Introduction: The Robot That Walks Like You

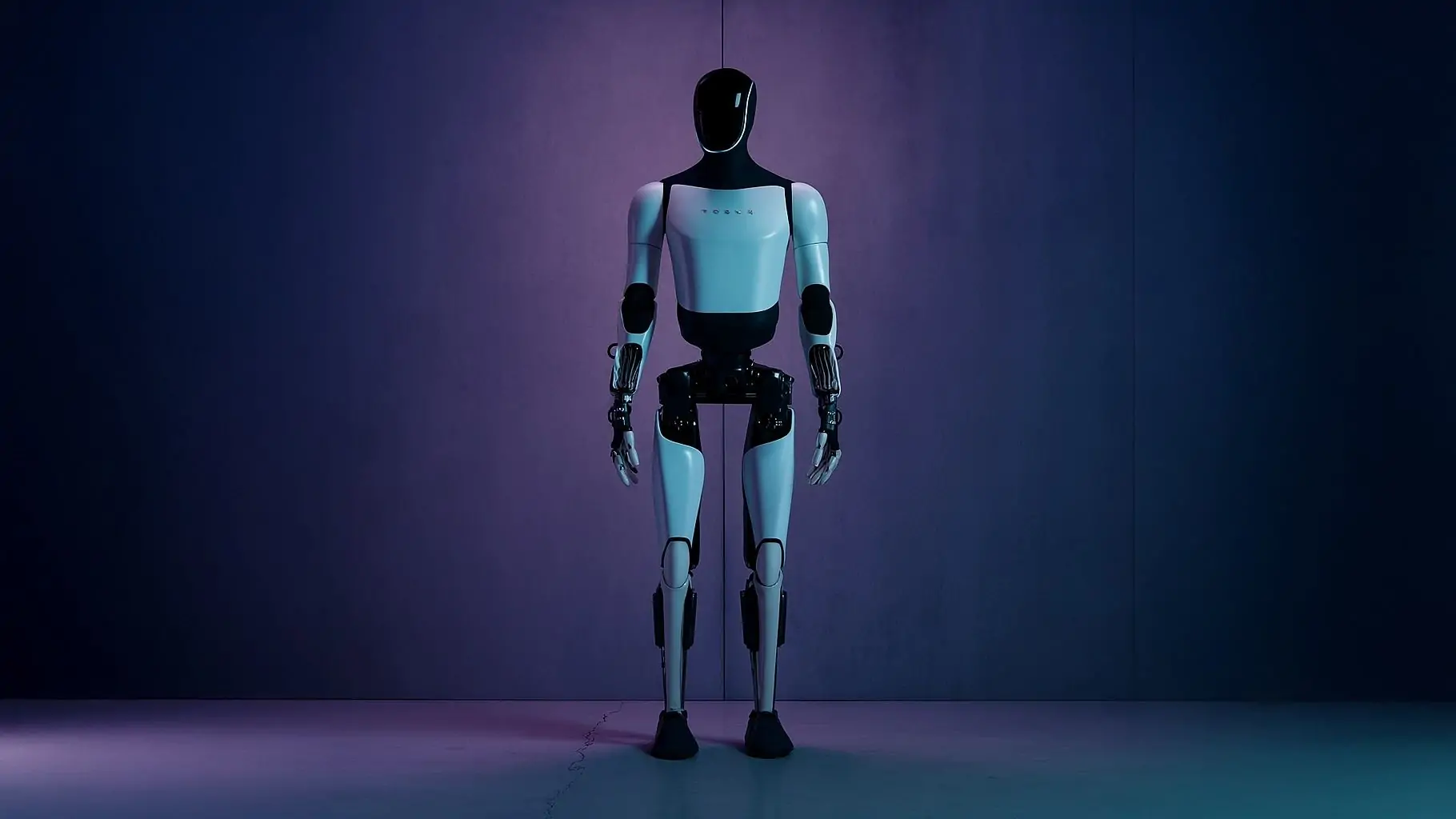

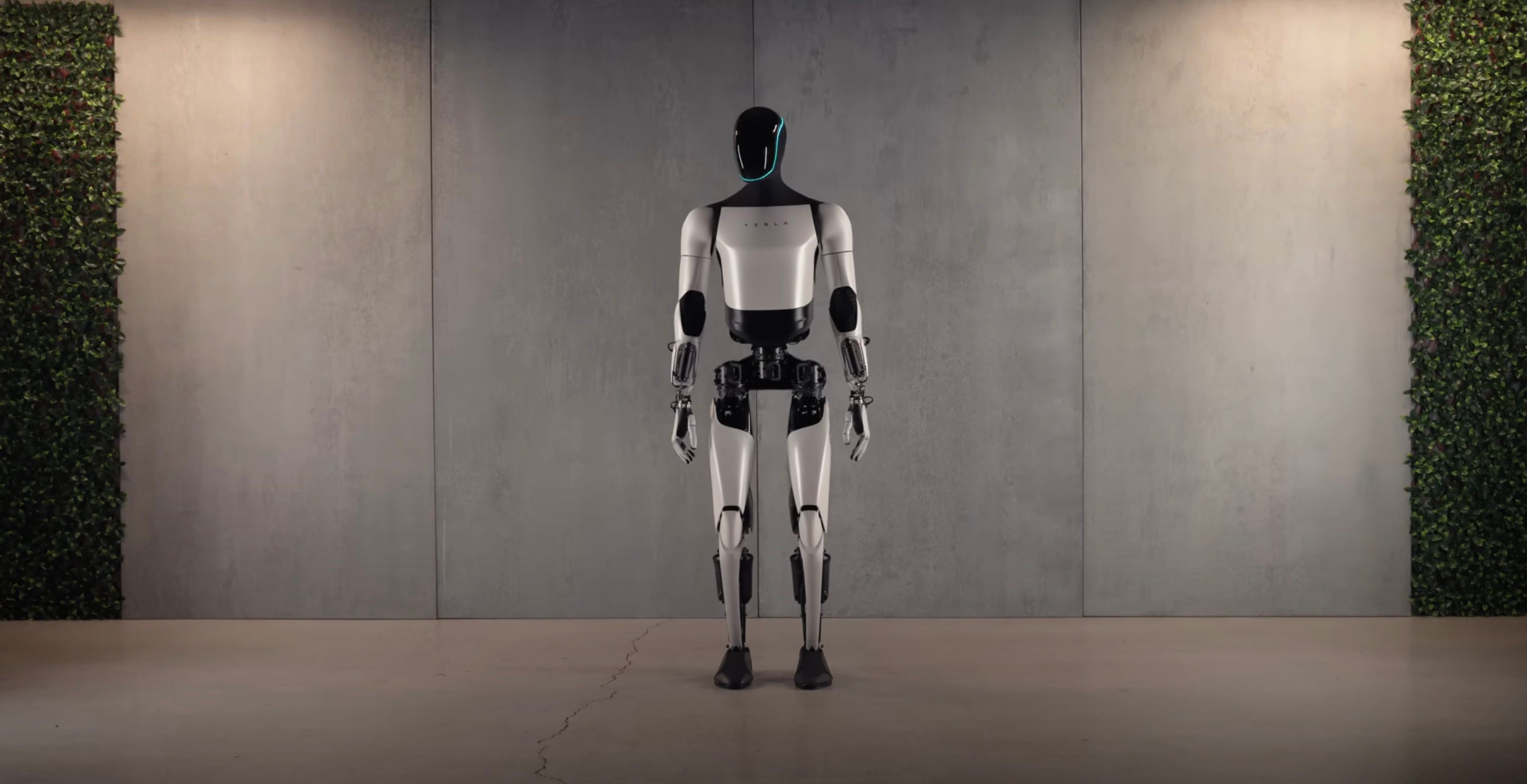

Imagine a robot that doesn't just move like a human—it moves so much like a human that people genuinely can't tell the difference at first glance. That's not science fiction anymore. That's Tesla's Optimus Gen 3, and it's arriving sooner than most people expected.

For years, humanoid robots lived in that weird space between promising and pointless. They could do specific tasks in controlled environments, but put them in the real world? They stumbled, fell, confused basic hand movements, and generally looked like they were piloting their own bodies for the first time. Tesla's approach has been different. Instead of building robots that look obviously mechanical, they're building robots that look like they could work as your neighbor.

The implications are staggering. Not in a "robots will take over the world" way—though people definitely worry about that—but in a "this changes how manufacturing, logistics, and services work" way. A robot that moves naturally has fewer mechanical points of failure. It can use tools designed for humans. It can navigate spaces built for humans. It doesn't need a specialized factory line with custom safety cages. It just works in the space where humans already work.

What sets Optimus Gen 3 apart from previous iterations isn't just faster speeds or stronger grips. It's the combination of visual realism, movement smoothness, and task versatility that makes companies and investors sit up and pay attention. Tesla executives have been publicly bullish about this. One Tesla executive said exactly what everyone's thinking: "It's an awesome robot. It looks like a human. People could be easily confused that it's a human." That statement, simple as it sounds, captures the fundamental shift happening in robotics.

This article digs deep into what Optimus Gen 3 actually is, why the human-like design matters more than you'd think, what it can do in practice, and what this means for your job, your industry, and the economy over the next decade. We're past the point where humanoid robots are theoretical. They're here. The question now is what we do with them.

TL; DR

- Optimus Gen 3 looks remarkably human, making it intuitive to work alongside and capable of using human-designed tools without modification

- Human-like movement reduces mechanical complexity, lowering failure rates and manufacturing costs compared to previous bulky robot designs

- Practical applications range from manufacturing to healthcare, with immediate deployment potential in repetitive, dangerous, or labor-intensive tasks

- Economic impact could reshape labor markets, particularly in developed economies where labor costs drive automation investment

- Timeline is accelerating: Production timelines suggest meaningful deployment within 2-4 years, not decades

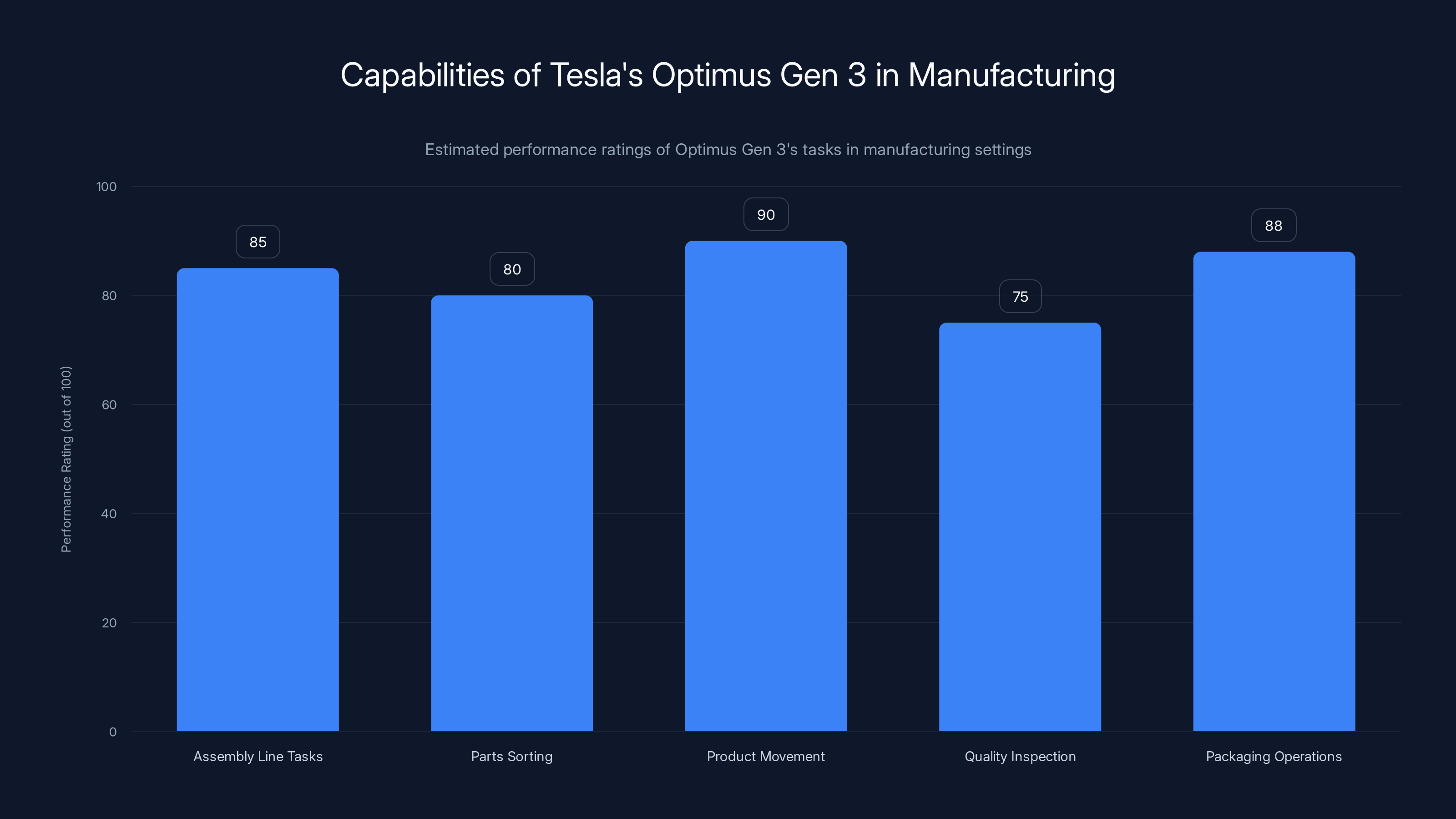

Optimus Gen 3 excels in product movement and packaging operations, with high performance ratings across various manufacturing tasks. Estimated data.

Understanding Optimus Gen 3: More Than Just a Pretty Robot

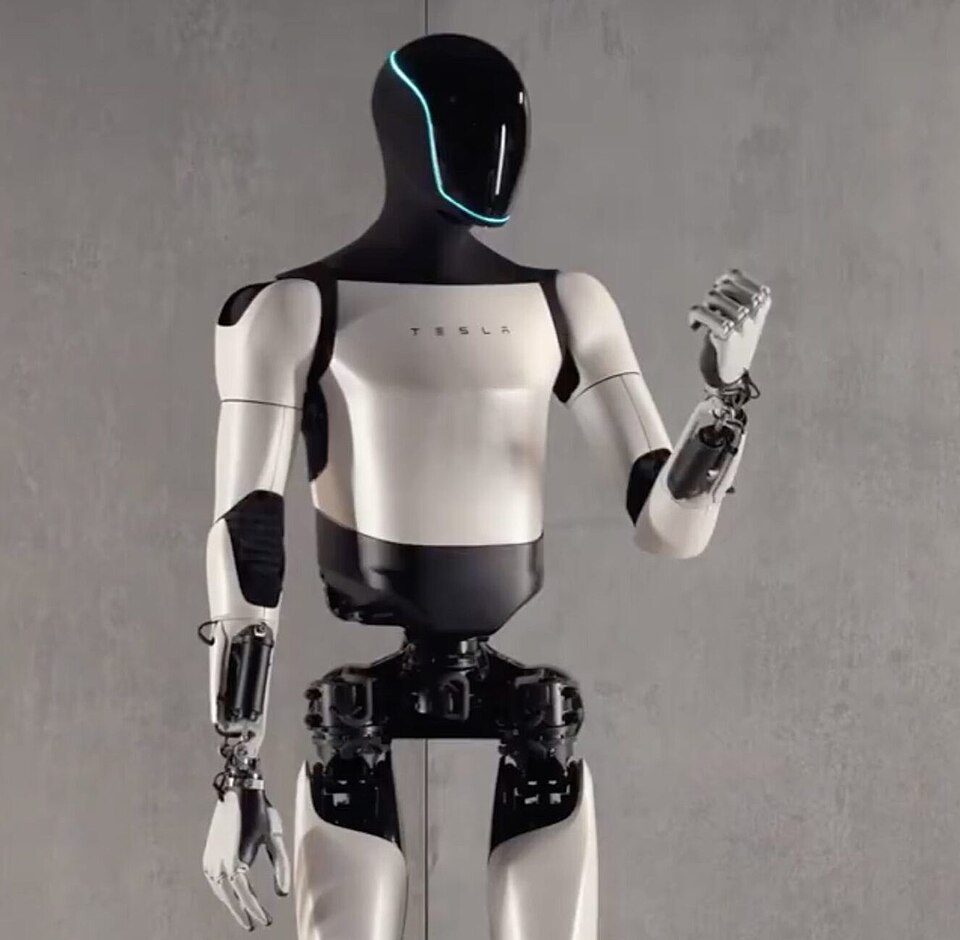

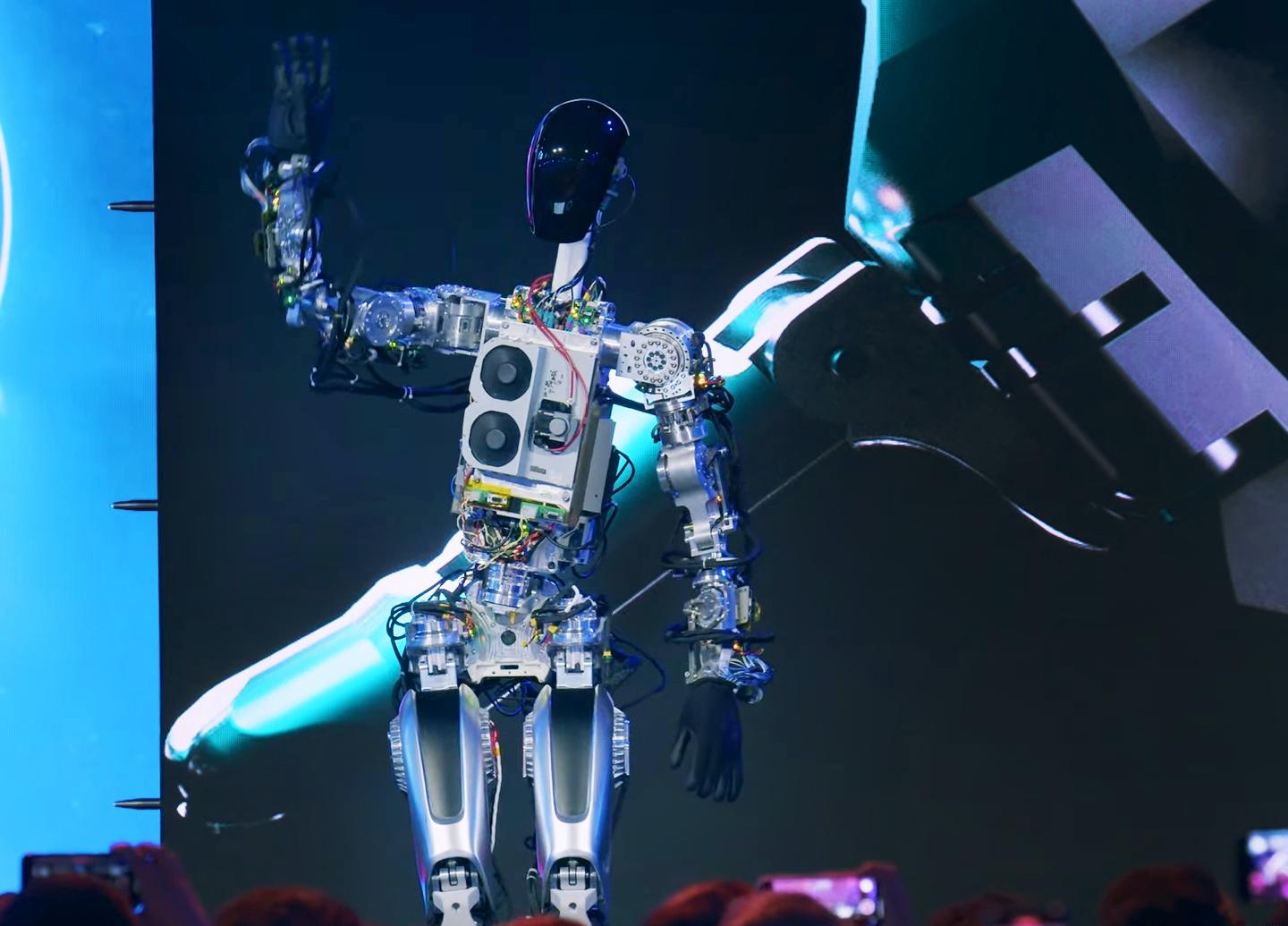

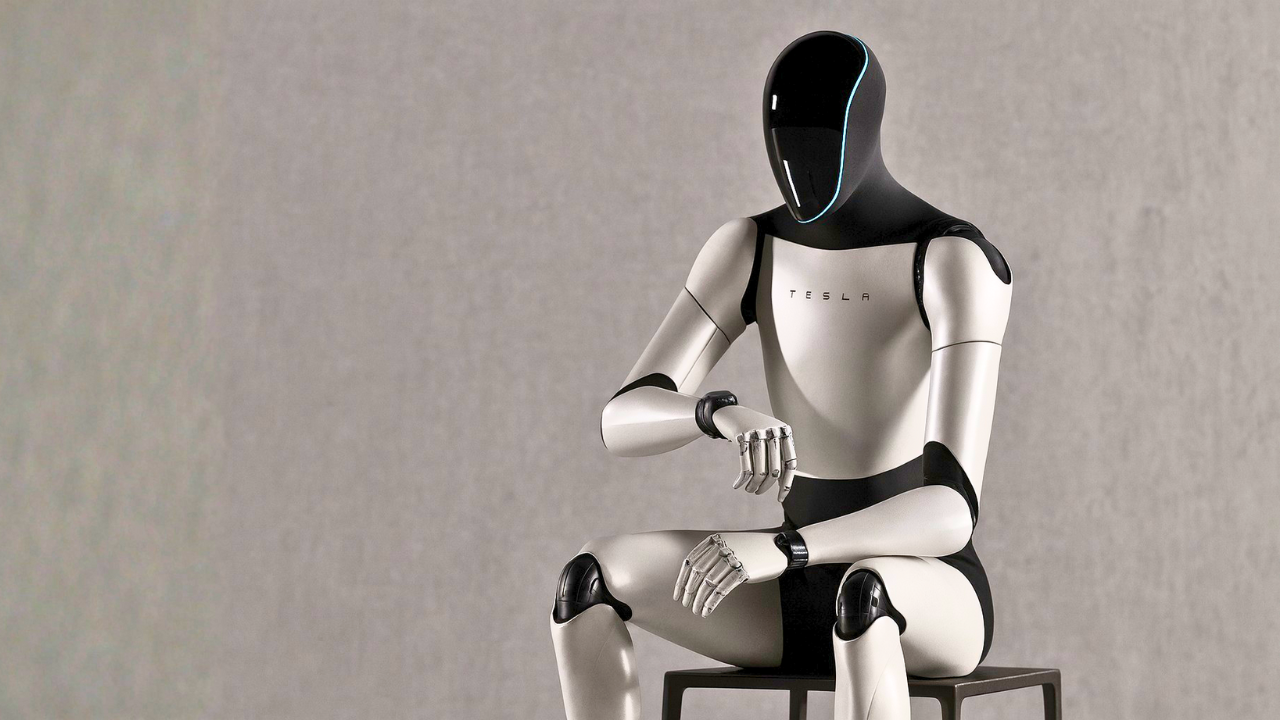

Optimus Gen 3 looks like a humanoid figure standing about 5 feet 8 inches tall, weighing roughly 125 pounds. On paper, that sounds like just another tall robot. But in motion, something feels different. The way it walks, the fluidity of its hand movements, the natural way it adjusts balance while reaching for objects—none of that is accidental. Every movement was engineered to mimic human biomechanics as closely as possible.

The Gen 3 upgrade from previous versions isn't a minor tweak. Tesla fundamentally redesigned critical joints and actuators to move like human muscles, not like industrial machinery. Where earlier robots moved in jerky, segmented motions, Optimus Gen 3 moves with continuity. It's subtle, but your brain notices it immediately. That's the whole point.

The design philosophy here matters more than the specific mechanical specs. Tesla isn't trying to build the "best" robot in an abstract sense. They're building a robot that fits into existing human environments. That means using tools designed for human hands. That means walking into a factory floor without requiring retrofitted infrastructure. That means a security guard can talk to it naturally without feeling like they're operating a forklift.

Previous humanoid robots—and there have been dozens of attempts—made a different choice. Boston Dynamics' Atlas, for instance, prioritized jumping ability and parkour-style movement. That's impressive from an engineering standpoint. Practically speaking, nobody needs a robot that does a backflip. Optimus Gen 3 prioritizes walking calmly through a warehouse, picking items precisely, and handing them to a coworker. That matters far more in the real world.

The aesthetic choices are deliberate too. The robot's face isn't creepy—it's intentionally neutral. It doesn't have an uncanny valley problem because Tesla didn't try to make it look exactly human. Instead, it looks clearly robotic but moves so naturally that your brain accepts it as "another worker" rather than "weird mechanical thing."

Optimus Gen 3 costs an estimated

The Engineering Behind Human-Like Movement

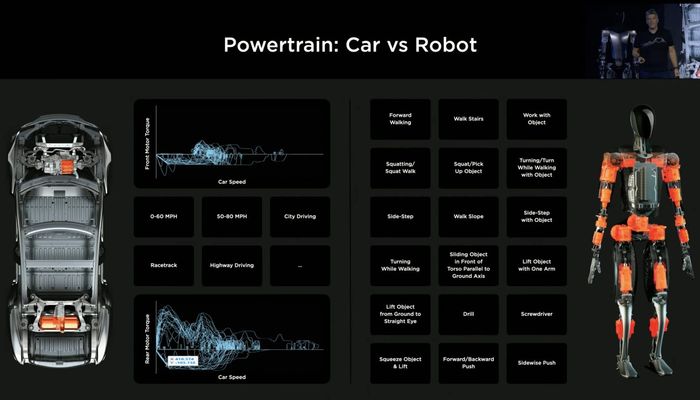

Building a robot that moves like a human requires solving problems that humans solve without thinking. How do you maintain balance while reaching? How do you adjust your gait on uneven surfaces? How do you pick up a fragile object without crushing it? These are simple for humans because evolution spent millions of years on them. For engineers, they're nightmares.

Optimus Gen 3 uses a full-body sensing array—think of it as proprioception and tactile feedback working together. The robot has pressure sensors across its body, multiple cameras, and lidar systems that create a real-time 3D map of its environment. More importantly, it has force feedback in its hands. That means when it picks something up, it can feel the resistance and adjust pressure accordingly. A squishy tomato doesn't get crushed. A heavy box doesn't slip.

The actuators—the "muscles" of the robot—are the real innovation. Earlier robots used massive electric motors, hydraulic systems, or pneumatic pressure. These made robots either slow or dangerously powerful. Optimus Gen 3 uses distributed actuators, smaller electric motors at each joint that work in coordination. This creates smooth, controlled motion because the movements aren't controlled by a single powerful force trying to move a rigid structure. Instead, multiple smaller forces work together, adjusting in real-time.

This matters for one specific reason: efficiency. A robot that moves smoothly uses less energy than a robot that moves jerky because there's no wasted motion. The difference between a servo motor that moves 5 degrees in a jerky arc versus one that glides smoothly through the same arc might seem tiny, but multiply that across 25 joints moving continuously throughout an 8-hour shift, and you're looking at the difference between profitable deployment and a robot that costs too much to operate.

The walking algorithm is where Tesla's AI expertise really shows. Previous robots used pre-programmed gaits—basically motion libraries where the robot has learned "here's how you walk on flat ground, here's how you walk upstairs, here's how you walk on a slope." Optimus Gen 3 uses dynamic balance. It's continuously adjusting its center of gravity, joint angles, and stride length based on what its sensors tell it about the environment. That's why it can walk on slightly uneven warehouse floors without falling, and why it can adjust for worn-out flooring or debris without being explicitly programmed for that scenario.

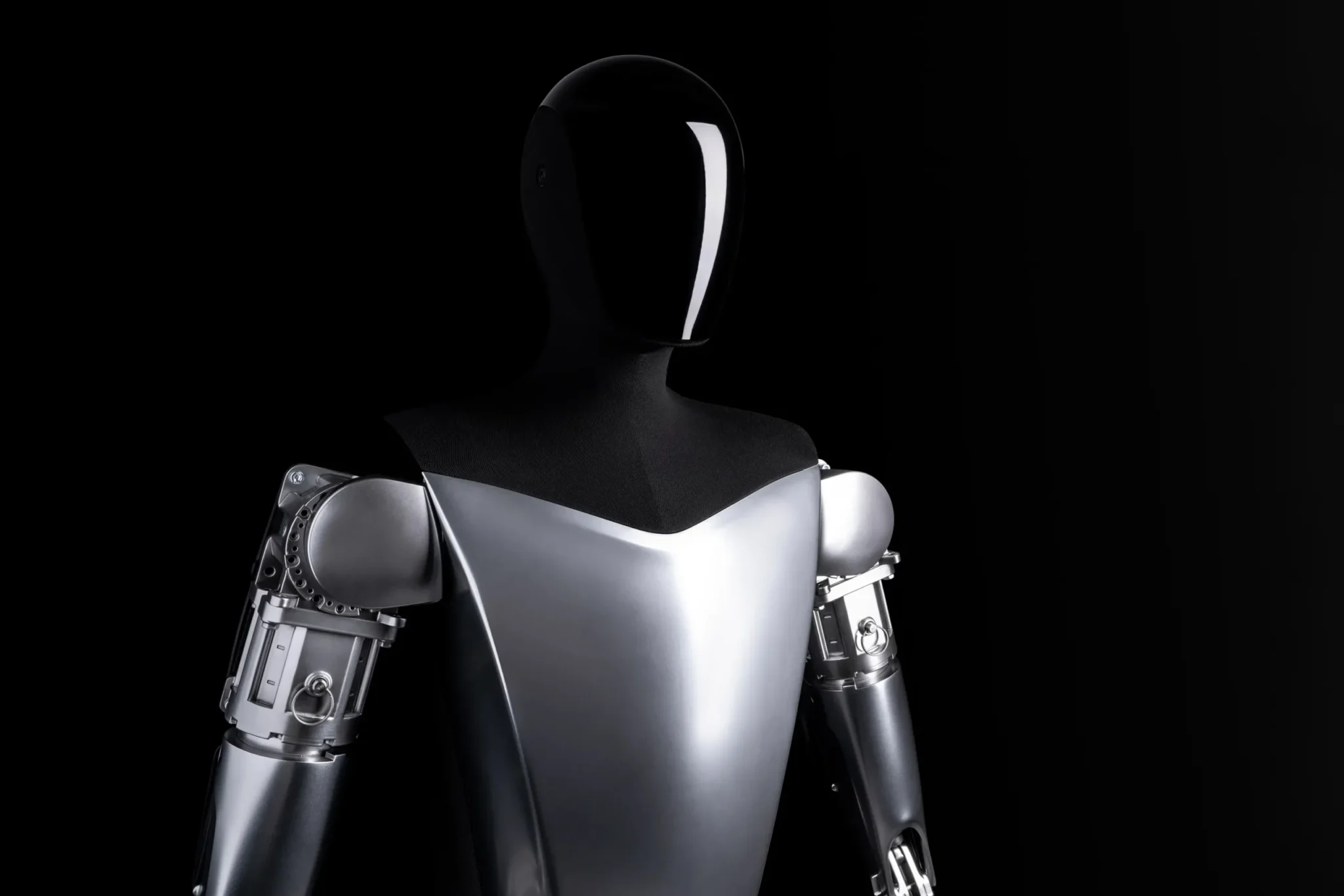

Visual Design and the "Uncanny Valley" Problem (That Tesla Solved)

There's a psychological principle called the uncanny valley. When something looks almost human but not quite, it creeps people out. It's why early motion-capture monsters in movies felt wrong, and why some robot faces look disturbing even though they're technically impressive. Most humanoid robot projects fell into this trap. They made robots that looked roughly human but moved awkwardly, creating cognitive dissonance.

Tesla's solution was counterintuitive: make it obviously a robot, but make it move like a human. The design is sleek and clearly artificial. You'd never mistake Optimus for an actual human up close. But when you watch it move, your brain's movement-recognition systems say "that's how humans move," and that reconciles the mismatch between appearance and behavior.

This is actually smarter than trying to create photorealism. Here's why: humans are extremely good at detecting fake humans. We've evolved to spot imposters because it mattered for survival. But we're much worse at analyzing movement patterns when the basic design is clearly non-human. If Optimus had a hyperrealistic face but moved like a robot, you'd be constantly disturbed. But with a clearly artificial design and human-like movement, you're less disturbed because you're not fighting your own perceptual systems.

The face design is minimal—a screen that can display information without being visually complex. This serves multiple purposes. It's less costly to manufacture. It's culturally neutral, which matters for global deployment. It can display emotional context through simple animations without trying to do a full emoji face. And it doesn't trigger uncanny valley responses.

This might seem like a cosmetic choice, but it's actually crucial for adoption. If factory workers find robots disturbing, they won't cooperate with them effectively. If they feel comfortable around the robot, they'll naturally work better alongside it. That's not a psychological trick—that's optimizing for real human-robot collaboration.

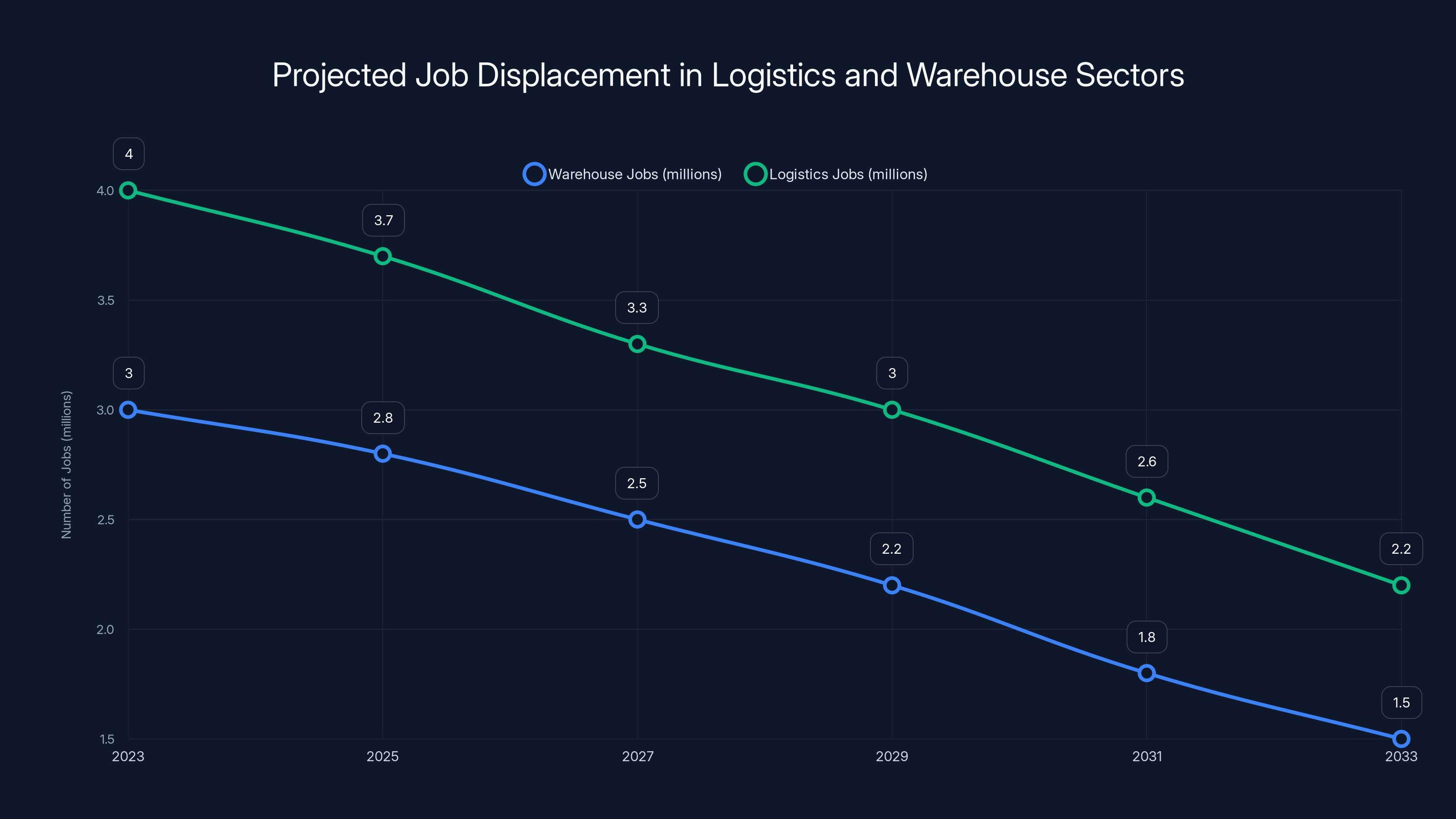

Estimated data shows a significant decline in warehouse and logistics jobs due to automation over the next decade. Policy intervention is crucial to mitigate unemployment risks.

Hands and Fine Motor Control: Where Precision Lives

A humanoid robot is only as useful as its hands. You could have the greatest balance and walking system in the world, but if the robot can't do precise tasks, it's just an expensive delivery vehicle.

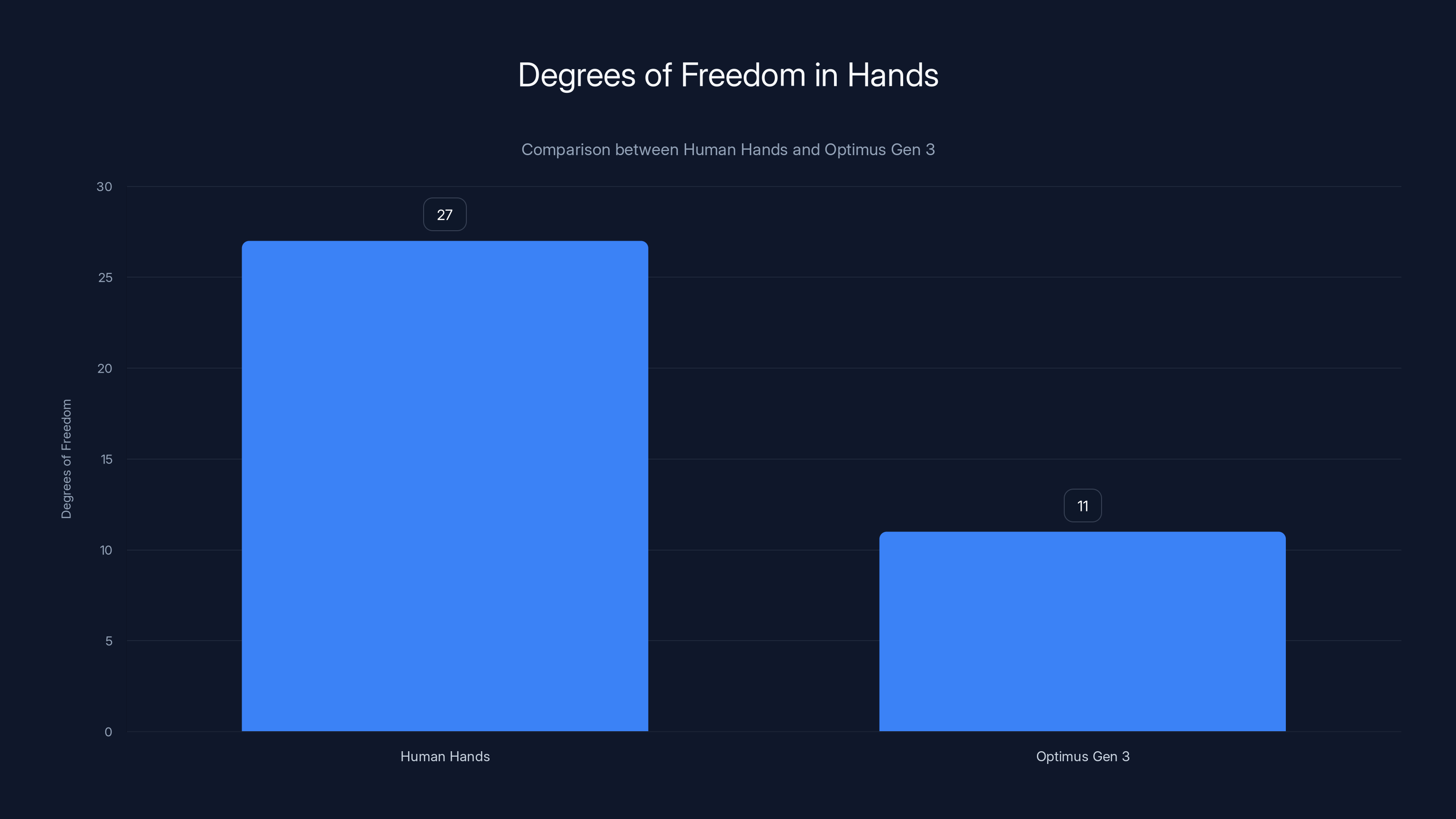

Optimus Gen 3's hands have 11 degrees of freedom—meaning 11 different ways they can move. Human hands have 27 degrees of freedom, so it's not matching human capability exactly. But here's the important part: those 11 movements are the ones that actually matter for 90% of real-world tasks. You don't need to move your pinky at the exact same range as a factory robot needs for assembling parts.

The hands use a parallel gripper design that can apply consistent pressure. This sounds simple until you think about all the scenarios. A gripper needs to hold a delicate egg, a slippery metal part, a textured carton, and a plastic handle all with the same hardware. Optimus Gen 3 uses something called "adaptive compliance." Basically, the gripper learns from the first 100 milliseconds of contact what something feels like, and then adjusts grip pressure automatically. Too hard, and fragile items break. Too soft, and slippery items fall. Get it right, and the gripper just knows.

The speed is also relevant. A human hand can make targeted movements at about 1-2 meters per second. Optimus Gen 3 can achieve similar speeds in the critical manipulation zone (the area in front of its body where tasks usually happen). This means the robot isn't just slower than a human at every task—for specific repeated motions, it can actually keep pace. And unlike a human, it doesn't get tired, it doesn't need breaks, and it performs the same motion identically every single time.

The force feedback in the hands is where the real intelligence shows. Sensors measure the force being applied constantly. The control system gets that data hundreds of times per second. If the robot is picking up something and the sensor reads a sudden spike in force, the system knows it's about to bend or break something, and it immediately adjusts. This happens automatically without needing a human to intervene or reprogram anything.

Practical Applications: Where Optimus Gen 3 Works Right Now

This is where theory meets manufacturing floor reality. Optimus Gen 3 isn't designed for one specific task—it's designed to be generalist enough that a company can redeploy it to different tasks as needs change. That's radical compared to industrial robots, which are typically bolted to a specific spot and run the same motion 10,000 times a day forever.

Manufacturing and Assembly

Manufacturing is the obvious first target. Repetitive assembly tasks, sorting, bin picking, quality inspection—all of these are things Optimus can do. The difference from traditional industrial robots is flexibility. A traditional robot arm might take two weeks to reprogram for a different task. Optimus can be shown a task a few times and learn it. Not perfectly on the first try, but through a process called "learning from demonstration," the robot can acquire new skills.

Specific scenarios where Optimus works immediately: anything in a factory that requires walking between locations and then performing a localized task. Carrying parts from one station to another. Moving finished products to packaging. Organizing a parts bin. Checking for defects by looking at items from multiple angles. These aren't hypothetical scenarios—Tesla and other manufacturers have already tested these exact workflows.

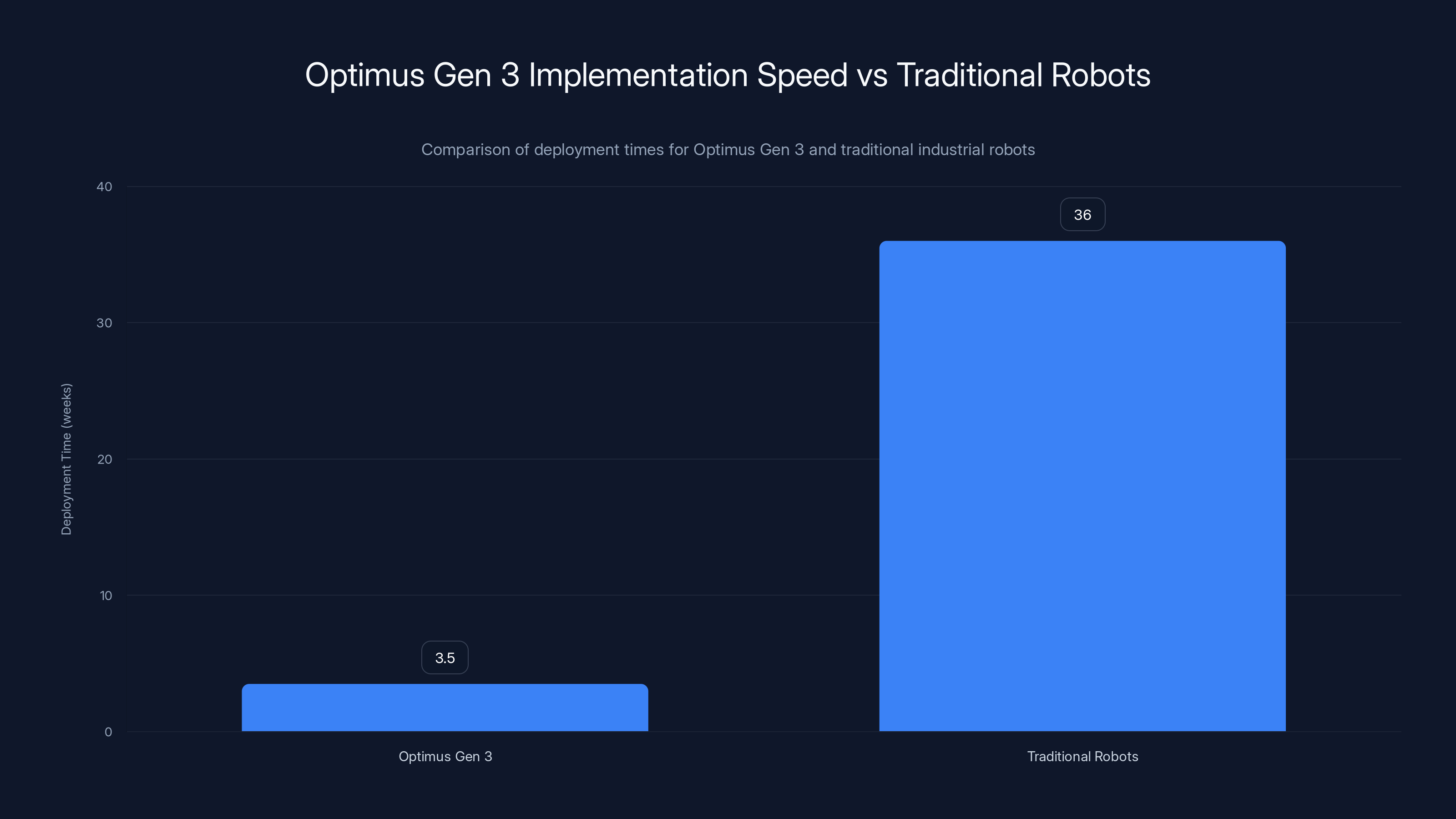

What's novel is the speed of implementation. Traditional industrial automation takes 6-12 months to install and debug. Optimus might take 3-4 weeks because it uses the same workspace, doesn't need custom mounting, and can work around humans without special safety barriers.

Logistics and Warehousing

Warehouses right now employ massive numbers of humans doing physically demanding, repetitive work. Amazon, for instance, employs over 500,000 people in fulfillment centers globally. Many of those jobs involve walking between racks, picking items, and moving boxes. Optimus Gen 3 is basically designed for this.

The advantage in logistics isn't just the labor cost reduction, though that's obviously significant. It's the 24-hour operation capability. Humans need sleep, breaks, and days off. A robot needs charging. If you run two shifts of humans, that's two different teams with different skill levels and training needs. If you run one robot with overnight charging, it's consistent performance, no scheduling headaches, no training new people.

The second advantage is injury reduction. Warehouse work is physically demanding and injury rates are high. Repetitive stress injuries, back injuries from lifting—these are endemic to the industry. Robots don't get injured. They don't file workers' compensation claims. From a business perspective, replacing one human worker with one robot doesn't just save salary; it saves health insurance costs, workers' comp insurance, and the hiring time for replacements.

Healthcare and Elderly Care

This is the application area that's less obvious but potentially more impactful. Hospitals and senior care facilities have massive staffing shortages, particularly for patient assistance. Tasks like helping patients transfer from beds to wheelchairs, assisting with hygiene, or moving supplies around a facility are physically demanding and emotionally taxing.

Optimus Gen 3 can help with lifting, which reduces injury risk for human caregivers. It can assist with patient transfers under human supervision. It can transport items between rooms. It can do the physically demanding parts of caregiving while humans focus on the emotional and psychological aspects that actually matter.

The key here is that Optimus isn't replacing nurses—it's augmenting them. A single nurse can manage more patients if a robot handles the physical burden. That same nurse can spend more time on patient interaction, medication management, and actual care decisions rather than spending half the shift lifting and moving things.

Customer Service and Hospitality

Retail and hospitality companies have been experimenting with service robots for years with mixed results. Optimus Gen 3 changes this because it can actually do customer-facing tasks that require physical interaction. It can carry items, it can demonstrate products, it can assist customers by actually doing things rather than just providing information.

A restaurant might use Optimus to deliver food to tables. It can navigate the space, handle fragile items, and avoid customers and furniture. It's not going to replace servers, but it handles the purely physical part of the job, which lets the staff focus on service quality.

Human hands have 27 degrees of freedom, while Optimus Gen 3 has 11, which are optimized for 90% of real-world tasks. Estimated data.

The AI Behind the Movements: Tesla's Real Competitive Advantage

Here's what most people miss about Optimus Gen 3: the hardware is impressive, but the software is what actually matters. Tesla isn't winning the humanoid robot race because it built the best mechanical structure. It's winning because it's the only company with both the AI expertise and the manufacturing scale to make a practical robot.

Tesla has spent the last decade collecting video data from millions of vehicles. That data has trained neural networks to understand driving, spatial reasoning, object recognition, and decision-making under uncertainty. That's not directly applicable to humanoid robots, but the way Tesla approaches AI development is. They think in terms of learning from real-world data, not in terms of hand-coded rules.

Optimus learns in two ways. First, it learns from observation. Tesla engineers demonstrate a task to the robot, and the AI extracts the key steps. Not through explicit programming, but through video analysis. What are the critical waypoints? What's the hand doing relative to the object? What sensors are reading in terms of force and position? After seeing a task 10-20 times, the robot can do it independently.

Second, it learns from correction. When a robot makes a mistake, engineers correct it, and the AI updates its model. It's similar to how humans learn—you try something, you get feedback, you adjust. This means robots get better over time at a specific facility. The robot deployed to your warehouse learns your warehouse's quirks—the slightly bent door frame, the uneven floor, the specific way boxes are stacked.

The real competitive advantage is data scale. Tesla can deploy thousands of Optimus robots, collect data from all of them, train the AI model on that aggregated data, and push updates to all robots simultaneously. That creates a feedback loop that competitors can't match. Every mistake one robot makes teaches every robot something. Every success one robot has, they all benefit from.

Cost Economics: Why the Numbers Actually Work

For Optimus Gen 3 to be more than a novelty, the economics have to work. And they're starting to.

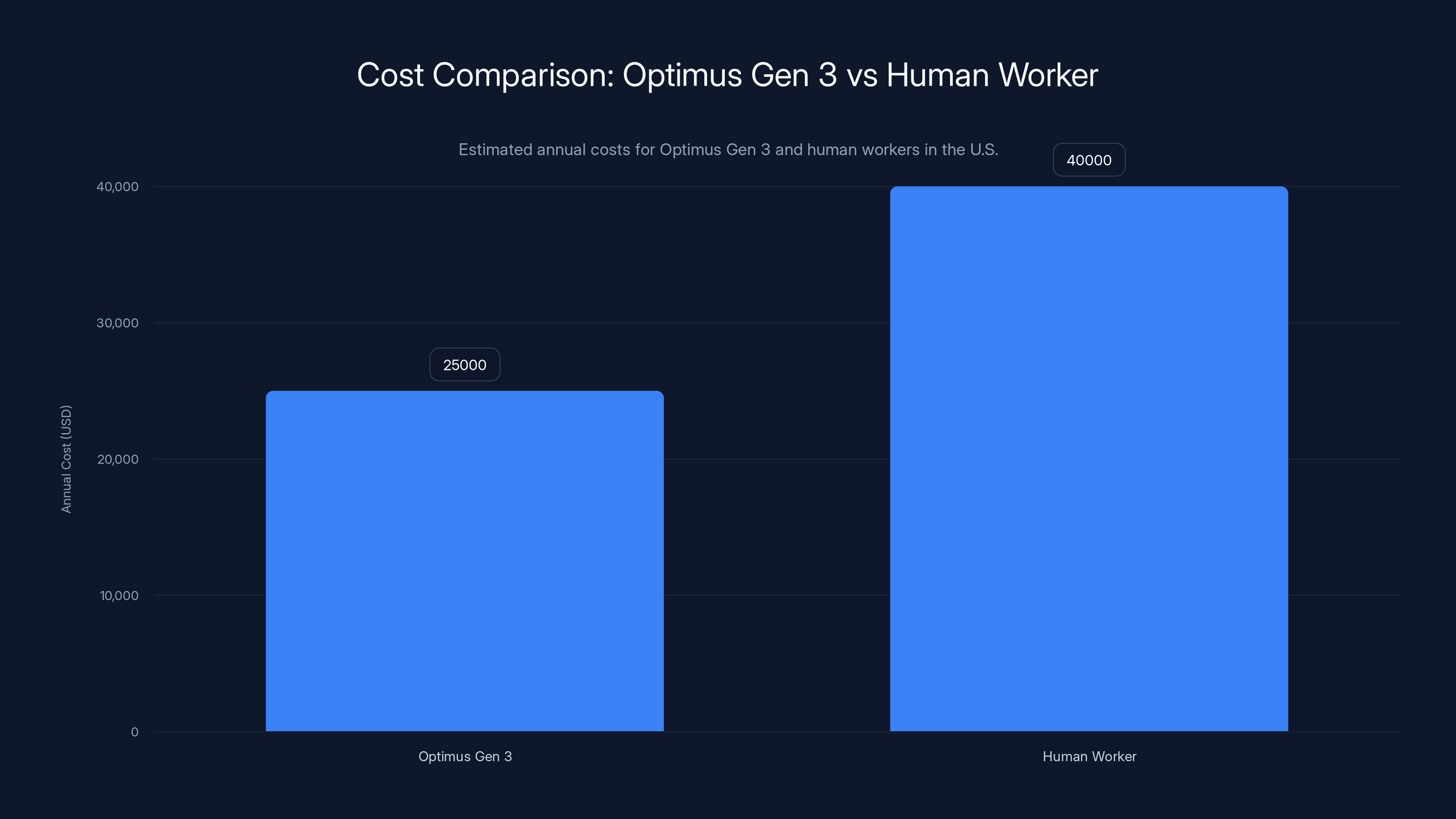

Tesla hasn't released final pricing, but estimates suggest Optimus Gen 3 will cost somewhere between

So the math is: one robot costs

That's in the United States. In countries where labor is cheaper, the robot makes less economic sense. In countries where labor is expensive—Scandinavia, Switzerland, Japan—the robot makes immediate economic sense. This suggests Optimus deployment will follow labor costs, not geography.

But there are secondary cost factors too. A warehouse with robots doesn't need climate control as much. Robots work in heat and cold that humans find unbearable. You need less safety infrastructure because robots don't get hurt. You need less floor space because robots can work in tighter areas than humans safely can. You need less insurance and fewer workers' compensation reserves.

There's also the consistency factor. A human picking items might make a small mistake every few hundred items. That costs money in returns, shipping, and customer service. A robot doesn't make those mistakes. That's real savings, even if it's harder to quantify than labor costs.

Optimus Gen 3 can be deployed in 3-4 weeks, significantly faster than the 6-12 months required for traditional robots. Estimated data based on typical deployment scenarios.

Safety Concerns and Human-Robot Collaboration

Anyone watching a robot work around humans naturally asks: what happens if something goes wrong? Can the robot hurt someone? What happens if the robot fails?

Optimus Gen 3 is designed with safety as a primary constraint, not an afterthought. The weight is relatively modest—about 125 pounds. That's not nothing, but it's far less dangerous than a 500-pound industrial robot arm. If Optimus loses power and falls, it's not going to crush someone. It's more like an adult human falling, which is why all robots are trained to fall safely.

The movement speed is capped. Optimus doesn't move at the speeds it's mechanically capable of achieving. It moves at speeds where humans can react if necessary. When working around people, the speeds can be reduced further. This is similar to how forklifts operate at reduced speed in pedestrian areas.

The sensing system includes redundancy. If one sensor fails, the robot doesn't continue blindly. It stops and waits for human direction. The force feedback prevents the robot from crushing things unintentionally. If something unexpected happens, the robot is trained to release its grip rather than applying more force.

But here's the honest truth: a robot is still dangerous in the same way any powerful industrial equipment is dangerous. You wouldn't let untrained people operate around a forklift, and you won't let untrained people work unsupervised with a humanoid robot. This doesn't mean humans can't work alongside robots—it means proper training and protocols are necessary.

What's actually different from traditional industrial automation is the level of collaboration possible. A traditional robot arm bolted to a worktable requires safety cages because it can't stop safely or understand what's happening around it. Optimus can see you, understand that you're there, and adjust its movement accordingly. That enables collaboration that's not possible with traditional robots.

Timeline and Scale: When Does This Actually Happen?

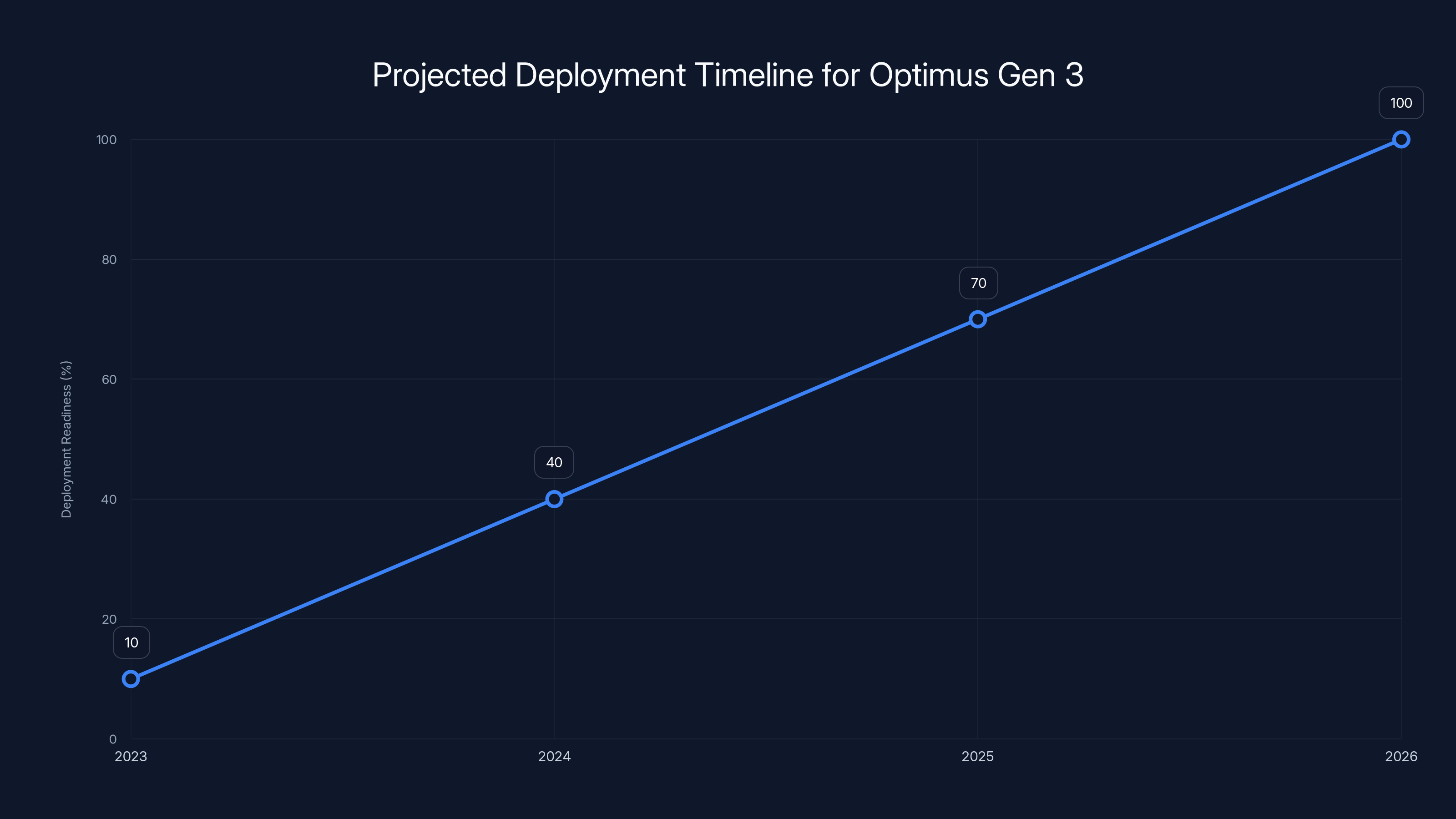

Tesla's timeline has been aggressive, and executives have suggested meaningful deployment by 2025-2027. That might sound absurdly fast, but context matters. Tesla is not starting from zero—they have manufacturing expertise, AI capabilities, and capital. Their timeline for deploying Optimus is probably faster than any other company's could realistically be.

Here's a realistic timeline based on what's been public:

2025: Limited production (thousands, not tens of thousands). Initial deployments in Tesla facilities for internal testing and refinement. Early adopters in manufacturing and logistics start receiving units. Small-scale deployments to demonstrate viability to skeptical industries.

2026-2027: Production scales to tens of thousands. Integration with enterprise workflows becomes standard. Insurance and regulatory frameworks start to crystallize. Competing humanoid robots from other companies become viable but slower to deploy.

2028+: Production at scale (hundreds of thousands potentially). Optimus becomes a normal part of manufacturing and logistics infrastructure, similar to how automated forklifts are standard now.

This matters because the question isn't "will humanoid robots exist?" They do. The question is "will they be affordable enough to deploy at scale?" The timeline determines when the economic shift actually happens.

Optimus Gen 3 is expected to be ready for meaningful deployment within 2-4 years, with readiness increasing rapidly from 2023 to 2026. Estimated data.

The Competitive Landscape: Who Else Is Building Humanoid Robots?

Tesla isn't alone in the humanoid robot space, but it's ahead. Understanding the competition helps you understand why Optimus Gen 3 is actually significant.

Boston Dynamics has been developing humanoid robots for years. Their Atlas robot is incredibly impressive from an engineering perspective—it can do backflips and parkour-style movement. But Boston Dynamics has explicitly said they're not building a commercial product. They're a research company. That's both honest and limiting. Their robots are science projects, not products you can buy and deploy.

Figure AI is building a humanoid robot called Figure 01 with backing from Open AI and other investors. Figure 01 looks similar to Optimus and is positioned similarly. The main difference is that Figure is further behind in development timeline and has less manufacturing expertise. Figure is building the robot. Tesla is building the robot and the factory and the training pipeline and the deployment infrastructure. That integration is hard to match.

Honda has its Asimo robot, which predates the humanoid robot trend. Honda has basically abandoned Asimo to focus on other robotics. Toyota has humanoid robots but hasn't aggressively commercialized them. BMW and other manufacturers have dabbled in humanoid robots for factory work but haven't committed to mass production.

The competitive advantage Tesla has is: Vertical integration. Tesla builds the hardware, writes the software, trains the AI, manufactures at scale, and handles deployment. Other companies are typically strong in one or two of these areas.

Data advantage. Every Optimus deployed feeds data back into the model. Every mistake teaches the system. Every success gets shared across all units. This creates a compounding advantage that's hard to overcome.

Critical mass. Tesla is deploying thousands of units. That creates enough deployment experience to find and fix issues before competitors even launch products. When you're first at scale, you learn faster than everyone else.

Capital and urgency. Tesla has the money to bet on this, the factories to build it, and leadership that seems committed to the timeline. Most competitors are treating humanoid robots as a side project.

Labor Market Disruption: The Honest Conversation

Optimus Gen 3 is not going to instantly eliminate jobs. But it will reshape labor markets over 5-10 years in ways that governments and companies are not prepared for. The honest version of this conversation requires naming both the real risks and the context they sit in.

The jobs most at risk are in manufacturing, logistics, and warehouse work. These are currently dominated by workers without college degrees. They're physically demanding but don't require specialized training. Optimus is basically perfect for replacing these jobs because it's designed to do exactly this work.

In the United States, roughly 3 million people work in warehouses and fulfillment centers. Logistics workers number even higher. These are real people supporting families. If robots eliminate half these jobs over 5-10 years, that's a massive disruption.

But here's the context: these jobs are already disappearing, just slower. Automation has been steadily replacing warehouse workers for years. Optimus accelerates that timeline but doesn't create it. The real question is whether policy can keep pace with technology. If it can't, you get serious unemployment in specific regions and demographics. If it can, you get retraining programs, jobs in robot maintenance and deployment, and economic growth that's distributed more fairly.

Secondary effects matter too. If robots do warehouse work cheaper than humans, customers pay less for shipping. That's genuinely good for consumers, particularly lower-income people for whom shipping costs matter. Economic growth from cheaper goods can create new jobs. But that only happens if policy supports it. Without education and retraining support, you get a literal lost generation of workers in affected regions.

The political economy of this is messy because it cuts across usual political divides. Business prefers robots for the cost savings. Labor opposes robots for the job losses. But individual workers are in a weird spot where learning to work with robots might be the best career move, even if collectively workers would be better off with stronger anti-automation policies.

There's also the international dimension. Countries that adopt humanoid robots early get a productivity boost. Countries that don't fall behind. This means once a few countries deploy Optimus at scale, other countries have to follow or become uncompetitive. That's a prisoner's dilemma where everyone has incentive to adopt, even if everyone would be better off not adopting.

Integration Challenges: Why This Is Harder Than It Looks

Tesla can build a great robot. Deploying that robot at scale to hundreds of different companies, each with different workflows and expectations, is a completely different problem.

Integration with existing systems is one part. A warehouse might have decades-old software managing inventory, routing, and logistics. Optimus needs to work with that system. It needs to understand what jobs it's supposed to do, where to get items, where to put them, and how to report back. This isn't hard engineering-wise, but it's tedious integration work across many systems.

Training is another part. You can't just deploy a robot to a warehouse and expect it to work. Someone has to train the robot on the warehouse layout. Someone has to teach it the specific tasks required. Someone has to maintain it, fix it, and update it. These are jobs that don't exist yet. Companies will need to hire "robot operators" or "robot technicians" who understand how to work with these systems. That's a bottleneck for scaling.

Trust is maybe the biggest issue. Managers at a facility have had humans doing a job a certain way for years. Those managers trust that humans will work reasonably hard and deliver expected results. A robot is unknown. What if the robot is less effective than expected? What if it breaks and nobody knows how to fix it? What if workers are upset about working alongside robots? These are business risks, not technical risks, and they slow adoption.

Regulation is still uncertain. Most places don't have clear regulatory frameworks for deploying humanoid robots in workplaces. Insurance companies don't know how to price the risk. Liability is unclear—if a robot injures someone, who's responsible? Workers' compensation systems assume workers, not robots. These legal ambiguities slow deployment.

The Future: Where Does This Go From Here?

Optimus Gen 3 is not the endpoint. It's a waypoint on a trajectory that's pretty clear: robots will get better, cheaper, and more capable. The question is how fast and how far.

Next-generation improvements are already obvious. Better dexterity in the hands—more joints, better sensors, faster movement. Better sensing—cameras that work in more lighting conditions, sensors that detect more nuanced properties of objects. Better AI—robots that learn from fewer examples, that understand more complex instructions, that coordinate better with humans.

Within 5-10 years, expect humanoid robots that are as competent at general physical tasks as an average human. Not necessarily faster or stronger, but more versatile, more reliable, and cheaper to operate.

The real endpoint, which is probably 20+ years away, is general-purpose robots that can do almost any physical task in any environment without special configuration. That's the point at which economic disruption becomes undeniable and policies become critical. We're not there yet. Optimus Gen 3 is good but still specialized—it's great at warehouse work, okay at manufacturing, helpful in logistics. It's not the universal robot yet.

What's happening now is the foundation being laid. Companies are deploying robots, learning how to work with them, identifying which tasks are suitable for automation, and understanding the real costs and benefits. By the time truly general-purpose robots exist, there will be a decade of institutional knowledge about how to work with them.

Why Optimus Matters More Than You Think

The final thing worth understanding is why this specific robot, at this specific moment, matters for things beyond robotics.

Optimus Gen 3 represents a proof point that AI plus robotics at scale is actually viable. For years, AI companies talked about having the technology to make useful robots. But talking and shipping are different things. Tesla is actually shipping robots. That changes what's possible.

Second, it validates the business model. If robots actually save money and increase productivity, other companies will invest. That drives competition, which drives innovation and cost reduction. Within 5-10 years, humanoid robots won't be novelty items. They'll be normal industrial equipment, like forklifts are today.

Third, it forces policy conversations that have been avoided. Governments need to think about education and retraining. Companies need to think about workforce transition. Workers need to think about skill development. These conversations are hard and uncomfortable. But avoiding them makes things worse. A robot that actually works forces these conversations.

Lastly, Optimus is culturally significant in a way that's hard to articulate but important. Robots have been science fiction for decades. They were always five to ten years away. Optimus Gen 3 is not five years away—it's here. People will interact with it, work alongside it, maybe depend on it. That changes how we think about technology and work and what the future actually is.

FAQ

What is Tesla's Optimus Gen 3?

Optimus Gen 3 is a humanoid robot developed by Tesla that stands about 5 feet 8 inches tall and weighs roughly 125 pounds. It's designed to perform general physical tasks in human environments, with particular emphasis on smooth, human-like movement, precise hand dexterity, and the ability to learn new tasks through demonstration. The robot combines advanced actuators, distributed sensors, and AI-powered learning to move naturally and adapt to different work environments.

How does Optimus Gen 3 work?

Optimus Gen 3 operates using a combination of distributed electric motors at each joint, sophisticated force and position sensors throughout its body, and AI systems that continuously adjust movement based on environmental feedback. The robot learns tasks through observation—engineers demonstrate a task multiple times, and the AI extracts the critical steps and hand positions. Once trained, the robot can perform the task independently, improving its accuracy through corrections from human operators. The robot navigates spaces using vision systems and lidar, maintains balance through dynamic adjustment of joint angles, and adapts grip pressure automatically using force feedback from its hands.

What tasks can Optimus Gen 3 perform in manufacturing?

In manufacturing settings, Optimus Gen 3 can handle assembly line tasks, parts sorting and bin picking, product movement between stations, quality inspection, and packaging operations. The robot excels at repetitive tasks that require precision and consistency but can also adapt to variations in how items are positioned or presented. Unlike traditional industrial robots bolted to specific locations, Optimus can walk between different workstations, making it useful for tasks that require movement across a facility floor.

Why is human-like movement important for a robot?

Human-like movement matters because it reduces the infrastructure required for deployment. A robot that walks naturally can navigate warehouses and factories designed for humans without modification. It can use tools designed for human hands. It can work in spaces with humans without requiring dedicated safety cages. Human-like movement also means smoother, more efficient operation, which translates to lower energy costs and less wear on mechanical components. Finally, people intuitively understand how a robot that moves like a human will behave, making it easier for humans to collaborate with the robot without special training.

What are the cost economics of deploying Optimus Gen 3?

Tesla estimates Optimus will cost between

What are the main safety concerns with humanoid robots in workplaces?

Optimus Gen 3 is relatively safe compared to traditional industrial robots because it weighs only about 125 pounds and its movement speeds are capped at levels where humans can react if necessary. The robot includes multiple redundant sensors, and if something unexpected happens, it's designed to release its grip or stop rather than applying more force. However, deploying robots around humans still requires proper training, safety protocols, and clear operational guidelines. The robot needs to be supervised initially, and workers need to understand how to work safely around it. Like any industrial equipment, misuse or inadequate oversight can cause injuries.

How quickly will Optimus Gen 3 be deployed at scale?

Based on Tesla's stated timeline, limited production involving thousands of units could occur in 2025. Broader deployment in manufacturing and logistics industries could scale significantly between 2026-2027. Production reaching tens of thousands annually seems realistic within 2-3 years, with hundreds of thousands possible beyond that. However, actual timeline depends on solving integration challenges with existing business systems, developing a training and maintenance infrastructure, and overcoming organizational inertia in industries that have used human labor for decades.

What happens to workers whose jobs are replaced by robots like Optimus?

This is the most challenging question with no simple answer. Jobs in warehousing, manufacturing, and logistics are most at risk of automation. However, job displacement will happen gradually (over 5-10 years likely) rather than overnight. The real issue is whether policy and education systems can support workforce transition. New jobs will emerge in robot maintenance, deployment, operation, and industries that arise from lower logistics costs. Without proactive retraining programs and education investment, workers in affected regions face unemployment and economic hardship. This is fundamentally a policy problem, not a technical one.

How does Optimus Gen 3 compare to other humanoid robots in development?

Optimus has significant advantages over competing humanoid robots because Tesla has integrated hardware design, manufacturing expertise, AI capabilities, and deployment infrastructure. Boston Dynamics' Atlas is more mechanically impressive but isn't being commercialized. Figure AI's Figure 01 is similar but further behind in development and lacks Tesla's manufacturing scale. Other companies like Honda and Toyota have humanoid robots but haven't committed to mass production. Tesla's integration of all these components—design, manufacturing, software, AI, and deployment—is what creates a competitive advantage that's difficult for other companies to match quickly.

What skill-based jobs emerge as manufacturing becomes more automated?

As robots handle physical tasks, demand grows for jobs in robot maintenance, programming, calibration, and deployment management. Machine learning engineers, roboticists, and AI specialists will be in high demand. Quality assurance roles shift from checking physical products to monitoring robot performance. Supply chain and logistics professionals need skills in working with autonomous systems. Additionally, higher-wage jobs in design, engineering, data analysis, and business strategy grow as automation unlocks new capabilities and markets. The problem is these high-skill jobs don't automatically go to people displaced from warehouse work without significant retraining and education.

The Bottom Line

Tesla's Optimus Gen 3 isn't a distant future concept or a research project anymore. It's a product that works, that's being deployed, and that will reshape manufacturing, logistics, and service industries over the next 5-10 years. The human-like design and movement aren't just engineering flexing—they're the key to practical deployment because they let robots work in human environments without massive infrastructure changes.

The real significance of Optimus Gen 3 is that it forces the conversation about automation from theoretical to practical. It's not hypothetical anymore. Companies need to decide whether to adopt robots. Workers need to think about their skills. Governments need to think about policy. Investors need to think about what industries actually look like in 2030.

None of this is guaranteed to play out as smoothly as the optimistic scenarios. Integration challenges, regulatory uncertainty, and workforce transition problems are real obstacles. But the technology is real too, and it's good enough that the economic case for deployment is strong.

The humanoid robots are coming. They're not coming in 10 years or "someday." They're coming in the next 2-4 years, starting with manufacturing and logistics, spreading to other industries as capabilities improve and costs drop. That's not prediction. That's what's already happening.

The question now isn't whether this future exists. It's how prepared we are for it. That depends on decisions people make starting right now—in education systems, policy debates, and business decisions. Optimus Gen 3 is the forcing function that makes those decisions real and urgent.

Key Takeaways

- Optimus Gen 3's human-like movement design solves practical deployment challenges that mechanical designs couldn't address

- Economic case for robot deployment becomes viable in year one when fully accounting for human labor costs and benefits in developed economies

- AI learning capabilities allow individual robots to improve over time and adapt to facility-specific conditions without reprogramming

- Deployment timeline of 2025-2027 suggests major labor market disruption in warehouse, logistics, and manufacturing sectors within 5-10 years

- Competitive advantage stems from Tesla's vertical integration of hardware, AI, manufacturing, and deployment infrastructure, not just robotics innovation

Related Articles

- Tesla Optimus Gen 3: Everything About the 2026 Humanoid Robot [2025]

- Tesla is No Longer an EV Company: Elon Musk's Pivot to Robotics [2025]

- Tesla Discontinues Model S and X to Focus on Optimus Robots [2025]

- Tesla Kills Model S and X Production: The Shift to Humanoid Robots [2025]

- Tesla Discontinuing Model S and Model X for Optimus Robots [2025]

- Tesla's $2B xAI Investment: What It Means for AI and Robotics [2025]

![Tesla Optimus Gen 3: The Humanoid Robot Reshaping Industry [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/tesla-optimus-gen-3-the-humanoid-robot-reshaping-industry-20/image-1-1769711896211.jpg)