Understanding the Windscribe Server Seizure: A Complete Privacy Breakdown

Last year, something happened that made a lot of people nervous about their VPN provider. Dutch authorities seized a physical server operated by Windscribe, one of the more popular consumer VPN services. If you've been using Windscribe and immediately wondered if your data got exposed, you're not alone. But here's what actually matters: the seizure itself didn't compromise user privacy, and understanding why tells you something important about how VPNs really work.

This incident sparked a lot of panic and confusion online. Some people thought Windscribe was compromised. Others deleted their VPN immediately, convinced their traffic logs were now in government hands. Neither assumption was correct, which is why we're breaking down exactly what happened, what it means for your privacy, and how it should inform your VPN choices going forward.

The story starts with a simple fact: VPNs store servers in physical locations around the world. Windscribe, like virtually every other VPN provider, has equipment in data centers across multiple countries. The Netherlands happened to be one of them. When Dutch law enforcement showed up with a court order, they didn't just walk away empty-handed. But the real question isn't what they seized—it's what they could actually do with it.

What makes this case particularly instructive is that it exposed the difference between what people fear will happen with VPNs and what actually happens. The fear: "The government seized my VPN server, so they have all my browsing history." The reality: Windscribe doesn't store browsing history on its servers in a way that connects you to your activity, which is why the company could confidently announce that user privacy remained unaffected according to PCMag.

But this brings us to the harder question: Can you actually trust a VPN provider's claims about their no-logs policy? After all, if a company says they don't keep logs, and then law enforcement shows up, who's to say they're telling the truth? That's where this incident gets genuinely interesting, because it became a real-world test of a company's security architecture and transparency.

TL; DR

- Dutch authorities physically seized a Windscribe VPN server, but this didn't compromise user privacy because Windscribe operates on a no-logs architecture as noted by Cybersecurity News.

- No browsing history or user data was extracted because the company doesn't store per-user connection logs on its servers.

- The incident highlights the difference between server seizure and data compromise: A physical server is just hardware; the data protection comes from encryption and architecture design.

- VPN security depends on architecture, not just geography: Where your VPN provider stores servers matters less than how they store (or don't store) data.

- This became a test case for no-logs claims, validating that security practices matter more than promises in terms of real-world privacy protection.

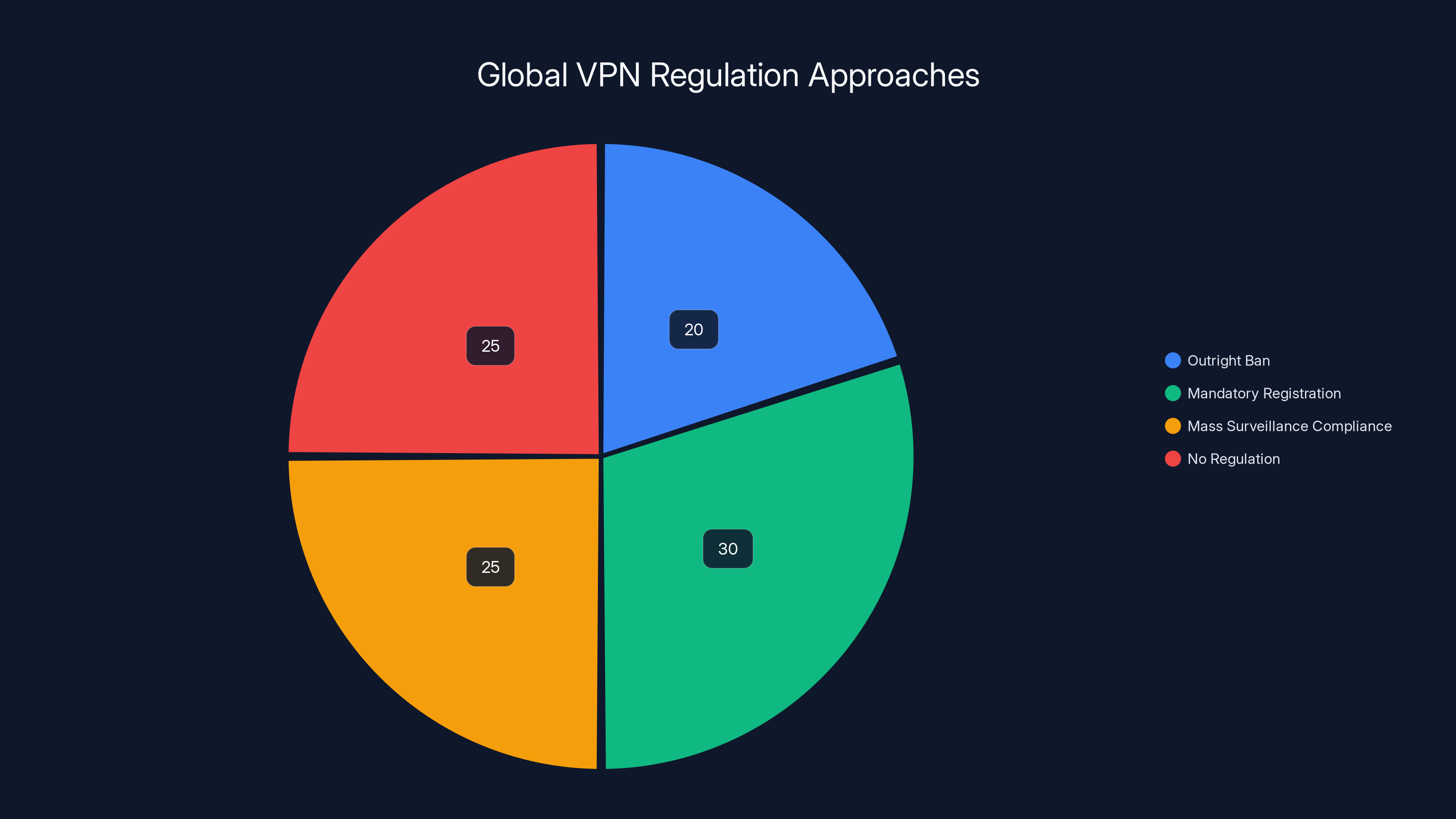

Estimated data shows a diverse range of government approaches to VPN regulation, with a significant portion requiring registration or compliance with surveillance mandates.

What Exactly Happened: The Timeline and Details

Let's establish the facts before speculation takes over. Dutch law enforcement, acting on what appeared to be a court order or legal request, physically seized at least one server belonging to Windscribe that was located in the Netherlands. This wasn't a hack, a warrant for digital data, or a breach. It was straightforward law enforcement confiscating physical hardware as reported by TechRadar.

When this happened, Windscribe responded quickly and transparently—unusual for companies in similar situations. The company confirmed the seizure on its official channels and immediately clarified what that meant for users. No personal data was compromised. No browsing logs were exposed. No user accounts were affected. This clarity mattered because it cut through the initial panic as noted by Engadget.

The reason Windscribe could make these claims with confidence relates directly to how the company designed its infrastructure. Unlike some older VPN services that kept connection logs on servers for accounting, security, or law enforcement purposes, Windscribe built its system around a strict no-logs architecture from the ground up. This means the seized server didn't contain the information that law enforcement might have been looking for in the first place.

That said, we should address the elephant in the room: Can users verify this? Not directly. You can't examine a server before law enforcement takes it to confirm no logs exist. You have to trust the company's architectural claims, historical track record, and third-party security audits. This is exactly why the seizure incident became a credibility test as highlighted by PCMag.

Windscribe had previously commissioned third-party security audits to verify its no-logs claims. These audits didn't specifically predict what would happen if servers were seized, but they did establish that the company's architecture aligned with its public statements. After the seizure, that track record meant something. It was the difference between wild speculation and informed assessment.

The legal basis for the seizure remained somewhat opaque. Dutch authorities didn't publicly explain why they took the server or what investigation prompted it. Without that context, speculation filled the gap. Some assumed copyright enforcement issues. Others guessed upstream piracy investigations. The reality is that governments seize hardware for many reasons, and not all of them involve investigating the VPN provider's users.

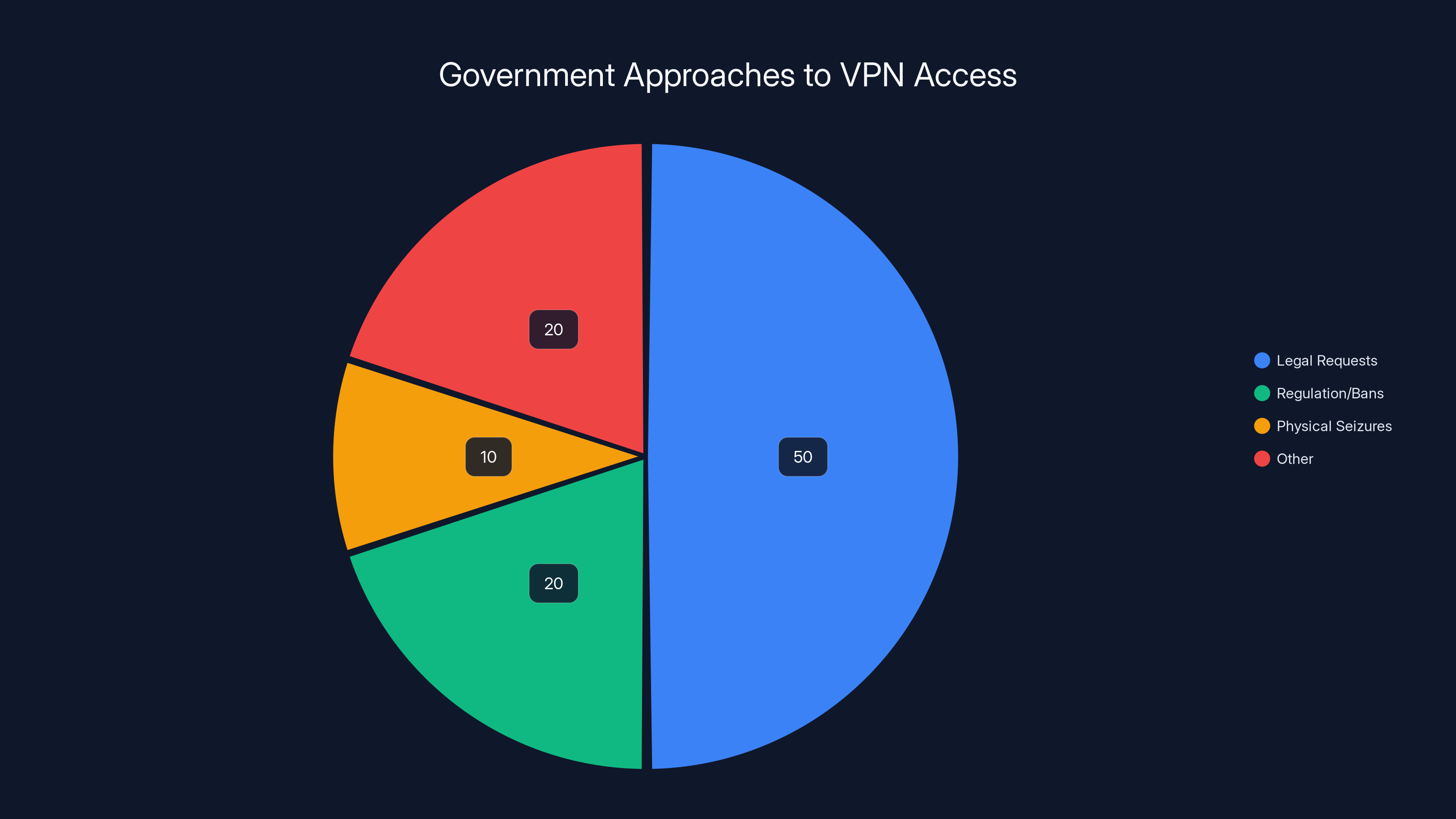

Estimated data suggests that legal requests are the most common method governments use to access VPN data, followed by regulations and bans. Physical seizures, like the Windscribe incident, are less common but notable.

Why Server Seizure Doesn't Equal Data Compromise

This is the critical insight that most people miss. Seizing a physical server is not the same as breaching the data that the server processes. A VPN server is essentially a piece of hardware running software. The value of that hardware to law enforcement depends entirely on what data is actually stored on it.

Consider what a VPN server actually does: It receives encrypted traffic from users, forwards it to the internet on their behalf, receives responses, and sends them back through the encrypted tunnel. In theory, this entire process could generate logs: which user connected, when, from what IP, to which destination, for how long. But generating these logs and storing them are architectural choices, not necessities.

Windscribe's architecture doesn't store these logs in a persistent, user-identifiable way. This means even if you have the physical hardware in front of you, the data you're looking for isn't there to extract. It's like seizing the printing press after the newspapers have already been distributed—the hardware exists, but the information you wanted already left the building as reported by TechRadar.

There's a technical detail worth understanding here. When you connect to a VPN, your connection is encrypted end-to-end. The VPN provider operates in the middle, handling routing. But they can be architected in two ways: They can log every connection (which user, when, to where), or they can process connections without maintaining persistent records. The latter approach is more technically challenging to build and audit, but it's what Windscribe claimed to implement.

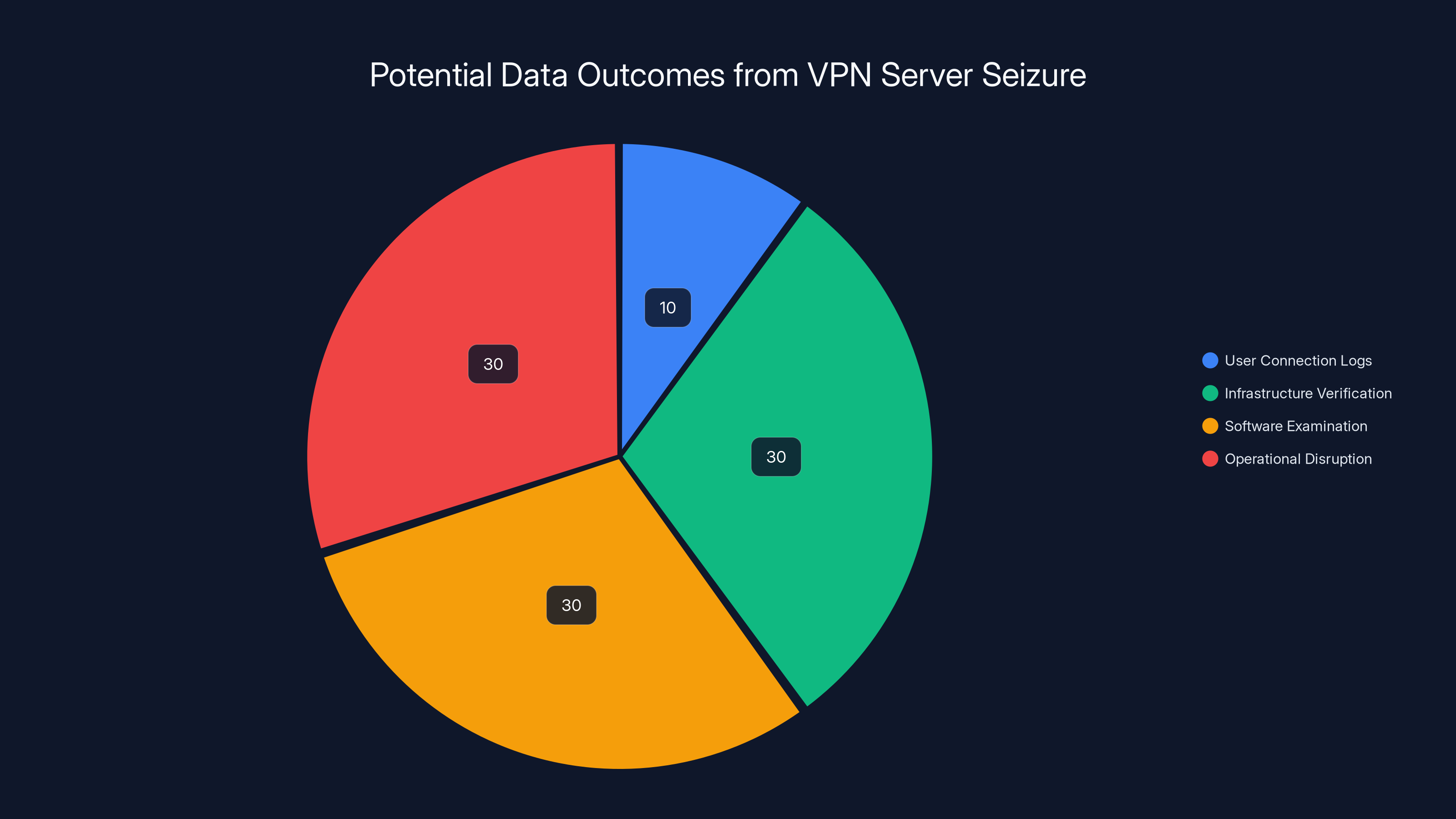

Law enforcement agencies understand this distinction. They seize servers for various reasons: to verify infrastructure capabilities, to examine software and configuration, to extract metadata that might be stored, or sometimes simply as an operational disruption tactic. In Windscribe's case, even with the hardware in hand, extracting meaningful user privacy data would have been impossible if the no-logs architecture was genuine.

This is where independent security audits become crucial. Auditors examine the actual code and architecture to verify that no-logs claims are legitimate. They can't predict law enforcement actions, but they can confirm whether the stated design actually prevents data collection as noted by PCMag.

The No-Logs Policy Debate: What It Actually Means

Here's where things get philosophically interesting. When Windscribe says it operates a no-logs policy, what exactly does that mean? And how does a server seizure help us verify or question that claim?

In the VPN industry, "no-logs" has become marketing shorthand for something more technically specific. It generally means: We don't store persistent records of which users connected, when they connected, what they did, or where they went. But the implementation details matter enormously.

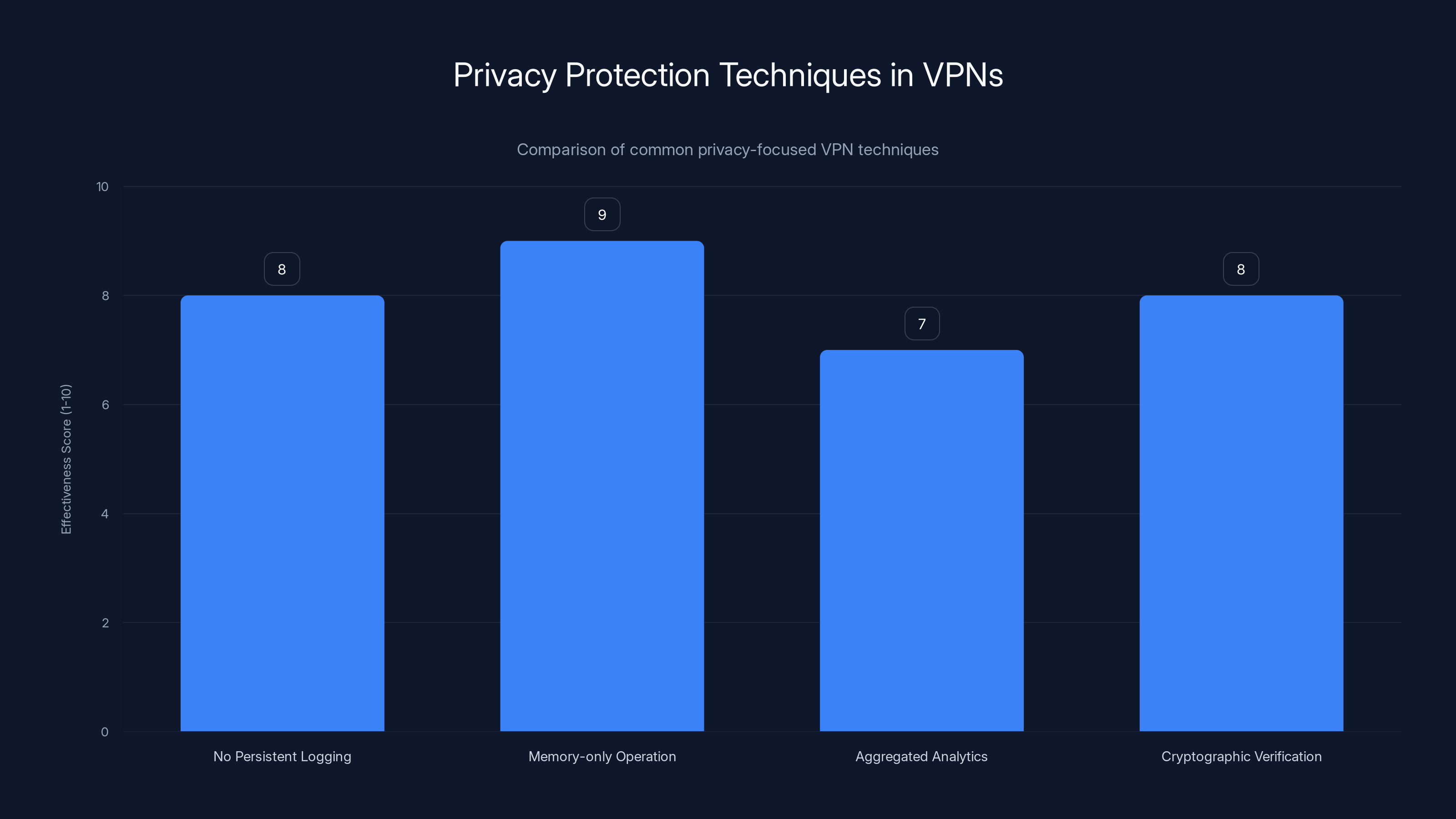

Some VPN providers might genuinely store zero data at all. Others might store temporary data in RAM that gets cleared on reboot, meaning a powered-down server would contain nothing. Still others might store aggregated analytics that can't be traced back to individual users. These are all different implementations of privacy protection, and they deserve different levels of trust.

Windscribe's specific claim is that it doesn't store per-user connection logs. Third-party audits have examined their infrastructure and confirmed this. But what happens when hardware is seized? Theoretically, a sophisticated forensics team could attempt data recovery on hard drives, looking for deleted files or metadata. However, a properly designed system that never writes this data in the first place makes recovery impossible—there's nothing to recover as highlighted by Engadget.

The seizure incident actually validated Windscribe's claims in an unexpected way. If the company had been storing logs and claiming not to, the seized hardware would have revealed it. The fact that Dutch authorities got the equipment but found nothing useful suggests the architecture actually worked as advertised.

That said, we should be honest about the limitations of this validation. Users can't independently verify it. We're relying on the company's statements, third-party audits, and the absence of contradictory evidence. It's not a mathematical proof, but it's meaningful evidence in the privacy space.

The broader implication is that no-logs policies are only as good as the architecture that enforces them. A company can promise not to log data, but if their system is designed to collect logs by default, those promises are worthless. Windscribe's architecture appears designed to prevent logging at the infrastructure level, which is a stronger guarantee than policy alone.

Estimated data suggests that memory-only operation is the most effective privacy protection technique, closely followed by cryptographic verification and no persistent logging.

How VPN Server Locations Actually Matter for Privacy

One consequence of the seizure was renewed discussion about where VPN providers should or shouldn't locate their servers. This is a real consideration, but it's more nuanced than simple geography.

Different countries have different legal frameworks for law enforcement requests. Some jurisdictions have stronger privacy protections than others. Some require warrants for data access; others have broader administrative request powers. This is why VPN providers often claim they choose server locations strategically—to be in places where privacy law is stronger.

But here's the reality that the Windscribe seizure illustrated: Even in jurisdictions with strong privacy laws, law enforcement can seize equipment. There's a difference between being forced to hand over data and being forced to hand over hardware. The Netherlands, despite being in the EU with GDPR protections, was still able to seize the server as discussed in Vocal Media.

What matters then isn't just location, but architecture. A properly designed no-logs VPN provider shouldn't be significantly more or less vulnerable depending on where their servers are located, as long as the servers don't store exploitable data. The seizure becomes a physical inconvenience (the server goes offline) rather than a privacy disaster.

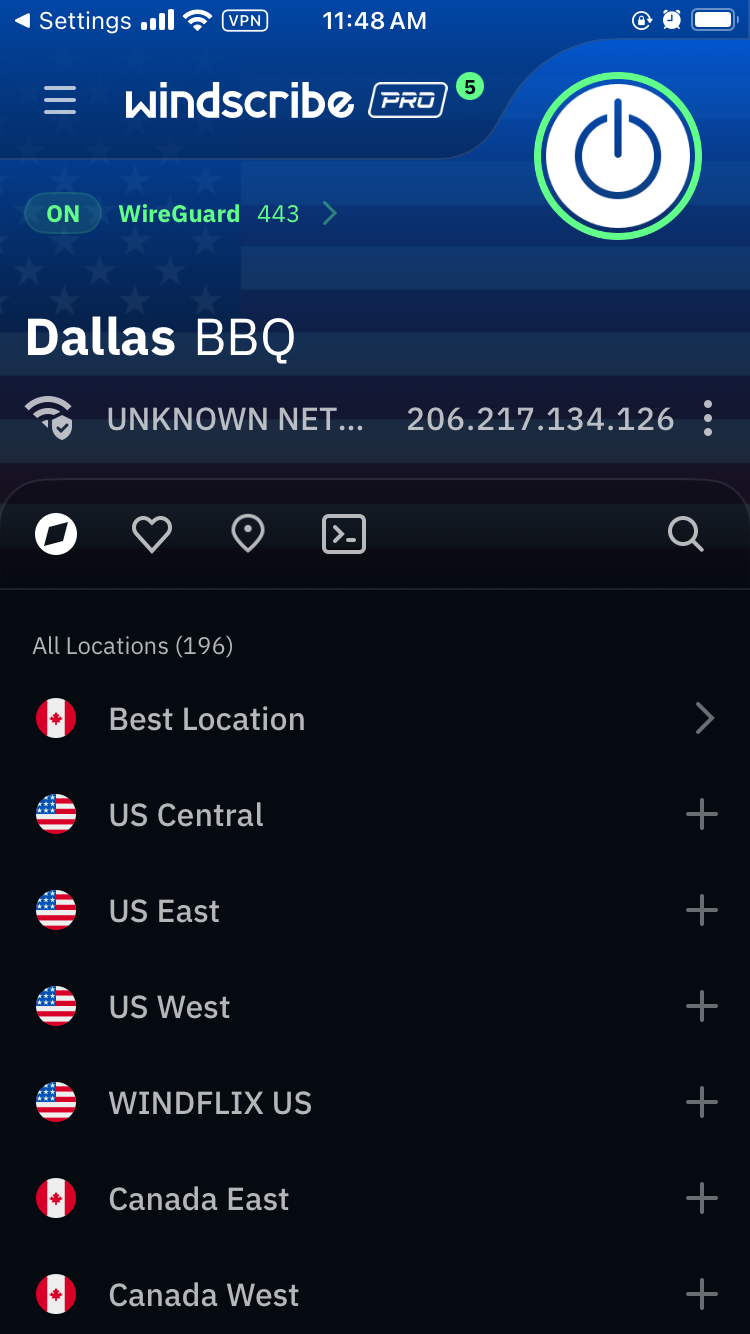

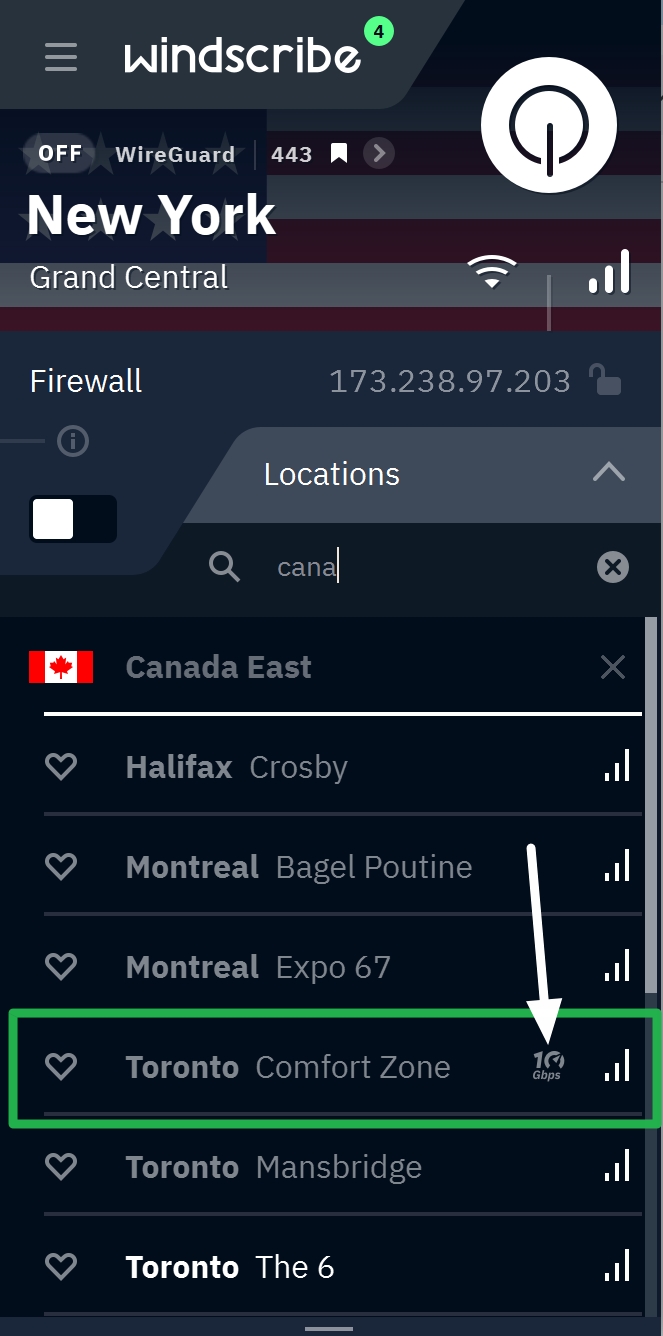

That said, server location still matters for other reasons: jurisdictional disputes, operational resilience, latency optimization, and strategic redundancy. If one server is seized, you want your VPN provider to have backups. Windscribe's network includes servers in multiple countries, so losing one Dutch server was more of an annoyance than a catastrophe.

The incident also highlighted why VPN providers benefit from geographic diversity. If you operate 500 servers worldwide and lose one, your service continues. If you operate 10 servers and one is seized, your users face noticeable service degradation. Scale and redundancy matter more for reliability than any single country's legal system.

Legal Precedent and Government Access to VPN Hardware

The Windscribe seizure wasn't without precedent, though server seizures remain relatively rare compared to other law enforcement tactics. Understanding the legal landscape helps explain why this incident happened and what it might mean for other VPN providers.

Governments worldwide have become increasingly interested in VPN services, viewing them as potential obstacles to investigation. Some jurisdictions have attempted to regulate or ban VPNs outright. Others have pursued specific VPN providers through legal channels, seeking customer data or infrastructure information. The Dutch seizure fits into this broader pattern of government interest in VPN infrastructure as noted by TechRadar.

In most Western jurisdictions, law enforcement typically approaches VPN providers with legal requests: subpoenas, warrants, or mutual legal assistance treaties (MLATs). These requests are handled through official channels and usually involve negotiations about what data can be provided. A physical seizure, by contrast, bypasses that process entirely.

The circumstances around the Windscribe seizure—whether it involved a warrant, what investigation prompted it, and whether it was related to criminal investigation or something else—were never fully clarified. This ambiguity is itself informative. It suggests Dutch authorities may have had sufficient legal justification but chose not to publicly announce details of the investigation.

From a precedent perspective, the seizure is notable because it succeeded without generating major international incident. Windscribe acknowledged it, confirmed privacy wasn't compromised, and moved on. Some might view this as a win for privacy protection—the seizure didn't harm users. Others might view it as a concerning precedent—governments can now seize VPN infrastructure in European countries without severe consequences.

The precedent question becomes: Will other governments attempt similar seizures? Probably yes, but only if they believe doing so would yield useful information. If servers are seized and contain nothing exploitable, the tactic loses effectiveness. This creates an incentive for VPN providers to prove their no-logs architecture actually works.

Even if a VPN server is seized, only a small portion (10%) typically involves user connection logs due to architectural choices. Most outcomes focus on infrastructure verification, software examination, and operational disruption. Estimated data.

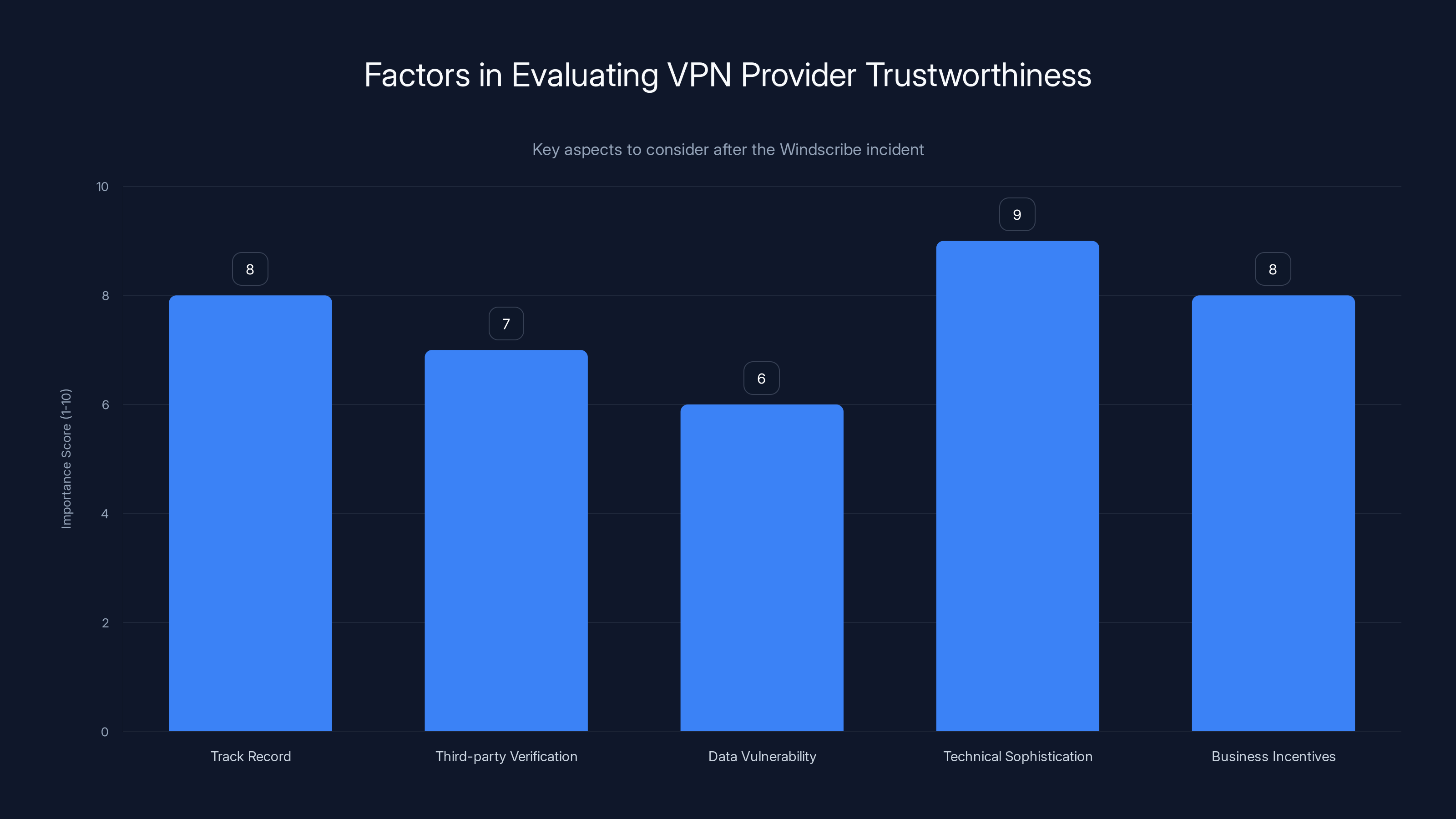

Evaluating VPN Provider Trustworthiness After the Windscribe Incident

If you're using a VPN and this incident made you nervous, that's actually a healthy reaction. It should prompt you to think critically about your provider's actual privacy practices, not just their marketing.

First, assess the company's track record. How has the VPN provider responded to previous government requests? Do they publish transparency reports? Windscribe did publish details about the seizure relatively quickly, which is good. Some companies would have stayed silent. The fact that Windscribe addressed it openly builds credibility as highlighted by PCMag.

Second, examine third-party verification. Has the company commissioned independent security audits? Who performed them? Were the audits comprehensive? Windscribe has undergone third-party audits, which is more than many smaller VPN providers can claim. These audits examined the architecture and confirmed claims about data collection practices.

Third, understand what data is actually vulnerable. Even if a no-logs policy is genuine, other data might exist: billing information, email addresses, payment records. These can link a user to a VPN account but don't reveal browsing activity. Different privacy concerns have different solutions.

Fourth, evaluate the company's technical sophistication. Do they understand security deeply, or are they mostly relying on encryption libraries others built? Companies that understand VPN infrastructure at a deep level are more likely to have designed systems correctly. Windscribe's technical team appears to understand these issues well, which is evident from their architecture choices.

Fifth, consider the company's incentives. VPN providers that rely on reputation and user trust have stronger incentives to maintain privacy than providers that make money through advertising data or affiliate arrangements. Windscribe's business model (subscription based) aligns privacy practices with business success.

Sixth, think about redundancy and resilience. Does the provider have multiple server locations? What happens if one server is seized? Windscribe's distributed network meant the seizure caused minimal service disruption, which is exactly how a resilient system should behave.

None of these factors individually proves a VPN is trustworthy. But collectively, they provide evidence. The Windscribe seizure essentially became a real-world test of the company's stated practices, and the company passed—no user data was compromised because the architecture was designed to prevent it.

The Technical Architecture Behind Privacy Protection

Understanding how VPN privacy actually works requires getting into some technical details, but it's worth understanding because it explains why the server seizure didn't compromise user data.

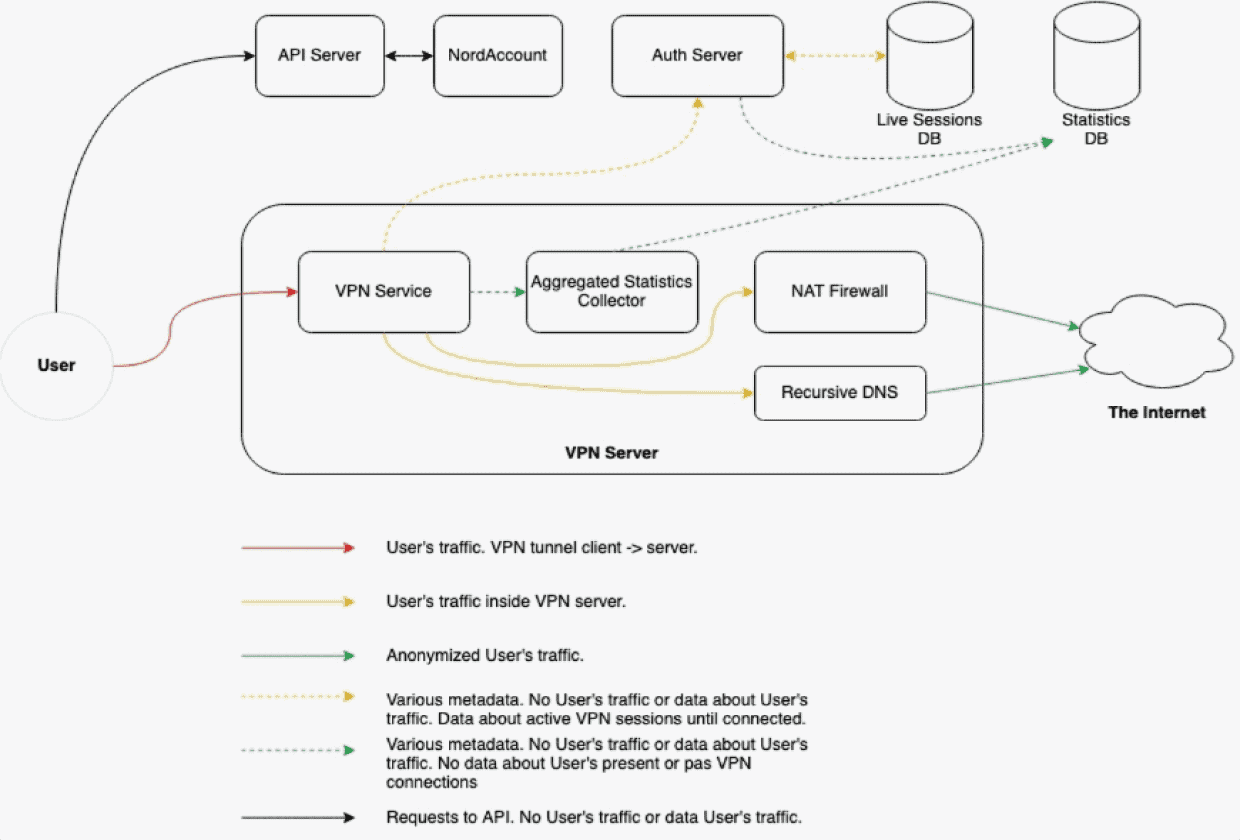

When you connect to a VPN, your device encrypts all traffic destined for the VPN server. The server receives this encrypted stream, decrypts it using a key only it possesses, examines the unencrypted traffic to determine where it should go on the internet, and forwards the request. The response comes back to the server, which encrypts it and sends it back to your device through the encrypted tunnel.

Throughout this process, the VPN server exists in a position to see all of your traffic unencrypted. In theory, it could record everything: the websites you visit, searches you make, emails you send, videos you watch. But recording everything creates massive storage requirements and data liability. Most VPN providers don't do this.

Instead, privacy-focused VPN providers design systems that minimize what data is generated in the first place. Some approaches include:

No persistent logging: The server processes traffic but writes nothing to disk about which user did what. Data stays in RAM temporarily and is lost when the connection closes or the server restarts.

Memory-only operation: Some VPN providers run their software in ways that avoid writing to persistent storage entirely, making data recovery impossible even with advanced forensics.

Aggregated analytics: Instead of user-specific logs, the server maintains only aggregate statistics: "X million bytes were transferred," without identifying who transferred them.

Cryptographic verification: Some advanced systems use cryptography to verify that users connect only for specific purposes without actually recording the connections.

Windscribe's approach emphasizes the no-logs architecture at the infrastructure level. Their servers are designed to process VPN connections without creating persistent, user-identifiable records. This makes the entire data collection problem disappear at the architecture level rather than relying on policies or manual procedures.

The seized hardware couldn't reveal what the architecture never recorded. Even with advanced forensic analysis, you can't extract data that was never written in the first place. This is why the seizure, while certainly disruptive operationally, didn't represent a privacy catastrophe as noted by PCMag.

Evaluating a VPN provider's trustworthiness involves multiple factors, with technical sophistication and track record being particularly important. Estimated data based on typical evaluation criteria.

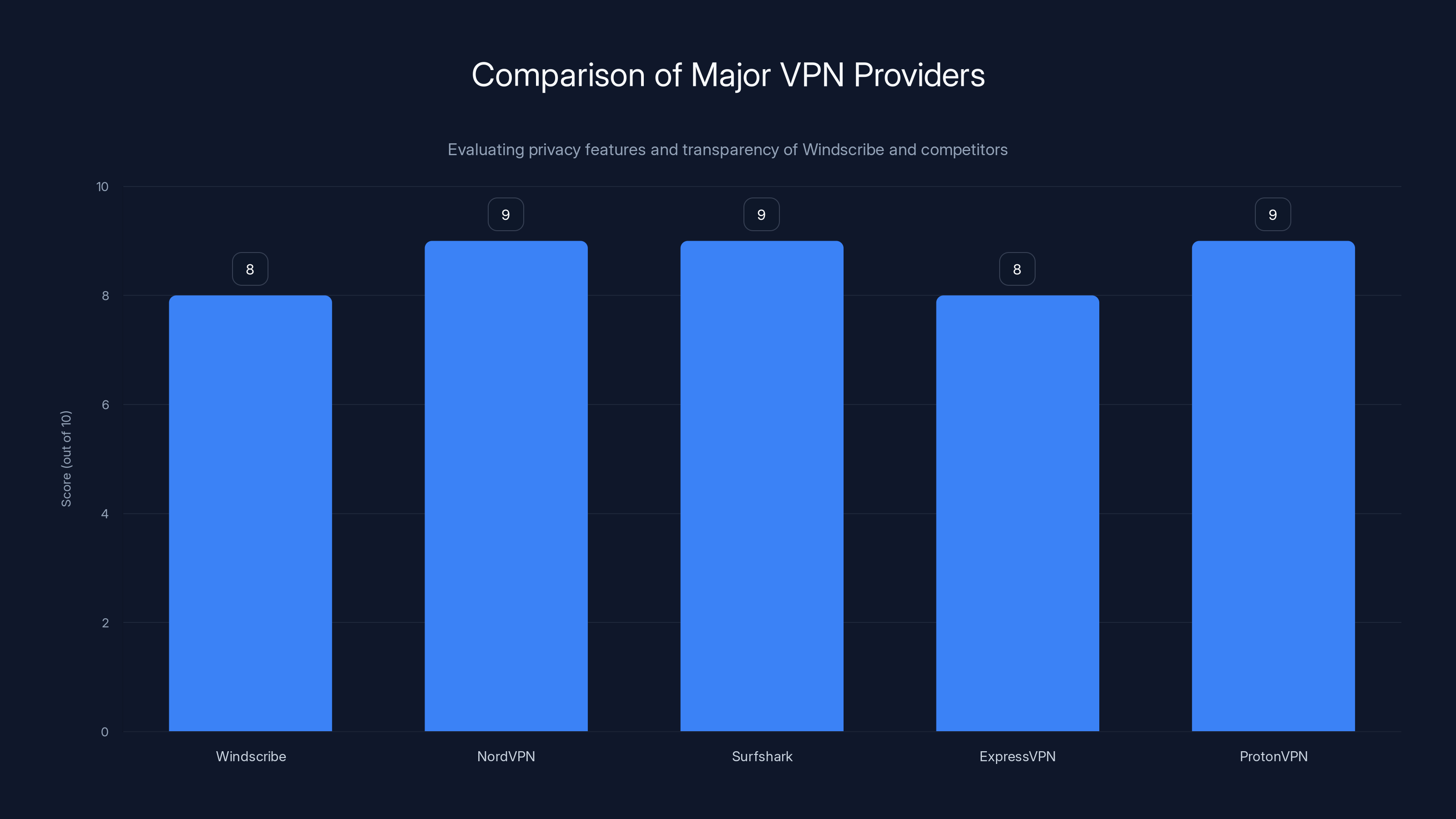

Comparing Windscribe to Other Major VPN Providers

The Windscribe seizure invites comparison to how other major VPN providers handle privacy and infrastructure. Understanding these differences helps contextualize what makes Windscribe's approach notable or not.

Nord VPN operates through Surfshark's parent company, which has been extensively audited and publishes detailed transparency reports. Both have confirmed no-logs policies and undergone independent verification.

Express VPN similarly operates under a no-logs policy and has commissioned third-party audits. The company has been responsive to government requests and law enforcement inquiries while maintaining privacy protections.

Proton VPN, operated by the team behind Proton Mail, emphasizes open-source components and transparency. The company operates servers in Switzerland, a jurisdiction known for strong privacy protections.

Where Windscribe distinguishes itself is in its technical approach to minimizing logs at the infrastructure level and its willingness to be transparent about incidents like seizures. The company doesn't shy away from discussing how the architecture prevents data extraction even when hardware is seized.

The differences between these providers matter less than understanding that multiple approaches to VPN privacy can be legitimate. Some emphasize geographic jurisdiction. Others emphasize technical architecture. Some focus on auditability. The best approach combines all three.

What the Windscribe incident demonstrated is that technical architecture matters more than location alone. A well-architected VPN in any jurisdiction is more privacy-protective than a poorly-architected one in a "privacy haven."

Law Enforcement Capabilities Against VPN Services

What can law enforcement actually do against VPN services, and what does this mean for your privacy?

Direct attack options are limited. Seizing servers, as happened in the Windscribe case, only works if data exists to extract. Hacking into infrastructure is illegal in most jurisdictions and typically only done by intelligence agencies in national security contexts. Legal requests work in jurisdictions with mutual legal assistance treaties, but they require the VPN provider to have data to provide.

Instead, law enforcement often focuses on indirect approaches:

Account information: Law enforcement can subpoena billing records, email addresses, and payment information. A VPN provider can usually provide these without compromising user privacy, since these don't reveal browsing activity.

Metadata correlation: By combining VPN provider information (if available) with other data sources, law enforcement can sometimes triangulate user identity. This is why anonymity-focused VPN users often combine VPN usage with other privacy tools.

ISP cooperation: Law enforcement can approach your internet service provider (ISP) to identify which VPN provider you're connecting to, and when. This doesn't reveal what you do through the VPN, but it can establish you were using one.

Endpoint analysis: Installing malware on your device or access point can capture traffic before encryption, bypassing VPN protection entirely. This is not a VPN weakness—it's a fundamental limitation of any security tool when endpoints are compromised.

Cooperation with foreign governments: Some countries have mutual legal assistance arrangements or intelligence sharing agreements that allow them to request information about citizens of other countries.

What law enforcement can't easily do is extract data from properly architected VPNs. This is exactly what the Windscribe seizure illustrated. The hardware was theirs, but the data wasn't there as noted by PCMag.

For most users, the Windscribe incident should primarily illustrate how important technical architecture is to privacy. It should matter less that Windscribe has servers in the Netherlands, and more that those servers are architected to avoid storing exploitable data.

Estimated data shows that while NordVPN, Surfshark, and ProtonVPN score high due to audits and transparency, Windscribe's unique technical architecture also earns a strong score.

Privacy Implications for Active VPN Users

If you've been using Windscribe or considering using it, the seizure raises practical questions about privacy implications. The good news: your past activity isn't newly exposed because the server didn't store it. The bad news: future activity is subject to the same risks any VPN user faces.

The seizure doesn't change Windscribe's privacy practices or capabilities. If you trusted the service before the seizure, the seizure shouldn't change your assessment, because it confirmed that the claimed architecture actually prevented data extraction. If you didn't trust Windscribe before, the seizure shouldn't change that either.

What the incident does illustrate is that even privacy-focused services operate in physical locations subject to law enforcement. Your server could theoretically be seized anywhere. What matters is that the architecture prevents meaningful data extraction.

For active users concerned about privacy, the relevant questions remain:

- Does the VPN provider truly operate a no-logs architecture?

- Have independent audits verified this?

- Has the company been transparent about government requests and incidents?

- Does the business model align with privacy (subscription) or conflict with it (data monetization)?

- Are the technical team competent enough to implement privacy correctly?

Windscribe's responses to these questions have been relatively strong. The company has commissioned audits, been transparent about the seizure, operates on a subscription model, and demonstrates technical competence. None of these facts changed because of the seizure.

That said, privacy is never absolute. Even properly architected VPNs can be circumvented through endpoint compromise, ISP-level monitoring, or metadata analysis. VPN services are one privacy tool among many, not a complete solution to online privacy.

The Broader Context: VPN Regulation and Government Pressure

The Windscribe seizure didn't happen in a vacuum. It's part of a broader trend of governments worldwide showing increased interest in regulating or restricting VPN services.

Some countries have attempted to ban VPNs outright. Others have required VPN providers to register with authorities or comply with mass surveillance mandates. These approaches reflect government concern about VPNs as obstacles to investigation and surveillance.

The tension is fundamental: Governments want to conduct investigations and expect to be able to access data when warranted. Privacy advocates want individuals to have privacy even from governments without specific, legally-justified reasons to investigate them. VPN services sit in the middle of this tension.

The Windscribe seizure represents a relatively moderate government response: physical seizure of infrastructure rather than demanding backdoors or imposing bans. In some ways, it's preferable to regulatory approaches that would restrict which services can operate or require them to assist in mass surveillance.

But it also demonstrates that operating VPN infrastructure in multiple jurisdictions creates vulnerability to seizure. This might push VPN providers toward consolidation in specific jurisdictions, fewer total server locations, or distributed architectures that are harder to seize.

For users, understanding this broader context matters because it influences which VPN providers remain viable. Companies that can't operate in certain jurisdictions effectively might go out of business or become less useful. VPN market consolidation around a few large providers could reduce competition and innovation.

The incident also highlighted the importance of VPN providers maintaining transparency about government pressure and interference. Companies that publish transparency reports and discuss incidents like seizures are more trustworthy than those that stay silent.

What Independent Security Audits Actually Reveal

Multiple times throughout this analysis, we've referenced independent security audits of VPN providers' no-logs claims. It's worth understanding what these audits actually do and don't reveal.

A comprehensive security audit of VPN infrastructure typically involves:

Code review: Auditors examine the source code that the VPN software runs to identify whether data collection is possible and whether claimed privacy features are actually implemented.

Architecture analysis: Auditors review the system design to understand data flows, what data is stored where, and under what circumstances data might be generated.

Testing: Auditors may test the system in action to verify that no logs are actually created even when theoretically possible.

Documentation review: Auditors examine documentation, policy, and procedures to ensure they align with technical implementation.

What audits can't do:

Predict government actions: Audits can't prevent seizures or predict what law enforcement will do with equipment.

Verify complete honesty: An audit is a snapshot in time. It verifies what the system does at the moment of audit, but can't guarantee the company won't change practices later.

Eliminate all risk: Even properly architected systems can be compromised through other means: employee compromise, malware, endpoint attacks, etc.

Substitute for ongoing monitoring: One-time audits need to be repeated periodically to ensure practices haven't changed.

Windscribe has undergone third-party audits, which is better than no verification. But users should be aware that audits have limitations. They're evidence of privacy practices, not absolute guarantees.

The Windscribe seizure became an unintended "stress test" of audit claims. If the auditors verified that no logs exist, the seized hardware should confirm it by not yielding user data. The fact that no user privacy was compromised suggests the audits were accurate as highlighted by PCMag.

Recommendations for VPN Users Post-Seizure

If the Windscribe seizure has made you reconsider your VPN choice or provider, here's a framework for making decisions:

Verify no-logs claims: Don't accept marketing. Look for third-party audits, transparency reports, and specific technical descriptions of how privacy is achieved.

Evaluate provider responsiveness: How does the company respond to transparency requests, legal inquiries, and incidents? Windscribe's response to the seizure was relatively transparent, which is good.

Assess technical competence: Does the company publish security research? Do team members speak at security conferences? Does the technical approach reflect deep understanding of VPN architecture? These signals suggest a company likely implemented privacy correctly.

Consider your threat model: Different users need different privacy protections. Someone concerned about ISP snooping has different needs than someone concerned about government investigation. Match your tool choice to your actual threat model.

Don't use VPN alone: Combine VPN with other privacy tools. DNS filtering, secure browsers, password managers, and good operational security provide more protection together than any single tool.

Monitor provider status: Subscribe to provider announcements, review regular security audits, and stay informed about regulatory changes. Privacy landscape shifts constantly.

Understand trade-offs: Stronger privacy often means reduced functionality. Some privacy-maximized VPNs are slower or less reliable than commercial alternatives. Understand what you're trading away.

Think about jurisdictional strategy: Some users benefit from VPN providers in specific countries for jurisdictional reasons. Understand the legal landscape where your provider operates.

For Windscribe specifically, the seizure didn't fundamentally change the privacy calculation. The company demonstrated competence in architecture, transparency in response, and no user harm resulted. Those factors haven't changed based on the incident.

The Future: How VPN Services Will Evolve

The Windscribe seizure likely represents the beginning of a pattern rather than an isolated incident. As governments worldwide show increasing interest in VPN infrastructure, we can expect more seizures, regulatory pressure, and attempts to control VPN services.

How will VPN providers respond? Several trends are likely:

Distributed infrastructure: Rather than centralizing servers in data centers, some providers might move toward distributed, peer-to-peer models that are harder to seize. This is technically complex but increasingly feasible.

Geographic consolidation: Some providers might concentrate servers in specific jurisdictions with strong privacy laws, reducing exposure to seizure in unfavorable jurisdictions.

Open-source emphasis: More providers might move toward open-source software that allows independent verification and community auditing. This reduces trust requirements.

Encrypted configuration: VPN server configurations might become increasingly encrypted such that seized hardware is useless even if forensically analyzed. Only the provider with decryption keys could make the hardware functional.

Regulatory compliance: Rather than fighting regulation, some providers might embrace regulatory compliance in exchange for operating licenses. This could formalize the privacy-vs-law-enforcement balance.

User education: Expect VPN providers to invest more in helping users understand privacy limitations and proper use cases. The Windscribe incident was partly educational for the industry.

The long-term trajectory is uncertain. VPN services could become more regulated, less regulated, more private, or more controlled depending on geopolitical and regulatory evolution. But the fundamental technical realities remain: properly architected systems are harder to compromise than poorly architected ones, regardless of geography or regulation.

What users should watch for is continued transparency from VPN providers. Companies that openly discuss incidents, submit to audits, and educate users are more trustworthy than those that operate in shadows and make vague promises.

Key Takeaways and Final Thoughts

The Windscribe server seizure was significant not because it compromised privacy, but because it illustrated how privacy protection actually works in practice.

Here's what the incident teaches us:

Architecture matters more than location: Where a VPN server sits physically matters less than how that server is designed to handle data. A properly architected no-logs system provides privacy regardless of seizure risk.

No-logs claims require verification: Companies can claim anything. Third-party audits, transparency reports, and evidence of technical competence provide meaningful verification beyond marketing language.

Transparency is its own assurance: Companies that openly discuss incidents and vulnerabilities are more trustworthy than those that stay silent. Windscribe's response increased credibility.

Privacy tools work together: VPN is one part of a privacy strategy, not a complete solution. Combining VPN with other tools provides better protection than any single tool alone.

Government interest is growing: Expect more regulatory pressure and operational interference with VPN services. Understanding this reality helps in making informed choices.

Technical competence matters: VPN providers that demonstrate deep understanding of security architecture are more likely to have implemented privacy correctly than those that just wrap commodity encryption libraries.

For Windscribe users, the incident shouldn't prompt panic. For potential Windscribe users evaluating the service, the incident provides evidence of how the company handles privacy in practice. For the broader VPN industry, the seizure represents a test case for privacy architecture in real-world government pressure scenarios.

The fundamental privacy lesson remains unchanged: What matters is what's actually stored, not what's claimed to be stored or where it's stored. The Windscribe seizure became accidental proof that claimed architecture actually works as advertised—no data was compromised because the system never stored it in the first place.

Moving forward, expect similar incidents and similar outcomes as governments worldwide apply more pressure to VPN infrastructure. The winners in this space will be providers that maintain transparent, audited, and technically sophisticated no-logs architectures while adapting to regulatory pressures without compromising privacy fundamentals.

FAQ

What happened when Dutch authorities seized Windscribe's server?

Dutch law enforcement physically seized a server that Windscribe operated in the Netherlands. However, because Windscribe implements a no-logs architecture where user data isn't persistently stored on servers, the seizure didn't result in any user privacy compromise or data exposure.

Did the seizure expose user data or browsing history?

No user data was compromised. Windscribe confirmed that its architecture doesn't store per-user connection logs or browsing history on servers, so the seized hardware contained no exploitable user information. This incident actually validated the company's no-logs claims in a real-world scenario.

How does a VPN provider protect user privacy if their server is seized?

Privacy protection comes from architecture design, not location. If a VPN provider is designed to not store user-identifiable connection logs or browsing data, then even seized hardware can't yield that information. The data simply doesn't exist to be extracted, regardless of physical possession of the server.

Should I switch away from Windscribe after the seizure?

The seizure itself isn't a reason to switch. The incident actually demonstrated that Windscribe's claimed no-logs architecture works in practice—the seized server contained no user data. If you trusted Windscribe before the seizure, you have more reason to trust it now based on this real-world test of their privacy claims.

What are the differences between server seizure and a data breach?

Server seizure is law enforcement taking physical possession of hardware (a legitimate legal action). A data breach is unauthorized access or theft of data. These are fundamentally different situations. The Windscribe seizure was the former—law enforcement had the hardware but couldn't extract meaningful data because it was never stored there.

Do other VPN providers have similar no-logs architectures?

Yes, major VPN providers like Nord VPN, Express VPN, Surfshark, and Proton VPN all claim no-logs policies and have undergone third-party security audits to verify them. The specific implementations differ, but the goal—avoiding storage of user-identifiable connection data—is similar.

How can I verify a VPN provider's no-logs claims?

Look for: published third-party security audits from reputable firms, transparency reports showing responses to government requests, open-source components allowing community verification, technical documentation describing architecture, and company history of transparency about incidents. Don't rely on marketing language alone—look for evidence.

What can governments actually do against VPN services?

Governments can seize physical servers (as happened with Windscribe), request user data through legal channels, approach ISPs to identify VPN users, attempt to regulate VPN services, or pursue accounts linked to illegal activity. What they struggle with is accessing browsing data from properly architected no-logs VPNs, which is why architecture design matters more than location.

Is VPN enough to guarantee privacy online?

No. VPN is one privacy tool that protects against ISP snooping and helps with anonymity, but it doesn't protect against malware on your device, compromised endpoints, or advanced forensics. Combine VPN with other tools like DNS filtering, privacy browsers, password managers, and good operational security for comprehensive protection.

Why does server location matter if the architecture prevents data collection?

Server location matters for operational reasons (regulatory compliance, law enforcement jurisdiction, network reliability) but less for privacy if the architecture is sound. A well-architected no-logs VPN in any country provides privacy protection. Conversely, a poorly architected VPN in a "privacy haven" provides false security. Architecture trumps geography for privacy protection.

Helpful Resources for VPN Users

For those looking to deepen their understanding of VPN privacy and technology:

Security Audits and Verification: Look for VPN providers that publish results from reputable third-party security auditors. Reports from firms like Deloitte, Cure 53, or other established security companies provide meaningful verification of privacy claims.

Government Request Transparency: Many VPN providers now publish regular transparency reports showing government requests they've received and how they've responded. These reports are increasingly detailed and informative.

Technical Documentation: Advanced users can learn from detailed technical documentation that explains VPN architecture, encryption protocols, and data handling practices. This separates providers with genuine technical sophistication from those with surface-level privacy claims.

Privacy Communities: Online privacy communities and forums often discuss VPN services, new incidents, and recommendations. Communities like r/privacy on Reddit or Privacy Tools forums provide crowdsourced information about provider reliability.

Security Conferences: Many VPN provider technicians speak at security conferences, explaining their approaches to privacy and architecture. These talks often reveal genuine expertise versus marketing.

Regulatory Tracking: Following privacy regulation changes (GDPR, upcoming digital privacy laws, government VPN restrictions) helps understand the legal landscape where your VPN provider operates.

The Windscribe incident illustrated that informed VPN users benefit from understanding actual technical practices, not just marketing claims. Continuing to educate yourself about VPN technology helps in making better privacy decisions.

Related Articles

- Qilin Ransomware Gang Hits Tulsa Airport: What You Need to Know [2025]

- FBI Seizes RAMP Cybercrime Forum: What Happened & What It Means [2025]

- Microsoft Office CVE-2026-21509 Security Flaw: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Grubhub Data Breach 2025: What Happened and How to Protect Yourself [2025]

- Major Shipping Platform Exposed Customer Data, Passwords: What Happened [2025]

- NordVPN Salesforce Breach Claim: What Really Happened [2025]

![Windscribe VPN Server Seized by Dutch Authorities: What It Means for Your Privacy [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/windscribe-vpn-server-seized-by-dutch-authorities-what-it-me/image-1-1770388739678.jpg)