Introduction: When Recruitment Becomes a Spectacle

Palmer Luckey has a reputation for thinking differently. The founder of Anduril, the defense tech startup that's quietly reshaping how autonomous systems work, decided his company needed a new way to find talent. Most tech companies host hackathons. Some run coding competitions. Anduril? They're launching an international drone racing series where the prize isn't just money. It's a job at one of the most interesting defense tech companies in the world, with the chance to completely skip the traditional hiring gauntlet.

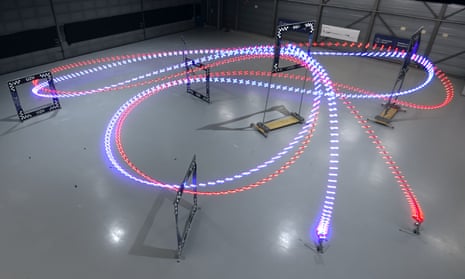

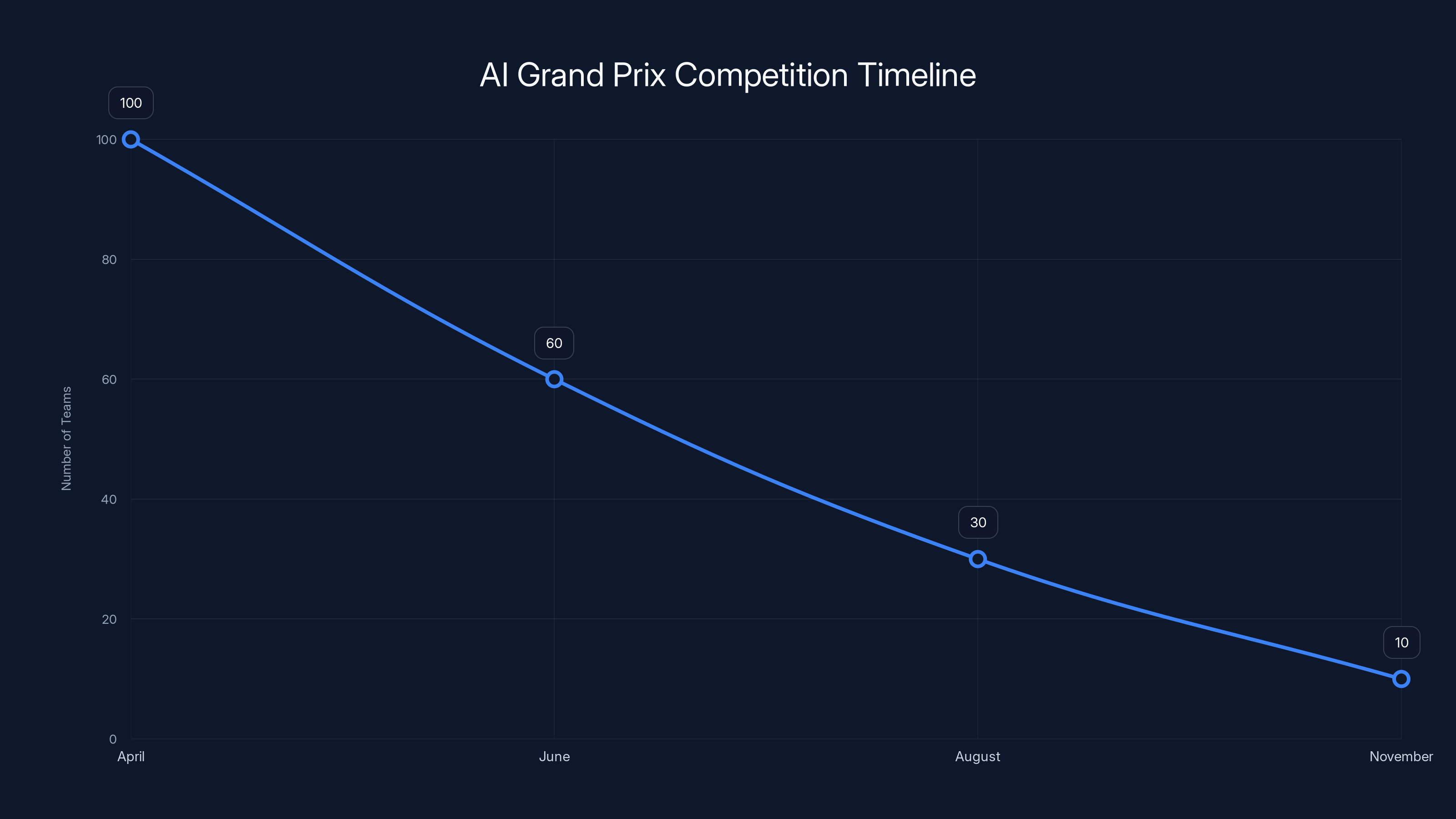

The AI Grand Prix is exactly what it sounds like: a high-stakes autonomous drone racing championship where software engineers and programmers write the code that flies the drones. No human pilots. No joystick controllers. Just algorithms, machine learning models, and the relentless pursuit of speed. Teams will compete across three qualifying rounds starting in April, leading up to a November finale in Ohio with a prize pool that starts at $500,000.

On the surface, it's a clever recruiting gimmick. But dig deeper, and you'll see it's something more interesting. It's a statement about where autonomous technology actually is right now, what companies need from their engineers, and how the competition for top talent has evolved beyond salary negotiation and stock options. Luckey didn't come up with this idea casually. During a meeting about recruitment strategy, someone suggested sponsoring an existing drone racing league, like the Drone Champions League. Luckey pushed back hard. His company's entire reason for existing is built on the premise that autonomous systems have finally matured enough that you don't need humans micromanaging every decision. So why would they sponsor a competition about human-piloted drones? The logic was airtight. If Anduril believes in autonomy, they should sponsor something that proves it. When the team realized no one was actually running an autonomous drone racing event, they decided to create one themselves.

What emerges is a fascinating case study in modern recruitment strategy, autonomous technology maturity, and what happens when a founder with deep expertise in both hardware and software decides that traditional hiring is inefficient. This isn't just about racing drones. It's about signaling to the world's best autonomous systems engineers that Anduril understands their craft deeply enough to design a competition that matters.

The Genesis: How a Recruiting Conversation Led to an International Competition

Luckey recalls the moment clearly. The executive team was sitting down to discuss recruitment strategy for the year ahead. Anduril, like every other defense and tech company, faces the constant challenge of attracting world-class engineers who could work anywhere. Someone in the room threw out an idea: sponsor a drone racing tournament. It's good brand exposure, aligns with hardware innovation, and drone racing is genuinely cool.

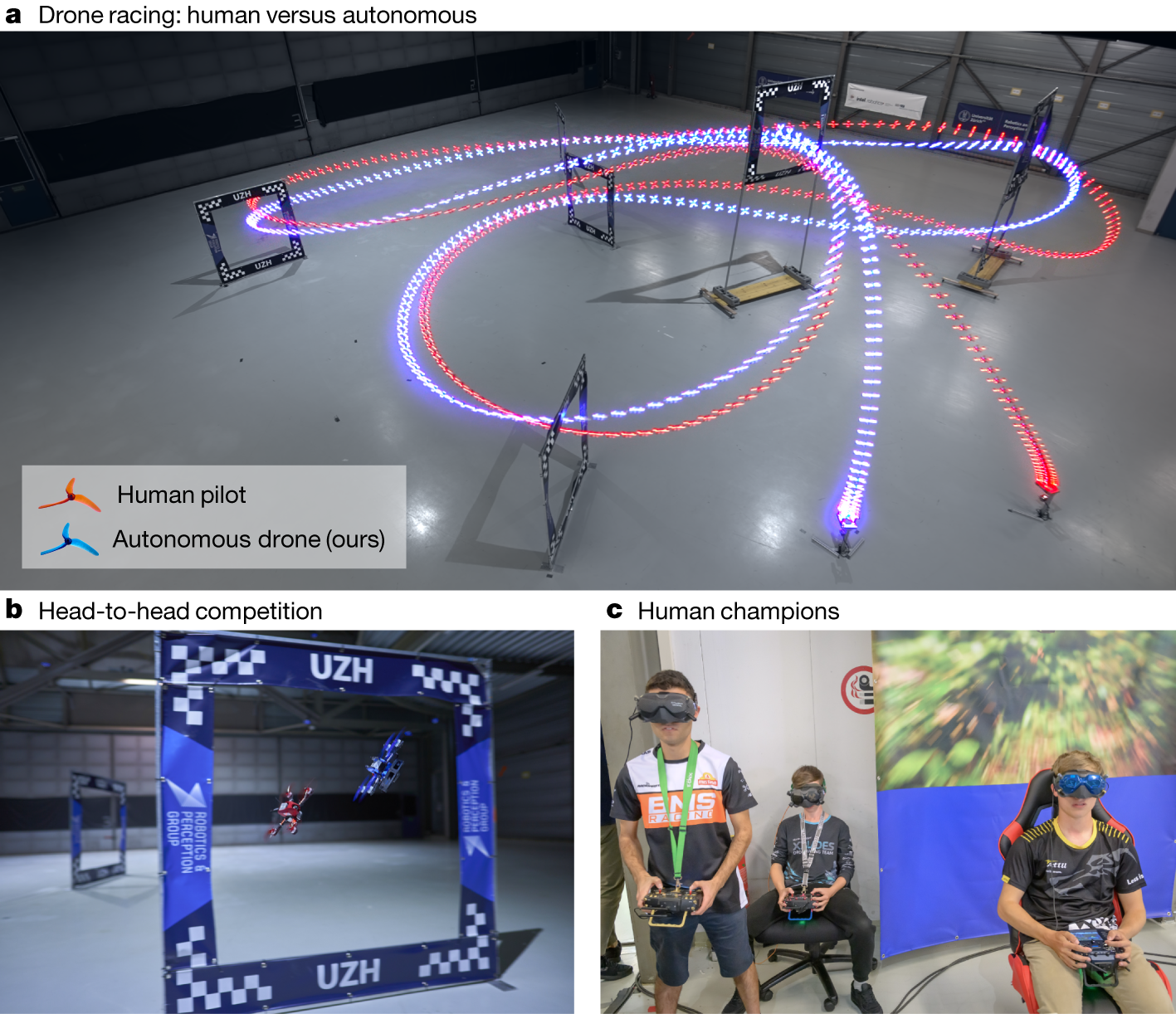

Luckey listened, then pushed back. His critique wasn't about drone racing itself. It was about the fundamental mismatch between what those races showcase and what Anduril actually does. The Drone Racing League, the most established series in the space, features human pilots flying high-speed quadcopters through three-dimensional courses. Spectators watch human reflexes and skill on display. But Anduril's entire pitch to customers, investors, and potential hires is built on a completely different proposition: autonomy works. Humans can't keep up with autonomous systems in terms of speed, reaction time, and coordination. If Anduril was going to put their name on a racing event, it should demonstrate that principle.

Luckey told his team: "What we should really do is sponsor a race that's about how well programmers and engineers can make a drone fly itself." That's when they realized this event didn't exist. The global drone racing community had gravitated toward human piloting because that's what spectators found exciting. But an autonomous drone racing league? That was virgin territory.

The decision to build rather than sponsor something existing reveals a lot about Anduril's confidence in autonomous systems. Most companies wouldn't bet this hard on a space that doesn't yet exist. But Anduril isn't most companies. It's raising billions in funding to build autonomous systems for military and defense applications. Its customers are the U.S. Department of Defense and allied nations. If there's any company that believes autonomous technology has reached maturity, it's them.

The partnership structure that emerged reflects Luckey's pragmatism. Anduril couldn't use its own drones because, frankly, they're too large and sophisticated for a compact racing course. The company's platforms are built for surveillance, threat detection, and autonomous operations at larger scales. So Anduril partnered with Neros Technologies, another defense tech startup that builds smaller, faster autonomous quadcopters. This signals something important: Anduril's willingness to collaborate with competitors when it makes sense. They're not trying to monopolize the recruitment event. They're genuinely trying to build the best possible competition.

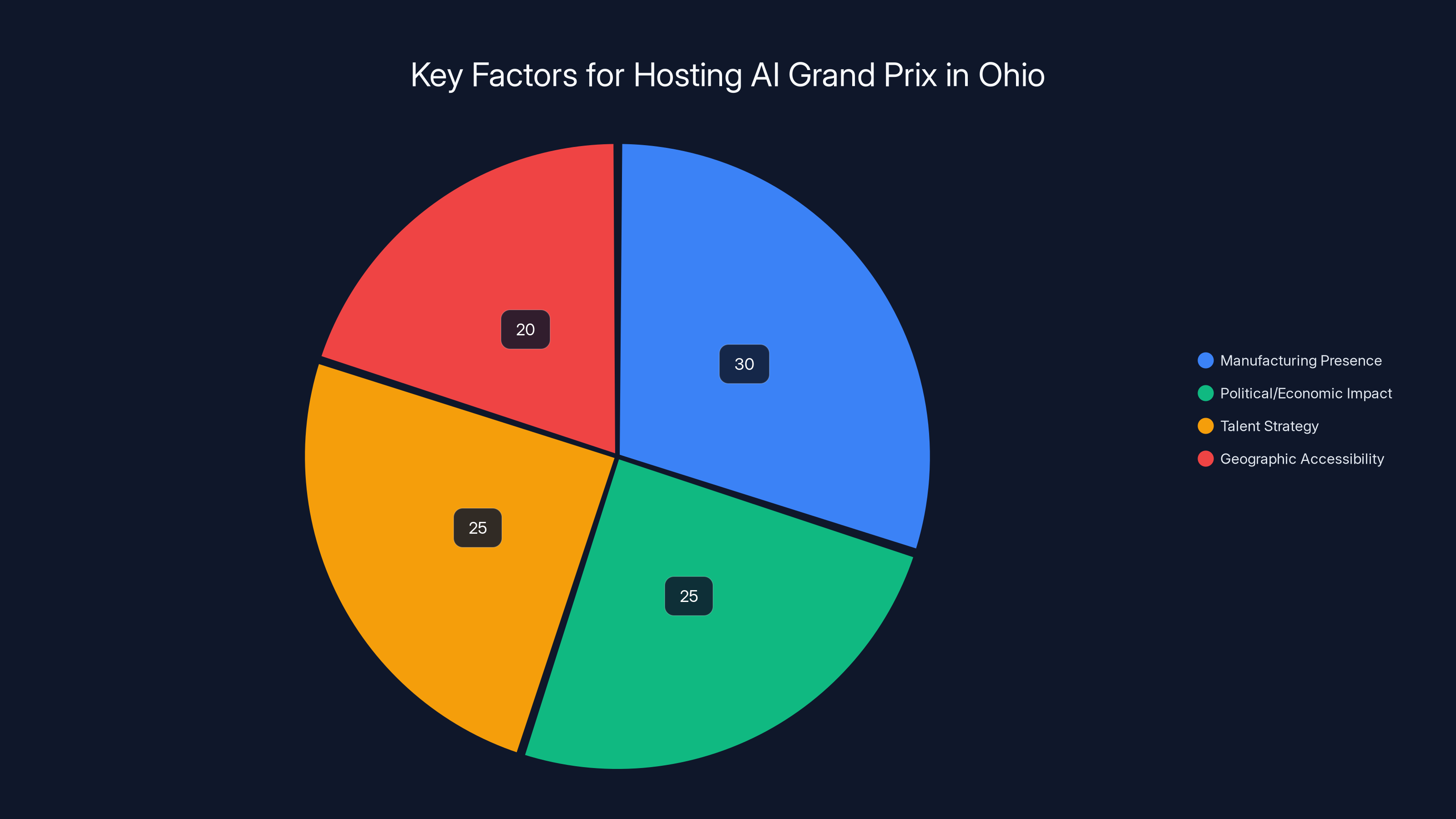

The operational partner is the Drone Champions League, one of the world's established racing organizations. And Jobs Ohio provides local support for what will be the competition's finale. The finals location in Ohio is no accident. Anduril has significant manufacturing operations there. Hosting the grand finale in your home state serves multiple purposes: showcasing local economic impact, celebrating the region's role in building autonomous systems, and demonstrating commitment to the community where your engineers actually live and work.

The AI Grand Prix offers a $500,000 prize pool, with the largest share going to the first-place team. Estimated data based on typical prize distributions.

Understanding the AI Grand Prix Format: How the Competition Actually Works

The AI Grand Prix isn't a traditional racing league. There are no individual competitors frantically flying drones through courses while crowds watch from bleachers. Instead, teams of software engineers spend months developing algorithms and machine learning models that control the drones. The actual racing is what happens when those algorithms execute in real-time against competitors' code.

The structure is deliberately modular to accommodate teams from diverse backgrounds. Anduril is targeting university teams, startup hackathon veterans, independent engineer collectives, and even international competitors. The qualification format runs across three rounds beginning in April, with teams gradually winnowing down to those competing in the November grand finale in Ohio.

Each qualifying round serves a specific purpose. Early rounds test the fundamental capability of teams to produce code that keeps a drone stable, responsive, and capable of executing basic maneuvers. Teams must demonstrate their drones can navigate predefined waypoints without crashing. It sounds simple, but autonomous flight is deceptively complex. You're not just writing code to move a drone from point A to point B. You're building real-time control systems that account for wind, sensor noise, motor variations, battery degradation, and computational latency.

Later qualifying rounds introduce obstacles and increasingly demanding course designs. Teams must demonstrate not just stability but speed. Their algorithms must decide how aggressively to pitch, roll, and yaw the drone while maintaining structural integrity and battery efficiency. This is where engineering excellence becomes apparent. A mediocre team might produce code that barely works. An excellent team produces code that's elegant, efficient, and fast.

The grand finale course in Ohio is reportedly the most demanding. Teams will fly identical Neros Technologies drones through a three-dimensional obstacle course that tests both speed and precision. The drones that cross the finish line fastest, without crashing, win. Simple premise. Execution is brutally difficult.

Luckey expects at least 50 teams, with confirmed interest from multiple universities. That number matters because it suggests the competition is legitimate enough to attract serious participants. University teams bring resources, training infrastructure, and access to talent pools. They also bring institutional credibility. If MIT, Stanford, Carnegie Mellon, and UC Berkeley students are competing, everyone pays attention.

International participation adds another layer of complexity and excitement. Anduril opened the competition to teams worldwide, with one significant exception: Russia. The company explicitly cited Russia's ongoing invasion of Ukraine as the reason. Luckey noted that the people qualified to compete in such a race might also be working for military organizations, creating potential security concerns. China is notably welcome, despite being consistently identified by U.S. autonomous weapons experts as the primary competitive threat. However, Chinese military employees would not be offered jobs at Anduril, a restriction that Luckey acknowledges is driven by U.S. law rather than company policy.

The Prize Structure: Beyond Just Money

The financial incentive is real. The $500,000 prize pool gets distributed among the highest-scoring teams, and that's substantial. For university teams operating on shoestring budgets, that money could fund an entire year of research and development. For independent engineer collectives and startups, it's serious capital for further development.

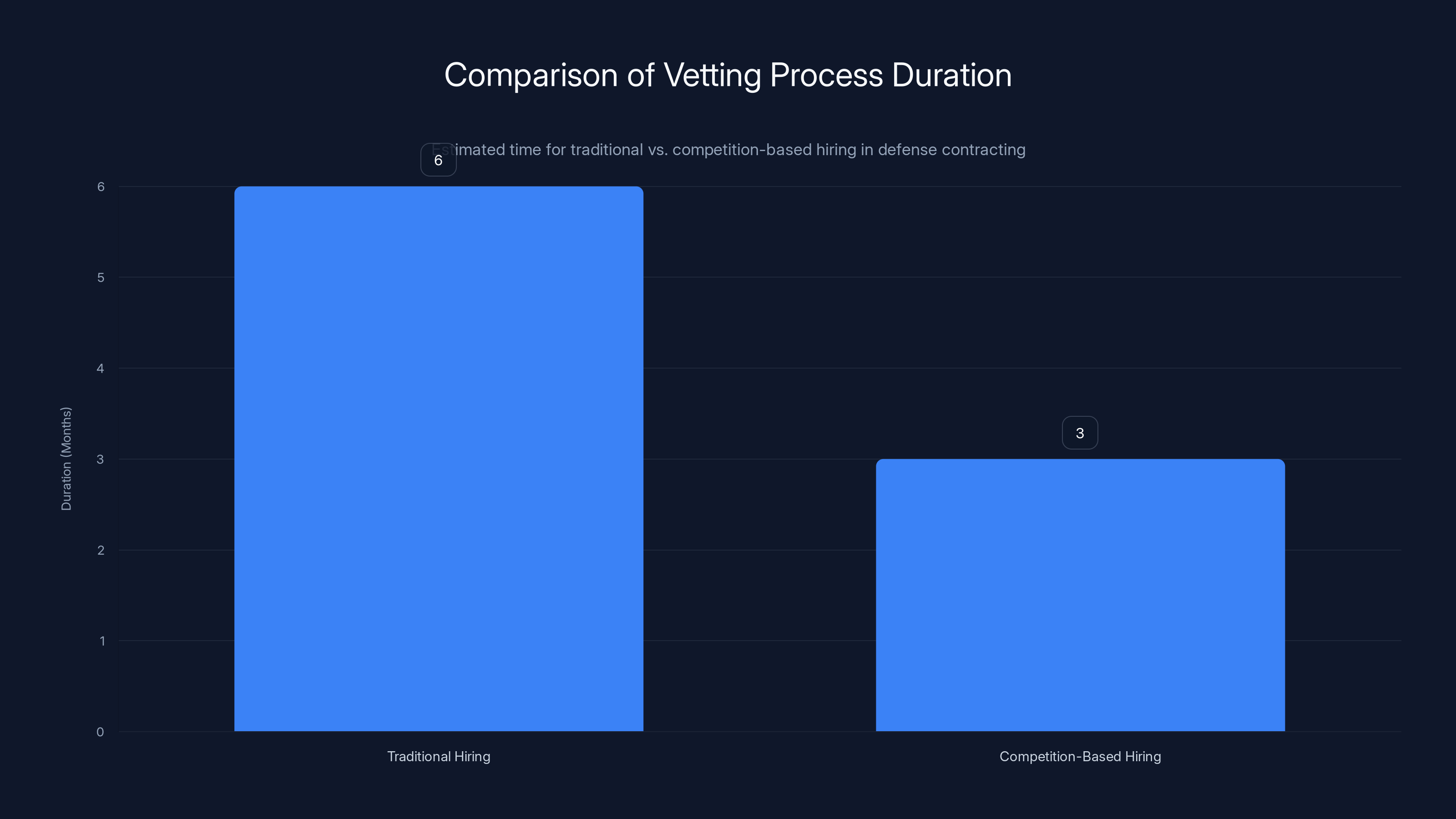

But the real prize isn't cash. It's the job offers. Anduril is directly recruiting through this competition, and winners get to bypass the traditional hiring cycle entirely. Normally, landing a job at a top-tier defense tech company means navigating extensive interviews, background checks, security clearances, and technical assessments. The process can take months. Competition winners skip straight to employment discussions, assuming they pass the basic qualification hurdles.

This is genuinely different from most tech competitions. A hackathon might offer prize money and maybe some mentorship. The AI Grand Prix offers a genuine pathway into one of the most interesting engineering organizations in defense tech. For someone who's spent months building autonomous drone algorithms, the chance to work on Anduril's actual systems with unlimited resources and the best co-workers in the field is worth far more than the monetary prize.

Luckey is careful to note that winning doesn't guarantee a job offer. There's still an interview process. Winners still need to pass background checks and security screening. But the screening becomes almost ceremonial compared to the full recruitment gauntlet. You've already proven you can write sophisticated autonomous flight control code. The company has already verified you can compete at an elite level. The remaining questions are mainly about fit, communication skills, and security clearance eligibility.

This structure also signals something about Anduril's hiring philosophy. The company values demonstrated capability over pedigree. A brilliant engineer from an obscure university who wins the competition is objectively more attractive than a mediocre engineer from Stanford who interviewed well. The competition is a sorting mechanism that identifies genuine talent.

Autonomous drones outperform human-piloted drones in speed, reaction time, and coordination, but lag in spectator excitement. (Estimated data)

Why Autonomous Drone Racing Matters for Defense Tech

Autonomous systems are no longer theoretical concepts or research projects. They're operational reality. The U.S. military and allied nations are deploying autonomous and semi-autonomous systems in increasingly diverse roles. Surveillance drones are only the beginning. As technology matures, autonomous systems will handle targeting, logistics, coordination, and decision-making at scales human operators cannot match.

But developing this capability requires specific skills. Software engineers need deep understanding of control theory, real-time computing, sensor fusion, optimization algorithms, and machine learning. They need to think in three dimensions and understand how small changes in code produce dramatically different physical behaviors.

Drone racing is the perfect test case for these skills because it's concrete and measurable. Either your drone completes the course faster than competitors, or it doesn't. There's no ambiguity. The engineering challenges you face in autonomous racing are directly applicable to military autonomous systems. Both require real-time decision-making, both require handling imperfect sensor data, both require optimization across multiple competing objectives.

Anduril's decision to build this competition reveals confidence that autonomous technology is ready for this kind of public demonstration. The company is essentially saying: "Our engineers can make autonomous systems work at scale and at speed. We're confident enough in that capability to have it judged in public competition." That's a powerful statement to customers, to potential hires, and to the broader defense community.

The racing format also democratizes access to expertise. A brilliant engineer working at a startup in rural Missouri has just as much opportunity to compete as someone at Stanford. The only requirement is the ability to write excellent code. That meritocratic approach appeals to engineering talent that might otherwise never interact with major defense contractors.

The Role of Neros Technologies: A Strategic Partnership

Anduril using Neros Technologies drones instead of its own platforms might seem counterintuitive for a company that manufactures defense hardware. But it's actually a sophisticated strategic choice.

Anduril's drones are built for specific military applications. They're optimized for surveillance, endurance, payload capacity, and integration with command systems. They're not optimized for racing. Racing drones need to be lightweight, responsive, and capable of extreme maneuvers. The design priorities are completely different. Forcing a military surveillance drone to race would be like making a cargo truck compete in Formula One. You'd be fighting against fundamental design choices.

Neros Technologies fills this gap perfectly. The company specializes in small, fast autonomous quadcopters. Their platform is designed for the exact kind of high-performance, high-maneuverability flight that racing demands. By partnering rather than competing, Anduril demonstrates maturity as an organization. They're choosing the best tool for the job rather than forcing their own product into an inappropriate role.

This partnership also has broader strategic implications. Anduril is sending a message to the broader autonomous systems ecosystem: we collaborate when collaboration serves the goal. We compete where competition makes sense. This positioning makes Anduril attractive to other companies and organizations that want to work with partners rather than subsidiaries.

For Neros, providing the drones for Anduril's competition is valuable exposure. Engineers from around the world will spend months optimizing code for Neros platforms. That deep engagement builds expertise and advocates. Some of those engineers will eventually choose to work with Neros or integrate their systems with Neros products. Win-win dynamics like this are becoming increasingly common in defense tech, where specialization and integration often work better than vertical integration.

Luckey's Hardware-First Philosophy Applied to Recruitment

Palmer Luckey describes himself as "a hardware guy. An electromechanical and optical guy." He explicitly notes that he's not a particularly skilled software programmer. Instead, he knows "just enough about coding to glue stuff together in a way that works for my prototypes." This self-assessment is revealing because it explains why he approached the recruitment problem the way he did.

Luckey thinks in systems. He sees a problem (finding great software engineers) and designs an entire system to solve it (autonomous drone racing competition). He doesn't think small about recruitment. He thinks about what an ideal system would look like if you had unlimited creativity and resources.

He also delegates. He explicitly identifies Anduril CEO Brian Schimpf as the company's "de facto lead software brains." Luckey knows his strengths and weaknesses. He builds organizations where his weaknesses are covered by people stronger in those areas. That's why he's comfortable designing a competition that prizes software engineering excellence, even though software isn't his personal specialty.

This approach to leadership has interesting implications for the competition itself. Because Luckey isn't a software expert trying to design a competition to showcase software expertise, he had to think deeply about what would actually test that expertise. A software engineer with strong technical knowledge might design a competition that looks impressive but doesn't actually select for the skills Anduril needs. Luckey, by contrast, consulted with his software leaders to understand what skills matter most, then designed a competition that forces those skills to the surface.

The competition format ultimately reflects this philosophy. There's nothing gimmicky about it. It's not designed to be spectator-friendly in the traditional sense. It's designed to identify engineers who can write code that flies. Everything else is secondary.

Control theory is the most crucial skill for software engineers preparing for autonomous racing, followed closely by sensor data handling and simulation testing. Estimated data.

The Geographic Strategy: Why Ohio Matters

Anduril could have hosted the AI Grand Prix finale anywhere. Choosing Ohio reveals strategic thinking about manufacturing, politics, and regional economic development.

Anduril has significant manufacturing presence in Ohio. The state has a long history of aerospace and defense manufacturing. It has the infrastructure, the supply chains, and the local expertise to support that kind of production. By hosting the competition's most prestigious event in Ohio, Anduril reinforces its commitment to the state. That matters politically and economically. State governments care when companies invest in job creation and economic activity.

There's also a talent strategy embedded in this choice. Ohio has universities like Case Western Reserve, Oberlin, and Ohio State. The state produces engineering talent, though much of that talent traditionally leaves for California or Boston. By hosting a major event in Ohio, Anduril signals that they're willing to work with local talent. They might even establish a regional office or engineering center if the competition generates enough interest.

Finally, there's a practical consideration. Ohio's geographic location makes it relatively accessible from other major U.S. population centers. It's between the East Coast and the Midwest. Teams traveling from California, Texas, or the Northeast don't face extreme travel times. That accessibility increases participation.

The choice to partner with Jobs Ohio, the state's economic development organization, further signals commitment. Jobs Ohio helps coordinate logistics, provide support services, and communicate the importance of the event to local stakeholders. It's an inexpensive way for Anduril to build goodwill while Jobs Ohio gets to demonstrate impact by attracting a major event.

International Participation and Geopolitical Complications

Opening the AI Grand Prix to international competitors is bold. It also creates complications that Anduril is handling with transparency that's unusual for defense contractors.

Russia's exclusion is straightforward. Luckey noted that Russia is actively engaged in invading Europe, and people qualified to compete in such a sophisticated technological competition might be working for Russian military or state organizations. The concern isn't irrational. A Russian competitor winning the race and gaining insights into Anduril's systems could have national security implications. Anduril's exclusion of Russia mirrors the International Olympic Committee's similar decisions.

China's inclusion is more interesting and reveals pragmatism. China produces enormous amounts of autonomous engineering talent. Some of the world's best autonomous systems researchers work in or have connections to China. Anduril could exclude China, but that would mean excluding genuine talent. Instead, Anduril is including Chinese teams but with restrictions. Chinese military employees cannot be offered jobs at Anduril, a limitation that's driven by U.S. law and security regulations rather than company policy.

This approach is simultaneously inclusive and realistic. Anduril isn't pretending geopolitical complications don't exist. They're acknowledging them while still opening doors to talent. A brilliant engineer from China who isn't connected to military organizations might get a job offer. An equally brilliant engineer with military connections won't. That distinction is reasonable and transparent.

The setup also protects Anduril legally. The company is clearly stating the rules upfront. Teams and competitors know the parameters. If a Chinese military employee enters the competition and wins, they know they won't get a job offer. There's no deception. That approach minimizes legal risk while maximizing the talent pool.

International competition also generates valuable PR and market positioning. When journalists report on the AI Grand Prix, they'll mention that it's an international event attracting the world's best talent. That's marketing gold for a defense contractor trying to demonstrate that they compete at the highest levels globally.

Long-Term Vision: Beyond Drones to All Autonomous Vehicles

Luckey made clear that drone racing is just the beginning. Anduril's ambition is to create a series of autonomous racing competitions across multiple vehicle types. The concept would expand beyond quadcopter drones to include underwater vehicles, ground vehicles, and potentially even spacecraft.

This expansion makes sense from multiple angles. First, it diversifies the talent pool. An engineer brilliant with ground vehicles might not be interested in drone racing. An underwater autonomy specialist has completely different skill requirements. By offering competitions across multiple domains, Anduril casts a wider net for talent.

Second, it allows Anduril to evaluate engineers across different specializations. Someone strong in control theory for aerial vehicles might be weaker in robotics for ground systems. By running multiple competitions, Anduril builds a richer picture of different talent pools.

Third, it keeps the series fresh and exciting. Hosting the same drone race year after year would eventually get stale. But a rotating series of different autonomous vehicle types stays innovative. This year's AI Grand Prix is drones. Next year might be underwater vehicles. The year after that, ground robots. Each attracts slightly different competitors and generates fresh media attention.

The vision also signals Anduril's actual business direction. The company isn't just interested in drones. They're building a broad portfolio of autonomous systems across multiple domains. Expanding the racing series reflects that business reality.

The AI Grand Prix starts with 100 teams in April and narrows down to 10 by the November finale. Estimated data based on typical competition formats.

The Talent Market Context: Why Companies Need Bold Recruitment Strategies

Anduril isn't inventing autonomous drone racing in a vacuum. The company is responding to genuine competition for elite engineering talent.

Defense contractors have historically struggled to compete with big tech companies for software engineers. Google, Apple, Microsoft, Meta, and similar organizations can offer enormous salaries, stock options, free meals, and glamorous campus environments. They can also offer work on products that reach hundreds of millions of users. What can a defense contractor offer instead?

Anduril's answer is sophisticated and honest: we offer the most interesting technical challenges in the world. We're building systems that push the boundaries of what's possible with autonomy. We're working on problems that matter existentially for national security and allied military operations. And we're willing to find and recruit talent in unconventional ways.

The AI Grand Prix is that unconventional approach. It's saying: if you're genuinely interested in autonomous systems, prove it. Build something that works. Show us you can compete at the highest level. If you win, we want you on our team.

This approach appeals to a specific type of engineer: someone who cares more about technical excellence than prestige or immediate financial maximization. It appeals to people who find the autonomy problem genuinely fascinating. And it creates self-selection where the best candidates volunteer themselves for competition.

Anduril is also competing against other defense contractors, particularly those like Aurora Flight Sciences and General Dynamics that have autonomous systems divisions. By running the most prestigious and interesting autonomous racing series, Anduril positions itself as the leader in the space. Engineers want to work for the leading company in their field. The AI Grand Prix helps establish and reinforce that leadership position.

How Universities Are Preparing for Autonomous Racing Competitions

Anduril's announcement that multiple universities have already expressed interest in competing reveals that academic interest in autonomous systems is strong and growing.

Universities approach competitions like this differently than startup teams. They have access to substantial computing resources, mentorship from faculty experts, funding from research grants, and the ability to leverage student interest to build dedicated teams. A competitive university robotics program might have 20-30 students working on a single competition over the course of several months.

Major universities with strong robotics programs have already begun developing autonomous drone platforms for other competitions. The FIRST Robotics Competition and similar programs have trained entire generations of engineers in hardware design, software development, and team coordination. Students graduating from those programs are natural candidates for the AI Grand Prix.

Universities are also investing in autonomous systems research specifically. Departments of aeronautics, computer science, and electrical engineering all have faculty researching autonomous flight, control systems, and machine learning for robotics. A drone racing competition is perfect for channeling that research into a competitive format.

The academic angle also matters for Anduril's brand positioning. If prestigious universities are investing resources in competing, that signals the competition is serious and legitimate. Academic participation lends credibility in ways that money alone cannot.

Universities are also more likely to produce teams that focus on elegant, theoretically sound solutions rather than ad-hoc fixes. A university team might implement formal control theory approaches, optimize code for efficiency, and document their methodology carefully. That produces engineers better prepared for serious defense tech work.

The Security and Vetting Process for Competition Winners

While Luckey made clear that winning the competition doesn't automatically guarantee a job, the vetting process for winners is notably streamlined compared to traditional defense contractor hiring.

All candidates still need to pass background checks. For defense contractors, background investigations are standard and thorough. The government requires security clearances for anyone accessing classified information or contributing to classified projects. That vetting process takes time and costs money, but it's non-negotiable.

However, competition winners skip the lengthy technical interview process. They've already demonstrated their technical skills publicly. What remains is personality assessment, communication skills evaluation, and security screening. Those elements still matter because someone brilliant but unable to work with others creates problems. But they're faster and less intimidating than traditional interviews.

Anduril's structure also shows sophistication about how to attract top talent. Many elite engineers are turned off by traditional interviews. They find multiple rounds of technical questions tedious and sometimes irrelevant to actual job performance. A competition-based selection process appeals to people who find that format more enjoyable and meaningful. You get evaluated on actual capability rather than interview performance, which doesn't always correlate.

The streamlined vetting process also helps Anduril move quickly. The traditional hire-to-start timeline for a defense contractor can stretch six months or longer due to background checks and security clearances. Even a slightly faster process saves time and money. Getting talented engineers on board faster matters when you're competing in a fast-moving market.

Luckey's transparency about the vetting process also builds trust. He's not pretending the competition is the whole hiring process. He's explaining exactly how it fits into Anduril's overall recruitment strategy. That honesty appeals to engineers who appreciate clarity.

Ohio's manufacturing presence and political/economic impact are key reasons for hosting the AI Grand Prix there, alongside talent strategy and geographic accessibility. Estimated data.

How Software Engineers Can Prepare for Autonomous Racing

If you're considering competing in the AI Grand Prix or similar events, here's what actually matters for preparation.

First, understand control theory. Autonomous flight is fundamentally a control problem. You're managing multiple simultaneous variables (pitch, roll, yaw, throttle) to achieve desired outcomes (speed, altitude, trajectory). Control theory provides the mathematical framework for doing this elegantly. Getting basics right matters more than complex machine learning tricks.

Second, learn to work with sensor data that's noisy and imperfect. Real drones don't have perfect information about their position, velocity, and orientation. Sensors have noise. Latency exists. You need algorithms robust enough to work despite that imperfection. Kalman filters and similar sensor fusion techniques are your friends here.

Third, optimize for real-time performance. Your code will run on embedded systems with limited computing power and specific clock rates. An algorithm that runs in a second on your laptop might not work on drone hardware. You need to understand computational complexity, efficient data structures, and hardware constraints.

Fourth, test extensively in simulation before hardware. Most competitive teams develop in a simulator like Gazebo or similar robotics simulation platforms. They iterate rapidly in software, then move to hardware only once algorithms are proven. This saves expensive drone crashes and accelerates development.

Finally, understand your platform deeply. Whether you're using Neros Technologies drones or building custom hardware, you need to understand the exact mechanical properties, sensor configurations, and communication protocols. Every hardware quirk affects software design.

The Business Model: Why Anduril Invests in Racing

Some might wonder whether an autonomous drone racing series is a good business investment for a defense contractor. From a strictly financial perspective, it probably isn't. Running a major international sporting event costs money. Offering jobs to winners costs money. The returns are indirect.

But Anduril isn't optimizing for direct financial return. They're optimizing for long-term strategic position. Building the most prestigious autonomous racing series in the world establishes Anduril as the leader in autonomous systems. That positioning affects customer perception, employee recruitment, investor confidence, and partnership opportunities. All of those have indirect financial value that likely exceeds the competition's direct costs.

Think of it like sports sponsorships at scale. Major companies spend millions sponsoring sports teams and leagues not because the financial return is direct, but because brand positioning matters. Anduril is doing something similar but with a competition they created and control entirely.

The competition also generates valuable data. Watching how different teams approach the same problem teaches Anduril about software engineering approaches, algorithm design patterns, and potential solutions to problems they're working on internally. Some winning algorithms might be useful internally, or at least inform internal development.

There's also a recruiting funnel effect. Not every competition participant will get a job offer. But some will. More importantly, participants who don't get hired will remember Anduril as the cool company that runs the coolest competition in their field. Some of those people will join Anduril later, or recommend the company to others. That long-term brand effect is valuable.

Comparison with Traditional Tech Company Recruitment Approaches

How does Anduril's autonomous racing approach compare to traditional tech company recruitment?

Google, Facebook, and similar tech giants historically relied on recruiting from top universities, attending career fairs, and running online coding competitions. They compete on salary and prestige. "Come work at Google" is inherently attractive because Google is famous and pays well.

Anduril can't compete on pure salary or prestige. It's not as famous as Google, and defense contracting has less cultural cachet than consumer tech. But Anduril can compete on opportunity. The company is working on genuinely hard technical problems that matter at global scale. An engineer who helps build autonomous systems that protect allied military forces might find that more meaningful than optimizing ad serving algorithms.

Anduril's competition-based approach also allows them to recruit from outside traditional channels. Someone brilliant but operating outside university systems or traditional tech company pipelines can compete. That expands the talent pool and potentially finds people that traditional recruiting would miss.

Competition-based recruiting also attracts a different personality type. People who spend months developing autonomous flight algorithms and then compete publicly are demonstrating something about their values. They care about technical excellence, challenge, and proving capability. Those personality traits correlate well with success in defense tech.

Traditional tech companies are increasingly adopting similar approaches. Amazon, Microsoft, and others have started hosting competitions and challenges. But Anduril's autonomous racing series is more sophisticated because it combines competition with actual business operations. Winners don't just get money. They get jobs. The competition directly feeds the hiring pipeline.

Estimated data shows that competition-based hiring can reduce the vetting process duration by half compared to traditional methods, facilitating quicker onboarding of talent.

What's Next: Scaling the Vision

Luckey's vision extends far beyond the first AI Grand Prix. He's explicitly discussed expanding to underwater autonomous racing, ground vehicle racing, and potentially spacecraft autonomy competitions.

Each expansion requires different expertise. Underwater autonomy is fundamentally different from aerial autonomy. Buoyancy, pressure, communication, and power challenges are completely different. But the underlying principle is the same: can your software make an autonomous vehicle compete and win?

Ground vehicle racing introduces different challenges again. Wheeled robots on land face grip, traction, and terrain challenges that aerial vehicles don't. But they move in two dimensions instead of three, simplifying some problems.

The vision to eventually include spacecraft autonomy is genuinely ambitious. Space robotics involves extreme constraints: limited computational power, latency measured in minutes, and failure consequences that are catastrophic. An algorithm that fails racing a drone means a crash and a rebuild. An algorithm that fails a space robot might mean losing a multi-billion-dollar asset. But the fundamental problem is the same.

Expanding the series across multiple domains serves multiple purposes. It keeps the brand fresh and exciting. It attracts different talent pools. It signals Anduril's actual business breadth. And it creates a pathway where engineers can compete in multiple events, building deeper connections to the company.

The series also positions Anduril to influence industry standards. Once you're running the most prestigious autonomous racing league in the world, you influence what problems matter, what solutions are respected, and what engineering approaches are valued. That soft power affects the broader industry.

The Regulatory and Legal Framework

Running an international drone racing competition involves navigating complex regulatory environments.

Drone operations in the United States require FAA approval. Flying aircraft, even small autonomously controlled ones, in U.S. airspace requires licenses, waivers, and adherence to specific regulations. Anduril will need special authorization to run races in Ohio. That's almost certainly attainable for a major defense contractor, but it requires navigating bureaucracy.

International participants face even more complexity. Different countries have different drone regulations. Someone shipping a custom autonomous drone from India to compete in Ohio faces customs regulations, import restrictions, and potentially export controls on technology.

The fact that Anduril is explicitly excluding Russian participants suggests they've thought through sanctions and export control issues. The government cares about U.S. technology, including autonomous flight algorithms, reaching countries subject to sanctions or export controls. By excluding Russia, Anduril avoids potential legal complications.

Luckey's transparency about the vetting process also suggests Anduril has consulted with legal experts. The company is carefully structuring the competition to comply with regulations, manage liability, and minimize legal risk.

The partnership with the Drone Champions League likely brings expertise in navigating these issues. The DCL has been running international drone events for years and understands the regulatory landscape.

Key Takeaways: What Anduril's Approach Reveals About Future Recruitment

The AI Grand Prix isn't just a clever recruiting stunt. It's revealing about where defense tech is headed and how companies will compete for talent in coming years.

First, traditional recruiting is becoming insufficient. Simply posting a job and interviewing candidates works less well for super-specialized positions. Companies are moving toward evaluation methods that actually test capability on the job.

Second, recruiting increasingly blurs with marketing and brand building. An international autonomous racing series isn't just hiring. It's positioning Anduril as the leader in a field. It's signaling to customers, investors, employees, and the market that Anduril is the place where autonomy expertise lives.

Third, companies that can create compelling opportunities attract better talent than companies that simply offer competitive salaries. An engineer who gets to work on genuinely hard problems with the world's best colleagues while competing at the highest levels is more excited about the prospect than someone offered $50,000 more in base salary at a different company.

Fourth, international talent competition is real. Anduril is explicitly opening itself to engineers worldwide. That reflects confidence that autonomy talent exists globally and that Anduril can attract it. Companies that limit themselves to recruiting in home markets will lose access to the best talent.

Finally, the most interesting companies will be the ones that can blur categories. Anduril isn't running just a recruiting competition or just a racing league or just a marketing campaign. It's all three at once. Companies that can create initiatives that serve multiple purposes simultaneously get more value from their investments.

Potential Challenges and Questions

Despite its brilliance, Anduril's autonomous racing series will face challenges.

First, sustaining interest long-term is hard. The first event will be exciting because it's new and prestigious. But can Anduril keep it fresh year after year? Expanding to new vehicle types helps, but the core concept might eventually feel stale to some audiences.

Second, actually hiring competition winners at the scale Luckey envisions requires significant business growth. The company needs to be hiring dozens of autonomous systems engineers annually for the competition to feed substantially into their hiring pipeline. If Anduril doesn't grow hiring demands, the competition becomes less meaningful.

Third, managing geopolitical complications is ongoing. Russia's exclusion is clear, but the gray areas remain complex. What about people from allied nations who've worked with Russian organizations? What about engineers from countries without formal U.S. alliances? The company will face recurring questions about fair access and security concerns.

Fourth, proving the pipeline actually works matters. Luckey says some competition winners will get jobs, but will there be enough winners, and will they actually succeed at Anduril? If competition winners don't work out internally, the competition loses credibility as a recruiting tool.

Finally, maintaining the cutting-edge nature of the competition is important. As more teams compete and learn, the general capability level rises. Anduril needs to keep the challenge genuinely difficult, perhaps by introducing new constraints or more demanding courses.

FAQ

What exactly is the AI Grand Prix?

The AI Grand Prix is an international autonomous drone racing competition created by Anduril where teams write software to control drones without human pilots. Teams compete across three qualifying rounds with the finale in Ohio, competing for a $500,000 prize pool and direct job offers at Anduril, bypassing traditional hiring processes.

How is autonomous drone racing different from traditional drone racing?

Traditional drone racing features human pilots controlling drones through three-dimensional courses using remote controls, similar to Formula One driving. Autonomous drone racing has drones controlled by algorithms and machine learning models written by software engineers. The drones fly themselves based on code, not human input.

Who can participate in the AI Grand Prix?

The competition is open to international teams of software engineers and programmers, with the exception of Russian competitors due to geopolitical concerns. Teams from universities, startups, and independent collectives have expressed interest. Chinese teams are welcome, though Chinese military employees would not be eligible for job offers.

What are the actual prizes for winning?

Beyond the $500,000 prize pool distributed among top teams, the real prize is job offers at Anduril with significantly streamlined hiring processes. Winners bypass the lengthy technical interview cycle and go directly to vetting and security clearances. This represents a genuine pathway into one of the most interesting defense tech companies.

Why did Anduril create this competition instead of sponsoring an existing one?

When Anduril considered sponsoring traditional human-piloted drone races, founder Palmer Luckey realized it contradicted the company's core mission: proving that autonomous systems work. Instead of having humans fly drones, Anduril wanted a competition that tested how well engineers could write software for autonomous flight, aligning with their actual business focus.

When is the AI Grand Prix happening and where?

Qualifying rounds begin in April, with three rounds throughout the year. The grand finale is scheduled for November in Ohio, where Anduril has significant manufacturing operations. The exact course location and detailed dates align with logistics and venue coordination with local partners.

Why does Anduril use Neros Technologies drones instead of their own?

Anduril's drones are optimized for military surveillance and large-scale autonomous operations. Racing requires lightweight, highly responsive platforms designed for extreme maneuvers. Neros Technologies specializes in the small, fast quadcopters perfect for racing. Using the right tool for each job demonstrates organizational maturity and strategic thinking.

What skills do teams need to compete?

Competitors need strong software engineering skills, understanding of control theory, experience with real-time systems, knowledge of sensor fusion and noise handling, and the ability to optimize code for embedded hardware. Experience with robotics, drone development, or autonomous systems helps significantly, but fundamental programming excellence is most critical.

Will winning the competition guarantee a job at Anduril?

Winning demonstrates exceptional capability and gets you serious consideration for employment at Anduril with a streamlined hiring process. However, you still must pass background checks, security vetting, and basic qualification interviews. The company views the competition as a reliable filter but maintains final hiring standards and security requirements.

What is Anduril's long-term vision for autonomous racing?

Anduril plans to expand beyond drone racing to include underwater autonomous racing, ground vehicle racing, and potentially spacecraft autonomy competitions. This multi-domain approach will attract different talent pools, keep the series fresh and innovative, and position Anduril as the leader across all autonomous vehicle categories.

How does this compare to traditional tech company recruiting?

Unlike traditional tech company recruiting based on university recruitment, resume screening, and interview performance, Anduril's approach evaluates capability through demonstrated achievement. This attracts engineers who care deeply about technical excellence and competitive achievement, while avoiding the resume-based biases that traditional recruiting sometimes introduces.

Is this approach sustainable for Anduril long-term?

Sustainability depends on whether the competition remains cutting-edge and whether Anduril maintains sufficient hiring growth to meaningfully employ competition winners. The strategy works if the company continues growing its autonomous systems team and if they continue attracting world-class talent through demonstrated technical excellence.

Conclusion: The Future of Recruitment Meets the Future of Autonomy

Anduril's AI Grand Prix represents something genuinely new in how elite technology companies approach talent recruitment. By creating rather than sponsoring an event, by making autonomy rather than human piloting the centerpiece, and by offering genuine jobs rather than just prize money, Anduril has designed a recruiting system that appeals to exactly the kind of engineer they need.

Palmer Luckey's insight was deceptively simple: if your company's entire reason for existing is proving that autonomous systems work, then your recruitment should test autonomous systems capability. Instead of sitting through interviews answering abstract questions about your coding ability, potential hires prove themselves through public competition. Either your drone flies faster than competitors, or it doesn't. The results are objective and measurable.

That meritocratic approach, combined with the promise of meaningful work on genuinely hard problems at the company pushing autonomous systems further than anywhere else, creates compelling motivation. Top engineers are hungry for challenge and recognition. The AI Grand Prix provides both.

The competition also signals confidence. Anduril isn't worried about competitors seeing their recruitment strategy or learning how their engineers approach problems. They're confident enough in their talent, their systems, and their market position to put their approach on public display. That confidence is itself attractive to the kind of people Anduril wants to hire.

Looking forward, expect other defense and technology companies to experiment with similar approaches. Traditional resume-based recruiting is increasingly questioned by people who understand that past credentials don't reliably predict future performance. Competition-based evaluation is more direct and more defensible. You either shipped working code or you didn't. You either solved the problem or you didn't. There's less room for bias or credential inflation.

The AI Grand Prix also positions Anduril at the intersection of several powerful trends. Autonomy is becoming increasingly important across military and civilian applications. Competition and gamification drive engagement and improvement in ways that traditional organizational approaches can't match. International talent competition is reshaping how companies access expertise. By combining all three trends into a single initiative, Anduril creates something that matters across multiple dimensions.

For engineers considering where to build their careers, events like this matter. They reveal what companies genuinely value and what they're willing to invest in. A company that invests in an international autonomous racing competition is betting heavily on autonomy as their future. They're signaling that they'll invest in talent acquisition and that they'll create environments where technical excellence is recognized and rewarded.

The next few years will reveal whether Anduril's approach actually works as a recruiting channel. If the competition attracts genuinely talented teams, if winners succeed at Anduril, and if the company continues expanding the concept to other vehicle types, then other organizations will certainly follow. We might be watching the emergence of a new standard for how elite technology companies identify and recruit top talent.

Ultimately, the AI Grand Prix is less about drone racing and more about the future of work, talent identification, and how organizations compete for excellence. Anduril didn't invent drone racing. But they might have invented how the most competitive technology companies will recruit their best people.

Related Articles

- Robotaxis Disrupting Ride-Hail Markets in 2025: Price War and Speed [2025]

- Uber's AV Labs: How Data Collection Shapes Autonomous Vehicles [2025]

- Northwood Space Lands 50M Space Force Contract [2026]

- Tesla Autopilot Death, Waymo Investigations, and the AV Reckoning [2025]

- The AI Lab Monetization Scale: Rating Which AI Companies Actually Want Money [2025]

- NTSB Investigates Waymo Robotaxis Illegally Passing School Buses [2025]

![Anduril's AI Grand Prix: How a Drone Racing Contest Became Silicon Valley's Wildest Recruiting Event [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/anduril-s-ai-grand-prix-how-a-drone-racing-contest-became-si/image-1-1769551668071.jpg)