Real-Time AI Inference: The Enterprise Hardware Revolution in 2025

Introduction: Beyond the Smooth Illusion of Exponential Growth

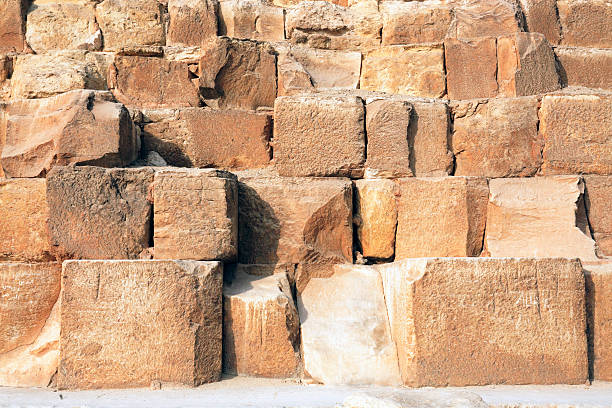

When you stand miles away from the Great Pyramid of Giza, it appears to be a perfectly smooth geometric monument—a sleek triangular structure pointing toward the heavens. But venture closer, and the illusion shatters. What seemed like a continuous slope reveals itself to be a staircase of massive limestone blocks, each one distinct, jagged, and requiring deliberate effort to traverse.

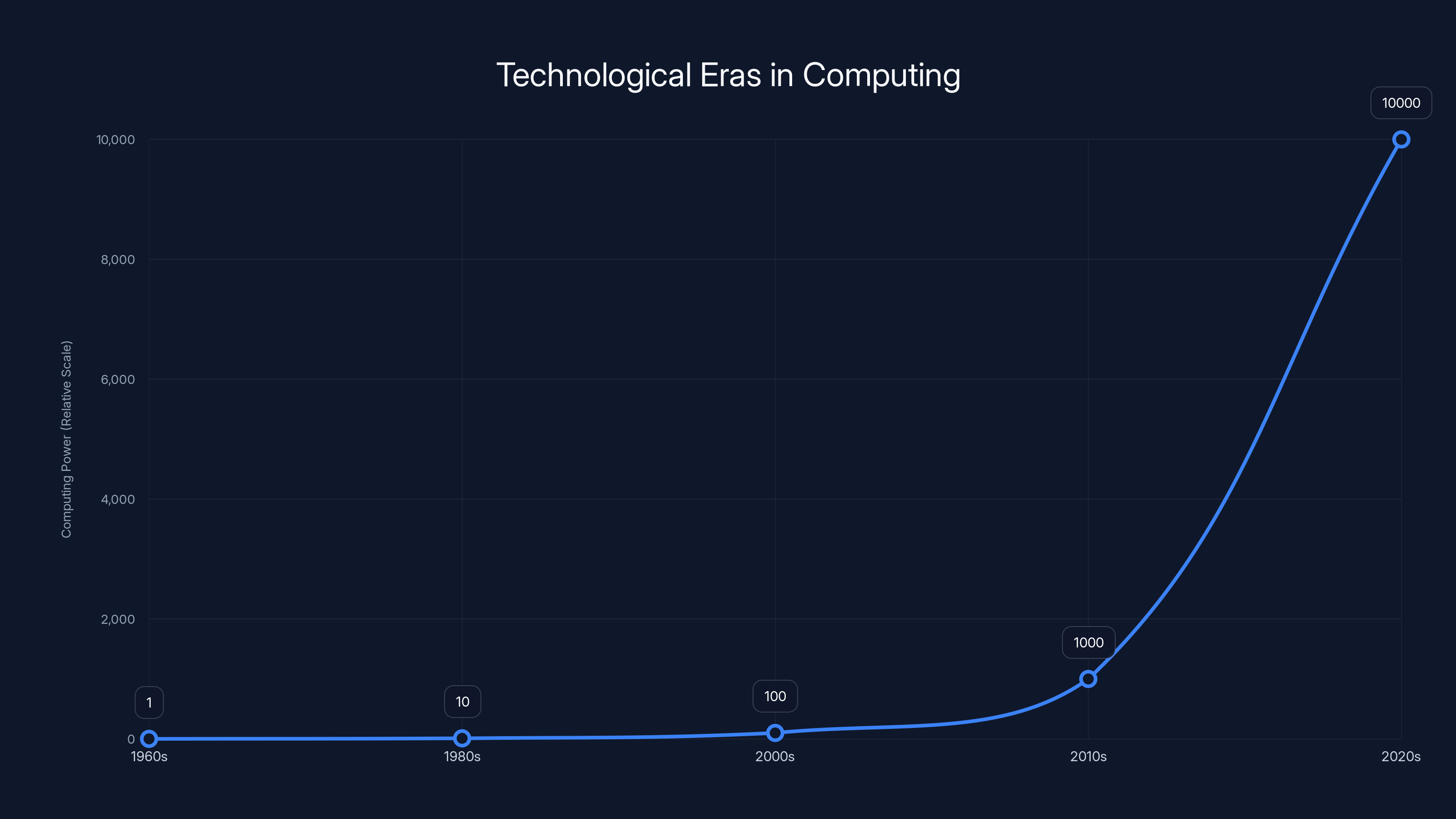

This architectural metaphor perfectly captures the reality of technological progress, particularly within artificial intelligence. We live in an age where "exponential growth" has become the dominant narrative in tech discourse. Futurists speak of continuous acceleration, of smoothly ascending curves that extend infinitely upward. Yet the actual history of computing—from Moore's Law to GPU adoption to modern AI—tells a different story entirely. Technology doesn't grow smoothly. It advances in distinct blocks, each plateau followed by a transformative shift that reshapes entire industries.

Intel's co-founder Gordon Moore observed in 1965 that the transistor count on microchips would double annually. Later, fellow Intel executive David House refined this observation, predicting that compute power would double approximately every 18 months. For decades, this prediction held remarkable accuracy. Intel's processors became synonymous with computing progress itself. The CPU was the universal hammer, and every computational problem looked like a nail waiting to be struck with greater frequency and efficiency.

But then the limestone block flattened. CPU performance improvements plateaued. The curve that seemed destined to climb forever hit a physical ceiling. Thermal constraints, quantum tunneling effects, and architectural limitations meant that simply making transistors smaller and more numerous couldn't continue indefinitely. The exponential would not, it seemed, continue.

Yet exponential growth didn't die—it merely migrated. A new limestone block appeared in the computational landscape: graphics processing units. Initially designed to render pixels in video games, GPUs revealed capabilities far beyond graphics rendering. Their parallel architecture made them ideal for the matrix multiplications that underpin deep learning. Jensen Huang and Nvidia, building on decades of gaming industry experience, positioned their hardware as the enabling technology for the AI revolution.

Nvidia's ascent has been nothing short of spectacular. The company orchestrated a masterclass in long-term strategic positioning: from gaming graphics to computer vision to generative AI, each transition was planned not as a pivot but as a natural evolution of GPU capabilities. Huang's vision—recognizing these shifts before they became obvious—transformed Nvidia from a specialized graphics company into the foundational infrastructure provider for the entire AI industry.

But we find ourselves at another inflection point. The AI revolution has been built on transformer architecture and the scaling paradigm: bigger models, more parameters, greater computational throughput. The assumption was that scaling—raw compute power applied to increasingly massive neural networks—would unlock increasingly powerful intelligence. And this approach delivered remarkable results. Large language models evolved from novelties to essential tools across industries.

Yet subtle signs suggest we're approaching another limestone block plateau. The scaling assumptions that drove the last five years of AI progress are bumping against practical, economic, and physical constraints. The cost of training frontier models has become astronomical. The energy requirements are staggering. The returns on additional parameters are diminishing. Meanwhile, the inference phase—where trained models are actually deployed and used—has revealed new bottlenecks that raw GPU power alone cannot solve.

This is the inflection point that defines 2025 and beyond. The question is no longer merely "how do we train bigger models?" but rather "how do we run intelligent, reasoning-capable systems in real-time, with latency measured in milliseconds rather than seconds, while managing the economic and environmental costs of continuous inference?"

The answer involves a fundamental rethinking of hardware architecture, a recognition that inference is a fundamentally different computational problem than training, and a new generation of specialized processors designed for speed rather than raw throughput. Understanding this shift is essential for any enterprise deploying advanced AI systems. This article explores the technological, economic, and strategic implications of this transition—why it matters, who's winning, and how it will reshape enterprise AI deployment over the next decade.

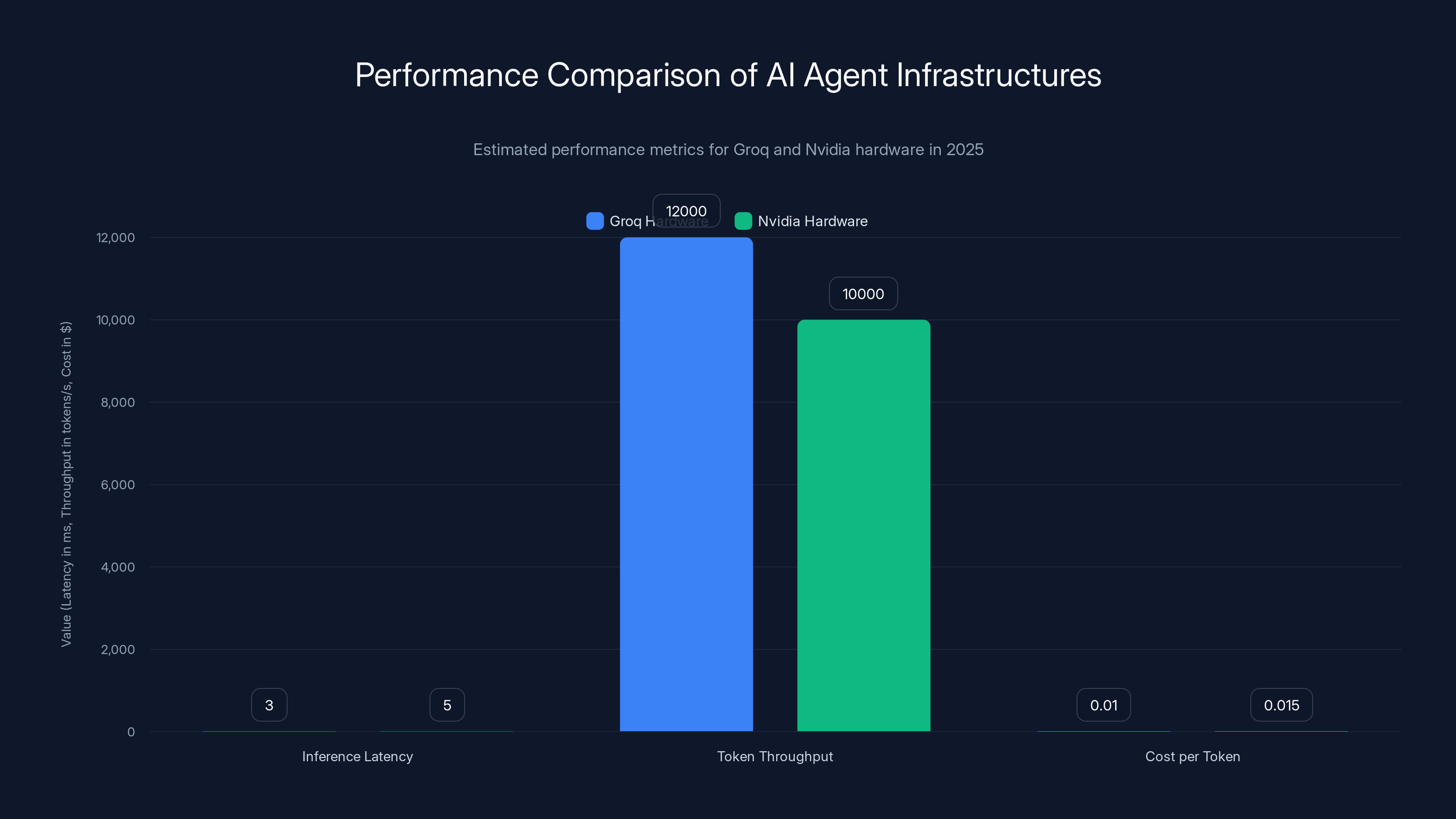

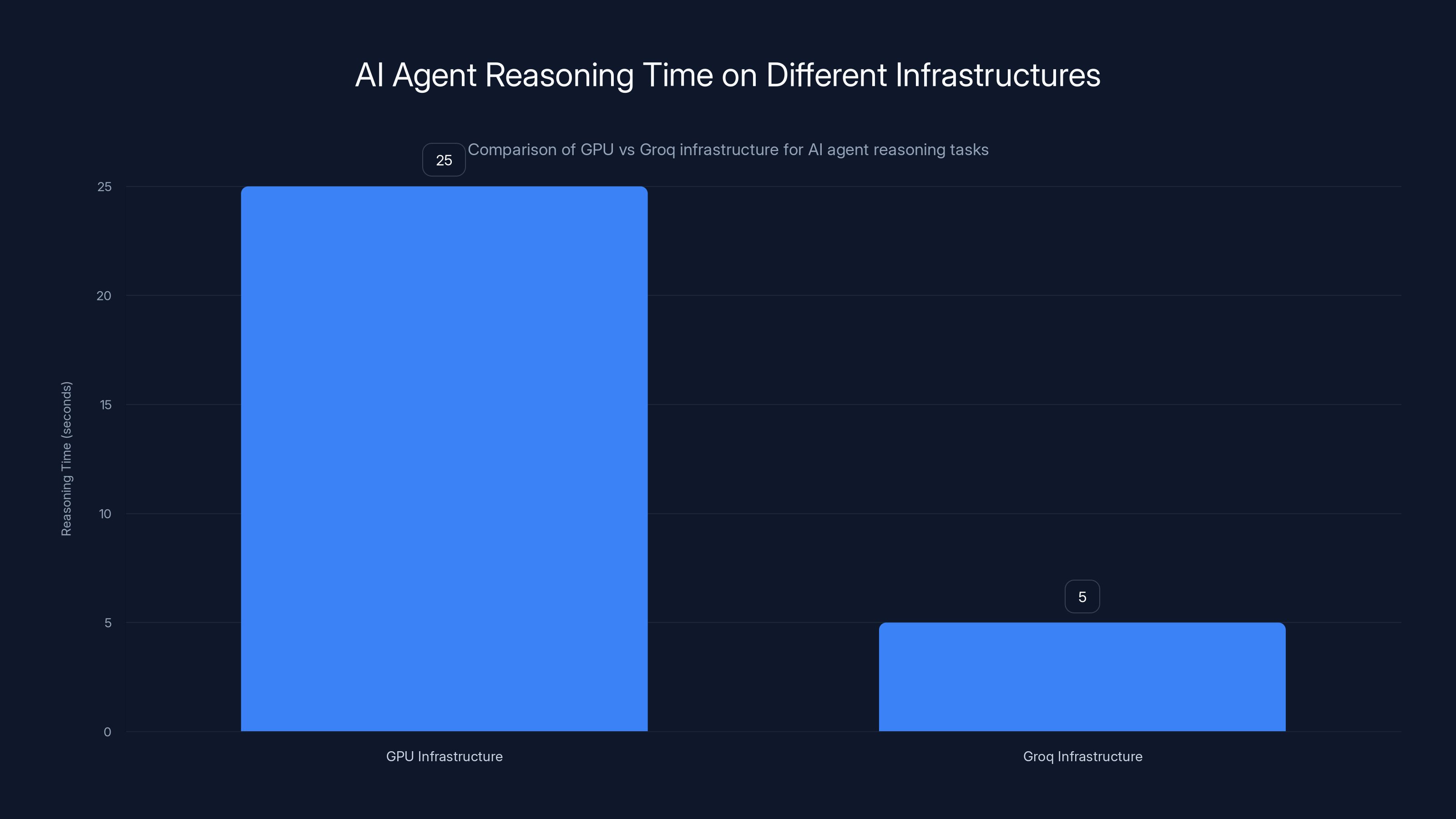

Groq hardware demonstrates lower latency and higher token throughput compared to Nvidia, making it more cost-effective for concurrent AI agent workloads. (Estimated data)

The Architecture of Exponential Progress: Understanding Technology's Staircase

How Computing Progress Actually Works

Technological advancement rarely follows the smooth exponential curve that finance models predict. Instead, progress resembles a staircase where each step represents a distinct era defined by a dominant technology. Understanding this pattern is crucial for comprehending the current AI infrastructure transition.

The history of computing demonstrates this principle repeatedly. The mainframe era gave way to minicomputers, which yielded to personal computers, which transformed when the internet became prevalent. Each transition involved a new foundational technology that made the previous approach seem quaint and inefficient. The personal computer didn't merely make mainframes faster—it made them irrelevant for certain applications. The internet didn't just improve minicomputers—it introduced entirely new problems and possibilities that those systems couldn't address.

Within each era, we do see exponential progress. Moore's Law operated with remarkable accuracy throughout the CPU era from the 1970s through the 2000s. But this progress was always within the constraints of a particular architecture. Once those constraints became binding, progress didn't simply slow—it stopped, because you'd reached the physical limits of the existing paradigm.

The transition from CPU to GPU in AI workloads follows this exact pattern. From 2012 onwards, deep learning researchers discovered that the massively parallel architecture of graphics processors was superior to sequential CPU processing for neural network training. This wasn't a minor optimization; it was a complete paradigm shift. The same computation that took weeks on CPUs could be completed in days on GPUs. The same process that required rooms full of servers could run on a single workstation with GPU acceleration.

Nvidia's dominance emerged not from superior marketing but from superior understanding of this inflection point. The company recognized, ahead of competitors, that GPUs would become essential infrastructure. They invested in CUDA, a programming framework that made GPU computing accessible and standardized. This wasn't just about hardware; it was about ecosystem. CUDA created a moat so wide that competitors struggled to offer viable alternatives. By the time the AI boom became obvious, Nvidia's software advantages were as significant as their hardware superiority.

The Scaling Paradigm and Its Constraints

The current AI era has been defined by what industry insiders call the "scaling hypothesis." This principle posits that intelligence emerges from scale: bigger models with more parameters, trained on larger datasets, using more computational resources, produce more capable systems. The evidence supporting this hypothesis has been compelling. Each generation of language models—from GPT-2 to GPT-3 to GPT-4—demonstrated that simply increasing model size and training data produced systems with emergent capabilities that smaller models lacked.

This paradigm has driven explosive investment in GPU capacity. Data centers globally have been refitted and rebuilt around GPU clusters. Companies have spent tens of billions on these installations, betting that the scaling hypothesis would continue to deliver returns indefinitely. Nvidia's valuations reflect this bet—the company's market capitalization exceeded $1 trillion because investors believe the scaling paradigm will persist for years.

However, several constraints are becoming visible at the horizon. First, the economic constraint: training state-of-the-art models now costs hundreds of millions of dollars. Open AI's expenditures on model training have been reported in the range of

Second, the data constraint: we are approaching the exhaustion of high-quality training data available on the internet. Language models trained on public data have been through multiple generations of refinement. The marginal value of additional generic text is declining. Improvements in capability will increasingly come from synthetic data, specialized datasets, and technique refinement rather than simply feeding more data to models.

Third, the energy constraint: the electricity consumption of training and operating large language models is staggering. A single training run of a frontier model can consume as much electricity as a small country does in hours. As the industry scales, energy costs and environmental concerns will increasingly constrain further expansion.

These constraints don't mean the scaling paradigm is ending, but they do suggest that pure scaling will not be the primary driver of progress. Instead, we're seeing innovation in three directions: architectural efficiency (building models that deliver more capability per parameter), specialized deployment (using different systems for different tasks rather than one universal model), and inference optimization (making deployed models run faster and cheaper).

The Shift from Training to Inference Optimization

For the first decade of the deep learning revolution, the focus was almost exclusively on training. The implicit assumption was that if you had a powerful enough model, deployment would be straightforward. You'd run the model on servers, and it would generate predictions or completions. The computational demands during inference were treated as an afterthought.

This assumption was reasonable when models were smaller and latency requirements were loose. A natural language processing system that takes a few seconds to process a request is perfectly acceptable for many applications. A recommendation engine that takes a second to generate suggestions is fine. A chatbot that responds in three seconds feels responsive.

But as models have grown larger and as applications have become more complex, inference has revealed itself as a distinct computational challenge. The requirements during inference are fundamentally different from those during training.

During training, you want to maximize throughput. You have batches of data, and you process them in parallel across thousands of GPUs. You're performing the same operations repeatedly on large matrices. You can afford to wait seconds or minutes for results because training jobs run for weeks or months. Optimization focuses on moving data through processors as quickly as possible.

During inference, you want to minimize latency and often operate on much smaller batch sizes. A user submits a request and expects a response in milliseconds to seconds, not minutes. A single request from a user generates a specific computation that follows a particular path through the model. The computational pattern is fundamentally different from training.

Moreover, modern AI agents and reasoning systems introduce new requirements. These systems don't just generate a single response; they engage in complex chains of thought, internal verification, and iterative refinement. A model might generate 10,000 or 100,000 intermediate tokens internally before producing a single token visible to the user. This internal reasoning process must happen fast, because latency compounds through these long chains of computation.

This is where we encounter the fundamental limitation of GPUs for inference workloads: memory bandwidth. Modern GPUs are designed to handle massive parallelism. They excel at pushing tremendous amounts of data through compute units simultaneously. But during inference on smaller batches, much of that parallel capability sits idle. Instead, the bottleneck becomes the speed at which data can move from memory to processors.

GPUs have enormous memory bandwidth—hundreds of gigabytes per second in modern architectures. But this bandwidth is optimized for dense, parallel operations. When you're doing small-batch inference with models where each token generation is a relatively light computational load, you hit diminishing returns. You're waiting for data movement more than you're waiting for computation.

This constraint has created an opportunity for specialized hardware designed specifically for the inference workload: processors that optimize for low latency, support smaller batch sizes efficiently, and focus on the specific operations required for token generation in transformers. This is the foundation of the current infrastructure competition reshaping the industry.

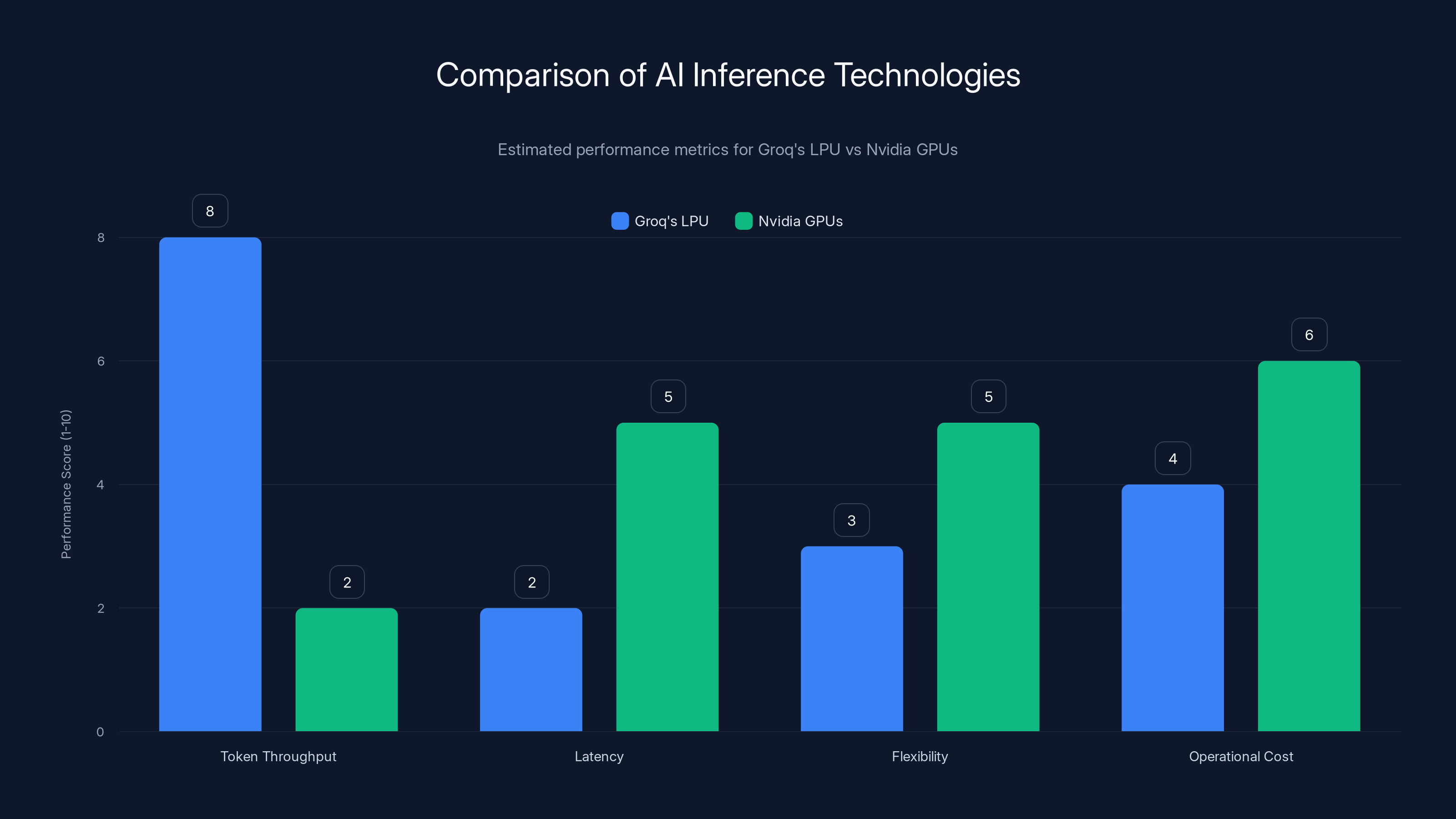

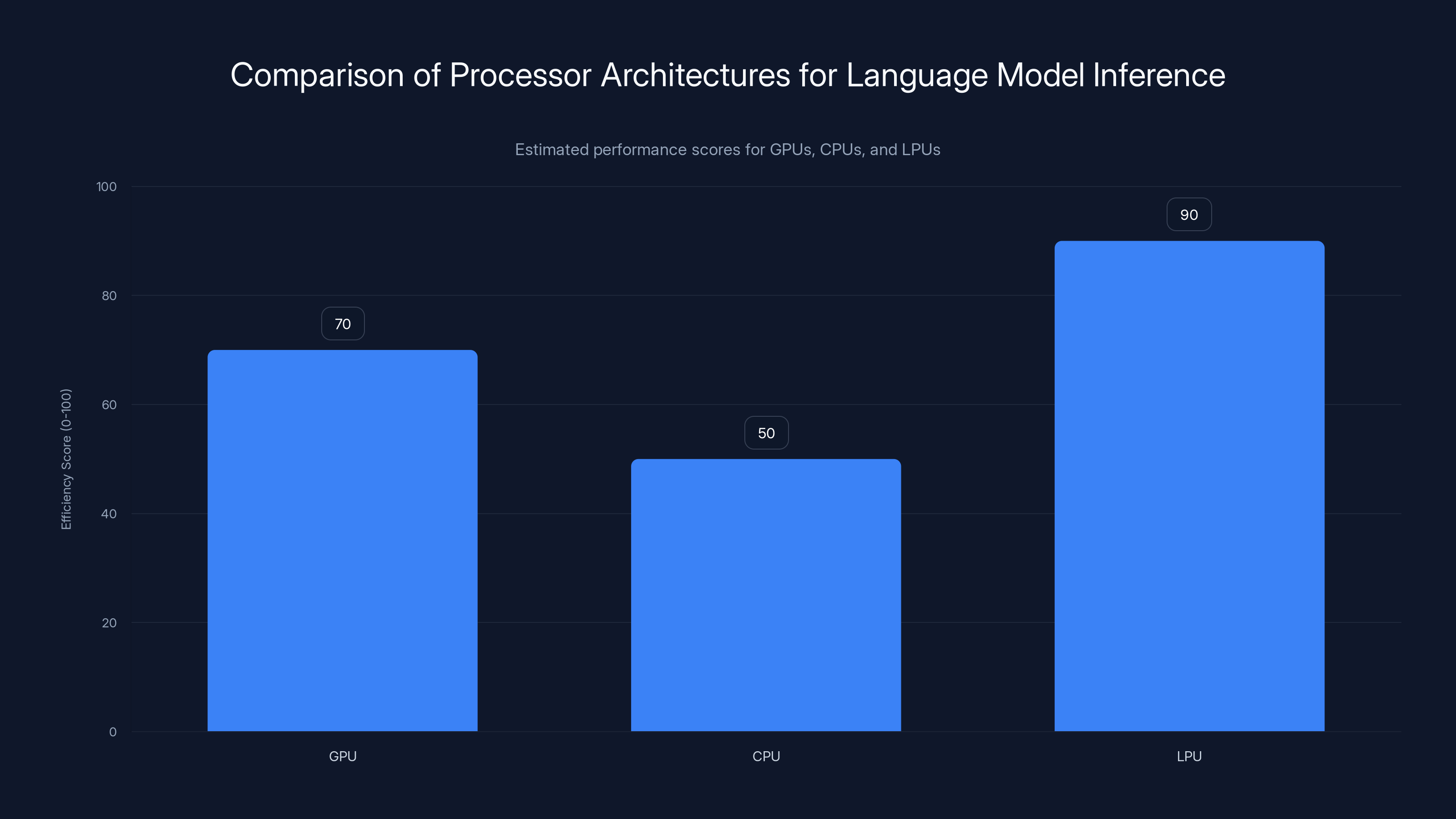

Groq's LPU excels in token throughput and latency, while Nvidia GPUs offer greater flexibility and lower operational costs. Estimated data based on typical performance characteristics.

Groq and the Language Processing Unit: Specialized Inference Hardware

The Genesis of Language Processing Unit Architecture

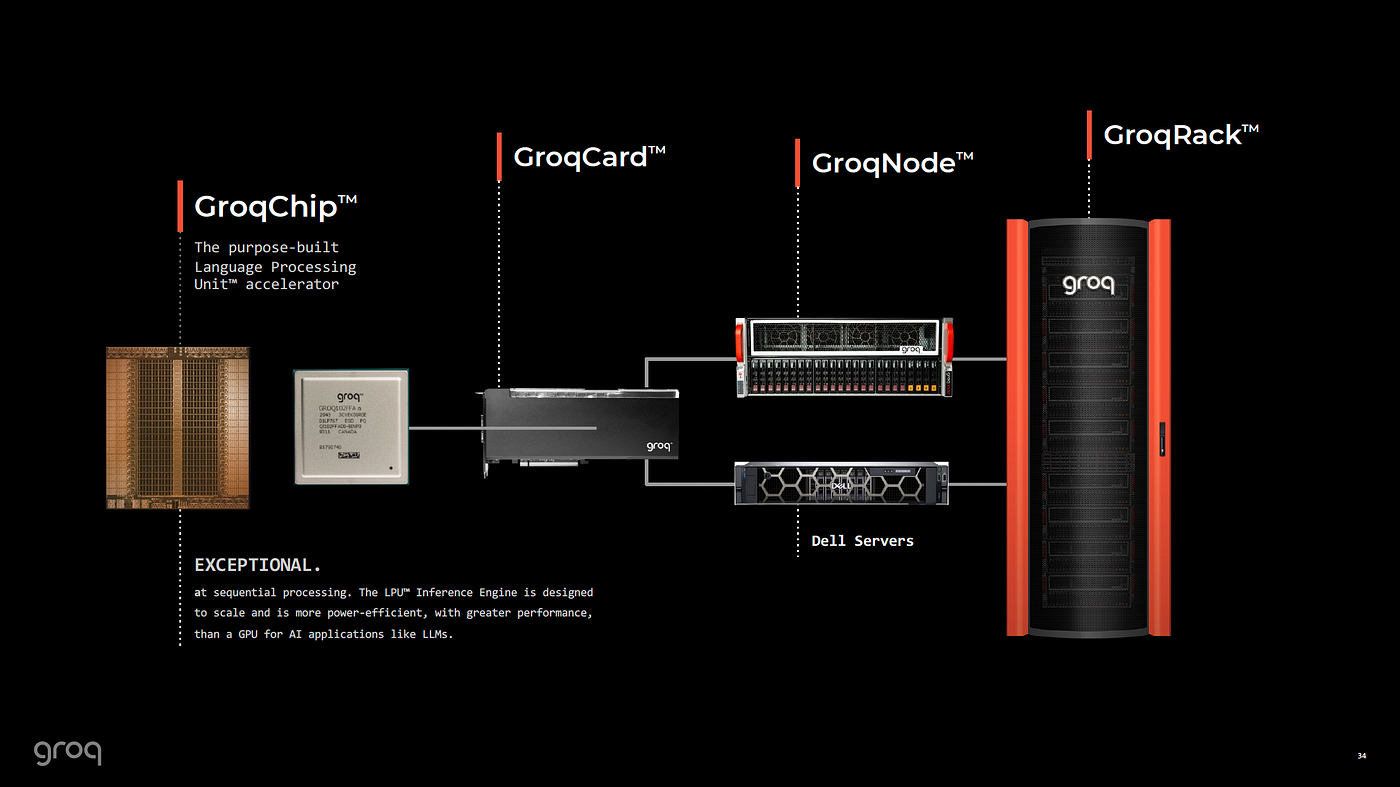

Groq, founded in 2016 by former Google engineers, spent years developing a fundamentally different approach to processor design. Rather than building another GPU variant, the team asked a basic question: what would a processor optimized specifically for language model inference look like?

The company's answer was the Language Processing Unit, or LPU. This is not a minor optimization of existing GPU architecture but a genuinely different computational approach. The LPU eliminates the memory bandwidth bottleneck that constrains GPU inference through several key architectural decisions.

First, the LPU implements deterministic execution. Traditional processors, particularly GPUs, use speculative execution and complex cache hierarchies to predict what data will be needed and prefetch it. This works well when computational patterns are irregular and unpredictable. But transformer inference follows highly predictable patterns. The same operations execute repeatedly in sequence. Groq's deterministic execution eliminates the prediction overhead and guarantees exactly when data will be required and when it will be consumed.

Second, the LPU implements a custom instruction set specifically optimized for the operations used in transformer models. While CPUs and GPUs implement broad instruction sets that support arbitrary computation, the LPU focuses on the specific matrix operations, attention mechanisms, and feed-forward transformations that constitute nearly all the work in language models. This specialization means instructions can be more efficient and operations can be optimized in ways that would be impossible in a general-purpose processor.

Third, the LPU's memory hierarchy is designed specifically for language model inference. Rather than the generalist caches found in traditional processors, the LPU implements a memory system optimized for the specific data access patterns of transformer inference. This reduces stalls and memory access latency for the specific operations that matter most.

The result is a processor that, while potentially delivering lower peak throughput than GPUs on some synthetic benchmarks, delivers dramatically higher throughput on actual language model inference workloads. More importantly, it delivers this throughput with much lower latency. Inference that might take 20-40 seconds on a GPU cluster can complete in 1-3 seconds on Groq hardware, a reduction of an order of magnitude or more.

Performance Characteristics in Real-World Deployment

The performance gains from Groq hardware manifest most dramatically in scenarios requiring low-latency, high-throughput reasoning. Consider the canonical example that has become industry-standard for benchmarking inference hardware: generating a sequence of 10,000 tokens with a frontier model.

On traditional GPU infrastructure, generating 10,000 tokens for a single user request involves profound latency challenges. A high-end GPU configuration might achieve token generation rates of 100-300 tokens per second per device. To generate 10,000 tokens therefore requires 30-100 seconds. For an interactive user experience, this is essentially non-functional. The user would abandon the interaction long before receiving a response.

Groq systems achieve token generation rates of 500-1,500 tokens per second or higher, depending on the model and hardware configuration. This means the same 10,000-token generation completes in 6-20 seconds. More importantly, the tokens can be streamed back to the user immediately, creating an impression of real-time thinking.

But the real revolution in performance comes when considering agentic systems where the model must reason internally before providing output. An AI agent tasked with booking a flight might need to: search for available flights (200 tokens), evaluate options against user preferences (500 tokens), check calendar availability (300 tokens), verify payment methods (200 tokens), and then generate a natural language response (100 tokens). That's 1,300 internal tokens before the system outputs a single word to the user.

On GPU infrastructure, this would take 5-10 seconds. On Groq, the same process completes in 1-2 seconds. This difference is transformative for user experience. It's the difference between a system that feels like an AI assistant and one that feels unresponsive.

Groq's inference speed also creates economic advantages. Since inference costs are typically proportional to computation time, hardware that completes inference in 25% of the time costs approximately 75% less to operate. For large-scale inference operations processing millions of requests daily, this compounds into massive cost savings.

The Software Stack Challenge

Despite impressive hardware performance, Groq has faced a persistent challenge in software ecosystem development. The company's LPU hardware, like any specialized processor, requires software optimized specifically for that architecture. This includes compilers, frameworks, and model implementations tailored to LPU strengths and limitations.

Nvidia's advantage in this dimension is substantial. The company has spent decades building CUDA, an ecosystem so comprehensive and so deeply integrated into AI development workflows that it functions almost as invisible infrastructure. Nearly every significant deep learning framework—PyTorch, TensorFlow, JAX—has native CUDA support. Model creators target CUDA as a primary platform. Researchers publish CUDA implementations. This ecosystem creates enormous switching costs.

Groq has been building its own software ecosystem, but starting from zero against an entrenched competitor is challenging. The company has released Groq Flow, its compiler and optimization framework, along with model implementations for popular architectures. However, third-party developers haven't rallied around the platform with the same enthusiasm they've shown for CUDA.

This challenge is not insurmountable, but it remains significant. A developer considering whether to optimize their model for Groq hardware must weigh the performance benefits against the development cost and the limitation of reaching a smaller deployment audience. Many developers make the rational choice to continue with CUDA, accepting the latency penalties rather than bearing the optimization burden.

For Groq, resolving this software challenge is essential. The hardware is genuinely innovative, but hardware alone never dominates computing. The companies that win in infrastructure compete on total ecosystem value: not just raw performance but the ease of development, the breadth of tools, and the size of the community.

Nvidia's Counterattack: Integration and Ecosystem Dominance

Recognizing the Inference Opportunity

Nvidia's response to the inference optimization wave has been characteristically strategic. The company recognized early that inference was becoming increasingly important to enterprise customers and that specialized inference hardware might capture significant value. Rather than view Groq and similar competitors as existential threats, Nvidia has taken multiple approaches simultaneously.

First, the company has invested in software innovations specifically for inference optimization. Nvidia's TensorRT is a deep learning inference optimization and deployment framework that allows enterprises to run models more efficiently across Nvidia's existing hardware. TensorRT includes techniques like quantization (reducing the precision of model weights and activations), layer fusion (combining multiple operations into single optimized operations), and kernel optimization (writing custom code for specific operations).

These software techniques can achieve 10-100x speedups in inference performance compared to unoptimized model execution. For many enterprise customers, software optimization on existing GPU infrastructure is more practical than replacing hardware entirely. The investment in CUDA training and GPU deployment is too substantial to abandon lightly.

Second, Nvidia has continued to innovate on the GPU side, releasing new hardware generations with architectural improvements specifically targeting inference workloads. Each new GPU architecture iteration includes features that improve inference characteristics: higher memory bandwidth relative to compute capacity, improved cache hierarchies, new specialized instructions for common inference operations.

Third, Nvidia has been acquiring companies with specialized inference expertise. These acquisitions provide the company with intellectual property, engineering talent, and architectural insights that can be integrated into future Nvidia platforms. Each acquisition represents a signal that Nvidia takes inference specialization seriously and is willing to invest in maintaining its dominance.

The Case for Hardware Diversity and Specialization

Instead of fighting specialization, Nvidia has begun embracing it in a controlled way. The company has made strategic investments in various specialized AI processor startups and has hinted at potential partnerships or integrations. If Nvidia could acquire Groq's technology or integrate Groq-like capabilities into its platforms, the company would solve multiple strategic challenges simultaneously.

First, it would internalize a competitive technology before it achieved broader adoption. Acquiring innovative startups before they become large competitors is a proven strategy. Nvidia has a history of such acquisitions, using them to expand capabilities and eliminate threats.

Second, integrating Groq-like inference capabilities into Nvidia's ecosystem would create a comprehensive platform: GPUs optimized for training and general-purpose compute, specialized inference processors for latency-sensitive applications, and CUDA as the unifying software framework. This would be a formidable moat because customers could standardize on Nvidia hardware across their entire AI pipeline.

Third, it would preserve Nvidia's position as the foundational AI infrastructure company. The narrative of Nvidia's dominance is built on the idea that every major AI development initiative depends on Nvidia hardware. If inference moves to non-Nvidia hardware, that narrative becomes more difficult to sustain. By controlling inference options, Nvidia preserves its centrality.

Furthermore, Nvidia's existing distribution advantages—deep relationships with cloud providers, installed base across data centers, extensive sales operations—would accelerate Groq-like technology adoption. A Groq innovation that takes years to penetrate the market might reach widespread adoption in months if distributed through Nvidia's channels.

Rubin Architecture and the Future of Nvidia Infrastructure

Nvidia's Rubin architecture, released in detail in late 2024, signals the company's strategic direction for the next era of AI infrastructure. While Rubin is positioned as a next-generation GPU architecture, it incorporates lessons from specialized inference hardware competition.

Rubin includes architectural features designed specifically for efficient inference: better support for smaller batch sizes, improved token throughput characteristics, and new instructions tailored for quantized model inference. These features wouldn't exist if companies like Groq hadn't demonstrated their value. Nvidia is systematically incorporating insights from the specialized hardware wave into its general-purpose GPUs.

Moreover, Rubin is designed to work in concert with advanced networking technology, particularly Nvidia's NVLink and newer interconnect standards. This focus on system-level optimization—not just individual processors but entire clusters working in concert—is another area where Nvidia's ecosystem dominance provides advantage. Groq might have superior single-processor inference performance, but Nvidia's ability to orchestrate multiple systems into coherent inference clusters is unmatched.

The Rubin strategy represents a subtle but important insight: Nvidia doesn't need to match Groq's specialized inference performance exactly. Instead, Nvidia needs to get close enough on inference while maintaining massive advantages in training, deployment flexibility, and ecosystem breadth. Most enterprises want a single platform they can use for training, general-purpose compute, and inference. Specialized hardware excels on specific tasks but creates operational complexity.

Nvidia is positioned to offer "good enough" inference performance across general-purpose hardware, while also offering specialized inference options for specific use cases. This flexibility is itself valuable.

The LPU shows a significantly higher efficiency score for language model inference compared to traditional GPUs and CPUs. Estimated data based on architectural optimizations.

The Deep Seek Effect: Architectural Efficiency as the Next Frontier

How Inference-Time Scaling Changed the Game

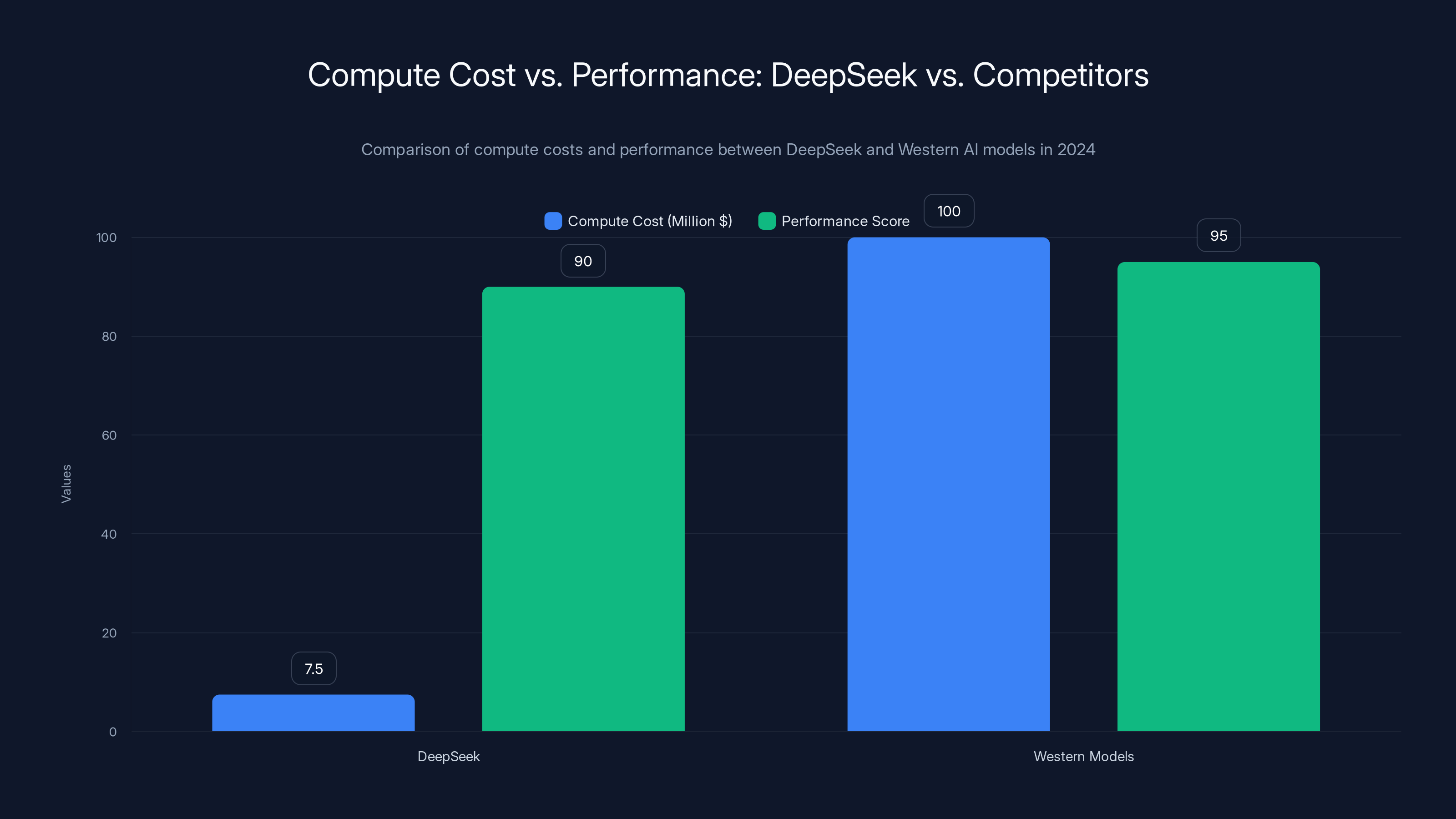

The latter half of 2024 witnessed a significant shift in AI development philosophy. Deep Seek, a Chinese AI company, released models that challenged fundamental assumptions about scaling and compute efficiency. Despite training on what appeared to be a much smaller computational budget than competitors—estimates ranged from

This was shocking to the industry because it contradicted the prevailing narrative that compute scale was directly proportional to capability. If you could achieve world-class performance with 5-10x less compute, what did that say about the investments made by companies like Open AI and Anthropic?

The answer lies in two key innovations Deep Seek employed. First, the company used mixture-of-experts architecture more aggressively than prior models. This architecture, which Nvidia itself has championed in recent announcements, allows models to maintain the parameters of a very large model while only activating a subset of parameters for each inference pass. This provides capability benefits without the full computational cost of traditional dense models.

Second, and most importantly for our discussion, Deep Seek invested heavily in inference-time optimization. The company recognized that if you could use more compute during inference—allowing the model to think longer and reason more carefully—you could achieve better performance without scaling training to absurd levels. This inverts the traditional deep learning paradigm where all the compute is invested upfront in training, and inference is meant to be as cheap as possible.

Inference-time scaling involves training models to use techniques like chain-of-thought reasoning, self-verification, and iterative refinement during inference. The model generates intermediate reasoning tokens that are never shown to users but help the model verify its own work and correct errors. This approach was popularized by Open AI's o 1 model, but Deep Seek demonstrated that with proper architecture, you could achieve similar benefits more efficiently.

The Mathematics of Inference-Time Compute Trade-offs

The economic implications of inference-time compute are profound and reshape infrastructure spending calculations. Traditional model scaling follows a relationship where performance improves logarithmically with additional compute. To double your model's capability, you might need 5-10x additional training compute. The curve flattens—each increment of additional compute produces smaller improvements.

Inference-time scaling follows a different curve. By allowing the model to reason for longer—generating 5x or 10x more internal tokens—you can achieve performance improvements that rival what scaling would provide, but with computation happening during inference rather than during training.

For infrastructure providers and enterprises, this creates a fundamental trade-off. Train a model smaller but accept higher inference costs, or train a model larger but keep inference computationally cheap. The optimal balance depends on usage patterns.

For a model that will be deployed millions of times (like a chatbot that processes millions of user requests), you optimize for cheap inference even if it means higher training costs. Every microsecond of inference time, multiplied by millions of requests, becomes expensive. For a model that will be deployed infrequently or in batch processing (like scientific computing applications), you might optimize for cheap computation overall, even if individual inference passes are expensive.

This trade-off has enormous implications for Groq and other inference-optimized hardware companies. If inference-time compute becomes dominant—if reasoning models that use 10x or 100x more tokens during inference become standard—then the value proposition for specialized inference hardware increases substantially. The latency and efficiency improvements become more valuable the more compute happens during inference.

Nvidia's hardware works for inference-time compute too, but Groq's architecture, with its focus on token throughput and low latency, may have inherent advantages in this regime. The company has been unusually visible in promoting inference-time compute in its marketing, perhaps recognizing that this trend plays to its architectural strengths.

Implications for Model Architecture Going Forward

The success of Deep Seek and the emergence of inference-time scaling as a viable strategy is forcing the AI development community to rethink model architecture fundamentally. We may be moving away from the paradigm of "scale everything maximally during training" toward a more nuanced approach where scaling, distillation, pruning, and inference-time compute are balanced against each other.

This has implications for which hardware platforms succeed. Companies optimizing for inference-time compute want hardware that can throughput enormous numbers of tokens quickly. Companies optimizing for training still prefer traditional GPUs with their massive parallel capabilities. A company that succeeds across both domains—providing excellent training infrastructure and excellent inference-time compute infrastructure—gains substantial advantage.

Nvidia's advantage here is again ecosystem breadth. The company can provide excellent training hardware and ecosystem, then offer multiple inference options: traditional GPU inference, specialized inference hardware, and eventually, inference chips optimized for reasoning workloads.

Enterprise AI Deployment: Where Hardware Decisions Matter Most

The Real-Time Reasoning Problem in Enterprise AI Agents

Enterprise AI agents represent the most demanding use case for modern AI infrastructure. Unlike chatbots that answer questions or recommendation systems that suggest products, enterprise AI agents must perform actual work: booking resources, executing transactions, modifying systems, and making decisions that have real financial or operational consequences.

These agents require reasoning because the stakes are high. A recommendation engine that suggests suboptimal products causes minor user frustration. An AI agent that books the wrong hotel causes significant problems. The agent must generate internal reasoning tokens, verify its own work, explore alternatives, and double-check before committing to an action.

Consider a concrete example: an AI agent responsible for optimizing cloud infrastructure spending. The agent receives an instruction: "Reduce our monthly AWS spending by 10% without degrading performance." To accomplish this, the agent must:

- Query cloud infrastructure APIs to understand current deployments (500 tokens)

- Analyze usage patterns and identify inefficiencies (1,000 tokens)

- Model the impact of different optimization strategies (2,000 tokens)

- Verify that optimizations won't breach SLA requirements (1,000 tokens)

- Generate detailed recommendations with implementation steps (500 tokens)

- Create a human-readable explanation and risk assessment (1,000 tokens)

The total internal reasoning is 6,000 tokens before a single recommendation is provided to humans. On GPU infrastructure, this might take 20-30 seconds. That's not terrible for an asynchronous operation, but for interactive use cases or for agents running continuously throughout the day processing dozens of tasks, it becomes expensive and slow.

On Groq infrastructure, the same reasoning completes in 4-6 seconds. Across hundreds of agents processing thousands of tasks daily, this difference compounds into enormous time and cost savings. More subtly, the faster inference makes the agent feel more responsive and capable. Instead of waiting for the system to think, humans interact with a system that returns results quickly.

The Cost Economics of Enterprise Inference

Enterprise cloud spending on AI inference is rapidly becoming a major cost category. A typical large enterprise might process millions of inference requests daily across various applications: chatbots, recommendation systems, content generation, decision support systems, and increasingly, autonomous agents.

Inference costs depend on multiple factors: the size of the model, the latency required, the total number of requests, and the cost of compute resources. A rough calculation for a typical scenario:

- Model: 70 billion parameter language model

- Requests: 1 million daily

- Average request: 500 input tokens + 500 output tokens

- Infrastructure cost: 1.00 per million tokens on cloud GPU infrastructure

- Monthly cost: 1 million requests × 1,000 tokens × 750/day = $22,500/month

If Groq infrastructure achieves 4x higher throughput per unit of hardware, you could reduce this to approximately

Beyond raw cost, Groq infrastructure also enables new use cases. Inference workloads that were previously economically infeasible—requiring too many reasoning tokens, too frequent execution, or too much latency-sensitive processing—become viable. An enterprise might reserve 30% of its inference compute for exploratory or novel use cases precisely because the cost has dropped enough to justify experimentation.

However, these economics only materialize if enterprises can actually execute on Groq infrastructure. They need to optimize models for Groq's architecture, integrate with their existing systems, develop operational expertise, and manage multiple hardware vendors instead of consolidating on Nvidia. The software and operational overhead can be substantial.

The Role of Model Quantization and Optimization

Before investing in specialized inference hardware, many enterprises are exploring quantization and optimization techniques that improve inference efficiency on existing GPU infrastructure. These approaches, combined with software optimizations like Nvidia's TensorRT, can achieve 5-10x improvements in inference efficiency without changing hardware.

Quantization involves reducing the precision of model parameters and activations. A typical model uses 32-bit floating-point numbers (float 32) to represent weights and activations. By using 8-bit integers (int 8) or even 4-bit integers, you can reduce memory requirements and computational cost while maintaining acceptable accuracy. Many modern models can be quantized with minimal performance loss. A 70B parameter model in float 32 requires 280GB of memory; the same model quantized to int 8 requires 70GB.

For many enterprises, quantization on existing GPU infrastructure is the optimal choice. The implementation is straightforward, the ecosystem support is mature, and switching to new hardware isn't necessary. Quantization trades minimal accuracy loss for substantial efficiency gains.

However, quantization has limits. Aggressive quantization (4-bit or lower) can degrade model quality. Some operations don't quantize well. Beyond certain thresholds, you hit diminishing returns, and the only way to further improve efficiency is through hardware specialization.

For enterprises that have pushed quantization and software optimization to their limits, specialized inference hardware becomes attractive. Groq hardware is particularly effective for quantized models because the deterministic execution and specialized instruction set provide benefits regardless of precision. In fact, Groq's architecture may be even more effective with quantized models, because the reduced data size means more of the performance-critical memory bandwidth is available for throughput.

Estimated data shows distinct technological eras, each marked by a paradigm shift leading to exponential growth within that era. The transition from CPUs to GPUs in the 2010s exemplifies this pattern.

The Acquisition Speculation: Strategic Value of Specialized Hardware

Why Nvidia Might Acquire Groq (Or Something Like It)

Industry speculation about potential Nvidia acquisition of Groq has been pervasive. While such an acquisition hasn't materialized as of 2025, the strategic logic is compelling. Here's why Nvidia might seriously consider such a move:

First, acquisition provides access to Groq's intellectual property without the time required to develop equivalent technology in-house. Groq spent a decade developing its LPU architecture and software stack. Nvidia would need years to build equivalent capabilities. Acquisition accelerates Nvidia's timeline to offering competitive inference-specialized hardware.

Second, acquisition eliminates a competitive threat before it achieves broader market penetration. Currently, Groq has meaningful adoption but remains a niche player compared to Nvidia. As inference optimization becomes more important and as enterprises seek alternatives to Nvidia's high pricing, Groq adoption could accelerate. Acquiring Groq prevents this scenario.

Third, acquisition provides access to Groq's engineering talent. The company has attracted exceptional engineers specifically focused on inference optimization. These engineers represent institutional knowledge about the problem space that would take Nvidia years to develop independently.

Fourth, acquisition allows Nvidia to offer a complete inference solution to customers. Nvidia could position Groq LPUs as the specialized inference solution within its ecosystem, maintaining hardware diversity while keeping software unified around CUDA and Nvidia's development frameworks. This is more attractive to enterprises than fragmentary solutions from multiple vendors.

Fifth, acquisition solves Groq's software ecosystem problem. Groq's hardware is genuinely innovative but has struggled with software ecosystem adoption. Under Nvidia ownership, Groq's compiler and frameworks would receive resources and promotion that could significantly expand adoption. Nvidia's developer relations organization could drive much faster ecosystem growth than Groq could achieve independently.

Why Groq Might Resist (Or Alternatively, Accept) Acquisition

For Groq's founders and early investors, acquisition at a substantial valuation represents a successful outcome. The company raised capital at various valuations, and an acquisition at a premium would generate significant returns. However, acquisition also means loss of independence and the potential dissolution of the company's vision if Nvidia decides to shelve the technology or redirect it.

Groq's leadership has repeatedly emphasized their commitment to being an independent company focused specifically on inference optimization. This public commitment may be a negotiating tactic or genuine conviction. If genuine, it reflects a belief that Groq can succeed as an independent company despite facing competition from an entrenched, much larger Nvidia.

This belief could be justified. Groq doesn't need to dominate the entire inference market to succeed. It only needs to capture enough of the inference workload that's sufficiently latency or throughput sensitive to justify specialized hardware. There's undoubtedly a significant market segment where Groq's value proposition is compelling: large-scale language model deployment, real-time AI agents, inference-time compute applications, and cost-sensitive, high-volume inference operations.

Moreover, Groq faces different acquisition pressures than a general-purpose chip company might. Google, Meta, and other large tech companies with massive AI inference workloads might be interested in acquiring Groq to optimize their internal operations. Such an acquisition wouldn't eliminate Groq as a commercial product; it would simply give one company a technological advantage. This creates a countervailing pressure against Nvidia acquisition—if Nvidia doesn't acquire Groq, a competitor might.

So while Nvidia acquisition remains speculative, the strategic logic is sound. For Groq, the company must decide whether to pursue independence (accepting the burden of competing against Nvidia) or seek acquisition to a company that will maximize its technology's impact while providing resources for ecosystem development.

Open-Source Models and Hardware Differentiation: The Complex Relationship

How Open-Source Models Change Hardware Competition

The emergence of high-quality open-source models—particularly Deep Seek, Llama, and Mistral—has fundamentally changed the economics of the AI infrastructure market. For the first time in the generative AI era, companies can deploy competitive models without paying premium prices to Open AI or Anthropic. This availability of high-quality models as open-source democratizes AI development but also changes the hardware competition.

When only proprietary models existed, customers were largely locked into the companies providing those models. You wanted GPT-4 capability? You went to Open AI on Azure, which meant you used Nvidia H100 GPUs in Microsoft's data centers. You had limited choice about hardware. Hardware vendors competed for the favor of model creators, knowing that whoever the model creators standardized on would capture the inference workload.

With open-source models, the relationship inverts. Model training remains expensive and requires significant compute, but once trained, models are available to deploy anywhere. An enterprise can now ask: "Given this model, what's the most cost-effective and performant way to deploy it?"

This question directly favors specialized inference hardware. If you're deploying an open-source Llama model or Mistral model on commodity hardware you're free to choose, you might optimize for cost and latency by using Groq. With proprietary models, you were locked into whatever the model creator recommended.

This is potentially transformative for Groq's competitive position. The company could become the natural choice for enterprises deploying open-source models at scale. "Deploy open-source models on Groq for best cost and latency" becomes a compelling marketing message.

Nvidia, recognizing this risk, has responded by improving its software optimizations for popular open-source models. Nvidia's TensorRT has been updated with specific optimizations for Llama, Mistral, and other open-source models. This allows enterprises to achieve better inference efficiency on Nvidia hardware without switching vendors.

The Role of Model Distillation and Specialization

As open-source models proliferate, we're seeing the emergence of smaller, specialized models optimized for specific tasks. Instead of deploying a single 70B parameter general-purpose model, enterprises are increasingly deploying multiple smaller models, each specialized for a specific task: one for customer support, one for content generation, one for analysis, etc.

This shift toward model specialization and distillation creates interesting hardware dynamics. Smaller models can be deployed on less powerful hardware, reducing infrastructure costs. Specialized models can sometimes be more efficient to run than general-purpose models because they've eliminated capabilities irrelevant to their specific domain.

For hardware vendors, smaller models create challenges. The economies of scale that apply to deploying a single large model across many requests don't apply as strongly when deploying dozens of smaller models. But they also create opportunities—inference hardware that can efficiently handle smaller batch sizes and can be deployed in distributed, flexible configurations becomes more valuable.

Groq's architecture, with its focus on small-batch inference efficiency, may be particularly well-suited to this emerging pattern of model specialization. A single Groq system could efficiently run multiple smaller models, switching between them based on incoming requests. Traditional GPUs, optimized for large-batch throughput, are less efficient in this scenario.

DeepSeek achieved competitive performance with significantly lower compute costs compared to Western models, highlighting the efficiency of their architectural innovations. Estimated data.

The Energy and Sustainability Dimension: Environmental Impact of AI Inference

Computing Efficiency as Environmental Responsibility

As AI systems scale to enterprise and societal scale, the environmental impact of training and deploying these systems has become increasingly visible. A single training run of a frontier model can consume as much electricity as a small country does in days. The cumulative environmental impact of AI inference across millions of requests daily is staggering.

Fortunately, inference optimization directly addresses this environmental challenge. Hardware and software optimizations that reduce inference latency and computational cost also reduce energy consumption. This creates alignment between economic optimization and environmental responsibility.

Groq's efficiency gains—achieving 4-10x higher throughput per watt compared to GPUs on inference workloads—translate directly to reduced energy consumption. An enterprise deploying models on Groq instead of GPU infrastructure consumes 75-90% less electricity to achieve the same inference throughput.

For large-scale deployments processing billions of inference requests annually, this compounds into substantial energy savings. An enterprise processing 10 billion tokens monthly on GPU infrastructure might consume 10 megawatt-hours of electricity. Migrating to Groq might reduce this to 2-3 megawatt-hours. Over a year, that's the equivalent of the annual electricity consumption of hundreds of homes, and the corresponding reduction in carbon emissions.

Nvidia, recognizing the importance of this narrative, has emphasized the energy efficiency of its newer GPU architectures and its optimization software. TensorRT and other software tools that reduce inference latency also reduce energy consumption. Nvidia's positioning emphasizes that deploying on Nvidia hardware with software optimization can achieve near-specialized-hardware efficiency while maintaining flexibility.

For enterprises with serious sustainability commitments, inference optimization becomes not just an economic decision but a moral imperative. Choosing the most efficient infrastructure for AI deployment is consistent with broader environmental responsibility goals.

The Roadmap for Future Energy Efficiency

Both Nvidia and Groq, along with emerging competitors, are investing in future hardware generations specifically designed to improve energy efficiency. These investments reflect a recognition that energy will be a binding constraint on future AI scaling.

Nvidia's roadmap includes technologies designed to reduce power consumption: improved memory hierarchies that reduce data movement (which consumes energy), specialized low-power modes for inference workloads, and integration of different processing elements optimized for different computational patterns.

Groq, with its fundamental focus on inference efficiency, is inherently pursuing energy efficiency. The company's architecture, by eliminating memory bandwidth bottlenecks, naturally reduces energy consumption compared to approaches that rely on massive data movement.

Other emerging competitors are taking different approaches. Some startups are exploring custom chip designs specifically for quantized model inference, trading flexibility for extreme efficiency. Others are pursuing photonic computing approaches that might, in theory, consume dramatically less energy than traditional electronic processors.

For enterprises making long-term infrastructure decisions, energy efficiency should be a primary consideration. The most cost-effective infrastructure today might be dramatically more expensive in five years if energy prices rise. Choosing hardware with inherent efficiency characteristics provides protection against future uncertainty.

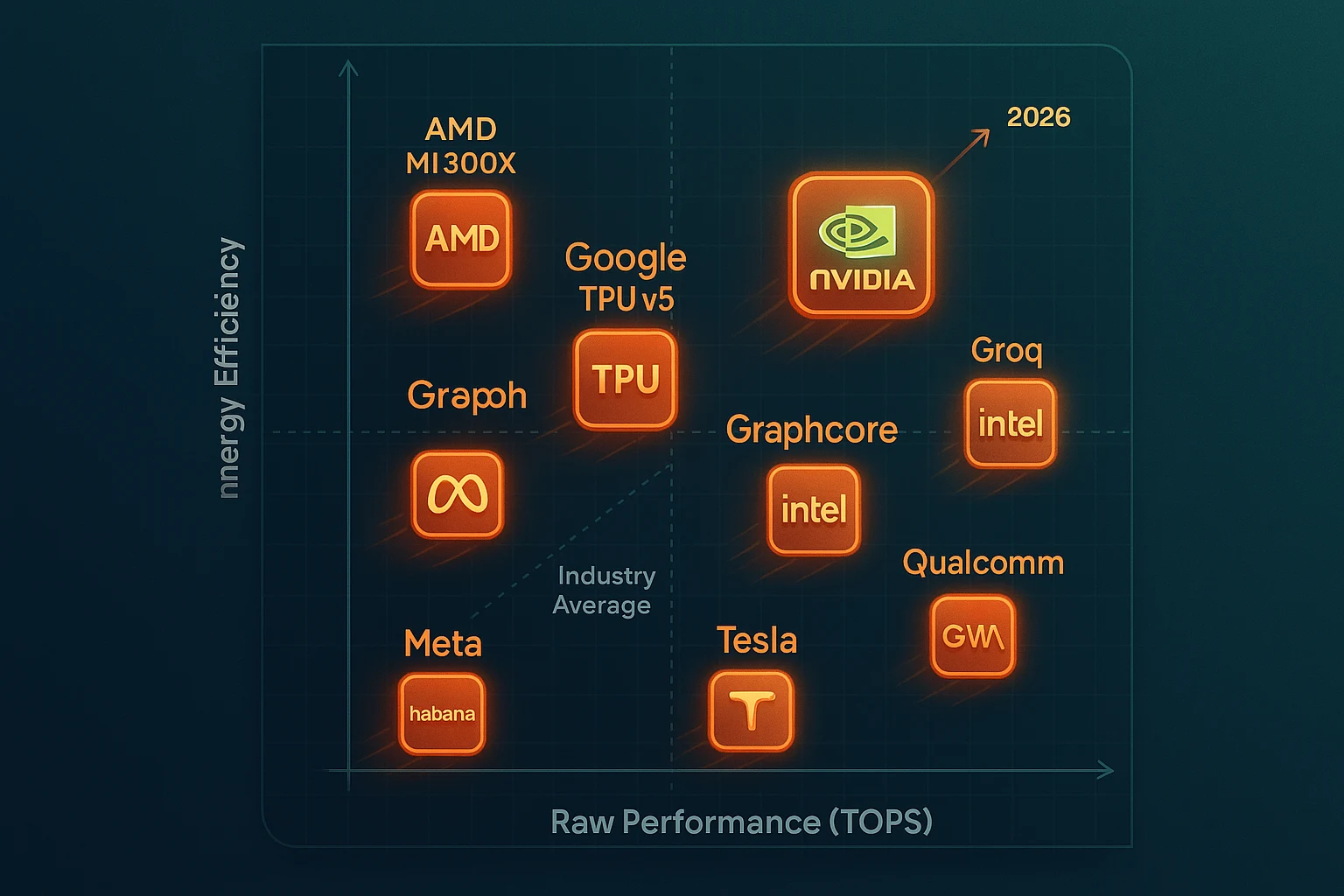

The Competitive Landscape: Beyond Groq and Nvidia

Emerging Specialized Hardware Companies

Groq is the most prominent pure-play inference hardware company, but it's far from the only one. A wave of startups is developing alternative hardware approaches to AI inference, each offering different trade-offs and targeting specific use cases.

Cerebras, a company founded by veterans of advanced semiconductor development, is pursuing a completely different approach: building enormous chips with hundreds of billions of transistors containing all the memory needed for model weights. This eliminates the memory bandwidth bottleneck entirely by integrating memory and compute on the same chip. Cerebras hardware shows remarkable efficiency for certain inference workloads but faces challenges related to chip cost, yield, and deployment flexibility.

Graphcore, a UK-based semiconductor company, is developing intelligence processing units (IPUs) designed for parallel computing. While originally positioned for training, IPUs have found traction in inference applications where their support for irregular computation patterns provides advantages.

Custom AI Chips (formerly called Habana, now owned by Intel) is developing purpose-built AI accelerators combining inference and training capabilities. This company is attempting to position itself as an alternative to Nvidia across both domains.

Multiple Chinese companies are developing competing inference hardware, focused on the Asian market where pricing pressure and alternative architectures are particularly important.

This competitive landscape is healthy for the broader ecosystem. Multiple viable options prevent any single vendor from achieving monopolistic power. Enterprises can choose infrastructure that best matches their specific requirements rather than being forced to standardize on a single platform.

The Role of FPGA and Custom Solutions

For enterprises with very specific inference requirements, field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) and custom silicon represent another option. FPGAs allow hardware-level customization for specific models and workloads, achieving efficiency that general-purpose hardware can't match.

Amazon's Trainium and Inferentia chips, for example, are custom silicon designed specifically for machine learning workloads. These chips are deeply integrated with Amazon's cloud infrastructure and optimized for their specific customer base.

Google's TPUs (Tensor Processing Units) similarly represent custom silicon optimized for Google's internal AI workloads. Google has recently made TPU access available to external customers, creating competition against Nvidia in the cloud inference space.

For enterprises considering custom solutions, the trade-off is clear: significant engineering cost and inflexibility in exchange for optimized performance. This is only viable for companies with massive-scale inference workloads where the development cost can be amortized across enormous deployment.

Cloud Provider Differentiation Through Hardware

Major cloud providers—AWS, Google Cloud, Azure—are increasingly differentiating through specialized AI hardware offerings. Rather than offering homogeneous GPU infrastructure, cloud providers are now offering multiple hardware options and optimizing their software stacks for each option.

AWS promotes its custom Trainium and Inferentia chips. Google emphasizes its TPUs. Azure highlights Nvidia's latest GPUs and also offers custom Maia chips being developed in collaboration with partners. This diversification allows cloud providers to offer cost-optimized solutions for different workloads.

For enterprises, this cloud provider competition is advantageous. Instead of being forced to choose a single hardware platform, enterprises can use different cloud providers for different workloads based on which provides the best price and performance for their specific requirements.

Cloud provider differentiation on hardware also accelerates innovation across the industry. Cloud providers are willing to invest in custom silicon development because controlling the underlying hardware provides enormous margins and competitive advantage. This investment accelerates the pace of innovation in AI hardware.

Groq infrastructure significantly reduces AI agent reasoning time from 25 seconds on GPU to just 5 seconds, enhancing efficiency for enterprise applications. Estimated data based on typical performance.

Real-Time AI Agents: The Ultimate Proving Ground for Infrastructure Innovation

The Emergence of Agentic Systems and Their Computational Requirements

The most advanced AI applications being deployed in 2025 are increasingly agentic in nature. Rather than simply answering questions or generating content, these systems autonomously pursue objectives: managing cloud infrastructure, conducting research, analyzing documents, making decisions, and executing transactions.

Agentic systems generate computational requirements that single inference requests don't capture. An agent tasked with optimizing a portfolio might run continuous analysis, generating thousands of internal reasoning tokens as it evaluates different strategies. An agent managing a customer support queue might handle multiple conversations in parallel, each requiring extended reasoning.

These workloads stress-test infrastructure in ways that traditional language model inference benchmarks don't. Performance matters not just for individual requests but for the ability to handle many concurrent agents, each with extended reasoning requirements, while maintaining responsiveness.

Groq hardware shows particular strength in these agentic workloads. The low latency means agents feel responsive. The high token throughput means extended reasoning happens quickly. The cost per token means running many agents concurrently is economically viable.

Nvidia hardware can handle agentic workloads, but the infrastructure must be carefully designed. Proper batching, memory management, and model quantization become essential. This requires more sophisticated deployment engineering than traditional inference workloads.

Comparing Agent Performance Across Infrastructure

A concrete comparison helps illustrate the differences. Consider an AI agent managing infrastructure optimization, running continuously and processing analysis requests as they arrive:

GPU Infrastructure (Nvidia):

- Average inference latency: 5-10 seconds per response

- Maximum concurrent agents: 50-100 (depending on GPU configuration)

- Cost per agent per day: $10-20

- Agent responsiveness: Acceptable for async operations, slow for interactive use

Groq Infrastructure:

- Average inference latency: 1-2 seconds per response

- Maximum concurrent agents: 200-400 (on equivalent hardware cost basis)

- Cost per agent per day: $2-5

- Agent responsiveness: Excellent for interactive and real-time use

Custom GPU Optimization (with TensorRT, quantization):

- Average inference latency: 3-5 seconds per response

- Maximum concurrent agents: 100-200

- Cost per agent per day: $5-10

- Agent responsiveness: Good for most use cases

These numbers vary significantly based on model size, reasoning depth, and agent implementation, but they illustrate the fundamental trade-offs. Groq provides better latency and cost at the expense of ecosystem breadth. Optimized GPUs provide good balance. Custom hardware provides maximum optimization at the expense of development cost.

The Business Logic of Agent Deployment Economics

The economics of agent deployment depend heavily on how agents are used. For agents running continuously and independently (optimizing systems, monitoring, making autonomous decisions), the cost per agent and responsiveness matter greatly. An enterprise deploying 1,000 agents making cost-sensitive optimizations would strongly prefer infrastructure that reduces per-agent costs from

For agents that augment human interaction (providing advice to a human decision-maker, gathering information for analysis), latency matters more than pure cost. A human waiting 10 seconds for an agent response (while seeing streaming results) is acceptable; the human waiting 60 seconds is frustrating. In these cases, infrastructure providing latency below human tolerance thresholds is valuable.

For agents in critical control loops (making high-frequency trading decisions, controlling manufacturing equipment, managing power grids), both latency and reliability are paramount. Cost becomes secondary. For these applications, custom silicon designed specifically for the use case often makes sense.

Enterprise IT leaders must understand their specific agent deployment patterns to choose appropriate infrastructure. A company deploying thousands of cost-monitoring agents on Groq may make sense. A company deploying a handful of critical agents on custom hardware may also make sense. Choosing infrastructure without understanding the workload is a common mistake.

Implications for Enterprise AI Strategy: Making the Right Hardware Choice

Evaluating the Make-Or-Buy Decision for AI Infrastructure

Enterprise IT leaders face a fundamental decision: should they build sophisticated in-house AI infrastructure optimized for their specific needs, or should they rely on cloud providers and specialized vendors?

Building in-house requires significant expertise: knowledge of model training, quantization, deployment optimization, and ongoing operations. It also requires accepting the burden of managing multiple hardware generations, keeping up with rapid innovation, and handling supply chain challenges.

The advantage of in-house infrastructure is control. An enterprise can optimize specifically for its workloads, pricing models, and operational constraints. A company deploying thousands of agents might find that custom infrastructure, even after development costs, is more economical than cloud or specialized vendor offerings.

For most enterprises, cloud deployment with specialized cloud providers remains the more practical option. Cloud providers handle infrastructure management, provide diverse hardware options, and absorb the risk of hardware obsolescence. The enterprise pays for this convenience through higher unit costs.

For enterprises with truly massive-scale AI operations—companies deploying billions of inference requests daily—in-house optimization becomes worthwhile. Google, Meta, and similar companies invest billions in custom AI infrastructure because the scale justifies the investment.

Framework for Infrastructure Selection

Choosing between Nvidia, Groq, cloud provider native hardware, and custom solutions requires systematic evaluation:

1. Workload Characterization:

- What's the inference volume? (millions vs. billions of requests daily)

- What's the token throughput requirement? (millions vs. trillions of tokens monthly)

- What's the latency requirement? (seconds, milliseconds, real-time)

- What models will be deployed? (proprietary vs. open-source, trained vs. fine-tuned)

- What's the reasoning depth? (single-pass inference vs. extended chains of thought)

2. Cost Analysis:

- What's the cost per inference on each platform? (including amortized hardware cost, power, and operations)

- What's the total cost of ownership including engineering, management, and upgrades?

- How do costs scale with volume?

3. Operational Complexity:

- How much engineering expertise is required to operate each option?

- What's the risk of vendor lock-in?

- How do platforms handle hardware evolution and upgrades?

- What's the time to deploy new capabilities?

4. Strategic Alignment:

- How does each option align with broader IT infrastructure strategy?

- Does the company prefer vendor consolidation or diversity?

- How do decisions today constrain options in the future?

- What's the risk that technology choices become obsolete?

5. Competitive Advantage:

- Does AI infrastructure provide competitive advantage specific to this company's business?

- Is this infrastructure a core capability or a commodity input?

- Can competitors replicate or exceed capabilities achieved through infrastructure investment?

Answering these questions systematically leads to different conclusions for different enterprises. A company deploying traditional language model inference at moderate scale might find cloud GPUs entirely adequate. A company deploying reasoning agents at massive scale might find Groq infrastructure compelling. A company with unique model architectures might find custom silicon justified.

Avoiding Common Infrastructure Mistakes

Enterprise IT leaders frequently make predictable mistakes when evaluating AI infrastructure:

1. Optimizing for Yesterday's Workloads: Infrastructure decisions based on current workloads often fail because workloads evolve. A decision to standardize on GPU infrastructure for traditional inference might look foolish when the company shifts to reasoning agents requiring different hardware characteristics.

2. Ignoring Software Ecosystem: Hardware performance matters, but software matters more. A technically superior processor with weak software support often loses to less capable hardware with excellent tooling and ecosystem.

3. Underestimating Operational Complexity: Deploying specialized hardware requires expertise in compiler optimization, model quantization, and system integration. Underestimating these requirements leads to failed deployments.

4. Failing to Account for Vendor Dynamics: Vendor relationships, product roadmaps, and financial stability matter. Deploying on a vendor with declining market position creates risk.

5. Assuming Scalability is Linear: A solution that works at 100 million tokens monthly might fail completely at 10 billion tokens monthly due to different bottlenecks and constraints. Careful capacity planning is essential.

6. Ignoring the Importance of Flexibility: Locking into a single hardware vendor and architecture constrains future options. Maintaining flexibility to switch vendors or add new hardware options costs extra but provides valuable optionality.

The Next Decade: Trajectory of AI Infrastructure Competition

Predicting the Evolution of the Hardware Landscape

Based on current trajectories, several developments seem likely over the next 5-10 years:

Specialization will increase. We won't consolidate back to a single universal processor type. Instead, we'll see proliferation of specialized hardware: processors optimized for training, inference, reasoning, quantized models, specific model architectures, and specific workload patterns. Enterprises will manage portfolios of hardware rather than standardizing on a single platform.

Software becomes even more important. Hardware innovations provide temporary advantage, but software enables sustained advantage. The company that best optimizes the software ecosystem around its hardware wins. We should expect rapid evolution in frameworks, compilers, and deployment tools.

Open-source models drive standardization. Open-source models create a common target that multiple hardware vendors can optimize for. Unlike proprietary models that prefer specific hardware, open-source models are agnostic about infrastructure. This creates pressure for standardization and opens space for non-Nvidia competitors.

Energy becomes a binding constraint. As AI systems scale, energy cost and availability become limiting factors. Hardware optimized for energy efficiency will gain increasing value. This may favor companies like Groq that optimized for efficiency from inception.

Cloud providers assert differentiation. Rather than commoditizing GPU rental, cloud providers will increasingly deploy custom hardware and exclusive algorithms to differentiate. We'll see increasing fragmentation across cloud providers as each optimizes infrastructure for its specific customer base.

Reasoning and long-horizon thinking drive new requirements. As AI agents become more capable and reason more deeply, the computational patterns will shift again. Hardware optimized for current transformer inference may be suboptimal for future reasoning-intensive workloads. New specialized hardware will emerge to address these patterns.

The Potential for Consolidation and M&A

Over the next few years, we should expect significant mergers and acquisitions in the AI hardware space. Potential scenarios include:

Nvidia acquires Groq (or similar): Nvidia consolidates its position by acquiring specialized hardware competitors. This would be consistent with the company's historical approach to threats—buy rather than compete directly.

Cloud providers acquire AI chip companies: Google, Amazon, or Microsoft might accelerate custom chip development by acquiring existing AI semiconductor companies. These acquisitions would internalize expertise and accelerate product development.

Consolidation among weaker competitors: With dozens of AI hardware startups competing for venture funding and customer adoption, many will fail or be consolidated. We'll likely see 3-5 dominant pure-play inference hardware companies rather than 20+.

Intel or AMD enter the market more aggressively: Intel and AMD, traditional CPU and GPU manufacturers, might make acquisitions or partnerships to establish stronger positions in AI infrastructure. Both companies have AI chip initiatives but have struggled to compete against Nvidia's ecosystem advantage.

For enterprises, consolidation creates both risks and opportunities. Consolidation around a few dominant players provides stability but reduces optionality. On the other hand, it forces enterprises to make strategic choices about hardware standardization.

The Role of International Competition

AI infrastructure has become strategically important to governments and nations. Chinese companies, facing semiconductor export restrictions, are developing alternatives to American hardware. European companies are attempting to build competitive AI infrastructure independent of American vendors.

This geopolitical dimension will likely drive specialization and regional competition. Different regions may standardize on different hardware, creating fragmented markets where a company's hardware choice depends partly on geography and geopolitical alignment.

For multinational enterprises, this creates complexity. Decisions about hardware standardization must account for geographic distribution and geopolitical constraints. A company deploying AI infrastructure globally might be forced to maintain multiple hardware platforms for compliance and political reasons.

Practical Guidance: Implementing Real-Time AI Systems

Step-by-Step Deployment Framework

Enterprises looking to deploy real-time AI systems optimized for latency and efficiency should follow this framework:

Step 1: Define Performance Requirements

- Specify required inference latency (milliseconds range)

- Specify token throughput requirements (tokens per second)

- Identify peak concurrent request loads

- Characterize the distribution of request sizes and complexity

Step 2: Model and Workload Selection

- Evaluate open-source vs. proprietary models

- Consider model size relative to latency requirements

- Plan for model quantization and optimization

- Prototype with candidate models on available infrastructure

Step 3: Infrastructure Evaluation

- Benchmark GPU infrastructure (with and without optimization)

- Evaluate specialized hardware (Groq, Cerebras, etc.)

- Test cloud provider native offerings

- Calculate total cost of ownership for each option

Step 4: Pilot Deployment

- Deploy on chosen platform with realistic workloads

- Monitor performance, cost, and operational characteristics

- Identify bottlenecks and optimization opportunities

- Engage with vendor support for specialized hardware

Step 5: Scale Production Deployment

- Plan capacity based on pilot results

- Implement monitoring and autoscaling

- Establish operational procedures and escalation paths

- Plan for evolution: hardware upgrades, model updates, workload changes

Common Implementation Patterns

Pattern 1: Cloud GPU with Optimization (Most Common)

- Deploy on AWS/GCP/Azure GPU instances

- Use cloud provider optimization (TensorRT on Azure, etc.)

- Implement quantization and batching

- Use managed inference services where available

- Suitable for: Moderate-scale inference, diverse workloads, enterprises prioritizing operational simplicity

Pattern 2: Specialized Hardware for High-Volume Inference

- Deploy Groq or similar for core inference workload

- Use GPUs for training and model optimization

- Implement API gateway to route requests to appropriate hardware

- Suitable for: High-volume inference, cost-sensitive operations, latency-critical applications

Pattern 3: Hybrid Cloud and On-Premises

- Deploy training and optimization on cloud

- Deploy production inference on on-premises hardware

- Use cloud for burst capacity during peaks

- Suitable for: Large enterprises with high inference volume, requiring data locality, cost-optimized for steady-state

Pattern 4: Inference-as-a-Service

- Use managed services (Together.ai, Replicate, etc.) for inference

- Maintain internal model training and optimization

- Suitable for: Companies lacking deep infrastructure expertise, variable or unpredictable inference demand, quick time to market priority

FAQ

What is real-time AI inference and why is it important?

Real-time AI inference refers to generating predictions or responses from AI models with minimal latency—typically measured in milliseconds to seconds rather than seconds to minutes. This capability is crucial for interactive AI applications like chatbots, autonomous agents, and decision-support systems where users expect immediate responses. Real-time inference becomes increasingly important as AI systems move from batch processing to interactive and autonomous applications where latency degradation directly impacts user experience and system capability.

How does Groq's LPU (Language Processing Unit) differ from GPU-based inference?

Groq's LPU is purpose-built for language model inference and differs fundamentally from GPUs in architecture and optimization focus. While GPUs prioritize massive parallelism for throughput, LPUs eliminate memory bandwidth bottlenecks through deterministic execution, custom instruction sets optimized for transformer operations, and memory hierarchies specifically designed for inference data access patterns. In practical terms, LPUs achieve 4-10x higher token throughput and dramatically lower latency than GPUs on inference workloads, though with less flexibility for other computational tasks.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of Nvidia GPUs for AI inference?

Advantages of Nvidia GPUs include a mature software ecosystem (CUDA), broad vendor support across cloud providers, flexibility for both training and inference, and continuous optimization through software improvements. Disadvantages include higher latency and lower efficiency on small-batch inference due to design focus on parallel throughput, higher operational costs for large-scale inference, and memory bandwidth constraints during token generation. Nvidia's advantages are primarily in ecosystem breadth and flexibility; disadvantages are specific to latency-sensitive inference workloads.

What is inference-time compute scaling and how does it affect hardware requirements?

Inference-time compute scaling refers to allowing models to perform extended reasoning during inference—generating many internal thinking tokens before producing final outputs. This approach, popularized by systems like Open AI's o 1, enables better reasoning and accuracy without proportionally larger training compute. For infrastructure, this trend increases the value of hardware optimized for sustained high token throughput at low latency. Traditional GPUs designed for minimal inference become more valuable when inference involves processing 10,000+ tokens per request, a pattern that favors specialized inference hardware like Groq.

How should enterprises choose between GPU, specialized hardware, and cloud inference services?

Enterprise selection should be based on workload characteristics: GPU infrastructure suits moderate-scale, diverse workloads with acceptable latency; specialized hardware (Groq, etc.) suits high-volume, latency-critical, cost-sensitive inference; cloud services suit variable demand or enterprises lacking infrastructure expertise. The decision framework should evaluate total cost of ownership (including engineering and operations), specific latency and throughput requirements, model types being deployed, and strategic preference for vendor consolidation versus diversification.

What role does quantization play in inference optimization?

Quantization reduces the precision of model parameters from 32-bit floating point to 8-bit or 4-bit integers, dramatically reducing memory requirements and computational cost. A typical 70B parameter model quantized from float 32 to int 8 requires 75% less memory and can achieve 5-10x inference speedup with minimal accuracy loss. Quantization is often the first optimization enterprises pursue before considering specialized hardware, as it works with existing infrastructure and requires modest engineering effort compared to hardware migration.

What is the total cost of ownership for Groq versus GPU inference at scale?

At million-token-monthly scale, GPU inference on cloud costs approximately

How does open-source model availability affect hardware competition?

Open-source models (Llama, Mistral, Deep Seek) decouple model capability from any single hardware vendor, allowing enterprises to choose infrastructure purely based on deployment optimization. This fundamentally changes competitive dynamics: rather than being locked into a model creator's recommended infrastructure, enterprises can choose Groq, Nvidia, or cloud provider native hardware based on cost and performance fit. This shift dramatically increases competitive pressure on traditional infrastructure vendors and accelerates adoption of specialized inference hardware.

What future developments should enterprises anticipate in AI infrastructure?

Expect increasing specialization with diverse hardware types optimized for specific workloads rather than universal approaches; continued importance of software optimization and developer tools; energy efficiency becoming a binding constraint on scaling; cloud providers differentiating through custom silicon; continued concentration among competitors through acquisition; and geopolitical fragmentation where different regions standardize on different hardware. Enterprises should plan for portfolio approach to hardware rather than single-vendor standardization.

Conclusion: Navigating the Infrastructure Transition

The AI infrastructure landscape is undergoing a profound shift that will reshape enterprise computing for the next decade. What began as a clear winner-take-all market dominated by Nvidia has evolved into a complex, specialized ecosystem where different hardware platforms optimize for different computational patterns.

The metaphor of the limestone staircase remains apt. The smooth exponential curve of Moore's Law flattened because of physical constraints. The smooth scaling of AI capability faces constraints in compute cost, data availability, energy consumption, and the diminishing returns of pure parameter scaling. These constraints are giving way to a new computational era where architecture matters more than raw speed, where specialization trumps generality, and where the next stepping stone in AI capability comes from reimagining the entire computational approach.