The $1 Billion Exit Nobody Wanted to Win

It's the kind of deal that makes headlines for all the wrong reasons. Divvy Homes, a rent-to-own startup that had once commanded a

Except the founders got nothing. The employees got nothing. Even most of the venture investors got nothing.

In January 2025, CEO Adena Hefets sent a letter to shareholders that landed like a punch to the gut. After repaying outstanding debt obligations, paying transaction costs, and honoring liquidation preferences for preferred shareholders, the company's common shareholders and founders' preferred stock received zero proceeds. One billion dollars of exit value. Zero for the people who spent years building it.

This isn't some cautionary tale buried in startup Twitter threads anymore. It's become the most important capital structure lesson that B2B founders need to understand. And it has nothing to do with whether Divvy's model was sound or whether they made smart product decisions. It's purely about the math of how money gets distributed when a company sells.

If you're a founder who's been casually thinking about venture debt as "free money" or "non-dilutive capital," this is the moment to stop and really understand what you're actually taking on. Because debt isn't free. It's not non-dilutive to your outcomes. And under the wrong circumstances, it can be the difference between a life-changing exit and walking away with nothing after years of sacrifice.

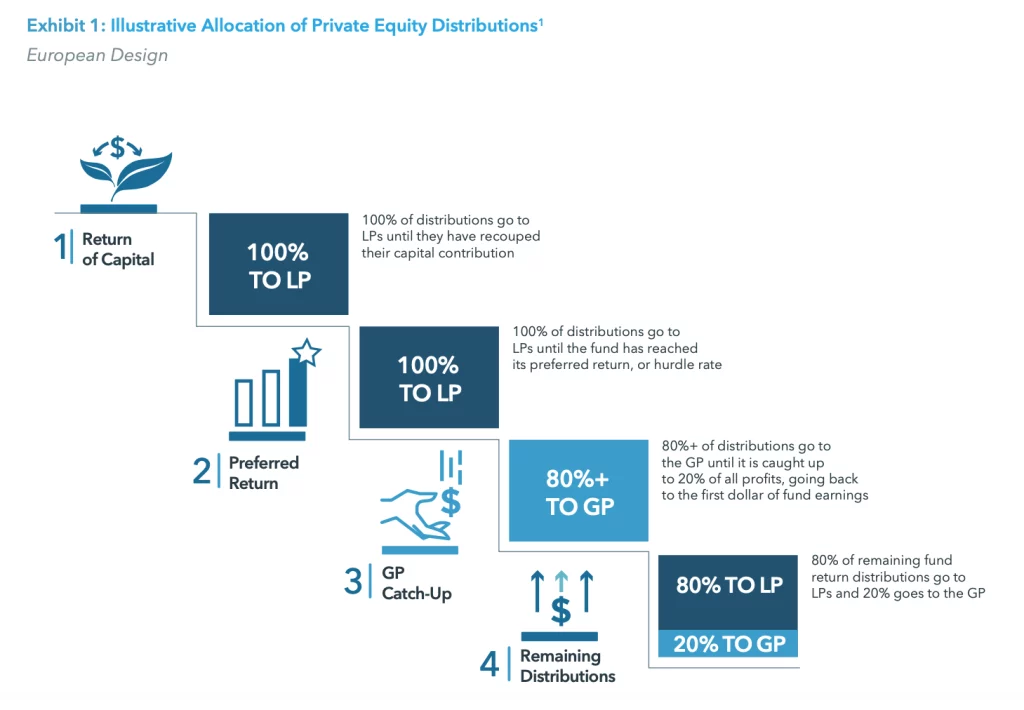

Understanding the Waterfall: How Exit Proceeds Get Distributed

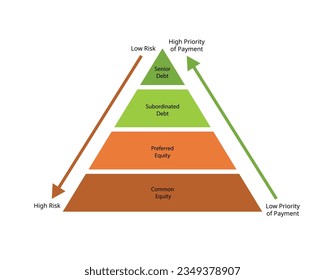

Here's the brutal truth that most founders don't fully grasp until it's too late: when your startup exits, the money doesn't distribute equally. There's a strict, legally binding order of operations. And you need to understand exactly where you sit in that line.

Think of the exit proceeds as water flowing through a series of gates. Each gate has a claim on the money, and the gates open in a specific order. If the water runs out before it reaches your gate, you get nothing.

Gate One: Debt Holders

Debt is senior to everything else. Full stop. When Divvy sold, the first $735 million in proceeds went to repaying debt obligations. The debt holders lent money with a contract that says they get paid back first, in full, before anyone else gets a penny. They don't own equity. They don't care about the company's mission or how many families you helped become homeowners. They lent you money at a specific interest rate, and they want their principal back plus the agreed-upon interest.

This is the single most important concept to internalize: debt has absolute priority. In liquidations or sales, debt holders have what's called "senior claim" status. They're not hoping for a good outcome. They have a contractual right to payment before preferred shareholders, common shareholders, or anyone else.

Gate Two: Transaction Costs

Exits are expensive. Lawyers, investment bankers, accountants, advisors—everyone wants their piece. For a

Gate Three: Preferred Shareholders and Liquidation Preferences

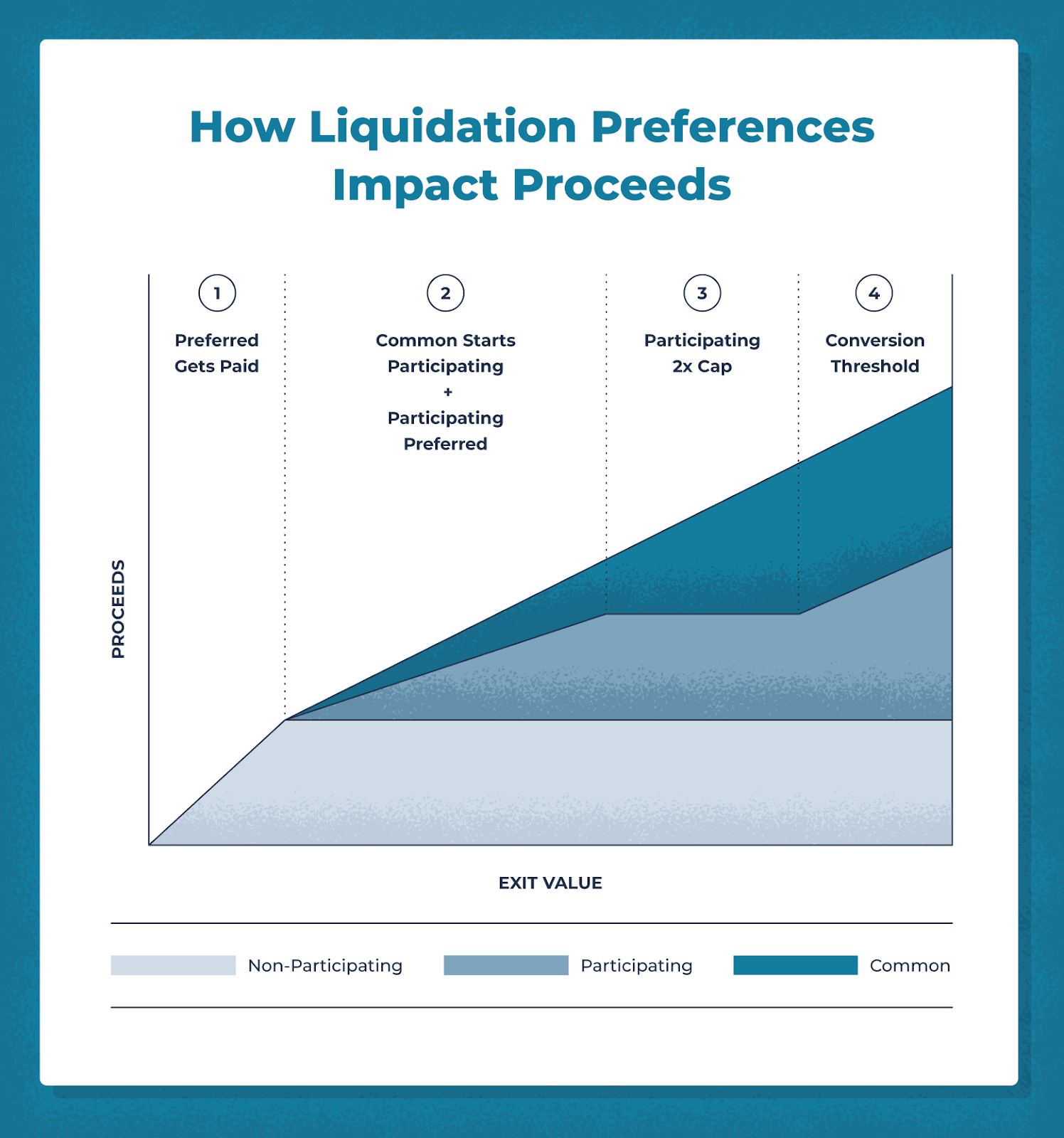

This is where it gets complicated and where founders often get blindsided. Every time you raised a round of venture funding, your investors negotiated liquidation preferences. These preferences determine how much of their investment needs to come back to them before money flows to common shareholders.

In Divvy's case, the company had raised multiple rounds of Series A, B, C, and D funding. Each of these preferred investors had what's called a "1x liquidation preference," meaning they get their invested capital back before common shareholders see anything. Some deals involve 2x or even 3x liquidation preferences, which means the investor gets two or three times their invested amount back before common shareholders get paid.

Here's the math: If Series D raised

Gate Four: Common Shareholders and Founders

This is the back of the line. Your common shares, your founder pool, your early employees who took equity compensation instead of high salaries—everyone is sitting here, hoping the money doesn't run out at Gate Three.

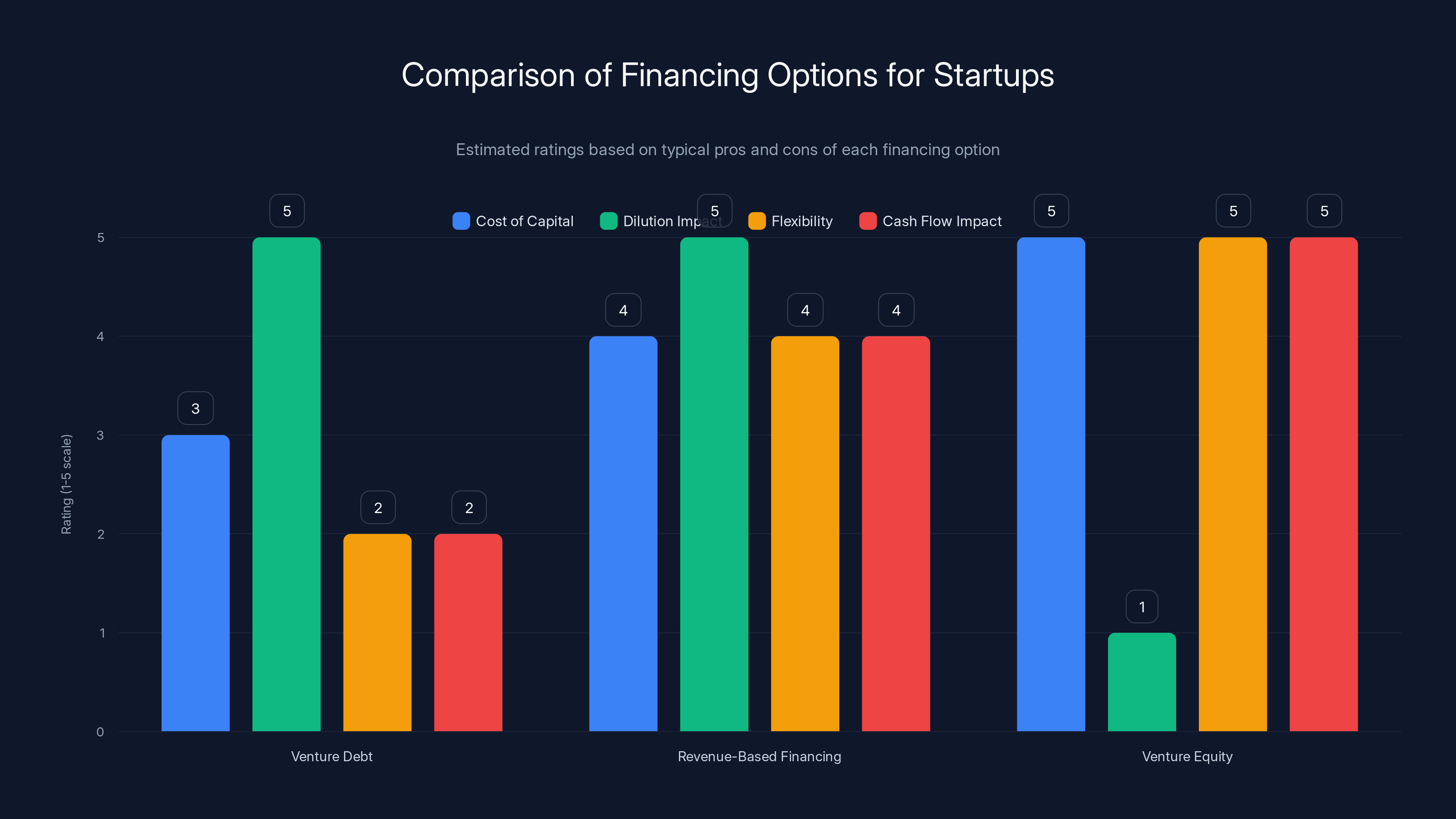

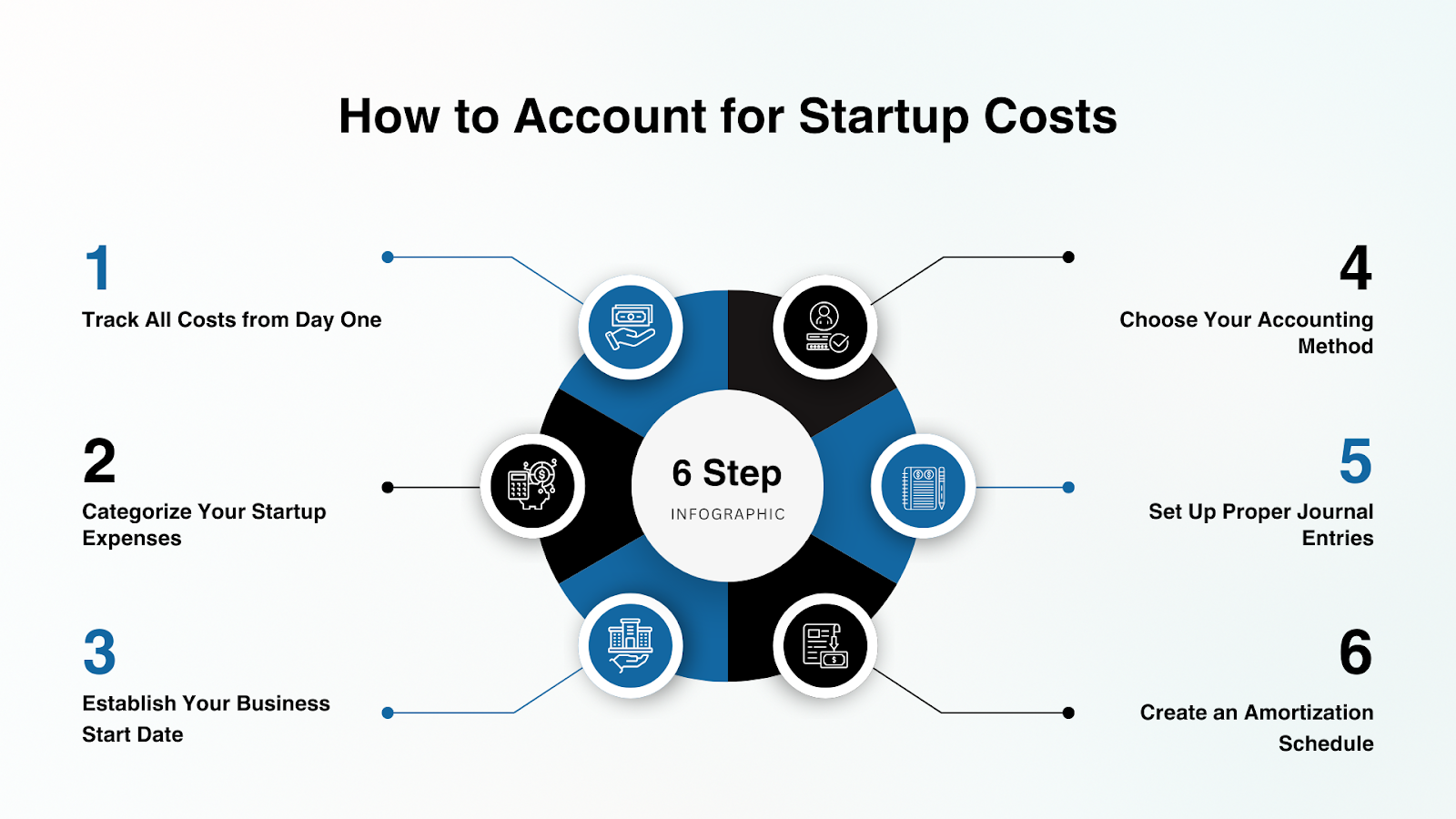

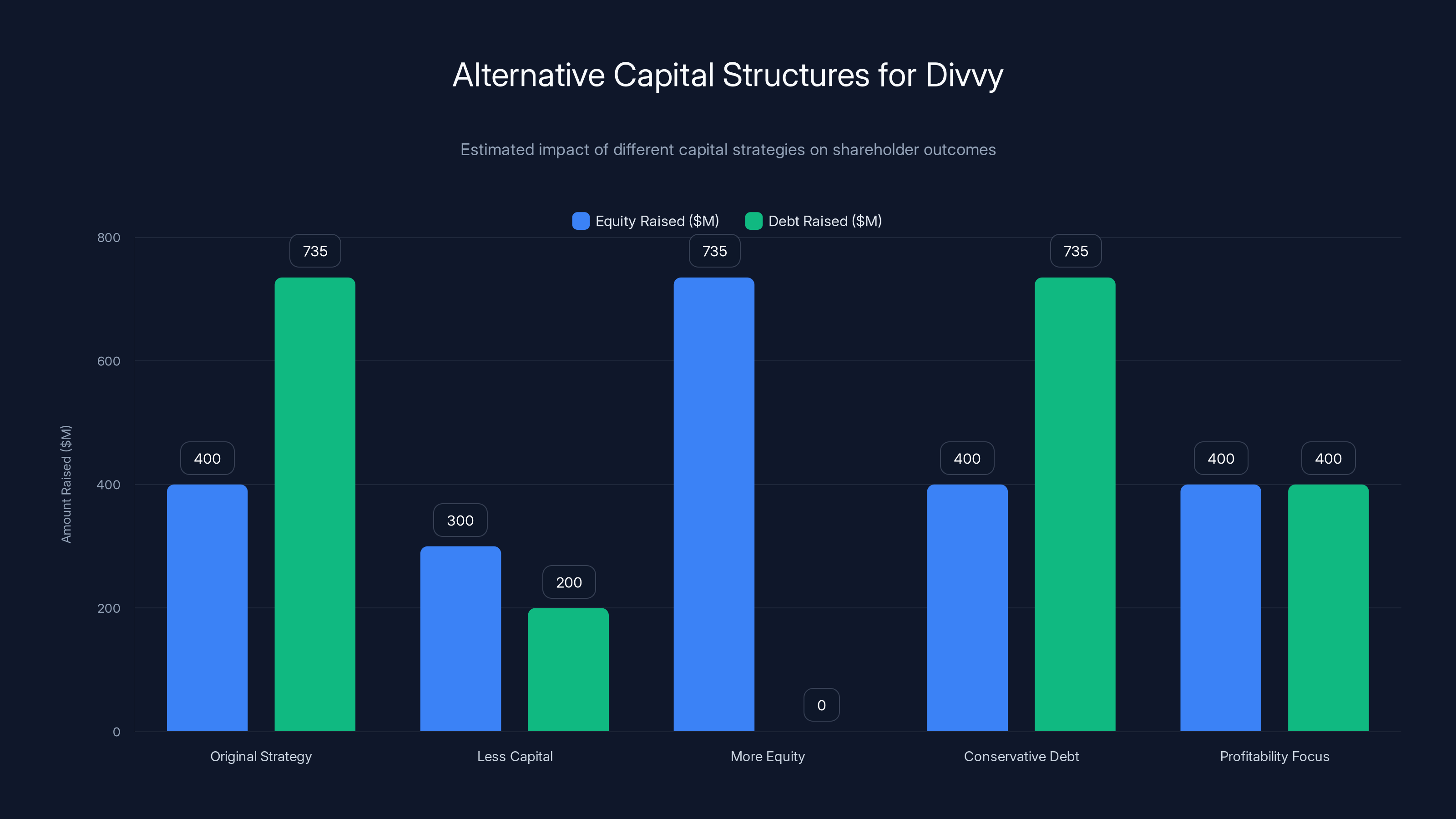

Estimated data shows that Venture Equity offers the most flexibility and least cash flow impact, but has the highest dilution. Revenue-Based Financing balances flexibility and cost, while Venture Debt has the lowest cost but highest cash flow impact.

The Divvy Homes Numbers: A Detailed Breakdown

Let's walk through the actual Divvy math, because understanding this specifically will crystallize why this matters.

The Starting Position:

Divvy had raised over

Then in October 2021, Divvy took on approximately $735 million in debt financing. This was meant to scale home acquisitions, to grow faster, to capture more market share before competitors could. Debt seemed like the smart move at the time—it avoided further dilution, it was cheaper than equity (interest rates were lower then), and the model seemed fundamentally sound.

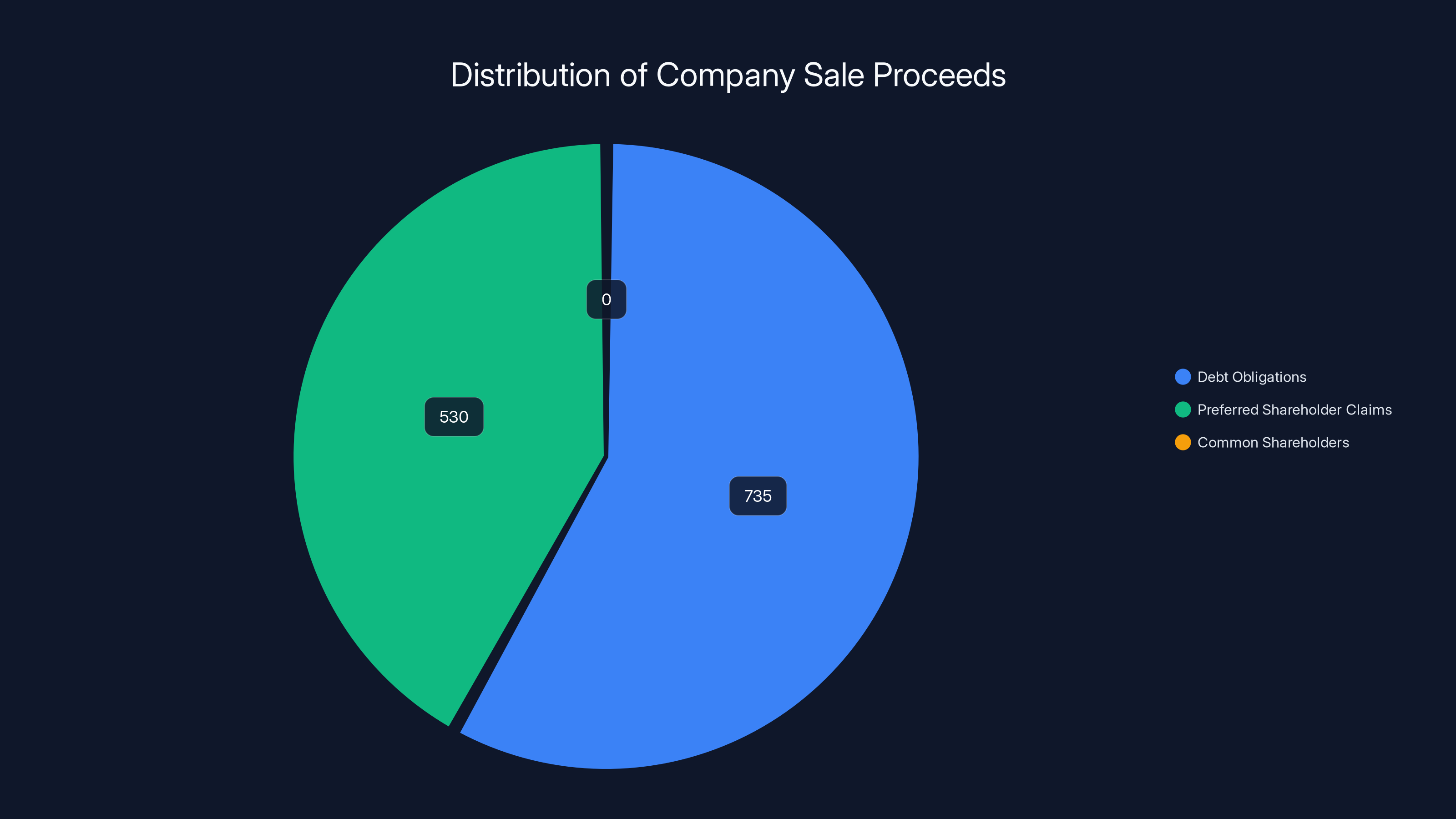

The Exit Calculation:

Sale price: $1,000,000,000

Minus debt repayment: $735,000,000

Remaining: $265,000,000

Minus transaction costs (conservatively estimated):

Remaining after debt and costs:

Now here's where it gets tight. The preferred shareholders' liquidation preferences need to be satisfied. If we conservatively estimate that preferred investors had roughly

But there's only $225-240 million left after debt and costs.

The money ran out before it got to the founders.

This is the structural problem. The debt was senior to all equity claims. The preferred investors had liquidation preferences that were contractually binding. The math is remorseless.

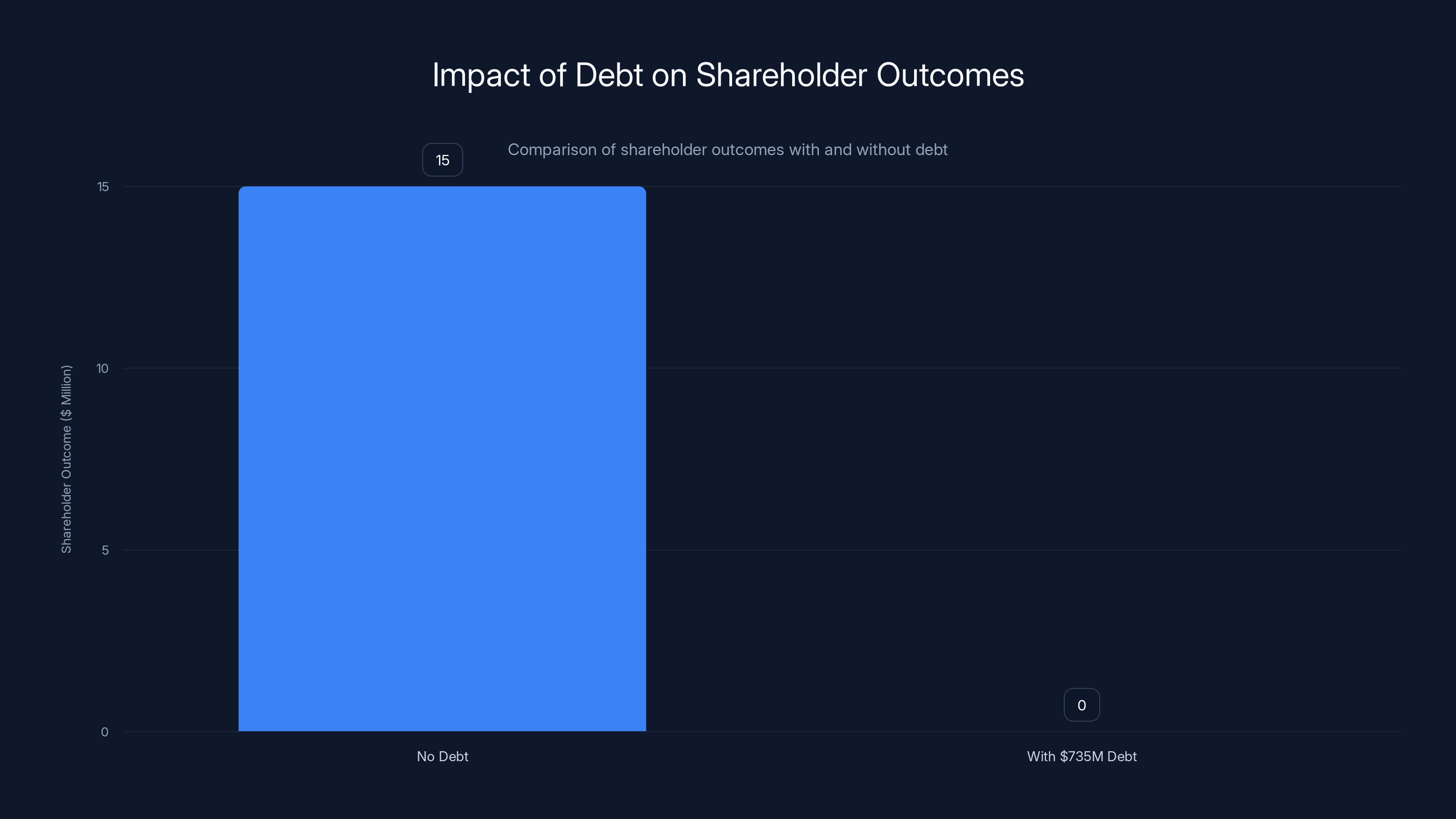

Why Debt Isn't "Non-Dilutive" (The Real Story)

Every founder hears the pitch from venture debt providers: "Debt is non-dilutive. You keep your ownership percentage on the cap table. You're not giving up equity. It's basically free money."

Technically, that's accurate. Debt doesn't change your percentage ownership of the company. If you owned 5% before the debt, you still own 5% after.

But here's what debt providers don't emphasize clearly enough: debt doesn't dilute your ownership—it dilutes your outcome.

Owning 5% of a

Let's model this:

Scenario One: No Debt

Company sells for

Scenario Two: With $735 Million in Debt

Company sells for

Your ownership percentage stayed the same. Your actual economic outcome dropped from $15 million to zero.

That's what "non-dilutive" really means. Your cap table dilution might be zero, but your outcome dilution is catastrophic.

There's another insidious aspect to this: when you take on debt, you're also taking on obligations that constrain your strategic options. Debt covenants often include clauses about minimum cash reserves, maximum debt-to-revenue ratios, limitations on dividend payments, and restrictions on taking on additional debt. These covenants can prevent you from making strategic decisions—like aggressive pricing moves, or international expansion, or investments in new product areas—that might have allowed the company to grow faster and reach a higher exit valuation.

Divvy's case is instructive here. When interest rates surged in 2022, their unit economics deteriorated. The debt became an anchor, a fixed obligation that couldn't scale with the business. The company had to cut costs (three rounds of layoffs), had to pause acquisitions, had to basically shrink. Those weren't decisions made because the model was broken—they were made because the debt burden made growth untenable.

In a $1 billion company sale, debt obligations and preferred shareholder claims consume all proceeds, leaving nothing for common shareholders. Estimated data based on typical scenarios.

The Capital Structure Problem: Why Divvy's Stack Was Unstable

When Divvy took on $735 million in debt, they created a capital structure that was mathematically fragile. Let's understand why.

Divvy's model was real-estate intensive. They bought homes, rented them, and held them until the tenant-buyer could purchase. That means enormous amounts of capital tied up in property. The more homes you buy, the more capital you need.

Venture capital raised to date: $400+ million

Debt taken on: $735 million

Total capital deployed: $1.1+ billion

For context, that's a remarkable amount of capital for a company that was five years old at the time. Most SaaS companies raise $100-200 million total before exiting. Divvy was in an asset-intensive business, so more capital made sense. But the mix of capital mattered enormously.

The problem was this: most of that

What was missing was enough equity capital that was truly non-dilutive to the founders—capital that wouldn't have senior claims in a liquidation.

Here's the capital structure stability formula:

For Divvy:

At 73.5%, they were more than double the safe threshold. The debt was too large relative to the exit valuation. When the actual exit came in at

This is the distinction between founders who walk away from exits with life-changing proceeds and founders who walk away with nothing: the ratio of debt to expected exit value.

If Divvy had raised that

Instead, they optimized for keeping ownership percentage (via debt) and ended up with ownership of nothing.

The Role of Liquidation Preferences: The Hidden Killer

Liquidation preferences are often the most misunderstood part of a cap table, and they're often what turns a reasonable exit into a founder-destroying exit.

Here's how they work: When an investor buys preferred stock in a Series A, they're typically negotiating for what's called a "1x non-participating preferred." This means:

1x = They get

Non-participating = If the company performs well and there's plenty of money to go around, they don't get special extra rights. They just participate in distributions like everyone else.

Sounds reasonable, right? And in good exits, it is.

But in flat or down exits, this becomes a problem.

Let's say your Series A invested

Now the company sells for

Series A gets their

Series B invested

Series C invested

Series D invested

Common shareholders (you, the founder, and early employees) get nothing.

The liquidation preferences weren't designed to punish founders—they were designed to protect investors from downside risk. But the math is relentless. If the exit valuation is close to or below the total capital raised, preferred investors can capture all or most of the exit proceeds via their liquidation preferences.

In Divvy's case, the series of liquidation preferences stacked on top of each other, and when the debt claim was added on top, it created a perfect storm where nothing was left for common shareholders.

There are variations on this. Some investors take "participating preferred," which means they get their liquidation preference, and then they also participate in any remaining proceeds on a pro-rata basis. Other investors might accept lower liquidation preferences (like 0.5x) in exchange for other rights.

But the standard deal structure—1x non-participating preferred—is what dominates venture capital, and it's what created Divvy's problem.

Interest Rate Changes and Why Timing Matters Desperately

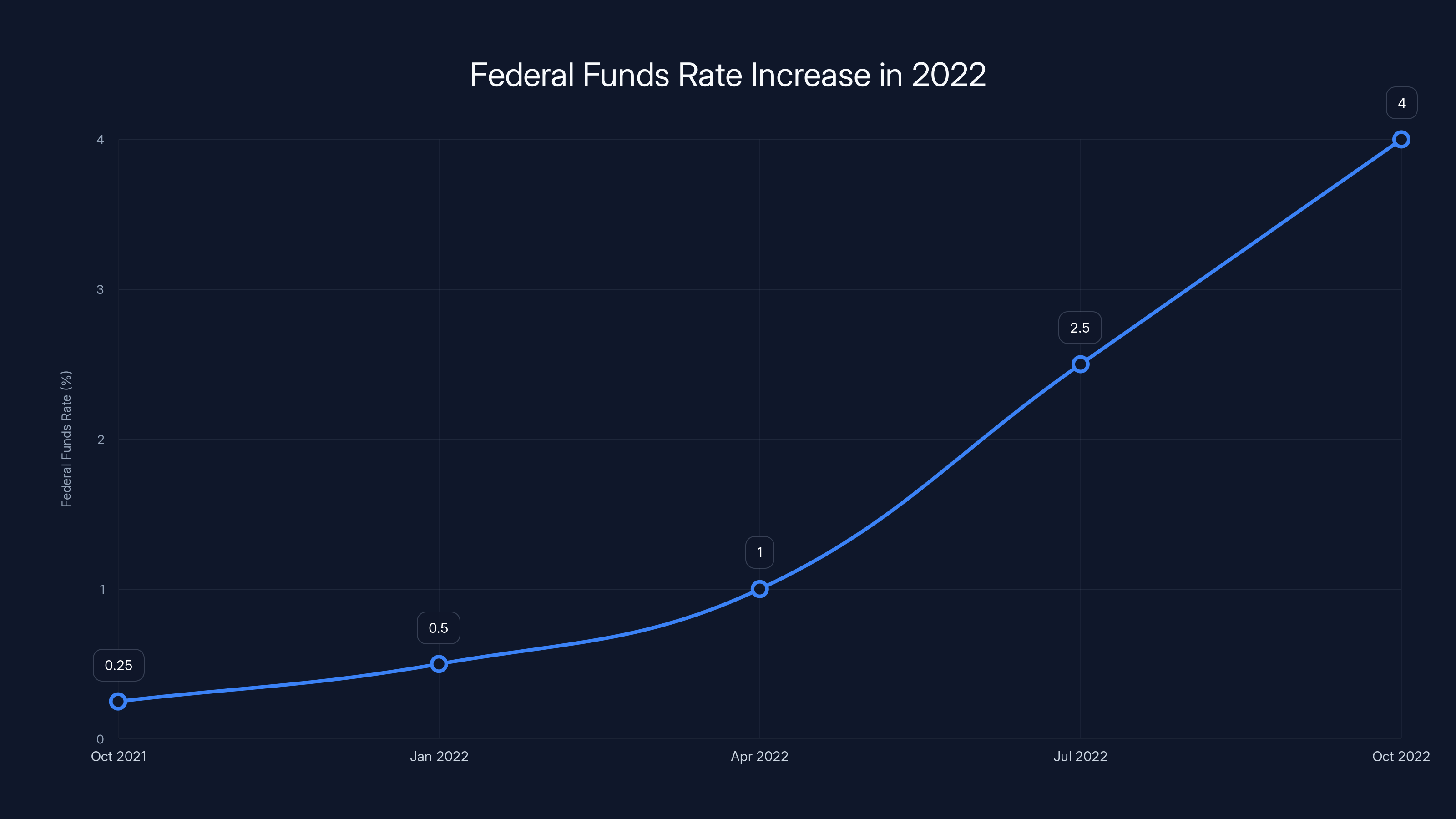

Divvy took on $735 million in debt in October 2021. At that time, interest rates were historically low. The Federal Reserve's policy rate was still near zero. Borrowing money was cheap.

Then 2022 happened.

The Federal Reserve raised interest rates aggressively, moving the federal funds rate from near-zero to over 4% by mid-2022. This had a cascading effect: debt servicing costs rose. Refinancing became more expensive. Capital became scarcer.

For Divvy, this was devastating because their model was fundamentally dependent on cheap capital. They needed to continuously deploy capital into buying homes. Their profit margins were thin—the value came from helping thousands of families become homeowners and from the long-term appreciation of the home portfolio. Short-term unit economics were negative. The company was effectively betting that homes would appreciate, that defaults would be low, and that capital would remain cheap enough to fund continued growth.

When interest rates surged, that bet exploded.

The company's cost of capital went up while their unit economics stayed the same or got worse. They had to pause new acquisitions. They had to cut costs. They couldn't refinance the debt at better rates. They were stuck.

This is an often-overlooked risk of debt: interest rate sensitivity. If your debt has variable interest rates or if you need to refinance frequently, a sharp rise in rates can destroy unit economics that seemed sound when you took on the debt.

Fixed-rate debt is better than variable, but fixed-rate debt is typically more expensive (the lender charges a premium for taking on the interest rate risk). It's a trade-off.

Divvy's case shows what happens when you take on a massive amount of debt right before interest rates rise. The debt that seemed smart in October 2021 became a millstone by late 2022.

The lesson for B2B founders: if you're considering venture debt, pay close attention to the interest rate environment. If rates are already historically low and the Fed is signaling rate increases, taking on debt is risky. If rates are falling, debt looks more attractive. The timing of when you take on debt relative to the broader interest rate cycle matters enormously.

Estimated data shows that while ownership percentage remains unchanged, the economic outcome for shareholders can drastically decrease from

Revenue-Based Financing vs. Venture Debt vs. Equity: The Comparison

When founders are looking for growth capital without dilution, they typically consider three paths:

Venture Debt

Venture debt is a loan. You borrow money, you pay it back with interest, you owe it regardless of whether your company succeeds or fails. It's senior to all equity claims. Interest rates typically range from 8-15% depending on market conditions. There are often covenants that constrain your strategic options.

Pros: Lower cost of capital than equity. Doesn't dilute ownership percentage.

Cons: Fixed obligation that can stress cash flow. Senior claim in liquidations. Interest rate risk. Covenants can restrict strategy.

Revenue-Based Financing (RBF)

RBF is a hybrid between debt and equity. You borrow money, but instead of paying back a fixed amount, you pay back a percentage of monthly revenue (typically 3-8%) until you've repaid the borrowed amount plus a return (usually 1.3-1.5x the borrowed amount).

Pros: Payment scales with revenue, so you don't have to maintain fixed obligations. Doesn't dilute equity (though it does reduce available cash). Less restrictive than debt covenants.

Cons: Can become expensive if your revenue grows quickly (you're paying a percentage of a larger number). Still has priority over equity in some scenarios. Reduces cash available for operations.

Venture Equity

You raise a new round of venture capital. This dilutes your ownership percentage, but new capital comes without repayment obligations.

Pros: No repayment obligation. Aligns investor incentives with founders'. Investors become partners in the business.

Cons: Dilutes founder ownership. Brings new board members and investor preferences. Liquidation preferences can be problematic if exit is lower than expected.

The Choice in Divvy's Context

If Divvy had raised that

That's the fundamental trade-off: dilution in ownership percentage now, in exchange for avoiding existential risk to outcome later.

For B2B founders in particular, the best time to raise equity is when your company is demonstrating strong growth and has proven unit economics. At that point, you can negotiate better terms and give up less dilution. Rushing to raise debt to avoid dilution is often a false economy.

The Founder Equity Problem: Why Your Shares Might Be Worthless

Here's a detail that doesn't always get emphasized enough: in Divvy's case, the founders themselves took a hit, but so did thousands of employees.

Early employees at startups are typically compensated partially in equity. A junior engineer who joined Divvy in 2016 might have gotten 0.1% of the company as part of their package. After six years of work, that 0.1% stake was worth nothing.

This is why the "equity compensation" narrative in startups is complicated. Yes, equity can be life-changing. Your 0.1% stake could theoretically be worth $1 million in a normal billion-dollar exit. But if the cap table is structured badly, or if debt is taken on, that 0.1% can be worth exactly zero.

Employees at Divvy weren't dumb. They knew startups were risky. They accepted equity as part of their package because the company seemed solid and because the mission (helping families become homeowners) was compelling. But they didn't have insight into the debt situation. They didn't understand the liquidation preference waterfall. They just thought they were building something that might succeed.

For founders, this is a moral issue, not just a financial one. You're asking talented people to take below-market salaries in exchange for equity. That's a fair trade if the company succeeds or has a decent exit. But if your capital structure is set up such that a successful exit (a $1 billion sale is objectively successful) results in no proceeds for the people who did the work, you've betrayed that implicit compact.

This is one reason why founder-friendly capital structures matter. If you're going to ask your team to take equity risk, you need to structure that equity in a way where a good outcome actually pays off for them.

The Model Problem: Was Divvy's Business Actually Broken?

It's important to note: the fundamental problem with Divvy wasn't the business model. It was the capital structure.

Rent-to-own models are viable. Divvy helped thousands of families become homeowners. The company was operating, collecting rent, managing a portfolio of homes. It wasn't insolvent because the model was broken.

But the company had to shrink because the debt load was unsustainable at current interest rates. By 2023, they'd paused new home acquisitions. They were managing the existing portfolio and collecting rent, but they couldn't grow.

Brookfield Properties saw value in this. They wanted to acquire the company, the portfolio of homes, the tenant relationships, and the platform. Brookfield is a real estate company—they can manage residential portfolios at massive scale. For them, a $1 billion acquisition was a reasonable entry into the rent-to-own market.

But that valuation—$1 billion—wasn't "the company is worthless." It was "the company is worth something, but that something is less than the obligations we owe to debt holders and preferred shareholders."

This is a critical distinction. A company can have real value and still result in zero proceeds to common shareholders if the capital structure is mismatched to the company's growth trajectory.

The Federal Reserve increased the federal funds rate from near-zero to over 4% in 2022, significantly raising borrowing costs and impacting companies like Divvy that relied on cheap capital. Estimated data.

When Does Venture Debt Actually Make Sense?

Let's be clear: venture debt isn't inherently evil. It can be the right tool in the right circumstances.

Scenario 1: You're Series B/C with Proven Unit Economics and Strong Growth

You've found product-market fit. You're growing 100%+ YoY. Unit economics are positive. Your S-curve suggests you might reach

Scenario 2: You Need Bridge Capital Between Rounds

You're closing Series B in Q2. You need capital in Q1. Rather than waiting, you raise $5 million in venture debt, agreeing to convert it to equity in the Series B at the same terms. This is clean, simple, and solves the timing problem.

Scenario 3: You Have Debt-Like Cashflows But Need to Optimize Capital Allocation

You're a SaaS company doing

What Doesn't Make Sense

Taking on debt when:

- Your unit economics are negative or unproven

- The debt exceeds 30% of your expected exit valuation

- The debt exceeds 25-30% of your annual revenue

- Interest rates are rising and you have variable-rate debt

- Your growth is slowing and capital-intensive

- You don't have a clear path to profitability or a clear exit scenario

Divvy hit several of these criteria: They took on $735 million in debt while unit economics were still being proven (rent-to-own is complex and depends on defaults, appreciation, etc.). The debt exceeded 70% of their eventual exit valuation. Interest rates rose. The model proved capital-intensive.

The Preferred Stock Waterfall: How Later Rounds Protect Earlier Investors

There's another layer to understand: how and why liquidation preferences stack.

In a typical venture capital progression, a company raises money at increasing valuations:

Series A:

Series B:

Series C:

Series D:

Each investor negotiates for 1x liquidation preference. This protects them if the company doesn't grow as expected.

But here's the mathematical reality: by the time you reach Series D, your earlier investors have already had multiple opportunities to make money through secondary sales, dividends, or earlier exits. The liquidation preference is their downside protection.

However, in a flat or down exit, those liquidation preferences stack in a way that can wipe out common shareholders entirely.

Let's model Divvy:

Series A:

With 1x liquidation preferences, these investors need $530M back before common shareholders see a dime.

Exit proceeds:

But

The problem is that as companies raise more and more capital, the liquidation preference obligations compound. If Divvy had raised

But here's the harsh reality: VCs don't structure deals that way. They invest what they think the company needs and what makes sense for their fund size. They don't optimize for founder outcomes in down scenarios—they optimize for their own downside protection.

This is why founders need to pay close attention to the capital structure and push back on excessive preferred capital. Every dollar of preferred capital raised is a claim against future exit proceeds. More capital sounds good until it doesn't.

Real-World Implications for B2B Founders Today

The Divvy situation happened. It's not theoretical. And it's relevant to B2B founders for several specific reasons.

First, if you're raising capital in 2024-2025, the venture capital environment is more disciplined than it was in 2020-2021. VCs are being pickier about which companies they fund and at what valuations. This might seem bad (harder to raise money), but it actually protects you from overfunding. If you raise

Second, if you've been thinking about venture debt as "free money," Divvy is a reminder that it's not. It's cheap money, but it has a cost. That cost is the risk that in a decent-but-not-spectacular exit, the debt consumes most of the value.

Third, if you're negotiating with VCs now, push back on aggressive liquidation preferences. Most VCs default to 1x non-participating, but some will accept 1x non-participating with a cap (only applies up to a certain exit valuation) or even 0.5x. The negotiation is possible, especially if you have multiple term sheets.

Fourth, be mindful of your capital efficiency. Divvy's model was inherently capital-intensive. But that doesn't mean every company with a capital-intensive model needs to raise $400 million+ before exiting. Some companies are better off being more capital-efficient, growing more slowly, and raising less total capital.

Fifth, think about the timing of debt relative to your trajectory. If you're in the early stages of growth, venture debt is risky because you don't have a clear exit scenario. If you're past product-market fit with strong unit economics and clear scaling, venture debt is less risky.

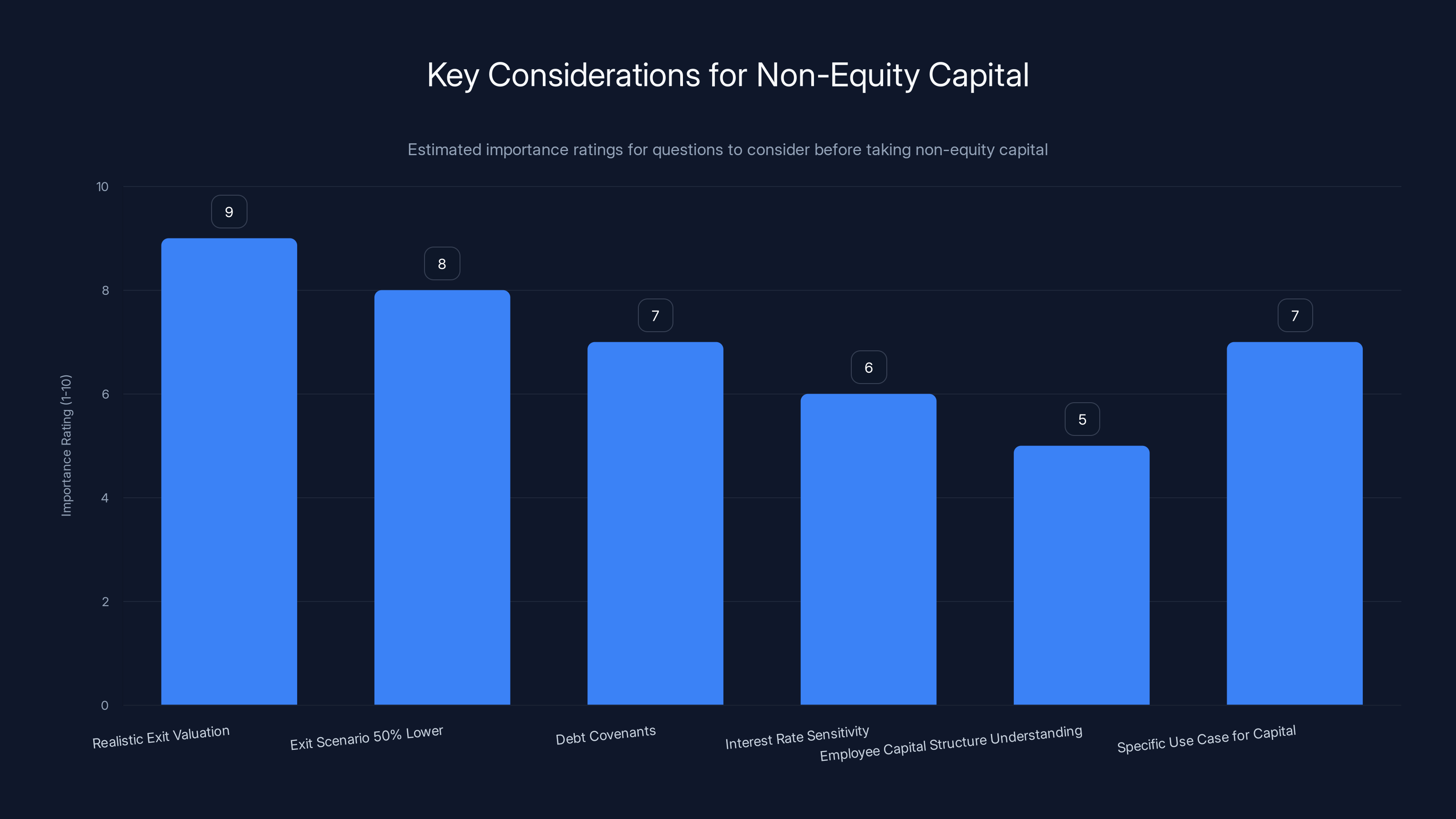

Understanding realistic exit valuations and potential lower exit scenarios are rated as the most important considerations when evaluating non-equity capital options. Estimated data.

The Broader Pattern: Other Companies With Similar Structures

Divvy's situation might seem unique, but it's not. The pattern of a high-valuation company taking on significant debt and then ending up with a decent-exit-but-no-founder-proceeds is becoming more common.

The difference is that Divvy is a case study where the company actually exited. Many companies with similar capital structures are still struggling, in zombie-like states, taking on more debt, restructuring, or gradually winding down.

WeWork had similar structure issues—raising massive amounts of capital (over $18 billion total across all funding rounds and debt), having a capital-intensive model, and then facing a scenario where the company was worth something, but not enough to satisfy all the claims against it. They eventually filed for bankruptcy.

Bloom Energy, a distributed power generation company, raised billions in venture and debt capital. They're still operating, but at multiple points they faced scenarios where the company was worth something but less than the combined claims of debt and preferred shareholders.

These aren't companies with broken business models. These are companies where the capital structure became mismatched to the business fundamentals.

For B2B companies specifically, the risk is lower than for capital-intensive hardware or real estate companies. A SaaS company that's bootstrapped to $5M ARR and then raises venture capital is in a much safer position than a company that needs hundreds of millions in capital deployment to prove out unit economics.

But the principle applies: carefully manage the total quantum of capital raised and the structure of that capital.

Questions to Ask Before Taking Any Non-Equity Capital

If you're a B2B founder considering venture debt, RBF, or any form of non-dilutive capital, ask yourself these questions:

1. What's my realistic exit valuation scenario?

Be honest. What do you actually think this company is worth?

2. What happens if the exit is 50% lower than my projection?

Companies often sell for less than founders expect. Growth slows, competition increases, market conditions change. If your realistic exit is

3. What are the debt covenants and how restrictive are they?

Read the debt agreement carefully. Are there restrictions on raising additional capital? Are there minimum cash balance requirements? Are there maximum debt-to-revenue ratios? Any covenant you breach triggers acceleration of the debt, meaning you have to pay it all back immediately.

4. What's the interest rate and how sensitive am I to interest rate changes?

If it's a variable-rate debt, what happens if rates rise 200 basis points? Can your unit economics still work? If it's fixed-rate debt, is the rate acceptable? Would you be better off raising equity instead?

5. Can I explain my capital structure to my employees and have them feel good about it?

If you're issuing equity grants to early employees, they need to understand that their shares have some chance of being valuable. If your capital structure is such that a successful exit results in zero for equity holders, your equity compensation program is not actually compensating people—it's extracting free labor under false pretenses.

6. Do I have a specific use case for this capital that will generate clear returns?

Don't raise debt just because it's available. Raise it because you have a specific deployment strategy: "We'll take

What Should Divvy Have Done Differently?

With the benefit of hindsight, Divvy's founders had several choices that would have resulted in better outcomes:

Choice 1: Raise Less Capital Total

Instead of

Choice 2: Raise More Equity, Less Debt

What if they'd raised that

Choice 3: Be More Conservative With Debt in a Rising Rate Environment

They took on $735M in debt right before the Fed raised interest rates aggressively. If they'd waited six months or done this analysis better, they might have realized that debt was risky. They could have raised more equity at lower valuations instead.

Choice 4: Build to Profitability Instead of for Growth at All Costs

Rent-to-own is a solid business that can generate profit at smaller scale. What if Divvy had been more focused on unit economics and profitability and less focused on rapid growth? Slower growth, smaller raises, lower leverage, and a

None of these choices are obvious at the time they're being made. VCs are pushing for rapid growth. The market is hot. Capital is cheap. The model seems sound. It's easy to raise

But the consequences are real.

Estimated data shows that alternative strategies could have resulted in different capital structures, potentially improving shareholder outcomes. For instance, raising more equity and less debt could align incentives better.

The Broader Lesson: Alignment and Incentives

Underlying all of this is a fundamental misalignment of incentives.

Debt holders want one thing: to get paid back.

Preferred shareholders want two things: to get their capital back with a reasonable return, and to hold onto the possibility of a massive upside if the company succeeds.

Founders want one thing: to build a great company and be rewarded for that if it succeeds.

Common shareholders (founders and employees) want one thing: to be compensated for the risk and work they're putting in.

When capital structures are designed properly, these incentives align. Everyone wants the company to succeed and grow. But when there's too much debt, when there are too many layers of preferred shareholders with liquidation preferences, incentives become misaligned.

The debt holder doesn't care if the company is worth

For B2B founders and VCs, the lesson is: keep the capital structure simple and aligned. Too many layers of capital, too much debt relative to equity, liquidation preferences that are too aggressive—these things sound good when you're raising money, but they create problems later.

What You Should Do If You're Facing This Decision Now

Here's the practical advice if you're a B2B founder deciding whether to take on venture debt or RBF right now:

If You're Pre-Product-Market Fit

Don't take on debt. You don't have revenue to cover the obligations. Focus on raising equity from investors who understand you're taking risks and uncertain about the outcome.

If You're Post-Product-Market Fit With $1-10M ARR

You're in the zone where debt or RBF might make sense. Model your capital needs for the next 2-3 years. If you need

If You're $10M+ ARR and Growing Fast

You're probably raising Series B or C. At this point, most founders should raise equity for most of their capital needs. Using debt to supplement is fine, but equity is cleaner and more aligned. You can probably negotiate good terms given your growth.

If You're Profitable and Don't Need Capital

Profit and reinvest. This is the strongest position to be in. You own the company, you control the destiny, and you won't face a situation where an exit results in $0 for you.

If You're Considering Debt

Before signing:

- Model at least three exit scenarios: 50th percentile (most likely), 25th percentile (worse than expected), and 75th percentile (better than expected).

- In each scenario, calculate what common shareholders receive after debt and preferred liquidation preferences are satisfied.

- If the 25th percentile scenario results in zero for common shareholders, don't take the debt.

- Negotiate the covenants aggressively. Remove or loosen any covenants that would restrict your strategic flexibility.

- Push for a conversion feature: if the next equity round happens and the valuation is X, the debt converts to equity rather than remaining as debt.

- Talk to your cap table advisors or a lawyer who specializes in venture capital. The 0 exit.

The Divvy Homes Aftermath and What It Means for VCs

So what happened after the Divvy acquisition closed? The company is now part of Brookfield Properties. The home portfolio will be managed at Brookfield scale. The technology platform may be maintained or may eventually be shut down in favor of Brookfield's tools. The employees who stayed through the acquisition will keep their jobs, though probably not the fancy startup culture.

The founders and early investors who thought they had a unicorn on their hands had to accept the reality of what their company was actually worth.

For VCs, this is a lesson in capital discipline. Some of the VCs who invested in Divvy (Andreessen Horowitz, Tiger Global, and others) have already adjusted their approaches in subsequent years: they're being more selective about which companies they fund at scale, they're being more thoughtful about the capital structures they create, and they're being more realistic about exit scenarios.

The broader venture ecosystem is shifting toward more sustainable capital structures. The days of "raise as much as you can and figure out spending later" are receding. VCs are increasingly asking founders about capital efficiency, unit economics, and realistic paths to profitability.

That's actually good for founders. It pushes you toward building more sustainable businesses. It discourages overleveraging with debt. It encourages thinking about what the company is actually worth instead of what a FOMO valuation suggests.

Building a Defensible Capital Structure: The Framework

If you're a founder who wants to avoid Divvy's fate, here's the framework for building a defensible capital structure:

1. Calculate Your Capital Needs Conservatively

For a B2B SaaS company: You need capital to cover payroll, go-to-market, and infrastructure until you reach profitability or a clear exit. Calculate this realistically—not optimistically.

2. Raise Equity First, as Much as You Can at Good Terms

Equity doesn't have a repayment obligation. It aligns investor incentives with yours. Raise equity from investors who are long-term focused and won't push you into dangerous leverage.

3. Supplement With Debt Carefully

If you need more capital, consider debt only if:

- Your unit economics are proven and positive

- The debt is less than 25-30% of annual revenue

- You have 24+ months of runway beyond debt servicing

- Interest rates are favorable (not rising)

- You can articulate a clear ROI on the capital deployment

4. Negotiate Liquidation Preferences

When raising equity, push back on aggressive liquidation preferences. Try to negotiate for 0.5x or at least non-participating 1x. If you can't, that's a signal about the investor's confidence in the company.

5. Model Exit Scenarios

Regularly (quarterly or annually) run the math on what various exit scenarios mean for common shareholders. Share this with your team so everyone understands the reality of their equity.

6. Build to Profitability

The strongest defense against all of this is building a business that doesn't need external capital. Profitability is freedom. It's the ultimate defensible capital structure.

Closing: The Real Lesson from Divvy

Divvy Homes'

It's not about whether rent-to-own is a good model (it is, or at least it can be). It's not about whether Divvy's team was incompetent (they weren't—the company lasted nine years and helped thousands of families). It's about the mathematics of capital structures and how easily those math can spiral into unintended consequences.

The easy lesson is: "Don't take on debt." But that's wrong. Debt can be a reasonable tool in the right context.

The real lesson is: Understand your capital structure deeply. Model the consequences. Negotiate aggressively. And never let the quantum of capital raised get wildly mismatched to your realistic exit value.

Your equity is a promise. You're asking people—employees, co-founders, yourself—to take risk in exchange for a piece of the future. If you structure your capital in a way that makes that future worth nothing, you've broken a promise.

Divvy's founders built something real. Brookfield paid a billion dollars for it. But because of debt and liquidation preferences, none of that billion dollars made it to the people who built it.

That's the lesson. And it's worth understanding before you take on your first dollar of non-equity capital.

FAQ

What is a liquidation preference and how does it work?

A liquidation preference is a contractual right that determines the order in which proceeds from a company sale or liquidation are distributed to shareholders. When you raise venture capital, investors typically receive preferred stock with a liquidation preference (usually 1x, meaning they get their invested capital back before common shareholders). If a company sells for

How does venture debt differ from regular bank loans?

Venture debt is specifically designed for venture-backed startups and typically has looser covenants than traditional bank loans because venture debt providers understand startup volatility. However, venture debt is still senior to all equity claims and must be repaid with interest before equity shareholders receive any proceeds. Interest rates are typically 8-15% depending on market conditions and company stage. Venture debt providers also expect to convert some portion of their debt to equity in a future funding round, which is why they're willing to lend to pre-profitability companies without traditional collateral.

What's the difference between participating and non-participating preferred stock?

Non-participating preferred stock means investors get their liquidation preference back, and then they receive pro-rata distributions based on their ownership percentage, just like common shareholders. Participating preferred means investors get their liquidation preference back, and then they also get to participate again in any remaining proceeds on top of common shareholders. Participating preferred is more favorable to investors but worse for founders and common shareholders. Most Series A and early-stage deals use non-participating preferred, but later rounds sometimes push for participating terms.

Why would a founder ever take on $735 million in debt?

Divvy took on debt because their business model was capital-intensive (they literally bought homes), and debt was cheaper than equity at the time (interest rates were low in 2021, and debt doesn't dilute ownership percentage). The founders probably believed the company would continue scaling and reach a $5-10 billion exit, which would have been enough to pay off the debt and still provide substantial proceeds for equity holders. They didn't anticipate interest rate increases in 2022, which made debt servicing more expensive and unit economics less attractive. It was a calculated bet that turned out wrong.

How can I tell if my capital structure is sustainable?

Run the "debt-to-exit" ratio test: divide your outstanding debt by your most conservative exit scenario valuation. If the ratio exceeds 33% (or 0.33), your capital structure is risky. Also calculate the total preferred capital raised and run the liquidation preference waterfall for different exit scenarios (

What should I ask before accepting a venture debt term sheet?

Before accepting, ask: What are the exact interest rate and fees? Are there financial covenants and what happens if I breach them? Can I prepay early without penalty? Does the debt convert to equity in future funding rounds, and at what terms? What is the debt maturity date and what happens if I can't repay at maturity? How much monthly or quarterly cash payment is required? Are there restrictions on raising additional debt or dilutive equity rounds? Get answers in writing and have a lawyer review the agreement. The structure matters more than the interest rate—a good structure at 12% is better than a bad structure at 8%.

Is revenue-based financing better than venture debt?

Revenue-based financing (RBF) is often better for early-stage companies because payments scale with revenue. If you have a month where revenue is slow, RBF payments are lower. With venture debt, you have fixed monthly payments regardless of performance. However, RBF can become expensive if your revenue grows quickly, because you're paying a percentage of a larger number. RBF is best when you have $1-20M in ARR with consistent monthly revenue. For companies with volatile revenue, or very early-stage companies, RBF is less suitable. For mature, fast-growing companies, venture debt is often cheaper overall.

What would have happened if Divvy raised that $735M as equity instead of debt?

The company would have had a more balanced capital structure. Instead of

Key Takeaways

- Debt is senior to all equity claims in liquidations—1B exit proceeds for common shareholders

- Liquidation preferences stack: multiple rounds of preferred investors get 1x capital back before common shareholders see a dime

- The debt-to-exit ratio matters critically—Divvy's 73.5% ratio was nearly 3x the safe threshold of 25-33%

- Interest rate timing is everything: Divvy's $735M debt taken in October 2021 (near-zero rates) became unsustainable when Fed raised rates in 2022

- Equity is often safer than debt for founders: dilution of ownership percentage is preferable to elimination of outcome value

- Model exit scenarios before raising capital: understand what common shareholders receive in 1B, and $5B exits

- Negotiate liquidation preferences aggressively: push for 0.5x or non-participating terms to protect founder outcomes

Related Articles

- Thrive Capital's $10B Fund: What It Means for AI and Venture Capital [2026]

- AI Data Centers Hit Power Limits: How C2i is Solving the Energy Crisis [2025]

- How to Get Into a16z's Speedrun Accelerator: Insider Tips [2025]

- Cherryrock Capital's Contrarian VC Bet on Overlooked Founders [2025]

- Cohere's $240M ARR Milestone: The IPO Race Heating Up [2025]

- How AI Transforms Startup Economics: Enterprise Agents & Cost Reduction [2025]

![Why Divvy's $1B Exit Left Founders With Nothing: The Debt & Cap Table Truth [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-divvy-s-1b-exit-left-founders-with-nothing-the-debt-cap-/image-1-1771508260157.jpg)