The Under Armour Data Breach: A Timeline and Impact Analysis

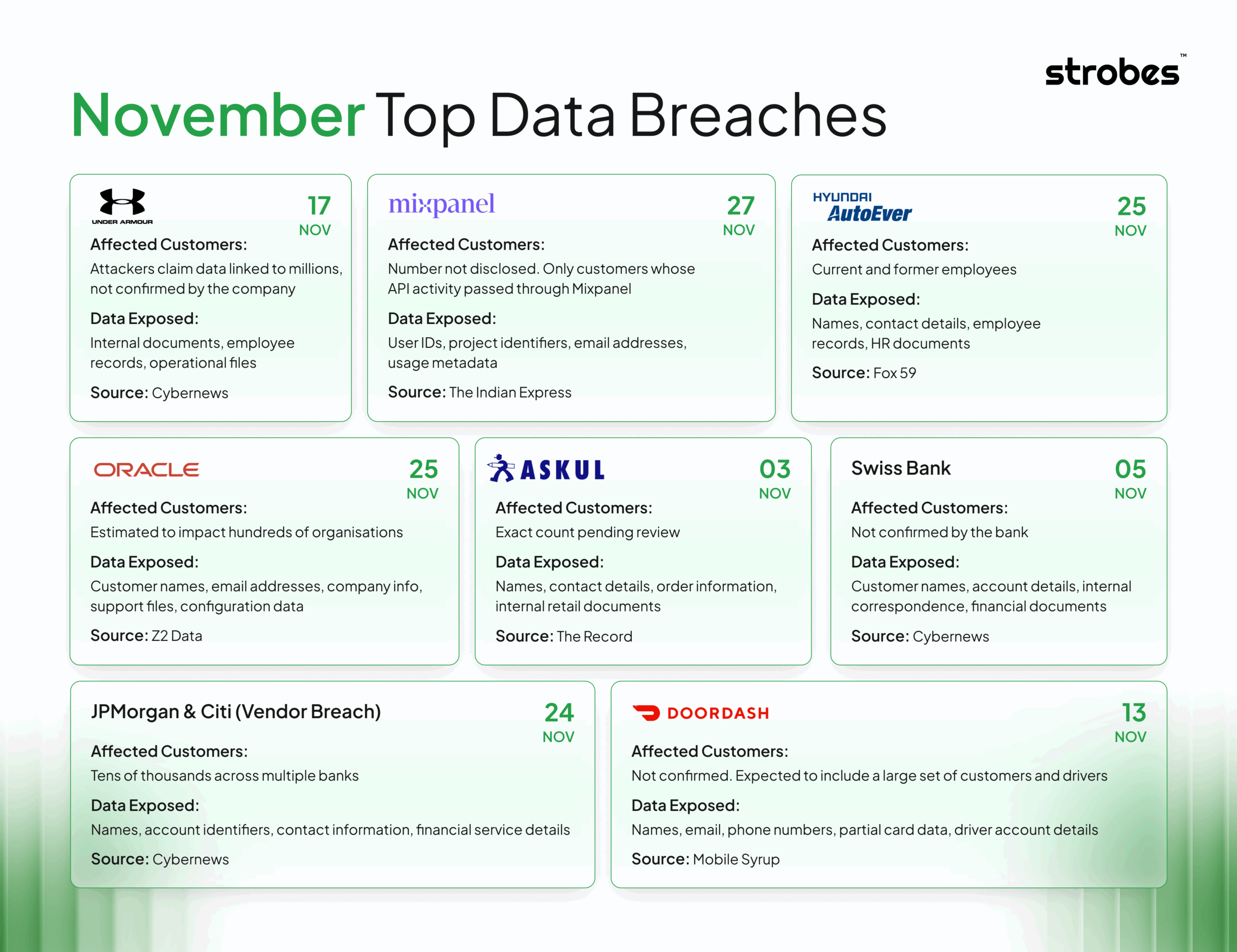

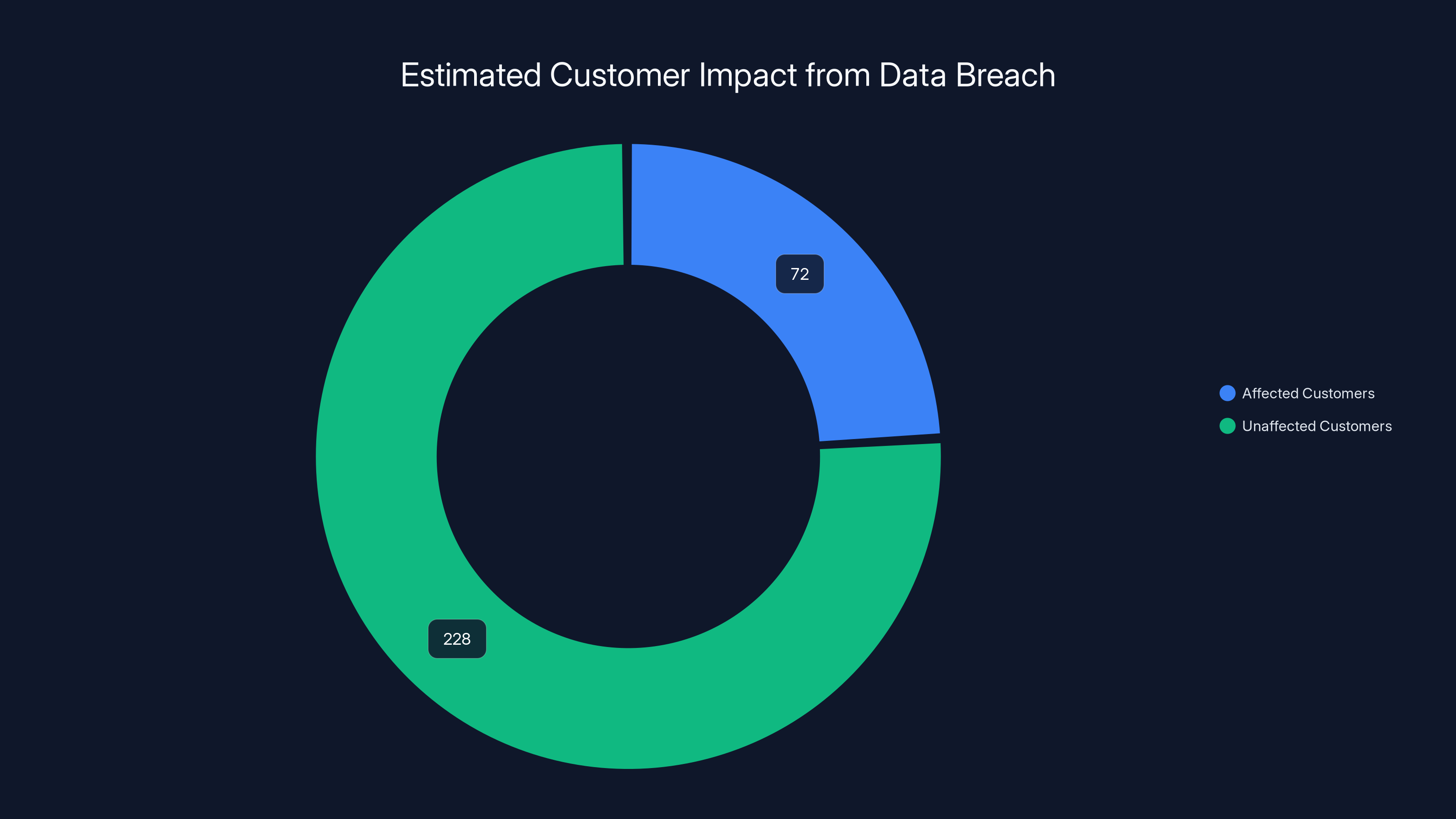

Back in November 2024, something significant happened in the cybersecurity world, but most people didn't notice until late January 2025. Under Armour, one of the world's largest athletic apparel companies, fell victim to a massive data breach. The numbers are staggering: 72 million customer records exposed. That's roughly the population of Germany, or about one in five people in the United States.

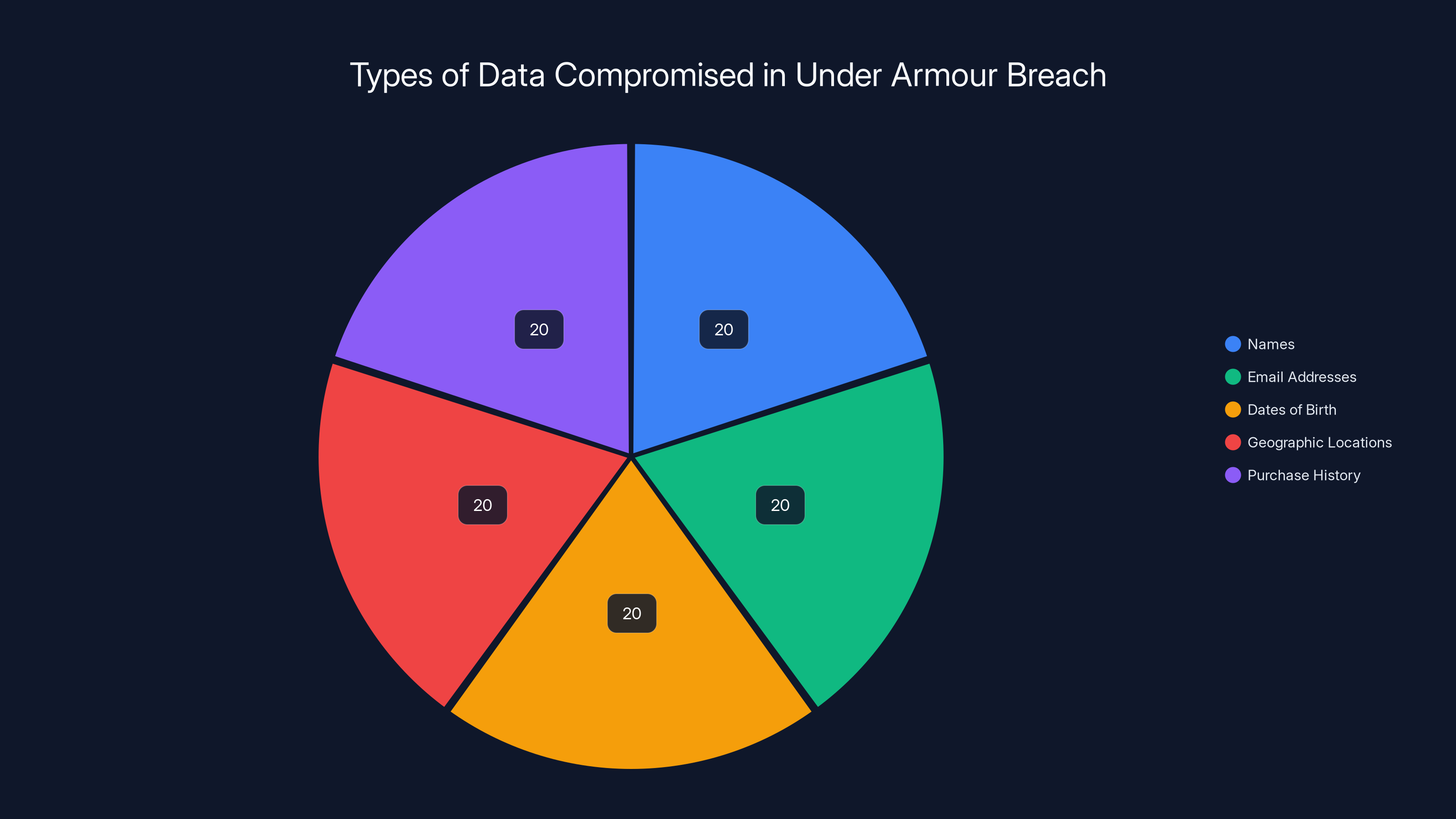

But here's what makes this breach different from the endless stream of security incidents you hear about. This wasn't just payment card data or generic user accounts. The stolen information included names, email addresses, dates of birth, approximate geographic locations based on ZIP codes or postcodes, and purchase history. For a fitness and apparel company, that data paints an incredibly detailed picture of who you are, where you live, what you care about, and how much money you spend on athletic equipment.

The breach itself happened months before anyone outside of Under Armour's security team knew about it. The Everest ransomware gang claimed responsibility for the attack in November 2024, posting notices on their dark web leak site. But the real panic started in late January 2025 when breach notification site Have I Been Pwned obtained a sample of the stolen dataset and began notifying affected individuals by email.

What's particularly frustrating about this incident is the gap between what happened and what Under Armour initially claimed about it. The company's official response suggested that only a "very small percentage" of customers had compromised data. Yet 72 million people received notification emails. That's not a small percentage—that's a substantial percentage of their customer base. The contradiction reveals a pattern we see repeatedly in major breaches: companies downplaying the severity of what happened while simultaneously being forced to admit the full scale.

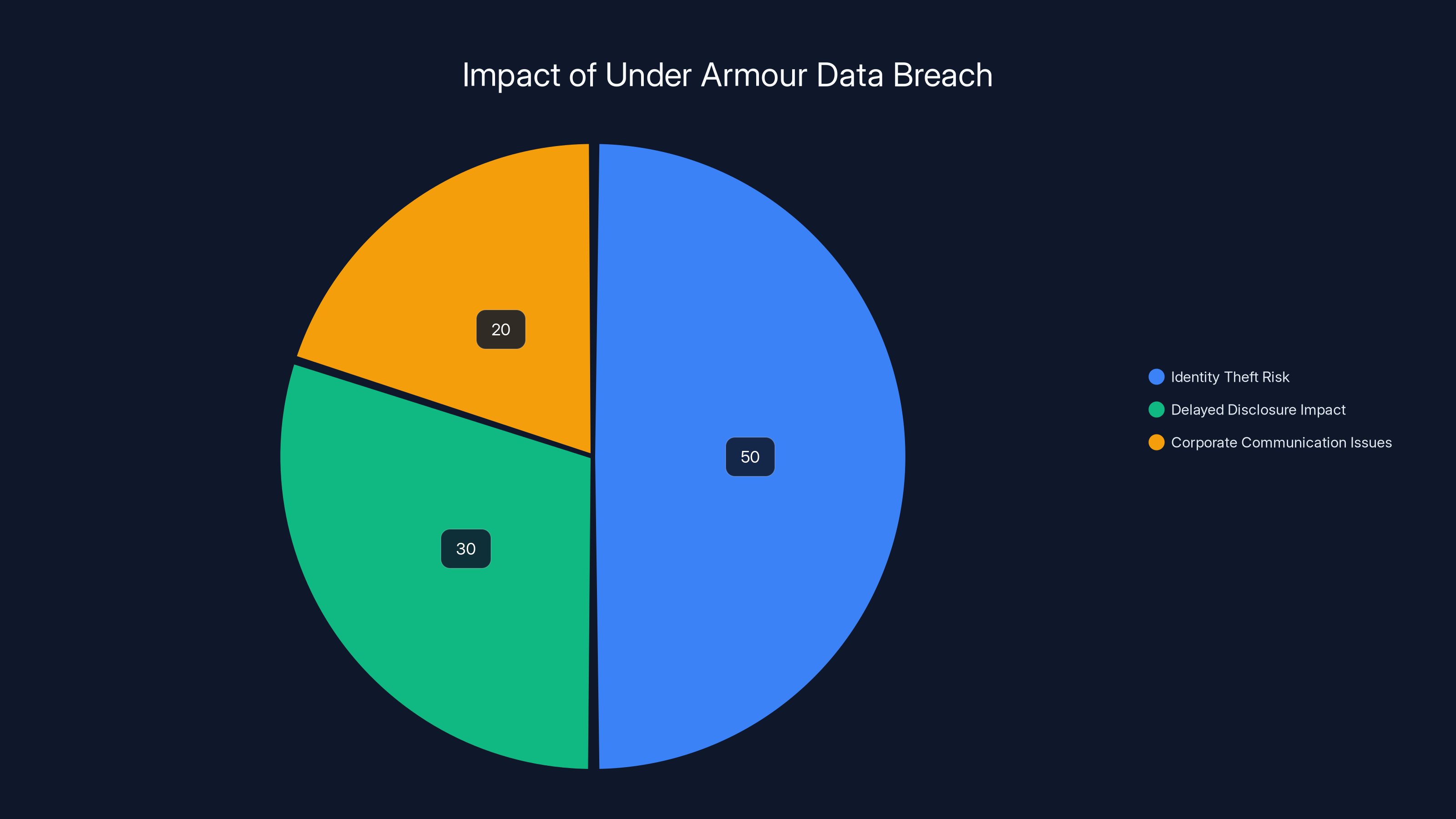

Under Armour's response team, led by spokesperson Matt Dornic, emphasized that payment systems weren't affected and customer passwords weren't exposed. That's the good news. The bad news is that the data stolen is potentially more valuable than payment cards in many cases. Names combined with emails, birthdays, and locations enable sophisticated phishing campaigns, identity theft, and social engineering attacks. Criminals can use this information to craft convincing fraud schemes that exploit personal details.

This article digs into every aspect of the Under Armour breach: what happened technically, how it impacts customers, what the company did wrong, and what lessons the entire industry should learn from this incident.

TL; DR

- 72 million customers affected: The Everest ransomware gang breached Under Armour in November 2024, stealing names, emails, birthdates, locations, and purchase history.

- Inconsistent messaging: Under Armour claimed only a "small percentage" had sensitive data compromised while 72 million people received breach notifications.

- Payment systems safe: Credit card processing systems and password databases weren't directly affected, though phishing risk increased significantly.

- No ransom details disclosed: Under Armour hasn't revealed if they received ransom demands or whether they negotiated with attackers.

- Delayed public awareness: The breach occurred in November, but public notification didn't happen until January 2025—a two-month lag.

An estimated 24-36% of Under Armour's customer base was affected by the data breach, contradicting claims of a 'very small percentage.' Estimated data.

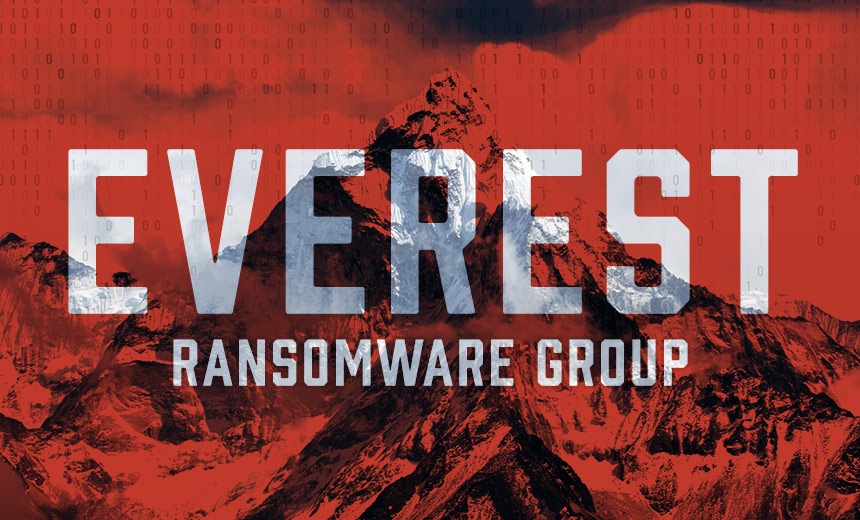

Understanding the Everest Ransomware Gang and Their Methods

When you hear "Everest ransomware gang," it sounds like a villain from a Hollywood movie. But this is real. Everest is a sophisticated cybercriminal group operating on the dark web, specializing in targeting large organizations with significant data assets. They operate using what's called a "double extortion" model, which is the standard playbook for modern ransomware gangs.

Here's how the double extortion model works in practice. First, the group infiltrates a target organization's network, often through phishing emails, stolen credentials, or unpatched vulnerabilities. They establish persistence—meaning they plant tools and backdoors that let them stay hidden inside the network long-term. Then they explore, searching for valuable data. Databases with customer information, intellectual property, financial records, anything that has worth. Once they've identified and copied the most valuable data, they deploy encryption ransomware that locks up systems and makes them unusable.

At this point, the organization faces a choice. They can refuse to pay and lose access to their systems, gambling that backups exist or that they can recover without paying. Or they can negotiate. This is where the "double" part comes in. The gang threatens to sell or publicly leak the data they stole if the organization doesn't pay. It's extortion beyond just the immediate disruption.

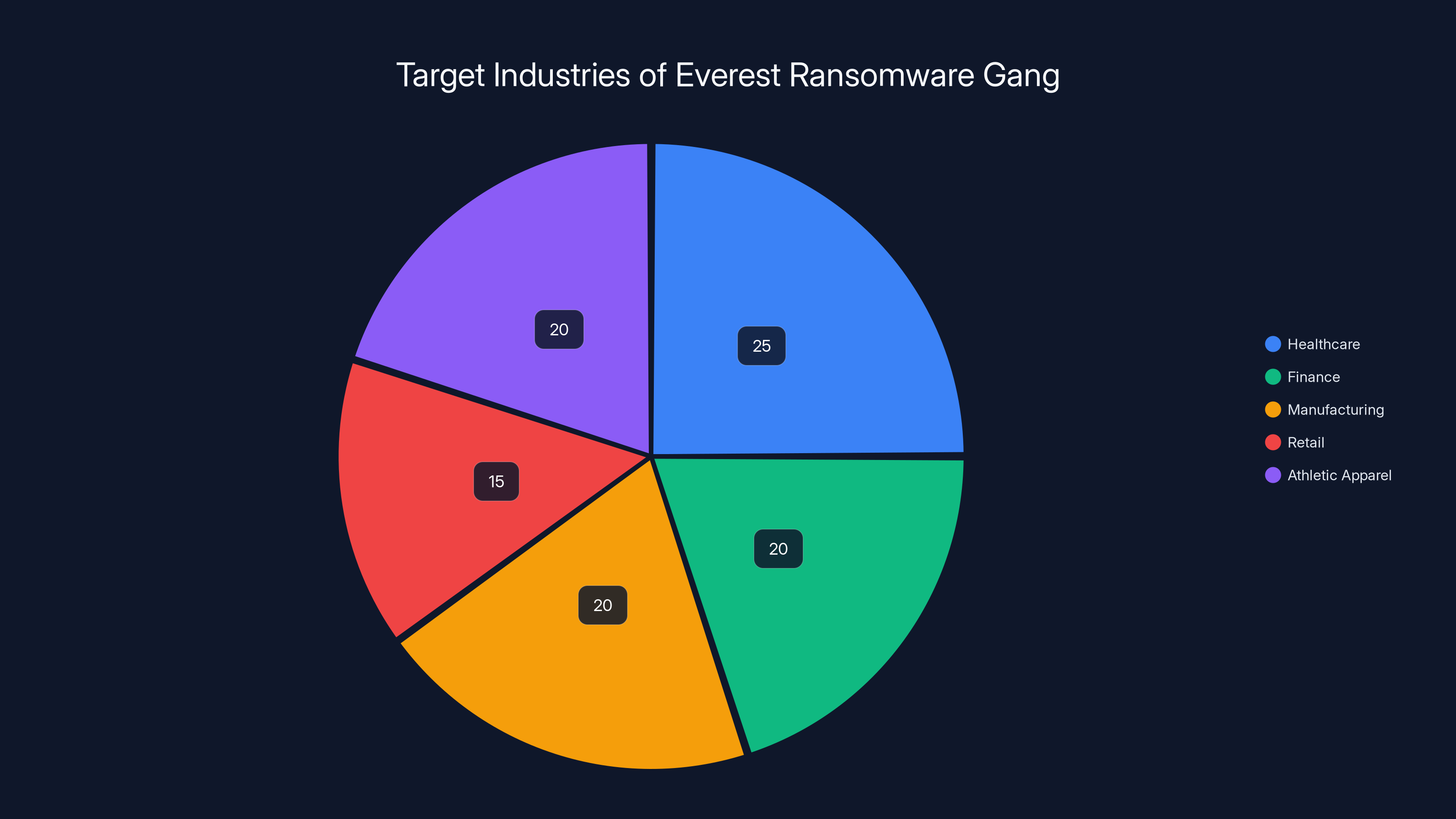

Everest, specifically, has been operating since at least 2023, though some researchers link some of their infrastructure to even older groups. They've targeted hundreds of organizations across industries: healthcare, finance, manufacturing, retail, and yes, athletic apparel. The group tends to demand ransoms ranging from $100,000 to millions of dollars, depending on the organization's size and perceived ability to pay.

What makes them particularly dangerous is their sophistication. Unlike some ransomware groups that are relatively sloppy, Everest operates with discipline. They maintain their dark web leak site consistently, they follow through on threats, and they've developed relationships with buyers for stolen data. They understand that their reputation for actually selling data or leaking it when demands aren't met is their primary leverage. If they didn't follow through, organizations would simply refuse to negotiate.

In the Under Armour case, Everest posted about the breach on their dark web leak site in November 2024, relatively quickly after the actual infiltration. This was their public announcement that they had the data. The fact that they were willing to leak or sell it suggests that either Under Armour didn't negotiate with them, or negotiations failed. Under Armour's statement that they "did not say if it had received any correspondence from the hackers, such as a demand for ransom" is notable. It's corporate-speak for "we're not commenting," which typically means something happened that management would prefer to keep quiet.

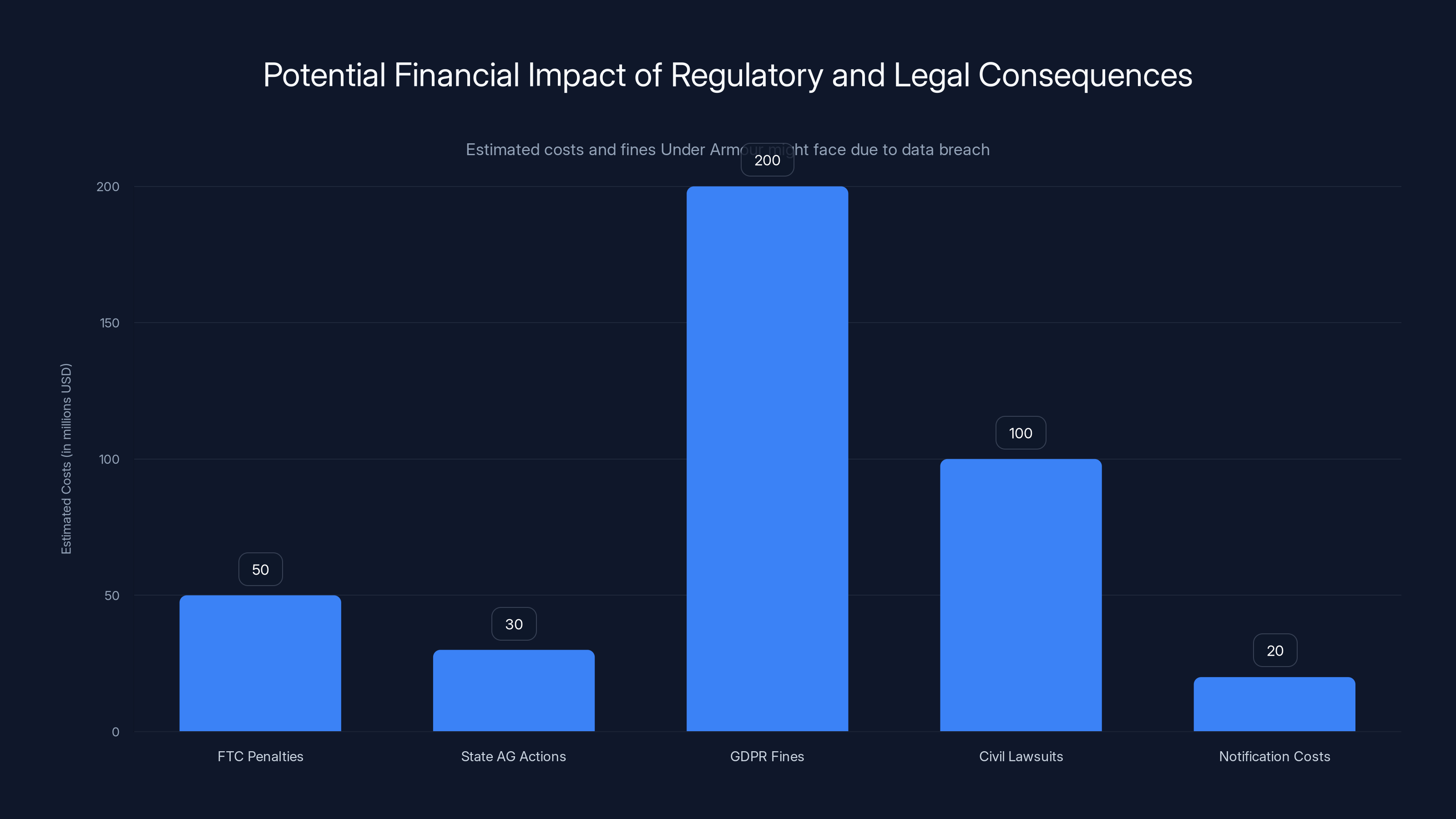

Under Armour could face significant financial impact from various regulatory and legal actions, with GDPR fines potentially reaching up to $200 million. (Estimated data)

The Data Breach Timeline: From November to Public Awareness

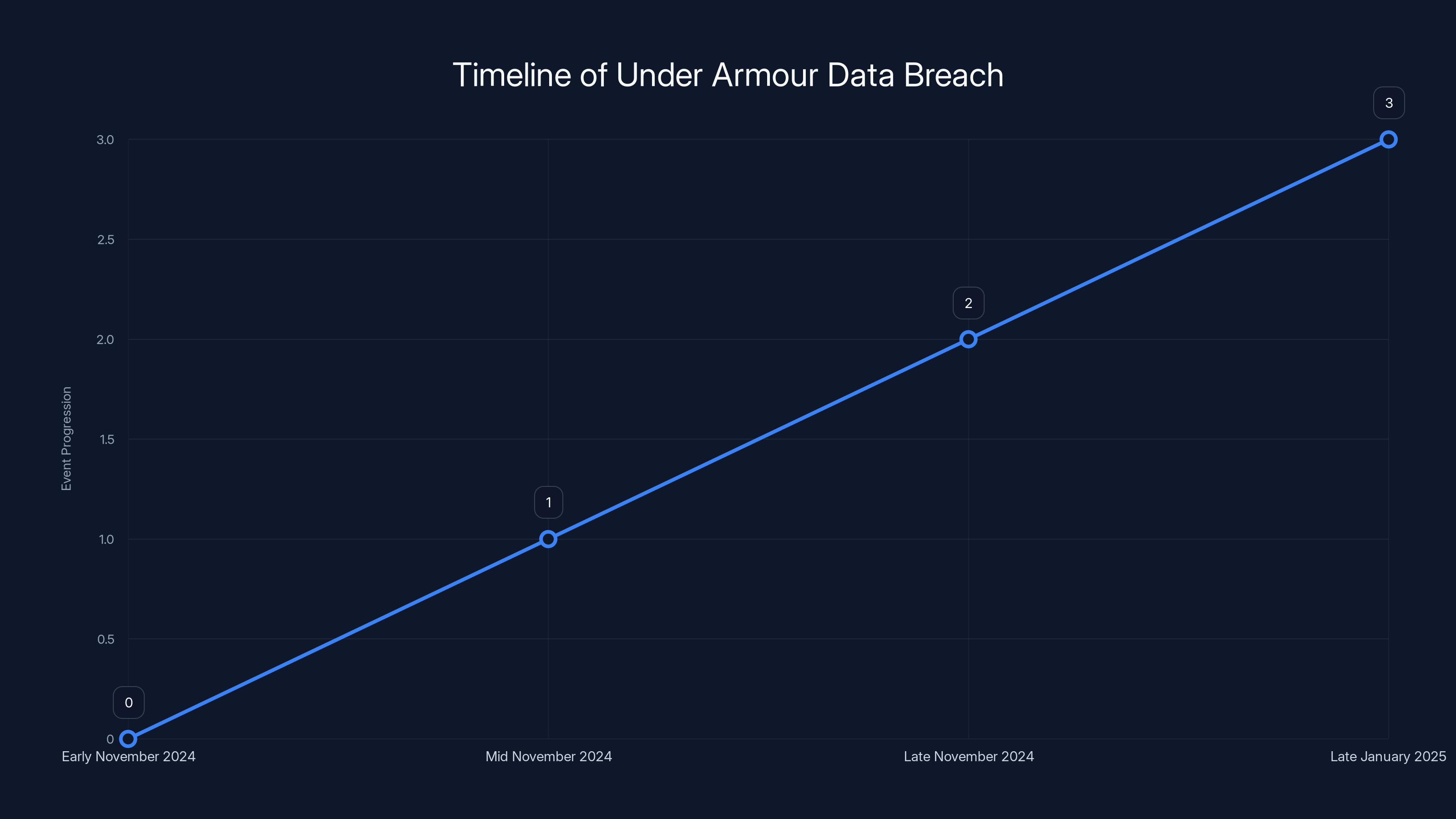

The timeline of this breach reveals important details about how long it can take for security incidents to reach public awareness. Understanding this timeline also shows the gaps in accountability and disclosure requirements across different jurisdictions and platforms.

The actual breach occurred sometime in November 2024. Based on Everest's activity, the initial infiltration likely happened days or weeks before that, with data exfiltration happening over a period of time. Cybercriminals don't just grab data instantly—they typically spend days or weeks inside a network, identifying what's worth taking, before actually extracting it. This is why they often stay undetected for so long.

Everest posted their announcement about the Under Armour breach on their dark web leak site sometime in November 2024, claiming they had 72 million customer records. This is their standard operating procedure. They announce breaches publicly on criminal forums to create urgency and potentially solicit buyers for the data.

What happened next is crucial: nothing. No public announcement from Under Armour. No mainstream news coverage. No obvious indication that anything had gone wrong. This is a common pattern. Organizations typically discover breaches through their security teams or external researchers, not through ransom notices. Internal investigation takes time. Legal and PR teams get involved. Discussions about what to disclose and when happen behind closed doors.

Then, in late January 2025—a full two months after the initial breach—Have I Been Pwned, the breached database notification site run by security researcher Troy Hunt, obtained a sample of the stolen Under Armour data. This is where the incident became public knowledge. Have I Been Pwned, which has become something of a standard clearinghouse for confirmed breaches, began notifying the affected 72 million individuals via email.

This notification triggered a cascade of events. News outlets started reporting on it. Social media amplified the story. Under Armour could no longer stay quiet, so they issued their official statement acknowledging "claims that an unauthorized third party obtained certain data." Notice the careful wording. Not "we were breached." Not "we lost customer data." They're saying they're "aware of claims." It's the kind of legal defensibility-focused language that lawyers love and customers hate.

The two-month gap between the actual breach and public awareness is significant. During that time, the stolen data was sitting on dark web marketplaces, available for purchase by anyone willing to pay. Identity thieves, spammers, phishers, and data brokers could buy or access the information. For the 72 million affected customers, their data was compromised the entire time they were going about their lives, completely unaware.

What Data Was Actually Stolen: A Detailed Breakdown

Let's get specific about what the attackers took from Under Armour's systems. This matters because data value varies enormously depending on what's included.

The confirmed stolen data includes:

- Names: Full names of customers

- Email addresses: Primary and potentially secondary email addresses associated with accounts

- Dates of birth: Complete birthdates, including month, day, and year

- Approximate location data: Geographic location based on ZIP codes or postcodes (not GPS-level precision, but approximate areas)

- Purchase history: Records of what products customers bought, when, and presumably how much was spent

- Employee email addresses: Email addresses belonging to Under Armour staff members

There's a crucial distinction in what was NOT stolen, at least according to Under Armour's statement. Payment card data, payment processor information, and customer passwords were apparently not compromised. If true, this is genuinely important because it means the immediate risk of fraudulent charges is lower than it could have been.

But let's think about what the stolen data actually enables. Someone with your name, email, birthdate, location, and purchase history can do quite a lot. They can craft a phishing email that references your actual purchases ("We noticed unusual activity on your order for the Pro-Spin 3000 running shoes from last March") making it seem credible. They can use your birthdate to attempt account recovery on other platforms where you might reuse similar recovery information. They can sell this data to people who specialize in SIM swapping attacks, where they convince mobile carriers that they're you and transfer your phone number to a device they control.

The employee email addresses are potentially even more sensitive. Companies often use predictable email address formats for employees. If an attacker knows that an employee works at Under Armour and knows a few employees' email addresses, they can generate a list of likely other employee addresses and use those for targeted spear-phishing attacks against the company from the inside.

What makes this breach particularly concerning is the quality of the data. It's not just a list of names and emails like you might get from a poorly configured database. It's a complete customer profile dataset. For a fitness and apparel company, customer data includes behavioral information that's genuinely useful for social engineering. Someone who knows you buy high-end basketball shoes, that you live in Los Angeles, that your birthday is June 15th, and your email address has a lot of information that lets them impersonate you credibly.

Have I Been Pwned, which actually analyzed the stolen data sample, confirmed that it contained millions of records with this information. The breach notification site has seen enough breaches to know what represents a serious exposure versus routine data leakage, and they treated this one as significant.

The purchase history component is worth examining separately. Some customers might have purchased fitness trackers, which themselves contain personal health data. Others might have bought specific products that indicate medical conditions or fitness challenges. A person buying heavily discounted shoes in size-specific orthopedic lines might have foot pain issues. Someone purchasing post-surgery athletic wear might be recovering from an injury. Attackers can use purchase pattern analysis to segment and target customers in sophisticated ways.

Estimated distribution of compromised data types in the Under Armour breach. Each category is assumed to be equally affected.

The Gap Between Official Claims and Actual Impact

This is where the Under Armour statement becomes particularly frustrating from a customer perspective. The company claimed that "the number of affected customers with any sort of information that could be considered sensitive is a very small percentage." Yet 72 million people received breach notifications. That's not a small percentage.

Let's do the math. Under Armour, as a fitness and apparel company serving a global customer base, likely has somewhere in the range of 200-300 million total customer records across all their brands and divisions (Map My Fitness, Connected Fitness, the main Under Armour brand, etc.). Some estimates suggest they might have even more when including historical customer data. If 72 million people were notified, that's roughly 24-36% of their potential customer base. In what definition is that a "very small percentage"?

The company's statement also emphasized that UA.com (their e-commerce platform) wasn't directly affected, and payment processing systems weren't compromised. That's important information, but it doesn't actually address the core question customers care about: is my personal information out there being sold to criminals? The answer to that question, based on the evidence, is yes.

When Under Armour says "what we know at this time is the number of affected customers with any sort of information that could be considered sensitive is a very small percentage," they're either:

- Genuinely unaware of the full scope of their breach (which would be concerning for a company's security team)

- Using a narrow definition of "sensitive information" that doesn't include what most people would reasonably consider sensitive

- Managing perception rather than providing complete information

The spokesperson's refusal to clarify what the company considers "sensitive information" is telling. If they defined it clearly, they might have to admit that their definition differs dramatically from what customers would consider sensitive. Most people think names, emails, birthdates, and locations are sensitive. Under Armour's careful non-response suggests they're hoping to avoid that direct comparison.

Technical Vulnerabilities: How Did Attackers Get In?

Under Armour hasn't released detailed technical information about how the Everest gang actually penetrated their network. This is typical—companies generally don't provide complete postmortems of security incidents because it could provide a roadmap for future attackers. But we can make some educated guesses based on what we know about how Everest operates and what typical enterprise breaches look like.

The most common entry points for modern ransomware attacks are:

Unpatched vulnerabilities: Software vulnerabilities that have known fixes but haven't been applied. Microsoft Exchange servers are a classic example—multiple zero-day vulnerabilities have been exploited by ransomware groups to gain initial network access. If Under Armour had outdated Exchange servers or other unpatched software exposed to the internet, attackers could potentially exploit them directly.

Stolen or weak credentials: If someone with access to internal systems uses the same password across multiple platforms, and that password gets compromised in another breach, attackers can attempt to log in to corporate systems. This is surprisingly common. Security researchers regularly find that employees reuse passwords or use variations of the same password across work and personal accounts.

Phishing and social engineering: An employee receives an email that appears to be from IT support or a trusted vendor, asking them to click a link or download an attachment. The email is carefully crafted to seem legitimate. The link goes to a fake login page that captures the employee's credentials. This is often the easiest way in because humans are the weakest link in security.

Third-party access: Under Armour uses numerous vendors and partners. Some of those have administrative access to Under Armour systems. If a vendor's security is weak, attackers can potentially compromise the vendor and then pivot into Under Armour's network through the established trust relationship.

Insider threats: Less common than the above, but possible. A disgruntled employee or someone bribed by attackers provides access credentials or helps establish a backdoor.

Once inside the network, attackers typically follow a pattern. They establish persistence (multiple ways to stay inside even if one method is discovered). They elevate privileges (going from a low-level user account to administrator-level access). They laterally move (spreading across the network to find data stores). They exfiltrate (copy the valuable data to an external location they control). Finally, they deploy encryption malware that locks up systems.

Under Armour stated that "at this time, there's no evidence to suggest this issue affected UA.com or systems used to process payments or store customer passwords." This suggests that the attackers' lateral movement was somewhat limited. They found and exfiltrated customer data but didn't achieve complete network compromise. Or, more likely, they exfiltrated what they wanted and left before continuing their reconnaissance that would have found payment systems.

The fact that passwords weren't compromised is significant. If password hashes were stolen, even if they're bcrypt or Argon 2 hashed (the good approaches), attackers could attempt to crack them offline. Bcrypt hashing is slow, which is exactly why it's used—it makes password cracking harder. But with time and computing power, some passwords can be cracked. The fact that Under Armour says password storage wasn't compromised suggests attackers either didn't find it or chose not to take it.

Estimated data shows identity theft risk as the largest impact area, followed by delayed disclosure and communication issues.

Customer Notification Requirements and Why They Matter

Once a breach is confirmed, most countries and jurisdictions have legal requirements about notifying affected individuals. Under Armour is based in the United States and operates globally, so they're subject to various notification laws.

In the United States, there's no single federal data breach notification law. Instead, every state has its own law (with some variations in requirements). Generally, these laws require companies to notify affected individuals "without unreasonable delay" when personal information is compromised. Some states require notification within 30 days, others are less specific.

Europe has the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which requires notification within 72 hours of discovering a breach that poses a risk to personal data rights and freedoms. Since Under Armour has European customers, they're subject to GDPR requirements.

The interesting thing about the Under Armour breach is the timeline. If the breach occurred in November and notifications started going out in January (based on Have I Been Pwned's involvement), that's more than the 72-hour GDPR requirement. However, companies often argue that they didn't "discover" a breach until they started their investigation, which can take weeks or months. This is a gray area legally.

Under Armour's statement said "Our investigation of this issue, with the assistance of external cybersecurity experts, is ongoing." This is the standard language when companies are still figuring out the scope of a breach. They're bringing in external experts (forensic investigators), who will examine logs, system artifacts, and other evidence to piece together what happened.

One thing Under Armour notably didn't announce: whether they would offer credit monitoring or identity theft protection to affected customers. Many companies offer this as a gesture of goodwill (and to reduce litigation exposure). The fact that it wasn't mentioned in their initial statement suggests either they're still deciding on this, or they're hoping it won't be expected.

The lack of proactive customer communication is also notable. Under Armour didn't send a notification email to affected customers on their own. They let Have I Been Pwned and news media break the story. This is a different approach than some companies take—some breached companies proactively notify customers before the story goes public. Under Armour took the reactive approach, waiting until the breach was already public knowledge before making any statement.

Regulatory and Legal Consequences Under Armour Might Face

Now that the breach is public, Under Armour faces potential regulatory action and legal liability. The consequences could be substantial.

FTC Investigation: The Federal Trade Commission has authority to investigate data breaches and can determine whether companies failed to maintain adequate security. If the FTC determines that Under Armour's security practices were unreasonable, they can impose civil penalties, demand improvements, and require additional audits. The FTC has pursued numerous companies over breaches in recent years.

State Attorney General Actions: Individual state AGs can take action against companies that violate their state's breach notification laws. Some states, like New York (which has strong consumer protection laws), actively pursue companies that have inadequate security.

GDPR Fines: For European customers affected by the breach, the GDPR allows for fines up to 4% of global revenue or €20 million, whichever is higher. For Under Armour, which generates roughly

Civil Lawsuits: Affected customers can potentially file class action lawsuits claiming damages. These lawsuits typically allege that the company failed to implement adequate security, that the company was negligent, and that customers suffered damages (either direct damages from fraud, or indirect damages for the cost of protecting themselves going forward). Under Armour will likely face class action suits in multiple jurisdictions.

Notification and Remediation Costs: Even setting aside fines and settlements, the direct costs of responding to a breach are substantial. Notification letters to 72 million people cost significant money. Credit monitoring services if offered. Investigation costs with external forensic firms. New security implementations to prevent future breaches. These add up quickly.

Under Armour's careful language in their statement is clearly designed to limit their legal exposure. By saying "there's no evidence to suggest this issue affected UA.com or systems used to process payments or store customer passwords," they're trying to establish a narrow scope for what was actually compromised. By saying a "very small percentage" of customers had sensitive information compromised, they're trying to minimize the severity. By not disclosing whether they received ransom demands, they're avoiding commentary on whether they negotiated with criminals.

None of this language will likely shield them from regulatory action or lawsuits, but it will influence what those actions look like. Regulators and plaintiffs' attorneys will scrutinize every claim made in the official statement.

Estimated data shows that the Everest ransomware gang targets a variety of industries, with healthcare and finance being among the most frequently attacked. Estimated data.

What Under Armour Customers Should Do Now

If you're an Under Armour customer affected by this breach, here's what actually matters: what do you do to protect yourself?

Immediate Actions:

First, change your Under Armour password if you haven't already. Don't reuse this password anywhere else. Make it unique and strong (at least 16 characters with uppercase, lowercase, numbers, and symbols). If you reused this password on other sites, change it on those sites too.

Second, monitor your accounts for fraud. Check your credit card and bank statements regularly for unauthorized charges. Many people don't notice fraud for weeks or months after a breach because they don't check carefully.

Third, consider placing a fraud alert or credit freeze on your credit file. A fraud alert tells credit bureaus to verify your identity before opening new accounts. A credit freeze prevents new accounts from being opened without your permission. Both are free. Fraud alerts are temporary (usually one year). Credit freezes are longer-lasting. Contact Equifax, Experian, and Trans Union to place these.

Fourth, watch for phishing emails. Scammers will use the knowledge that Under Armour was breached to send fake emails claiming to be from Under Armour asking you to verify your account or take some action. Don't click links in unsolicited emails. Instead, go directly to the website by typing the URL yourself.

Longer-Term Monitoring:

Consider subscribing to a credit monitoring service if you don't already use one. These services watch for new accounts opened in your name, new inquiries on your credit report, and other suspicious activity. Some are free, others cost money. The best ones are the paid versions because they tend to have better fraud detection.

Monitor Have I Been Pwned directly. Go to haveibeenpwned.com and sign up for alerts using your email address. This will notify you if your email appears in any future known breaches.

Keep an eye on your email inbox for phishing attempts. Scammers might send emails claiming to be from Under Armour about the breach, asking you to click a link or download something. These are almost certainly scams.

If You Suspect Fraud:

If you notice fraudulent charges, contact your bank or credit card issuer immediately. Under federal law (the Fair Credit Billing Act), you're typically liable for a maximum of $50 per card if fraudulent charges appear, and this is often waived entirely by card issuers.

File a report with the Federal Trade Commission at Identity Theft.gov. This creates an official record that can help with fraud investigations and may help with getting fraudulent accounts removed from your credit report.

If someone opens a fraudulent account in your name (like a credit card or loan), you may need to file a police report to prove the fraud to creditors.

How Other Companies Have Responded to Similar Breaches

Looking at how other major breaches have been handled provides context for whether Under Armour's response is typical or inadequate.

When Equifax suffered a massive breach in 2017 affecting 147 million people, the company faced immediate backlash for how long they delayed notifying the public. The breach happened months before disclosure. The company faced enormous regulatory action and eventually settled for $700 million. The incident became a cautionary tale about corporate responsibility in data protection.

When Target suffered a breach in 2013 affecting 70 million customer records (similar in scale to Under Armour), the company offered free credit monitoring to affected customers for a year and eventually paid a settlement of over $18 million. Target's CEO resigned following the breach.

When Yahoo disclosed a breach affecting 500 million user accounts in 2013 (later expanded to 3 billion accounts total), it took the company months to announce the breach, and the company's valuation dropped by nearly $350 million as a result.

When Facebook had the Cambridge Analytica scandal where user data was improperly shared with political consulting firms, the company faced FTC investigations, was fined $5 billion, and faced ongoing regulatory scrutiny.

The pattern is clear: companies that delay disclosure, understate the severity, fail to proactively notify customers, or provide unclear information face larger regulatory consequences and reputational damage. Under Armour seems to be following the worst practices from these historical examples.

When companies do it right, they:

- Disclose the breach quickly once they've confirmed it

- Provide clear, accurate information about what was compromised

- Proactively notify affected customers directly

- Offer some form of remediation (credit monitoring, identity theft protection)

- Explain what security improvements they're implementing

- Cooperate fully with regulators and investigators

Under Armour has done a few of these but not all. The company waited for public discovery rather than proactively announcing. They minimized the scope ("small percentage") when 72 million people were affected. They didn't proactively notify customers. They haven't mentioned offering credit monitoring. They've been vague about what actually happened.

The data breach, initially occurring in early November 2024, was only publicly acknowledged in late January 2025, highlighting significant delays in public awareness. (Estimated data)

The Broader Security Industry Response

Security professionals and researchers have closely followed the Under Armour breach because it reveals important patterns about enterprise security challenges.

The incident confirms that even large, well-resourced companies struggle with data protection. Under Armour isn't some small startup—it's a multinational corporation with dedicated security teams. Yet they still got breached. This suggests that the problem isn't just technical—it's also organizational and cultural.

Many security experts point out that ransomware gangs like Everest have become increasingly sophisticated in their targeting. They're not random attackers. They research their targets, identify potential entry points, and exploit them carefully. They know that large companies have more to lose financially, so they focus on them.

The breach also highlights the effectiveness of double extortion as a business model (from the attacker's perspective). By threatening to leak data unless paid, attackers create pressure beyond just the immediate system outage. Some companies find it cheaper to pay a ransom than to deal with breach notification, credit monitoring, lawsuits, and regulatory fines. This has created a perverse incentive system where paying ransoms might actually make financial sense.

Security researchers have noted that the two-month lag between the breach and public awareness is typical. Most organizations don't know they've been breached until weeks after the fact. By that time, data has already been exfiltrated and is potentially being sold on dark web marketplaces. This is why the "assume breach" mentality has become popular in security circles. You should assume your data might already be compromised and act accordingly.

The industry response to Under Armour's initial statement has been somewhat critical. Security experts have pointed out that Under Armour's claims don't match the evidence. When 72 million people receive breach notifications, that's not a "small percentage." It's a majority of your customer base. The company's attempt to minimize the incident while simultaneously confirming it happened is seen as both dishonest and ineffective (since it doesn't change the reality of the situation).

Identity Theft and Fraud Risks Specific to This Data Set

The type of data stolen in the Under Armour breach creates specific types of identity theft and fraud risks that customers should be aware of.

Identity Theft: With names, birthdates, and addresses, criminals can attempt to apply for credit in affected individuals' names. They might open credit cards, take out loans, or establish utility accounts. The victim only discovers this when bills start arriving or when their credit score tanks unexpectedly.

Account Takeover: If you reuse your password from Under Armour across other platforms, attackers can use your leaked email and password combination to log into those accounts. This is why password reuse is so dangerous.

Phishing and Social Engineering: Attackers with knowledge of your name, location, and what fitness products you buy can craft convincing emails that appear to be from Under Armour or related companies. "We noticed unusual activity on your account. Click here to verify your identity." These emails look credible because they include real information about you.

SIM Swapping: With your name, email, and birthdate, attackers can contact your mobile carrier and convince them that they're you trying to transfer the phone number to a new SIM card. Once they control your phone number, they can reset passwords on other accounts that use that number for two-factor authentication.

Medical and Financial Fraud: Your location, purchase history, and other data combined with personal information can be used to commit fraud in other sectors. If attackers see you're a fitness person in Los Angeles buying high-end athletic wear, they might try to open accounts at medical providers or financial institutions in that area.

The combination of data fields in the Under Armour breach is particularly potent for these attacks. It's not just a list of emails. It's profiles that enable targeted fraud.

The Future of Enterprise Data Security and What Needs to Change

The Under Armour breach points to several systemic issues in how organizations approach data security. If the industry doesn't change, we'll keep seeing similar incidents.

Challenge 1: Complexity of Enterprise Networks: Modern enterprises use hundreds or thousands of applications and services. Cloud platforms, on-premises servers, third-party integrations, APIs, mobile applications—it's a complex landscape. Securing all of it is genuinely hard. This complexity creates gaps that attackers exploit.

Challenge 2: Legacy Systems: Many large enterprises still run systems built 10+ years ago that were never designed with current security threats in mind. Patching legacy systems is risky (they might break), updating them is expensive, and replacing them is a multi-year project. Meanwhile, attackers target these weak points.

Challenge 3: Humans as the Security Weak Link: Most breaches start with a human making a mistake. Clicking a phishing link, reusing passwords, leaving credentials in code, failing to enable multi-factor authentication. Technology can help, but ultimately organizations need to prioritize security training and culture.

Challenge 4: Pressure to Minimize Security Costs: Security is often seen as a cost center rather than a business priority. Companies invest less in security infrastructure than they should, making breaches more likely. This only gets addressed after a breach happens and suddenly security budgets increase dramatically.

Challenge 5: Speed vs. Security Tradeoff: Businesses want to ship features and updates quickly. Security slows things down. It's easier and faster to patch things after they're deployed than to secure them during development. This creates technical debt that eventually leads to incidents like this.

What needs to change:

- Zero Trust Architecture: Instead of assuming that once you're inside the network you're trusted, assume every access attempt is potentially compromised. Verify everything, always.

- Data Minimization: Collect only the data you actually need. The less data you have, the less data can be breached.

- Encryption: Data at rest and in transit should be encrypted. This makes stolen data much harder to use.

- Incident Response Readiness: Organizations should have detailed incident response plans, with regular testing and drills.

- Security Culture: From the CEO down, organizations need to prioritize security as a core business value, not an afterthought.

Under Armour's breach suggests the company didn't do all of these things well. A truly secure organization would have made it much harder for attackers to exfiltrate customer data at scale.

FAQ

What exactly was the Under Armour data breach?

In November 2024, Under Armour suffered a data breach where cybercriminals from the Everest ransomware gang accessed and stole customer data belonging to approximately 72 million individuals. The stolen information included names, email addresses, dates of birth, approximate geographic locations, and purchase history. Under Armour confirmed the breach in late January 2025 after the data was posted publicly by Have I Been Pwned.

How did attackers access Under Armour's systems?

Under Armour has not publicly disclosed the specific technical method used by attackers to infiltrate their systems. However, based on common attack patterns, the breach likely resulted from one or more of these vectors: unpatched software vulnerabilities, compromised employee credentials through phishing or password reuse, weak third-party access management, or other social engineering tactics. The company stated that payment processing systems and password databases were not directly compromised.

Is my payment information at risk from this breach?

According to Under Armour's statement, payment processing systems were not affected by the breach, and they found "no evidence" that payment card data was compromised. However, the stolen information (names, emails, birthdates, locations) still poses significant risk for identity theft and phishing attacks that could potentially lead to fraud through other means.

What should I do if I was affected by the Under Armour breach?

If you received a breach notification, immediately change your Under Armour password to something unique and strong, and change the password on any other accounts where you reused the same password. Monitor your credit reports and bank statements for fraudulent activity. Consider placing a fraud alert or credit freeze on your credit file by contacting Equifax, Experian, and Trans Union. Watch for phishing emails and avoid clicking links in suspicious communications claiming to be from Under Armour.

Why did it take two months for the breach to become public?

Under Armour likely discovered the breach through its security team sometime after the November attack, and then spent weeks or months investigating the scope and impact with external forensic experts. The public only became aware on January 2025 when breach notification site Have I Been Pwned obtained the stolen data and began notifying affected individuals. This delay is unfortunately common—the average time between breach occurrence and public discovery is over 200 days.

What does "double extortion" mean in the context of this breach?

Double extortion is a ransomware strategy where attackers both encrypt a company's systems (making them unusable) and threaten to publicly leak or sell stolen data unless the company pays a ransom. This creates two pressure points for payment: system downtime that costs the company money, and the threat of data exposure that creates regulatory and reputational harm. Under Armour stated they couldn't comment on whether they received ransom demands.

Could this data be used to commit fraud against me even without my password or payment card?

Yes, absolutely. With your name, email address, birthdate, location, and purchase history, attackers can conduct phishing attacks (using real information to make fake emails seem credible), attempt account takeover on other platforms if you reused your password, commit identity theft by opening accounts in your name, or even orchestrate SIM swapping attacks to gain control of your phone number. This data is valuable for sophisticated fraud even without direct payment card access.

What penalties might Under Armour face for this breach?

Under Armour could face regulatory action from the Federal Trade Commission and state attorneys general for failing to implement adequate security. They may face fines under GDPR for European customers (up to 4% of global revenue in the worst case, though typically much lower). The company will likely face class action lawsuits from affected customers claiming damages. Direct costs also include investigation, notification, credit monitoring services, and security improvements to prevent future breaches.

Is my location data as sensitive as my payment card number?

Your location data combined with your name, birthdate, and email is quite sensitive, though in a different way than payment card data. Payment card fraud is immediate and detectable. Location-based fraud tends to be slower and more targeted—it enables identity theft, targeted phishing, and fraud that's harder to trace. Over time, location combined with purchase history and personal details might be more valuable than a single credit card number.

What can I do to prevent my personal data from being exposed in future breaches?

Use unique, strong passwords for every online account so that if one company is breached, your other accounts remain protected. Enable multi-factor authentication everywhere it's available. Minimize the personal data you share with companies—only provide what's absolutely necessary. Monitor your credit reports regularly. Be skeptical of unsolicited communications and never click links in suspicious emails. Consider using a password manager to keep track of unique passwords across many accounts.

Key Takeaways

- 72 million customers compromised: The Everest ransomware gang breached Under Armour in November 2024, accessing names, emails, birthdates, locations, and purchase history.

- Delayed disclosure created two-month exposure window: The breach occurred in November but wasn't publicly known until January 2025, during which time stolen data was available on dark web marketplaces.

- Under Armour minimized scope while evidence suggests otherwise: The company claimed "a very small percentage" had sensitive data compromised while 72 million people received breach notifications.

- Payment systems reportedly safe but identity theft risk remains high: Credit card processing wasn't affected, but the stolen data enables sophisticated phishing, social engineering, and identity theft attacks.

- Regulatory consequences likely: Under Armour faces potential FTC investigations, state attorney general actions, GDPR fines for European customers, and class action lawsuits from affected customers.

- Systematic security failures in enterprise organizations: The breach reflects common patterns in how large companies struggle with data protection despite having dedicated security teams and resources.

Conclusion

The Under Armour data breach affecting 72 million customers represents a significant failure in how a major corporation protected customer data. The incident is notable not just for its scale, but for how the company responded to it—with carefully minimized language, delayed public acknowledgment, and incomplete information that contradicts the evidence.

For the affected customers, the immediate advice is straightforward: change passwords, monitor credit reports, watch for phishing, and consider additional protective measures like fraud alerts or credit freezes. The risk isn't primarily about immediate fraudulent credit card charges (since payment systems weren't directly compromised). Instead, the risk is longer-term identity theft and fraud that exploits the personal details now circulating on dark web marketplaces.

For the industry, the Under Armour breach reinforces lessons that should have been learned years ago. Large-scale data breaches are not a matter of if but when. Organizations need to assume that their networks will be compromised and build defenses accordingly. Data should be encrypted, minimized, and protected with layered security controls. Incident response plans need to be ready before a breach happens, not developed during one.

The two-month lag between the actual breach and public awareness is particularly troubling. During that entire period, the 72 million affected customers had no idea their data was for sale on criminal marketplaces. Better disclosure timelines would have given them faster warning to protect themselves.

Finally, Under Armour's careful language attempting to minimize the breach while simultaneously confirming it serves as a reminder that corporate communications about security incidents are almost always framed to reduce legal liability rather than provide complete transparency. Customers and regulators should be skeptical of these narratives and look at the actual evidence instead.

This breach will likely result in regulatory action, lawsuits, and eventually a substantial financial settlement for Under Armour. But for the 72 million affected individuals, the real cost isn't in the abstract regulatory consequences—it's in years of needing to monitor their credit, watch for fraud, and deal with the fallout if attackers succeed in using this data for identity theft. That's the human cost of inadequate corporate data security.

Related Articles

- SMS Sign-In Links: A Critical Security Vulnerability Affecting Millions [2025]

- UStrive Security Breach: How Mentoring Platform Exposed Student Data [2025]

- 198 iOS Apps Leaking Private Chats & Locations: The AI Slop Security Crisis [2025]

- UK VPN Ban Explained: Government's Online Safety Plan [2025]

- PcComponentes Data Breach Denial: What Really Happened [2025]

- 1Password Phishing Protection: How the New Browser Feature Saves You [2025]

![Under Armour 72M Record Data Breach: What Happened [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/under-armour-72m-record-data-breach-what-happened-2025/image-1-1769096418215.jpg)