Smart Glasses in Court: The Privacy Nightmare Judges Can't Ignore

Mark Zuckerberg walked into a Los Angeles courtroom last year with his team wearing camera-equipped Ray-Ban smart glasses. Within minutes, the judge issued a stern warning: delete any recordings immediately, or face contempt of court charges. What happened next revealed something deeper than a single incident—it exposed a fundamental collision between emerging technology and centuries-old legal protections.

The scene was straightforward enough on the surface. But it represents something much larger happening in courtrooms across America. Smart glasses with built-in cameras are creating an enforcement nightmare for judges who've spent decades protecting courtroom privacy. These aren't bulky recording devices that attract attention. They're fashionable eyewear. Someone wearing them looks like they're just... wearing glasses.

That's the actual problem.

In 2025, we're watching judges scramble to close gaps in laws written for a different era. Federal rules from 1946 banned recording in courts. State laws vary wildly. But none of them anticipated technology that could document an entire trial without anyone realizing it. A witness can't tell if the juror behind them is recording. A minor in a sensitive case has no way to know if their face is being captured. A confidential informant testifying under protection? They could be photographed without detection.

What makes this even more urgent is scale. Meta sold 7 million pairs of Ray-Ban smart glasses in 2025 alone. Apple is moving into the market. Augmented reality hardware is becoming mainstream. The question isn't whether smart glasses will show up in courtrooms again—it's how quickly judges and legislators can adapt before it becomes a systematic problem.

TL; DR

- Smart glasses enable covert recording: Ray-Ban glasses with built-in cameras can record courtroom proceedings without obvious detection, creating privacy risks for witnesses, jurors, and sensitive cases.

- Federal courts have banned recording since 1946: But those rules were written for cameras and film, not wearable AI that looks like regular eyewear.

- Multiple jurisdictions are now acting: Courts in Hawaii, Wisconsin, North Carolina, and others have issued smart glasses bans, but enforcement remains extremely difficult.

- The technology is scaling fast: 7 million smart glasses sold in 2025, with major tech companies pushing deeper into the space.

- Legal frameworks are badly outdated: Current rules don't account for covert recording capability, and legislators haven't caught up with the technology.

Several U.S. courts have explicitly banned smart glasses, with Forsyth County and Colorado considering or implementing bans in 2024.

The Zuckerberg Incident: What Actually Happened

On January 15, 2025, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg appeared at a Los Angeles federal courthouse for the Mark Zuckerberg v. Paul/Facebook Pages case. What should have been routine court proceedings became a test case for how unprepared the legal system is for AI-enabled wearables.

According to multiple reports, Zuckerberg arrived with a team wearing Meta's latest Ray-Ban smart glasses. These aren't cheap novelties—they're sophisticated devices with high-resolution cameras, AI processing, and the ability to stream or record video seamlessly. The glasses look entirely normal. Unless you knew what to look for, you wouldn't know they contained a camera.

Judge Carolyn Kuhl noticed. According to CNBC's coverage, she immediately issued a warning to the entire courtroom: "If you have done that, you must delete that, or you will be held in contempt of the court." She then ordered everyone wearing AI-enabled smart glasses to remove them.

But here's where it gets real. Even after the warning, at least one person was spotted wearing the glasses in a courthouse hallway near jurors. When plaintiff attorney Rachel Lanier confronted the person, they claimed the glasses weren't recording. Claim. Not verification. Not proof.

This is the actual nightmare scenario. You can't verify whether someone's glasses are recording without taking them off and inspecting the device. A person can say "don't worry, I'm not recording" while simultaneously recording. There's no external indicator. No light. No way to know.

What made this worse wasn't just the presence of the glasses—it was that Zuckerberg himself brought them. This wasn't a random person trying to sneak a recording. It was Meta's CEO demonstrating the company's latest hardware in one of the most legally sensitive environments in America. It sent a message: the technology is here, it's here at scale, and nobody's ready for it.

How Smart Glasses Recording Works (Technical Reality)

To understand why judges are so concerned, you need to understand what these devices actually do.

Meta's Ray-Ban smart glasses contain a 12-megapixel camera integrated directly into the frame. The camera runs continuously in standby mode, capturing images and video when activated. The glasses connect to your phone via Bluetooth, where all processing and storage happens. The system includes AI-powered features like real-time object recognition, translation, and visual search.

Here's what matters legally: the recording is seamless and unobtrusive. There's no notification to other people in the room. No shutter sound (like smartphone cameras have). No obvious motion that would tip someone off. You can activate recording through voice commands, gestures, or a button press.

The AI component makes it worse. The glasses don't just record. They process what they see. They can identify faces. They can read lips. They can extract text from documents. In a courtroom, this means someone wearing the glasses could theoretically capture:

- The complete testimony of a witness

- The faces and identifying information of jurors

- Confidential documents presented as evidence

- The appearance and statements of protected witnesses

- The faces of minors who should remain anonymous

- Sensitive victim testimony in abuse or assault cases

All without a single person realizing it happened.

Compare this to a smartphone. If someone tried to record testimony with their phone out, people would notice. They'd see the screen. They'd see the person's hand movements. Judges can ask about it. But smart glasses? They pass as medical devices or corrective lenses. A person with poor vision has a legitimate reason to wear them. Enforcement becomes almost impossible.

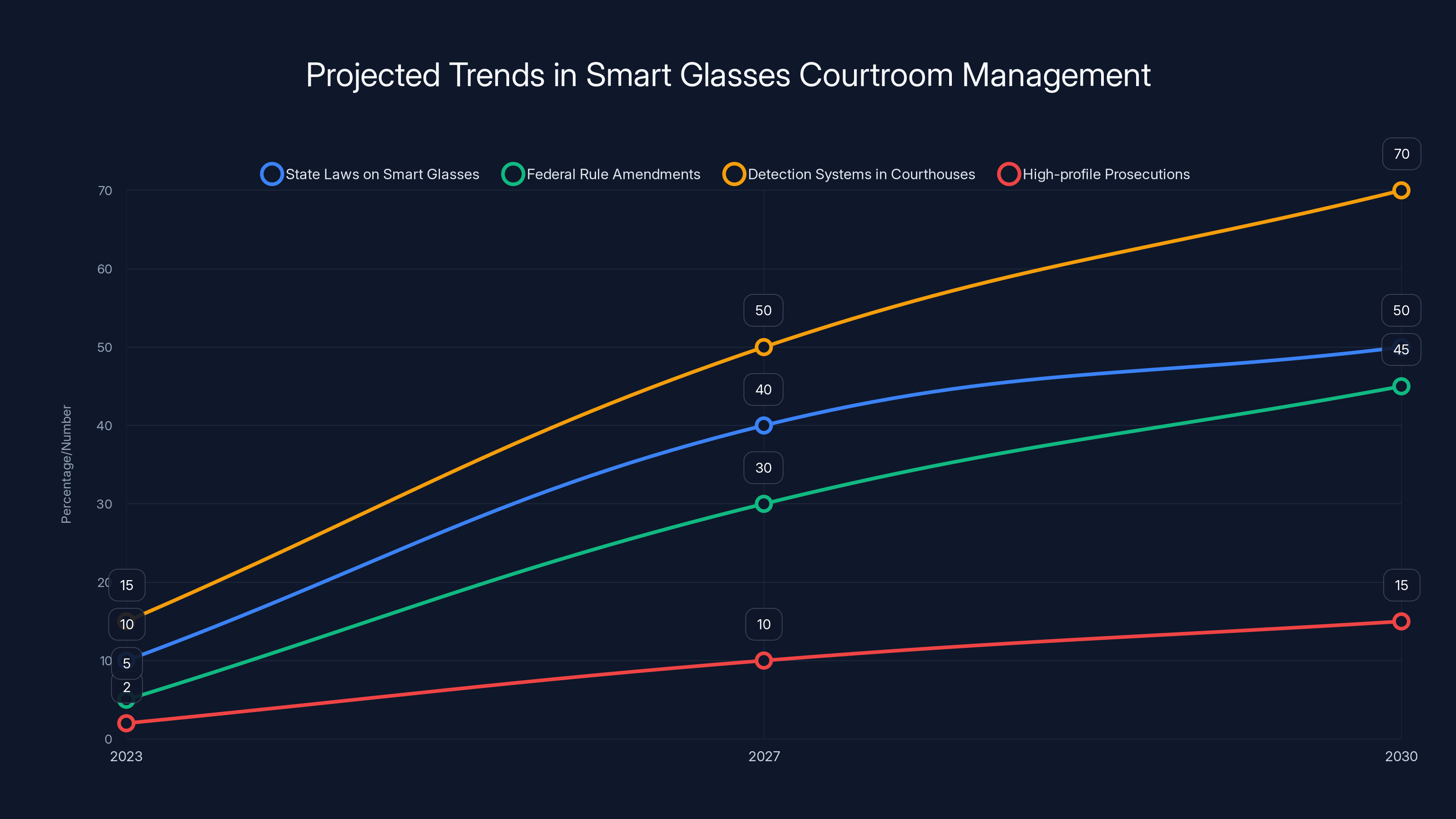

By 2030, detection systems and legal frameworks are expected to become standard in managing smart glasses in courtrooms. Estimated data.

The Legal History: Why Courts Ban Recording

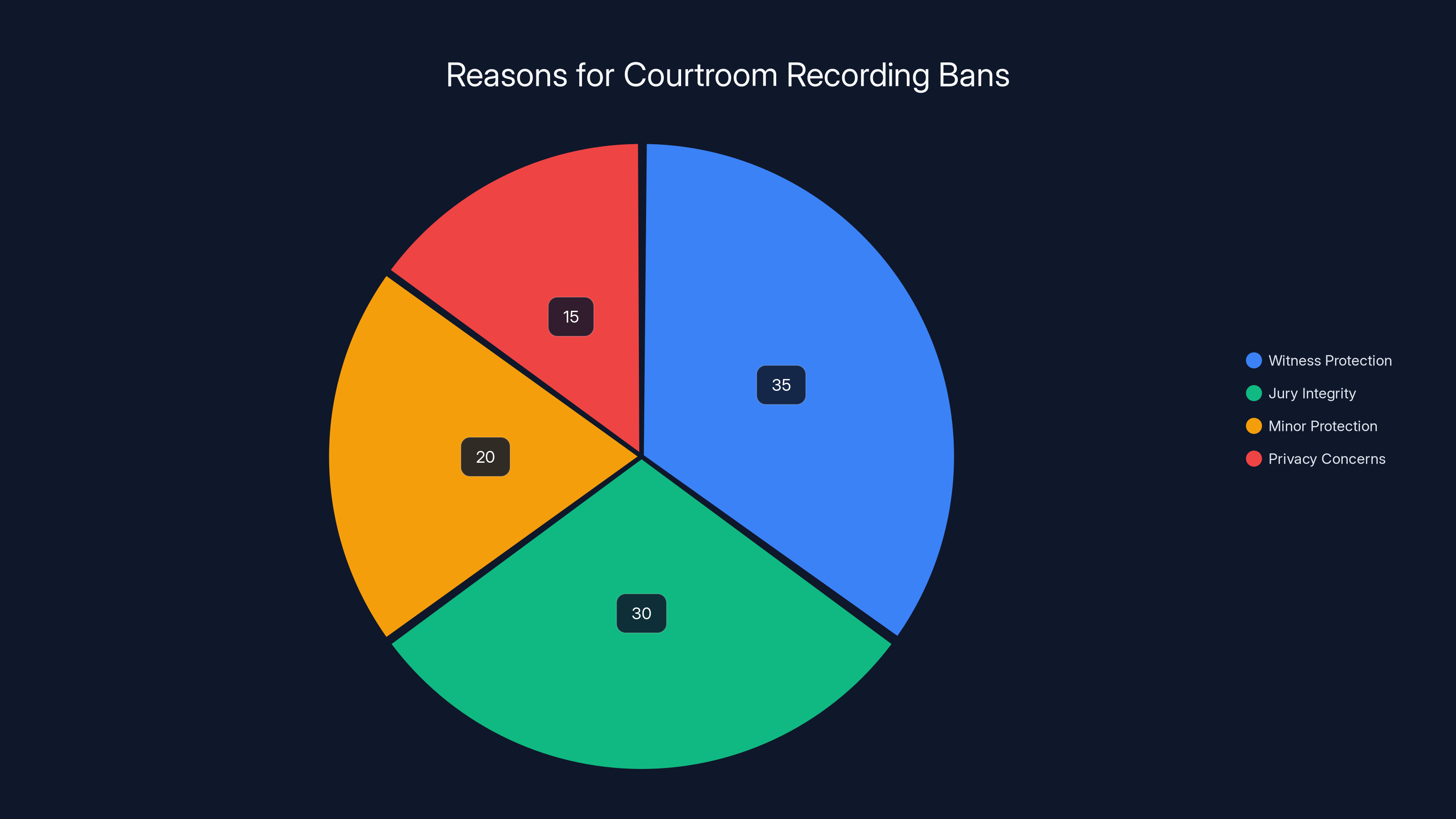

The ban on courtroom recording isn't new, and it wasn't random. It emerged from hard-learned lessons about justice, fairness, and privacy.

Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 53, established in 1946, prohibited recording and broadcasting of criminal proceedings in federal courts. The rule came from decades of experience with early radio broadcasting and newsreel cameras in courtrooms. Judges learned that the presence of recording equipment changed behavior—witnesses became more fearful, jurors became more self-conscious, and the proceedings became less about justice and more about performance.

Then in 1972, the Judicial Conference of the United States expanded the ban. They adopted rules against recording in both criminal and civil proceedings, including areas around courtrooms. The only exception came in 2020, when COVID-19 forced federal courts to allow remote proceedings via video conference. Even that exception was meant to be temporary. It ended in 2023.

State courts vary widely. Some states allow extensive recording with judicial approval. Others restrict it to media under specific conditions. But the underlying principle remained consistent: courtrooms are not for public documentation. They're for justice.

Why? Several reasons converge:

Witness Protection: Witnesses in criminal cases sometimes face real danger if their identities become public. Recording creates a permanent record that could be shared online, used by criminals to locate witnesses, or weaponized against someone who testifies against a powerful person or organization.

Jury Integrity: Jurors are supposed to base decisions on evidence presented in court, not outside information. If proceedings are recorded and posted online, jurors might be influenced by social media commentary, public outrage, or coordinated pressure campaigns. They might face harassment based on their verdict.

Minor Protection: Children involved in custody disputes, abuse cases, or as witnesses to crimes are often protected by anonymity rules. These rules are violated the moment someone records video of the courtroom.

Victim Privacy: Victims of sexual assault, trafficking, or other sensitive crimes deserve protection. Recording creates evidence of their involvement in the case, which can be used to harass, shame, or re-traumatize them.

Legal Principle: The record of a case is supposed to be the official court transcript, not random video. The transcript is controlled, accurate, and certified. A video recording is uncontrolled, potentially misleading, and subject to editing or misrepresentation.

These principles haven't changed. What changed is the technology. Laws written for cameras and film don't anticipate technology that disguises itself as eyewear.

State-Level Response: The Ban Wave Begins

Faced with the reality of smart glasses, several jurisdictions have started taking action. The response has been reactive rather than proactive, but it's happening.

The U. S. District Courts for the District of Hawaii and the Western District of Wisconsin explicitly banned smart glasses in courtrooms. The bans specify that any device capable of recording must be removed before entering. The problem? "Capable of recording" now means almost any eyewear, since smart glasses look identical to regular glasses.

The Forsyth County Court in North Carolina issued a ban in 2024. Colorado's District Court is considering similar restrictions. These aren't fringe courthouses—they're mainstream jurisdictions recognizing a problem.

But here's the enforcement nightmare: how do you enforce a ban on something you can't visually identify?

A court marshal can't inspect every pair of glasses worn by everyone entering the building. That would create massive delays, potential discrimination issues, and still wouldn't catch everyone. Someone could have smart glasses in their bag and only put them on after security. Or they could claim the glasses are prescription lenses for a medical condition.

Some courts are trying technological solutions. A few have installed devices at entrances that can theoretically detect active recording devices. But these systems are expensive, unreliable with smart glasses (which can be dormant), and create bottlenecks.

The real problem is scope. Seven million pairs of Ray-Ban glasses sold in 2025 alone. Add in glasses from other manufacturers, and you're talking about millions of potential recording devices already in circulation. Every courtroom in America will eventually encounter this problem.

Federal Courts and the Existing Framework

Federal courts operate under Rule 53, but the rule is vague about enforcement in modern contexts.

The rule states: "Except as otherwise provided by a statute or these rules, the court must not permit the taking of photographs in the courtroom during judicial proceedings or the broadcasting of judicial proceedings from the courtroom." Written in 1946, it clearly anticipated cameras. Photography. Broadcasts.

But does Rule 53 cover smart glasses recording video directly to a cloud server? The rule's intent is absolutely clear. The text is less so.

Federal courts have attempted to clarify through standing orders and local rules. Many district courts now include language about "electronic recording devices" and "wearable technology." But these additions are recent and inconsistent across different courts.

Here's the practical problem: a federal judge in New York might issue a clear ban on smart glasses, while a federal judge in California has no specific local rule. Lawyers and defendants moving between jurisdictions aren't always clear on what's allowed. Someone who complied in one courtroom might violate rules in another.

The Zuckerberg incident highlighted this gap. The judge issued a warning, but there was no explicit pre-existing rule about smart glasses specifically. She had to improvise based on the principle of Rule 53, not the text itself.

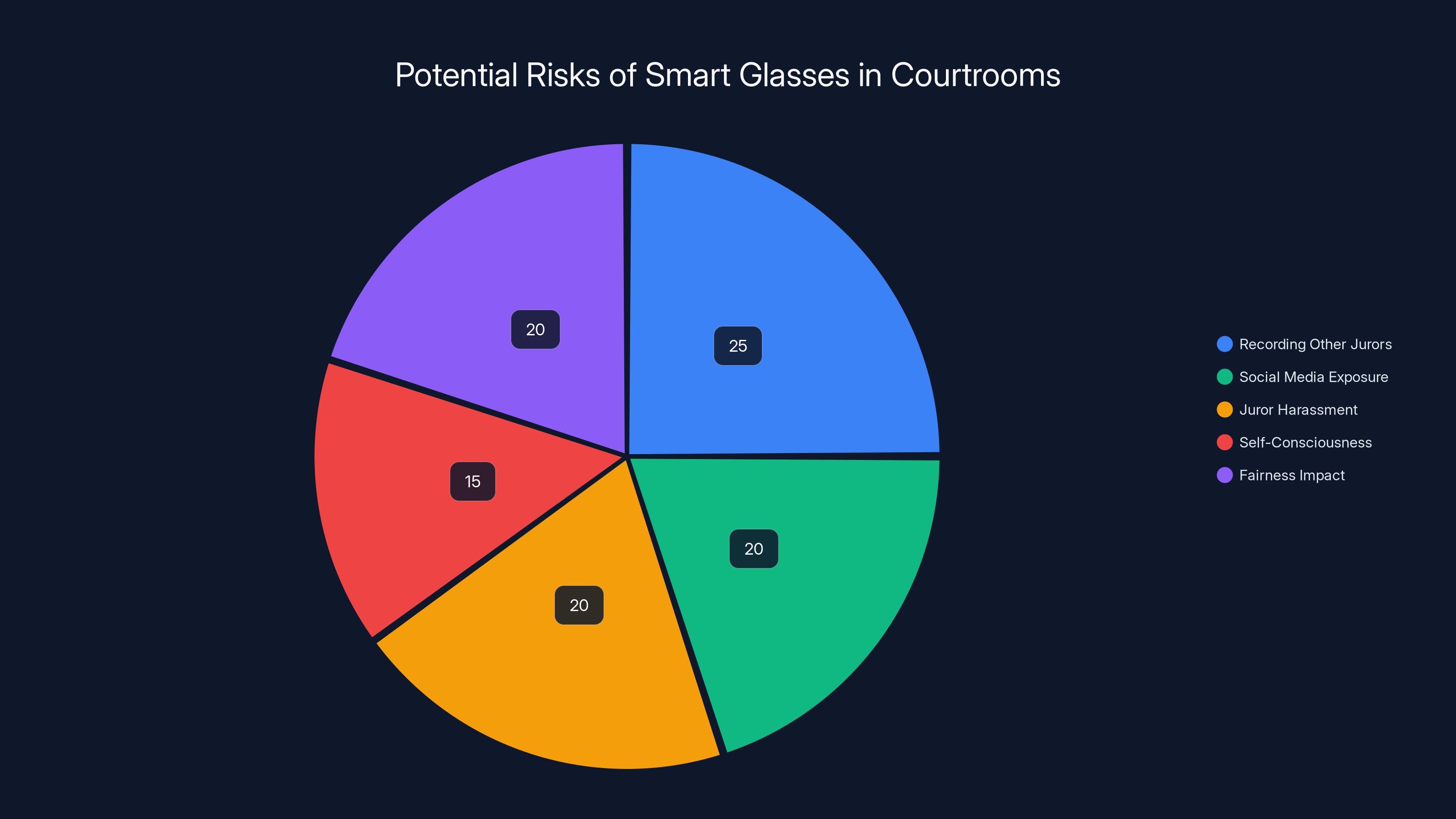

Estimated data shows that recording other jurors and social media exposure are the top risks associated with smart glasses in courtrooms, each accounting for about 20-25% of the total risk.

The Juror Risk: Why Smart Glasses Create Unique Dangers

The smartest concern judges express isn't about recording by lawyers or observers. It's about jurors recording other jurors.

Jurors sit in close proximity for hours, days, or weeks. They're often curious people selected for their engagement with a case. And they increasingly carry smart glasses as regular eyewear.

Imagine a juror wearing Ray-Bans sits in the jury box. They activate recording with a voice command or button press. Over three days, they record every juror's reaction, every emotional response, every moment of eye contact or distraction. They record jury deliberations if they record during breaks. They capture enough footage to create a complete documentary of how 12 people actually arrived at their verdict.

Then that footage gets posted on social media.

The consequences cascade. Other jurors could be identified and harassed. The jurors who appeared uncertain could be targeted. Future jurors would know this is possible and become self-conscious about their reactions. The entire jury system depends on people feeling free to deliberate without performance pressure.

This isn't hypothetical. In one case mentioned on the r/legaladvice subreddit, a plaintiff showed up wearing Meta glasses. The attorney reported it because they knew that if the jury saw the other side documenting proceedings, they'd become paranoid about being recorded. The very presence of recording capability—even if it wasn't being used—affected the fairness of the trial.

This is harder to legislate against than actual recording. You could theoretically ban recording. But can you ban someone from wearing glasses? That becomes a different problem. Disability discrimination issues. Clear sight line issues. Medical necessity claims.

Yet if you allow glasses, you've allowed recording capability to exist in the courtroom.

Meta's Role: How Tech Companies Created the Problem

Meta deserves credit for bringing smart glasses to mainstream adoption. They also deserve scrutiny for the implications.

Ray-Ban smart glasses are excellent products. The cameras are high quality. The AI features work. The design is sleek enough that most people don't realize they're recording devices. Meta sold 7 million pairs in 2025, and demand is growing.

This success happened because Meta didn't position the glasses as surveillance devices. They marketed them as productivity tools, memory aids, and social features. Record your climbing expedition. Capture family moments. Share your perspective with friends. The recording capability is presented as a feature, not the feature.

But that same capability makes them perfect for covert recording. Meta didn't create this capability maliciously. They created it because it's genuinely useful. The problem is that "genuinely useful" and "genuinely dangerous in certain contexts" aren't mutually exclusive.

Meta's response to the Zuckerberg incident was notable for its absence. The company didn't issue a statement about courtroom etiquette or suggest guidelines. They didn't announce any built-in safeguards. They just let it play out.

This creates a credibility problem. If Meta had come forward with proactive solutions—built-in warnings when near courthouses, automatic recording disables in legal buildings, anything—they'd have demonstrated responsibility. Instead, their CEO was seen demonstrating the product in the most legally sensitive environment possible, and the company stayed silent.

Other tech companies are watching. Apple is developing its Vision Pro headset with even more advanced recording capability. Ray-Ban's success validates the market. Without pushback from tech companies themselves, courts will be left alone to manage the problem.

Enforcement: The Impossible Problem

Judges face a practical enforcement nightmare with smart glasses.

Traditional courtroom security works by excluding visible threats. A camera gets spotted. A recording device gets confiscated. But smart glasses look like medical devices. Someone can claim they need them for vision correction. Someone can claim they're prescription lenses. A court marshal can't inspect everyone's eyewear without violating privacy and potentially creating liability.

Take the Zuckerberg case again. After Judge Kuhl issued her warning, someone was still seen wearing glasses in the hallway. What could the judge actually do? Issue a contempt charge against someone wearing glasses? Good luck getting that to stick on appeal. The person claims they're just wearing prescription lenses. The court can't prove otherwise without technological inspection that might be unconstitutional.

Some courts have tried device detection at entrances. Walk through a portal, and it theoretically detects active recording devices. But smart glasses can be dormant, and detection systems have high false positive rates. They slow entry. And they cost significant money.

Other courts rely on peer reporting. If you see someone recording, you report it to a marshal. But this only works if:

- You notice the recording

- You recognize the glasses as smart glasses

- You're willing to challenge someone

- You can prove they were actually recording

None of these are guaranteed.

The honest enforcement solution doesn't exist yet. You'd need technology that reliably detects active recording from a distance, which raises its own civil liberties questions. Or you'd need to ban anyone from wearing glasses that could potentially record, which creates disability discrimination problems. Or you'd need cultural shifts where people accept they might be recorded in courtrooms, which destroys centuries of legal privacy protection.

Judges are caught between legal principles they can't compromise and enforcement tools they don't have.

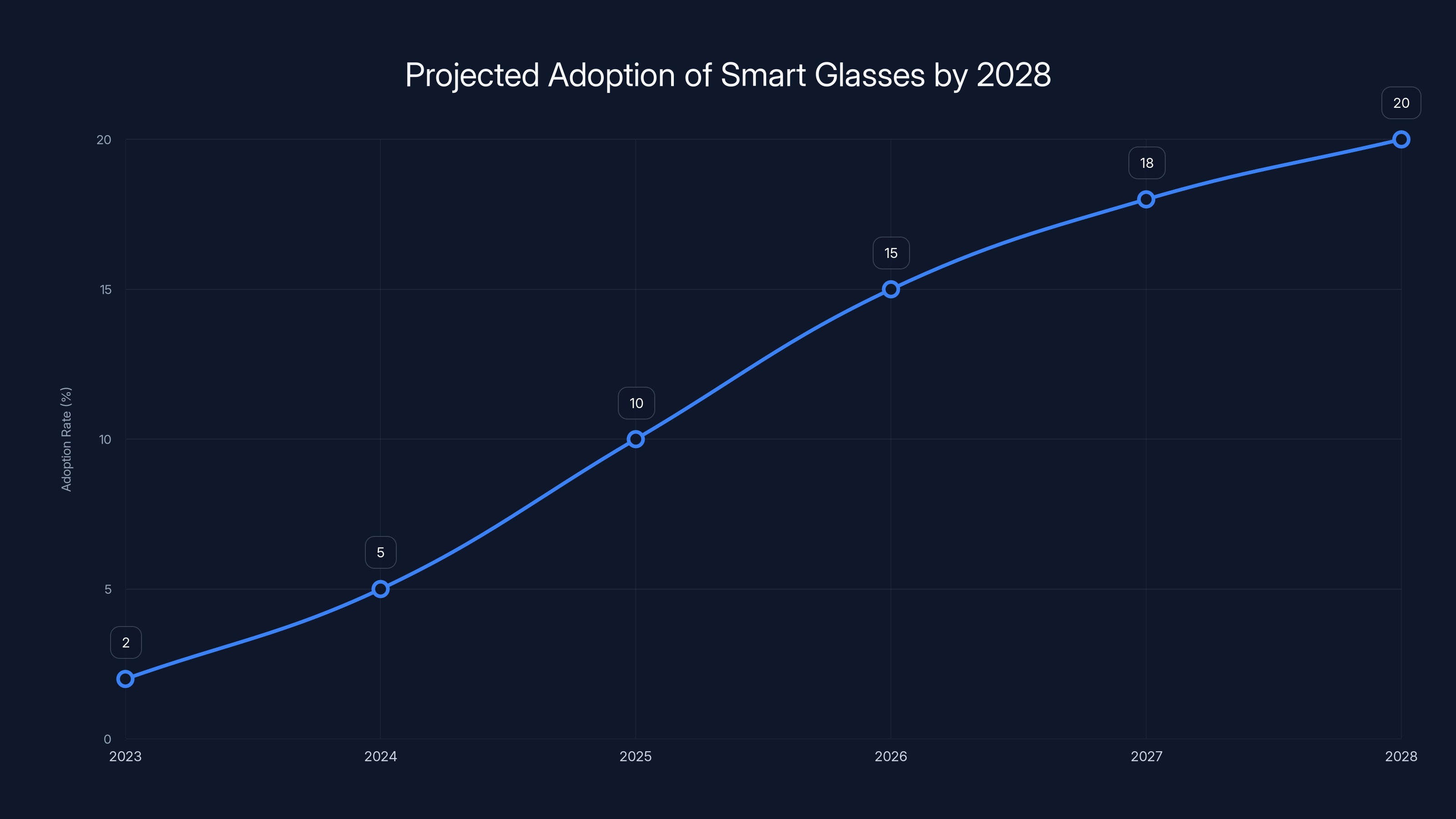

Estimated data suggests smart glasses adoption could reach 20% by 2028, driven by Apple's market entry.

Victim and Witness Privacy: The Collateral Damage

Legal protections for witnesses and victims assume their identities can remain protected. Smart glasses change that equation.

Consider a witness testifying in a human trafficking case. The witness is protected by anonymity rules. They're allowed to testify with their face obscured or from behind a screen. The intent is to prevent traffickers from identifying and retaliating against them.

But if someone in the courtroom is wearing smart glasses recording video, that protection evaporates. The video capture happens regardless of how the courtroom is physically arranged. The witness's face, voice, and testimony are all recorded. That recording could be shared anywhere, posted anywhere, used to identify the witness anywhere.

The same applies to minors. Children in custody disputes, abuse cases, or as witnesses to crimes are protected by anonymity rules. But a parent or observer with smart glasses could record the child's face, voice, and full testimony. That record could then be used to harm the child, be shared on social media, or weaponized in custody disputes.

Sexual assault victims often testify under conditions designed to minimize exposure. They might have the courtroom cleared of certain people. They might be allowed to testify via video from another room. All of this assumes the courtroom itself is controlled—that video of the victim won't be recorded and distributed.

Smart glasses destroy that assumption.

The victims' rights advocates understand this. They're pushing for stronger smart glasses bans in courtrooms. But they're also recognizing that bans alone won't work. They're calling for:

- Explicit state laws with clear enforcement mechanisms

- Technological solutions that reliably detect recording

- Criminal penalties for recording in protected courtroom areas

- Civil liability for distributing recordings made in violation of court orders

- Training for court personnel on recognizing smart glasses

These are all reasonable. They're also all insufficient to fully solve the problem, because the technology is too easy to hide.

Case Law Gaps: What Courts Actually Have to Work With

The legal landscape is patchwork and insufficient.

Existing case law on courtroom recording assumes the recording device is obvious. Courts have ruled on cameras, film equipment, audio recorders. They've established principles about when recording is allowed (rarely) and when it's prohibited (almost always). But cases written before smart glasses existed don't anticipate glasses that look like regular eyewear.

For example, some state court decisions allow media to record proceedings under specific conditions. These decisions detail how recording devices should be positioned, when they can be active, what they can document. All of this assumes recording equipment is visible and can be managed.

Apply that precedent to smart glasses, and it breaks down. You can't position a recording device if the recording device is being worn. You can't control when it's active if the person just presses a button on the frame. You can't manage what it documents if it's recording video from the wearer's perspective.

The gap between existing law and new reality is where the problem lives.

Some judges are trying to apply existing law creatively. Federal Judge Carolyn Kuhl used the underlying principle of Rule 53 to issue her warning, even though the rule doesn't specifically mention smart glasses. But this creates inconsistency. Different judges interpret the rules differently. Precedent isn't established.

Legislators are starting to move. A few states have introduced bills specifically addressing smart glasses in courtrooms. But legislation is slow. It takes time to draft, debate, pass, and implement. And by the time legislation passes, the technology has often evolved again.

Apple's Entry: The Problem Gets Worse

Meta didn't invent smart glasses. But they perfected the form factor and achieved scale. Now Apple is entering the market, and that changes everything.

Apple's Vision Pro headset is more expensive and more obviously a wearable computer. But Apple's developing successors that will look more like traditional glasses. When Apple enters a market, adoption accelerates dramatically. i Phones weren't the first smartphones, but they created the smartphone era.

Apple's products also integrate deeply into criminal justice workflows. Police departments use i Phones. Courts use i Pads. Defense attorneys use Macs. Apple has institutional relationships with law enforcement and the judiciary.

When Apple releases smart glasses that look like regular eyewear, adoption will likely exceed Meta's by orders of magnitude. And suddenly, smart glasses won't be a novelty—they'll be ubiquitous.

This is the real timeline threat. Courts have maybe 2-3 years before smart glasses become normal enough that enforcement becomes nearly impossible. If adoption hits 20% of the population by 2028, how do you distinguish between someone wearing smart glasses legally outside the courtroom and someone trying to sneak them inside?

You can't.

That timeline pressure is pushing jurisdictions to act now, before the problem becomes unsolvable.

The ban on courtroom recording is influenced by multiple factors, with witness protection being the most significant, followed by jury integrity and minor protection. Estimated data.

Solutions in Development: Technological and Legal

There are multiple approaches being discussed to address the smart glasses problem.

Technological Detection: Companies are developing devices that can detect active recording from a distance. These work by identifying the wireless signals that smart glasses emit when transmitting video. But the technology is imperfect, creates false positives, and raises civil liberties questions about scanning people's personal devices.

Built-in Geofencing: Some propose that smart glasses manufacturers include GPS-based technology that automatically disables recording when the wearer enters a courthouse. But this requires manufacturer cooperation, creates privacy concerns about location tracking, and can be disabled or spoofed.

Blockchain Recording: One proposal suggests that all courtroom proceedings be recorded on tamper-proof blockchain, which would eliminate the need for private recording and create an official record everyone can trust. But this requires massive infrastructure investment and legislative coordination.

Temporal Bans: Rather than banning smart glasses entirely, some propose time-based restrictions. Smart glasses could be allowed in courthouse lobbies or public areas but prohibited in actual courtrooms or jury areas. This reduces enforcement difficulty but still has obvious loopholes.

Criminal Penalties: Increasing penalties for unauthorized courtroom recording—making it a felony rather than contempt—would deter some people. But it wouldn't prevent determined bad actors, and penalties only matter if you can catch people.

The honest assessment is that no single solution works. The most practical approach is layered:

- Clear, specific local rules that ban smart glasses in courtroom areas

- Consistent enforcement through court marshals and bailiffs

- Criminal penalties for violations

- Victim and witness protections that acknowledge recording might happen despite rules

- Technological solutions where practical (detection at entry points)

- Manufacturer cooperation in building safeguards

- Legislative updates that clearly address wearable recording devices

Even this layered approach isn't comprehensive. But it's better than the current ad-hoc responses.

International Precedent: How Other Countries Handle It

America isn't unique in struggling with technology and courtroom recording.

The United Kingdom has strict courtroom photography laws. Recording of any kind is prohibited without explicit judicial permission. But these rules were developed during the film era, and they're being re-examined as technology changes. British courts are grappling with the same smart glasses problem, though they haven't had a high-profile incident like the Zuckerberg case.

Canada's Supreme Court allows limited media recording under specific conditions. The court controls camera positioning, what can be documented, and how footage can be used. These detailed rules are easier to enforce with traditional cameras but create the same gaps with smart glasses.

Australia has experienced a different version of the problem. Some court proceedings have been livestreamed over social media by observers, creating exactly the victim privacy and witness protection issues courts feared. The country is moving toward stricter recording bans and prosecutions for unauthorized distribution of courtroom video.

Europe's general data protection regulation (GDPR) complicates things further. Recording people's faces without consent in Europe can violate privacy law, independent of courtroom rules. This creates a different enforcement lever. It's not just about courtroom integrity—it's about personal data protection.

The international pattern is clear: every jurisdiction recognizes the problem is real, but no jurisdiction has found a comprehensive solution. They're all improvising, updating, and trying to stay ahead of technology.

America's advantage is that it has time to learn from others' mistakes. But time is finite. Smart glasses adoption curves are steep.

The Broader Surveillance Culture Shift

Smart glasses in courtrooms are the visible manifestation of a larger phenomenon: surveillance technology becoming invisible.

Ring doorbells. Nest cameras. Air Tags. Smart home devices. These technologies are already changing expectations about what's recorded, where, and by whom. For most people, being recorded in public spaces is normal. Cameras are everywhere. Most people have accepted this.

But courts represent something different. They're the one place where fairness is supposed to be protected, where rights are supposed to be restored, where the vulnerable are supposed to be protected by law. Recording restrictions in courts aren't about privacy preferences. They're about ensuring justice is actually possible.

Yet as surveillance technology becomes more seamless, more invisible, more integrated into everyday objects, that distinction weakens. If recording is normal everywhere else, why not in court? If I have a camera in my glasses for legitimate reasons, why can't I wear them in a courthouse?

These are reasonable questions. They're also dangerous questions, because they ignore why courts specifically need to remain recording-free.

The smart glasses issue forces a larger conversation: which spaces should be protected from recording, and how do we maintain those protections as technology makes recording invisible?

The answer isn't "no recording anywhere." Recording is valuable for transparency, documentation, and creating records. But some spaces need to remain recording-free for fairness, safety, or privacy to be possible.

Courts are one such space. So are jury deliberation rooms, victim counseling sessions, and certain medical offices. The question is whether society can maintain recording-free spaces when the technology to record is disguised as eyewear.

Device detection and privacy concerns are the most severe challenges in enforcing smart glasses restrictions in courtrooms. Estimated data.

Practical Guidance: What Happens If You're in Court

If you're involved in court proceedings, understand the recording landscape.

Federal courts: Assume recording is banned entirely. Don't bring smart glasses, don't record on your phone, don't use any device capable of capturing audio or video. The rule is absolute.

State courts: Rules vary. Some states allow media recording under specific conditions. Most states prohibit it for regular people. Check the specific court's local rules before attending. If you're uncertain, ask the court clerk.

If you're wearing smart glasses or similar devices: Expect to be asked about them. If you're wearing them for medical reasons (vision correction), be prepared to explain. Better yet, wear regular glasses or contact lenses if possible.

If you see someone recording: Report it to a court marshal or bailiff immediately. Describe what you observed and where. Let the court handle it. Don't confront the person yourself.

If you're a defendant or witness: Understand that despite recording bans, someone might still record. This shouldn't affect your behavior, but it's good to be aware. Testimony is part of the record regardless of whether someone videos it.

If you're a juror: Assume anything you say or do in court might be recorded, regardless of rules. This doesn't mean you should change your behavior, but awareness is important. If you're selected for jury duty, follow all court instructions about electronic devices completely.

If you're an attorney: Advise clients about the recording risk. Discuss with judges how to protect witnesses and victims. If smart glasses are present, raise it with the court immediately. Courts are grateful for attorneys who help enforce the rules.

The Future: What Happens Next

The trajectory is becoming clear. Smart glasses adoption will accelerate. More courts will issue bans. Enforcement will remain difficult. Legislators will scramble to update laws. Technology will continue evolving.

By 2027, we'll likely see:

- Explicit state laws addressing smart glasses in courtrooms across most states

- Federal rule amendments adding wearable devices to the recording ban

- Technological detection systems in major courthouse entrances

- A few high-profile prosecutions for courtroom recording violations

- Manufacturer built-in safeguards in smart glasses (though limited effectiveness)

- Ongoing cat-and-mouse games as technology gets better at hiding recording

By 2030, the landscape might stabilize into something like:

- Clear, specific smart glasses bans in all courtrooms

- Detection technology as standard security infrastructure

- Criminal penalties for violations that actually deter most people

- A small but persistent minority of people attempting unauthorized recording

- International cooperation on standards for recording-free spaces

- A new generation of even more sophisticated hidden recording technology

The honest conclusion: the courtroom recording problem won't be "solved." It will be managed, minimized, and adapted to. Each technological advance in recording will require new enforcement approaches. This is the ongoing cost of living in a world where recording technology is invisible.

The question isn't whether smart glasses will eventually disappear from courtrooms. The question is what we're willing to sacrifice in privacy, fairness, and judicial process to accommodate them.

Implications for Different Stakeholders

For Judges: The smart glasses issue is becoming a regular part of courtroom management. Judges are increasingly including explicit smart glasses warnings in their pre-trial instructions. Some are asking lawyers to confirm their clients and teams aren't wearing recording devices. The burden of enforcement is falling on judges, which takes time away from actual judicial work.

For Attorneys: Lawyers need to understand the rules in each jurisdiction they practice in. They also need to advise clients and opposing counsel about the risks. In some cases, the smart glasses issue becomes relevant to discovery—if someone recorded proceedings, that recording might be discoverable evidence. Smart glasses create new procedural complications.

For Defendants: Being recorded in court could affect outcomes. If a recording of testimony is distributed online, it might bias future witnesses or jurors. Defendants have an interest in preventing courtroom recording, even though they themselves might be tempted to record (which would be a terrible idea).

For Victims and Witnesses: The stakes are highest here. Recording jeopardizes safety, privacy, and fairness. Victim advocacy groups are pushing hard for strong smart glasses bans and enforcement.

For Jurors: Jurors have an interest in deliberating freely without awareness of being recorded. They also have an interest in maintaining the integrity of the jury system, which depends on trust and confidentiality.

For Tech Companies: Meta and Apple face regulatory pressure and reputational risk if their products are regularly used for courtroom recording. They have incentives to include safeguards, though those safeguards are always imperfect.

For Technology Companies (Security): There's a growing market for courtroom security technology. Detection devices, geofencing software, and monitoring systems are being developed specifically for courts. This creates a new industry sector.

For Civil Liberties Organizations: This is complicated territory. Civil liberties groups care about both privacy (which favors smart glasses bans) and freedom of information (which favors recording and public access). The tension between these values is real.

Conclusion: A Problem Without Perfect Solutions

Mark Zuckerberg walked into a Los Angeles courtroom wearing Ray-Ban smart glasses, and the incident revealed a fundamental gap between law and technology.

Federal rules written in 1946 ban recording in courtrooms. Those rules made perfect sense when recording meant visible cameras and film equipment. They still make sense—the underlying principle is sound. But the technology has outpaced the law.

Smart glasses aren't going away. Seven million pairs sold in 2025. Apple's entering the market. Adoption will accelerate. In five years, smart glasses will be as common as regular eyewear in some demographics.

Courts are adapting as fast as they can. Some jurisdictions have issued bans. Others are considering technological solutions. Legislatures are drafting new laws. But the solutions are all incomplete. You can ban smart glasses, but enforcement is nearly impossible when the device looks like regular eyewear. You can install detection technology, but smart glasses can be dormant and hard to detect. You can increase penalties, but penalties only matter if you catch people.

The real issue is that smart glasses represent a category of technology that previous legal frameworks didn't account for: recording devices that are indistinguishable from non-recording devices, that can be activated without external indication, that capture everything from the wearer's perspective.

This category of technology will only expand. After smart glasses come smart contact lenses. Then embedded recording technology. Then devices we haven't imagined yet that are even less obvious.

Courts will adapt. They'll develop new procedures, new technologies, new rules. Victims and witnesses will be protected more carefully. Some courtrooms will become recording-free zones with serious enforcement mechanisms. Others will accept limited recording under strict conditions.

But the tension between technology and legal protection is now permanent. For every advance in detection, there's an advance in hiding recording. For every rule issued, there's a gray area that clever people can exploit. For every enforcement mechanism, there's a technical workaround.

The Zuckerberg incident wasn't the end of the story. It was the beginning of a much longer story about how courts maintain fairness and protection in an age when recording is invisible and everywhere.

The glasses are here. The recordings are happening. The question is what we do about it.

FAQ

What exactly are Meta Ray-Ban smart glasses?

Meta Ray-Ban smart glasses are eyewear that combines a 12-megapixel camera, AI processing, Bluetooth connectivity, and voice commands. They can record video, stream content, identify objects, translate languages, and search the internet. They look like regular designer sunglasses but contain sophisticated recording and computing technology.

Why are smart glasses specifically problematic in courtrooms?

Smart glasses are problematic in courtrooms because they can record proceedings without obvious detection. Traditional recording devices are visible and can be prohibited. Smart glasses look like regular eyewear, making them nearly impossible to identify or distinguish from legitimate medical or vision correction devices. Someone wearing them could document an entire trial, capture juror reactions, record witness testimony, or photograph victims without anyone knowing.

What is Federal Rule 53, and how does it apply to smart glasses?

Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 53, established in 1946, prohibits recording and broadcasting of criminal proceedings in federal courts. The rule was written for film cameras and audio recorders, not wearable technology. Courts are interpreting the rule's underlying principle to apply to smart glasses, but the rule's language doesn't specifically address wearable devices, creating ambiguity about enforcement.

Which courts have banned smart glasses specifically?

The U. S. District Courts for the District of Hawaii and the Western District of Wisconsin have issued explicit smart glasses bans. The Forsyth County Court in North Carolina banned smart glasses in 2024. Colorado's District Court is considering a ban. Many other courts are updating local rules to address wearable recording devices, though not all specifically name smart glasses.

How do judges enforce smart glasses bans if they look like regular glasses?

Judges struggle to enforce smart glasses bans because the devices are indistinguishable from regular eyewear. Some courts rely on asking people about their glasses during jury selection or pre-trial conferences. Others use device detection technology at entrances. Most depend on peer reporting—if someone observes recording, they alert court officials. But enforcement remains inconsistent and incomplete.

What happens if someone records courtroom proceedings illegally?

Illegal courtroom recording can result in contempt of court charges, fines, and jail time. Some jurisdictions are increasing penalties by making unauthorized courtroom recording a criminal offense rather than just contempt. If the recording is distributed, additional charges for violating witness privacy or distributing protected information might apply. The specific penalties vary by jurisdiction and circumstances.

Can smart glasses manufacturers prevent recording in courtrooms automatically?

Manufacturers could theoretically build geofencing technology into smart glasses that disables recording when the device enters a courthouse location. Some proposals suggest this. But such features raise privacy concerns about location tracking, can be disabled, and require manufacturer cooperation. Currently, no major smart glasses manufacturer has implemented automatic courtroom recording prevention.

How does smart glasses recording differ from someone recording on a smartphone?

Smart glasses recording is harder to detect and prevent than smartphone recording because the camera is integrated into eyewear that might be worn for legitimate medical or vision correction reasons. A person with a phone obviously recording can be spotted and asked to stop. A person wearing smart glasses might be recording while looking like they're simply wearing glasses. The integration into wearable technology makes enforcement nearly impossible compared to discrete recording devices.

What protections do smart glasses bans provide for witnesses and victims?

Smart glasses bans attempt to protect witnesses and victims by preventing recording of their testimony and appearance. Witnesses in sensitive cases—trafficking victims, undercover informants, abuse survivors—depend on anonymity protections. If testimony is recorded and distributed, those protections evaporate. Smart glasses bans aim to prevent this, though enforcement is incomplete.

When will AI smart glasses become mainstream, and how will courts adapt?

Smart glasses adoption is already accelerating. Meta sold 7 million pairs in 2025. Apple is entering the market, which typically accelerates adoption of new wearable technology categories. Courts likely have 2-3 years before smart glasses become so common that enforcement becomes nearly impossible. They're rushing to pass legislation and implement technological solutions before the technology becomes ubiquitous enough to bypass traditional enforcement mechanisms.

Key Takeaways

- Smart glasses represent a new category of recording device that existing courtroom rules don't adequately address.

- The invisibility of the recording technology makes enforcement nearly impossible using traditional security approaches.

- Multiple jurisdictions are issuing bans, but consistency and enforcement remain major challenges.

- Technology adoption is outpacing legal adaptation, creating urgent pressure for legislative updates.

- The problem affects victim privacy, witness protection, jury integrity, and the fundamental fairness of court proceedings.

- No single solution exists; courts will need layered approaches combining rules, technology, and enforcement.

- As smart glasses become more common (7 million sold in 2025), the problem will intensify significantly in coming years.

- Other tech companies entering the market will accelerate adoption and complicate enforcement.

- The tension between technology capability and legal protection is now permanent and will require ongoing adaptation.

Related Articles

- Meta's Metaverse Collapse: Why VR Lost to Mobile and AI [2025]

- Amazfit T-Rex Ultra 2 vs Samsung Galaxy Watch Ultra 2: The Best Outdoor Smartwatch [2025]

- Rubik's WOWCube Review: Can Smart Technology Improve the Classic Puzzle? [2025]

- Meta's Smartwatch 2025: What Malibu 2 Means for Wearables [2025]

- Ring's AI Search Party: From Lost Dogs to Neighborhood Surveillance [2025]

- Edge AI Models on Feature Phones, Cars & Smart Glasses [2025]

![Smart Glasses in Court: The Privacy Nightmare Judges Can't Ignore [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/smart-glasses-in-court-the-privacy-nightmare-judges-can-t-ig/image-1-1771609031650.jpg)