Massive Phishing Campaign Targets Middle East Officials, Activists, Journalists [2025]

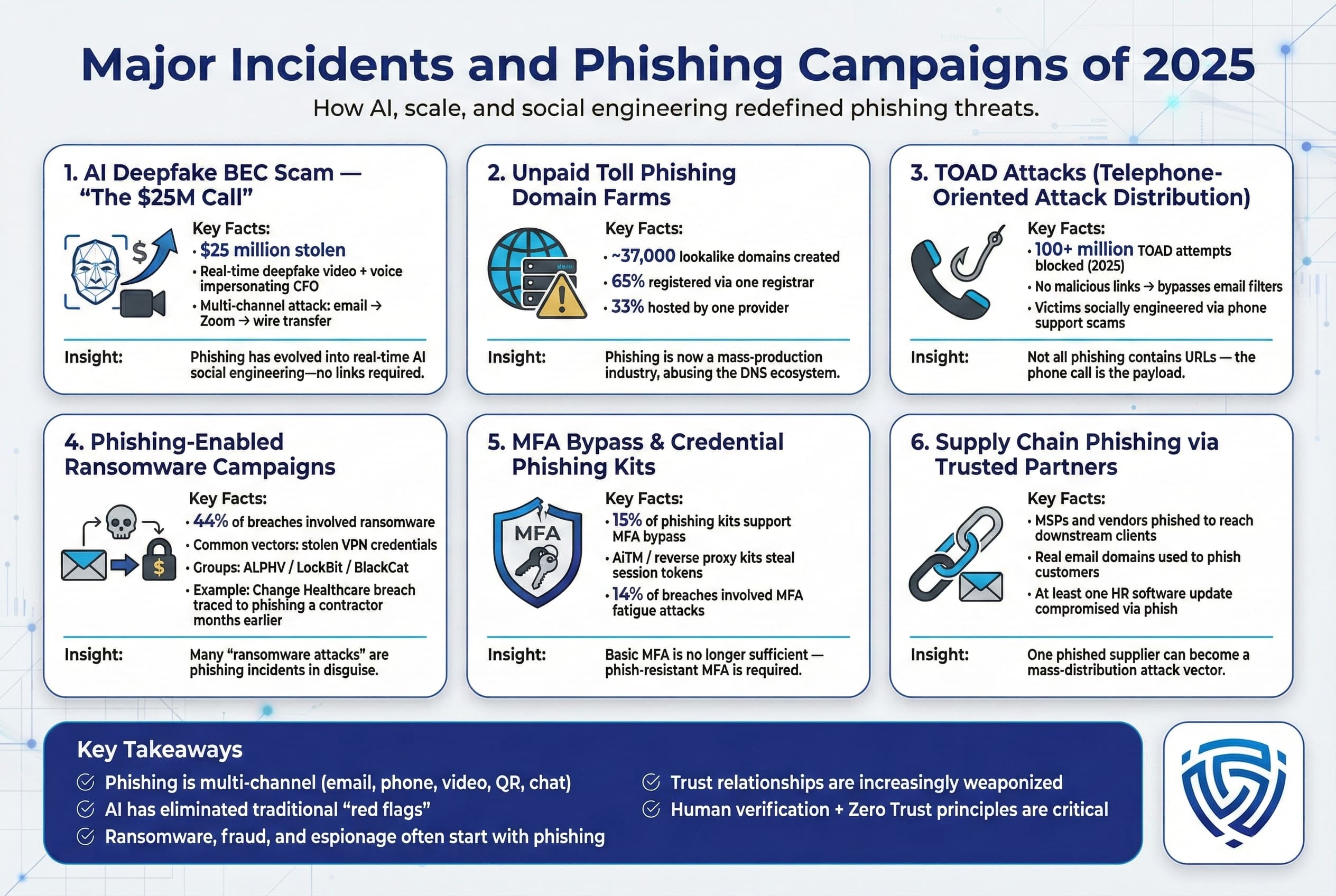

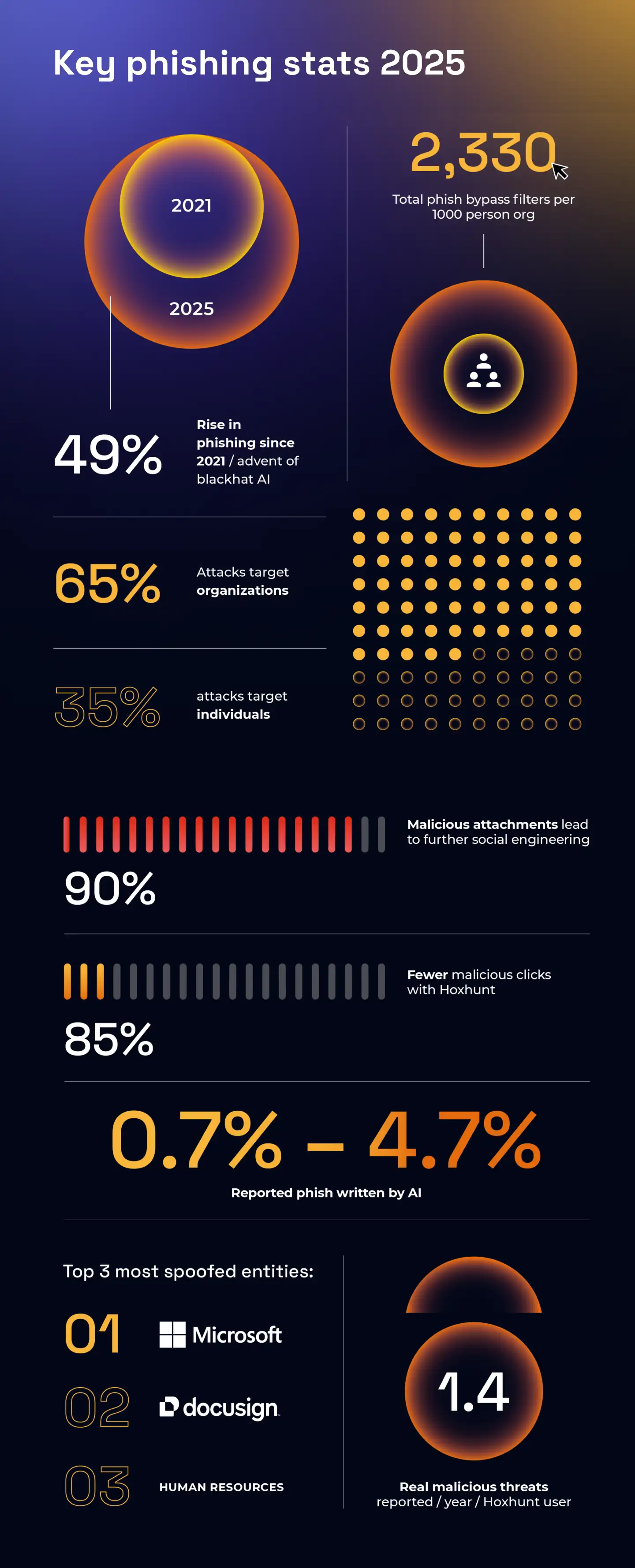

In January 2025, security researchers uncovered one of the most brazen and coordinated phishing campaigns ever documented targeting the Middle East. The operation systematically compromised hundreds of high-profile individuals, including government officials, human rights activists, journalists, and security researchers. What made this campaign particularly alarming wasn't just its scope, but its sophistication. The attackers didn't just steal credentials, they also deployed sophisticated surveillance tactics to monitor communications, capture location data, and record audio from compromised devices.

This wasn't a run-of-the-mill phishing attack sent to thousands with the hope that a few would fall for it. This was a surgical strike targeting specific individuals known for their work in sensitive areas: Iran-related activism, Middle Eastern politics, national security studies, defense contracting, and investigative journalism. The campaign exposed critical vulnerabilities in how we protect high-profile individuals in conflict zones and authoritarian regimes.

What's particularly chilling is how the attackers operated for an extended period, leaving their data servers completely exposed and accessible without any password protection. This critical oversight meant that anyone who discovered the phishing page could view real-time logs of every victim who had entered their credentials. For security researchers, it created a rare window into the operational tactics and victim lists of a highly targeted campaign.

The implications extend far beyond the immediate victims. The campaign highlights the evolving sophistication of cyberattacks targeting the Middle East, the increasing intersection between activism and digital security, and the alarming accessibility of surveillance capabilities to threat actors. Whether state-sponsored, criminal, or some hybrid operation, this campaign represents a new level of organized cyber-targeting that governments, companies, and at-risk individuals need to understand.

In this comprehensive analysis, we'll examine how the attack worked, who was targeted, what the attackers were trying to accomplish, and what this means for digital security in one of the world's most dangerous regions for activism and journalism.

TL; DR

- Sophisticated Campaign Scope: Hundreds of victims across multiple countries, including a Lebanese cabinet minister, journalists, activists, and national security researchers

- Multi-Stage Attack: Combined phishing, credential theft, WhatsApp account hijacking, and browser-based surveillance of location data, photos, and audio

- Critical Infrastructure Flaw: Attackers left their data server completely exposed, allowing researchers to view real-time logs of all victim interactions and stolen credentials

- Unclear Attribution: Evidence suggests government-linked actors, but cybercriminals or hybrid operations cannot be ruled out

- Attack Vector: WhatsApp messages containing malicious Duck DNS links that redirected victims to convincing phishing pages mimicking Gmail and WhatsApp login interfaces

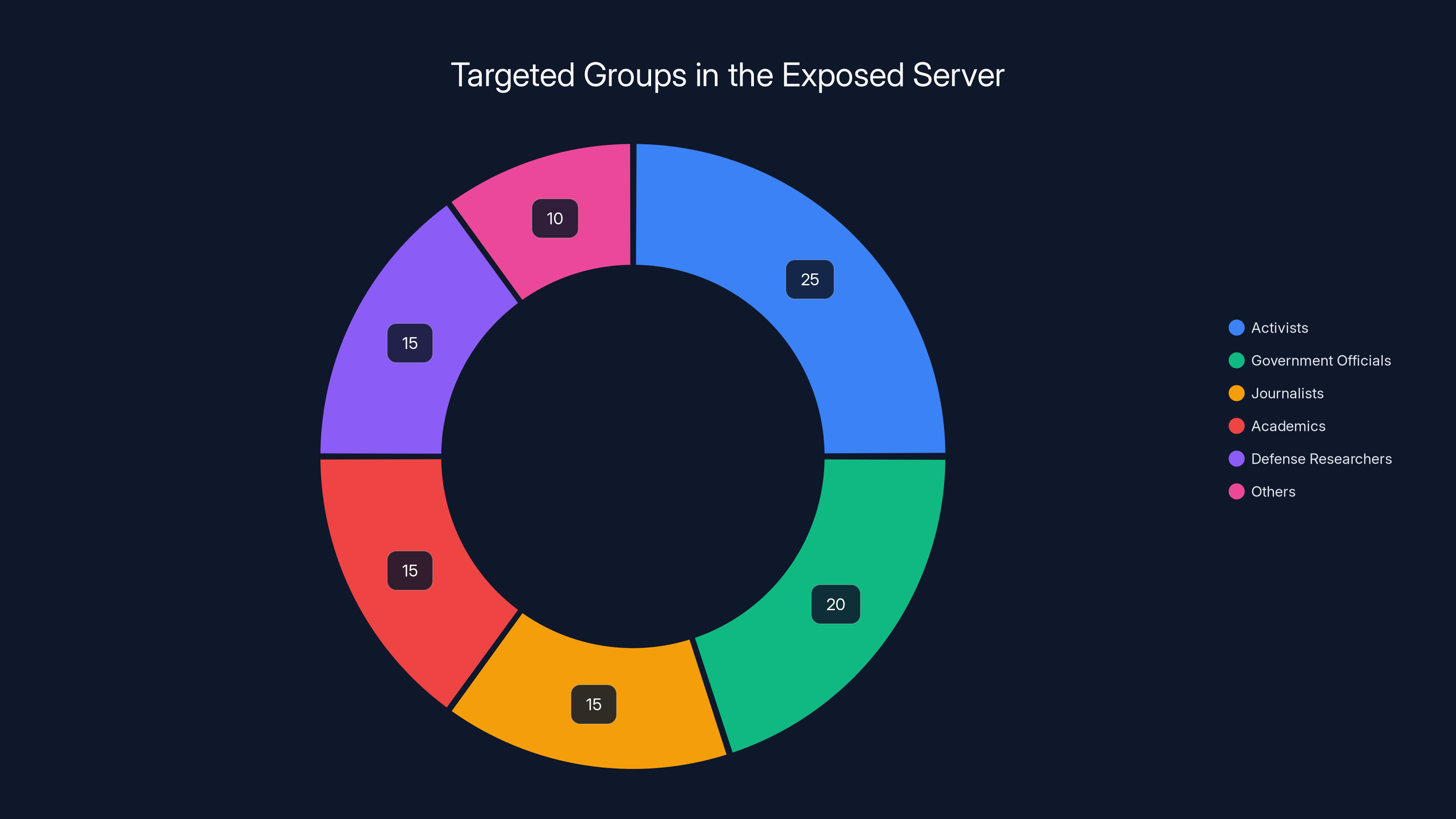

Estimated data suggests activists and government officials were primary targets, reflecting diverse objectives from personal security to intelligence gathering.

The Attack Begins: How Victims Received the Malicious Messages

The initial attack vector was deceptively simple yet highly effective. Victims received private messages on WhatsApp containing a single link. The message didn't include any obvious warning signs, making it appear as a legitimate notification or urgent communication.

When a victim clicked the link, they weren't immediately aware they were being compromised. The page that loaded looked remarkably similar to authentic WhatsApp or Gmail login interfaces. For most users, especially those using mobile devices, the difference between the real interface and the fake one would be nearly imperceptible. The attackers had invested significant effort in cloning the visual elements, layout, and functionality of these legitimate platforms.

What's noteworthy is that the attackers used WhatsApp itself as the delivery mechanism. This is particularly insidious because WhatsApp is widely used among activists, journalists, and security-conscious individuals as a secure communication platform. The assumption is that WhatsApp is encrypted end-to-end, so communications should be private. But the vulnerability here wasn't in WhatsApp's encryption. It was in the fundamental human tendency to click links sent by people who appear to be trusted contacts.

The attack likely exploited compromised accounts or compromised contact lists. In some cases, the messages may have come from contacts whose accounts had previously been breached. In other cases, sophisticated social engineering may have made the messages appear to come from legitimate sources. Messages might have included plausible context, like notifications about account security issues, verification requests, or urgent meeting invitations.

The timing of the messages was also strategic. The campaign was launched during a period of significant political upheaval in Iran, with nationwide protests and internet shutdowns creating an atmosphere of urgency and anxiety. For activists specifically monitoring the situation, a message that appeared to be security-related or protest-coordination-related would have been more likely to generate an immediate response.

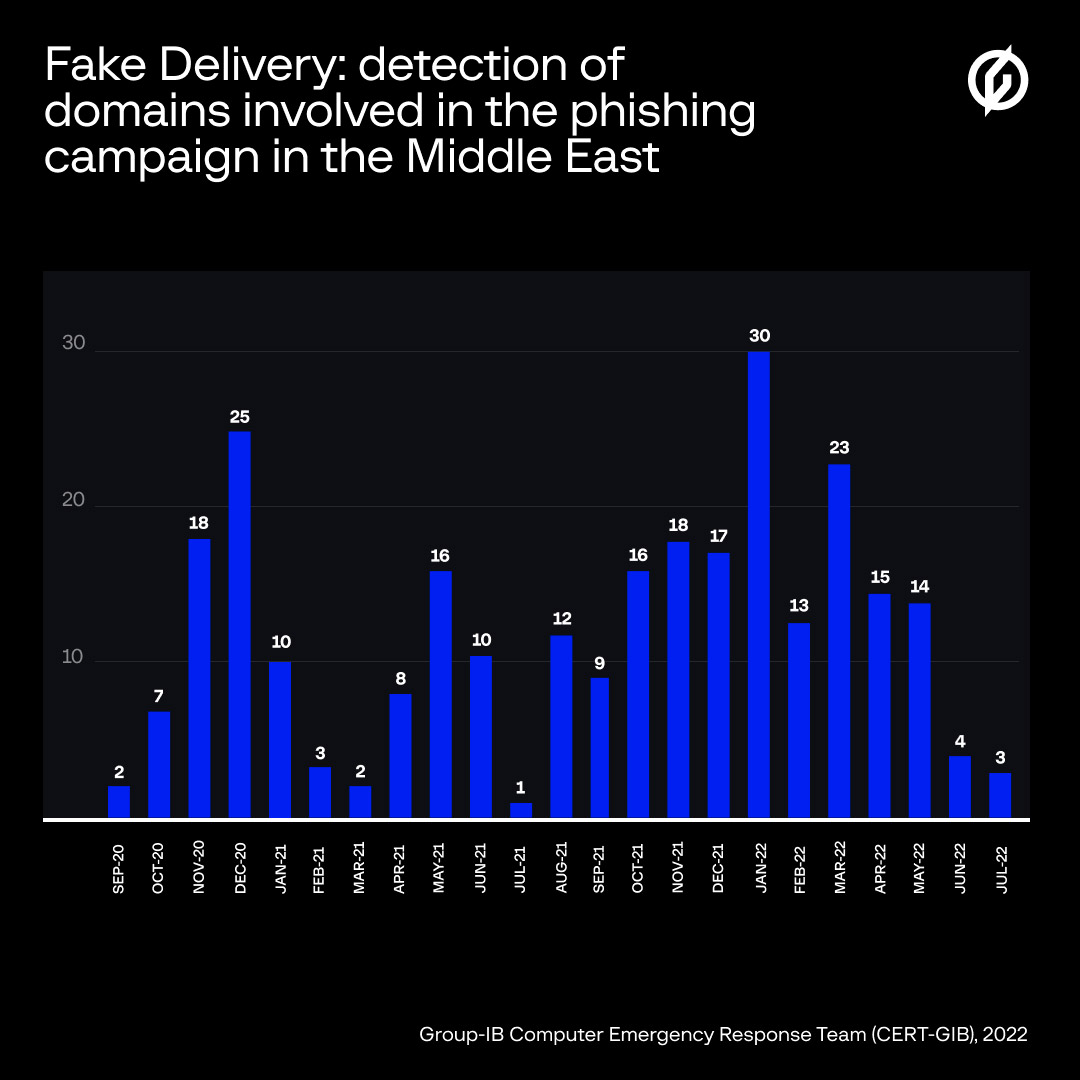

The phishing links used Duck DNS, a legitimate dynamic DNS provider. This service allows people to create easy-to-remember domain names (like somethinghere.duckdns.org) that point to servers with frequently changing IP addresses. Dynamic DNS is used legitimately by system administrators and remote access tools. But it's also frequently abused by attackers because it obscures the actual server location and can make it harder to track down the source of malicious content.

By using Duck DNS, the attackers created a layer of obfuscation. The link didn't point directly to a sketchy IP address. It pointed to what appeared to be a legitimate service. This added credibility and made the link less likely to be immediately flagged by security filters that might catch obviously malicious domains.

The Phishing Page: A Masterclass in Social Engineering

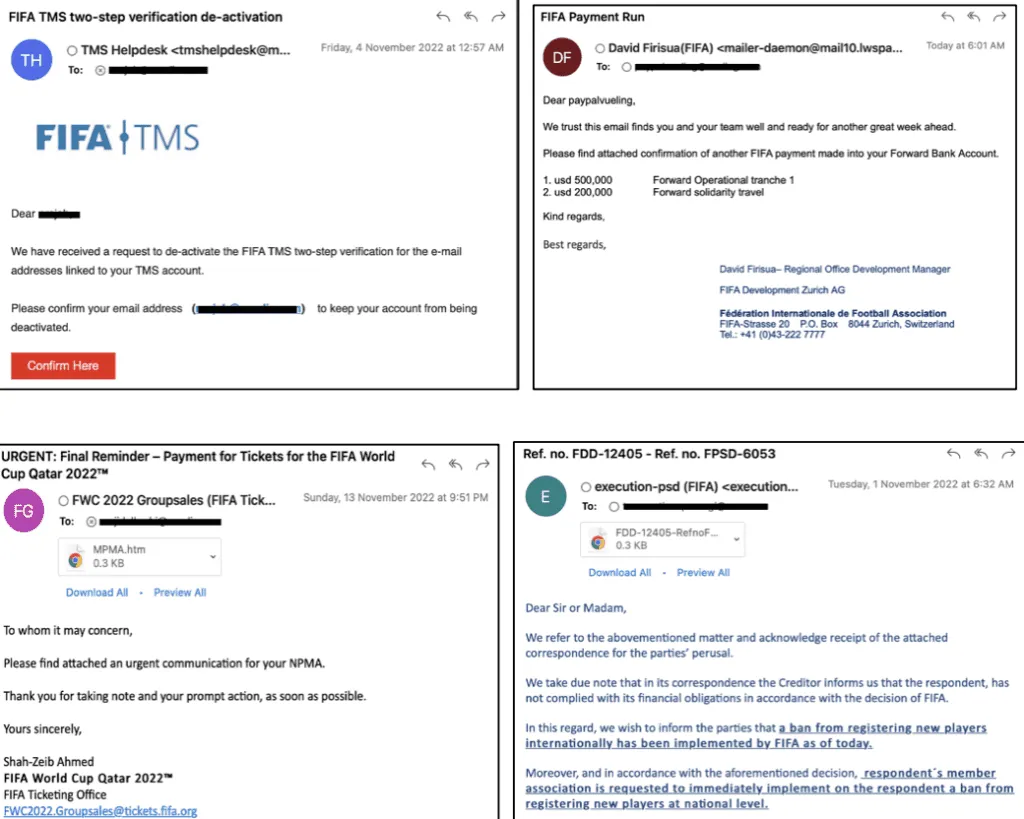

Once victims clicked the link, they were directed to a phishing page that represented a significant investment in attack infrastructure and user experience design. This wasn't a generic phishing page. It was customized, well-designed, and strategically crafted to match the exact context of the target's expected concerns.

For some victims, the phishing page displayed a Gmail login screen. For others, it displayed what appeared to be a WhatsApp interface with a QR code. The attackers appear to have used different variants depending on the specific target or their device characteristics.

The Gmail phishing page was particularly convincing. It included all the standard elements users expect: the Google logo, the familiar blue login button, password recovery options, and even the standard "Stay signed in" checkbox. For a user in the middle of a high-stress situation, especially someone unfamiliar with the technical details of how phishing works, the page would appear completely legitimate.

When a victim entered their email address and password, the phishing page captured this information. But it didn't immediately grant access or display an error message that might alert the user to something being wrong. Instead, it triggered a two-factor authentication screen, asking for a code sent via text message.

This is where the attack becomes sophisticated. The attacker's page didn't need to actually generate a real two-factor code. It just needed to prompt the user to enter the code they had legitimately received from Google. When the victim typed in their six-digit code (the format that Google uses is highly recognizable, usually starting with "G-" followed by six numbers), the phishing page captured this as well.

Now the attacker had everything needed to access the victim's Google account: the email address, the password, and the two-factor authentication code. In the case of two-factor authentication via SMS, a single code is typically valid for only a few minutes. But during those few minutes, the attacker could immediately use the credentials to access the victim's email account from the attacker's own device.

The WhatsApp variant of the phishing page took a different approach. Instead of asking for credentials, it displayed a QR code and explained that scanning the code would allow the user to access a virtual meeting room or verify their account status. In reality, this QR code would have initiated WhatsApp's device linking feature when scanned.

WhatsApp's device linking feature is designed for legitimate purposes. It allows users to access WhatsApp on a web browser or desktop application by linking their phone to that device. The process requires scanning a QR code displayed on the new device using WhatsApp on the original phone. This is actually a pretty clever security measure because it ensures that the person linking a new device physically has the phone.

However, the attacker's QR code was generated by the attacker, not by WhatsApp. When a victim scanned it, they were effectively linking their WhatsApp account to a device controlled by the attacker. From that moment forward, the attacker could access all of the victim's WhatsApp conversations, contacts, and account information. The attacker could also impersonate the victim in WhatsApp conversations.

What's particularly sinister is that the victim might not immediately realize their account had been compromised. WhatsApp doesn't always send obvious notifications when a device is linked. The victim might continue using WhatsApp normally, unaware that someone else was simultaneously monitoring every message.

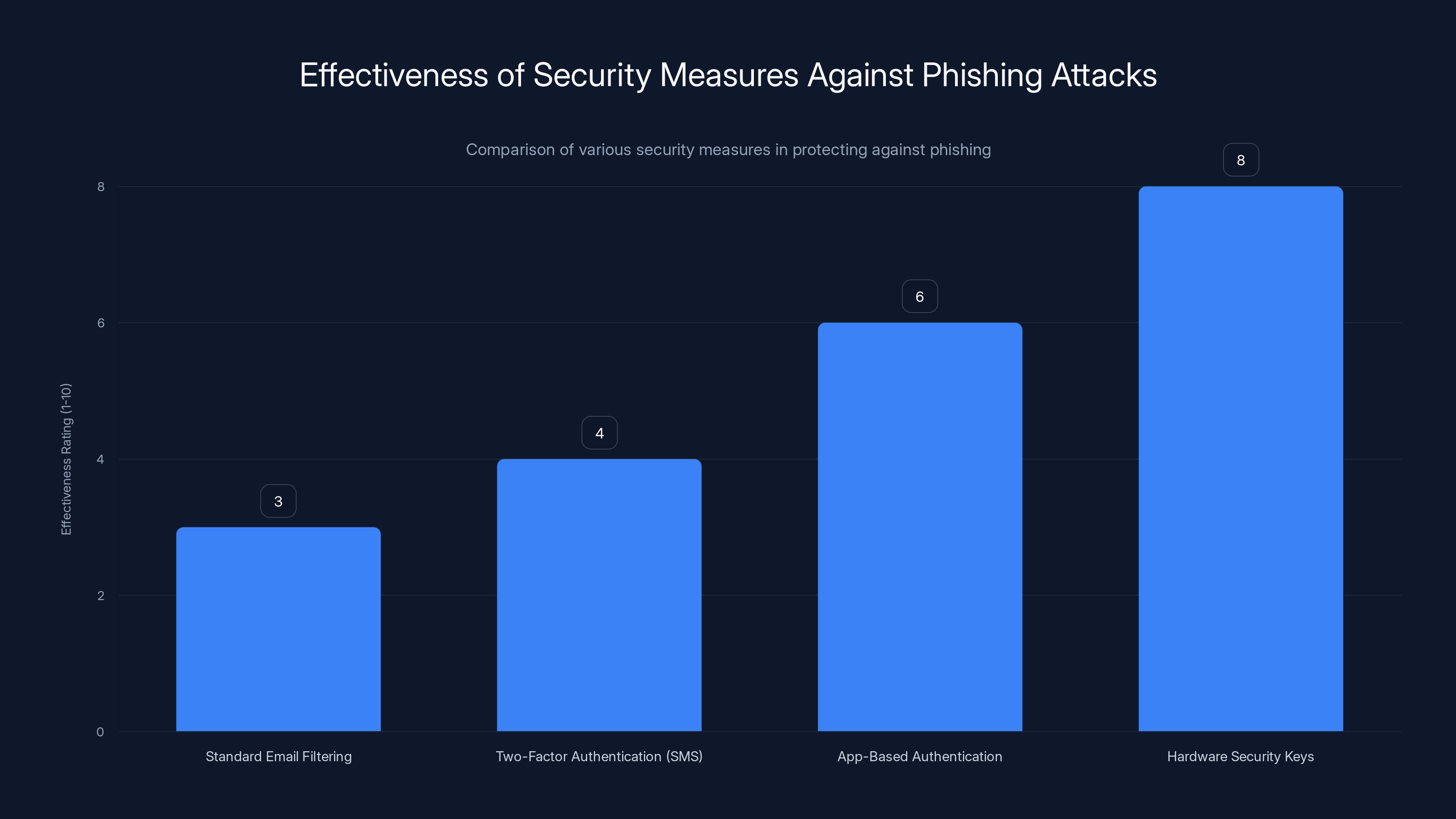

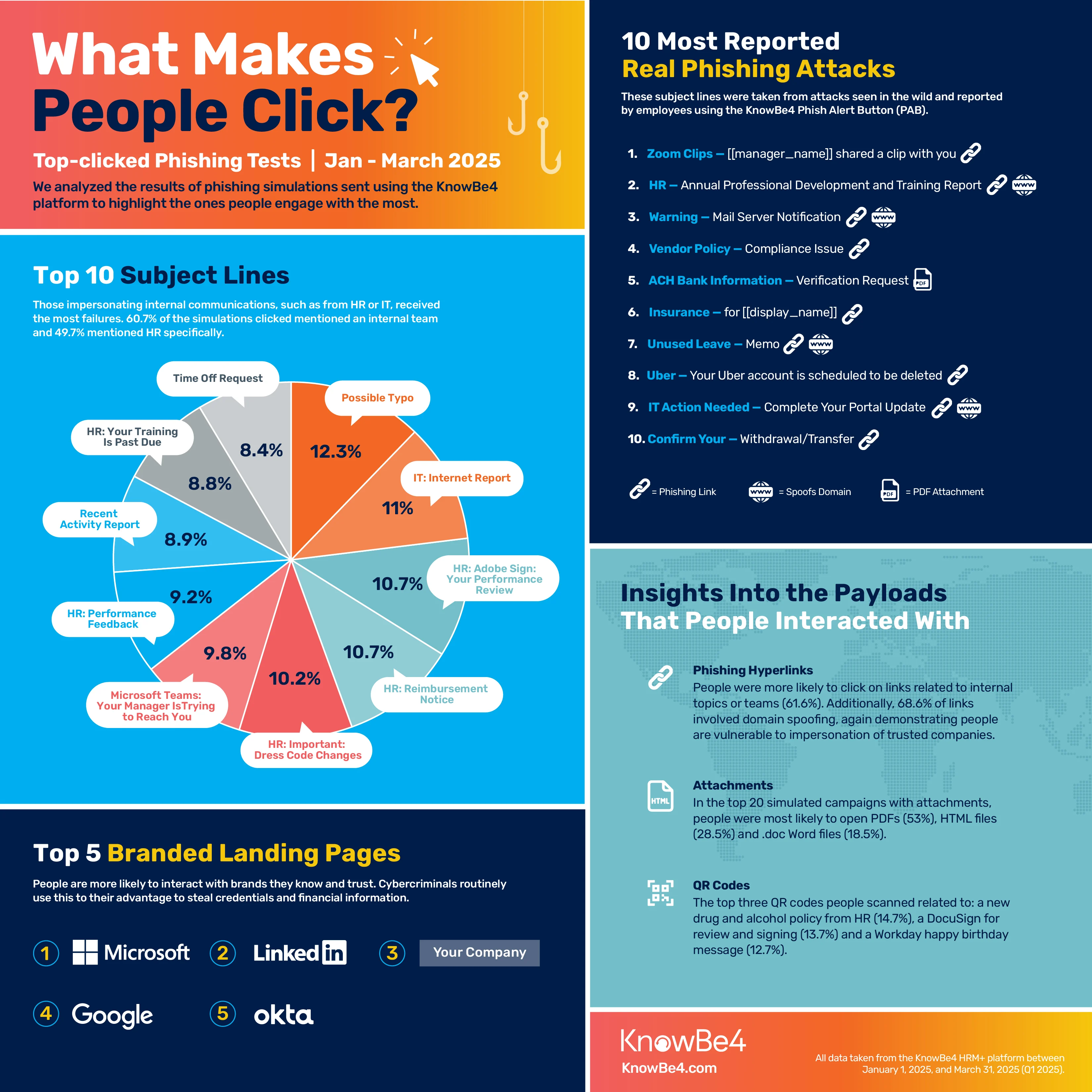

Hardware security keys are the most effective against phishing attacks, followed by app-based authentication. Estimated data based on typical security assessments.

The Surveillance Layer: Beyond Credential Theft

But the attackers' ambitions extended beyond stealing credentials and hijacking accounts. The phishing page source code contained additional JavaScript code designed to extract more sensitive information from victims' devices.

When the phishing page loaded in a victim's browser, the JavaScript code would request permission to access the victim's browser notifications. This might seem like an odd thing to request, but it's actually a clever way to access other device capabilities. Once notification permission is granted, the code could potentially escalate permissions to access the victim's location data, photos, and audio recordings.

Location data is particularly valuable for someone trying to surveil an activist or journalist. Knowing where someone is in real-time or seeing their location history can reveal patterns: where they meet sources, where they sleep, where they spend time. For activists in authoritarian regimes, location data is a security nightmare.

Access to photos is similarly valuable. It could reveal documents, meeting notes, faces of other activists or sources, or anything else the victim has photographed. Access to audio recordings could capture secret meetings or interviews.

The browser's ability to access location, photos, and audio is normally restricted. Websites can't just grab this data. But browsers do allow websites to request this permission from users. If a user grants the permission, the website gets access. The key is getting the user to grant the permission.

In this attack, the phishing page likely presented a convincing request for these permissions, perhaps framing them as necessary for a "secure video call," "location verification," or "file upload" feature. A user in the middle of a stressful interaction might grant these permissions without thinking carefully about the implications.

The Critical Error: Exposed Data Server

While the attack was sophisticated in many ways, the attackers made a critical operational error. They left their data server completely exposed and accessible without any password protection.

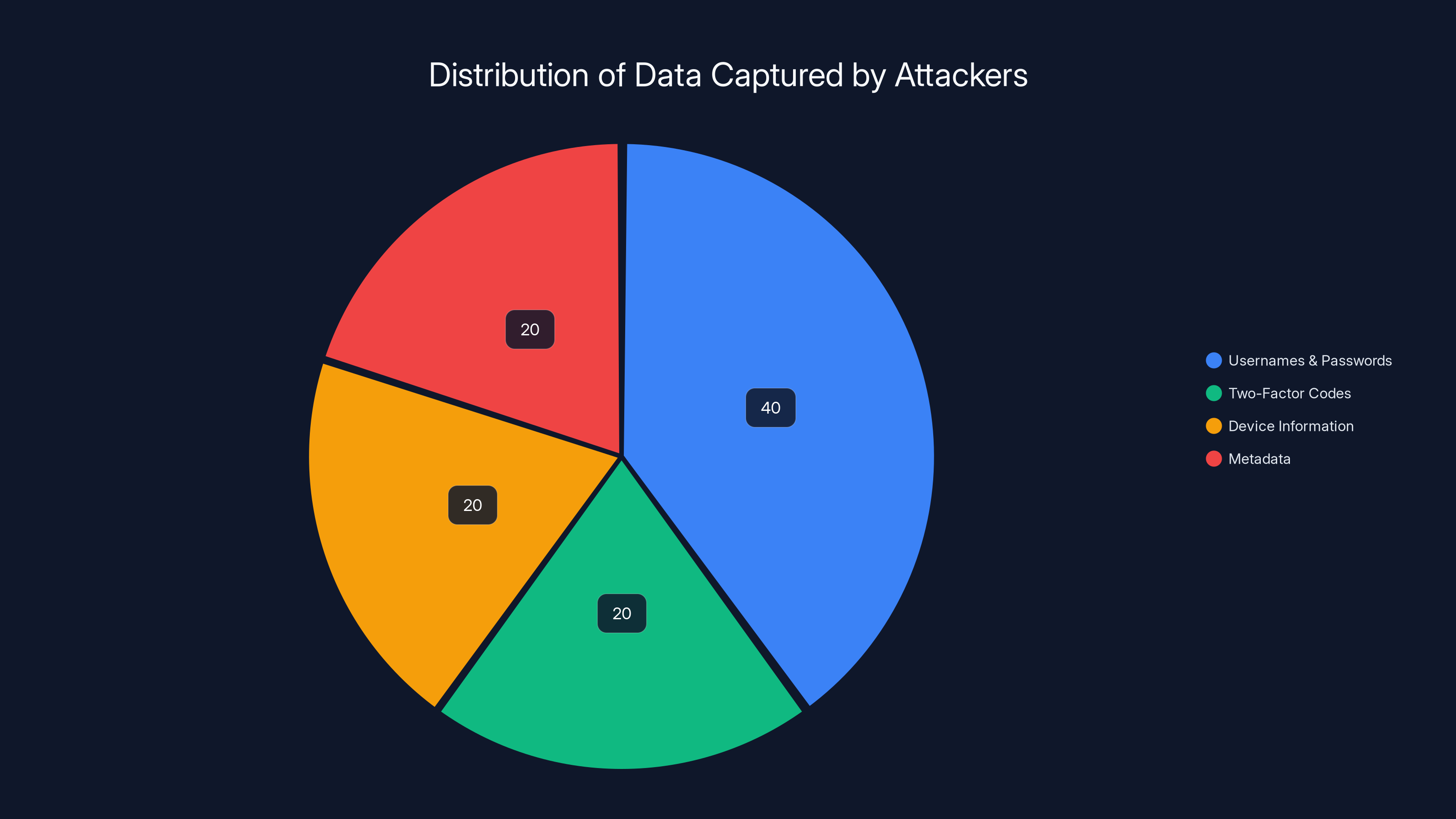

The phishing page source code contained JavaScript that would POST (upload) all captured information to the attacker's server. This included usernames, passwords, two-factor authentication codes, device information, and any other data extracted from victims. However, the attacker also left a file on the server that contained a log of all these submissions.

By modifying the URL in a web browser, security researchers were able to access this log file directly. It wasn't encrypted, it wasn't password-protected, it was just sitting there on the internet for anyone to find. The file contained over 850 records of victim interactions.

Each record showed the complete attack flow for that victim. For victims who had entered their credentials, the record included the exact username and password they entered. For victims who had entered incorrect passwords, the record showed the incorrect attempt. For victims who had completed the two-factor authentication step, the record included the six-digit code.

The data also included metadata about each victim: their user agent (which reveals the operating system, browser type, and browser version), the time they accessed the page, and the specific attack flow variant they encountered. This metadata alone is valuable for understanding the victim profile the attackers were targeting.

For security researchers, having access to this data was both a blessing and a curse. It provided unprecedented insight into the scope and targeting of the campaign. But it also meant that the researchers had to carefully handle the information to avoid exposing the victims or potentially causing additional harm.

The exposed server didn't just contain the logs. It likely contained the attacker's infrastructure configuration, cloned HTML pages, JavaScript code, and potentially information about how the phishing campaign was coordinated. It was a window into the attacker's entire operation.

Who Was Targeted: A Cross-Section of Influence and Sensitivity

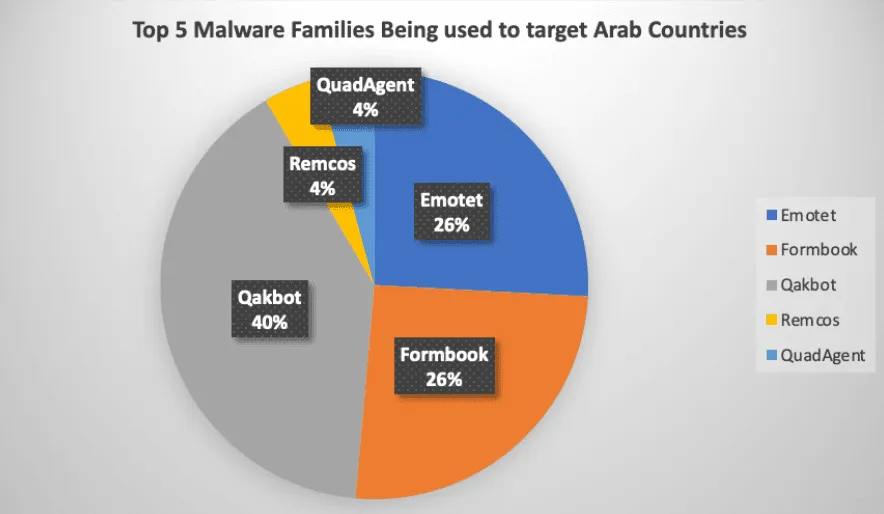

The victim list extracted from the exposed server revealed a carefully selected target set. This wasn't random. This was strategic.

One of the highest-profile victims was Nariman Gharib, a U.K.-based Iranian activist and researcher who has been following digital activism and government surveillance in Iran for years. Gharib's focus on Iran-related activities and digital security made him a logical target for someone trying to monitor Iranian diaspora activism or understand how anti-government sentiment was being coordinated.

But Gharib wasn't the only high-profile victim. The data logs included the credentials of a senior Lebanese cabinet minister. In a country where political instability is constant and foreign intelligence operations are well-documented, compromising a cabinet minister's email account is a significant intelligence victory.

The victim list also included at least one journalist, though specific names were redacted from public reporting to protect privacy. Compromising journalists' email accounts can provide insight into their sources, ongoing investigations, and editorial decision-making.

Beyond these high-profile individuals, the victim list included academics specializing in Middle Eastern national security, researchers at Israeli defense companies, people with U.S. phone numbers or U.S. affiliations, and people involved in various aspects of activism and policy work related to the region.

The geographic and professional diversity suggests multiple targeting objectives. Some attackers might have been interested in personal security (targeting activists), others in government intelligence (targeting cabinet ministers), others in corporate espionage (targeting defense contractors), and others in journalist surveillance (targeting reporters).

This diversity actually points toward a possible explanation: the phishing infrastructure might have been built by one group but used by multiple groups. Alternatively, it might have been built by a sufficiently large organization with diverse intelligence priorities.

Estimated data shows equal involvement of key stakeholders in addressing sophisticated cyber threats. Each group plays a crucial role in enhancing cybersecurity measures.

The Attack Methods: A Technical Breakdown

The complete attack chain involved several sophisticated techniques layered together.

The first layer was social engineering. The victim received a message on WhatsApp, a platform they trusted. The message appeared to come from a legitimate contact or was framed as urgent or important. This psychological element is critical. No technical security measure can entirely prevent a victim from clicking a link if they believe the message is important.

The second layer was infrastructure obfuscation. The link didn't point to a sketchy IP address. It pointed to a Duck DNS domain, a service that's used legitimately by thousands of system administrators. This made the link less suspicious and potentially less likely to be caught by security filters.

The third layer was visual authenticity. The phishing page looked like Gmail or WhatsApp. It included logos, colors, layout, and interaction patterns that users expected. A user who was stressed, busy, or distracted might not notice subtle differences.

The fourth layer was interaction capture. When victims interacted with the phishing page, every keystroke was captured and uploaded to the attacker's server. Passwords, two-factor codes, and other information were collected.

The fifth layer was permissions escalation. The phishing page tried to request access to device capabilities like location, photos, and audio. These permissions would grant the attacker ongoing access to sensitive information.

The sixth layer was account hijacking. For WhatsApp victims, the attacker could link the victim's account to a new device. For Gmail victims, the attacker had the credentials needed to access the account directly.

The seventh layer was infrastructure exposure. The attackers left their data server exposed, which allowed researchers to understand the scope of the campaign. This was an operational error, but it also provided critical evidence about the attack's effectiveness.

Attribution: Who Was Behind the Campaign?

Determining who conducted this campaign is extraordinarily difficult. The evidence points toward multiple possible culprits, and it's possible that multiple actors were involved.

State-sponsored actors are certainly a possibility. Iran, Israel, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and other Middle Eastern states are all known to conduct sophisticated cyber operations. The targeting pattern (focusing on Iran-related activists, Middle Eastern security officials, and journalists) suggests someone with strong intelligence interests in the region.

Iranian government agencies would have obvious interest in monitoring diaspora activists and understanding anti-government coordination. Israeli agencies would have interest in monitoring Middle Eastern security developments and political instability. Saudi and UAE agencies would have interest in monitoring journalists and political opposition.

But the operation could also be the work of sophisticated cybercriminals. Stealing credentials from hundreds of high-profile individuals could be valuable for identity theft, extortion, or resale to other cybercriminals or intelligence services. The investment in building the infrastructure suggests significant resources, but sophisticated criminal organizations have substantial resources.

The operation could also be a hybrid. Some governments contract out cyber operations to private firms or criminal syndicates. A private firm might build the phishing infrastructure and sell access to multiple government agencies. An intelligence service might use a criminal front to conduct operations that would be difficult to attribute.

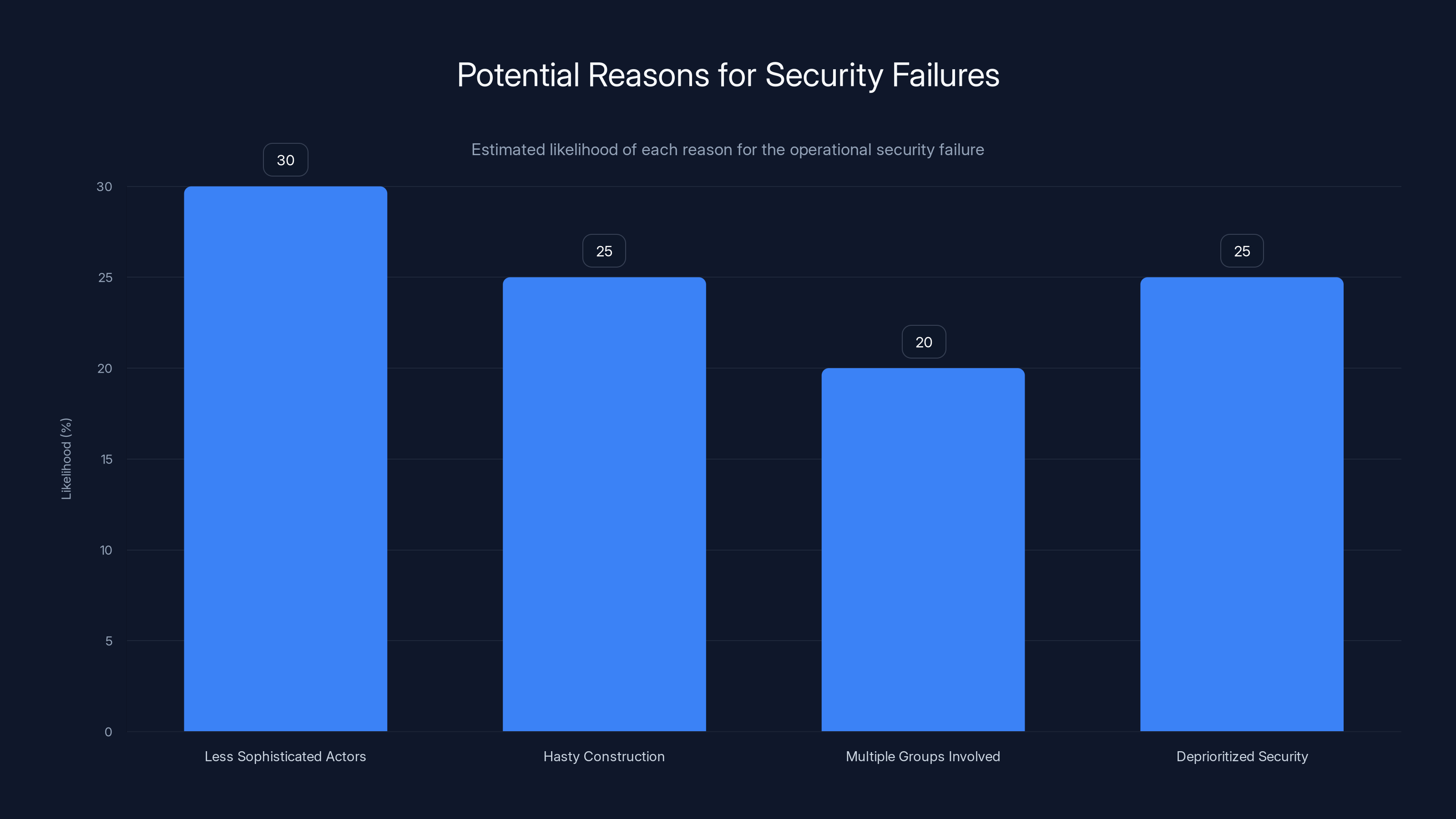

The exposure of the data server, while critical for security researchers, actually hampers attribution. In a properly operated attack, no such exposure would occur. The exposure suggests either a significant operational security failure or the involvement of less sophisticated actors. This actually makes attribution even more uncertain.

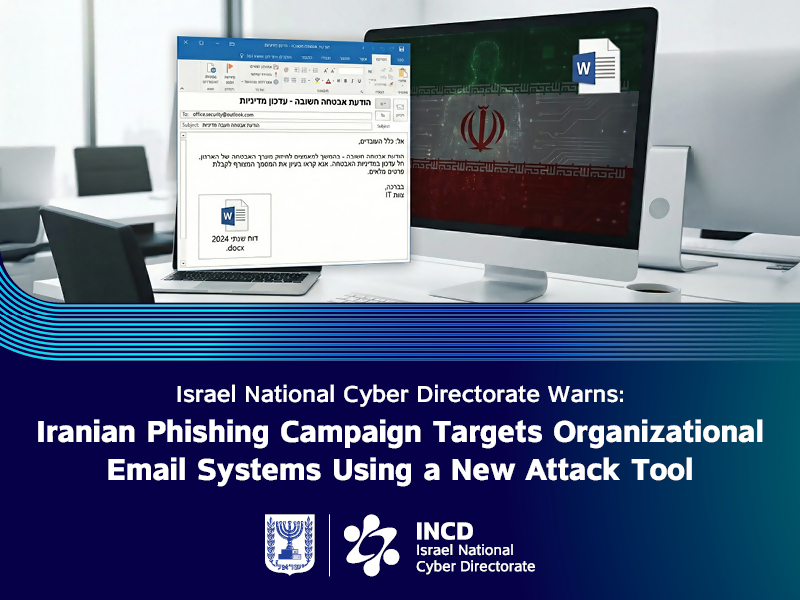

The Iranian Context: Why This Campaign Matters Now

The timing of this campaign is important. It occurred during a period of significant political upheaval in Iran. Nationwide protests against the government were ongoing. An internet shutdown had been implemented. There were violent clashes between protesters and security forces.

In this context, diaspora activism becomes particularly important. Iranians living abroad, activists, journalists, and researchers outside the country can provide outside perspective, coordinate international support, and document what's happening without being subject to direct Iranian government control.

For Iranian security agencies, understanding and disrupting these diaspora networks would be a priority. Compromising the accounts of diaspora activists could provide insight into how they're coordinating, who their contacts are, what information they're sharing, and what resources they're receiving.

For other regional actors, understanding diaspora activism provides broader intelligence. Understanding how Iranians are organizing outside the country provides insight into internal sentiment and organization.

For international journalists and researchers, the campaign highlights the extreme risks of covering Middle Eastern politics. A simple message on WhatsApp could compromise years of reporting and endanger sources.

Estimated data shows that usernames and passwords constituted the largest portion of captured data, highlighting the attackers' focus on credential theft.

Credential Theft Implications: What Attackers Can Do With Stolen Passwords

When an attacker has someone's Gmail password and has captured their two-factor authentication code, they have essentially full access to that person's email account. This access is devastating.

Email is the central hub of most people's digital lives. Almost every other account (social media, banking, work systems, cloud storage) can be accessed or reset using email. An attacker with email access can:

- Reset passwords for other accounts using the "Forgot Password" recovery option

- Access sensitive communications, including messages from sources, colleagues, family, and friends

- Monitor ongoing conversations and projects

- Impersonate the victim by sending emails that appear to come from their account

- Access files stored in cloud services connected to the email account

- Understand the victim's locations, routines, and relationships through stored emails and calendar invitations

For a journalist, email compromise is a professional and personal disaster. Sources will be exposed. Ongoing investigations will be revealed. Collaboration with colleagues or foreign news organizations will be compromised.

For an activist, email compromise reveals connections to other activists, funding sources, international contacts, and operational details.

For a government official, email compromise reveals policy discussions, political relationships, and sensitive government information.

The attacker doesn't need to immediately use the compromised account. They could lurk quietly, reading emails for months while the victim is unaware. They could gradually extract information. They could set up filters to hide certain emails so the victim doesn't realize the account has been compromised.

WhatsApp Hijacking: The Device Linking Attack

The WhatsApp attack vector deserves particular attention because it represents a different threat than credential theft. In this variant, the attacker wasn't trying to steal the victim's password. Instead, the attacker was trying to get the victim to link their WhatsApp account to a device controlled by the attacker.

WhatsApp's device linking feature exists for legitimate purposes. It allows you to use WhatsApp on your phone and also access it from a web browser or desktop application. This is convenient. But it requires that you physically have your phone to scan a QR code displayed on the new device. This physical requirement is actually a security measure.

The phishing page bypassed this security measure through social engineering. Instead of asking the victim to scan a QR code on a new device, the attacker presented a QR code to the victim and told them that scanning it would do something legitimate (like verify their account or join a meeting).

When the victim scanned the QR code with their phone's camera, their WhatsApp app interpreted the code as a device linking request and automatically completed the linking process. From that moment forward, the attacker's device had access to the victim's WhatsApp account.

This is more subtle than stealing a password because the victim might not immediately notice. They would continue using WhatsApp on their phone normally. But the attacker would have simultaneous access to all of the victim's conversations.

For activists and journalists, WhatsApp is often used to communicate with sources and coordinate with colleagues. The assumption is that end-to-end encryption keeps these conversations private. And technically, the encryption does keep them private from WhatsApp servers or network eavesdroppers. But it doesn't protect against someone who has linked their phone to the account.

The Role of Browser Permissions and Surveillance

The phishing page's attempt to request browser permissions for location, photos, and audio represents an additional layer of surveillance capability.

Browser APIs now allow websites to request access to device hardware. A website can ask for permission to access your microphone, camera, location, photos, clipboard, and other resources. This is designed to enable legitimate features like video conferencing or location-based services.

However, these permissions are also powerful surveillance tools. If an attacker can convince a user to grant location permission, the attacker can determine the user's real-time location. If the attacker can get access to the photo library, the attacker can see everything the user has photographed, including documents, meeting notes, or faces of other people.

Audio access is particularly valuable for surveillance. With audio recording capability, an attacker could record conversations that the victim has in the presence of their device. For someone meeting with a source, a source location could be determined from the audio or from the location data collected during the meeting.

The phishing page likely presented these permission requests as necessary for a feature the victim wanted (like a video call). A user in the middle of an urgent interaction might grant the permissions without thinking about the implications.

The chart estimates the likelihood of various reasons behind the security failure, with 'Less Sophisticated Actors' and 'Deprioritized Security' being the most probable causes. Estimated data.

Infrastructure and Operational Security Failures

The exposure of the attacker's data server on the internet without password protection is a massive operational security failure. For a campaign of this sophistication, this failure is surprising.

In a properly operated attack, the data server would be:

- Password-protected with strong credentials

- Accessible only through a VPN or from specific IP addresses

- Not directly connected to the internet but accessible through an authenticated endpoint

- Encrypted so that even if accessed, the data would be unreadable

- Isolated from other infrastructure so that compromise of the data server doesn't compromise other systems

The failure to implement basic security practices suggests either:

- The operation was conducted by less sophisticated actors than typical state-sponsored operations

- The infrastructure was hastily constructed to address an urgent need

- The operation was conducted by multiple groups with different security practices

- The infrastructure was being actively used and securing it was deprioritized in favor of rapid deployment

It's also possible that the exposure was discovered and exploited by a rival group who could have potentially modified data, added false entries, or used the access for other purposes.

Detection and Defense: Protecting Against These Attacks

The sophistication of this phishing campaign highlights gaps in how we protect at-risk individuals.

Standard email filtering might have caught some malicious links, but determined attackers can often bypass filters. The use of legitimate services like Duck DNS makes filtering harder. The timing on WhatsApp (not email) avoids email filtering entirely.

Two-factor authentication protects against credential theft, but it's only effective if the two-factor codes aren't also captured during the phishing attack. This is why app-based authentication (like Google Authenticator or Authy) is stronger than SMS. SMS codes can be intercepted or captured. App-based codes are generated locally on the device and can't be captured by a website.

Hardware security keys (like YubiKey or Google Titan) are even stronger. They require physical interaction and can't be fooled by phishing pages.

For high-risk individuals, security practices need to be more rigorous:

- Use hardware security keys for critical accounts

- Be extremely skeptical of unexpected messages, even from known contacts

- Verify important communications through a secondary channel

- Keep devices updated with the latest security patches

- Use antivirus software and endpoint security tools

- Monitor account activity logs for suspicious access

- Consider using separate devices for different purposes (a device for activism, a separate device for daily life)

- Educate yourself and others about phishing tactics

For organizations and security teams, this campaign highlights the need for:

- Threat intelligence about targeting patterns in the region

- Incident response capabilities for helping compromised individuals

- User education programs that focus on realistic threats

- Monitoring of emerging phishing techniques and infrastructure

- Collaboration with international partners to identify and disrupt attacks

The Broader Implications: Cybersecurity in Conflict Zones

This campaign is emblematic of a broader trend. As political conflicts become increasingly digital, the line between physical violence and cyber violence blurs.

Activists, journalists, and officials in conflict zones face cyber threats that are often more damaging than physical threats. A physical attack might injure one person. A successful phishing attack might compromise dozens of people and years of work.

For activists trying to document human rights abuses or organize political opposition, the threats are constant. For journalists trying to investigate government corruption or war crimes, being compromised is an occupational hazard. For officials trying to navigate political instability, cyber threats to their accounts are as serious as threats to their personal security.

The international response to cyber threats in conflict zones has been slow. There's no agreed-upon legal framework for cyberwarfare. Attribution is difficult, which makes consequences hard to enforce. Tools and techniques are difficult to regulate.

Yet the need for protection is urgent. As we've seen in this campaign, the barriers to entry for sophisticated phishing operations are actually quite low. You don't need to be a nation-state. You don't need cutting-edge zero-day exploits. You need basic web development skills, some social engineering savvy, and access to legitimate services like Duck DNS.

What you do need is a clear target list, a specific objective, and a willingness to invest time and resources. For state-sponsored operations or well-funded criminal organizations, these requirements are easily met.

This pie chart estimates the distribution of targeted groups in the phishing campaign, with government officials and journalists being the most targeted. Estimated data.

Incident Response: What Happens After Compromise

For the victims of this campaign, discovering their compromise is a critical moment. The correct response can minimize damage. The wrong response can make things worse.

If someone realizes their Gmail account has been compromised, the first step is to immediately change the password from a secure device using a different network if possible. The second step is to check what other accounts are recoverable through the compromised email address and change those passwords as well. The third step is to check account activity logs to see what the attacker accessed and when.

For WhatsApp hijacking, the victim should open WhatsApp on their phone and check for any devices that have been linked. They should unlink any unfamiliar devices. They should also notify their contacts that their account may have been compromised.

Beyond immediate response, victims need to consider whether their communications with sources, colleagues, or others may have been exposed. They need to understand what information was available to the attacker and what the potential consequences are.

For journalists, this might mean notifying sources that their identities may have been compromised. For activists, this might mean warning others in their network. For government officials, this might trigger investigation or security briefings.

Victims should also consider whether the attack itself is newsworthy. If they're a journalist or public figure, being targeted by a sophisticated campaign might itself be a story worth reporting.

Future Campaigns: What We Can Expect

If this campaign is any indication, we should expect future phishing campaigns to become more sophisticated, more targeted, and more effective.

Attackers will continue to leverage legitimate services like Duck DNS and others to obfuscate infrastructure. They'll continue to use social engineering and psychological pressure to overcome user caution. They'll continue to expand their collection objectives beyond credentials to include location data, media, and recordings.

What we might see in future campaigns:

- More sophisticated profile-specific phishing pages that reference things specific to the target

- Integration with other attack vectors (combining phishing with malware or zero-day exploits)

- More sophisticated two-factor authentication bypassing techniques

- Longer dwell times where attackers maintain access to compromised accounts for weeks or months before exploiting the access

- More coordination between multiple attackers sharing infrastructure or victim lists

- More targeted attacks on secure communication platforms like Signal, Telegram, and ProtonMail

The ultimate defense against these threats is awareness. The more people understand how these attacks work, the harder it becomes for attackers to be successful. This is why campaigns like the one documented in this article are important to analyze and disseminate.

Lessons for Organizations and Security Teams

If your organization includes people who work on sensitive issues (politics, human rights, investigative journalism, national security), this campaign should prompt immediate action.

Start with a threat assessment. Who in your organization might be targeted? What information do they have that would be valuable to potential attackers? What access do they have to sensitive systems or communications?

For high-risk individuals, implement stronger authentication. Hardware security keys should be mandatory. App-based two-factor authentication should be required. Account activity monitoring should be regular.

Educate your team about phishing. Don't just make them watch a video. Make phishing training realistic. Run test phishing campaigns to identify who's vulnerable. Provide specific feedback.

Implement monitoring. Watch for suspicious account activity. Set up alerts for access from unfamiliar locations or devices. Monitor for changes to account recovery options.

Build incident response capabilities. Have a plan for what you do if someone is compromised. Who do you notify? What investigation do you conduct? How do you minimize damage?

Collaborate with other organizations. If you're in a high-risk field (journalism, activism, human rights, national security), you're not facing these threats alone. Share information about threat actors, phishing techniques, and best practices.

Regional Cybersecurity Context: The Middle East Cyber Landscape

Understanding this campaign requires understanding the broader cybersecurity landscape in the Middle East.

The region has become a hotbed for sophisticated cyber operations. Multiple nations conduct active cyber espionage, intellectual property theft, and political surveillance. Militant groups conduct cyber operations aligned with their political objectives. Criminal organizations conduct cybercrime operations.

Israel's Unit 8200 (military intelligence cyber operations) is known for sophisticated operations. Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) conducts extensive cyber operations. Saudi Arabia and the UAE both conduct sophisticated cyber campaigns. Turkey, Pakistan, and other regional players conduct cyber operations as well.

Beyond state actors, the region is home to sophisticated criminal organizations and activist groups who conduct their own cyber operations.

This creates a challenging environment for activists, journalists, and researchers. The threat landscape is complex. Attribution is difficult. The resources available to potential attackers are substantial.

For international organizations, journalists, and researchers working on Middle Eastern issues, accepting cyber risk as a reality of the work is important. This doesn't mean accepting compromise. It means understanding threats, implementing protections, and having plans for when protection fails.

The Evolution of Phishing: From Crude to Sophisticated

Phishing isn't new. It's been around since the early days of the internet. But this campaign shows how far phishing has evolved.

Early phishing was crude. Emails asking you to "verify your account" with generic requests and obvious grammatical errors. Most technically literate people could spot these immediately.

Modern phishing has evolved dramatically. It's more sophisticated in several ways:

Visual Authenticity: Modern phishing pages are clones of legitimate sites. The visual design, layout, colors, and interaction patterns are nearly identical to the real sites.

Personalization: Modern phishing campaigns often include personal details about the target, referencing specific projects or interests, making the messages seem more legitimate.

Delivery Precision: Modern phishing uses legitimate communication channels (WhatsApp, Signal, trusted platforms) rather than obviously phishing channels.

Technical Sophistication: Modern phishing pages capture metadata, request permissions for additional access, and integrate with larger attack infrastructure.

Multi-Stage Attacks: Modern phishing often doesn't accomplish the full attack in a single page. It might steal credentials in one stage, request permissions in a second stage, and establish persistence in a third stage.

Attribution Obfuscation: Modern attacks use legitimate services and relay infrastructure to make attribution difficult.

This evolution reflects the resources being invested in phishing. When state-sponsored actors, criminal organizations, and sophisticated hackers are all investing in phishing infrastructure, the techniques improve rapidly.

The Role of Researchers: Understanding Attacks Through Exposure

The fact that we know so much about this campaign is largely due to the actions of security researchers who analyzed the phishing pages and accessed the exposed data.

Security researchers play a crucial role in understanding cyber threats. They analyze malware, reverse engineer attack code, test vulnerabilities, and document attack techniques. In this case, researchers didn't just passively observe the campaign. They actively analyzed it, extracted data from the exposed servers, and shared findings with the public and with affected individuals.

This creates a tension. On one hand, researchers want to protect victims and attribute attackers. On the other hand, publicly reporting on attacks can tip off attackers and allow them to improve their techniques.

In this case, researchers handled the tension appropriately. They validated their findings. They coordinated with affected individuals. They worked with legitimate organizations to verify the campaign. They then published their findings in a way that provided information to at-risk individuals while avoiding specifics that would help attackers replicate the attack.

For the security community, this campaign will likely be studied for years. Future researchers will analyze it to understand attacker tactics, identify patterns, and develop better defenses.

Conclusion: Living in a World of Sophisticated Threats

The phishing campaign targeting Middle Eastern activists, journalists, and officials represents a new normal in cyber threats. Sophisticated, well-resourced attackers are targeting high-profile individuals with campaigns that combine social engineering, credential theft, account hijacking, and surveillance.

The barriers to entry for these attacks are lower than many realize. The resources required are substantial but not enormous. The technical expertise needed is significant but not exceptional. What's required is clear targets, specific objectives, and willingness to invest time and resources.

For at-risk individuals, the response isn't to become paralyzed by fear. It's to understand threats, implement protections, and have plans for when things go wrong. It's to recognize that digital security isn't about achieving perfect protection. It's about raising the cost of attacking you sufficiently that attackers choose easier targets.

For organizations, the response is to treat cyber security as a priority. Not because cyber attacks are theoretical future possibilities, but because they're happening now, targeting your staff, and the cost of compromise can be enormous.

For the cybersecurity industry, the response is to continue improving defenses, sharing threat intelligence, and developing better tools and practices.

For governments and international organizations, the response is more complex. It involves developing legal frameworks, attributing attacks to responsible parties, and enforcing consequences. It involves collaborating internationally because cyber threats don't respect borders. It involves protecting at-risk populations without limiting their ability to do their essential work.

The campaign documented in this article will likely fade from headlines. The attackers may or may not be identified or held accountable. Some victims will recover. Others may face lasting professional or personal consequences.

But the campaign itself is a warning. As our lives become increasingly digital, as activists and journalists rely on digital tools, as critical infrastructure becomes more connected, the sophistication of cyber threats will continue to increase. Understanding these threats, preparing for them, and responding appropriately when they occur is no longer optional. It's essential.

FAQ

What is a phishing campaign?

A phishing campaign is a coordinated effort to trick people into revealing sensitive information (like passwords, credit card numbers, or personal data) by impersonating legitimate organizations or trusted contacts. In this Middle East campaign, attackers sent WhatsApp messages containing malicious links that appeared to lead to Gmail or WhatsApp login pages but actually captured victims' credentials.

How does WhatsApp device linking work and why is it a security risk?

WhatsApp device linking allows a user to access WhatsApp on a web browser or desktop application by scanning a QR code displayed on the new device using their phone. This is a legitimate feature designed for convenience. However, in this campaign, attackers generated their own QR codes and tricked victims into scanning them by claiming the codes would verify accounts or grant access to meeting rooms. Once scanned, the attacker's device became linked to the victim's account, giving the attacker simultaneous access to all conversations.

What makes this phishing campaign different from typical phishing attacks?

This campaign was highly targeted and sophisticated. Unlike mass phishing that casts a wide net, this campaign specifically targeted high-profile individuals including government officials, journalists, activists, and researchers. It combined multiple attack vectors (credential theft, account hijacking, and browser-based surveillance), used obfuscated infrastructure (Duck DNS), and attempted to request permissions to access location data, photos, and audio from victims' devices.

How did security researchers discover the extent of the campaign?

Security researchers discovered that the attackers left their data server completely exposed on the internet without password protection. By modifying the URL of the phishing page, researchers could access a file containing logs of over 850 victim interactions. This exposed file revealed not just the scope of the campaign, but actual stolen credentials, two-factor authentication codes, and personal information about victims.

What should someone do if they suspect they've been targeted by a phishing campaign?

If you suspect compromise, immediately change the password for the compromised account from a secure device using a different network. Check account activity logs to see what the attacker accessed. Reset passwords for all other accounts that use the same or similar passwords. For WhatsApp, check for linked devices and unlink any unfamiliar ones. Monitor your accounts for suspicious activity. Consider enabling more robust two-factor authentication like hardware security keys. If you're a journalist or activist, consult with your organization's security team about potential implications of the compromise.

How can organizations protect high-risk staff from phishing attacks?

Organizations can implement hardware security keys (like YubiKey) for two-factor authentication, which cannot be captured by phishing pages. They should provide specific, realistic phishing training and run test campaigns to identify vulnerable staff. Implement account monitoring to detect suspicious access. Build incident response capabilities for when compromise occurs. Foster a culture where reporting suspicious messages is encouraged without fear of punishment. Finally, collaborate with other organizations in your field to share threat intelligence and best practices.

What is Duck DNS and why did attackers use it?

Duck DNS is a legitimate dynamic DNS provider that allows people to assign memorable domain names (like "somethinghere.duckdns.org") to servers with frequently changing IP addresses. It's used legitimately by system administrators for remote access. However, attackers abused it in this campaign because it obscures the actual server location, makes the phishing link appear more legitimate, and is less likely to be caught by security filters that might flag obviously malicious domains.

Is two-factor authentication via SMS as secure as app-based authentication?

No. SMS-based two-factor authentication is weaker than app-based or hardware-based authentication. SMS codes can be captured by phishing pages (as demonstrated in this campaign), intercepted through SIM swapping attacks, or obtained through compromised phone carriers. App-based authenticators like Google Authenticator or Authy are stronger because codes are generated locally on your device. Hardware security keys are the strongest option because they require physical interaction and cannot be fooled by phishing pages.

Key Takeaways

- A highly sophisticated phishing campaign targeted hundreds of high-profile individuals across the Middle East, including government officials, journalists, activists, and researchers

- The attack combined credential theft, account hijacking, and attempts at browser-based surveillance of location, photos, and audio data

- Attackers used WhatsApp as the delivery vector, Duck DNS for infrastructure obfuscation, and cloned Gmail and WhatsApp interfaces for deception

- The attackers left their data server exposed without password protection, revealing 850+ victim records including stolen credentials and two-factor authentication codes

- Attribution remains unclear, though the targeting pattern and sophistication suggest state-sponsored involvement, though criminal or hybrid operations cannot be ruled out

- The campaign highlights critical vulnerabilities in protecting at-risk individuals and the increasing sophistication of cyber threats targeting activism, journalism, and political opposition in the Middle East

Related Articles

- Internal Message Spoofing Phishing Campaign: How to Stop It [2025]

- Taiwan's 2.5M Daily Cyberattacks: China's Hybrid War Strategy [2025]

- LinkedIn Comment Phishing: How to Spot and Stop Malware Scams [2025]

- Jen Easterly Leads RSA Conference Into AI Security Era [2025]

- Fast Pair Bluetooth Vulnerability: Why 300M Devices Need Patching [2025]

- VoidLink: The Advanced Linux Malware Reshaping Cloud Security [2025]

![Massive Phishing Campaign Targets Middle East Officials, Activists, Journalists [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/massive-phishing-campaign-targets-middle-east-officials-acti/image-1-1768584999886.jpg)