Tesla's California Autopilot Confrontation: How Deceptive Marketing Nearly Shut Down Elon Musk's Biggest Market

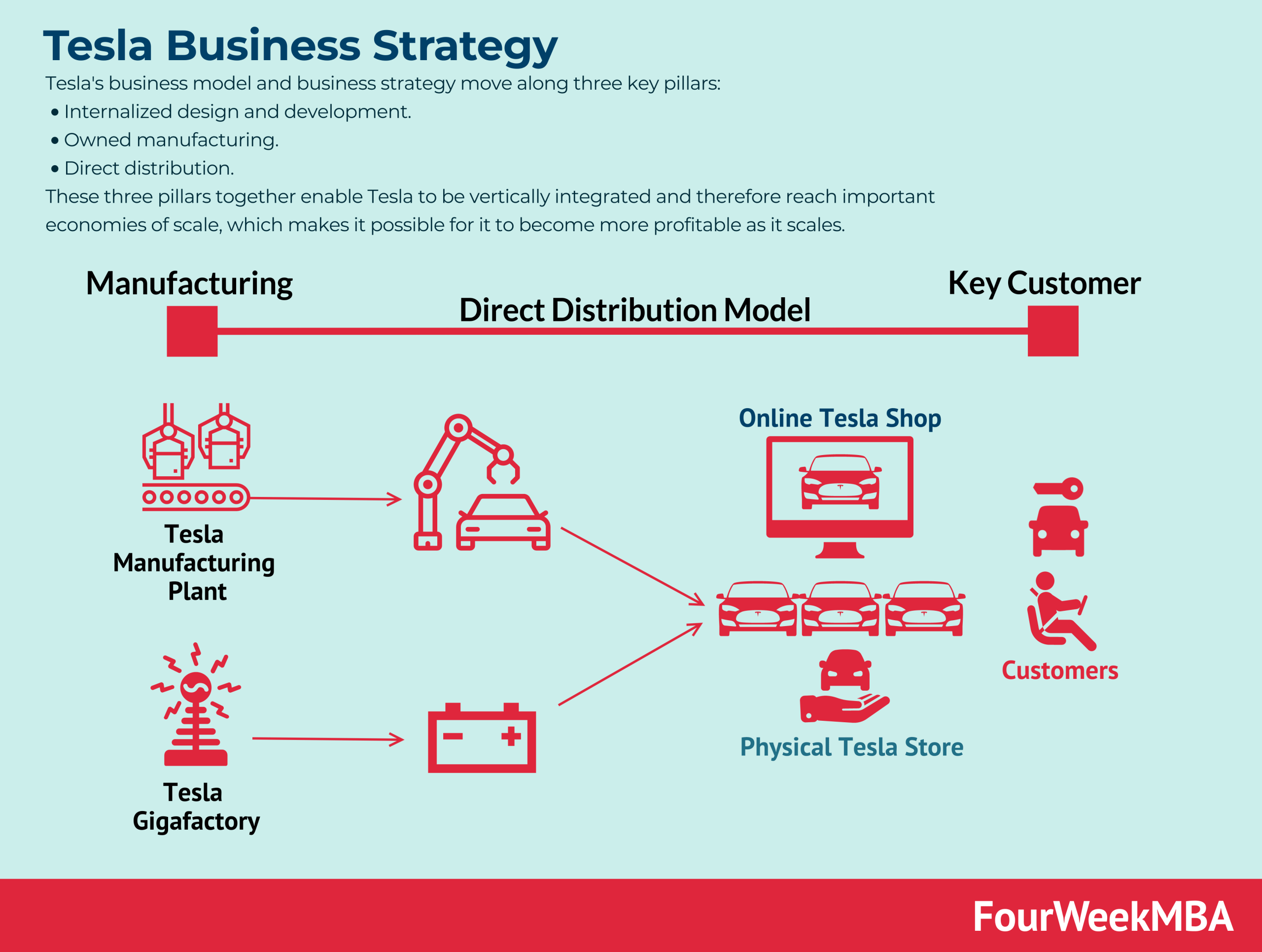

In early February 2025, Tesla narrowly escaped a devastating blow that could have derailed its entire U.S. operations. The California Department of Motor Vehicles announced it would not suspend Tesla's sales and manufacturing licenses in the state, but the path to this reprieve reveals something far more consequential than a simple regulatory win. This wasn't just about terminology or marketing semantics. What unfolded was a three-year legal battle that fundamentally challenged how companies market autonomous driving technology, exposed the gap between what consumers think they're buying and what they're actually getting, and forced Tesla to make a dramatic structural change to its business model.

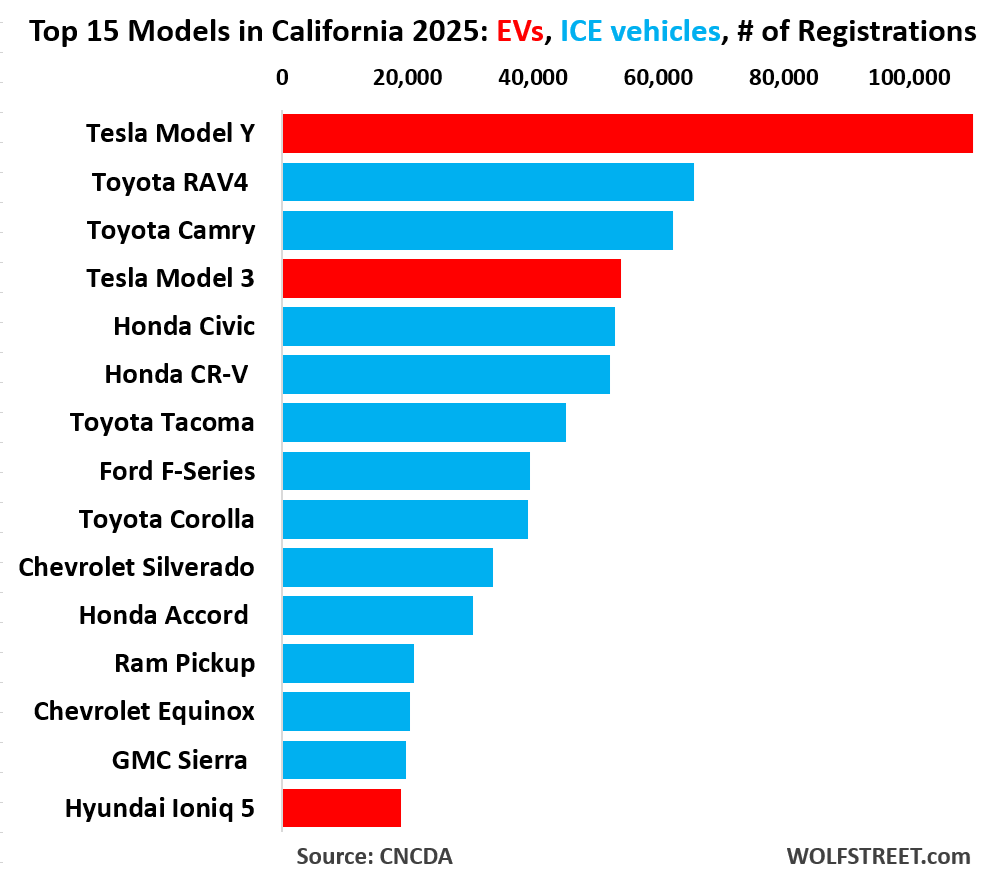

California is Tesla's largest U.S. market by a wide margin. The state accounts for roughly 25% of all Tesla vehicle deliveries in the United States. A 30-day suspension of sales and manufacturing licenses wouldn't just be a fine or a slap on the wrist. It would mean Tesla couldn't sell a single vehicle in California for an entire month. During that period, competitors could capture market share, dealerships would go dark, and Tesla's financial trajectory would take a visible hit. Understanding what led to this precipice requires examining not just regulatory decisions, but also the messy intersection of technology marketing, consumer protection law, and how companies communicate capabilities they don't yet fully possess.

The story didn't start in 2025. It began with a regulatory complaint filed nearly three years earlier, driven by a fundamental disagreement about what the word "Autopilot" actually means.

The Three-Year Regulatory Battle That Forced Tesla's Hand

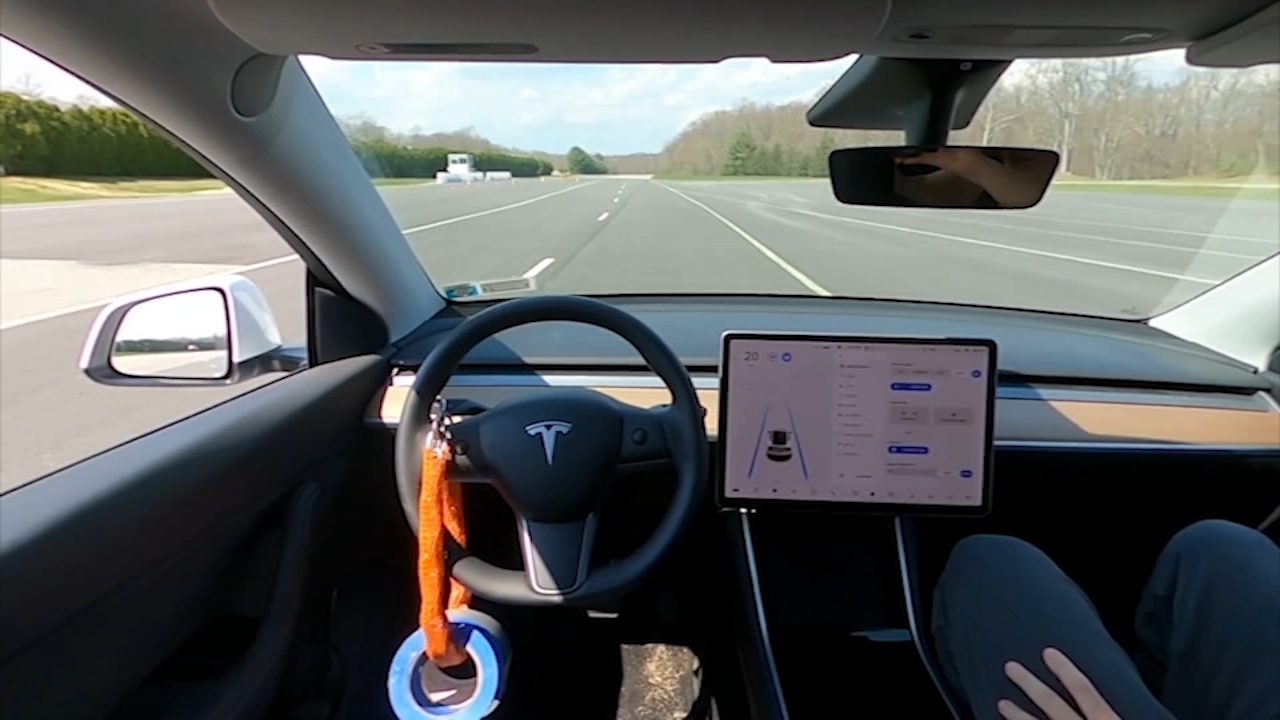

Back in November 2023, the California DMV filed formal accusations against Tesla. The central charge was deceptive marketing. Tesla had been using the term "Autopilot" to describe its basic advanced driver assistance system, and the term "Full Self-Driving" to describe its more capable driver assistance software. The DMV argued these terms systematically misled consumers about what the systems could actually do.

This wasn't a new complaint. Consumer advocates had been raising concerns about Tesla's naming conventions for years. The problem with calling something "Autopilot" is that it conjures images of commercial aircraft, where autopilot genuinely can handle complex navigation with minimal human intervention. When applied to a car system that legally requires constant driver attention and intervention, the name becomes misleading by its very nature. You can't divorce a word from its cultural meaning and expect consumers to interpret it literally.

The DMV's position was unambiguous: these terms violated California's consumer protection statutes. They distorted the capabilities of Tesla's advanced driver assistance systems and set unrealistic expectations in consumers' minds. A person who bought a Tesla expecting it to drive itself would eventually discover reality didn't match the marketing. That gap between expectation and reality constituted deception.

Tesla's initial response showed the company wasn't ready to back down. The company modified how it marketed "Full Self-Driving," rebranding it as "Full Self-Driving (Supervised)" to emphasize that driver supervision was still required. This was a meaningful concession. But Tesla held firm on Autopilot. The company continued using that term in California marketing materials, arguing it accurately described the system's capabilities within the engineering community, even if it sounded more sophisticated to consumers.

This refusal to budge on terminology was the critical mistake. It kept the case alive and escalated it beyond simple regulatory negotiation.

Tesla's shift from a one-time

When An Administrative Judge Sided With The State

Because Tesla refused to fully comply voluntarily, the DMV referred the case to an administrative law judge at the California Office of Administrative Hearings. This wasn't a minor procedural step. Administrative hearings move faster than civil court but follow rigorous legal standards. Both sides present evidence, testimony, and argument. The judge then issues a formal ruling that carries legal weight.

In December 2024, the administrative law judge ruled in favor of the DMV. The judgment was thorough and unforgiving. The judge agreed that Tesla's use of "Autopilot" was misleading and that the company had violated California law. The recommended penalty was exactly what the DMV had requested: a 30-day suspension of Tesla's sales and manufacturing licenses in California.

Let that sink in. A judge had officially ruled that Tesla was marketing its vehicles deceptively and that the appropriate punishment was to shut down its ability to sell cars in its most profitable state for a full month. The DMV formally agreed with this ruling. The legal machinery had spoken.

But here's where regulatory strategy intersected with practical business reality. Rather than immediately implementing the suspension, the DMV gave Tesla 60 days to comply. This was a lifeline. It was a formal notice that said: you have two months to fix this, or the suspension happens. It wasn't a threat. It was a structured opportunity.

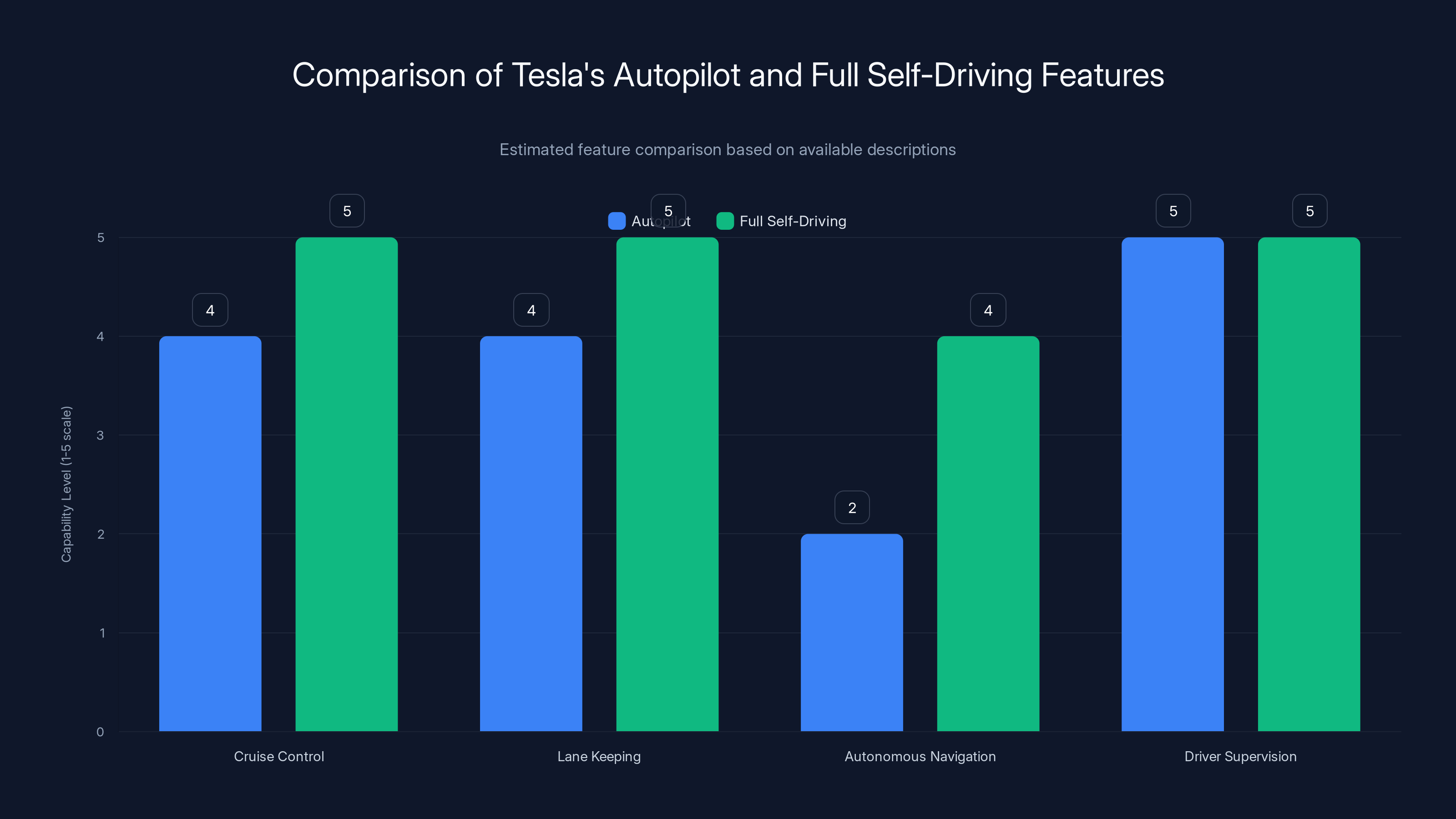

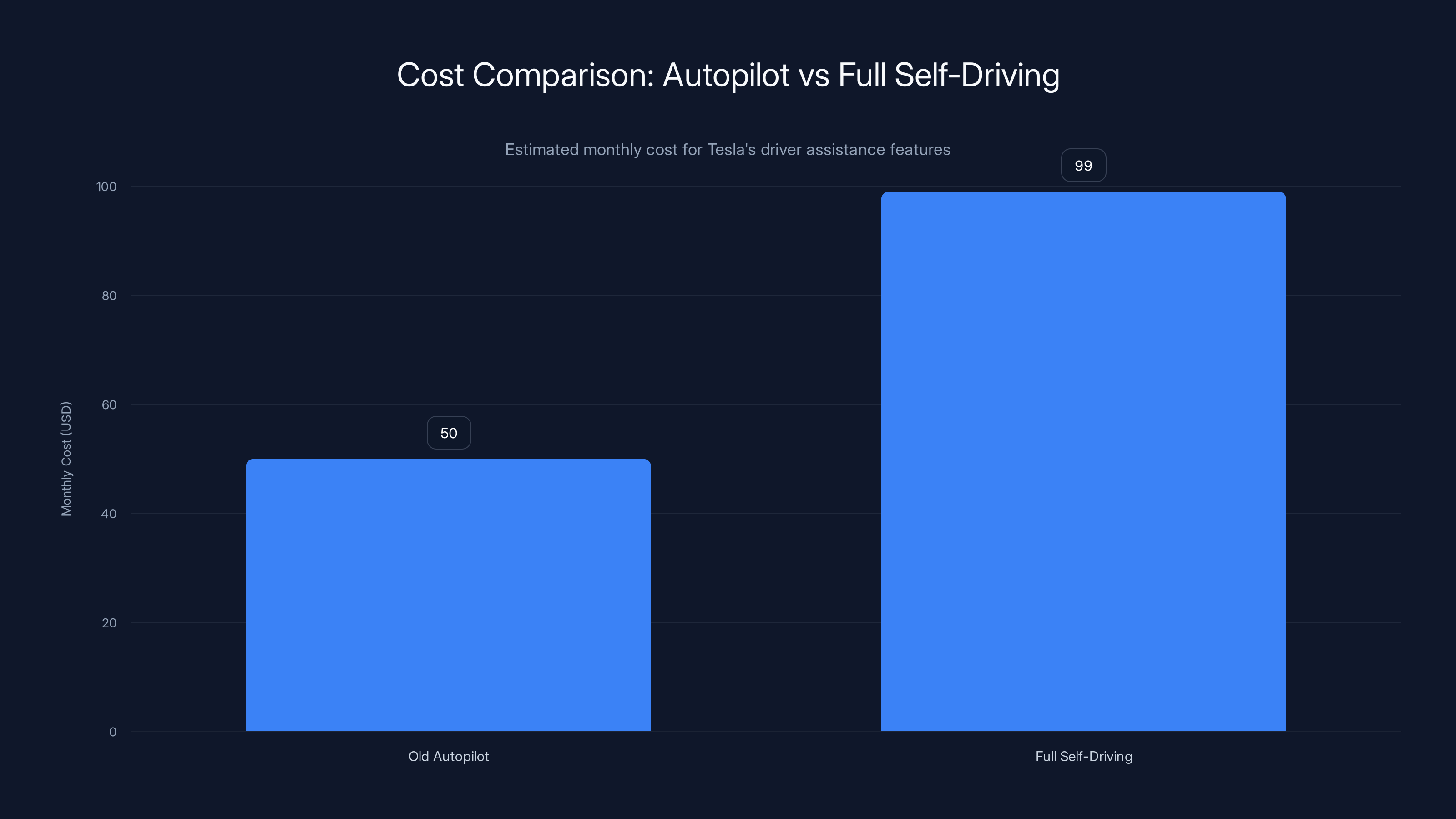

Full Self-Driving offers more advanced features than Autopilot, especially in autonomous navigation, though both require driver supervision. Estimated data.

Tesla's Two-Pronged Compliance Strategy

Tesla responded with unexpected swiftness and comprehensiveness. Rather than doing the minimum required, the company took what appeared to be two coordinated actions designed to satisfy the regulator while also advancing its larger business strategy.

First, in late January 2025, Tesla simply discontinued Autopilot altogether. This was the nuclear option. The company wasn't just changing how it marketed Autopilot. It was eliminating the product category entirely from the U.S. and Canadian markets. No more Autopilot. Gone. Customers who wanted Tesla's driver assistance features would need to purchase Full Self-Driving (Supervised) instead.

This move was brilliant from multiple angles. It solved the regulatory problem completely. If Autopilot doesn't exist, you can't deceive anyone by marketing something that doesn't exist. The DMV's complaint became technically moot. There's nothing misleading about terminology for a product that's no longer sold.

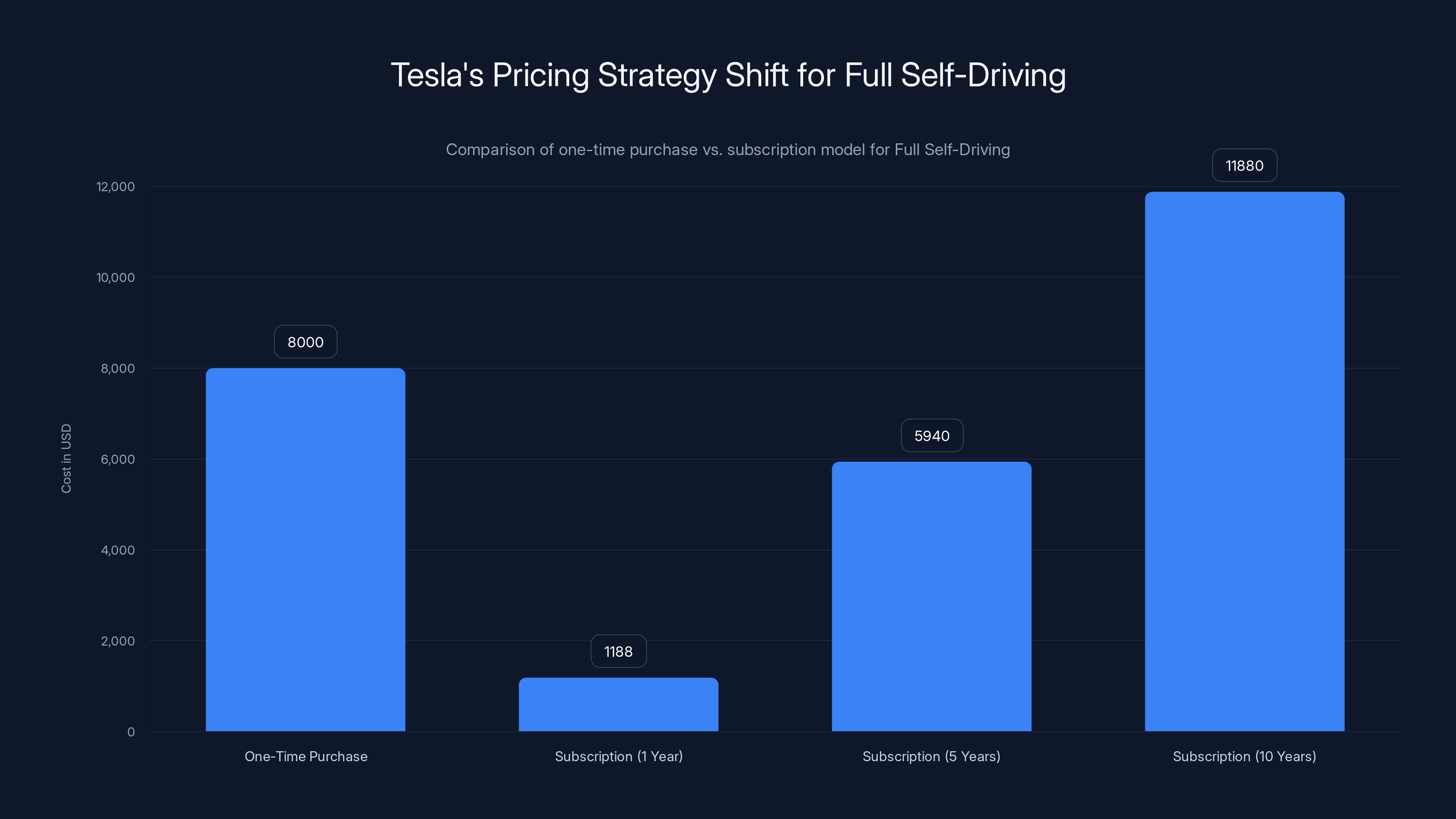

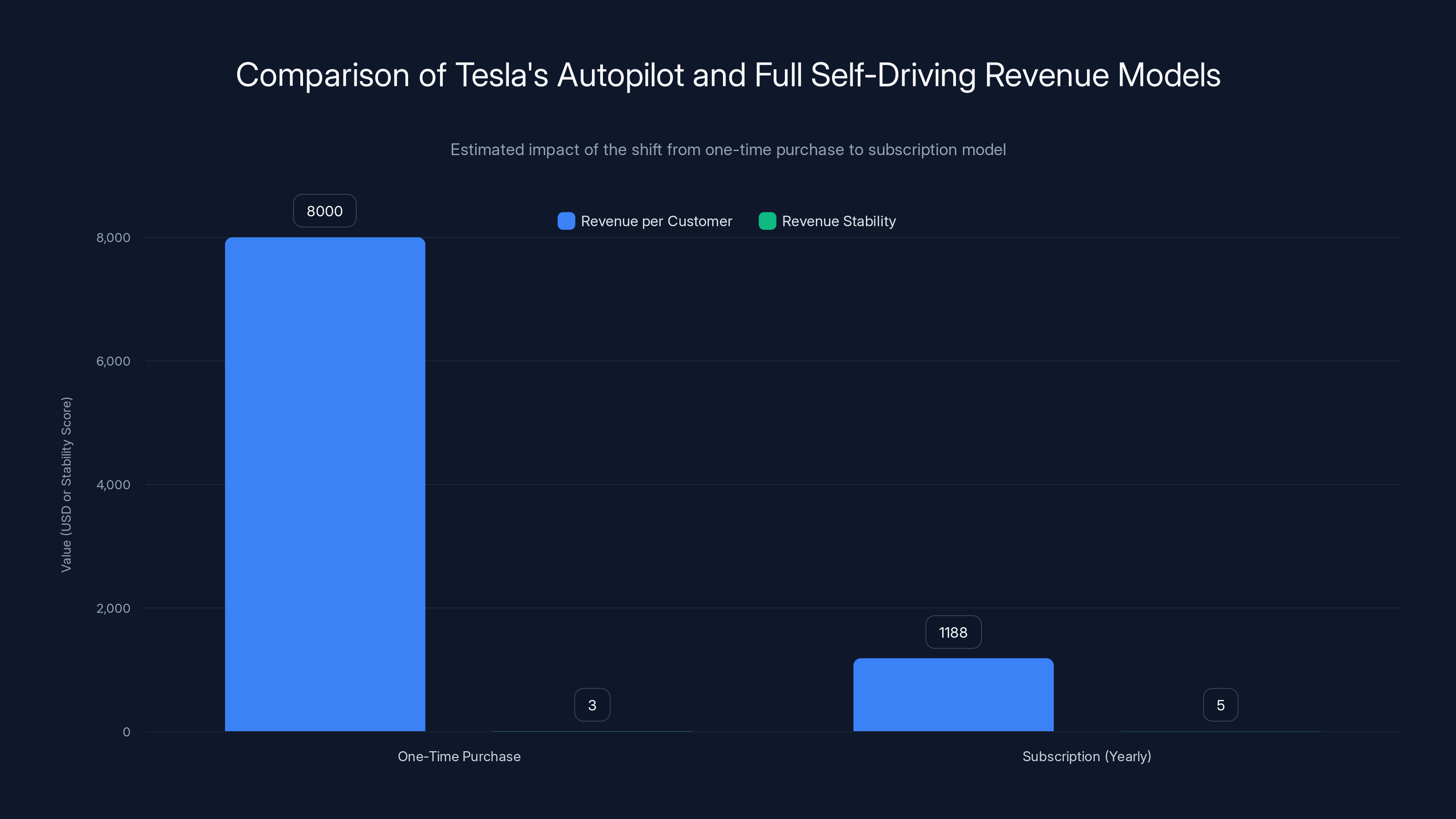

But eliminating Autopilot also served Tesla's broader commercial interests. Autopilot had been a free feature for many Tesla customers. It came bundled with the vehicle purchase. Full Self-Driving, by contrast, is a paid product. Prior to February 2025, Full Self-Driving required an $8,000 one-time purchase fee. This created a purchasing barrier. Even if a customer was interested in the more advanced features, they'd need to pay significantly.

Second, Tesla restructured Full Self-Driving's pricing model. Starting February 14, 2025, the company converted Full Self-Driving from a one-time

The math reveals Tesla's strategic thinking. The old

The Regulatory Victory That Actually Changes Nothing

By early February 2025, Tesla had technically complied with the DMV's requirements. The company was no longer using the term "Autopilot" in California marketing. In fact, it wasn't using the term anywhere in North America because the product had been discontinued entirely. The DMV announced it would not implement the 30-day suspension. Tesla had successfully navigated the regulatory crisis.

But here's the uncomfortable truth: Tesla's compliance didn't actually change what's important about this situation. The regulatory victory is largely cosmetic. Let's examine what actually happened and what it means.

Tesla's driver assistance systems still do the same things they did before. Full Self-Driving (Supervised) operates with identical technical capabilities to what it possessed on February 13, 2025. The discontinuation of Autopilot and the rebranding didn't improve the systems' actual performance or safety. It simply removed the marketing terminology that regulators found misleading.

Consumers still face the same challenge they faced before: understanding what these systems can and cannot do. The terminology has changed, but the fundamental capability gap between what the name suggests and what the system actually does remains. You could argue that "Full Self-Driving (Supervised)" is clearer than "Autopilot," but both names still oversell the technology's autonomy.

This raises an uncomfortable question about regulatory enforcement in technology industries. Did the DMV's action actually protect consumers, or did it just force a marketing adjustment while leaving the core issue unresolved?

The shift from a one-time

Understanding Driver Assistance Versus True Autonomy

To properly evaluate what happened here, you need to understand what these systems actually are. This distinction matters because it's the foundation of the entire regulatory conflict.

Driver assistance systems like Tesla's Autopilot and Full Self-Driving (Supervised) operate within what's called "Level 2" autonomy on the industry-standard six-level autonomy scale. At Level 2, the vehicle can handle certain driving tasks simultaneously, like steering and acceleration, but a human driver must remain fully engaged and ready to take over at any moment. The system is not designed to operate without active driver supervision.

Level 3 autonomy, available in some luxury vehicles, allows the car to make most driving decisions in certain conditions, though human intervention is still required in edge cases. Level 4 is true self-driving with no human intervention needed in most conditions. Level 5 is fully autonomous in all conditions.

Tesla's Full Self-Driving is Level 2 by any realistic technical assessment. The company markets it as offering more capability than Autopilot, which is also Level 2 but with a narrower feature set. But both are fundamentally similar: they assist driving, they don't replace the driver.

The marketing problem isn't really about level designations. It's about consumer psychology. When you call something "Full Self-Driving," people naturally assume it means the vehicle can drive itself fully. They don't think about regulatory autonomy levels. They think about what the words mean in everyday English. And in everyday English, "full self-driving" means the car drives itself without you.

This is the gap that the DMV was trying to address. And by eliminating the Autopilot term and forcing clarification of Full Self-Driving, the regulator was attempting to shrink that gap. Whether it succeeded is debatable.

Why California Matters More Than Other States

Understanding why California was the battleground for this fight requires understanding California's unique regulatory position in the automotive industry. California is the second-largest automotive market in the world, behind only China. It's larger than most countries' entire automotive markets.

Because of this size, California has earned special regulatory authority under the Clean Air Act. The state can set its own vehicle emissions standards, which are often stricter than federal standards. Other states can then choose to follow California's standards or federal standards. This has made California the de facto regulatory trendsetter for the American automotive industry.

Tesla's dependence on California is even more pronounced than the general automotive industry's. The company's primary manufacturing facility is in Fremont, California, in the San Francisco Bay Area. A huge portion of Tesla's workforce is based in California. The company's customer concentration is also disproportionately Californian. Affluent California consumers were early adopters of electric vehicles, and Tesla captured a dominant share of that market.

This means that a 30-day sales suspension in California would have been exponentially more damaging to Tesla than it would be to a traditional automaker. A company like General Motors could absorb a one-month suspension in California by shifting inventory to other states. Tesla doesn't have that flexibility. California is central to its ecosystem.

The DMV understood this. The penalty was calibrated to hurt, and that's why Tesla took it so seriously.

Tesla's subscription model becomes more cost-effective for ownership periods under 7 years compared to the one-time purchase option.

The Business Model Implications of Autopilot's Death

When Tesla discontinued Autopilot, the company wasn't just solving a regulatory problem. It was restructuring its go-to-market strategy for driver assistance features. This restructuring has significant implications for how the company makes money and how customers access its technology.

Under the old model, customers could buy a Tesla vehicle with Autopilot included as a standard feature. This was powerful for sales. Autopilot was a genuine differentiator that helped justify Tesla's premium pricing compared to competing EVs. When you could tell a customer, "Your car comes with advanced driver assistance that evolves over time," it made the purchase more compelling.

Now, all driver assistance capabilities are bundled into Full Self-Driving (Supervised), which is a

But there's a second implication. The subscription model creates recurring revenue. Each active customer paying $99 monthly is a predictable revenue stream. This is exactly what Wall Street values. When Tesla reports quarterly earnings, recurring subscription revenue is weighted heavily by analysts and institutional investors. It's more stable and more valuable as a valuation multiple than one-time purchase revenue.

The regulatory pressure essentially forced Tesla to make a business model change that the company probably wanted to make anyway. The company gets to extract more revenue from customers while solving the regulatory problem. From Tesla's perspective, this isn't really a loss. It's an opportunity.

The Precedent This Sets For Other Automakers

Tesla's experience has immediate implications for how other automakers market their driver assistance systems. Every major automaker is developing advanced driver assistance features, and many are walking the same tightrope between marketing appeal and technical accuracy.

General Motors markets its system as "Super Cruise," which is even more aggressive naming than Tesla's Autopilot. Chrysler has "Intelligent Drive." BMW has "Driving Assistant Professional." Ford has "Blue Cruise." Lexus has "Lexus Safety System 2.5." All of these names have been chosen to sound more capable than what the systems actually do.

The California DMV's action against Tesla sends a clear signal to these companies: if you name your driver assistance system in a way that misleads consumers about its actual autonomy level, you'll face regulatory action. This will likely force a broader shift in how the automotive industry names and markets these features.

Some automakers might follow Tesla's path and rebrand their systems with more technically accurate names. Others might just change their marketing language without changing the product names. But the effect will be the same: a general movement toward more accurate communication about what these systems can and cannot do.

This is actually positive for consumers. Clearer communication about driver assistance capabilities means fewer accidents caused by misuse, fewer insurance disputes, and fewer lawsuits when systems fail to perform as consumers expected.

The Full Self-Driving subscription is nearly twice as expensive as the old Autopilot model, impacting new Tesla buyers. Estimated data.

The Unresolved Question: Are These Systems Actually Safe?

While the regulatory battle focused on marketing terminology, the underlying question is much bigger: are these driver assistance systems actually safe enough to deploy at scale? The marketing terminology matters, but only because it affects how consumers interact with the technology.

Tesla's Full Self-Driving (Supervised) has been in beta testing for several years. The company has collected vast amounts of data about how the system performs in real-world conditions. This data is valuable for improving the system, but Tesla hasn't made much of it publicly available in peer-reviewed form. The company has released statistics about accident rates among Full Self-Driving users, but these statistics don't necessarily prove the system is safer than human driving, because full FSD users are typically early adopters and more sophisticated drivers than average.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has opened multiple investigations into Tesla's driver assistance systems, including safety investigations into crashes involving Autopilot and Full Self-Driving users. These investigations haven't resulted in major enforcement actions, but they indicate that regulators are taking the safety question seriously.

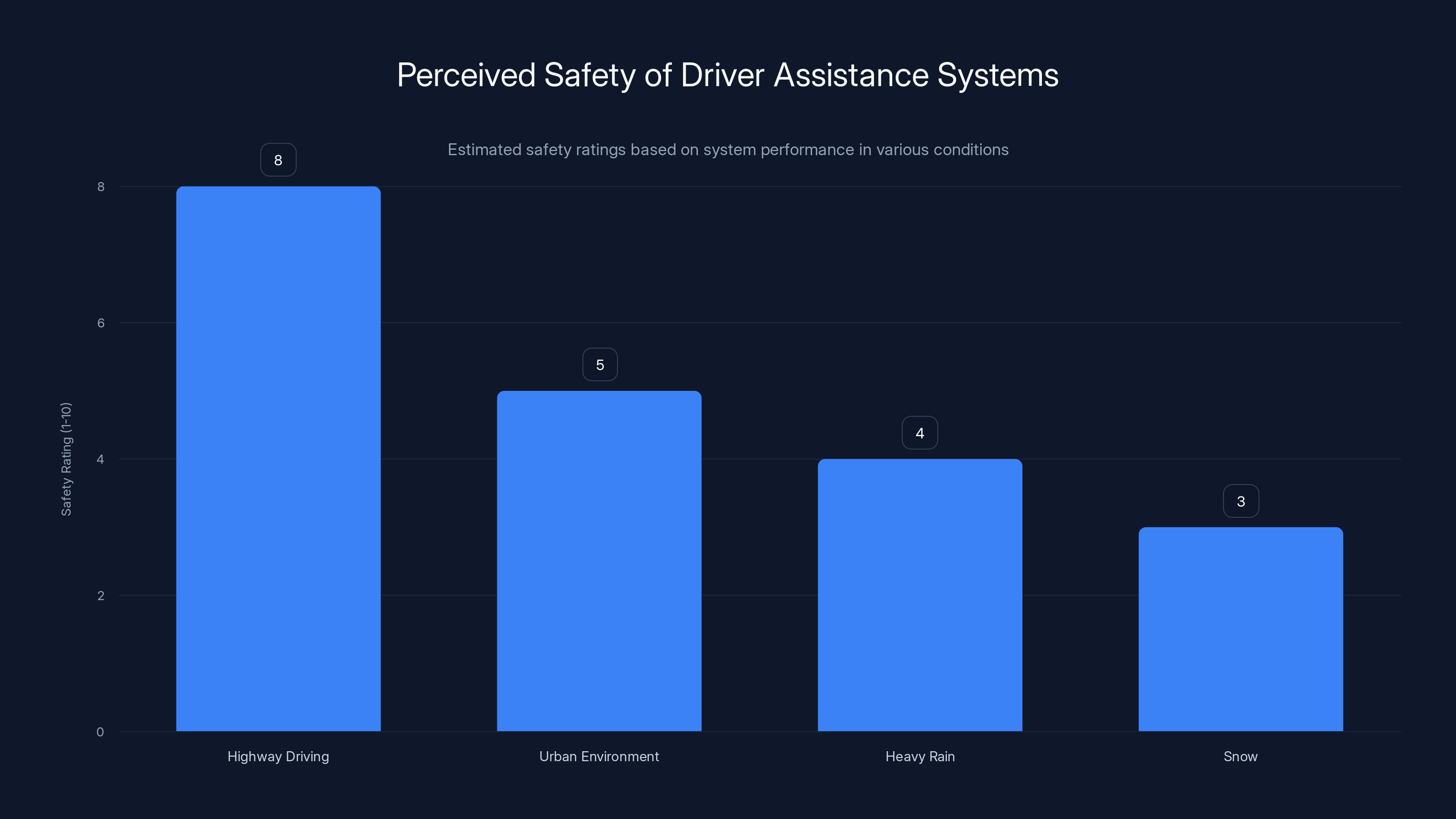

Here's the uncomfortable reality: we don't have definitive evidence either way. We don't know with certainty whether driver assistance systems like Full Self-Driving are safer or less safe than human driving. The systems perform differently in different conditions. They excel at highway driving in clear weather. They struggle with complex urban environments, heavy rain, and snow.

The regulatory process in California focused on marketing accuracy, not safety testing. That's a significant limitation. The DMV ensured that customers would see more accurate language about what the systems do, but that doesn't address whether the systems should be deployed as broadly as they currently are.

How Tesla's Pricing Restructuring Changes Market Dynamics

The shift from

Consider the math from a customer perspective. A new Tesla buyer who wants Full Self-Driving is now looking at a recurring

This pricing structure creates an interesting incentive dynamic. Tesla can now afford to give away the hardware and software infrastructure for Full Self-Driving with every vehicle sold. The company captures revenue from adoption of the service, not from the initial vehicle sale. This is powerful from a competitive perspective. It allows Tesla to make Full Self-Driving available to all its customers without requiring an upfront purchase decision.

Other automakers will likely follow this model. Expect to see a transition across the industry from one-time payments for advanced features to monthly subscriptions. This mirrors what happened with connected car services. Ten years ago, features like remote vehicle access were expensive add-ons. Today, they're bundled subscriptions in most vehicles.

Estimated safety ratings suggest driver assistance systems perform best in highway conditions but struggle in complex environments like urban areas and adverse weather. Estimated data.

The Regulatory Framework's Limitations

What's most interesting about the California situation is what it reveals about the limitations of existing regulatory frameworks for autonomous technology. The DMV's focus was on marketing accuracy, which is appropriate for a motor vehicle licensing authority. But it's not the same as addressing whether the technology should be deployed as broadly as it currently is.

Federal regulators, including NHTSA, have broader authority over vehicle safety. But they've been hesitant to impose restrictions on driver assistance systems, preferring to monitor them and investigate when problems emerge. This is a reactive rather than proactive regulatory approach.

Proactive regulation would involve requiring extensive testing of driver assistance systems under controlled conditions before widespread deployment. It would involve setting standardized performance metrics. It would involve establishing clear liability frameworks when systems fail.

The U.S. doesn't have this yet. Europe is developing more structured regulatory approaches for autonomous vehicles, but those are still in early stages. China is allowing extensive autonomous vehicle testing in specific zones, which is a different regulatory philosophy altogether.

The practical result is that driver assistance system deployment is outpacing regulatory development. Companies like Tesla are essentially conducting large-scale real-world testing with millions of vehicles, collecting data that informs their engineering, but doing so in a regulatory environment that hasn't fully caught up.

The California DMV's action is a small step toward better regulation, but it's addressing the symptom (misleading marketing) rather than the underlying issue (whether the technology is ready for deployment at this scale).

What This Means For Future Tesla Users

For people who own or are considering purchasing a Tesla, the Autopilot discontinuation and regulatory resolution have several practical implications.

First, if you already own a Tesla with Autopilot, your vehicle still has the feature. Tesla didn't remotely disable Autopilot on existing vehicles. Customers who paid for the feature get to keep it. The discontinuation only affects new purchases. This is important because it prevents a situation where Tesla could have angered existing customers by retroactively removing a feature they paid for.

Second, if you're considering purchasing a new Tesla and want driver assistance features, you'll need to commit to the $99 monthly Full Self-Driving subscription. This is more expensive than the old Autopilot model for most customers. You can drive the vehicle without Full Self-Driving, but you'll lose access to the more advanced features.

Third, the regulatory clarity provides some assurance that Tesla is more carefully considering how it markets its systems. The company faced real consequences for misleading marketing, and it's unlikely to repeat that mistake in the same way. But this doesn't guarantee that Full Self-Driving (Supervised) is more accurate in its communication than Autopilot was. You still need to read the fine print and understand what the system actually requires from you as a driver.

Fourth, the experience suggests that regulatory scrutiny of autonomous vehicle marketing is likely to increase. If you buy a Tesla or any other vehicle with driver assistance features, it's reasonable to expect that regulators will continue examining how these systems are marketed and whether the marketing matches the capability.

The Broader Implications For AI and Consumer Protection

The Tesla case is significant beyond the automotive industry because it demonstrates how consumer protection law intersects with advanced technology marketing. Tesla is an AI company as much as it is an automaker. Its driver assistance systems rely on neural networks, real-time data processing, and machine learning. The regulatory challenge is ensuring that companies don't oversell what their AI systems can do.

This pattern is likely to repeat across industries. As companies deploy AI in more consumer-facing applications, regulators will face the same fundamental question: how do we ensure that marketing accurately reflects what the technology actually does?

In healthcare, if a company offers an AI diagnostic tool, the marketing needs to match the system's actual accuracy and limitations. In financial services, if a company offers an AI robo-advisor, the marketing needs to explain the system's decision-making process and limitations. In hiring, if a company offers AI-powered recruitment tools, the marketing needs to disclose accuracy disparities across demographic groups.

The California DMV's action against Tesla is a template for how regulators might approach these questions. Focus on whether marketing claims match technical capabilities. Require companies to demonstrate that their claims are accurate. Impose penalties when they're not. This is a straightforward but powerful approach.

One limitation is that regulatory action is slow. The Tesla case took three years from initial complaint to resolution. In a fast-moving technology industry, three years is an eternity. By the time a regulator finishes investigating and pursuing enforcement, the company has usually moved on to the next product iteration. This timing mismatch is a fundamental challenge in technology regulation.

Looking Forward: The Autonomous Vehicle Landscape in 2025 and Beyond

As we move deeper into 2025, the autonomous vehicle landscape is shifting in several important directions. Tesla's experience in California is one data point in a much larger story about how autonomous technology is evolving and how regulators are responding.

Waymo, Alphabet's autonomous vehicle subsidiary, continues expanding its robotaxi service in several cities. Unlike Tesla's approach, which relies on customer vehicles with driver assistance capabilities, Waymo is deploying purpose-built vehicles with human operators ready to take over if needed. This is a fundamentally different business model and risk profile.

Traditional automakers are moving more cautiously. GM's Super Cruise, Ford's Blue Cruise, and similar systems offer highway driver assistance but stop short of Tesla's more ambitious Full Self-Driving vision. These companies are prioritizing proven safety over marketing ambition.

Startups are pursuing various approaches: some building fully autonomous vehicles for specific use cases like last-mile delivery or shuttle services, others developing driver assistance software that competes with Tesla, others focusing on the infrastructure and data needed to enable autonomous vehicles.

The regulatory environment is evolving as well. NHTSA is developing guidelines for autonomous vehicle testing. California is establishing more structured frameworks for autonomous vehicle deployment. The federal government is considering legislation that would clarify liability frameworks and safety standards.

Tesla's forced pivot from Autopilot to Full Self-Driving (Supervised) subscription model is an important moment in this evolution. It demonstrates that marketing accuracy for autonomous technology is now a regulated issue, not just a competitive concern. Companies will need to ensure their marketing matches their technology's capabilities.

How Consumer Awareness Changed The Narrative

One often-overlooked aspect of the Tesla regulatory case is how consumer awareness influenced the outcome. Advocates, journalists, and regulators became increasingly skeptical of Tesla's Autopilot marketing because of well-publicized accidents and near-misses involving drivers who appeared to have overestimated what the system could do.

These incidents created a narrative around Autopilot that made regulators take action. If driver assistance systems had been working flawlessly with zero incidents, regulators might have been more inclined to defer to industry self-regulation. But the accumulation of incidents where drivers seemed confused about the system's capabilities created pressure for regulatory intervention.

This pattern is important because it shows how public perception and awareness can drive regulatory change. Regulators don't always act proactively. They often act in response to public pressure and evidence that current rules aren't achieving their intended goals.

For consumers, this means that reporting your experiences with driver assistance systems matters. When systems fail, when they behave unexpectedly, when you misunderstand their capabilities, reporting those experiences to manufacturers and regulators contributes to the information that drives regulatory decision-making.

Conclusion: The Resolution That Solves The Wrong Problem

Tesla dodging a 30-day license suspension in California is a regulatory win, but it's important to understand what actually happened and what it means. The company faced a genuine legal challenge based on misleading marketing. It responded by discontinuing the misleading product and restructuring its pricing model in a way that advances its broader business strategy. The regulator, getting the result it wanted (no more misleading Autopilot marketing), accepted the solution and didn't pursue the suspension.

From a marketing accuracy perspective, this is a success. Consumers will see clearer language about what Tesla's driver assistance systems can and cannot do. The regulatory process demonstrated that companies can't engage in misleading marketing without consequences. These are good outcomes.

But from a technology safety perspective, nothing fundamental has changed. The driver assistance systems still have the same capabilities and limitations. Drivers still need to maintain full attention while using them. The systems still perform better in some conditions than others. Renaming them and restructuring the pricing doesn't address these underlying realities.

The bigger lesson is about how regulatory frameworks lag behind technology deployment. Regulators are still catching up to what autonomous vehicles actually are and whether they're safe enough for widespread deployment. The California DMV did what it was empowered to do: ensure accurate marketing. But the deeper questions about technology safety, capability assessment, and deployment criteria remain unresolved.

For Tesla, the company emerges from this situation stronger. It solved the regulatory problem, extracted a more favorable business model, and avoided the catastrophic impact of a sales suspension in its most important market. The company's ability to move quickly and make strategic decisions when facing regulatory pressure is a competitive advantage.

For the broader autonomous vehicle industry, the case demonstrates that marketing accuracy will increasingly be a regulated issue. Companies will need to think carefully about how they name and describe their systems. This is actually positive, because it creates incentives for more honest communication about technology capabilities.

For consumers, the lesson is to read beyond the names. What matters isn't what a system is called, but what it actually requires from you as a driver and what it can and cannot do. The California regulatory process made that distinction clearer, even if it didn't fundamentally change the underlying technology.

FAQ

What is the difference between Autopilot and Full Self-Driving?

Autopilot was Tesla's basic driver assistance system, offering features like cruise control and lane keeping but requiring constant driver attention. Full Self-Driving (Supervised) is Tesla's more advanced system that offers additional capabilities but still legally requires active driver supervision. The primary difference is the feature set and sophistication level, though both remain Level 2 autonomy systems that cannot drive without an engaged driver.

Why did the California DMV take action against Tesla's Autopilot marketing?

The DMV argued that the term "Autopilot" was inherently misleading because it suggested the vehicle could drive itself autonomously, when in reality it required constant driver attention and control. The regulator concluded that Tesla violated California's consumer protection laws by using terminology that misrepresented the system's actual capabilities to consumers.

How much did Tesla's compliance cost the company?

Tesla faced no direct financial penalty, but the compliance involved discontinuing an entire product line and restructuring its pricing model. Autopilot was previously included as a standard feature in many Tesla vehicles, while Full Self-Driving (Supervised) now requires a $99 monthly subscription. Long-term, this actually benefits Tesla by creating predictable recurring revenue, though it increases costs for customers who want driver assistance features.

Can existing Tesla owners with Autopilot still use it?

Yes, existing Tesla owners who previously purchased or had Autopilot included with their vehicle can continue using the feature. Tesla only discontinued Autopilot for new vehicle purchases. Customers who already own the technology retain access to it, so they weren't penalized for Tesla's marketing practices.

Is Full Self-Driving (Supervised) actually fully self-driving?

No, despite its name, Full Self-Driving (Supervised) is still a Level 2 driver assistance system that requires active driver supervision. The "Supervised" designation is meant to clarify that driver intervention is still required. The system can perform driving tasks like steering and acceleration, but the driver must remain engaged and ready to take control at any moment.

What does the $99 monthly subscription for Full Self-Driving include?

The $99 monthly Full Self-Driving (Supervised) subscription provides access to Tesla's most advanced driver assistance capabilities, including features like navigate on autopilot, auto lane change, and parking automation. The subscription requires active membership to maintain access to these features, and Tesla has indicated the price may increase as the system becomes more capable.

Are other automakers facing similar regulatory pressure?

Potentially yes. Other automakers use similarly ambitious names for their driver assistance systems (Super Cruise, Blue Cruise, Intelligent Drive). The California DMV's action against Tesla establishes a precedent suggesting that regulators will scrutinize driver assistance system marketing for accuracy. Other companies may proactively adjust their marketing language to avoid similar regulatory challenges.

Will the subscription model for Full Self-Driving become industry standard?

It's likely. The subscription model creates predictable recurring revenue, which is more attractive to investors than one-time purchases. Other automakers are already exploring subscription-based models for advanced features. Tesla's experience suggests that this model is both commercially advantageous and may become necessary to satisfy regulatory accuracy requirements.

What safety testing has Full Self-Driving (Supervised) undergone?

Tesla hasn't published comprehensive third-party safety testing for Full Self-Driving. The company relies on real-world deployment data from millions of vehicles using the system. Federal regulators including NHTSA have opened investigations but haven't completed them. Independent testing and peer-reviewed research on Full Self-Driving safety is limited.

How does Tesla's approach compare to other companies developing autonomous vehicles?

Tesla relies on customer vehicles to test and improve its system, collecting data from millions of miles of real-world driving. Companies like Waymo use purpose-built autonomous vehicles with safety operators. Traditional automakers move more cautiously with highway-specific systems. Each approach involves different trade-offs between speed of development, safety assurance, and regulatory risk.

What happens if I misuse Full Self-Driving and there's an accident?

Liability in accidents involving driver assistance systems is complex and depends on specific circumstances. If investigation shows the driver failed to maintain required supervision, the driver would likely bear liability. If investigation shows the system failed unexpectedly, liability could fall on Tesla. Insurance policies and legal frameworks around autonomous vehicle liability are still evolving, particularly in California.

Why does California have special regulatory authority over vehicles?

Under the federal Clean Air Act, California earned special authority to set its own vehicle emissions standards, which can be stricter than federal standards. Other states can then choose to follow California's standards. Because California is the world's second-largest automotive market, its regulatory decisions effectively set standards for the entire U.S. automotive industry. This is why the DMV's regulatory action against Tesla carried such weight.

Key Takeaways

- Tesla avoided a catastrophic 30-day sales suspension in California by discontinuing Autopilot and restructuring its pricing model

- The three-year regulatory battle established that driver assistance system marketing must accurately reflect technical capabilities

- Discontinuing Autopilot and converting Full Self-Driving to a subscription model actually advanced Tesla's business strategy while solving regulatory problems

- The regulatory action focused on marketing accuracy but left underlying questions about technology safety unresolved

- Other automakers will likely face similar regulatory scrutiny for ambitious driver assistance system naming

- The subscription model for driver assistance features is likely to become industry standard

- Existing Tesla owners with Autopilot retain access to the feature despite discontinuation for new purchases

Related Articles

- Robotaxis Meet Gig Economy: How Waymo Uses DoorDash to Close Doors [2025]

- Why Waymo Pays DoorDash Drivers to Close Car Doors [2025]

- Waymo's DC Robotaxi Campaign: How AI Companies Are Reshaping City Regulation [2025]

- Aurora's Driverless Trucks: The Superhuman Era of Autonomous Freight [2025]

- Waymo's Sixth-Generation Robotaxi: The Future of Autonomous Vehicles [2025]

- Waymo's Fully Driverless Vehicles in Nashville: What It Means [2025]

![Tesla Dodges 30-Day License Suspension in California [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/tesla-dodges-30-day-license-suspension-in-california-2025/image-1-1771389330145.jpg)