Stellantis $26 Billion EV Writedown: What It Means for Auto Industry [2025]

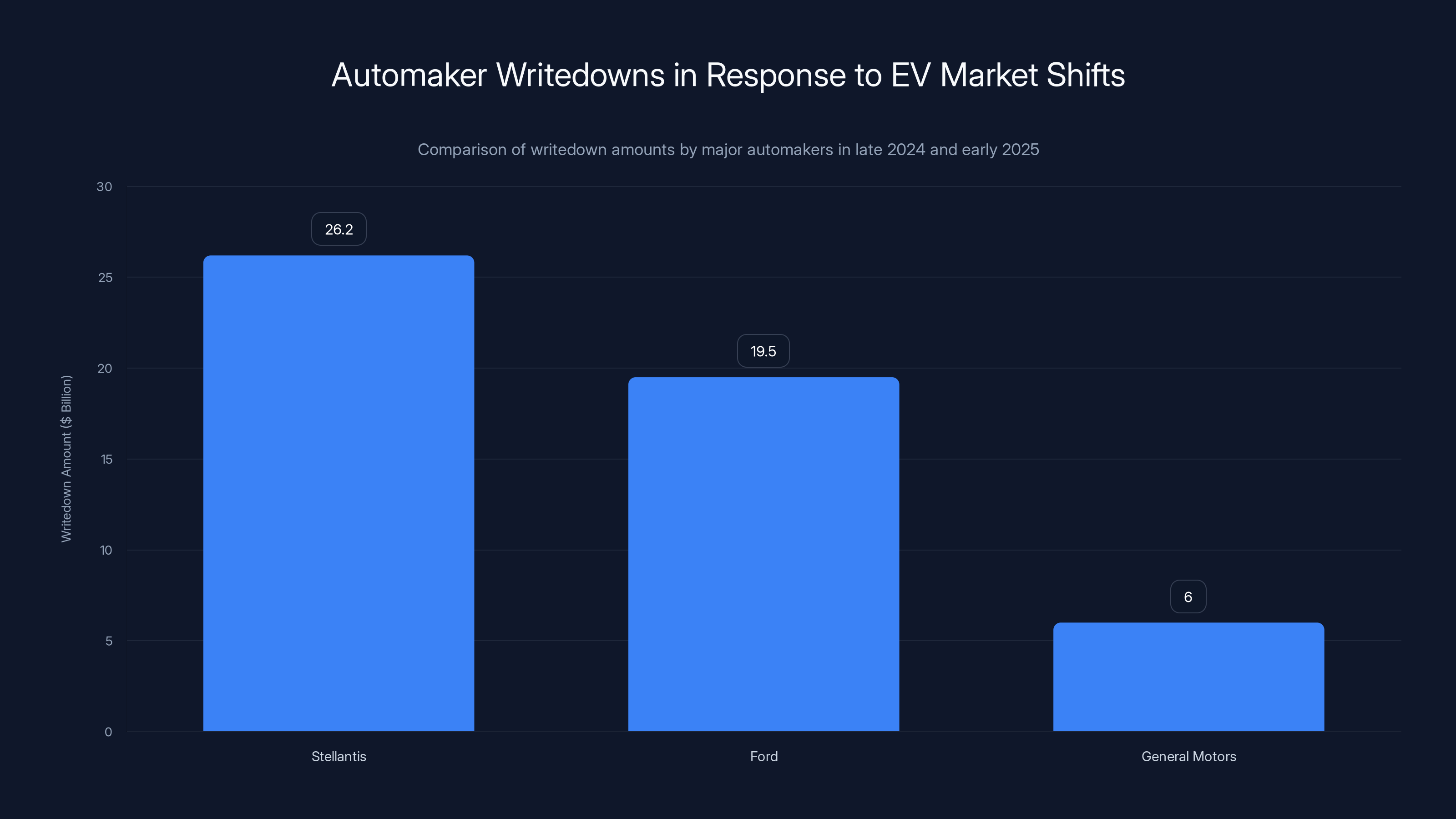

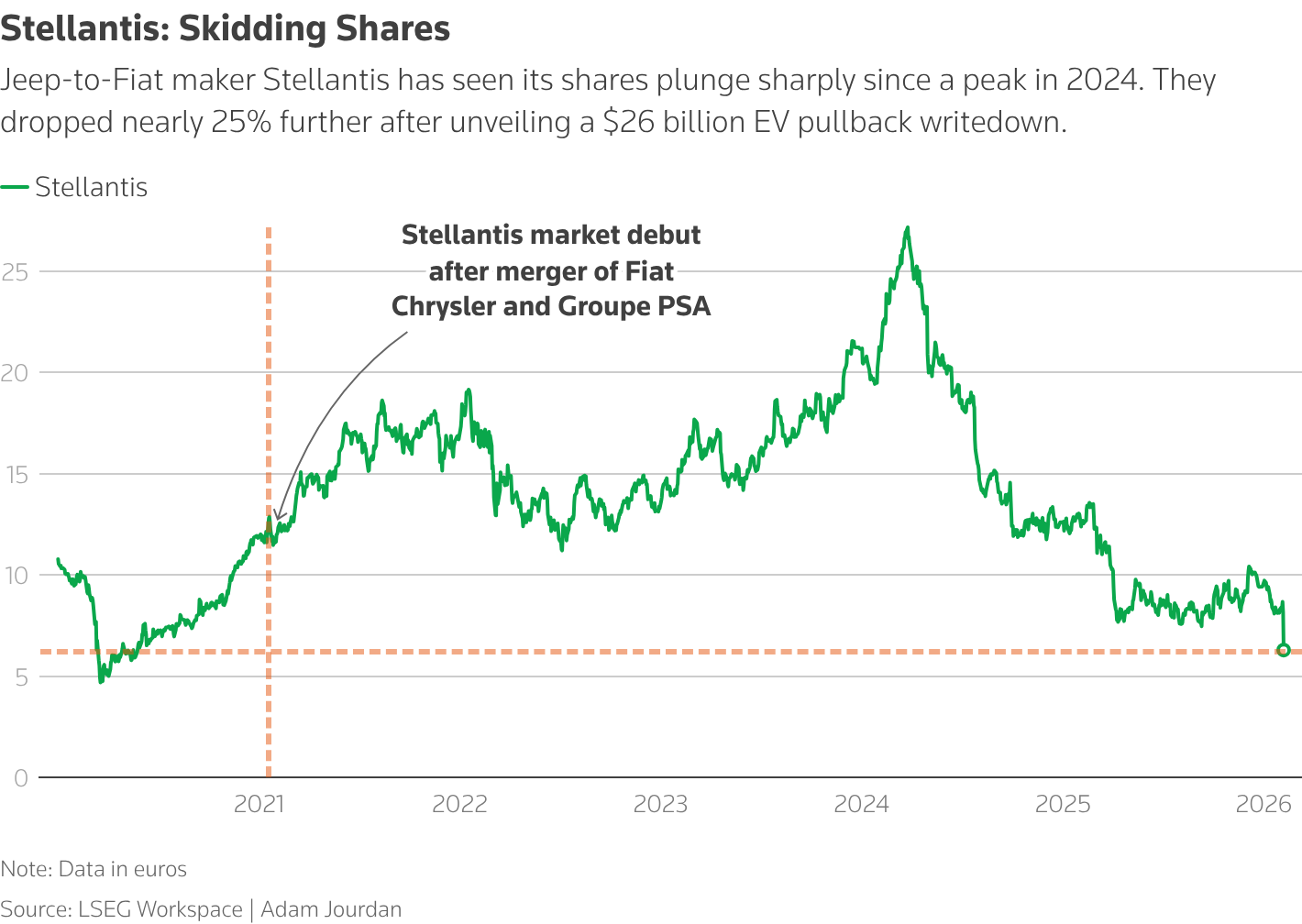

Let's be real. The automotive industry just had one of its most humbling moments in decades. Stellantis, the multinational automaker behind Jeep, Dodge, Fiat, Peugeot, and a dozen other brands, just announced a staggering $26.2 billion writedown. That's not a typo. Twenty-six point two billion dollars.

And here's the kicker: they're not the first. Ford swallowed a

This isn't just corporate accounting stuff. What's happening right now tells us something fundamental about how industries misjudge the future, how political change can reshape markets overnight, and what happens when the world changes faster than your business plan can adapt.

The irony is almost painful. Just a few years ago, every major automaker was positioning itself as an EV pioneer. Billions poured into battery factories. Charging networks were funded. Supply chains were rebuilt. The narrative was locked in: electrification was coming, and it was coming fast. The only question was who'd lead.

Then something unexpected happened. Reality collided with expectations.

Demand didn't materialize the way everyone predicted. Charging infrastructure lagged. EV prices remained stubbornly high compared to gas vehicles. Consumer preferences shifted. And then in November 2024, political winds changed direction entirely. With a change in US administration came a reversal of EV incentives, charger funding, and regulatory support that had been driving the whole transition.

Stellantis found itself caught in the middle, having invested heavily in platforms, factories, and product lineups that assumed a future that's no longer coming. And now they're paying the price.

But this story goes much deeper than one company's bad bet. It reveals how an entire industry miscalculated demand, how geopolitics shapes business strategy, and what the actual future of transportation might look like. Let's break down what happened, why it happened, and what it means for everyone from car buyers to investors.

The $26.2 Billion Breakdown: Where the Money Went

When Stellantis CEO Antonio Filosa announced the writedown, he didn't just throw out a number. He broke it down into specific categories, and that breakdown tells you exactly where the company went wrong.

Cancelled EV products accounted for $3.4 billion of the damage. The Ram electric truck was supposed to be Stellantis's answer to the Ford F-150 Lightning and Chevrolet Silverado EV. It never made it to market. The Jeep electric vehicle? Underwhelming consumer reception meant resources shifted elsewhere. These weren't just theoretical losses. The company had already spent money developing these vehicles, setting up manufacturing lines, and building supply chains. Once they hit the brakes, that capital essentially evaporated.

Platform amortization issues cost another $7.1 billion. This is the real kicker. Automakers build platforms—essentially the underlying structure and components that multiple vehicle models share. It's supposed to spread costs across dozens of vehicles over many years. But if you build a platform expecting to sell millions of EVs and suddenly that demand doesn't materialize, you're amortizing those costs across far fewer vehicles. That means each vehicle is much more expensive to produce. Essentially, Stellantis discovered that the financial math they'd done—assuming high EV sales volumes—wasn't going to work.

Cash obligations to existing contracts ate up $6.8 billion. This is money the company has already promised to pay over the next four years. Some of this goes to suppliers, some to joint ventures, some to commitments they made when they thought the EV transition was inevitable.

Then there's the supply chain restructuring. Stellantis ordered thousands of batteries from suppliers worldwide. They ramped up production expecting massive EV demand. When that demand didn't materialize at the expected pace, they had to resize their supply chain. That cost

Warranty issues and ongoing problems added another $4.8 billion to the bill. Some of Stellantis's existing vehicles had quality issues that required recalls, repairs, and customer compensation. These costs were already baked into operations, but the company had to take additional charges to cover them.

That's how you get to $26.2 billion. It's not one bad decision. It's multiple layers of misjudgment, bad timing, and circumstances beyond their control all stacking on top of each other.

Stellantis announced the largest writedown at $26.2 billion, indicating a significant strategic shift and miscalculation in EV adoption compared to Ford and General Motors.

Why Did Stellantis Miss the Mark So Badly?

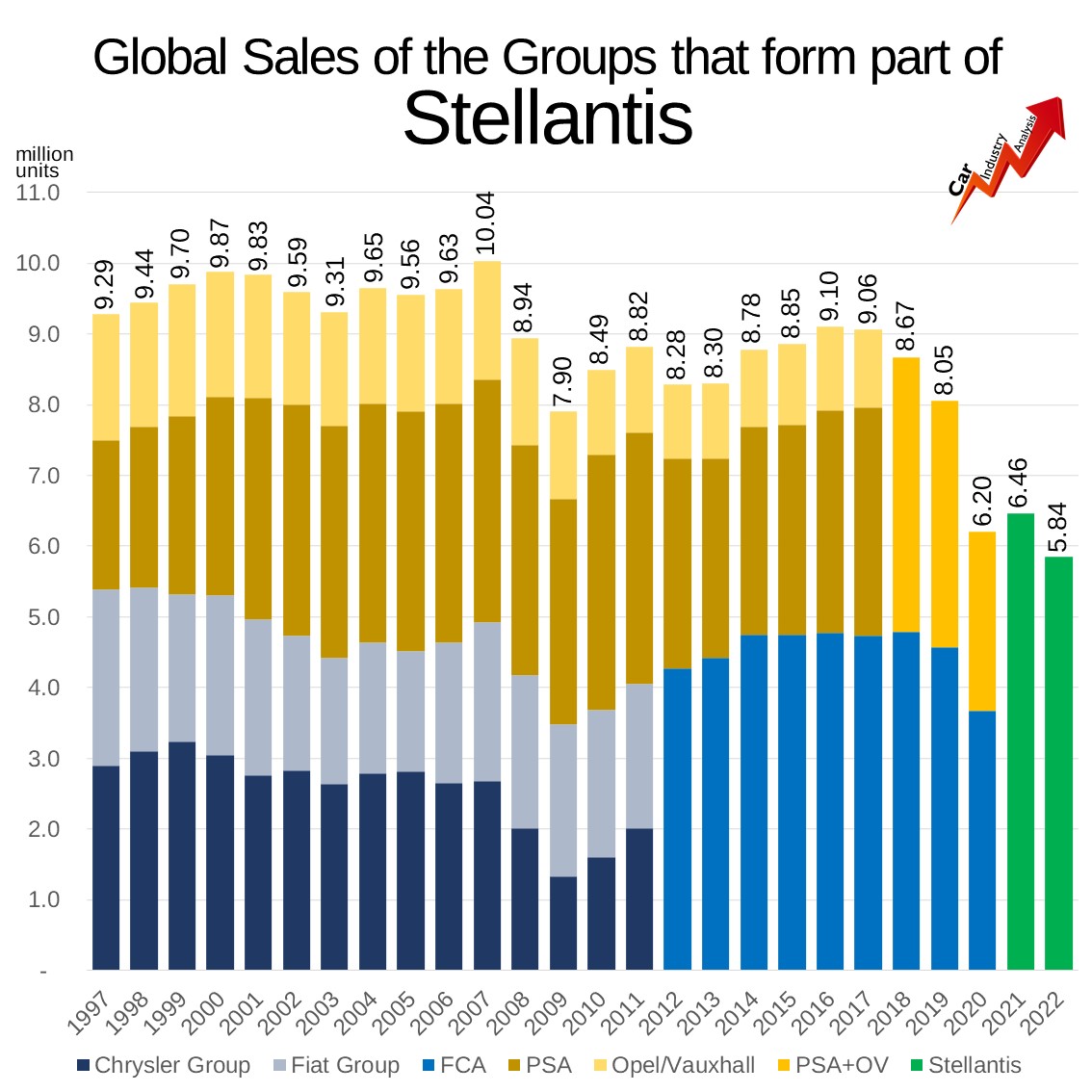

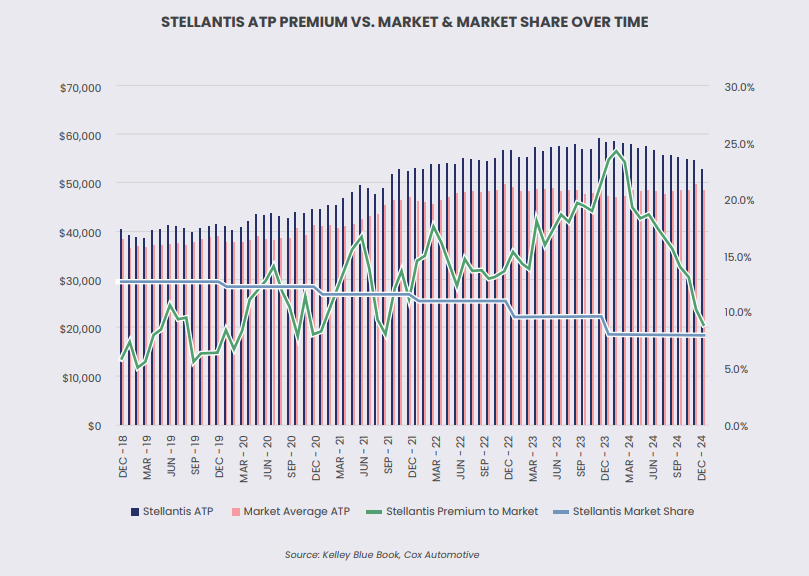

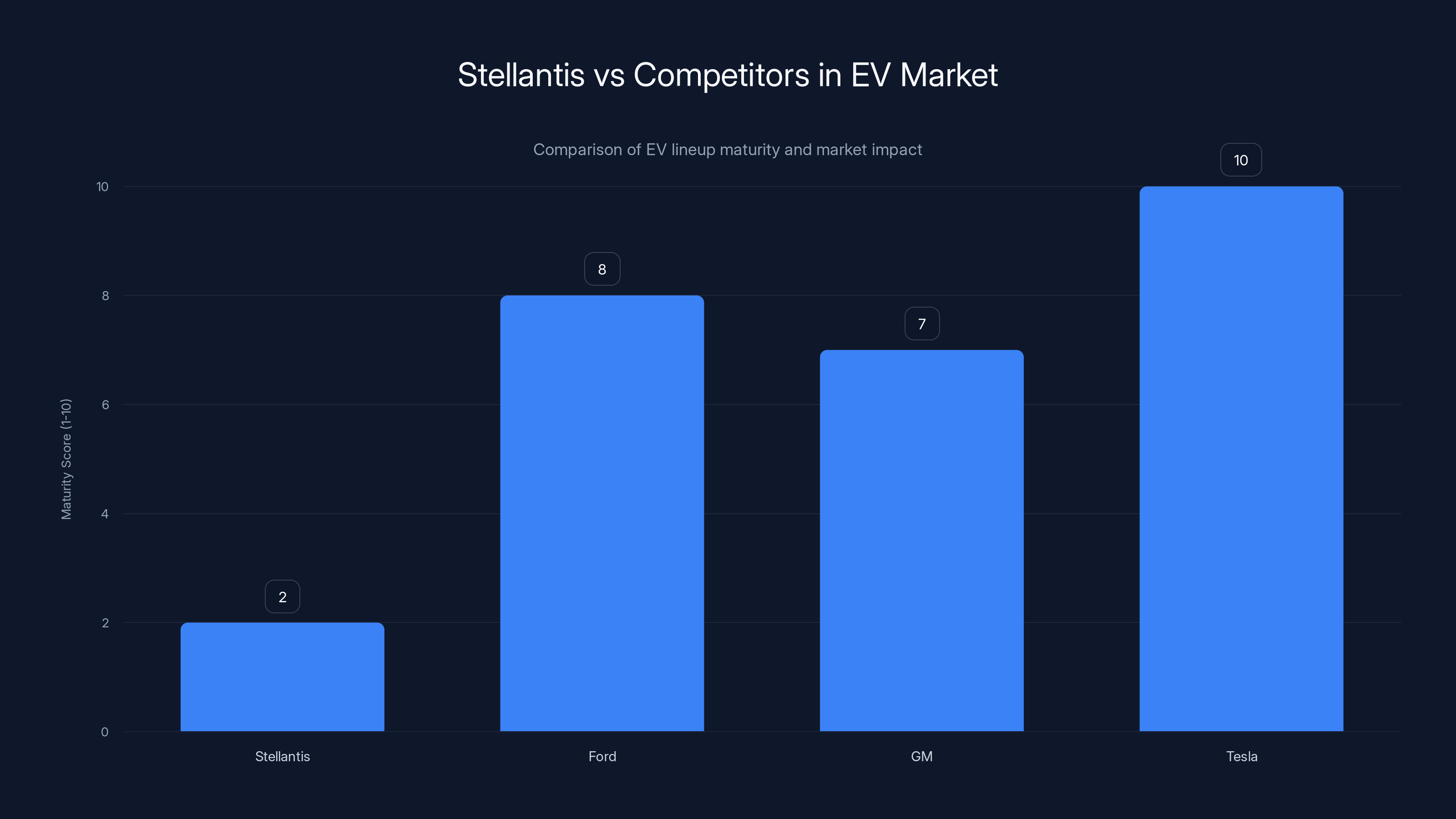

Understanding Stellantis's specific failures requires understanding the broader context. But first, let's acknowledge what happened: the company lagged behind competitors in electrification from the beginning.

While Ford and GM were developing mature EV lineups, Stellantis was playing catch-up. The company's first major US EV, a Jeep model, arrived later than expected and didn't generate the excitement automakers hoped for. Ram, a brand famous for pickup trucks, never managed to get an electric version to market that could compete with Ford's Lightning.

This wasn't accidental. Stellantis made strategic choices that, in hindsight, were wrong.

First, the company underestimated how long consumers would be willing to tolerate the constraints of EV ownership. Early EVs had limited range, charging infrastructure was sparse, and prices were significantly higher than gas vehicles. Stellantis expected consumers to overlook these issues faster than they actually did. They thought the EV transition would be like the transition from flip phones to smartphones—once you tried it, you'd never go back. But cars aren't phones. People need them reliably, and switching fuel types is a much bigger commitment.

Second, Stellantis overestimated government support's staying power. US policy heavily subsidized EV purchases through tax credits up to $7,500. Charging infrastructure received billions in federal funding. Fuel efficiency standards kept tightening, making it expensive for automakers to sell traditional gas vehicles. Stellantis, along with most of the industry, treated these policies as permanent fixtures. They weren't. The moment political control shifted, support evaporated.

Third, Stellantis had organizational execution challenges. The company was formed from the merger of Fiat Chrysler and the PSA Group in 2021. It was already dealing with integration issues when the EV transition accelerated. Add in supply chain disruptions from COVID, semiconductor shortages, and broader economic uncertainty, and you've got a company struggling to execute even its planned strategy.

Fourth, there's the dealer network problem. Stellantis has thousands of independent dealers who sell its vehicles. These dealers were uncomfortable with the EV transition. They didn't want to invest in charging equipment at dealerships. They worried about losing margin on service (EVs need less maintenance). They didn't understand the technology. Rather than pushing dealers to adapt, Stellantis listened to their concerns and slowed its EV rollout. This gave the company an excuse for underperformance, but it also meant they lost ground to competitors who were more aggressive.

These factors combined to create a company that was late to market, slow to execute, and unprepared when market conditions shifted.

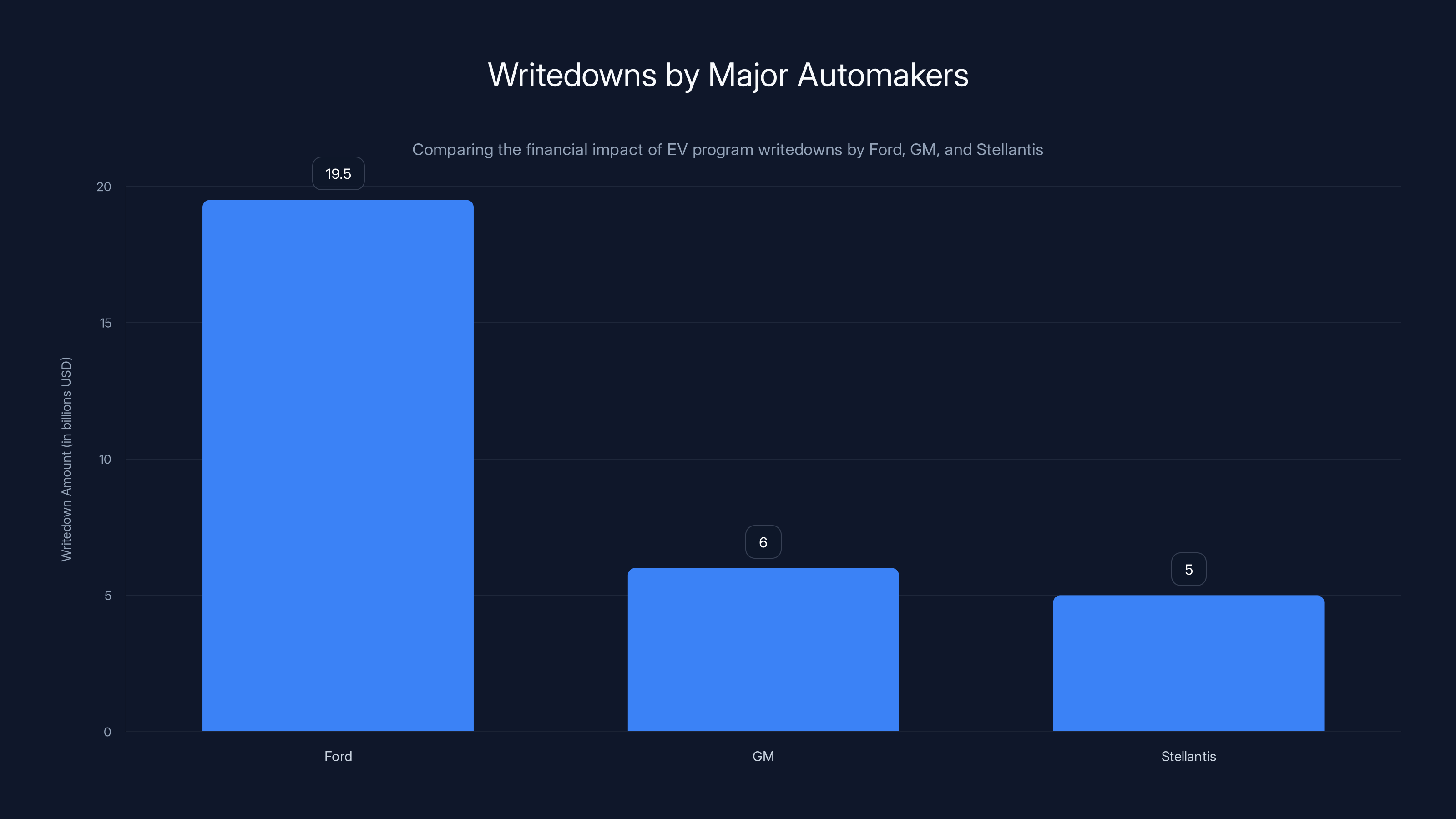

Ford, GM, and Stellantis faced significant financial impacts due to EV program writedowns, with Ford's being the largest at $19.5 billion. Estimated data for Stellantis based on industry trends.

The Broader Industry Pattern: Ford and GM's Writedowns

Here's what's important to understand: Stellantis didn't fail alone. Two weeks before Stellantis's announcement, General Motors took a

These weren't isolated incidents. They were part of a coordinated—though not deliberately coordinated—industry reckoning.

Ford's situation was particularly interesting. Ford had actually been more aggressive than most in its EV transition. The F-150 Lightning was a real product, backed by real investment. But the company discovered that even successful EV products weren't generating the profit margins they needed. EVs cost more to produce, sell at lower prices (due to competition), and face higher interest rates when customers finance them. The economics didn't work the way Ford's models predicted.

GM's writedown was smaller in absolute terms, but it reflected similar issues. The company had announced plans for aggressive EV production but discovered that demand wasn't materializing fast enough to justify the capital spending.

What these three companies discovered independently confirms something important: it wasn't just one company making bad bets. The entire industry miscalculated. They misread demand curves. They overestimated consumer adoption speed. They built supply chains for a future that's arriving more slowly than expected.

The writedowns also reflect something less obvious: the cost of capital. When interest rates are high, the financial math on long-term capital investments changes. A factory that makes sense to build when you can borrow at 2% becomes much less attractive at 7%. Automakers had committed to billions in capex when rates were low. When rates rose, those commitments became much more expensive to carry.

Political Upheaval and the EV Incentive Cliff

There's a specific moment you can point to when things changed for Stellantis: November 5, 2024.

That's when the US political landscape shifted. And with it came an immediate pivot on EV policy.

In the years leading up to November 2024, the US federal government was aggressively pushing electrification. The Inflation Reduction Act provided tax credits for EV purchases. Federal funding was allocated for charging infrastructure. The EPA tightened fuel efficiency standards, essentially making it economically impossible for automakers to sell lots of low-margin gas vehicles.

Automakers, including Stellantis, planned their entire business strategies around these policies. They assumed the incentives would continue. They assumed the charger network would expand. They assumed consumers would have financial reasons to buy EVs.

Then political control changed. And within weeks, the policy environment was inverted.

The incoming administration immediately signaled it would reverse course. EV tax credits were targeted for elimination. Charger funding was questioned. Fuel efficiency standards were slated for revision. The message to automakers was clear: don't count on government support for electrification anymore.

For Stellantis, which had positioned itself to benefit from these incentives, this was catastrophic. Consumer demand for EVs is partially dependent on government support. Remove the tax credit, and a

This is exactly what happened.

Within weeks of the policy announcement, consumer EV orders softened. Automakers started reassessing their production plans. And executives realized that their billion-dollar commitments to EV production were based on assumptions that were no longer valid.

Stellanits, Ford, and GM weren't being political in their response. They were being rational. They were pivoting their capital allocation based on changed circumstances. But those changed circumstances meant admitting that previous capital allocations were mistakes.

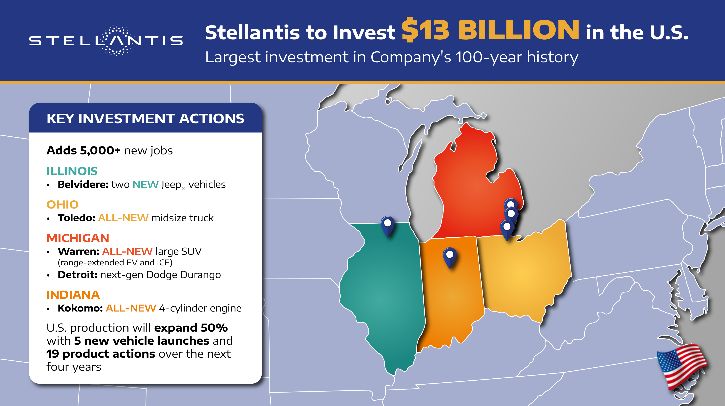

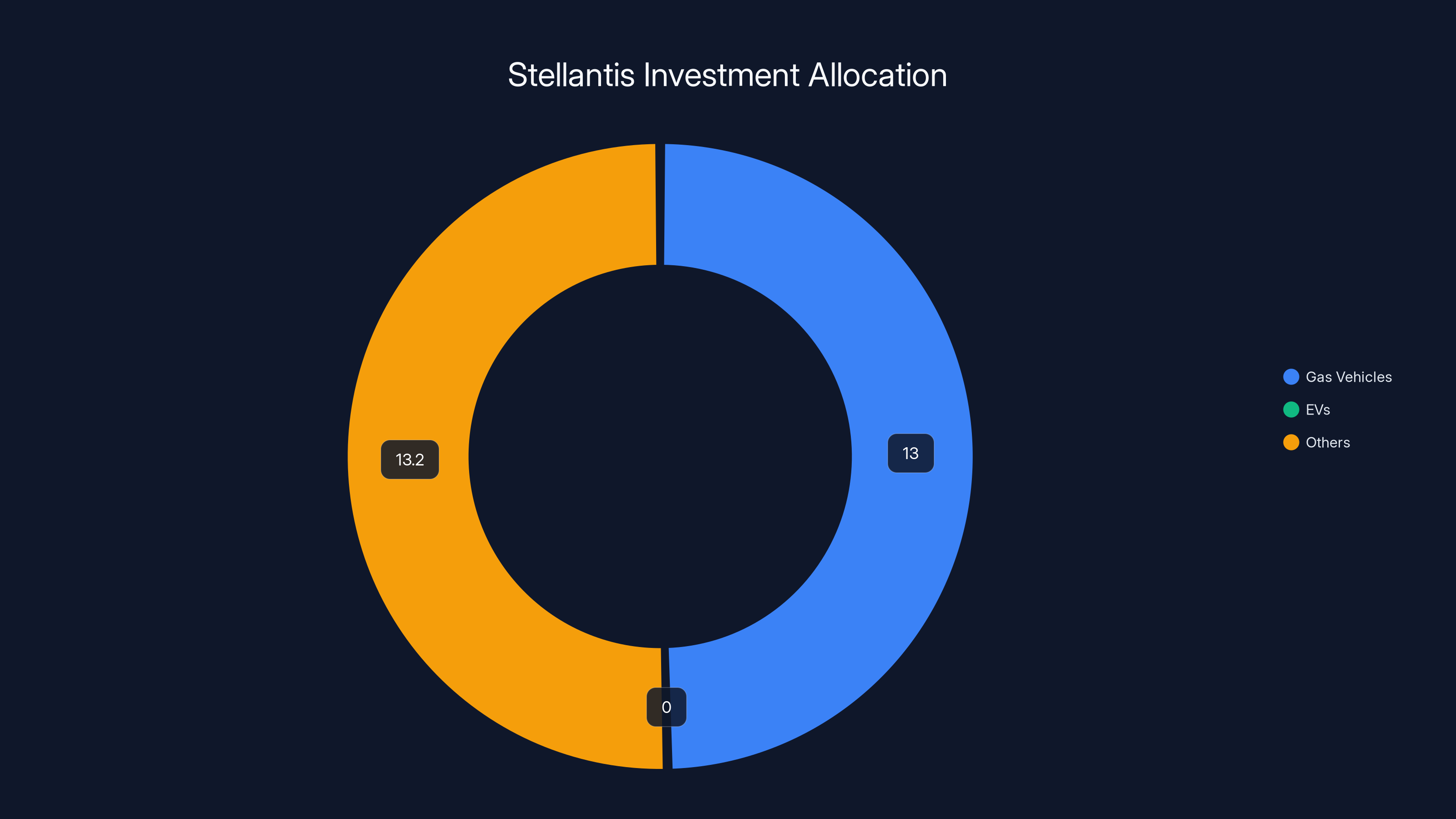

Stellantis plans to invest $13 billion in gas vehicles, focusing on trucks and SUVs, reflecting a strategic pivot away from EVs. Estimated data based on narrative.

The Dealer Network and the Grassroots Pressure Campaign

One aspect of the Stellantis situation that deserves more attention is the role of the dealer network in slowing the company's EV transition.

Automakers in the US don't sell cars directly to consumers. They work through independent dealers. This dealer network has enormous political influence. When dealers object to something, automakers listen.

Dealers had serious concerns about EVs. First, there's the margin issue. When a customer buys a gas car and comes in for oil changes, tune-ups, and repairs, the dealer makes money on service. EVs need far less maintenance. No oil changes. No spark plugs. Fewer moving parts. The service revenue stream that dealers rely on simply vanishes.

Second, there's the investment issue. Dealers would have to install charging equipment. They'd have to train technicians to work on EV powertrains. They'd have to reconfigure their showrooms. For a dealer running on thin margins, these are significant costs.

Third, there's the knowledge issue. Dealer salespeople grew up selling gas cars. They understood the product. They understood customer concerns. EVs represented a completely different sales pitch, and many dealers felt unprepared.

So dealers, both individually and through their trade associations, lobbied automakers to slow EV adoption. The message was clear: we're not ready for this. The demand isn't there yet. Build more gas vehicles. We'll push back against this transition.

Automakers listened. Stellantis particularly listened. Rather than pushing its dealer network to adapt—as Tesla does with its direct-to-consumer model, or as some other OEMs attempted—Stellantis accommodated dealer concerns. This meant slowing EV launches, reducing EV inventory, and focusing on traditional vehicles.

This was a strategic error. By listening to dealers, Stellantis gave up market share to competitors who were moving faster. And it left the company vulnerable when market conditions changed. When political support for EVs evaporated, Stellantis didn't have a portfolio of proven EV products to fall back on. The company had spent billions on EV platforms and infrastructure but hadn't built enough successful EV products to justify those investments.

Stellantis's Pivot: Back to Gas, Trucks, and Nostalgia

Now comes the interesting part. What's Stellantis doing with the $26.2 billion writedown behind them?

They're pivoting. Hard.

Going forward, Stellantis says it will invest $13 billion in the United States. But not on EVs. On traditional gas vehicles. Specifically, trucks and SUVs.

The company plans to add 5,000 manufacturing jobs in the US. Those jobs will be focused on producing the kinds of vehicles that Americans have historically loved: big pickups and spacious SUVs.

Part of this pivot includes bringing back the V8 engine. The Ram 1500 will get a new V8 option. The Dodge Charger—a car with tremendous brand heritage—will return as a gas-powered vehicle. Various Jeep models will remain gas-focused rather than transitioning to electric.

This is a complete reversal from where Stellantis was just a few years ago. But it reflects a realistic assessment of market conditions.

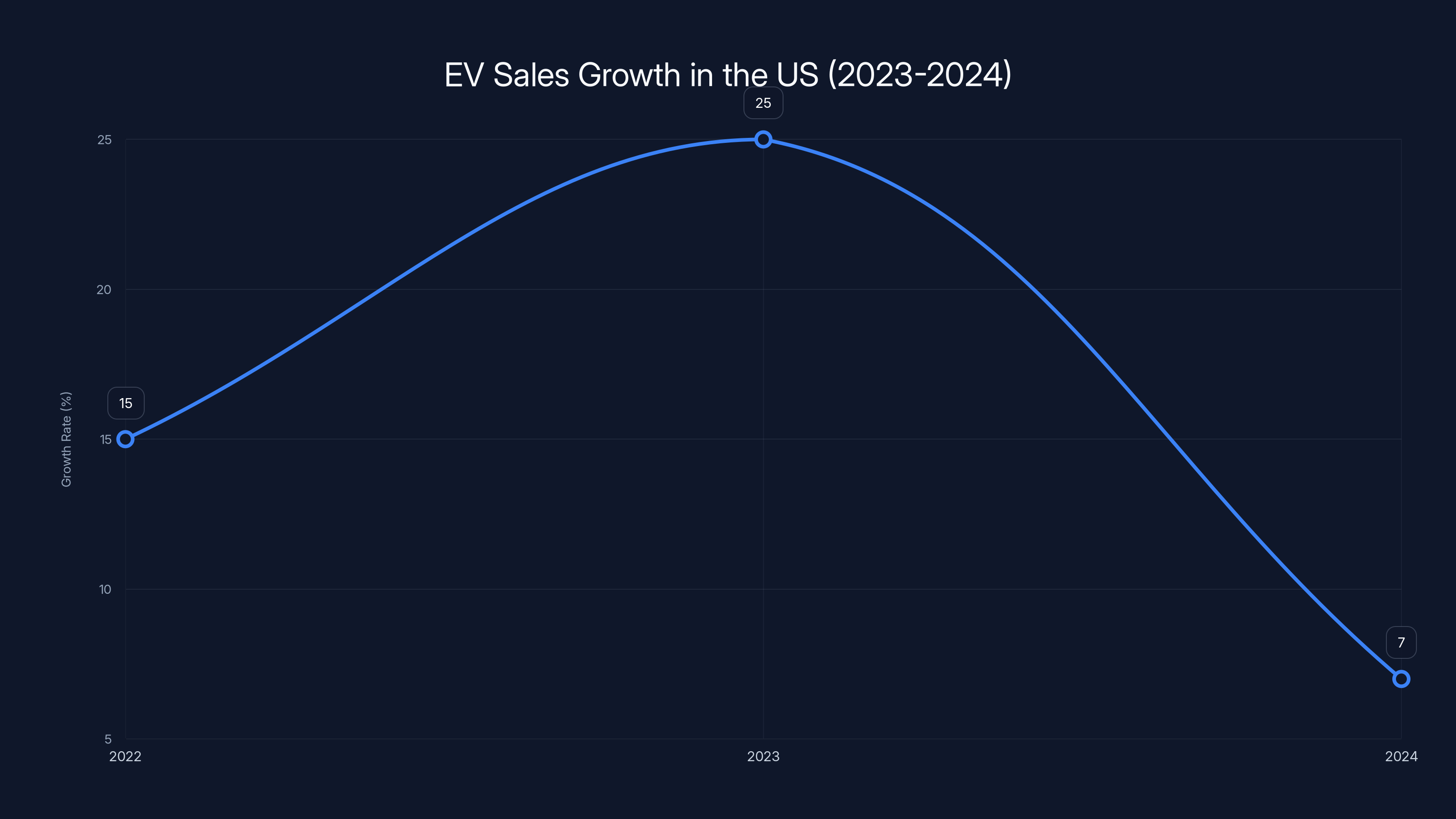

The data is actually pretty clear. Consumer demand for EVs has softened significantly. In the US market, EV sales growth has slowed from double-digit percentages to single-digit growth. Consumers cite concerns about range anxiety, charging access, and price. These concerns aren't irrational. They're legitimate obstacles to EV adoption.

Meanwhile, demand for trucks and SUVs remains robust. These vehicles have enormous brand loyalty. Customers specifically want them. The margins are typically higher than on EVs. And with the removal of regulatory pressure to transition, automakers can serve the market that actually exists rather than the market they think should exist.

But here's the tension: Stellantis is pivoting to gas vehicles while still holding massive EV-related assets and commitments. The company has contracts to buy batteries. It has EV platforms it's invested in. It has factories that were retooled for EV production. Simply reversing direction isn't costless.

This is why the writedown had to be so large. The company isn't just accepting past losses. It's restructuring its entire future around a different market reality.

Stellantis lags behind competitors like Ford and GM in EV lineup maturity, impacting market competitiveness. Estimated data.

The Dealer Problem, Solved

One benefit of Stellantis's pivot is that it solves the dealer problem. Dealers want to sell gas vehicles? Perfect. That's exactly what Stellantis is building now.

But this raises a question: was the dealer network a victim of the pivot, or a beneficiary?

Dealers wanted to continue selling gas cars. They lobbied for gas cars. Stellantis accommodated dealers and focused on gas cars. Stellantis took a massive writedown. And now Stellantis is building what dealers wanted in the first place.

The cynical reading is that dealers essentially stalled an EV transition they didn't want, cost their own company tens of billions of dollars, and then got what they wanted anyway. The more generous reading is that dealers understood consumer demand better than executives, and the market ultimately proved them right.

Either way, there's a structural problem here. Dealers have the power to shape automaker strategy because they control the retail distribution network. When dealer incentives misalign with automaker long-term interests, the result can be suboptimal decisions that cost everyone money.

This is one reason why Tesla's direct-to-consumer model, controversial as it is, gives the company strategic flexibility. Tesla doesn't have to accommodate dealer concerns. It can pursue its long-term vision without political pressure from an intermediate layer.

Consumer Demand: The Reality Check

Underneath all the corporate strategy and writedowns is a simple truth: consumers are more hesitant about EVs than the industry assumed.

This isn't surprising once you start asking people actual questions. Range anxiety is real. A gas car can go 300-400 miles on a tank and refuel in five minutes at any of 150,000 gas stations across the country. An EV might go 250-300 miles on a charge and recharge in 30 minutes at a far smaller network of chargers. For certain use cases—long-distance road trips, people without home charging—the limitations are genuine.

Price is real too. The cheapest new EV available in the US still costs more than most entry-level gas cars. Yes, they're cheaper to fuel and maintain long-term, but the upfront cost barrier is substantial.

Then there's psychology. People understand gas cars. The technology is familiar. They know how to maintain them. They know what to expect. EVs represent a change, and change carries risk. What if charging is unreliable? What if the battery degrades faster than expected? What if you get stuck without a charger? These aren't irrational fears.

Automakers didn't account for these consumer hesitations. They assumed that once EVs were available, people would buy them en masse. They didn't. Consumers bought EVs when they had compelling reasons—tax credits, environmental values, desire for new technology—but these reasons were insufficient to drive adoption at the pace automakers expected.

Remove the tax credits, and the value proposition weakens even more. Suddenly, buying an EV requires making a significant price sacrifice without the government subsidy to offset it.

EV sales in the US grew by 25% in 2023 but slowed to 7% in 2024 as consumer hesitation increased and incentives weakened. Estimated data.

The Supply Chain Restructuring

One of the hidden costs in Stellantis's writedown is the supply chain restructuring. The company spent $2.5 billion to resize its battery supply and other EV-related inputs.

This reflects a specific problem. Automakers sign long-term contracts with battery suppliers. They commit to purchasing certain quantities. When demand for EVs softens, they're stuck with those commitments. They can try to renegotiate, but suppliers have already made their own investments based on those contracts.

Battery suppliers expanded capacity globally based on automaker commitments. If an automaker suddenly says "we're buying less," the supplier is left with excess capacity. Both parties lose.

Stellanatis had to unwind these contracts, pay suppliers, and restructure its battery sourcing. The company is buying fewer batteries overall. It's also likely renegotiating prices. Some battery suppliers will face reduced demand and may have to write down their own assets.

This is why the supply chain restructuring costs were so high. It's not just about buying fewer batteries. It's about unwinding complex, global supply relationships that were built on different assumptions.

Warranty Costs and Quality Issues

The $4.8 billion warranty charge reflects something less obvious: some of Stellantis's recent vehicles had quality problems.

Automakers build in reserves for warranty claims. But if problems are worse than expected, they have to take additional charges. Stellantis did, indicating that some of its recent model years had more issues than anticipated.

This could relate to the rushed development of EV models. Bringing EV products to market quickly sometimes means quality suffers. Or it could reflect broader manufacturing issues related to the supply chain chaos of 2020-2022.

Either way, the warranty costs are real. They reflect customer dissatisfaction and repair costs that will continue to burden the company for years as warranty claims come in.

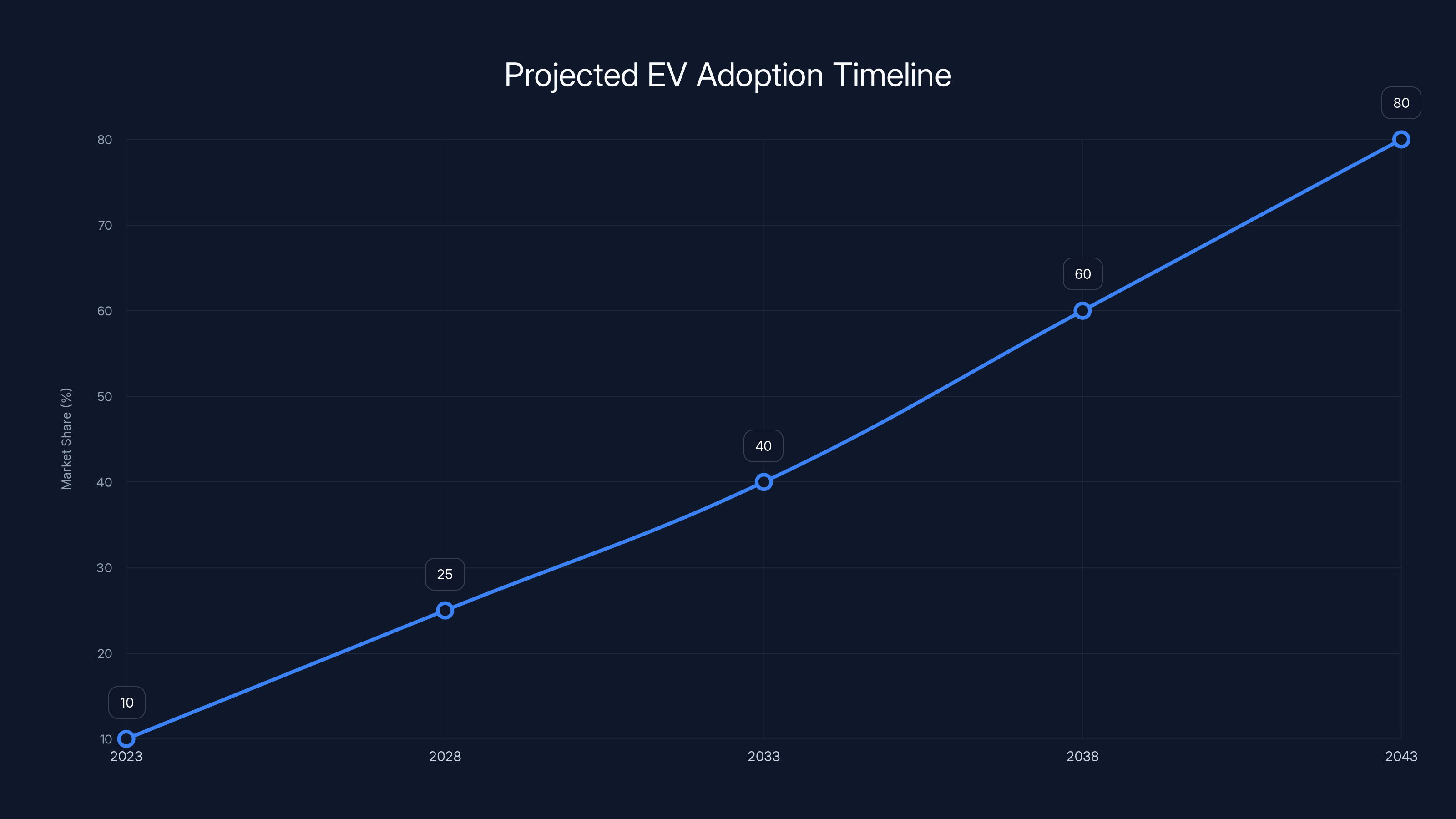

The transition to electric vehicles (EVs) is expected to gradually increase over the next two decades, reaching 80% market share by 2043. Estimated data reflects industry predictions.

European Job Losses and Labor Costs

The $1.5 billion charge for European layoffs is significant, but it's also where Stellantis had limited options.

In Europe, labor laws are protective. Laying off workers isn't simple. Companies typically have to provide severance, extended notice periods, and comply with complex regulations. The cost to reduce workforce in Europe is substantially higher than in the US.

Stellanitis had built manufacturing capacity in Europe with the assumption of high EV demand. When that demand didn't materialize, European capacity became excess. The company had to reduce the workforce.

But here's an interesting note: Stellantis is actually planning to add 5,000 jobs in the United States while cutting jobs in Europe. This reflects where the company sees growth: in American trucks and SUVs. European consumers are more environmentally conscious and may ultimately embrace EVs faster than American consumers. But Stellantis doesn't have confidence in European EV demand in the near term.

The Broader Industry Question: What About Other Automakers?

If Ford, GM, and Stellantis are all taking massive writedowns, are other automakers facing similar problems?

Likely yes. Volkswagen, Hyundai, Kia, and others have all made significant bets on EV transitions. They've all built battery partnerships, new plants, and EV-focused supply chains. If EV demand continues to soften—especially with policy support withdrawn—they'll all face pressure to write down assets and restructure strategies.

Volkswagen, which invested heavily in EV production in Germany and elsewhere, is already signaling potential problems. The company has warned about challenges in the European market and potential job losses.

Hyundai and Kia, which moved faster into EVs than many competitors, might have better positions. But they're not immune to demand softening.

Chinese automakers, which build cheaper EVs and have enormous domestic EV demand, might weather this better. But even they are vulnerable to global demand weakness.

The broader point: Stellantis, Ford, and GM are canaries in the coal mine. Their writedowns signal that an entire industry miscalculated. Other automakers will eventually face similar pressure to revalue assets and restructure strategies.

What Happens to EV Transition Now?

Here's the crucial question: does this mean the EV transition is over?

No. But it does mean the transition is much slower and messier than previously expected.

EVs are still being developed and improved. Battery technology is advancing. Prices will eventually come down. The economics will eventually improve. Consumer acceptance will eventually increase.

But this will happen over decades, not years. The rapid transition that automakers expected in the 2020s isn't materializing. Instead, we'll likely see a gradual shift where EVs capture an increasing share of the market, but at a much slower pace.

Meanwhile, gas vehicles with advanced efficiency will remain dominant. Hybrids—which offer the best of both worlds for many consumers—might actually capture more market share than pure EVs in the near to medium term.

This creates a strange market dynamic. Automakers need to continue investing in EV technology because eventually, governments will likely re-tighten emissions standards. They can't abandon electrification entirely. But they also can't justify massive near-term spending on EV-specific platforms and supply chains if demand won't materialize for years.

The result is a holding pattern. Automakers are building hybrids. They're bringing back trusted gas engines. They're updating traditional platforms. But they're also maintaining some EV development capacity, betting that eventually, they'll need it.

Stellanitas's decision to pivot back to gas vehicles is a short-term strategy in a market that will eventually demand electrification anyway. It's not a permanent solution. It's a way to minimize losses now while maintaining flexibility for a future transition.

The Geopolitical Dimension: Why This Matters

There's one more layer to this story: geopolitics.

The EV transition was always partly about energy security. The US wanted to reduce dependence on oil and OPEC. Europe wanted similar independence. Electrification was seen as a way to achieve this while simultaneously addressing climate change.

But a slower EV transition means longer dependence on oil. That has geopolitical implications for US foreign policy in the Middle East and elsewhere.

It also affects the competition with China. Chinese automakers and battery suppliers have massive advantages in EV technology and production capacity. If the global EV transition accelerates, China benefits. If it slows, Western automakers get more time to catch up.

The policy reversal in the US might actually be partly about this geopolitical calculation. Some policymakers may have decided that allowing the EV transition to move too fast would cede too much advantage to China. By slowing domestic EV adoption and maintaining gas vehicle production, the US keeps traditional automotive technology competitive longer.

This is speculative, but it's worth considering. The Stellantis writedown isn't just about automotive strategy. It's caught up in larger questions about energy, geopolitics, and strategic competition.

Lessons: What Can Be Learned from This

So what are the actual takeaways from all this?

First, even the largest companies can be spectacularly wrong about technology transitions. Stellantis, Ford, and GM are among the most sophisticated corporations in the world. They have armies of strategists, data scientists, and market researchers. Yet they all miscalculated on EV adoption. This should be humbling for anyone assuming they can predict technological or market futures with high confidence.

Second, policy matters enormously. Remove government support, and the entire value proposition for a technology can shift. Automakers should have hedged against policy risk. The fact that they didn't, and apparently didn't expect policy to reverse, is striking.

Third, intermediate actors—in this case, dealers—can have outsized influence on strategy. Stellantis accommodated dealer concerns, and this likely slowed its EV transition at a critical moment. The lesson isn't that dealers were wrong, but that structural relationships between companies and their distribution networks can create misaligned incentives.

Fourth, consumer preferences matter more than industry narratives. The industry narrative was "EV transition is inevitable and imminent." Consumer preferences were "I'm not yet convinced." When these conflict, consumers win. Automakers have to serve the market that exists, not the market they think should exist.

Fifth, capital allocation mistakes are expensive and take years to unwind. Once you've built a factory, signed supplier contracts, and committed to product development, reversing course is costly. This argues for more cautious capital planning during uncertain transitions.

FAQ

What is the Stellantis $26.2 billion writedown?

Stellanitis announced a $26.2 billion (€22.2 billion) writedown in February 2025 as it restructured its business strategy away from rapid EV transition and back toward traditional gas vehicles. The writedown includes charges for cancelled EV products, platform amortization, supply chain restructuring, workforce reductions, and warranty issues—essentially an admission that the company badly miscalculated EV adoption rates and market demand.

Why did Stellantis take such a large writedown?

Stellanitis built its EV strategy on assumptions that didn't materialize: rapid consumer adoption of electric vehicles, sustained government support through tax credits and charging infrastructure funding, and strong demand across its product portfolio. When consumer demand softened, government incentives were reversed after the November 2024 US election, and regulatory pressure for electrification eased, these assumptions collapsed. The company had already invested billions in EV platforms, batteries, factories, and supply chain commitments that became excess capacity and had to be written off.

How does Stellantis's writedown compare to other automakers?

Ford announced a

What is Stellantis doing with the money after the writedown?

Stellanitis is investing $13 billion in the United States to expand production of traditional gas vehicles, trucks, and SUVs. The company plans to add 5,000 manufacturing jobs focused on vehicles like the Ram 1500 with a new V8 option, a gas-powered Dodge Charger, and gas-focused Jeep models. This represents a strategic pivot from EV-focused capital allocation to serving proven consumer demand for trucks and SUVs.

What caused the shift away from EV strategy?

Multiple factors converged: consumer demand for EVs softened as the initial adopter wave plateaued and price/range concerns became more acute, government support evaporated with the change in US administration (removal of EV tax credits and charging infrastructure funding), regulatory pressure for electrification was reversed, and dealer networks successfully lobbied against rapid EV transitions. Politically, the 2024 US election brought policymakers who prioritized traditional automotive industries over accelerated electrification.

How will this affect consumers shopping for cars?

The Stellantis pivot means more traditional gas vehicles, trucks, and SUVs in the market near-term, particularly new gas-powered models like the Dodge Charger and Ram V8. For consumers, this extends the availability of familiar technologies and potentially lowers prices in the truck and SUV segments through increased competition. However, it also delays EV availability from Stellantis and pushes back the timeline for widespread electrification, meaning fuel efficiency and emissions remain concerns longer than previously expected.

Will the EV transition continue?

Yes, but much more slowly than the automotive industry assumed. EVs will continue to improve and eventually become cost-competitive with gas vehicles, but this timeline has extended from the 2020s into the 2030s and beyond. Governments will eventually re-tighten emissions standards as climate concerns persist. The transition is happening, just not at the pace or scale that Stellantis, Ford, and GM had planned for when they committed billions to EV infrastructure.

What does this mean for battery suppliers and EV infrastructure?

Battery suppliers face reduced near-term demand as automakers lower EV production expectations. Companies that expanded capacity based on automaker commitments now have excess capacity and will face pricing pressure and reduced revenue. The charging infrastructure buildout also slows with the withdrawal of federal funding, though private networks continue to expand. This creates a challenging environment for EV supply chain companies that expanded based on growth assumptions that are no longer valid.

Could policy changes reverse again and force another pivot?

Absolutely. If future administrations re-prioritize electrification, Stellantis and other automakers would face pressure to shift capital allocation again. The company is trying to maintain some flexibility—it's not abandoning EV development entirely—but major pivots are expensive and disruptive. The cost of policy uncertainty is that automakers must hedge against multiple possible futures, which is inefficient and costly.

What's the lesson for investors and business leaders?

The Stellantis situation demonstrates that even sophisticated, large-scale organizations can be spectacularly wrong about major industry transitions. Technology adoption rates are difficult to predict accurately. Policy changes can rapidly shift business assumptions. And large capital commitments based on uncertain forecasts can result in multi-billion-dollar losses. The lesson is humility about the future and diversification of capital allocation across multiple possible scenarios.

Conclusion

When Stellantis announced its $26.2 billion writedown, the company's CEO positioned it as a necessary correction—an adaptation to reality after "over-estimating the pace of the energy transition that distanced us from many car buyers' real-world needs, means and desires."

That's diplomatic language for: we got it really wrong.

But Stellantis wasn't alone. Ford and GM made essentially the same bets and discovered the same things simultaneously. The entire automotive industry miscalculated. They misread consumer demand. They overestimated policy stability. They built supply chains for a future that wasn't coming, at least not at the speed they expected.

The painful irony is that the EV transition is still coming. Eventually, electrification will dominate the automotive industry. But it will take decades, not years. And the path there won't be linear. There will be technological advances and setbacks, policy reversals and reinstatements, market booms and busts.

For now, Stellantis and its competitors are pivoting to what they know works: trucks, SUVs, and gas engines. It's a retreat from the vision of rapid electrification that executives proclaimed just a few years ago. It's also a realistic acknowledgment of what consumers actually want and what the market will actually bear.

The $26.2 billion writedown is expensive tuition for learning this lesson. But for investors, competitors, and policymakers, it's also valuable information. It reveals how markets actually work when corporate strategy collides with consumer preference. It shows what happens when you bet the company on policy that turns out to be reversible. And it demonstrates that even the largest, most sophisticated organizations can be confidently, expensively wrong about the future.

That's perhaps the most important takeaway: the future is harder to predict than we think, and betting billions on a single vision of it is genuinely risky. Diversification, humility, and hedging against uncertainty aren't just abstract best practices. They're survival strategies in environments where assumptions can become invalid at the speed of a policy change or a shift in consumer sentiment.

Stellanitis will survive this. The company will continue building vehicles. It will eventually develop competitive EVs when market conditions support it. But the $26.2 billion hole in its finances is a permanent reminder that even automotive titans can get the future spectacularly, expensively wrong.

Key Takeaways

- Stellantis $26.2 billion writedown is the largest of three major automakers admitting EV strategy failures within 8 weeks

- The company significantly overestimated consumer EV adoption rates and underestimated the impact of policy reversals on demand

- Platform amortization (6.8B) represent the largest cost categories, showing structural lock-in from previous capital commitments

- Political change in November 2024 removed EV tax credits and charging infrastructure funding, fundamentally altering market conditions automakers had planned around

- Stellantis is pivoting to gas-powered trucks and SUVs with $13 billion US investment and 5,000 new jobs, reflecting realistic assessment of near-term consumer demand

- The EV transition continues but at much slower pace than expected—extending timelines from 2020s targets to 2030s and beyond

- Dealer networks successfully lobbied against rapid EV adoption, influencing Stellantis to slow its transition and possibly contributing to competitive disadvantage

- Battery suppliers face reduced demand and pricing pressure as automakers lower EV production expectations and restructure supply contracts

Related Articles

- UK Electric Car Campaign: 5 Critical Roadblocks the Government Ignores [2025]

- Is Tesla Still a Car Company? The EV Giant's Pivot to AI and Robotics [2025]

- Tesla Kills Model S and X Production: The Shift to Humanoid Robots [2025]

- Tesla's 2025 Revenue Decline: What Went Wrong [2025]

- Tesla's 46% Profit Collapse in 2025: What Went Wrong [2026]

- Why GM Is Ending Chevy Bolt EV Production in 2027 [2025]

![Stellantis $26 Billion EV Writedown: What It Means for Auto Industry [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/stellantis-26-billion-ev-writedown-what-it-means-for-auto-in/image-1-1770393988449.jpg)