The Equity Problem That's Been Hiding in Plain Sight

Imagine building something you believe in for months, maybe years. You've got traction, real customers, proof that your idea works. Then you walk into a meeting with one of the world's most prestigious accelerators and they want 7% of your company. Just for the privilege of access.

That's the accelerator model that's dominated Silicon Valley for the past fifteen years. And it works spectacularly well for the accelerators. But for the founders? There's been a growing tension between wanting the prestige, mentorship, and network that top programs offer, and knowing that handing over that much equity this early can reshape your entire financial future.

Ali Partovi, a veteran investor with an almost eerie track record for spotting eventual unicorns, thinks this tension is unnecessary. His firm, Neo, just launched Neo Residency, a new accelerator program designed to blow up the traditional equity-for-mentorship trade-off. And the terms he's offering are genuinely unusual in ways that are worth understanding, whether you're a founder, an investor, or just someone curious about how startup economics are changing.

The program invests

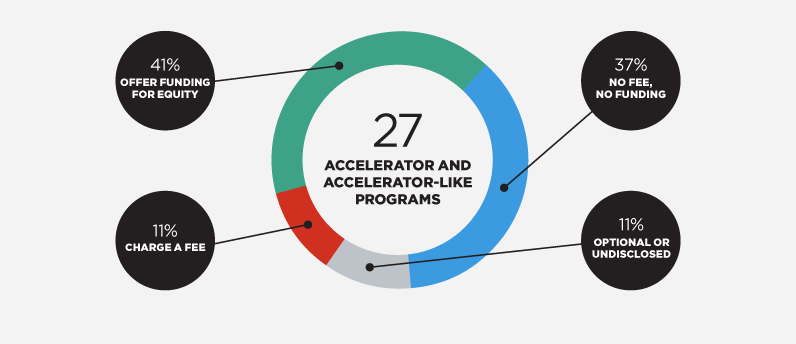

To understand why this matters, you need to understand what's actually changed in the startup world, why traditional accelerator economics have started to feel dated to a certain class of founder, and what Partovi's track record actually tells us about whether he can back up these claims.

How Accelerator Equity Actually Works (And Why It's Been a Pain Point)

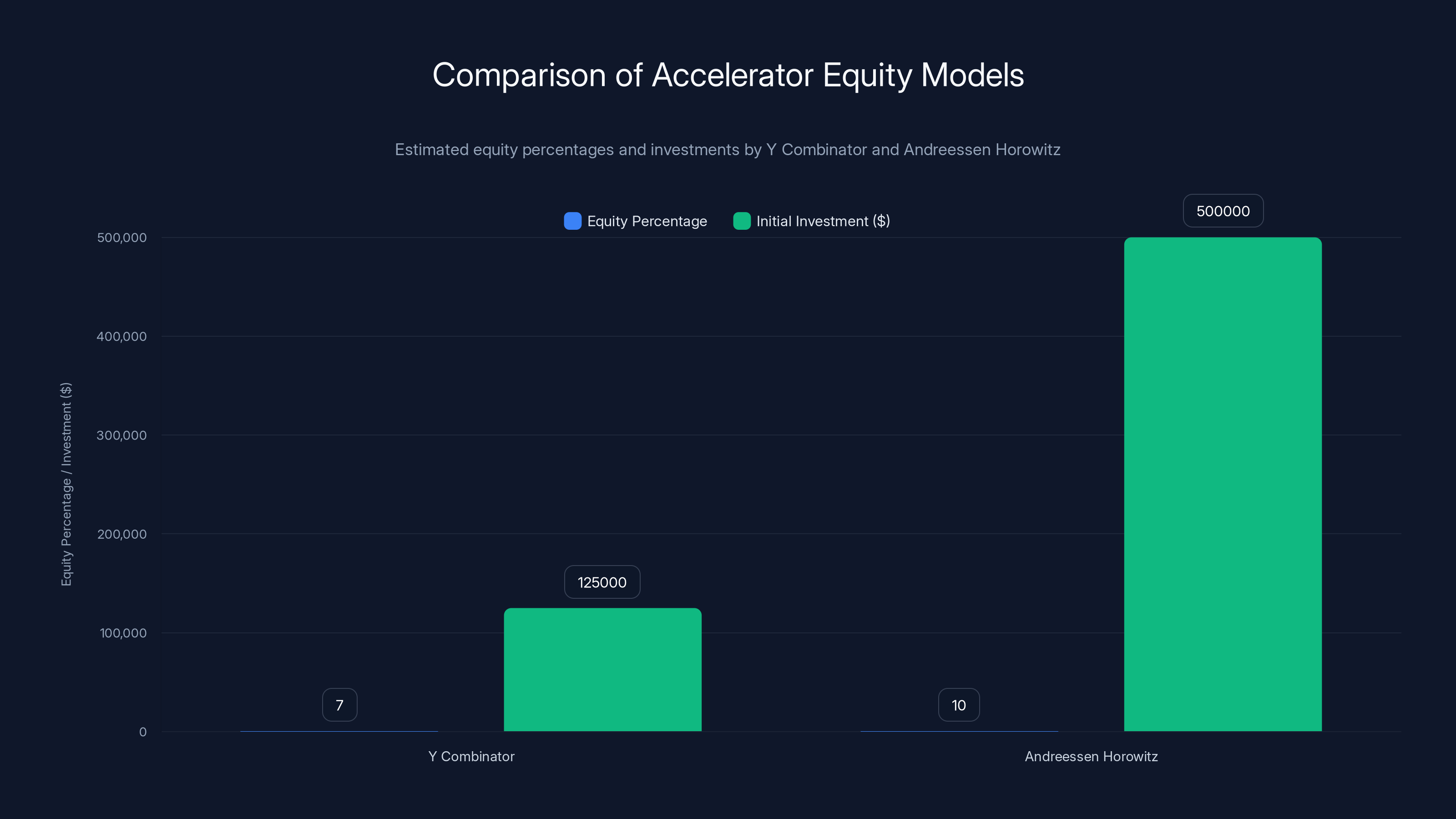

When Y Combinator essentially created the modern accelerator template around 2005, the equity model was straightforward. The accelerator invests money, takes a fixed percentage of the company, and gets board access or observer rights. Y Combinator's standard deal has been 7% of the company for a

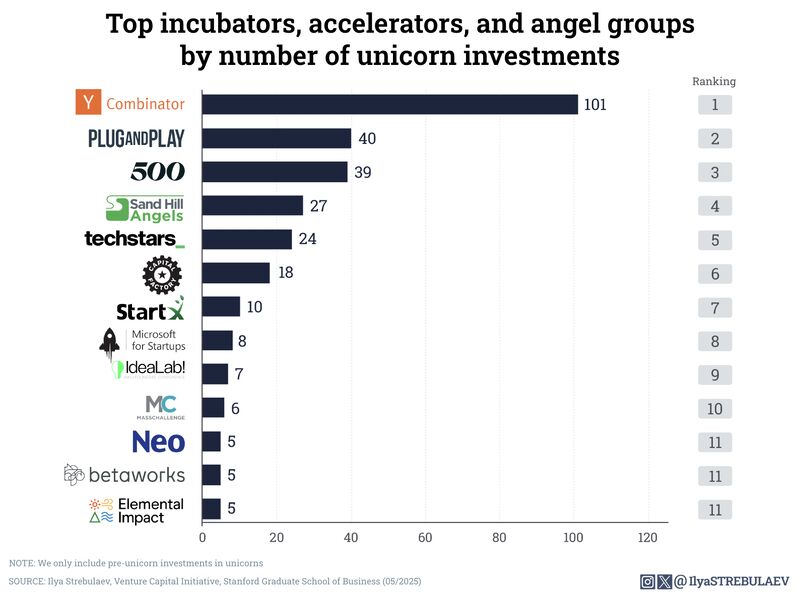

That math seemed reasonable at the time. Most startups were earlier stage, founders often had limited options for capital, and 7% felt like a fair exchange for the network, mentorship, and legitimacy that Y Combinator provided. The firm has deployed this model with remarkable consistency, and it's worked spectacularly. Y Combinator companies have generated more than $300 billion in aggregate value. The equity stake doesn't need to be huge when you're picking winners at that rate.

But something shifted. As more capital flowed into early-stage startups, as angel investors and smaller VCs proliferated, the relative value of an accelerator's equity became more of a negotiating point. Top founders realized they had options. The same mentorship and network effects that Y Combinator provided could be pieced together from various sources. A great founder with momentum didn't necessarily need to give up 7% to get access to patterns and people who'd seen it all before.

Andreessen Horowitz's Speedrun program, launched more recently, typically invests

Meanwhile, other trends were compressing the value proposition of traditional accelerators. Remote work made mentorship less dependent on physical proximity. Slack and Discord communities created peer networks that didn't require a brand name. Founder-to-founder learning was happening on podcasts and Twitter. The scarcity that accelerators had monetized for fifteen years was eroding.

For a certain segment of founders—people who already had some track record, proof of concept, early users—the math of giving up 7% to 10% equity started to feel worse and worse. You're not getting

Partovi's approach targets exactly this segment. He's saying: if you've already got momentum, if you've got a team and an idea that's working, you don't need to give us that much equity. You need capital, mentorship, and community. And we're confident enough in our ability to pick great founders that we can take less upfront, betting that our eventual returns will still be extraordinary because we're backing founders who are going to build something huge.

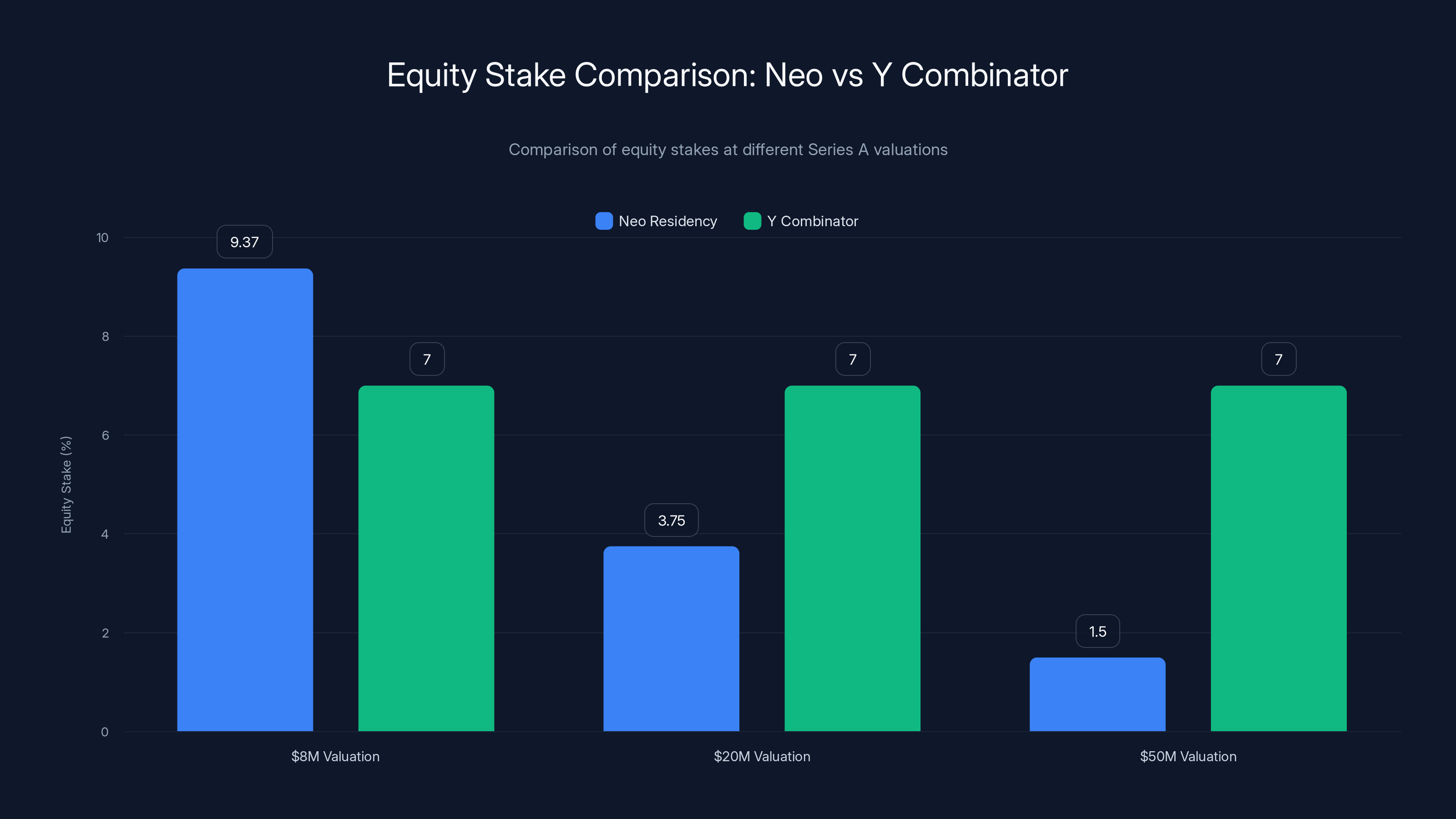

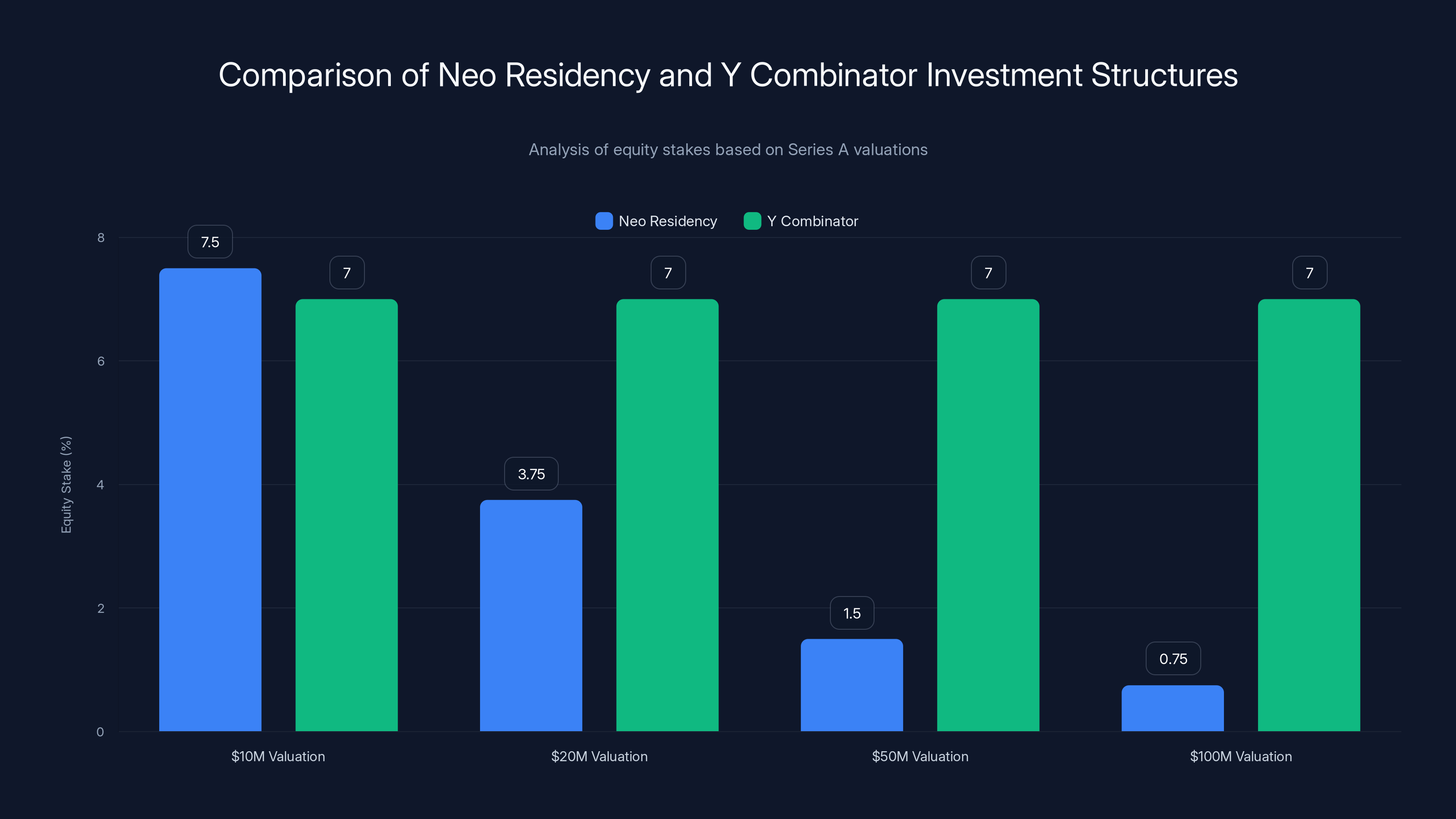

Neo's equity stake decreases with higher valuations, making it more founder-friendly compared to Y Combinator's fixed 7% stake.

The Uncapped SAFE Structure: What It Actually Means

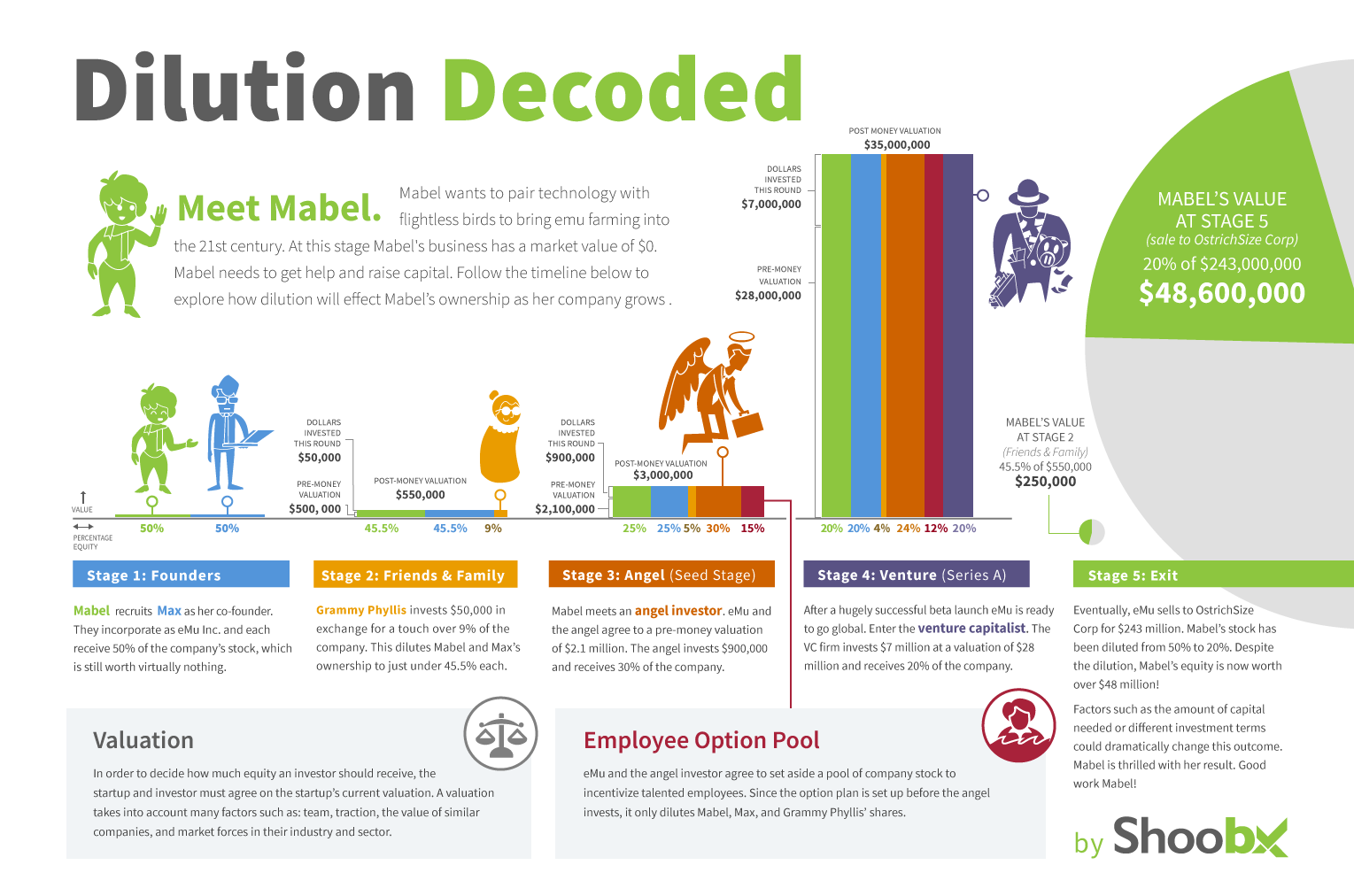

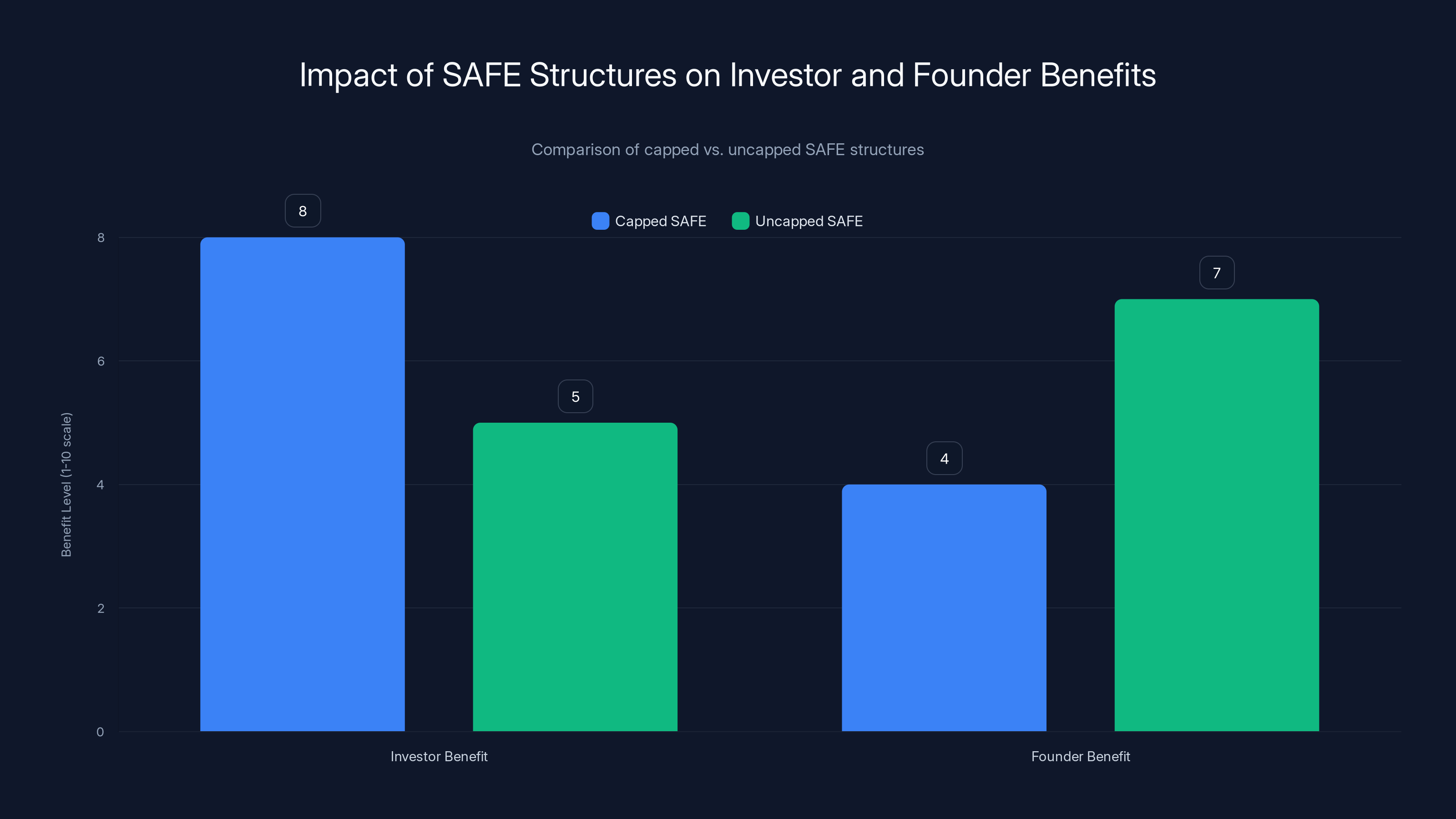

This is where the mechanics get interesting, because "uncapped SAFE" and "valuation-based dilution" are terms that sound bland but actually represent a pretty significant shift in how risk gets allocated between investors and founders.

A SAFE, or Simple Agreement for Future Equity, is a financial instrument that's become standard in early-stage venture. Instead of buying equity immediately, you're buying a future right to equity. The SAFE converts into actual stock when certain milestones are hit, typically the company's next fundraising round. The big advantage for founders is that you don't have to assign a valuation to your company right now. The big advantage for investors is that they're not dealing with stock certificates and all the legal complexity that comes with them.

An "uncapped" SAFE means there's no ceiling on the valuation used to calculate the investor's future stake. So if you raise your Series A at whatever valuation the market will bear, the SAFE holder's conversion is based on that same valuation. A "capped" SAFE, by contrast, has a maximum valuation at which it will convert. So an investor might hold a SAFE with a

Most accelerators use uncapped SAFEs with MFN clauses because it sounds nice and clean. But uncapped doesn't mean unlimited. It means the investor gets diluted by whatever the market does, which can be painful for accelerators if the company blows up in value.

Neo's twist is that they're not just taking an uncapped SAFE. They're taking an uncapped SAFE that converts into equity based on a formula tied to the Series A valuation. Here's how it works: Neo invests

This is genuinely unusual. Most uncapped SAFEs work the same way, actually, but what's unusual here is that Partovi is explicitly marketing this as founder-friendly, building it into the core value proposition of the program, rather than burying it in legal terms.

The implication of Neo's structure is that Partovi is betting heavily on the companies he picks going to big valuations. If a company goes nowhere and never raises again, Neo's stake is effectively zero. If a company raises at a modest Series A valuation, Neo's stake is significant. But if a company goes on to raise at venture-scale valuations, Neo's ownership gets diluted down to nothing. That's risk-taking. Partovi is frontloading the capital and the equity upside is compressed by design.

Why would he do that? Because if he's right about his ability to pick founders (and his track record suggests he actually might be), then he doesn't need to own a lot of the company to get extraordinary returns. A 0.75% stake in a company that goes from

Ali Partovi's Track Record: Does He Actually Know How to Pick Winners?

Partovi's reputation in Silicon Valley rests on a specific type of claim: he has an almost uncanny ability to spot great founders early. Let's look at what evidence we actually have for this.

Partovi is famous for meeting Michael Truell, who would go on to be the founder of Cursor, while Truell was still an MIT student. Partovi wrote one of the first checks into Cursor, which is now valued at nearly

He was an early investor in Facebook. He was an early investor in Kalshi, a prediction market platform that's raised hundreds of millions and represents a meaningful venture-scale outcome. His firm, Neo, has seen companies like Moment, a fintech startup that's raised $56 million from top-tier investors including Andreessen Horowitz, and Anterior, a healthcare AI startup backed by NEA and Sequoia, come through its programs.

The interesting thing about Partovi's track record is that it's been built on early conviction in people, not on owning massive stakes. He didn't need to own 10% of Cursor or Facebook or Kalshi to make extraordinary returns. He needed to be right about the people early.

But there's a selection bias here worth noting. Partovi's most famous bets are hits. We don't hear about the startups he was wrong about, the founders he met who didn't pan out, the early checks that went nowhere. That's the nature of venture capital. You make a lot of bets, most of them don't work, but the ones that do work return 100x or 1000x, which means your overall returns can still be incredible even if your hit rate is only 5% or 10%.

What matters for evaluating Neo Residency is whether Partovi's ability to pick founders translates into a program where founders should genuinely want to participate. And the fact that people like Wesley Chan, co-founder and managing partner of FPV Ventures, are publicly saying that Neo is "very high signal" and that "every founder I met there is just wicked smart" suggests that the program has earned legitimate credibility beyond just Partovi's personal brand.

That credibility matters because it means that getting into Neo Residency probably does create value beyond just the $750,000 capital. The investors downstream will likely be impressed. The mentorship probably is high quality. The network probably is useful. So Partovi can offer lower equity stakes because he's not selling just capital and mentorship, he's selling prestige.

Y Combinator typically takes 7% equity for a

The Economics: How Neo's Deal Stacks Up Against Y Combinator and Others

Let's do some actual math here, because the comparison between Neo's terms and traditional accelerator terms hinges on making some assumptions about future fundraising.

Suppose a hypothetical company goes through Neo Residency. Neo invests

Under Neo's formula:

Now let's compare that to Y Combinator's standard deal. The founder gets

At that same

Neo is getting

But here's where it gets more interesting. What if the company raises at a higher valuation? Let's say $50 million Series A.

Neo's stake:

Y Combinator's stake: still 7%, worth $3.5 million at the Series A valuation.

So at higher valuations, Y Combinator's 7% becomes increasingly expensive for the founder in absolute terms, but Neo's stake gets smaller. This means Neo's deal becomes progressively more founder-friendly as the company succeeds more dramatically.

Conversely, what if the company raises at a lower valuation? Say $8 million Series A.

Neo's stake:

Y Combinator's stake: still 7%.

Here Neo's deal is worse for the founder than Y Combinator's. Neo's implicit founder-friendliness only kicks in if the company's Series A valuation is high enough to make the math work.

This is the key insight: Neo's deal is founder-friendly for companies that succeed spectacularly. For companies that have modest Series A outcomes, Neo's deal might actually be worse. Partovi is explicitly betting that he's selecting companies that will have spectacular outcomes. If he's right, founders in Neo Residency will thank him for low equity dilution. If he's wrong about the quality of his picks, the equity structure becomes less relevant because the companies aren't growing anyway.

The $40,000 Grant for Students: A Different Bet Entirely

Neo Residency is actually two programs in one. There's the main accelerator for active startups getting the

The no-strings part is important. This isn't a loan. There's no requirement to turn it into a formal company immediately. There's no equity stake that Neo takes. It's just money.

On the surface, this looks like philanthropy. But it's actually a really smart venture capital play dressed up as a grant program. Here's why.

Partovi has proven he can spot talent at the MIT student stage. Michael Truell was an MIT student when Partovi met him, and Truell went on to found Cursor. If Partovi can identify great founders while they're still in college, giving them a $40,000 grant to take a semester off and build something is essentially buying an option on that founder's entire venture career.

The founder isn't required to work with Neo when they eventually start a company. But Partovi has built a relationship. He's shown he believes in them enough to fund their idea. That relationship and that signal of belief is incredibly valuable to a young founder who's considering their post-college options. When that founder eventually starts something serious, Neo will be top of mind as a funding partner.

Compare that to Y Combinator's college outreach, which is mainly about getting students to apply to YC once they start companies. Neo is earlier, more generous, and with fewer strings attached. That makes it a more credible signal of belief in the founder.

The program is also explicitly framed as a way to get students to "catch the entrepreneurial bug" and eventually turn to Neo for funding. Partovi isn't hiding that this is a cultivated relationship. He's being transparent about the funnel. Give talented students money to build, some of them will go on to found successful companies, and Neo will have first mover advantage in funding them.

At

Why Small Cohorts Matter: The Signaling Effect of Selectivity

Neo Residency is deliberately small. The program will cap its two annual cohorts at 20 teams each, with a mix of active startups and student projects. So at maximum, Neo is taking maybe 25-30 companies per year across both programs. By comparison, Y Combinator's winter and summer cohorts each typically have 200+ companies.

This is a strategic choice, and it matters for the signal value of the program.

When you go through Y Combinator, you're part of a large cohort. That's great for community and for networking, but it's also true that you're one of 200+. The scarcity of being selected is moderate. When you go through Neo, you're one of 12-15 per cohort. That's a much stronger signal of founder quality. Downstream investors can assume that if Neo thought you were worth bringing into the program, you probably really are exceptional.

Partovi is essentially converting quantity of founder selection into quality of founder signal. By picking fewer companies, he makes the companies he does pick more valuable to know about, and he can afford to take lower equity stakes because the signal value itself is a meaningful part of what he's selling.

This also solves a scaling problem that every accelerator faces. Y Combinator can scale to 400+ companies per year partly because the program is somewhat commodified. You get certain batch programming, certain mentors, certain demos. But the depth of founder access to Partovi is necessarily limited in a program that large.

Neo is staying small because that allows Partovi to actually spend time with the founders, to develop real relationships, and to build the personal conviction that's made him such a good investor. The small cohort size is actually a constraint on scaling, which sounds bad, but which also creates higher scarcity value in the selection.

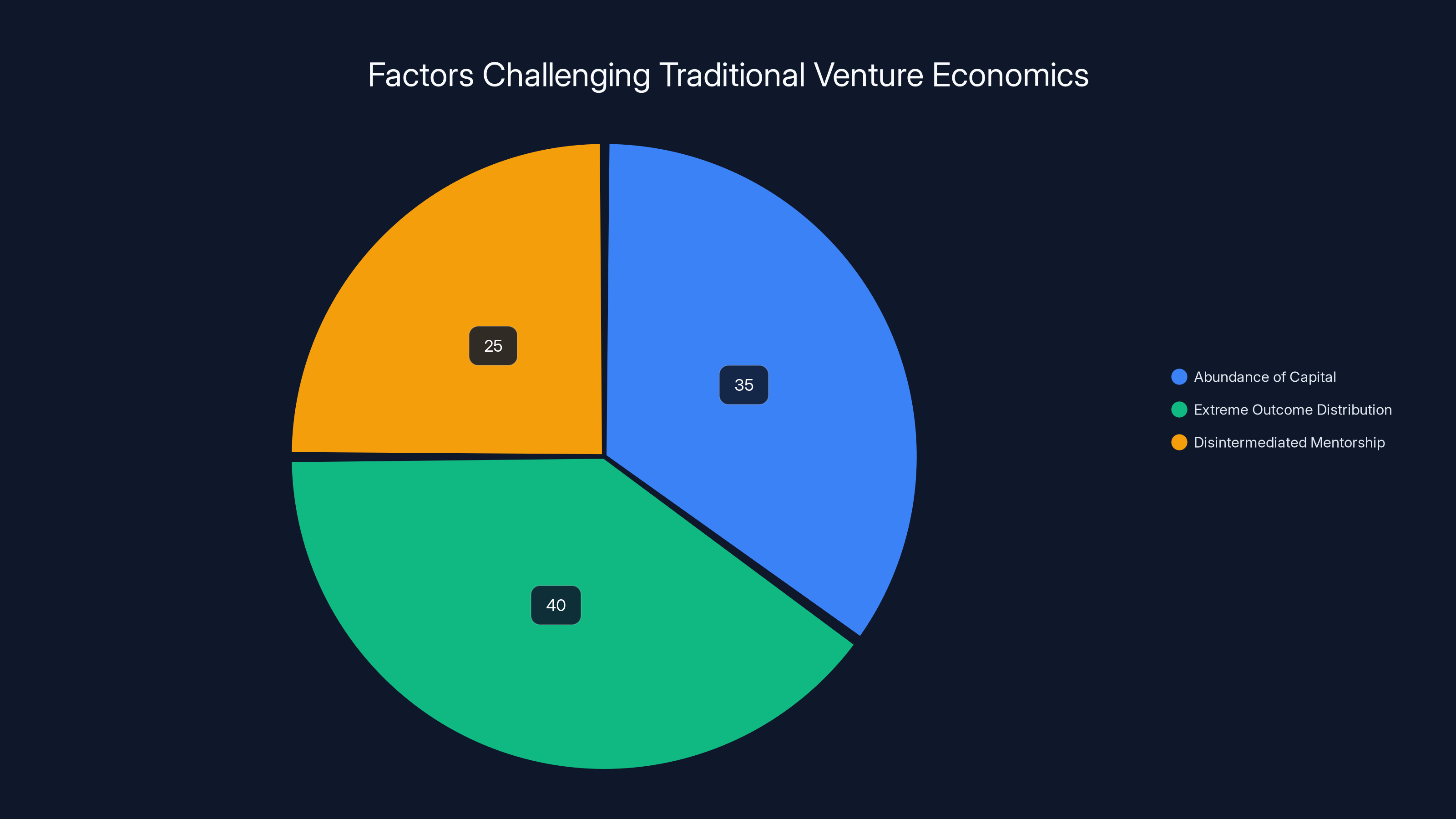

Estimated data shows that extreme outcome distribution (40%) and abundance of capital (35%) are major factors challenging traditional venture economics, with disintermediated mentorship also playing a significant role (25%).

The Prestige Factor: Why Signal Matters More Than You Think

Partovi told TechCrunch that Neo Residency is offering terms "so founder-friendly as to be not even comparable to any other accelerator." That's a strong claim, and it's worth understanding why he can back it up.

The ultimate value that an accelerator provides is signal. The capital is important, the mentorship is useful, but the real juice is being able to tell future investors "I was selected by Program X." Top-tier investors know that certain programs have a track record of picking great founders. That information is valuable, and being able to put it on your cap table or in your pitch deck creates real downstream value.

Partovi's track record gives Neo credibility that many accelerators have to build over years. Wesley Chan from FPV Ventures saying "every founder I met there is just wicked smart" is the kind of feedback that compounds. As more investors discover that Neo startups are legitimately well-selected, the signal value of being selected by Neo goes up.

When the signal value is high, the equity stake can be lower. The founder is getting something other than just capital and mentorship: they're getting institutional belief in their potential that will pay dividends when they fundraise later.

This is why the program's prestige, as Partovi emphasizes, is "the main draw." The $750,000 is real money. The mentorship from people like Russell Kaplan, president of Cognition, and Fuzzy Khosrowshahi, CTO of Notion, is valuable. But the fact that you can tell your Series A investors "Neo picked me, and they're almost never wrong" is the real value creation.

For this to work, Partovi needs to maintain hit rate and selection quality. If Neo goes through a cohort or two and the companies don't perform well, that signal degrades quickly. Partovi is betting his reputation on maintaining selectivity and maintaining quality.

How This Challenge Traditional Venture Economics

The traditional accelerator model, perfected by Y Combinator, worked because it optimized for two things: picking great founders and extracting equity efficiently.

The equity extraction was important because it allowed Y Combinator to build a portfolio of 200+ companies per year. Most of them wouldn't work out, but a few would go through the roof, and the 7% stake in those outliers would return the fund. The capital efficiency of the model—$500,000 deployed to 200+ companies—meant that even with a relatively modest hit rate, the fund economics worked.

But that model doesn't work as well anymore, for several reasons.

First, capital is more abundant. Founders can get

Second, the outcome distribution in venture has become more extreme. More companies are succeeding at very high valuations, and when they do, the opportunity cost of having given up 7% early becomes more obvious. A founder who gave Y Combinator 7% and went on to build a

Third, the value of accelerator mentorship and network has been somewhat disintermediated. You can get mentorship from investors, from other founders, from online communities. You can build your network through Twitter, through conferences, through direct outreach to other founders. The monopoly that traditional accelerators had on access to patterns and people has weakened.

Neo's model, by contrast, optimizes for a different calculus. Rather than trying to deploy capital to as many founders as possible, Partovi is deploying capital selectively and betting that his conviction in founder quality is strong enough that he doesn't need to own as much of the company.

This assumes that Partovi can actually maintain high selectivity (which the small cohort sizes enforce) and that his signal value compounds (which requires consistent founder quality). If both of those things are true, the model works and founders get a better deal than they would at Y Combinator.

If either of those things fails—if Neo's founders don't outperform, or if the signal value erodes—then the model breaks down and founders realize they gave up opportunity cost for less value than they could have gotten elsewhere.

The Broader Shift in Founder-Investor Alignment

What Neo Residency represents is a broader shift in how venture capital is thinking about founder-investor alignment.

For a long time, the venture model assumed that founders needed capital more than they needed anything else, and that capital was scarce enough to justify extracting high equity stakes. Founders were in a weak negotiating position, so they took bad deals.

But the founder power dynamic has shifted significantly over the past decade. Great founders have options. They can raise from angels, from VCs at higher valuations, from SPVs, from revenue-based financing. They can bootstrap. They can raise from international investors who weren't possible to work with before.

When founders have options, the venture capital model has to change. Investors who try to extract too much equity find themselves passed over by founders who found better deals elsewhere. Investors who offer reasonable terms and real value beyond capital get access to the best founders.

Neo's move to lower equity stakes and valuation-based conversion is part of this broader reorientation. Partovi is saying: we know we're not the only option. So we're going to offer terms that acknowledge that. We're going to take less upfront because we're betting on picking winners, not on extracting maximum equity from every company we touch.

This is also a bet that working with better-aligned founders will produce better outcomes. If founders feel like they're getting a fair deal, they'll be more grateful, more open to feedback, more likely to maintain a relationship with the investor over time. Conversely, if founders feel like they got screwed in a negotiation, they'll maintain the relationship out of necessity, but the trust is fractured.

From Partovi's perspective, maintaining strong founder relationships over years or decades is probably worth more than extracting maximum equity in year one. He wants founders to think of him as a partner who believed in them and fought for fair terms, not as a firm that squeezed them in their moment of vulnerability.

Ali Partovi's early investments in companies like Cursor and Facebook have yielded significant returns, showcasing his ability to identify successful founders early. (Estimated data)

The Risk Profile: What Could Go Wrong

For all this to work, several things need to be true.

First, Partovi needs to maintain his track record of spotting great founders. If the next two or three cohorts of Neo Residency companies don't perform well relative to Y Combinator cohorts, the signal value of Neo Residency collapses. Founders will still want capital, but they'll question whether the prestige is worth it.

Second, Partovi needs Series A valuations to stay high. His entire model depends on companies raising at venture-scale valuations where the valuation-based SAFE formula produces low equity stakes. If Series A valuations compress—if founders start raising at

Third, Partovi needs to maintain selectivity. The moment Neo starts taking 20-30 companies per cohort instead of 12-15, the signal value starts to degrade. Scarcity is part of what makes the program valuable. If Neo tries to scale the program to deploy more capital, it undermines the core value proposition.

Fourth, Partovi needs the student grant program to actually produce follow-on investments. If he gives out $320,000 across eight students per year and none of them go on to found venture-scale companies, the program is just a charitable use of capital. It needs to produce optionality on future great founders.

Each of these is a real risk. Venture capital is probabilistic; even great investors are wrong a lot. Partovi's track record is strong, but past performance doesn't guarantee future results.

Implications for How Accelerators Might Evolve

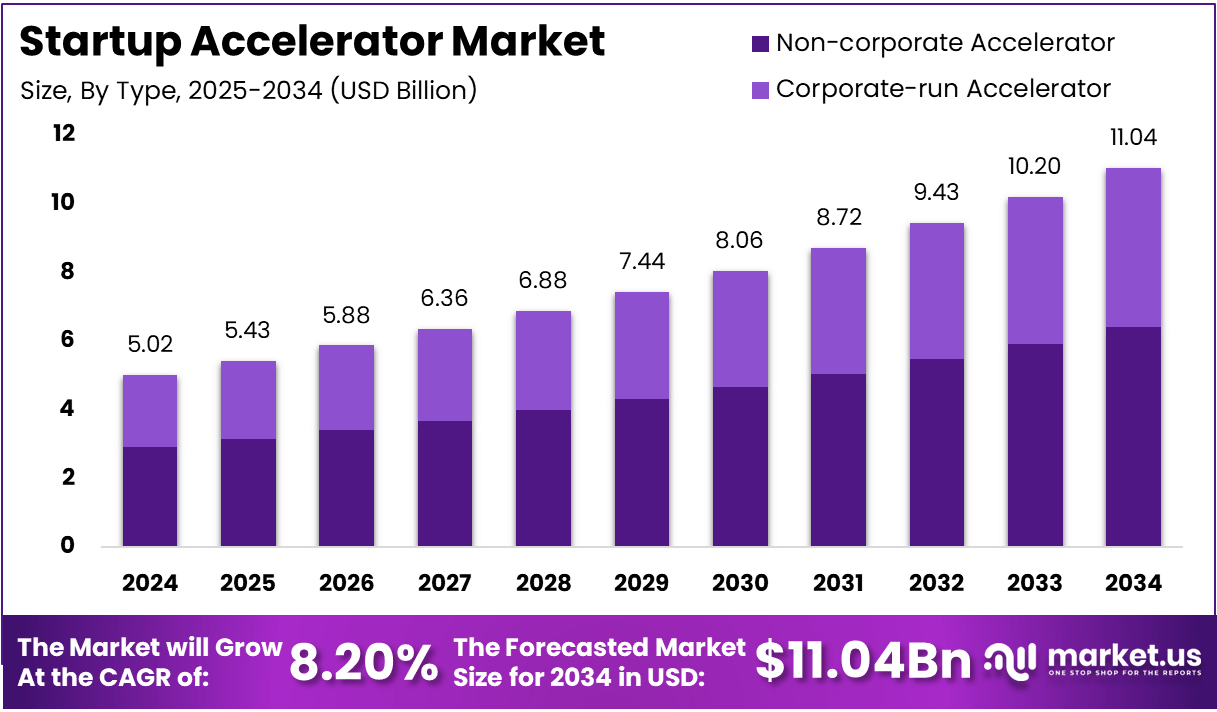

If Neo Residency is successful—if it attracts great founders, if those founders go on to raise well-capitalized Series A rounds, if the signal value compounds—then other accelerators might copy the model.

Y Combinator could respond by lowering its equity stake or offering valuation-based conversion. But Y Combinator has a different value proposition. Its scale—the large cohort, the extensive batch programming, the worldwide brand recognition—is part of what makes it valuable. Y Combinator probably doesn't want to become "small and exclusive" because that would undermine what makes it what it is.

Instead, you might see new accelerators emerge that position themselves as high-selectivity alternatives to Y Combinator, copying Neo's playbook. You might see existing accelerators create premium tracks with lower equity terms and smaller cohorts. You might see traditional VCs launch accelerator-adjacent programs that offer capital plus mentorship but without the equity premium that a traditional accelerator charges.

The broader dynamic is that founder leverage is increasing. More people are building platforms and networks that founders value. More sources of capital exist. Great founders genuinely do have options in a way they didn't ten years ago. Accelerators and investors who fail to acknowledge that will lose access to the best founders.

Partovi's Neo Residency is a clear acknowledgment that the old model doesn't work the same way anymore. Whether it works well is still an open question, but the direction of the shift is clear.

The Community and Mentorship Component

Partovi emphasizes that the program isn't just capital. Founders work out of Neo's offices in San Francisco's Jackson Square, participate in a two-week bootcamp in the Oregon mountains, and get access to about thirty experienced operators for mentorship.

This is the part of accelerators that's hardest to price but potentially most valuable. The mentors are people who've built great companies or led important product work at major companies. Russell Kaplan, president of Cognition, is in the trenches running a company valued in the tens of billions. Fuzzy Khosrowshahi, who created Google Sheets, represents the kind of deep technical expertise that's valuable for founders building new tools.

These people's time is expensive. If Kaplan spends 10 hours per week on Neo mentorship across 15 companies in the cohort, that's roughly two hours per company. At venture partner rates, you might value that at

The bootcamp in Oregon is also interesting. It's two weeks of focused time where founders are away from the normal distractions of San Francisco—no other meetings, no other investors pitching them, no other opportunities. Just intense work and learning alongside other founders. That kind of uninterrupted focus time is genuinely valuable and increasingly rare.

The in-person work out of Jackson Square offices also creates community effects. Founders bump into each other. They solve problems together. They form friendships and professional relationships that probably last decades. Y Combinator has invested heavily in these community effects, and Neo is doing the same.

For this to work as justification for lower equity stakes, the mentorship needs to be genuinely high quality and genuinely available. It's not enough to say thirty mentors are available. They actually need to be there, responsive, and helpful. If mentorship is just a checkbox and founders feel like they're in a program with limited attention, the equity structure becomes less defensible.

Partovi's reputation suggests he's committed to this. He's known for being directly involved with companies he invests in. But it's worth watching whether Neo can scale this level of involvement to multiple cohorts per year without degrading the quality of mentorship.

Neo Residency's equity stake decreases with higher Series A valuations, making it more founder-friendly compared to Y Combinator, which maintains a consistent 7% stake.

Founder Selection: How Neo Actually Picks

Partovi hasn't publicly detailed exactly how Neo selects founders for Neo Residency. But we can infer from his history and public statements.

Partovi clearly values founder quality and founder potential over company stage. He invested in Cursor when it was still an MIT student project. He looks for founders with previous accomplishment—people who've shipped products before, who've led teams, who demonstrate judgment and taste.

He also seems to value founder independence of thought. The founders he's backed tend to be doing something that's contrarian or that the market doesn't fully understand yet. Cursor was building AI coding tools when most people thought AI code would be terrible. That independent conviction is probably something he selects for.

For the college student track, he's probably looking for signals of exceptional ability in young people. Academic achievement, past shipping of projects, unusual intellectual intensity. The goal is to identify people who are going to be exceptional founders before they even know they want to be founders.

The small cohort size means that selection can be more careful and more idiosyncratic. Partovi doesn't need to find 200 great founders every two years. He needs to find 12-15 truly exceptional people. That's a dramatically different selection problem. It's possible to do a lot more diligence. It's possible to meet people in person and spend time with them. It's possible to be selective about founder personality and working style in ways that don't scale to large cohorts.

This selectivity is what creates the scarcity value. If Neo Residency becomes known as the place where Partovi personally identifies the next generation of exceptional founders, that's worth something to a founder independent of capital and mentorship.

The Longer-Term Implications: What This Means for Venture Capital

If Partovi's thesis is right—that he can pick exceptional founders at low equity cost and get extraordinary returns anyway—then it challenges some basic assumptions in venture capital economics.

Traditional venture assumes that the capital is what's scarce and valuable, so you extract equity for it. Neo's model assumes that founder selection is what's scarce and valuable, and capital is just the mechanism to fund that thesis.

This is a meaningful philosophical shift. It's saying that in a world where capital is abundant, the limiting factor for venture returns is picking the right founders. If you can do that, then you can make great returns even at low ownership percentages.

That might be true. If Partovi's hit rate is 20% and his winners return 100x, then he makes extraordinary returns even at 1% or 2% ownership per company. If his hit rate is only 5% but his winners return 1000x, he still makes the math work.

But it's a bet on Partovi's personal ability to identify founders, not on the broader market. It's not a bet that can scale to a 500-person firm making 1,000 investments per year. It requires maintaining the judgment and selectivity that has made Partovi successful.

For venture as an industry, if this model works, you might see a shift toward higher-conviction, lower-volume investing where firms bet more heavily on founder quality and less heavily on capital as the primary value proposition. That's a meaningful reorganization of how venture works.

Alternatively, if this model doesn't work—if Neo's founders underperform Y Combinator and other accelerators—then it validates the traditional model. It would show that the equity stake is actually necessary to make the numbers work, not just a toll for access.

We probably won't know for several years. Series A outcomes are one data point, but the real test is 5 and 10 year outcomes. Do Neo Residency companies go on to build multi-billion dollar companies at higher rates than Y Combinator companies? That's what will actually prove out whether Partovi's thesis is correct.

Practical Implications for Founders Evaluating Accelerators

If you're a founder trying to decide between Neo Residency, Y Combinator, Andreessen Horowitz's Speedrun, or going independent, here are some factors to consider.

Neo's Deal Makes Sense If: You're confident in your ability to raise a well-capitalized Series A within 12-18 months. You value prestige and investor confidence. You want mentorship from operators who've actually built big products. You don't want to dilute yourself to anonymous capital at a generic valuation.

Y Combinator's Deal Makes Sense If: You value the massive network and the distribution of the demo day. You want the most recognizable accelerator brand. You're not sure about your Series A timeline and want lower upfront dilution (even though total percentage might be higher). You value batch community effects with a large cohort.

Speedrun's Deal Makes Sense If: You want Andreessen Horowitz's partnership and distribution beyond just capital. You're willing to pay higher equity for larger capital amounts. You want the specific operational expertise that Andreessen Horowitz brings.

Going Independent Makes Sense If: You can raise capital from angels or smaller VCs at founder-friendly terms. You don't need the prestige signal of an accelerator. You have an existing network and mentors. You want to maintain full control over your company's direction.

Each of these is a legitimate choice, and the right one depends on your specific situation, timeline, and goals.

Capped SAFEs provide more investor benefits due to valuation limits, while uncapped SAFEs offer greater advantages to founders by avoiding valuation ceilings. Estimated data.

The Broader Conversation About Founder Equity and Control

The conversation about accelerator equity is part of a broader conversation happening in venture right now about founder control and alignment.

Founders are increasingly asking whether the traditional venture model—where investors get board seats, protective provisions, and significant equity—actually aligns investor and founder interests in the right way. The argument goes that investors benefit from hitting outlier outcomes, but they also benefit from a certain type of risk-taking and aggressive growth that might not be what founders want for their own lives and companies.

Lower equity stakes and less board control could theoretically mean more founder autonomy. If Neo takes only 0.75% at high valuations, they presumably have less control over company decisions than Y Combinator with 7%. That might be appealing to founders who want to run their company their way.

But it's worth noting that Neo's structure only results in very low equity stakes if the company raises at very high valuations. For a company that raises a Series A at $12 million (below the median for well-funded startups), Neo's stake is 6.25%, comparable to Y Combinator. So the "low control" story only holds for companies that are truly exceptional.

For founders trying to optimize for autonomy and full control, the real answer might be to avoid accelerators altogether and instead raise from angel investors and smaller VCs. That's a harder fundraising path, but it offers more founder control and potentially better founder-favorable terms than any accelerator.

Comparing Neo's Approach to International Accelerators

It's worth noting that Neo's low-dilution model isn't entirely unprecedented. In some international markets, particularly in Europe and Asia, accelerators have historically taken lower equity stakes than Silicon Valley accelerators. This is partly because capital is scarcer in those markets and founders have less leverage, but it's also partly because some accelerators have never adopted the Y Combinator model of extracting 7-10% for smaller capital amounts.

So in a way, Partovi is taking a model that works in other regions and bringing it to Silicon Valley. The question is whether it can actually work in Silicon Valley's more competitive ecosystem where founders have more options.

The answer probably depends on whether Neo can actually maintain the signal value and the mentorship quality that justifies lower equity stakes. In markets where capital is scarcer, founders don't have much choice. In Silicon Valley, they do. Neo has to compete on quality, not just on valuation.

The Risk-Reward Calculus for Partovi and Neo

From Partovi's perspective, the risk-reward of Neo Residency is a specific bet.

The upside is that if he's right about founder selection, he can build a multi-hundred-million-dollar fund by investing $750,000 per company and taking low equity stakes that compound into huge returns because the companies are exceptional.

The downside is that if his founder selection is not actually better than Y Combinator or other accelerators, then he's deploying capital inefficiently. He's giving founders a better deal than they could get elsewhere, which is nice for founders but not great for Neo's returns.

The interesting thing is that Partovi is confident enough in his ability to pick founders that he's publicly willing to take that downside risk. That's either a sign of genuine conviction or a sign of confidence in his ability to talk a good game. Time will tell.

For Neo as a fund, the structure also has implications for capital efficiency. Neo is deploying more capital per company than Y Combinator (

If Neo's founders perform better than Y Combinator's on a per-company basis, then the model works. If they perform comparably despite higher capital deployment and lower equity stakes, then the model struggles. That's the test that will determine whether this is a sustainable innovation or an interesting experiment.

What Founders Actually Want: Signal Beyond Just Capital

The ultimate insight underlying Neo Residency is that founders, particularly exceptional founders, care about more than just capital and mentorship. They care about signal.

Being able to tell your Series A investors "I was selected by the accelerator that picked Cursor at the MIT student stage" is genuinely valuable. It shifts the narrative of your fundraising conversation. Instead of proving your potential, you're leveraging an existing institution's belief in your potential.

That signal becomes more valuable as Neo builds a track record of picking winners. It becomes less valuable if the track record deteriorates. So Partovi has every incentive to maintain quality and selectivity even if it means deploying capital less efficiently than Y Combinator.

This also explains why Partovi is willing to take lower equity stakes. He's not giving up returns; he's betting that the value he creates through signal will result in better founder outcomes, which will result in better company outcomes, which will result in better venture outcomes even at lower ownership percentages.

If you believe that founder alignment and founder confidence are important inputs to startup success, then Neo's model makes intuitive sense. You want founders to feel like they have a partner who believed in them before anyone else, who offered fair terms, and who is invested in their success without being so heavily invested that they're trying to control the company.

The Student Track: Investing in Pre-Founders

The $40,000 grant program for students deserves more attention because it represents a different type of bet entirely.

Traditional accelerators work with founders who are already committed to the venture path. They've quit their jobs or deferred school. They're all-in on the company.

Neo's student grant program is investing in exceptional people who may not yet have made that commitment. The bet is that some of these people will eventually go on to found venture-scale companies, and Neo will have an existing relationship with them.

This is actually a pretty smart application of venture capital. The highest-conviction founders often know they want to be founders, but not all of them have figured out what they want to build yet. Some exceptional people go to college, work at big companies for a few years, and then decide to start something.

By identifying these people early and giving them capital to experiment, Neo is creating optionality. The founder doesn't have to commit to entrepreneurship immediately. But they get to experience what it's like to build something, and they develop a relationship with Partovi and Neo.

When that founder eventually decides to start something serious, Neo has first-mover advantage. The founder already knows Partovi believes in them. They've experienced his judgment and mentorship. They're more likely to come to Neo first than to go through a full fundraising process.

This is actually how the best venture relationships often work. You find people you believe in early, you maintain the relationship over years, and you fund them when they're ready. Neo's student program is just making that process more intentional and more resourced.

Industry Reactions and Competitive Response

Since Neo Residency was announced, the reaction from other accelerators and investors has been mixed.

Some view it as a genuine innovation in accelerator model design that reflects the changing dynamics of founder power. Others view it as Partovi leveraging his personal brand to create exclusivity and then trying to make the economics work through exceptional founder selection.

Y Combinator hasn't publicly commented on Neo Residency, but the firm's silence suggests it's not taking it as an existential threat. Y Combinator's strength is in scale, brand, and network effects. Neo's strength is in Partovi's personal judgment. Those are genuinely different value propositions.

Andreessen Horowitz continues to push Speedrun with higher capital amounts and Andreessen Horowitz partnership, betting that founders care more about large checks and distribution than about preserving equity. That might be true for founders at certain stages.

The broader competitive response is likely to be differentiation rather than direct imitation. Accelerators will try to find their own unique angle rather than trying to become "the low-equity accelerator." Sequoia might lean into founder selection and judgment. Stripe Press might lean into brand and community. Plug & Play might lean into corporate partnerships.

The fact that Neo is possible at all suggests that the founder power dynamic has shifted in ways that reduce the leverage of any single accelerator. Founders can credibly walk away from Y Combinator if the terms don't feel right. That's a meaningful change from a decade ago.

Lessons for Investors and Operators

Neo Residency offers a few lessons beyond just the specific accelerator model:

1. Better selection at lower volume can outperform broader selection at higher volume. If you're genuinely good at identifying exceptional people, you don't need to find thousands of them. You can find dozens and make incredible returns.

2. Signal value is increasingly important as capital becomes abundant. The scarcest resource in venture isn't money anymore; it's legitimate signal that founders are exceptional. Investors who can provide that signal can extract less in other ways.

3. Founder alignment matters. Founders who feel like they got a fair deal and found a genuine partner are more likely to succeed and to maintain the relationship over time than founders who feel squeezed.

4. Personal judgment still creates value. In a world of AI and algorithms and data-driven decision-making, Partovi's personal conviction in great founders is more valuable than ever because it's scarcer.

These lessons apply broadly to venture capital, recruiting, sales, and any domain where you're identifying and partnering with exceptional people.

Trends That Support Neo's Model

Several trends make Neo's founder-friendly model viable in 2025:

Abundant Capital: There's more capital in the system than ever before, particularly for early-stage founders with traction. That abundance gives founders leverage. Accelerators that fail to acknowledge that will lose access to great founders.

Distributed Mentorship: The internet has made it possible for founders to get mentorship from anywhere. A founder in Nebraska can get on calls with operators from San Francisco. That's reduced the scarcity value of geographic proximity that accelerators used to provide.

Founder Leverage: Great founders know they're valuable. They know multiple accelerators would want them. They're willing to negotiate. Accelerators that treat founders as supplicants instead of partners will lose the best ones.

Outcome Compression: More companies are going to spectacular valuations. That makes the opportunity cost of giving up early equity more obvious to founders.

Credibility of Founder Selection: As platforms like Carta and ecosystem tools become more sophisticated, it's increasingly possible to build conviction in founder potential without needing to be the first investor. Early investment is less about being the only one who sees the opportunity and more about being the one who gets it right.

Neo's model works in this context. It probably would have been much harder to implement in 2010.

Future Evolution: Where Could This Go

If Neo Residency is successful and other investors try to copy the model, a few evolutions seem plausible:

1. Founder-Friendly Terms Becoming Standard: Over the next 5-10 years, we might see lower equity stakes and more founder-friendly conversion mechanisms become standard across accelerators, particularly for founders with existing traction.

2. Increased Emphasis on Mentor and Operator Access: As capital becomes even more abundant, the value of accelerator mentorship becomes relatively more important. Programs might compete on mentor quality and availability rather than capital size.

3. Longer-Term Relationships: Instead of three-month cohorts, you might see accelerators develop multi-year relationships where they fund founders at various stages and maintain deeper involvement.

4. Geographic Diversification: Neo is currently in San Francisco, but the model could scale to other geographies where Partovi or other great venture investors have conviction about founders.

5. Integration with Corporate Venture: Large companies might adopt neo-like models as internal programs for identifying and backing promising employees who want to start something.

The Bottom Line: Is This Sustainable

Whether Neo Residency is sustainable depends entirely on founder quality. If the companies coming out of Neo Residency outperform other accelerators, the model works and might inspire imitation. If they perform comparably despite higher capital deployment and lower equity stakes, the model is a luxury that only Partovi's personal brand can support.

The fact that Wesley Chan from FPV Ventures publicly praised the quality of founders in Neo is a good sign. The fact that Cursor and Anterior have raised well from top-tier investors is another good sign. But five or ten years of data will be needed to truly validate the thesis.

For founders considering Neo Residency, the decision should hinge on whether they believe Partovi's signal value is genuine and whether they're confident in their Series A timeline and valuation expectations. For investors in Neo, the decision should hinge on confidence in Partovi's founder selection ability and comfort with the lower equity stakes that result from his model.

Both of those are reasonable bets if you believe in the specific person and the specific thesis. They're riskier bets if you're counting on the model to work independent of Partovi's personal judgment.

FAQ

What is Neo Residency?

Neo Residency is an accelerator program launched by investor Ali Partovi that combines capital investment (

How does Neo's equity structure work?

Neo invests

How does Neo's deal compare to Y Combinator's?

Y Combinator typically takes 7% of a company for

What is the student grant program within Neo Residency?

Neo gives $40,000 no-strings-attached grants to 5-8 college students or small student teams to take a semester off and work on a project. These grants come with no requirement to form a formal company immediately or to work with Neo later, though Partovi hopes students will eventually start companies and choose Neo as their funding partner. This program is designed to identify exceptional founders early and build relationships before they formally launch ventures.

Why does Neo offer lower equity stakes than other accelerators?

Neo offers lower equity stakes because Ali Partovi believes he can reliably identify exceptional founders, making his selection and signal value more valuable than capital and mentorship. Since Neo can pick companies that will likely raise at high Series A valuations, the valuation-based conversion results in low ownership percentages. Partovi is essentially betting that his founder selection ability is rare enough that he doesn't need to own large percentages to generate significant venture returns.

Who should apply to Neo Residency?

Neo Residency is best suited for founders who: (1) are confident in raising a well-capitalized Series A within 12-18 months at a $20 million+ valuation, (2) value the prestige and signal of being selected by Partovi, (3) want mentorship from experienced operators who've built major products, and (4) prefer lower dilution over traditional accelerator equity stakes. The program is smaller and more selective than Y Combinator, making it ideal for founders who want intensive personal attention and are comfortable with Neo's specific value proposition.

What is an uncapped SAFE and how does it differ from other funding instruments?

An uncapped SAFE (Simple Agreement for Future Equity) is a financial contract where an investor provides capital in exchange for a future right to equity, without assigning a specific valuation immediately. The equity stake is determined when the company raises a future funding round. An uncapped SAFE means there's no ceiling on how high the company's valuation can go when calculating the investor's stake. A capped SAFE has a maximum valuation, which protects investors but is less favorable to founders. Neo uses uncapped SAFEs with valuation-based conversion, which is founder-favorable when Series A valuations are high.

How does Neo Residency create value beyond the capital injection?

Neo creates value through mentorship from about 30 experienced operators (including Russell Kaplan, president of Cognition, and Fuzzy Khosrowshahi, creator of Google Sheets), community with other founders in a small cohort, in-person work at Neo's San Francisco offices, a two-week intensive bootcamp in the Oregon mountains, and crucially, the signal value of being selected by Partovi. Downstream investors view Neo selection as strong evidence of founder quality, which helps with Series A fundraising. The mentorship, community, and signal together may provide more value than traditional accelerator programs despite the lower upfront capital.

What is the historical context for Neo Residency's low-dilution approach?

For years, Y Combinator's model of taking 7% for $500,000 was the standard for prestigious accelerators. However, capital abundance, distributed mentorship networks, and founder leverage have shifted the dynamics. Exceptional founders now have many capital sources available and can credibly negotiate better terms. Neo's low-dilution approach reflects this shift in founder power and the realization that great investor conviction and founder selection may be more valuable than maintaining high equity stakes. Some international accelerators have used similar low-dilution models for longer, but Neo is bringing this approach to competitive Silicon Valley.

What could go wrong with Neo's model?

Neo's model depends on multiple conditions: (1) Partovi must maintain his track record of picking exceptional founders, (2) Series A valuations must stay high to make the math work (lower valuations mean Neo's equity stakes become larger), (3) Neo must remain selective and small (scaling would dilute signal value), (4) the student grant program must identify future great founders (if they don't become successful, it's just charitable giving), and (5) Neo's founders must outperform comparable accelerators. If any of these conditions fail, the model becomes less attractive to founders. Additionally, if the broader venture ecosystem moves away from high Series A valuations, Neo's founder-friendly structure could become less meaningful.

Key Takeaways

- Neo Residency's 15M valuation vs 0.75% at $100M)

- Compared to Y Combinator's fixed 7% for 20M+ valuations; below that threshold Neo's stake can exceed Y Combinator's

- Partovi's model bets on founder selection quality over capital control, leveraging his track record (Cursor, Facebook, Kalshi) to offer lower equity stakes while maintaining venture returns through backing exceptional founders

- The program's small cohort size (12-15 startups per cohort vs 200+ for Y Combinator) creates scarcity value and strong signal effect for downstream Series A investors

- Neo's $40K student grant program identifies early-stage founder talent pre-commitment, creating long-term relationships and optionality on future venture-scale companies

Related Articles

- Why Divvy's $1B Exit Left Founders With Nothing: The Debt & Cap Table Truth [2025]

- Thrive Capital's $10B Fund: What It Means for AI and Venture Capital [2026]

- Cherryrock Capital's Contrarian VC Bet on Overlooked Founders [2025]

- Anthropic's $30B Funding, B2B Software Gravity Well & AI Valuation [2025]

- OpenAI's 850B Valuation Explained [2025]

- AI Data Centers Hit Power Limits: How C2i is Solving the Energy Crisis [2025]

![Neo's Low-Dilution Accelerator Model: Reshaping Founder Economics [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/neo-s-low-dilution-accelerator-model-reshaping-founder-econo/image-1-1771569810248.jpg)