India's Deep Tech Startup Rules: What Changed and Why It Matters [2025]

India just made a quiet but significant move that could reshape how the world's second-most-populous nation builds its deep tech future. The government updated its startup framework—the rules that determine which companies qualify for tax breaks, grants, and regulatory support. For deep tech founders, this matters more than you'd think.

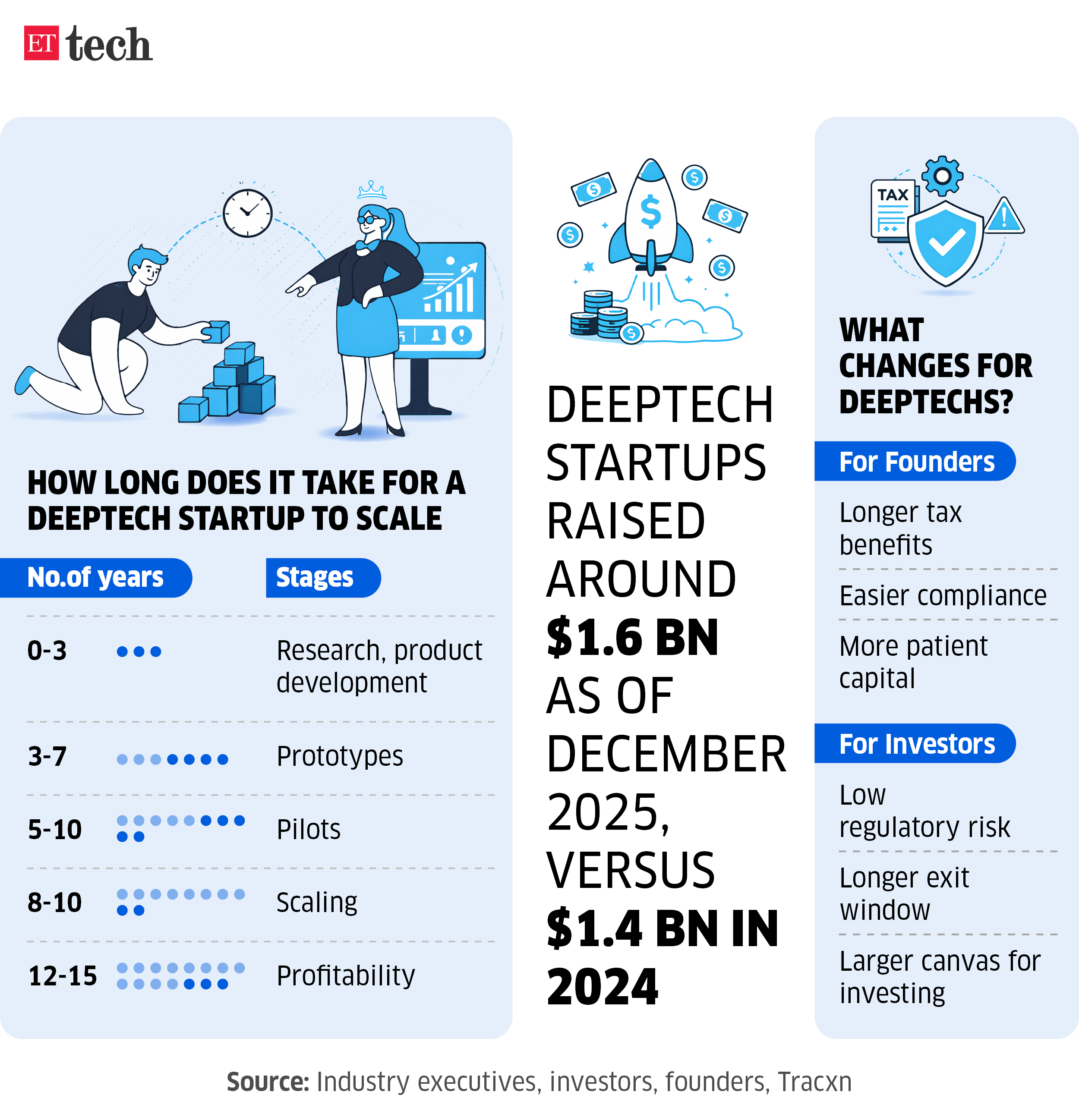

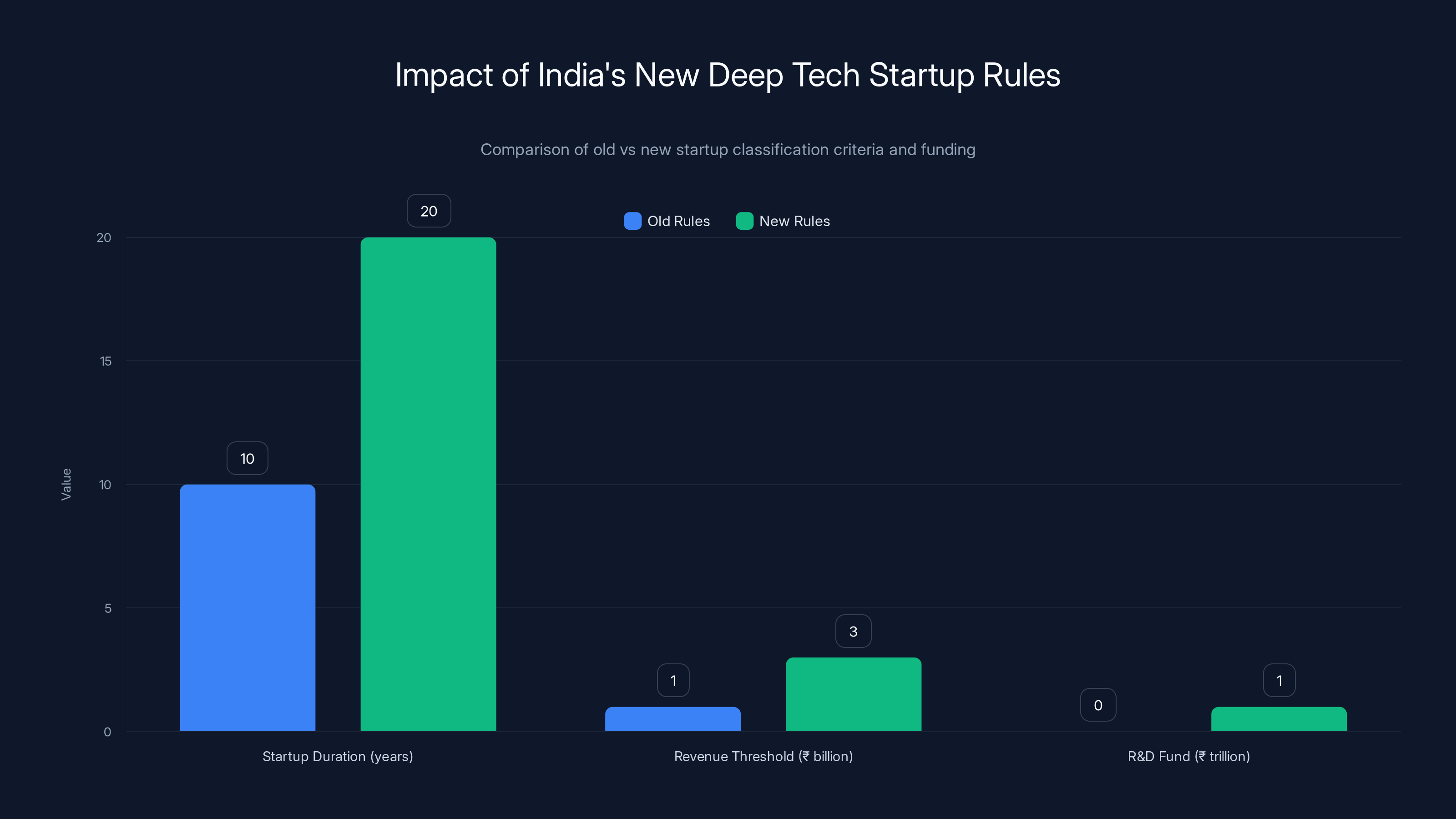

Here's what changed: the period during which companies are classified as startups doubled from 10 to 20 years. The revenue threshold for startup-specific benefits jumped from ₹1 billion (roughly

Why does this matter? Because the old rules were effectively punishing India's most ambitious founders. A semiconductor startup might spend eight years in R&D before reaching commercial viability. Under the old framework, they'd lose startup status at year 10, losing access to government grants, tax benefits, and regulatory flexibility right when they needed them most. Suddenly, the government was treating a cutting-edge deep tech company like it had failed, when really it was just progressing slowly by design.

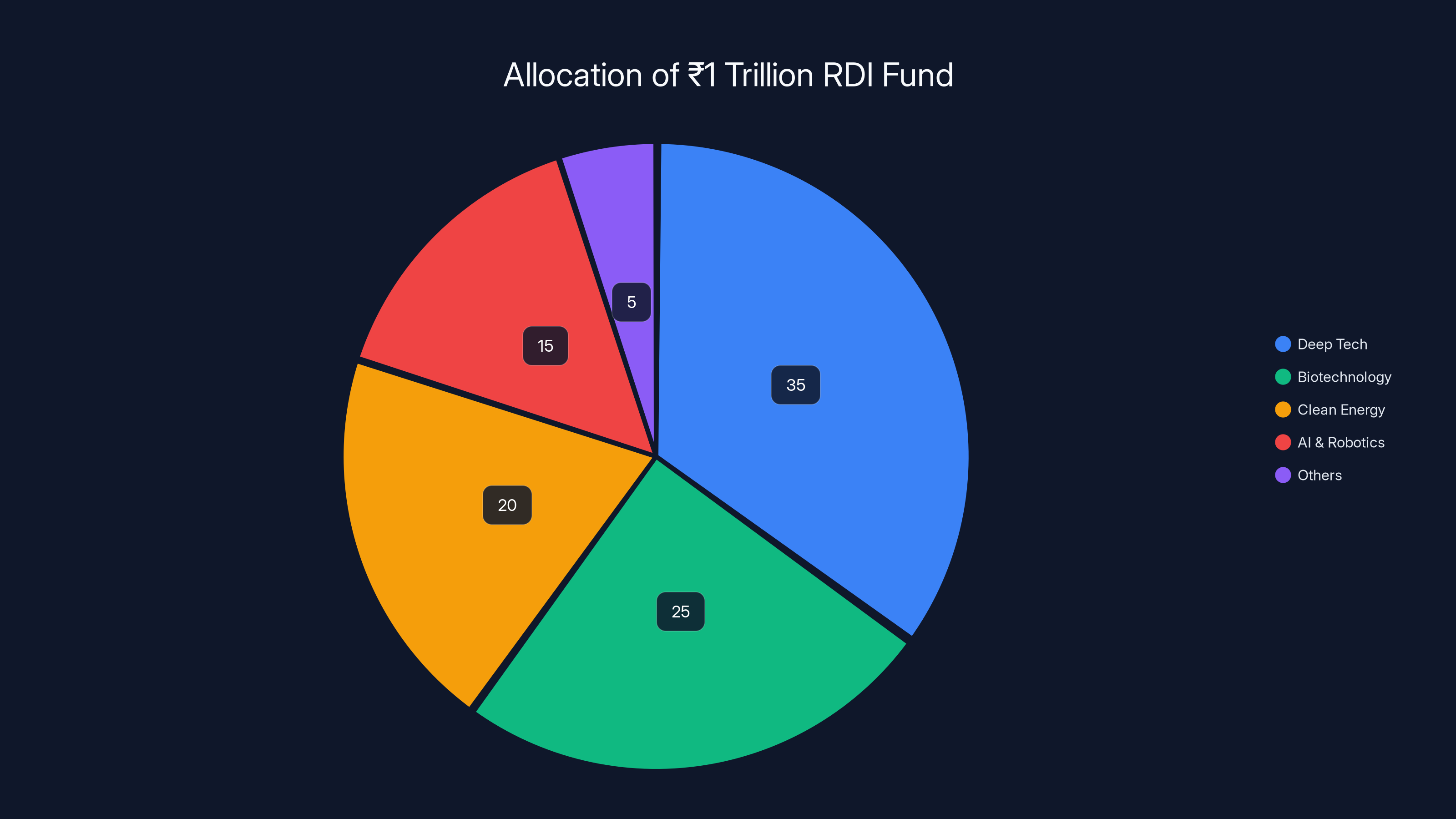

The Indian government isn't stopping at policy adjustments either. Last year, they announced the Research, Development and Innovation Fund—a ₹1 trillion ($11 billion) patient capital vehicle specifically designed to fund science-led companies through their long development cycles. This week's policy change is meant to work in tandem with that fund, creating a more coherent ecosystem for deep tech entrepreneurship.

What's interesting is that this is happening while India is still a relatively young deep tech market. U.S. deep tech startups raised about

For founders outside India, this signals something important: governments are starting to understand that deep tech requires different rules. The days of measuring biotech and semiconductor companies against the same metrics as B2B SaaS startups are ending, at least in New Delhi. That's a precedent worth watching.

TL; DR

- Startup designation period doubled to 20 years: Deep tech companies now have twice as long to reach commercial viability before losing startup status and associated benefits

- Revenue threshold increased to ₹3 billion: The baseline for startup benefits rose 3x, giving companies more time in the startup category

- ₹1 trillion RDI Fund launched: Government-backed patient capital specifically designed for science-led ventures at Series A and beyond

- Private capital mobilizing: The India Deep Tech Alliance represents $1 billion-plus from Accel, Qualcomm Ventures, Nvidia, and others, signaling mainstream investor confidence

- Bottom Line: India is creating policy and capital infrastructure for a 15-25 year deep tech development cycle, not the 3-5 year SaaS cycle

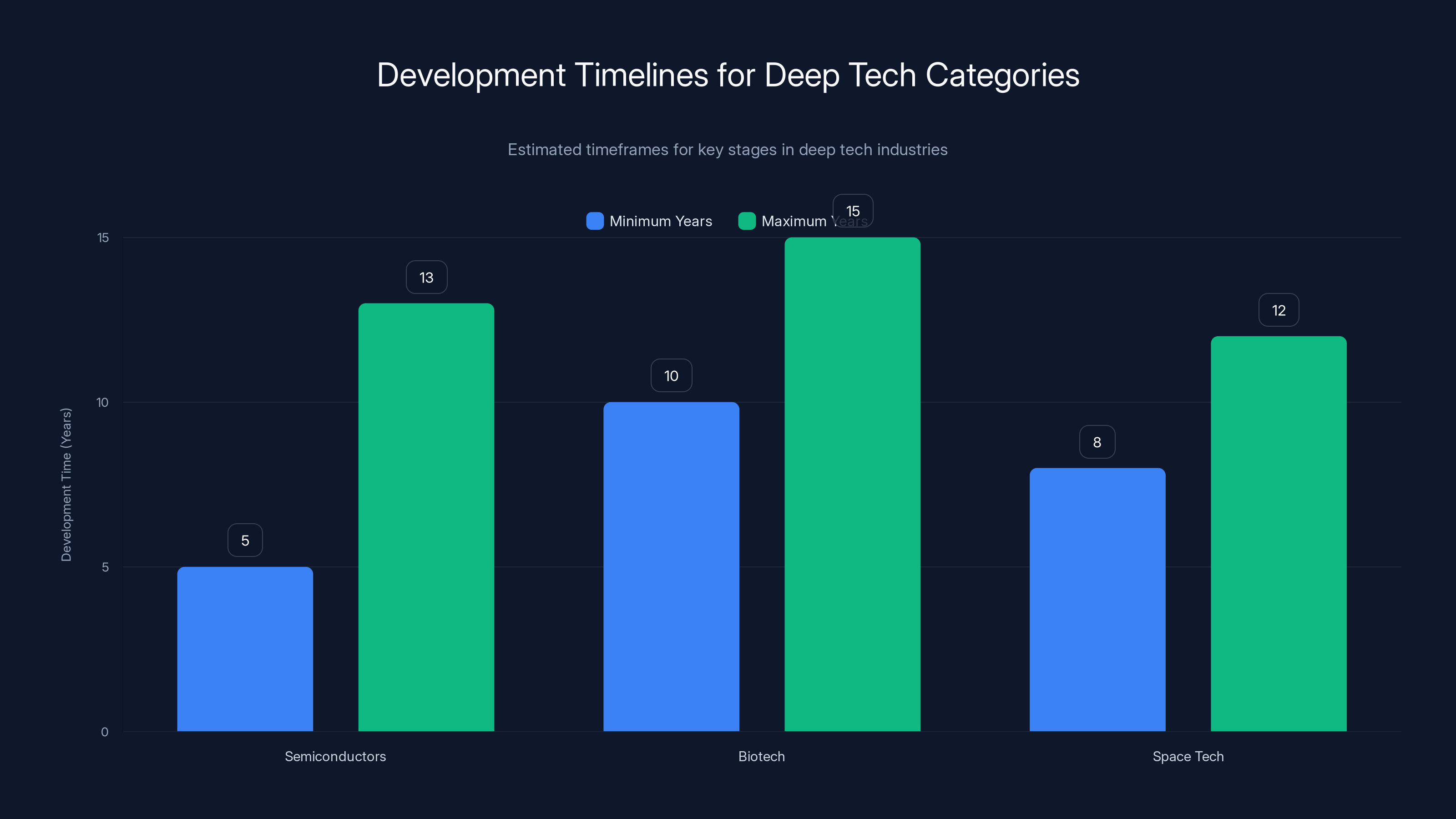

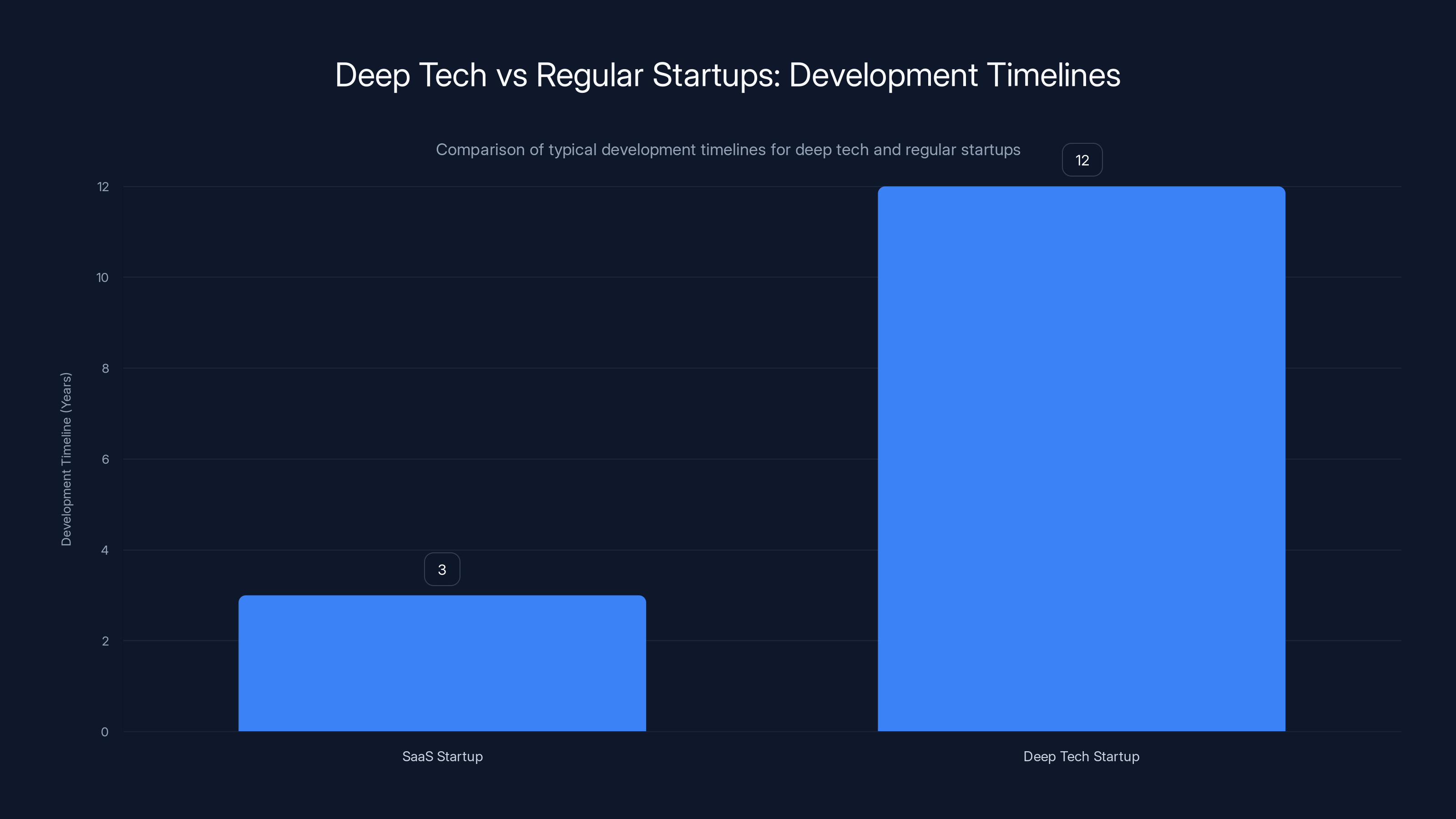

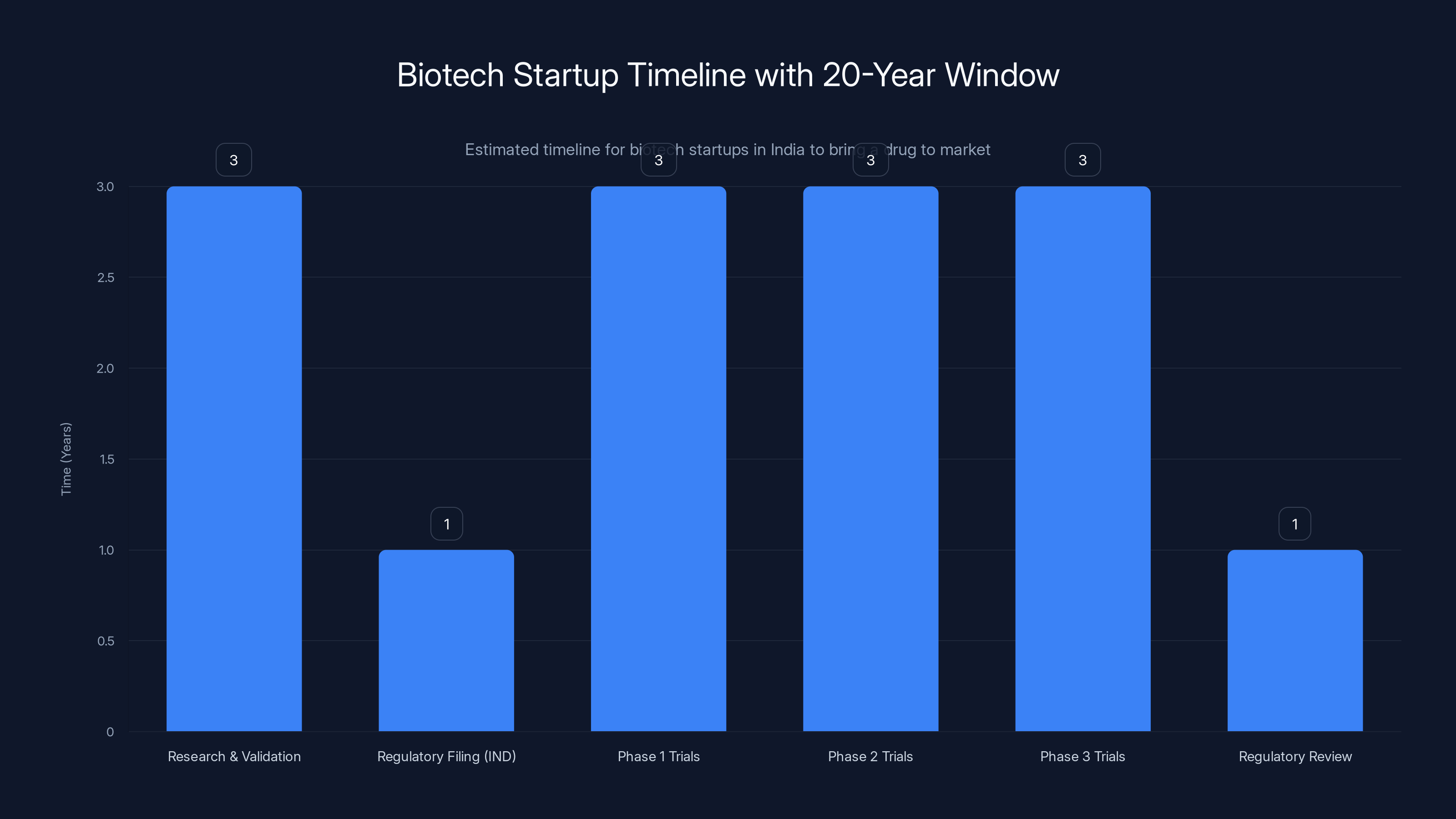

Estimated development timelines show that deep tech industries often require extensive periods, justifying the extended startup designation period. Estimated data.

The Problem: Old Rules Punishing Long-Term Innovation

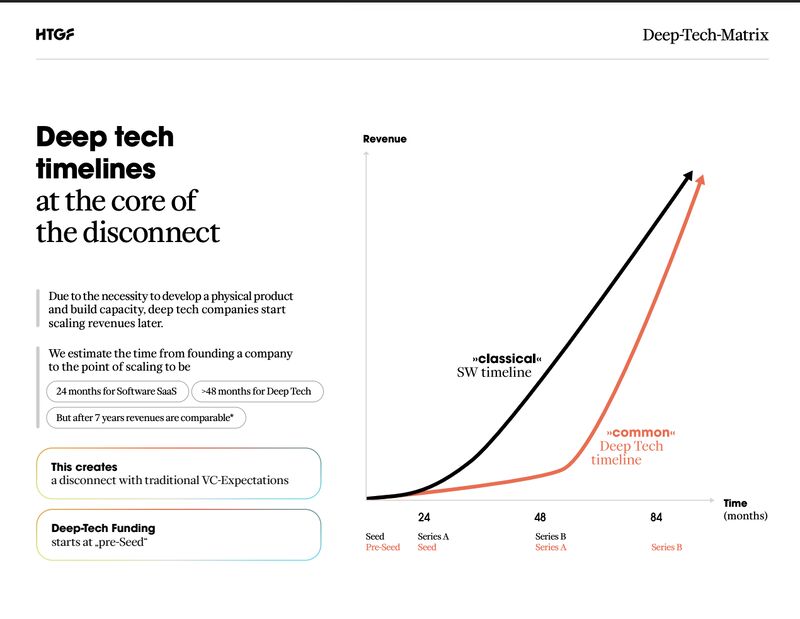

Let's step back and understand why these changes matter so much. Deep tech companies operate on a fundamentally different timeline than your typical startup. A software-as-a-service company can launch a minimum viable product in months, get customer feedback in weeks, and hit profitability in 2-3 years if things work out. The business model is straightforward: acquire users, reduce churn, raise capital, scale.

Deep tech doesn't work that way. Building a semiconductor startup means years of design, fabrication, testing, and refinement before you have a product. A biotech company might spend 5-7 years just running clinical trials. A space tech company? You're looking at 8-10 years before your first commercial satellite launches. These aren't signs of failure. They're signs of the technical reality.

The problem was that India's old startup classification system didn't recognize this reality. The framework treated all startups the same, which meant that a semiconductor company operating exactly as expected—spending years on R&D, not yet generating revenue—could be classified as a failure after 10 years.

Vishesh Rajaram from Speciale Invest, a deep tech venture firm, called this the "false failure signal" problem. When a deep tech startup loses its startup classification while still pre-commercial, it looks like the company failed. But really, it's just following the timeline required by physics and biology.

That false signal creates ripple effects. Investors get nervous. Employees start updating their resumes. Recruitment becomes harder. Banks get skeptical about loans. Regulators pay less attention. The startup can be doing everything right—advancing the technology, hitting technical milestones, securing IP—but the policy framework treats it like a zombie company.

More insidiously, the old rules created perverse incentives. Founders might pivot toward faster-exit opportunities just to stay ahead of the startup classification cliff. A deep tech team might abandon a genuinely important hard problem to chase something that can generate revenue faster. From a policy perspective, you're essentially incentivizing founders to give up on hard tech in favor of easier wins.

Rajaram described the impact plainly: "By formally recognizing deep tech as different, the policy reduces friction in fundraising, follow-on capital, and engagement with the state, which absolutely shows up in a founder's operating reality over time."

What he's saying is that the new rules remove a hidden tax on ambition. Founders can now focus on the science instead of watching the regulatory clock. That psychological shift—knowing you have 20 years to build instead of 10—is more powerful than it sounds.

The New Rules: A 20-Year Timeline

So what exactly changed? The Indian government updated three key parameters:

Startup Designation Period: Extended from 10 years to 20 years. This is the primary change. A deep tech company can now maintain its startup status for twice as long, giving founders a much wider window to reach commercial viability.

Revenue Threshold: Raised from ₹1 billion to ₹3 billion. This is actually more lenient than it sounds. Previously, a startup had to keep revenue below ₹1 billion to maintain startup status. Now it can revenue up to ₹3 billion and still qualify. For comparison, that ₹3 billion threshold is roughly equivalent to $36 million in revenue—substantial for a deep tech company but not impossible to hit while still being in growth mode.

Benefit Categories Expanded: The policy now explicitly carves out "deep tech" as a distinct category, which means regulatory bodies and government agencies have clear guidance about how to treat these companies. Instead of forcing deep tech into the same mold as software startups, there's now official recognition that the rules need to differ.

These changes align with what investors and founders were already saying—that a 10-year timeline was too short. In practice, many deep tech companies were already losing startup status prematurely, right when they needed the most support.

Consider the math for a few deep tech categories:

-

Semiconductors: Design (2-3 years), fabrication (1-2 years), testing and validation (1-2 years), customer deployment (1-2 years). You're already at 5-9 years, and that's for a relatively simple chip. Advanced semiconductors? Add another 2-4 years.

-

Biotech: Research and validation (2-3 years), IND application (1 year), Phase 1 trials (1-2 years), Phase 2 trials (2-3 years), Phase 3 trials (2-3 years), FDA review (1-2 years). You're looking at 10-15 years minimum, and sometimes longer.

-

Space Tech: Vehicle design and development (3-5 years), launch licensing and regulatory approval (1-2 years), manufacturing (1-2 years), launch operations (1+ year). Six to ten years before meaningful commercial revenue.

Under the old 10-year system, you'd lose startup status right in the middle of your critical growth phase. Under the new 20-year system, you're covered through commercialization and early scaling.

Arun Kumar from Celesta Capital pointed out that the real constraint for deep tech isn't policy—it's capital. The new rules help, but they're part of a larger puzzle. "The biggest gap has historically been funding depth at Series A and beyond, especially for capital-intensive deep tech companies," Kumar said. That's where the government's RDI fund enters the picture.

The RDI fund is primarily focused on deep tech, with significant allocations to biotechnology and clean energy. Estimated data based on typical sector focus.

The ₹1 Trillion RDI Fund: Patient Capital at Scale

Policy reform alone doesn't solve the capital problem. That's why the Indian government last year announced the Research, Development and Innovation Fund—the RDI fund—a ₹1 trillion ($11 billion) commitment of public capital specifically designed for science-led companies.

The RDI fund works differently than typical government grants or venture capital funds. Instead of top-down government bureaucrats picking winners, the fund is structured to work through venture firms and private equity managers. The government essentially says: "We'll commit capital to funds that specialize in deep tech, and we'll trust your investment criteria." This preserves the commercial discipline of private investing while injecting patient capital that might not otherwise flow into early-stage deep tech.

Why is this structure important? Because it avoids two common pitfalls. First, it doesn't create a separate "government deep tech track" with different standards. Startups get funded based on merit, not political connections. Second, it doesn't try to replace private capital—it complements it. The fund managers are still venture capitalists making commercial bets, not bureaucrats allocating subsidies.

Siddarth Pai from 3one4 Capital explained that the RDI fund is designed to "act as a nucleus around which greater capital formation can occur." In other words, by deploying ₹1 trillion responsibly, the government signals that deep tech is worth investing in. That confidence rubs off on other investors. Large family offices, pension funds, and international LPs see the government committed and think, "Okay, maybe deep tech India is actually happening."

As of early 2025, the RDI fund process was already underway. The government had identified the first batch of fund managers and was selecting venture and private equity managers to deploy the capital. This wasn't theoretical—it was happening in real time.

What makes the RDI structure novel is that it doesn't limit itself to traditional venture equity. The fund can also provide credit (loans) and grants to deep tech startups. This flexibility matters because not every deep tech company wants or needs dilutive equity. A hardware company with a clear path to revenue might prefer a loan. A very early-stage biotech might need a grant to fund proof-of-concept work.

For comparison, here's how much deep tech capital was actually flowing in 2025:

- United States: $147 billion in deep tech funding

- China: ~$81 billion

- India: $1.65 billion

India's allocation was about 1.1% of the U.S. level. Now add a ₹1 trillion fund (roughly $12 billion over its lifecycle) and you're still well behind, but the gap is closing. More importantly, the intent is clear: India wants to build deep tech as a national priority, not treat it as a curiosity.

The Private Capital Mobilization: India Deep Tech Alliance

The policy changes and RDI fund got the headline attention, but here's what really signals market confidence: private capital is moving in tandem. The India Deep Tech Alliance, launched recently, represents $1 billion-plus of private capital committed to Indian deep tech ventures.

The Alliance includes some of India's best venture firms—Accel, Blume Ventures, Celesta Capital, Premji Invest, Ideaspring Capital, Kalaari Capital—plus international players like Qualcomm Ventures. Nvidia is advising. This isn't a government-mandated consortium. It's a voluntary coalition of sophisticated investors saying: "We believe in India's deep tech ecosystem enough to coordinate our efforts."

That matters psychologically and practically. Psychologically, it sends a signal to founders that deep tech fundraising in India is real. You don't get a VC alliance if the asset class isn't working. Practically, coalition members share deal flow, coordinate on late-stage rounds, and agree on ecosystem standards. Instead of 20 separate venture firms backing 20 separate companies, you have coordinated capital pushing in the same direction.

Accel, for example, is one of the world's best-known venture firms. Their participation signals that Indian deep tech isn't just a domestic story—it's part of a global tech narrative. Qualcomm Ventures (the corporate VC arm of the semiconductor giant) participating is especially significant because it means Qualcomm itself sees strategic value in Indian deep tech companies.

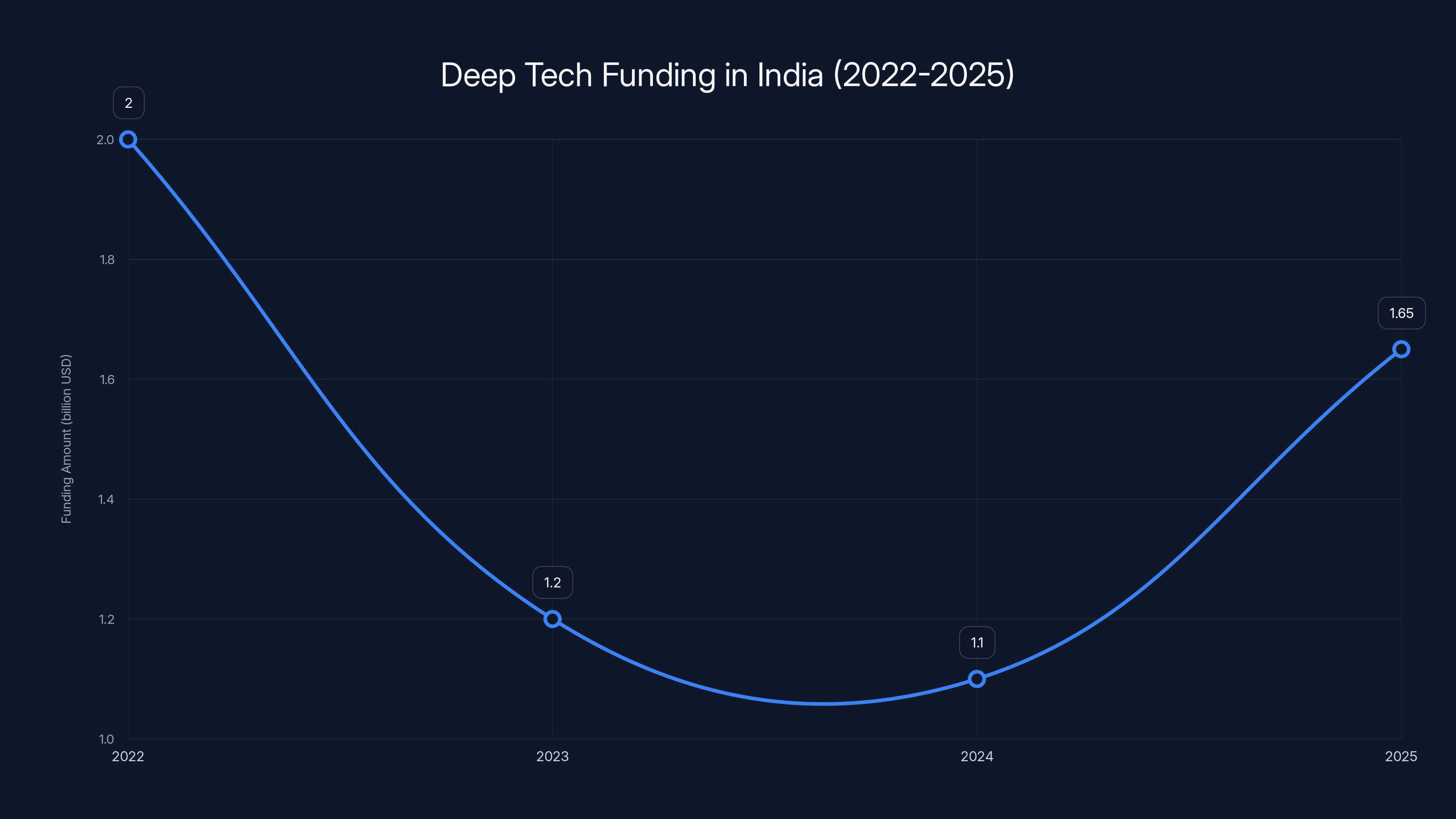

The timing matters too. These commitments came right as deep tech funding rebounded in 2025. After dipping from the

The Capital Gap That Still Exists

Here's the reality check: policy and committed capital are necessary but not sufficient. India's deep tech ecosystem still faces a fundamental capital gap, particularly at Series A and beyond.

Rajaram from Speciale Invest was direct about this: "The biggest gap has historically been funding depth at Series A and beyond, especially for capital-intensive deep tech companies." What does this mean in practice?

A seed-stage deep tech company can raise

The gap creates a specific problem: founders have to choose between dilution and debt. They can raise a massive Series A at a low valuation and accept heavy dilution. Or they can take on debt they might not be able to service (since they're not profitable yet). Neither is ideal.

This is where the RDI fund is supposed to step in. By deploying ₹1 trillion through commercial fund managers, the government is essentially saying: "We'll fund companies from Series A onward, and we'll use flexible structures (equity, debt, grants) matched to what each company needs."

But here's the catch: the RDI fund is patient capital, which means it's not coming in the next 3 months. Fund managers are still being identified. Once they're selected, they'll take time to source deals, conduct due diligence, and get capital deployed. Probably 12-18 months before meaningful capital is flowing.

In the meantime, founders still face the Series A gap. The solution is that existing VCs—the ones in the India Deep Tech Alliance—are stepping up. By coordinating their capital and making commitments, they're creating a bridge until the RDI fund is fully operational.

Deep tech funding in India peaked at

How the Ecosystem Was Broken Before

To understand why these changes matter, it helps to understand how the system actually broke down for deep tech founders.

A semiconductor startup would incorporate as a startup, raise seed capital (₹5-20 crores), and begin R&D. For years 1-4, they're designing chips, securing partnerships, and building IP. Revenue is zero. But they're clearly making progress—taping out designs, signing MOUs with customers, attracting talented engineers.

Years 5-7, the chips are in manufacturing and testing. Still minimal revenue. The company is burning cash, but it's all going toward a specific goal: getting working silicon. Any investor in semiconductors knows this is normal.

Year 8 arrives. The chips work. Customers are interested. But the company still isn't profitable—it's ramping production and building manufacturing partnerships. And here's where the old rules created chaos: the company was approaching its 10-year startup classification limit.

What would happen next? The startup would lose its designation. Suddenly, it couldn't access startup benefits anymore. Tax breaks disappeared. Grant programs became unavailable. Regulators treated it differently. The company had hit its stride just as the policy framework pulled the rug out.

Investors saw this and thought: "This is risky. The government is essentially saying these companies aren't startups anymore, which means they're expected to be profitable. But they're not. Are they in trouble?" That perception—a "false failure signal"—made follow-on fundraising harder at the worst possible time.

Better-capitalized teams would accelerate toward profitability (and potentially inferior technology) just to stay compliant with the old rules. Some teams would pivot to faster businesses. The talented ones might move to the U.S. or China where the policy framework didn't penalize long development cycles.

The new 20-year window fixes this. A semiconductor company can now operate under the startup umbrella for 20 years, which covers design, manufacturing, regulatory approval, customer ramp, and initial scaling. No false failure signal. No perverse incentives to accelerate toward inferior outcomes.

India's Deep Tech Strengths: Where Policy Meets Reality

India has specific deep tech strengths that make this policy timing strategic. The country isn't trying to build deep tech out of nowhere—there are already clusters and capabilities.

Biotech and Pharma: India has a world-class generic pharmaceutical industry and strong biotech research institutions. Companies like Lupin, Cipla, and Glenmark employ hundreds of thousands. The talent pipeline is established. What was missing was venture capital willing to fund novel drug discovery. The RDI fund + extended startup timeline fixes that.

Space Tech: India's space program is legendary. ISRO operates one of the most efficient space agencies on Earth. When Indian entrepreneurs spun out of ISRO to start companies like Skyroot Aerospace and Agnikul, they had government expertise, proof of concept, and clear market validation. Again, the gap was capital. Now they have it.

Advanced Manufacturing: India has been trying to build a semiconductor manufacturing ecosystem for years. New fabs are opening (Samsung, Intel partnerships). The government has allocated ₹50,000 crores for semiconductor production. Deep tech startups can now provide supply chain, design tools, and process improvements. The policy framework now supports these ventures for long enough to prove value.

Climate Tech: India faces acute climate challenges—water scarcity, air quality, extreme heat. This creates demand for climate tech that's perhaps stronger than anywhere else. Companies building carbon capture, water purification, or grid technologies have a massive home market and clear regulatory tailwinds.

The point: India's policy changes aren't happening in a vacuum. They're amplifying existing strengths. The government is saying: "We know you have talent, we know you have problems to solve, and we'll now provide the policy and capital stability you need to solve them."

Comparison: How Other Countries Treat Deep Tech

India's approach is interesting partly because it's different from how other countries handle the same problem.

United States: The U.S. doesn't have a specific "deep tech startup" designation at all. Instead, it relies on abundant venture capital and patient investors who understand tech timelines. DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) provides government grants, but they're for specific research projects, not blanket startup benefits. The approach works because there's enough private capital to fund deep tech without government intervention.

China: Heavily state-directed. The government picks specific sectors (semiconductors, quantum, space) and aggressively funds them through state-owned enterprises and directed venture capital. It's effective but less market-driven than India's approach.

Europe: The EU has been trying to build deep tech capacity through funding programs like Horizon Europe and other grants. The approach is more administrative than India's—more like making capital available than streamlining the regulatory framework.

Israel: Treats deep tech as core to national security and provides tax benefits, grants, and regulatory flexibility (similar to India's new approach). Combined with military R&D experience and U.S. venture capital proximity, Israel has built a thriving deep tech ecosystem.

India's approach is actually closest to Israel's: combine policy flexibility with patient capital and assume that entrepreneurs will do the rest. The key difference is scale. Israel has 9 million people; India has 1.4 billion. If the model works in India, it could support an entirely different magnitude of deep tech innovation.

Deep tech startups typically require 8-15 years to develop, compared to 2-3 years for regular SaaS startups. Estimated data.

Sector-Specific Impact: Semiconductors

Let's dive deeper into how these changes affect specific sectors. Start with semiconductors, arguably India's most strategically important deep tech sector.

India wants to reduce reliance on Taiwan and South Korea for chip manufacturing. The government is investing in fabs (fabrication plants) and supply chain development. That infrastructure is happening, but it needs supporting technology.

A semiconductor design startup operating in India now benefits from:

- Extended runway: 20 years to develop and commercialize a design without losing startup status

- Tax benefits: Continued access to startup tax breaks extends further into the business lifecycle

- RDI funding: Access to patient capital specifically for semiconductor ventures

- Government contracts: As India's government pushes "Make in India" semiconductors, startups have clear potential customers

In practice, this means a semiconductor startup can:

- Spend 2-3 years designing

- Spend 1-2 years securing foundry partnerships (likely with Samsung, Intel, or emerging Indian fabs)

- Spend 1-2 years in manufacturing

- Spend 2-3 years ramping with customers

- And still have 12+ years left on the startup clock

That changes the calculus entirely. Previously, founders would be stressed about the 10-year limit. Now, they can focus on getting the technology right without watching the regulatory clock.

Sector-Specific Impact: Biotech

Biotech is another beneficiary. India has strong pharmaceutical and biotech research talent. Dozens of startups are working on novel drug discovery, diagnostics, and medical devices. The old 10-year startup window was essentially worthless for biotech—companies typically need 10-15 years minimum to get a drug to market.

With the 20-year window, a biotech company can:

- Spend 2-3 years on research and validation

- Spend 1 year on regulatory filing (IND)

- Spend 2-3 years on Phase 1 trials

- Spend 2-3 years on Phase 2 trials

- Spend 2-3 years on Phase 3 trials

- Spend 1 year on regulatory review

- And still be within the startup window

More importantly, the RDI fund can structure capital as grants for early research and loans for later-stage clinical work. This mixed capital approach is ideal for biotech, where early research is speculative but later-stage work has clearer paths to commercialization.

Sector-Specific Impact: Space Tech

Space tech is perhaps the most visible beneficiary. Companies like Skyroot, Agnikul, and Bellatrix have already launched vehicles and started taking commercial orders. But they're still years away from profitability and significant revenue.

The space tech timeline typically looks like:

- Years 1-2: Vehicle design and development

- Years 2-4: Manufacturing and testing

- Years 3-4: Licensing and regulatory approvals

- Year 4+: Launch operations and customer delivery

- Years 5-7: Achieving profitability

Under the old 10-year framework, a space company would be pushing hard to hit profitability by year 8-9. With 20 years, they can focus on building a sustainable business rather than chasing premature revenue.

The RDI fund is particularly useful for space tech because launches are capital-intensive. A single launch can cost ₹50-100 crores. Government-backed patient capital can support multiple launches while the company scales its customer base and reduces per-unit costs.

The new rules double the startup classification period and triple the revenue threshold, alongside a ₹1 trillion R&D fund, significantly boosting support for deep tech startups.

How This Changes Founder Decision-Making

Now let's talk about what this actually means for founders. Policy changes sound abstract until you realize they affect real decisions.

A founder considering a deep tech venture in India now has to think differently. Previously, the mental model was: "I have 10 years to develop the technology and start generating revenue. After that, I need to be profitable." This created pressure to accelerate development or compromise on ambition.

Now the mental model is: "I have 20 years to develop, commercialize, and achieve profitability. I have patient capital available at Series A and beyond. I can focus on solving the hard problem." That psychological shift enables different decision-making.

Specific decisions that change:

Hiring: A deep tech company can now hire specialists (chip designers, biotech researchers, aerospace engineers) knowing that the policy won't suddenly cut off support. Long-term hiring becomes rational.

R&D Investment: Instead of rushing to market, companies can invest more in research, prototyping, and validation. You're not burning runway on premature commercialization.

Pivot Strategy: If a company hits unexpected technical challenges, it has time to pivot or iterate. Under the old system, founders might have abandoned a good idea because the clock was running out. Now they can persist.

Fundraising Strategy: With the RDI fund available at Series A+, founders don't need to take whoever offers capital first. They can be more selective about partners who understand deep tech timelines.

Team Retention: Knowing the company has a long runway, talented engineers are more likely to stay. In hardware or biotech, experienced team members are irreplaceable.

The Timeline to Impact

Here's what to expect in terms of actual impact over the next few years.

2025 (Now): Policy is in place. First batch of RDI fund managers identified. India Deep Tech Alliance announcing commitments. Media coverage increasing investor awareness.

2026: RDI fund capital starts deploying through fund managers. Series A and Series B deals increase. Media coverage extends to international investors.

2027-2028: First generation of deep tech companies reaching commercialization under the new framework. Exit data starts accumulating (acquisitions, IPOs). This generates confidence for the next wave of investors.

2029-2030: Second and third generation deep tech companies fundraising with strong data from the first cohort. International capital flows to Indian deep tech increase significantly.

The key inflection point is when the first group of deep tech startups achieves significant exits. That's when the policy becomes self-reinforcing: success breeds capital, which attracts talent, which creates more success.

Remaining Challenges

Let's be honest about what hasn't changed and what challenges remain.

Talent: While India has strong technical talent, the concentration is in software. Deep tech requires specialized expertise in semiconductors, materials science, biotech, aerospace. India needs to either import this talent (visa/immigration challenges) or develop it domestically (years of education investment). The policy changes don't fix this directly.

Manufacturing Infrastructure: Deep tech often requires expensive manufacturing facilities. A semiconductor fab costs billions. A biotech manufacturing facility costs hundreds of millions. Policy and capital help, but physical infrastructure development takes time.

Customer Concentration: Many deep tech startups depend on government contracts (defense, space, energy). While government demand is good, over-reliance creates risk. Building diverse customer bases requires time and maturity.

Regulatory Expertise: Biotech, space, and certain manufacturing sectors have complex regulatory requirements. India's regulatory bodies are improving, but they're not yet at the speed and sophistication of FDA or FAA. This slows approval cycles.

Global Competitive Pressure: Deep tech isn't a zero-sum game, but India is competing with established players in the U.S., Europe, and China. Some sectors (semiconductors, space) are already crowded. India needs to find niches where it has advantages.

None of these are deal-breakers. They're just the reality of building deep tech at scale. The new policy framework addresses one key constraint (regulatory timeline and capital availability). The other constraints require talent development, infrastructure investment, and time.

Biotech startups can efficiently utilize the 20-year window to bring drugs to market, with each stage taking 1-3 years. Estimated data.

What This Means for Global Deep Tech

Step back and think about the broader implications. India is now explicitly competing to become a deep tech hub. That has ripple effects.

For talent: If India makes deep tech viable, talented engineers who would have otherwise emigrated now have reasons to stay. That's more competition for U.S. and European tech hubs trying to recruit.

For capital: If deep tech in India works, large pools of global capital (family offices, sovereign wealth funds, pension funds) will start deploying there. That changes global capital allocation.

For strategic independence: India has long-term interest in technological self-sufficiency. Deep tech—especially semiconductors and space—is core to that. Success here reduces India's reliance on imports and increases its strategic autonomy.

For innovation: Different regions have different problems. Water scarcity in India creates different climate tech needs than in Europe. That regional specificity could drive different types of innovation.

For precedent: If India's model works, other emerging economies (Southeast Asia, Latin America, Africa) might adopt similar frameworks. That could decentralize deep tech development globally.

None of this is certain. India's deep tech ecosystem could struggle to scale despite policy support. But the combination of policy reform + patient capital + private sector coordination is the best formula we've seen for building deep tech outside the U.S.

The Role of Existing Players

An important dynamic: this isn't just about new startups. Existing Indian tech companies are also positioning for deep tech.

Established software companies with strong balance sheets (Infosys, TCS, Wipro) are investing in deeptech ventures and partnerships. They have capital, talent, and credibility. As deep tech companies mature, they become customers for services these established players can provide.

Family offices and established industrial conglomerates are also investing. The Tata Group, Reliance, and others have deep pockets and long-term time horizons perfect for deep tech. These investors often go unnoticed in discussions of "startup capital," but they're crucial for funding Series B and Series C rounds where capital requirements get substantial.

The policy changes align these incentives. What was previously scattered support for deep tech becomes coordinated. Traditional VCs, family offices, corporate development teams, and government capital are all now pushing in roughly the same direction.

International Partnerships and Tech Transfer

India isn't building deep tech in isolation. International partnerships are critical.

Qualcomm Ventures participating in the India Deep Tech Alliance signals that U.S. tech giants see value in Indian startups. Samsung, Intel, and other semiconductor makers are already partnering with Indian companies on design and development.

Space tech companies like Skyroot are getting expertise from international partners while maintaining India as their base. This is healthy cross-pollination, not brain drain.

The key is that India's policy creates the right environment for these partnerships. When foreign companies see that there's government support, patient capital, and a growing ecosystem, they're more likely to partner with Indian startups rather than competing against them.

The 20-Year Arc: Strategic Thinking

Here's something most analyses miss: the 20-year startup timeline is itself a statement about how India thinks about innovation.

Most government policies have 3-5 year horizons. Budget cycles, election cycles, political pressure—all of it creates pressure for short-term results. But deep tech requires thinking 15-25 years ahead.

By explicitly setting a 20-year timeline, India's government is saying: "We're thinking in decades, not quarters." That signals serious long-term commitment. It's the kind of horizon-setting that attracts patient capital and serious technical talent.

This is different from subsidies (which can be withdrawn) or tax breaks (which are temporary). It's a structural commitment embedded in how the government classifies and supports companies.

Of course, commitment can change with political leadership. But the framework is now in place. Reversing it would require a new government to actively dismantle something the previous government built. That's a higher bar than just not funding something new.

Metrics to Watch

Over the next 3-5 years, here are the metrics that will tell you whether this policy actually works:

Capital Deployed: How much of the ₹1 trillion RDI fund is actually deployed? By end of 2026, you should see at least ₹1,000-5,000 crores deployed through fund managers.

Company Creation: How many new deep tech startups incorporate? If policy is working, you should see an uptick in deeptech company formation in 2025-2026.

Follow-on Funding: Are Series B and Series C rounds growing? This measures whether companies are actually able to scale past the early stages.

International Capital: Are international VCs and corporate venture arms increasing their participation in Indian deep tech? This signals that global investors see a viable ecosystem.

Technical Milestones: Are companies hitting meaningful technical milestones (working chips, FDA approvals, successful launches)? Capital is necessary but not sufficient.

Talent Migration: Is emigration of deep tech talent stabilizing or reversing? If good engineers stay in India, that's a positive signal.

Exit Velocity: As the first cohort matures, what's the quality and size of exits? Successful acquisitions and IPOs prove the model works.

Common Misconceptions

Let me address a few misconceptions about what these changes do and don't do.

Misconception 1: "This means deep tech companies don't need to be profitable." False. They still need to be profitable eventually. The 20-year window just gives them time to reach that point. It's not a subsidy program; it's a recognition that some businesses take time.

Misconception 2: "All startups are now treated as deep tech." False. The policy explicitly differentiates deep tech (science and engineering-led) from other startups. Software companies, for example, still operate under traditional startup rules.

Misconception 3: "The RDI fund will solve the capital problem completely." Partially false. ₹1 trillion is significant but not unlimited. It's meant to be catalytic—opening the door so private capital follows.

Misconception 4: "This only benefits India." Partially true. Deep tech companies benefit from a global ecosystem. Indian deep tech companies will partner with, learn from, and compete with companies worldwide. That's good for global innovation even if India captures some returns.

Conclusion: The Significance of Incremental Change

At face value, doubling a startup designation period from 10 to 20 years doesn't sound revolutionary. But policy often works through small changes that compound.

What India has done is address a real constraint that was holding back deep tech entrepreneurship. Founders can now make long-term decisions. Investors can now fund companies through longer development cycles. The government is saying, explicitly, that building deep tech matters.

None of this guarantees success. Policy and capital are necessary but not sufficient. You still need talented teams solving real problems. You need manufacturing infrastructure, regulatory clarity, and market demand. But what India has created is the necessary foundation.

Where this matters most is in sectors where India has advantages: biotech leveraging research talent and low costs, semiconductors leveraging government commitment and fab partnerships, space tech building on ISRO expertise, and climate tech solving India-specific problems.

In 10 years, we'll know if this worked. We'll have a clearer picture of whether Indian deep tech can scale to global significance. We'll see if the first generation of companies built under these new rules achieved meaningful exits. We'll know if the RDI fund deployed capital effectively and attracted follow-on private capital.

For now, what matters is that India's government looked at deep tech, understood why it was struggling, and took structural action to fix it. That's less common than you might think. Most governments talk about wanting to build innovation ecosystems but don't commit the patient capital and policy flexibility required.

India did. Whether it pays off depends on execution. But the framework is now in place for deep tech entrepreneurship to flourish.

FAQ

What is deep tech and how does it differ from regular startups?

Deep tech refers to companies building on significant scientific or engineering breakthroughs—semiconductors, biotech, space technology, advanced materials, quantum computing, and similar fields. The critical difference from regular startups is the development timeline. A SaaS startup can launch in months and reach profitability in 2-3 years. Deep tech companies typically require 8-15 years of research, testing, regulatory approval, and manufacturing before generating meaningful revenue. That extended timeline is why policy matters—traditional startup frameworks were built for 3-5 year business cycles, not 15-year ones.

How does the extended 20-year startup designation help deep tech founders?

The 20-year designation removes what investors call the "false failure signal." Under the old 10-year framework, a semiconductor company operating exactly as planned (spending 8 years on R&D before commercialization) would suddenly lose startup status and access to government benefits right when it needed them most. The new 20-year timeline means companies can maintain startup status—and associated tax benefits, grants, and regulatory flexibility—through development, commercialization, and initial scaling. This removes perverse incentives to rush toward faster profits and lets founders focus on building the right technology.

What is the RDI Fund and how does it support deep tech startups?

The Research, Development and Innovation Fund is a ₹1 trillion ($11 billion) government-backed fund specifically designed to provide patient capital for science-led companies. Instead of bureaucrats picking winners, the fund deploys capital through established venture firms and private equity managers who make investments based on commercial criteria. The fund can provide equity, debt, and grants, making it flexible for different company needs. For a semiconductor startup needing ₹50 crores for manufacturing, it might provide a loan. For a biotech company in early research, it might provide a grant. This mixed-capital approach aligns with the reality of different deep tech needs at different stages.

Why is patient capital so critical for deep tech companies?

Deep tech ventures face a unique capital problem: they require substantial funding before generating revenue, but the timeline to revenue is long and uncertain. A traditional venture fund raising a 10-year fund might be too impatient for a biotech company that needs 12+ years to reach profitability. Patient capital—money explicitly committed to 15-25 year timeframes—solves this problem. It allows investors to provide capital without demanding premature profitability, and it allows founders to focus on technical progress rather than financial desperation. Without patient capital, many deep tech companies either raise at catastrophic valuations or simply never get founded.

How much venture capital is actually flowing into Indian deep tech?

Indian deep tech startups raised

What sectors benefit most from these policy changes?

Semiconductors, biotech, space technology, and climate tech see the most immediate benefits. Semiconductors benefit from government commitment to "Make in India" fabs and design partnerships. Biotech leverages India's research talent and generic pharma expertise. Space tech builds on ISRO's credibility and growing commercial demand. Climate tech solves India-specific problems (water scarcity, air quality, extreme heat) with global scalability. These sectors share common traits: they require patient capital, long development timelines, and play to India's existing strengths in talent and infrastructure.

Will these policy changes attract international investment to Indian deep tech?

Yes, already happening. The participation of Qualcomm Ventures, international VCs like Accel, and the emerging India Deep Tech Alliance signal that global capital sees potential. When foreign companies see government commitment, patient capital, and a growing ecosystem, they're more likely to invest. However, the absolute level of international capital in Indian deep tech remains smaller than in the U.S. or China. The next phase is whether exits (acquisitions, IPOs) prove the model works and trigger larger capital flows.

What are the remaining challenges for Indian deep tech to scale?

Talent concentration in software rather than specialized fields like semiconductors or biotech, manufacturing infrastructure costs (fabs require billions of dollars), customer concentration around government contracts, and regulatory approval timelines that lag the U.S. and Europe. The policy changes address capital and regulatory timeline issues but don't directly solve talent or infrastructure challenges. Those require sustained investment in education, manufacturing capacity, and regulatory development over many years.

Final Thoughts

India's update to its startup framework is one of the most underrated policy changes in global deep tech. It doesn't make headlines like a new mega-fund or a regulatory breakthrough. But it addresses a real constraint that was preventing deep tech entrepreneurship.

By recognizing that deep tech requires different timelines, committing patient capital through the RDI fund, and mobilizing private capital through the India Deep Tech Alliance, India is creating conditions where ambitious founders can tackle hard problems without artificial pressure to compromise their vision.

Will it work? That depends on execution, on whether the RDI fund is deployed wisely, on whether international partnerships deepen, and on whether the first generation of companies achieves meaningful exits.

But the framework is now there. And in innovation, having the right framework is often what makes the difference between thriving ecosystems and perpetual struggle.

For founders, investors, and anyone tracking where deep tech innovation happens, India is no longer a sideshow. It's a market worth paying attention to.

Key Takeaways

- India doubled the startup designation period from 10 to 20 years, removing the 'false failure signal' that previously penalized deep tech companies mid-development

- The ₹1 trillion RDI Fund deploys government capital through commercial venture managers, providing patient capital for Series A and later-stage deep tech startups

- Indian deep tech raised $1.65 billion in 2025, rebounding from 2 years of flat funding and signaling renewed investor confidence in the sector

- The policy change aligns perfectly with deep tech development timelines: semiconductors (6-10 years), biotech (10-15 years), and space tech (8-12 years) now have clear regulatory runways

- The India Deep Tech Alliance represents $1 billion+ in private capital from Accel, Qualcomm Ventures, Blume Ventures, and others, showing global VCs view Indian deep tech as viable

Related Articles

- Tech Billionaires At Super Bowl LIX: Inside Silicon Valley's $50K Power Play [2025]

- The 'March for Billionaires' Against California's Wealth Tax [2025]

- Epstein's Silicon Valley Network: The EV Startup Connection [2025]

- How Elon Musk Is Rewriting Founder Power in 2025 [Strategy]

- Reddit's Acquisition Strategy for 2025: Why Adtech & AI Matter [2025]

- Why Loyalty Is Dead in Silicon Valley's AI Wars [2025]

![India's Deep Tech Startup Rules: What Changed and Why It Matters [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/india-s-deep-tech-startup-rules-what-changed-and-why-it-matt/image-1-1770521770160.jpg)