who match a description. If the AI makes a mistake, innocent people can be caught in the net.

Ring hasn't published studies about the accuracy of Search Party. The company hasn't tested how often the system makes mistakes or what kinds of misidentifications are most common. It's rolled out a powerful tool that can affect people's lives without publishing reliability data, as discussed in BBC News.

This is a legitimately hard problem. AI systems for computer vision are improving, but they're not perfect and probably won't be for years. But the solution isn't to deploy an imperfect system without transparency about its limitations. The solution is to acknowledge those limitations publicly, publish accuracy data, and require human review before anyone's life is affected by the system's findings.

Ring hasn't done any of this.

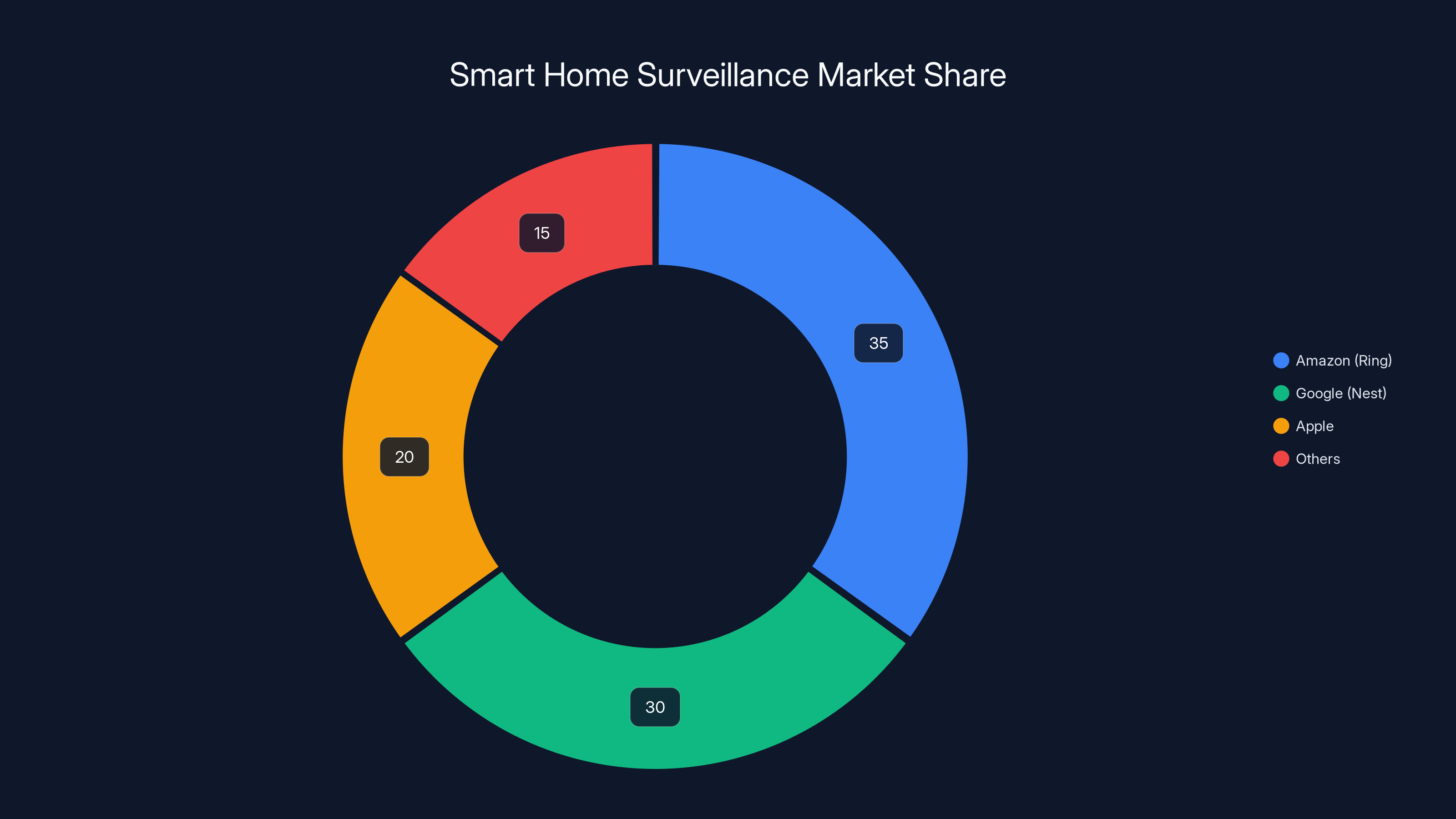

Estimated data shows Amazon (Ring) leading the smart home surveillance market with a 35% share, followed by Google (Nest) at 30%.

Where Ring Won't Draw the Line

Siminoff says Ring isn't building mass surveillance infrastructure. But the company has avoided specifying where it will draw lines on what Search Party can do.

Will it eventually search by faces? Not addressed.

Will it work across multiple neighborhoods or entire cities? Not addressed.

Will third parties other than police eventually access it? Not addressed.

Will it track people over time, building profiles of movement patterns? Not addressed.

Will it work in real-time, alerting police to people matching descriptions as they move through neighborhoods? Not addressed.

Will Search Party ever be integrated with facial recognition databases, either government or commercial? Not addressed.

These are reasonable questions. They're questions that anyone concerned about surveillance should want answered. But Siminoff has chosen not to answer them, instead talking about how valuable video evidence is and how he believes most people actually want more cameras, even if they claim otherwise.

This is a fundamental abdication of responsibility. Ring built this technology. Ring deployed it at scale. Ring designed it to be as powerful and expansive as technically possible. The company created something with massive implications for privacy and freedom, then declined to have a serious conversation about where it should be limited.

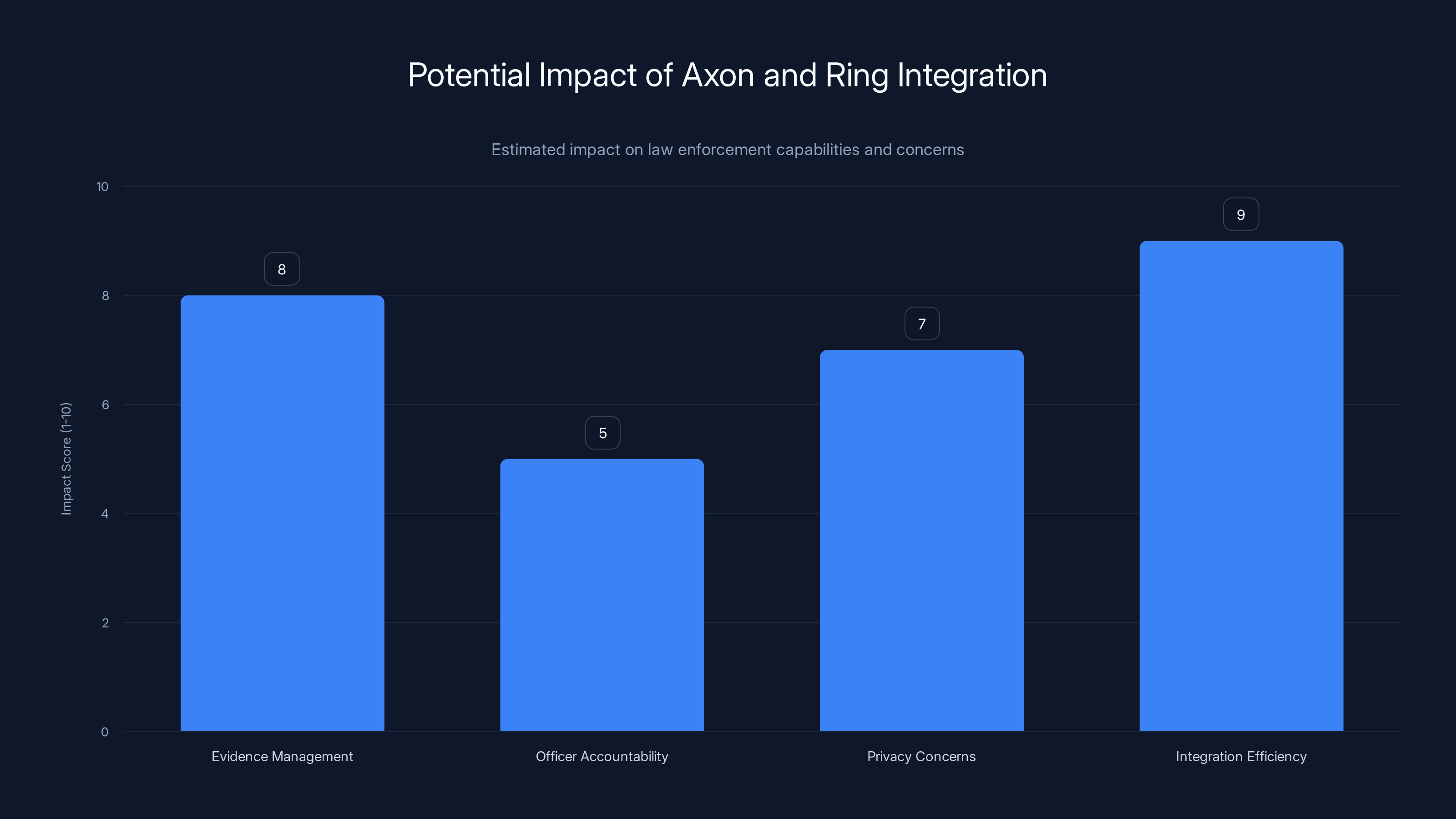

The Axon Partnership and Law Enforcement Integration

Ring's partnership with Axon deserves more attention than it's received. Axon isn't primarily a camera company. It's a software company that builds platforms for law enforcement. Its main product is Tasers, but increasingly it's building enterprise software for police departments, including evidence management systems, records management systems, and officer accountability tools.

The company explicitly markets itself as a platform that connects different types of police technology. Axon is building the infrastructure that would allow footage from Ring cameras to be integrated directly into police departments' evidence management systems. Instead of manually requesting footage from Ring, police could have access that's built into their existing workflows.

This integration is happening quietly. Most people don't know about it. But when it's complete, the friction between private surveillance networks and law enforcement will essentially disappear. Footage from Ring cameras will flow automatically into police systems, available for searching, archiving, and analysis.

Axon has its own issues. The company's platforms have been criticized for being opaque, for not providing enough oversight, and for creating systems where police have too much power with too little transparency. Integrating Ring's network into Axon's infrastructure would make those problems worse.

Ring justified the Flock Safety partnership cancellation by saying it was uncomfortable with the company's connections to ICE. But Axon has its own problematic connections and partnerships. The company's tools are used by agencies including Customs and Border Protection. Building deeper integration with Axon means Ring's footage is more likely to end up in immigration enforcement databases.

Siminoff hasn't addressed this. He's focused on explaining why map graphics were a mistake while quietly expanding partnerships that lock Ring cameras into law enforcement infrastructure.

The integration of Ring with Axon is expected to significantly enhance evidence management and integration efficiency, but it raises substantial privacy concerns. Estimated data.

The Network Effect and Lock-In

One reason Ring continues to expand aggressively is that the value of its network increases with every new camera added. This is the classic network effect. One Ring camera is useful. A hundred Ring cameras is much more useful. A million Ring cameras is dramatically more useful.

Search Party makes this network effect even more powerful. The more footage Ring has indexed, the more powerful Search Party becomes. The more people use it, the more valuable it is. The more law enforcement agencies have access, the more pressure there is to add more cameras.

Once a neighborhood has sufficient Ring camera coverage, opting out becomes nearly useless. If ninety percent of your street has Ring cameras, it doesn't matter that your house doesn't. You're still being recorded. You're still part of the network. Your movements are still searchable.

This creates a form of surveillance lock-in. Neighborhoods reach a point where the network is so dense that individual choice becomes irrelevant. You can't prevent yourself from being surveilled. You can't prevent your movements from being searchable. The best you can do is remove your own cameras, which doesn't actually help because you're still being recorded by neighbors.

Ring understands this. The company's expansion strategy is designed to hit critical mass in neighborhoods, knowing that once coverage is high enough, the network becomes self-reinforcing. More people buy cameras because everyone else has them. Police want access because the footage is so comprehensive. The system grows.

Siminoff talks about making neighborhoods safer, but what Ring is actually doing is systematically removing the possibility of anonymity in semi-public spaces. You can't walk down your street without being recorded and indexed. You can't visit a friend's house without your movements being logged. You can't exist in the neighborhood without being part of a comprehensive surveillance system.

The Comparison To Other Surveillance Technologies

To understand how significant Ring is, it helps to compare it to other surveillance technologies that have raised concerns.

Automated license plate readers capture your license plate number as you drive. That's invasive, but it's limited. The system can track where your car is, but not where you are. Law enforcement can use it for investigations, but only with specific targets in mind.

Security cameras in retail stores and offices capture you, but only in those specific locations. You know you're being recorded (or you should). The footage is limited in scope.

Facial recognition databases can identify you from photos, but only if you're in the database and only if someone is running your face against it. It's a powerful tool, but it's reactive.

Ring's system is different. It's comprehensive, continuous, searchable, and integrated with law enforcement. A person using Ring cameras can be tracked across an entire neighborhood in real-time. Their movements can be searched retroactively using vague descriptions. Law enforcement can access the footage without a warrant. AI can identify them based on appearance.

No other consumer technology combines these characteristics. Combine Ring's network, Search Party's functionality, AI's power, and law enforcement integration, and you have something more comprehensive and intrusive than most government surveillance systems.

The difference is that Ring is building this with private money, private infrastructure, and private labor. It's not being debated in Congress. It's not being regulated by the FCC or FTC. It's being deployed by a corporation whose business model depends on expanding the system as aggressively as possible.

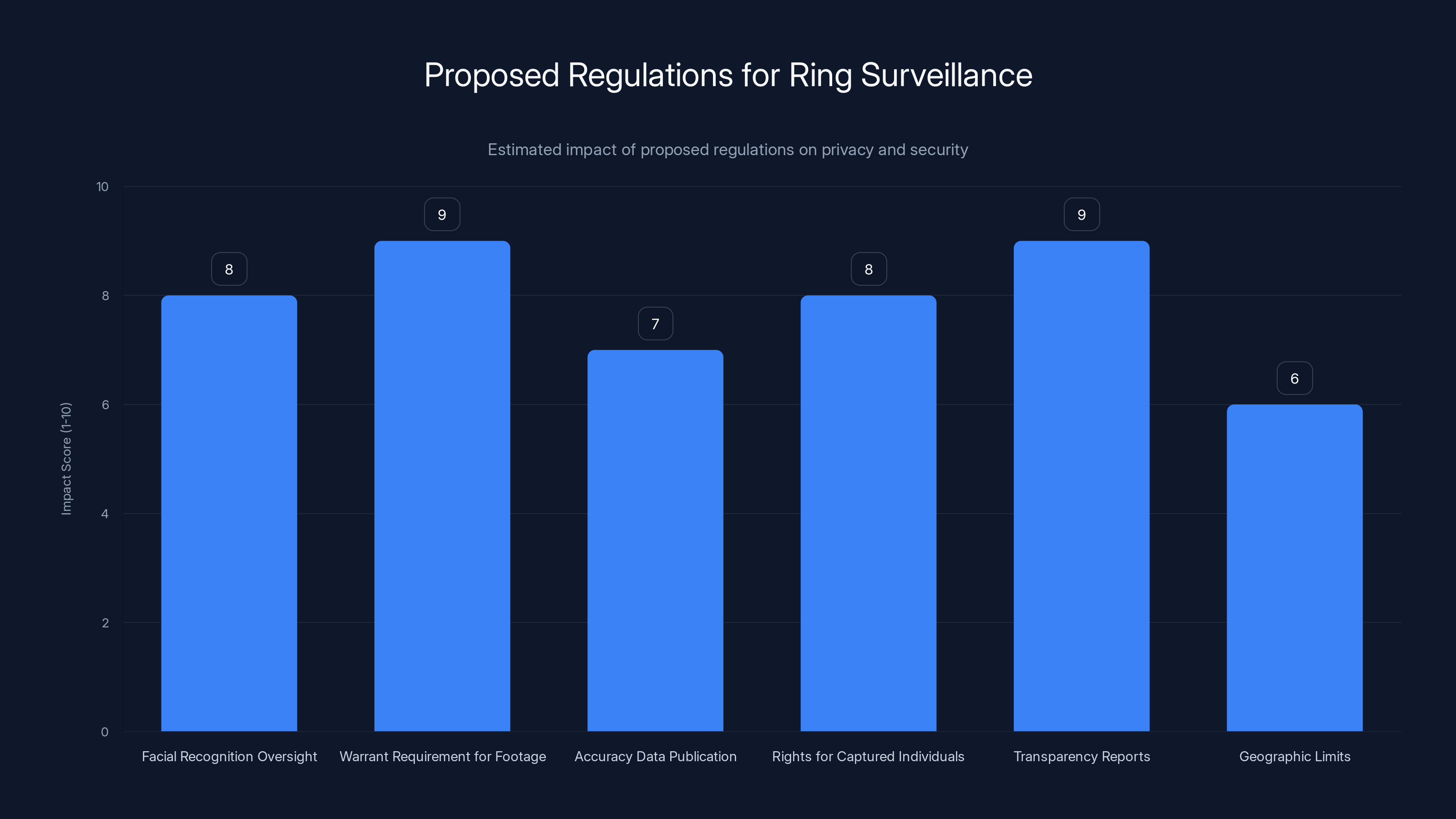

Estimated impact scores suggest that warrant requirements and transparency reports could significantly enhance privacy and security. Estimated data.

The Broader Context: Smart Home Surveillance

Ring isn't operating in isolation. It's part of a broader trend where homes are becoming surveillance platforms.

Amazon, which owns Ring, is expanding smart home devices that capture video and audio. Echo devices with cameras are becoming more common. Alexa-enabled devices that listen constantly are in millions of homes. Amazon is building the infrastructure for comprehensive home surveillance integrated with its retail and advertising platforms.

Google has similar ambitions through Nest and its partnership with various smart home companies. Apple is positioning itself as the privacy-focused alternative but still collecting significant data.

Smartphones, which most people carry constantly, are surveillance devices. They track location, monitor apps, capture photos, and record audio. Companies collect this data for advertising, law enforcement, and increasingly, for predictive policing systems.

Ring represents a specific evolution of this trend: taking the surveillance that already happens inside homes and extending it outward into public and semi-public spaces. It's the logical next step in a trajectory where comprehensive surveillance becomes the default rather than the exception.

Siminoff's position is that this is good. More information is better. Video evidence is valuable. Neighborhoods are safer with cameras. These claims might be true in some contexts. But they ignore the costs: the loss of privacy, the power imbalance between individuals and institutions, the ability to track and control populations, the chilling effects on freedom of movement and expression.

Ring has made a choice to expand aggressively in this direction. Siminoff has chosen to defend that choice rather than acknowledge the legitimate concerns it raises. He's betting that people will choose convenience and perceived safety over privacy and freedom. History suggests he might be right. But that doesn't make it the right choice.

What Regulation Should Look Like

If there's any hope of controlling Ring's expansion, it will come through regulation. The company isn't voluntarily limiting itself. The market isn't imposing restrictions. The only lever that might work is law.

Effective regulation would need to address several specific issues.

First, facial recognition in search systems should be prohibited without explicit legal authority and judicial oversight. If Ring wants to add facial recognition, that's a decision for legislatures and courts, not for a corporation to make unilaterally.

Second, law enforcement access to Ring footage should require warrants for anything beyond emergency situations. If police want to search for a specific suspect, they should have to get judicial permission. The current Community Requests system is too loose.

Third, Ring should be required to publish accuracy data for Search Party, including error rates broken down by demographics. If the system is going to be used to identify suspects, the public should know how often it makes mistakes.

Fourth, people captured in Ring footage should have rights. They should be notified if they're identified by law enforcement as suspects. They should have the ability to know if footage of them exists. They should have some ability to challenge or correct information.

Fifth, Ring should be required to publish transparency reports about law enforcement requests, how they're fulfilled, and what happens to the footage. Secrecy enables abuse.

Sixth, geographic limits should be imposed. Search Party should not be allowed to operate across city boundaries without explicit local authorization. Neighborhoods should have the ability to opt out of comprehensive surveillance infrastructure.

These aren't radical proposals. They're basic privacy protections that other surveillance technologies are subject to. But implementing them would require political will that currently doesn't exist.

Siminoff won't voluntarily accept these limitations. Ring won't limit its own expansion. The market won't impose restrictions. Which means the question is: will regulators act before surveillance reaches a point where it's too embedded to control?

The Uncomfortable Truth About Surveillance

Here's what nobody wants to acknowledge: surveillance can actually make neighborhoods safer.

If you're concerned about package theft, Ring cameras help. If you're worried about burglary, recorded footage can help police catch thieves. If there's violence in your neighborhood, video evidence can help solve crimes and convict perpetrators. These are real benefits that real people experience.

Siminoff isn't wrong that video evidence is valuable. He's just wrong to assume that the benefits automatically outweigh the costs. They don't. Benefits and costs have to be weighed against each other, and the calculus is different depending on your position in society.

For a wealthy homeowner in a low-crime neighborhood, Ring might be primarily beneficial. The risks of surveillance are low. The crime-prevention benefits are moderate. The convenience of knowing who's at your door remotely is real.

For a person of color in a neighborhood with a history of police abuse, the calculus is completely different. Police have authority to stop you based on a description that might match you. Police can use Ring footage to build cases against you for minor infractions that wouldn't normally be prosecuted. Police can track your movements and use that against you.

For an activist or protester, Ring surveillance is a tool for identifying and targeting participants in demonstrations. For a person experiencing homelessness, Ring footage can be used to enforce exclusionary policies. For an undocumented immigrant, Ring footage can be shared with immigration enforcement.

The surveillance that makes one person feel safer can make another person feel hunted. Ring hasn't grappled with this tension. Siminoff hasn't acknowledged that the same technology that helps catch a lost dog can also be used to target vulnerable populations.

This is why the questions matter. This is why Siminoff needs to specify where Ring will draw lines. Because surveillance infrastructure, once built, doesn't go away. It evolves. It expands. It gets used in ways that weren't originally anticipated. And the groups with the least power are always the ones harmed most.

The Interview That Didn't Happen

Siminoff's interview with The New York Times was a chance to have a real conversation about these issues. It was an opportunity to acknowledge the legitimate concerns, to specify limits on what Ring would do, to address the tension between surveillance and freedom.

Instead, it was an explanation tour. The company acknowledged that maps in advertisements were a mistake. It promised fewer maps in future ads. It reiterated talking points about safety and privacy.

The hard questions weren't answered because they weren't asked. Or they were asked but the answers weren't reported. Either way, the public still doesn't know where Ring plans to draw the line on surveillance.

That's the fundamental failure here. Ring has built infrastructure with massive implications. It's deployed it at scale. It's expanding it aggressively. And when asked to explain the limits of that expansion, the company essentially declined.

Siminoff talks about making neighborhoods safer. That's admirable. But making neighborhoods safer is the responsibility of communities, not corporations. Ring can contribute to safety, but it can't determine what acceptable tradeoffs are between safety and privacy. That decision belongs to the public.

Until Ring acknowledges that, until Siminoff is willing to have a genuine conversation about limits and tradeoffs, the company will continue to avoid the real questions while the surveillance infrastructure expands in the background.

What Happens Next

Ring will continue to expand. Search Party will add new capabilities. The network will grow denser. Law enforcement integration will deepen. These things are already happening and nothing in recent statements suggests Ring plans to slow down.

At some point, if surveillance density reaches a high enough level, the conversation will shift. Instead of arguing about whether comprehensive surveillance is acceptable, we'll be arguing about how to manage the surveillance that's already here. We'll be asking what regulations are needed instead of what safeguards should be built in from the start.

That's not inevitable. Communities can still choose to limit Ring's expansion. Neighborhoods can still establish policies about where cameras can point and what they can be used for. Cities can still regulate access to footage. States can still pass laws requiring warrants for law enforcement access.

But these things require action. They require people to understand what's at stake. They require demanding that Ring answer the questions Siminoff has avoided.

Siminoff is betting that most people won't demand answers. He's betting that convenience and perceived safety will win out over privacy concerns. He's betting that by the time people understand what's happening, the surveillance network will be too established to challenge.

Maybe he's right. Maybe this is the future we've chosen, even if we didn't realize we were choosing it.

But that's a choice we should make consciously and collectively, not accidentally through a corporation's expansion strategy.

FAQ

What is Ring's Search Party feature?

Search Party is an AI-powered system that allows Ring users and law enforcement to search through video footage by object or person description rather than requiring specific timestamps. Instead of scrolling through hours of video, users can search for keywords like "red jacket" or "bicycle" and AI will identify matching footage across the Ring network. The feature was turned on by default for all users, making their footage searchable without explicit opt-in consent.

How does Search Party differ from traditional surveillance cameras?

Traditional surveillance cameras record and store video, but accessing that footage is labor-intensive and requires knowing approximately when an event occurred. Search Party transforms this reactive system into a proactive, searchable database where AI can query video across multiple properties instantly. This fundamentally changes the nature of surveillance from documentation to search and identification, making it possible to track movements across entire neighborhoods using vague descriptions.

What are the privacy concerns with Ring's system?

The primary concerns include: people being recorded without their knowledge or consent, footage being searchable without warrant requirements, AI systems that make mistakes in identification potentially implicating innocent people, law enforcement access through Community Requests without judicial oversight, and expansion toward facial recognition and cross-neighborhood searching. The system also creates lock-in effects where opting out becomes ineffective once neighborhood coverage becomes dense enough.

Does Ring share footage with law enforcement?

Ring's Community Requests program allows users to voluntarily share footage with police, and users control whether they participate. However, Search Party potentially allows law enforcement to query the network directly through formal requests. Ring says it logs all access and requires formal requests, but the company hasn't specified what "formal request" means or what oversight exists. The company also partners with Axon, which provides law enforcement evidence management systems that could eventually integrate Ring footage directly into police workflows.

Can I delete footage that Ring has collected of me?

Ring users can delete footage from their own cameras, but if you live in a neighborhood with Ring cameras, footage of you may exist on other people's systems without your knowledge. You likely cannot delete footage of yourself captured by neighbors' cameras unless you can convince those neighbors to delete it or successfully request removal through Ring's processes. Ring hasn't clearly specified what rights non-users have regarding footage of themselves.

What limitations has Ring committed to regarding future expansion?

Ring has been notably vague about future limitations. The company confirmed it's adding cat detection to Search Party but hasn't committed to limiting facial recognition, cross-neighborhood searching, real-time tracking, third-party access, or integration with government surveillance databases. Siminoff has avoided specifying where Ring will draw the line on surveillance capabilities, making it unclear what safeguards actually exist.

Why did Ring cancel its Flock Safety partnership?

Ring cancelled the Flock Safety partnership after public backlash revealed that the license plate recognition company was sharing footage with ICE and other immigration enforcement agencies. However, Ring's Community Requests system and Axon partnership provide similar law enforcement integration capabilities, suggesting the cancellation was a response to public pressure rather than a philosophical shift away from surveillance integration.

How accurate is the AI in Search Party?

Ring hasn't published accuracy data for Search Party, making it impossible to know how often the system makes mistakes. Research on similar computer vision systems shows they frequently misidentify people and make systematic errors based on race, gender, and age. The company has deployed a powerful system that can affect people's lives without providing information about reliability or error rates.

What regulations would help address Ring surveillance concerns?

Effective regulations would require: facial recognition prohibitions without legal authority, warrant requirements for law enforcement access, published accuracy data for AI systems, rights for people captured in footage, law enforcement transparency reports, and geographic limits preventing cross-neighborhood searching. Currently, Ring operates with minimal regulation, and the company isn't voluntarily accepting these limitations.

Is Ring's surveillance system actually making neighborhoods safer?

Video evidence can help solve crimes and deter some criminal activity, so Ring's system can contribute to safety in real ways. However, the same infrastructure can be misused for targeting vulnerable populations, enabling police abuse, and chilling freedom of movement. The question isn't whether surveillance helps with crime, but whether the benefits outweigh the costs of comprehensive monitoring, and whether those costs are distributed equally across all groups in a neighborhood.

The Conversation We Need to Have

Ring's expansion isn't inevitable. It's a choice. Siminoff has made choices about how aggressively to deploy surveillance technology, how deeply to integrate with law enforcement, how quickly to add new capabilities. Those choices have consequences that extend far beyond convenience or home security.

The company could have designed Search Party as opt-in rather than default. It could have committed publicly to never adding facial recognition. It could have required warrants for law enforcement access. It could have published accuracy data. It could have specified limits.

It didn't. And when asked to explain those decisions, it offered explanations about maps in advertisements while the actual infrastructure continued expanding.

This is what happens when powerful technology is deployed by private corporations without democratic oversight. The public doesn't get to decide what's acceptable. Corporations decide, and the public finds out afterward.

If you care about this, if you think surveillance infrastructure should be debated before it's deployed rather than after, then the conversation needs to happen now. Demand that Ring answer the hard questions. Ask your elected representatives to regulate surveillance. Organize with neighbors about camera placement and use. Make it clear that the company can't simply expand surveillance without pushback.

Because the infrastructure Ring is building will outlast any single company decision or leadership change. Once comprehensive surveillance networks exist, they become the baseline. Removing them becomes nearly impossible. The only time to debate what's acceptable is before the network becomes too established to challenge.

Siminoff says he believes most people actually want more cameras, even if they claim otherwise. Maybe he's right. But that's a decision society should make consciously, with full information, after genuine debate.

Right now, we're not having that debate. We're having an explanation tour where the company clarifies that maps were a mistake while declining to discuss the actual problem.

That needs to change. And it will only change if we demand it.

Key Takeaways

- Ring's Search Party transforms doorbell cameras from passive recorders into searchable databases, fundamentally changing the nature of neighborhood surveillance from documentation to active identification.

- Ring turned Search Party on by default, automatically including all users' footage in searchable networks without explicit consent, demonstrating the company's control over expansion.

- Law enforcement can access Ring footage through Community Requests without warrants, and deeper integration with Axon's police infrastructure is removing friction for police access.

- AI systems powering Search Party lack published accuracy data and make systematic mistakes that disproportionately affect people of color, yet no safeguards exist for innocent people misidentified by the system.

- Ring founder Jamie Siminoff refuses to specify limits on future expansion, declining to answer whether Search Party will eventually include facial recognition, cross-neighborhood searching, or other capabilities that would fundamentally alter surveillance scope.

Related Articles

- Ring's Super Bowl Ad Backlash: The Surveillance Debate [2025]

- Ring's AI Search Party: From Lost Dogs to Neighborhood Surveillance [2025]

- Ring Cancels Flock Safety Partnership Amid Surveillance Backlash [2025]

- Google Recovers Deleted Nest Videos: What This Means for Your Privacy [2025]

- How to Disable Ring's Search Party Surveillance Feature [2025]

- DJI Romo Hack: How One Loophole Exposed a Global Robot Army [2025]

![Ring's Surveillance Problem: What Search Party Really Means [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ring-s-surveillance-problem-what-search-party-really-means-2/image-1-1771531708933.png)