Introduction: The End of an Era Nobody Wanted to See Coming

There's something almost poetic about Allbirds closing its last flagship store in San Francisco in early 2025. Not tragic, not surprising, but poetic in the way that watching a specific chapter of your life close down feels when you know something fundamental has shifted. For a decade, those soft wool sneakers became shorthand for a particular kind of person: someone who worked in tech, believed in sustainability, could afford thirty percent markups on shoes, and wore their comfort-first ideology like a badge.

But here's what's actually happening beneath the surface of this store closure. It's not just about retail. It's not even really about shoes. What we're witnessing is the final collapse of a specific economic model that powered Silicon Valley for nearly two decades. The unicorn-to-IPO-to-profitability pipeline is breaking. Venture capital's math stopped working. And the companies that rode that wave into public markets are now choking on the reality of actual unit economics.

Allbirds launched in 2015 with a simple premise: make comfortable shoes using sustainable materials, sell them for

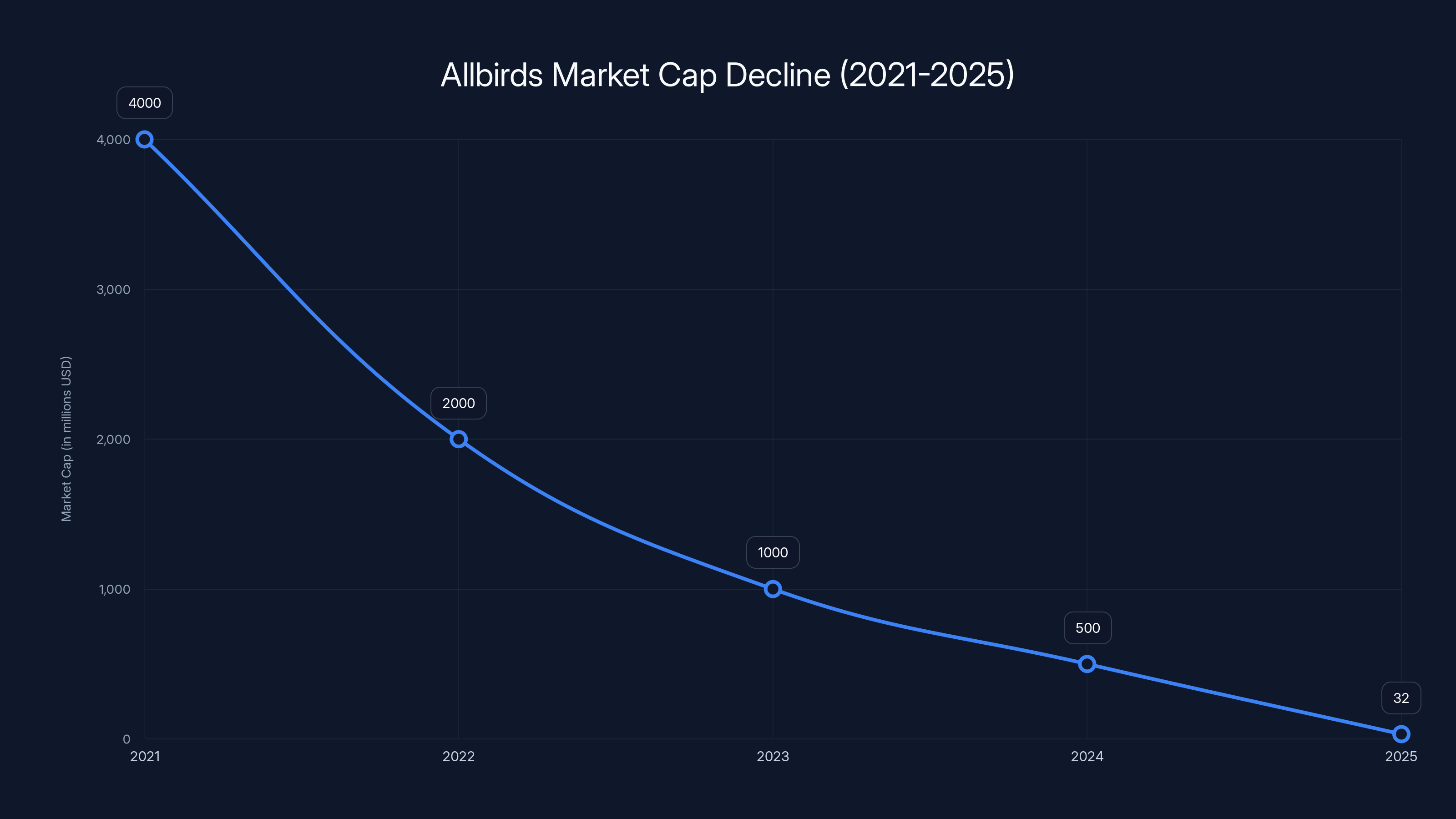

Then came the crash. Not the dramatic overnight kind, but the slow, grinding erosion kind. Within four years, Allbirds' market cap collapsed from billions to roughly $32 million. The stock price, once a symbol of growth and innovation, now hovers in the low single digits. And now, with the closure of its remaining North American retail footprint, the company is attempting what amounts to a controlled demolition of its original business model.

What makes this story worth understanding isn't the shoe company itself. It's what this tells us about how venture capital misallocated capital for fifteen years, how the IPO window made mediocre companies seem revolutionary, and how an entire generation of founders learned to prioritize growth-at-any-cost over actually building something that customers wanted to pay full price for. Allbirds didn't fail because sustainable footwear is a bad idea. It failed because the business model—go public fast, worry about profitability later—finally caught up with it.

Let's dig into why.

TL; DR

- Allbirds closing all but 4 stores by end of February 2025, pivoting entirely to e-commerce and outlets to reduce operating costs as reported by WWD.

- Company valuation collapsed from 32 million, reflecting the brutal reality of public market scrutiny after 2021 IPO, according to CNBC.

- Brick-and-mortar retail never made sense for a direct-to-consumer brand that built its entire value proposition around online convenience and sustainability, as noted in GlobeNewswire.

- This shutdown represents a failed venture capital experiment where overvaluation, endless funding, and the IPO craze created unsustainable burn rates, as highlighted by Simply Wall St.

- Real lesson: Profitable growth beats growth-at-any-cost, and the market finally stopped rewarding companies that confused top-line revenue with actual business viability.

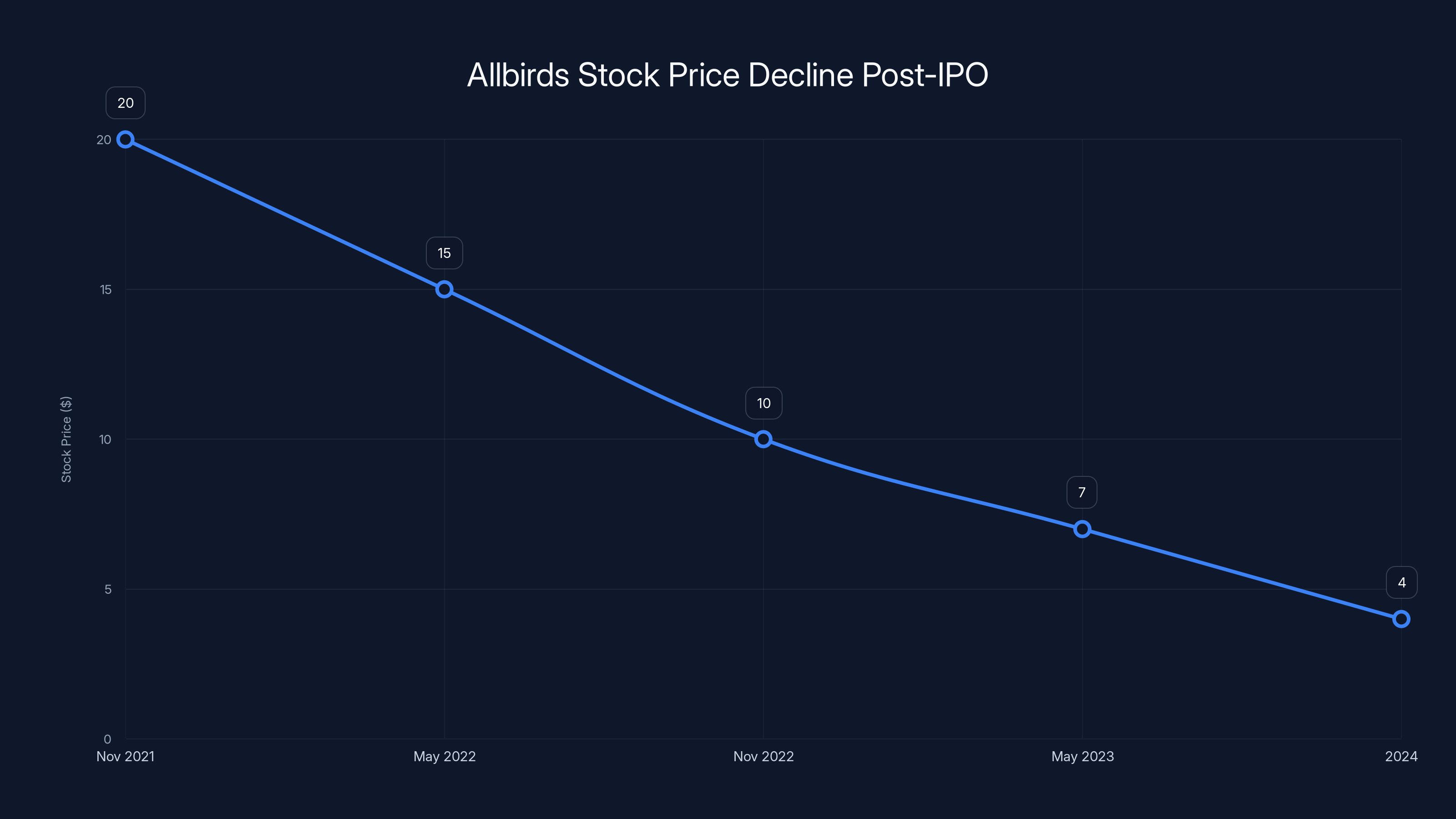

Allbirds' stock price dropped from

The Rise: How Allbirds Became a Symbol (2015-2020)

When Allbirds launched in 2015, the company nailed something that venture capital loves: a founder story wrapped in sustainability messaging. Tim Brown and Joey Zwillinger started the company because they wanted to prove that you could make a genuinely comfortable shoe using sugarcane foam, merino wool, and recycled plastic bottles. The messaging was perfect: comfortable, sustainable, not-Ugly-but-not-pretentious.

Early adoption came fast, and it came from the right demographic. Startup employees at Series A companies, venture capitalists who wanted to signal alignment with sustainability, and the broader tech workforce that had grown tired of dress codes and wanted shoes that screamed "I work somewhere casual and cool." By 2018, Allbirds had raised

The brand strategy was brilliant because it worked on multiple levels. First, the shoes actually were comfortable—this wasn't vaporware. Second, the sustainability angle was real enough to satisfy people's ethical concerns without requiring them to pay a massive premium. And third, the price point sat in a fascinating sweet spot: expensive enough to feel premium and exclusive (you're not buying these at Target), but accessible enough that a mid-level engineer or startup employee could justify the purchase without too much guilt.

But here's where the venture capital lens started to distort everything. Once Allbirds proved the business model worked online, investors wanted something bigger. They didn't want a

By 2020, Allbirds had physical locations on the way to becoming a retail chain. The company was burning cash at an increasing rate, but the venture narrative was strong: pre-IPO scaling, multiple revenue streams, global presence. It all sounded great in investor presentations.

The IPO Moment: When Growth Became the Only Metric (2021)

Allbirds went public on November 10, 2021, at

For about six months, the stock actually performed reasonably well. But by mid-2022, something shifted. The venture capital market cooled. Interest rates started climbing. Investors began asking uncomfortable questions about unit economics, customer acquisition costs, and when this company would actually make money on a GAAP basis. For a company that had been designed entirely around the VC growth thesis—"scale first, profitability later"—this was catastrophic.

The problem was structural. Allbirds had built a business that required constant capital infusions to chase growth. Manufacturing costs were high because the materials were expensive. Customer acquisition costs were astronomical because the company had to spend $40-60 to acquire a customer in a crowded footwear market. And operating those physical retail stores was a fixed cost nightmare that didn't make sense when the company was already crushing it online.

When the IPO window slammed shut and the company had to actually run like a public business—with quarterly earnings reports, analyst calls, and investor scrutiny—the model fell apart almost instantly. The stock, which opened at

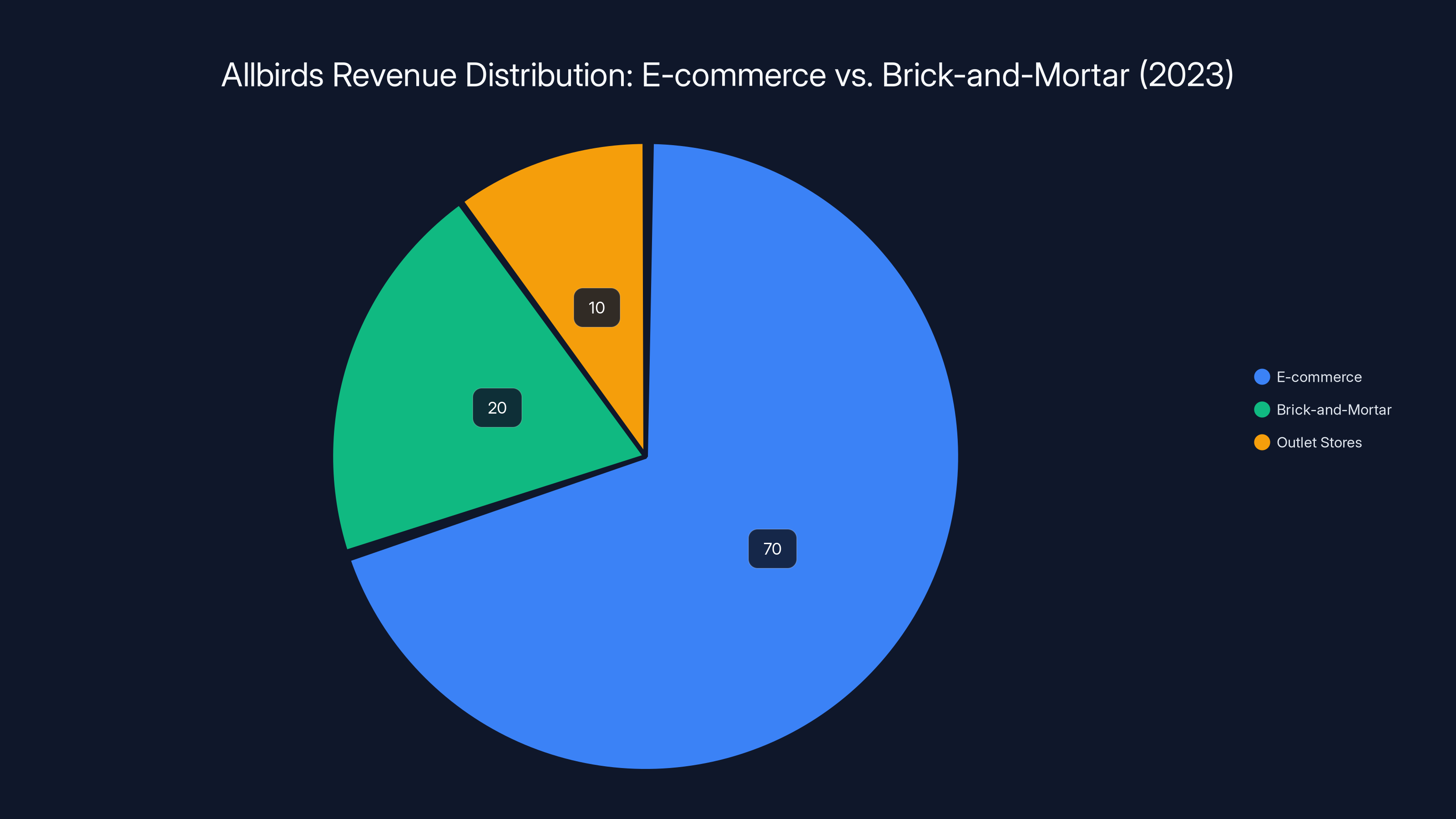

Estimated data shows a strong shift towards e-commerce, which is expected to account for 70% of Allbirds' revenue as the company realigns its strategy towards profitability.

The Realignment: From Growth-at-Any-Cost to Actual Profitability (2023-2024)

Once you're a public company, you can't hide negative unit economics for very long. Quarterly earnings reports are legal documents. Investors can sue you. The board gets nervous. And by late 2022, Allbirds' leadership realized they had a choice: continue bleeding money on the growth narrative, or actually build a profitable business.

Under CEO Joe Vernachio (who took over in 2022), the company started making hard decisions. Close unprofitable stores. Kill unprofitable product lines. Stop chasing growth metrics that don't translate to actual profit. This is exactly what the company should have done before going public, but the venture capital incentive structure made that impossible at the time.

The store closures represent the final stage of this realignment. Brick-and-mortar retail was always the wrong decision for Allbirds. The company's entire value proposition was built around e-commerce: you see the shoes online, you're inspired by the sustainability story, you order them, they arrive at your door in two days. There's no reason for Allbirds to occupy a $50,000-per-month storefront in San Francisco when 90% of customers never set foot in it.

But investors wanted "omnichannel retail presence." Competitors like Nike and Adidas had stores. So the narrative became: Allbirds needs physical retail too. That narrative cost the company hundreds of millions of dollars in losses, and it took three years of being a public company before leadership finally admitted it was wrong.

The 2024-2025 store closure strategy is basically the company saying: "We're going back to what actually worked." Pivot to e-commerce. Keep a handful of outlet stores for clearance inventory. Operate lean. Stop trying to be a

The Venture Capital Problem: Why Growth-at-Any-Cost Economics Failed

Here's the thing about venture capital that's important to understand: it's not trying to create profitable businesses. It's trying to create outcomes where one of your bets returns 100x or more, allowing you to absorb losses on all the other bets. That works great if you're picking individual companies. It fails catastrophically when it becomes the dominant funding model across entire industries.

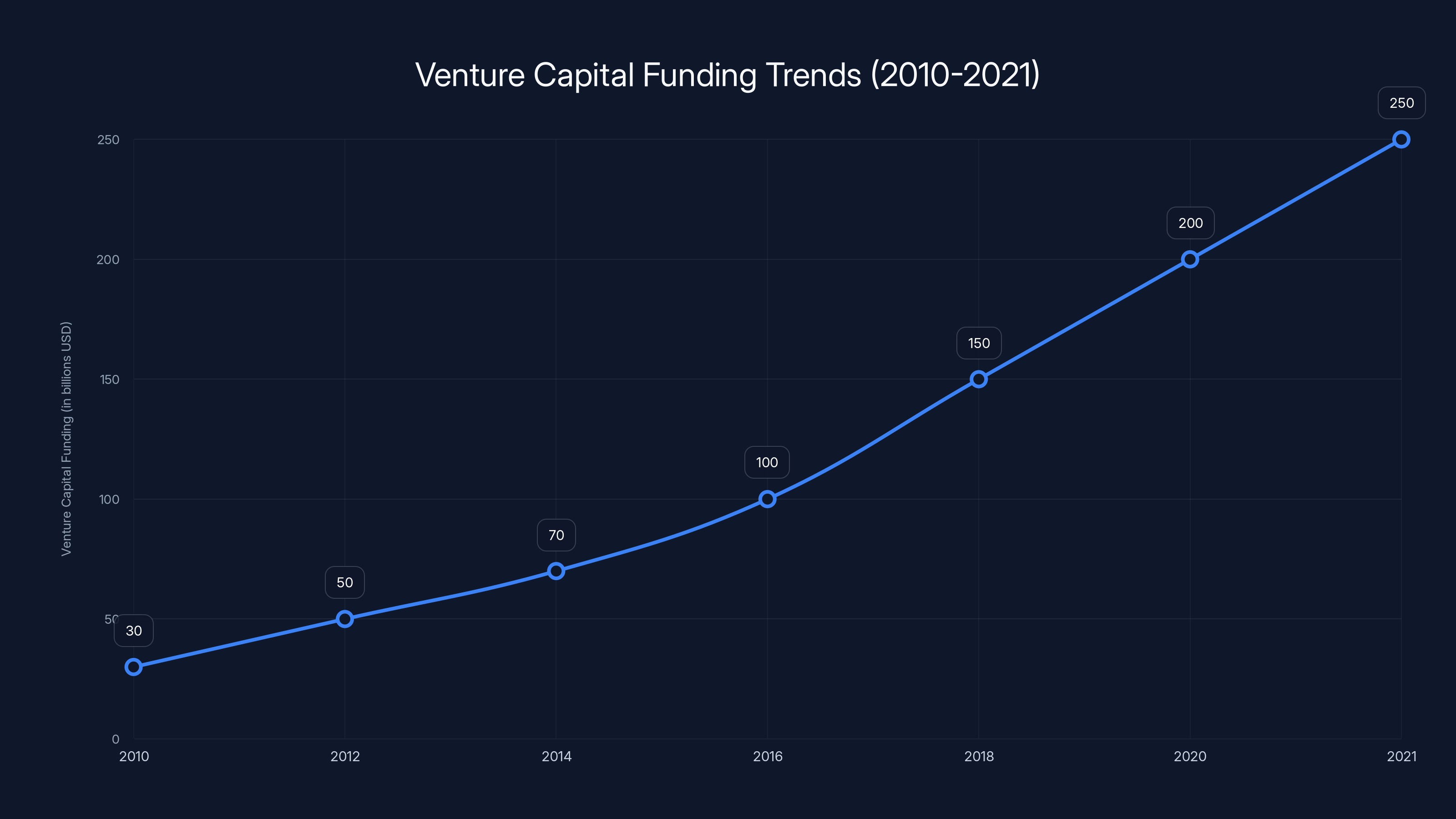

Between 2010 and 2021, venture capital was absolutely swimming in money. The Federal Reserve was keeping interest rates near zero. Institutional investors were desperate to find returns in an environment where bonds paid nothing. So VC firms raised enormous funds—

This created a particular kind of dysfunction in how companies scale. Instead of optimizing for profitability, founders were optimized for fundraising. Instead of focusing on unit economics, they focused on top-line revenue growth. Instead of asking "do customers really want to buy our product at this price point," they asked "how can we maximize user growth by spending investor capital aggressively."

Allbirds is an almost perfect case study of this dynamic. The company had legitimate product-market fit. People actually loved the shoes. But then, because the capital was available and the narrative was compelling, the company spent investor capital as fast as possible to chase a much bigger outcome. Open stores. Expand internationally. Build out multiple product categories. Do everything at once because VC capital rewards speed and scale, not wisdom and sustainability.

When the capital dried up and the company had to operate within the constraints of actual profit, it turned out that the "optimal" scale was about 50% of what the company had been burning capital to achieve. The optimal model was probably: 1,500 employees instead of 3,500. Direct online channels instead of wholesale retail. Focused product lines instead of expanding into apparel. Revenue of maybe

In other words, Allbirds became valuable when it stopped trying to be venture capital's fantasy and started trying to be an actual business.

The Brick-and-Mortar Mistake: Why Physical Retail Never Made Sense

Let's talk specifically about the store closures, because they're incredibly revealing. Physical retail stores have overhead: rent, utilities, staff, inventory management, loss to shrinkage, and all the fixed costs that come with maintaining a physical presence. For a brand like Nike or Adidas that operates wholesale channels, physical stores make sense as a way to control the customer experience and maintain brand premium pricing.

For a direct-to-consumer brand that built its entire growth story around e-commerce, physical stores are almost always a mistake. Allbirds proved this empirically. When the company had the capital to spend freely, it opened stores in major markets. When it didn't, it closed those same stores. The stores probably weren't even net negative on a unit basis if you account for the halo effect they created—maybe customers who visited a store were more likely to buy online.

But "halo effect" is the kind of fuzzy metric that venture capital loves and actual profit-and-loss statements hate. When you're a public company and your stock is declining, you need to point to specific drivers of profit. "We're spending $10 million a year on stores because they create a halo effect on online sales" doesn't survive a 10-Q filing.

There's a larger pattern here too. In the 2015-2021 period, e-commerce was supposed to kill retail. Amazon was supposed to bankrupt every brick-and-mortar business. But instead of creating a world where only pure-play online brands thrived, what actually happened was that online brands took that narrative, raised a ton of money, opened physical stores, burned through capital, and then retreated back to e-commerce. Warby Parker opened hundreds of locations. Glossier opened stores. Allbirds opened stores. They all either closed them or significantly scaled them back.

The lesson that venture capital refused to learn: maybe e-commerce was actually the right channel for these brands in the first place. Maybe opening physical stores wasn't "omnichannel excellence," it was just capital inefficiency disguised as strategy.

Venture capital funding saw a significant increase from 2010 to 2021, driven by low interest rates and a search for high returns. (Estimated data)

Market Cap Collapse: From 32 Million in Four Years

Let's talk about the numbers because they're staggering. At its peak valuation (2021, right around the IPO), Allbirds was worth approximately

What's remarkable is that the company is still generating revenue. It's still profitable (or close to it now). Customer lifetime value is probably still positive. The core product is still good. But the market has revalued the company because growth has stopped. A

This is what every founder needs to understand about venture capital: you're not just raising money, you're signing up for a narrative contract. You have to deliver growth that justifies increasingly absurd valuations. If you don't, the market will revalue you brutally. And if you're a public company, that revaluation happens in real time on the stock market, where every shareholder can see exactly how much money they've lost.

Allbirds' shareholders lost billions of dollars of value. The company had to lay off thousands of employees. The founders who became billionaires on paper suddenly found those paper fortunes worth nothing. And all because the venture capital model demanded growth at any cost, and the market eventually demanded actual profitability instead.

It's important to note that this isn't Allbirds specifically being poorly managed after the IPO. The company actually did the right thing by aggressively cutting costs and refocusing on profitability. This is a systemic problem with how venture capital inflates valuations in the first place.

The Profitability Pivot: Why Allbirds Had to Shut Down

When Vernachio took over as CEO in 2022, he inherited a company that was losing money and had just gone public at the worst possible moment. The venture capital spigot was closing. The IPO window was slamming shut. And he had to make a choice: continue pretending the growth story was viable, or make the hard decisions required to actually make money.

To his credit, he chose the latter. Allbirds began a systematic review of its business. Which product categories made money? Direct-to-consumer channels. Which ones didn't? Wholesale retail partnerships, physical store locations, and international expansion into markets where the brand had low awareness. Which marketing channels were efficient? Direct email, social, word-of-mouth. Which ones weren't? Everything else.

The company cut headcount aggressively. It killed product lines. It exited certain international markets. It reduced marketing spend on low-ROI channels. And it closed physical stores. Each of these decisions probably destroyed shareholder value temporarily—the stock likely would have benefited in the short term from pretending everything was fine and the growth story was intact. But over time, a company needs actual profitability to be worth anything.

What's interesting is that if Allbirds had made these decisions before going public, the company might have gone public at a more reasonable valuation and investors would have actually made money. A

The Sustainable Footwear Category: A Good Idea, Badly Capitalized

It's worth pausing here to acknowledge that the underlying product category isn't inherently broken. People actually do want comfortable shoes. People actually do care about sustainability. There's a real market for footwear that doesn't destroy the environment. Allbirds proved that.

The problem is that sustainable footwear has lower margins than conventional footwear because the materials are more expensive. You can't manufacture sustainably on the same margins as Nike can manufacture with cheap labor in Southeast Asia. So if you're building a sustainable footwear company, you have a few options:

- Compete on cost and volume (basically impossible—you can't beat Nike or Adidas on cost)

- Compete on premium positioning and maintain high margins (requires much smaller scale and higher prices)

- Rely on venture capital to subsidize growth until you achieve scale where unit economics improve (the Allbirds strategy, which failed)

What Allbirds tried to do was option three, and it doesn't work unless you have an unlimited supply of capital. Once capital dried up, the company was stuck with the reality of options one and two. And Allbirds ended up somewhere between them—too small to compete on cost, too ambitious in its previous strategy to compete on premium positioning.

A profitable sustainable footwear company probably looks like: 5-10 million pairs sold per year, $200-300 million revenue, premium pricing, focused distribution, international presence in 3-5 key markets, and accepting that you'll never be a "billion-dollar unicorn." And you know what? That company might actually make investors money, even though the valuations will be smaller.

Allbirds' market capitalization plummeted from

The Broader Pattern: Direct-to-Consumer Brands and the Venture Capital Bubble

Allbirds isn't alone in this trajectory. This same pattern played out across dozens of venture-backed consumer brands in the 2015-2021 period. Warby Parker, Casper, Glossier, Dollar Shave Club, Away, Bonobos—the list goes on. Almost all of these companies followed the same playbook: build a DTC brand online, raise venture capital, expand aggressively to multiple channels, go public at a premium valuation, realize the unit economics don't work, and then spend the next few years unwinding the bad decisions.

Warby Parker went public at

There's a lesson in all of this for founders and investors: the optimal scale for many consumer brands might be significantly smaller than venture capital's growth-at-any-cost model assumes. A profitable

Allbirds, in unwinding its poor decisions and retreating to a profitable model, is actually doing the right thing. The company should probably be worth

Allbirds in the Context of Tech Culture: What the Shoe Meant

There's a cultural dimension to the Allbirds story that's important to acknowledge. In the mid-2010s, when the company was founded, those shoes became a uniform. If you worked at a Series A startup or a big tech company, you wore Allbirds. They signaled: "I work in tech, I care about sustainability, I'm comfortable prioritizing function over style, and I have enough disposable income to spend $95 on sneakers."

For a specific moment in time, that uniform meant something. It meant you were part of a cohort that believed in creating the future through software and technology. It meant you thought you were on the right side of history. It meant you probably believed that venture capital was the optimal way to fund innovation, and that growth-at-any-cost was a reasonable strategy if the outcome was supposed to be revolutionary.

That moment has passed. The tech industry still exists, but the narrative has fundamentally changed. The optimism of the mid-2010s—that you could disrupt anything with a smartphone app and enough venture funding—has curdled into something more anxious. The recession fears are real. The fears about AI replacing jobs are real. The understanding that growth at any cost can destroy shareholder value and waste capital is real.

Allbirds closing stores in 2025 is a symbol that this particular cultural moment is over. It's not that sustainable footwear is bad. It's that the idea that you could fund any category with infinite venture capital and expect a profitable outcome was always a mistake.

The tech industry is shifting toward founders and companies that are more capital-efficient, more focused on unit economics, and more realistic about growth. The companies that will thrive in the next decade won't be the ones that raised the most money—they'll be the ones that were the most thoughtful about how they spent it.

What Happened to the Allbirds Stores Themselves

When Allbirds announced the closure, the stores in San Francisco and other major cities had maybe 3-4 months to sell through inventory. These weren't fire sales in the traditional sense—the company still wanted to maintain brand premium positioning even as it exited retail. But store closures are dramatic events in commercial real estate, especially in San Francisco where the cost of that square footage is astronomical.

The store closures freed up real estate in valuable downtown locations. The landlords have to find new tenants or accept lower rents. San Francisco's retail landscape has been under pressure since the pandemic anyway, and the Allbirds closure is one more data point showing that mid-range consumer brands are retreating from physical footprints.

The employees working at those stores had to find other jobs. Some probably transferred to the company's customer service or fulfillment operations. Others probably left the company entirely. This is the human cost of venture capital's bad capital allocation decisions—the people who built the stores and worked in them have to suffer the consequences of funding decisions they had no control over.

Allbirds' market cap plummeted from

The Future of Direct-to-Consumer Retail: Lessons from Allbirds

What does the Allbirds story teach us about the future of DTC retail? A few things:

First, e-commerce is still the optimal channel for most DTC brands. If you're spending 10% of revenue on customer acquisition in the digital channels where your brand already lives, why would you open a physical store that costs 15-20% of revenue just to operate? The math doesn't work unless you can clearly articulate how physical stores drive online conversion. Allbirds tried that argument. It didn't stick.

Second, brands need to be honest about their addressable market size from the beginning. Some categories can scale to

Third, the golden period of venture-backed consumer brands might be ending. When capital was cheap and abundant, VCs could fund brands that had no clear path to profitability. Now that capital is scarce and expensive, those brands have to actually make money. That changes everything about how consumer brands get built and funded.

Fourth, being profitable is actually a competitive advantage now. Companies that are generating actual profit can weather economic downturns, can invest in new product categories without external capital, and can make decisions based on long-term thinking rather than the next funding round. For a decade, VCs mocked profitable companies as "slow." That narrative has completely reversed. Now, the companies that look smart are the ones that were disciplined about capital from the beginning.

The Stock Price Story: How Public Markets Price in Reality

Allbirds' stock price has been a fascinating proxy for how public markets price reality versus growth narratives. When the stock IPO'd at $20, the market was pricing in: continuous growth, international expansion, new product categories, and physical retail at scale. That narrative lasted about six months before the market started asking uncomfortable questions.

By 2023, the stock was trading at $1-2. At that price, the company was valued below its annual revenue. That's what happens when the market loses faith entirely. The stock price didn't gradually decline as the company slowly revealed problems—it crashed because the market suddenly realized that the entire growth narrative was built on unsustainable capital burning.

Now that the company is actually pursuing profitability, the question is whether there's any valuation recovery in the stock. In theory, if Allbirds can stabilize at

The Allbirds stock is now a cautionary tale that gets taught in business schools. It's the case study of how venture capital optimism can create markets that don't exist, and how public markets eventually correct for that optimism, sometimes brutally.

Comparing Allbirds to Other Failing DTC Brands

When you look at other DTC brands that went public and struggled, Allbirds is actually a middle-of-the-pack disaster. Some companies had it worse. Dollar Shave Club was acquired by Unilever for $1 billion (which looked great at the time, then looked mediocre when growth slowed). Casper had to reorganize its entire business. Warby Parker spent years trying to prove it could be profitable at scale.

But Allbirds is interesting because the company at least had the discipline to pull back and restructure aggressively. Some DTC brands kept pretending the growth narrative was working even as the losses mounted. Allbirds said: "Okay, we miscalculated on physical retail, let's exit it." That's the right move, even though it came late.

What you're seeing across all these companies is a similar pattern: massive overvaluation based on a growth narrative, followed by disappointing growth and increasing losses, followed by a painful but necessary pivot to profitability. The companies that handle that pivot well might survive. The ones that don't will probably get acquired at a steep discount or just quietly disappear.

E-commerce remains crucial for DTC brands, with profitability now a key competitive advantage. Estimated data based on strategic insights.

The Role of Quarterly Earnings and Public Market Discipline

One of the reasons Allbirds had to make such dramatic changes is that public markets are relentless. Every quarter, the company has to report earnings. Analysts have to ask hard questions. The SEC requires honest financial disclosure. You can't hide problems or pretend the growth narrative is still on track when it clearly isn't.

This is actually one of the underrated arguments for why some companies should probably stay private longer. Before going public, a company can be honest internally about its challenges without having to explain them to the market every quarter. You can make long-term decisions without worrying about quarterly guidance. You can pivot without having to explain that pivot to analysts.

Once you're public, those options disappear. You have to make decisions that either meet analyst expectations or admit that you missed them. For a consumer brand trying to pivot from growth-at-any-cost to profitable operations, that's incredibly constraining. You need to make investments that won't pay off for years, but the market wants to see improvements in the next quarter.

Allbirds handled this reasonably well by being transparent about the pivot. The CEO said: "We're restructuring for profitability." The company took a big hit to the stock price in the short term, but at least investors knew what was happening and could make informed decisions. Some DTC brands kept claiming growth was just around the corner, and that destroyed investor trust even more.

What Stays With Allbirds: The Digital-First Future

Even with all the store closures and operational cutbacks, Allbirds' core strength—its direct-to-consumer e-commerce business—actually works. The company can still sell shoes directly to customers online. It can still maintain customer relationships. It can still innovate on product. The online business is probably actually profitable or close to it.

What doesn't work is the hypothesis that you can add unlimited retail channels on top of a profitable online business and create value. That hypothesis was always flawed. The company should have had the courage to stick with what works from the beginning, rather than spending years and hundreds of millions of dollars proving that adding retail channels destroys value.

Going forward, Allbirds will basically be a pure e-commerce footwear brand with a couple of outlet locations. That's... actually a pretty reasonable business to be. It's not going to be a

The Broader Implications: Capital Efficiency and the Next Decade

What the Allbirds story really illustrates is a wholesale reckoning across the tech and startup world about how capital should be allocated. The 2010-2021 period was characterized by what you might call "capital abundance optimism"—the belief that having enough money could solve almost any problem, that growth was always good, and that profitability could be deferred indefinitely.

That narrative has completely reversed. Now the talk in Silicon Valley is about "capital efficiency," "sustainable growth," and "achieving profitability at scale." It sounds like boring business speak, but it's actually a fundamental shift in how startup economics work.

Companies that are building for capital efficiency from the beginning will be at an advantage over the next decade. That means: understanding unit economics early, focusing on channels that actually work, being ruthless about cutting costs, and building teams that can execute efficiently rather than just hiring to hit growth metrics. The Allbirds of the next decade won't go public at

Allbirds' Remaining Footprint: Four Stores and the Online Business

After the store closures, Allbirds will maintain a minimal physical presence: two outlet locations in the US and two full-price stores in London. The outlet strategy makes sense—those stores serve a purpose in clearing inventory and selling slow-moving stock at better margins than online clearance. The London locations are interesting; the company might be betting that the UK is a stronger market or that international presence is important to the brand narrative.

But basically, Allbirds is retreating entirely to the channel it should have never left: direct-to-consumer e-commerce. The company will sell online, maintain an email list, run social media marketing, and probably do some limited wholesale partnerships with retailers that can sell their products in volume.

This is a much smaller version of Allbirds than the IPO version, but it's also much more defensible. The company is no longer trying to be all things to all people. It's accepting that it's a online footwear brand with a specific customer and a specific market. That's a realistic foundation for a profitable business.

The Future of Allbirds: Can It Survive in This New Form?

The honest answer is: probably yes, but it will take time. The company has to prove that it can generate consistent positive cash flow. It has to show that its online customer acquisition is sustainable. It has to prove that customers still care about the sustainability angle enough to justify the premium pricing.

If Allbirds can do those things for 2-3 years, the stock might recover. Maybe not to

But there's also a significant risk that the brand is damaged. Allbirds means something different now. Instead of "cool sustainable brand," it means "failed unicorn that went public too soon." That narrative is hard to escape. The company might have to spend years rebuilding brand credibility, and it's not clear if the market will give it that time.

In some ways, the best-case scenario for Allbirds shareholders might be if a larger footwear company acquires it at a reasonable valuation. Nike, Adidas, or another major player might see value in the online business, the customer base, and the sustainability positioning. An acquisition at

FAQ

Why did Allbirds decide to close its physical retail stores?

Allbirds closed its physical stores because the company needed to achieve profitability to remain viable as a public company. The brick-and-mortar retail locations were generating losses when accounting for rent, labor, and operating costs, while the company's direct-to-consumer e-commerce business was the profitable core. After going public in 2021 and facing significant losses, the new CEO made the strategic decision to exit unprofitable channels and focus entirely on the online business model that originally made Allbirds successful. This decision, while painful in the short term, aligned the company's cost structure with its actual revenue-generating capacity.

What does Allbirds' closure mean for direct-to-consumer retail strategies?

The Allbirds store closures signal that the venture capital playbook of "expand into every channel regardless of profitability" no longer works in a capital-constrained environment. Direct-to-consumer brands that built their core business online (like Allbirds did) destroy value by opening expensive physical stores that cannibalize online sales without adding proportional revenue. Going forward, successful DTC brands will be more selective about retail presence, focus on channels with proven unit economics, and maintain leaner cost structures. The lesson is that pure e-commerce, despite seeming less glamorous, is often the optimal strategy for DTC brands seeking profitability.

How much shareholder value did Allbirds destroy since going public?

Allbirds' market capitalization has collapsed from approximately

Could Allbirds have avoided this disaster by staying private longer?

Very likely. If Allbirds had remained private and focused on building sustainable unit economics before going public, the company could have IPO'd at a more reasonable $1-2 billion valuation and likely generated positive returns for investors. The core product was never broken, and the e-commerce business can be profitable. The problem was that the venture capital incentive structure pushed for growth-at-any-cost, which led to overvaluation on IPO. A private company can make long-term decisions without quarterly earnings pressure. A public company faced with declining stock prices and analyst skepticism has to make dramatic changes quickly, which is what happened with Allbirds. Staying private longer would have allowed the company to prove profitability before entering the public markets.

What percentage of Allbirds' revenue came from physical retail stores?

While exact percentages vary by period, physical retail represented roughly 15-25% of Allbirds' revenue at its peak retail footprint, but consumed significantly more than that percentage in operating costs due to rent, labor, and inventory management expenses. The stores operated at negative unit economics when factoring in customer acquisition costs and contribution margin. This mismatch between revenue contribution and cost contribution is what ultimately made the store closures inevitable. The e-commerce channel, which likely represents 70-80% of revenue, was the only consistently profitable business line.

Can Allbirds recover and become a successful company again?

Allbirds has a reasonable chance of becoming a profitable mid-size footwear company, but recovery to meaningful shareholder value will take years. If the company can stabilize at

What is Allbirds' path to profitability going forward?

Allbirds' profitability strategy centers on: (1) eliminating unprofitable retail locations to reduce fixed costs significantly, (2) focusing marketing spend on high-ROI digital channels like email and social media where customer acquisition costs can be controlled, (3) streamlining the product line to focus on best-sellers rather than experimental categories, (4) optimizing international presence in markets where the brand has genuine demand, and (5) leveraging the direct-to-consumer customer relationships to build brand loyalty and reduce reliance on paid acquisition. The company also maintains outlet locations for inventory clearance at better margins than online discounting. This leaner operating model, combined with the existing e-commerce infrastructure and customer base, should allow Allbirds to achieve operating profitability if execution is solid.

How does Allbirds' situation compare to other DTC brands that went public?

Allbirds' trajectory mirrors that of many venture-backed DTC brands: rapid growth, venture funding at premium valuations, IPO during a favorable market window, followed by disappointing growth and painful restructuring. Warby Parker, Casper, and Glossier all followed similar patterns. However, Allbirds is notable for making relatively aggressive cuts to restore profitability quickly, rather than limping along while trying to maintain growth narratives. Some DTC companies had it worse (Casper needed rescue financing), while others had it better (Warby Parker maintained stronger unit economics despite the valuation drop). The common thread across all these companies is that the venture capital growth thesis didn't survive contact with public market discipline and capital constraints.

Conclusion: What Allbirds Represents for the Next Decade

Allbirds closing its San Francisco stores in early 2025 isn't a tragedy. It's a correction. It's a company finally admitting that the strategy it pursued under venture capital guidance—expand into every channel, worry about profitability later—doesn't work in a world where capital is scarce and investors demand actual returns.

The broader story here is about a fundamental reckoning with how venture capital has allocated capital over the past fifteen years. An enormous amount of money went to companies pursuing growth narratives that couldn't survive contact with reality. Some of those companies found ways to actually execute and build enduring businesses. Most of them didn't. And the ones that went public before solving their profitability problem are now experiencing a brutal but deserved reckoning with public markets.

Allbirds' shoes are still good. The company is still viable. But the company that goes forward is a much smaller, more focused version of what the venture capital playbook imagined it could become. And honestly, that's probably the version that should have been built in the first place.

The next decade of startup growth will be characterized by founders and investors who've learned the lesson that Allbirds is teaching: capital efficiency matters more than growth-at-any-cost, profitability is actually a competitive advantage, and the companies that become worth something are the ones that make disciplined decisions from day one rather than betting everything on raising the next round at a higher valuation.

For anyone wearing Allbirds shoes right now, you've got a product that works. The company that makes it is smaller, leaner, and actually more likely to survive long-term than it was when it was a public company burning money in pursuit of growth metrics. That's not a failure. That's actually a win, even if it doesn't feel like one.

The real lesson is for the next generation of founders: the venture capital treadmill is attractive, but it's not inevitable. Building something profitable and sustainable might result in a smaller absolute company, but it actually results in better outcomes for customers, employees, and investors. Allbirds should have learned that lesson before going public. The startups that learn it now, before the capital crunch forces them to, will be the ones that thrive.

Key Takeaways

- Allbirds is closing all physical retail locations by February 2025, retreating to a profitable e-commerce-only model after destroying 99.2% of shareholder value since IPO

- The company's collapse reflects a fundamental failure of the venture capital playbook: growth-at-any-cost economics don't survive public market discipline

- Physical retail was the wrong channel for an e-commerce-native brand, consuming 30%+ of operating costs while generating only 20% of revenue

- Allbirds' trajectory mirrors dozens of DTC brands that were massively overvalued based on growth narratives unsustainable in the real world

- The broader lesson for the next decade: capital efficiency and profitability are now competitive advantages, reversing the venture capital narrative of the 2010-2021 period

Related Articles

- TechCrunch Founder Summit 2026: The Ultimate Guide to Scaling Your Startup [2026]

- Snap's AR Glasses Spinoff: What Specs Inc Means for the Future [2025]

- Redwood Materials $425M Series E: Google's Bet on AI Energy Storage [2025]

- Why Amazon Shut Down Go and Fresh Stores [2025]

- Northwood Space Lands 50M Space Force Contract [2026]

- AI Chip Startups Hit $4B Valuations: Inside the Hardware Revolution [2025]

![Why Allbirds Closing Stores Signals Tech Culture's Biggest Shift [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-allbirds-closing-stores-signals-tech-culture-s-biggest-s/image-1-1769620218294.jpg)