Test-Time Training Discover: How AI Optimizes GPU Kernels 2x Faster Than Human Experts [2025]

Here's a problem that's been bugging machine learning teams for years: your language model gets trained once, locked in place, and that's it. You can prompt it, coax it with chain-of-thought reasoning, even throw more compute at inference—but fundamentally, those weights don't budge. The model's stuck working within whatever patterns it saw during training.

But what if you could flip that?

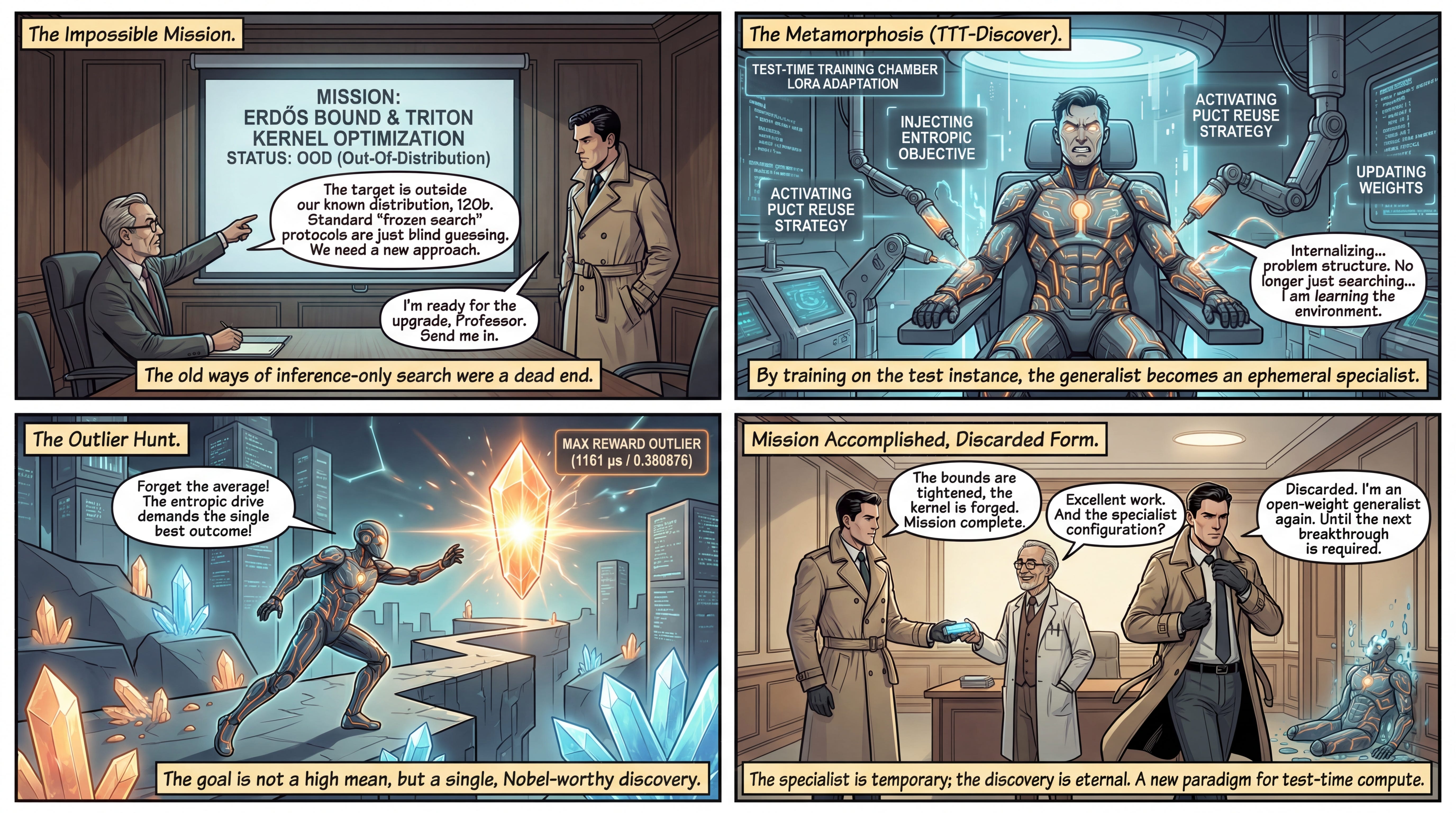

Researchers from Stanford University, Nvidia, and Together AI just published something that challenges this entire paradigm. Their technique, called Test-Time Training to Discover (TTT-Discover), does something wild: it keeps the model training during inference. Not just thinking longer or exploring search trees like you'd expect from a reasoning model. Actual weight updates, continuously adapting to the specific problem at hand.

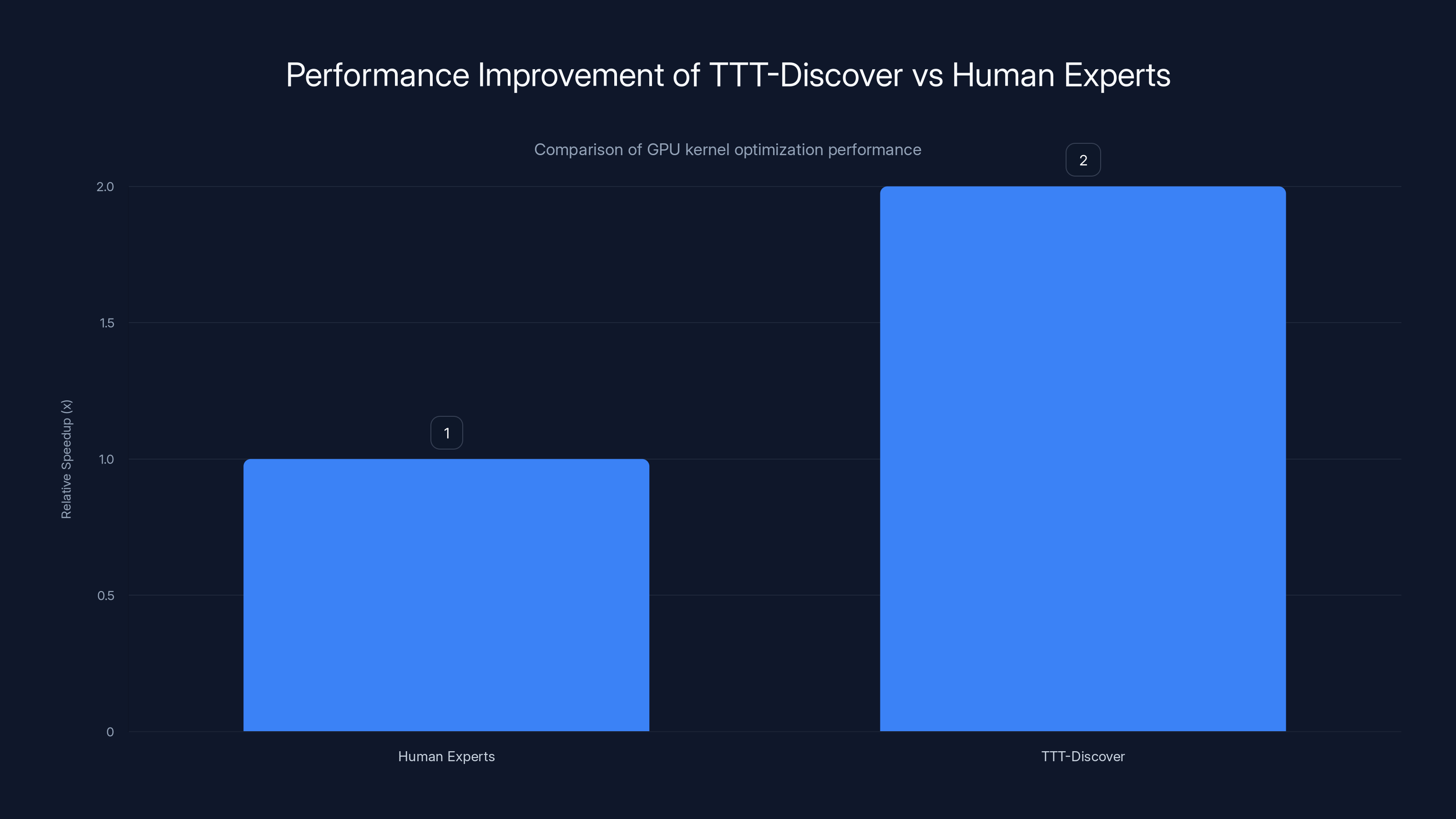

The results? They optimized a critical GPU kernel to run 2x faster than the previous state-of-the-art solution written by human experts. Not iteratively. Not through multiple tries. A single discovery run produced code that outpaced what domain experts had engineered.

This matters more than it sounds. For cloud providers, for enterprises running massive data pipelines, for researchers trying to solve problems that don't fit neatly into existing frameworks—this opens a door that was supposed to be locked.

Let's dig into what's actually happening, how it works, why it costs what it costs, and where this technology is heading.

TL; DR

- Test-Time Training means models update their weights during inference, not just at training time, allowing continuous adaptation to specific problems

- TTT-Discover produced a GPU kernel 2x faster than human expert solutions, with applications in code optimization, drug discovery, and material science

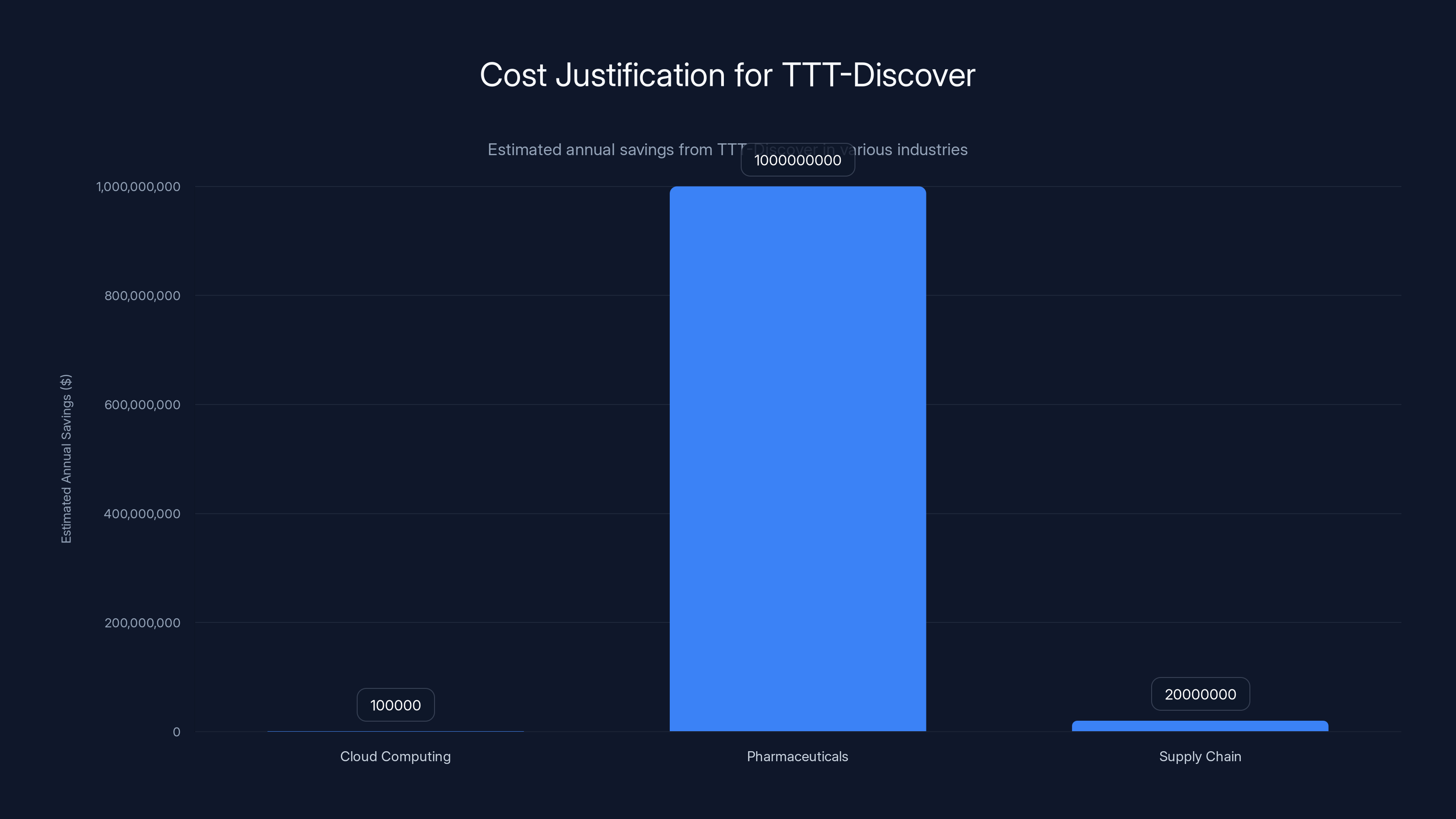

- The cost is ~$500 per discovery run, but ROI is massive for high-value optimization problems like cloud infrastructure or supply chain routing

- Continuous reward signals are critical, meaning the system works best on problems where you can measure incremental progress (microseconds gained, error rates dropping)

- This fundamentally shifts reasoning models away from generalist solutions toward specialized, single-problem artifacts that can be discarded after discovery

Estimated data shows that a $500 TTT-Discover run can lead to significant annual savings across different industries, justifying its cost.

The Problem With Frozen Models: Why Static Weights Fail at Discovery

Most AI systems today work the same way. You train a model on a dataset, lock in the weights, and deploy it. Whether you're using Chat GPT, Claude, or open-source alternatives, the model's parameters are fixed the moment you start using it. When you send a prompt, the model searches for an answer within the learned patterns of its training data.

This works beautifully for familiar problems. If you're asking it to summarize a document, translate text, or explain a concept that exists in abundance in the training data—frozen weights are fine. The model knows how to navigate that space.

But discovery problems are fundamentally different.

Take the GPU kernel optimization task. A kernel is a small piece of code that runs on graphics processors. It's highly specialized, often hand-tuned by engineers. Writing a faster kernel means finding a sequence of instructions that achieves the same output with fewer cycles, less memory overhead, or better cache utilization. This isn't pattern matching. This is invention.

Frozen models can't invent. They can rearrange existing patterns. They can combine known techniques in novel ways. But if the optimal solution requires a logical leap that doesn't exist in the training distribution—something truly out-of-distribution—a frozen model will struggle, no matter how much inference compute you throw at it.

Mert Yuksekgonul, a Stanford researcher and co-author of the TTT-Discover paper, framed this perfectly in an analogy to pure mathematics. Andrew Wiles spent seven years proving Fermat's Last Theorem. During those years, he wasn't just thinking harder about already-known techniques. He was learning, iterating on failed approaches, integrating insights from new fields into his thinking. He was updating his own understanding in real-time, making himself a different mathematician by the end of it.

A frozen model can't do that. It would need to have already understood all the mathematics that Wiles discovered during his seven years, which obviously it didn't.

That's the core limitation that TTT-Discover solves.

Understanding the Frozen Model Paradigm

To appreciate how radical test-time training is, let's look at why models are frozen in the first place.

Training a large language model is expensive. Brutally expensive. Training GPT-4 reportedly cost somewhere between

Further training after deployment raises questions: what data do you train on? How do you ensure the model doesn't overfit to a specific user's preferences? How do you manage versions when different users need different behaviors? It's a complexity nightmare, which is why most teams stick with the frozen approach.

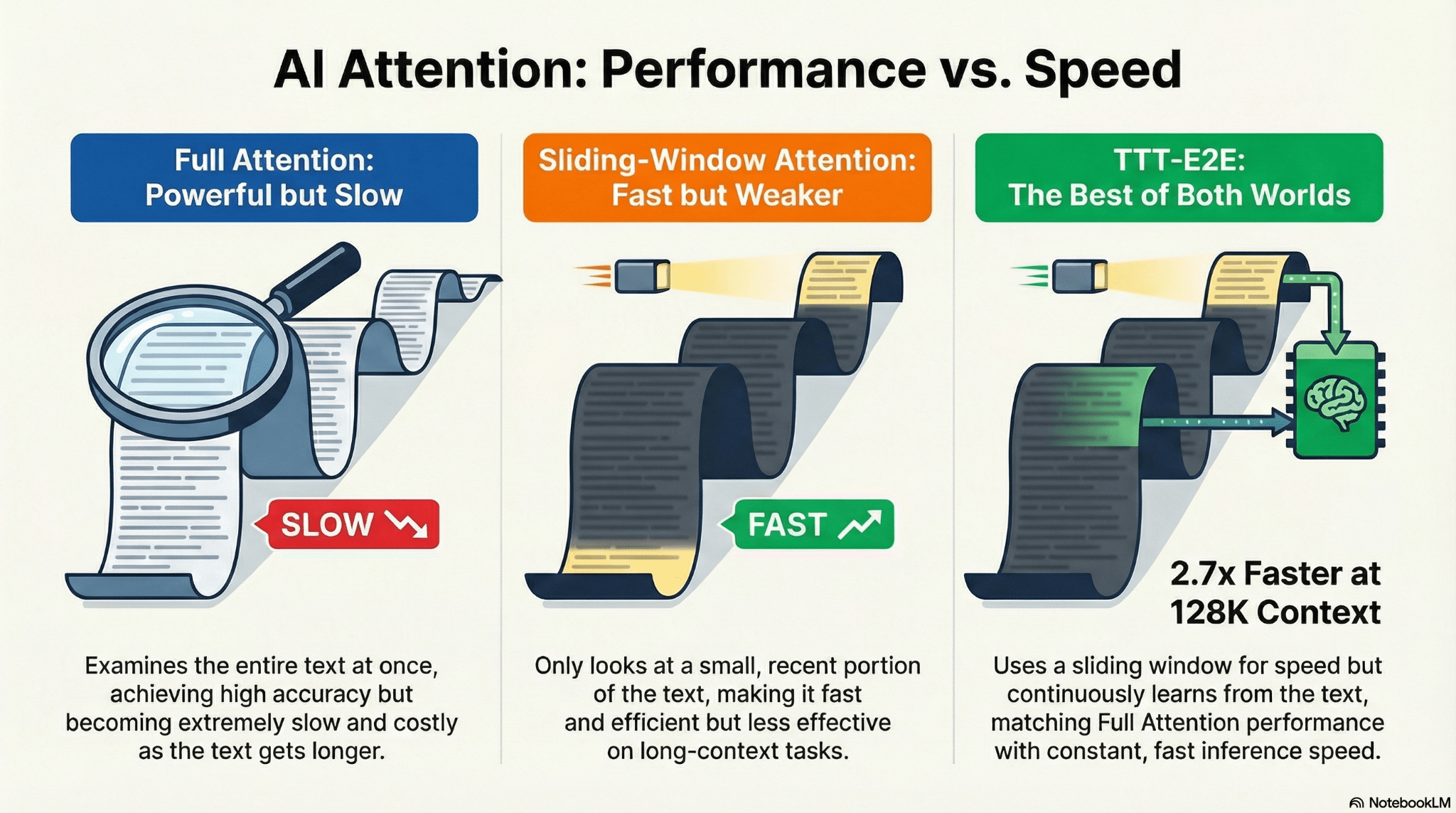

Inference-time techniques like chain-of-thought prompting or tree-search reasoning (which many modern reasoning models use) buy you more thinking time without changing the underlying weights. The model still works within its learned manifold. It's just given more steps to search that manifold for a solution.

For many tasks, more search time is enough. For true discovery, it's not.

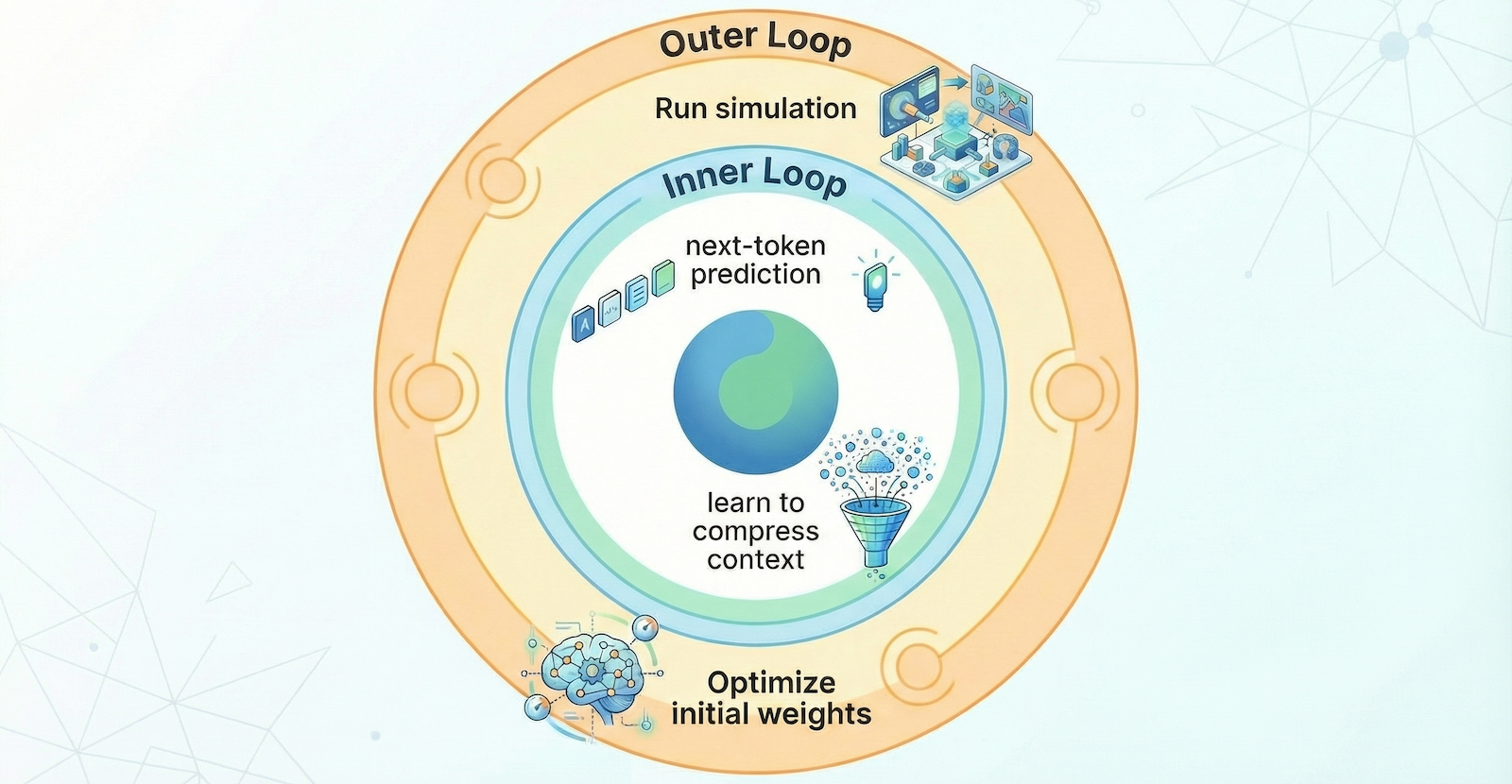

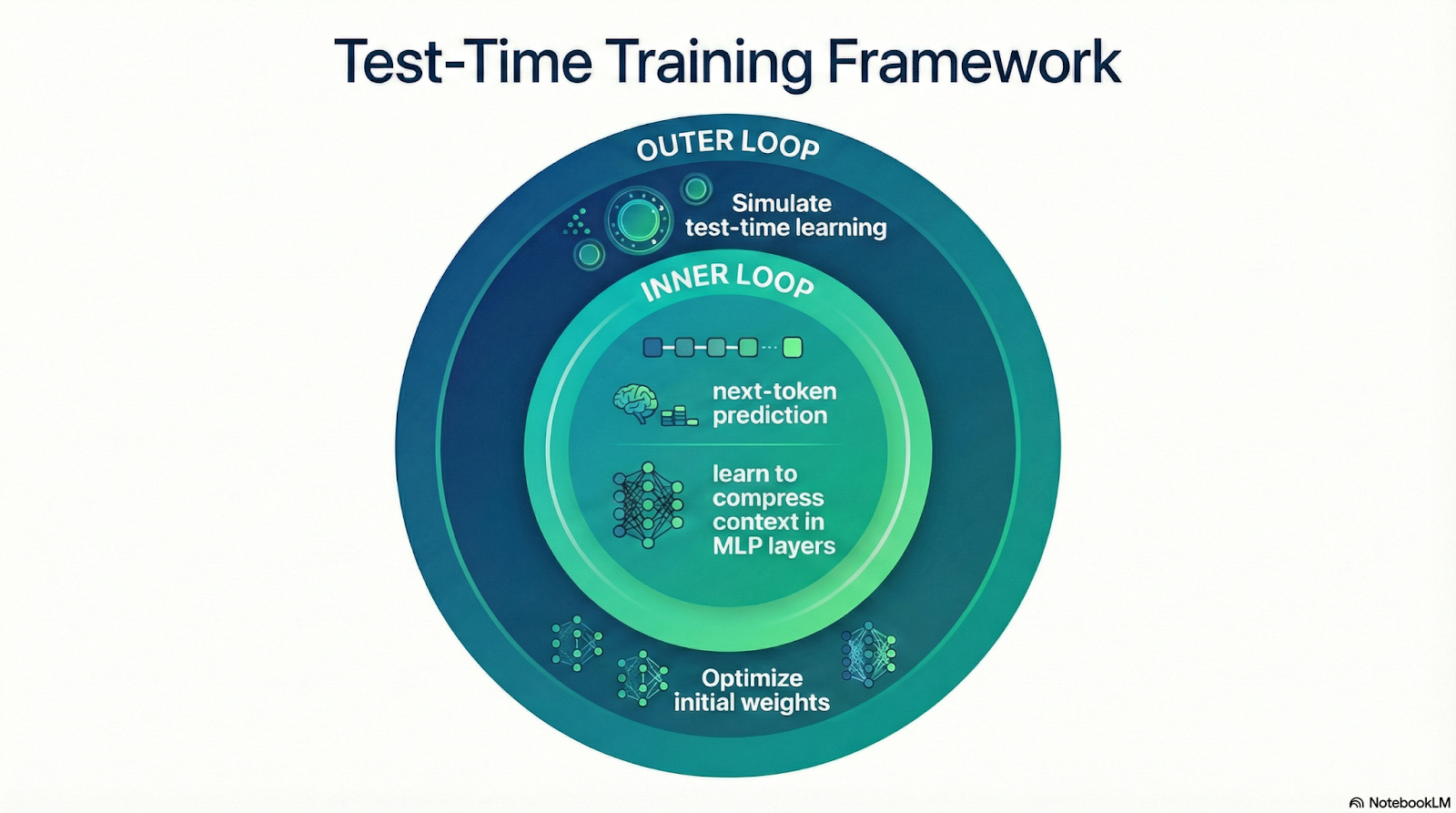

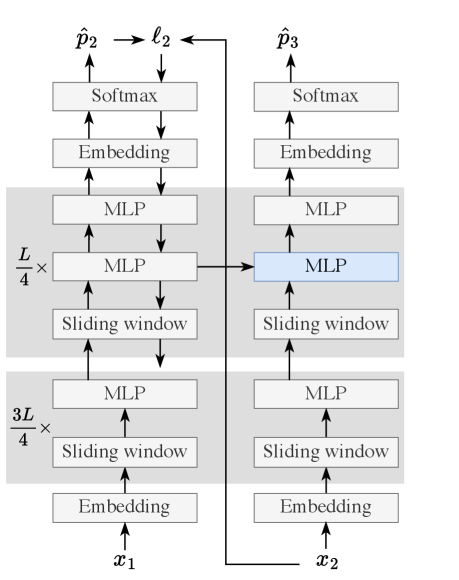

How Test-Time Training Actually Works

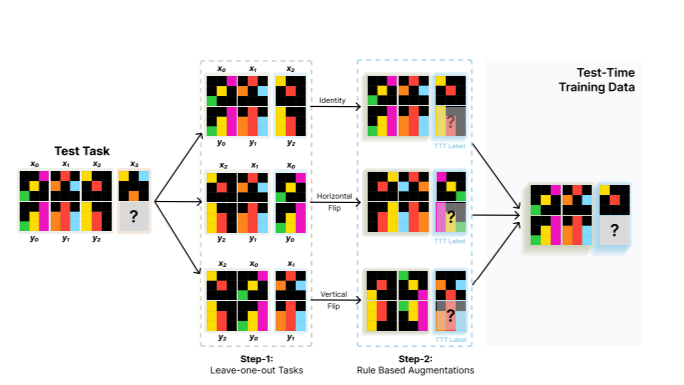

TTT-Discover treats the discovery problem completely differently. Instead of asking "what's the answer according to my training data," it asks "can I become a model that understands this specific problem?"

Here's the flow:

-

You present the model with a discovery challenge: optimize this GPU kernel, design this molecule, find a routing algorithm for this network.

-

The model generates candidate solutions. Some work better than others. Some fail spectacularly.

-

Instead of discarding the failures, TTT-Discover uses them as training data. Every rollout—every attempt, success, or failure—generates information about what leads where.

-

The model's weights update in real-time based on this information. It becomes increasingly specialized to this specific problem.

-

The search continues, guided by a model that's learning as it goes. After thousands of rollouts and dozens of training steps, you have a solution.

-

You extract the solution—the optimized kernel, the molecular structure, the algorithm. The model itself? You can discard it. Its job was to discover, not to remember.

This is radically different from standard reinforcement learning, where the goal is to create a generalist agent that performs well on average across many tasks. Here, the goal is singular: find the best solution to one specific problem.

The researchers implemented two key mechanisms to make this work:

Entropic Objective: Hunting for Outliers, Not Averages

In normal reinforcement learning, the reward function optimizes for expected value. If a risky move might give huge rewards but more often fails, standard RL penalizes it. The model learns to play it safe.

TTT-Discover flips this. It uses an entropic objective that exponentially weights high-reward outcomes. This forces the model to ignore safe, reliable-but-mediocre solutions and obsessively hunt for outliers. Those eureka moments. Solutions that have only a 1% chance of being found but offer 100x rewards.

In the context of GPU kernels, this means the model isn't satisfied with "a 10% faster kernel." It's relentlessly trying to find the 50% improvement, even if most attempts fail. This mindset shift is crucial for discovery.

PUCT Search: Building a Map of the Solution Space

The second mechanism is PUCT (Polynomial Upper Confidence Tree), a tree-search algorithm inspired by Alpha Zero, the system that beat the world's best Go player.

PUCT doesn't randomly generate solutions. It explores the solution space methodically, building a tree of attempts. High-reward branches get explored more. Low-reward branches get pruned. As the model trains on the data from these branches, it learns which partial steps—which partial solutions—lead toward high-reward outcomes.

This creates a feedback loop. Better trained model generates more promising candidates. Promising candidates reveal which techniques matter. The model learns from this, becoming even better at generation. The search converges toward the optimal solution space.

Crucially, this works best when you can measure progress continuously. Not "did we solve it or not" but "how much better is this solution than the last one." Microseconds gained. Error rates dropping. Molecular energy levels decreasing. Continuous signals let the model follow the gradient toward the optimum.

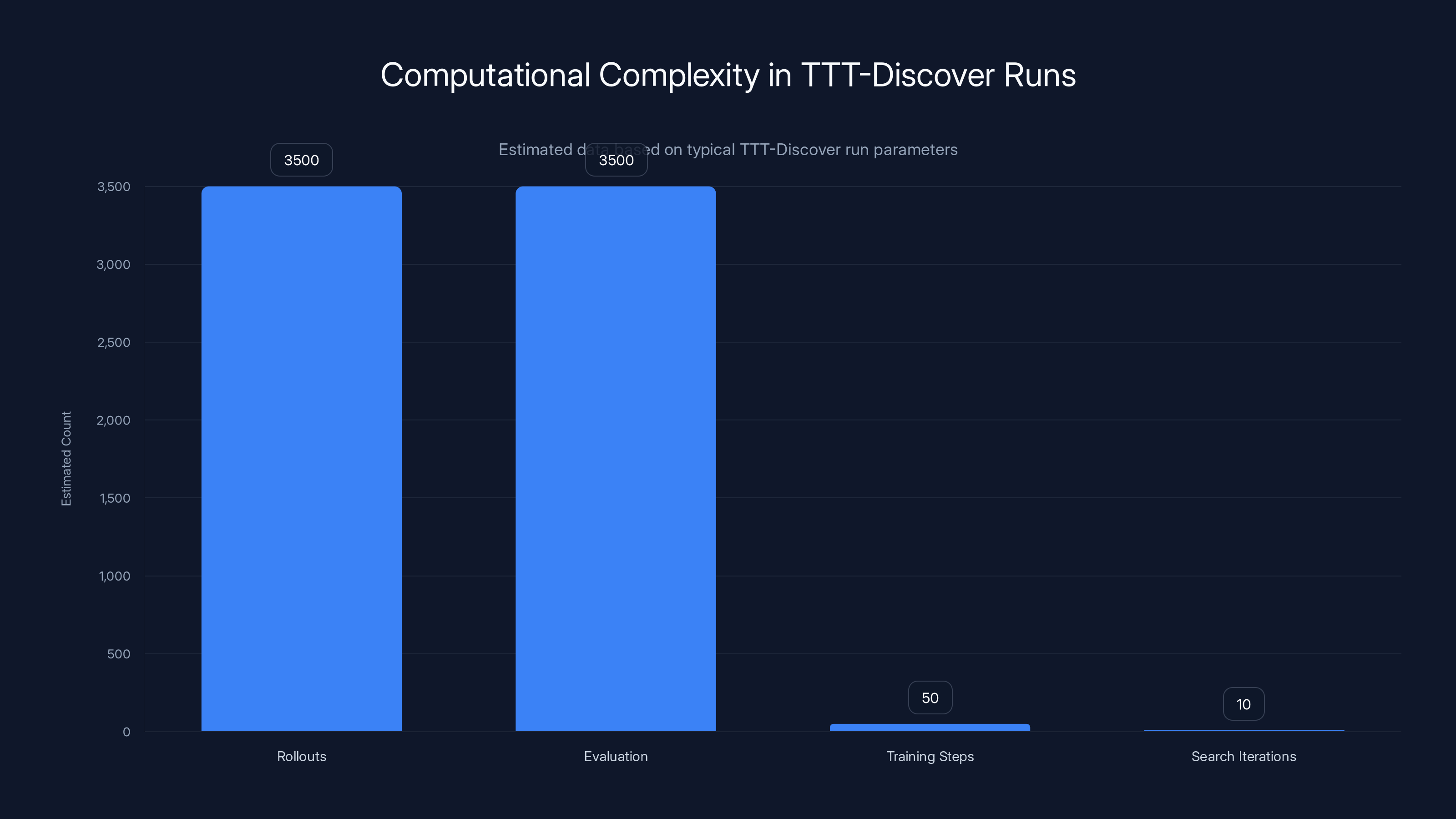

Estimated data shows that rollouts and evaluations are the most frequent operations in a TTT-Discover run, each occurring approximately 3,500 times. Training steps and search iterations are less frequent, with about 50 and 10 occurrences respectively.

The Technical Innovation: Why This Is Different

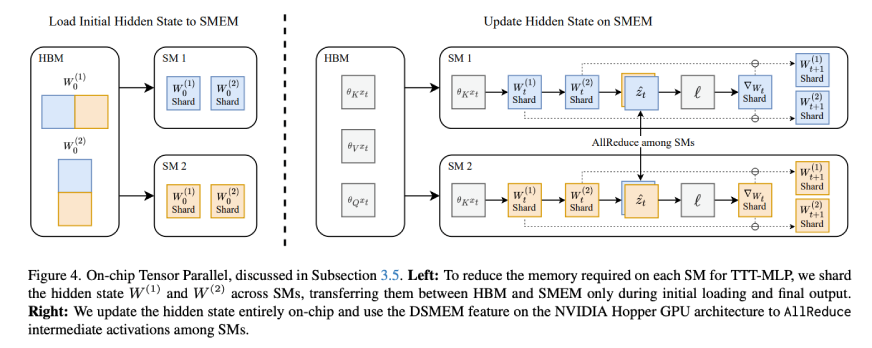

At its core, TTT-Discover isn't doing anything conceptually mysterious. It's combining test-time adaptation (updating weights at inference) with carefully designed reward functions and search algorithms.

But putting it together for discovery is the innovation.

Most previous work on test-time adaptation focused on domain adaptation: you have a model trained on Image Net, you get a new image distribution, you do a few gradient steps and adapt. Or you have a pretrained model that works on source domain tasks; you adapt it to target domain.

TTT-Discover applies test-time adaptation to something harder: not just adapting to a new distribution, but discovering solutions in a space that might not exist in the training distribution at all.

The other insight is the shift from generalist to specialist reasoning. Reasoning models today are built to be generalists: answer any question, solve any problem, explain anything. They're optimized for expected performance across diverse tasks.

TTT-Discover says: for a single hard problem, forget generality. Become a specialist. Optimize everything—every weight, every parameter—for finding the best solution to this one thing. Then throw the model away.

This is a profound conceptual shift. It means the artifact that matters isn't the model. It's the discovered solution.

The Economics: $500 Per Discovery

Here's the part that makes people stop and think: a single TTT-Discover run costs roughly $500.

For enterprises used to paying fractions of a cent per API call, this is a different mental model. You're not optimizing for cheap inference. You're optimizing for high-value discovery.

Let's do the math on when this makes sense:

Consider a cloud provider running a data pipeline that processes petabytes every night. The infrastructure costs are staggering: compute, storage, network transfer. A single GPU kernel that's even 1% faster might save $100,000 annually in electricity alone. At scale, that's not hyperbole—it's the reality of hyperscale computing.

Spending $500 to discover a kernel that's 50% faster? That pays for itself in minutes of runtime savings.

Or imagine a pharmaceutical company designing a new drug molecule. The difference between a molecule that binds poorly and one that binds perfectly could be billions in market value. A $500 discovery step that finds the better molecule is trivial expense.

Or supply chain optimization. A logistics network routing millions of packages daily. A 2% improvement in routing efficiency could save tens of millions annually. Again, $500 is nothing.

Yuksekgonul summarized it clearly: TTT-Discover makes sense for "low-frequency, high-impact decisions where a single improvement is worth far more than the compute cost."

Note the "low-frequency" part. This isn't something you run 1,000 times a day. It's something you run occasionally, when you have a truly hard problem that matters.

Cost Breakdown: What Actually Costs $500

The expense comes from the compute required during inference:

- Thousands of rollouts: The model generates many candidate solutions, trying different approaches

- ~50 training steps: The model updates its weights dozens of times during inference

- GPU resources: All of this runs on high-end GPUs (probably A100s or better)

- Inference time: Depending on problem complexity, this could take hours

The actual cost depends on your cloud provider's GPU pricing and the problem complexity. $500 is an estimate from the researchers' experiments, but harder problems would cost more.

Real-World Applications: Where TTT-Discover Matters Most

The GPU kernel optimization in the paper is just one example. The technique has much broader applications.

GPU Kernel and Code Optimization

This is the canonical use case. Kernels are the innermost loops in high-performance computing. A small optimization cascades. CUDA kernels for matrix multiplication, convolution operations, sparse tensor handling—these are written by human experts and still have room for improvement.

TTT-Discover can search the optimization space systematically, trying instruction sequences, memory access patterns, and algorithmic tweaks that humans might miss. The continuous reward signal is clear: runtime in microseconds.

The 2x speedup mentioned in the paper is real, and it's significant. In datacenter contexts, this kind of improvement is worth millions.

Drug Molecule Design

Designing a drug molecule means finding a chemical structure that:

- Binds to the target protein with high affinity

- Doesn't bind too strongly to off-targets

- Has acceptable toxicity profiles

- Is synthesizable

- Has reasonable patent landscape

This is an enormous search space. Humans (medicinal chemists) do this, but it takes months. A computational system that can explore this space quickly and learn as it goes could accelerate drug discovery significantly.

The reward signal could be binding affinity (measured continuously via docking simulations), synthesizability score, or predicted ADMET properties.

Material Science and Crystal Structure Discovery

Finding new materials with desired properties—higher conductivity, better thermal properties, improved strength-to-weight ratios—is another discovery problem. The search space is enormous (combinations of elements, crystal structures, dopants, etc.), and the reward signal is clear: measure the property you're optimizing for.

Supply Chain and Routing Optimization

Complex routing problems (vehicle routing, network optimization, supply chain scheduling) have massive solution spaces. A system that can run TTT-Discover on specific routing problems could discover significantly more efficient solutions than standard algorithms.

The reward signal is direct: total delivery time, fuel consumption, or cost.

Quantum Algorithm Design

Quantum computing is still in early stages. Designing quantum circuits and algorithms that run on near-term quantum hardware is a discovery problem. TTT-Discover could potentially help optimize quantum circuit structures and gate sequences.

Comparing TTT-Discover to Existing Approaches

Let's zoom out and compare TTT-Discover to how discovery problems are currently solved.

Traditional Human Expertise

A human expert—a GPU engineer, a medicinal chemist, a supply chain specialist—brings intuition, pattern recognition, and knowledge from years of experience. They can solve hard problems.

But they're limited by time. Solving a hard discovery problem might take months or years. And their solutions are bounded by what they know. A truly novel solution outside their experience domain is unlikely.

Human expertise is accurate but slow.

Standard Generalist AI Models

GPT-4, Claude, or other large language models can generate code, discuss molecular design, or suggest algorithms. They're fast and broad.

But they're confined to their training data. A truly novel solution—one requiring logical leaps not present in training—is unlikely. And you can't verify or refine based on actual outcomes; you're just generating text.

Generalist AI is fast but shallow.

Specialized Algorithms and Heuristics

For some discovery problems, we have domain-specific algorithms: genetic algorithms for optimization, Monte Carlo tree search for planning, molecular dynamics simulations for drug discovery.

These work, but they're narrow. They don't learn or adapt. They're fixed procedures.

Specialized algorithms are reliable but inflexible.

Test-Time Training to Discover

TTT-Discover combines advantages: it learns continuously (like humans), it's algorithmic and measurable (like specialized algorithms), and it can discover solutions outside the training distribution (unlike frozen models).

The tradeoff is cost and time per problem. It's not cheap or fast per run, but the quality of discovery is high.

TTT-Discover achieves a 2x speedup over human experts in optimizing GPU kernels by systematically exploring and learning in real-time.

The Continuous Reward Signal Requirement: A Critical Limitation

Here's the catch that doesn't get as much attention: TTT-Discover needs a continuous reward signal.

You can't use it on problems where you only know "right" or "wrong," "pass" or "fail." You need to measure incremental progress.

GPU kernel optimization: easy. You measure runtime. Mathematical theorem proving: hard. You either prove it or you don't. There's no "partially proven" state.

Molecular docking: easy. You measure binding affinity on a continuous scale. Constraint satisfaction problems: harder. You either satisfy the constraints or you don't.

This is a significant constraint. Many interesting discovery problems don't have obvious continuous reward signals. And instrumenting a reward signal where none naturally exists is non-trivial.

Yuksekgonul acknowledged this limitation in interviews. For domains where you only have binary feedback, you'd need a different approach. Perhaps auxiliary reward signals (like predicting intermediate success probability) or different algorithmic techniques.

Computational Complexity: The Numbers Behind the Discovery

Let's break down what happens during a TTT-Discover run:

Rollouts: The system might generate 2,000 to 5,000 different candidate solutions. For GPU kernel optimization, that means generating 2,000 to 5,000 different sequences of GPU instructions and measuring their runtime.

Evaluation: Each rollout needs to be evaluated. For a kernel, this means compiling it (if needed) and running it to measure performance. For a molecule, this means a docking simulation. This is the compute-intensive part.

Training steps: The model updates its weights based on what it's learned. With reinforcement learning, you typically do 50 updates or so. Each update involves a forward pass, loss computation, and backpropagation.

Search iterations: These happen in cycles. Generate rollouts, evaluate, train, repeat.

The total compute adds up. On a high-end GPU, a few hours of sustained inference and training. At current cloud GPU pricing (roughly

As cloud pricing drops and GPUs get more efficient, the cost per discovery run will fall. But the relative cost advantage will remain: this is expensive for a single run but cheap relative to the value of the discovered solution.

The Model Architecture: What Kind of Models Work for TTT-Discover

Interestingly, the researchers didn't need enormous models for TTT-Discover.

You might expect they'd use GPT-4 scale models. But no. In their experiments, they used relatively modest models because the adaptation happens during inference, not during pre-training.

A model that has broad knowledge of the domain (e.g., code models for kernel optimization) is useful as a starting point. But the heavy lifting—specialization to the specific problem—happens during the test-time training phase.

This is good news for practical deployment. You don't need cutting-edge frontier models. A solid domain-specific base model is often enough.

For code generation, something like Codex or similar GPT-based code models work well. For molecular design, a transformer trained on molecular SMILES strings and properties is useful. For supply chain optimization, a model trained on logistics domains helps.

But the exact architecture isn't as critical as the continuous reward signal and the search procedure.

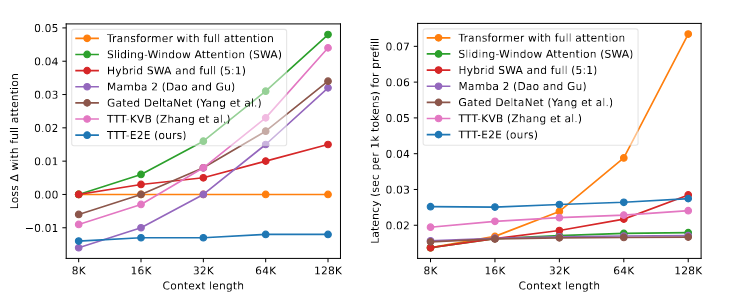

Comparison With Other Inference-Time Approaches

There are other ways to improve inference-time reasoning:

Chain-of-thought prompting: Ask the model to think step-by-step. This helps, but the model is still working within its frozen weights.

Tree-of-thought: Explore multiple reasoning paths. Better than chain-of-thought but still bounded by the original model.

Mixture-of-experts at inference: Route problems to specialized sub-models. Helps with coverage but doesn't adapt the models themselves.

Retrieval-augmented generation: Fetch relevant data from a database during inference. Gives the model more information but doesn't update its understanding.

Test-time training (TTT-Discover): Actually update the model's weights based on the problem and immediate feedback.

The key difference is the weight update. All other approaches are exploiting existing knowledge better. TTT-Discover is literally learning during inference, becoming a different model as it goes.

This is more powerful but also more expensive and slower.

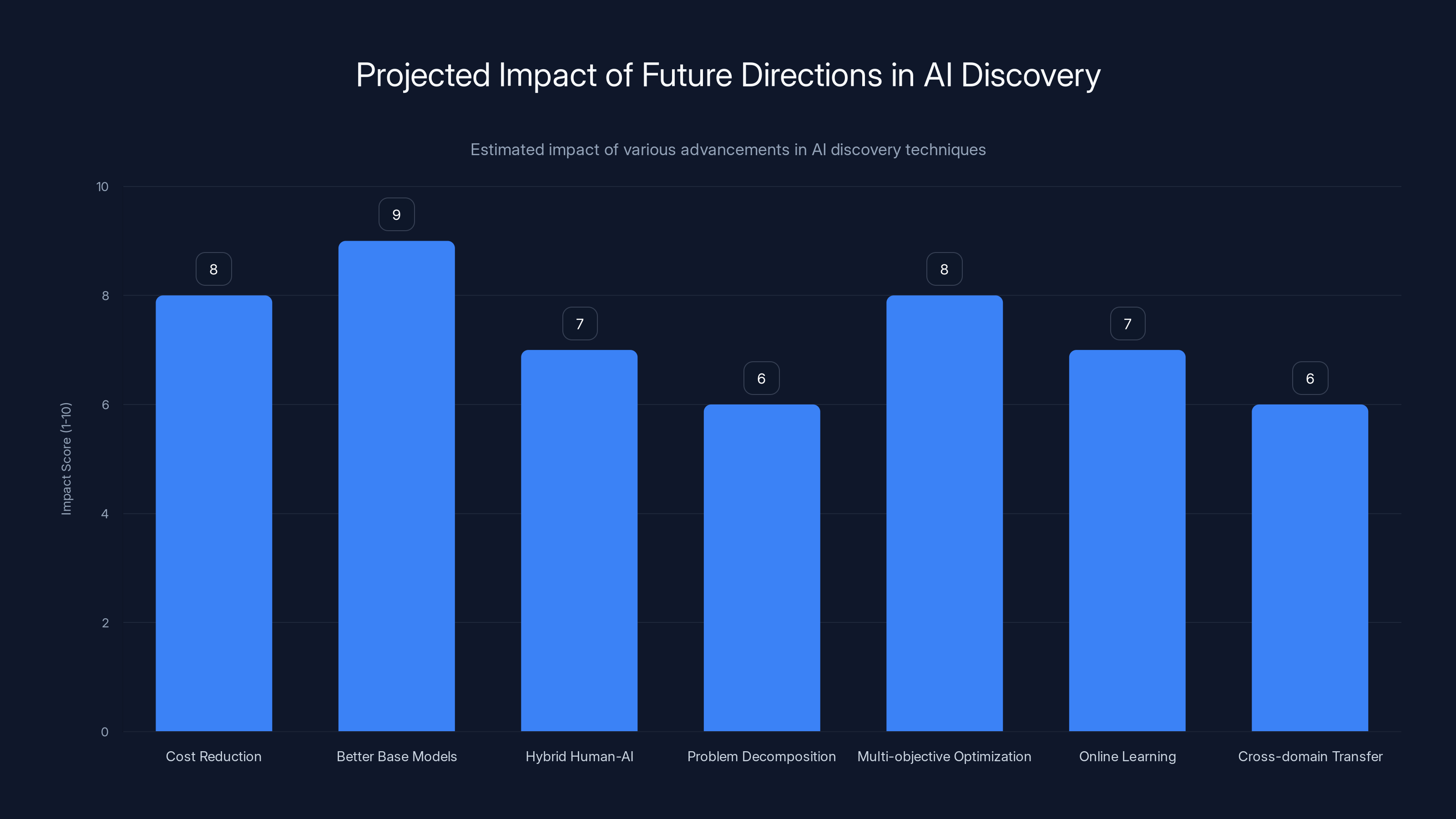

Estimated data suggests that better base models and cost reduction will have the highest impact on the future of AI discovery, making it more accessible and efficient.

Practical Implementation: How You'd Actually Use This

Let's talk about actually running TTT-Discover:

Step 1: Problem Formulation

First, you define your discovery problem clearly. Not vague like "find a better algorithm." Specific: "optimize this GPU kernel to minimize memory bandwidth usage while maintaining correctness."

You need:

- A clear objective (the reward signal)

- A way to measure success

- Constraints (if any)

- A base model that understands your domain

Step 2: Reward Function Design

You implement the reward signal. For a GPU kernel, it's straightforward: measure runtime. For a molecule, it's docking affinity or predicted properties.

This is often the hardest part. If your problem doesn't have a natural continuous reward signal, you might need to instrument one.

Step 3: Infrastructure Setup

You provision GPU compute. Probably A100s or better, depending on problem complexity. You set up the evaluation pipeline: how does your system test candidate solutions?

For kernels, this is a compilation and execution harness. For molecules, this is a docking engine.

Step 4: Run the Discovery Process

You start the TTT-Discover process. The model generates candidates, you evaluate them, the model learns from the results, and the cycle repeats.

Depending on problem complexity, this might take 2 to 8 hours. You monitor progress and can stop early if you're satisfied with the solution found.

Step 5: Extract and Validate

You extract the discovered artifact: the optimized kernel, the molecular structure, the algorithm. You validate it independently, make sure it's correct, and integrate it into your system.

Step 6: (Optional) Iterate

If you're not happy with the result, you might try again with different starting models or reward functions. Each run is independent.

Limitations and Open Questions

TTT-Discover is exciting, but it's not magic. Several limitations exist:

The Continuous Reward Signal Requirement

Again: you need a continuous signal. Problems with only binary outcomes are hard. This rules out many interesting discovery challenges.

Model Size and Inference Cost

Smaller models work for TTT-Discover, but there's probably a minimum size. And inference-time training is expensive. This isn't something you run 1,000 times a day.

Generalization of Discovered Solutions

A GPU kernel optimized for one architecture might not be optimal for another. A molecule designed for one target might have issues with off-targets not included in the reward signal. The discovered solutions are specialized to the specific problem.

Verification and Safety

When you discover something new, how do you verify it? For kernels, you can test correctness. For molecules, you run additional simulations. For algorithms, you verify the logic. But there's no guarantee the discovered solution is safe or robust.

Cold Start Problem

If you have a truly novel problem domain where your base model has limited knowledge, cold start is harder. You need enough domain understanding to get started.

Comparison to Human Experts

The 2x speedup over human experts is impressive, but humans aren't being run through the same process. A human expert given similar compute time and resources might also improve. The fair comparison is harder to make.

Future Directions: Where This Heads

Assuming the technique continues to develop, several directions seem likely:

Cost reduction: As GPUs get cheaper and software optimizes, the

Better base models: Domain-specific models will improve. A code model trained on 1 trillion tokens of kernel code will beat today's general code models.

Hybrid human-AI discovery: Instead of humans or AI separately, humans and TTT-Discover working together. The human provides intuition and constraints; TTT-Discover searches the space. This could be powerful.

Problem decomposition: For huge discovery problems, learning to break them into sub-problems that each have continuous reward signals.

Multi-objective optimization: Instead of a single reward, handle trade-offs (speed vs. memory, effectiveness vs. side effects, performance vs. cost).

Online learning: Instead of one-off discovery runs, continuous learning systems that improve solutions over time as they run in production.

Cross-domain transfer: Training on discovery problems in one domain (drug molecules) to get better at discovery in another (materials science).

Comparison to Alternatives at a Glance

| Approach | Speed | Quality | Cost | Generality | Continuous Learning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Expertise | Slow | High | High (time) | Broad | Yes (slow) |

| Frozen LLMs | Fast | Medium | Low | Broad | No |

| TTT-Discover | Medium | Very High | Medium-High | Domain-specific | Yes (inference time) |

| Specialized Algorithms | Fast | Medium-High | Low | Narrow | No |

| Evolutionary Algorithms | Medium-Slow | Medium | Low | Narrow | Yes |

TTT-Discover can potentially double performance in GPU kernel optimization and significantly enhance drug design, material science, and supply chain management. Estimated data.

The Paradigm Shift: From Static to Adaptive Models

Zoom out for a moment. What TTT-Discover represents is a philosophical shift in how we think about AI models.

Today's paradigm: train once, deploy forever. The model is an artifact. You make it as good as possible before deployment, then you're stuck with it.

TTT-Discover suggests a different paradigm: deploy a competent base model, but let it adapt during use on hard problems. The model is flexible, not frozen.

This has implications beyond discovery:

- Personalization: Instead of one model for all users, the model could adapt to individual user preferences during a session.

- Domain shift: Instead of retraining when you shift to a new data distribution, the model adapts in real-time.

- Adversarial robustness: Instead of being vulnerable to adversarial examples, the model could adapt when it encounters them.

- Continual learning: Instead of catastrophic forgetting when learning new tasks, adaptive models could integrate new knowledge.

Not all of these are straightforward extensions. But TTT-Discover cracks open the door to a way of thinking about models that's been mostly closed for the last decade.

Maybe the future of AI isn't about bigger, more static models. Maybe it's about models that stay curious, that keep learning, that adapt to the world as they encounter it.

Real-World Deployment Challenges

Moving from research to production introduces practical challenges:

Reproducibility

GPU kernels and molecular simulations can have subtle non-determinism. Reproducing the exact discovered solution might be difficult. Documentation and version tracking become critical.

Integration

Once you've discovered a solution, integrating it into your system might require refactoring. A kernel discovered in isolation might need careful integration with surrounding code.

Validation and Testing

You need robust testing pipelines. For kernels, property-based testing and fuzzing. For molecules, in-vitro validation. Discovered solutions aren't magic; they're hypotheses that need verification.

Regulatory and Compliance

In regulated domains (pharma, aviation), a discovered solution needs to prove it follows the same validation processes as hand-engineered solutions. That's an overhead.

Maintenance

When your GPU architecture updates, does your discovered kernel still work? When your molecular target changes slightly, is your molecule still optimal? Maintenance is an ongoing consideration.

Business and Economic Implications

The economics of TTT-Discover are interesting:

For cloud providers: If they can discover kernels 2x faster, the cost per unit compute drops. Passed to customers, this is massive competitive advantage.

For pharmaceutical companies: Drug discovery is already expensive (~$2 billion per approved drug). If TTT-Discover can shorten discovery timelines, the value is enormous.

For materials science and battery makers: Discovery of new materials is rate-limiting. If TTT-Discover accelerates it, companies with access gain advantage.

For logistics and supply chain: A 2-5% efficiency gain at scale is worth tens of millions. Easy payoff for occasional $500 discovery runs.

For startups: Access to this technology might level the playing field against incumbents who have armies of domain experts. A startup with TTT-Discover and good problem formulation might outpace experts.

The companies that developed this—Stanford (research), Nvidia (inference infrastructure), and Together AI (inference platform)—are well-positioned if this takes off.

How TTT-Discover Relates to AI Safety and Alignment

Here's a less-discussed angle: test-time training has implications for AI safety.

Today's AI safety work focuses on training-time alignment: building models that pursue the goals we intend during training. But alignment is harder during deployment because you can't control the user's prompts.

TTT-Discover suggests a model that adapts to the specific problem at hand. This could be good or bad for alignment.

Good: if you define a robust reward signal that captures your true objectives, the model will adapt toward that. You could, in theory, have an adaptive model that becomes better at recognizing and avoiding misuse.

Bad: if the reward signal is poorly specified or has a bug, the model might discover solutions that game the metric in unintended ways. This is the classic specification gaming problem, now at inference time.

Neither camp is clearly winning this debate yet. But it's worth noting that adaptive models introduce new considerations for AI safety work.

TTT-Discover is projected to have significant impacts across multiple industries, particularly in pharmaceuticals and cloud computing. (Estimated data)

The Importance of Specific Reward Signals

This deserves its own section because it's critical: the quality of your reward signal determines the quality of your discovered solution.

Suppose you're optimizing a GPU kernel and your reward is "runtime in microseconds." Straightforward. But what if the kernel has a subtle bug for rare edge cases? You might discover a fast kernel that's wrong.

You'd need to add "correctness under all test cases" to your reward signal. But how do you measure that continuously?

Or suppose you're designing a drug molecule. Your reward is "binding affinity to the target." You discover a molecule that binds strongly. But it also causes toxicity in liver cells (off-target binding to a cytochrome P450). That's not captured in your reward signal.

You'd need to include predicted off-target binding in your reward. But that makes the reward more complex, potentially slower to compute.

This is the reward specification problem in miniature. It's always been hard in reinforcement learning. TTT-Discover doesn't solve it; it just brings it into sharp focus.

Good reward signal design requires domain expertise. A medicinal chemist knows what trade-offs matter in molecular design. An infrastructure engineer knows what matters for GPU kernels. That expertise is still needed; TTT-Discover doesn't replace it.

Comparison to Auto ML and Neural Architecture Search

You might be thinking: isn't this just automated machine learning or neural architecture search (NAS) taken to the extreme?

Partially, yes. NAS searches for optimal neural architectures. Some NAS systems use similar techniques: generation, evaluation, learning.

The key differences:

NAS scope: NAS usually searches over network architectures (layers, connections, hyperparameters). TTT-Discover searches the solution space of the actual problem (kernel code, molecular structures, algorithms).

Reward signals: NAS typically optimizes for accuracy on a validation set. TTT-Discover optimizes for domain-specific metrics (runtime, binding affinity, etc.).

Output: NAS produces a neural network. TTT-Discover produces domain artifacts (kernel code, molecules) that might not involve neural networks at all.

Adaptation: NAS happens once to find a good architecture. TTT-Discover adapts a model in real-time during inference to solve a specific problem.

So there's overlap in techniques, but the purpose and scope are quite different.

Implications for Software Engineering

Imagine a future where developers use TTT-Discover as part of their workflow:

- You write a program, and profiling shows a bottleneck in a specific function.

- You describe the problem to TTT-Discover: "optimize this sorting function for 64-bit integers on modern CPUs."

- In a few hours, you get back optimized code that's 2-3x faster.

- You integrate it, test it, ship it.

This could transform optimization from a skill requiring years of expertise into something accessible. You don't need to understand CPU cache hierarchies and branch prediction; TTT-Discover does the discovering.

Downside: you still need to understand the problem well enough to specify it correctly. Bad specifications lead to bad discoveries.

Also, relying on TTT-Discover for optimization might create a skill gap. Future engineers might not develop the deep understanding of optimization that previous generations had.

Historical Context: Learning Systems Throughout AI History

TTT-Discover isn't entirely new; it stands on decades of work:

Evolutionary algorithms (1960s-present): Population-based search with selection pressure. Similar spirit but different mechanism.

Reinforcement learning (1980s-present): Learning from interaction and reward. Core technique TTT-Discover uses.

Meta-learning (2000s-present): Learning to learn. TTT-Discover is a form of test-time meta-learning.

Neural Architecture Search (2016-present): Automated architecture discovery. Similar problem-solving approach.

Alpha Zero (2017): Self-play learning producing superhuman game-playing. Similar principle: learn through interaction.

In-context learning (2020s): Models adapting to tasks based on prompts. Related to test-time adaptation.

TTT-Discover combines insights from all of these, applied to discovery problems with continuous reward signals.

Scalability Questions: What Happens as Problems Get Harder

The GPU kernel problem in the paper is complex but still relatively bounded. What happens as you tackle even harder problems?

Suppose you want to discover a new class of materials with properties we haven't seen before. The search space is astronomical. Does TTT-Discover scale?

Likely, scalability becomes harder. The search space might grow exponentially. You might need more rollouts, more training steps, more compute.

The researchers acknowledge this: TTT-Discover worked well for the kernel problem. Other problems might require architectural changes or different approaches.

It's worth noting that human discovery also scales imperfectly with problem difficulty. Scientists spend more time on harder problems. TTT-Discover would too.

The Role of Domain Knowledge

Here's something that shouldn't be overlooked: TTT-Discover still needs significant domain knowledge.

You need to:

- Formulate the problem correctly

- Design the reward signal

- Build the evaluation pipeline

- Choose or train a base model with domain understanding

- Validate the discovered solution

All of these require expertise. TTT-Discover isn't a replacement for understanding your domain. It's a tool that amplifies existing expertise.

In some ways, this makes it harder to use than simply asking a human expert or running a standard algorithm. You need to think deeply about your problem to set it up correctly.

But the payoff, if done well, is discovering solutions that humans or standard algorithms would miss.

Ethical Considerations

Any powerful discovery tool raises ethical questions:

Dual-use: Could TTT-Discover discover harmful things? A drug molecule designed for treatment could be modified for harm. An optimized algorithm could be weaponized. The researchers can't control the downstream use.

Access and inequality: TTT-Discover is expensive ($500 per run). Only well-funded organizations can use it. This could increase inequality between those who can afford discovery and those who can't.

Environmental cost: Thousands of GPU hours per discovery run have environmental implications. As the technique becomes popular, the cumulative impact could be significant.

Labor displacement: If TTT-Discover makes optimization expertise less valuable, what happens to the engineers who specialize in it? This is a broader automation question but worth noting.

The researchers haven't published ethics discussion as far as I know. It would be valuable for the community to think through these implications.

Key Takeaways for Practitioners

If you're thinking about whether TTT-Discover is relevant to your work:

- Your problem needs a continuous reward signal: Binary pass/fail is hard. Can you measure progress?

- The problem needs to be high-value: $500 per discovery only makes sense if the improvement is worth much more.

- You need domain expertise to set it up: You can't just throw a vague problem at it. Precise formulation is critical.

- The solution needs validation: Discovered solutions aren't magic. You need to verify they actually work.

- It's not general-purpose: This is for specific, hard discovery problems. Don't use it for routine tasks.

If those criteria fit, TTT-Discover could be genuinely transformative for your work.

The Broader Implications for AI Research

Beyond the specific application, TTT-Discover suggests some broader lessons for AI research:

-

Specialized models beat generalists for hard problems: A model that's fine-tuned to one problem via test-time training beats a jack-of-all-trades model.

-

Inference-time adaptation is powerful: We've been locked into the training-deployment paradigm for years. Maybe it's time to reconsider.

-

Good reward signals matter more than model size: You don't need GPT-4 scale for TTT-Discover; you need the right reward function.

-

Search and learning are complementary: Combining exploration (PUCT search) with exploitation (model training) produces better results than either alone.

-

Discovery and reasoning are different problems: Reasoning within known knowledge is different from discovering new knowledge. Maybe they need different architectures.

Looking Forward: The Next 2-3 Years

What's likely to happen:

2024-2025: Incremental improvements. Better base models, more efficient reward functions, cost reductions. Papers applying TTT-Discover to more domains (materials, molecules, robotics).

2025-2026: Commercialization. Cloud providers might offer TTT-Discover as a service. Startups might build domain-specific versions for pharmaceuticals, materials science, etc.

2026+: Integration into standard development workflows. Like how gradient descent became ubiquitous, TTT-Discover might become a tool every researcher and engineer knows about.

Or it could plateau. New techniques might emerge that are cheaper or more general. The history of AI is full of approaches that seemed revolutionary until better ones came along.

FAQ

What is Test-Time Training to Discover (TTT-Discover)?

TTT-Discover is a technique that allows AI models to update their weights during inference (the actual problem-solving phase) rather than remaining static. Unlike traditional models that are frozen after training, TTT-Discover enables models to continuously adapt and specialize to a specific problem at hand, using real-time feedback and a search algorithm to explore the solution space and find novel, high-quality solutions. The discovered solution (like an optimized GPU kernel) can then be extracted while the adapted model is discarded.

How does TTT-Discover differ from standard reinforcement learning?

Standard reinforcement learning trains a generalist agent that performs well on average across many different tasks and continues using that same model. TTT-Discover flips this paradigm: instead of creating a general-purpose model, it focuses entirely on discovering the best possible solution to a single, specific problem. The model is specialized during inference using an entropic objective (which hunts for exceptional solutions rather than average ones) and PUCT search algorithm, then discarded once the solution is found. This allows TTT-Discover to discover solutions that would be out-of-distribution for frozen models.

What makes TTT-Discover achieve a 2x improvement over human experts on GPU kernels?

The 2x speedup comes from systematic exploration guided by a model that learns in real-time. Human experts, while knowledgeable, work within the bounds of their training and intuition, which might miss certain optimization combinations. TTT-Discover generates thousands of candidate kernel implementations (rollouts), evaluates each one by measuring actual runtime, and updates its internal understanding based on which approaches lead to faster kernels. This systematic search, combined with continuous learning, discovers kernel optimizations that human experts with static knowledge had not found.

What are the costs and economics of using TTT-Discover?

A single TTT-Discover discovery run costs approximately

What types of problems can TTT-Discover solve?

TTT-Discover works best on discovery problems that have a clear, continuous reward signal measuring progress. Ideal applications include GPU kernel optimization (measuring runtime in microseconds), drug molecule design (measuring binding affinity), material science (measuring desired properties like conductivity or strength), supply chain routing (measuring delivery time or cost), and quantum algorithm design (measuring circuit efficiency). Problems with only binary pass/fail outcomes are difficult because the system needs incremental feedback to guide its search.

Why is a continuous reward signal so important for TTT-Discover?

A continuous reward signal allows the model to follow a gradient of improvement toward optimal solutions. Instead of knowing only "this kernel works" or "this kernel fails," a continuous signal reveals "this kernel runs in 1.2 microseconds while the previous one ran in 1.5 microseconds." This incremental feedback drives the search algorithm (PUCT) to explore more promising branches and guides the model's weight updates toward refining approaches that show improvement. Without continuous feedback, the system would essentially be guessing whether candidate solutions are moving toward or away from optimality.

What base model should I use for TTT-Discover?

You don't need extremely large models for TTT-Discover because the specialization happens during inference-time training. Domain-specific models of modest size (like a code transformer trained on GPU kernel implementations, or a molecular chemistry model trained on chemical structures) work well. The base model needs enough domain understanding to generate reasonable candidate solutions initially, but the specialization and discovery happen through the test-time training process. Choosing a competent domain-specific base model is more important than choosing the largest general-purpose model.

How does TTT-Discover compare to evolutionary algorithms and genetic algorithms?

Both TTT-Discover and evolutionary algorithms use search and selection to find good solutions. However, TTT-Discover combines search (PUCT tree exploration) with neural network learning (updating model weights based on observed results). Evolutionary algorithms typically apply fixed transformation rules and selection pressure but don't learn internally. TTT-Discover's advantage is that the model becomes smarter about generating and evaluating candidates as it learns, while evolutionary algorithms repeat the same search process throughout. The tradeoff is that TTT-Discover requires more compute per iteration but potentially finds better solutions faster.

Can TTT-Discover guarantee optimal solutions?

No, TTT-Discover doesn't guarantee finding the globally optimal solution. It's a heuristic search method that explores the solution space intelligently through iteration and learning, but like any search algorithm, it could miss better solutions that exist in unexplored regions of the search space. The 2x improvement over human experts doesn't mean the discovered kernel is twice as fast as physically possible, only that it's twice as fast as what human experts previously found. With more compute (more rollouts, more training steps), TTT-Discover might find even better solutions, but there's no point at which you know you've found the absolute best possible solution.

What happens if my reward signal is poorly designed or misses important factors?

If your reward signal doesn't capture all the factors that actually matter, TTT-Discover will optimize for what you measured while potentially degrading unmeasured attributes. For example, if you optimize GPU kernels purely for runtime without considering memory bandwidth or cache efficiency, you might discover a kernel that's fast on one hardware configuration but slow on others. This is the "reward specification problem" and is one of the trickiest aspects of using TTT-Discover. Domain expertise is critical for designing reward signals that truly reflect what you care about. Thorough validation of discovered solutions is essential to catch unintended consequences.

How long does a TTT-Discover run typically take?

A typical TTT-Discover discovery run takes 2 to 8 hours on high-end GPUs like NVIDIA A100s, depending on problem complexity and the number of rollouts and training steps. The time includes generating thousands of candidate solutions, evaluating each one (which can be the bottleneck if evaluation is expensive), updating the model weights through multiple training steps, and repeating these cycles. Problems with expensive evaluation (like molecular docking simulations or complex kernel compilation) take longer than problems with cheap evaluation.

Conclusion: The Opening of a Door

Test-Time Training to Discover represents something meaningful: a crack in the wall of static, frozen models. For over a decade, the paradigm has been to train once and deploy forever. Adapt through prompting, reasoning longer, or better search, but don't change the model.

TTT-Discover says that for hard discovery problems, maybe that's not the optimal approach. Maybe letting the model adapt during inference, becoming a specialist for a specific problem, yields better results.

The $500 cost per discovery run might seem high, but in context, it's trivial. A pharmaceutical company spending that to discover a better drug molecule is a rounding error on their budget. A cloud provider spending that to discover a kernel that saves millions in annual compute costs is making a spectacularly good investment.

Where this goes depends on several things: how quickly costs drop as the software and hardware mature, whether the technique extends to harder problems, whether domain-specific versions emerge, and whether organizations internalize that discovery is sometimes worth expensive inference.

If those conditions are met, we might look back at this moment as the point where AI shifted from pure generalization toward targeted discovery. Not replacing human expertise, but amplifying it. Letting humans focus on problem formulation while AI handles the hard work of exploration and optimization.

That's not a small shift. It's a different way of thinking about what AI can be.

For now, TTT-Discover is a research result with powerful implications. It shows that test-time training works, that continuous learning during inference produces better discoveries, and that the right problem formulation matters more than model size.

The next few years will tell us whether it scales beyond GPU kernels, whether costs fall enough for broader adoption, and whether this paradigm becomes standard or remains a specialized tool.

But the door has opened. That's worth paying attention to.

Related Articles

- Predictive Inverse Dynamics Models: Smarter Imitation Learning [2025]

- Arcee's Trinity Large: Open-Source AI Model Revolution [2025]

- How AI Models Use Internal Debate to Achieve 73% Better Accuracy [2025]

- Uber's AV Labs: How Data Collection Shapes Autonomous Vehicles [2025]

- AI Chip Startups Hit $4B Valuations: Inside the Hardware Revolution [2025]

- Gemini-Powered Siri: What Apple Intelligence Really Needs [2025]

![Test-Time Training Discover: How AI Optimizes GPU Kernels 2x Faster [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/test-time-training-discover-how-ai-optimizes-gpu-kernels-2x-/image-1-1770331210650.jpg)