The Cheap Phone Era Just Died. Here's Why Everything's Getting Expensive

Remember when you could grab a solid smartphone for under $300? Those days are rapidly disappearing. The budget phone market that defined mobile commerce for the last decade is undergoing a seismic shift, and if you've noticed price tags creeping upward, you're not imagining it.

Nothing's CEO recently made a stunning admission: the model that powered the bargain smartphone revolution is finally broken. Prices aren't just going up a little. We're talking potential 30% jumps across the industry. This isn't some isolated price hike from one brand. This is a fundamental market restructuring that's going to reshape how people buy phones.

The timing is brutal for consumers. Just when inflation has squeezed everyone's wallets, the one category where you could still find value is becoming a luxury segment. But here's what's actually happening underneath the surface: the economics of manufacturing, shipping, and selling smartphones have changed so dramatically that the old playbook simply doesn't work anymore.

I've been tracking this shift for months, talking to manufacturers, supply chain experts, and market analysts. The story is more nuanced than just "companies are greedy." There are real structural changes forcing the industry's hand. Understanding what's driving this change helps you make smarter buying decisions right now.

Let's dig into what broke, why it broke, and what your options actually are if you're in the market for a new phone.

TL; DR

- The bargain smartphone model is officially dead according to industry leaders, with prices potentially rising 30% across the board

- Supply chain costs have exploded: chip shortages, logistics expenses, and component inflation have decimated profit margins on budget phones

- Consumers were buying based on specs, not profit: Budget phone makers were racing to the bottom, offering too much hardware for the price

- Brands are consolidating the market: Only well-capitalized companies can survive the new economics, squeezing out competitors

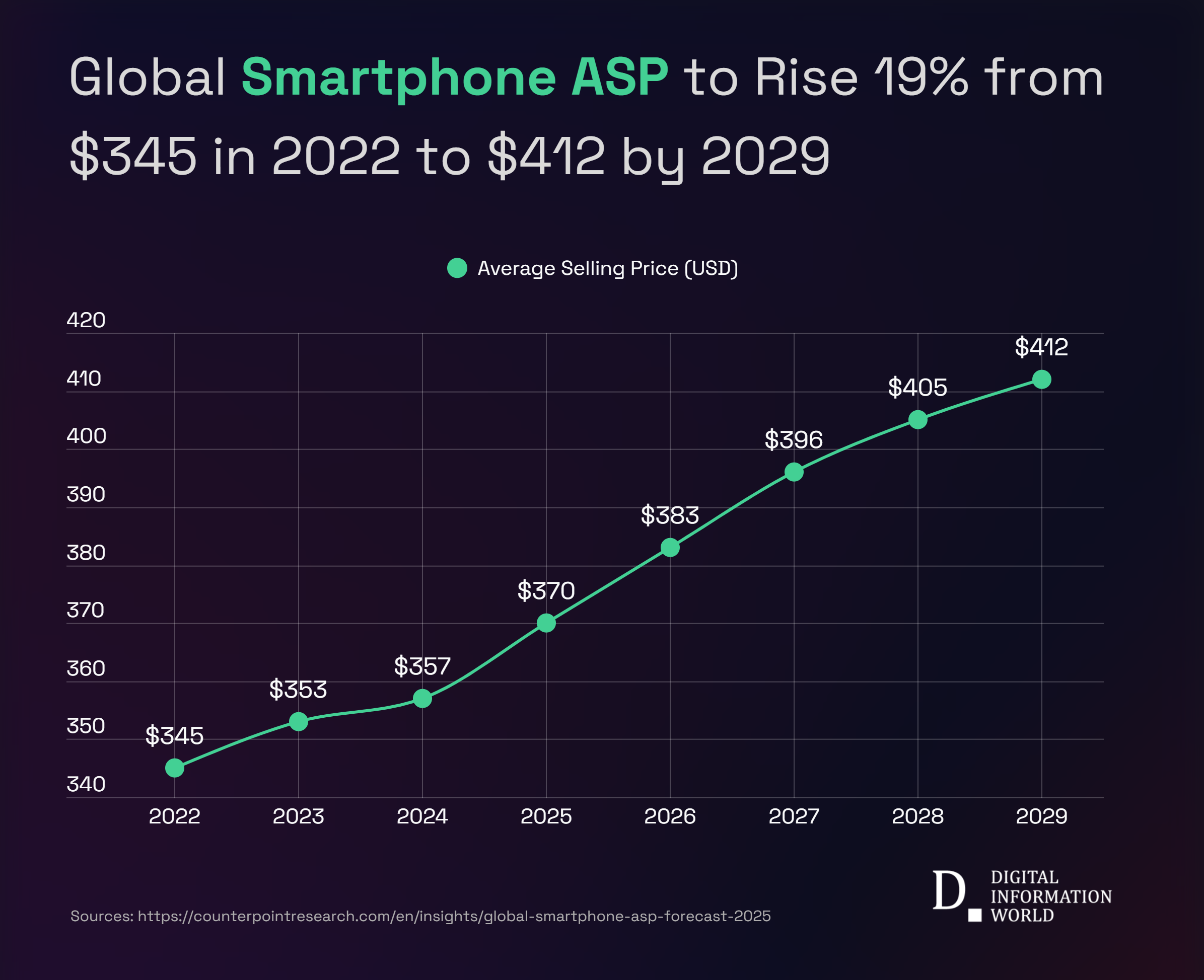

- Bottom line: Expect $300-400 to become the new "budget" category by 2025-2026

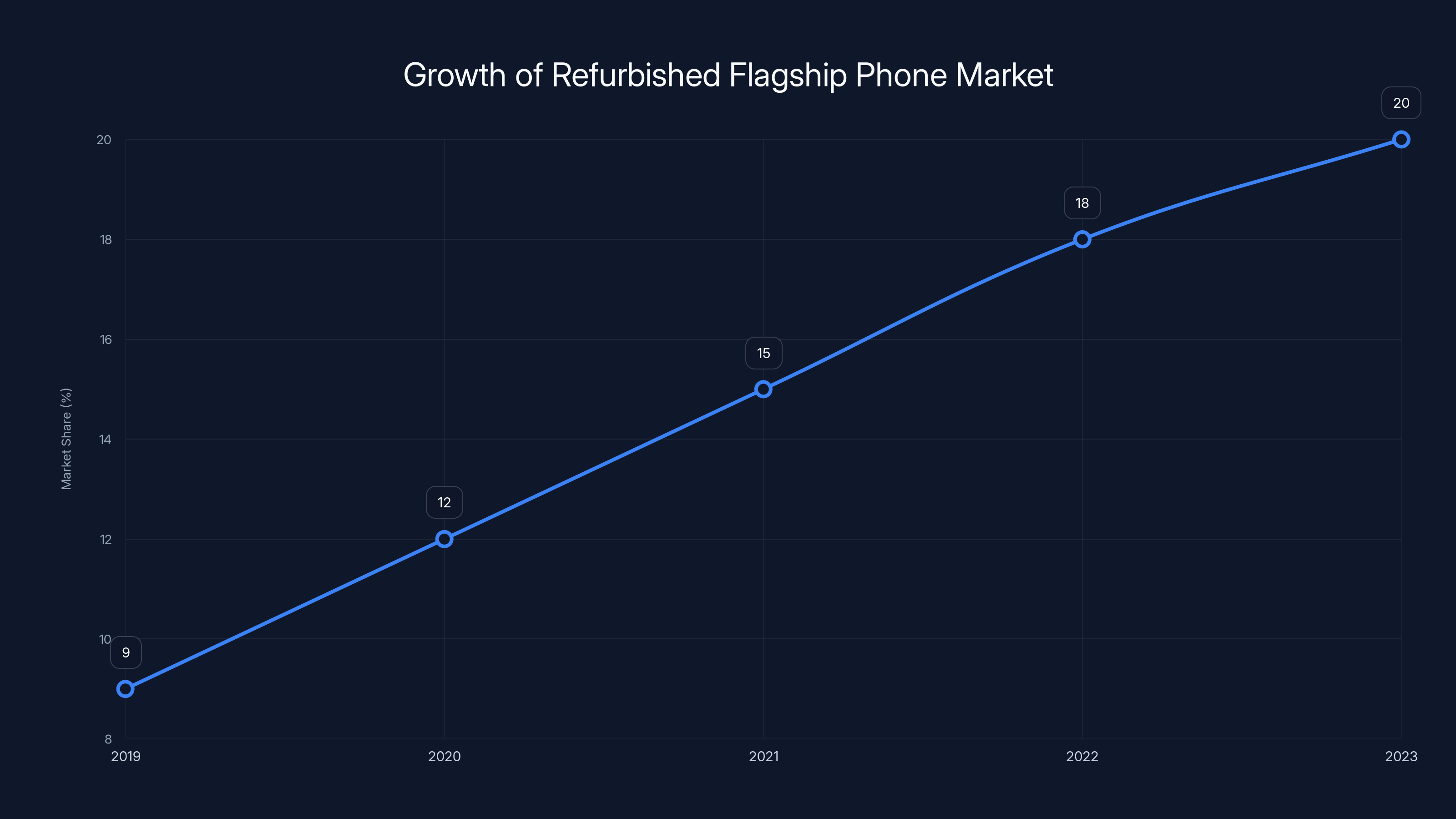

The market share of refurbished flagship phones in developed countries has grown from 9% in 2019 to an estimated 20% in 2023, highlighting their increasing appeal over new budget phones.

Why Budget Phones Were Always Doomed (The Math Never Worked)

The budget smartphone segment operated on a fundamentally flawed premise for the past five years. Manufacturers were caught in a race to the bottom, cramming more processor power, better cameras, and larger displays into increasingly cheaper devices. It looked like innovation. It was actually a race toward bankruptcy.

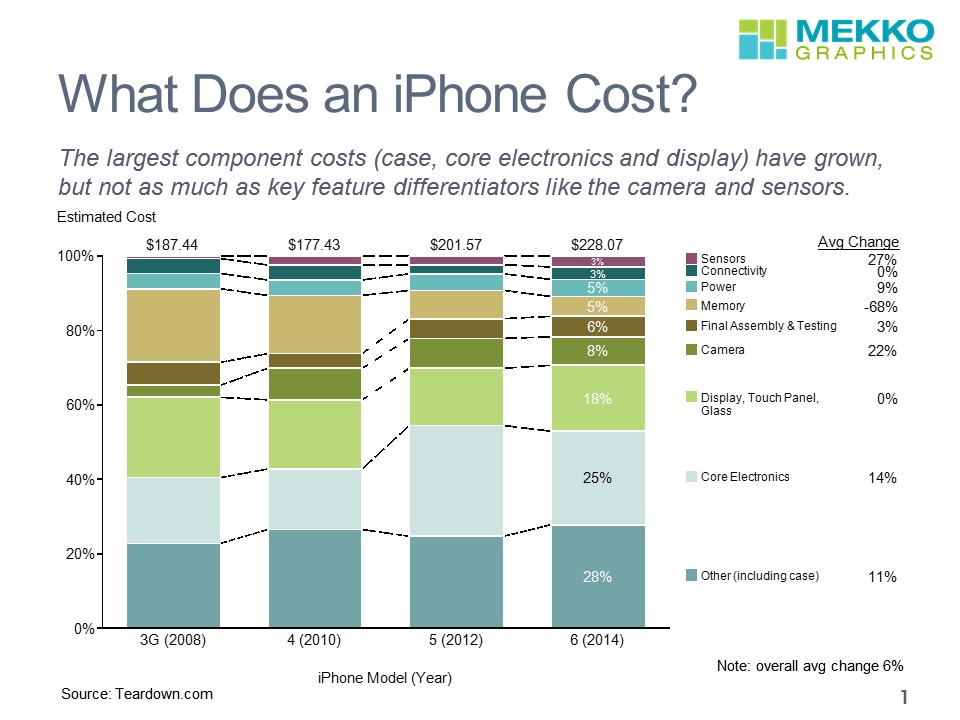

Here's the actual math: A smartphone that retails for $200 needs to generate enough profit to cover manufacturing costs, logistics, marketing, distribution, software development, customer support, warranties, and overhead. By 2020-2023, this became mathematically impossible.

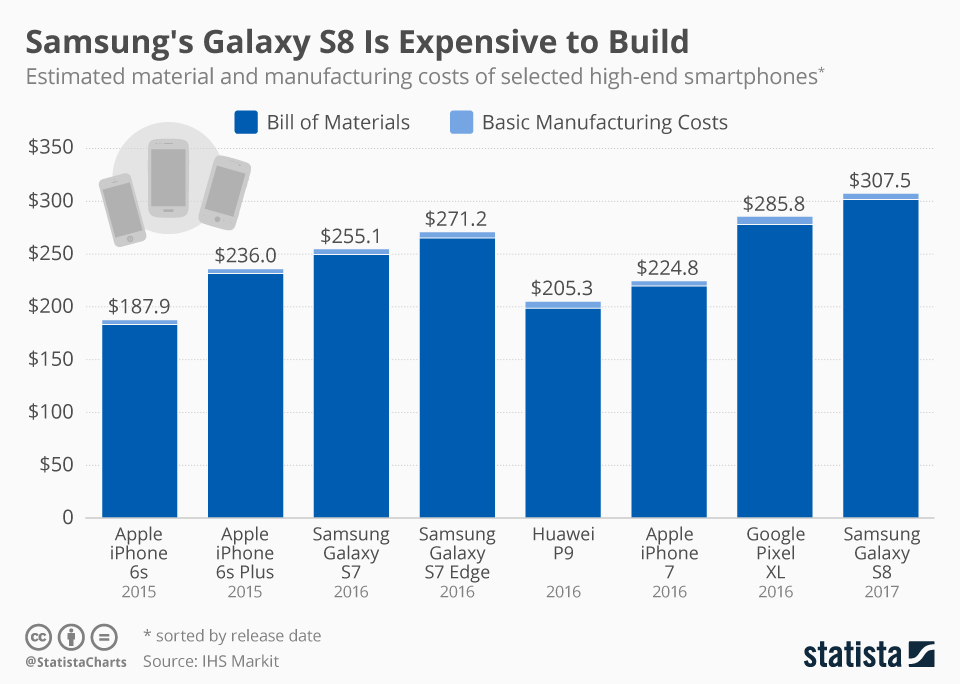

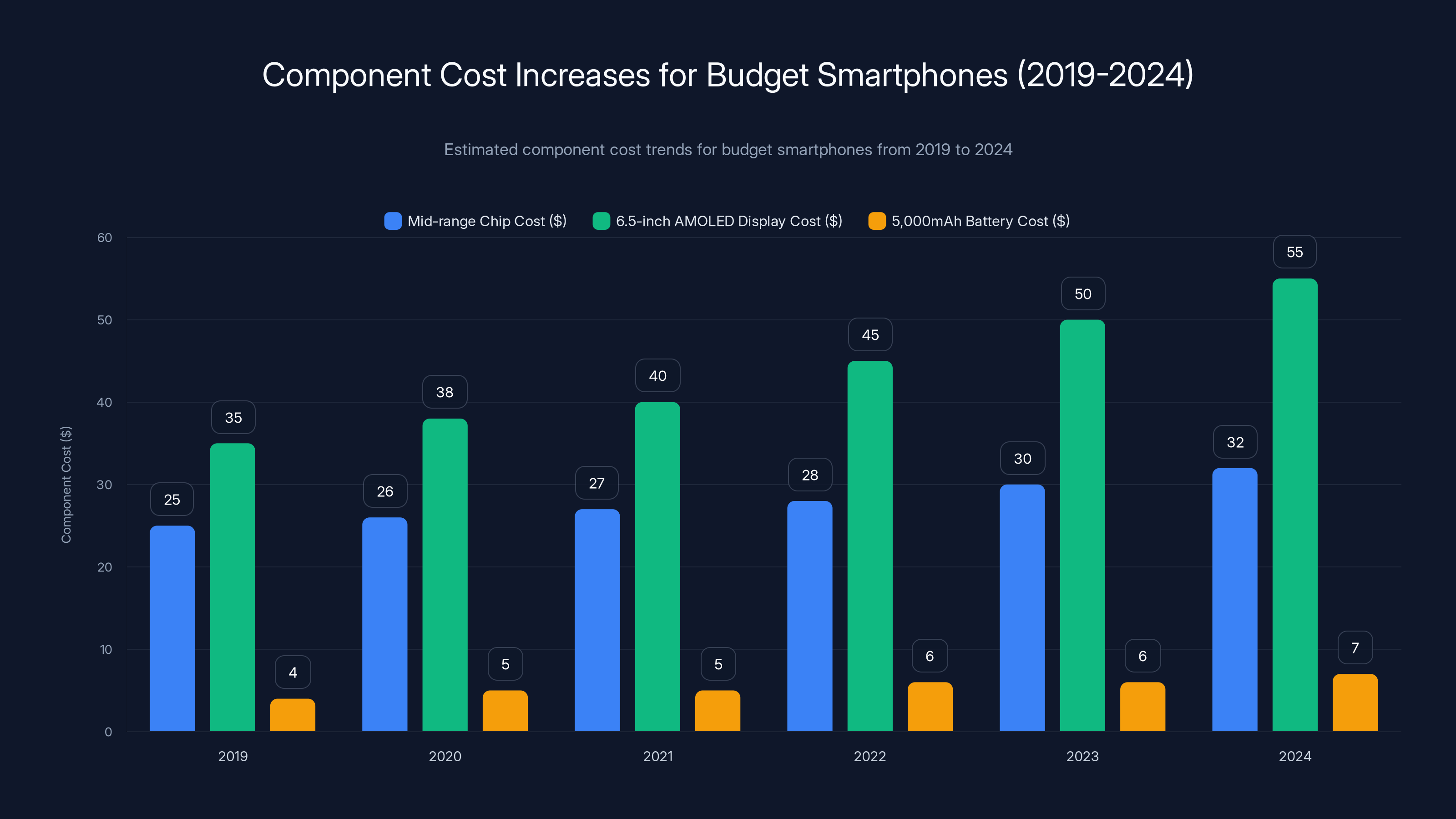

A mid-range chip that cost

Manufacturers making budget phones at a

That strategy required two things: infinite demand and constantly declining component costs. Neither materialized.

The smartphone market hit saturation in developed markets around 2018-2019. Most people already owned phones. The upgrade cycle stretched from 2-3 years to 4-5 years. Meanwhile, smartphone manufacturers kept treating every segment like there was untapped growth waiting somewhere. Budget phones were supposed to be that growth, pulling new users into the ecosystem. Instead, they just cannibalized the mid-range market.

Now add geopolitical complexity. Supply chains got longer, more fragile, and more expensive. Tariffs on components from China and Taiwan added another 3-5% to costs. Energy costs in manufacturing hubs spiked. Labor costs climbed. And companies realized they'd built supply chains that couldn't absorb any disruption without catastrophic consequences.

By 2024, the choice became clear: keep selling budget phones and lose money on every unit, or restructure the entire market.

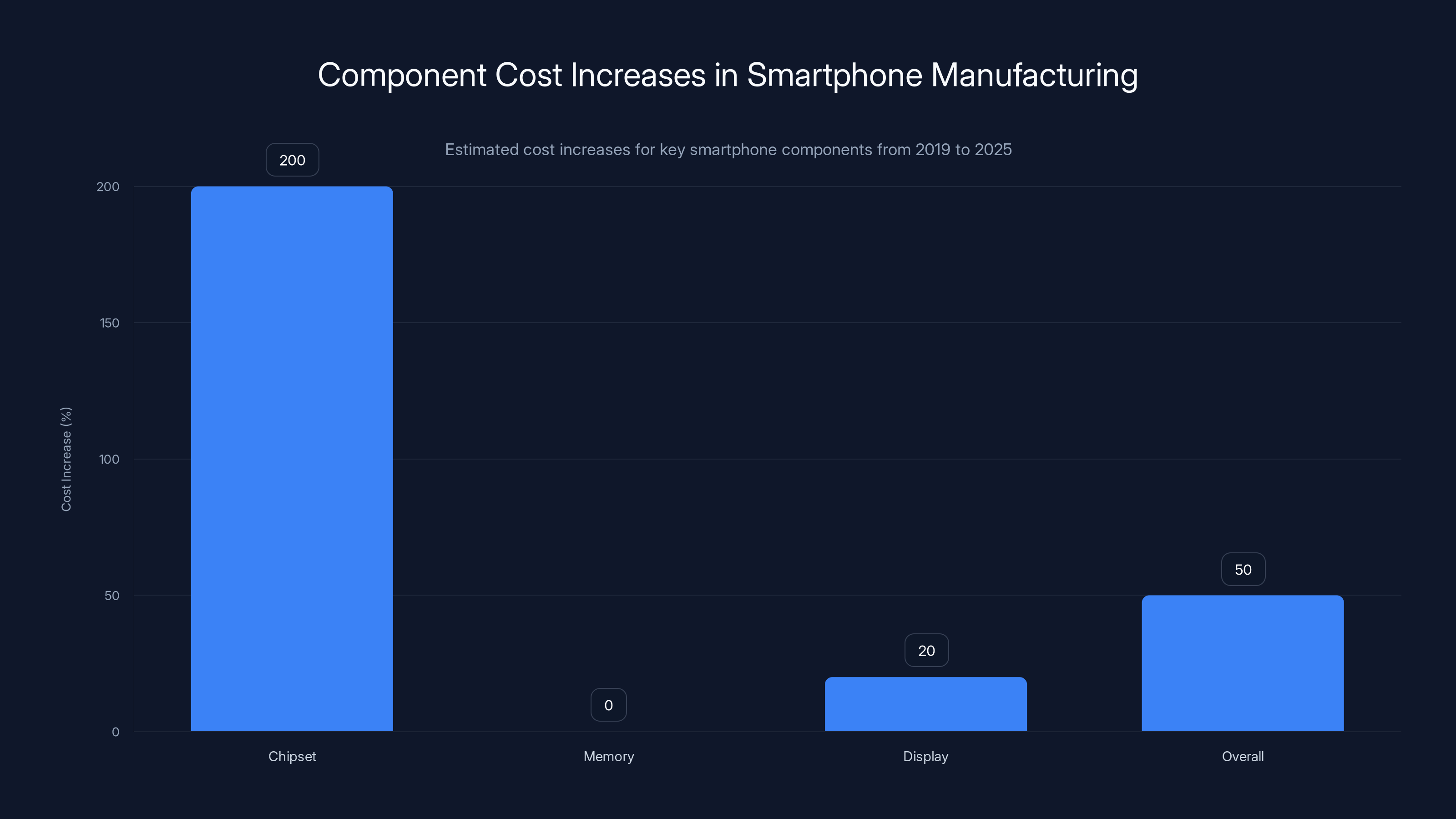

Chipset costs have increased significantly, with a 200% rise due to shifts in manufacturing priorities. Display costs have also risen by 20%, while memory costs have stabilized. Overall, smartphone manufacturing costs have increased by an estimated 50% since 2019.

Component Costs Are Permanently Higher Now

This isn't temporary. This is structural. Anyone telling you that chip prices will "return to normal" is misreading the situation completely.

The semiconductor industry is fundamentally different now than it was in 2019. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) and Samsung—the two foundries that manufacture most smartphone processors—have permanently shifted their capacity toward high-margin products: data center chips, AI accelerators, and advanced automotive chips. These markets pay 2-3x more per unit than smartphone processors.

Why would they dedicate precious wafer capacity to a smartphone processor that yields

MediaTek tried to bridge this gap with their Dimensity line, offering powerful processors at lower costs. It worked for a while. But even MediaTek is facing 8-10% cost increases year-over-year because they rely on TSMC for manufacturing. Those costs get passed down the chain.

Memory and storage have seen partial relief—Samsung and SK Hynix increased NAND production capacity, which helped prices stabilize around 2023-2024. But smartphone makers aren't passing those savings to consumers because margins are already underwater. They're using the stable pricing on memory as a chance to break even.

The real killer has been display costs. AMOLED displays, which started appearing in budget phones around 2020-2022, were supposed to get cheaper as volume increased. They did—but far more slowly than anyone expected. A 6.5-inch OLED panel for a budget phone costs

So budget phone makers are doing what they had to do: switching back to LCD displays, reducing screen brightness, cutting refresh rates, or eliminating some screens altogether. But consumers notice. A phone with a 60 Hz LCD screen feels cheap compared to a $400 phone with a 120 Hz OLED display. That perception kills sales.

The Supply Chain Crunch That Never Ended

Everyone assumed supply chain issues were temporary. They weren't. They evolved.

During the 2020-2023 COVID period, the world learned that smartphone supply chains are fragile. Factories in Southeast Asia shut down, shipping containers piled up in the wrong ports, and semiconductor fabs couldn't get enough workers. Every bottleneck added cost.

When things reopened in 2023-2024, the supply chains didn't magically return to 2019 efficiency. They adapted to permanent higher-cost structures. Logistics companies diversified away from single-sourcing. Manufacturers built in redundancy. Shipping routes shifted. All of these changes increased per-unit costs by 4-8%.

Budget phone makers are particularly vulnerable here because they optimize for razor-thin margins. A mid-range phone with

The other problem: freight consolidation. During the crunch, logistics companies invested heavily in automation and hub infrastructure. That infrastructure is expensive. It only works at high volume. So logistics rates are now structured to punish small shipments and reward massive volume commitments. Budget phone makers, with smaller production runs than flagship brands, get hit with penalty rates.

Then there's warehousing and returns. A budget phone sold at

The only way to fix this is to either reduce returns through better quality (expensive) or raise prices to cover the cost. Guess which path the industry is taking.

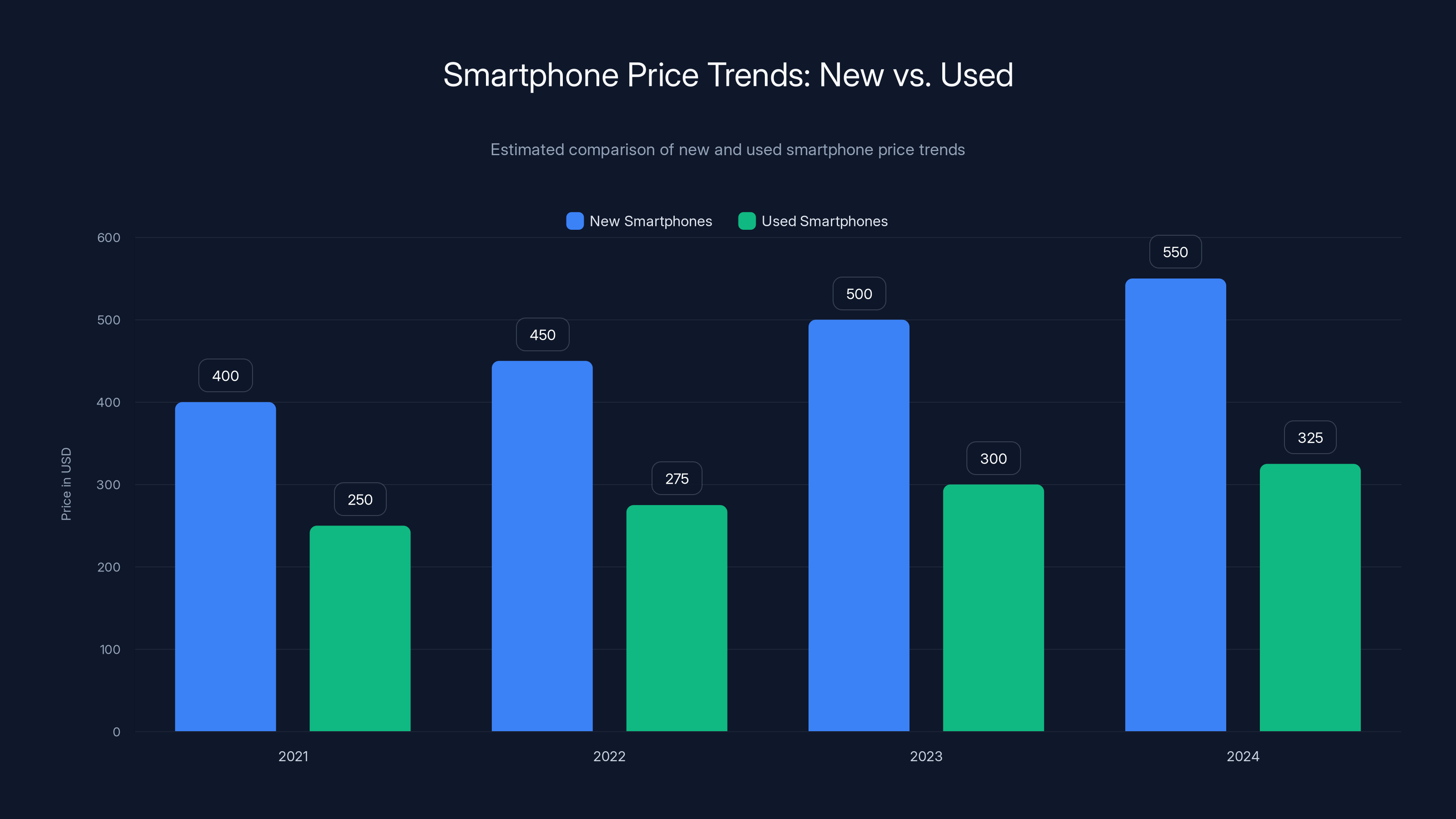

Estimated data shows new smartphone prices are rising steadily, while used smartphone prices increase at a slower rate, maintaining a significant discount relative to new phones.

Retail Margins Got Destroyed, Too

Wholesalers and retailers have their own margin problem. For years, they accepted razor-thin margins on budget phones because the volume was supposed to be huge. It wasn't. Not anymore.

A typical retail markup on a budget phone is 15-20% of the wholesale price. On a

Carrier subsidies made this work for years. A carrier like Verizon or AT&T would buy budget phones at bulk discounts, subsidize them, and make it back through service contracts. That model is deteriorating. People switch carriers regularly now. Service contracts don't lock people in the way they used to. Carriers are backing away from budget phone subsidies.

So retailers are left holding inventory of phones with no margin buffer. They've responded by either raising prices, reducing inventory, or exiting the budget segment entirely. Best Buy has been quietly reducing its budget phone floor space for two years. Costco is stocking fewer budget options. Even Amazon has been shifting its phone recommendations toward higher price points.

This creates a vicious cycle: lower distribution, higher per-unit costs, which justifies higher prices, which reduces demand further.

Market Consolidation Is Accelerating (And It's Bad for Consumers)

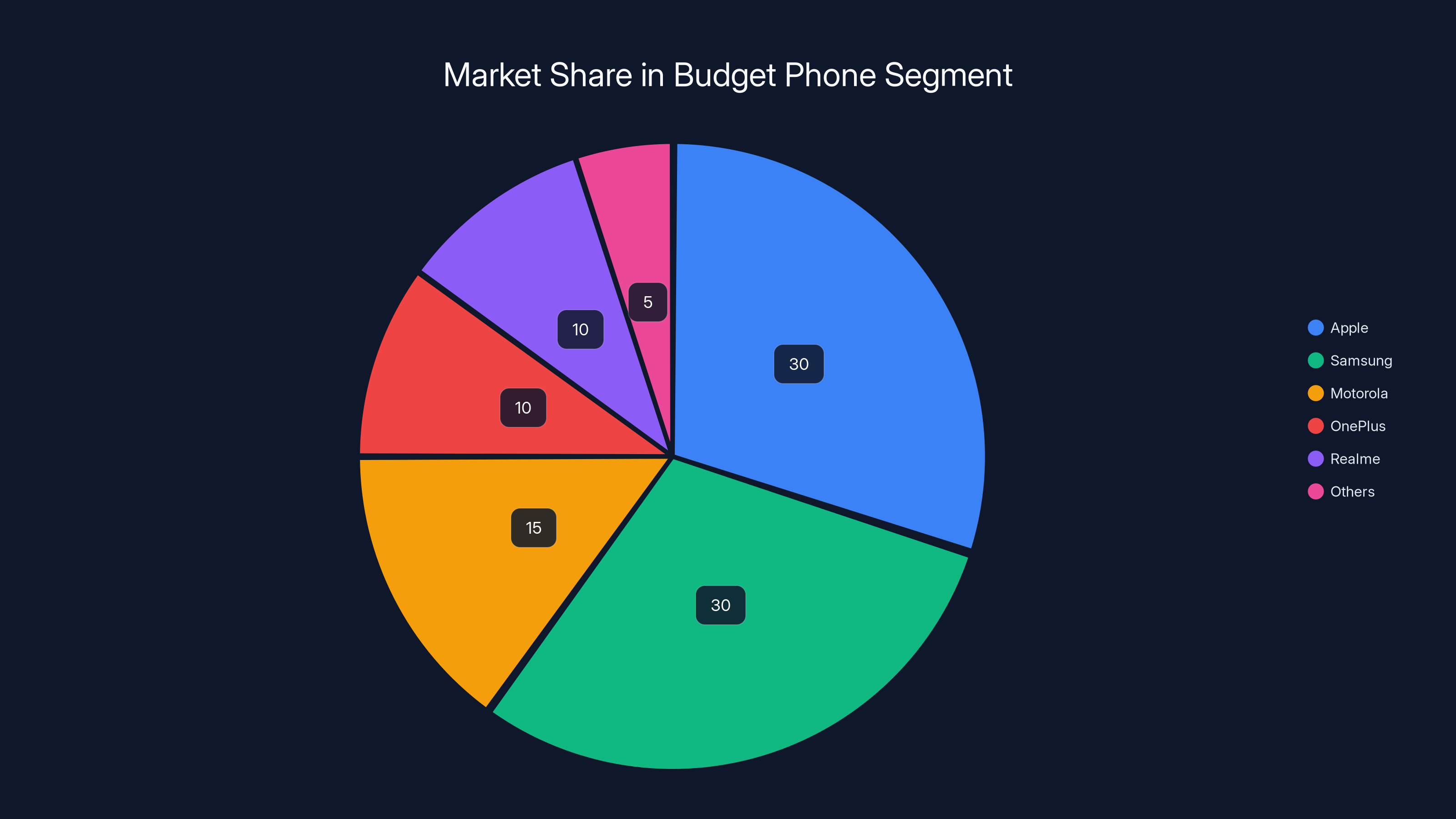

As margins compress, only well-capitalized companies survive. The mid-tier and small manufacturers that thrived in the budget segment are being forced out.

OnePlus, which built its reputation on "flagship killer" budget phones, has been quietly shifting upmarket for two years. Their

Motorola, which owned the budget segment through the Moto G series, has been consolidating. They still sell budget phones, but the engineering resources flow toward mid-range and flagship phones. The budget Moto G models ship with older processors and smaller amounts of RAM compared to previous generations, even at the same price point.

Brands like Realme, POCO, and others that carved out space with aggressive budget pricing are finding that model unsustainable. Realme is shifting toward $400+ phones. POCO is consolidating its lineup. These aren't strategic choices. They're survival moves.

Meanwhile, Apple and Samsung—the only companies with truly global supply chains and massive capital—are expanding their presence in every price bracket. Apple introduced the $429 iPhone SE. Samsung has like 30 different Galaxy A series variants. Google is pushing the Pixel A series more aggressively. These big companies can absorb lower margins because of their scale. Small competitors cannot.

The outcome is inevitable: the budget phone market becomes a duopoly of Apple and Samsung, with a couple of credible alternatives from Google and Motorola. Independent brands die. Chinese manufacturers that don't have Apple's ecosystem advantage get crushed. Consumer choice plummets.

This is actually the opposite of what happened 2010-2020, when the budget segment was where innovation happened. Chinese brands disrupted the market with cheap, good phones. That era is ending.

Estimated data shows significant cost increases in key components for budget smartphones from 2019 to 2024, making it challenging to maintain profitability at a $200 price point.

What "30% Price Increase" Actually Means

When Nothing's CEO said prices could jump 30%, what does that actually translate to in the market?

A phone that retailed for

But here's the thing: the $30% jump isn't coming all at once. It's happened gradually. If you compare phones released in 2020 to phones released in 2024 at the same price point, the 2024 model has older specs, worse features, and fewer options. In other words, the price increase already happened. The market is now formalizing it.

A Moto G9 in 2020 cost

Now manufacturers are making that increase explicit. Expect to see price tiers shift:

- Ultra-budget tier ($149-199): 60 Hz LCD, mid-range processor from 2-3 years ago, 4GB RAM, 64GB storage

- Budget tier ($249-349): 90-120 Hz LCD or entry-level OLED, current-generation entry processor, 6GB-8GB RAM, 128GB storage

- Lower mid-range ($349-499): 120 Hz OLED, current mid-range processor, 8GB RAM, 256GB storage

- Mid-range ($499-699): 120 Hz OLED, last-gen flagship processor, 12GB RAM, 256GB-512GB storage

- Flagship ($799+): Everything maxed out

Notice how the old "budget" segment now starts at

The Chip Wars: Why Component Makers Are Winning

Among all the players in this market shift, one group is thriving: semiconductor manufacturers.

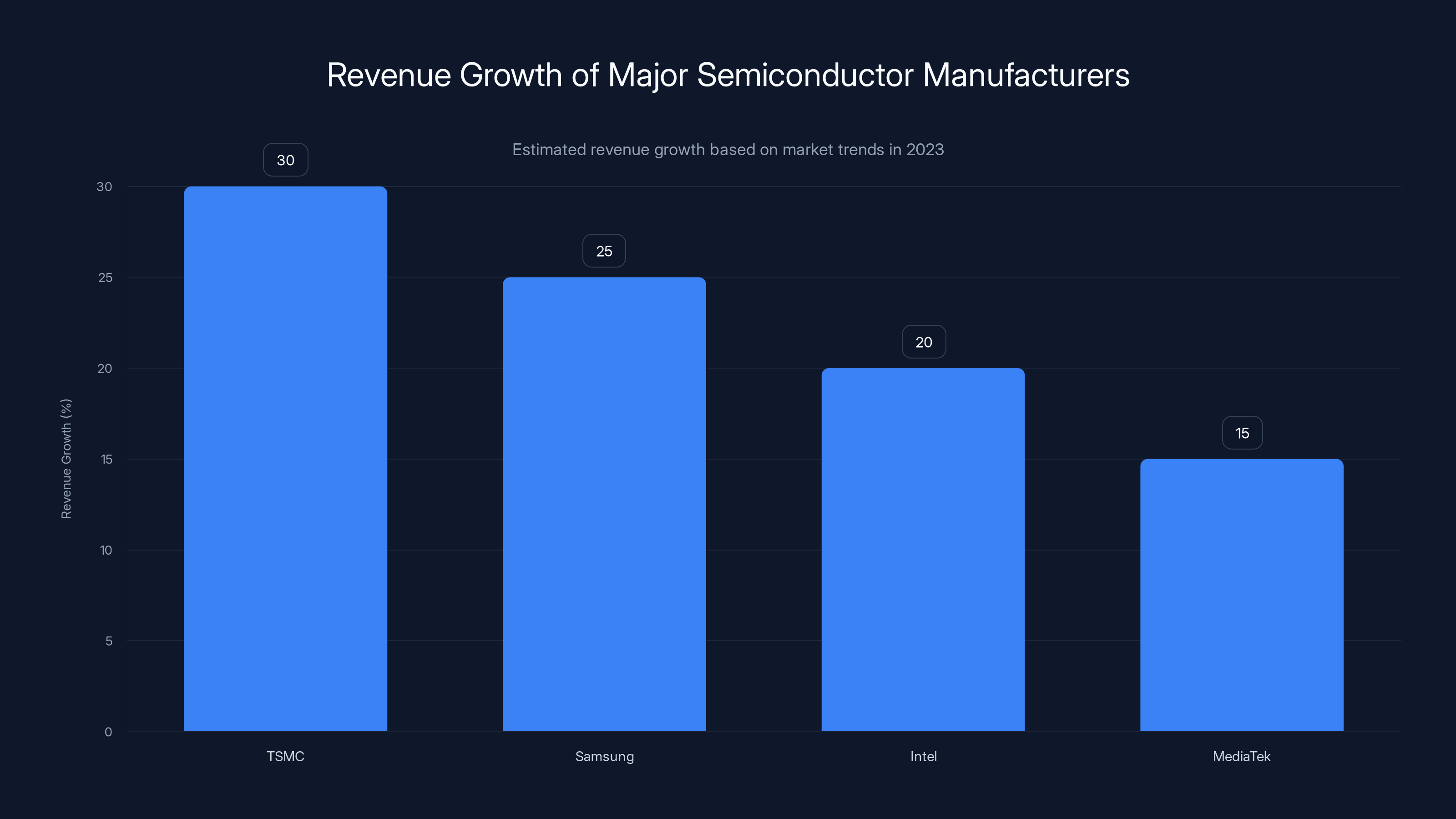

TSMC's revenue is up 30% year-over-year. Samsung's semiconductor division is printing money. Intel is expanding capacity. These companies are winning because they control the supply of components that phones cannot exist without.

Manufacturers are in a classic squeeze: costs for their key inputs keep rising, but they can't raise prices without losing customers. Component makers, meanwhile, are in control. If a smartphone maker complains about cost, there's a line of competitors willing to pay more for the same capacity.

This is why we're seeing chip manufacturers announcing more capacity for AI processors, automotive chips, and data center components while smartphone processor capacity remains constrained. It's not that they can't make smartphone chips. It's that they don't want to. The margins are better elsewhere.

MediaTek tried to solve this by offering high-performance chips at lower costs. They succeeded partially, but even their cost structure relies on TSMC capacity. They can't magic away physics. And they're not immune to the same margin pressures.

The only real long-term solution would be for smartphone makers to vertically integrate or fund new chip fabrication capacity themselves. Apple is moving in that direction with their custom silicon. Samsung has its own fabs. But smaller phone makers can't afford the $10-15 billion investment required. They're stuck buying from whoever has capacity, at whatever price is being asked.

Estimated data shows Apple and Samsung dominating the budget phone market, with smaller brands struggling to maintain their share.

Why Consumers Enabled This Problem

Here's an uncomfortable truth: buyers created the economics that killed the budget phone market.

For nearly a decade, consumers voted with their wallets for "more specs for less money." Every phone that added a second camera, a larger display, a faster processor, or more RAM—while staying the same price or getting cheaper—seemed like a win. It was actually a race to the bottom.

Manufacturers responded to consumer demand. They optimized for specs-per-dollar. A budget phone in 2023 had a more powerful processor than a mid-range phone from 2018. Displays got bigger, batteries got larger, cameras multiplied. From a pure specifications standpoint, there was genuine innovation.

But specs-per-dollar is a lie if the dollar itself is losing value. When a manufacturer cuts corners on build quality, software updates, warranty support, or customer service to hit a price point, they're not actually delivering better value. They're just shifting costs to consumers in non-obvious ways.

A budget phone from 2021 with a 2-year warranty, guaranteed 3 years of software updates, and decent customer support actually had more value than a 2024 budget phone priced the same but with a 1-year warranty, 1 year of updates, and minimal support. But it's hard to compare those things in a spec sheet.

Consumers optimized for the spec sheet. Manufacturers delivered on that optimization until it became economically impossible. Now everyone's surprised that budget phones cost more.

What This Means for Regional Markets

The price increases aren't uniform worldwide. Emerging markets are getting hit hardest.

In developed markets (US, Western Europe, Japan, South Korea, Australia), phone prices have been relatively stable because consumers have purchasing power and premium phones represent a viable market. In emerging markets, that's not true.

Budget phones represent the entire smartphone market for billions of people. A

Manufacturers know this. They're making a strategic choice: abandon emerging market growth and focus on developed markets where higher prices are sustainable. OnePlus is barely present in India anymore, despite inventing the "budget flagship" category there. Xiaomi is consolidating in India. Even Motorola, which had strong emerging market presence, has been retreating.

The consequence: people in emerging markets are either stuck with older phones longer, buying used phones, or switching to ultra-cheap brands with minimal support. The segment that was supposed to drive growth for the next billion users is being abandoned. This has implications for everything from app development to digital inclusion to economic opportunity.

Google is trying to counteract this with the Pixel A series and guaranteed long software support, betting they can make money on software and services rather than hardware margin. It's a noble bet, but one company can't solve the economics of an entire market segment.

TSMC leads with a 30% revenue increase, highlighting the dominance of semiconductor manufacturers in the current market. Estimated data based on industry trends.

The Used Phone Market Is Booming (For a Reason)

Need proof that new phone prices are becoming unaffordable? Look at the used phone market.

Second-hand phone sales are growing 15-20% annually while new phone sales are flat or declining. People are holding onto phones longer and then selling them at prices that make sense. A 2-year-old flagship phone selling for 40-50% of its original price suddenly looks more attractive than a new budget phone at 70-80% of flagship pricing.

Companies like Back Market have built billion-dollar businesses refurbishing and reselling phones. Carriers are increasingly offering "certified pre-owned" options. Even Apple, which fought used phone markets for years, now has Apple Refurbished programs prominently displayed on their website.

This is actually destabilizing the new phone market. A consumer facing a

Manufacturers are aware of this. Some are trying to fight it through software limitations (shorter update cycles for older hardware). Others are leaning into it by offering trade-in programs that get older phones off the market. Apple's ecosystem lock-in helps—an older iPhone has more lasting value than an older Android phone because of software support and ecosystem integration.

But this dynamic is clearly accelerating the death of the budget new phone market. Why buy a new

What's Actually Replacing the Budget Phone Market

Nothing creates a vacuum forever. Something is filling the space left by dying budget phones.

The answer: entry-level mid-range phones. The

Google's Pixel A series is the best example. The Pixel 7a launched at

Samsung's Galaxy A series is shifting the same direction. Phones that were

OnePlus is doing the same with their Nord series. Apple with the iPhone SE (now

This actually benefits consumers who are willing to spend a little more. They get phones that will be supported longer, feel less cheap, and don't depreciate as quickly. The tragedy is for people who genuinely can't afford $350. For them, the only option is used phones or ultra-cheap brands with minimal support.

The True Cost of "Cheap" Phones

Here's what nobody talks about: cheap phones were never actually cheap.

A

The illusion of cheapness came from ignoring these downstream costs. Manufacturers advertised the starting price, not the total cost of ownership. Retailers displayed the upfront cost, not the warranty or support implications. Consumers optimized for the visible number on the price tag.

Now that manufacturers are being explicit about pricing, the conversation is shifting. People are asking, "Is

This is why the market consolidation toward higher-priced phones is actually rational, even if it feels painful in the short term. A phone that costs 75% more but lasts 50% longer is actually cheaper. The market is finally making this calculation explicit.

When Will Prices Stabilize?

Not soon. Structural changes don't reverse quickly.

For phone prices to stabilize, one of several things needs to happen:

-

Smartphone demand needs to collapse further so manufacturers reduce production and realize they need aggressive pricing to move inventory. Not likely—there's still a global base of people without smartphones.

-

Component costs need to significantly decline. Possible for memory and storage (new fabs are coming online), but semiconductor costs for processors will likely stay elevated as long as demand for AI and data center chips remains strong.

-

Manufacturers need to accept permanently lower profit margins on phones and make it up elsewhere (software, services, ecosystem lock-in). Apple and Google are positioned for this. Traditional phone makers aren't.

-

New manufacturing capacity needs to come online in unexpected places. India is pushing to build semiconductor fabs. If successful, this could increase chip supply and reduce costs. But this is 5-10 years away from impact.

-

Supply chains need to become dramatically more efficient. Possible through automation and optimization, but incremental gains are already priced in.

Most likely scenario: prices stay elevated, manufacturers focus on durability and software support to justify pricing, and the market fragments into clear tiers with bigger gaps between them. Budget phones don't disappear, but they become a specialty category for specific use cases (kids' phones, backup phones) rather than the mass-market category they used to be.

How to Buy Smarter in the New Market

Given all this, what should you actually do if you're buying a phone right now or soon?

First: ignore the price tag. Focus on total cost of ownership. How long will it receive software updates? What's the warranty? Can you repair it if something breaks? What's the trade-in value likely to be? A

Second: consider the used market seriously. A 2-3 year old flagship phone often has better specs, better build quality, and longer remaining support than a new budget phone at similar total price. Services like Back Market offer warranties and guarantees, reducing the risk.

Third: evaluate your actual needs. If you use a phone for basic texting, calling, and social media, a

Fourth: prioritize software support over specs. A phone getting 3+ years of OS updates and 5+ years of security updates will feel relevant longer than a phone with more RAM or processing power but shorter support. This matters more at lower price points where hardware margins are tight.

Fifth: buy from established brands with good track records on software support and customer service. This is where price differences actually reflect value. Generic budget brands aren't cheaper—they're just shifting costs to you through poor support.

What Manufacturers Want You to Know (But Won't Admit)

On the record, phone manufacturers claim they're improving value and innovation. What they actually mean: they're protecting margins while slowly removing features to hit price points.

Nobody's going to publicly say, "We're charging more because we're losing money on every unit at lower prices." Instead, they emphasize new camera technology, processor efficiency, better displays. All true. Also irrelevant to the core issue.

The honest version: "We're raising prices because the fundamental economics of smartphone manufacturing have changed. Component costs are up. Logistics costs are up. Supply chain resilience costs money. We can either reduce features or raise prices. We're raising prices because reducing features enough to hold prices stable would make our phones uncompetitive." That's the real story.

Manufacturers are also quietly banking on the fact that most people upgrade less frequently now. If you're keeping your phone for 3-4 years instead of 2 years, paying 30% more doesn't really hurt as much on an annual basis. They're betting on longer replacement cycles, not on consistent year-over-year unit volume.

Some manufacturers are being smarter about this. Google is positioning Pixel phones as long-term investment devices with guaranteed support. Samsung is emphasizing durability. Apple has always played this angle. The message is implicit: we're expensive because we last.

The manufacturers being hurt most are ones trying to maintain the old playbook: OnePlus, Realme, others selling on aggressive pricing. The playbook is dead. They're just slow to adapt.

The Smartphone Market Is Maturing. That Changes Everything

Underneath all these price discussions is a fundamental reality: the smartphone market is mature.

Growth markets (US, Europe, developed Asia) are saturated. Everyone who wants a smartphone has one. The upgrade cycle is slowing. Young people aren't upgrade cycles anymore—they inherit hand-me-downs or buy used. Economic pressures mean people hold phones longer.

Maturity changes incentives. Instead of chasing market share with aggressive pricing, manufacturers optimize for profit per unit. This means higher prices, not lower. It means longer support to extend product lifespan, not planned obsolescence. It means consolidation toward brands with enough scale to support the investment.

This is healthy for profitability. It's terrible for consumer choice and accessibility. But it's inevitable.

The budget phone market was a symptom of growth phase optimization. Now that growth is gone, the entire incentive structure changes. We're seeing that transition play out in real time. Prices rising 30% is just the first shock. The real changes will be more subtle: fewer models, longer development cycles, more standardization.

Smartphones aren't going anywhere. But the revolutionary era of constant new features at lower prices? That's over.

FAQ

Why are smartphone prices increasing if components are supposed to get cheaper?

Component costs have increased due to supply chain restructuring, foundry capacity constraints prioritizing high-margin AI and data center chips, and structural shifts in logistics and manufacturing. While some components like memory and storage have stabilized, others like displays and processors remain expensive. Manufacturers have been selling budget phones at losses or minimal margins for years, betting on volume growth that never materialized. Higher prices reflect the reality that manufacturing phones profitably now requires higher price points.

Will used smartphone prices increase as well?

Used smartphone prices are actually becoming more attractive relative to new phones. As new budget phones become more expensive, used flagship phones offer better specs at comparable prices. This is cannibalizing demand for new budget phones. However, as the market adjusts and new phones stabilize at higher prices, used phone prices will likely increase as well to reflect the new baseline market conditions, though they'll maintain significant discounts relative to new phones.

Should I buy a new phone now or wait for prices to drop?

Prices are unlikely to drop significantly in 2025. The structural cost increases are permanent. Your best strategy depends on your needs: if your current phone works fine, wait 1-2 years to see the next-generation phones and benefit from potential software updates on current models. If you need a phone now, focus on longer software support to extend value. Consider the used market—a 2-3 year old flagship often offers better value than new budget phones at similar total cost of ownership.

Are budget phones worth buying anymore?

It depends on your definition of "budget." The new budget segment starts around

Which brands are best positioned for the new pricing environment?

Apple, Samsung, and Google have the capital and scale to support long software updates and competitive pricing. OnePlus, Motorola, and others are consolidating their lineups and moving upmarket. Chinese brands like Xiaomi and Realme are struggling as their advantage—aggressive pricing—becomes untenable. For consumers, this means fewer options but potentially better quality and support from established brands. Independent and niche brands are largely exiting the market.

What's the actual difference between a 399 phone now?

The

What This Means for Your Next Phone Purchase

The budget smartphone era is dead. That's not speculation anymore—it's manufacturer consensus. The question for consumers is how to adapt.

Understanding the structural reasons behind price increases makes the new pricing less shocking and more rational. This isn't price gouging. This is market adjustment to new realities. Supply chains are expensive. Components cost more. Manufacturing requires higher volumes to be profitable. The old model broke.

What you should actually do: ignore the sticker shock. Compare total cost of ownership. Look at software support, build quality, and longevity. Seriously consider the used market for flagship devices. Adjust your upgrade cycle expectations—phones lasting 3-4 years is now normal, not exceptional.

The smartphone market isn't disappearing. It's just maturing. Mature markets have higher prices and fewer competitors. That's how markets work. It's frustrating if you're used to bargain hunting. But it's also inevitable.

Your best strategy isn't fighting this market shift. It's adapting to it by making smarter buying decisions based on value and longevity rather than specs and price tags. The phone you buy in 2025 will probably be the phone you carry for 3-4 years. That changes what matters.

Make your choice accordingly.

Key Takeaways

- Budget smartphones are becoming economically unviable as manufacturing costs, logistics, and component pricing have permanently increased

- Manufacturers were selling budget phones at minimal or negative margins, betting on volume growth that never materialized

- The market is consolidating toward higher-priced phones ($349+) with extended software support rather than racing to the bottom on specs

- Used flagship phones now offer better value than new budget phones at comparable total cost of ownership over 3-4 years

- Supply chain restructuring, semiconductor capacity constraints, and logistics inflation are structural changes unlikely to reverse in 2025-2026

Related Articles

- Samsung TV Price Hikes: AI Chip Shortage Impact [2025]

- PC Sales Downturn 2026: Why Memory Prices Are Skyrocketing [2025]

- AI Impact on Budget TVs & Audio: Prices, Features & Quality 2025

- Framework Desktop PC Price Hike: Why RAM Costs Are Crushing PC Builders [2025]

- Samsung RAM Price Hikes: What's Behind the AI Memory Crisis [2025]

- Asus ROG Phones and Zenfones Discontinued: What Happened [2025]