Understanding Trump's 'Buy American' EV Charging Mandate

In early 2025, the Trump administration took a move that caught the entire EV infrastructure sector off guard. The Department of Transportation announced a new requirement: EV charging equipment receiving federal funding through the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) program must be built entirely in the United States, with 100 percent of components originating domestically. This decision was highlighted in a Utility Dive article.

On the surface, this sounds patriotic. Buy American. Support domestic manufacturing. Create jobs. The messaging writes itself. But scratch beneath the headline, and you'll find something more complicated, and frankly, more damaging to the program's stated objectives. This isn't a carefully calibrated policy to accelerate U.S. manufacturing capacity. It's a hard stop disguised as industrial policy.

To understand why, you need to know where we started. The NEVI program itself was a bipartisan effort, funded through the infrastructure law passed in 2021. Congress allocated $7.5 billion specifically to build out EV charging stations along highways and in rural communities. The goal was straightforward: create the infrastructure backbone that could convince Americans to buy electric vehicles. No chargers, no EV adoption. It's that simple.

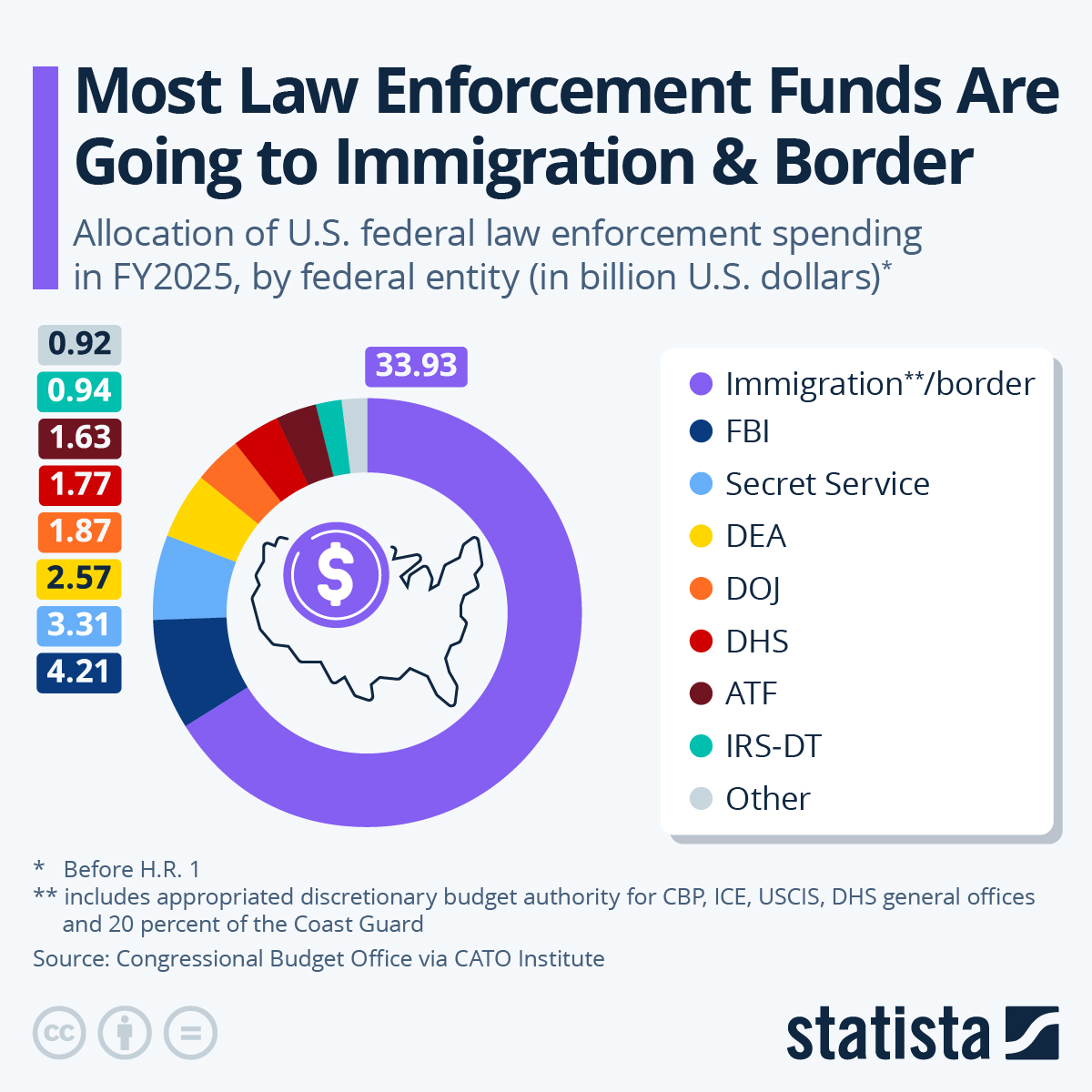

But Trump has made his opposition to EV policy crystal clear since taking office. His administration attempted to freeze the entire $5 billion in remaining NEVI funding outright. When a federal court ordered the government to unfreeze those funds, the administration pivoted. Instead of killing the program directly, they made it effectively impossible to use the money. Enter the Buy American requirement at 100 percent compliance.

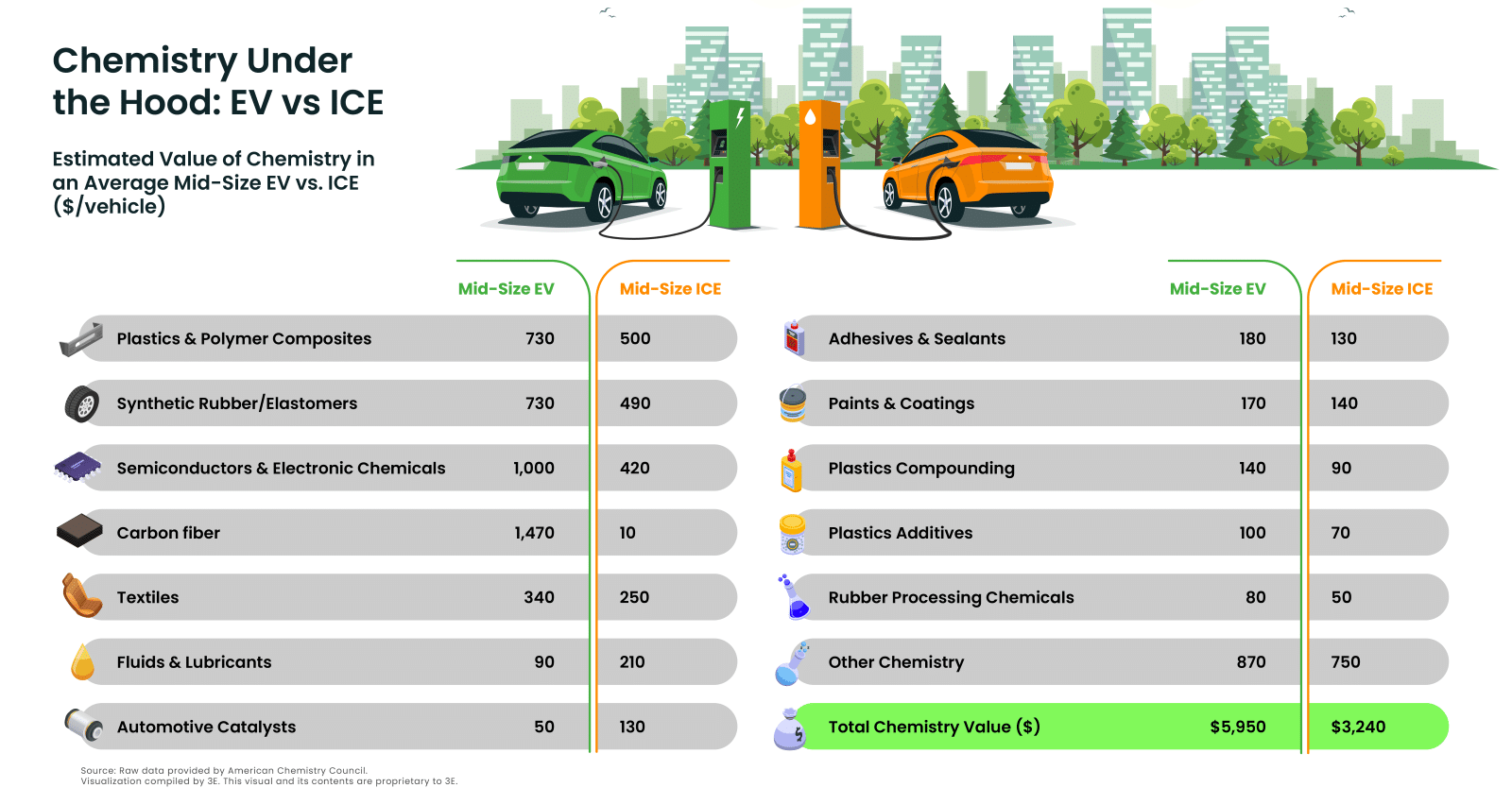

Here's the brutal logic: no charging manufacturer in the United States, not one, can currently source 100 percent of components domestically. Not Tesla. Not any of the companies racing to build charging infrastructure. The supply chain for power electronics, advanced semiconductor components, and critical manufacturing equipment is genuinely global. You can't just flip a switch and reshore an entire industry overnight, no matter how much political will exists.

The Current State of EV Charging Manufacturing

Let's talk about where manufacturing actually stands today. And this matters because it's the gap between policy intent and physical reality.

Most EV charging stations installed in the United States right now have components from all over the world. The enclosures, the cables, and final assembly often happen in the U.S. That's genuine progress. Companies like Blink Charging, Tesla, and others have been investing in domestic manufacturing capacity specifically because of NEVI incentives and the overall shift toward bringing supply chains home.

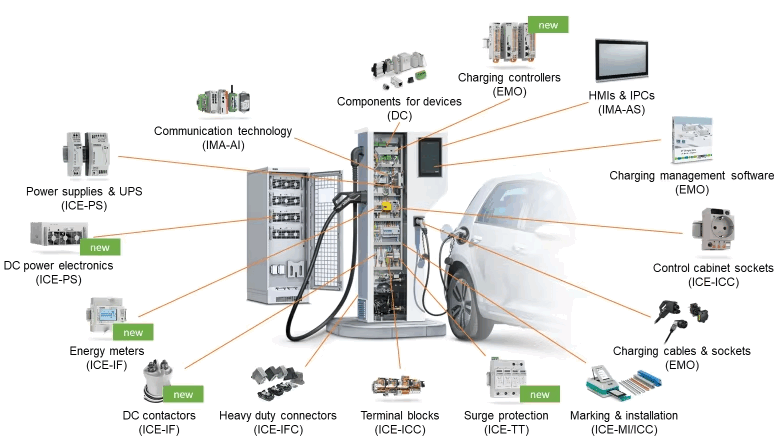

But the critical guts of a charger, the power electronics and advanced semiconductors, still come predominantly from Asia. Specifically from China, South Korea, and Japan. These are not simple components you can manufacture anywhere. They require specialized foundries, decades of expertise, and significant capital investment. TSMC doesn't have competing fabs in Arizona yet. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company remains the gold standard, and building a comparable facility in the U.S. takes years and billions of dollars.

According to industry analysis, the typical EV fast charger breaks down like this: enclosure and mechanical assembly (domestic possibility), charging cables and connectors (increasingly domestic), power conversion modules (currently imported), and control electronics with software (split between domestic and imported components). Achieve 100 percent domestic sourcing? That's currently impossible without either fundamentally redesigning the equipment or waiting for years of manufacturing buildout.

The supply chain reality is unforgiving. Chinese manufacturers have spent the last fifteen years building unmatched scale and cost advantage in EV charging components. They received enormous government subsidies to do it. When you combine state capital with manufacturing discipline and scale economics, you end up with Chinese companies supplying around 60-70 percent of the world's EV charging hardware. That's not incompetence on America's part. That's what happens when another country makes strategic investment in an industry over decades.

The previous policy actually made sense. The administration before Trump established a 55 percent domestic content requirement, scaled to increase over time. Companies could hit that target. It incentivized domestic investment without making the program impossible. Manufacturers could gradually shift supply chains, invest in U.S. facilities, and train American workers. That's industrial policy that works.

A 100 percent requirement immediately? That's industrial policy that fails by design.

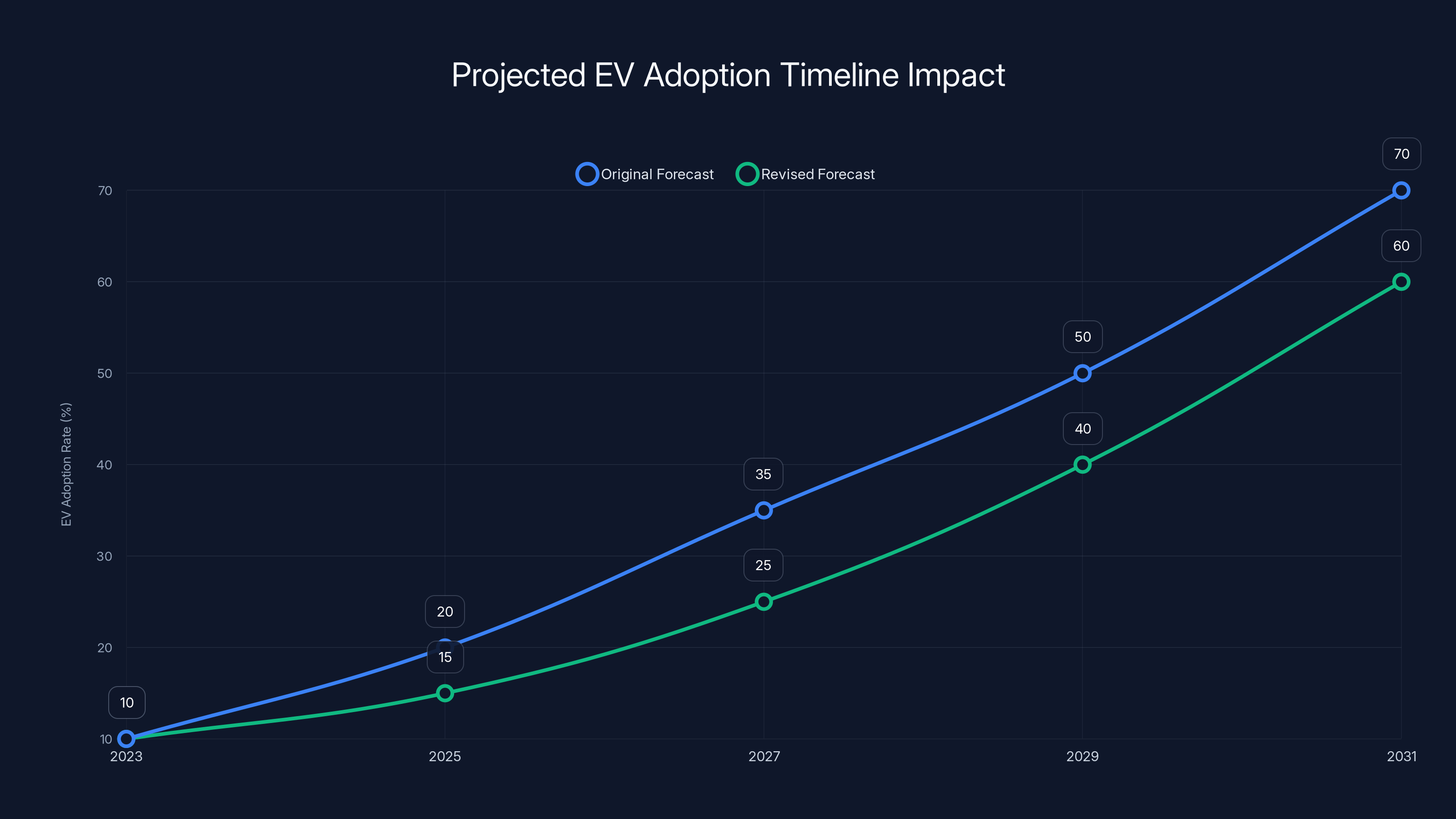

The delay in charging infrastructure expansion is projected to slow EV adoption, extending the timeline by 2-3 years. (Estimated data)

Why This Kills the NEVI Program (And Maybe Intentionally)

This is where you need to think like a policy analyst rather than accept statements at face value. The stated purpose of the Buy American requirement is to support U.S. manufacturing and job creation. The actual effect is to make the program unusable.

Consider what happens to a state like Georgia when this policy takes effect. Georgia was allocated $134 million in NEVI funding. That's real money. That's dozens of charging stations going up across the state, jobs in installation and infrastructure, and a genuine improvement to EV adoption potential. Except now those funds can't actually be spent, because no eligible equipment exists that meets the 100 percent requirement.

The funding doesn't disappear. It just sits there. The state has money but no way to spend it legally. Eventually, the money gets reclaimed or reallocated. In the meantime, EV charging buildout in Georgia stops. This wasn't a freak accident. This is what happens when you write requirements divorced from manufacturing reality.

Multiple industry groups stated this plainly in their response. The Zero Emissions Transportation Association called the policy out as something that "may discourage further investment in the production of U.S.-made EV chargers." Let that sink in. A policy supposedly designed to encourage American manufacturing will actually discourage it. Companies considering investments in U.S. charging equipment manufacturing will see the regulatory target move from 55 percent to 100 percent overnight and ask a rational question: why invest here when the goalposts just moved to an impossible position?

You can't invest in something you can't sell.

This is also a textbook example of how to kill a program without actually killing it politically. Trump's administration didn't need to call for defunding NEVI. They didn't need to get Congress to overturn the infrastructure law. They just had to make the program unworkable. A federal judge can't force you to spend money on a program if the requirements you set make spending illegal. It's a clever move, strategically speaking. It's also dishonest.

The evidence of intentionality matters here. If the administration actually wanted to build U.S. charging manufacturing capacity, they would have paired the new requirement with substantial industrial policy incentives. Tax credits for manufacturing facilities. Grants for semiconductor production. Infrastructure spending to support new factories. Workforce development programs. None of that came. It was just the requirement with no accompanying support mechanism.

That's not industrial policy. That's regulatory sabotage.

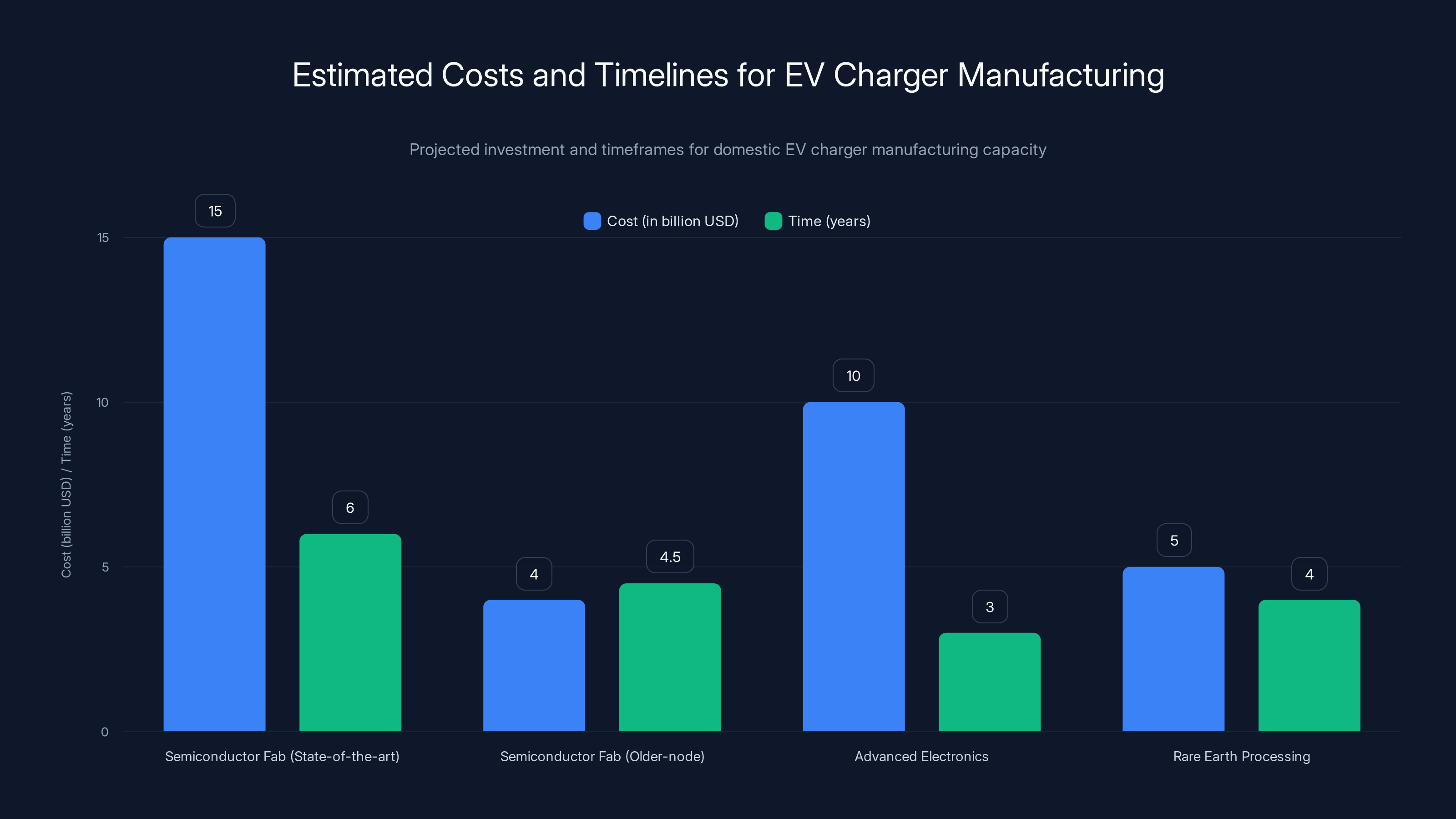

Building domestic semiconductor manufacturing capacity requires an estimated $10-20 billion and 5-7 years per plant. Estimated data.

The Broader Context: Trump's Anti-EV Strategy

This policy doesn't exist in isolation. You need to see it as part of a larger pattern of anti-EV action from the Trump administration.

Since taking office, Trump has taken steps to relax fuel economy standards, signaling that automakers won't face pressure to transition to electric vehicles. His administration has talked about rolling back or allowing states to waive vehicle emissions standards. When you layer these together, a coherent strategy emerges: slower EV adoption, with charging infrastructure as the lever.

See, charging infrastructure is the binding constraint on EV adoption. Not the vehicles themselves. Anyone shopping today can buy an EV from a dozen manufacturers. The challenge is charging. If you live in an apartment, finding a charger is hard. If you live in rural America, finding one is nearly impossible. Road trips become a planning exercise rather than a spontaneous activity.

Infrastructure solves all of that. Congress understood this when they funded NEVI. Build out the charging network, and suddenly buying an EV becomes a real choice for more Americans. Starve the charging network, and you preserve the status quo where most new car buyers still buy gas cars.

Trump's approach to this has been consistent: freeze the funding, then when forced to unfreeze it, add requirements that make it unusable. It's a workaround when direct confrontation isn't available. The judge wouldn't let him kill the program outright. Fine. He'll kill it functionally instead.

The policy also reveals something about how Trump administration officials think about American manufacturing capacity. They seem to believe the U.S. can instantly pivot to domestic production of complex electronics. That's not how manufacturing works. Building semiconductor fabs takes five to seven years and tens of billions of dollars. You can't mandate that into existence with a rule. You could incentivize it. You could fund it. You could invest in workforce development. But mandate? No.

What Actually Happens to NEVI Now

Let's be concrete about the timeline and what's already in motion.

States have already begun receiving their NEVI allocations. Illinois got funding. New Mexico got funding. Colorado, Washington, dozens of states. When the 100 percent requirement gets finalized, these states face a choice: proceed with existing bids that don't meet the new standard (and risk later non-compliance), or pause and rebid with the new requirement (delaying projects by months to years).

Most will choose to pause. State transportation departments are risk-averse. If there's any chance the federal government will claw back money spent on equipment that doesn't meet a stated requirement, they won't risk it. So projects freeze. Chargers that would have gone live in 2025 instead go live in 2026 or 2027, if at all.

For companies already manufacturing charging equipment in the U.S., this is particularly painful. They've invested capital and labor to hit the previous 55 percent requirement. Now they're being asked to completely reshape their supply chains with no timeline and no support. Some will exit the market. Others will invest in other countries where regulatory conditions are clearer and more realistic.

The broader EV charging market doesn't stop. It just moves. Private networks like Tesla's Supercharger network will keep expanding. They don't rely on NEVI funding, so the new requirements don't apply. Existing private charging networks will continue investing. But the public charging infrastructure that serves rural areas and low-income communities? That expansion slows dramatically.

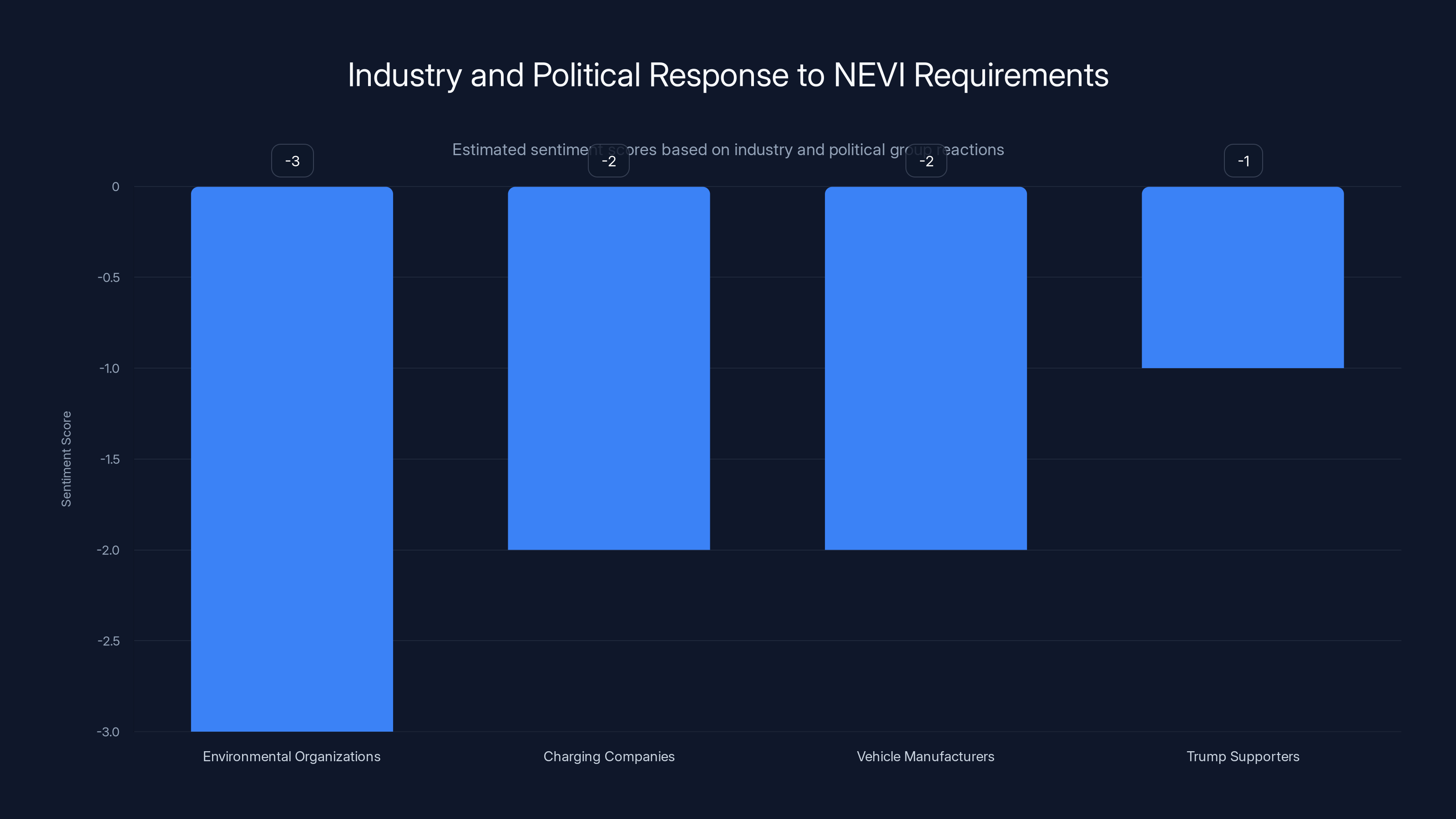

Estimated sentiment scores show a generally negative response across industry and political groups to the NEVI requirements, indicating broad disapproval. (Estimated data)

The International Competitive Dimension

Here's something that gets lost in the domestic politics of this issue: America isn't the only country building charging infrastructure. Europe is, China is, and they're doing it faster.

In China right now, there are roughly 2.4 million public EV charging points. That dwarfs the U.S. number. China's charging network is dense, reliable, and domestically manufactured. The Chinese government invested in that outcome intentionally, and it's working. Chinese EV adoption is consequently ahead of the U.S.

Europe has 600,000 charging points and is rapidly adding more. Countries like Norway have achieved 90 percent EV market share for new cars, partially because charging infrastructure reached saturation. Europeans can confidently buy an EV because they know they can charge it anywhere.

Meanwhile, the U.S. is now in a position where its federal charging program is functionally frozen, just as other nations are leapfrogging American infrastructure capacity. This isn't winning. This is losing to countries that actually invested in the future rather than sabotaging it.

There's also a manufacturing angle. While the U.S. tied itself in knots with a 100 percent requirement, Chinese manufacturers kept building. They're now establishing charging equipment factories in Southeast Asia and Eastern Europe to serve markets that don't have the same regulatory chaos. When American manufacturing does reach capacity (if it does), Chinese companies will already have market share everywhere else.

The policy that was supposed to protect American manufacturing interests is actually conceding global markets to competitors.

This is the paradox of the Trump approach to industrial policy. It focuses on restriction and punishment (of foreign manufacturing) rather than investment and capability building (in American manufacturing). Restrict Chinese components, and you don't get American components. You get delays and project cancellation. You need both the carrot and the stick. The Trump approach is all stick.

Industry Response and Political Reality

The response from industry groups has been remarkably unified, which is rare in this space. Environmental organizations, charging companies, and vehicle manufacturers all pushed back on the 100 percent requirement.

Plug In America, which represents owners and advocates, called the requirement "out of touch with U.S. manufacturing capacity." That's a polite way of saying it's impossible. The Sierra Club characterized it as a "bad-faith attempt to kill NEVI and block the buildout of essential infrastructure Congress funded for all Americans." Less polite. More accurate.

Even companies sympathetic to buy-American principles expressed concerns. They're not opposed to domestic sourcing. They're opposed to unrealistic requirements that destroy the program entirely.

The political dynamics here are interesting. Trump has a mandate from voters who support his stated goals: reducing government spending, supporting American manufacturing, and withdrawing from what they see as government overreach. The problem is, those voters might not understand that the policy doesn't actually achieve those goals. It doesn't support manufacturing. It kills the market for manufactured goods.

If Trump administration officials had any interest in genuine industrial policy, they would have worked with Congress to create a long-term manufacturing buildout plan paired with realistic timelines and substantial investment. Instead, they issued a regulatory requirement divorced from capability. That's not leadership. That's theater.

The question now is whether this survives legal challenge. The previous freeze was challenged in court and failed. This requirement might face similar challenges. Is a requirement that's impossible to meet under the Americans with Disabilities Act equivalent to a takings violation? Is it an arbitrary and capricious exercise of regulatory authority? The lawsuits will fly, and it'll be years before courts sort this out.

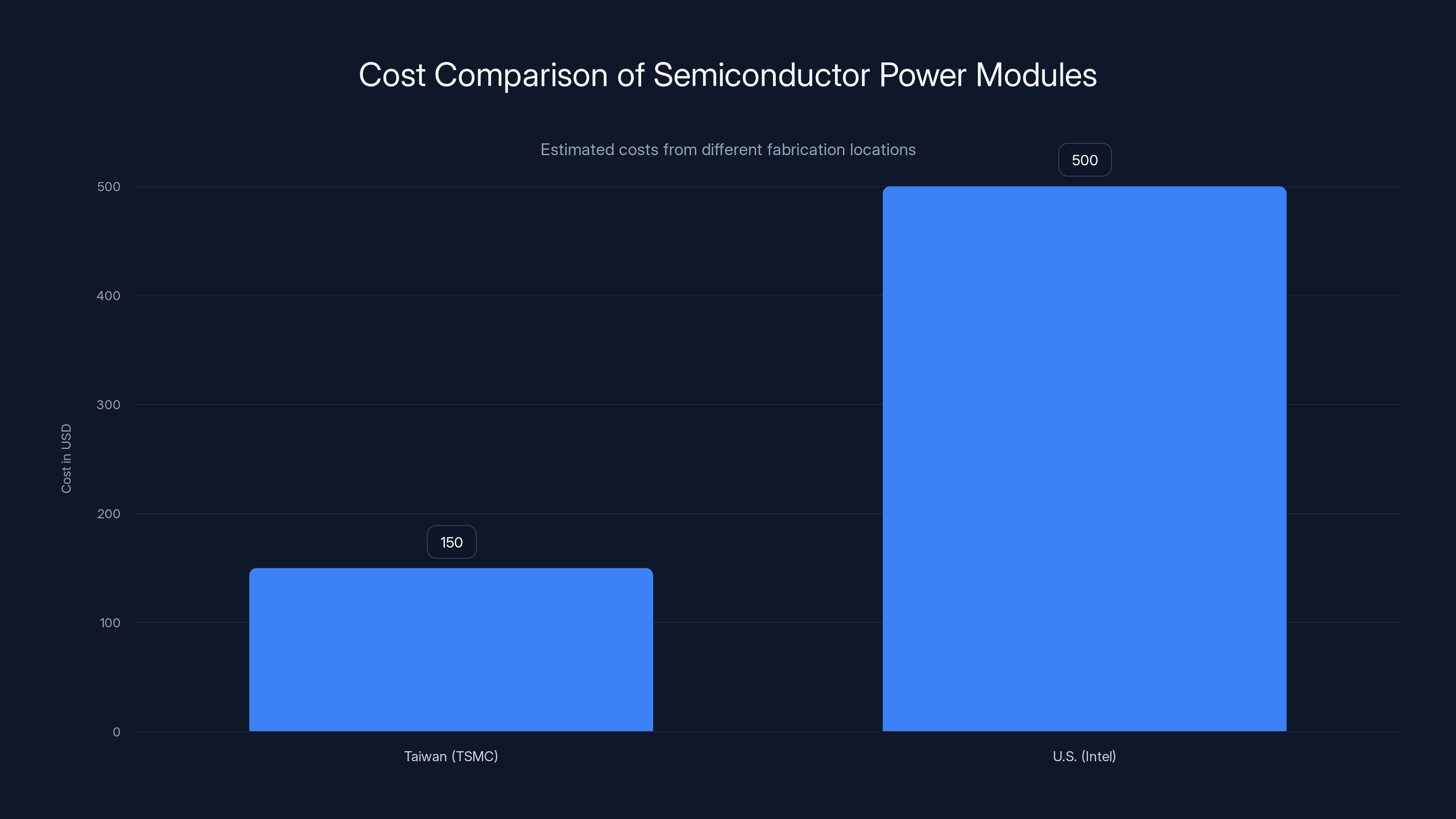

A power module manufactured in Taiwan costs

The Semiconductor Supply Chain Problem

To really understand why this policy is impractical, you need to understand what it means to manufacture an EV charger at the component level.

The critical component in any fast charger is the power conversion module. This is the electronics that takes wall power and converts it into the precise voltage and current needed to charge a vehicle battery safely. Building that module requires semiconductor components: microcontrollers, power MOSFETs, voltage regulators, and complex integrated circuits.

Here's the thing about semiconductors: they're not like manufacturing a car body or even a cable. You don't just need engineers and a factory. You need access to cutting-edge semiconductor fabrication technology. And that technology is concentrated in exactly three places: Taiwan (TSMC), South Korea (Samsung, SK Hynix), and the U.S. (Intel, and increasingly, others).

The U.S. is working to build domestic semiconductor capacity. The CHIPS Act provides incentives for building fabrication plants in America. But these are measured in years, not months. Intel's fabs take 4-6 years to build. TSMC's Arizona fab, announced in 2020, is still ramping production in 2025. This isn't laziness or lack of ambition. It's the nature of semiconductor manufacturing. You can't rush it.

So when the Trump administration says EV chargers must have 100 percent U.S. components, they're implicitly saying EV chargers must use semiconductors that either don't exist yet or cost three times as much because they're from a U.S. fab that's operating at capacity.

A power module manufactured using TSMC's latest process in Taiwan costs

Now, who pays that? The states with NEVI funding, of course. The budgets don't change, so they buy fewer chargers. The policy meant to create jobs actually results in fewer chargers being built.

Manufacturing Capacity and Timeline Reality

Let's look at what would actually need to happen to achieve 100 percent domestic manufacturing of EV chargers within a reasonable timeframe.

First, you'd need semiconductor manufacturing capacity. Building a state-of-the-art fab costs

Second, you'd need advanced electronics manufacturing capacity. This is less of a bottleneck than semiconductors, but still significant. You need facilities that can assemble complex circuit boards, test electronics, and integrate components. The U.S. has some of this, but not at the scale needed to supply the entire EV charger industry.

Third, you'd need rare earth element processing and specialty materials. Some components in chargers require materials like neodymium magnets or specialized ceramics. The U.S. currently has very limited capacity in these areas and would need to build it out.

All of this together would require a genuine industrial policy commitment: maybe $50-100 billion in federal investment, targeted to specific regions, paired with workforce development programs, tax incentives, and sustained demand guarantees. That's what a realistic Buy American policy would look like.

The Trump administration's policy? A requirement with no investment, no timeline, and no support mechanism. That's not a path to domestic manufacturing. That's a path to no manufacturing.

If you wanted to be charitable, you'd say the administration didn't understand the practical implications. If you wanted to be realistic, you'd say that blocking the program was the actual goal, and the manufacturing narrative was just cover.

Estimated data shows that while Georgia was allocated $134 million for EV infrastructure, the Buy American requirement renders these funds unusable, halting progress on charging stations and job creation.

The State-Level Impact and Divergence

Here's where this gets politically messy: different states are going to respond differently to this requirement.

Red states that received NEVI funding but don't want charging infrastructure anyway will quietly let the funds sit. Some already don't want EV charging, so the new requirement gives them political cover. "We'd love to build chargers, but the federal requirement makes it impossible." That's useful messaging for governors who don't want to fund EV infrastructure.

Blue states that genuinely want charging infrastructure will fight the requirement politically and in court. They'll work with companies to explore workarounds, potentially by supporting the creation of more domestic manufacturing capacity themselves. Some states may even allocate their own funding to support charging build-out independent of NEVI, which paradoxically might accelerate private charging infrastructure development.

This divergence is already happening at the margins. Some states with environmental commitments are investigating state-level charging infrastructure programs less dependent on federal funding. That sounds good in theory, but it means the national charging network becomes fragmented. Your ability to reliably road-trip across America depends increasingly on which states you're driving through.

Capital-rich states like California and New York can absorb the cost and complexity. Rural states without that capacity? They get left behind. The NEVI program was specifically designed to prevent that outcome, to ensure charging equity across the country. This new requirement undermines that entire purpose.

The Consumer Impact and Long-Term EV Adoption

Let's think about what this actually means for someone shopping for an EV in 2025 or 2026.

First, charging infrastructure won't expand as planned. The studies you might have read about America building charging networks on par with gas stations? Those timelines just extended by several years. Rural charging expansion slows. Corridor charging development stalls. The gap between charger availability in urban and rural areas widens.

Second, charging becomes more expensive when it does happen. Without the economies of scale that NEVI was designed to create, costs stay high. A charging station that would have cost

Third, EV adoption slows because people become less confident about charging availability and reliability. This is psychology, but it's real. If charging feels uncertain, people don't buy EVs. If charging feels abundant and cheap, they do. Policy that makes charging scarcer and more expensive makes EV adoption slower.

There's also a signaling effect. When the federal government signals that EV infrastructure isn't really a priority (by effectively freezing the program), other investors adjust expectations downward. Venture capital doesn't fund charging startups. Utilities don't invest in charging networks. Private equity looks elsewhere. The market responds to policy signals, and this signal is "don't bet on charging."

Long-term, this probably adds 2-3 years to the timeline for achieving EV adoption rates that were already baked into existing forecasts. It's not a complete setback. It's more like hitting the brakes on a speeding car. You don't stop. You just go slower.

For consumers, that matters. It means used EVs stay more expensive for longer because supply remains constrained. It means the TCO (total cost of ownership) advantage of EVs relative to gas cars takes longer to materialize. It means some people who might have switched to EV do another three-year lease on a gas car instead.

Again, this might be intentional. The Trump administration has shown consistent skepticism toward EVs broadly. If slowing EV adoption was the goal, this policy is effective.

Achieving 100% domestic EV charger manufacturing requires significant investment and time, with semiconductor fabs alone costing $10-20 billion and taking 4-7 years. Estimated data.

Legal and Congressional Challenges Ahead

This requirement won't stand unchanged. It'll face legal challenges, congressional pressure, and possibly regulatory revision.

On the legal side, the requirement could be challenged as arbitrary and capricious under the Administrative Procedure Act. A requirement that's literally impossible to meet might not survive judicial review. Courts have previously struck down regulations that lack a rational basis or impose requirements divorced from practical reality. This could easily fall into that category.

There's also the question of whether this violates the original statute. Congress passed the infrastructure law with specific intent: fund EV charging buildout. A regulation that makes buildout impossible arguably contradicts statutory intent. Congress could modify the statute to explicitly prevent such requirements, though that would require Republican agreement, which seems unlikely.

Congressionally, the path is more complicated. Democrats could introduce legislation to override the requirement, but it wouldn't pass a Republican-controlled Congress. Some moderate Republicans who voted for the infrastructure law might express concerns, but we haven't seen them act on it yet.

What's more likely is that this plays out in regulatory process over the next 18-24 months. The requirement probably gets finalized despite industry objections. Then lawsuits get filed. While those work through courts, states sit in limbo. Some states might ignore the requirement and proceed anyway, daring the federal government to claw back funds (unlikely). Others might apply for exemptions or delays.

By 2027 or so, courts probably rule the requirement unreasonable in some form, or a new administration modifies it. But those two years of delays compound. Projects that would have launched in 2025 launch in 2027. The charging network is already two years behind where it should be.

That's the real danger here. It's not just about this regulation. It's about the pattern. If federal agencies are going to issue impossible requirements and tie infrastructure in knots, private investors and states will start looking elsewhere. That destroys the entire bipartisan infrastructure framework.

Alternative Approaches That Could Work

If the goal actually were to build American charging manufacturing, here are approaches that would work:

Targeted tax credits for domestic manufacturing. Companies that build or expand charging manufacturing facilities in the U.S. get substantial tax credits. Not requirements. Incentives. If you want to build in the U.S., we'll make it profitable. That works.

Tiered requirements with realistic timelines. Require 55 percent domestic content in 2025, stepping to 70 percent in 2027, 85 percent in 2029, 100 percent in 2032. That gives manufacturers time to shift supply chains, build new facilities, and invest in U.S. capacity. It's achievable. It drives actual change.

Direct industrial policy investment. Fund semiconductor fabs. Fund electronics manufacturing facilities. Fund workforce development. If you want domestic manufacturing, invest in it rather than just mandate it. Mandates without investment are just regulation pretending to be policy.

Partnerships with manufacturers. Work with charging companies to identify actual bottlenecks and solve them through investment and partnership rather than regulation. What components are hardest to source domestically? What investments would unlock that capacity? Create a roadmap together.

Regional manufacturing hubs. Incentivize geographic clustering of charging manufacturing with workforce development, infrastructure investment, and anchor procurement. Make it worth for companies to locate there. Communities like Pittsburgh, Detroit, or regions in the Midwest could become charging manufacturing centers if actually supported.

All of these require investment, partnership, and thinking beyond a single regulatory line. They require what you'd call actual industrial policy. What happened instead was a requirement with no support, which isn't policy. It's sabotage.

Environmental Justice and Access Implications

There's a dimension to this that doesn't get enough attention: the impact on environmental justice.

The NEVI program was explicitly designed to ensure that EV infrastructure got built equitably across the country. That means rural communities, low-income neighborhoods, and underserved regions would get charging access, not just rich urban areas. When the program slows down, that equity goal suffers first.

Why? Because when budgets tighten and projects need to be prioritized, the first things to get cut are the projects in less densely populated areas. Rural charging corridors are expensive to build because you're serving fewer people per unit cost. But they're essential for rural EV adoption.

With NEVI funding reduced effectively to zero by this policy, rural charging expansion likely won't happen. Rural America will continue to have virtually no public charging infrastructure. Rural EV adoption will remain negligible because you can't buy an EV if you can't charge it reliably at home or nearby.

That's a climate justice issue. Rural communities already contribute disproportionately to emissions. They also tend to be poorer and have less political power. When infrastructure programs get starved, they suffer first. This isn't accidental. It's a predictable outcome of de-prioritizing the NEVI program.

There's also a labor justice angle. The NEVI program included workforce development components. Jobs building charging infrastructure, manufacturing charging equipment, and installing systems were supposed to support working-class communities. With the program stalled, those jobs don't materialize. Regions that were supposed to benefit from manufacturing buildout don't see the investment.

If you care about climate outcomes and environmental justice, this policy is a setback on both fronts.

Looking Forward: What Happens in 2026 and Beyond

So what's the most likely scenario over the next 18-24 months?

States freeze projects. NEVI funding accumulates on the books but doesn't get deployed. Companies either shift their manufacturing investments elsewhere or put them on pause. Private charging networks like Tesla Supercharger continue expanding because they don't depend on federal funding. But public charging networks slow dramatically.

By late 2026, legal challenges start reaching courts. States begin applying for waivers or exemptions. The Trump administration could potentially modify the requirement, though that would require them to acknowledge that the original policy was unworkable. Administrations rarely do that.

If Trump remains in office through 2028, the requirement probably stays in effect, with courts eventually striking it down. If a different administration takes over in 2029, one of the first things they do is modify the requirement to something realistic. That's assuming they prioritize EV infrastructure, which a Democratic administration probably would.

By 2030, we probably return to something closer to the previous 55-70 percent domestic content requirement. But by then, two to three years of NEVI deployment have been lost. The infrastructure gap relative to other countries has widened. American EV adoption is further behind Europe and China.

The irony is that if the goal was protecting American manufacturing interests, this policy failed dramatically. By stalling the program, it discouraged American companies from investing in manufacturing capacity. By creating regulatory chaos, it spooked capital away from the sector. By the time the requirement gets fixed, European and Asian manufacturers will have moved on to other markets.

The Bigger Picture: Federal Policy Reliability

Beyond the specific impact on EV charging, this situation raises a broader question about federal policy reliability.

Private companies and states need predictability. They invest billions based on the expectation that policy frameworks will remain stable or evolve gradually. When a Republican Congress and a Democratic executive branch reach bipartisan agreement on infrastructure policy, that's supposed to create certainty. Investors and states plan accordingly.

But if subsequent administrations can effectively nullify those agreements through creative regulation, the entire framework becomes unreliable. Why would states plan long-term based on federal commitments? Why would companies invest in manufacturing capacity if regulatory conditions can shift overnight?

This is how you destroy political capital and break the ability to govern on complex issues. If administrations can undermine congressional agreements through regulatory sleight of hand, Congress stops making bipartisan agreements. Investors stop making long-term bets. Everyone becomes more short-term focused.

The infrastructure law itself is at risk. If Trump's approach to the EV charging provision becomes a template, then other provisions of the law (road funding, broadband, rail, etc.) could face similar creative nullification. That weakens the entire bipartisan agreement.

From a governance perspective, this is destructive, even if you agree with Trump's skepticism about EV policy. There are legitimate debates about whether federal EV support makes sense. But those debates should happen through Congress, not through regulatory sabotage.

This sets a precedent that's dangerous. If Republican administrations can kill Democratic priorities through regulation, why wouldn't Democratic administrations do the same to Republican priorities? You end up with policy ping-ponging every four years, which makes long-term investment impossible.

The NEVI program is just the current case study. The principle matters more than the specific program.

FAQ

What exactly is the 100% domestic manufacturing requirement for EV chargers?

The Trump administration's Department of Transportation announced that EV charging equipment receiving federal funding through the NEVI program must now be entirely manufactured in the United States, with 100 percent of components sourcing domestically. Previously, the requirement was 55 percent domestic content. This new rule effectively creates an impossible standard because no manufacturer currently has the supply chain infrastructure to source every component domestically, particularly semiconductor-based power electronics that require specialized manufacturing.

Why can't manufacturers currently meet the 100% requirement?

EV chargers contain complex semiconductor components and power electronics that are manufactured globally, primarily in Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan. Building the equivalent manufacturing capacity in the United States would require 5-7 years and $10-20 billion in investment per new semiconductor fabrication plant. Additionally, rare earth elements and specialty materials required in chargers are processed outside the U.S. No company can reasonably shift to 100 percent domestic sourcing overnight without completely redesigning equipment or waiting for American manufacturing capacity that doesn't yet exist.

How does this policy impact NEVI funding deployment across states?

States that received NEVI allocations must now choose between proceeding with existing equipment that doesn't meet the new requirement (risking federal clawback) or pausing projects and rebidding with equipment that meets the requirement (delaying deployment by 6-18 months minimum). Most states will pause, effectively freezing the program. This means charging infrastructure buildout slows dramatically in states like Georgia, which had $134 million allocated, and others that were beginning deployment phases.

What was the previous policy, and why did it make more sense?

The previous requirement, established before Trump's second term, mandated 55 percent domestic content with planned increases over time. This was actually achievable because it focused on components already being sourced domestically (enclosures, cables, assembly) while acknowledging the reality that advanced semiconductors would take time to source entirely from the U.S. The previous policy drove actual investment in domestic manufacturing without making the program impossible to execute.

Is this requirement intentionally designed to kill the NEVI program?

The policy has the effect of killing the NEVI program regardless of stated intent. Trump's administration attempted to freeze NEVI funding entirely at the beginning of his term. When a federal court ordered the freeze reversed, this policy appears to be an alternative mechanism to achieve similar practical outcomes: making the program nonfunctional without explicitly calling for defunding. Industry groups across the spectrum characterize the policy as functionally impossible and destructive to the goal of building American charging infrastructure.

What's the timeline for legal challenges to this requirement?

Legal challenges are likely to be filed within months of the requirement being finalized. Arguments will likely focus on whether a requirement that's impossible to meet constitutes arbitrary and capricious regulation under the Administrative Procedure Act. However, litigation could take 2-3 years to resolve, during which the requirement remains in effect and deployment remains frozen. States may or may not comply while legal processes work through courts.

How does this compare to industrial policy in other countries?

Countries like China and Germany have invested heavily in charging manufacturing through direct subsidies, tax incentives, and workforce development rather than impossible mandates. The result is that these countries now have robust, cost-effective charging manufacturing sectors. The Trump administration's approach of regulation without investment is typically ineffective at building manufacturing capacity and often discourages the very investment it's supposed to encourage.

What would an effective Buy American policy for EV chargers actually look like?

An effective approach would combine realistic timelines (55 percent in 2025, stepping to 100 percent by 2032), direct investment in semiconductor fabrication and electronics manufacturing facilities, tax credits for domestic manufacturing expansion, and partnership with manufacturers to identify bottlenecks and solutions. It would take 5-10 years to achieve genuinely competitive domestic manufacturing capability, but such a policy would drive actual investment and capability building rather than program stalling.

Conclusion: Policy Meets Reality

The Trump administration's 100 percent domestic manufacturing requirement for EV chargers is, at its core, a policy that looks good on a press release but falls apart when you examine actual manufacturing realities. It's positioned as supporting American manufacturing and job creation, when the actual effect is to freeze infrastructure deployment and discourage the very manufacturing investment it claims to encourage.

This isn't about ideology. It's about physics and economics. You can't source semiconductor components domestically in volume within months or years when those components currently come from fabs that take five to seven years to build. You can't mandate a supply chain into existence. You can incentivize it, invest in it, and develop it over time. But mandate it immediately? That's a guarantee of failure.

The deeper issue is what this reveals about approach to policy-making. Real industrial policy requires investment, partnership, and realistic timelines. It requires understanding what you're trying to do and actually doing it. This policy skips those steps and just issues a requirement, expecting the market to instantly reorganize to meet it.

For states, companies, and consumers, the immediate impact is clear: EV charging infrastructure expansion slows. Rural areas get left further behind. Private charging networks continue expanding, creating more inequality in access. EV adoption faces a headwind just as other nations accelerate their own infrastructure buildout.

For the broader principle of federal governance, the concern is deeper. If administrations can effectively nullify bipartisan congressional agreements through creative regulation, the entire framework for long-term policy-making breaks down. That affects everything from infrastructure to research to technology development.

The NEVI program will likely survive this challenge, either through court intervention or through a future administration reverting to a more realistic requirement. But the damage extends beyond this single program. It's damage to the reliability of federal policy, to the confidence of investors and states in long-term planning, and to the momentum toward infrastructure development that had actually started to move.

Sometimes the most consequential policy failures aren't the ones that hit the news hard. They're the ones that quietly stall progress on essential infrastructure while sounding patriotic. This is one of those cases.

The bottom line: A policy designed to protect American manufacturing is instead destroying the market for American manufacturing, discouraging investment, and delaying infrastructure that's critical to keeping EV adoption moving forward. That's not just bad policy. That's policy working exactly opposite to its stated purpose, which suggests the stated purpose was never really the goal.

Key Takeaways

- Trump administration's 100% domestic manufacturing requirement for NEVI-funded EV chargers is functionally impossible to meet because semiconductor components are manufactured globally in Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan

- The policy effectively freezes $5+ billion in EV charging infrastructure deployment when states can't deploy equipment legally and legally compliant equipment doesn't exist

- Previous 55% domestic content requirement was achievable and drove actual investment; 100% requirement with no accompanying manufacturing support is regulatory sabotage masquerading as industrial policy

- No semiconductor fab in the U.S. has capacity to supply charger components at scale without 5-7 year buildout requiring $10-20 billion investment per facility

- Policy disproportionately impacts rural communities and low-income areas that depend on federal NEVI funding, while private charging networks (unaffected by the requirement) continue expanding

Related Articles

- Data Center Backlash Meets Factory Support: The Supply Chain Paradox [2025]

- Intel Core Ultra Series 3 Launch Delayed by Supply Crunch [2025]

- Live Nation's Monopoly Trial: Inside the DOJ's Internal Battle [2025]

- Why America's $12B Mineral Stockpile Proves the Future Is Electric [2025]

- Nvidia's AI Chip Strategy in China: How Policy Shifted [2025]

- Shadowfax IPO Listing: Why Client Concentration Spooked Investors [2025]

![Trump's 'Buy American' EV Charging Rule: A De Facto NEVI Moratorium [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/trump-s-buy-american-ev-charging-rule-a-de-facto-nevi-morato/image-1-1770764798672.jpg)