Introduction: When Self-Driving Cars Meet Real-World Chaos

On January 17, 2025, a Zoox robotaxi collided with a parked car on a busy San Francisco street. The driver of the parked vehicle opened his door into the robot's path. His hand got smashed. The autonomous vehicle's glass door got damaged. And suddenly, we weren't talking about the future of robotaxis anymore.

We were talking about liability, safety systems, and whether machines can actually handle the unpredictable nature of urban driving.

This wasn't some edge case in a testing facility with perfect conditions. This was a robotaxi operating under Amazon's ownership, running a public pilot program, on a real street in one of America's most complex driving environments. The San Francisco Police Department launched an investigation. The California Department of Motor Vehicles got involved. And Zoox issued a statement about "suddenly opened" doors as if a door opening on a parked car was something the company's engineers couldn't possibly have anticipated.

Here's the thing: they should have.

This incident cuts straight to the heart of the autonomous vehicle debate that's been raging since self-driving technology first emerged. We talk about lidar, radar, machine learning, and perception systems. We talk about safety records and comparative risk. We talk about a future where human error is eliminated from the road.

But we rarely talk about what happens when an autonomous vehicle encounters the kind of chaotic, illogical human behavior that's actually normal on city streets.

What follows is a deep dive into the Zoox collision, the investigation into what happened, the broader context of autonomous vehicle safety, and what this incident reveals about how far self-driving technology still has to go before it can truly claim superiority over human drivers. We'll examine the technical aspects of autonomous perception systems, explore the liability questions that are still unsolved, and look at how the industry is responding to a growing number of high-profile accidents.

Because here's what's becoming clear: the biggest challenge for autonomous vehicles isn't traveling at speed on a highway. It's navigating the messy, unpredictable reality of urban driving where parked cars suddenly have doors, pedestrians ignore traffic rules, and nothing follows the carefully optimized patterns that AI systems are designed to handle.

TL; DR

- The Incident: A Zoox robotaxi struck the open door of a parked 1977 Cadillac Coupe De Ville on January 17, 2025, injuring the car owner's hand and damaging the autonomous vehicle

- Key Question: Whether autonomous vehicles can detect and avoid collisions when people behave unpredictably, such as suddenly opening car doors into traffic

- Safety Implications: The collision raises concerns about autonomous perception systems and whether current technology is truly ready for widespread urban deployment

- Regulatory Response: Both SFPD and the California DMV launched investigations, requesting crash reports and incident details

- Broader Context: This is one of several recent incidents involving Zoox and other autonomous vehicle operators, signaling ongoing safety challenges in the industry

- Industry Trend: As robotaxis expand from controlled routes to public pilots, collisions and technical issues are becoming more frequent, not less

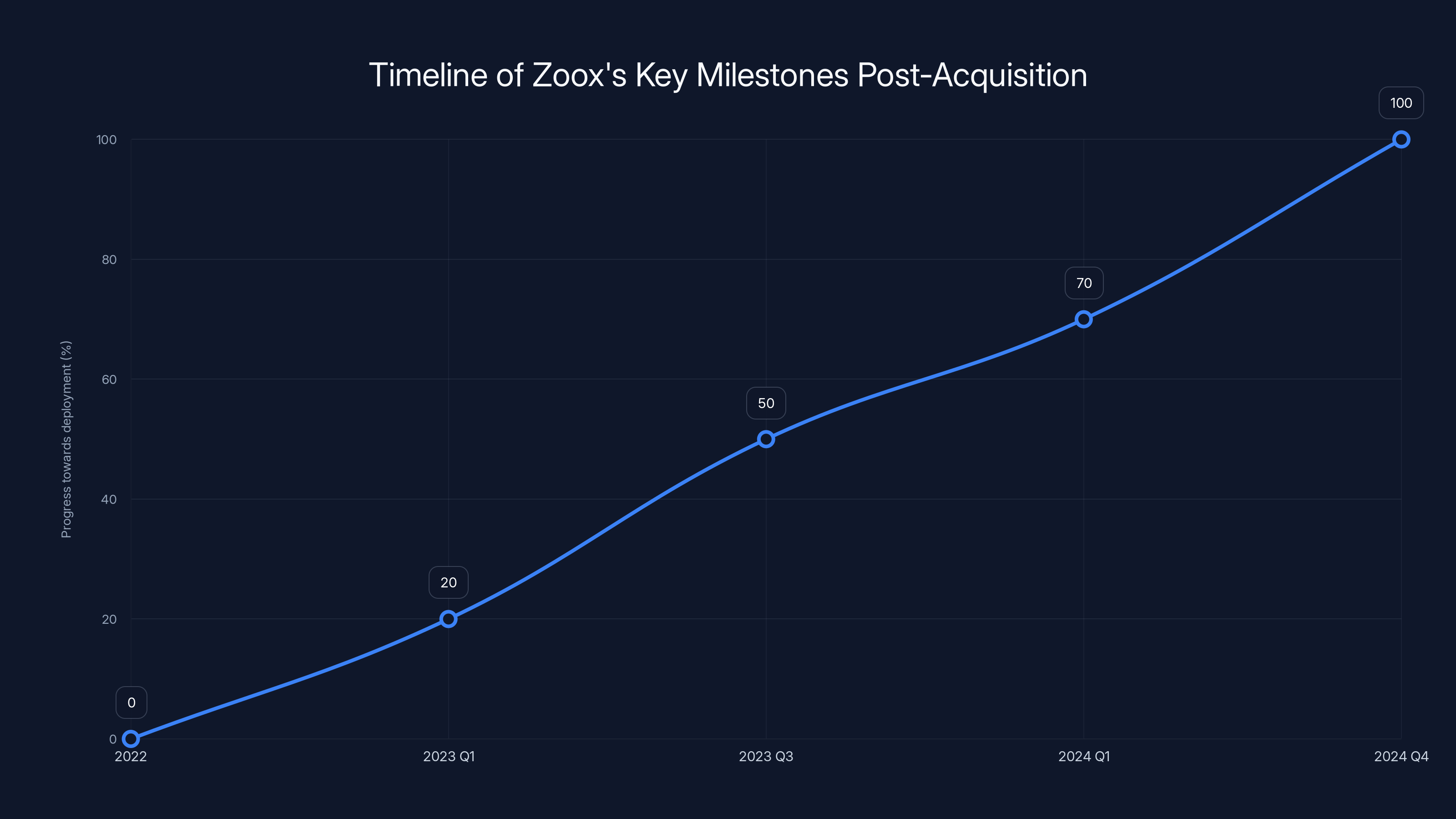

Zoox's progress towards deployment accelerated post-acquisition, with significant milestones reached by late 2024. Estimated data based on typical industry timelines.

The Incident: What Actually Happened on 15th and Mission

Let's establish the facts, because there's already conflicting narratives about what went down.

At approximately 2 p.m. on January 17, 2025, a Zoox robotaxi was traveling westbound along 15th Street in San Francisco, near the Mission Street intersection. A street ambassador named Jamel Durden was standing beside his 1977 Cadillac Coupe De Ville, a classic car he likely had pride in. When the robotaxi approached, Durden opened the driver's side door.

The autonomous vehicle collided with that open door.

Durden's hand was smashed in the collision. The Zoox vehicle sustained damage to its glass doors. There was a Zoox employee passenger inside the robotaxi at the time—something not initially reported but confirmed by SFPD to Tech Crunch. That passenger was uninjured.

Here's where the narratives diverge.

Zoox's official statement says Durden "suddenly opened" the door "into the path of the robotaxi." This framing matters because it places responsibility on human behavior—the unpredictable action of a person opening a car door. From Zoox's perspective, they're saying the robotaxi detected the opening door and "tried to avoid it but contact was unavoidable."

But contact wasn't unavoidable. Not really.

The robotaxi was traveling on a street with parked cars. Parked cars have doors. People open those doors. This isn't a rare, unforeseeable edge case. This is baseline urban driving reality that autonomous vehicles encounter dozens of times daily on any city street.

The San Francisco Police Department told Tech Crunch they couldn't release an incident report because the investigation was still open. The DMV told Tech Crunch that Zoox filed a crash report "in compliance with California regulations," but that report wasn't made publicly available. We're left with partial information and competing claims about what the robotaxi could or couldn't have done.

What we do know: Zoox offered medical attention to Durden. Durden initially refused treatment, or rather, he wanted his car towed before seeking help. This suggests he was more concerned about his vehicle than immediate medical care, which might indicate the injury wasn't severe, or might indicate he was in shock and prioritizing his car. We don't have enough context.

What we also know: This is the second notable incident involving Zoox in recent months. In December 2024, the company issued a recall to fix an issue where some vehicles were crossing center lanes and blocking crosswalks. That's not a minor glitch. That's a fundamental perception problem.

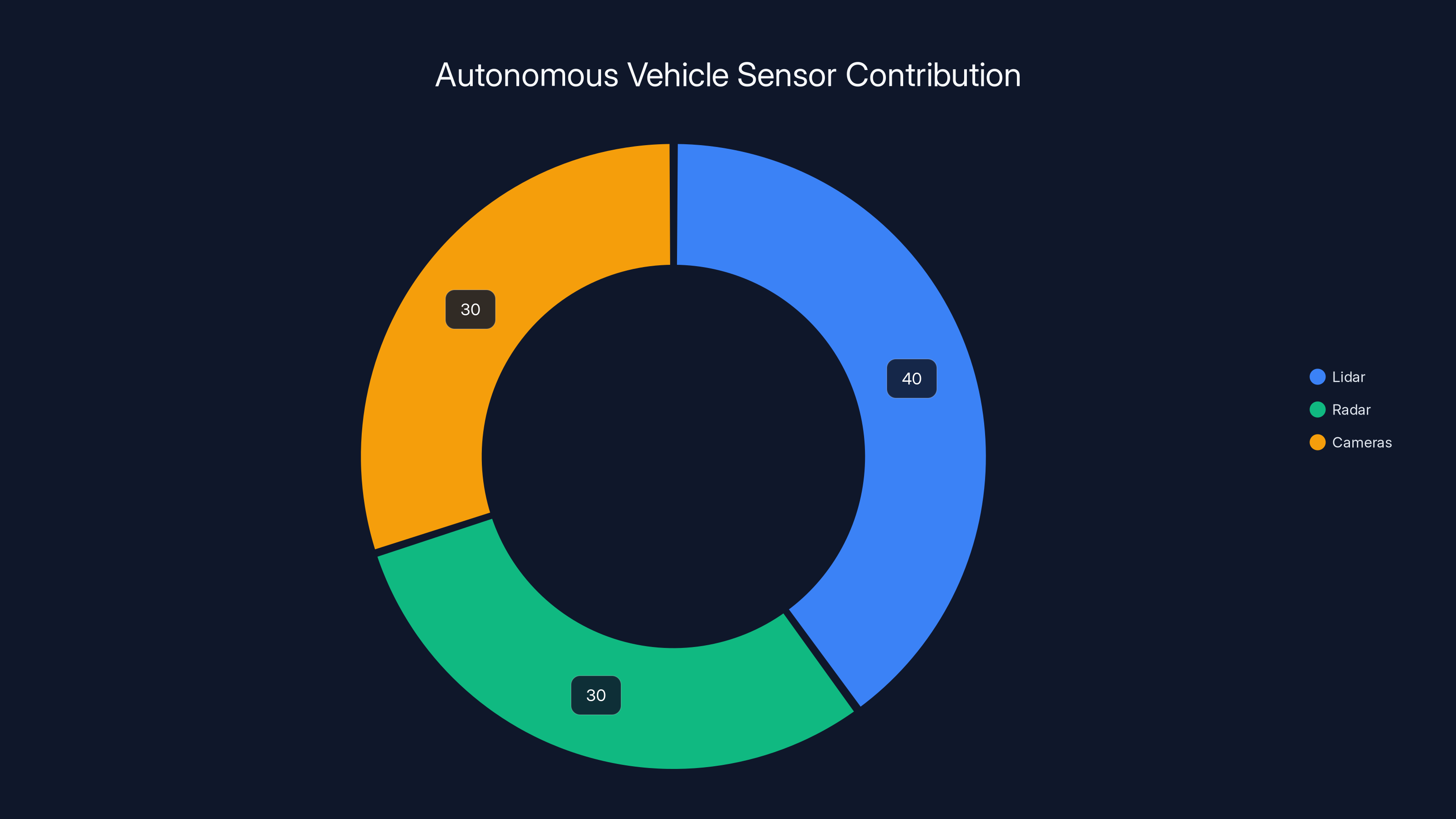

Estimated data shows lidar contributes 40%, while radar and cameras each contribute 30% to object detection in autonomous vehicles.

Understanding Autonomous Vehicle Perception Systems

To understand what the Zoox robotaxi should have been able to do, you need to understand how autonomous vehicles actually see the world.

Unlike human drivers who use primarily vision and rely on experience and intuition, autonomous vehicles use multiple sensor types working in concert. This is called sensor fusion, and it's supposed to be one of the key advantages of self-driving technology.

The primary sensors are lidar, radar, and cameras. Lidar (Light Detection and Ranging) shoots out laser pulses and measures how long they take to bounce back. This creates a precise 3D point cloud of everything around the vehicle. Unlike cameras, lidar works in darkness and isn't fooled by reflections or shadows. Radar works similarly but with radio waves, and it's particularly good at detecting moving objects. Cameras provide visual context that the other sensors can't.

When these sensors are working correctly, they should provide complete environmental awareness. An autonomous vehicle should be able to detect a car door opening because the door changes the geometry of the parked car. The lidar point cloud would show the door moving outward. The radar might pick up the motion. The cameras would show visual evidence of the door opening.

In theory, Zoox's robotaxi should have detected this. The robotaxi wasn't moving at highway speed where reaction time becomes impossible. It was moving through an urban environment where speeds are typically under 25 mph. The vehicle had sensor fusion. The company claims the system detected the opening door and tried to avoid it.

If it tried to avoid it but failed, that's a failure of the perception system, the planning system, or the control system. Maybe the lidar reading was noisy and the system couldn't confirm the door was actually opening. Maybe the planning algorithm determined that swerving would be more dangerous than proceeding. Maybe the control system couldn't execute the maneuver fast enough.

But here's the fundamental problem: we don't know. And neither does the public, because the investigation details are sealed.

Human drivers encounter car doors opening into traffic all the time. Most of them avoid collisions by driving defensively, maintaining space, and being prepared to brake or swerve. Experienced drivers learn patterns: cars parked on busy streets, cars with occupants visible inside, the likelihood that someone might open a door. Autonomous vehicles have to learn these patterns from training data, and the training data has to be comprehensive enough to cover edge cases.

Zoox clearly didn't have enough edge case coverage for this scenario.

The Role of the Amazon Acquisition and Pressure to Expand

Zoox was acquired by Amazon in 2022 for a reported $1.2 billion. That acquisition came with expectations.

Amazon doesn't buy robotaxi companies to keep them in slow, careful development phases. Amazon buys them to deploy them and generate revenue. The Zoox acquisition made strategic sense for Amazon: autonomous vehicles represent a potential future for last-mile delivery, a critical component of Amazon's logistics network. If robotaxis can navigate city streets safely and reliably, they can also deliver packages.

So in November 2024, less than two years after the acquisition, Zoox launched the "Zoox Explorer" early rider program in San Francisco. Free rides to the public. In a major city. With complex driving conditions.

That's aggressive deployment.

The company was also running a similar program in Las Vegas. Multiple cities. Multiple vehicles. Multiple opportunities for things to go wrong.

This deployment pressure creates a subtle but powerful incentive structure. Engineers are working toward launch dates. Product teams are managing timelines. Safety testing is happening, but it's happening in the context of a company owned by one of the world's largest corporations eager to bring autonomous vehicles to market.

None of this is necessarily malicious. Engineers want safe vehicles. Safety teams want thorough testing. But organizational pressure toward deployment can create subtle biases in risk assessment. When your timeline says you need to be operational in Q4, and you find an edge case issue in Q3, there's pressure to decide whether that edge case is truly critical or whether it's rare enough that you can deploy with mitigations.

The December recall suggests that Zoox found at least one edge case—vehicles crossing center lanes and blocking crosswalks—serious enough to stop operations and fix. But how many other edge cases did the system encounter before that one became a recall? How many minor incidents happened in the early rider program that didn't result in collisions?

We don't know, because that data isn't public.

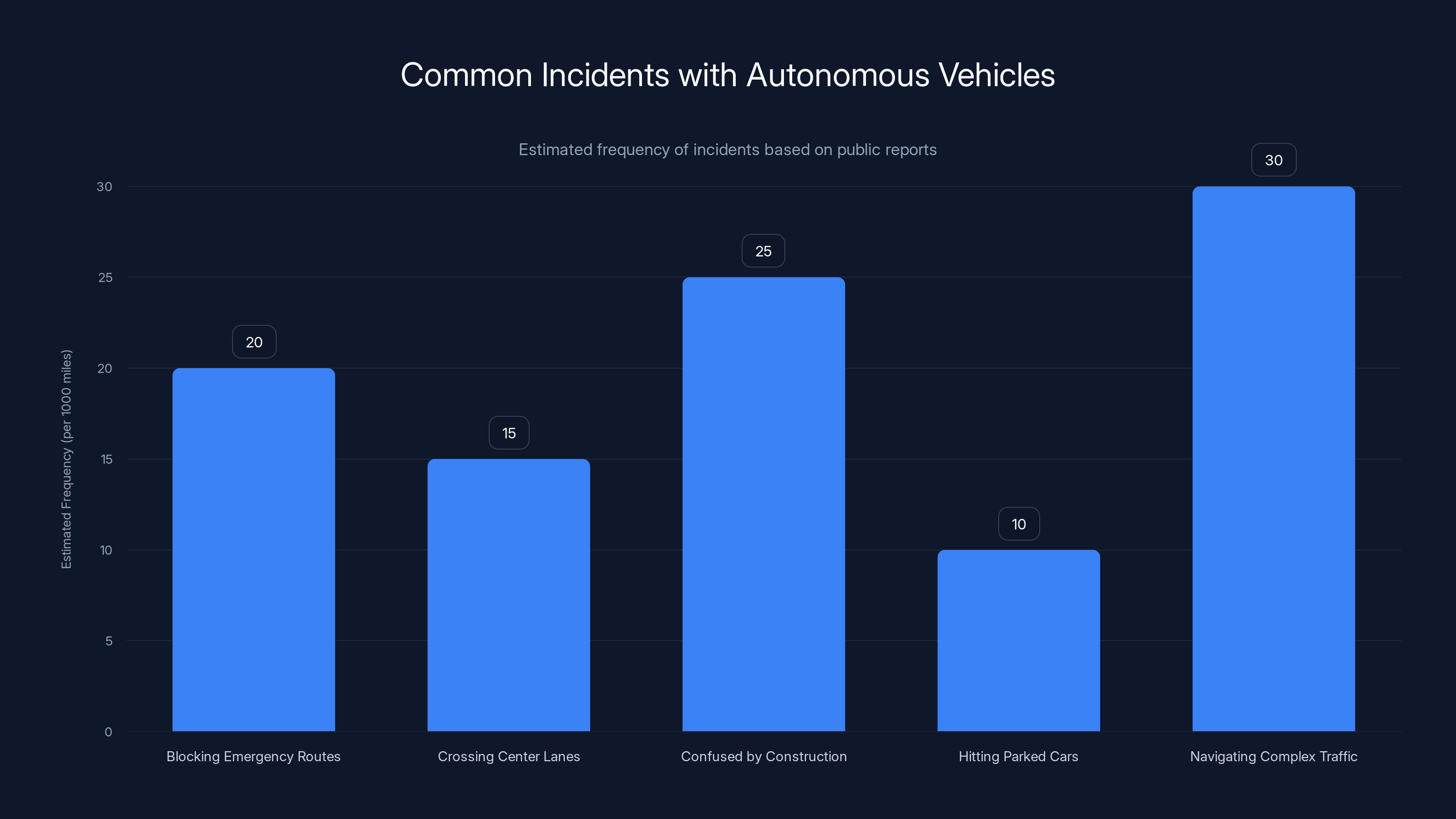

Estimated data suggests that autonomous vehicles frequently encounter edge cases, such as navigating complex traffic and dealing with construction, which highlights areas for improvement in handling urban driving complexity.

Liability Questions: Who's Responsible When a Robotaxi Hits a Parked Car

Here's where the legal questions become murky, and also where the "suddenly opened door" narrative starts to matter more.

In traditional vehicle law, the driver of a vehicle is responsible for maintaining control and avoiding collisions. If you hit a parked car, you're usually found at fault, even if the parked car's owner did something that contributed to the collision. The moving vehicle has the primary responsibility to avoid striking stationary objects.

But autonomous vehicles complicate this significantly.

If a human driver was driving the Zoox robotaxi, they would almost certainly be found liable for hitting the car. The law expects drivers to anticipate that parked cars might have people opening doors. You're supposed to slow down, maintain distance, and prepare to brake or swerve.

But a robotaxi isn't a human driver. It's a system. So is the liability on:

- Zoox as the manufacturer, for building a perception/planning/control system that couldn't handle a car door opening?

- The owner/operator of the robotaxi, for deploying it on public streets before it was ready?

- The human passenger on the robotaxi, who might have had the ability to intervene?

- The human street ambassador, for opening a car door without checking for traffic?

Legal precedent doesn't clearly answer these questions. No state has comprehensively addressed autonomous vehicle liability in the specific case of a collision caused by what could be described as an edge case in human behavior.

Zoox's statement about the door being "suddenly opened" does important rhetorical work here. If the door opened suddenly and unpredictably, it's harder to argue that the robotaxi should have avoided it. If the door opened normally, and the robotaxi's perception system just didn't detect it, that's a safety defect in the autonomous vehicle.

But here's the thing about car doors: they don't open suddenly from nothing. There's a mechanical sequence. You have to reach for the handle. You have to pull. The door hinges have friction. The process takes about a second. An autonomous vehicle with functioning sensor fusion should be able to detect the door handle being reached for, the initial movement of the door, and the widening gap between the door and the frame.

If Zoox's system couldn't detect this, that's a system limitation. And if the system was deployed publicly anyway, that's a safety judgment call made by the company.

The investigation might eventually shed light on whether the robotaxi's sensors detected the opening door. If they did, and the planning system still chose to collide, that's a failure of the planning algorithm. If they didn't, that's a failure of perception. Either way, it's a failure of the autonomous vehicle system.

Durden might have legal grounds for a personal injury claim against Zoox. The parked car might have damage coverage that will dispute claims with Zoox's insurance. And depending on how the investigation unfolds, there could be regulatory consequences.

California's Department of Motor Vehicles has the authority to suspend or revoke Zoox's autonomous vehicle testing license. Whether they use that authority depends on their assessment of whether this was an isolated incident or a sign of deeper safety problems.

Previous Zoox Incidents and the Pattern Emerging

The January 17 collision isn't Zoox's first public relations problem.

In December 2024, just a few weeks before the collision, Zoox issued a recall notice. The issue: some vehicles were crossing center lanes and blocking crosswalks. This is not a minor glitch. Crossing center lanes in urban environments is dangerous and illegal. Blocking crosswalks prevents pedestrians from crossing and can cause traffic gridlock.

That Zoox needed to issue this recall suggests that the vehicles made it through development, testing, and into public operation with a pretty significant behavioral problem. The fact that the problem was caught and fixed before it became a major incident is good. But the fact that it happened at all is concerning.

Before that, there were incidents in Las Vegas, where Zoox also operates. There was a collision with a motorcycle, and various interactions with emergency vehicles that raised questions about how autonomous vehicles handle non-standard traffic situations.

The pattern that's emerging is this: Zoox's vehicles work well in structured, predictable situations. They navigate known routes. They follow traffic rules. But when the environment becomes unpredictable, the vehicles struggle.

This is actually a broader problem in the autonomous vehicle industry. Most of the successful testing and deployment has happened in relatively controlled environments. Phoenix, Arizona has seen successful Waymo robotaxi operations partly because the streets are grid-based, the weather is predictable, and the roads are well-maintained. San Francisco is the opposite: complex streets, unpredictable weather, densely packed parked cars, pedestrians who ignore traffic rules, and endless edge cases.

Zoox chose to deploy in the harder environment. That's aggressive. It's also exactly what Amazon likely wanted.

But aggressiveness in a controlled environment looks good. Aggressiveness in a chaotic real-world environment creates incidents.

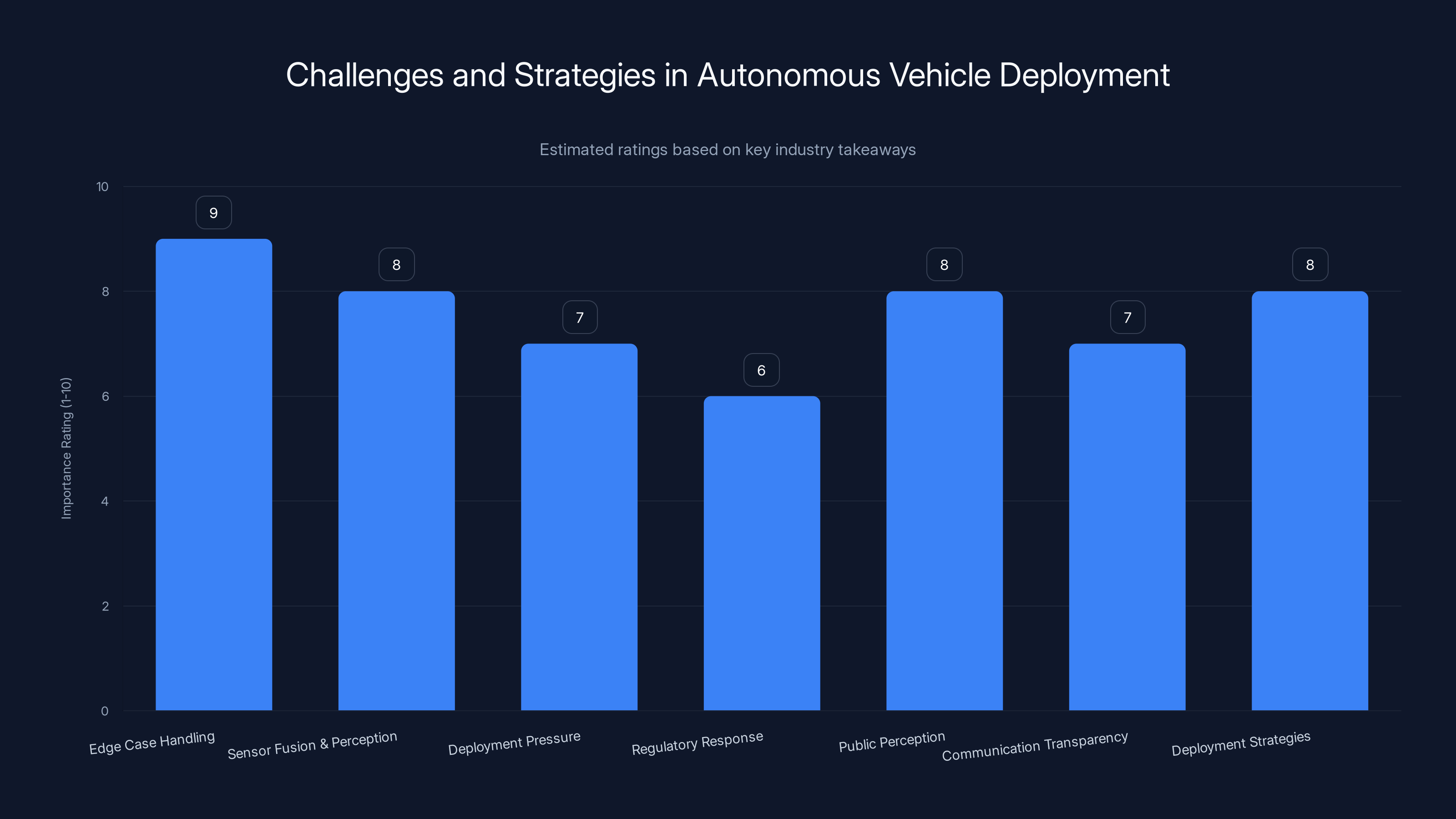

Edge case handling and public perception are rated as the most critical challenges for autonomous vehicle deployment. Estimated data based on industry insights.

The Investigation: What's Being Looked At and Why

The San Francisco Police Department's investigation into the collision is focused on determining what happened, whether any laws were broken, and whether any charges should be filed.

Durden opened a car door into the path of a vehicle. That's technically unsafe behavior, but is it illegal? In most jurisdictions, you're required to make sure the road is clear before opening a car door. If Durden opened the door without checking, he violated that rule.

But Zoox was operating a robotaxi—a vehicle that's supposed to be safer than human drivers. That's the entire sales pitch for autonomous vehicles. So even if Durden behaved unsafely, Zoox's vehicle should have been able to handle it.

The SFPD investigation is probably looking at:

- Sensor logs from the Zoox vehicle, to see what the robotaxi detected in the seconds before impact

- Video footage, from the robotaxi's cameras and any street cameras

- Witness statements, from the Zoox employee passenger and anyone else nearby

- Vehicle telemetry, showing the robotaxi's speed, trajectory, and attempted maneuvers

- Durden's account, of how and why he opened the door

The California DMV's investigation is focused on whether Zoox is operating safely and whether the company should be permitted to continue its public pilot program.

This is where regulatory standards matter. California regulates autonomous vehicles through a testing and deployment framework. Companies have to meet specific safety requirements to operate. The question is: does this incident demonstrate that Zoox hasn't met those requirements, or is it an isolated incident that could happen to any autonomous vehicle operator?

That's ultimately a judgment call, and it depends on what the investigation reveals.

If the Zoox sensors clearly detected the opening door and the system still collided, that's a safety defect that probably should result in suspension of the public pilot program until the issue is fixed.

If the sensors somehow missed the door opening, that's a sensor capability issue that's also problematic, but might be addressable through software improvements.

The outcome probably hinges on technical details that we might never see publicly. Crash investigation reports from the DMV sometimes become public, but investigation details can remain confidential, especially if there are ongoing legal disputes.

Comparison: How Other Autonomous Vehicle Operators Handle Edge Cases

Zoox isn't the only company operating robotaxis in San Francisco. Waymo has been operating there for years. Cruise operated there until its permit was suspended in 2023 following several high-profile incidents.

How do these companies' approaches differ?

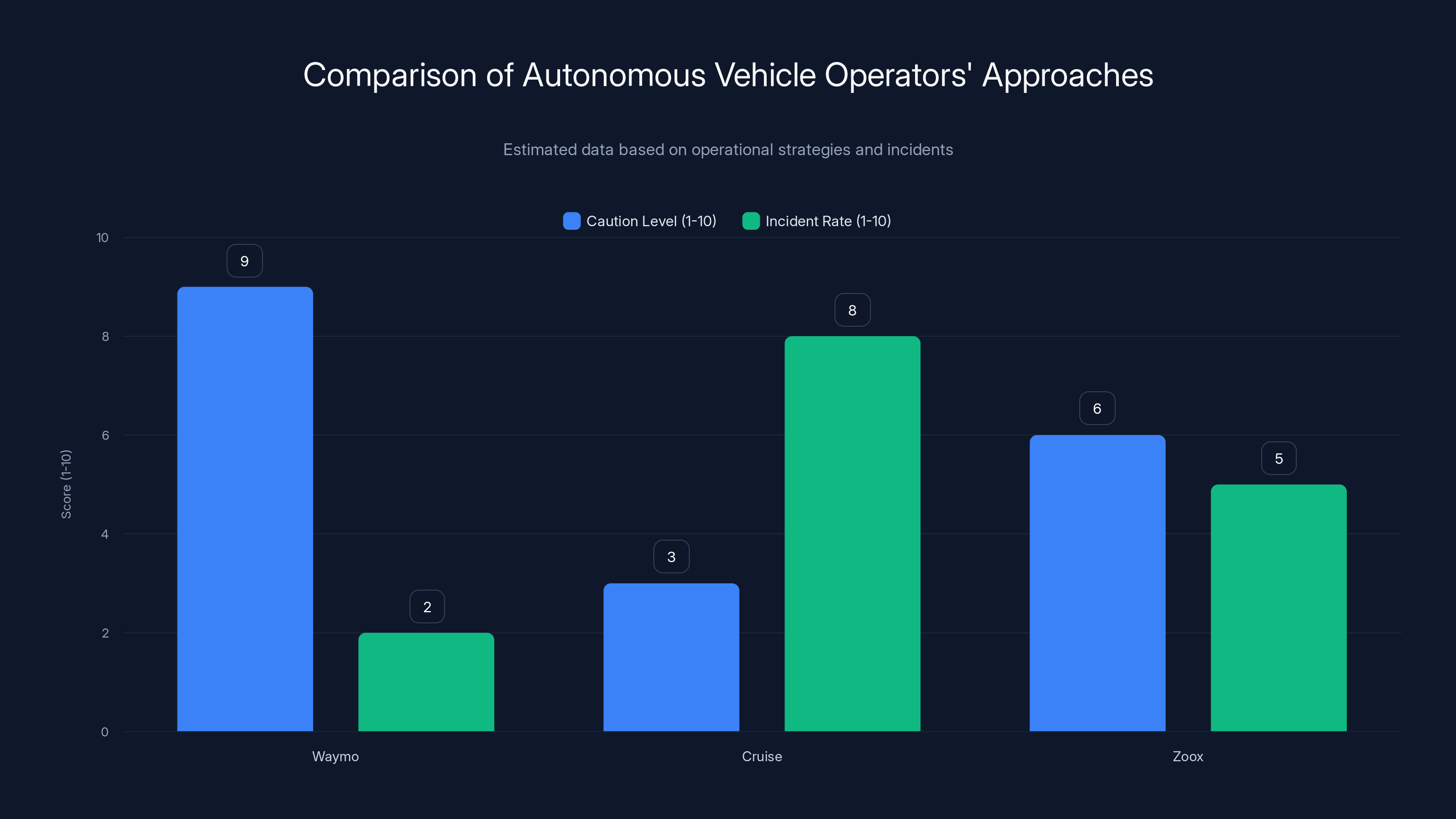

Waymo has taken a slower, more methodical approach. The company started operations in less complex environments (Phoenix, Arizona, then suburbs of San Francisco) before moving into dense urban areas. When Waymo started operating in San Francisco proper, it did so with extensive mapping, predetermined routes, and heavy testing in the actual deployment environment. Waymo also maintains a human safety driver in the vehicle for most of its operations, providing a fallback to human control if the autonomous system encounters something it can't handle.

Waymo's approach trades speed for confidence. The company hasn't rushed to expand rapidly. This slower deployment has resulted in fewer high-profile incidents.

Cruise was more aggressive. The company deployed robotaxis in San Francisco without human drivers, operating 24/7 in complex urban environments. In September 2023, a Cruise robotaxi was involved in a collision with an emergency vehicle that was responding to another accident. That incident, combined with other issues, led to Cruise's permit being suspended. The company later revealed it hadn't been fully transparent with regulators about all the incidents it had experienced.

Crude's approach tried to move fast and demonstrate capability quickly. This resulted in regulatory action and public backlash.

Zoox seems to be falling somewhere between Waymo's caution and Cruise's aggressiveness. The company launched a public pilot program in San Francisco, but limited it initially. The robotaxis operate on predetermined routes in specific neighborhoods. The company is gathering data and iterating.

But that's still more aggressive than Waymo's approach, and the collision is evidence that the aggressive approach comes with risks.

The right balance between speed and safety isn't obvious. Move too slowly and you're not making progress toward real-world deployment. Move too fast and you generate incidents that harm public trust.

Waymo exhibits the highest caution level with fewer incidents, while Cruise's aggressive approach led to more incidents. Zoox balances between caution and aggressiveness. (Estimated data)

The Broader Safety Question: Are Autonomous Vehicles Actually Safer

Here's the uncomfortable truth about autonomous vehicle safety: it's really hard to measure.

We have decades of data on human driver safety. We know how many accidents happen per mile driven. We can calculate injury rates and death rates. We have statistical baselines.

Autonomous vehicles are so new that we don't have comparable baseline data. The Zoox robotaxis have traveled tens of thousands of miles without serious incidents. That sounds good. But tens of thousands of miles is nothing compared to the billions of miles human drivers log annually in the United States.

To actually know whether autonomous vehicles are safer, we'd need to compare incident rates per mile for a large population of autonomous vehicles operating in the same conditions as human drivers, over a long time period, with standardized reporting of incidents.

We don't have that data. We probably won't have comprehensive data for several more years, as robotaxis accumulate millions and millions of miles across multiple operators.

What we do have is incident reports from public deployments. And those reports show that autonomous vehicles encounter edge cases frequently.

Cycle through the incidents:

- Robotaxis blocking emergency vehicle routes

- Robotaxis crossing center lanes

- Robotaxis confused by construction or road maintenance

- Robotaxis hitting parked cars with open doors

- Robotaxis unable to navigate complex multi-vehicle traffic situations

None of these incidents are inherently catastrophic. But collectively, they suggest that the technology isn't yet handling the full complexity of urban driving.

Human drivers handle edge cases intuitively. A human driver sees a parked car on a busy street and automatically anticipates that someone might open a door. They slow down. They maintain space. They prepare to brake or swerve. This anticipatory behavior is learned through years of experience and is probably deeply tied to our intuitive understanding of physics and human behavior.

Autonomous vehicles have to learn these patterns from data. And if the training data doesn't include enough examples of car doors opening into traffic, the system won't know how to handle it.

This is actually a fundamental challenge for deep learning based autonomous systems. You need training data that covers the distribution of real-world scenarios you'll encounter. If real-world driving is unpredictable and diverse, you need enormous amounts of training data. And even then, you'll encounter novel situations the system has never seen before.

Regulatory Response and What Happens Next

California's Department of Motor Vehicles is the primary regulator of autonomous vehicles in the state. The DMV has authority to issue autonomous vehicle testing permits and operating permits. Violations of safety requirements can result in permit suspension or revocation.

What happens after an investigation depends on what's found and how the DMV interprets the findings.

If the investigation shows that Zoox's vehicle functioned as designed and the collision was caused by unpredictable human behavior, the DMV might not impose strong penalties. They might ask for safety improvements or additional testing, but permit operations to continue.

If the investigation shows that Zoox's vehicle has a safety defect, the DMV could impose a temporary permit suspension, require additional testing, or revoke the permit entirely.

Historically, the DMV has been fairly permissive with autonomous vehicle companies. California's regulatory approach has been to enable innovation while maintaining baseline safety standards. But that approach is tested every time there's an incident.

Public pressure matters too. If Durden's hand injury becomes a more serious injury, or if there's a pattern of similar incidents, public pressure on the DMV to impose stricter penalties would increase.

Zoox will likely argue that one collision doesn't indicate a systemic safety problem. Tens of thousands of miles with one major incident is pretty good. Human drivers would be proud of that record.

But autonomous vehicles are held to a different standard. They're supposed to be better than human drivers. When an autonomous vehicle has an incident that a careful human driver would have avoided, it falls short of that standard.

The collision with the parked car—specifically, a collision that occurred because the vehicle hit an open car door—is exactly the kind of situation a defensive human driver would avoid.

Zoox will need to demonstrate that the vehicle's behavior doesn't represent a broader perception or planning problem. If investigations show that the robotaxi's perception system detected the opening door but the planning system still collided, that's a planning problem. If the perception system didn't detect the door, that's a perception problem. Either way, it's a problem.

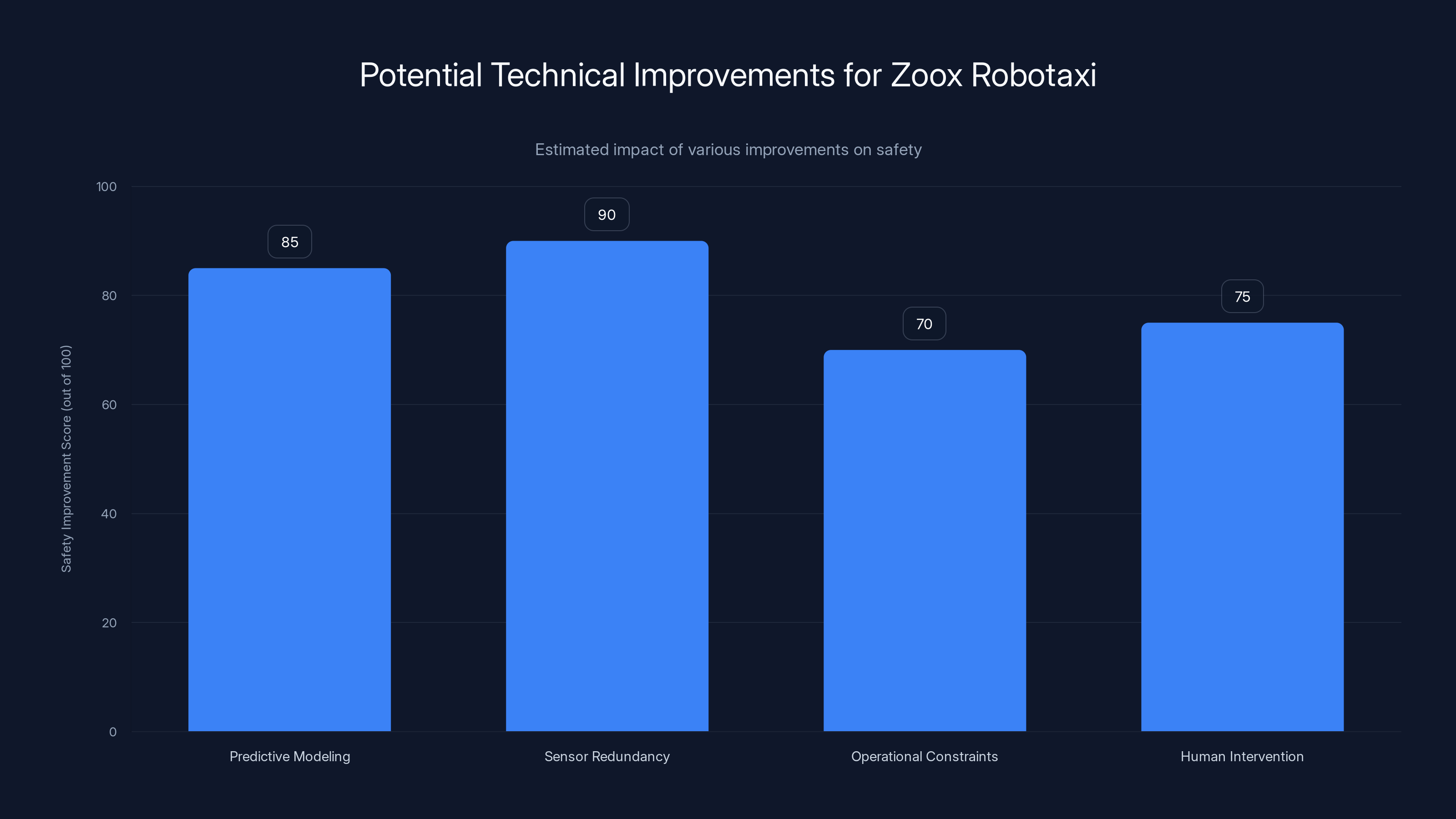

Estimated data suggests that enhancing sensor redundancy could have the highest impact on improving safety, followed closely by predictive modeling of human behavior.

The Role of Public Perception and Trust

There's a critical factor that doesn't appear in regulatory frameworks or technical investigations: public trust.

Autonomous vehicles need public acceptance to succeed at scale. People need to be willing to get in robotaxis, to share roads with autonomous trucks, to accept a future where machines handle most driving tasks.

Each incident erodes that trust a little bit.

When people hear that a robotaxi hit a parked car, they don't think about the technical details of sensor fusion or the statistical likelihood of the incident recurring. They think: "That machine hit something. How safe is it really?"

Zoox's statement about the "suddenly opened" door is actually a direct appeal to public perception. The company is trying to frame the incident as something unexpected and unpredictable, rather than something the vehicle should have handled.

But that framing might backfire. Car doors open regularly on parked cars. That's not suddenly or unpredictable. If a robotaxi can't handle normal urban driving scenarios like car doors opening, how is it safe to operate?

Compare this to Waymo's approach. Waymo moves carefully, gathers data methodically, and when incidents happen (and they do), the company is usually transparent about the technical details. This builds confidence that the company is solving problems systematically rather than deploying vehicles that aren't ready.

Zoox seems to be optimizing for speed and market presence. That creates risk. Not just technical risk, but trust risk.

For autonomous vehicle adoption to succeed, the industry needs public confidence. Each incident that seems preventable erodes that confidence. And a collision with a car door that the vehicle should have detected is pretty clearly preventable.

Technical Improvements: What Zoox and Others Can Do

Assuming the investigation concludes that the Zoox robotaxi had technical limitations that contributed to the collision, what can be done?

Several technical improvements could reduce the likelihood of similar incidents:

1. Predictive Modeling of Human Behavior

Autonomous vehicles could improve their planning algorithms to predict human behavior. When a car is parked on a busy street with the door closed and a human visible in the driver's seat or in the car, the probability of the door opening is non-zero. A planning algorithm could treat this as a risk factor and reduce speed, increase following distance, or prepare evasive maneuvers.

This is actually possible with existing deep learning techniques. You'd need training data that includes many examples of people opening car doors, but that's a solvable problem.

2. Enhanced Sensor Redundancy

A car door opening involves motion. Lidar can detect the motion of the door. Radar can detect the motion. Cameras can see the door opening. If any of the three sensors fails to detect the door movement, the other two should still catch it.

The problem is sensor fusion failures. If the lidar is noisy, or if one sensor's data is weighted too heavily, the fused output might miss the door opening even if individual sensors detected it. Better sensor fusion algorithms and better sensor calibration could help.

3. Operational Constraints

While the robotaxi operates in San Francisco, Zoox could impose operational constraints to reduce risk: lower speed limits in areas with dense parking, increased following distance behind parked cars, reduced operations on peak parking hours, etc.

This would reduce the company's operating efficiency, but it would also reduce risk.

4. Human Intervention in Ambiguous Situations

Zoox could implement a system where the robotaxi flags situations it's uncertain about and requests human intervention. If a car appears to have occupants and the vehicle is driving past it, the system could alert a remote human operator: "Car appears occupied, recommend caution." The human operator could then provide guidance or temporarily take control.

This would add operational overhead, but it would prevent incidents.

Waymo uses this approach with human safety drivers in the vehicle. That's more resource-intensive, but it's proven to work.

Industry-Wide Lessons: What This Incident Teaches

The Zoox collision isn't isolated. It's part of a pattern we're seeing across the autonomous vehicle industry.

Companies are deploying autonomous vehicles in public spaces before the technology has solved key edge cases. The reason is understandable: you can't develop a truly safe autonomous vehicle without real-world data. You need to see how the system behaves in diverse, complex, unpredictable situations.

But the transition from controlled testing to public deployment is where the risk lives. Public pilots are necessary, but they need to be designed carefully, with appropriate safety margins and fallbacks.

Zoox's incident suggests the company might have underestimated the difficulty of edge case handling in dense urban environments.

Waymo's slower approach might actually be the more rational one from a pure safety perspective, even if it's less exciting from a market perspective.

The fundamental lesson: autonomous vehicle companies need to be honest about what their systems can and can't do. They need to operate within those constraints, even if that means slower deployment and reduced operational efficiency.

Public trust is the constraint that matters most. If the public loses confidence that autonomous vehicles are safe, the entire industry suffers.

Future of Zoox and San Francisco Autonomous Vehicle Operations

Zoox will probably continue operating in San Francisco, assuming the investigation doesn't uncover evidence of systematic safety defects.

The January collision is unfortunate, but it's not catastrophic. The injury to Durden was limited. The vehicle damage was fixable. No one died.

Zoox will likely make technical improvements based on the investigation findings. The company will probably work with the DMV to implement additional safety measures or operational constraints.

The bigger question is whether this incident changes the trajectory of autonomous vehicle deployment in San Francisco.

San Francisco is the hardest market. The city is dense, complex, and full of edge cases. It's the perfect place to test autonomous vehicle safety limits, which means it's also the place where incidents are most likely.

If autonomous vehicles can't operate safely in San Francisco, they can't operate safely anywhere. But if Zoox and other operators learn from incidents and continuously improve, eventually the technology might mature enough to handle San Francisco traffic without issues.

That's going to take time. Probably measured in years, not months.

Meanwhile, Zoox's pilot program in Las Vegas, where conditions are simpler and more predictable, will probably continue uninterrupted. That's where the company can gather safe operational data and prove the concept.

San Francisco remains the ultimate proving ground.

FAQ

What caused the Zoox robotaxi collision on January 17, 2025?

A Zoox robotaxi collided with the open door of a parked 1977 Cadillac Coupe De Ville when the vehicle's owner, street ambassador Jamel Durden, opened the driver's side door into the path of the moving autonomous vehicle. Zoox's official statement says the robotaxi detected the opening door and attempted to avoid the collision, but contact was unavoidable. The investigation into what the vehicle's sensors actually detected and what response systems were engaged is still ongoing.

Is Zoox's robotaxi being suspended from operation?

As of the date of this incident, there has been no public announcement of a suspension. The San Francisco Police Department and California Department of Motor Vehicles launched investigations into the collision, but investigations typically take weeks or months. Zoox continues operating its public pilot program in San Francisco, though the company has indicated it is cooperating fully with authorities and may implement additional safety measures based on investigation findings.

How do autonomous vehicle perception systems detect objects like opening car doors?

Autonomous vehicles use sensor fusion, which combines data from lidar (laser-based 3D sensing), radar, and cameras. When a car door opens, the geometry of the parked car changes, which should be detectable by lidar's 3D point cloud. Radar detects the motion of the opening door. Cameras provide visual confirmation. If all three sensor types are functioning correctly and properly fused, an opening car door should be detectable. The collision suggests that either one or more sensors failed to detect the door, or the planning algorithm didn't interpret the sensor data as sufficient reason to avoid the collision.

What are the liability implications of the Zoox collision?

Liability for autonomous vehicle collisions is complex and largely unsettled in law. Typically, the operator of the moving vehicle bears primary responsibility for avoiding stationary objects. However, the occupant of the parked car may share responsibility for opening the door without checking for traffic. From a regulatory standpoint, the California DMV could determine that the collision resulted from inadequate autonomous vehicle safety systems, which could trigger permit suspension or revocation. From a civil standpoint, Durden may have grounds for a personal injury claim against Zoox, and his vehicle insurance may dispute liability with Zoox's insurance.

How does this Zoox collision compare to other autonomous vehicle incidents?

The Zoox collision is one of several incidents reported in the autonomous vehicle industry in recent months. Cruise, which operated robotaxis in San Francisco, had its permit suspended in 2023 following multiple incidents. Zoox itself issued a recall in December 2024 for vehicles crossing center lanes. The pattern suggests that autonomous vehicles encounter edge cases more frequently than proponents expected, and some companies may be deploying technology before it's fully mature for complex urban environments. Waymo, by contrast, has had fewer reported incidents, partly because the company has pursued a more cautious, methodical deployment strategy.

Will the Zoox collision affect autonomous vehicle adoption in California?

A single collision is unlikely to have dramatic regulatory impact, but repeated incidents could. The collision does highlight the gap between how autonomous vehicles are expected to perform and how they actually perform in complex, real-world scenarios. Public perception of autonomous vehicle safety is critical for adoption, and incidents that seem preventable—like hitting a parked car with an open door—can erode public confidence. From a regulatory perspective, the California DMV may impose additional safety requirements or operational constraints on Zoox and other operators, which could slow deployment and increase costs.

What technical improvements could prevent similar collisions?

Several technical approaches could reduce the risk of similar incidents: improved sensor fusion algorithms that combine data from multiple sensors more effectively, predictive models of human behavior that identify high-risk situations (like open doors on busy streets), enhanced sensor redundancy so that failure of one sensor doesn't result in missed detection, operational constraints like reduced speed near dense parking, and human-in-the-loop systems where ambiguous situations are escalated to human operators. Most of these improvements are technically feasible but require additional development effort and may reduce operational efficiency.

Is Zoox owned by Amazon, and does that affect the company's approach?

Yes, Amazon acquired Zoox in 2022 for approximately $1.2 billion. Amazon owns and controls the robotaxi company, which likely creates pressure for faster deployment and market presence, compared to independent companies that might prioritize gradual development. However, Amazon also has reputational and legal incentives to ensure safe operations. The company's influence on Zoox's deployment strategy and safety priorities is not transparent, but the timing of the robotaxi pilot program launch (November 2024, shortly after the December 2024 recall) suggests some urgency around public deployment.

Conclusion: The Road Ahead for Autonomous Vehicles

The Zoox collision on January 17, 2025, is a moment where the theoretical claims about autonomous vehicle safety collide with real-world complexity.

Autonomous vehicle companies have made powerful promises. The technology will be safer than human drivers. It will eliminate the vast majority of accidents caused by human error. It will save lives.

But every incident reveals a gap between those promises and current reality.

The collision with the parked car isn't fundamentally different from thousands of driving scenarios that happen every day in San Francisco. A car is parked. Someone opens the door. A vehicle approaches. A careful human driver slows down and maintains space to avoid this exact scenario. The Zoox robotaxi didn't.

That's not because the technology is inherently incapable. It's because the deployment pushed the technology beyond where it's been adequately validated. Zoox decided that the robotaxi was ready for a public pilot program. The January incident suggests that decision was premature.

This doesn't mean autonomous vehicles are doomed. Technology improves through iteration, and real-world deployment generates valuable data for improvement. Zoox will learn from this incident. The company will implement technical changes. The robotaxi will probably handle similar situations better in the future.

But the path from current reality to the promised future of autonomous vehicles is longer than many companies have acknowledged. It requires solving not just technical problems, but problems of public trust and regulatory confidence.

Zoox has an opportunity to respond to this incident by being transparent about what went wrong, what technical improvements are being implemented, and what additional safety measures are being adopted. Transparency builds trust. Opaque statements about "suddenly opened doors" erode it.

The collision is ultimately a data point. It's one incident among thousands of miles of autonomous vehicle operation in San Francisco. But data points matter. They accumulate into patterns. If the pattern shows that autonomous vehicles are learning from incidents and becoming safer, adoption will accelerate. If the pattern shows that companies are deploying technology before it's ready and hoping incidents don't accumulate into scandals, adoption will stall.

Zoox is at an inflection point. The investigation will reveal technical facts about what the robotaxi detected and why it collided. Those facts will inform how regulators respond. And regulatory response will influence how quickly Zoox and other companies can deploy autonomous vehicles at scale.

The future of San Francisco transportation might depend on what happens next.

Key Takeaways for Industry Professionals

-

Edge case handling remains the fundamental challenge for autonomous vehicles operating in complex urban environments, not speed or highway navigation

-

Sensor fusion and perception systems must detect not just objects, but patterns of human behavior like opening parked car doors, which requires more sophisticated training data than most companies currently use

-

Deployment pressure from parent companies or investors can create subtle incentives to move faster than safety validation justifies, particularly in competitive markets

-

Regulatory response to incidents depends significantly on investigation details that are often kept confidential, making it difficult for the public to understand whether incidents indicate systemic problems or isolated failures

-

Public perception and trust are critical constraints that don't appear in technical specifications but fundamentally determine whether autonomous vehicles can achieve market adoption

-

Transparent communication about incidents and technical responses builds confidence more effectively than defensive explanations that shift blame to human behavior

-

Different deployment strategies (cautious like Waymo versus aggressive like Zoox and Cruise) produce different incident profiles, suggesting that pacing matters more than just having safe technology

-

Comparative incident rates over time and across companies will eventually provide the data needed to determine whether autonomous vehicles are genuinely safer than human drivers, but that data is years away from being conclusive

Related Articles

- Waymo's School Bus Problem: What the NTSB Investigation Reveals [2025]

- NTSB Investigates Waymo Robotaxis Illegally Passing School Buses [2025]

- Uber's AV Labs: How Data Collection Shapes Autonomous Vehicles [2025]

- Tesla Autopilot Death, Waymo Investigations, and the AV Reckoning [2025]

- Tesla's Fully Driverless Robotaxis in Austin: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Waymo's Miami Robotaxi Launch: What It Means for Autonomous Vehicles [2025]

![Autonomous Vehicle Safety: What the Zoox Collision Reveals [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/autonomous-vehicle-safety-what-the-zoox-collision-reveals-20/image-1-1769622152710.jpg)