Soft Bank's Massive $33 Billion Power Plant Bet: What It Means for AI and Energy

When Soft Bank announced plans to spend $33 billion on a natural gas power plant, most people's first reaction was probably: why is a tech investor building a power plant?

But if you've been paying attention to the AI boom over the past two years, it actually makes perfect sense. The infrastructure to power artificial intelligence is becoming just as important as the chips themselves. And right now, there's a massive energy crunch.

Here's what's happening: AI data centers are hungry. Incredibly hungry. A single training run for a large language model can consume as much electricity as a small city. Open AI, which is partnering with Soft Bank on the "Stargate" project, needs reliable power. Lots of it. Not the kind you negotiate with utility companies for. The kind you build yourself.

According to reports, Soft Bank subsidiary SB Energy is planning to construct a 9.2 gigawatt natural gas-fired power plant on the Ohio-Kentucky border. If completed, it would be the largest power plant in the United States by capacity. For perspective, that's enough electricity to power approximately 7.5 million homes.

At $33 billion, the project would cost more than recent natural gas plants. That's not a typo. This single facility would cost roughly the GDP of some countries. But let's zoom out and understand why this is happening, what it means for the tech industry, and what the broader implications are for energy, climate, and data center infrastructure.

TL; DR

- Soft Bank's $33B investment in a 9.2 gigawatt natural gas plant represents the largest power plant project in U.S. history

- AI data centers consume massive amounts of power, with major tech companies now considering self-built infrastructure as strategically critical

- Stargate partnership between Soft Bank and Open AI signals a shift toward vertically integrated tech infrastructure

- Energy bottleneck is real, with natural gas turbine shortages and grid capacity constraints limiting AI expansion

- Climate implications are significant, with the plant potentially emitting 15+ million metric tons of CO2 annually

- Timeline could span a decade, making long-term planning and regulatory approval essential

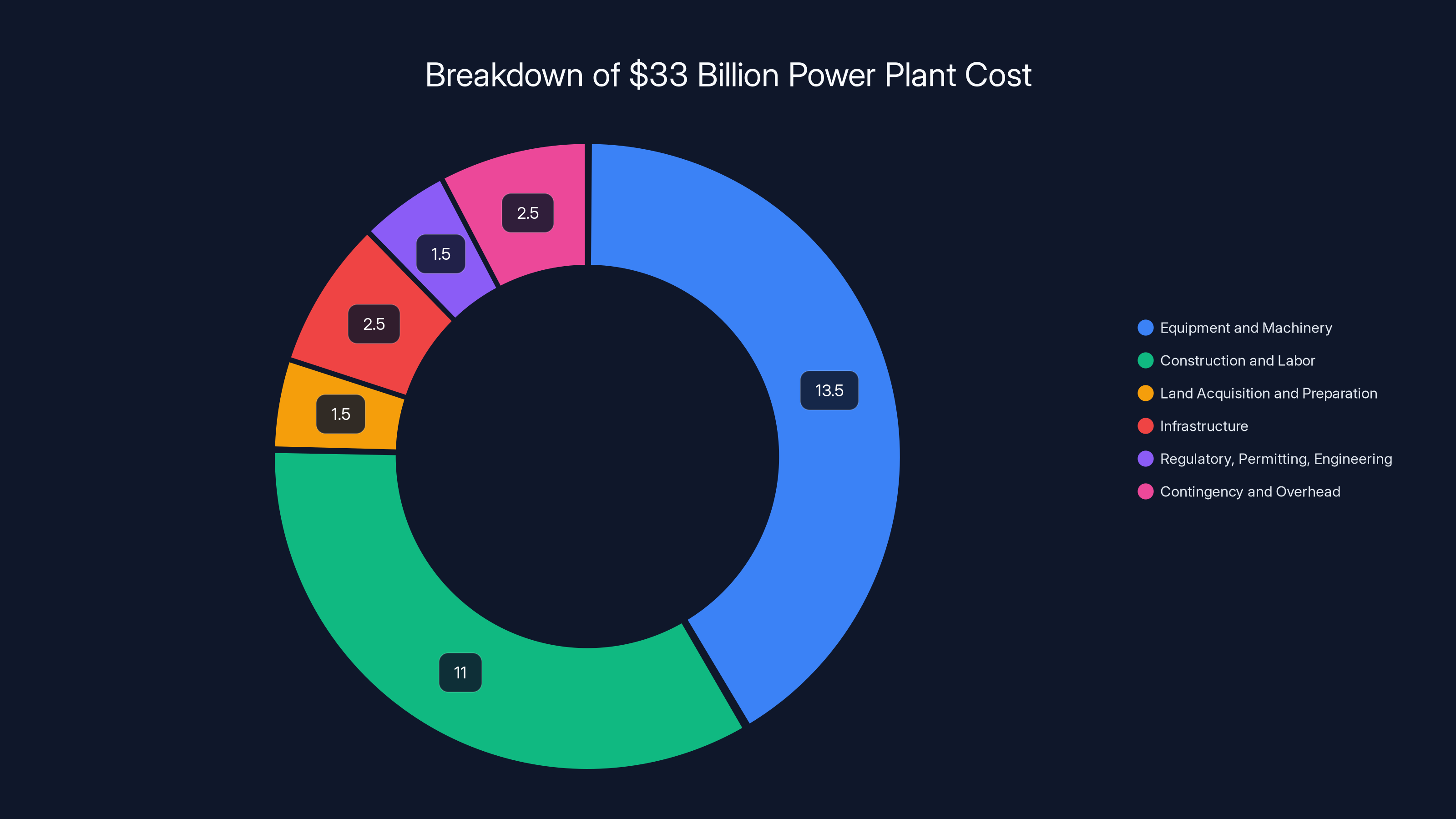

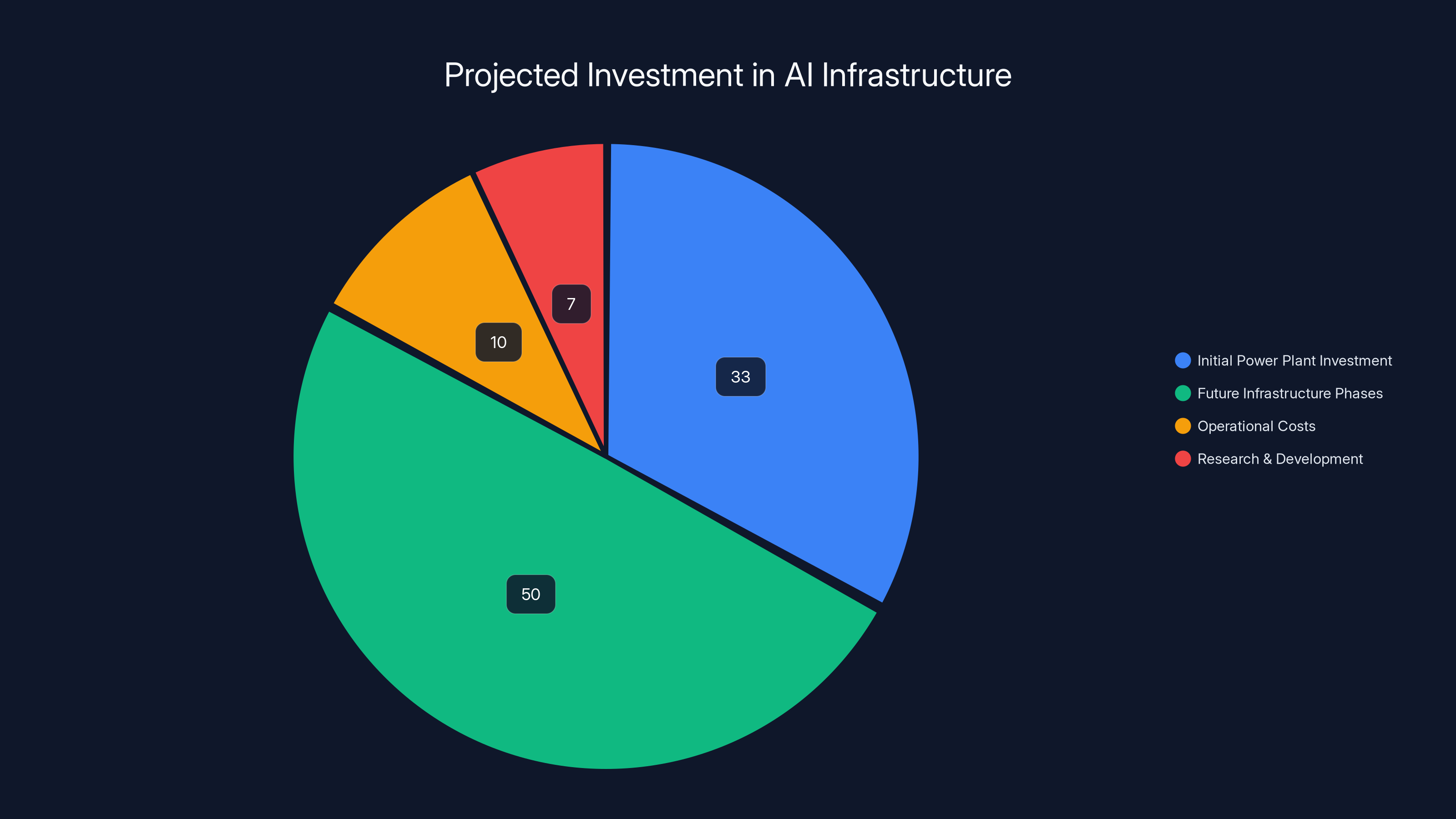

The largest cost components for the

The Energy Crisis in AI: Why $33 Billion Makes Sense

Let's talk about what's actually driving this investment. The AI industry didn't just wake up one day and decide to build power plants for fun. There's a genuine supply constraint problem.

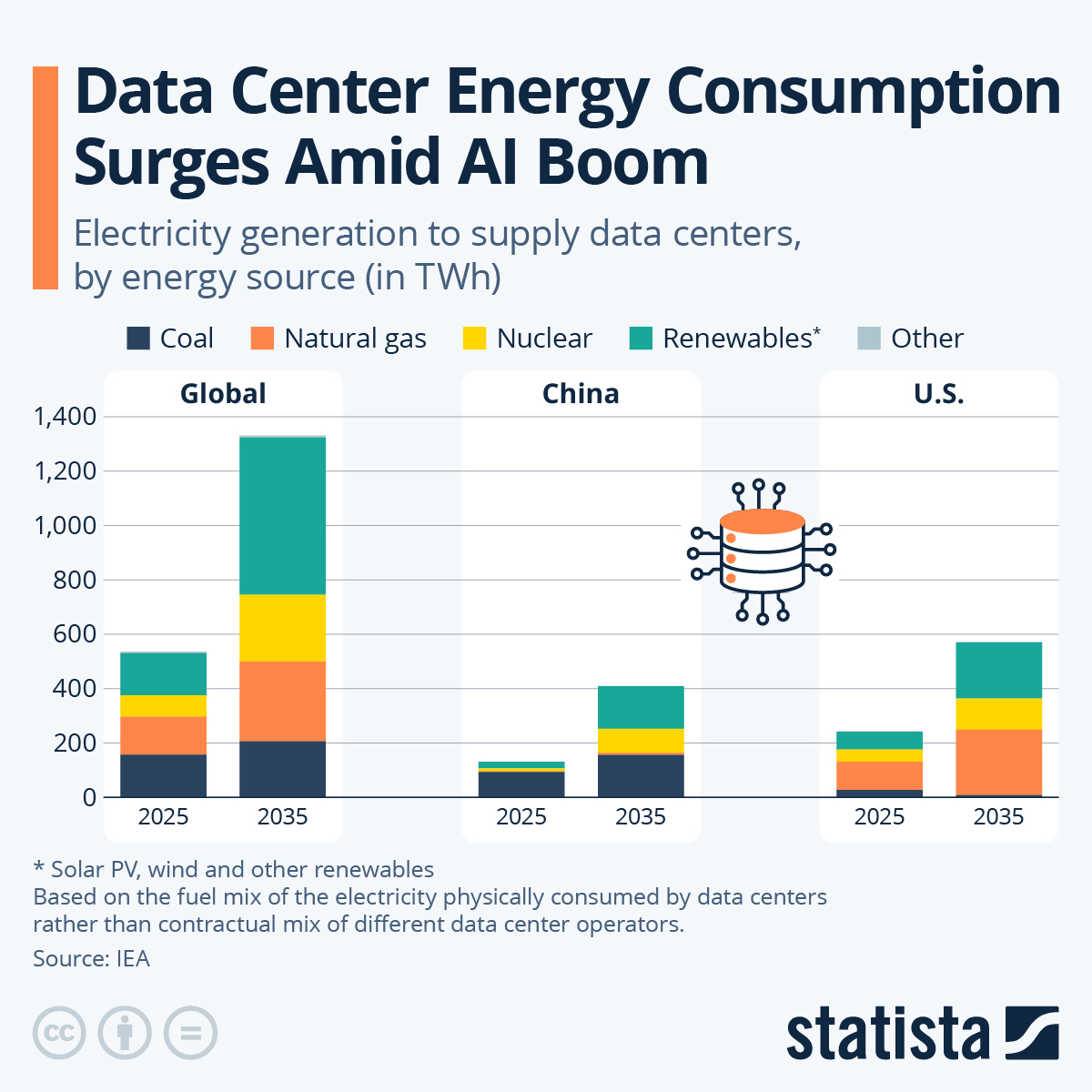

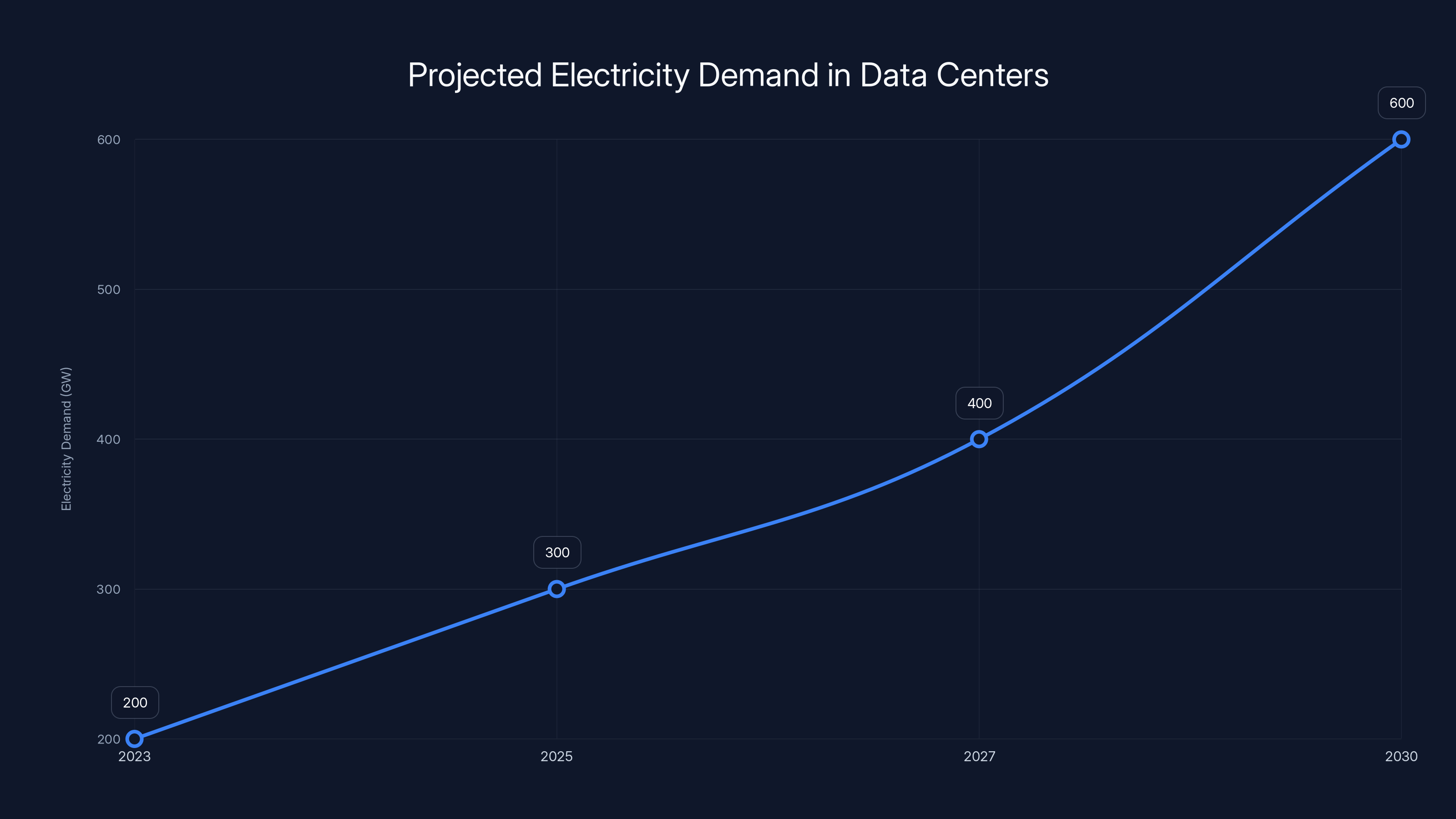

Power consumption in data centers has exploded. When you're training models with hundreds of billions of parameters, electricity becomes your biggest operational expense. The International Energy Agency has warned that data center electricity demand could double or triple over the next decade. That's not hyperbole.

Here's the problem: utility companies can't keep up. The existing electrical grid wasn't designed for the kind of power draw these facilities require. A single hyperscale data center for AI can need 50-100 megawatts of continuous power. When you're running multiple facilities, you're talking about gigawatts. That's not something you can just plug in and hope the grid handles it.

Traditional power plants take years to build. We're talking 5 to 10 years from planning to operational. Natural gas turbines, which are the backbone of these plants, are in short supply globally. There's a bottleneck in manufacturing, supply chains are strained, and everyone from energy companies to tech firms is competing for the same equipment.

So what's a company with $33 billion to spend supposed to do? Build their own.

The Geography Question: Ohio-Kentucky for a Reason

The location choice matters more than you might think. Placing this plant on the Ohio-Kentucky border isn't random.

First, there's the water situation. Power plants need water for cooling. Lots of it. The Ohio River provides abundant water resources, which is essential for a facility of this scale. Second, there's existing infrastructure. The region has natural gas pipeline access, electrical transmission capabilities, and industrial development history. It's not like they're building in a rural area with zero infrastructure.

Third, there's the labor market. Ohio and Kentucky have experienced manufacturing workforces. The plants won't run themselves. You need skilled technicians, engineers, maintenance crews. The region has that talent pool.

Fourth, there's the regulatory environment. Both states have been relatively business-friendly when it comes to major industrial projects. That doesn't mean there won't be environmental reviews and regulatory hurdles, but it's a friendlier landscape than some alternatives.

But here's the real question: will this power stay in the region, or is it destined for data centers elsewhere? Reports suggest the facility might power data centers at General Motors' former Lordstown automotive assembly plant. That facility, which GM abandoned in 2019, is being converted into a data center campus. Everything connects.

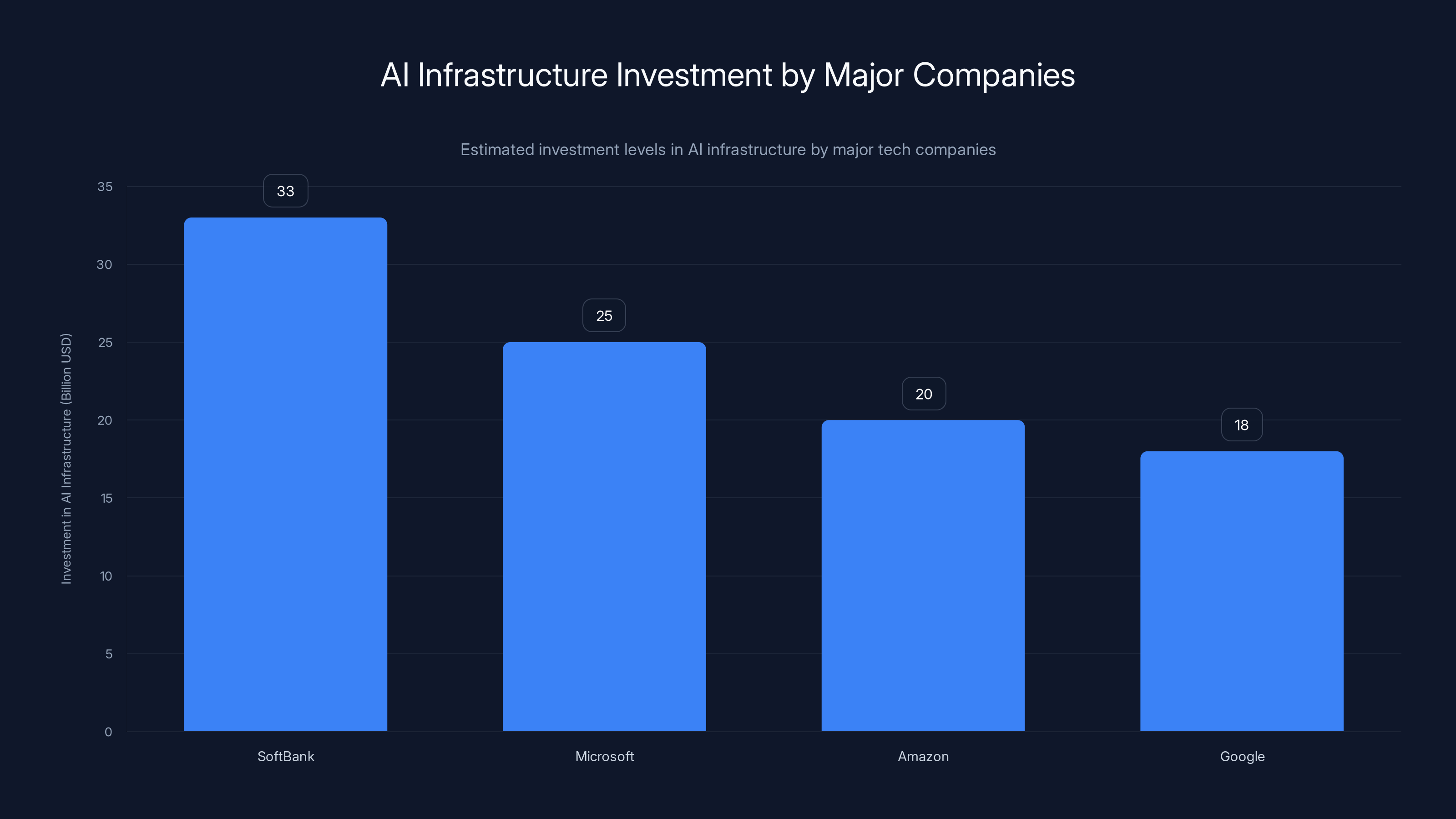

SoftBank leads with an estimated $33 billion investment in AI infrastructure, followed by Microsoft, Amazon, and Google with significant but slightly lower investments. Estimated data.

The Stargate Partnership: Why Open AI Needs Soft Bank's Power

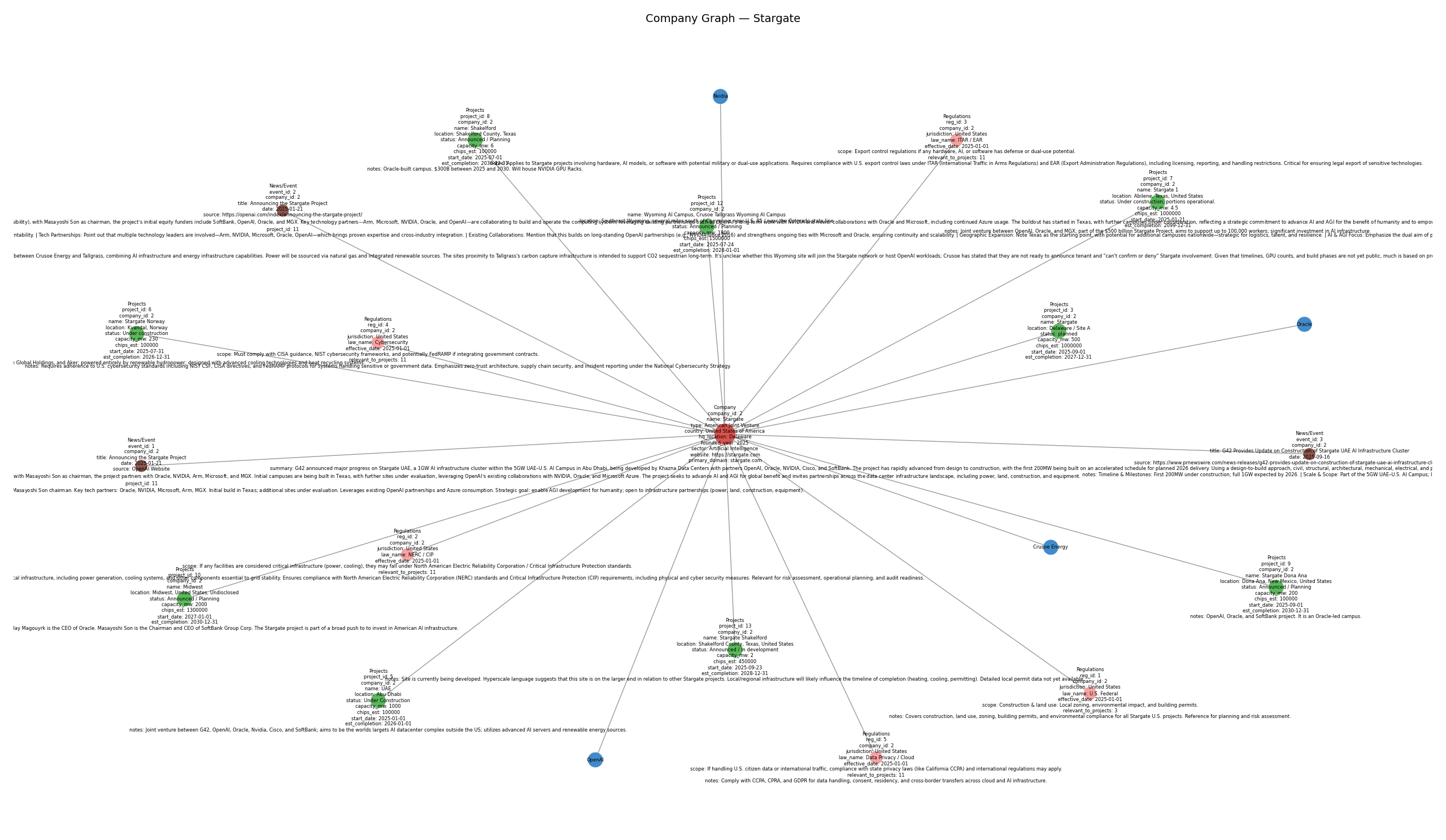

You can't discuss Soft Bank's power plant investment without understanding the Stargate project.

Open AI and Soft Bank announced a major partnership to build massive AI infrastructure. The partnership represents a strategic shift in how AI companies think about infrastructure. Instead of relying entirely on cloud providers like Amazon Web Services or Google Cloud, Open AI wanted its own dedicated infrastructure.

Why? Control. Reliability. Cost optimization. And probably most importantly: independence.

When you're relying on external cloud providers, you're subject to their capacity constraints, their pricing decisions, and their service availability. For a company like Open AI that needs to run massive, continuous AI workloads, that's risky. Even a few hours of downtime could mean millions in lost opportunity.

The Stargate project started as a "proof of concept" at the former GM plant in Lordstown, Ohio. But that's just the pilot. The real vision is bigger. Much bigger.

The $33 billion power plant investment is essentially saying: we're all in on this. We're not building a pilot program. We're building permanent, large-scale infrastructure.

The Role of Soft Bank's Vision Fund

Why is Soft Bank funding this? The company has a history of betting big on transformational technologies. Their Vision Fund has invested in everything from Uber to Alibaba. But power plant construction is a different animal.

For Soft Bank, this is both a financial play and a strategic one. Financially, energy infrastructure can generate stable, long-term returns. A power plant isn't like a tech startup where everything could collapse in five years. It's decades of revenue. Strategically, Soft Bank gains leverage with Open AI and positions itself as a critical player in the AI infrastructure space.

It's also a bet on the geopolitical importance of AI. Countries that control AI infrastructure control the future. By building this capacity in the United States, Soft Bank gains influence over how AI develops. That's worth $33 billion to them.

The Scale: 9.2 Gigawatts of Capacity

Let's put the numbers in perspective, because raw gigawatts don't mean much to most people.

9.2 gigawatts is approximately:

- Enough to power 7.5 million homes

- Equivalent to 60 times the capacity of a small nuclear plant

- More than the total electricity demand of many small countries

- About 12% of the total electricity generating capacity of the entire state of Ohio

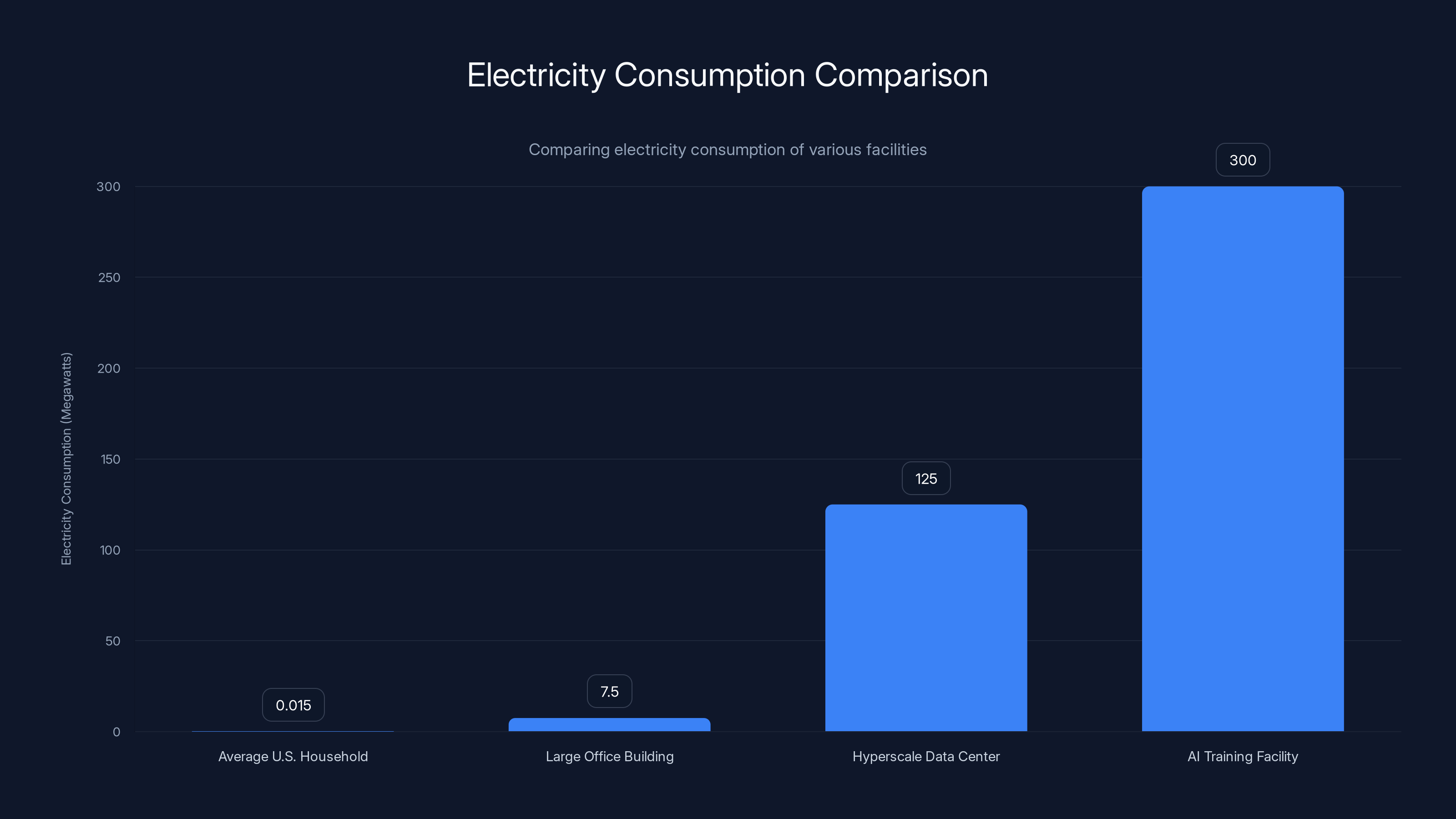

To understand why this matters for AI, consider the electricity consumption profile of different workloads:

Average U.S. Household: 10-15 kilowatts (peak) Large Office Building: 5-10 megawatts Hyperscale Data Center: 50-200 megawatts AI Training Facility (Heavy): 100-500 megawatts

So this single plant could power anywhere from 50 to 200 hyperscale AI data centers, depending on utilization.

But here's the thing: not all of that capacity would run continuously for AI. Data center loads vary. Some hours peak, others are lower. The plant would likely run at 70-80% capacity on average, which is actually optimal for power plant efficiency.

Why Natural Gas and Not Nuclear?

You might be wondering: why not build a nuclear plant? Nuclear is carbon-neutral, reliable, produces massive amounts of power. It checks all the boxes.

The answer is timeline and regulatory complexity. A nuclear plant takes 10-15 years to build and navigates intense regulatory scrutiny. Natural gas plants can be constructed in 5-7 years. For a company racing to meet AI infrastructure demand, time is everything.

Natural gas also has more flexible operational characteristics. You can ramp output up or down more easily than nuclear. For data centers that have variable power needs, that flexibility matters.

But let's be honest: natural gas isn't a climate solution. It's a pragmatic choice that prioritizes speed and feasibility over environmental ideals.

Projected data shows a potential tripling of electricity demand in data centers by 2030, highlighting the urgency of infrastructure investment. Estimated data.

The Cost Factor: Why $33 Billion for One Plant?

Let's talk about why this is so expensive. Power plants aren't cheap, but $33 billion for a single facility is eye-watering even by infrastructure standards.

For comparison, here's what $33 billion could get you:

- A major movie studio franchise (like Star Wars)

- Several entire airlines

- A decent chunk of a country's military budget

- Multiple large pharmaceutical companies

So why is a single power plant that expensive?

First, inflation has hit construction costs hard. Steel, cement, labor, equipment—everything costs more than it did five years ago. The cost of building infrastructure has roughly doubled since 2018.

Second, the shortage of natural gas turbines is real. You need massive turbines to generate this much power, and there aren't many suppliers. When demand exceeds supply, prices spike. Soft Bank would be paying premium prices for equipment that's already hard to acquire.

Third, there's the labor cost. Building a 9.2 gigawatt facility requires thousands of workers across multiple years. You're paying prevailing wages, benefits, safety compliance. Labor for major infrastructure projects has become very expensive.

Fourth, there's the supply chain. Everything from concrete to copper wiring has to be sourced, stored, transported. Project management for something this large is complex and expensive.

Fifth, there's the margin for contingency. Large infrastructure projects always cost more than planned. You budget for overruns.

Breaking down the cost:

- Equipment and machinery: ~$12-15 billion (turbines, generators, controls)

- Construction and labor: ~$10-12 billion

- Land acquisition and preparation: ~$1-2 billion

- Infrastructure (roads, water systems, electrical connections): ~$2-3 billion

- Regulatory, permitting, engineering: ~$1-2 billion

- Contingency and overhead: ~$2-3 billion

These are rough estimates, but they show how the number breaks down.

Who Pays: The Cost Allocation Question

Here's where it gets interesting legally and financially. Who actually bears the cost of this power plant?

Traditionally, utility ratepayers shoulder the burden for new generation capacity. You've probably seen rate increases justified by "infrastructure improvements." But this is different. This isn't a traditional utility project.

Soft Bank is building this privately. That means Soft Bank is taking the financial risk and the capital burden. However, they'll need to recover that investment somehow. If the plant sells power to the grid or to external customers, the revenue model is clear: sell electricity at market rates.

If the plant is dedicated to Open AI and other partners, it's a different story. Soft Bank might negotiate long-term power purchase agreements where Open AI agrees to pay fixed rates for guaranteed capacity. That de-risks the investment for Soft Bank.

But here's the nuance: if the plant connects to the grid, then ratepayers might eventually feel the impact through energy prices. Markets adjust. If a major new power supply comes online, it affects pricing across the region.

Timeline: A Decade or More?

Here's the reality check that nobody likes to talk about: this thing might not be operational for 10 years.

Why so long? Let's walk through the phases:

Phase 1: Planning and Engineering (1-2 years) Soft Bank and partners need to finalize designs, conduct environmental assessments, engineer every system. This isn't just drawing blueprints. It's thousands of pages of specifications.

Phase 2: Permitting and Regulatory Approval (2-4 years) This is the killer timeline. You need permits from state and federal agencies. Environmental review takes forever. Tribal consultation (if applicable). Water rights negotiation. Grid integration approval. All of this happens in parallel, but it's still years of bureaucracy.

Phase 3: Land Acquisition and Site Preparation (1-2 years) Acquiring property, clearing it, preparing infrastructure for construction.

Phase 4: Construction (3-5 years) Actual building. This is the most visible phase, but it's far from the first.

Phase 5: Testing and Commissioning (6-12 months) You don't just flip a switch on a power plant. You test every system, scale up gradually, handle problems.

That's easily 7-10 years in the best case scenario. And that's assuming no major regulatory setbacks, no community opposition strong enough to delay permits, no supply chain disasters.

In reality? This plant might not produce power until 2033 or 2034.

That's a problem if you need that power now. So what's the interim solution? Data centers will continue using grid electricity and renewable energy sources. Companies will build smaller facilities that can come online faster. The race continues, but the finish line keeps moving.

Natural Gas Turbine Shortage: The Real Constraint

The most overlooked constraint is the turbine supply problem.

There are only a handful of companies in the world that manufacture utility-scale natural gas turbines. General Electric makes some. Siemens makes some. Mitsubishi Power makes some. That's basically it.

Right now, there's a global backlog. Everyone from energy companies to data center operators is trying to order turbines. Lead times are stretching to 3-4 years just for manufacturing and delivery. Soft Bank would need to reserve turbines years in advance, and even then, securing all the equipment they need is a risk.

This is why the timeline is so long. It's not primarily regulatory or construction—it's equipment availability.

AI training facilities consume significantly more electricity than other types of facilities, highlighting the massive energy demands of AI infrastructure.

Environmental Impact: The Carbon Elephant in the Room

Let's address the climate impact directly, because it's the biggest legitimate criticism of this project.

A 9.2 gigawatt natural gas power plant running at capacity produces approximately 15 million metric tons of carbon dioxide per year. For context, that's:

- Roughly equivalent to the annual CO2 emissions of 3 million cars

- About 0.03% of global annual CO2 emissions

- More than the annual carbon footprint of most countries

But wait, it gets worse. These numbers only account for direct combustion. When you include methane leaks from the natural gas supply chain, the climate impact is significantly higher. Natural gas contains methane, which is 80+ times more potent than CO2 over a 20-year period. Leaks throughout the supply chain—from wells to pipelines to facilities—add substantial climate impact.

Total climate impact including methane leakage: potentially 30-40 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent annually.

That's substantial. Over a 50-year operational lifetime, this single plant would contribute roughly 1.5-2 billion metric tons of CO2 equivalent to the atmosphere.

The Renewable Energy Counter-Argument

Here's where Soft Bank (and Open AI) would push back: the alternative is worse.

If this power came from a typical grid mix with coal and natural gas, it would have even higher emissions. Natural gas is cleaner than coal. If Soft Bank and Open AI were forced to use existing grid power, some of that power would come from dirtier sources.

Additionally, Soft Bank could theoretically combine natural gas with renewable energy. Run the plant at partial capacity, with the difference made up by wind and solar power purchases. That's not what's being proposed currently, but it's technically possible.

The broader argument is: AI is going to happen. Compute will be deployed. The choice isn't between AI and no AI. It's between AI powered by this plant or AI powered by whatever existing grid power. From that perspective, a dedicated natural gas plant might actually be more efficient and lower-carbon than relying on a mixed grid.

But that's a convenient argument. The real truth is: you could have natural gas with heavy renewable integration. You could push for carbon capture and storage (CCS). You could use hydrogen instead of natural gas. You could explore advanced nuclear. There are other options that Soft Bank isn't pursuing, presumably because they're more expensive or less proven.

Grid Integration: How Does the Power Get Delivered?

Building a power plant is only half the challenge. Getting that power to where it needs to go is the other half.

A 9.2 gigawatt facility would need to connect to the electrical grid through high-voltage transmission lines. These lines carry power at 138,000 volts or higher to minimize loss. Building new transmission infrastructure is almost as expensive and time-consuming as building the plant itself.

The facility would likely connect to the regional transmission operator that manages the Ohio-Kentucky-Pennsylvania area. That's PJM Interconnection, one of the largest grid operators in North America. Any new major power source needs to be studied for grid stability and integrated with existing infrastructure.

This involves:

- Impact studies: How does this plant affect voltage stability, frequency response, fault tolerance?

- Transmission upgrades: Existing lines might need upgrades to handle the power flow

- Interconnection agreements: Legal and technical agreements defining how the plant integrates

- Ancillary services: The plant needs to provide reactive power, frequency support, etc.

These aren't trivial engineering challenges. They require coordination across multiple utility companies and regulatory bodies.

Local Transmission: Getting to Data Centers

If the power is going to data centers at the Lordstown site, that's actually simpler. The plant and data center campus would be in the same region, potentially even co-located. Local transmission is just a matter of running cables from the plant to the facility.

But if the power is serving the broader grid or multiple data centers across different regions, high-voltage transmission becomes essential.

There's also a reliability question: what happens if the transmission line fails? Data centers can't tolerate extended outages. So you'd need redundant transmission paths, backup systems, and local generation capacity. This adds complexity and cost.

The Stargate project is expected to be the largest AI infrastructure investment in history, with an initial

The Competitive Landscape: Other Companies Building Infrastructure

Soft Bank isn't the only company betting huge on AI infrastructure. This is becoming an industry-wide shift.

Microsoft has been investing heavily in data center infrastructure, recently partnering with nuclear energy companies to explore nuclear-powered data centers. Amazon announced similar plans. Google is expanding its internal energy infrastructure.

What's happening is a shift from outsourcing infrastructure to building it in-house. Cloud providers realized that if they want to maintain control over AI development, they need control over the underlying infrastructure. That means power plants, data centers, cooling systems, everything.

This isn't a Soft Bank phenomenon. It's an industry trend. But Soft Bank is being the most aggressive about it.

The Economics: Long-Term ROI

How does a $33 billion investment pay off?

Let's assume the plant runs for 50 years (typical lifetime) and produces power at an average capacity of 70% (realistic for variable load). That's:

If the average electricity price is $50 per megawatt-hour (a reasonable average blending wholesale and long-term contract rates):

Over 50 years, that's

That $33 billion investment returns itself in under 20 years, then generates profit for 30 more years.

Of course, this assumes perfect execution, stable electricity prices, and continuous demand. In reality, prices fluctuate, and there will be downtime for maintenance. But the basic math shows that large-scale power generation is profitable long-term. That's why energy companies are profitable companies.

Regulatory Approval: The Biggest Wildcard

Here's what keeps energy executives up at night: regulatory uncertainty.

This project needs approval from multiple agencies:

- State environmental agencies (Ohio and Kentucky)

- Federal permitting (Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act compliance)

- Regional transmission operator (PJM Interconnection)

- Nuclear Regulatory Commission (probably not, since it's gas, but worth confirming)

- Army Corps of Engineers (water use permits)

- Local zoning boards (if applicable)

Each of these represents a potential point of delay or blocking.

Environmental groups will likely oppose the project on climate grounds. They'll argue that the climate impact is unacceptable and that renewable energy should be prioritized. Depending on the political climate (literally and figuratively), this could gain traction.

Local communities might oppose the project on air quality grounds. Fossil fuel plants produce particulate matter and nitrogen oxides that affect local air quality. If the area already has air quality challenges, a new plant might trigger opposition.

Water rights advocates might oppose the project. Using large quantities of river water for cooling concerns some environmental groups.

On the flip side, pro-development advocates, local labor unions, and potentially state leadership might support the project for job creation and economic impact.

The net outcome is uncertain. In some scenarios, approval takes longer than expected. In others, it moves relatively smoothly.

Political Economy: Who Benefits?

Let's be honest about the political economy here.

Jobs matter politically. A $33 billion project would create thousands of construction jobs over several years, plus permanent jobs once operational. That's attractive to politicians seeking to support their constituents.

But environmental concerns matter too, especially in certain communities and political camps.

The resolution likely involves negotiation. Environmental mitigation requirements might increase costs (carbon capture technology, emission controls). Local hiring requirements might be negotiated. Community benefit agreements might be proposed.

All of this extends timeline and increases total project cost. But it's how large infrastructure actually gets built in a democratic system with environmental and community input.

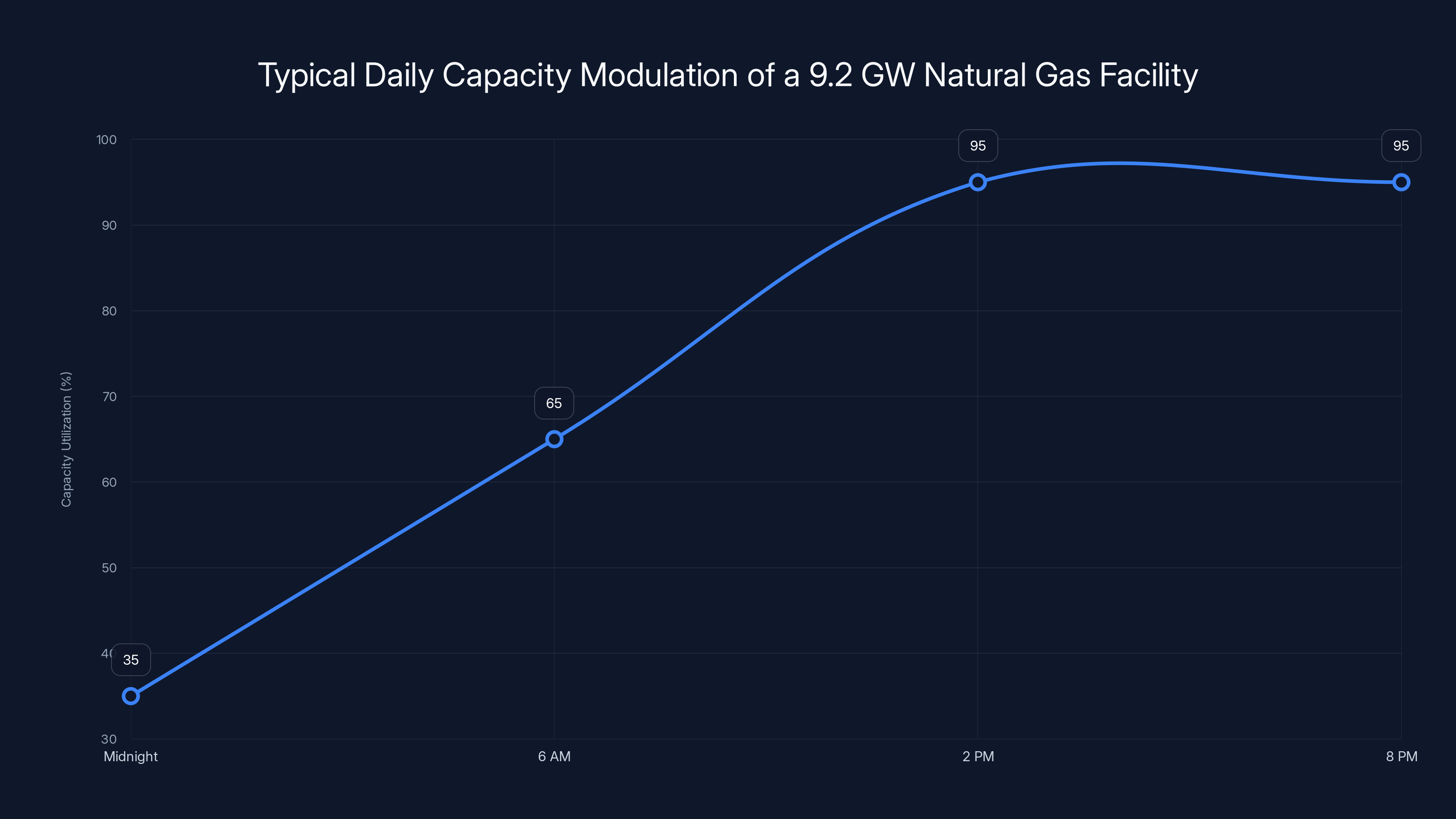

The facility adjusts its output throughout the day, peaking at 90-100% during 2 PM to 8 PM, and reducing to 30-40% during off-peak hours. Estimated data.

Technical Considerations: How Do You Operate This?

Let's get into the nuts and bolts of how you actually operate a 9.2 gigawatt natural gas facility.

You can't run it at full capacity continuously. That's not how power plants work. Demand varies by time of day, season, and dozens of other factors. The plant would modulate output to match demand, or it would be dispatched by the grid operator.

On a typical day, the facility might run at:

- Peak hours (2 PM to 8 PM): 90-100% capacity

- Shoulder hours: 60-70% capacity

- Off-peak hours (midnight to 6 AM): 30-40% capacity

This varies by season. Summer peak is different from winter peak. The plant needs to be flexible enough to adjust output within minutes to match grid demand.

Operating a plant this size requires:

- Operations staff: 50-100 people working shifts

- Maintenance crews: 30-50 people constantly checking and repairing equipment

- Engineering teams: 20-30 people overseeing systems

- Administrative staff: Another 20-30 people

That's easily 150-200+ people employed at the facility on an ongoing basis. Add contractors, and you're looking at 300+ people in the surrounding region depending on the plant.

Control Systems and Automation

Modern power plants use sophisticated control systems to manage output. The plant would have a distributed control system (DCS) that monitors thousands of data points and adjusts operations automatically.

Sensors throughout the plant measure:

- Temperature at hundreds of locations

- Pressure in turbines and pipes

- Vibration on rotating machinery

- Electrical output and quality

- Gas composition and flow rates

Computer systems process this data and make real-time adjustments. If turbine temperature rises, fuel flow is automatically reduced. If electrical frequency drops, output is increased. It's largely automated.

But automation has limits. Major decisions—like startup procedures, major maintenance, emergency responses—require human judgment. So you still need skilled operators.

Financing and Investment Structure

How does Soft Bank actually finance a $33 billion power plant?

Possible structures:

Project Finance: Soft Bank secures loans based on the projected cash flows of the facility. Banks lend

Public-Private Partnership: The government (Ohio or federal) co-invests or guarantees some loan amount, sharing both risk and upside. This is less likely given the partisan nature of energy policy.

Strategic Partnerships: Open AI or other partners co-invest in the project, guaranteeing revenue in exchange for ownership stake. Most likely scenario.

Asset Monetization: Soft Bank builds the plant, then sells it to infrastructure funds or utilities while maintaining operational control. Powers get built this way too.

Most likely, it's a combination. Soft Bank puts in some equity, secures project debt, potentially brings in co-investors, and structures long-term power purchase agreements with Open AI and others to de-risk the revenue side.

The Future: Natural Gas or Transition Fuel?

Here's the philosophical question: is building a new natural gas plant in 2025 responsible?

Argument for responsibility: Natural gas is transitional. It's better than coal, it's dispatchable (unlike solar), and it provides reliable baseload power while renewables scale up. Over 20-30 years, the grid can shift to more renewables. This plant bridges that gap.

Argument against: We should be building renewable infrastructure and storage, not fossil fuels. The climate crisis demands rapid decarbonization. A plant that will operate for 50 years locks in fossil fuels for decades. That's the opposite of what climate science demands.

Reality: It's complicated. We need reliable power now. Renewables can't yet reliably meet all demand. Storage technology is improving but not yet capable of handling multi-day or seasonal storage at scale. So transitional sources like natural gas remain necessary.

But that doesn't mean we should ignore the long-term transition. A responsible version of this project would include:

- Carbon capture and storage (CCS) to reduce emissions

- Commitment to hydrogen fuel conversion in 10-20 years

- Heavy investment in renewable energy to offset carbon

- Regular reassessment to switch to cleaner sources as technology improves

What Soft Bank is proposing doesn't explicitly include those provisions. So it's a pragmatic investment in current infrastructure need, not a climate-responsible solution. The difference matters.

Similar Infrastructure Trends

Soft Bank isn't alone in building energy infrastructure. Similar projects are underway:

Meta's Data Center Power: Meta is investing heavily in data center infrastructure, including renewable power generation. Not at the $33 billion scale, but substantial.

Microsoft Nuclear Partnerships: Microsoft signed deals with nuclear power plants to source clean energy for AI workloads. Different approach, same problem: needing reliable power.

Apple's Renewable Strategy: Apple has been building utility-scale solar and wind projects to power its operations. They're also addressing the power problem, but with renewables.

The pattern is clear: major tech companies are realizing that infrastructure is too important to outsource entirely. Vertical integration is becoming strategically necessary.

The Broader Implications: What This Means for AI Development

When a company spends $33 billion on power infrastructure, it signals something important about its vision.

Soft Bank and Open AI are saying: AI compute is going to be massive, continuous, and strategically critical. We need to control the infrastructure. We can't rely on utilities or cloud providers. So we're building it ourselves.

This has implications:

For AI competition: Countries and companies with reliable, cheap energy have advantages. This plays into the hands of rich investors and established players.

For startups: Smaller AI companies can't compete on raw compute if they don't have access to cheap energy. This could consolidate AI development further around well-capitalized companies.

For energy policy: Governments need to understand that energy infrastructure is now AI infrastructure. Policy decisions about power generation directly affect AI capability.

For climate: If AI compute grows as expected, energy demand grows exponentially. Either we shift to renewables aggressively, or we lock in fossil fuels for decades. The stakes are high.

Timeline and Milestones: What to Watch

If you're following this project, here are the key milestones to watch:

2025-2026: Environmental impact assessment and preliminary permit applications

2026-2028: Regulatory review and approval process

2028-2029: Land acquisition and site preparation begins

2029-2031: Major construction period

2032-2033: Equipment installation and testing

2033-2034: Commercial operation begins

Each of these milestones is subject to delay. One regulatory holdup pushes everything back. One equipment shortage delays construction. These timelines are aspirational.

If I had to guess, I'd expect operational capacity by 2035-2036, not 2034. But I'd be happy to be wrong.

Conclusion: The Power of Ambition

Soft Bank's $33 billion natural gas power plant is audacious, ambitious, and probably necessary given current realities.

It signals that AI infrastructure is becoming as important as AI research. A breakthrough model is worthless without the power to run it. That's the lesson Soft Bank and Open AI have learned.

The project will be complicated. Regulatory approval will be contentious. Timeline estimates will slip. Costs will exceed expectations. That's how large infrastructure works in democratic societies.

But it will probably get built, because the economic case is sound and the strategic importance is clear.

The interesting question isn't whether Soft Bank can pull this off. It's whether they should—whether a 50-year commitment to natural gas is the right infrastructure choice in an era where climate change demands rapid decarbonization.

That's not an engineering question. It's an ethical one. And it's the harder one to answer.

FAQ

What is a natural gas power plant and how does it work?

A natural gas power plant generates electricity by burning natural gas to heat water into steam, which spins turbines connected to generators. The process is similar to coal plants but cleaner, faster to build, and more flexible in output. Modern plants achieve 40-50% thermal efficiency, meaning 40-50 cents of every energy unit becomes electricity, with the rest wasted as heat.

Why does Soft Bank need to build its own power plant instead of buying electricity from utilities?

AI data centers require massive, reliable, continuous power that utilities often can't guarantee. Building dedicated infrastructure gives Soft Bank control over capacity, reliability, and cost. It also provides energy independence—critical when you're competing in AI where power availability directly affects your capability.

How much electricity does an AI data center actually consume?

Hyperscale AI data centers consume 50-500 megawatts depending on size and utilization. Training large language models can draw 100+ megawatts continuously for weeks. That's more power than many small cities consume, which is why AI infrastructure is becoming an energy problem.

What does 9.2 gigawatts mean in practical terms?

One gigawatt equals one billion watts. A 9.2 gigawatt facility produces as much power as approximately 9.2 million kilowatts continuously. To put it in perspective, it could power about 7.5 million homes, or roughly 25-30 major AI data centers. It's among the largest power plants in the world.

How long will it take to build this power plant?

Realistically, 7-10 years from permit approval to operational. Planning and permitting takes 2-4 years, construction takes 3-5 years, and testing takes another 6-12 months. The shortage of natural gas turbines could extend this further if lead times exceed 3-4 years.

What is the environmental impact of this power plant?

Direct emissions would be approximately 15 million metric tons of CO2 annually. Including methane leakage from the natural gas supply chain, total climate impact could reach 30-40 million metric tons CO2-equivalent annually. Over a 50-year operational life, this represents 1.5-2 billion metric tons of atmospheric CO2, equivalent to the annual emissions of several countries.

Who will pay for the electricity from this power plant?

Primarily Open AI and Soft Bank's other data center partners through long-term power purchase agreements. The plant's revenue will come from these contractual commitments, which de-risk the investment for Soft Bank. Some power might be sold to the broader grid, depending on final design.

What regulatory approvals does this project need?

The project requires permits from state environmental agencies (Ohio and Kentucky), federal agencies (EPA, Army Corps of Engineers), the regional grid operator (PJM Interconnection), and potentially local zoning boards. Environmental and community groups will likely challenge the project, extending the approval process.

Could this project be powered by renewable energy instead?

Theoretically yes, but solar and wind can't yet provide reliable 24/7 power at this scale without massive battery storage. Natural gas provides dispatchable power that fills gaps. A hybrid approach using renewables plus natural gas with carbon capture would be more climate-responsible but more expensive and technically complex.

Is building fossil fuel infrastructure in 2025 a mistake?

That's a question with no perfect answer. Natural gas is cleaner than coal and provides reliable power while renewables scale up. But it locks in fossil fuels for 50 years when climate science demands rapid decarbonization. A responsible approach would combine natural gas with aggressive carbon capture, renewable integration, and a timeline to transition to cleaner fuels.

Final Thoughts

Soft Bank's $33 billion power plant investment isn't just a business decision—it's a statement about where the tech industry thinks the future is headed. The company is betting that AI will dominate the next several decades and that reliable, dedicated energy infrastructure is essential to win that race.

Whether that bet pays off depends on too many variables to predict with confidence. But one thing's certain: energy infrastructure is becoming as strategically important as chip technology and software architecture. Companies that control their power supply will have advantages over those that don't.

The project will face challenges. Regulatory approval will be contested. Costs will likely exceed projections. Timeline estimates will slip. That's the nature of large infrastructure.

But in an era where AI development is constrained by compute availability, and compute is constrained by power availability, building massive power infrastructure makes logical sense. It might not be environmentally ideal, but it's strategically rational.

The real question for the next decade won't be whether this plant gets built. It will be whether the energy industry and policymakers can shift toward cleaner alternatives fast enough to meet climate goals while meeting the AI industry's massive power demands.

That's the actual challenge. And it's one that no single $33 billion investment can solve.

Use Case: Managing complex infrastructure projects like this power plant requires automating reporting, stakeholder communication, and document generation—exactly what modern AI platforms excel at.

Try Runable For FreeKey Takeaways

- SoftBank's $33 billion power plant investment reflects a critical industry shift where major tech companies are building dedicated energy infrastructure instead of relying on utilities

- AI data centers consume 50-500 megawatts continuously, creating an energy bottleneck that constrains AI development and requires new power generation capacity

- A 9.2 gigawatt facility would be the largest power plant in the U.S., capable of powering 7.5 million homes or 25-30 hyperscale AI data centers

- The project faces a realistic 7-10 year timeline from permits to operation, with natural gas turbine shortages being a critical constraint on speed

- Annual CO2 emissions would reach 15-40 million metric tons depending on whether methane supply chain leakage is included, raising climate responsibility questions

Related Articles

- AI Climate Claims: Big Tech's Promises vs. Reality [2025]

- Heron Power's $140M Bet on Grid-Altering Solid-State Transformers [2025]

- Blackstone's $1.2B Bet on Neysa: India's AI Infrastructure Revolution [2025]

- Uranium From Seawater: China's Race Toward Infinite Nuclear Fuel [2025]

- Anthropic's Data Center Power Pledge: AI's Energy Crisis [2025]

- New York's AI Regulation Bills: What They Mean for Tech [2025]

![SoftBank's $33B Gas Power Plant: AI Data Centers and Energy Strategy [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/softbank-s-33b-gas-power-plant-ai-data-centers-and-energy-st/image-1-1771518997320.jpg)