US Semiconductor Market 2025: Complete Timeline & Analysis

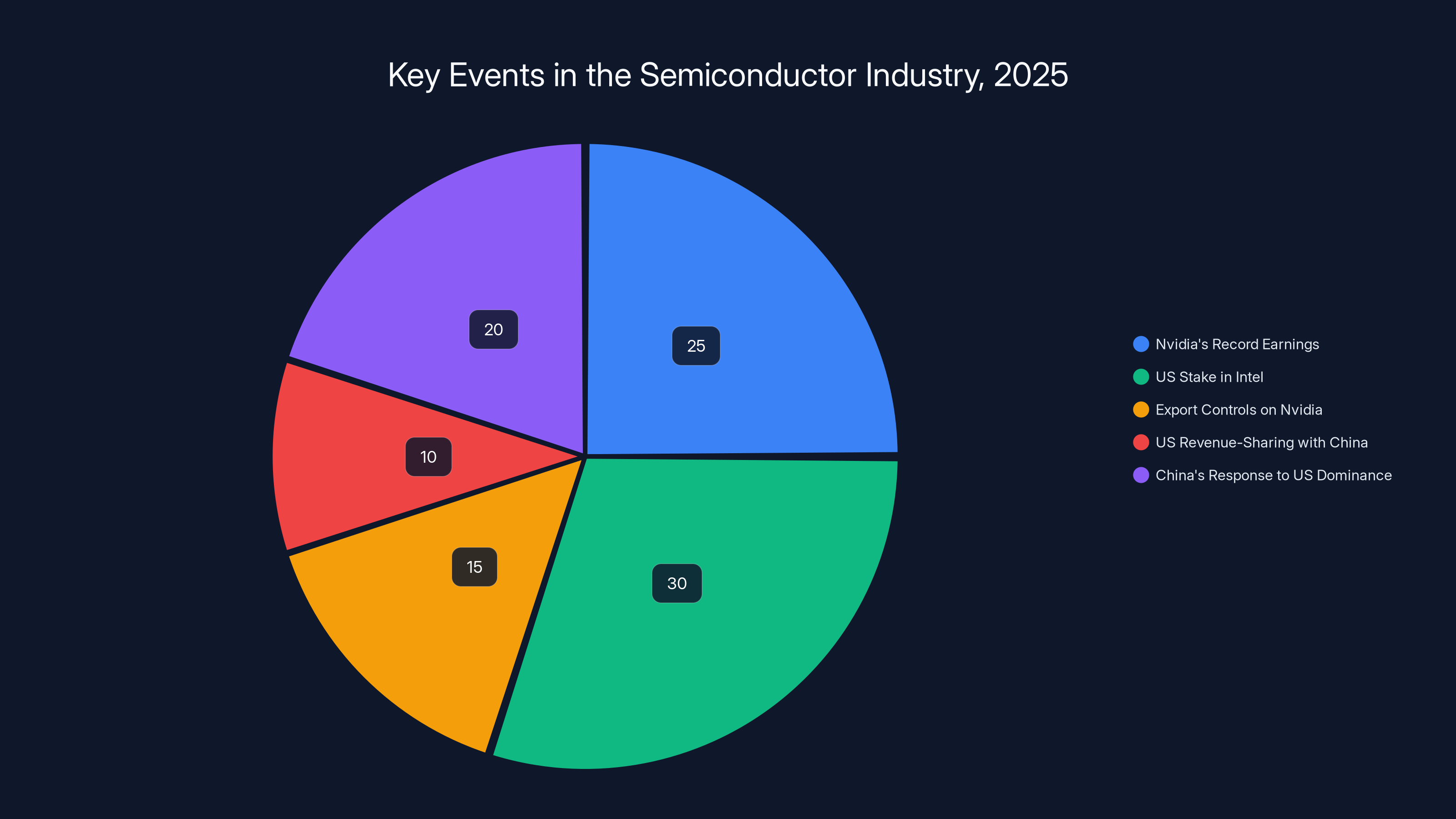

Last year rewrote the playbook for American semiconductor manufacturing. Honestly, 2025 felt less like a normal business year and more like watching an entire industry recalibrate in real time.

We're talking about government equity stakes, dramatic CEO departures, surprise licensing deals worth billions, and policy reversals that happened faster than most companies can file a quarterly report. The semiconductor space has always been capital-intensive and geopolitically charged, but 2025 took both those dynamics to another level entirely.

What made this year different wasn't just that things happened. It was how they happened and what they signaled about where American chip manufacturing is headed. Nvidia crushed earnings records while simultaneously making unexpected moves in asset acquisition. Intel went through a leadership earthquake while the federal government literally became a shareholder. AMD played diplomatic chess with China. And through it all, the Trump administration kept everyone guessing about tariffs, export controls, and what "Made in America" chips actually means.

If you're building on semiconductors, investing in the space, or just trying to understand why your data center costs are spiraling, 2025 is the year that changed the calculus. Here's everything you need to know about what actually happened.

TL; DR

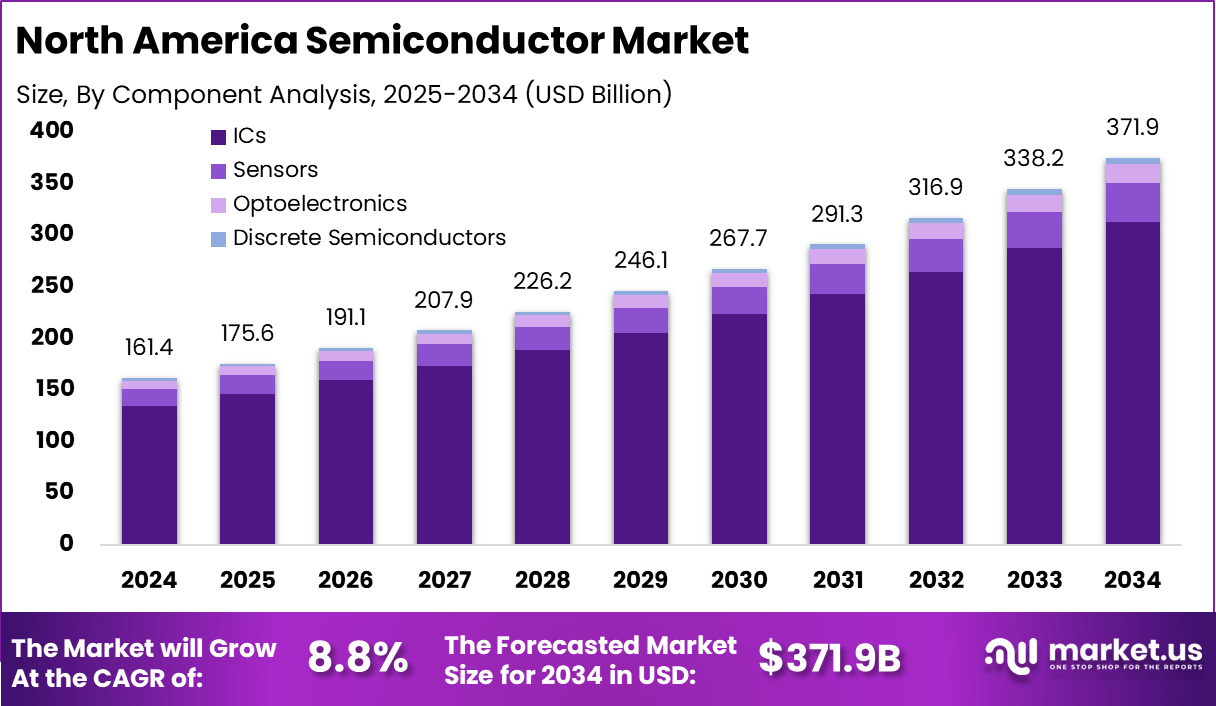

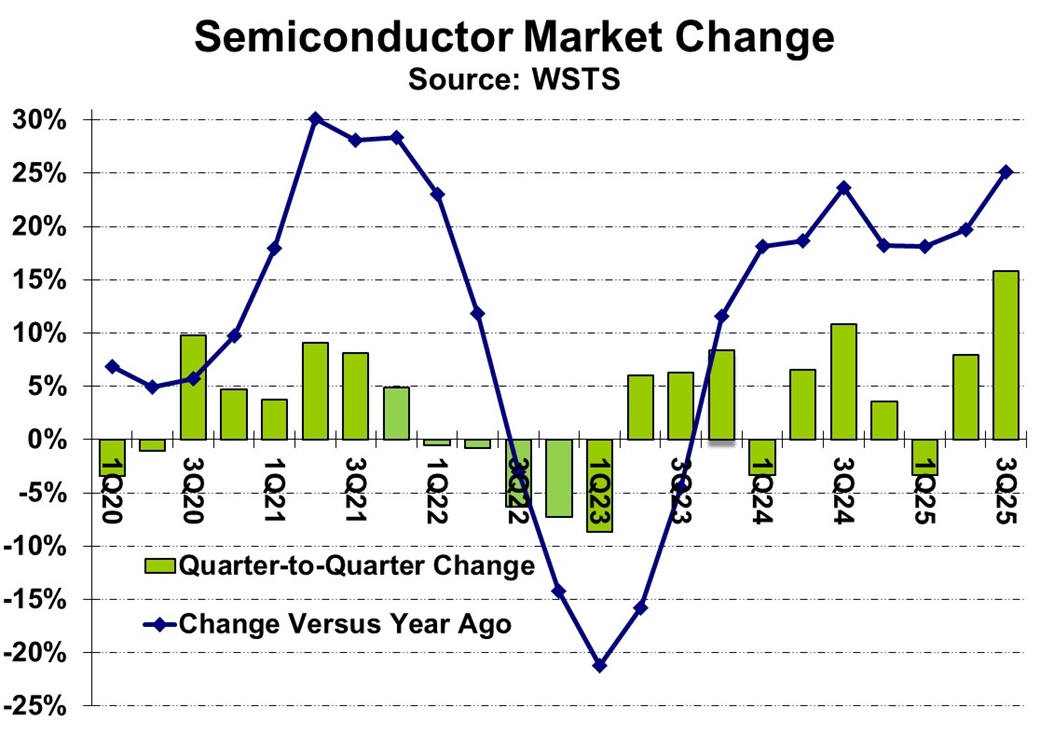

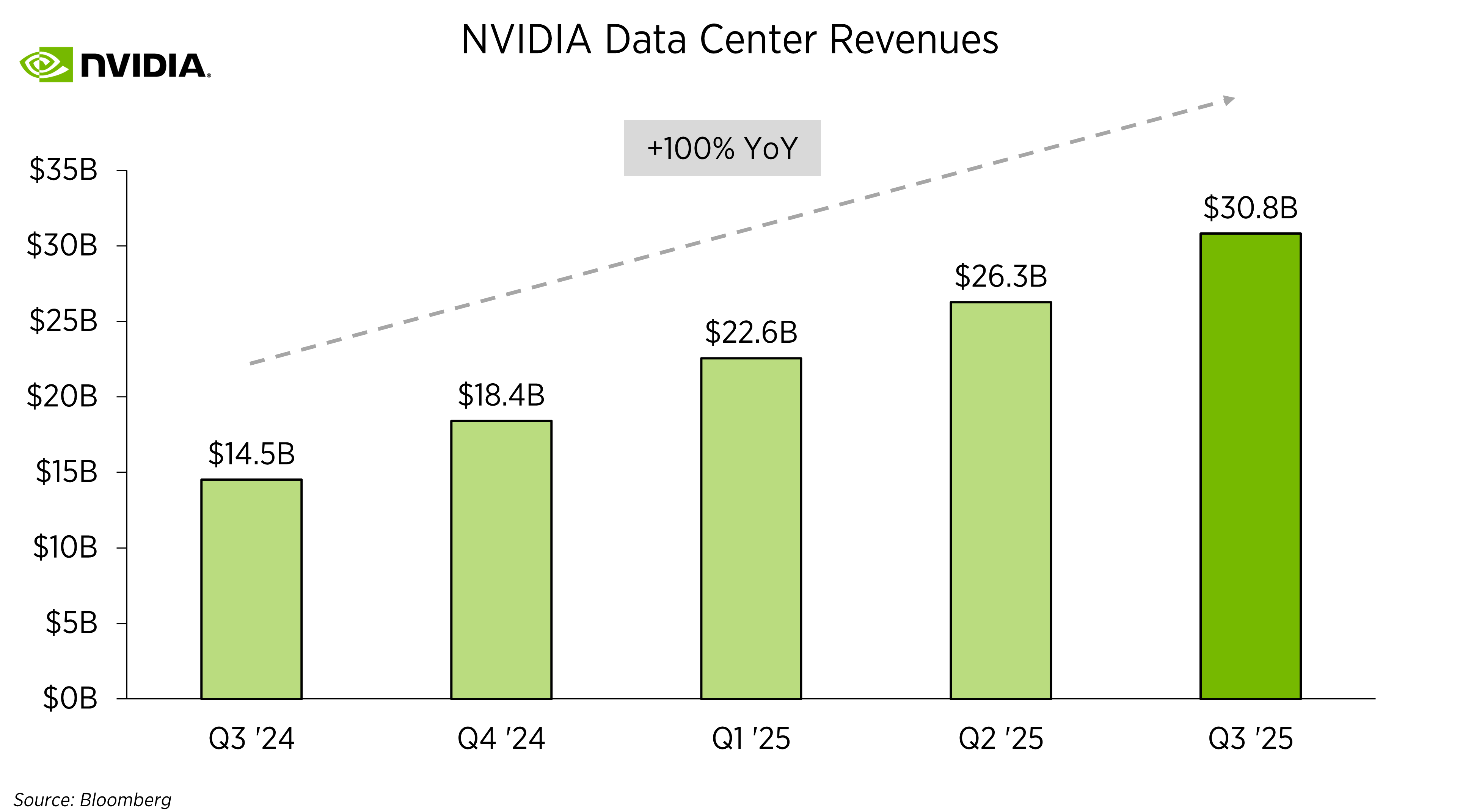

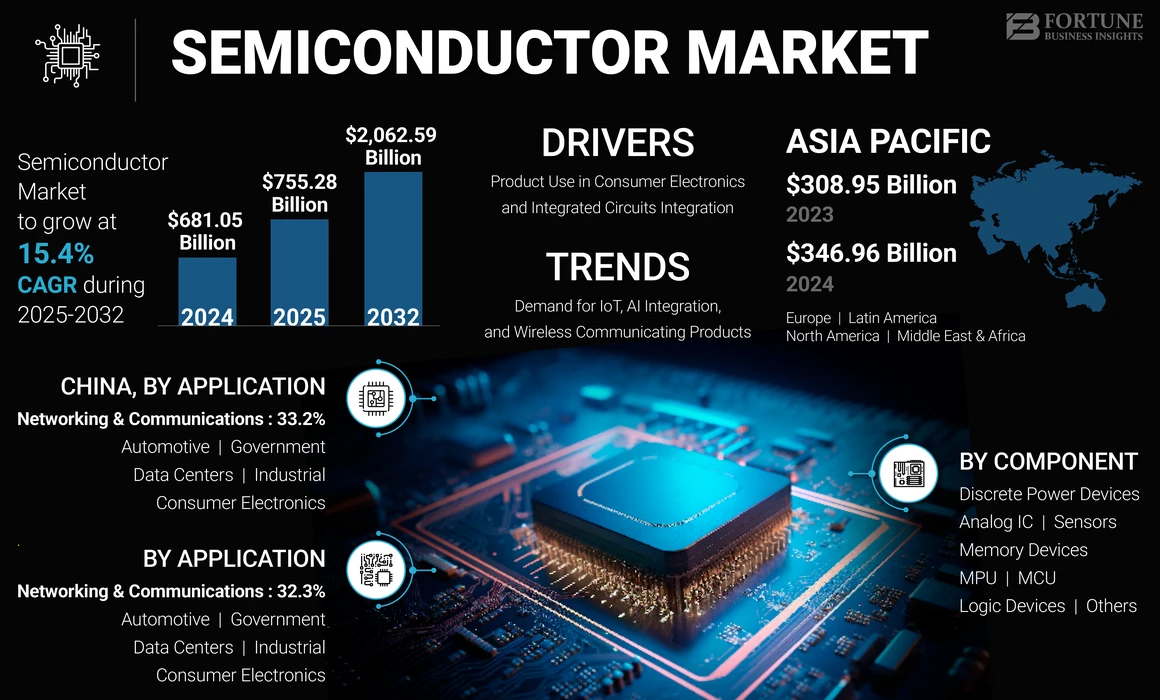

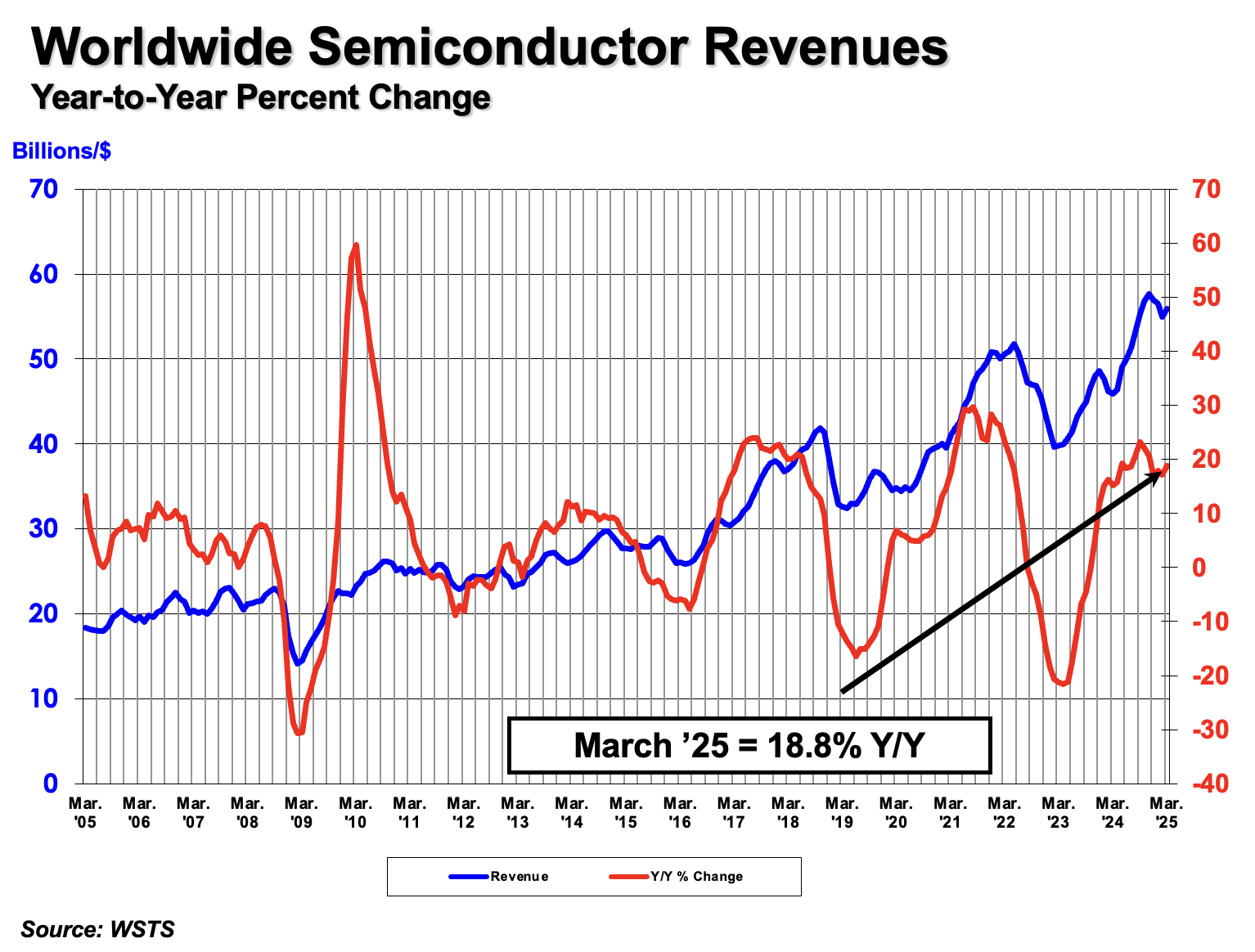

- Nvidia's revenue hit $57 billion in Q3 2025, a 66% year-over-year increase, driven almost entirely by data center demand for AI chips

- The US government took a 10% equity stake in Intel in August, converting grants into ownership with strict performance requirements

- China banned domestic companies from purchasing Nvidia chips in September, forcing a strategic rethink for one of the world's most valuable chipmakers

- Export control policies shifted dramatically, with the Commerce Department reversing course to allow Nvidia's advanced H200 chips into China for approved customers

- Leadership turnover accelerated, with Intel's product chief Michelle Johnston Holthaus departing after 30 years, signaling major strategic reorganization

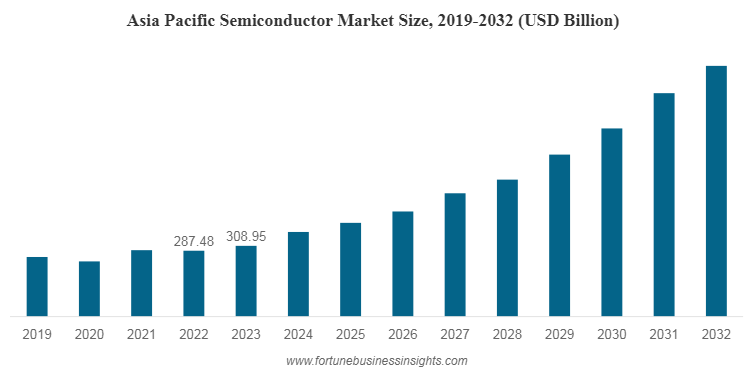

Nvidia's revenue surged by 66% year-over-year in Q3 2023, reaching $57 billion. Projected growth suggests continued dominance in AI chip market. Estimated data for future quarters.

The Nvidia Phenomenon: How One Company Captured the Entire AI Chip Market

The August Revenue Shock That Set the Tone

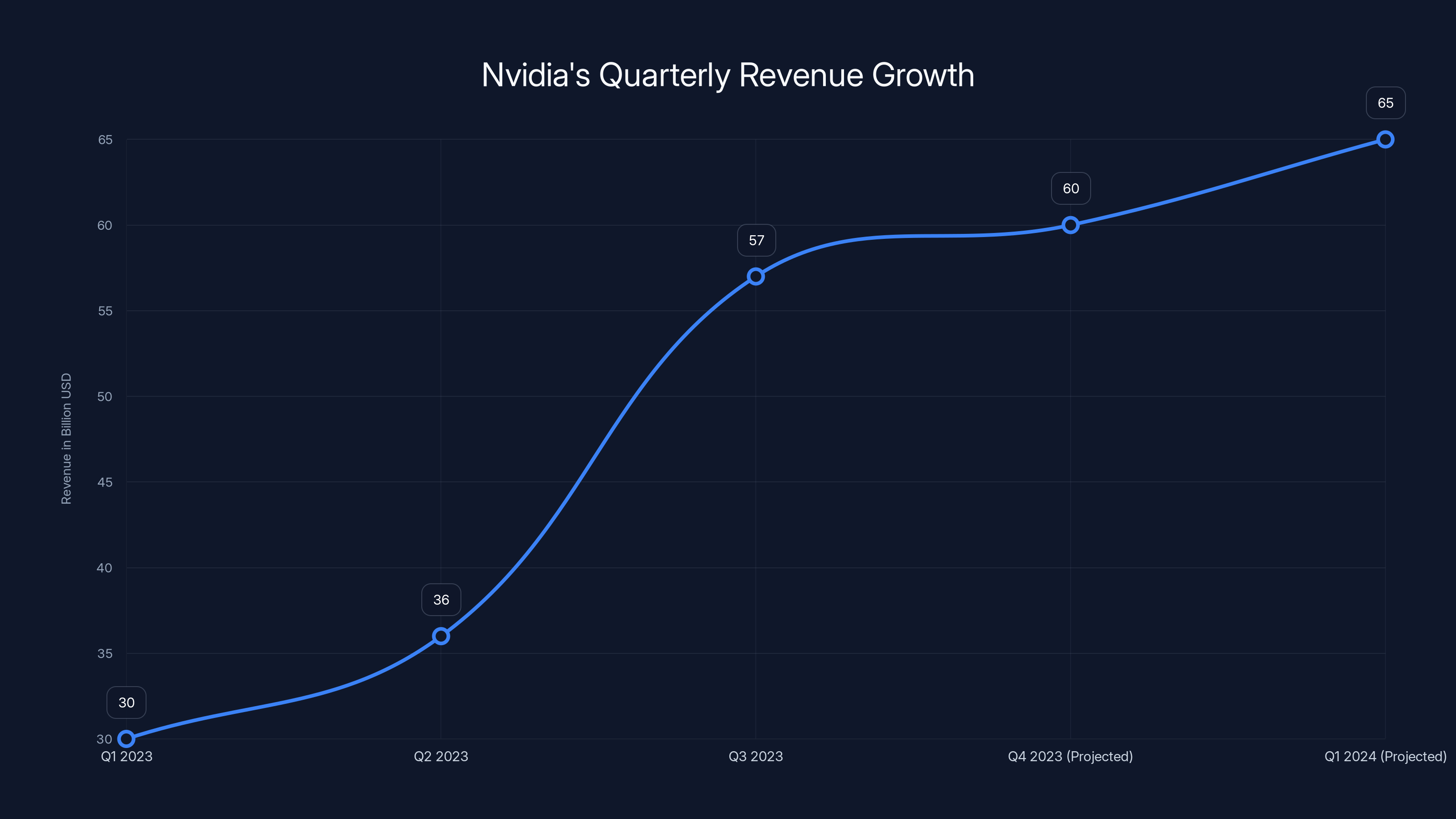

On August 27, Nvidia reported numbers that basically made every other semiconductor company wish they'd pivoted to AI accelerators three years earlier. The company pulled in what felt like an impossibly large revenue number in Q2: dominated by data center sales that grew 56% year over year.

But here's what most people missed at the time. That 56% growth wasn't surprising because demand was hot. It was surprising because it showed exactly how badly every other chipmaker had misjudged the AI acceleration curve. Companies were buying Nvidia GPUs to train models, fine-tune models, serve models, and build entire infrastructure around inference. It wasn't a temporary spike.

The real wake-up call came in Q3, reported in November. Nvidia posted $57 billion in quarterly revenue, a 66% year-over-year increase. Let that sink in. The company essentially printed the total annual revenue of most Fortune 500 companies in a single quarter. Data center revenue drove the majority of this, and what makes this even more remarkable is that most of these chips were selling at premium prices with healthy margins.

Investors weren't just excited. They were genuinely trying to figure out how high this could go. The market started pricing in scenarios where Nvidia's data center business could become a $500 billion annual revenue generator by 2027.

What this meant for the broader semiconductor industry was profound. Every CEO had to answer the same question in earnings calls: why aren't you Nvidia? And the honest answer for most of them was: we didn't see this coming, and now we're playing catch-up.

The Groq Licensing Deal: Nvidia Gets a Strategic Talent Infusion

On December 24, Nvidia made a move that seemed almost anticlimactic compared to the earnings headlines, but was actually incredibly strategic. The company announced a non-exclusive licensing deal with Groq, the AI chip startup that had been making noise about custom inference accelerators.

But the deal wasn't really about the licensing. It was about the people and assets. Nvidia hired Groq's founder and president along with other key employees. The company also bought $20 billion worth of Groq's assets.

This is classic Nvidia playbook. When you're dominant in a market and a scrappy startup emerges with interesting IP or talent, sometimes it's cheaper and faster to acquire the talent and technology than to replicate it internally. Groq had been working on inference optimization, and even though Nvidia's H100 and H200 chips dominate training, inference is becoming increasingly important as more models move into production.

The strategic message was clear: Nvidia was betting that the next phase of AI wasn't just about training bigger models. It was about running those models efficiently at scale. By bringing in Groq's team, Nvidia was essentially hedging its bets and ensuring it wouldn't get outflanked in the inference space.

For Groq's investors and founders, it was a successful exit in a market that was getting increasingly competitive. For Nvidia, it was insurance policy disguised as a business deal.

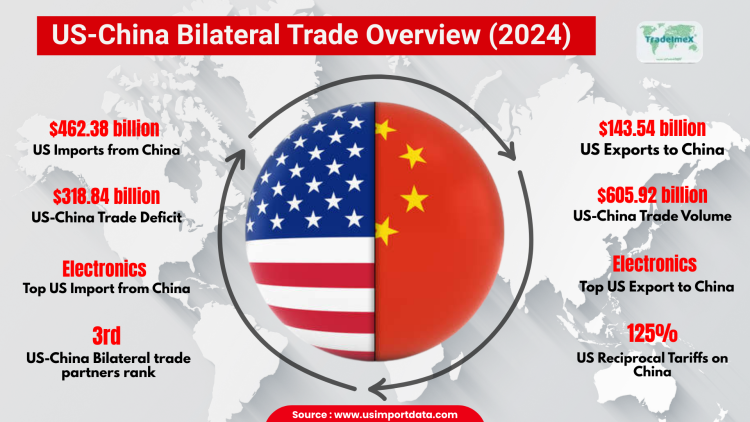

The China Export Control Reversal: Government Whiplash

November 8th brought news that shocked basically everyone following chip policy. After months of restrictions on selling advanced chips to China, the US Department of Commerce announced that Nvidia and AMD could start selling AI chips to China again, with some significant caveats.

The Commerce Department specifically said Nvidia could sell its H200 chips, which are markedly more advanced than the H20 variant (the export-restricted version). The approval came with conditions: only to approved customers, and presumably with ongoing compliance monitoring.

This reversal sent three conflicting signals simultaneously. First, it suggested the Biden administration understood that choking off an entire market was economically damaging to American companies. Second, it implied the US government had calculated that allowing some sales was better than watching customers shift to Chinese alternatives or European chips entirely. Third, it showed that semiconductor policy was being made on a month-to-month basis rather than through any coherent long-term strategy.

For Nvidia, this was genuinely important. China had been a growth market before restrictions tightened. Having a pathway back in, even a limited one, meant the company could potentially recapture some revenue it had lost to policy uncertainty.

But the reversal also created problems. It gave ammunition to critics who said the administration's policies were contradictory. It signaled to chip companies that today's restrictions might become tomorrow's licenses. And it fed into an increasingly chaotic policy environment where nobody knew what the rules would be next quarter.

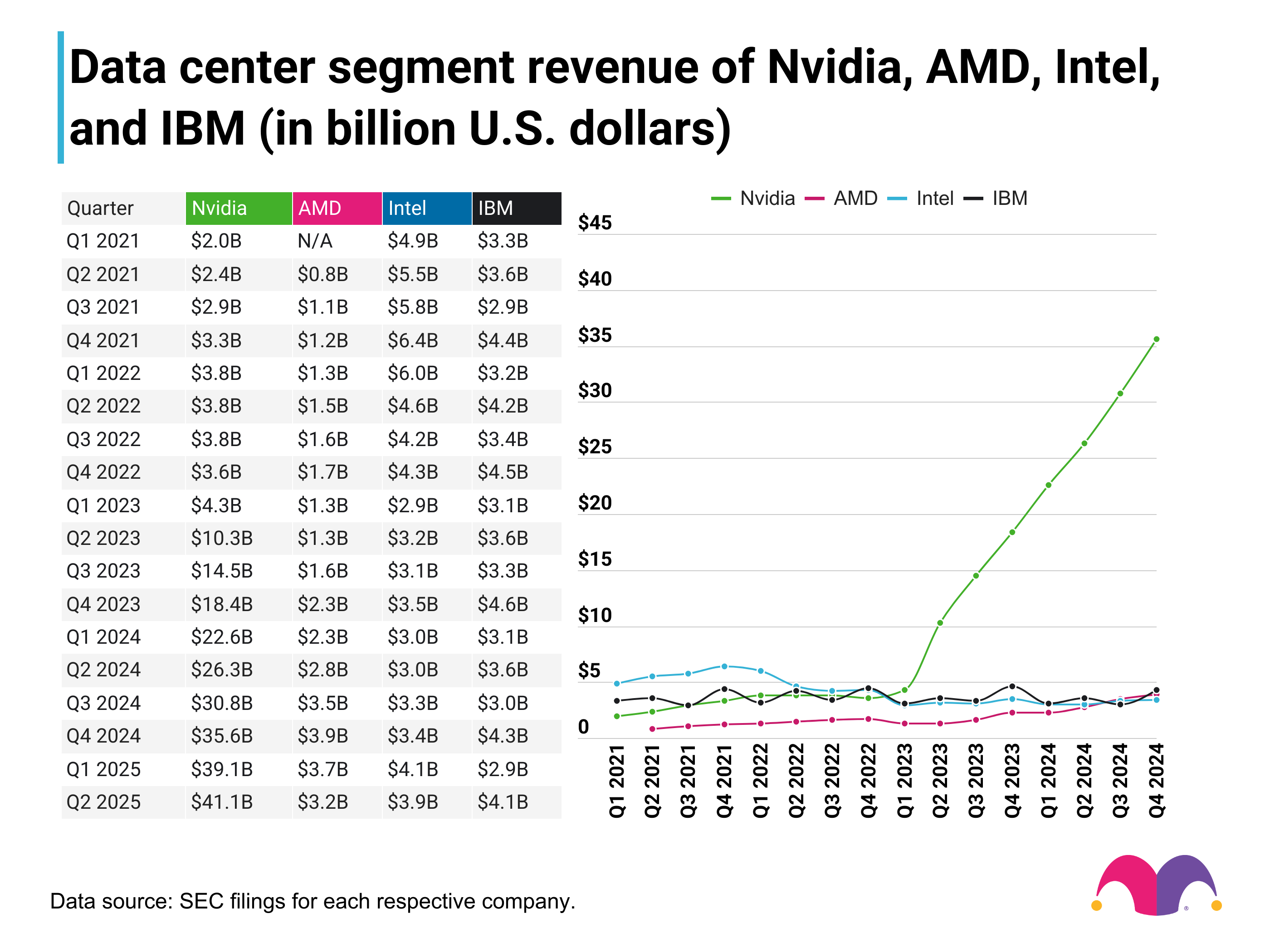

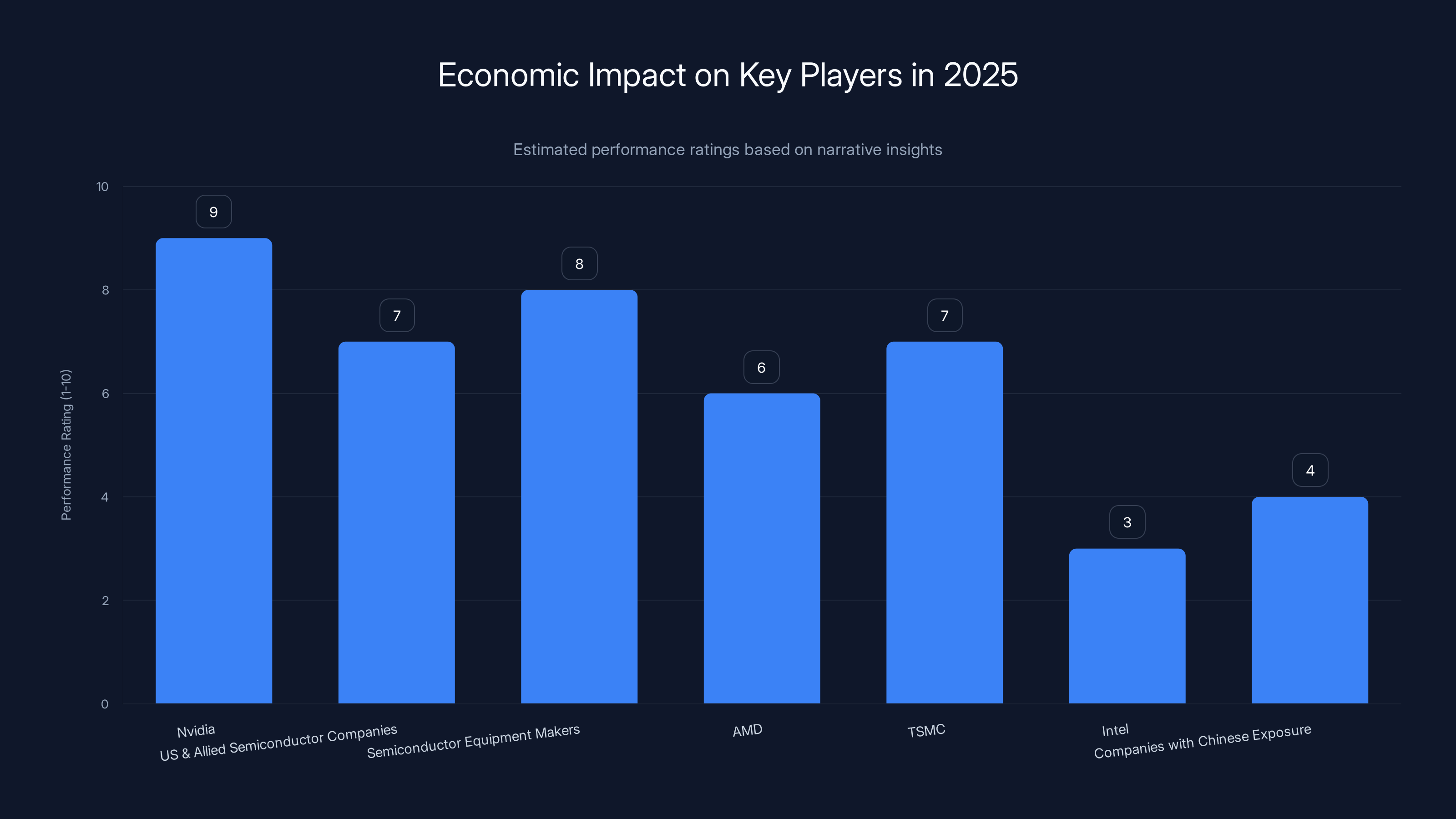

In 2025, the US government's stake in Intel and Nvidia's record earnings were the most impactful events, each contributing significantly to shaping the semiconductor landscape. (Estimated data)

The China Factor: How Beijing Turned Up Pressure on American Chip Dominance

September 17: The Domestic Preference Mandate

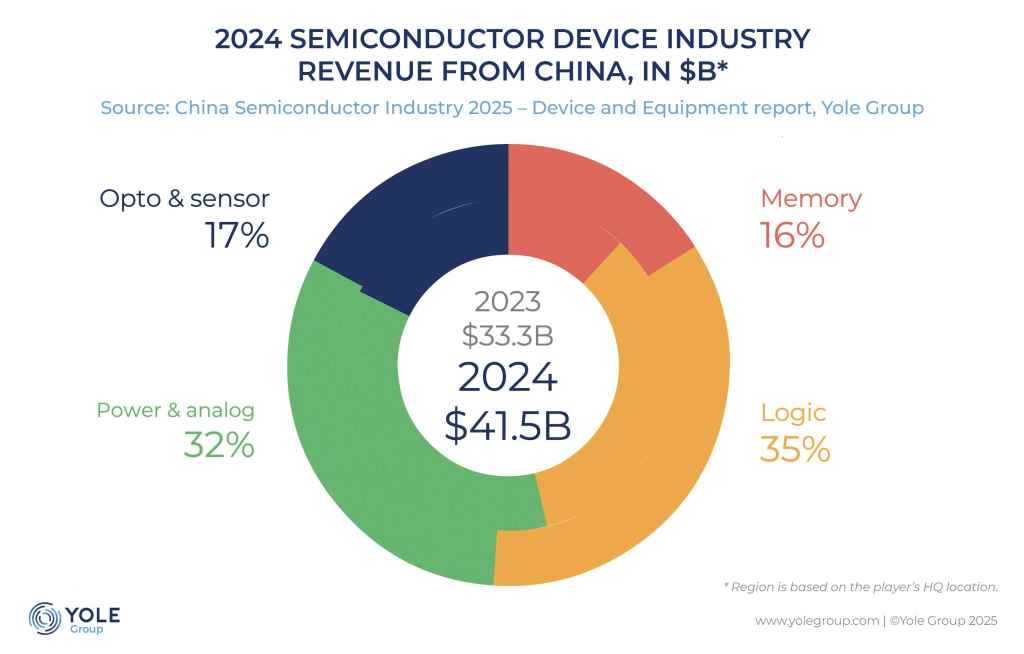

China's response to Nvidia's dominance wasn't to compete head-on. It was to effectively ban the use of foreign chips for important applications.

On September 17, China's Cyberspace Administration issued what amounted to a directive: domestic companies should prioritize Chinese-made chips and avoid buying Nvidia hardware. The order wasn't technically a ban, but in China's corporate environment, directives from government agencies on this topic tend to get followed.

The timing was significant. This came just as Nvidia thought it might be getting back into the Chinese market. The move was essentially China saying: "We understand you're going to sell here, but we're going to make it economically unattractive for anyone to buy."

What this really meant was that Nvidia's addressable market in China had just shrunk significantly. Chinese AI companies and research institutions were going to be pushed toward domestic alternatives like Huawei's Ascend chips or domestic startups. This wouldn't happen overnight, but the direction was unmistakable.

For Nvidia, this was annoying because it cut off a major growth market. For China, it made strategic sense. The country couldn't match Nvidia's engineering capability yet, but it could mandate its own domestic preference. Over time, homegrown alternatives would improve, and by making them mandatory, China was creating a guaranteed market.

September 15: The Antitrust Allegation

Two days earlier, China had already landed another blow. The State Administration for Market Regulation ruled that Nvidia had violated China's antitrust regulations in connection with its 2020 acquisition of Mellanox Technologies.

Mellanox made networking equipment that Nvidia bought partly to better integrate with its GPU offerings. At the time, the acquisition seemed straightforward. Combine GPUs with networking, create better systems, sell more of both.

But China was alleging that the acquisition gave Nvidia anticompetitive advantages. The timing of this allegation, coming just as US policy was opening slightly, felt less like a genuine legal concern and more like diplomatic leverage. China was essentially saying: we can make your life complicated in our market if you don't play ball.

This is how modern trade wars actually work. They're not tariffs on containers anymore. They're antitrust allegations, regulatory reviews, environmental inspections, and policy directives that appear to be about rule-of-law but are really about economic power.

For Nvidia, it meant accepting that doing business in China was going to be perpetually complicated, legally ambiguous, and subject to political winds.

Intel's Leadership Crisis and Government Intervention

August 7-11: The Trump Administration's Public Pressure Campaign

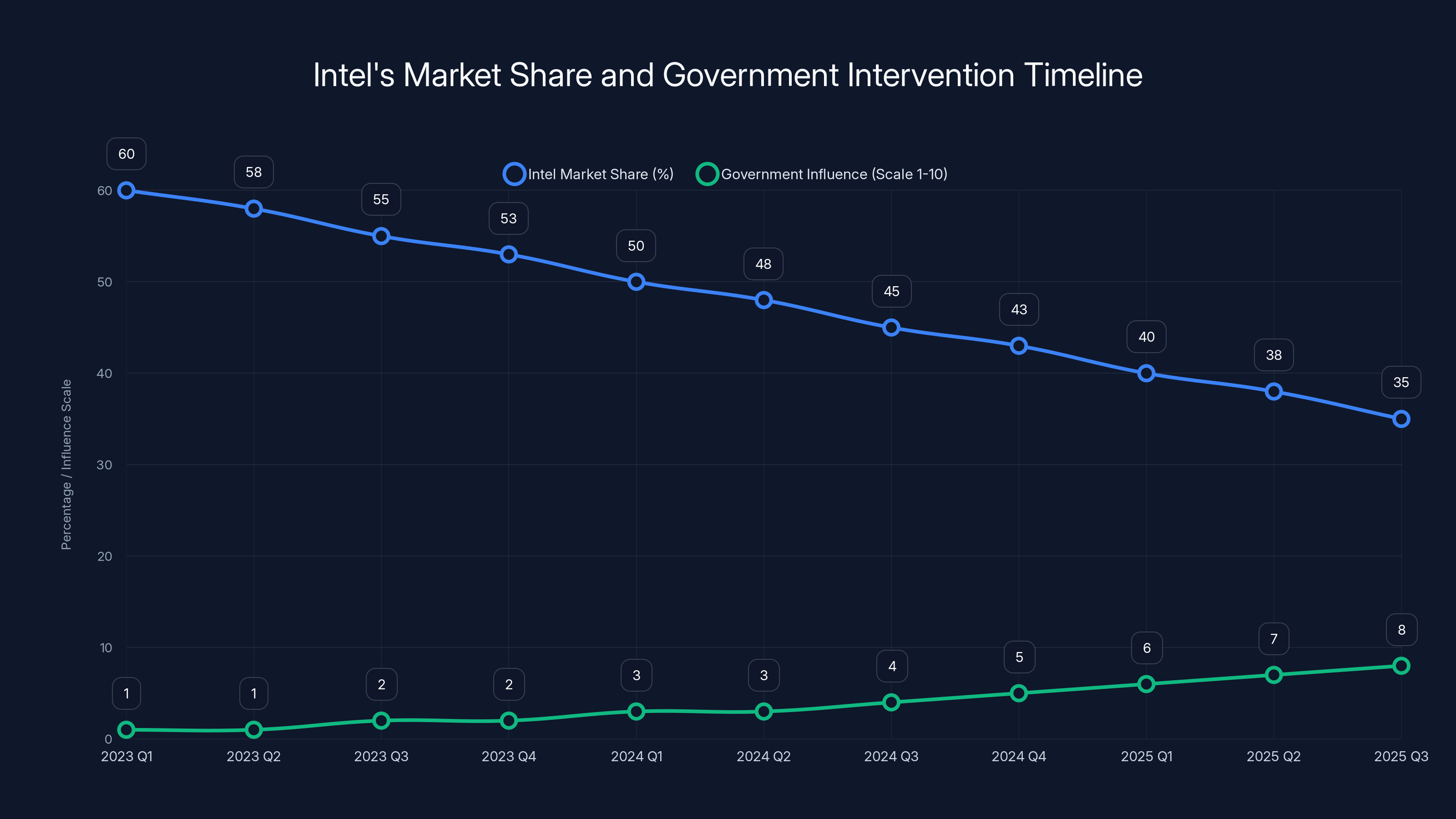

Intel was already struggling before August 2025 hit. The company had missed on technological roadmaps, lost market share to AMD in CPUs, and was burning through capital on new fabs that weren't delivering the performance gains marketing had promised.

Then President Trump decided to make Intel a personal project.

On August 7, Trump posted on Truth Social that Intel CEO Lip-Bu Tan should "resign immediately" due to alleged "conflicts of interest." Trump didn't specify what conflicts, but the implication was clear: Tan had ties to China, and those ties made him unfit to lead an American strategic asset.

The timing wasn't random. Senator Tom Cotton had sent a letter to Intel's board just the day before raising questions about Tan's background and connections.

Then, almost comically, on August 11, Lip-Bu Tan went to the White House to meet with Trump. Both sides called it "productive." Translation: they negotiated how publicly messy this was going to get.

What was actually happening underneath the drama was more interesting. The Trump administration had decided Intel was too strategically important to fail and too badly managed to leave alone. The President wanted a CEO who would do whatever the government wanted regarding domestic manufacturing, supply chain control, and geopolitical positioning.

Tan didn't get fired for cause. But the message was unmistakable: the US government was now calling shots at Intel, and the CEO was going to execute its vision or get replaced.

August 22: The Government Becomes a Shareholder

On August 22, the US government essentially became a venture capitalist, converting existing CHIPS Act grants into a 10% equity stake in Intel. This wasn't a loan. It wasn't a contract. It was ownership.

The deal included penalties if Intel's ownership in its foundry business dropped below 50%. This was crucial because Intel had been planning to potentially sell off or divest its foundry operations. The government was saying: not happening.

What this meant was that Intel couldn't make business decisions as a normal company anymore. The government was a 10% owner with veto power over major strategic moves. This wasn't just unusual. It was unprecedented in modern American tech history.

Think about what this signals. The government had concluded that the private market wasn't going to make Intel successful as a foundry business. So it was going to force the company to stay in the foundry business and fund it with taxpayer equity. This is basically what command economies do.

For Intel employees and investors, it was clarifying in a troubling way. Intel was no longer primarily a market-driven business. It was now partly a government-owned strategic asset.

August 18: Soft Bank's $2 Billion Vote of Confidence (Or Strategic Positioning)

Amid all this chaos, Japanese conglomerate Soft Bank announced it was taking a $2 billion stake in Intel. CEO Masayoshi Son called it "strategic."

This could be read two ways. Optimistically, it's a vote of confidence from a major investor that Intel has a future. Pessimistically, it's strategic positioning to have a seat at the table when the restructuring happens.

Given Soft Bank's history of strategic investments in struggling tech companies, it's probably both. Soft Bank was betting that Intel would either recover under government support or, failing that, would be salvaged by an even larger restructuring where Soft Bank would want a board seat.

September 9: Michelle Johnston Holthaus Departs After 30 Years

On September 9, Intel announced that Michelle Johnston Holthaus, the chief executive officer of Intel Products and a 30-year company veteran, was departing. The official language was "organizational restructuring," but what this really meant was that the old guard at Intel was being replaced.

Holthaus leaving wasn't about performance. She was highly respected in the industry. It was about Intel needing new leadership that would execute the government's vision for domestic manufacturing instead of trying to save the company through product innovation.

The company also announced the creation of a central engineering group, further consolidating decision-making at the top. This is the kind of organizational restructuring that usually precedes either a major turnaround or a slow decline. In Intel's case, with government equity involved, it looked more like preparing the company to execute government mandates.

Estimated data shows Intel's declining market share from 60% to 35% and increasing government influence from 1 to 8 on a scale of 10, highlighting the growing intervention in Intel's operations.

The Broader Policy Landscape: Tariffs, Supply Chain Nationalism, and Uncertainty

September 26: The Tariff Proposal Floats

At the end of September, rumors started circulating about what the Trump administration's semiconductor tariff strategy might look like. The proposal being discussed was wild: semiconductor companies would be required to produce domestically the same volume of chips they export internationally, or face tariffs.

This isn't a traditional tariff. It's a domestic content requirement disguised as trade policy. The logic is semi-sensible from a nationalist perspective: if you're making chips in America, more of them should stay in America.

But economically, this is the kind of policy that usually backfires. It creates supply chain inefficiencies, pushes up prices, and encourages companies to move manufacturing to countries without such requirements. It's exactly the kind of policy that sounds good in a campaign speech but tends to create unintended consequences when actually implemented.

The fact that this proposal was even being floated showed that the semiconductor industry had become a vehicle for broader nationalist economic policy. Companies weren't just competing on technology anymore. They were competing in a policy environment where the rules themselves were becoming more important than innovation.

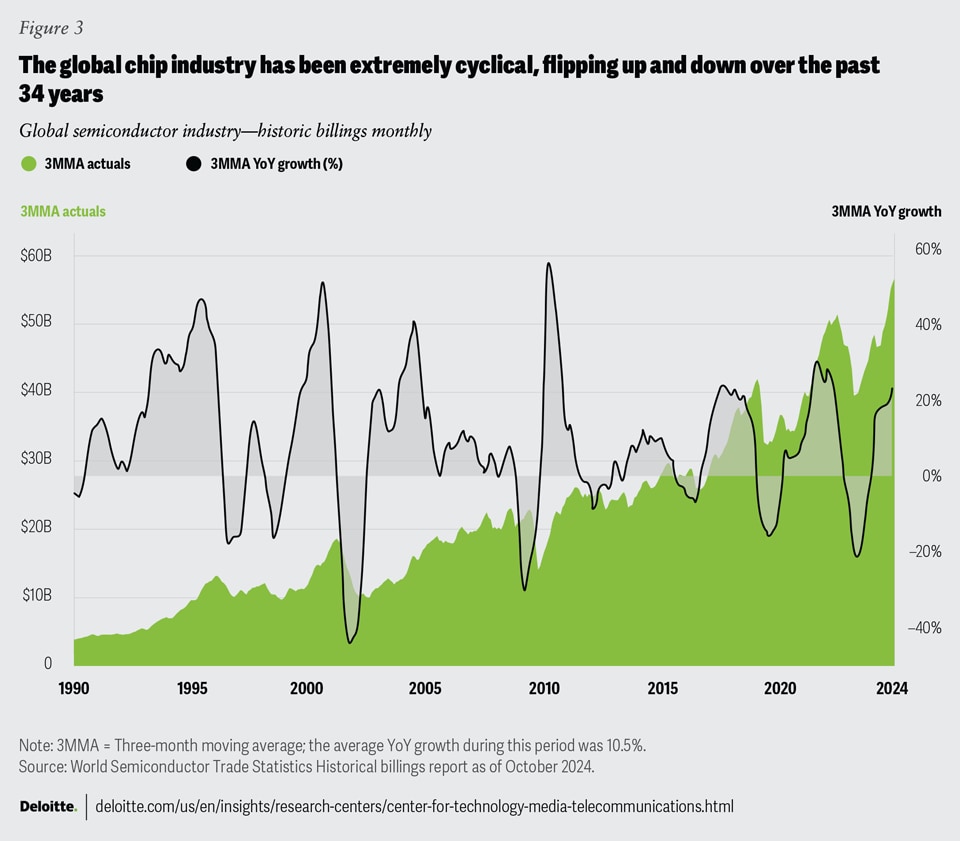

The Death of Business as Normal

What made 2025 unique for the semiconductor industry wasn't any single event. It was that every major decision was now filtered through geopolitical and policy considerations instead of purely commercial logic.

Nvidia wasn't just competing with AMD. It was navigating US export controls, Chinese bans, and government mandates. Intel wasn't just fixing its engineering problems. It was executing government policy with a federal shareholder sitting on the board. AMD was making diplomatic deals instead of just engineering better chips.

This is what happens when an industry becomes strategically important during a period of heightened geopolitical tension. The rules of competition change. Governments become players. Markets stop working the way economics textbooks say they should.

The AMD-China Deal: Negotiating Complexity

August 12: The Revenue-Sharing Arrangement

On August 12, AMD and Nvidia announced they'd struck a deal with the US government to get licenses to sell AI chips into China. The terms were interesting: both companies agreed to pay the US government 15% of revenue from Chinese chip sales.

This is genuinely novel. It's not a tax. It's not a tariff. It's a government taking a direct cut of revenue from sales in a particular country. It's almost like the government decided it wanted to be an equity partner in exports.

For AMD, this was significant because the company needed Chinese revenue. AMD's data center business was primarily serving US customers, and having access to China was important for scale. Paying 15% to the government was expensive but better than nothing.

For Nvidia, it was actually an interesting development because it formalized something that had been unclear: exactly what the rules were for selling into China. At least now the company knew the costs and requirements.

But the broader implication was troubling. It showed the government was willing to use its power to extract economic rents from companies doing business in restricted markets. This creates perverse incentives where companies might be better off not selling into certain countries at all rather than giving up 15% of revenue.

Nvidia emerged as the top performer in 2025, while Intel and companies with Chinese exposure faced significant challenges. Estimated data based on narrative insights.

Intel's Technical Progress: Panther Lake and Arizona Manufacturing

October 9: The 18A Process Finally Arrives

In the middle of all the leadership chaos and government intervention, Intel actually had a technical achievement worth celebrating. On October 9, the company announced Panther Lake, a new processor in the Intel Core Ultra family that would be the first built on Intel's 18A semiconductor process.

Panther Lake was going to be exclusively manufactured at Intel's Arizona fab. This was important because it showed that Intel was actually making progress on the manufacturing side, even as the company imploded organizationally.

The 18A process had been years in development and was Intel's attempt to catch up with TSMC and Samsung on manufacturing capability. Getting it into production was a genuine engineering accomplishment, even if it wasn't going to save the company overnight.

The Arizona fab connection was also significant politically. This was American manufacturing in action, which meant government support would continue flowing. From a policy perspective, Intel having successful production at Arizona was valuable regardless of whether the chips were actually competitive.

But here's the thing: announcing a new processor while your CEO is being pressured to resign and the government is taking equity stakes doesn't exactly inspire confidence. The market barely reacted. The news got buried under headlines about leadership chaos and policy uncertainty.

What Panther Lake really represented was Intel trying to compete on the one axis that still mattered: manufacturing capability. The company had mostly given up on being more innovative than TSMC. It was going to compete on being American and having government support.

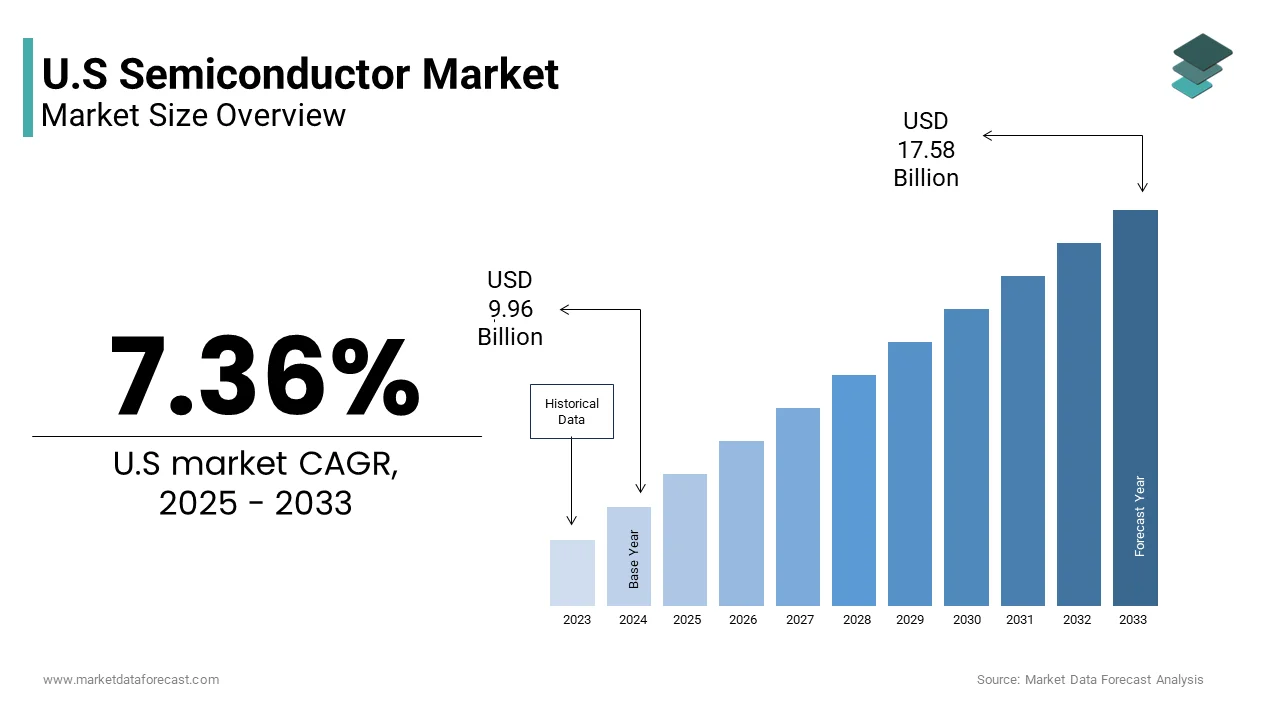

The Semiconductor Supply Chain in 2025: Reshuffling Global Dependencies

Why Vertical Integration Became Fashionable

Throughout 2025, one trend became unmistakable: companies that wanted to control their semiconductor destiny were integrating vertically. This meant designing chips and making them in-house instead of relying on contract manufacturers.

Apple was doing this. Microsoft was doing this. Amazon was doing this. The logic was clear: if your business depends on access to cutting-edge chips and geopolitical tensions are threatening supply chains, you want to own the supply chain.

For the traditional semiconductor companies like Nvidia, Intel, and AMD, this created a weird dynamic. These companies had built their businesses on designing chips and using contract manufacturers. Now those contract manufacturers were starting to compete with them by working directly with the tech giants.

TSMC found itself in an interesting position. The company was too important and too good at what it did to replace, but increasingly the largest customers wanted to reduce dependency on it. So TSMC started investing even more heavily in capacity and technology, knowing that the cost of losing a major customer would be existential.

The Supply Chain Becomes Geographically Fragmented

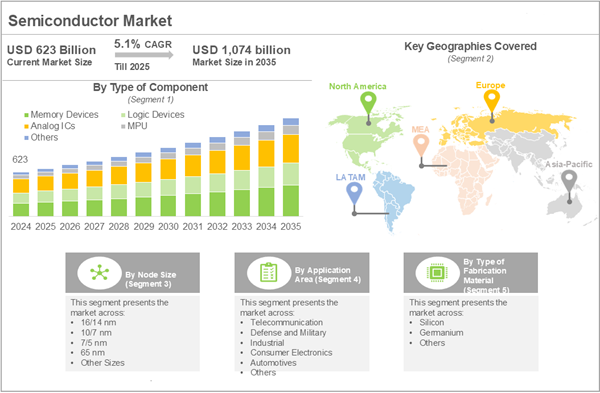

By the end of 2025, it was clear that the integrated global semiconductor supply chain of the 2010s was being replaced by something more fragmented and regionally duplicated.

The US wanted fabs making advanced chips domestically. So the government was funding Intel and other manufacturers. Europe wanted independence from Taiwan. So the EU was investing in fabs and design capability. China wanted self-sufficiency. So Beijing was pouring money into domestic alternatives.

This is economically inefficient compared to the old model where Taiwan made the best chips and everyone else bought from them. But efficiency wasn't the priority anymore. Security and resilience were.

What this meant for the industry was higher costs, slower innovation in some areas, and a more complex business environment. Companies now had to think about which chips could be made where, which suppliers they could depend on, and what geopolitical risks might disrupt their manufacturing.

This chart illustrates the estimated impact of major events in the semiconductor industry during Q3 2025, with Nvidia's revenue growth and China's ban on Nvidia chips having the highest impact.

Looking Forward: What 2025 Revealed About 2026 and Beyond

The Nationalization of Semiconductors

2025 revealed that the era of truly global, commercially optimized semiconductor supply chains is ending. What's replacing it is a more nationalist, government-directed system where countries are trying to ensure domestic capability in critical technologies.

This is expensive and inefficient, but it's also probably inevitable when a technology is as strategically important as semiconductors and geopolitical tensions are this high.

For companies in the space, it means accepting that business decisions will increasingly be constrained by government policy. For customers, it means accepting higher costs and possibly worse performance as supply chains become redundant and fragmented. For countries, it means massive government investment in domestic semiconductor capacity.

The Policy Uncertainty Is the Real Story

What struck anyone paying attention in 2025 was how quickly policies changed and how contradictory they often were. Export controls would tighten, then reverse, then tighten again. Government support would be announced, then detailed in ways that made companies question whether it was actually helpful. Tariffs would be threatened, then implemented, then modified.

This uncertainty is actually more damaging to the industry than any specific policy would be. Companies invest in long-term capacity planning. They need predictability. When the policy environment changes month by month, companies can't plan. They just react.

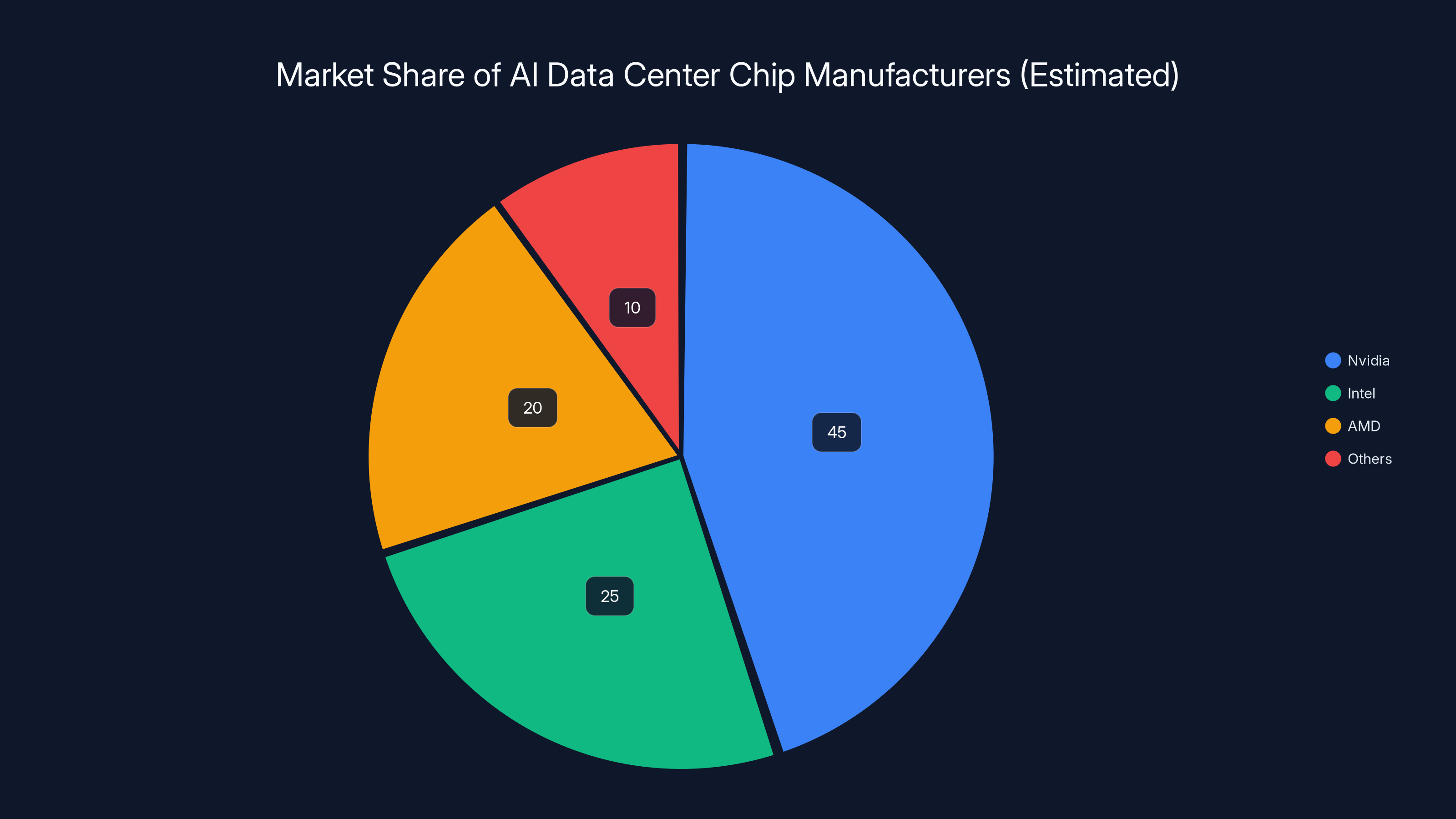

Nvidia's Dominance Isn't Going Away Anytime Soon

For all the talk about competitors and alternatives, 2025 made clear that Nvidia was going to stay dominant in AI chips. The company's engineering capability, the AI software ecosystem that works with its chips, and its first-mover advantage in data center GPUs created a moat that would take years for competitors to cross.

AMD, other startups, and international competitors are working on alternatives. They'll win some wins. But the idea that Nvidia will face significant competition in data center AI accelerators before 2027 at the earliest seems unlikely based on what we saw in 2025.

Intel's Path Is Unclear

Intel's situation remains genuinely uncertain. The company has government support, manufacturing capability, and talented engineers. But it's also lost momentum in key product categories and is now partially run by government mandate rather than purely commercial logic.

The next few years will determine whether Intel can use government support to bootstrap a comeback or whether it becomes a legacy manufacturer competing on cost and patriotism rather than innovation. Based on 2025, it's genuinely unclear which path the company is on.

The Role of Government and Private Capital

CHIPS Act Funding: When Government Capital Meets Reality

The CHIPS Act poured tens of billions into the US semiconductor industry. But 2025 revealed something important: money alone doesn't solve engineering and manufacturing problems.

Intel got billions in CHIPS Act funding, and the company still struggled. Samsung and TSMC both received support, but success was far from guaranteed. Simply spending money doesn't automatically create competitive fabs or innovative chip designs.

What the government seemed to learn in 2025 is that capital needs to be paired with operational excellence, which is harder to mandate or purchase. This led to more hands-on government involvement, like taking an equity stake in Intel, rather than just writing checks and hoping for the best.

The Venture Capital Perspective on Semiconductor Startups

Despite government support for established players, venture capital continued funding semiconductor startups pursuing specialized niches. Companies working on AI inference, edge computing, custom accelerators, and domain-specific chips continued raising money.

The logic was clear: the giant companies (Nvidia, AMD, Intel) were focused on general-purpose computing. That left room for specialists. VC money was betting on these specialists either getting acquired by giants or building sustainable businesses in niches where generalists couldn't compete.

In 2025, Nvidia is estimated to hold the largest share of the AI data center chip market, capitalizing on its early positioning. Estimated data.

The International Dimension: TSMC, Samsung, and the Asian Supply Chain

TSMC's Strategic Position Strengthens

Even as the US and Europe invested in domestic fabs, TSMC remained the industry leader. The company's process technology was simply better than what competitors could produce.

TSMC worked to strengthen relationships in the US and Japan while also maintaining access to Chinese customers (though this was politically fraught). The company essentially played the long game: it would support government initiatives while also ensuring it remained indispensable to the global semiconductor ecosystem.

Samsung's Split Strategy

Samsung approached things differently. The company invested in foundry capability while also maintaining vertical integration through its electronics business. Samsung could make chips for itself and for customers, which gave it more flexibility than pure foundry players.

Samsung also benefited from Korean government support for semiconductors, though not as much as US companies were getting from Washington.

China's Long-Term Play

While 2025 was dominated by headlines about Chinese bans on Nvidia and antitrust allegations, the real story was slower and more strategic. China was investing in domestic semiconductor capability, working on homegrown alternatives, and gradually reducing dependency on foreign chips.

This wasn't going to happen in a year or even five years. But the trajectory was clear. Over the next decade, China was going to have viable domestic alternatives for many chip categories.

AI's Outsized Impact on Semiconductor Strategy

Data Center Chips Became Everything

In 2025, it became clear that the semiconductor business had fundamentally shifted. The money wasn't in consumer products anymore. It was in data center infrastructure, particularly chips that could train and run AI models.

This changed strategic priorities across the industry. Companies that had been optimizing for mobile or consumer applications suddenly realized that's where their future didn't lie. The growth was in data center, and specifically in specialized accelerators.

Nvidia had positioned itself perfectly for this shift years earlier. Other companies had to scramble to reposition. Intel was trying to rebuild data center capability. AMD was pushing Instinct accelerators. Everyone else was either finding a specialty niche or exiting the space.

The Economics of AI Infrastructure

AI infrastructure economics are weird. The cost of chips is partially offset by the cost of electricity, cooling, and facilities. Companies building data centers were spending hundreds of millions or billions on what amounts to slightly customized standard infrastructure.

This meant that chip margins could be high without necessarily creating as much value as the revenue numbers suggested. A $50,000 GPU going into a data center was expensive, but the customer was also spending millions on the rest of the infrastructure.

This had policy implications. Governments became more interested in controlling access to these chips because controlling access to AI infrastructure effectively controls access to advanced AI capability.

The Human Element: Talent, Expertise, and Brain Drain

Semiconductor Engineers Became Valuable Commodities

2025 showed what happens when an entire technology becomes strategically important: talent becomes scarce and expensive.

Semiconductor engineers, chip designers, and manufacturing specialists could essentially name their price. Companies were competing fiercely for talent. Governments were trying to retain talent through visas and incentives. International poaching was becoming a recognized strategy.

When Nvidia hired people from Groq, that was partly about technology but mostly about talent. The same was true when other companies were hiring semiconductor expertise.

This created a weird situation where smaller startups were having trouble hiring against giant companies like Nvidia with massive valuations. But specialized fabs and design houses could still compete by offering equity stakes, technical freedom, and potentially lucrative exits.

The Knowledge Transition Problem

Many semiconductor companies in the US had experienced engineering leadership from people who'd been in the industry for 30, 40, even 50 years. When Michelle Johnston Holthaus left Intel, it wasn't just a leadership change. It was the loss of 30 years of institutional knowledge about how to build semiconductors.

Companies were starting to realize they needed to focus on succession planning and knowledge transfer. This was especially urgent at legacy companies where institutional knowledge was tied to long-tenured employees.

The Regulatory Environment: Antitrust, IP, and Standards

Antitrust Became a Trade Weapon

China's antitrust allegations against Nvidia for the Mellanox acquisition showed how antitrust enforcement was becoming a tool of trade policy rather than purely a matter of competition law.

This wasn't unique to China. The US was also starting to use regulatory tools for strategic purposes. But what was new was how explicitly it was being weaponized in semiconductor policy.

For chip companies, this meant accepting that business decisions about acquisitions and partnerships would increasingly face scrutiny not just on competition merits but on geopolitical implications.

IP Protection in a Fragmented World

As semiconductor manufacturing became more geographically distributed, protecting intellectual property became more complex. Companies had to think about which designs to keep proprietary, which to license, and which to share to maintain alliances.

This was especially complex for companies working across multiple geographies. An American company with Chinese customers and facilities might have its IP scrutinized by multiple governments simultaneously.

Market Consolidation and the Trend Toward Fewer, Larger Companies

The Economics Push Toward Scale

The massive costs of advanced semiconductor manufacturing and design created relentless pressure toward consolidation. Building a competitive modern fab cost tens of billions of dollars. Designing competitive chips required hundreds of engineers and years of development.

Small companies could compete in specialized niches, but in general-purpose computing, the trend was toward fewer, larger players. This was true even before government intervention. Government policy just accelerated the trend.

The Acquisition Environment

2025 saw significant M&A activity in semiconductors. Nvidia's strategic acquisition of Groq assets, integrations at Intel, and various smaller acquisitions all pointed to consolidation.

What was interesting was how much of this was driven by geopolitical strategy rather than pure economics. The Nvidia-Groq deal made sense geopolitically (keeping talent in the US). Intel's restructuring was partly driven by government mandates. Government support itself became a factor in M&A decisions.

Economic Impact: Who Won and Who Lost in 2025

The Clear Winners

Nvidia absolutely dominated 2025. Revenue growth in the 60+ percent range, unprecedented margins, and essentially no viable competitors in its core data center GPU market made the company the unquestionable leader.

Companies in the US and allied countries that had semiconductor operations benefited from government support and policy favoritism. Even struggling companies like Intel got backstopped by government investment.

Semiconductor equipment makers did well because everyone was building capacity. ASML, Applied Materials, Lam Research, and others that provide the tools for chip manufacturing saw demand spikes.

The Complicated Middle

AMD had a decent year but remained a distant second to Nvidia. The company was profitable and growing, but not at the growth rates or margins that Nvidia achieved.

TSMC remained economically dominant but faced increased pressure from governments wanting domestic capability. The company's foundry business was strong, but it was increasingly operating in a geopolitically complex environment.

Companies with Chinese exposure faced difficult tradeoffs between access to a huge market and exclusion from US-supported opportunities. Many companies struggled to optimize across this tradeoff.

The Clear Losers

Intel shareholders had a rough 2025. The company struggled operationally, faced government pressure, and was essentially turned into a quasi-government agency. Stock performance reflected the uncertainty.

Companies dependent on unrestricted semiconductor trade found themselves squeezed by new export controls, tariffs, and policy restrictions.

Consumers and companies buying chips faced higher prices and less favorable terms as supply chains became fragmented and companies had to navigate policy restrictions.

What Happened in Those Early 2026 Weeks That Matter

While this timeline focuses on 2025, the first few weeks of 2026 already showed that the trends from last year weren't slowing down. New tariffs were announced, international semiconductor deals were being negotiated, and companies were continuing to position themselves for a world of strategic competition rather than open markets.

If 2025 was the year the semiconductor industry transformed, 2026 is looking like the year those transformations get cemented into business reality.

Conclusion: The New Semiconductor Reality

2025 was the year the semiconductor industry admitted that it had become a strategic asset, not just a business.

This changes everything. It changes how companies plan. It changes how governments invest. It changes how countries think about economic strategy. It changes what investors need to understand about companies in the space.

The old model, where companies competed on innovation and efficiency in a global market, is being replaced by something more like energy markets. Semiconductor supply has become a matter of national security. Policies are nationalist rather than market-optimized. Companies are expected to serve strategic objectives, not just shareholder returns.

This is good for established players with government support. It's complex for companies caught between geopolitical powers. And it's challenging for consumers and companies that just want reliable access to chips.

But it's the world we're in now. The semiconductor industry in 2025 revealed what the industry will look like for the next decade. It won't be the semiconductor industry. It will be the semiconductor industries, plural, fragmented by geopolitics and tied to government policy.

Companies that understand this dynamic and position themselves accordingly will thrive. Companies that don't will struggle. And for anyone building businesses that depend on semiconductors, understanding this shift isn't optional. It's essential.

FAQ

What was the most significant event for semiconductors in 2025?

Nvidia's record quarterly earnings in November, with $57 billion in revenue and 66% year-over-year growth, was the headline event. But arguably more significant long-term was the US government taking a 10% equity stake in Intel, signaling that semiconductor manufacturing had become a matter of government policy rather than purely commercial competition.

How did export controls affect Nvidia in 2025?

Nvidia faced a complex policy environment where export restrictions were tightened, reversed, and then reasserted. China banned domestic companies from buying Nvidia chips in September, even as the US Commerce Department was reversing some restrictions. This created uncertainty that affected Nvidia's China strategy but didn't ultimately derail the company's dominant market position.

Why did the US government invest in Intel specifically?

The US government viewed Intel as strategically important for domestic semiconductor manufacturing capability. By taking an equity stake, the government ensured it had decision-making power over Intel's foundry business and could mandate that the company remain committed to US-based manufacturing regardless of commercial profitability.

What does the 15% revenue-sharing arrangement with China mean for AMD and Nvidia?

The arrangement means companies selling AI chips to China must pay the US government 15% of that revenue. This effectively increased the cost of doing business in China, creating an incentive for companies to focus on other markets. It also formalized government participation in semiconductor export revenue.

How did China respond to American semiconductor dominance in 2025?

China used multiple tools: bans on purchasing foreign chips, antitrust allegations against foreign companies, and mandates for domestic alternatives. These weren't necessarily effective immediately, but they signaled China's long-term strategy of reducing dependence on foreign semiconductor technology.

What does Nvidia's acquisition of Groq assets tell us about the semiconductor industry's direction?

It shows that talent and specialized IP are becoming as valuable as general-purpose chip design capability. Nvidia didn't acquire Groq because Groq was outcompeting it. Nvidia acquired it to prevent competitors from getting the talent and ensure Nvidia had capability in inference optimization. This signals that the industry is moving beyond just competing on product and toward competing on talent and strategic positioning.

Why is semiconductor manufacturing suddenly a government priority?

Semiconductors are foundational to AI, military technology, communications infrastructure, and economic competitiveness. When these technologies become geopolitically important, governments get involved. This happened to semiconductors in 2025 because AI advancement made chip access a national security matter.

What does the future of semiconductor competition look like based on 2025 trends?

Based on 2025, the future looks like multiple regional semiconductor ecosystems rather than a single global market. The US will develop capability with government support. Europe will do the same. China will pursue self-sufficiency. Taiwan (TSMC) will remain dominant in advanced manufacturing but increasingly operate in a politically complex environment. This is economically inefficient but strategically necessary from each country's perspective.

Could Intel actually recover with government support?

It's possible but not guaranteed. Government support can fund manufacturing capacity, but it can't automatically make engineers better or produce innovative chips. Intel has the infrastructure and talent to potentially recover, but execution under government constraints is different from execution as a pure commercial business.

How does this affect companies trying to buy semiconductors?

Companies need to assume supply chain complexity will continue increasing. Diversifying suppliers, building redundancy, and planning for supply disruptions are no longer optional. The semiconductor market is becoming more about strategic relationships and government policy than pure commercial efficiency.

Key Takeaways

- Nvidia dominated the semiconductor industry in 2025 with $57B in Q3 revenue representing 66% year-over-year growth, solidifying its position in AI infrastructure

- The US government took unprecedented steps by converting CHIPS Act grants into 10% equity ownership of Intel with decision-making power over foundry operations

- China implemented policy restrictions including domestic chip purchase mandates and antitrust allegations to reduce dependency on foreign semiconductors

- The semiconductor industry shifted from a globally integrated market to regionally fragmented ecosystems driven by government policy and geopolitical strategy

- Strategic consolidation accelerated with Nvidia acquiring Groq assets, Intel restructuring leadership, and large tech companies pursuing vertical integration into chip design

Related Articles

- Gate-All-Around Transistors: How AI is Reshaping Chip Design [2025]

- Trump's 25% Advanced Chip Tariff: Impact on Tech Giants and AI [2025]

- RAM Price Hikes & Global Memory Shortage [2025]

- Kioxia Memory Shortage 2026: Why SSD Prices Stay High [2025]

- Data Centers to Dominate 70% of Premium Memory Chip Supply in 2026 [2025]

- Did Apple Invest in Intel? Trump's Claims Analyzed [2025]